Submitted:

11 April 2025

Posted:

16 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Our Contributions

- We analyze the effect of the alphabet size (used to encode the string) has on the compression ratio(Cr) on the selected lossless compression schemes i.e.: Huffman Coding (HC), Run-Length Encoding (RLE).

- We conduct comparative analyses between Shannon Entropy and Algorithmic Complexity with regards to the randomness character of a finite string (Section 5.2).

- In order to approximate the Algorithmic Complexity of bounded strings, we propose an approach to overcome the current limitation of the CTM/BDM (Section 5.2.2).

- We propose an alternative method to approximate Shannon Entropy (H) in the software package pybdm ([1]). This is an implementation of the Schürmann-Grassberger estimator (7). The added value of this approach is that, it is bias minimized compared to the maximum likelihood approximation method (Section 5.2.1).

3. Related Work

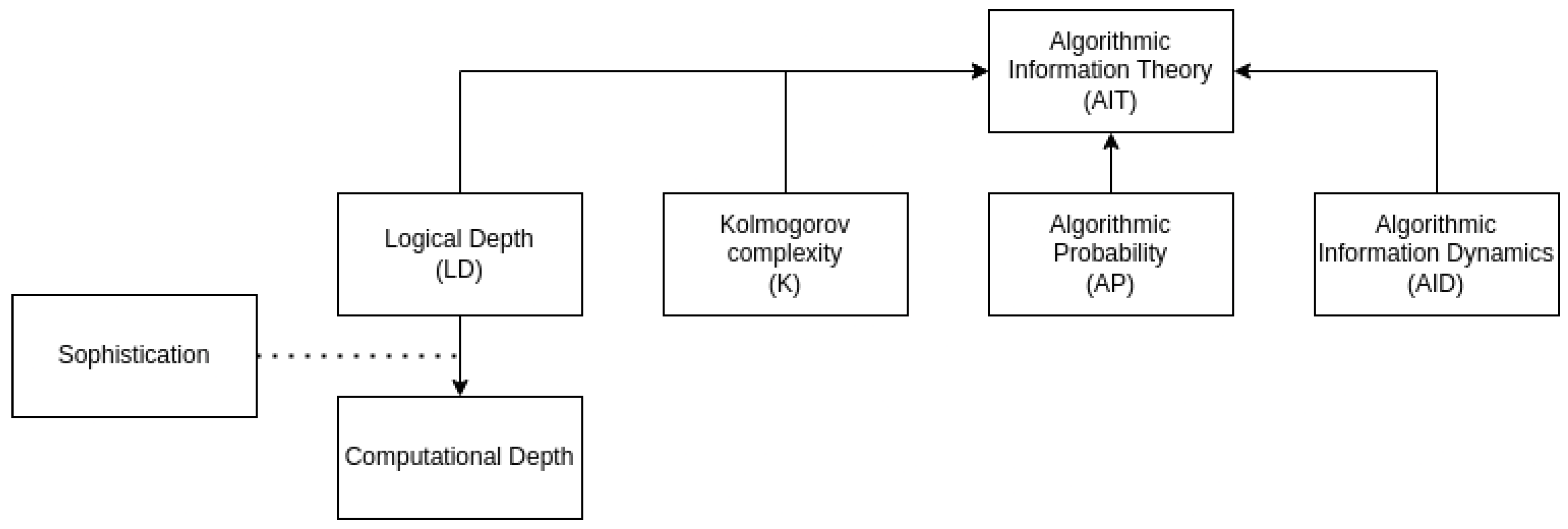

4. Theoretical Landscape

4.1. Dealing with Kolmogorov’s Complexity Uncomputability

4.2. Approaches to Approximating Algorithmic Complexity

- the frequency of occurrence of a string(through Algorithmic Probability (AP))

- to its Algorithmic Complexity (AC).

4.2.1. Run-Length Encoding

4.2.2. Huffman Coding

Reference work

4.2.3. Coding Theorem Method - CTM

4.2.4. Block Decomposition Method - BDM

Reference works

4.3. Bounds - Entropy

4.4. The Reference Machine Question

- What model of computation? e.g.: Turing machine, -calculus, combinatory logic, boolean circuits…

- How does the alphabet/encoding affect computation?

4.4.1. On the Power of Turing Machines

4.5. Impact – What’s the added value of AIT?

- Parameter-free method,

- Computationally efficient,

- Better encompasses the universal character.

- Currently BDM’s approximation has been constructed using a two symbols or binary() alphabet,

- Its universal character.

5. Experimentation

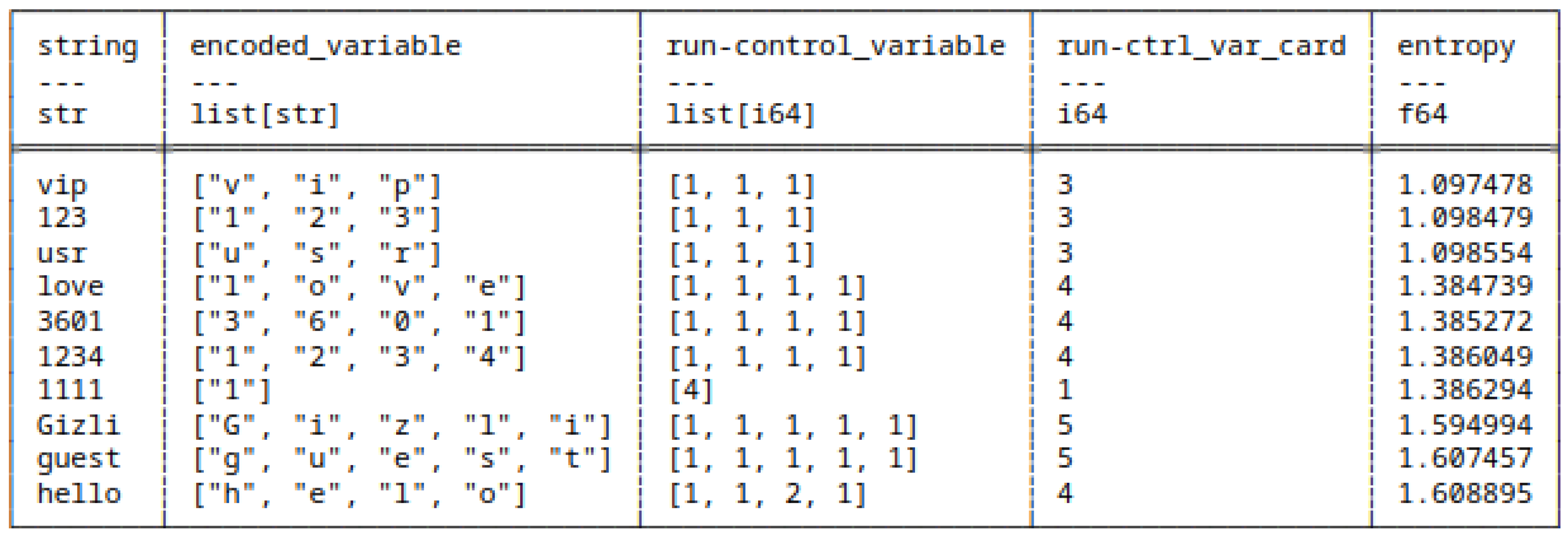

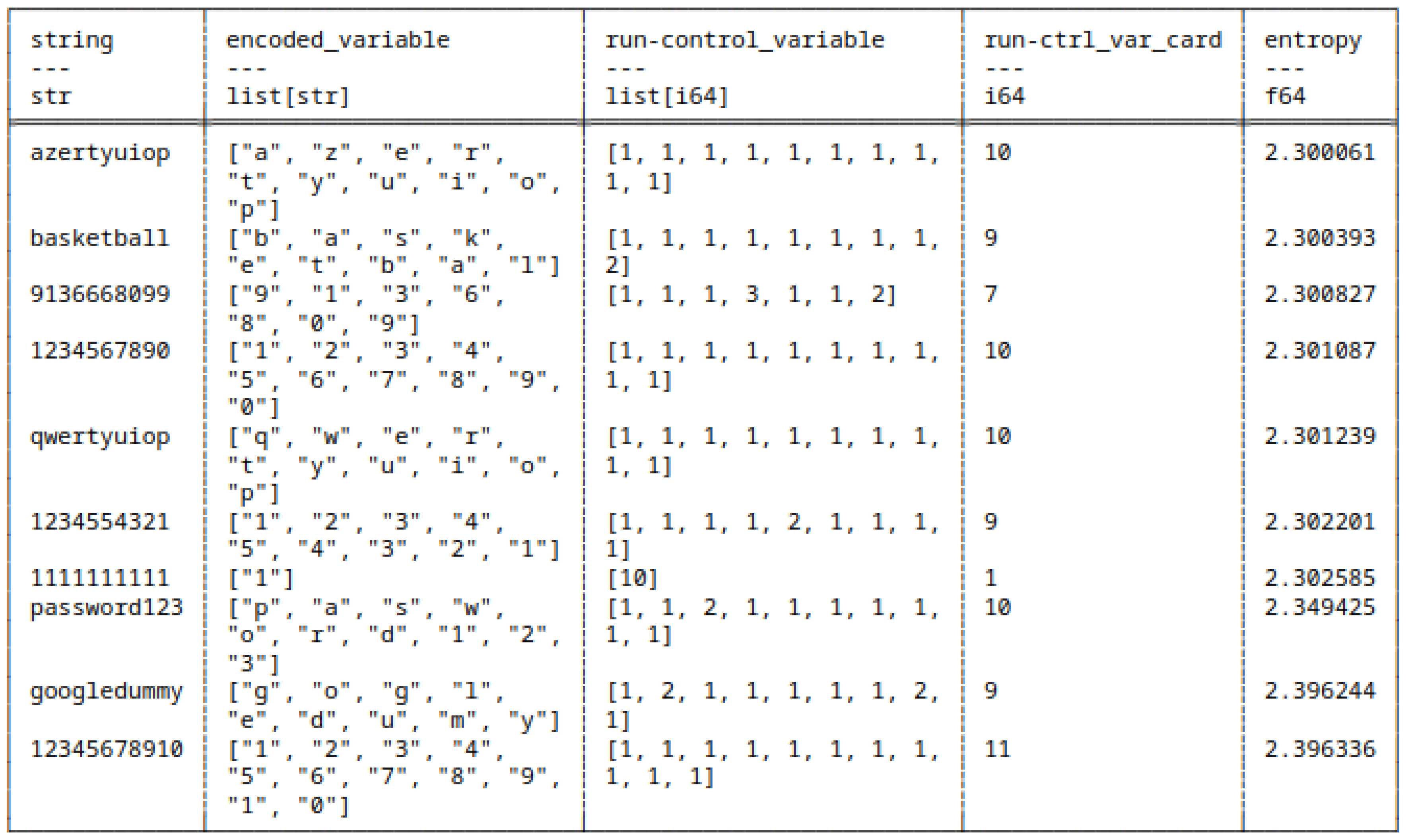

5.1. Data - Text Sequence

5.1.1. Preprocessing and Computing

5.2. Methods

- Run-Length Encoding (RLE) - ∈ entropy coding, lossless compression [Section 4.2.1]

- Huffman Coding (HC) - ∈ entropy coding, lossless compression, [Section 4.2.2]

- Coding Theorem Method (CTM) / Block Decomposition Method (BDM) - custom built around Algorithmic Probability [Section 4.2.3, Section 4.2.4]

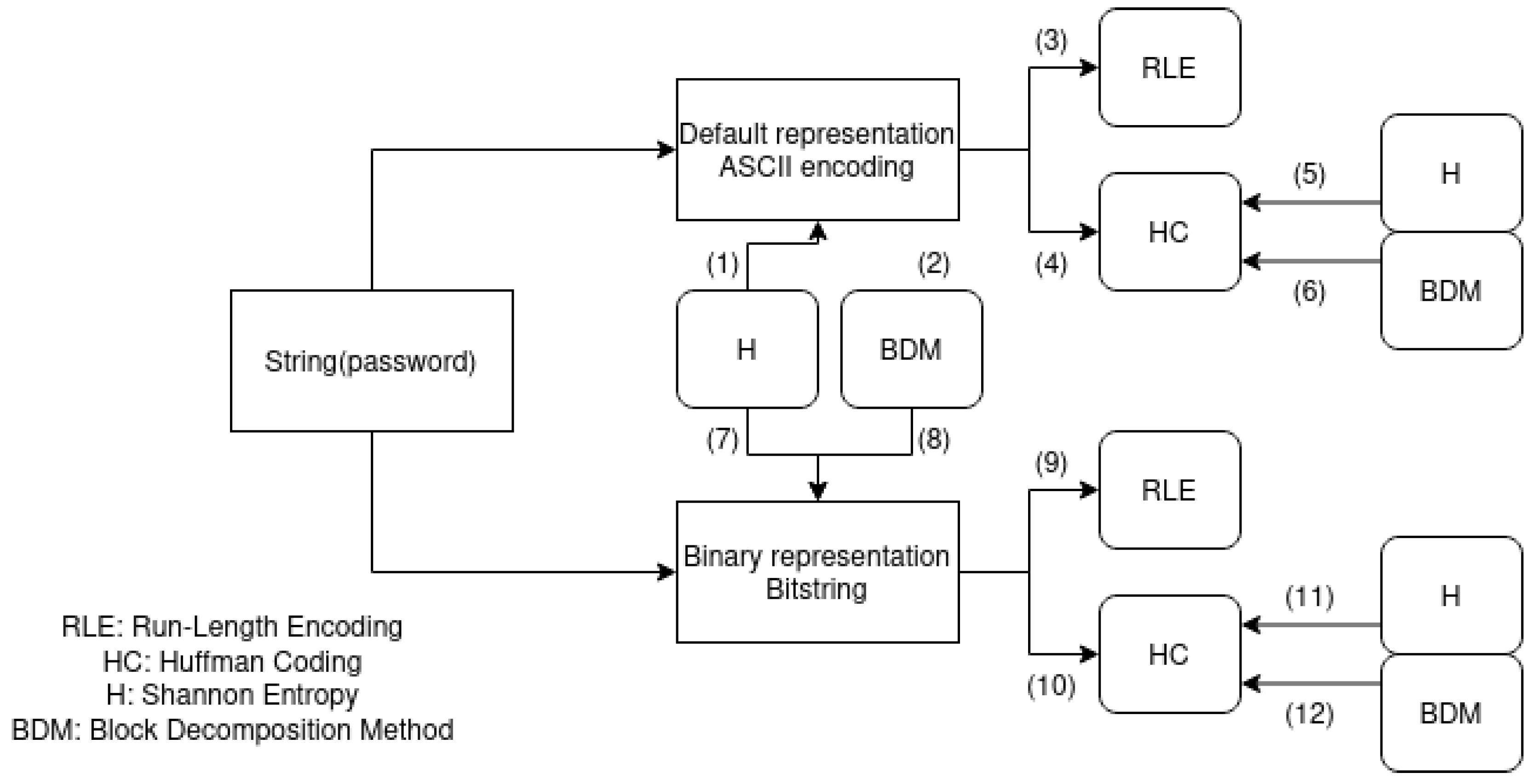

- Apply the RLE, HC, CTM/BDM algorithms on the strings; if possible, in their ”native”/default representation - usually using an alphanumeric character encoding.

- Apply the three algorithms on the passwords in their binary representation

- Outline and compare the results

5.2.1. On Computing Entropy

5.2.2. On computing BDM

ASCII code. The standard character code on all modern computers (although Unicode is becoming a competitor). ASCII stands for American Standard Code for Information Interchange. It is a (1+7)-bit code, with one parity but and seven data bits per symbol. As a result, 128 symbols can be coded. They include the uppercase and lowercase letters, the ten digits, some punctuation marks, and control characters.

