Introduction

In cancer cells, aerobic glycolysis, the Warburg effect, is characterized by elevated glycolytic flux and increased lactate production, even in the presence of sufficient oxygen. The biological and clinical significance of aerobic glycolysis has attracted widespread attention: a Google Scholar search for “glycolysis and cancer” yields over 436,000 results. Interest in flux control of glycolysis in cancer is also substantial, with approximately 114,000 results for the terms “flux control, glycolysis, cancer.”

Cancer cells adapt glycolytic flux according to nutrient availability. Under nutrient-rich conditions, glycolysis supports rapid growth by diverting intermediates into anabolic pathways. In nutrient-limited environments, glycolysis shifts toward energy production to maintain cell survival. Thus, glycolysis is dynamically regulated to meet varying cellular demands [

1,

2,

3].

Previous studies have primarily focused on kinetic regulation of glycolysis—examining mechanisms such as allosteric modulation, transcriptional control, feedback inhibition, and feedforward activation. These investigations have emphasized how changes in enzyme activity influence glycolytic flux. In contrast, thermodynamic considerations have typically been limited to the role of Gibbs free energy in governing reaction directionality and energy transfer within the pathway.

What remains largely unexplored is how enzyme kinetics and thermodynamics interact within the glycolytic pathway. Specifically, the coordination between glycolytic flux, the rate of each step, intermediate concentrations, and the ΔG values of individual reactions has received little attention. Another critical issue is that, although glycolysis is widely recognized as a dynamic and adaptable pathway, particularly in cancer metabolism, its capacity to maintain a stable steady state under fluctuating conditions is often overlooked.

This stability is not passive but actively maintained through kinetic-thermodynamic coupling, which allows the pathway to redistribute metabolite concentrations and Gibbs free energy (ΔG) in response to perturbations. As a result, steady-state flux is preserved even when enzyme activity changes, revealing glycolysis as a self-stabilizing system rather than merely a responsive one.

This work builds upon our previous experimental studies on the kinetic and thermodynamic properties of the glycolytic pathway [

4,

5,

6,

7], providing a theoretical framework that reveals the underlying principles coordinating flux, intermediate concentrations, and thermodynamic driving forces.

Results

Kinetic-Thermodynamic Coupling in the Glycolytic Pathway

To examine the interdependence between enzyme kinetics and thermodynamics in glycolysis, it is essential to focus on the core glycolytic pathway and exclude branching reactions (e.g., pentose phosphate pathway, serine biosynthesis pathway). This simplification enables a clearer analysis of the fundamental principles governing flux and intermediate metabolite distribution.

Glycolysis can be analyzed under two conditions:

The steady state, in which intermediate metabolite levels and reaction rates remain constant over time; and

The interstate, a transient phase during transitions between steady states.

Steady-State Glycolysis:A Question of Equal Flux

At steady state, the flux through every enzyme-catalyzed reaction in glycolysis is equal and constant. This raises a fundamental question: How can reaction rates remain equal when the total activity of 11 glycolytic enzymes differ by up to three orders of magnitude [

4,

5,

6,

7]?

In glycolysis, the actual catalytic activity of each enzyme depends on two factors:

Thus, for every step in the pathway to operate at the same rate, the concentrations of intermediates must be precisely tuned to compensate for differences in enzyme abundance or activity. Furthermore, these intermediate concentrations must remain stable over time to maintain this kinetic balance.

Thermodynamic Determinants of Intermediate Distribution

This leads to a second key question: how are these intermediate concentrations finely tuned across the pathway? This question concerns the distribution of intermediate metabolite concentrations, which is governed by the thermodynamic properties of the pathway.

Consider a linear metabolic pathway consisting of n sequential reactions at steady state, where each reaction k is coupled to the next via shared metabolites: the product of one step becomes the substrate for the next. Let the metabolites be labeled as X0, X1, X2, ….., Xn, where:

X0 is the initial substrate,

Xn is the final product

Xk (for k =1,2,3,…,n−1) is both the product of reaction k and the substrate of reaction k+1.

The Gibbs free energy (ΔG

k) for each reaction

k is given by:

|

, k =1,2,3…..n, (Eq. 1)

|

Because the product of one reaction is the substrate of the next, coupling imposes the following relationships:

Reaction k produces Xk:

Reaction k + 1 consumes Xk: ,

The above equations could be rearranged to

|

⇒ (Eq. 2)

|

|

⇒ (Eq. 3)

|

Substituting Eq. 2 into Eq. 3 yields:

|

(Eq. 4)

|

Extending this sequentially across the entire pathway yields:

|

(Eq. 5)

|

The above equations show that in a linear metabolic pathway at steady state, the concentrations of intermediates are interdependent and must satisfy the thermodynamic constraints imposed by each reaction’s ΔG. This sequential coupling ensures that the entire pathway operates in a coordinated manner, balancing energy changes and metabolite levels.

