1. Introduction

High-speed running and high-intensity actions are essential components of physical performance in elite international female football [

1]. Within these demanding contexts, the ability to effectively execute accelerations and decelerations plays an essential role, significantly contributing to the total distance covered at high intensities, including sprints, during matches [

2]. Since many of these actions are performed unilaterally, the development of interlimb asymmetries is anticipated, as evidenced by previous research which demonstrated that interlimb asymmetries are associated with a decrease in athletic performance [

3,

4,

5]. To meet these physical demands, the implementation of well-designed strength and conditioning programs is crucial, as they not only enhance long-term physical capacities but also help mitigate the risk of injuries [

6].

One promising strategy for optimizing athletic performance is the use of specialized training equipment that enhances power output during sprinting, focusing particularity on the acceleration and deceleration phases with an emphasis on eccentric ( E) loading [

7]. Traditional resistance training methods, such as the use of free weights, often do not sufficiently stimulate the eccentric ( E) phase, missing opportunities to maximize the unique adaptations linked with E contractions [

8]. To address this gap, flywheel training devices –especially cone-shaped versions– have been incorporated into training programs to target improvements during the E phase, thereby enhancing overall performance [

9,

10].

The mechanics of flywheel resistance training rely on the kinetic energy produced during the concentric ( C) phase, requiring a comparable impulse to decelerate the rotational movement of the flywheel [

11]. To maximize training efficiency, athletes are encouraged to exert maximal force during the C acceleration phase, followed by an effective braking action during the E deceleration phase to generate force enhancement in the subsequent acceleration phase [

11]. Achieving E overload, which is defined as having an eccentric-to-concentric ratio ( E:C) greater than one, is a key goal in flywheel training, as it leads to superior neuromuscular adaptations compared to C-dominant training [

12]. Selecting an appropriate internal load is critical to achieving this overload and thus maximizing training outcomes [

6].

Recent studies have sought to determine the impact of varying moments of inertia on crucial training metrics such as peak power, to improve training results and optimize load management [

13,

14,

15]. For example, research has shown that unilateral knee extensions performed with higher moments of inertia (0.075, 0.1 kg·m²) produce greater peak power in both C and E phases compared to lower inertial loads (0.0125, 0.025, 0.0375 kg·m²) [

16]. On the other hand, exercises like squats and deadlifts tend to generate higher peak power at lower moments of inertia indicating that the responses to different inertial loads may be exercise-specific [

13,

15,

17].

The distinct responses of different exercises to changes In moments of inertia have sparked interest in understanding whether similar outcomes are observed for other lower-body exercises, such as leg curls and hip extensions, which target different parts of the hamstring force-length curve [

18,

19].

For instance, Keijzer et al. [

20] demonstrated that, in unilateral leg curls, a wide range of moments of inertia could elicit high E demands, whereas hip extension required greater inertia to achieve E overload. Importantly, these investigations used flywheel devices with inertia values ranging from 0.029 to 0.089 kg·m², highlighting the need for further explorations into how these parameters influence performance outcomes [

6].

Despite the increasing popularity of flywheel training for enhancing E strength, there is still a lack of comprehensive guidelines for its application, particularly within the context of soccer [

6,

21]. Peak power remains the primary variable used to quantify and monitor training loads in flywheel-based protocols, and the E:C ratio has proven to be a reliable measure for assessing eccentric overload when peak power values are used as an absolute metric [

22]. However, additional research is needed to establish comprehensive guidelines for optimizing flywheel training across different muscle groups, thereby enhancing the efficacy of training management and prescription practices. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to examine the effects of varying moments of inertia during the hamstring extension exercise performed with a cone-shaped flywheel device. Specifically, the study aims to evaluate how different inertia settings influence peak and average mechanical outputs and the E:C ratio. The secondary objective was to assess the effect of inertia moments on inter-limb asymmetries. We hypothesized lower moments of inertia will yield higher peak and average mechanical values. As for neuromuscular asymmetries, they will be independent of the external resistance.

3. Results

3.1. Peak Mechanical Outputs Dominant and Non-Dominant Limb Comparisons with Different Moments of Inertia (0.107 kg·m² and 0.133 kg· m²).

Mean and standard deviation from all peak mechanicals outputs (power, angular acceleration and angular speed) with two moments of inertia (107 kg·m² and 0.133 kg·m²) are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Flywheel cone-shape device unilateral hip extension mean ± SD from peak mechanical outputs.

Table 1.