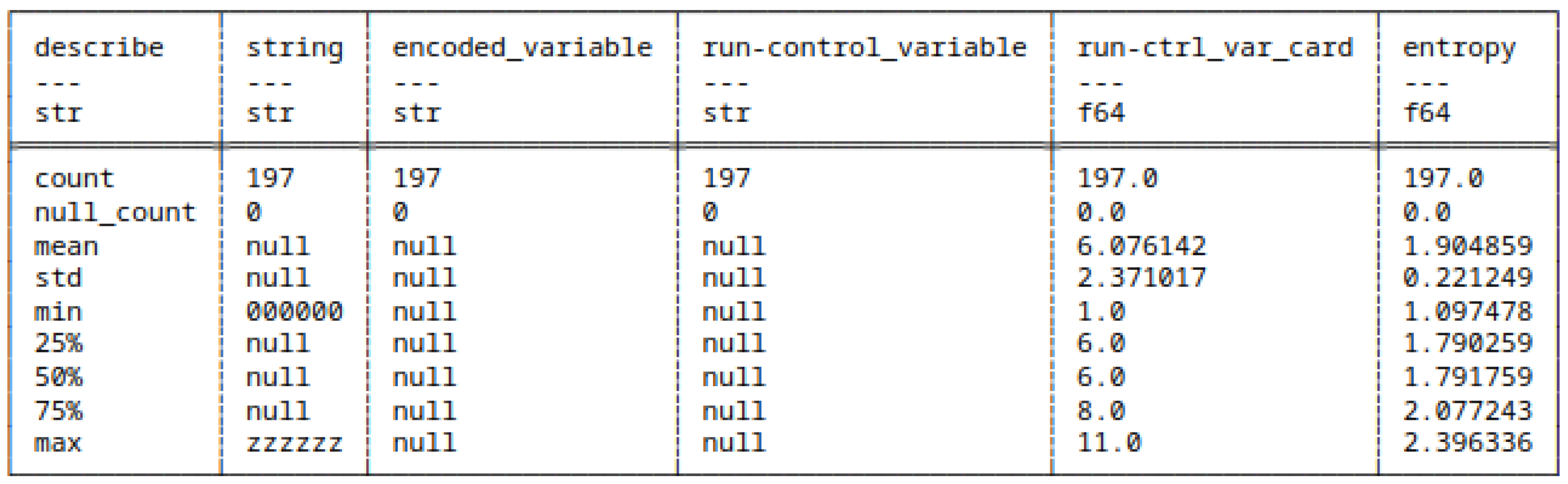

5.3. Strings Under Their Default Alphabet Representation

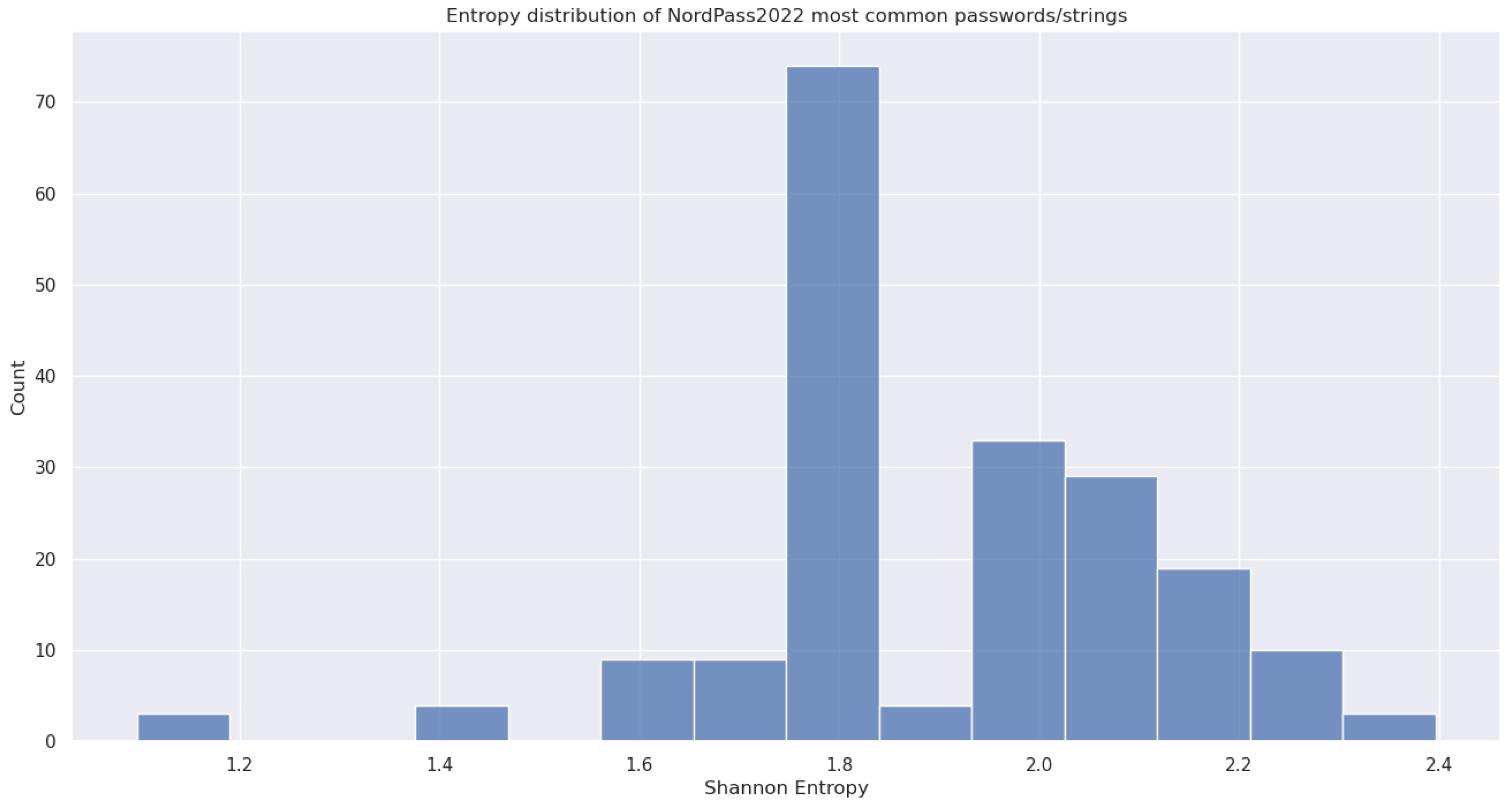

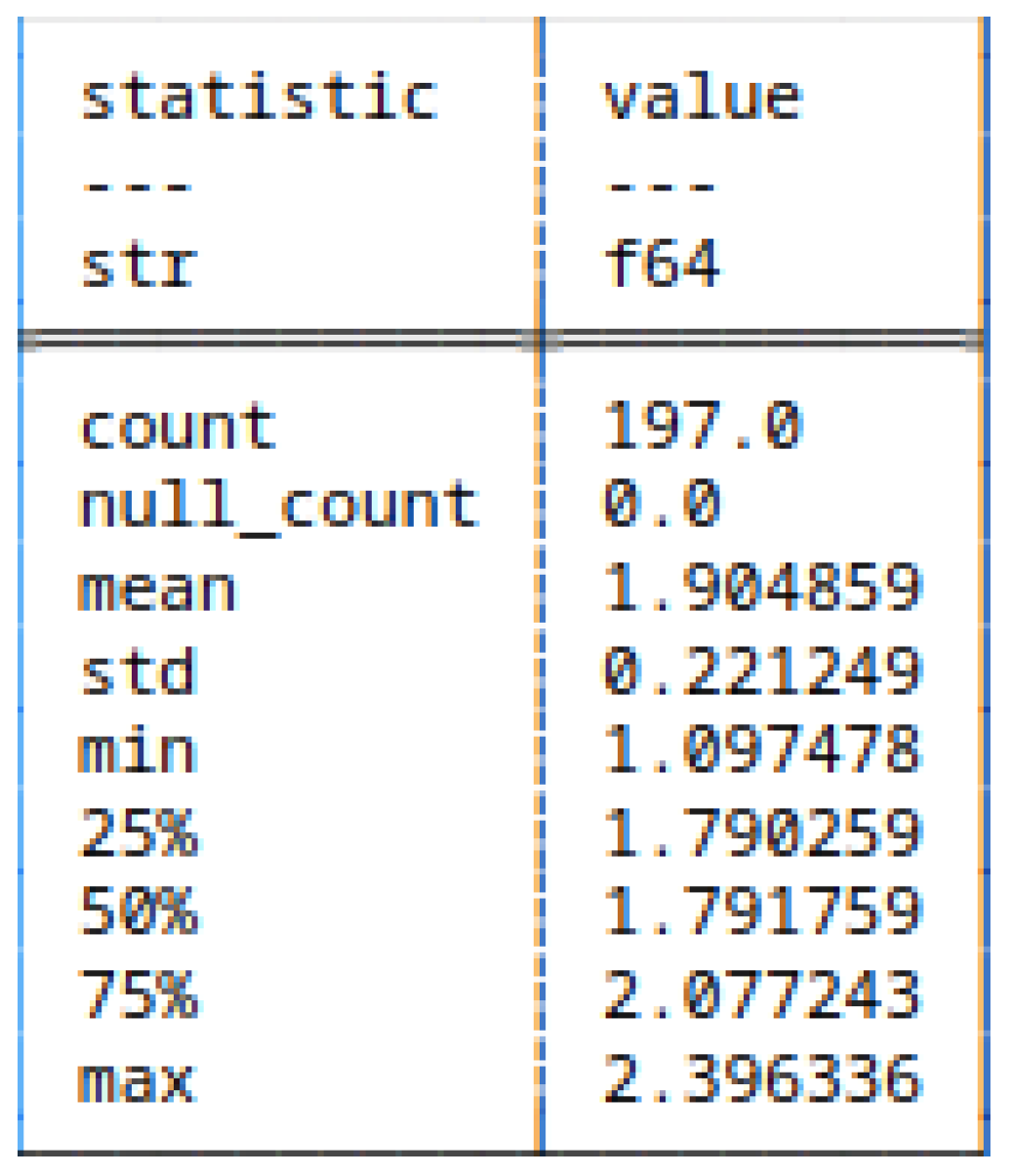

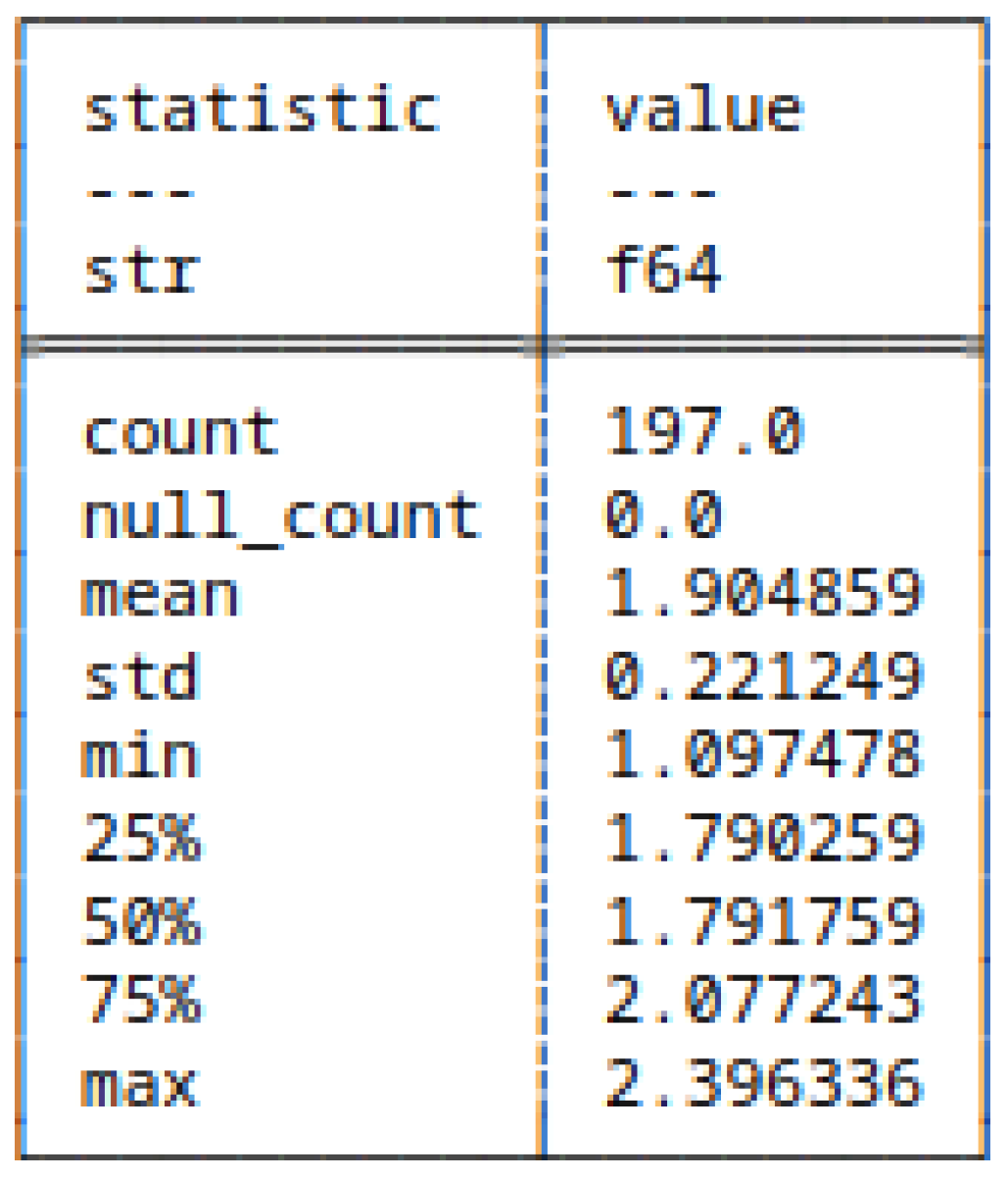

5.3.1. (1) - Shannon Entropy applied to strings

5.3.2. (3) - Run-Length Encoding Applied to Strings

Note

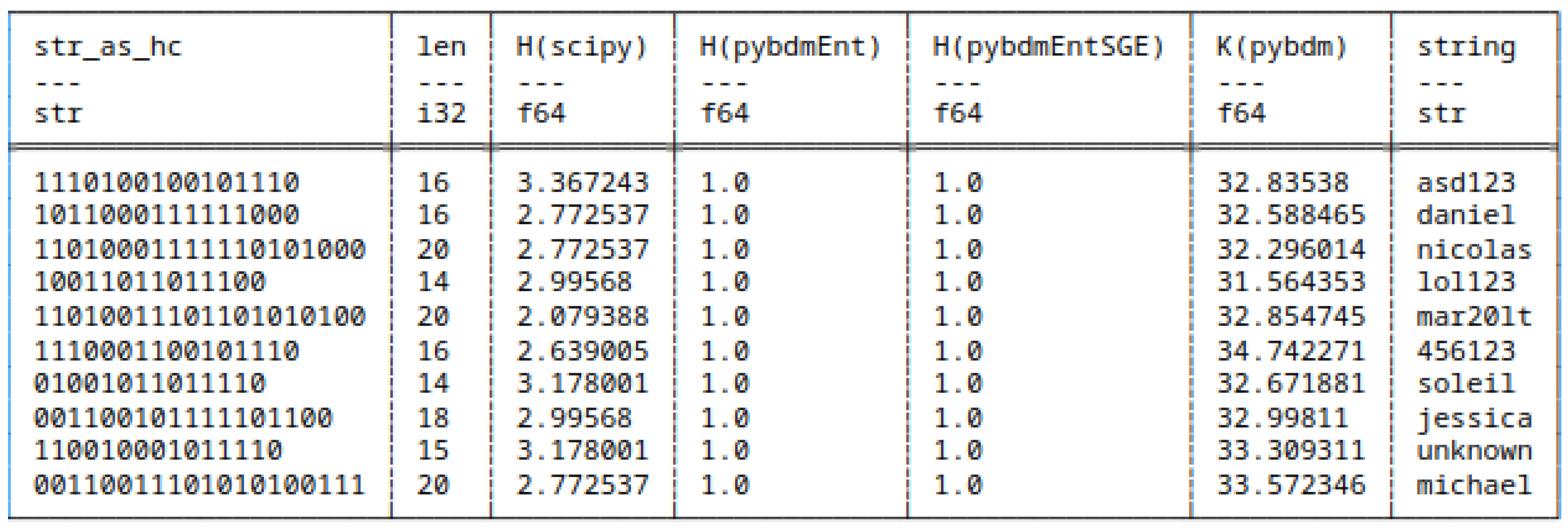

5.3.3. (4) - Huffman Coding Applied to Strings

Note

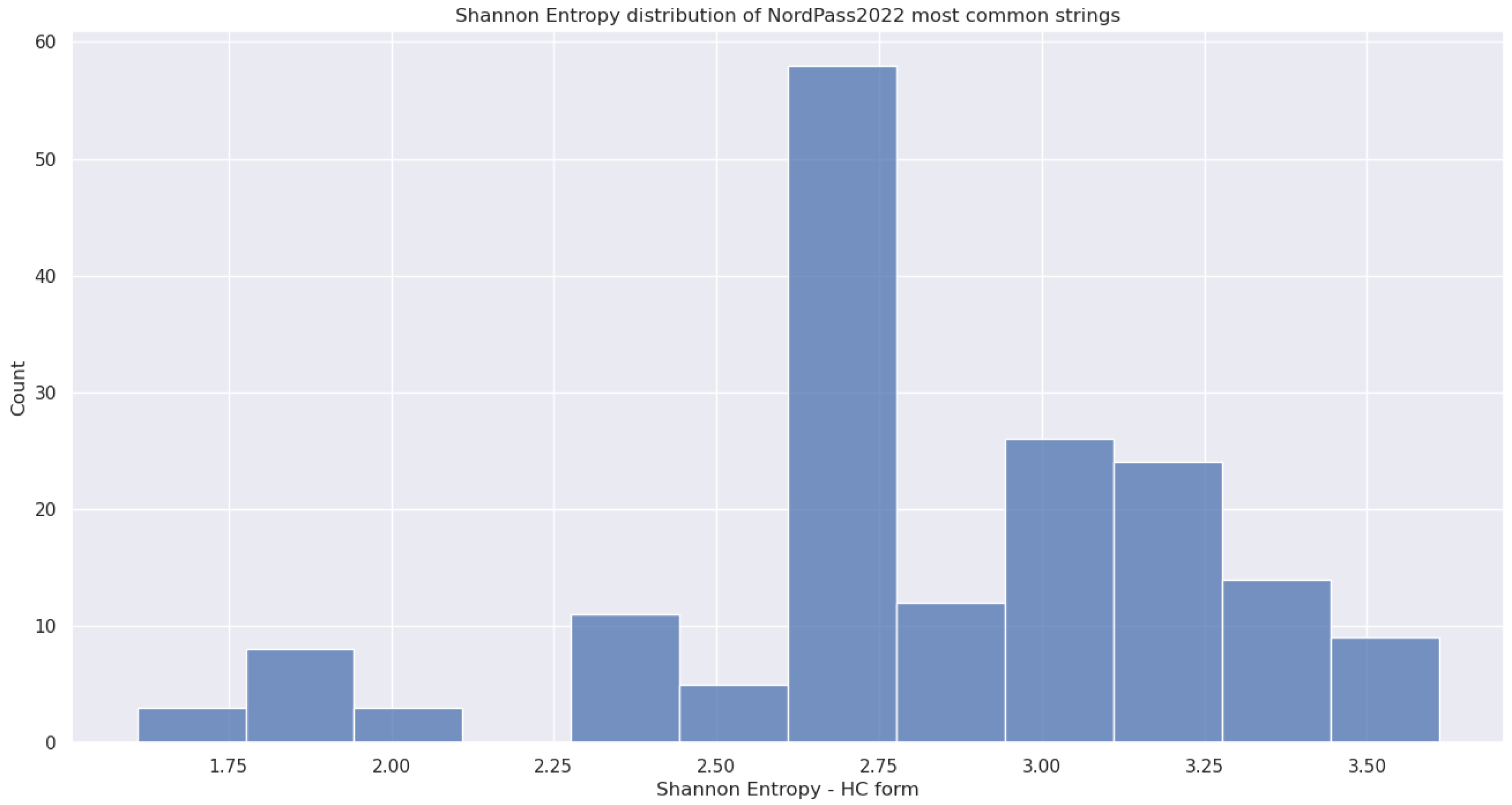

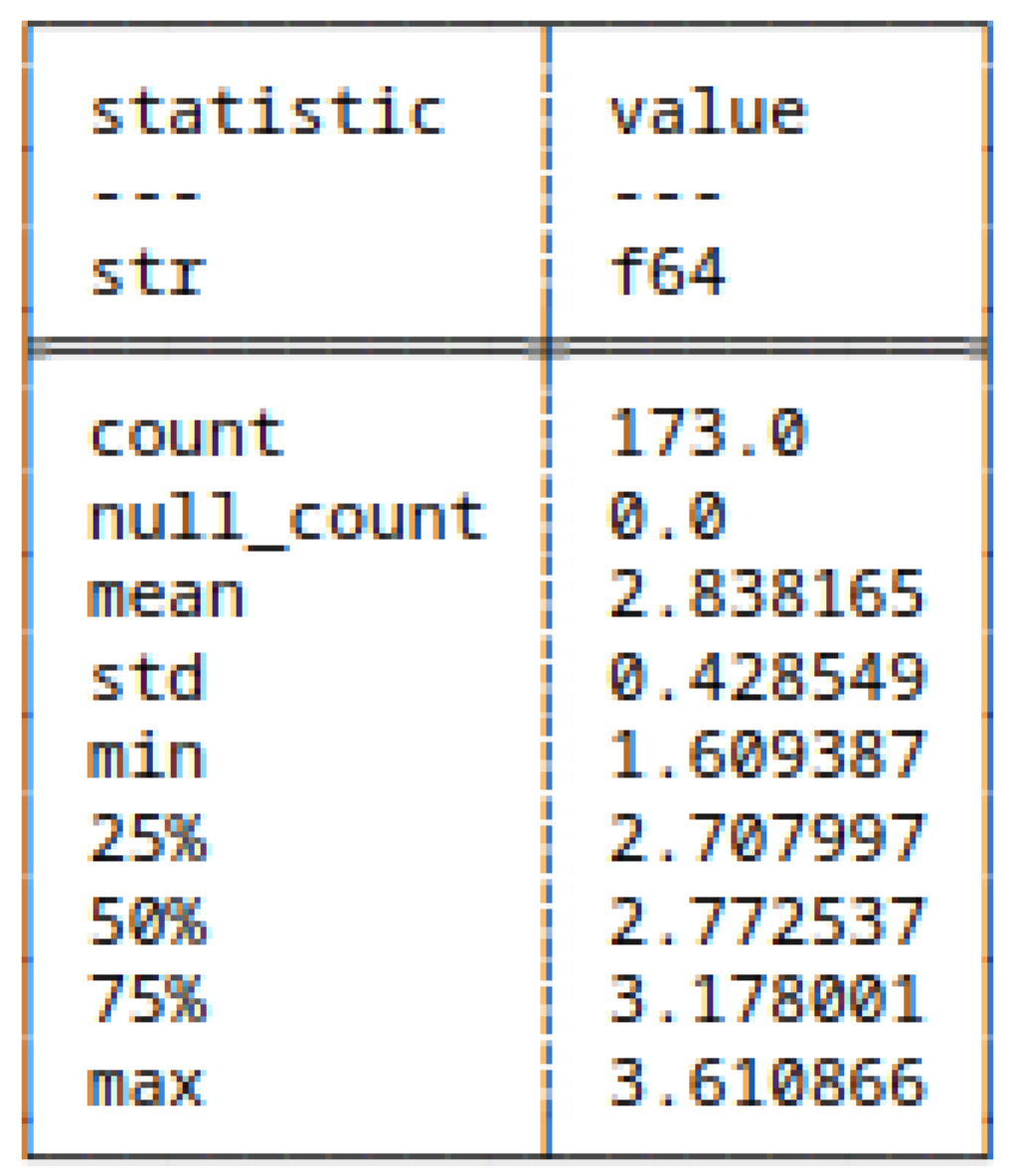

