1. Introduction

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is a rare, acute autoimmune disorder affecting the peripheral nervous system (PNS) and is currently recognized as the leading cause of acute neuromuscular paralysis worldwide, with an annual incidence of 1,12 cases per 100,000 individuals [

1]. GBS often arises following bacterial infections such as Campylobacter jejuni, viral infections including HIV-1, hepatitis C, Zika and Chikungunya viruses, or as a post-infectious complication associated with COVID-19 [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Despite its clinical importance, early diagnosis of GBS remains challenging due to its variable presentation and symptom overlap with other neurological disorders.

Accurate diagnosis typically involves a comprehensive medical history and physical examination, supported by diagnostic tests such as lumbar puncture, used to detect elevated protein levels in cerebrospinal fluid [

7]; electromyography (EMG) to assess muscle response, and nerve conduction studies to evaluate the speed and integrity of peripheral nerve signalling [

8].

Currently, there is no definitive cure for GBS. Treatment strategies focus on immunomodulatory interventions such as plasmapheresis, which removes circulating antibodies contributing to the autoimmune attack, and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy, which provides passive immunization to neutralize pathogenic antibodies [

9,

10]. However, both treatments show variable efficacy, and a subset of patients may experience severe progression requiring intensive care and long-term rehabilitation [

10]. The average cost of hospital treatment per patient is about €950 for plasmapheresis compared to €1,889 for IVIG [

11], and can exceed €10,000 per therapeutic cycle, a figure that increases significantly with ICU admission and longer recovery periods.

The Hospital Nacional de Paraplejicos (HNP) in Toledo is a national referral center for GBS care in Spain, admitting patients from all over the country. Following informed consent, biospecimens such as serum and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) are obtained from these patients and stored in the hospital’s TOSGB Biobank Collection (in Spanish, TOSGB: Toledo, Síndrome de Guillaín Barré). The present article describes the collaborative framework to evaluate GBS patients in Castilla-La Mancha, Spain (BioGBS project) and first results to validate previously described GBS biomarkers [

12,

13]. We have performed a retrospective and longitudinal analysis of biological samples from patients with GBS and matched controls. The study highlights the central role of the biobank in integrating transcriptomic, proteomic, biochemical, and immunophenotypic data to advance our understanding of GBS pathophysiology and identify potential biomarkers related to disease severity, progression, and therapeutic targets.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. GBS Patients and Controls

The use of human material, including PBMC and peripheral blood serum samples from GBS, traumatic SCI patients and healthy individuals, was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee for Hospitals of Toledo City, Castilla-La Mancha, Spain (permit number 17 in Support information), and informed consent was obtained from all individuals in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration. Blood samples of patients and controls were extracted by nursing personnel in the Hospital Nacional de Parapléjicos; and Centro Regional de Transfusiones, bloodbank (Toledo, Spain).

2.2. Whole Blood Processing for PBMCs and Serum

EDTA-anticoagulated whole blood was diluted by half in cold PBS. The diluted blood was carefully decanted, avoiding mixing with Ficoll (Cytiva, Uppsala, Sweden) at a ratio of 10:3. After Ficoll gradient centrifugation at 660 g for 30 minutes at room temperature, a ring of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) was obtained.The PBMC pellet was resuspended in nucleic acid preservative solution (TRIzol; Invitrogen), aliquoted, coded, and stored at -80°C in TOSGB Biobank collection until used for RNA extraction. Approximately 8 ml of whole blood was collected in a sterile gel-barrier tube (FL Medical, Padua, Italy). This kind of tube was used to separate serum from the blood clot, as the gel barrier ascends toward the serum clot during centrifugation, for 10 min at 2650 g. The serum was collected, coded and stored at -80°C in TOSGB Biobank collection until used for various analyses.

2.3. Transcriptomics and Real Time RT-PCR of PBMCs

These two procedures were previously described by us [

12]. Briefly, RNA was extracted from PBMCs in TRIzol and its quality was assessed, showing high RNA integrity. Libraries were prepared using the TruSeq RNA Kit, and the expected fragment size was confirmed using a bioanalyzer. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina GAIIx platform, with a throughput of between 13.4 and 15.7 million 75-base single-end reads per sample. Sequencing data were deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus (accession no. GSE72748). Transcript abundance was quantified using Cufflinks, and differentially expressed genes were identified with Cuffdiff, applying strict significance thresholds. Gene ontology analysis was performed using Blast2GO to interpret functional implications.

Further validation of selected genes, including EGR1, EGR2, and GBP1, was performed through real-time RT-PCR using TaqMan probes and reference genes with stable expression profiles. The expression of Clorf31 was also analyzed using SYBR Green chemistry and primers designed via Primer-BLAST. Normalization was conducted using reference genes, and relative expression levels were determined through the ΔΔCt method. Statistical analysis involved t-tests with appropriate corrections for multiple comparisons to ensure robustness of the gene expression data.

2.4. Proteomic Analysis of Human Serum

Our group previously described data acquisition and proteomic analysis in detail [

13]. Briefly, serum samples from GBS and tSCI patients were analyzed to identify differential protein production. Proteins were extracted, separated by SDS-PAGE, and the concentrated proteins were was processed by Coomassie staining, reduction, alkylation, and enzymatic digestion with trypsin. The resulting peptides were labeled using the iTRAQ 8plex kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), pooled, desalted, and analyzed via reverse-phase liquid chromatography coupled with high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry (RP LC-MS/MS) on an Orbitrap system. A top-20 data-dependent acquisition method with HCD fragmentation was used to generate MS/MS spectra.