Flywheel cone-shape device unilateral hip extension mean ± SD from peak mechanical outputs.

| |

Load (kg·m²) |

| Variable |

0.107 |

0.133 |

| Concentric |

Eccentric |

Concentric |

Eccentric |

DL Power

(W) |

316.8

(49.9) |

503

(114.3) |

350.7

(111.9) |

511

(91.6) |

NDL Power

(W) |

336.2

(88.7) |

495.1

(110.9) |

337.7

(97.7) |

503

(90.5) |

DL Angular acceleration

(rad/s²) |

246.1

(53.9) |

477.2

(82.5) |

192.3

(20.7) |

390.2

(42.5) |

NDL Angular acceleration

(rad/s²) |

234.3

(41.9) |

443.1

(57.1) |

194.9

(25.1) |

395.8

(54.2) |

DL Angular Speed

(rad/s) |

63.6

(6.9) |

68.6

(6.9) |

58.9

(3.8) |

65.2

(5.3) |

NDL Angular speed

(rad/s) |

62.4

(4.1) |

68.6

(5.9) |

60

(6.3) |

65.5

(5.4) |

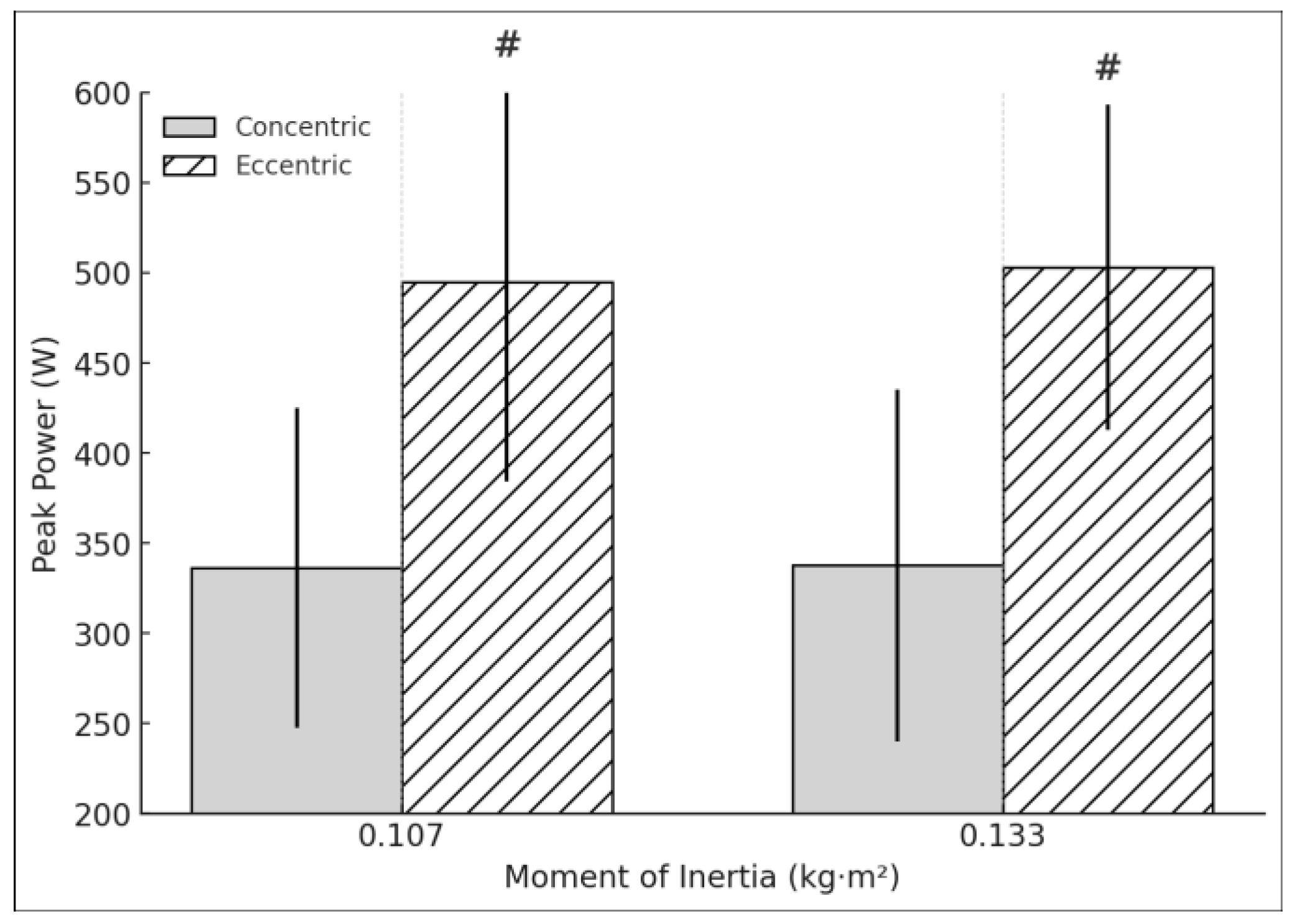

The DL showed no significant differences in concentric peak power between resistances (t = -2.064, p = 0.054, d = -0.473). Likewise, no significant differences were observed in eccentric peak power (t = -0.461, p = 0.65, d = -0.106). The E:C ratio for peak power did not reach statistical significance (t = 1.442, p = 0.166, d = 0.331). The NDL showed no significant differences in concentric peak power between resistances (t = -0.07, p = 0.945, d = -0.016). However, a very large significant relation was found in eccentric peak power (t = 17.674, p < 0.001, d = 3.952). The E:C ratio for peak power did not show significant changes (t = -0.665, p = 0.514, d = -0.149). No significant differences were found in the asymmetry between phases and loads (t = -1.257, p = 0.225, d = -0.288) for the concentric phase, and eccentric phase (t = -0.17, p = 0.867, d = -0.039).

Figure 2.

NDL concentric and eccentric peak power during the hip extension exercise using a flywheel cone-shape device. *Statistically significant (p < 0.05) difference between moments of inertia for the concentric phase. #Statistically significant (p < 0.05) difference between moments of inertia for the concentric phase.

Figure 2.

NDL concentric and eccentric peak power during the hip extension exercise using a flywheel cone-shape device. *Statistically significant (p < 0.05) difference between moments of inertia for the concentric phase. #Statistically significant (p < 0.05) difference between moments of inertia for the concentric phase.