By analogy, all the reactions and ΔG values within the glycolytic pathway are sequentially coupled to one another, and the concentrations of all the intermediates in the pathway are thermodynamically equilibrated.

From this perspective, the distribution of intermediate concentrations arises from thermodynamic equilibration. The need to maintain equal flux through each enzymatic step is satisfied by adjusting intermediate concentrations, which in turn are constrained by the overall thermodynamic landscape.

Thus, actual enzyme activity becomes a function of both:

This defines the principle of kinetic-thermodynamic coupling: the rates, concentrations of intermediates, and ΔG values are interdependent and co-regulated to ensure flux stability.

Pathway-Level Conservation of Thermodynamic Features

Importantly, because the thermodynamic properties of glycolysis govern intermediate distributions, this profile is conserved across cell types [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Among the 11 glycolytic reactions, three catalyzed by hexokinase 2 (HK2), phosphofructokinase-1 (PFK1), and pyruvate kinase (PK) operate far from equilibrium, and thus provide the primary thermodynamic driving force for glycolysis. The remaining reactions are at near-equilibrium state. The lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) reaction is also exergonic in cancer cells, with an average ΔG of ~–7 kJ/mol. Because the ΔG profile is conserved across diverse cell types, the thermodynamic regulation of metabolite concentrations is systemically stable.

Interstate Between Any Two Steady States

Now consider the transient phase between two steady states—referred to here as the interstate. This occurs when the total activity of any glycolytic enzyme is altered, triggering dynamic shifts in enzyme activity, reaction rate, and metabolite concentrations.

For example, when the total activity of an enzyme decreases, its catalytic rate also falls. As a result, the substrate accumulates, and the product concentration decreases. These changes alter the ΔG of the reaction and, through thermodynamic coupling, propagate upstream and downstream to neighboring steps.

However, this transient state is typically very short-lived, on the order of fractions of a millisecond, and returns to a new steady state after thermodynamic re-equilibration. Although short in duration, this transition can be described quantitatively and reveals how the system dynamically responds to enzyme perturbation (see the subsequent Transient Interstate Between Any Two Steady States).

Summary 1

Steady-state glycolysis is maintained by a balance between enzyme kinetics and chemical thermodynamics. Equal flux through all steps and stable metabolite concentrations are ensured by a coordinated adjustment of enzyme activity and thermodynamic constraints. This defines the principle of kinetic-thermodynamic coupling, which explains how the system achieves stability and balance despite substantial variation in enzyme abundance.

Application of Kinetic-Thermodynamic Coupling to the Regulation of Glycolysis by PKM2

Pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) is the most extensively studied glycolytic enzyme in cancer biology, with over 22,000 results retrieved from a Google Scholar search for “PKM2, glycolysis, cancer.” It is believed to orchestrate metabolic programming by shifting glycolysis between energy-generating and biosynthetic modes.

Traditionally considered a rate-limiting enzyme due to the irreversibility of its reaction, PKM2 activity is tightly regulated through multiple mechanisms: including gene expression via diverse signaling pathways [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17], allosteric inhibition by amino acids (e.g., alanine, phenylalanine, proline, tryptophan, valine) [

18,

19,

20], allosteric activation by fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (FBP), serine, and SAICAR [

21,

22,

23], and post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation [

17,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30], acetylation [

31,

32,

33], hydroxylation [

34], lactylation [

35], oxidation [

36,

37], methylation [

38], and glycosylation [

39].

According to current understanding, this dynamic regulation allows PKM2 to modulate glycolysis in response to the metabolic needs of cancer cells. When PKM2 activity is suppressed, upstream intermediates accumulate, enabling diversion into anabolic pathways such as the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) or serine synthesis pathway (SSP), supporting biomass production and cell growth. Conversely, activation of PKM2 depletes these intermediates and enhances ATP production.

Despite extensive study, the intermediate biochemical mechanisms—how PKM2 exerts its influence over glycolysis—remain largely unexplored.

In this section, I present a mechanistic framework grounded in the principle of kinetic-thermodynamic coupling. This framework reveals how PKM2, its substrates, and the ΔG landscape of the glycolytic pathway interact during metabolic transitions.