5.3.4. (5) - Shannon Entropy Applied to HC

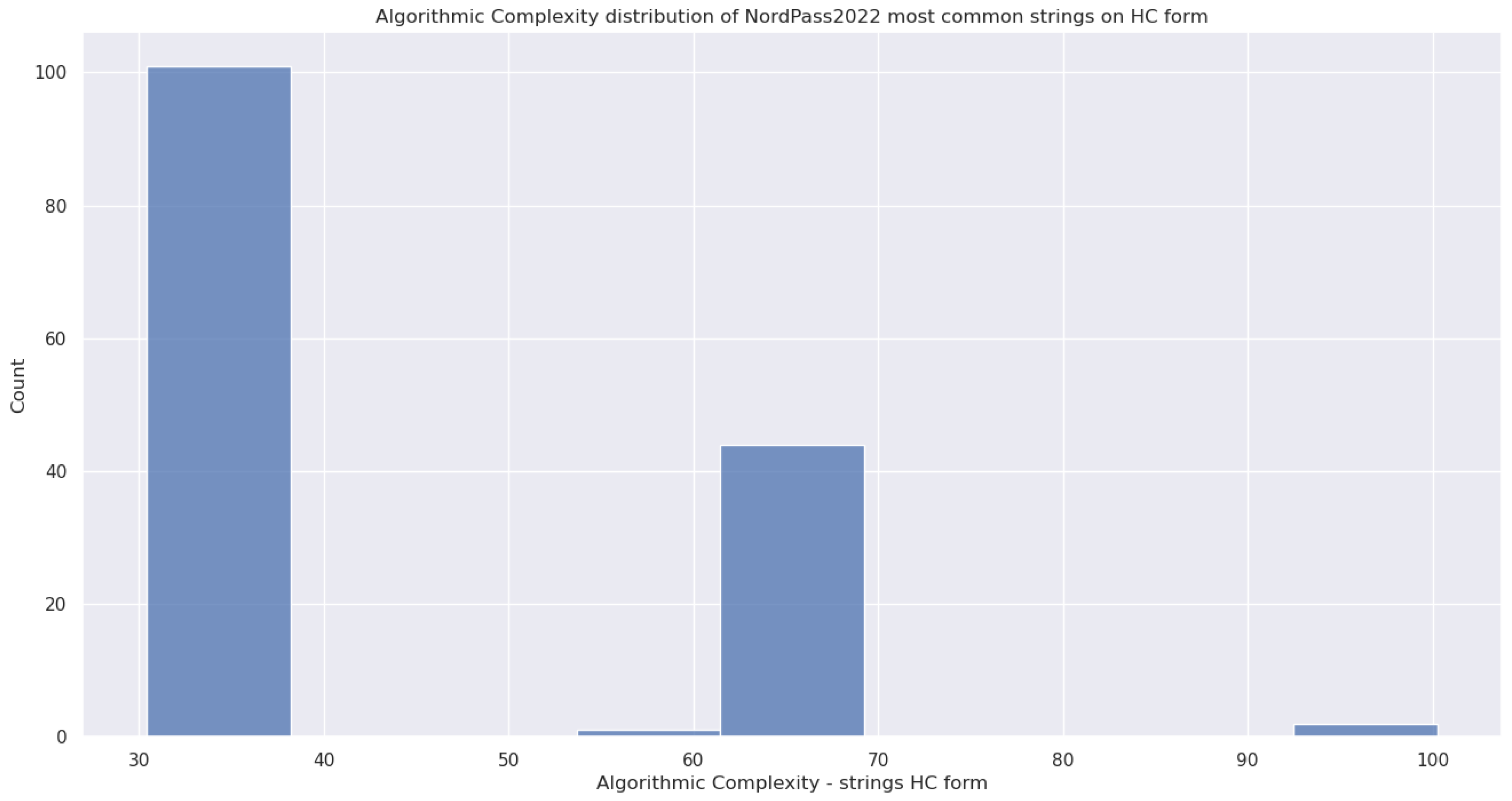

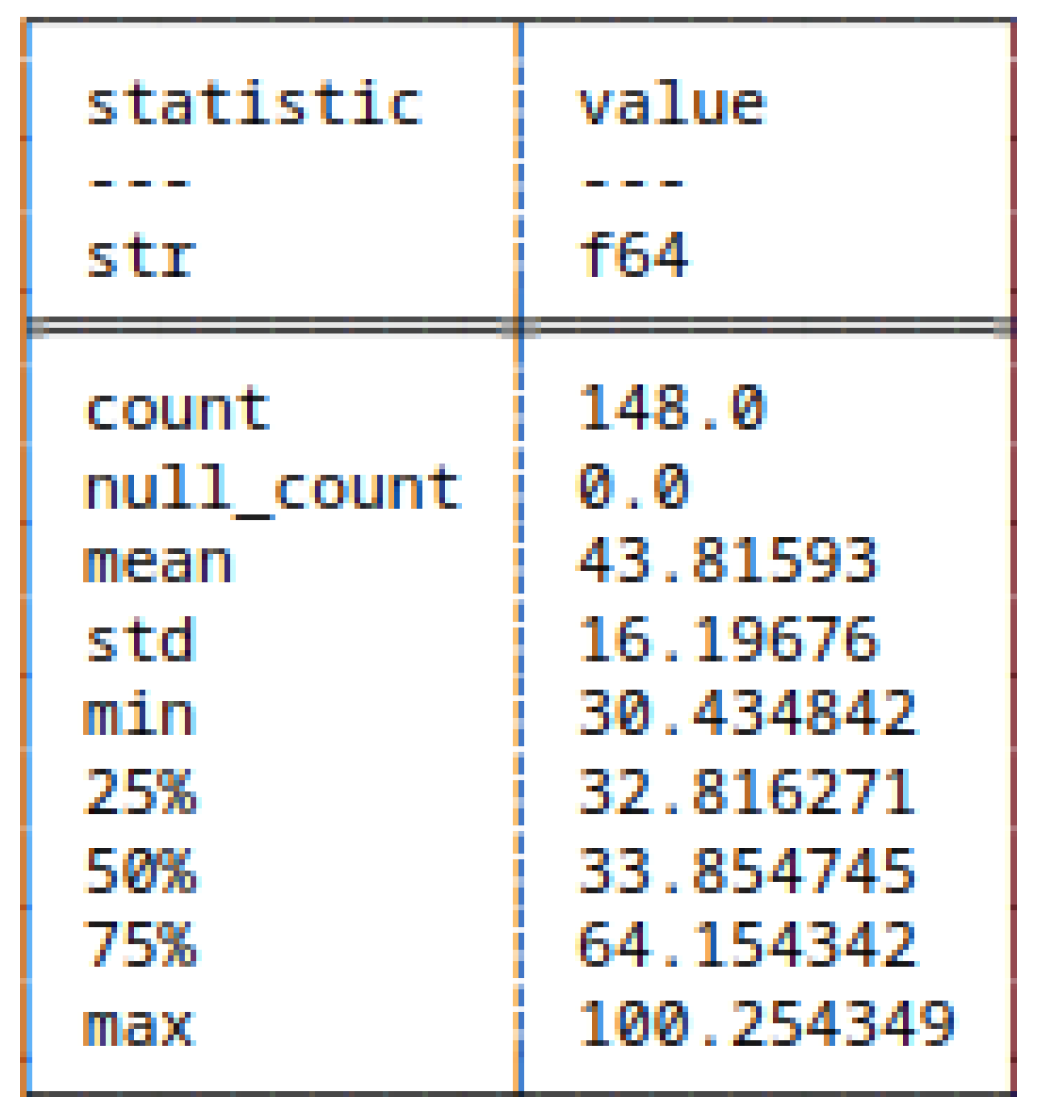

5.3.5. (6) - Block Decomposition Method Applied to HC

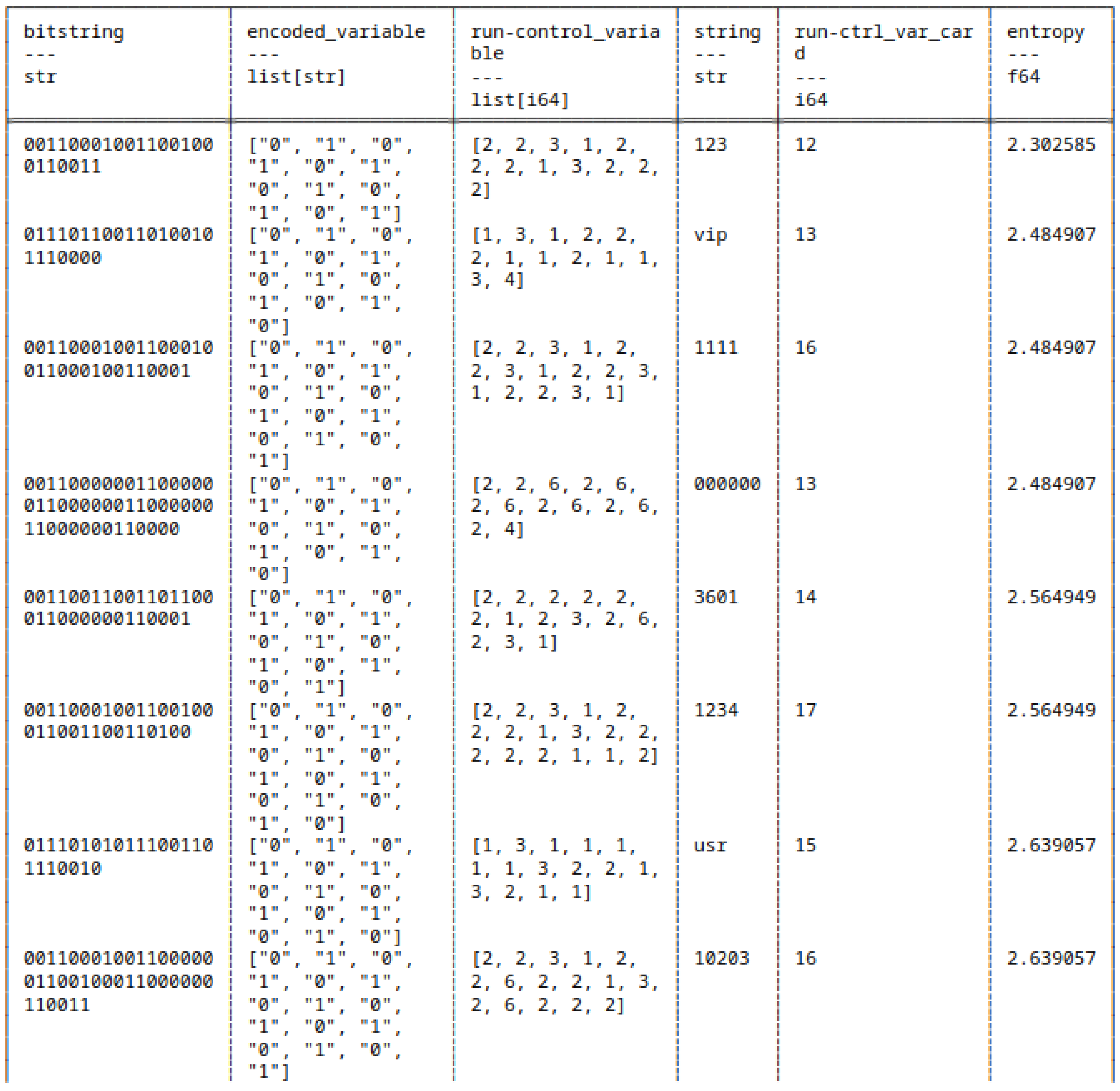

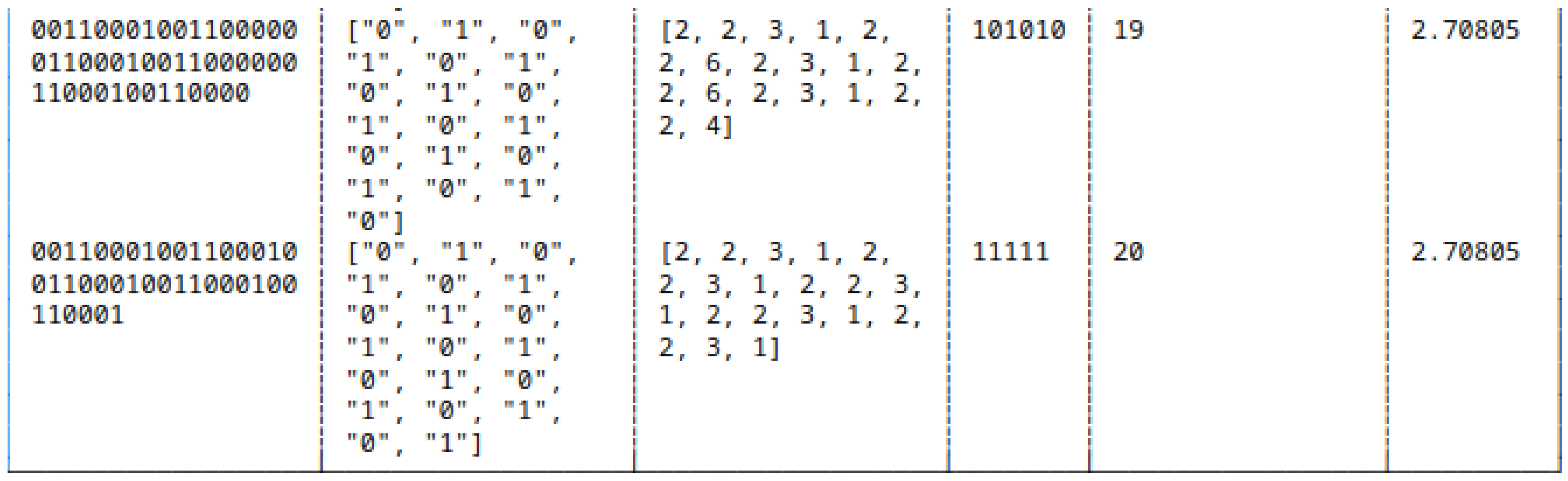

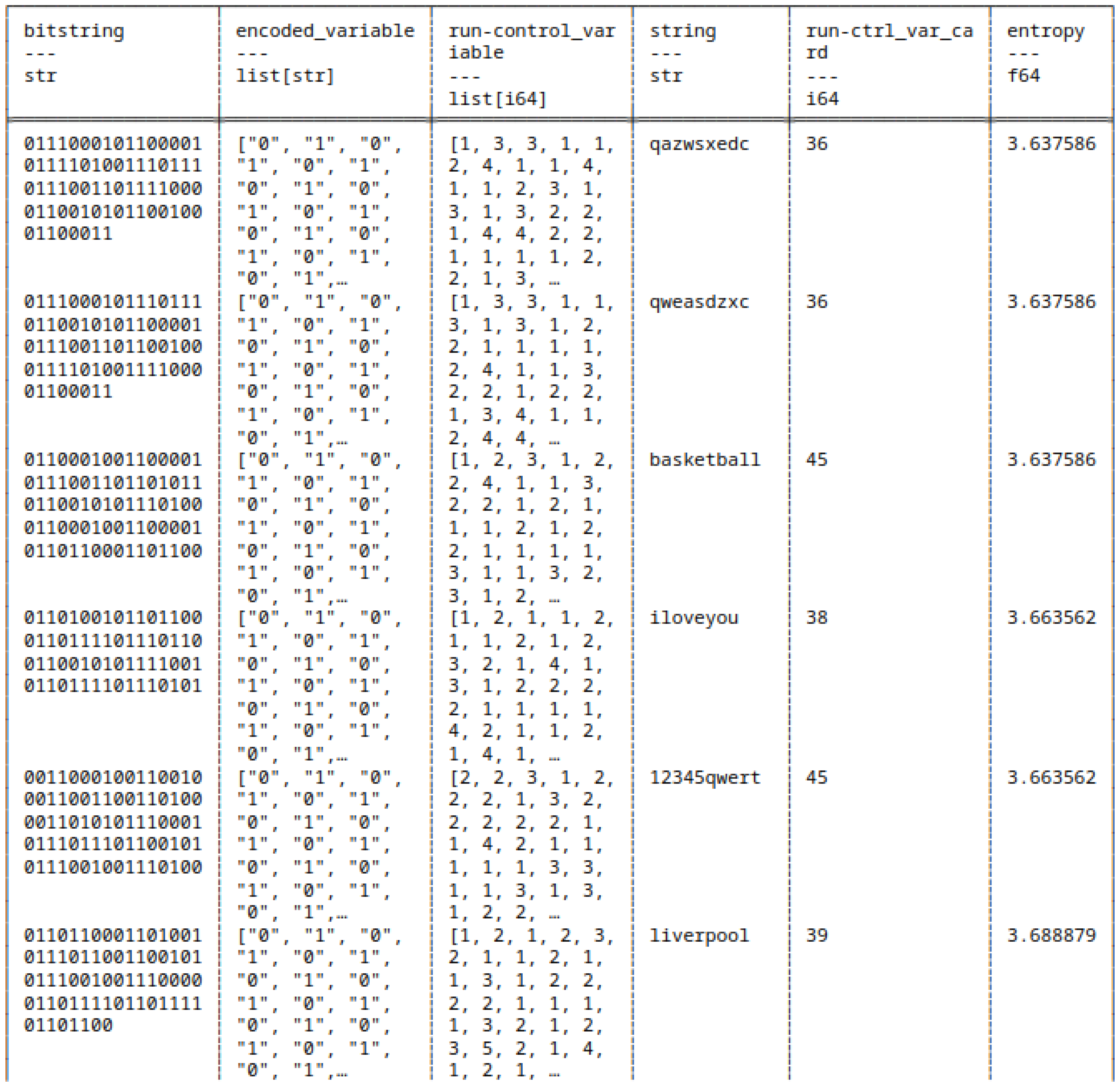

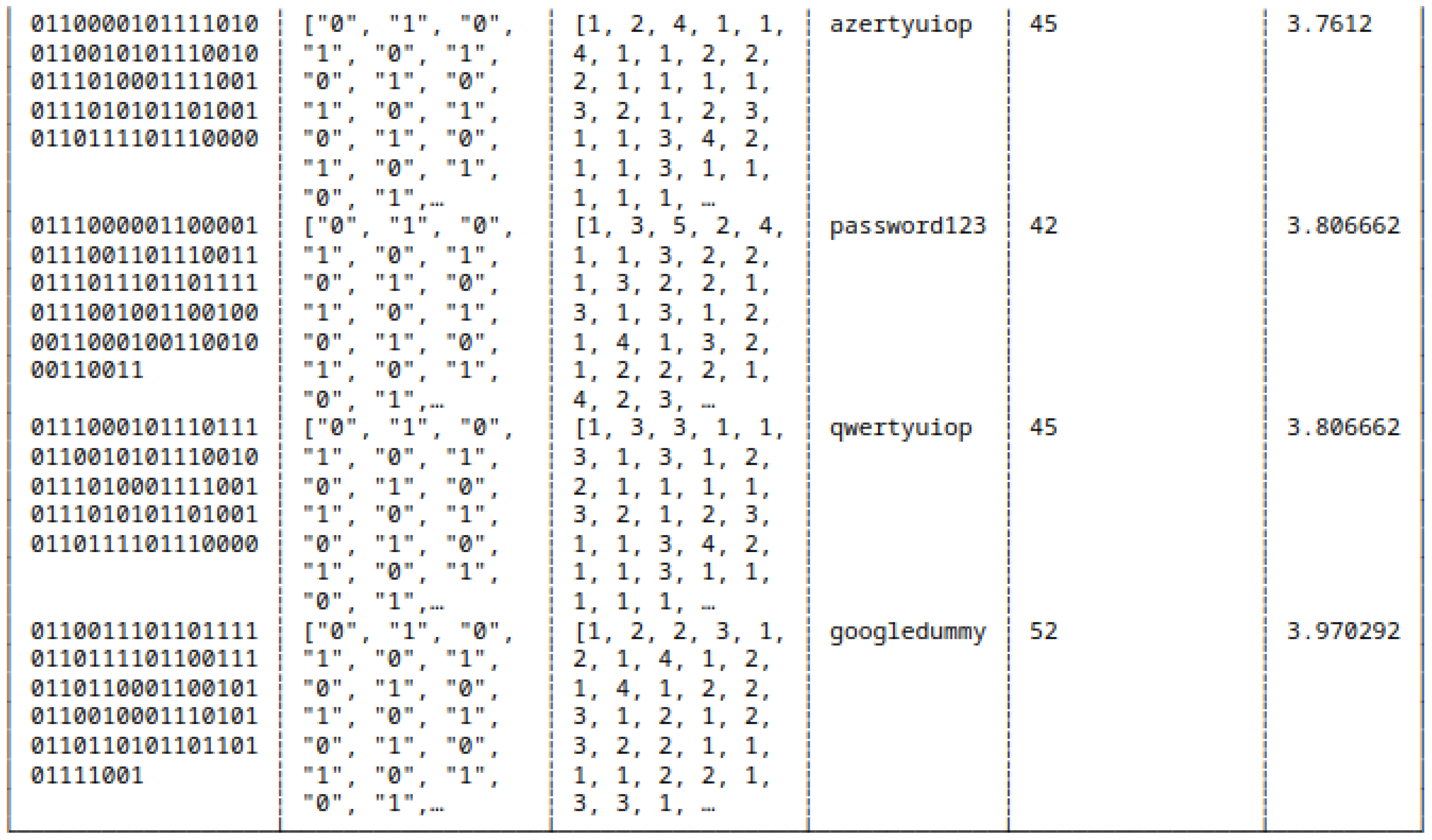

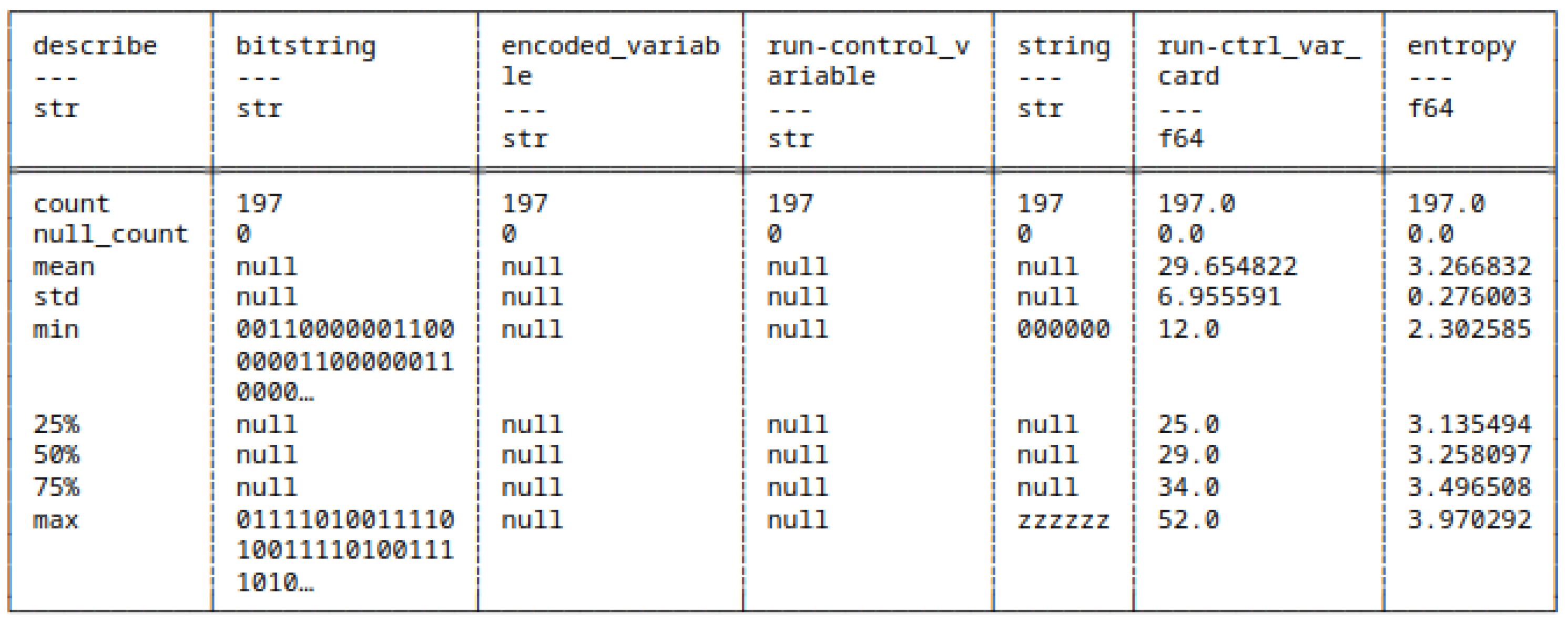

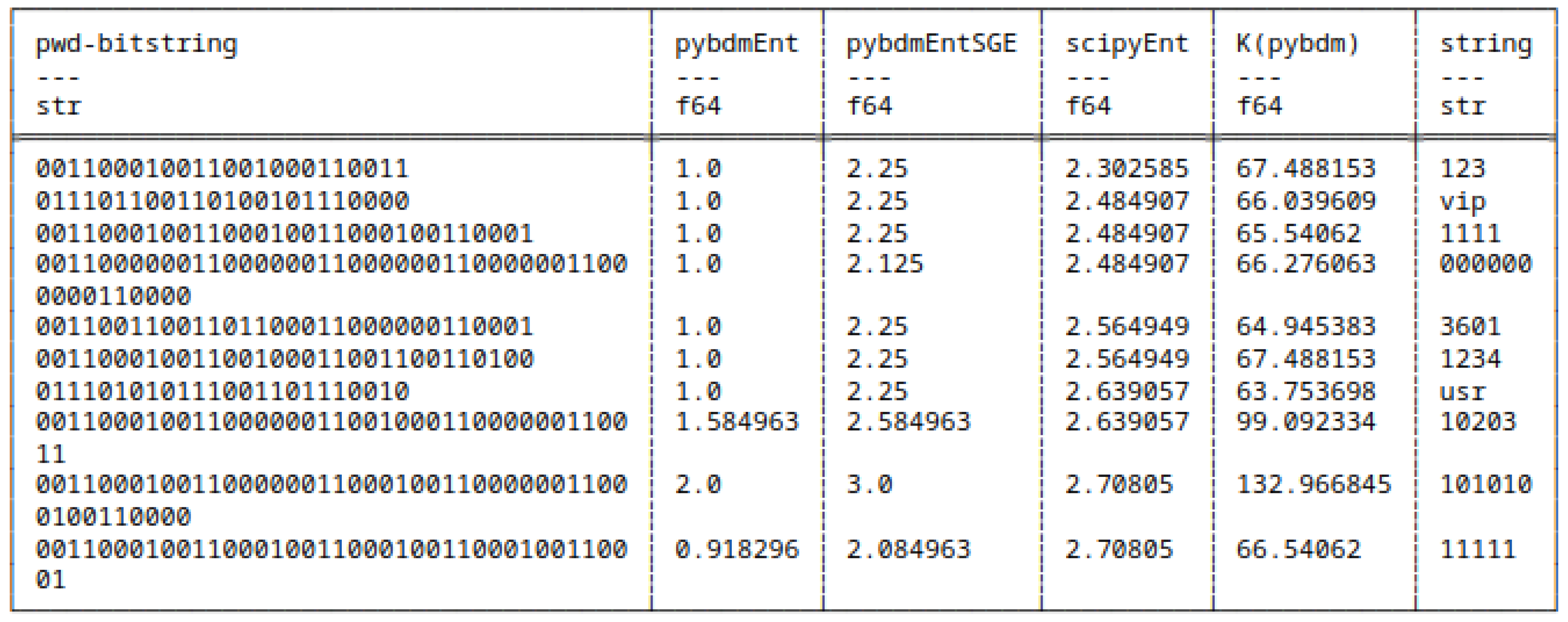

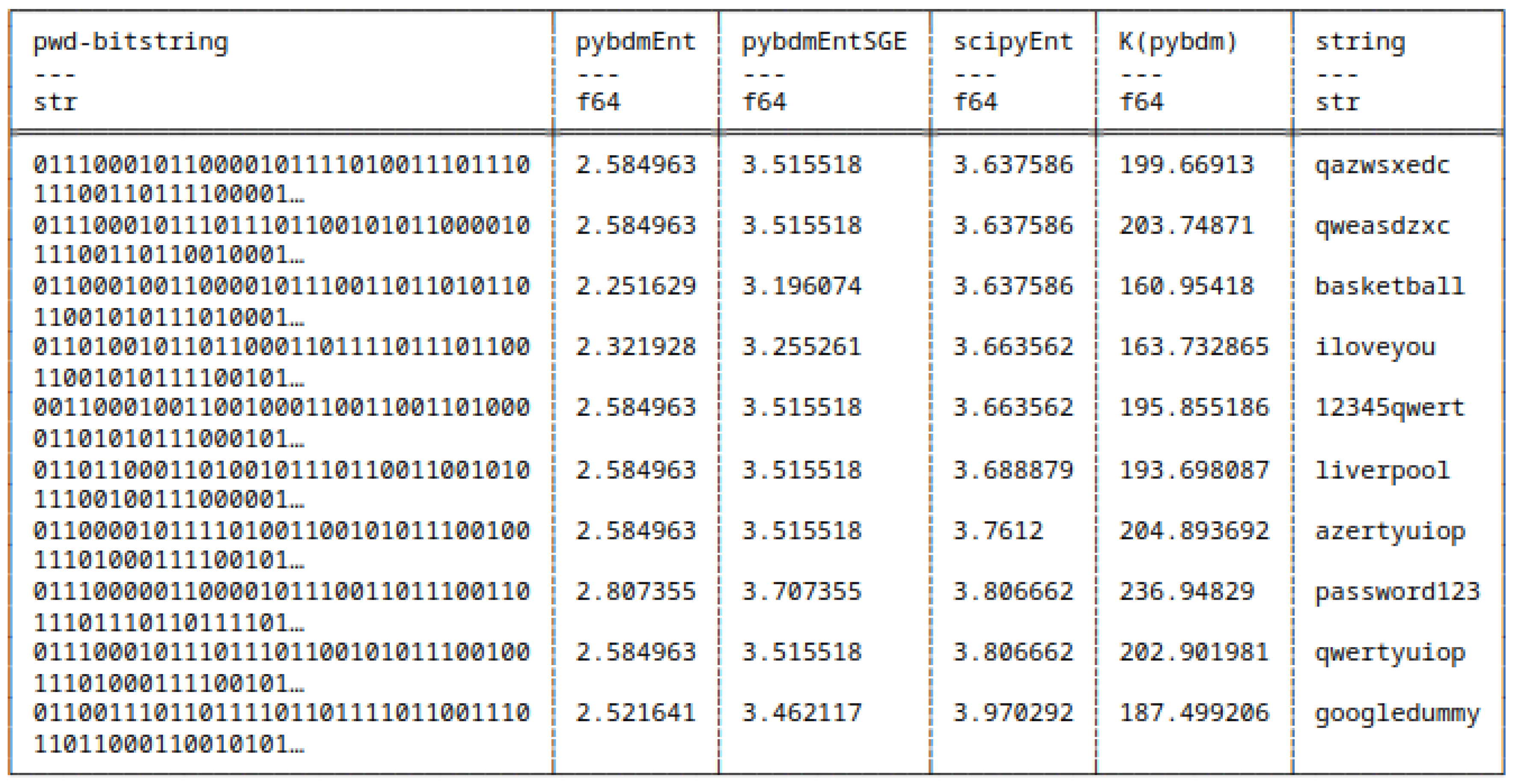