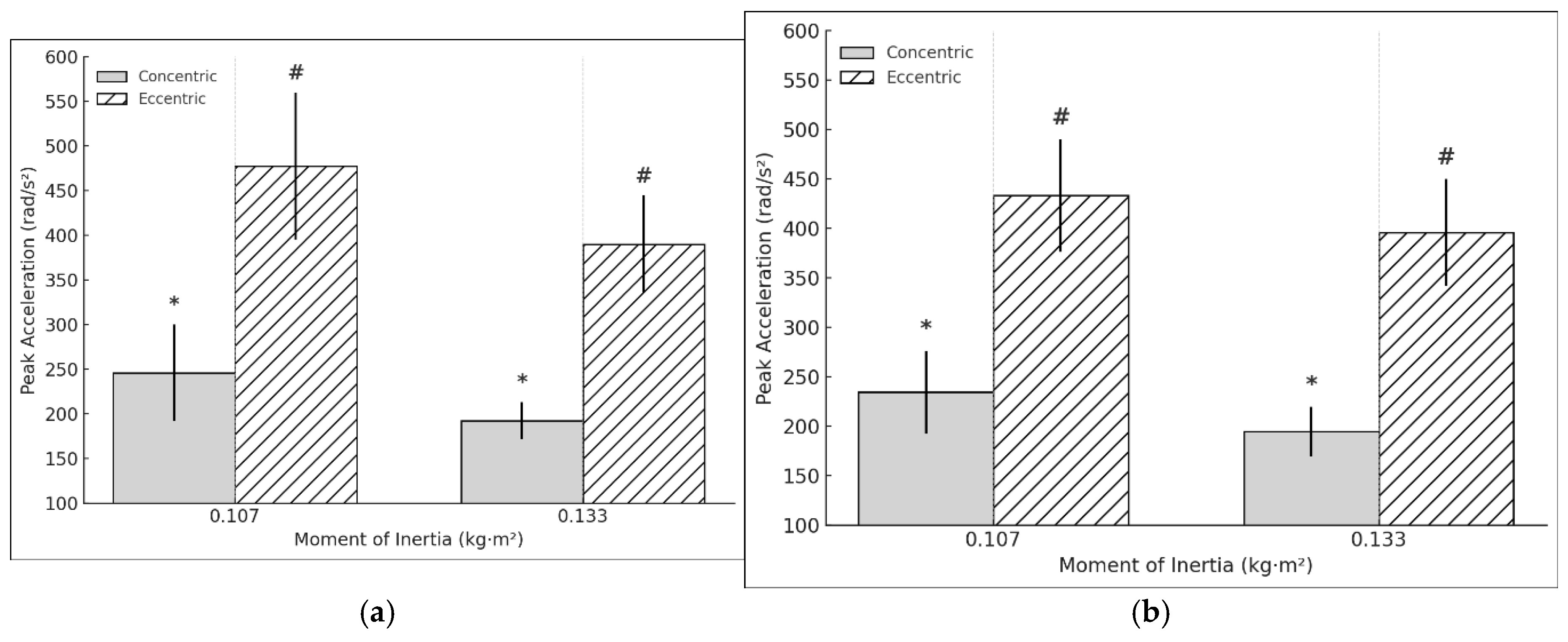

For the aceleration, a moderate significant differences in concentric peak acceleration was observed in the DL when performing the exercise at 0.133 kg·m², compared to 0.107 kg·m² (t = 4.098, p < 0.001, d = 0.94). Similarly, a moderate significant relation was found in eccentric peak acceleration (t = 4.967, p < 0.001, d = 1.14) (

Figure 3a). However, the E:C ratio for acceleration did not show significant changes (t = -1.42, p = 0.173, d = -0.326). In the NDL, moderate significant differences were observed in both concentric peak acceleration (t= 4.026, p < 0.001, d =0.9) and eccentric peak acceleration (t = 3.862, p = 0.001, d = 0.864) (

Figure 3b). Conversely, the E:C ratio for acceleration showed a small negative significant differences (t = -2.218, p = 0.039, d = -0.496). Regarding asymmetry in acceleration, no significant differences were found in the concentric phase (t = 0.936, p = 0.362, d = 0.215). However, a small significant positive relation in eccentric acceleration asymmetry was observed (t = 2.325, p = 0.032, d = 0.533).