To maintain clarity: the total enzyme activity of PKM2 is denoted as PKM2t, the actual catalytic activity within the pathway is denoted PKM2a, and metabolite concentrations are written in brackets (e.g., [PEP] for phosphoenolpyruvate).

Thermodynamic and Kinetic Reasoning

Let us consider two steady states of glycolysis:

Steady state a, where PKM2t is high, and

Steady state b, where PKM2t is low.

When the system transitions from a to b, PKM2t is reduced. However, the upstream flux, such as that catalyzed by hexokinase 2 (HK2), remains constant. As a result, the substrate of PKM2, [PEP], begins to accumulate.

This increase in [PEP] drives the Gibbs free energy of the PKM2 reaction (ΔGPKM2) to become more negative, in other words, the reaction becomes more exergonic. Due to thermodynamic coupling, this perturbation propagates upstream, leading to the accumulation of intermediates including 2-phosphoglycerate (2-PG), 3-phosphoglycerate (3-PG), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GA3P), dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP), and fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (FBP).

However, the propagation does not extend beyond the PFK1-catalyzed step. This is because the PFK1 reaction maintains a highly negative ΔG (≈ –15 kJ/mol) [

4,

5,

6,

7], creating a thermodynamic ‘barrier’ that blocks upstream diffusion of the perturbation.

Even though reduced PKM2t elevates [FBP], the resulting change in ΔGPFK1 is modest and insufficient to bring the reaction near equilibrium. As a result, the concentrations of fructose-6-phosphate (F6P) and glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) remain essentially unchanged.

Thermodynamic Buffering of PKM2 Activity

This thermodynamic redistribution serves a buffering function: as PKM2t changes, opposing changes in [PEP] and [FBP] stabilize PKM2a. Thus, the glycolytic rate is buffered against large variations in total PKM2 levels. Thus, despite large changes in PKM2t, the glycolytic rate remains stable, due to the compensatory shifts in substrate concentration and reaction energetics.

Theoretical Prediction and Experimental Validation

The theoretical framework of kinetic-thermodynamic coupling outlined above yields predictions that have been experimentally tested [

6].

a. Glycolytic flux remains constant despite PKM2 knockdown. An 80% knockdown of PKM2 using siRNA does not reduce glycolytic flux. Glucose uptake and lactate production remain unchanged. This indicates that PKM2a is maintained, despite a sharp drop in PKM2t.

b. [PEP] increases to compensate for reduced PKM2t. As PKM2t decreases, [PEP] rises. This inverse relationship between [PEP] and PKM2t helps maintain a stable PKM2a by compensating for the reduction in enzyme availability through increased substrate concentration.

c. [FBP] increases but remains saturating. [FBP] also rises during PKM2 knockdown. However, because FBP’s

Kd for PKM2 is in the nanomolar range (~25.5 ± 148.1 nM) [

40], and [FBP] in cells is in the hundreds of micromolar to millimolar range [

6], PKM2 is fully saturated with FBP both before and after knockdown. Thus, changes in FBP concentration do not alter PKM2 activity within this range.

d. ΔG shifts confirm pathway redistribution. ΔGPKM2 becomes more negative, consistent with the rise in [PEP]; ΔGPFK1 becomes less negative, due to the accumulation of FBP; ΔG values for other steps remain unchanged; the intermediates in the segment between PFK1 and PKM2 increases proportionally.

e. [F6P] and [G6P] remain stable. Even though ΔGPFK1 becomes slightly less negative, it remains sufficiently exergonic (approximately –13 kJ/mol) to prevent equilibrium and maintain the disequilibrium barrier. As a result, [F6P] and [G6P] levels remain constant, and HK2 activity is unaffected. This insulation of the glycolytic input from downstream disturbances ensures the input flux does not change significantly and suggests that flux to PPP flux does not change significantly.

Summary 2

Both theoretical prediction and experimental evidence support the principle of kinetic-thermodynamic coupling and demonstrate that thermodynamic buffering of intermediate concentrations plays a central role in maintaining glycolytic flux even when PKM2