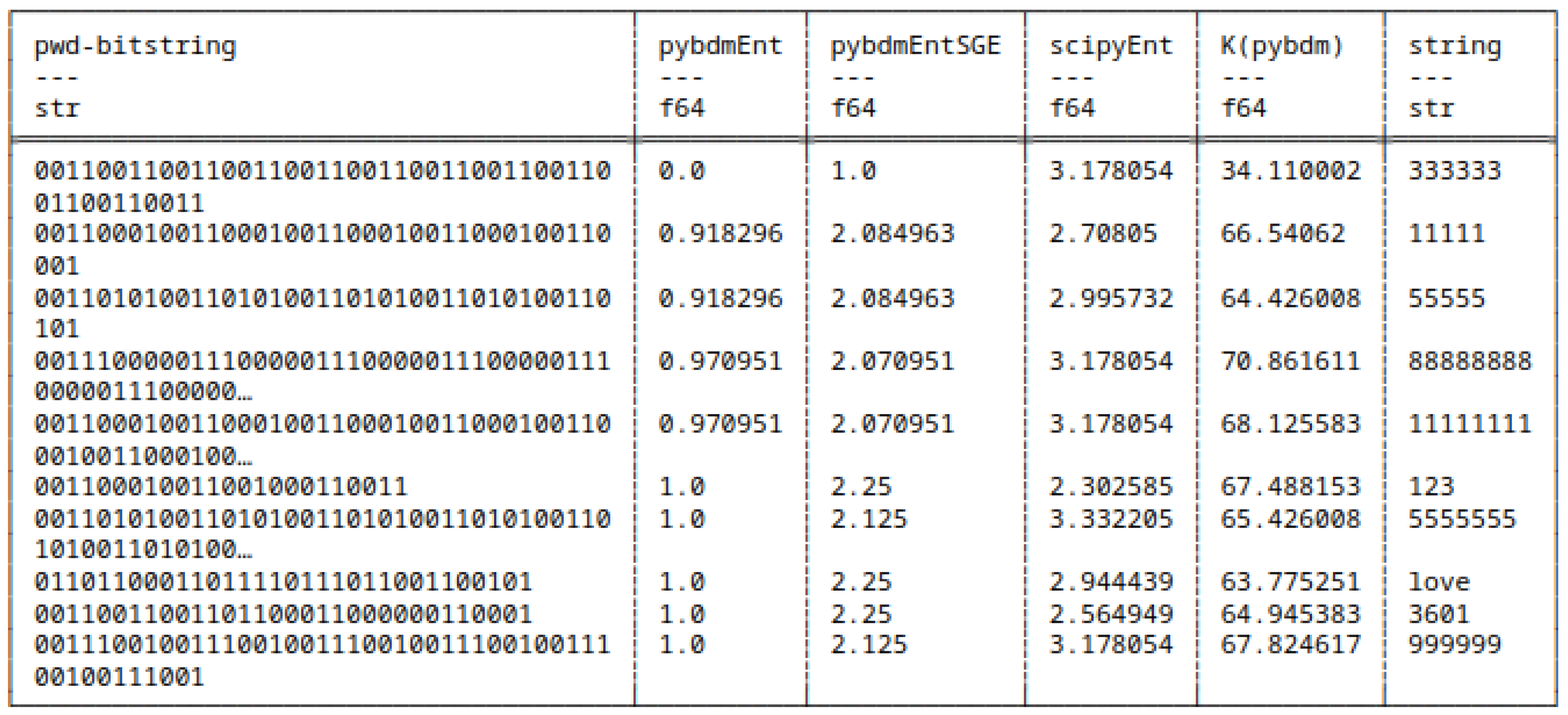

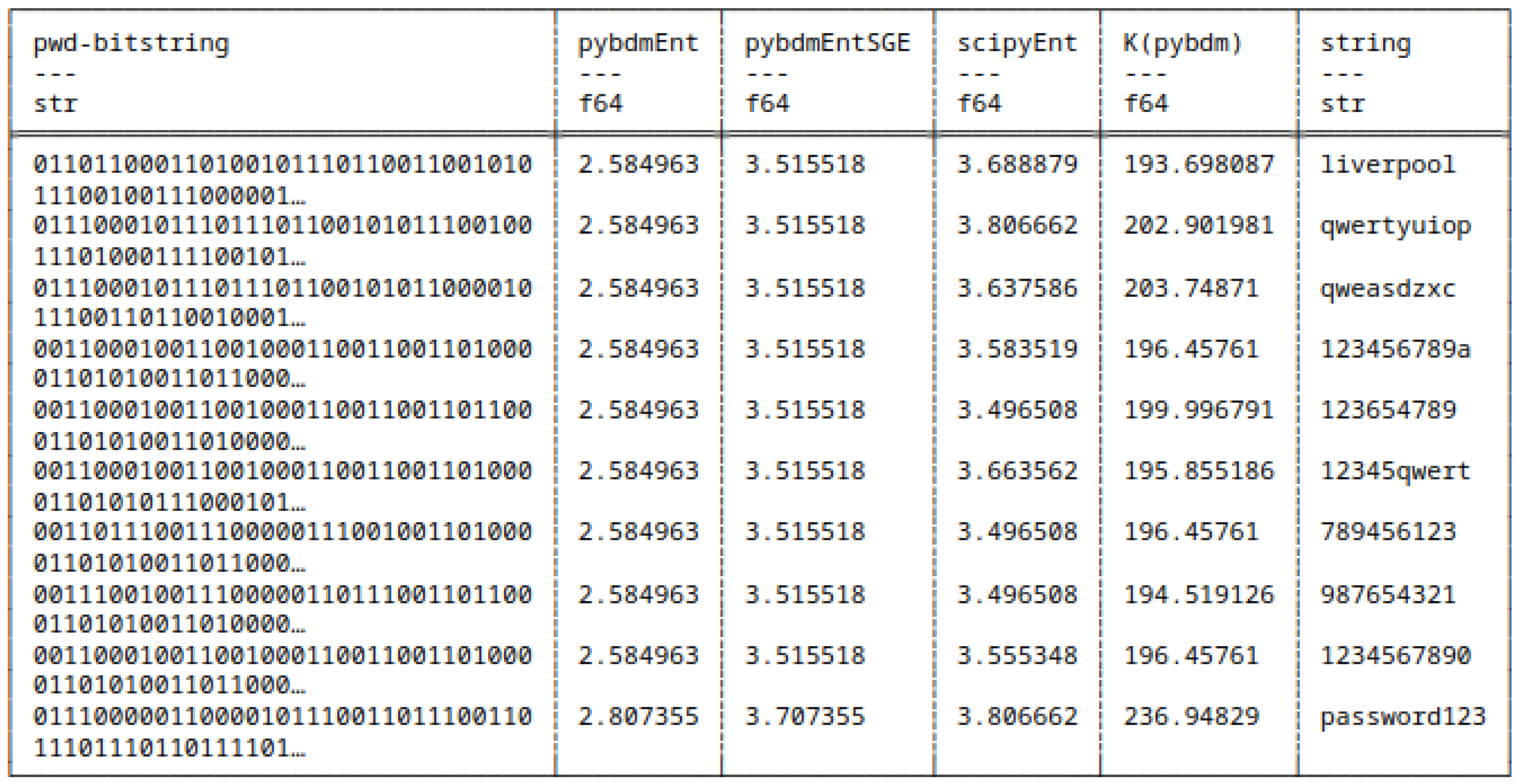

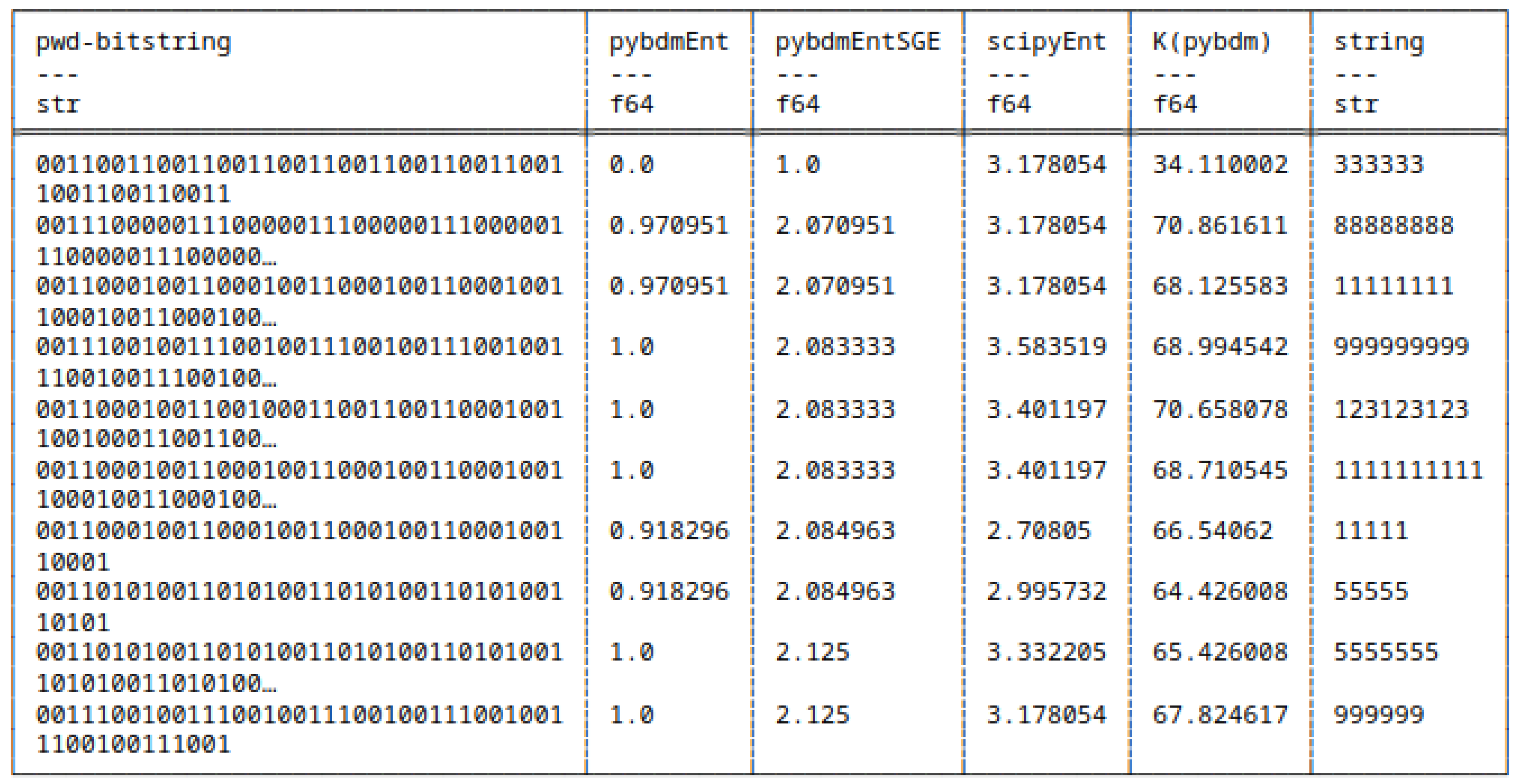

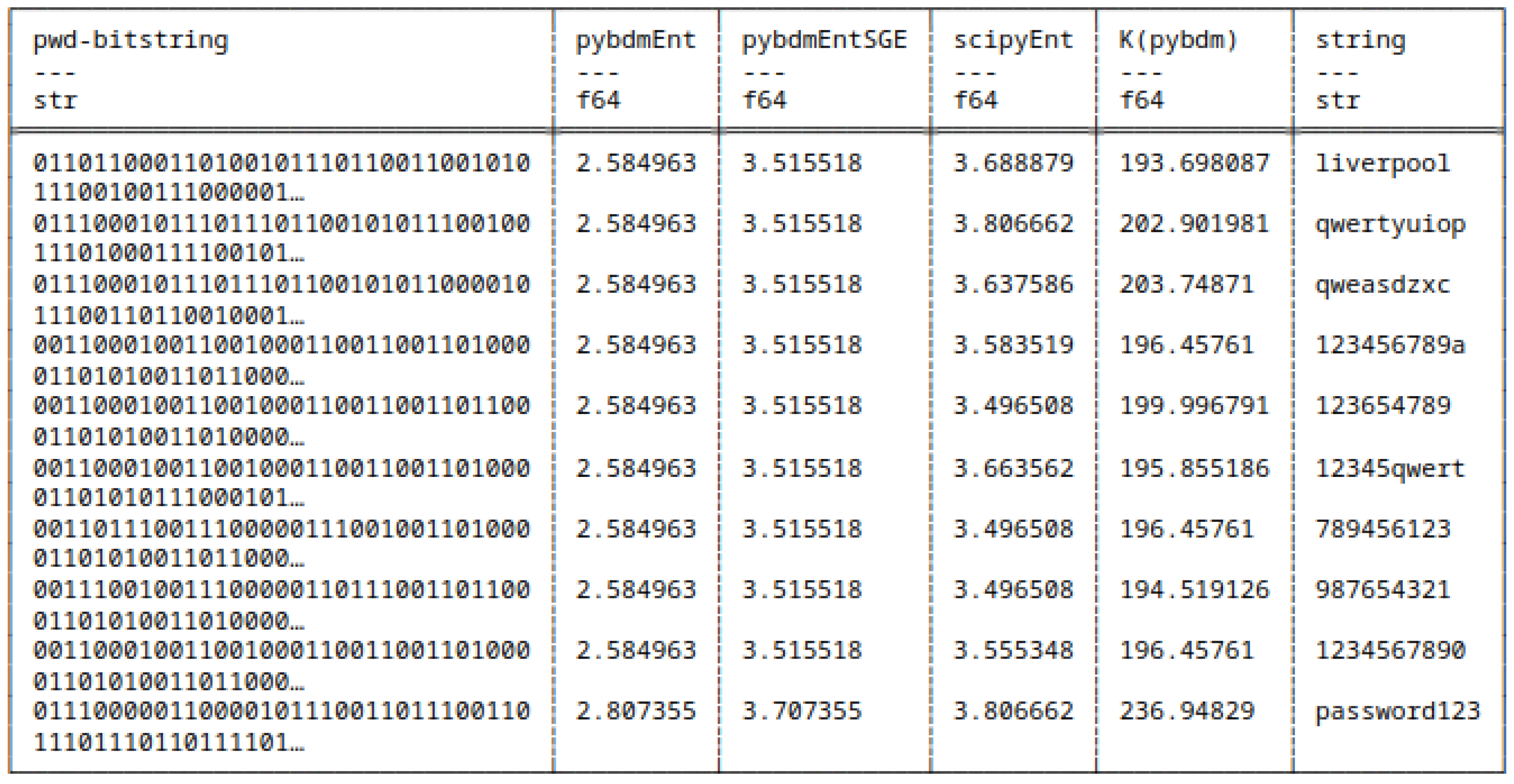

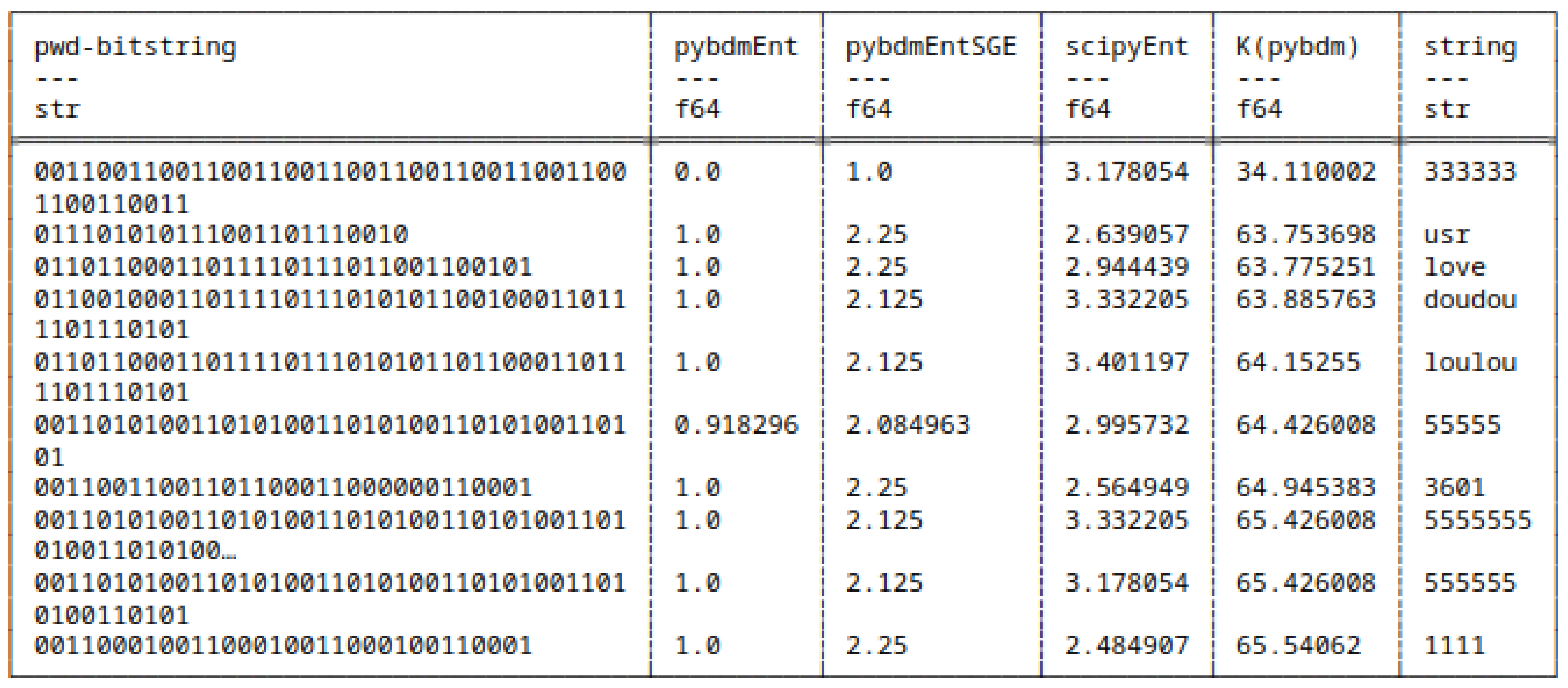

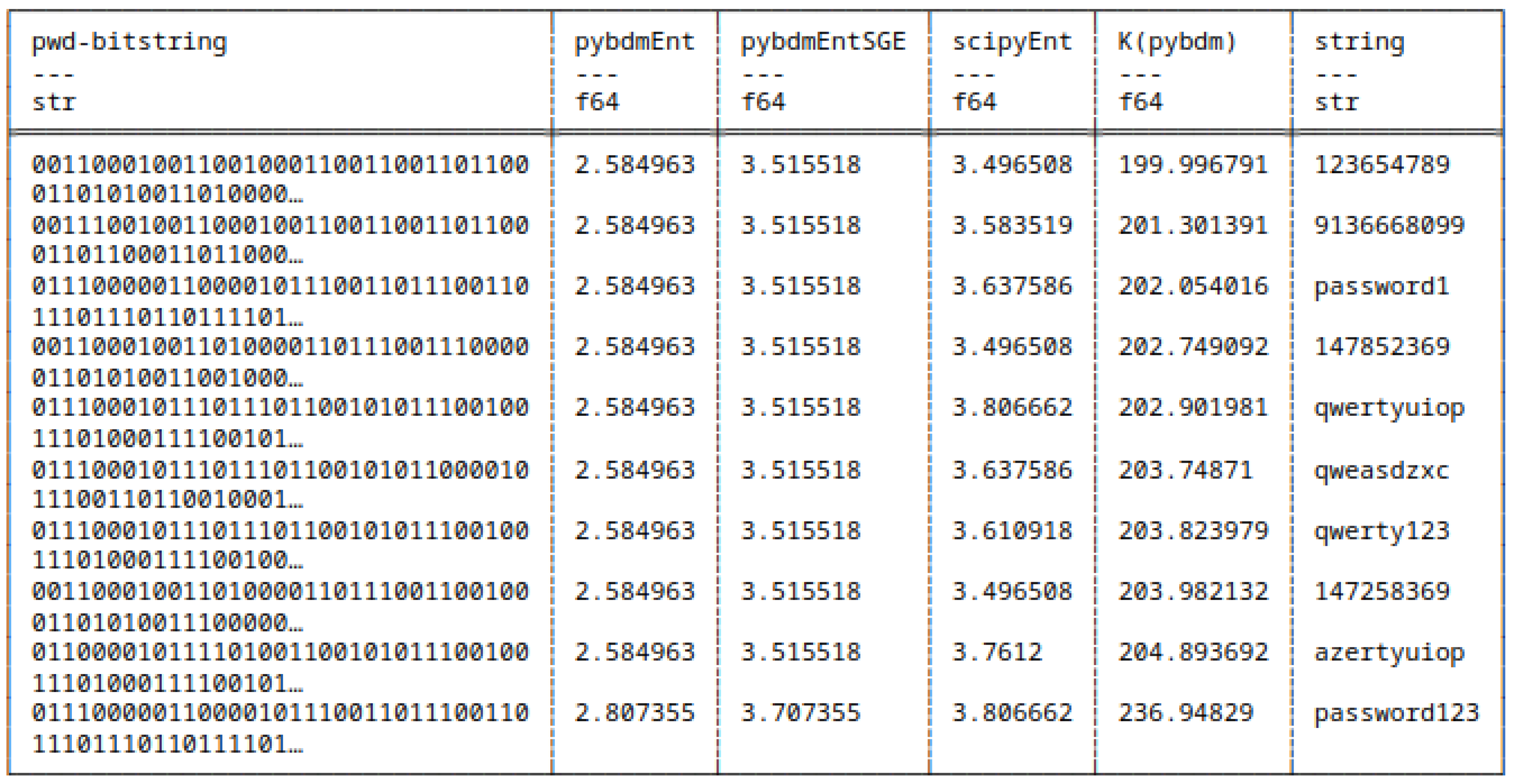

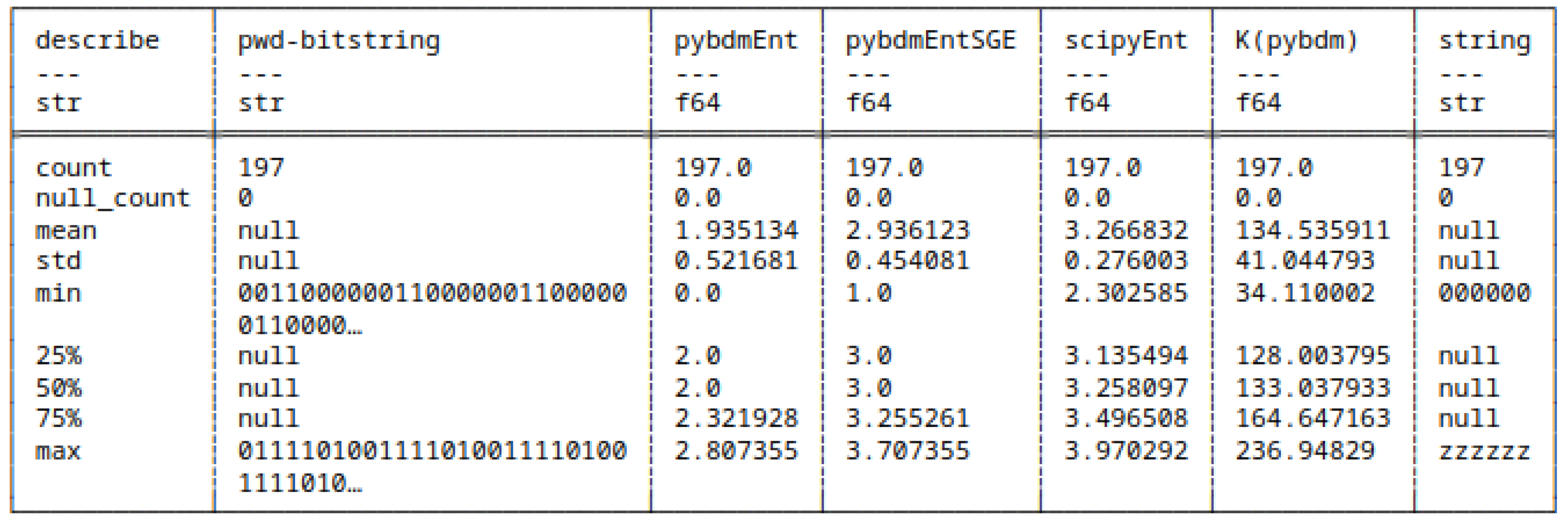

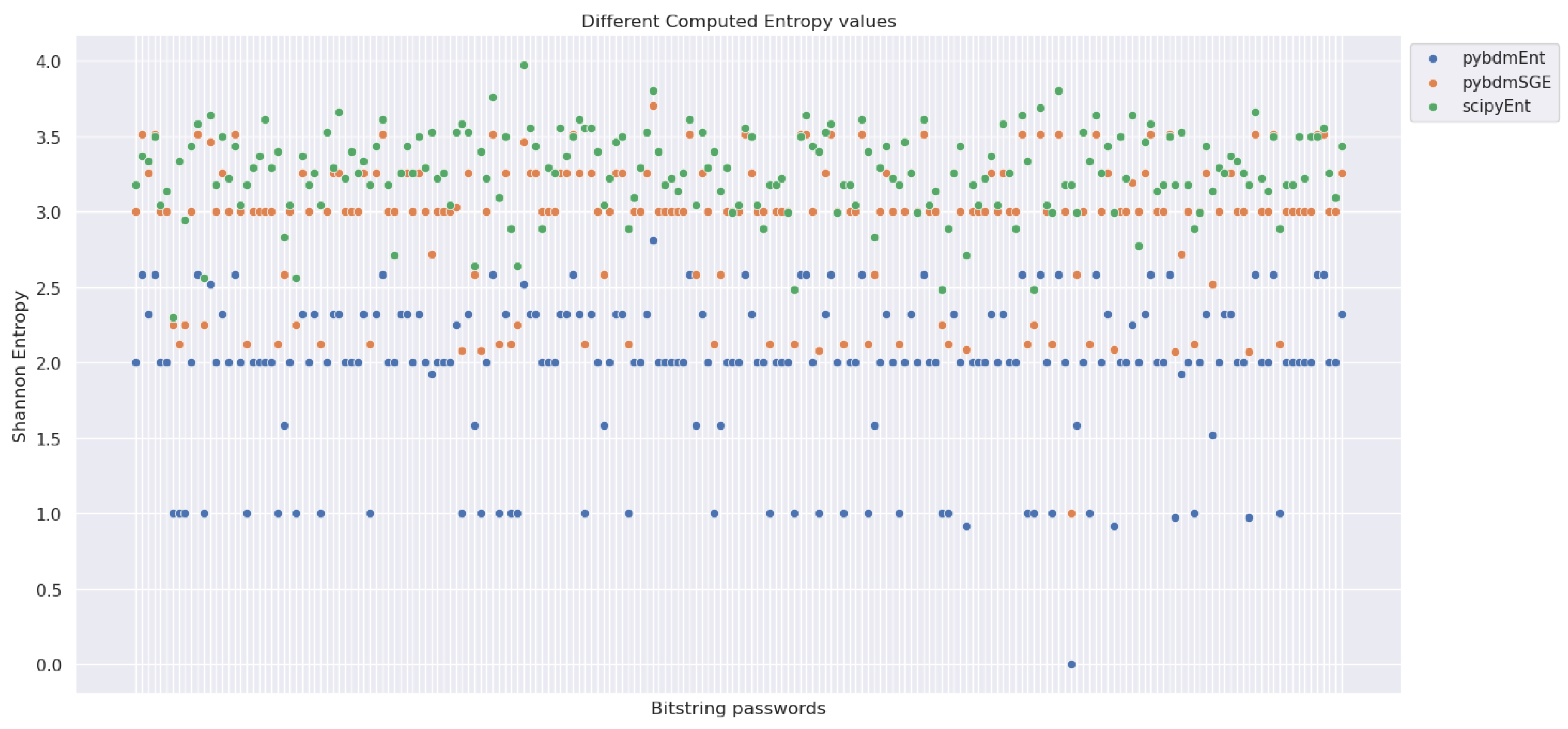

5.4. Strings as Bitstrings

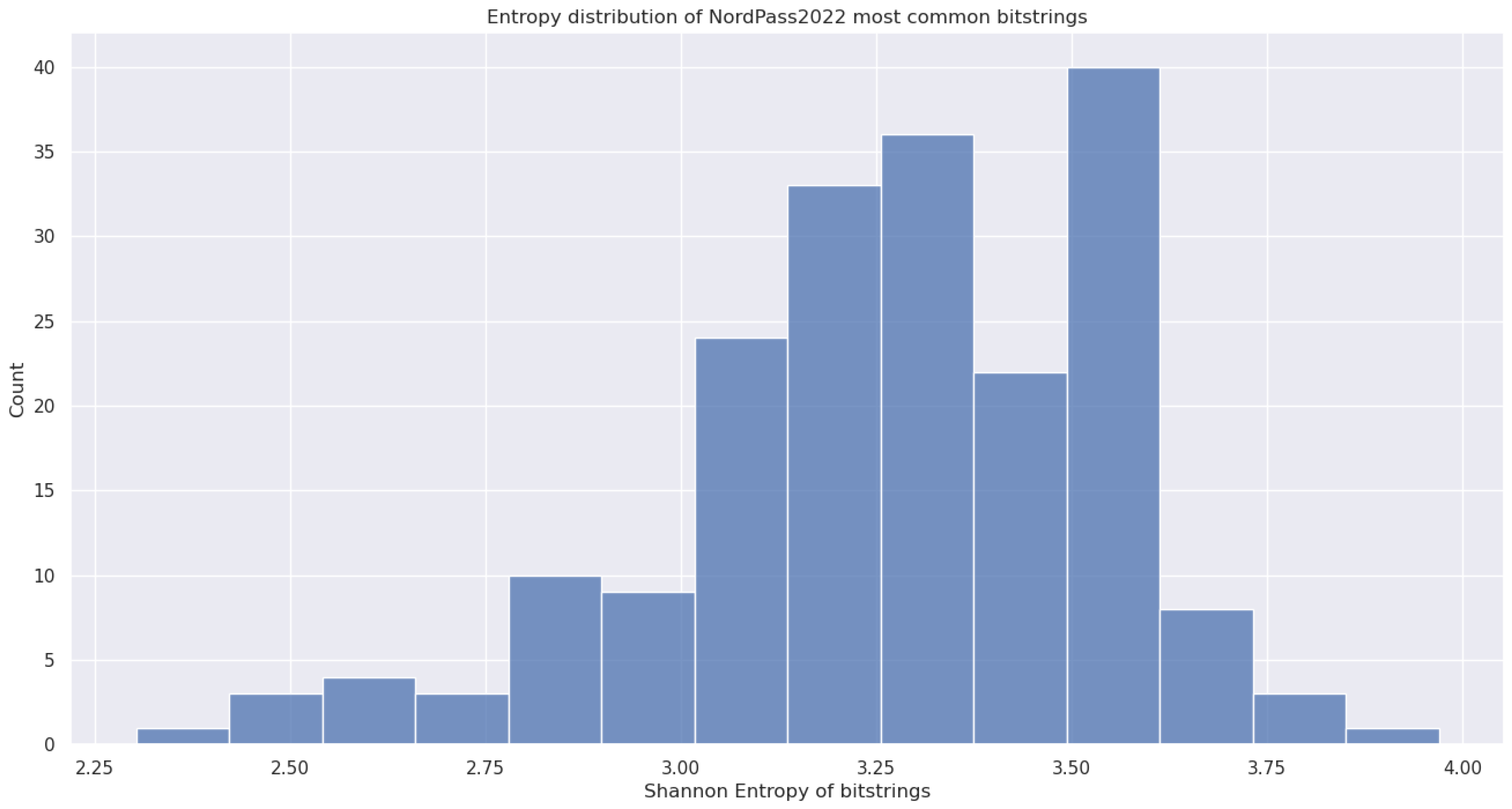

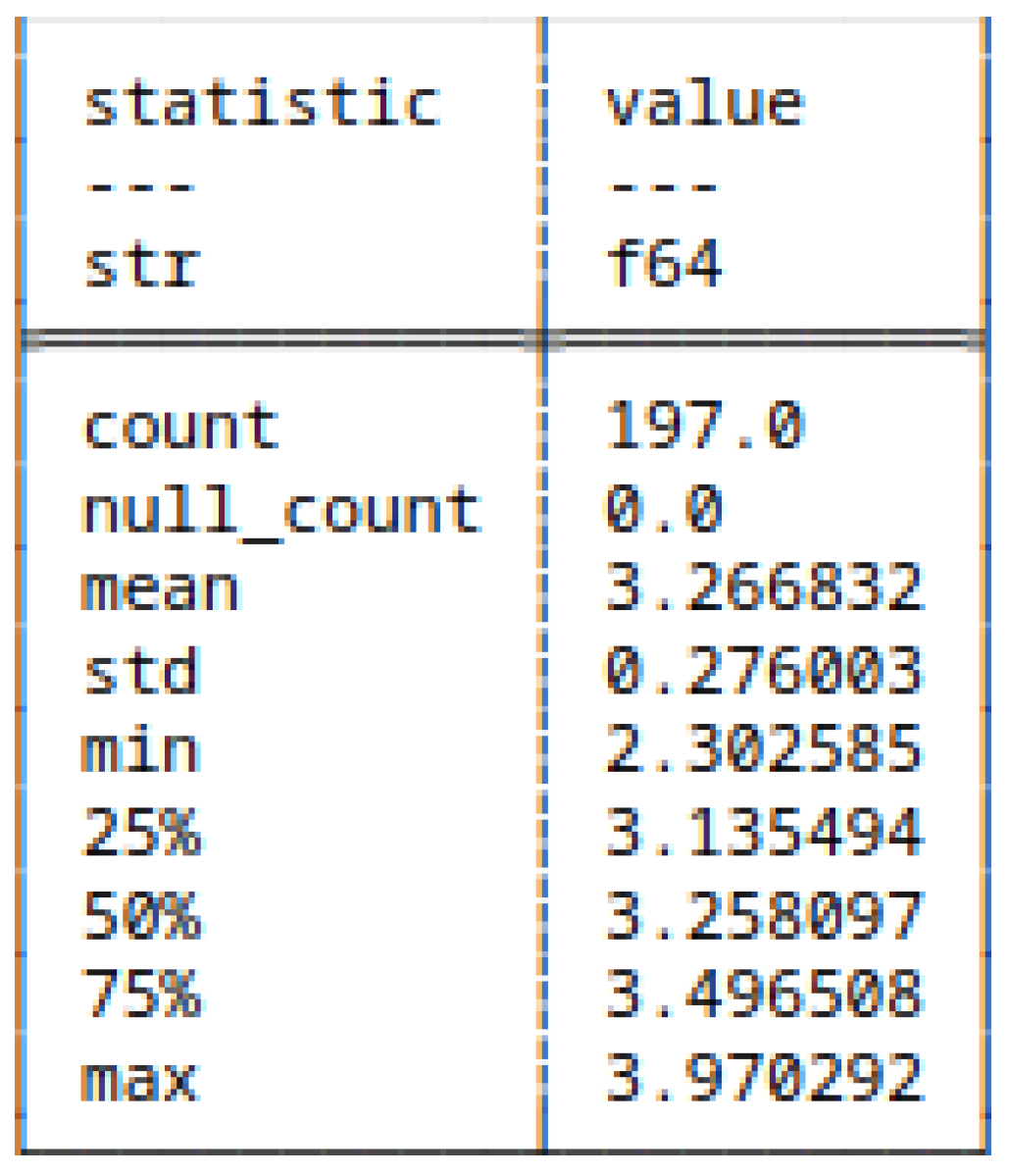

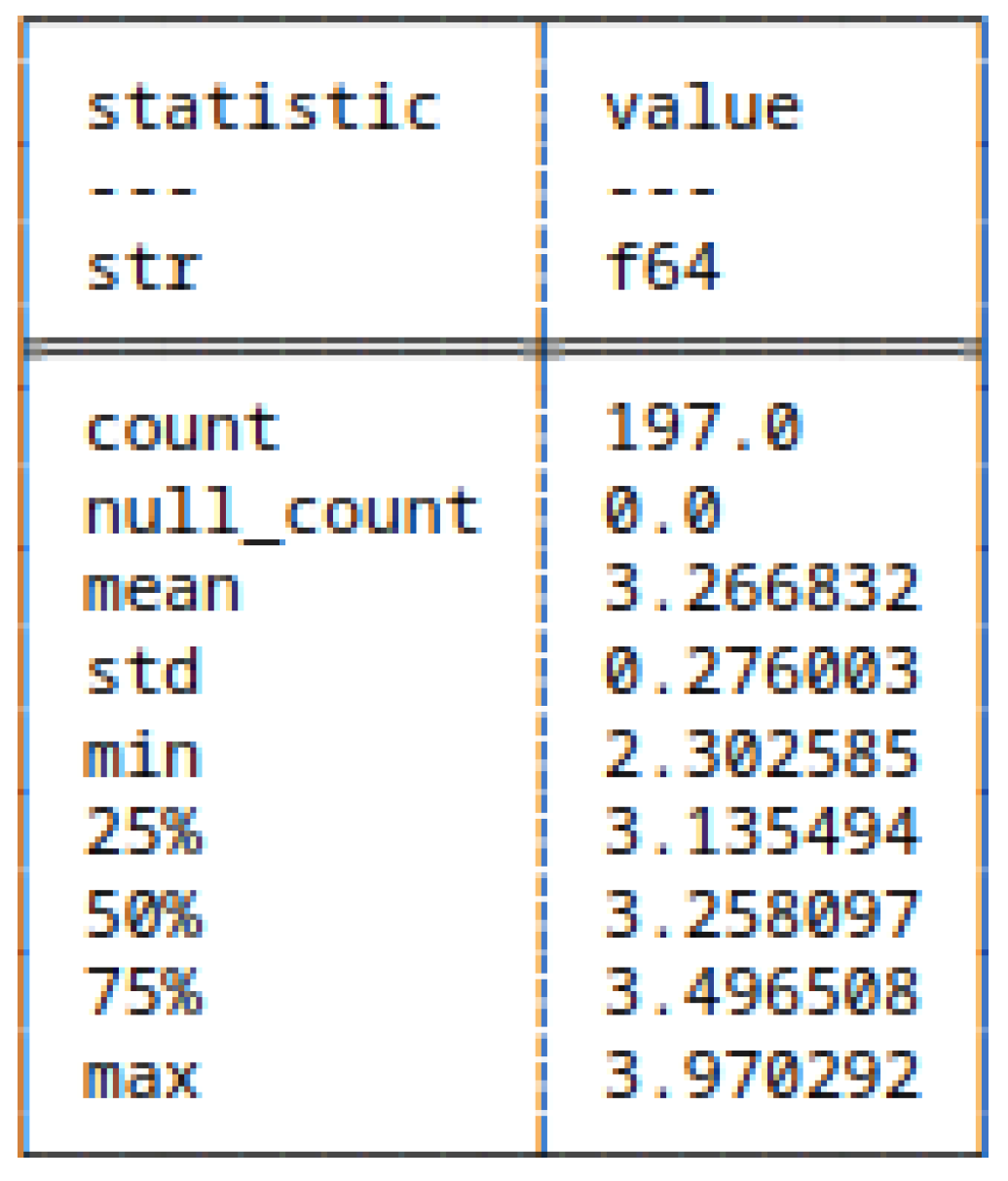