Data were processed with Proteome Discoverer and searched against the Uniprot human database; Thermo Proteome Discoverer 1.4, with a Uniprot database containing 147.854 entries of

Homo sapiens (September 8, 2015), and using specific modifications of iTRAQ. Peptides were also matched against reversed databases to control for false discovery rates (FDR ≤ 5%). Quantitative data were obtained using QuiXoT software, and changes in protein levels were assessed using the Generic Integration Algorithm [

14]. Statistical analysis was performed at spectrum, peptide, and protein levels using the WSPP model [

15] to determine significance and ensure data reliability.

2.5. Biochemical Analysis in Human Serum

Serum samples were received at the biochemistry laboratory on ice and kept refrigerated while thawing, until processing, which in most cases was carried out on the same day of reception. The biochemical analysis included the determination of 14 parameters using spectrophotometric techniques on the cobas c 702 analyzer (Roche®). Interleukin 6 (IL-6) was quantified by immunoassay using the cobas e 801 analyzer (Roche®). Meanwhile, the concentrations of sodium (Na⁺), potassium (K⁺), and chloride (Cl⁻) ions were determined by indirect potentiometry using the ion-selective electrode (ISE) module of the cobas c 702. The specific methodology for each biochemical and ionic parameters present in the analyzed samples are explained in following

Table 1.

2.6. Phenotyping in Red Blood Cells

Red blood cell phenotyping was conducted to determine ABO and Rh blood groups. Red blood cell phenotyping was performed to determine ABO and Rh blood groups, extended red cell antigen profiles, the presence of irregular antibodies, and result of the Direct Coombs test. Whole blood samples were collected in EDTA tubes, and analyses were performed using specific antisera with agglutination techniques in microplate, gel column, or microsphere-based platforms, employing various commercial systems (Werfen, Barcelona, and Bio-Rad, Madrid¸ Spain; and QuidelOrtho, San Diego, CA, USA).

ABO and RhD typing were conducted using an automated microplate method with monoclonal IgM reagents. Samples initially typed as RhD negative were further tested with a second, more specific antiserum to detect possible weak or partial RhD variants. Extended phenotyping included additional Rh antigens (C, c, E, e), as well as antigens from other blood group systems such as Kell, Duffy, Kidd, MNS, Lutheran, Lewis, and P1. Reagents used for each antigen were either IgG or IgM, depending on the manufacturer’s recommendations. For irregular antibody screening, patient plasma was incubated with commercial screening red cells using Immucor’s Capture microplate technology (Norcross, GA, USA) to identify unexpected alloantibodies. The Direct Coombs test was performed by adding anti-human globulin reagent to the patient’s red blood cells to detect in vivo coating with immunoglobulin or complement. Agglutination patterns in gel matrices or microplates were interpreted automatically by the analyzers and visually confirmed by laboratory personnel, ensuring accurate and comprehensive immunohematologic profiling.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Each experimental assay was performed with replicates. The reproducibility of biochemical or phenotyping results is based on consistent diagnostic values guaranteed by the local protocol or the equipment of the aforementioned brand.

3. Results

3.1. Recruitment of Participants in BioGBS Study and Inclusion Criteria

This observational and longitudinal study included 113 individuals, 80 patients and 33 controls (

Table 2). All donors were previously informed about the BioGBS study, and informed consent was signed by the donor or a witness if the donor was unable to sign. At the time of writing, the sample size continues to increase to improve gender and age stratification between healthy donors and GBS patients. The number of hospitalized women was lower than that of men in all groups. This could be a sampling artefact due to the low number of GBS patients hospitalized during the study period, a common occurrence in rare diseases (

Table 2).

In the BioGBS study, two types of individuals formed control groups. Patients with traumatic SCI were included as an internal control group to normalize their response during hospitalization, including: rehabilitation program recovery, hostage status, mental health care, etc. Healthy donors included in the BioGBS study were selected with age and sex similar to the GBS group from the Toledo blood donor population attending the local blood bank; blood collection was performed by blood bank staff. Healthy volunteers with the accepted weight and age for blood donation and in good health were included (

Table 1).