t is markedly perturbed, which are also schematically shown in

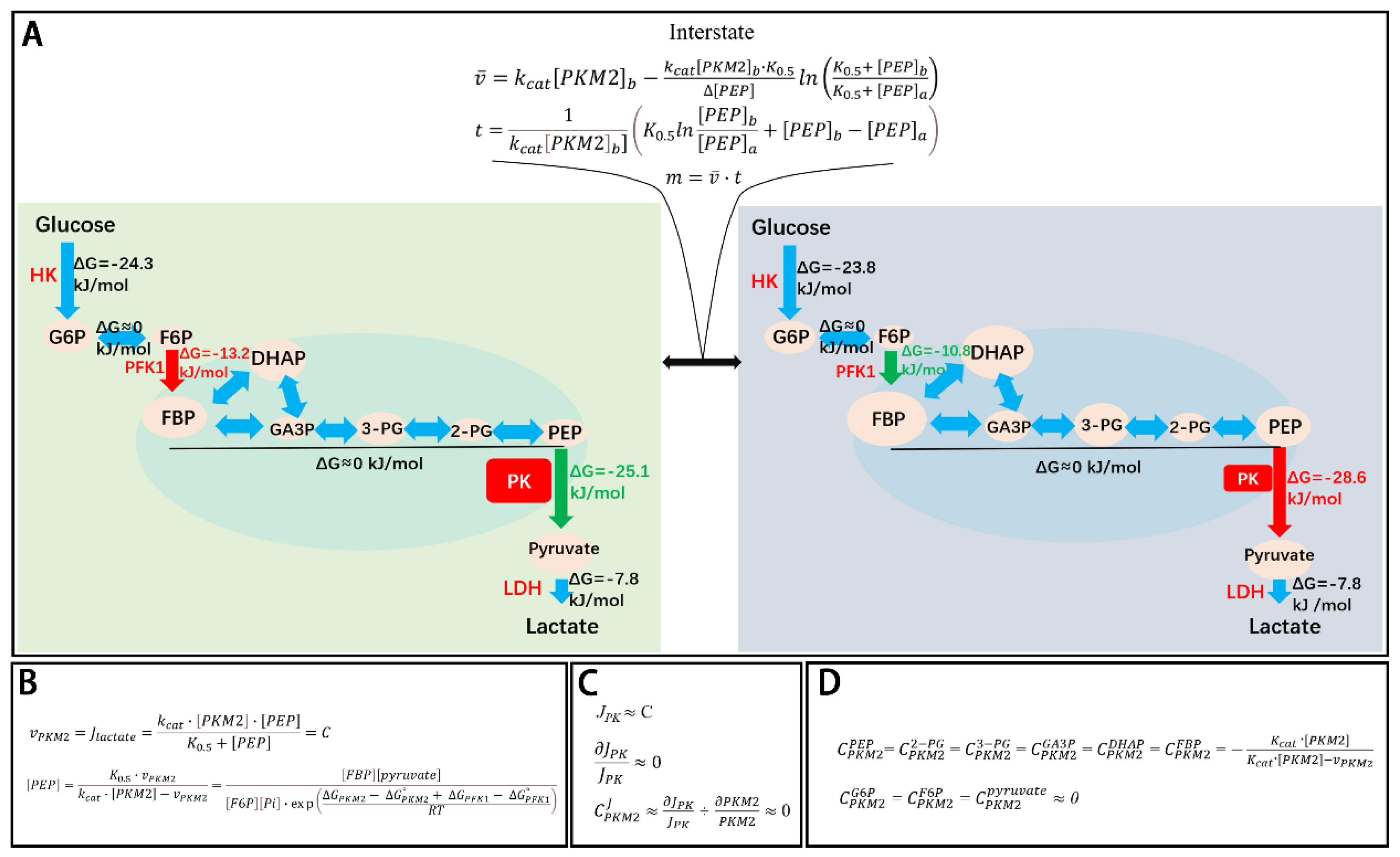

Figure 1A, left and right panels.

Quantitative Coupling of PKM2 Kinetics with Thermodynamics in the Glycolytic Pathway

To quantitatively examine the relationship between PKM2 kinetics and the thermodynamic properties of the glycolytic pathway, we turn to the cell-free glycolysis system. This system is composed of:

Cell lysates containing all glycolytic enzymes

Substrates such as glucose, ATP, ADP, and NAD⁺

Minimal diversion into branch pathways (e.g., PPP, SSP, mitochondrial metabolism)

Thus, the system functions as an isolated, linear glycolytic pathway, progressing from glucose to lactate under steady-state conditions.

Because the system is linear and lacks branching, the rate through each enzyme in the pathway is identical:

Where Jlactate is the rate of lactate generation, Jglycolysis is the rate of glycolysis, Jᵢ refers to the flux through any enzyme in the pathway: JHK2, JPGI, JPFK1, Jaldolase, JTPI, JGAPDH, JPGK1, JPGAM, Jenolase, JPK, and JLDH.