5.4.1. (7) - Shannon Entropy of Bitstrings

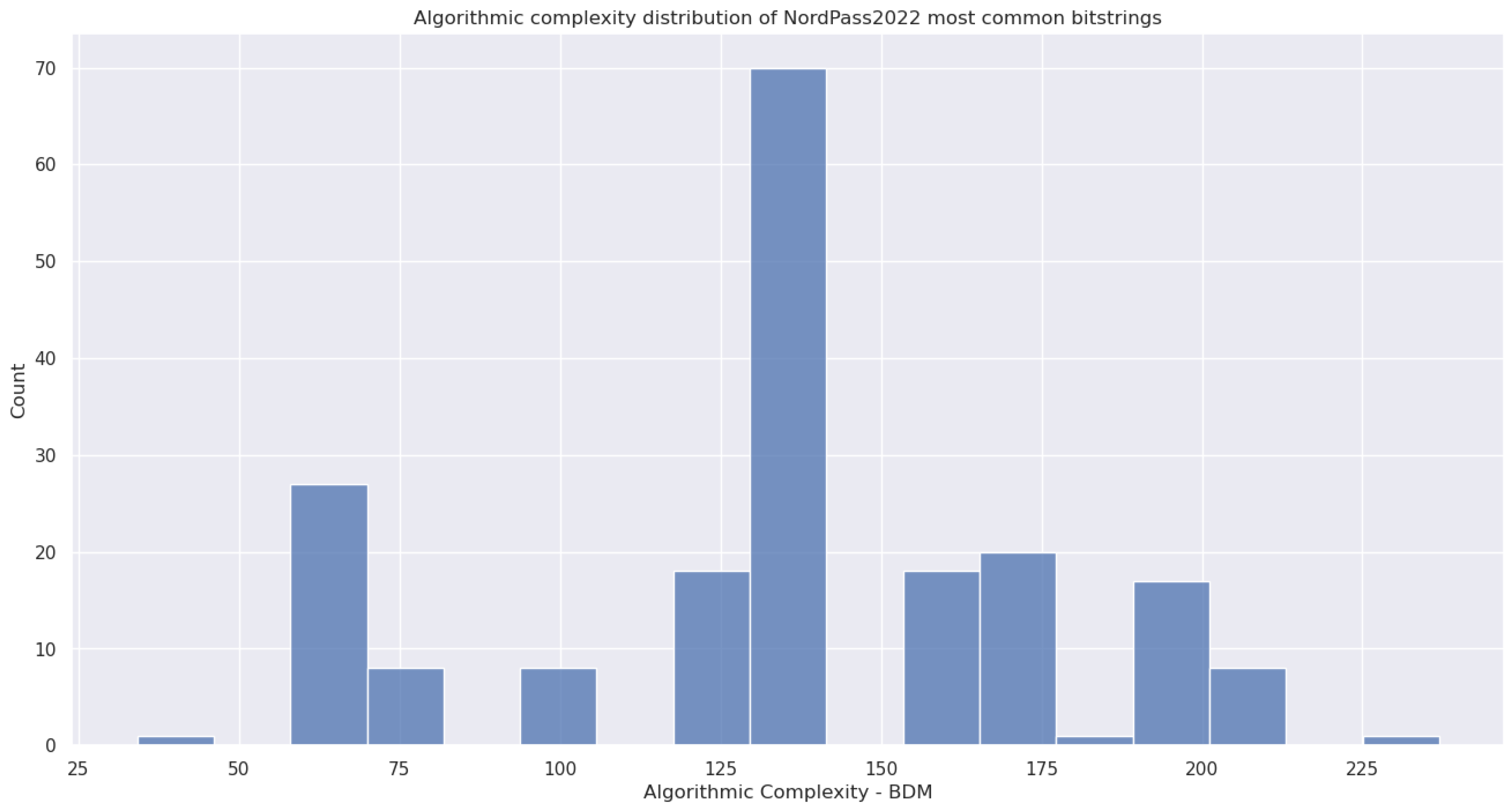

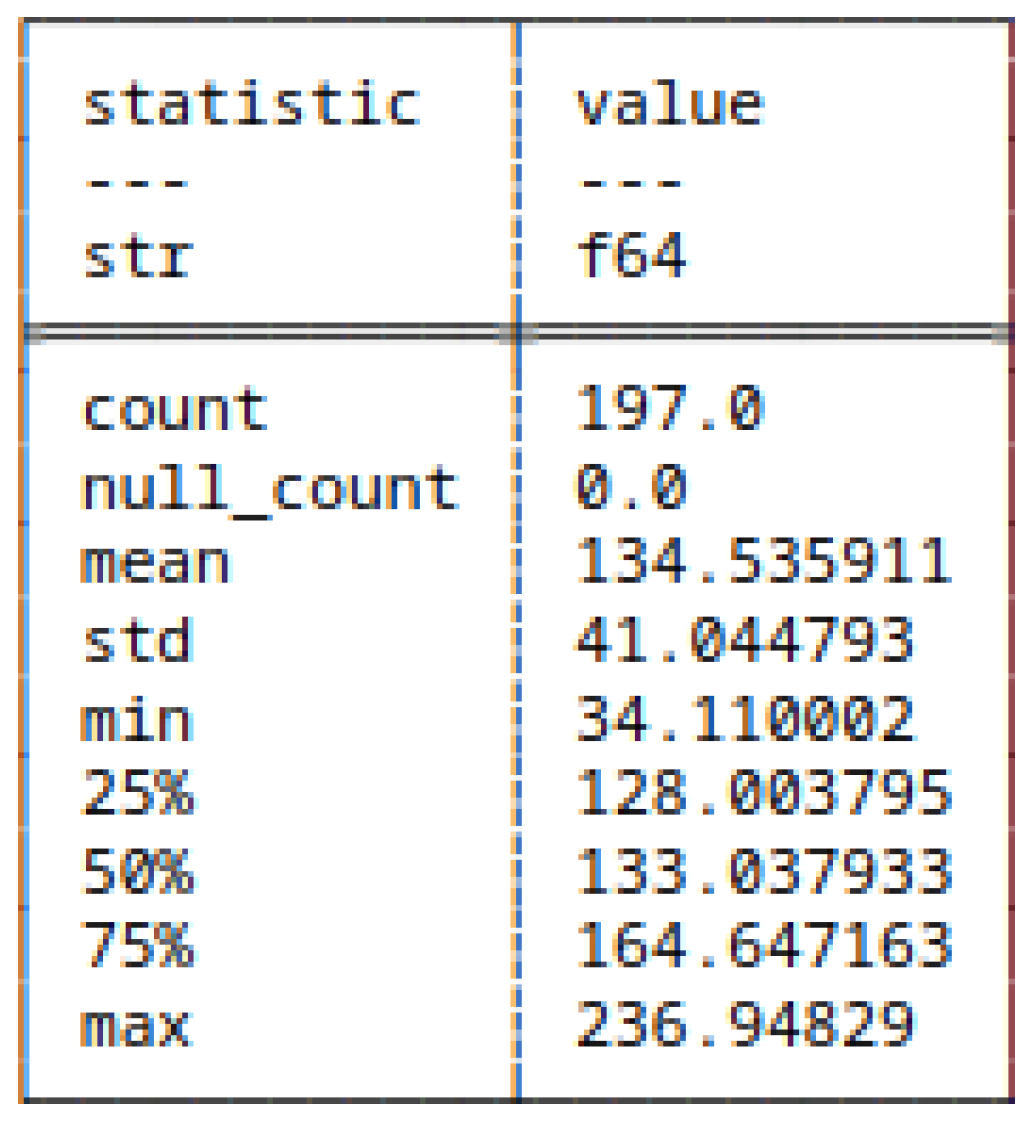

5.4.2. (8) - Block Decomposition Method Applied to Bitstrings

5.4.3. (9) - Run-Length Encoding Applied to Bitstrings

5.4.4. (10) - Huffman Coding Applied to Bitstrings

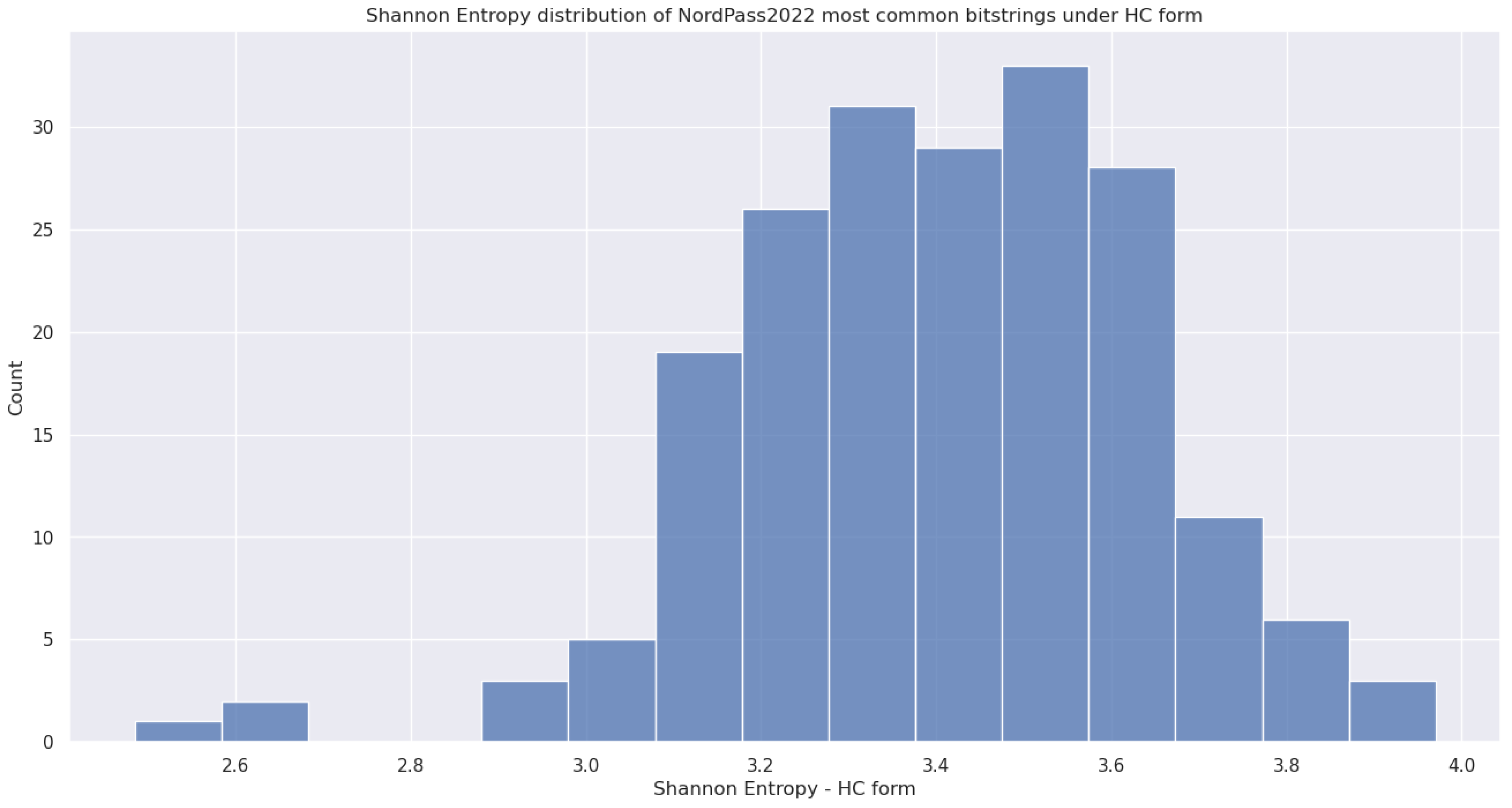

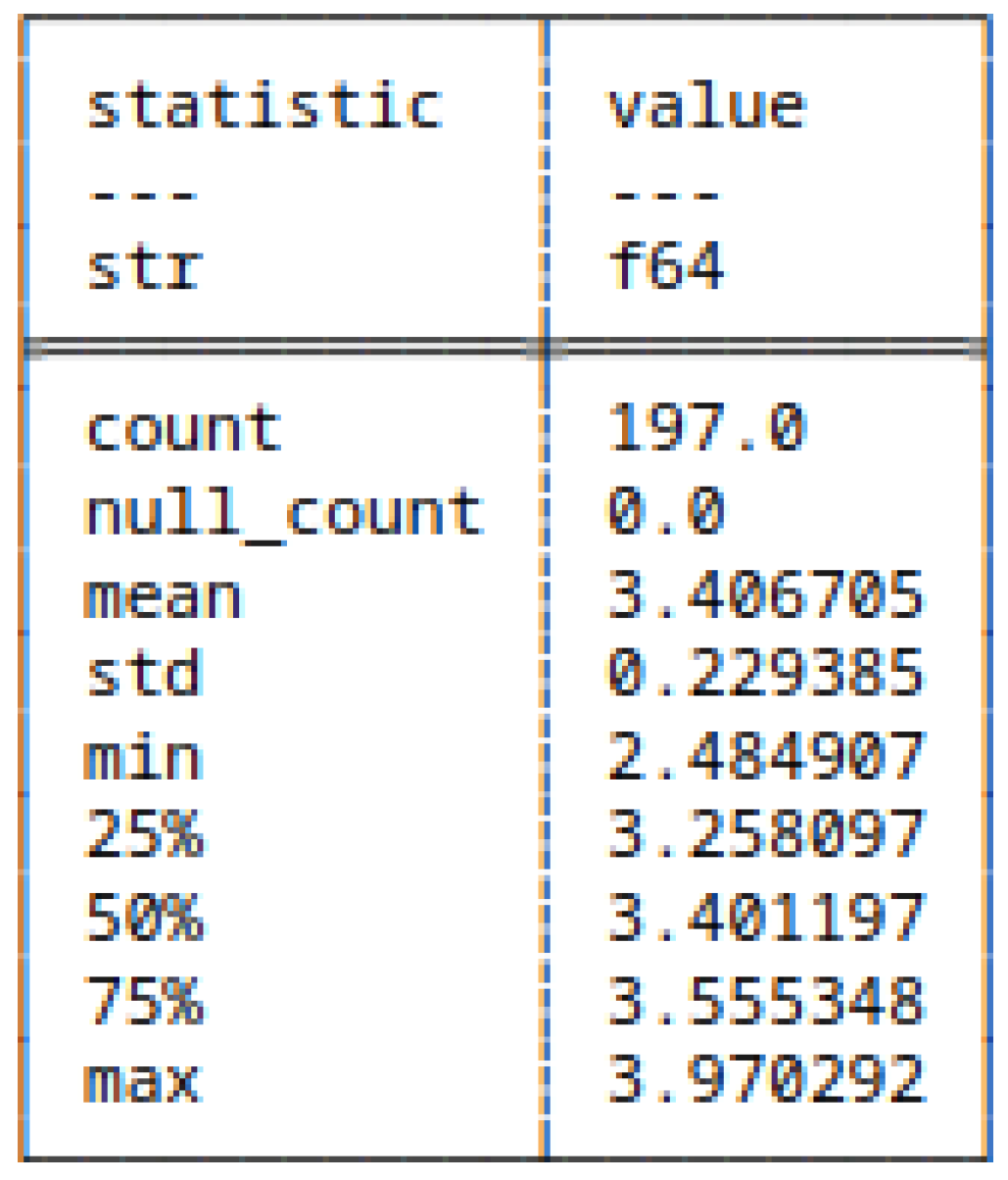

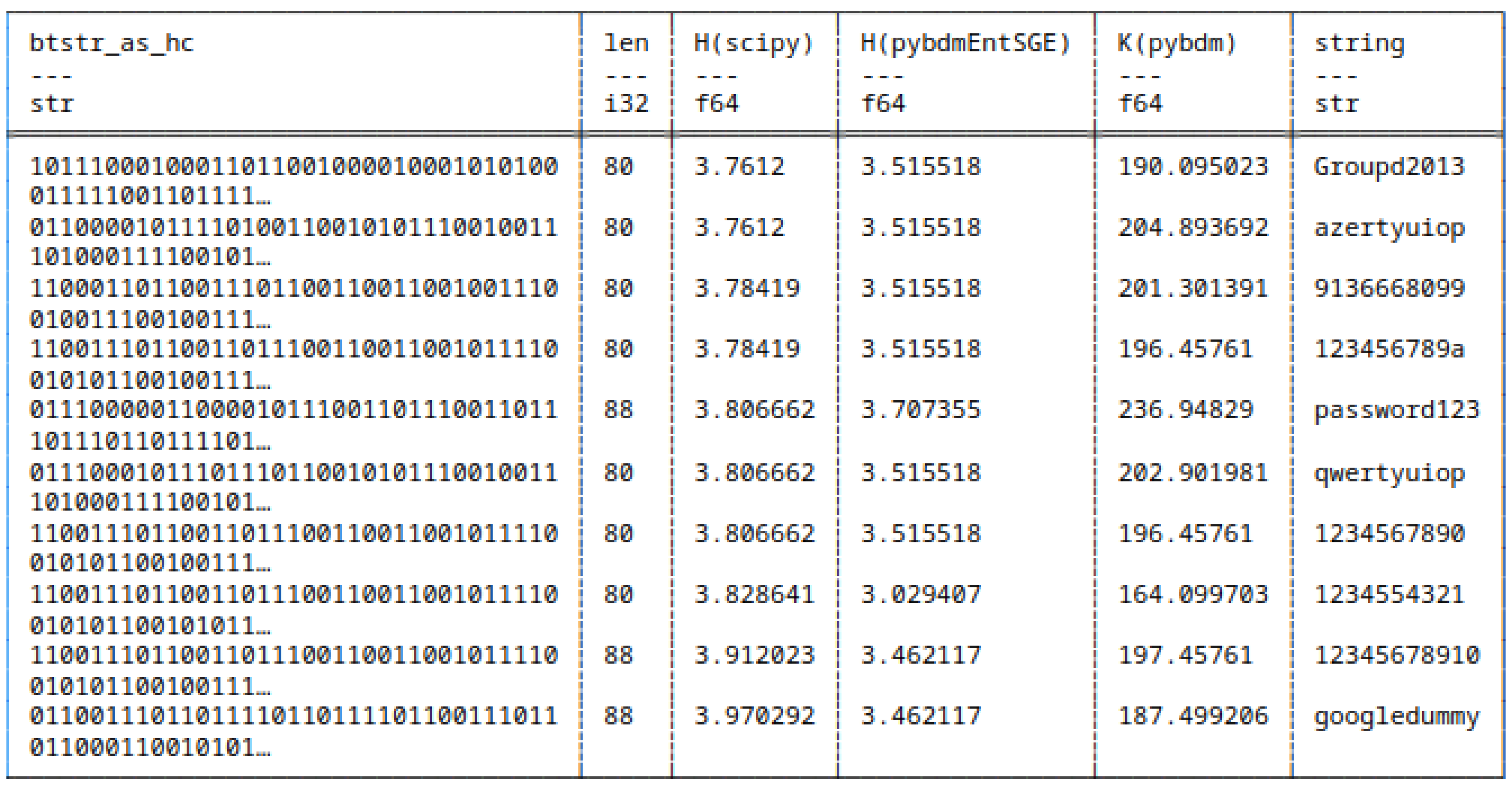

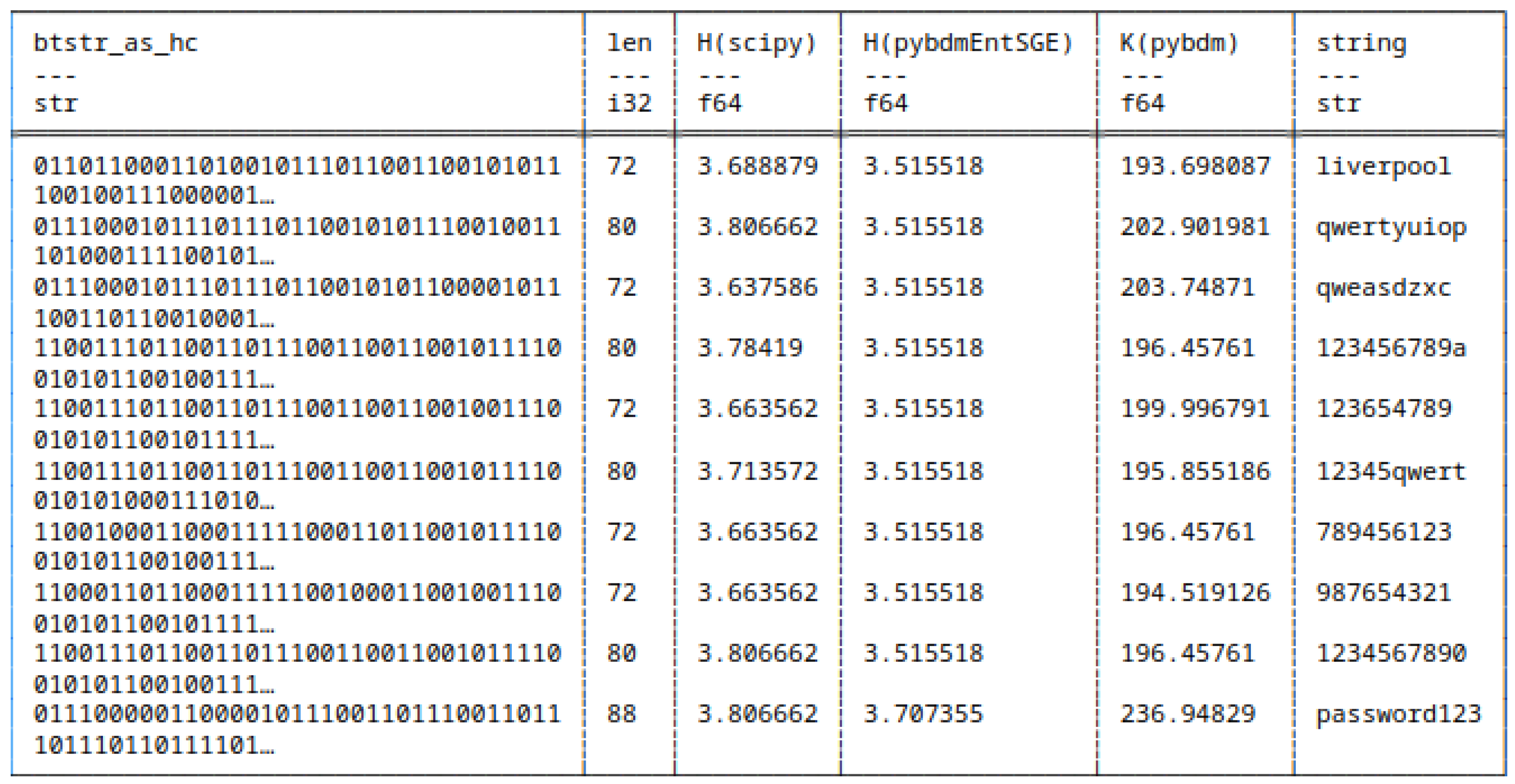

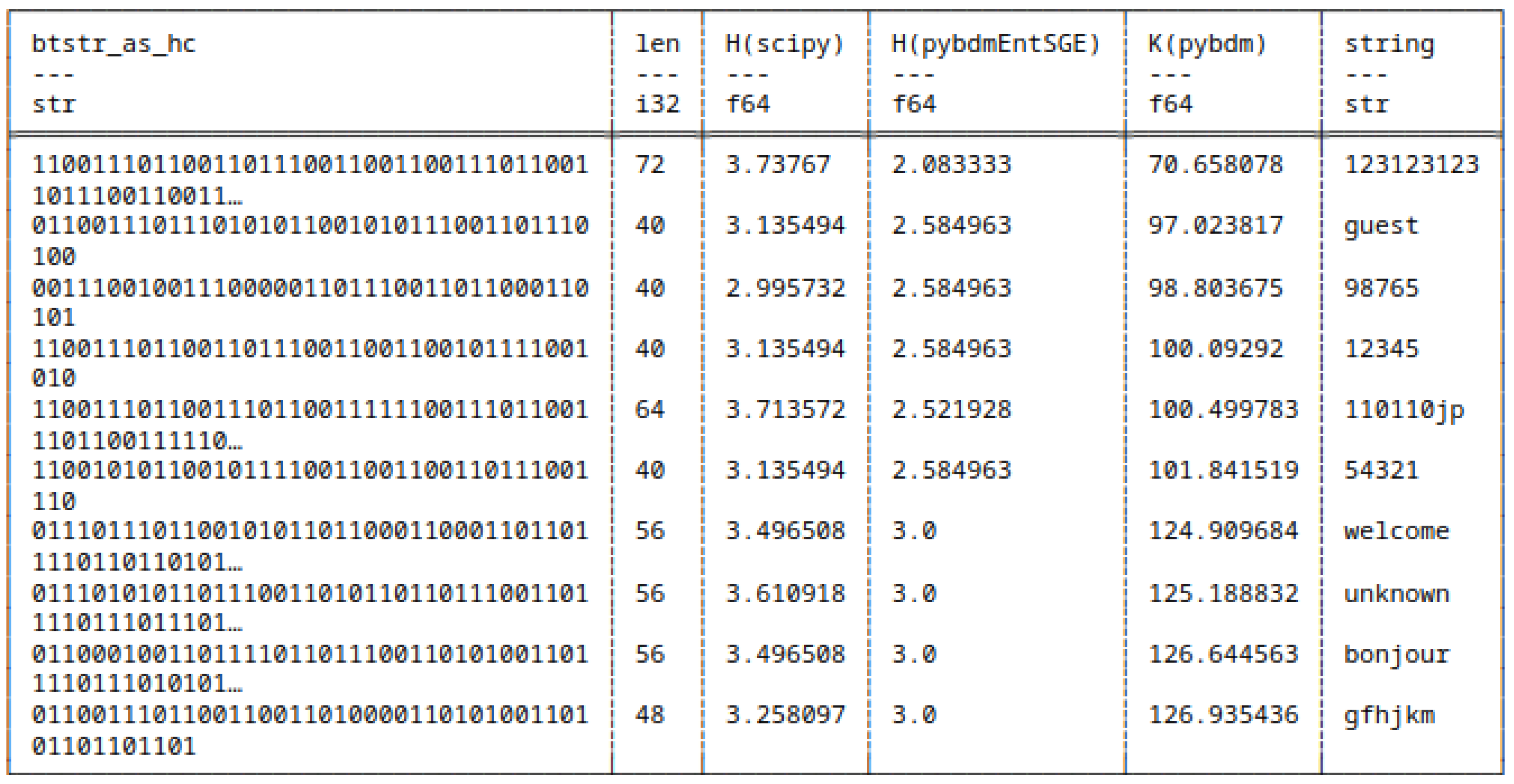

