Submitted:

15 May 2025

Posted:

15 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. Cell Proliferation Assay

2.3. Apoptosis Assay

2.4. Western Blot Analysis

2.5. Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) Incorporation Assay

2.6. Quantitative RT-PCR

2.7. Rescue Experiments

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

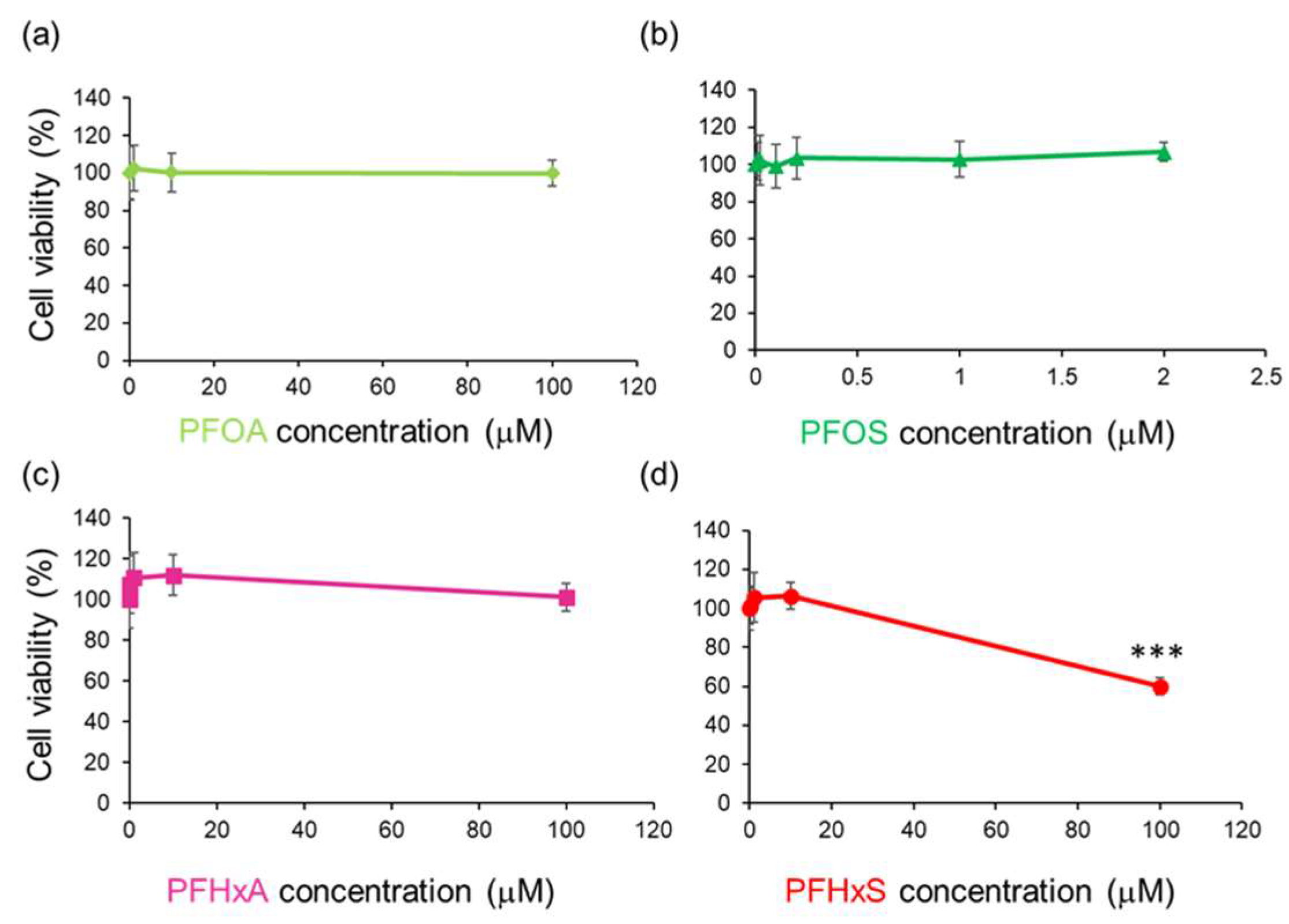

3.1. PFHxS Reduced Cell Viability in HEPM Cells

