1. A Philosophical Introduction

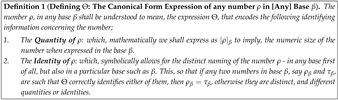

Assume we begin with the following definition:

By Definition 1, assuming we go by popular conventions in use for ordinary human language and semantics, then, when one entity declares to another that “I have counted 1000000", it could be interpreted as meaning or implying one of the following:

`1000000’ is a quantity.

`1000000’ also expresses the name of that quantity — its unique or distinct identifier in some base — typically, base-10 — and thus just “1 Million", unless explicitly specified; such as if it had been expressed as or or perhaps — notations more commonly found in computational literature, and then in Latin Numeral Notation.

`1000000’ implies it is possibly just the quantity, and nothing about whether or not the number has some non-quantifiable quality — such as whether it is signed or not.

The above information might be sufficient for the purposes of merely operating on the name and quantity of the number in the usual or commonplace sense, but perhaps not in a totally meaningful or rather, non-ambiguous way. What this means exactly, can be appreciated by further considering that:

Without knowing explicitly in which base the counting operation was conducted — or rather, how the computation was performed, we can only guess at what really the quantity of the expression `1000000’ is. This, especially if we wish to somewhat reproduce or rather compare other quantities in some or any base, relative to that expressed quantity. So basically, without the base information, the expression `1000000’ is but a scalar symbol — it tells us about some number and offers an idea about its quantity or size, but actually only its name and little or nothing about how to exactly express its quantity meaningfully.

-

As a result of the above condition, we might for example wrongfully mis-read the expression `1000000’ to mean any of the following:

Further, we might not clearly know whether the number is positive or not, or whether it expresses a pure number or a pure fractional number — since, for

pure fractionals [

1], we might, under some special notations, do away with the implied usual “symbolic" parts of the number’s expression such as when we write “0.5" to mean

when we could as well have written just “.5" or even perhaps

!

So, much as sometimes number expressions are used/meant to communicate more precise, or rather, unambiguous forms of quantities and quantifiably identifiable measures or properties of things, then, it is important that we be more careful and adopt more explicit, or rather rigorously unambiguous expressions of numbers when communicating exact science, mathematics and/or verifiable information.

A more precise way to report the result of a computation such as counting, should have been expressed as: “I have counted 1000000 in base 2."

2. The Lu-Number System

In this section, we are going to build upon ideas from the previous section, to try and develop from scratch, a theory and mechanics for defining abtract machines that can process information as input and then produce or rather, generate other information — in particular, information expressions such as numbers in some number system. These machines are essentially Number Generators, though, ultimately, our objective is to systematize and formalize and advance the important field of Random Number Generators.

We shall refer to the original reference number system we are going to base our number generation theory on, as the Lu-Number System, LNS.

2.1. LNS Foundations and Generating Lu-Numbers

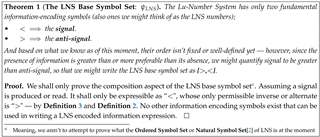

Let there be a distinct symbol to be referred to as the signal. For practical purposes, let the signal be the symbol “<".

Axiom 1. Every distinct information has a definite distinct way it can be expressed or encoded so as to express, manifest or represent that for which it is a reference—typically via some symbol or systematic sequence of them, which is known as “information encoding". Equivalently, symbols represent or express some definite information — information that can be understood and is communicable.

Definition 2 (The First Base Symbol:the Signal) This is essentially the Primal Signal Encoding Method in the Lu-Number System (LNS); the primal-symbol, also to be known as “the signal", to be simply written as “<" — a single opening angle-bracket. In the LNS, it is meant to basically express the presence of some information — any perceptible information.

Axiom 2. In being expressed, any distinct information under the LNS can take on one of two forms; the primal-form or the alternate/inverted form, but not both simultaneously.

Definition 3 (Alternate Base-Symbol:the Alternate Signal — the Anti-Signal) In LNS, because it is the alternate or opposite of signal, “>", it shall simply be expressed as “>" — the lateral inversion or exact mirror reflection of the primal-symbol. Also, this operation of reflection or inversion of symbols or information in general, is among the first permissible operations in LNS. More about this later.

Note that, to simplify our calculus when dealing with the LNS Base Symbol Set, sometimes we might just write instead of .