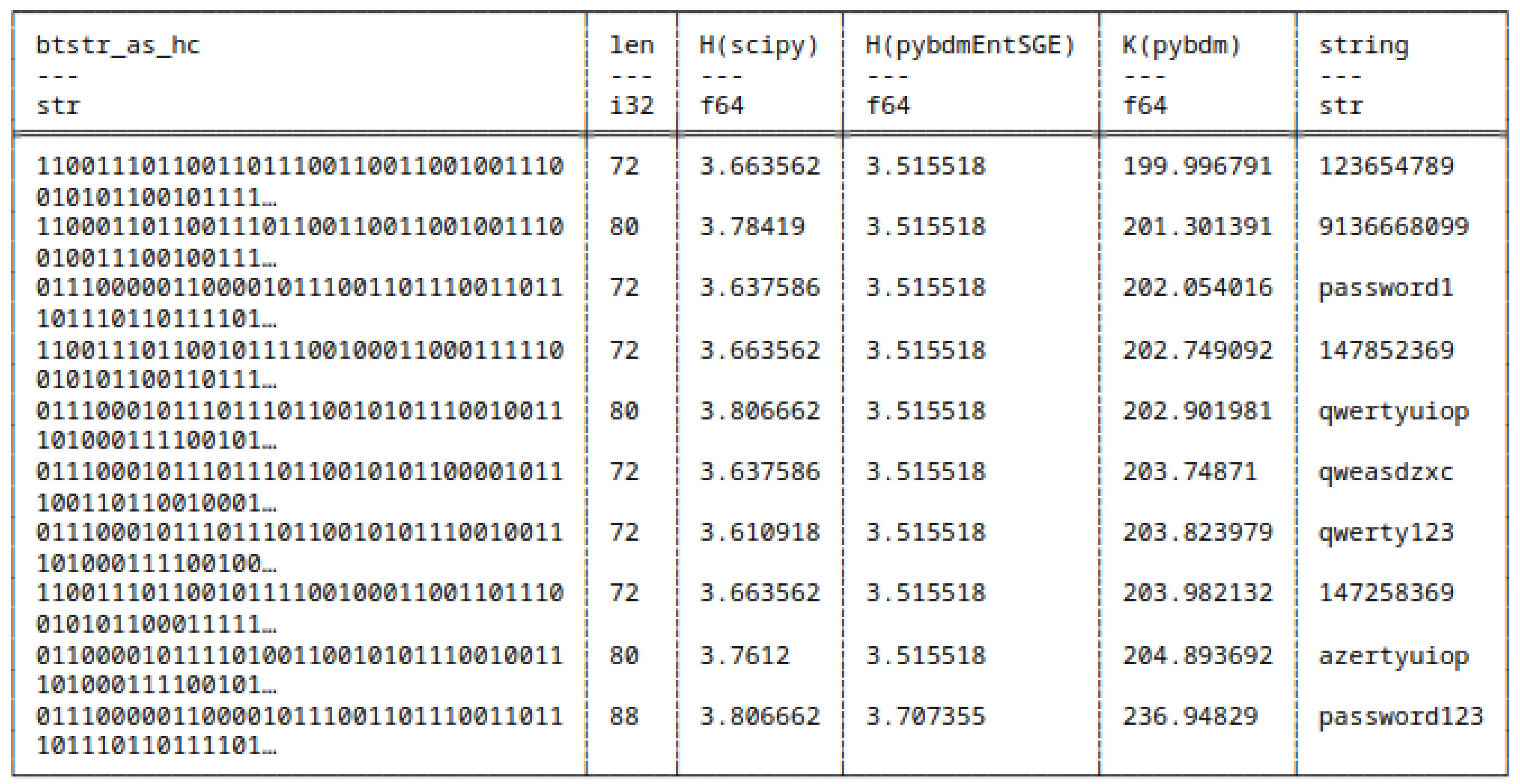

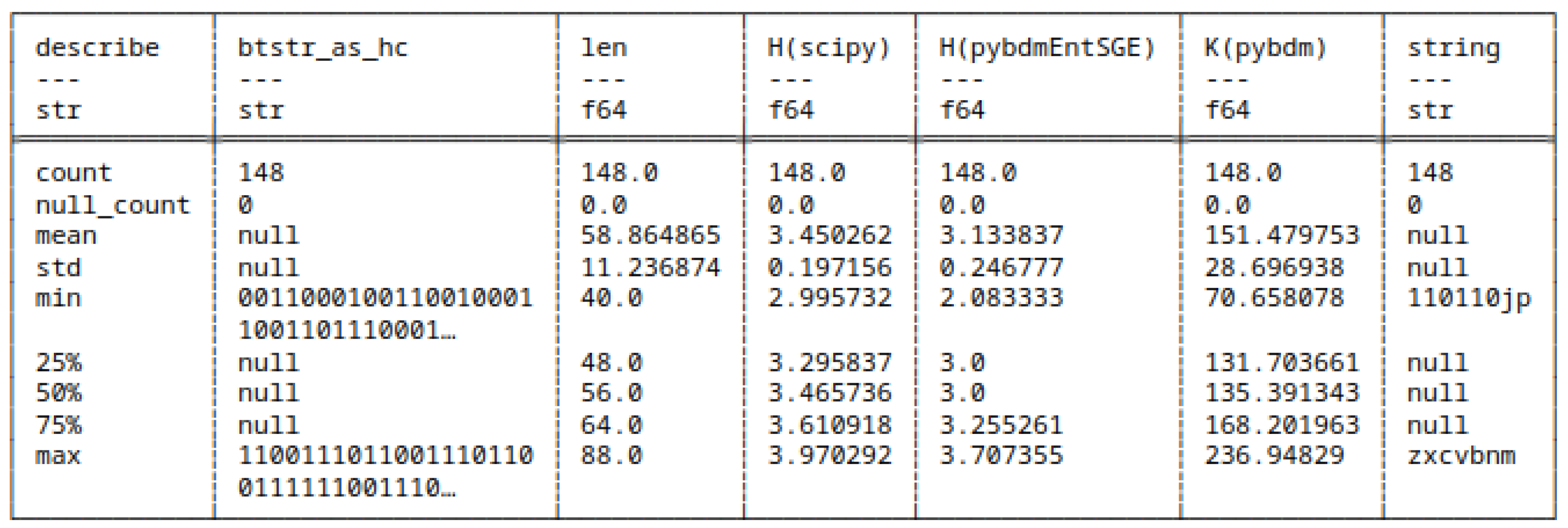

5.4.5. (11) - Shannon Entropy Applied to HC

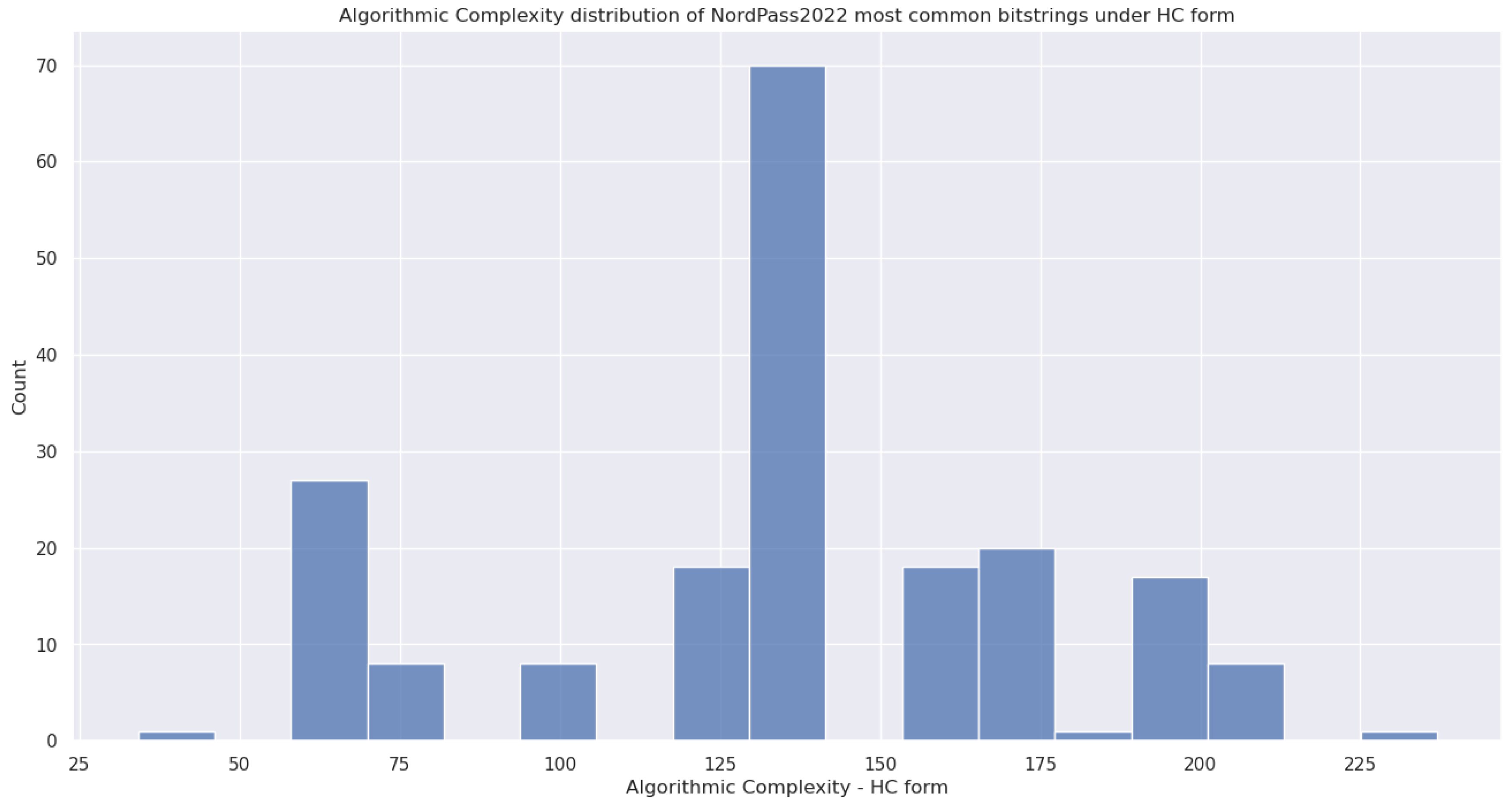

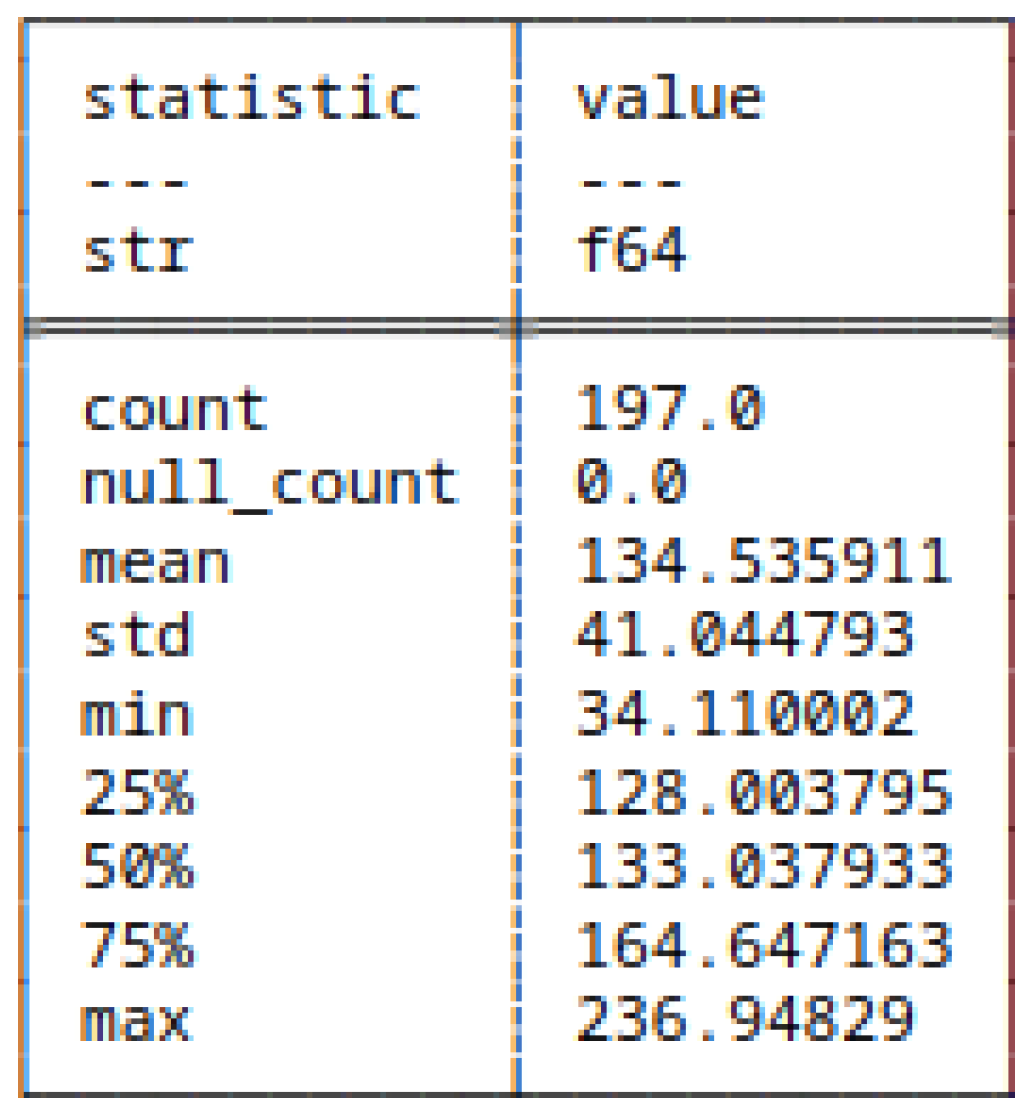

5.4.6. (12) - Block Decomposition Method Applied to HC

5.5. Shannon Entropy of Strings and Bitstrings - t-Test

5.6. Run-Length Encoding of Strings and Bitstrings

5.7. Huffman Coding of Strings and Bitstrings

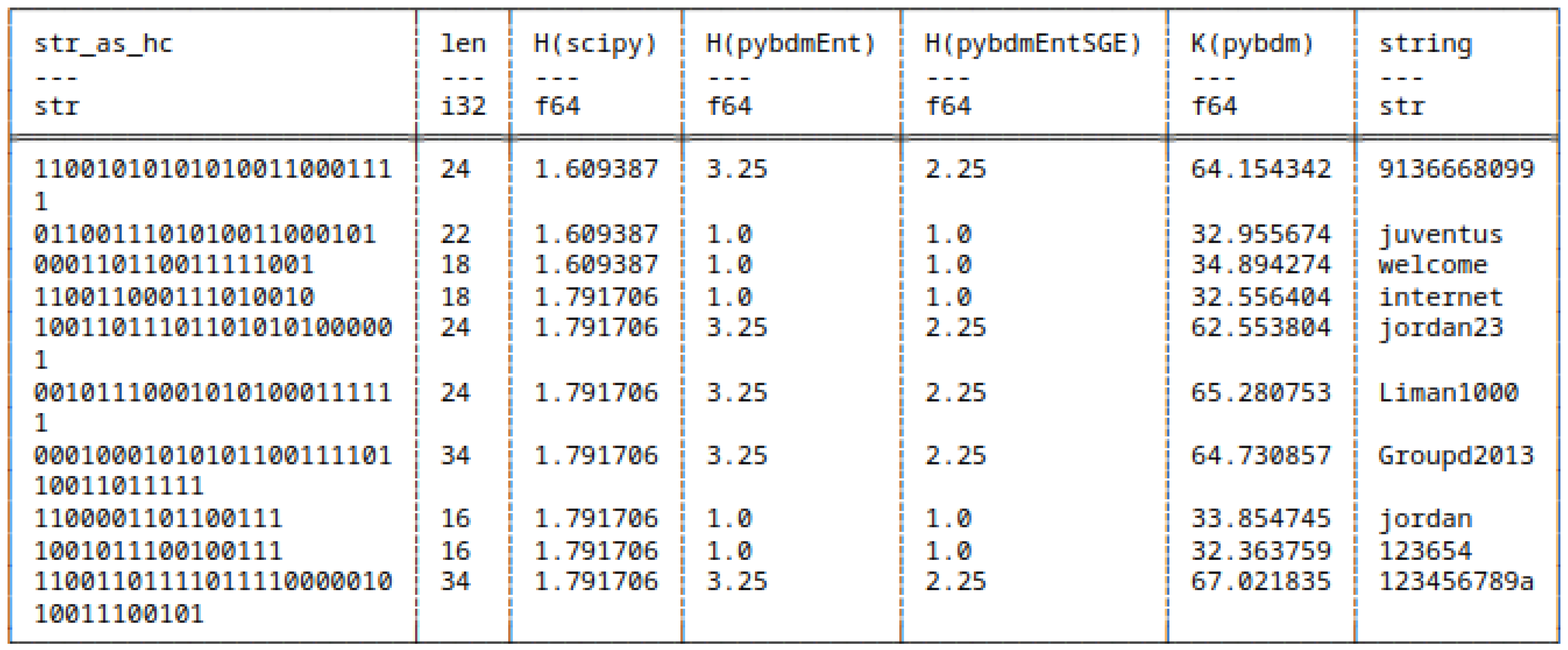

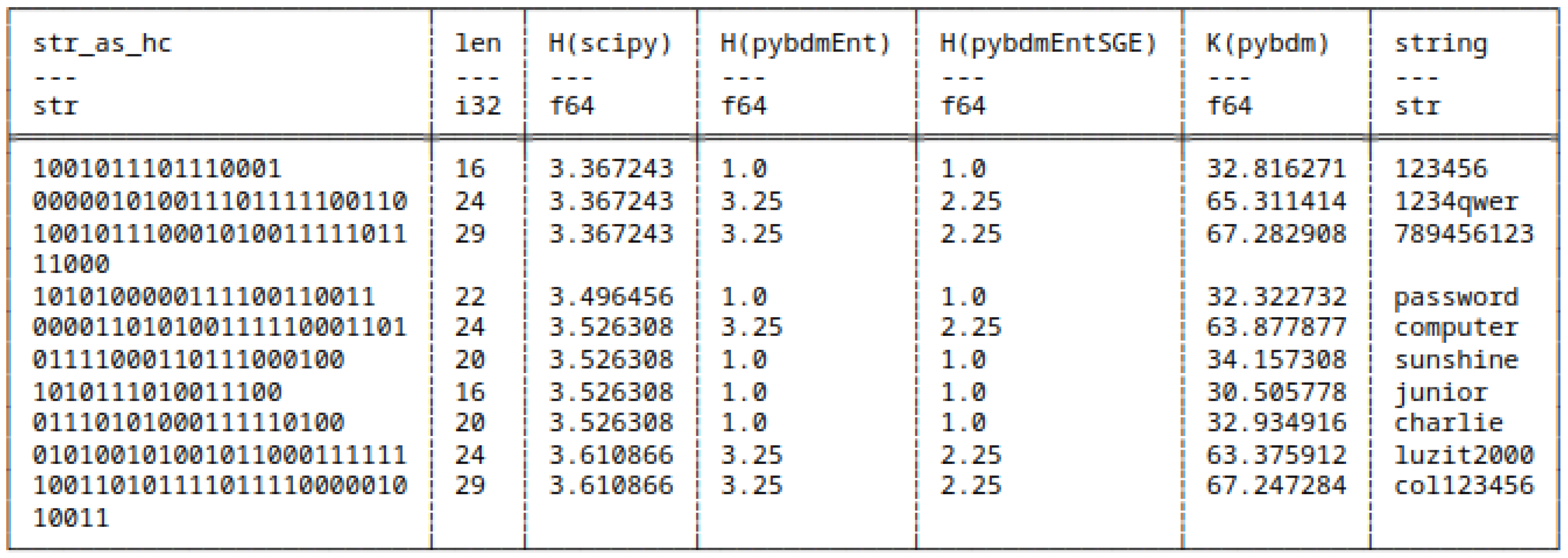