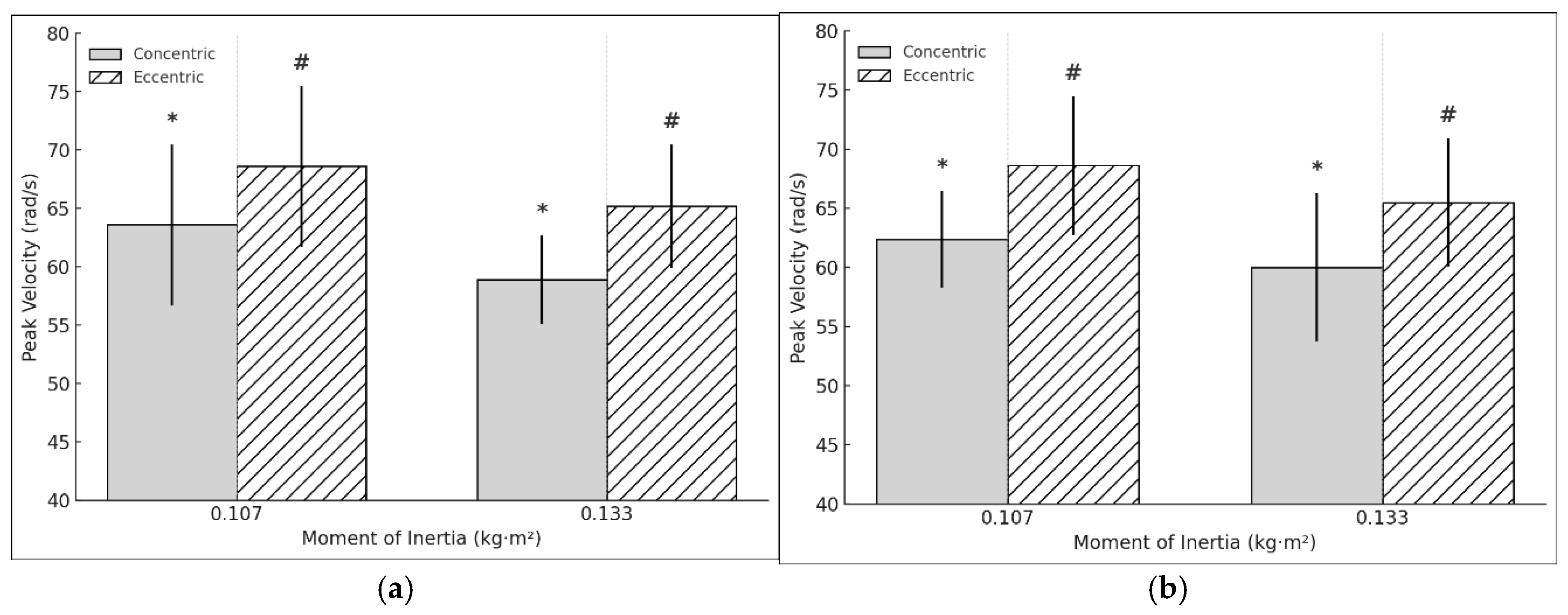

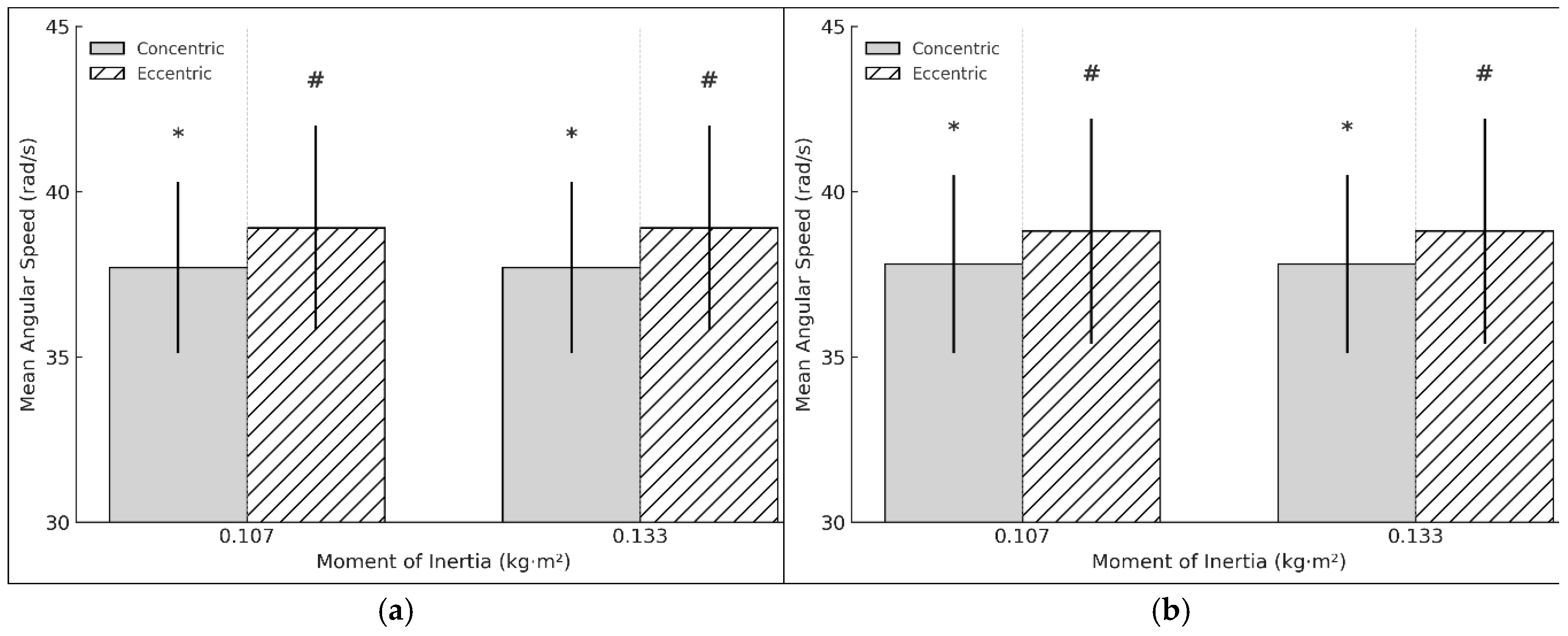

For the speed, a moderate significant relation in concentric peak speed was observed in the DL when performing the exercise at 0.133 kg·m², compared to 0.107 kg·m² (t = 3.493, p = 0.003, d = 0.81) (

Figure 4a). Similarly, a moderate significant relation was found in eccentric peak speed (t = 3.73, p =0.002, d = 0.856) (

Figure 4b). However, the E:C ratio for speed did not show significant changes (t = -1.694, p = 0.108, d = -0.389). In the NDL, moderate significant relation were observed in both concentric peak speed (t = 2.235, p = 0.0038, d = 0.513) and eccentric peak speed (t = 3,548, p = 0.002, d = 0.793). The E:C ratio for speed did not show significant differences (t = 0.635, p = 0.533, d = 0.142). Regarding asymmetry in speed, no significant differences were found in the concentric phase (t = 1.47, p = 0.159, d = 0.337) or the eccentric phase (t = 0.317, p = 0.755, d = 0.073).

3.2. Mean Mechanical Outputs Dominant and Non-Dominant Limb Comparisons with Different Moments of Inertia (0.107 kg·m² and 0.133 kg·m²)

Mean and standard deviation from all mean mechanicals outputs (power, angular acceleration and angular speed) with two moments of inertia (107 kg·m² and 0.133 kg·m²) are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Flywheel cone-shape device unilateral hip extension mean ± SD from mean mechanical outputs.