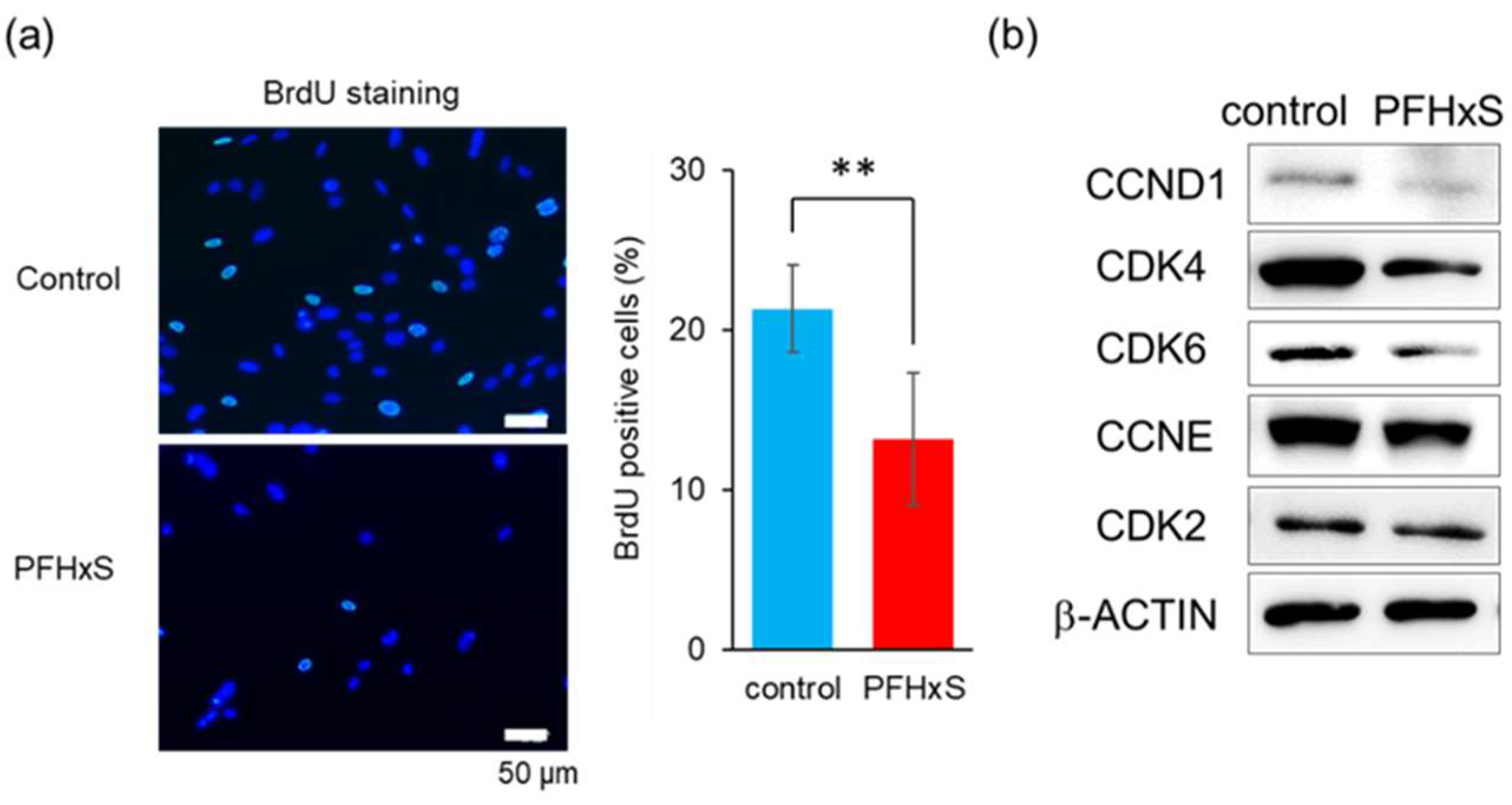

3.2. PFHxS Reduced Cell Viability Through G1 Cell Cycle Arrest

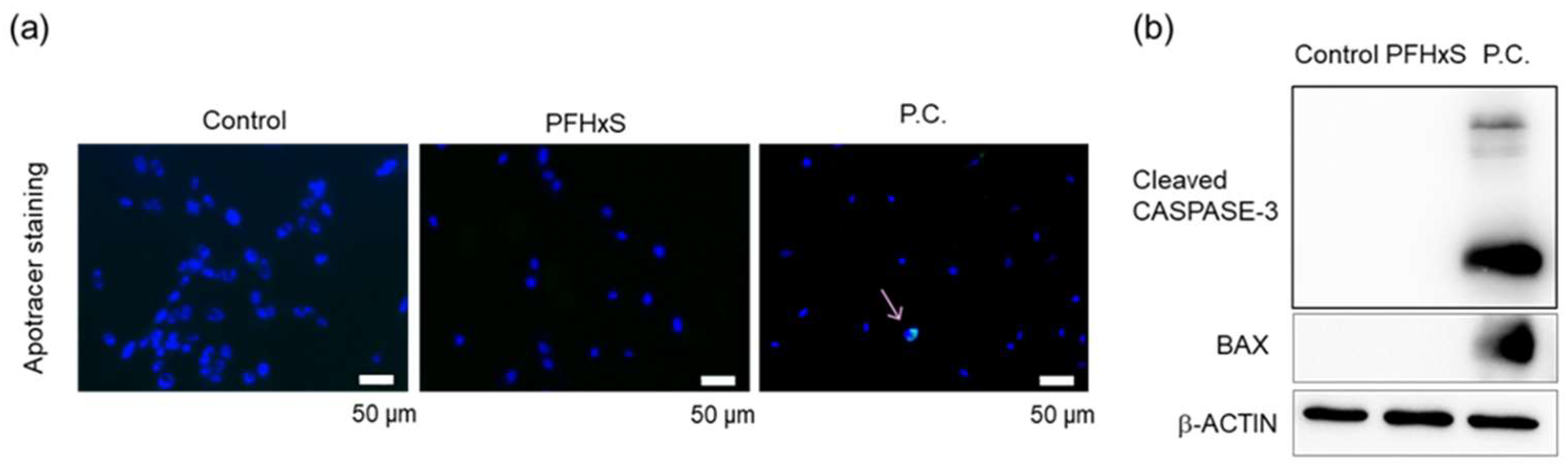

- (A)

- HEPM cells treated with 100 µM PFHxS for 48 h and stained with Apotracker. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. P.C.; positive control (CuCl2). Scale bar, 50 μm.

- (B)

- HEPM cells treated with 100 μM PFHxS for 48 h were subjected to western blotting. β-Actin serving as reference control. P.C.; positive control (CuCl2).

- (A)

- HEPM cells were stained for BrdU (green) after 48-hour treatment with 100 μM PFHxS. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 50 μm. BrdU-positive cell rates are shown. Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). **p<0.01 (Student’s t-test) (n=8).

- (B)

- HEPM cells treated with 100 μM PFHxS for 48 h were subjected to western blotting. β-Actin serving as reference control.