Definition 4 (An Information Expression). An information expression, Θ, is any systematic encoding of meaning as a finite sequence of distinct symbols from a definite symbol set such as (refer toTheorem 1).

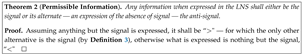

It shall be interesting to note that

Postulate 1 raises some interesting problems. For example, away from the simplest LNS expressions such as “<" and “>", shall it be correct to define

, the

LNS inversion operation as:

Also, in the case of the LNS reduction operation, , when or how should we decide which of two or more possible permissible results to produce, generate or return from a call with multi-symbol input information expression — such as or ? Essentially, what should be returned in the following computation:

Computation 1. ?

This problem is actually very important in this LNS theory — it is the kind of problem that brings to mind issues like how to define autonomous choice or autonomous decision making or an autonomous random reduction of some input information? It might likewise spur other problems like; what is the true nature of entropy? What is the identification of signal fundamentally based on? Also, such a critical problem as; is it the operator that decides or what is operated on, concerning what such a dynamic operation as ought return?

2.1.1. Concerning Information Production/Generation with LNS:

Before we proceed, it shall help to clarify on some important matters concerning some of the LNS operations we have just formalized in Postulate 1.

First of all, for purposes of not prematurely jumping into or deviating away from our core subject in this present inquiry or formulation, we must appreciate that it is not really the responsibility of a Number Production System or Information Expression/Encoding System theory to worry about the first production of information — creation

ex-nihilo for example, or how entropy comes to be in the first place in any system, but rather, to provide means to systematically express any such originally produced information (via natural entropy for example), when it becomes manifest — such as to a

basic signal perceptron or an IoT sensor. Realistically, there might still be some unanswerable questions within the theoretical, though practically useful LNS for now, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it is incomplete

1.

For example, concerning the interesting

information reduction operation,

in LNS (see

Postulate 1), we could simplify the operation semantics thus:

This queer definition of the reduction operation is to allow us to explain how it is possible that where there was more than one possible and/or permissible output from the operation based on the input, we still can express meaningful limits on what the result or

correct output ought look like and/or mean;

the output is always a subset of the input expression2.

And then, concerning the strange

information production operation,

in LNS — which, because it essentially is the first way that information ever gets expressed in any LNS production system — where none existed that is — from or via the processing of raw input signal — that might not necessarily be originally expressed using LNS encoding — such as when such information is produced by a natural system, e.g. the thermodynamic and/or kinematic properties of a naked flame/fire, the Brownian motion of gas particles, the kinematics and geometries of a cloud, the hydrodynamics of a fluid under turbulence, certain statistics in a financial market etc., and yet, its output should be information meaningful within the LNS encoding. Thus, we should perhaps generally define

as such:

borrowing notation from the

Backus-Naur form[

5] notation or

borrowing from

CNF grammar/syntax production rules notation[

6] common in the expression of

branching or

stochastic production processes in software language engineering literature. Generally, for any number generation founded on the LNS:

for

a valid LNS information expression.

And, before we close discussion concerning

pr(.), note that, the choice of notation when expressing such a function is quite important. For example, from a higher abstraction level — say at the level of a user of an RNG function such as the TEA programming language primitive

n: that is built into the language so as to help generate random numbers[

7] — it might be the case that from the user’s reference frame or rather, point of view, the basic RNG

is usable even without any explicit user input — such as for the TEA primitive we have just talked about — meaning, it seems as though the [correct] signature of the

information production operator ought be written as:

So that, it justifies the idea of creating new information from nothing (thus “ex-nihilo") or rather, specifying an RNG that uses/requires no seeds! However, despite the aesthetic gravity of this later signature, it is wiser to stick to the earlier variant (

Equation 5), or perhaps, we could instead write

to imply both points of view, though,

still remains preferable because, apart from helping abstract away what exactly the nature of the arguments the generator expects or operates on, at least it makes it clear there is always some argument no matter what. And in fact, at the lowest level, such as when dealing with a TRNG that say sources entropy from a physical source[

8], we find that despite the user of the function not having to explicitly specify an invocation-time argument when seeking for a new [possibly random] information expression, and yet, behind the scenes, at minimum, such an operation must explicitly specify when and from which source (or even perhaps how) the desired information must be read or extracted from the entropy source. Thus, to balance between abstraction, elegance and correct semantics, (

Equation 5) shall be our most authoritative definition of the generator operation.