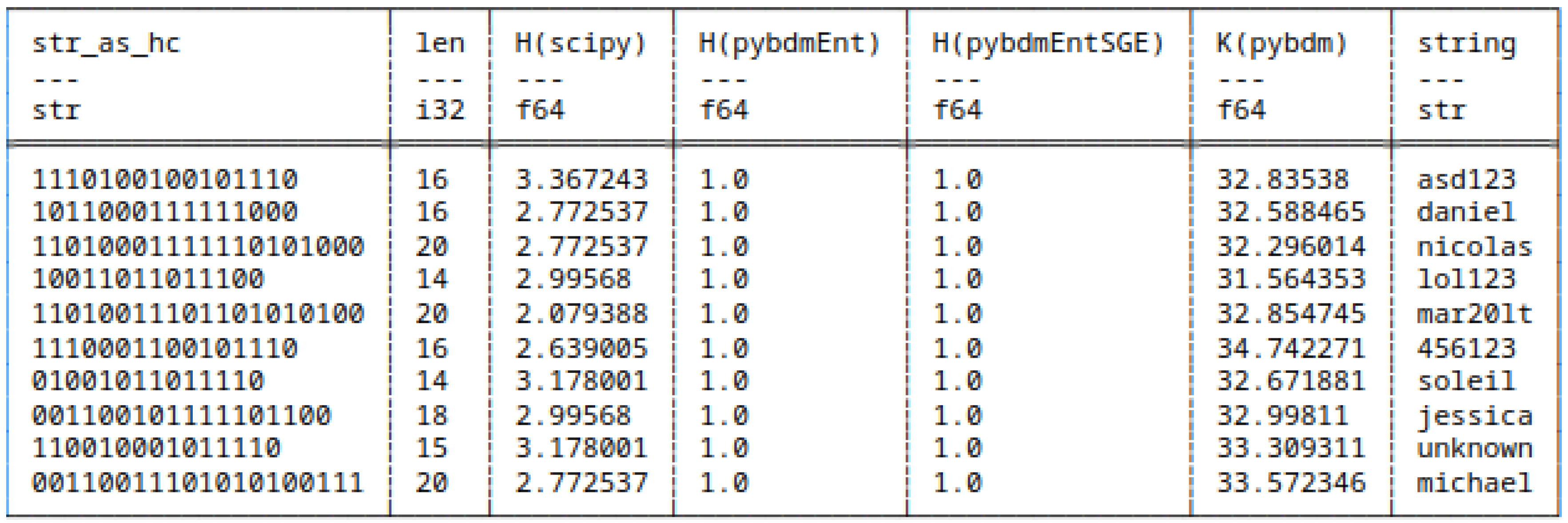

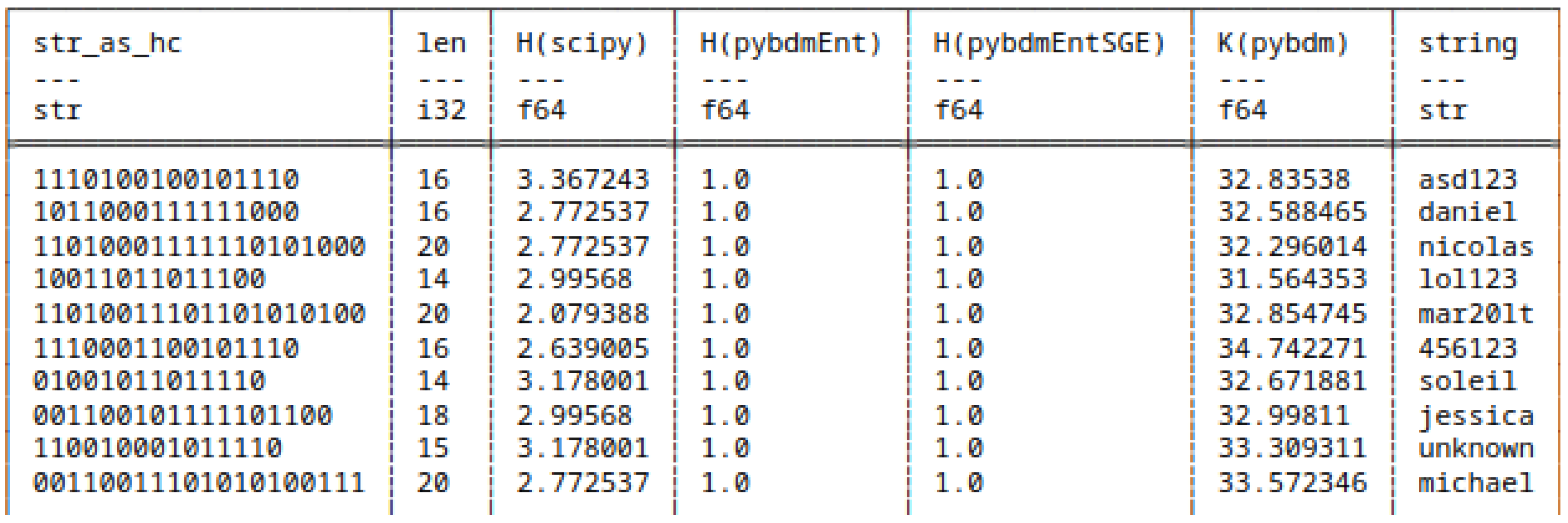

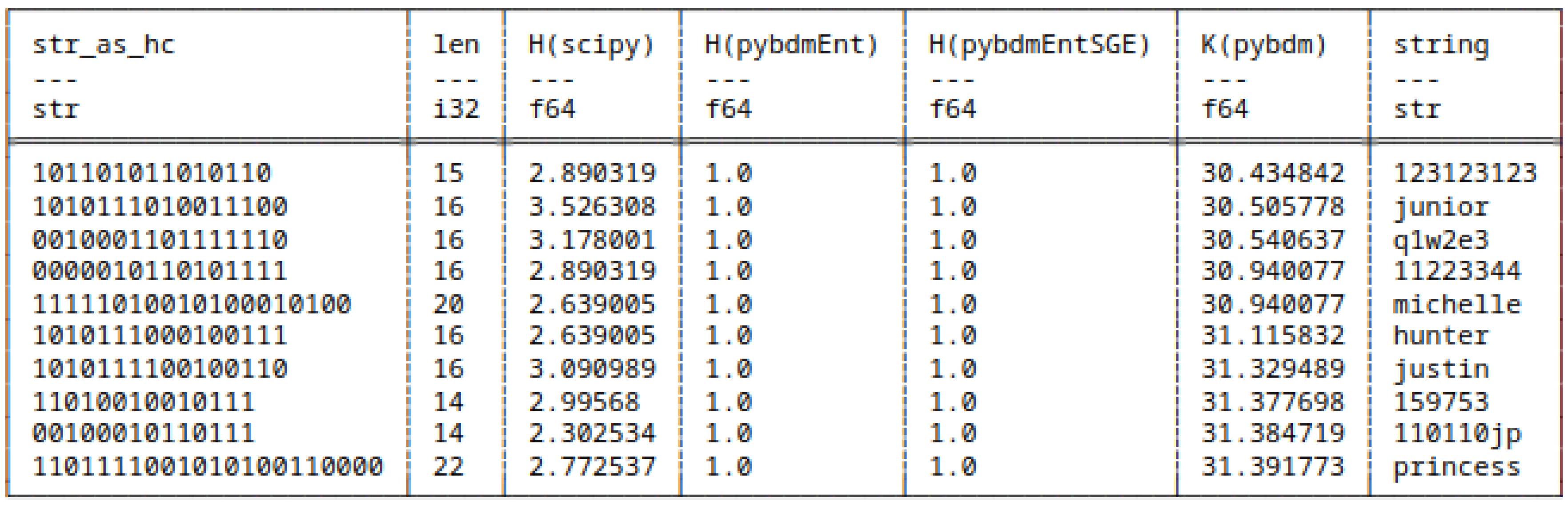

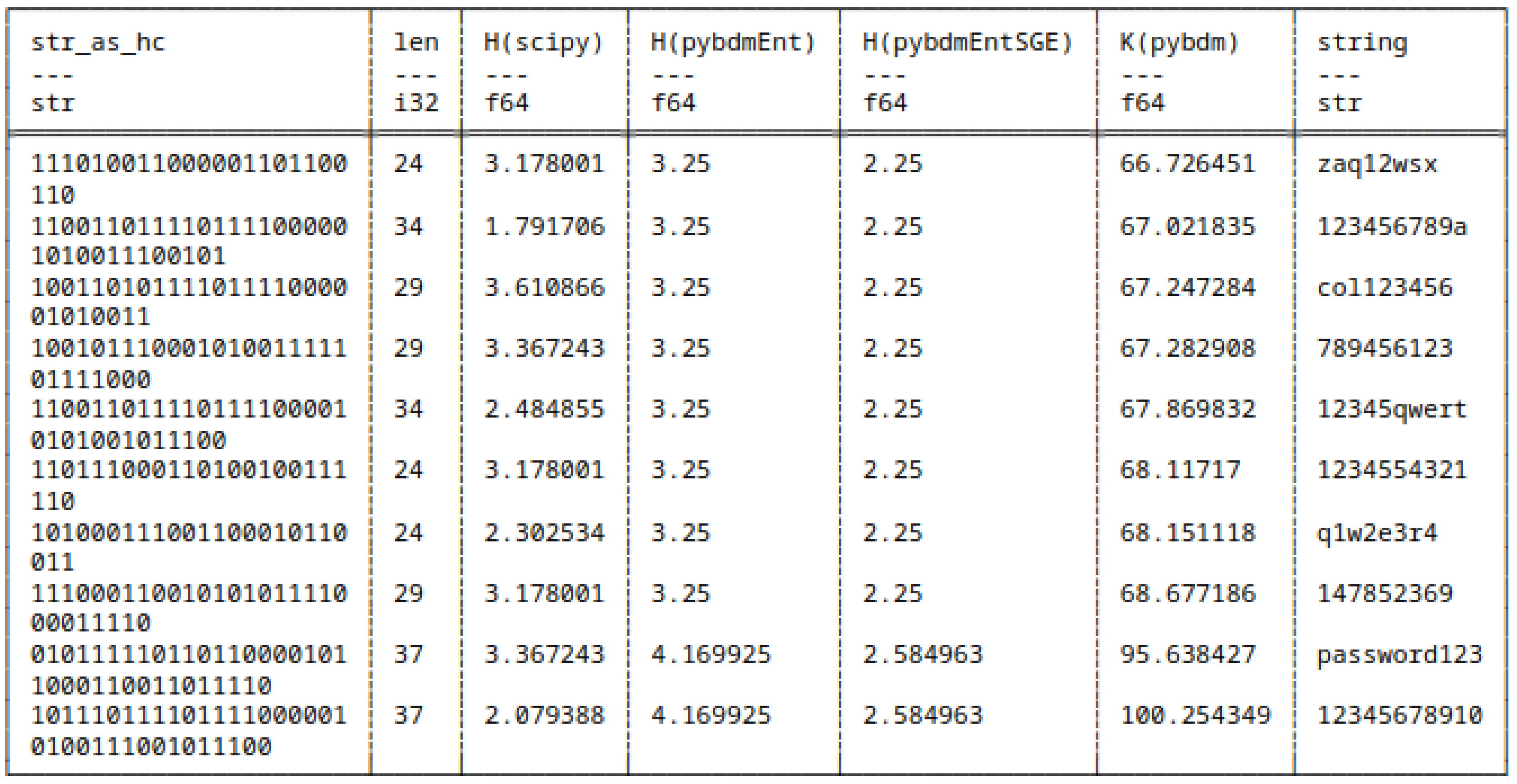

5.7.1. Huffman Encoded Strings

- scipy,

- pybdmEnt - default entropy implementation of pybdm package,

- pybdmEntSGE - our entropy implementation using the Schürmann-Grassberger estimator, see eq. (7),

- Their approximated Algorithmic Complexity (AC) or K using the Block Decomposition Method with pybdm.