3.2. Defined Times Points During GBS Disease for Collection of Serum and PBMCs

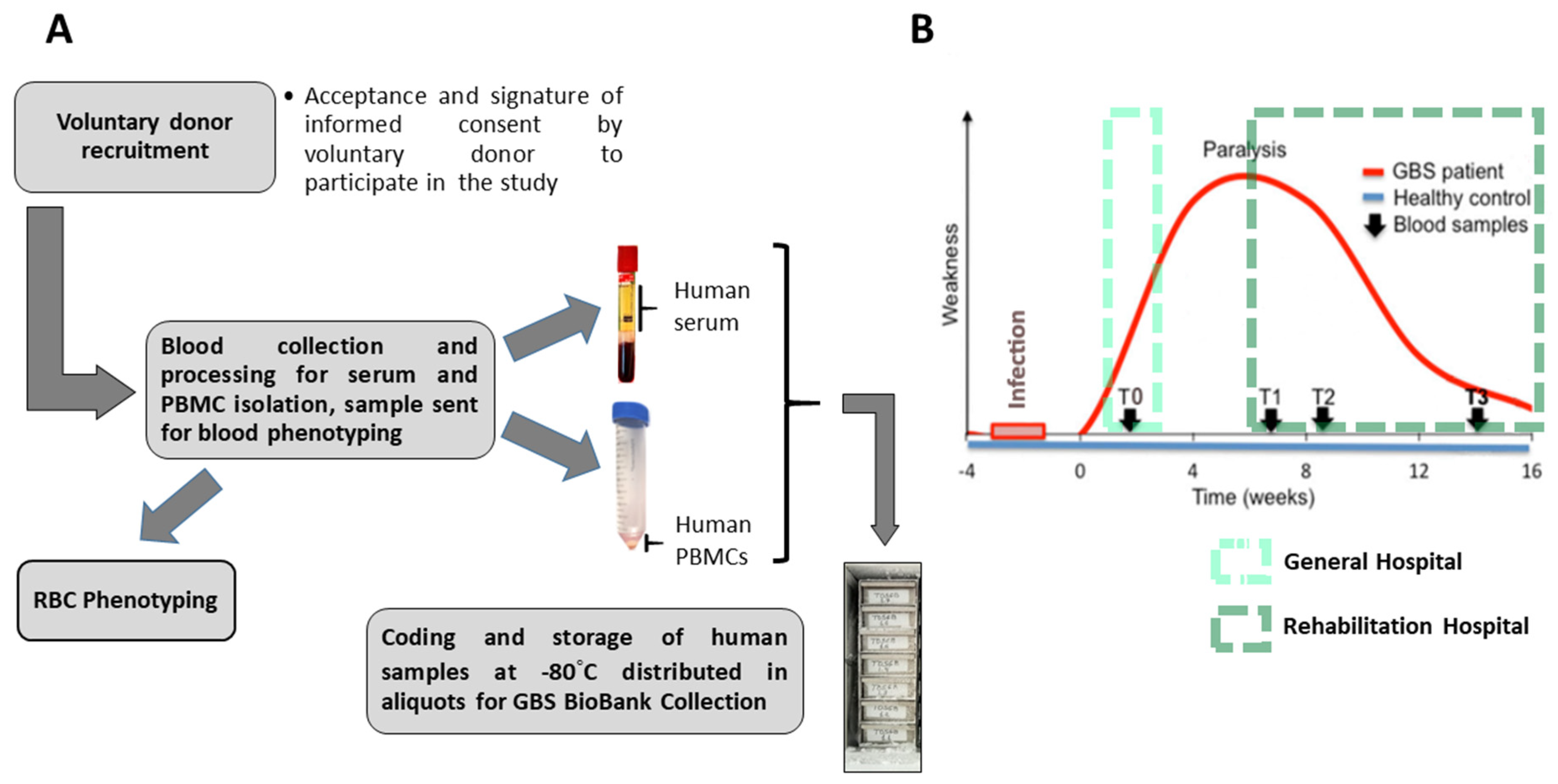

After each volunteer donor accepted and signed the informed consent form to participate in the BioGBS study, blood collection and processing were performed. On the day of collection, human serum and human PBMC pellets were obtained. On the same day as the first collection, an EDTA-anticoagulated blood fraction was sent to the blood bank for erythrocyte phenotyping of each individual. From 9.0 mL of whole blood, between 3.5 and 4.5 mL of human serum were obtained. An initial volume of 27–30 mL of EDTA-anticoagulated blood yields a cell pellet of between 150 and 200 mg of human PBMCs, under our laboratory conditions and using standard methodologies (

Figure 1A).

The present BioGBS study included patients with early (T0), acute (T1), subacute (T2), and moderate GBS (T3). Patients with acute, subacute, and moderate GBS were recruited at the Hospital Nacional de Paraplejicos during their recovery at this rehabilitation hospital. Donors with early GBS are being recruited by the Neurology Department of a local collaborating hospital, where a trained neurologist diagnosed GBS and nursing staff performed blood collection. Patients with early GBS have blood drawn after diagnosis and before clinical-pharmacological treatment (

Figure 1B).

3.3. Quantitative Real-Time PCR in PBMCs, Serum Proteomic Analysis and Serum Antibodies Searching from Samples in GBS Biobank Collection