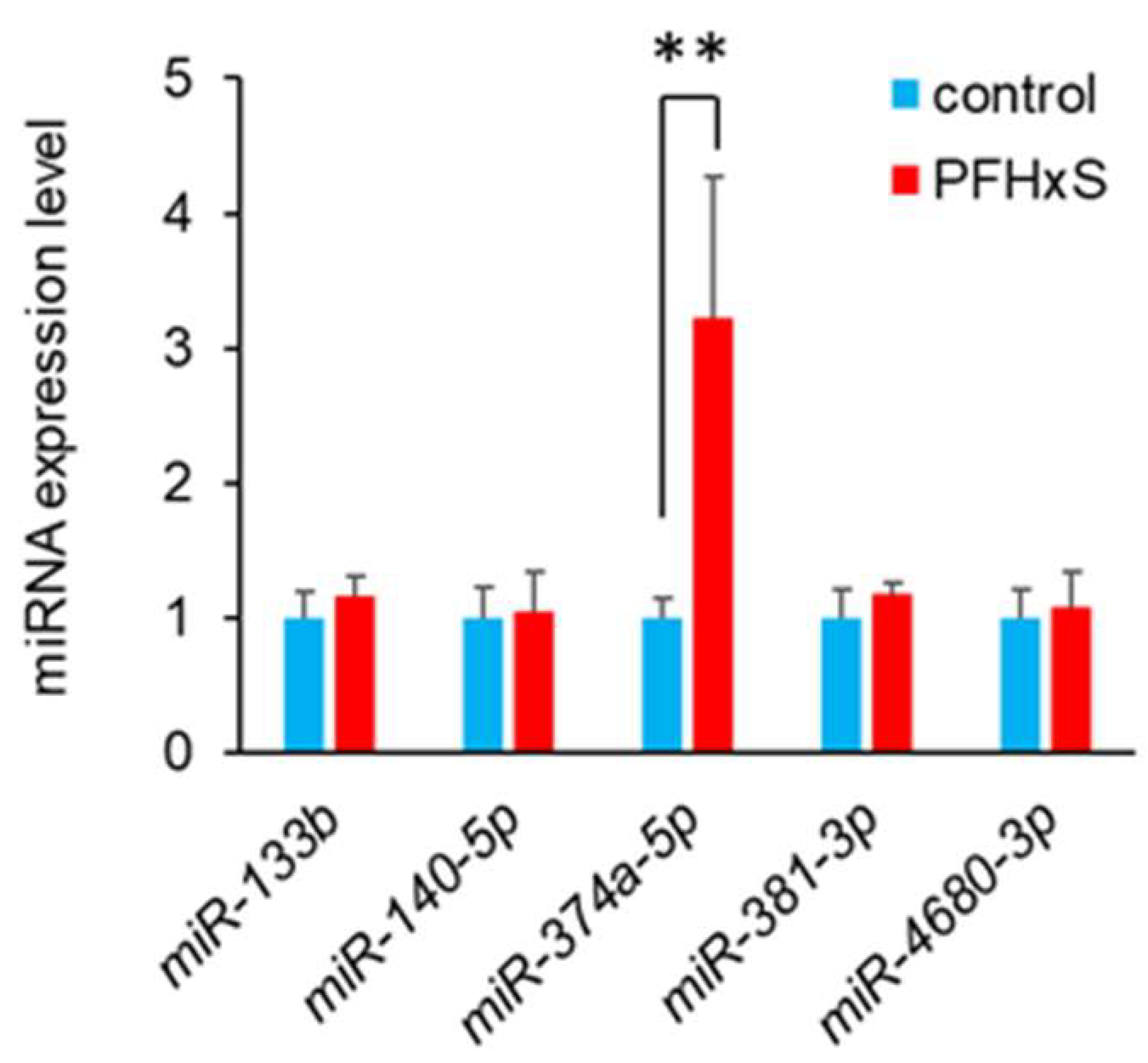

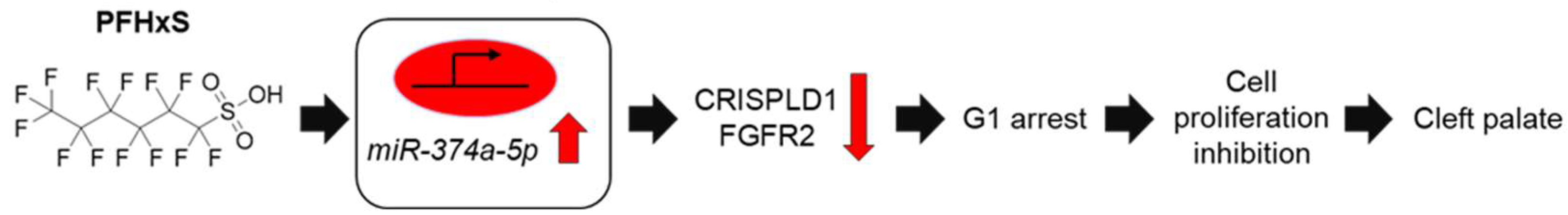

3.3. PFHxS Upregulates miR-374a-5p

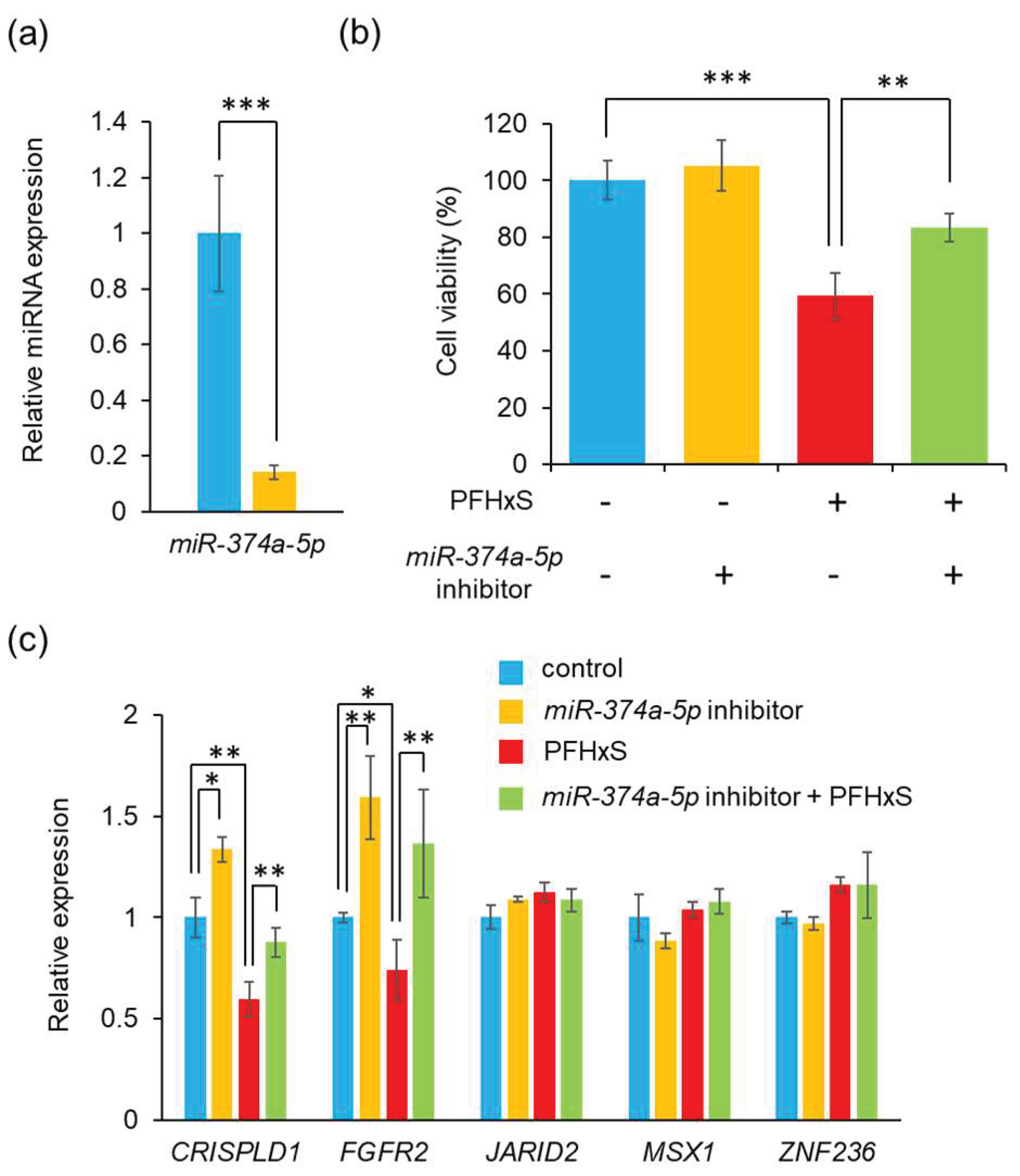

3.4. Blocking miR-374a-5p Alleviates PFHxS-Cediated Cell Proliferation Inhibition

- (A)

- Expression level of miR-374a-5p were measured using quantitative RT-PCR after after transfection of HEPM cells with miR-374a-5p inhibitor for 24 h. Data are shown as the mean ± SD. ***p<0.001 (Tukey’s test) (n=3).