Hence:

where

Jlactate could be experimentally determined and

(

) could be expressed by Michaelis-Menton kinetics [

4,

5,

6,

7]

|

(Eq. 8)

|

However, Since PKM2

a in the glycolytic pathway is regulated by the FBP, and since FBP reduces the

Km without affecting

Vmax,

Km is substituted by

K0.5,

|

(Eq. 9)

|

Eq. 8 is valid only when [FBP] saturates PKM2. The saturation of PKM2 by FBP is calculated based on the equation of the fractional occupancy of enzyme (θ)

|

Where KFBP is the dissociation constant for FBP binding to PKM2

Given:

KFBP ≈ 25.5 ± 148.1 nM

[40] [FBP] ranges from ~35 to 61 μM in cell-free glycolysis, and from ~210 to 1510 μM in cells [

4,

5,

6,

7]

Substituting into the equation of the fractional occupancy of enzyme reveals that PKM2 is nearly 100% saturated with FBP under both in vitro and in vivo conditions.

Therefore, Eq. 8 is valid under physiological and experimental conditions.

Linking Thermodynamics to Kinetics

When [PKM2]% changes between 100% and 20%,

Jlactate remains unchanged,

also remains constant(6). Rearranging Eq. 8 gives:

|

(Eq. 10)

|

[PEP] is not an isolated variable but is constrained by the thermodynamic landscape of the glycolytic pathway. As shown above, changes in PKM2t activity leads to reciprocal changes in ∆GPKM2 and ∆GPFK1: when PKM2t increases, ∆GPKM2 becomes less negative while ∆GPFK1 becomes more negative; conversely, when PKM2t decreases, ∆GPKM2 becomes more negative while ∆GPFK1 becomes less negative; in either case, Gibbs free energy values of other reactions in the glycolytic pathway remains constant. Thus, [PEP] can also be expressed in terms of the actual changes of ∆GPKM2 and ∆GPFK1:

First, since:

|

∆GPKM2 = +RT ln |

which can be rearranged to:

|

(1) |

for PFK1-catalyzed reaction:

|

∆GPFK1 = +RT ln |

which can be rearranged to:

|

(2) |

Substituting (2) into (1) yields

|

Eq. 11

|

Combining Eq. 10 and Eq. 11 yields

|

(Eq. 12)

|

Summary 4

Equations 9 – 11 together means that

PKM2 kinetics is tightly coupled with thermodynamics of the glycolytic pathway.

When [PKM2] or PKM2t decreases, ΔGPKM2 becomes more negative, ΔGPFK1 becomes less negative, and [PEP] increases.

When [PKM2] or PKM2t increases, ΔGPKM2 becomes less negative, ΔGPFK1 becomes more negative, and [PEP] decreases.

This reciprocal changes of ΔGPKM2 and ΔGPFK1 in the glycolytic pathway are the basis for the reciprocal changes of PKM2t and [PEP], that maintains PKM2a and glycolytic rate constant despite the marked change of PKM2t.

Thus, Equations

5–11 form an interdependent system that quantitatively links PKM2

t (total activity), PKM2

a (

vPKM2), [PEP], the thermodynamic landscape of the glycolytic pathway, and

Jlactate (system output) (

Figure 1B).

Relevance to Living Cells

Although derived from a cell-free system, this model applies to living cells based on the experimental observations [

6]:

a) The profile of ΔG values in glycolysis is comparable between cell-free systems and intact cells.

b) PKM2 knockdown leads to the same outcomes in both contexts: glycolytic flux remains stable, ΔGPK becomes more negative, ΔGPFK1 becomes less negative, and intermediate concentrations rise proportionally between PFK1 and PKM2.

c) [FBP] remains saturating for PKM2 in cells (0.21–1.51 mM range).

d) Actual PKM2 activity (PKM2a) is unaffected by knockdown.

Transient Interstate Between Any Two Steady States

Between any two steady states of glycolysis lies a transient intermediate state - a brief period in which both flux and metabolite concentrations are dynamically adjusting. This intermediate phase is quantifiable and reflects the coordinated shifts in enzymatic activity, metabolite pools, and ΔG distribution.