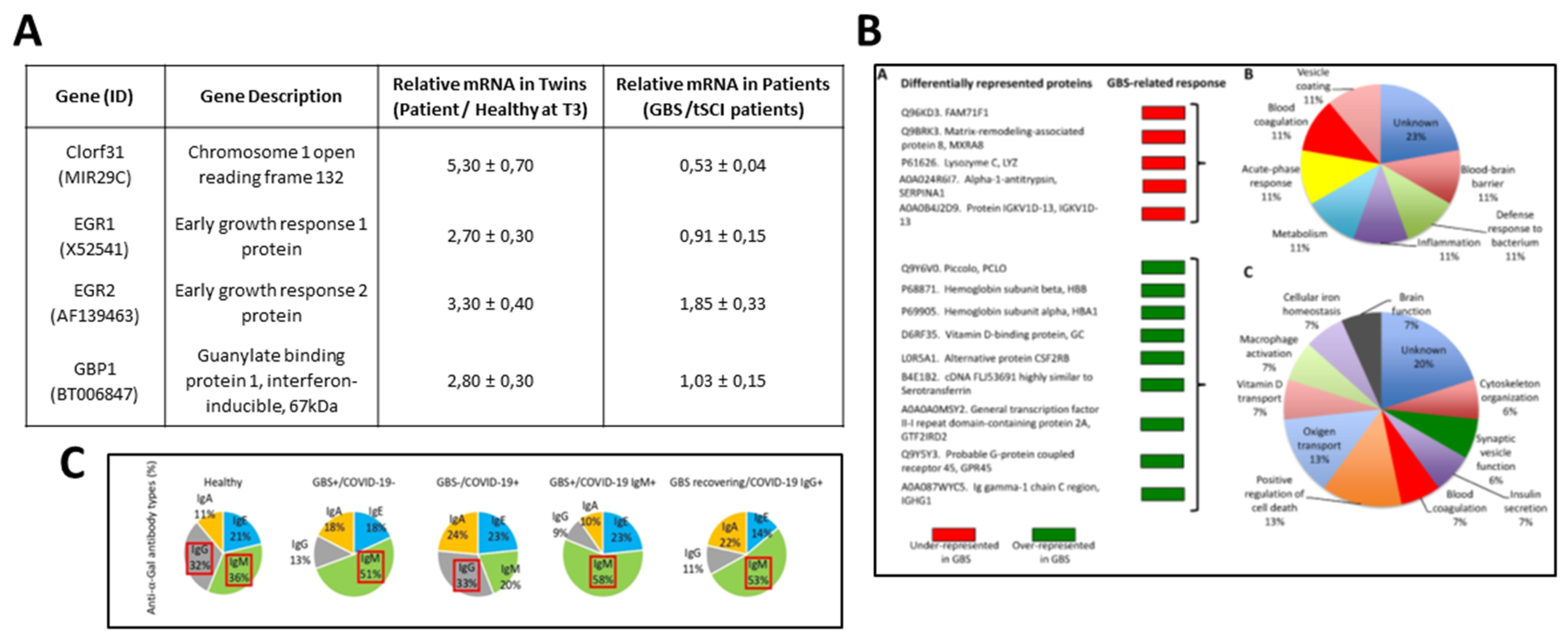

A primary objective of the BioGBS study was to identify markers for GBS progression and recovery [

12,

13]. To this end, PBMCs were obtained from a GBS patient and her healthy twin; this allowed to drastically reduce genetic variations since both share the same genetic background. Genetic studies were performed by transcriptomic analysis of PBMCs isolated at the T1-T3 time points of GBS recovery and corroborated by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. The four overexpressed genes obtained in the GBS patient versus her healthy twin were consistent in GBS patients versus tSCI donors used as an internal control [

12]. Significantly expressed genes related to GBS recovery are shown (

Figure 2A). This gene expression can be validated in PBMC samples from a larger number of GBS patients and controls than in the initial study, which are held in the GBS Biobank collection.

Our group obtained protein markers associated with GBS disease in the serum of GBS patients compared with controls. Nine overexpressed and five underexpressed proteins were identified, a significant protein expression related to GBS [

13]. The role of these serum proteins in GBS progression and recovery can be studied in depth using our GBS sample repository (

Figure 2B).

Another example of the use of serum samples from the GBS Biobank collection was the search for anti-α-Gal antibody types in GBS, GBS-COVID-19, and healthy individuals [

16]. Saccharide-induced immune responses were related to GBS and the α-Gal syndrome (AGS). The AGS is a tick-induced allergy to mammalian meat triggered by the IgE antibody response against the carbohydrate Galα1-3Galβ1-(3)4GlcNAc-R (α-Gal), [

17]. The study concluded that the decreased IgM/IgG antibody response to α-Gal observed in GBS patients could reflect a dysbiosis of the gut microbiota associated with infection with pathogens that trigger neuropathy, and that GBS should not be considered a factor that increases anti-α-Gal IgE levels and, therefore, the risk of tick-bite-related allergies [

16]. This research was made possible through a collaboration between the university research institution, the Hospital Microbiology Service, and the GBS Biobank collection (

Figure 2C).