- (B)

- HEPM cell proliferation after 48 h of treatment with 100 μM PFHxS, the miR-374a-5p inhibitor, or their combination. Data are shown as the mean ± SD. **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 (Tukey’s test) (n=6).

- (C)

- Expression level of five predicted genes were evaluated by quantitative RT-PCR following transfection of HEPM cells with the miR-374a-5p inhibitor and/or treatment with 100 μM PFHxS for 48 h. Data are shown as the mean ± SD. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001 (Tukey’s test) (n=4).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMP | bone morphogenetic protein |

| CCND1 | Cyclin D1 |

| CDK | cyclin-dependent kinases |

| CL | Cleft lip |

| CP | Cleft palate |

| CL/P | Cleft lip with or without cleft palate |

| CRISPLD1 | cysteine-rich secretory protein LCCL domain containing 1 |

| DAPI | 4′,6-diamidine-2′-phenylindole dihydrochloride |

| EMT | epithelial-mesenchymal transition |

| FGFR | fibroblast growth factor receptor |

| HEPM | human embryonic palatal mesenchymal |

| JARID2 | jumonji and AT-rich interaction domain containing 2 |

| IgG | immunoglobulin G |

| miRNA | microRNA |

| MSX1 | msh homeobox 1 |

| PCOS | polycystic ovary syndrome |

| PFAS | perfluoroalkyl substances |

| PFHxA | perfluorohexanoic acid |

| PFHxS | perfluorohexanesulfonic acid |

| PFOA | perfluorooctanoic acid |

| PFOS | perfluorooctanesulfonic acid |

| TGF | transforming growth factor |

| ZNF236 | zinc finger protein 236 |

References

- Tomas, E. J.; Valdes, Y. R.; Davis, J.; Kolendowski, B.; Buensuceso, A.; DiMattia, G. E.; Shepherd, T. G., Exploiting Cancer Dormancy Signaling Mechanisms in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Through Spheroid and Organoid Analysis. Cells 2025, 14, (2). [CrossRef]

- Zeber-Lubecka, N.; Ciebiera, M.; Hennig, E. E., Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Oxidative Stress-From Bench to Bedside. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, (18). [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C. G.; Su, S. H.; Chien, W. C.; Chen, R.; Chung, C. H.; Cheng, C. A., Diabetes Mellitus and Gynecological and Inflammation Disorders Increased the Risk of Pregnancy Loss in a Population Study. Life (Basel) 2024, 14, (7). [CrossRef]

- MacLean, J. A., 2nd; Hayashi, K., Progesterone Actions and Resistance in Gynecological Disorders. Cells 2022, 11, (4).

- Tirnovanu, M. C.; Lozneanu, L.; Tirnovanu, S. D.; Tirnovanu, V. G.; Onofriescu, M.; Ungureanu, C.; Toma, B. F.; Cojocaru, E., Uterine Fibroids and Pregnancy: A Review of the Challenges from a Romanian Tertiary Level Institution. Healthcare (Basel) 2022, 10, (5). [CrossRef]

- Breintoft, K.; Pinnerup, R.; Henriksen, T. B.; Rytter, D.; Uldbjerg, N.; Forman, A.; Arendt, L. H., Endometriosis and Risk of Adverse Pregnancy Outcome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med 2021, 10, (4). [CrossRef]

- Witchel, S. F.; Teede, H. J.; Pena, A. S., Curtailing PCOS. Pediatr Res 2020, 87, (2), 353-361.