Let’s consider a situation where PKM2t decreases from an initial steady-state level (a) to a new lower level (b), resulting in a shift from steady state a to steady state b. Three key parameters define this transient transition:

m denotes the total amount of substrate processed by PKM2 during the transition

denotes the average catalytic velocity of PKM2 during the transition

t denotes the time required to complete the transition

Given the [PEP] values at the beginning and end of the transition, and FBP is saturating PKM2, the velocity of PKM2 at each steady state can be defined using a Michaelis-Menten-like expression:

At steady state

a (initial):

|

At steady state

b (final):

|

The average velocity (

) during the transition is:

|

(Eq.14)

|

Substituting the equation for

and integrating yields:

|

Solving the integral (see Method) and yielding:

|

(Eq. 15)

|

The time (t) required for the system to transition between steady states is deduced from following:

Because

|

|

Solving the integral (see Method) yields:

|

(Eq. 16)

|

This framework can be applied to:

If PKM2 activity does not change instantaneously but transitions stepwise in n discrete steps, then the total mass (m) and total time (t) are the sums across all transient substates:

|

|

The average velocity over the transition is then:

Notably, the cumulative effect of stepwise transitions is mathematically equivalent to that of a single instantaneous transition from [PKM2]ₐ to [PKM2]b, when integrated across all intermediate states. Therefore, these equations provide a framework for evaluating both instantaneous and gradual transitions between glycolytic steady states

As an example, consider a scenario where PKM2 activity decreases in Hela cells due to siRNA knockdown, resulting in a drop from 958301000 to 286268000 μmol/min·l cells, and during this transition, the intracellular [PEP] increases from 67 to 215 μM (See Method).

Applying Eq. 14, 15 and 16:

|

= 183159000 mol/min·l cells |

|

= 0.049 milliseconds |

|

= 150 μmol/l cells |

This calculation demonstrates that the duration of the interstate is very short so that the total mass processed is small.

Summary 3

Transitions between steady states in glycolysis occur through a brief, quantifiable “interstate” phase (

Figure 1A, middle panel), during which metabolite concentrations and Gibbs free energy values are dynamically redistributed.

This interstate is governed by the same kinetic-thermodynamic principles as the steady state and ensures that the system adjusts efficiently and predictably. The magnitude of intermediate redistribution, the rate of adjustment, and the duration of the transition are all tightly constrained by the pathway’s thermodynamic landscape.

The rapid transitions between steady states are made possible by the micromolar concentrations of glycolytic intermediates, the high catalytic efficiency of enzymes [

4,

5,

6,

7], and the interconnected thermodynamic landscape of the pathway.

Flux Control Coefficient (FCC) of PKM2

FCC is defined as the infinitesimal fractional change in pathway flux (J) in response to an infinitesimal fractional change in enzyme activity:

|

÷ (Eq. 17)

|

Because an 80% knockdown of PKM2 does not significantly affect glycolytic flux, then:

This implies that PKM2 does not exert rate-limiting control under physiological conditions.

Concentration Control Coefficient (CCC) of PKM2

CCC is defined as the fractional change in metabolite concentration [Sⱼ] caused by an infinitesimal change in enzyme activity [Eᵢ]:

|

= ⸱ (Eq. 19)

|

For example, the CCC of PKM2 on [PEP] is:

|

= (Eq. 20 )

|

Rearranged:

|

= (Eq. 21)

|

Resolving the differentiation (see Method) and yielding

|

= (Eq. 22)

|

The value of is negative, which means increasing PKM2 decreases PEP or decreasing PKM2 increases PEP.

Similarly,

could be calculated by the mathematical deduction (see Method)

|

= (Eq. 23)

|

It is not surprising that Eq. 16 is the same as Eq 17, because it is assuming that in the reaction catalyzed by enolase, Q ≈Keq.

Likewise, the CCC of PKM2 over 3-PG, GA3P, DHAP, FBP could be mathematically deduced.

Alternatively, the CCC of PKM2 on 2-PG, 3-PG, GA3P, DHAP, and FBP can be derived from the following reasoning: because the reactions between PEP and FBP are near-equilibrium, the concentrations of all intermediates in this segment change proportionally in response to PKM2 perturbation:

|

=

|

therefore

|

= = = = = = (Eq. 24)

|

In contrast, [F6P], [G6P], and [pyruvate] do not change significantly following PKM2 knockdown. This is consistent with:

Therefore:

|

=

|

|

== 0 (Eq. 25)

|

Summary 5

While PKM2 exerts little control over glycolytic flux (FCC ≈ 0) (

Figure 1C), it strongly influences the concentrations of intermediates in the segment between PKM2 and PFK1 but not other intermediates (

Figure 1D). This arises from the kinetic-thermodynamic architecture of glycolysis and explains how intermediate levels are responsive to enzyme perturbations, even when the pathway output remains stable.

Discussion

At steady state, glycolysis maintains equal flux through all reactions and stable concentrations of intermediates by dynamically coordinating enzyme activity with thermodynamic constraints. This interdependence defines the principle of kinetic-thermodynamic coupling, wherein the kinetics of each step are governed not only by enzyme levels but also by the thermodynamic landscape of the pathway.