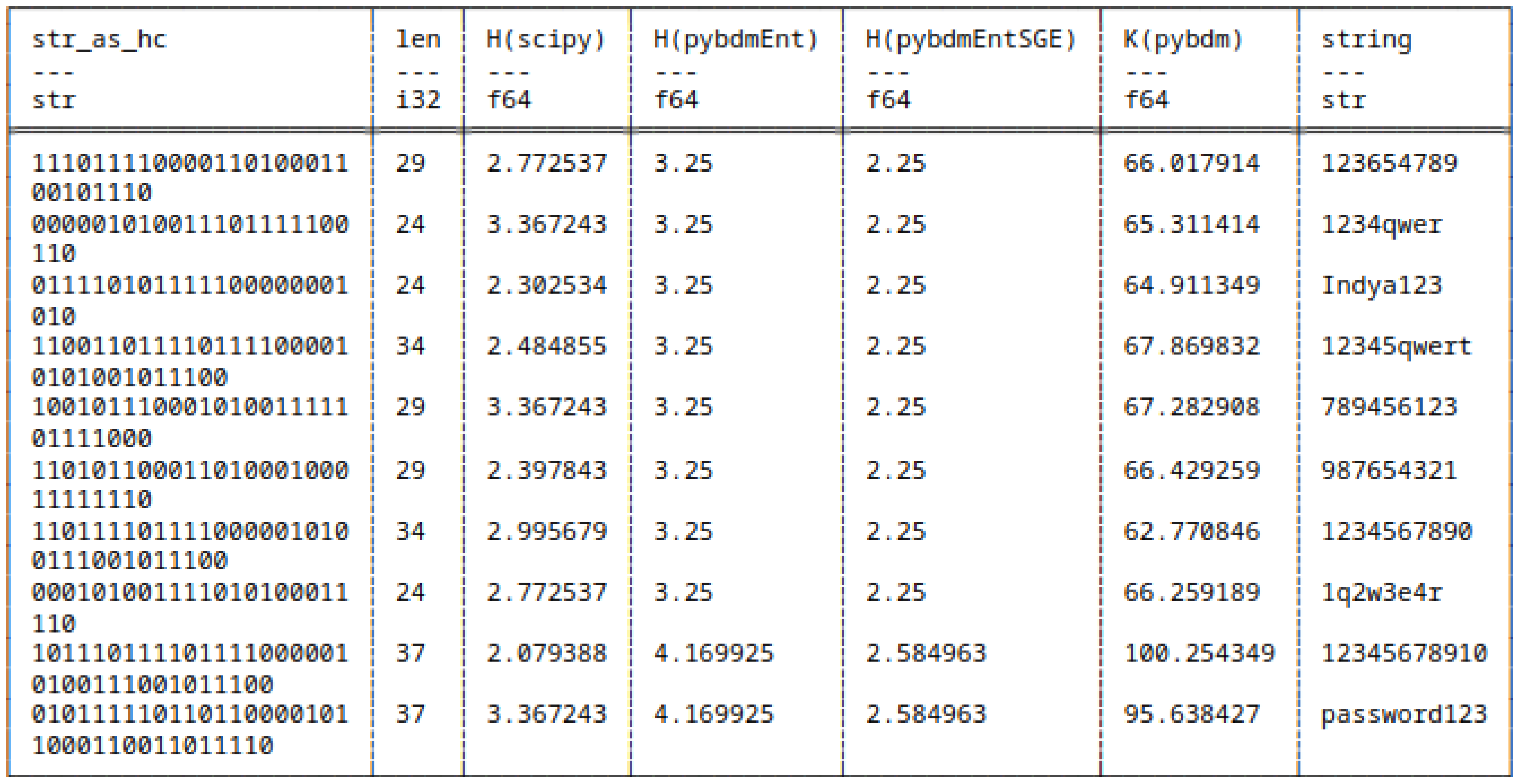

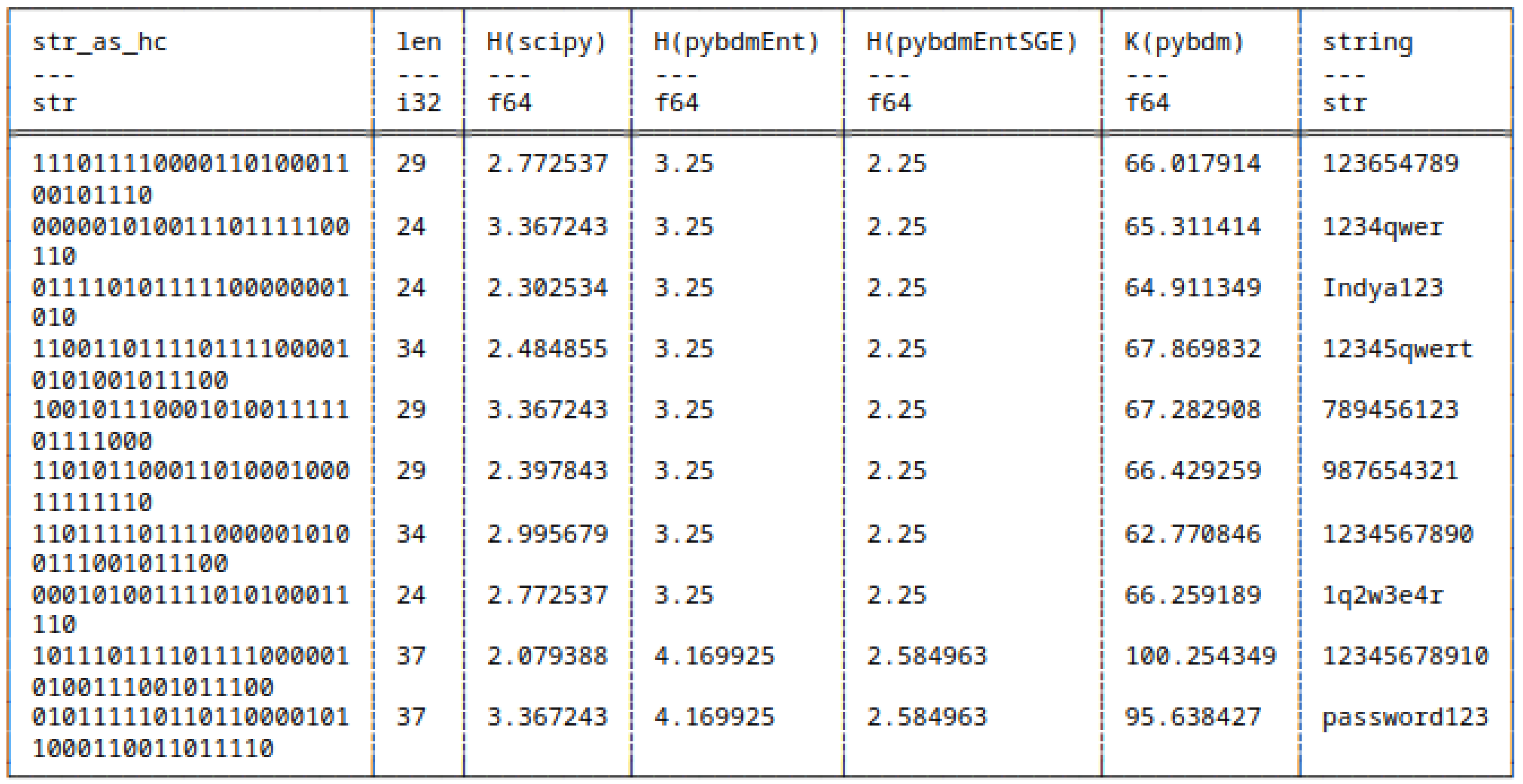

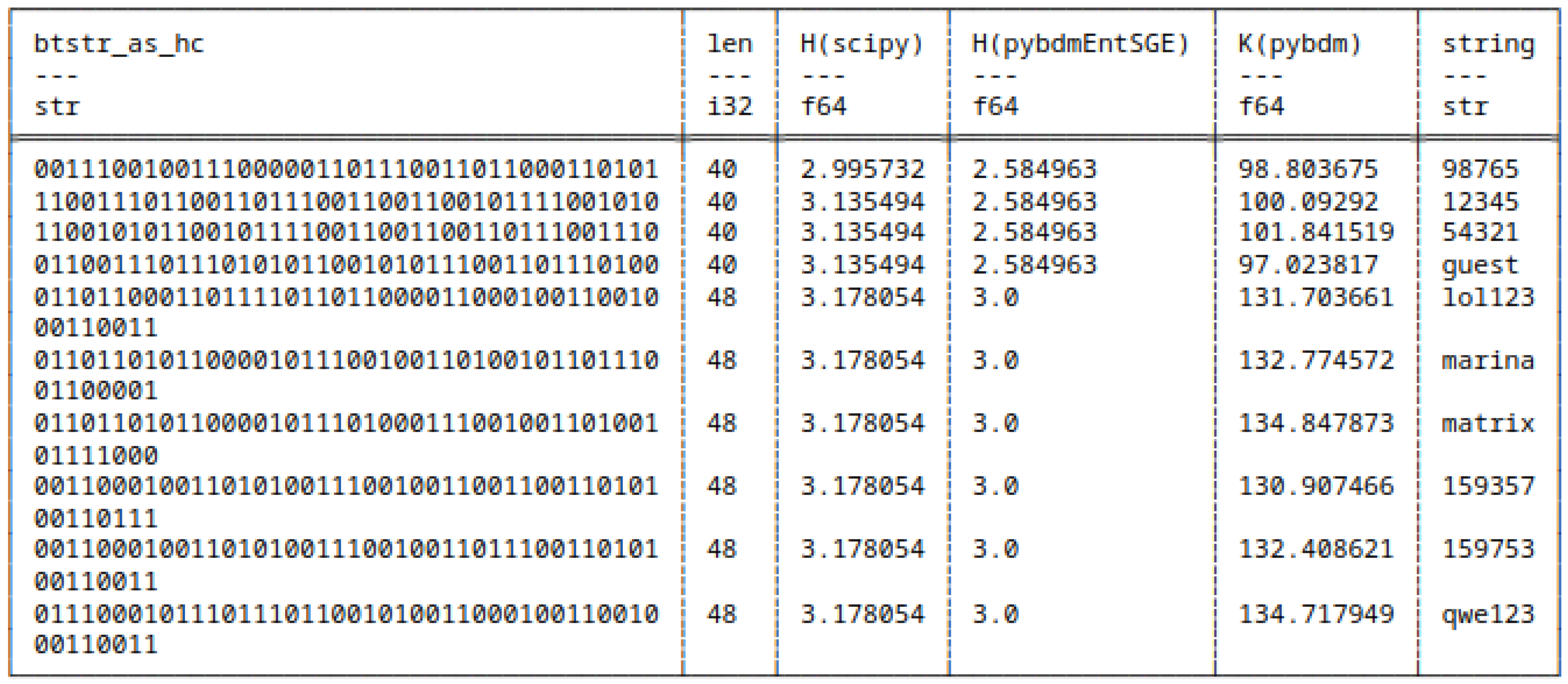

5.7.2. Huffman Encoded Bitstrings

- scipy,

- pybdmEntSGE - our entropy implementation using the Schürmann-Grassberger estimator, see eq. (7),

- Their approximated Algorithmic Complexity (AC) or K using the Block Decomposition Method with pybdm.

5.8. Shannon Entropy and Algorithmic Complexity of Bitstrings

5.8.1. Differences in Computing Shannon Entropy

5.9. Software

5.10. Results

H and H(pybdmEnt)

H and H(pybdmEntSGE)

H(pybdmEnt) and H(pybdmEntSGE)

H(all approaches) and AC(pybdm)

5.10.1. Applicability Shortcomings

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

7.1. Why Care About Algorithmic Information Theory?

7.2. Other Axes of Research

- Source coding or data compression,

- Cryptography,

- Program synthesis

7.2.1. Data Compression and Computation

7.2.2. Cryptography

7.2.3. Program Synthesis

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix H. Software

References

- Talaga, S.; Tsampourakis, K. sztal/pybdm: v0.1.0, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 623–656. [CrossRef]

- Rényi, A. On measures of entropy and information. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Fourth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, Volume 1: Contributions to the Theory of Statistics. University of California Press, 1961, Vol. 4, pp. 547–562.

- Bennett, C.H. Logical Depth and Physical Complexity. In Proceedings of the A Half-Century Survey on The Universal Turing Machine, USA, 1988; p. 227–257.

- Antunes, L.; Fortnow, L.; van Melkebeek, D.; Vinodchandran, N. Computational depth: Concept and applications. Theoretical Computer Science 2006, 354, 391–404. Foundations of Computation Theory (FCT 2003), . [CrossRef]

- Antunes, L.F.C.; Fortnow, L. Sophistication Revisited. Theory Comput. Syst. 2009, 45, 150–161. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Tang, Y.; Jiang, W. A modified belief entropy in Dempster-Shafer framework. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y. Deng entropy. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 2016, 91, 549–553. [CrossRef]

- Chaitin, G.J. How to run algorithmic information theory on a computer: Studying the limits of mathematical reasoning. Complex. 1995, 2, 15–21.

- Kolmogorov, A.N. Logical basis for information theory and probability theory. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1968, 14, 662–664. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, A.; Matos, A.; Souto, A.; Antunes, L.F.C. Entropy Measures vs. Kolmogorov Complexity. Entropy 2011, 13, 595–611. [CrossRef]

- Hammer, D.; Romashchenko, A.E.; Shen, A.; Vereshchagin, N.K. Inequalities for Shannon Entropy and Kolmogorov Complexity. J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 2000, 60, 442–464. [CrossRef]

- Wigner, E.P. The unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics in the natural sciences. Richard courant lecture in mathematical sciences delivered at New York University, May 11, 1959. Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics 1960, 13, 1–14, [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/cpa.3160130102]. [CrossRef]

- Zenil, H. Compression is Comprehension, and the Unreasonable Effectiveness of Digital Computation in the Natural World. CoRR 2019, abs/1904.10258, [1904.10258].

- Li, M.; Vitányi, P. An Introduction to Kolmogorov Complexity and Its Applications, 4th ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2019.

- Zenil, H.; Kiani, N.A.; Tegnér, J. Algorithmic Information Dynamics - A Computational Approach to Causality with Applications to Living Systems; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2023.

- Chaitin, G.J. A Theory of Program Size Formally Identical to Information Theory. J. ACM 1975, 22, 329–340. [CrossRef]

- Calude, C.S. Information and Randomness - An Algorithmic Perspective; Texts in Theoretical Computer Science. An EATCS Series, Springer, 2002. [CrossRef]

- Rissanen, J. Minimum description length. Scholarpedia 2008, 3, 6727. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, C.S.; Dowe, D.L. Minimum Message Length and Kolmogorov Complexity. Comput. J. 1999, 42, 270–283. [CrossRef]

- Ziv, J.; Lempel, A. A Universal Algorithm for Sequential Data Compression. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theor. 2006, 23, 337–343. [CrossRef]

- Ziv, J.; Lempel, A. Compression of Individual Sequences via Variable-Rate Coding. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theor. 2006, 24, 530–536. [CrossRef]

- Levin, L.A. Laws on the conservation (zero increase) of information, and questions on the foundations of probability theory. Problemy Peredaci Informacii 1974, 10, 30–35.

- Peng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, D.; Zhu, J. Selective Run-Length Encoding, 2023, [arXiv:cs.DS/2312.17024].

- Robinson, A.; Cherry, C. Results of a prototype television bandwidth compression scheme. Proceedings of the IEEE 1967, 55, 356–364. [CrossRef]

- Kelbert, M.; Suhov, Y. Information theory and coding by example; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, England, 2014.

- Huffman, D.A. A Method for the Construction of Minimum-Redundancy Codes. Proceedings of the IRE 1952, 40, 1098–1101. [CrossRef]

- Levin, L.A. Randomness Conservation Inequalities; Information and Independence in Mathematical Theories. Inf. Control. 1984, 61, 15–37. [CrossRef]

- Rado, T. On Non-Computable Functions. Bell System Technical Journal 1962, 41, 877–884. [CrossRef]

- Delahaye, J.; Zenil, H. Numerical Evaluation of Algorithmic Complexity for Short Strings: A Glance into the Innermost Structure of Randomness. CoRR 2011, abs/1101.4795, [1101.4795].

- Soler-Toscano, F.; Zenil, H.; Delahaye, J.; Gauvrit, N. Calculating Kolmogorov Complexity from the Output Frequency Distributions of Small Turing Machines. CoRR 2012, abs/1211.1302, [1211.1302].

- Zenil, H.; Toscano, F.S.; Gauvrit, N. Methods and Applications of Algorithmic Complexity - Beyond Statistical Lossless Compression; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022.

- Zenil, H.; Hernández-Orozco, S.; Kiani, N.A.; Soler-Toscano, F.; Rueda-Toicen, A.; Tegnér, J. A Decomposition Method for Global Evaluation of Shannon Entropy and Local Estimations of Algorithmic Complexity. Entropy 2018, 20, 605. [CrossRef]

- Höst, S. Information and Communication Theory (IEEE Series on Digital & Mobile Communication); Wiley-IEEE Press, 2019.

- Cheng, X.; Li, Z. HOW DOES SHANNON’S SOURCE CODING THEOREM FARE IN PREDICTION OF IMAGE COMPRESSION RATIO WITH CURRENT ALGORITHMS? The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 2020, XLIII-B3-2020, 1313–1319. [CrossRef]

- Zenil, H.; Kiani, N.A.; Tegnér, J. Low-algorithmic-complexity entropy-deceiving graphs. Phys. Rev. E 2017, 96, 012308. [CrossRef]

- Wolfram, S. A New Kind of Science; Wolfram Media, 2002.

- Calude, C.S.; Stay, M.A. Most programs stop quickly or never halt. Adv. Appl. Math. 2008, 40, 295–308. [CrossRef]

- Müller, M. Stationary algorithmic probability. Theoretical Computer Science 2010, 411, 113–130. [CrossRef]

- Calude, C.S. Simplicity via provability for universal prefix-free Turing machines. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2011, 412, 178–182. [CrossRef]

- Savage, J.E. Models of computation; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, 1997.

- Rojas, R. Conditional Branching is not Necessary for Universal Computation in von Neumann Computers. J. Univers. Comput. Sci. 1996, 2, 756–768. [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. Universality of Wolfram’s 2, 3 Turing Machine. Complex Syst. 2020, 29. [CrossRef]

- Ehret, K. An information-theoretic approach to language complexity: variation in naturalistic corpora. PhD thesis, Dissertation, Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg, 2016, 2016.

- Bentz, C.; Gutierrez-Vasques, X.; Sozinova, O.; Samardžić, T. Complexity trade-offs and equi-complexity in natural languages: a meta-analysis. Linguistics Vanguard 2023, 9, 9–25. [CrossRef]

- Koplenig, A.; Meyer, P.; Wolfer, S.; Müller-Spitzer, C. The statistical trade-off between word order and word structure – Large-scale evidence for the principle of least effort. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Barmpalias, G.; Lewis-Pye, A. Compression of Data Streams Down to Their Information Content. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2019, 65, 4471–4485. [CrossRef]

- Kolmogorov, A.N. Three approaches to the quantitative definition of information *. International Journal of Computer Mathematics 1968, 2, 157–168, https://doi.org/10.1080/00207166808803030. [CrossRef]

- V’yugin, V.V. Algorithmic Complexity and Stochastic Properties of Finite Binary Sequences. Comput. J. 1999, 42, 294–317. [CrossRef]

- NordPass. Top 200 Most Common Passwords List — nordpass.com. https://nordpass.com/most-common-passwords-list/, 2022. [Accessed 2024-01-06].

- Archer, E.; Park, I.M.; Pillow, J.W. Bayesian Entropy Estimation for Countable Discrete Distributions. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2014, 15, 2833–2868.

- Schürmann, T. Bias analysis in entropy estimation. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and General 2004, 37, L295–L301. [CrossRef]

- Grassberger, P. Entropy Estimates from Insufficient Samplings, 2008, [arXiv:physics.data-an/physics/0307138].

- Schürmann, T. A Note on Entropy Estimation. Neural Computation 2015, 27, 2097–2106, [https://direct.mit.edu/neco/article-pdf/27/10/2097/952159/neco_a_00775.pdf]. [CrossRef]

- Grassberger, P. On Generalized Schürmann Entropy Estimators. Entropy 2022, 24. [CrossRef]

- Salomon, D.; Motta, G. Handbook of data compression; Springer Science & Business Media, 2010.

- Ilie, L. Combinatorial Complexity Measures for Strings. In Recent Advances in Formal Languages and Applications; Ésik, Z.; Martín-Vide, C.; Mitrana, V., Eds.; Springer, 2006; Vol. 25, Studies in Computational Intelligence, pp. 149–170. [CrossRef]

- Ilie, L.; Yu, S.; Zhang, K. Word Complexity And Repetitions In Words. Int. J. Found. Comput. Sci. 2004, 15, 41–55. [CrossRef]

- Zenil, H. A Computable Universe; WORLD SCIENTIFIC, 2012; [https://www.worldscientific.com/doi/pdf/10.1142/8306]. [CrossRef]

- Grünwald, P.; Vitányi, P.M.B. Kolmogorov Complexity and Information Theory. With an Interpretation in Terms of Questions and Answers. J. Log. Lang. Inf. 2003, 12, 497–529. [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, C. Crypto wars; CRC Press: London, England, 2020.

- Hitchcock, J.M.; Pavan, A.; Vinodchandran, N.V. Kolmogorov Complexity in Randomness Extraction. ACM Trans. Comput. Theory 2011, 3, 1:1–1:12. [CrossRef]

- Mazlish, B. The Fourth Discontinuity. Technology and Culture 1967, 8, 1–15.

- Dean, J. The Deep Learning Revolution and Its Implications for Computer Architecture and Chip Design. CoRR 2019, abs/1911.05289, [1911.05289].

- Hornik, K.; Stinchcombe, M.; White, H. Multilayer feedforward networks are universal approximators. Neural Networks 1989, 2, 359–366. [CrossRef]

- Kratsios, A. The Universal Approximation Property. Ann. Math. Artif. Intell. 2021, 89, 435–469. [CrossRef]

- Van Rossum, G.; Drake, F.L. Python 3 Reference Manual; CreateSpace: Scotts Valley, CA, 2009.

- Vink, R.; de Gooijer, S.; Beedie, A.; Gorelli, M.E.; van Zundert, J.; Guo, W.; Hulselmans, G.; universalmind303.; Peters, O.; Marshall.; et al. pola-rs/polars: Python Polars 0.20.5, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nature Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [CrossRef]

- The Sage Developers. SageMath, the Sage Mathematics Software System (Version 9.5.0), 2022. https://www.sagemath.org.

- Wei, T.N. python-rle, 2020.

| 1 | Also known under the name of Solomonoff-Kolmogorov-Chaitin complexity |

| 2 | In this work, we consider the notion of computational as effectively computable or, equivalently computable in a mechanistic sense. |

| 3 | In general, a probability measure is a value within the [0, 1] interval, here it’s called a semi-measure because not every program will halt thus the sum will never be 1. |

| 4 | |

| 5 | Block of information bits encoded into a codeword by an encoder |

| 6 | We will argue its adequation for every context. |

| 7 | in the Shannon sense |

| 8 | In the context of real world computation, this assumption needs to be made. This is in contrast with the theoretical model of a Turing machine which does not made any. |

| 9 | As technically is the Church-Turing Thesis |

| 10 | This probably applies even more to passphrases. |

| 11 | A function f is right-c.e. if it is computably approximable from above, i.e. it has a computable approximation such that for all . |

| 12 | |

| 13 | The reason for this duplicates is unclear, it has been reported. |

| 14 | Also known as the plugin estimator |

| 15 | That is, composed of a combination of characters and numbers |

| 16 | Obviously, there is also the decompression side. |

| 17 | With the help of some heuristics. |

| 18 | Assuming that all Science problems can be seen/recasted as prediction problems then the theoretical power of Algorithmic Information Theory makes it virtually agnostic to any specific field. |

| 19 | Integrated Development Environment |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).