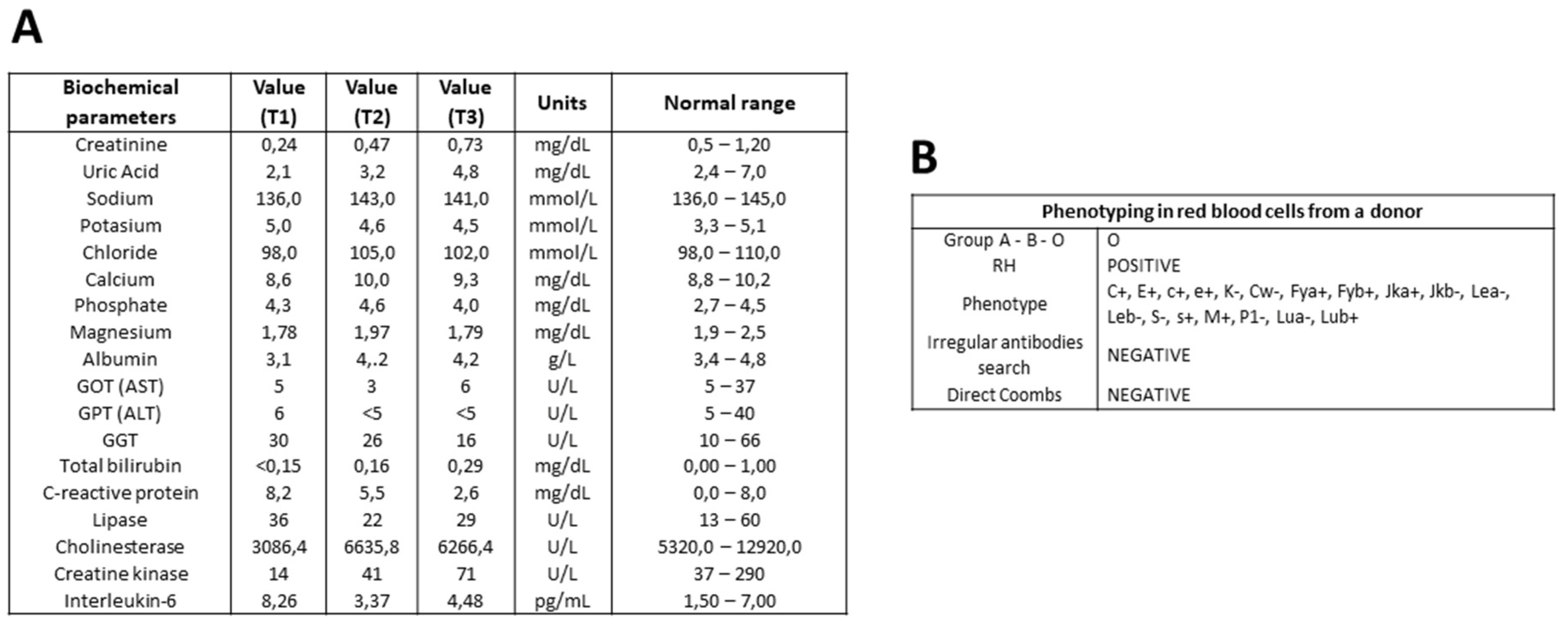

3.4. Serum Biochemical Parameters in GBS Patients During Recovery

Eighteen serum biochemical parameters from patients with GBS and controls are being studied in the GBS Biobank. Samples from each GBS patient, corresponding to different stages of the disease, are analyzed simultaneously to minimize variability in measurements. In a representative determination, values of biochemical parameters such as creatinine, uric acid, calcium, albumin, bilirubin, C-reactive protein, cholinesterase, creatine kinase, and IL-6 tended toward the normal range. Some parameters remained within the normal range at different stages of GBS: sodium, potassium, chloride, phosphate, gamma-glutamyl transferase, and lipase. Liver transferases, GOT, GPT, and magnesium showed fluctuations within the lower limit of accepted range (

Figure 3A).

3.5. Phenotyping of Red Blood Cells in Donors of GBS Biobank Collection

Red blood cell phenotyping is performed on the EDTA-anticoagulated blood of each GBS patient, tSCI patient or control donor on the same day as the first blood draw. ABO blood type and RH are determined, as well as a panel of several surface antigens. A search for irregular antibodies and a direct Coombs’ test complete the blood antigen analysis. An example of individual phenotype screening is shown (

Figure 3B).

4. Discussion

Integrating GBS Biobank Collection resources into our BioGBS studies on gene expression, proteomic analysis, blood biochemical parameters, or phenotyping in Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) offers several advantages. One of the main advantages of using a biobank is access to high-quality, well-preserved biological samples under standardized conditions, which ensures sample integrity and reduces variability in DNA, RNA, protein, and biochemical measurements. This consistency is crucial for reliable biomarker analysis, especially when investigating gene and protein expression or biochemical changes in patients and controls [

18].

Furthermore, biobanks often collect longitudinal samples, allowing for monitoring changes in biomolecules and enzyme activity over time [

19,

20]. This feature is particularly valuable for the study of GBS, as it allows for the evaluation of genes, proteins, or biochemical fluctuations at different stages of the disease. By analyzing serial samples, we can examine possible patterns in the progression of GBS and their relationship with the blood biomolecular markers described [

21]; see

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

Another advantage is the availability of control samples, including samples from healthy individuals or tSCI patients with central or peripheral neuropathies described in tSCI pathology, such as neuropathic pain or nerve root injuries [

22,

23]. These controls are essential for distinguishing GBS-specific biomarkers from those associated with other conditions. Furthermore, some biobanks integrate clinical records with biological samples, providing valuable datasets for studying biochemical variations in different patient populations. Through multicenter collaboration, the GBS Biobank collection was able to track clinical data from the initial, acute, and subacute to moderate course of GBS patients, comparing them with controls.