While the dynamic adaptability of glycolysis has been extensively studied, the inherent stability of its steady state has received far less attention. The principle of kinetic-thermodynamic coupling suggests that glycolysis possesses a built-in capacity to rapidly reestablish homeostasis following perturbation - such as changes in enzyme activity or substrate levels - typically within a fraction of a millisecond. This perspective reframes our understanding of glycolytic regulation: glycolysis is not merely a passive and flexible pathway that responds to external changes, but a resilient, self-stabilizing system governed by intrinsic thermodynamic and kinetic constraints.

Through the perspective of the kinetic-thermodynamic coupling in the glycolytic pathway, the following insights that have not been previously perceived can be further revealed:

Flux Stability Through Thermodynamic Buffering

When a glycolytic enzyme such as PKM2 is perturbed, the system compensates through thermodynamic adjustments by changing substrate concentrations and redistributing Gibbs free energy (ΔG) across reactions. This thermodynamic buffering maintains a constant actual enzymatic rate (v), even when total enzyme activity varies significantly. As a result, glycolytic flux remains stable across a wide range of enzymatic perturbations. This principle explains experimental observations such as the stability of glycolytic rate despite large reductions in PKM2, GAPDH, PGK1, and LDH activity, and the accompanying rise in substrate concentrations and ΔG changes [

4,

5,

6,

7].

The Interstate Between 2 Steady States

Transitions between steady states occur through a brief and quantifiable interstate phase. During this phase, intermediate concentrations and ΔG values adjust dynamically, but the total substrate turnover and time elapsed are minimal. The interstate is governed by the same kinetic-thermodynamic principles as the steady state, ensuring efficient and predictable transitions. For example, PKM2 perturbation induces a redistribution of [PEP] and ΔGPK within fractions of a millisecond, with negligible cumulative effects on flux or pool size.

Flux and Concentration Control

While enzymes like PKM2 exert little control over overall glycolytic flux (FCC ≈ 0), they strongly influence the concentrations of intermediates between PFK1 and PKM2. This is a natural outcome of the kinetic-thermodynamic architecture: the pathway flexibly adjusts concentrations to maintain flux, while preserving flux stability.

Pathway-Level Thermodynamic Organization

Thermodynamics in linear pathways like glycolysis does more than determine reaction direction, it shapes the entire energetic profile of the system. In contrast to isolated reactions, pathway thermodynamics governs how ΔG is distributed, how intermediate pools are stabilized, and how changes in one step influence others.

The highly exergonic ΔGPFK1 step functions as a thermodynamic barrier, preventing downstream disturbances (e.g., from PKM2, GAPDH, PGK1, LDH) from propagating backward to affect upstream metabolites like [G6P]. This preserves glycolytic input and stabilizes hexokinase (HK2) activity against feedback inhibition.

Feedforward Saturation

Fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (FBP) is a potent allosteric activator of PKM2. However, because [FBP] is present at saturating levels under both basal and perturbed conditions, its concentration fluctuations do not affect PKM2 activity. This feedforward loop is thus insulated by saturation, ensuring that changes in glycolytic rate are not attributed to FBP variation.

A Diagnostic Framework for Enzyme Regulation

Kinetic-thermodynamic coupling provides a testable signature for assessing whether an enzyme (e.g., PKM2) is functionally regulating glycolysis. If regulatory changes of PKM2 (e.g., expression, PTMs, or allosteric effectors) influence glycolysis, one should observe:

- Reciprocal shifts in ΔGPK and ΔGPFK1

- Proportional changes in intermediate concentrations between PFK1 and PKM2

- Stability of upstream ([G6P], [F6P]) and downstream ([pyruvate]) metabolites

- An inverse correlation between PKM2t and [PEP] that preserves PKM2a

The Flux to Lactate and to Side Branches

Based on the proposed principle, along with experimental data, reducing PKM2

t by up to 80% does not significantly decrease PKM2

a in the pathway. Consequently, neither glucose consumption nor flux to lactate is significantly affected. Since the rate to lactate does not change significantly, implying the rate to pyruvate does not change significantly, hence the pyruvate to mitochondrial metabolism would not change significantly. Since [G6P] remains unchanged due to the restraint of ∆G

PFK1, PPP flux is not likely changing significantly. In contrast, [3PG] increases markedly, leading to approximately twofold increase in SSP flux [

6]. Nevertheless, because the flux of 3-PG to SSP is much lower than its flux to lactate, this shift has a negligible impact on overall lactate production. For example, in HeLa cells, the 3-PG flux into SSP is approximately 15 nmol/h per million cells [