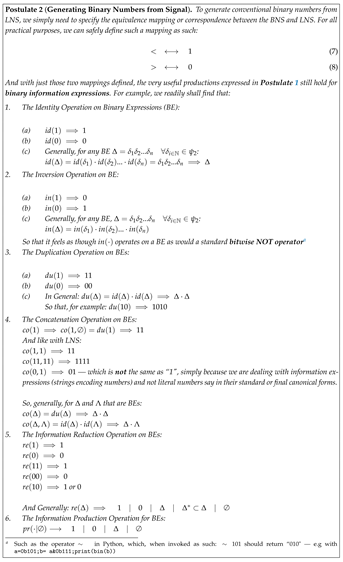

3. Generating Binary Numbers from Signal

Now that we have seen how to generate and/or produce simple and complex information expressions such as numbers in the Lu-Number System, we shall next turn our attention to the production of information expressions in a form more palatable and relatable for practical applications in most real-life domains. Essentially, we are to first look at the simplest number system useful in typical computation processes — the base-2 number system, also known as the “binary number system", BNS.

Lemma 1 (

Equivalence of and ).

By Postulate 2 and the fact that the Base-2 natural symbol set[2] is merely , if we write the LNS base symbol set (seeTheorem 1) in its ordered form as , then .

The interesting and useful consequences of Lemma 1 is that any typical binary number expressions (or rather, information expressions encoded using bits) can all be re-written simply as expressions in the Lu-Number System. Or rather, at the symbol-set level then, the two seemingly different information encoding number systems are equivalent and expressions in one system can readily be re-written in the other. Illustrations of this would be transforms such as:

4. Generating Decimals from Signal

Now that we have seen the case of obtaining binary numbers from signal, or rather, via the Lu-Number System, and having seen the interesting property that the BNS and LNS are equivalent in some regards, we can then turn our attention to information expressions of numbers in base-10 and see what interesting things we might find out based on LNS.

Next, we shall look at the generation of numbers in any base.

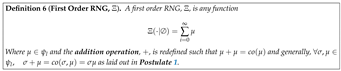

5. A General Number Generator and the True Random Number Generator

Building on the ideas we have seen in the previous sections, we can safely trust that the LNS can readily allow us to design a number generator targeting any base starting from the processing of some basic signal.

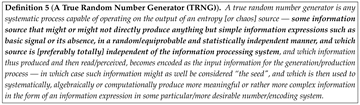

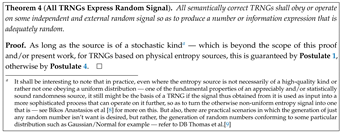

Turning our attention away from the generation of just any information expression, or rather, any numeric expressions or numbers, we shall now look at the more important matter of how to generate random information expressions and consequently, how to generate truly random numbers.

At this juncture, we can pause and appreciate that any random number generator is in one way or another, an information processor — more correctly, a signal encoder. However, for TRNGs, the conditions laid out in

Definition 5 are undeniably critical and important, since, they shall help us to readily tell apart RNGs that are truly/appreciably random from those that are only-approximately random (such as

pseudo-random number generators, PRNGs), that might forego use of an external, statistically independent and semantically correct source of randomness, and instead rely on user-provided seeds, say for purposes of allowing the generation of predictable random numbers or sequences of them, and thus, produce or generate predictable information/results — see [

8] for more on this). This shall also help in the design and implementation of special RNGs meant for critical operations such as in enabling cryptography or information security via the use of Cryptographically Secure Random Number Generators (CSRNGs).

Next, we shall attempt to distinguish between RNGs that operate directly on raw signal (physical information) vs those that operate on complex signal — or rather, on finite strings such as [higher-order] information expressions (see Definition 4).

We shall then find that the production operator in LNS, is actually a kind of .

Lemma 2 (All -TRNG Reducible to -TRNG). Any higher-order TRNG producing numbers in any base or number system can be reduced to a simple first-order TRNG in the LNS.