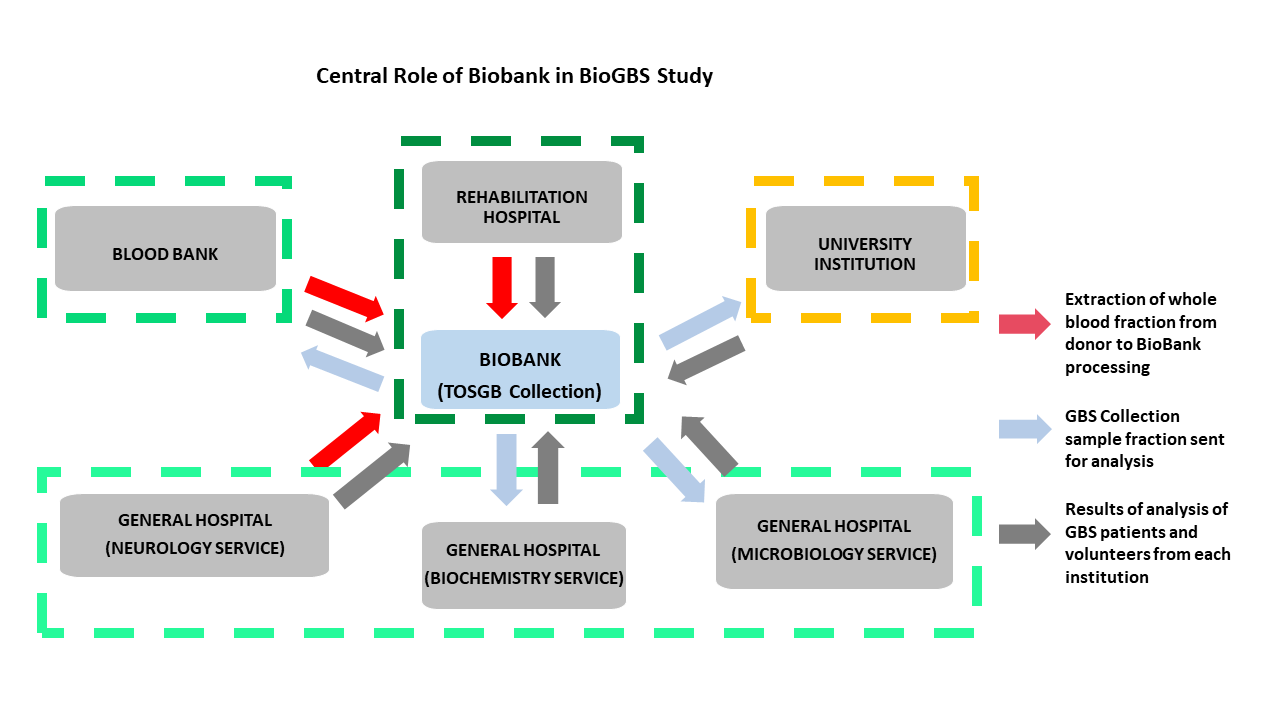

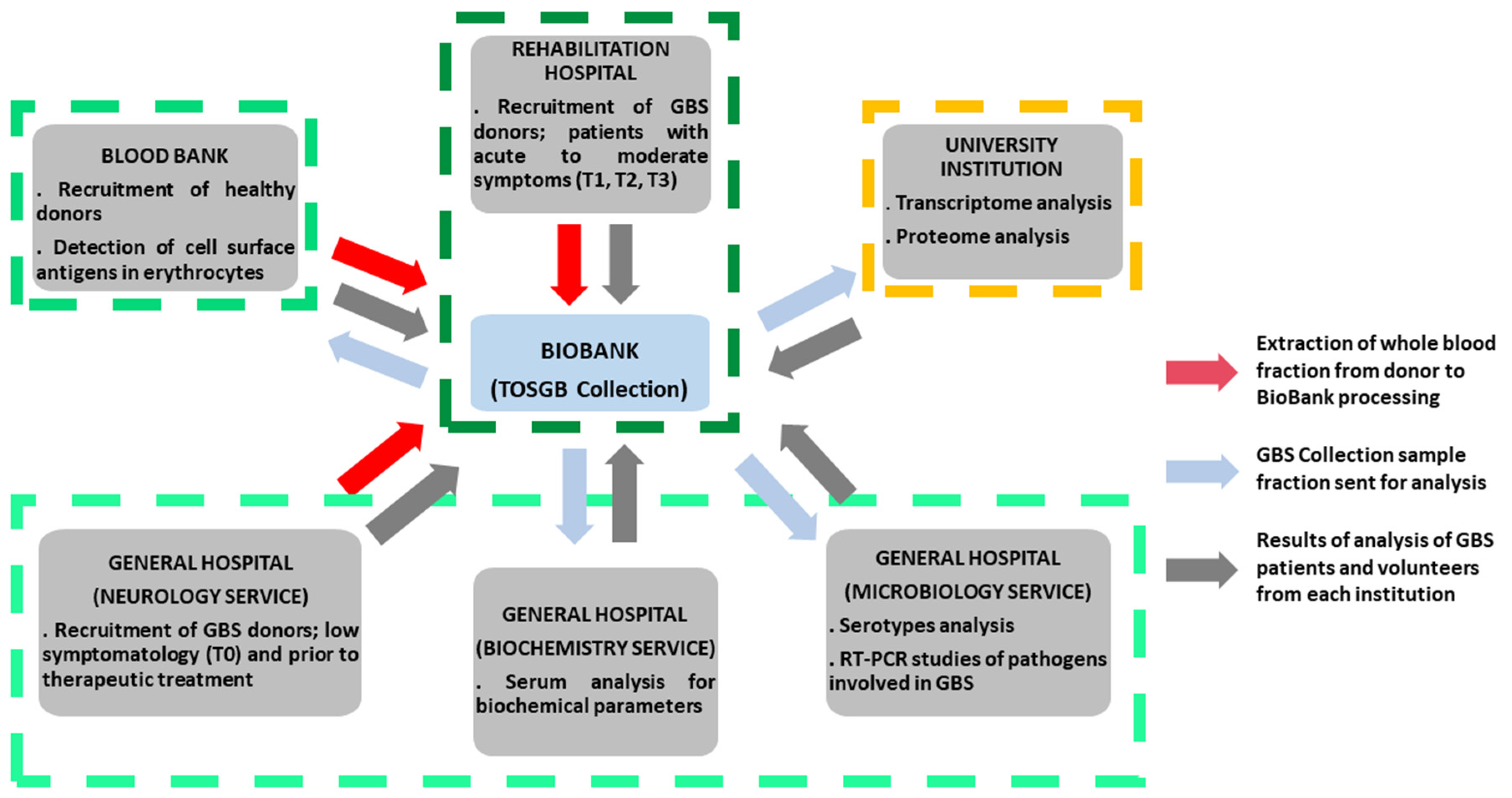

The Biobank’s GBS collection plays a critical role in coordinating collaborations across different medical and academic institutions. This ranges from the recruitment and inpatient follow-up of GBS patients in rehabilitation hospitals to interaction with neurology, biochemistry, and microbiology departments, blood banks for phenotyping and recruitment of healthy donors, and even with research institutes specializing in transcriptomic and proteomic analysis. The availability of well-characterized blood samples facilitates comprehensive biochemical investigations, including enzyme activity assays, metabolic profiles, and immunological assessments. In microbiology departments, biobank resources enable the study of infectious agents or microbial interactions that may influence disease onset and progression in GBS patients (

Figure 4).

Beyond biochemical analysis, biobank resources may provide access to genetic and proteomic data, offering further insights into the molecular mechanisms of GBS. Genetic predispositions, inflammatory pathways, and proteomic changes associated with disease progression could be explored using these datasets, thereby broadening the scope of our research [

24,

25].

Finally, leveraging biobank resources enhances the potential for multi-center collaborations, increasing the generalizability of findings. A broader and more diverse sample set improves the robustness of statistical analyses, strengthening the validity of identified biomarkers. Future studies should consider expanding the use of biobank data to include a wider range of biochemical and molecular analyses to further elucidate the complexity of pathofisiology pathways related to GBS.