Table 2.

Flywheel cone-shape device unilateral hip extension mean ± SD from mean mechanical outputs.

| |

Load (kg·m²) |

| Variable |

0.107 |

0.133 |

| Concentric |

Eccentric |

Concentric |

Eccentric |

DL Power

(W) |

155.8

(24.2) |

173.8

(27.2) |

153.9

(22.1) |

173.8

(27.3) |

NDL Power

(W) |

149.7

(23.9) |

172.1

(29.7) |

149.7

(23.9) |

172.1

(29.7) |

DL Angular acceleration

(rad/s²) |

57.4

(7.2) |

70.9

(7.5) |

57.4

(7.2) |

70.9

(7.5) |

NDL Angular acceleration

(rad/s²) |

53.1

(4.9) |

71.7

(8.1) |

53.1

(4.9) |

71.7

(8.1) |

DL Angular Speed

(rad/s) |

37.7

(2.6) |

38.9

(3.1) |

37.7

(2.6) |

38.9

(3.1) |

NDL Angular speed

(rad/s) |

37.8

(2.7) |

38.8

(3.4) |

37.8

(2.7) |

38.8

(3.4) |

No significant differences were found in concetric (t = 0.672, p = 0.51, d = 0.154) or in eccentric average power (t = -0.556, p = 0.585, d = -0.128) for the DL, nor in the E:C ratio (t = -1.253, p = 0.226, d = -0.287). In the NDL, concentric (t = -1.237, p = 0.231, d = -0.277) and eccentric average power (t = -0.774, p = 0.448, d = -0.173) also showed no significant changes, with the E:C ratio remaing stable (t = 0.389, p = 0.701, d = 0.087). Similarly, asymmetry in average power was unaffected in both the concentric (t = 1.326, p = 0.202, d = 0.304) and eccentric phases (t = 0.004, p = 0.965, d = 0.01).