41], in contrast to flux to lactate averages around 2000 nmol/h per million cells [

4,

5,

6,

7,

41], twofold increase of SSP negligibly influence the rate to lactate. The flux is schematically showing in

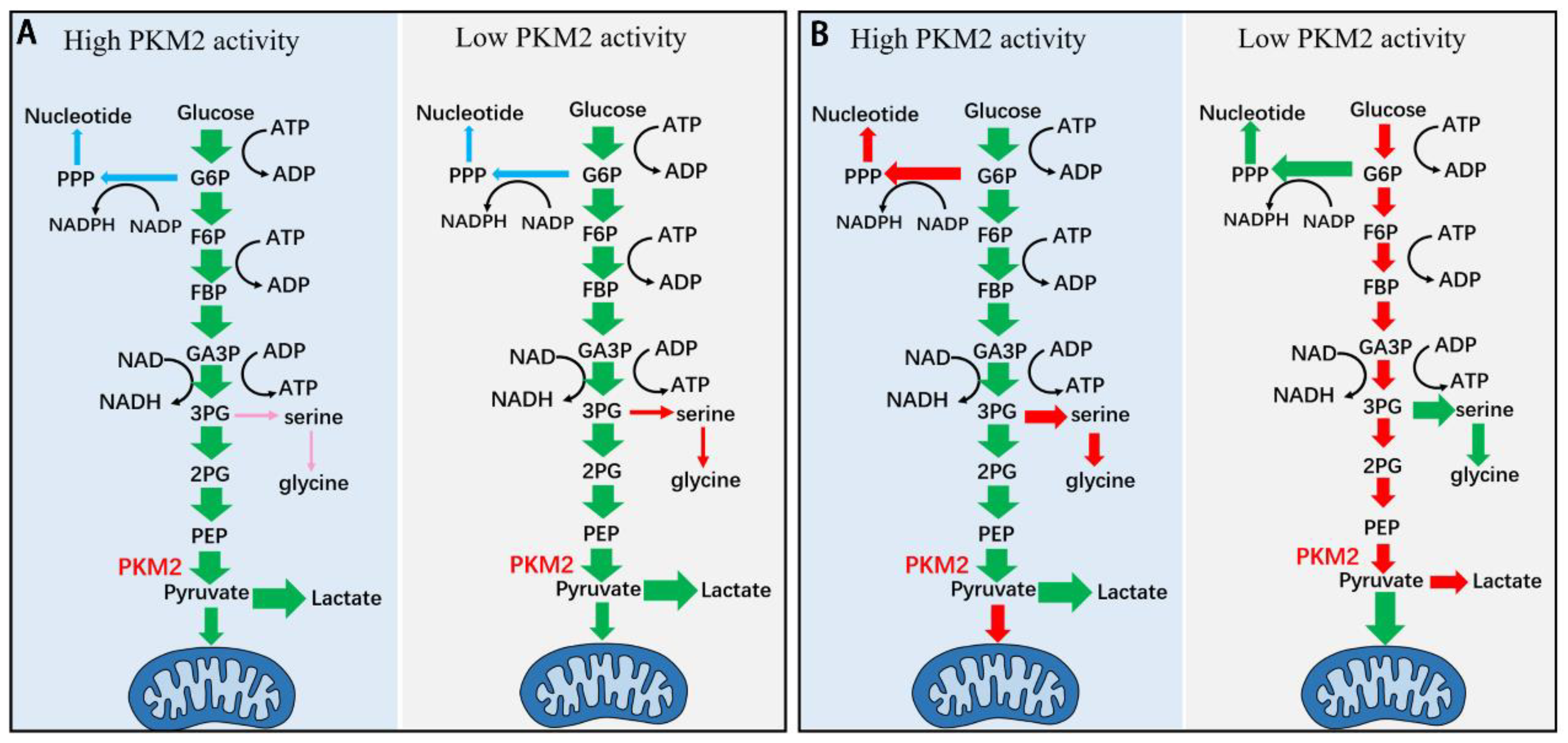

Figure 2.

Beyond PKM2

The same logic applies to other glycolytic enzymes such as GAPDH and PGK1, which also demonstrate thermodynamic redistribution and flux buffering upon perturbation [

4,

5,

6,

7]. More broadly, in any linear or branched metabolic pathway, the interplay between kinetics and thermodynamics is inevitable. Thus, kinetic-thermodynamic coupling may represent a generalizable design principle underlying metabolism.