The use of samples from Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) biobank collections, while invaluable for advancing research on this rare and heterogeneous disease, has some limitations. One major limitation is the small sample size, as the low incidence of GBS makes it difficult to collect large and statistically robust cohorts. Furthermore, the clinical heterogeneity of GBS, ranging from different subtypes (e.g., AIDP, AMAN) to varying disease severity and treatment regimens, can introduce variability that makes data interpretation difficult. For biobank samples, the lack of comprehensive longitudinal clinical data limits the ability to assess disease progression or long-term outcomes. Furthermore, it is crucial to reduce differences in sample collection, processing, and storage protocols that could affect sample quality and comparability. Ethical and legal considerations, such as restrictions on data sharing and renewing patient consent for new research purposes, can also hinder the wider use of these valuable resources. These limitations must be carefully addressed when designing studies to ensure the validity and reproducibility of findings derived from GBS biobank samples.

5. Conclusions

In this article, we describe studies related to the BioGBS project, including the current cohort of GBS patients and controls, as well as the characteristics of each donor group. We present the blood collection procedures, processing, and storage of human serum and PBMC samples for the GBS Biobank collection, as well as the sampling time points during the course of GBS. We summarize the analysis of GBS Biobank samples using transcriptomics and proteomics, which provided specific biomarkers for GBS. Current results on serum biochemical parameters and phenotyping were presented. Finally, we propose a central role for the GBS Biobank collection in the BioGBS project, integrating all research from different healthcare or academic institutions, which is especially useful in rare disease research.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

R.D.: Processing of human samples; follow-up of GBS (T1, T2, T3) and SCI patients, updating of the TOSGB Biobank database; E.D.-P.: Conceptualization, writing of the original draft, review and editing, project administration, and funding acquisition; J. B.-G., J.R.-G., E.V.-B., C. F.-A., and J.R.T.-T: Recruitment, treatment and follow-up of GBS and SCI patients; A.B., M.C.T.: Recruitment of healthy donors and phenotyping, draft editing. C.M.-A., M.I.M.-C., J.P.-S.: Diagnosis and recruitment of early GBS patients (T0). J.F. and M.V.: Transcriptomic and proteomic analysis, draft preparation and editing. M.Z.-L. and M.S.-R.: Biochemical determinations, draft editing; J.M., L.R.-R.: conceptualization and manuscript editing. All authors have read and accepted this final version of the manuscript.

Funding

We received support from intramural funds (HNP/SESCAM). This research was partially funded by a philanthropic donation from Mr. Hernán Cortés Soria.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and human BioGBS study protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Commission of the Hospital Nacional de Parapléjicos (No. 2022/02, June 2022); and the Toledo Clinical Research Ethics Committee (No. 17, January 2014). The GBS Biobank Collection (TOSGB) was approved by the Toledo Research Commission (No. 191, February 2018) and the Health Councilor of the Regional Government of Castilla-La Mancha (Resolution No. 241/2018, file No. 4500038/0004042 of November 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the BioGBS study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and

Supplementary Materials. The data of biological samples of human origin from TOSGB Collection are coding for donor anonymization. The TOSGB Collection belongs to the Biobank of Hospital Universitario de Toledo, see the relevant permissions and original reports in the

Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the clinical staff and donors without whom this study would not have been possible. R. D.-M., received a financial assistance for the incorporation of research personnel in the healthcare field, Fundación Hospital Nacional de Parapléjicos (Resolution No. 2021/1371).