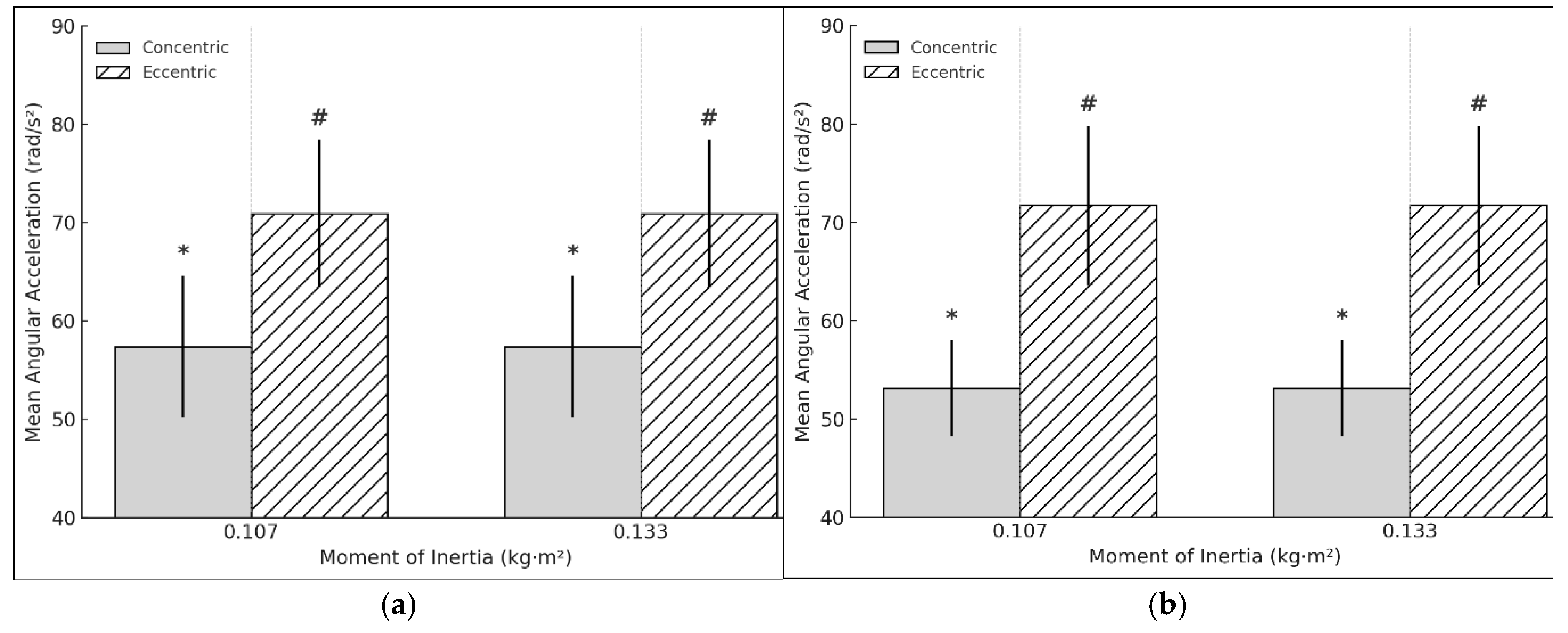

Concentric (t = 7.238, p < 0.001, d = 1.661) and eccentric average acceleration (t = 5.43, p < 0.001, d= 1.246) had large significant relation in the DL at 0.133 kg·m² (

Figure 5a). However, the E:C ratio showed a very large negative significant relation (t = -18.344, p < 0.001, d = -4.208). In the NDL, concentric (t = 6.44, p < 0.001, d = 1.44) and eccentric acceleration (t = 8.6, p < 0.001, d = 1.923) also was found a large significant relation, while the E:C ratio remained unchanged (t = -1.787, p = 0.091, d = -0.41) (

Figure 5b). No significant differences were found in asymmetry during the concentric (t = 1.864, p = 0.079, d = 0.428) or eccentric phase (t = 0.044, p = 0.965, d = 0.01).

Concentric (t = 9.861, p < 0.001, d = 2.262) and eccentric average speed (t = 4.464, p < 0.001, d = 1.024) had a very large and large significant relation in the DL at 0.133 kg·m², while the E:C ratio remained non-significant (t = -1886, p < 0.075, d = -0.433) (

Figure 6a). In the NDL, concentric (t = 9.813, p < 0.001, d = 2.194) and eccentric average speed (t = 5.29, p < 0.001, d = 1.183) also had a large relation, though the E:C ratio showed a large significant relation(t = 5.684, p < 0.001, d = 1.271) (

Figure 6b). No significant differences were found in asymmetry for either the concentric (t = 0.386, p = 0.704, d = 0.089) or eccentric phase (t = 0.349, p = 0.731, d = 0.08).

4. Discussion

The main objective of this study was to examine the effects of altering moments of inertia (0.107 kg·m² and 0.133 kg·m²) on peak and average power, acceleration, and speed during a hip extension exercise. Our findings reveal significant effects on both concentric and eccentric performance, but no significant differences in the eccentric-to-concentric ratio for power, acceleration, or speed between the two inertias. However, variations were observed in individual peak values.

Additionally, the study had aimed to investigate the relationship between the DL and NDL, emphasizing bilateral asymmetry acros different moments of inertia.

We found no significant differences in concentric peak power between the two external resistances in the DL (t = -2.0664, p = 0.054) and NDL (t = -0.07, p = 0.945), suggesting that both resistances elicit similar concentric power outputs. This contrasts with other studies that report increased peak power at higher moments of inertia [

17,

26]. Our findings suggest that, at least in this specific exercise, the effects of increasing external resistance may not always manifest significant differences in peak power, particularly for the concentric phase. However, eccentric peak power revealed a contrasting trend, with a very large significant relationship in the NDL (t = 17.647, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 3.952), highlighting that increased resistance significantly enhances eccentric power. This result aligns with previous findings indicating that higher moments of inertia lead to eccentric overload, further supporting the idea that eccentric power can be effectively enhanced by adjusting resistance [

12,

26]. This finding is consistent with the work of Piqueras-Sanchiz et al. [

17], where eccentric overload was achieved with increased inertia in flywheel training, confirming the importance of eccentric training for strength development.

The acceleration results showed that both concentric and eccentric peak acceleration significantly increased with higher resistance in both the DL and NDL. Specifically, for the DL, concentric acceleration (t = 4.098, p < 0.001) and eccentric acceleration (t = 4.967, p < 0.001) both showed moderate increases with 0.133 kg·m². Similar results were found in the NDL (t = 4.026, p < 0.001 for concentric; t = 3.862, p = 0.001 for eccentric acceleration), suggesting that higher resistance enhances acceleration in both legs. These findings are consistent with Tous-Fajardo et al. [

27], who observed greater neuromuscular activation and acceleration at higher inertia loads.