6. Conclusion

In this work, we have developed a new number system, LNS, a basic, first-order information encoding system fit for expressing basic outputs from an entropy source — especially physical entropy sources, in the form of signal or its absence. LNS provides a low-level framework upon which interaction with entropy sources can be made so that higher-level information expressions such as numbers in binary, decimal and other usual bases can be readily obtained or inferred from mere basic signal. We have seen how the basic LNS number generator would work from a purely theoretical perspective, and have likewise seen how other higher order number generators — in particular, Binary Number Generators and then Decimal Number Generators can be founded on an LNS generator. Apart from offering the foundations for rigorously specifying a basic RNG, via specifying the permissible basic operations possible on LNS-encoded basic information, this work also contributes to the literature on especially TRNGs, by establishing how any TRNG irrespective of its target or output number system, can be founded on, or rather, can be reduced to a basic LNS-TRNG — a . In future work, we shall further this undertaking with pragmatic verification of the theory thus laid out, say with a reference implementation of a LNS-TRNG, and leveraging that to implement a high-order RNG, , such as a decimal TRNG, so as to practically verify this theory and also help extend it further. Also, more theoretical work might delve into answering some of the still-unanswered questions raised in this present work, such as how exactly to specify when/how a typical branching production rule in a generator specification might rely on some explicit condition so as to decide how to produce one of several possible output [terminal or non-terminal] terms, a solution that might likewise be of theoretical and practical relevance in automated language engineering such as in implementing systems than can generate valid source-code/computer programs autonomously or even stochastically, based on processing of a language specification or formal grammar (BNF or CNF production rules for example), and which are driven by some stochastic signal or input — ideas useful in cases such as if we are to work on automated-generation of valid and useful TEA programs ex-nihilo.

References

- Joseph Willrich Lutalo. A general theory of number cardinality. Academia.edu, Jan 2024. Accessible via https://www.academia.edu/43197243/A_General_Theory_of_Number_Cardinality.

- Joseph Willrich Lutalo. Concerning a special summation that preserves the base-10 orthogonal symbol set identity in both addends and the sum. 2025. Accessible via https://www.academia.edu/download/122499576/The_Symbol_Set_Identity_paper_Joseph_Willrich_Lutalo_25APR2025.pdf.

- Joseph Willrich Lutalo. Numbers from arbitrary text: Mapping human readable text to numbers in base-36. Academia.edu, 2024. Accessible via https://www.academia.edu/123296302/Numbers_from_Arbitrary_Text_Mapping_Human_Readable_Text_to_Numbers_in_Base_36.

- Michael J. Bossé and William J. Cook. Repeating decimal expansions in different bases. Electronic Journal of Mathematics & Technology, 2025. Accessible via https://ejmt.mathandtech.org/Contents/eJMT_v16n3p4.pdf.

- Donald E. Knuth. Backus normal form vs. backus-naur form. Communications of the ACM, 7(12):735–736, 1964. Accessible via https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/355588.365140.

- V Aho Alfred, S Lam Monica, and D Ullman Jeffrey. Compilers principles, techniques & tools. pearson Education, 2007. Accessible via https://elib.vku.udn.vn/bitstream/123456789/2542/1/2007.%20Compilers-Principles%2C%20Techniques%2C%20and%20Tools%20%282nd%20Edition%29.pdf.

- Joseph Willrich Lutalo. TEA TAZ - Transforming Executable Alphabet A: to Z: COMMAND SPACE SPECIFICATION, 2024. Accessed on 14 May, 2025, via https://www.academia.edu/122871672/TEA_TAZ_Transforming_Executable_Alphabet_A_to_Z_COMMAND_SPACE_SPECIFICATION.

- Anastasios Bikos, Panagiotis E Nastou, Georgios Petroudis, and Yannis C Stamatiou. Random number generators: Principles and applications. Cryptography, 7(4):54, 2023. Accessible via https://www.mdpi.com/2410-387X/7/4/54.

- David B Thomas, Wayne Luk, Philip HW Leong, and John D Villasenor. Gaussian random number generators. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR), 39(4):11–es, 2007. Accessible via http://cas.ee.ic.ac.uk/people/dt10/research/thomas-07-gaussian-survey.pdf.

| 1 |

The appeal to Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem might seem accidental, however, as we are still just developing this theory for the first time, is perhaps great to keep in mind just in case. |

| 2 |

The empty set, ∅, is likewise implied/expressed, not only because it logically is a valid subset of any input expression, but that, practically or rather, semantically, there might be scenarios in which the function or processing fails to return or halt, and thus no meaningful information can be returned except nothing. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).