References

- Xu, L.; Zhao, C.; Bao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liang, Y.; Wei, J.; Liu, G.; Wang, J.; Zhan, S.; Wang, S.; et al. Variation in Worldwide Incidence of Guillain-Barré Syndrome: A Population-Based Study in Urban China and Existing Global Evidence. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tikhomirova, A.; McNabb, E.R.; Petterlin, L.; Bellamy, G.L.; Lin, K.H.; Santoso, C.A.; Daye, E.S.; Alhaddad, F.M.; Lee, K.P.; Roujeinikova, A. Campylobacter Jejuni Virulence Factors: Update on Emerging Issues and Trends. J. Biomed. Sci. 2024, 31, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidal, J.E.; Guedes, B.F.; Gomes, H.R.; Mendonça, R.H. Guillain-Barré Syndrome Spectrum as Manifestation of HIV-Related Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome: Case Report and Literature Review. Brazilian J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 26, 102368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccia, F.; Florio, L.L.; Durante-Mangoni, E.; Zampino, R. Guillain-Barré Syndrome as Clinical Presentation of a Recently Acquired Hepatitis C. J. Neurovirol. 2023, 29, 640–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, M.F. de O.; Nogueira, V.B.; Maury, W.; Wilson, M.E.; Júnior, M.E.T.D.; Teixeira, D.G.; Bezerra Jeronimo, S.M. Altered Cellular Pathways in the Blood of Patients With Guillain-Barre Syndrome. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2025, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S.; Deng, B.; Yu, H.; Zhang, X.; Yang, W.; Chen, X. Clinical and Immunological Features in Patients with Neuroimmune Complications of COVID-19 during Omicron Wave in China: A Case Series. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, U.L.; Desai, N.K.; Yen, K.G. Third Nerve Palsy as First Presenting Symptom of Guillain-Barre Syndrome Spectrum Clinical Variant. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Reports 2025, 38, 102291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, C.; Weng, W.; Wei, Y. Predictors of the Short-Term Outcomes of Guillain–Barré Syndrome: Exploring Electrodiagnostic and Clinical Features. Brain Behav. 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, J.; Negi, G.; Mohan, A.K.; Sharawat, I.K.; Banerjee, P.; Chauhan, D.; Kaur, D.; Jain, A. Potential Advantage of Therapeutic Plasma Exchange over Intravenous Immunoglobulin in Children with Axonal Variant of Guillain-Barré Syndrome: A Report of Six Paediatric Cases. Transfus. Clin. Biol. 2025, 32, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stino, A.M.; Reynolds, E.L.; Watanabe, M.; Callaghan, B.C. Intravenous Immunoglobulin and Plasma Exchange Prescribing Patterns for Guillain-Barre Syndrome in the United States—2001 to 2018. Muscle Nerve 2024, 70, 1192–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, W.; Ali, H.; Muhammad, Y.; Ullah, N.; Khalil, I.; Ahmad, S.; Ullah, O.; Ali, A.; Ali, M.Y.; Manan, A.; et al. Evaluating the Efficacy and Cost-Effectiveness of Plasmapheresis and Intravenous Immunoglobulin in Acute Guillain-Barre Syndrome Management in Emergency Departments. Cureus 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doncel-Pérez, E.; Mateos-Hernández, L.; Pareja, E.; García-Forcada, Á.; Villar, M.; Tobes, R.; Romero Ganuza, F.; Vila del Sol, V.; Ramos, R.; Fernández de Mera, I.G.; et al. Expression of Early Growth Response Gene-2 and Regulated Cytokines Correlates with Recovery from Guillain–Barré Syndrome. J. Immunol. 2016, 196, 1102–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateos-Hernández, L.; Villar, M.; Doncel-Pérez, E.; Trevisan-Herraz, M.; García-Forcada, Á.; Ganuza, F.R.; Vázquez, J.; de la Fuente, J. Quantitative Proteomics Reveals Piccolo as a Candidate Serological Correlate of Recovery from Guillain-Barré Syndrome. Oncotarget 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Marqués, F.; Trevisan-Herraz, M.; Martínez-Martínez, S.; Camafeita, E.; Jorge, I.; Lopez, J.A.; Méndez-Barbero, N.; Méndez-Ferrer, S.; del Pozo, M.A.; Ibáñez, B.; et al. A Novel Systems-Biology Algorithm for the Analysis of Coordinated Protein Responses Using Quantitative Proteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2016, 15, 1740–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, P.; Trevisan-Herraz, M.; Bonzon-Kulichenko, E.; Núñez, E.; Martínez-Acedo, P.; Pérez-Hernández, D.; Jorge, I.; Mesa, R.; Calvo, E.; Carrascal, M.; et al. General Statistical Framework for Quantitative Proteomics by Stable Isotope Labeling. J. Proteome Res. 2014, 13, 1234–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernesto Doncel-Pérez, Marinela Contreras, Cesar Gómez Hernando, Eduardo Vargas Baquero, Javier Blanco García, Javier Rodríguez Gómez, Alberto Velayos Galán, Alejandro Cabezas-Cruz, Christian Gortázar, J. de la F. What Is the Impact of the Antibody Response to Glycan Alpha-Gal in Guillain-Barré Syndrome Associated with SARS-CoV-2 Infection? Merit Res. J. Med. Med. Sci. 2020, 8, 730–737. [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, I.; Fernández de Mera, I.G.; Feo Brito, F.; Gómez Torrijos, E.; Villar, M.; Contreras, M.; Lima-Barbero, J.F.; Doncel-Pérez, E.; Cabezas-Cruz, A.; Gortázar, C.; et al. Characterization of the Anti-α-Gal Antibody Profile in Association with Guillain-Barré Syndrome, Implications for Tick-Related Allergic Reactions. Ticks Tick. Borne. Dis. 2021, 12, 101651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Weiß, C.; Hoffmann, U.; Borggrefe, M.; Akin, I.; Behnes, M. Advantages and Limitations of Current Biomarker Research: From Experimental Research to Clinical Application. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, H.; Willis, C.R.G.; MacKay, M.J.; Rutter, L.A.; Toh, L.S.; Williams, P.M.; Herranz, R.; Borg, J.; Bezdan, D.; Giacomello, S.; et al. Routine Omics Collection Is a Golden Opportunity for European Human Research in Space and Analog Environments. Patterns 2022, 3, 100550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Huang, J.; Wan, J.; Zhong, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, J.; Tan, X.; Yu, B.; Lu, Y.; et al. Physical Frailty, Genetic Predisposition, and Incident Heart Failure. JACC Asia 2024, 4, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oeztuerk, M.; Henes, A.; Schroeter, C.B.; Nelke, C.; Quint, P.; Theissen, L.; Meuth, S.G.; Ruck, T. Current Biomarker Strategies in Autoimmune Neuromuscular Diseases. Cells 2023, 12, 2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, A.; Joshi, M. Occurrence of Neuropathic Pain and Its Characteristics in Patients with Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2024, 47, 952–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredø, H.L.; Rizvi, S.A.M.; Rezai, M.; Rønning, P.; Lied, B.; Helseth, E. Complications and Long-Term Outcomes after Open Surgery for Traumatic Subaxial Cervical Spine Fractures: A Consecutive Series of 303 Patients. BMC Surg. 2016, 16, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, H.; Lewins, M.; Foody, M.G.B.; Gray, O.; Bešević, J.; Conroy, M.C.; Collins, R.; Lacey, B.; Allen, N.; Burkitt-Gray, L. UK Biobank—A Unique Resource for Discovery and Translation Research on Genetics and Neurologic Disease. Neurol. Genet. 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.-T.; You, J.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.-Y.; Wu, X.-R.; Cheng, J.-Y.; Guo, Y.; Long, Z.-W.; Chen, Y.-L.; et al. Atlas of the Plasma Proteome in Health and Disease in 53,026 Adults. Cell 2025, 188, 253–271.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).