Interestingly, while E:C ratios for acceleration did not show significant changes in the DL (t = -1.42, p = 0.173) or NDL (t = -2.218, p = 0.039), the eccentric acceleration asymmetry in the NDL (t = 2.325, p = 0.0032) was significantly positive. This suggest that increasing the resistance may lead to slight asymmetry in acceleration between legs, particularly during the eccentric phase. This finding may be attributed to differences in neuromuscular adaptations between the DL and NDL, as previously discussed in the literature [

15].

In terms of speed, both concentric and eccentric peak speed showed moderate significant relationships between resistances for both legs. Specially, for the DL, concentric speed (t = 3.493, p = 0.003) and eccentric speed (t = 3.73, p = 0.002) were significantly higher at 0.133 kg·m², confirming that increased external resistance can enhance speed during both the concentric and eccentric phases. These results are in agreement with Piqueras-Sanchiz et al. [

17] and Muñoz-López et al. [

12], who also reported that higher inertial loads improved speed performance during flywheel training. However, the E:C ratio for speed did not show significant changes in either the DL (t = -1.694, p = 0.108) or NDL (t=0.635, p = 0.533), indicating that while speed improves with higher resistance, the relationship between eccentric and concentric phases remains stable. This suggests that E:C ratios may not be the most reliable measure for assessing flywheel training intensity, as previous mentioned by Maroto-Izquierdo et al. [

26].

For the asymmetry results, we found no significant differences in the concentric phase for either power (t = -1.257, p = 0.225), or speed (t = 1.47, p = 0.159) between limbs, suggesting that concentric performance remains symmetrical despite the increase in external resistance. However, significant differences were found in the eccentric phase, with a small positive correlation in the eccentric acceleration asymmetry (t = 2.325, p = 0.003) and eccentric peak speed asymmetry (t = 3.548, p = 0.002), indicating slight differences between the legs, particularly in the eccentric phase. These results align with studies suggesting that bilateral asymmetry may be more pronounced during eccentric movements due to the differences in motor unit recruitment and neuromuscular control between the legs [

26].

Despite the valuable insights provided by this study, several limitations should be acknowledged: The study may have been conducted with a relatively small sample size, limiting the generalizability of the findings to a broader athletic or clinical population. Future research with larger and more diverse participant groups could help validate these results. Moreover, the study focused exclusively on hip extension exercises, which may limit the applicability of the findings to other lower-body movements, such as squats or lunges. Further studies should examine whether similar effects are observed in different exercises or movement patterns. Furthermore, participants may have had different baseline strength levels, which could have influenced their responses to varying moments of inertia. Although statistical methods were used to analyze the data, future research should consider pre-testing and normalizing resistance loads based on individual strength capacities. The study provides a snapshot of the effects of different inertial loads in a single session. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine how chronic adaptations occur over time with repeated exposure to different inertia levels in training programs. While acceleration, power, and speed were measured, direct neuromuscular activation (e.g., through electromyography) was not assessed. Incorporating EMG analysis could provide deeper insights into the underlying neuromuscular mechanisms driving performance differences. Participants’ familiarity with flywheel training was not explicitly controlled. If some individuals had more experience using flywheel devices, their ability to maximize performance may have differed from less-experienced participants. Future studies should ensure standardized familiarization periods before testing. Although differences between the DL and NDL leg were analyzed, the study did not assess potential biomechanical factors (e.g., limb length, joint angles) that might contribute to asymmetry. Future research should incorporate motion analysis to better understand the causes of these asymmetries. The study did not explicitly control for participants’ effort in generating eccentric overload. Since flywheel training relies on voluntary intent to decelerate, inter-individual differences in effort could have influenced eccentric power outcomes. Standardized coaching cues or real-time feedback mechanisms could help address this limitation in future studies. Addressing these limitations in future research could enhance the reliability and applicability of findings related to inertial training and its effects on power, acceleration, speed, and bilateral asymmetry.

The findings of this study suggest that manipulating moments of inertia during unilateral flywheel hip extension exercises offers a practical strategy for neuromuscular training management. Specifically, increasing the moment of inertia leads to significant reductions in acceleration and speed, which can be used to control the intensity and mechanical demands placed on athletes. Strength and conditioning coaches can leverage higher moments of inertia to target specific neuromuscular adaptations, such as enhancing eccentric strength while intentionally limiting movement velocity. These strategies may be particularly valuable for injury prevention programs, rehabilitation protocols, and individualized load monitoring in elite female football players, where managing eccentric strength and controlling asymmetries are critical for performance and long-term athlete health.

Finally, since the E:C ratio did not show significant changes with increased load, coaches and physiotherapists should consider other metrics, such as absolute eccentric power and acceleration, to assess and adjust the intensity of inertial training more accurately