- Cheng, X.; Du, F.; Long, X.; Huang, J., Genetic Inheritance Models of Non-Syndromic Cleft Lip with or without Palate: From Monogenic to Polygenic. Genes (Basel) 2023, 14, (10). [CrossRef]

- Inchingolo, A. M.; Fatone, M. C.; Malcangi, G.; Avantario, P.; Piras, F.; Patano, A.; Di Pede, C.; Netti, A.; Ciocia, A. M.; De Ruvo, E.; Viapiano, F.; Palmieri, G.; Campanelli, M.; Mancini, A.; Settanni, V.; Carpentiere, V.; Marinelli, G.; Latini, G.; Rapone, B.; Tartaglia, G. M.; Bordea, I. R.; Scarano, A.; Lorusso, F.; Di Venere, D.; Inchingolo, F.; Inchingolo, A. D.; Dipalma, G., Modifiable Risk Factors of Non-Syndromic Orofacial Clefts: A Systematic Review. Children (Basel) 2022, 9, (12). [CrossRef]

- Iwata, J., Gene-Environment Interplay and MicroRNAs in Cleft Lip and Cleft Palate. Oral Sci Int 2021, 18, (1), 3-13. [CrossRef]

- Im, H.; Song, Y.; Kim, J. K.; Park, D. K.; Kim, D. S.; Kim, H.; Shin, J. O., Molecular Regulation of Palatogenesis and Clefting: An Integrative Analysis of Genetic, Epigenetic Networks, and Environmental Interactions. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, (3). [CrossRef]

- Gonseth, S.; Shaw, G. M.; Roy, R.; Segal, M. R.; Asrani, K.; Rine, J.; Wiemels, J.; Marini, N. J., Epigenomic profiling of newborns with isolated orofacial clefts reveals widespread DNA methylation changes and implicates metastable epiallele regions in disease risk. Epigenetics 2019, 14, (2), 198-213. [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, M.; Palmieri, A.; Carinci, F.; Scapoli, L., Non-syndromic Cleft Palate: An Overview on Human Genetic and Environmental Risk Factors. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020, 8, 592271. [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Bian, Z.; Torensma, R.; Von den Hoff, J. W., Biological mechanisms in palatogenesis and cleft palate. J Dent Res 2009, 88, (1), 22-33. [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, H.; Tsukiboshi, Y.; Horita, H.; Kurita, H.; Ogata, A.; Ogata, K.; Horiguchi, H., Sasa veitchii extract alleviates phenobarbital-induced cell proliferation inhibition by upregulating transforming growth factor-beta 1. Traditional & Kampo Medicine 2024, 11, (3), 192-199. [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Zhou, J.; Fanelli, C.; Wee, Y.; Bonds, J.; Schneider, P.; Mues, G.; D'Souza, R. N., Small-molecule Wnt agonists correct cleft palates in Pax9 mutant mice in utero. Development 2017, 144, (20), 3819-3828. [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Zhou, J.; Wee, Y.; Mikkola, M. L.; Schneider, P.; D'Souza, R. N., Anti-EDAR Agonist Antibody Therapy Resolves Palate Defects in Pax9(-/-) Mice. J Dent Res 2017, 96, (11), 1282-1289.

- Li, C.; Lan, Y.; Jiang, R., Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Palate Development. J Dent Res 2017, 96, (11), 1184-1191. [CrossRef]

- Chu, E. Y.; Tamasas, B.; Fong, H.; Foster, B. L.; LaCourse, M. R.; Tran, A. B.; Martin, J. F.; Schutte, B. C.; Somerman, M. J.; Cox, T. C., Full Spectrum of Postnatal Tooth Phenotypes in a Novel Irf6 Cleft Lip Model. J Dent Res 2016, 95, (11), 1265-73. [CrossRef]

- Tamasas, B.; Cox, T. C., Massively Increased Caries Susceptibility in an Irf6 Cleft Lip/Palate Model. J Dent Res 2017, 96, (3), 315-322. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Sun, X.; Braut, A.; Mishina, Y.; Behringer, R. R.; Mina, M.; Martin, J. F., Distinct functions for Bmp signaling in lip and palate fusion in mice. Development 2005, 132, (6), 1453-61. [CrossRef]

- Graf, D.; Malik, Z.; Hayano, S.; Mishina, Y., Common mechanisms in development and disease: BMP signaling in craniofacial development. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2016, 27, 129-39. [CrossRef]

- Ueharu, H.; Mishina, Y., BMP signaling during craniofacial development: new insights into pathological mechanisms leading to craniofacial anomalies. Front Physiol 2023, 14, 1170511. [CrossRef]

- Satokata, I.; Maas, R., Msx1 deficient mice exhibit cleft palate and abnormalities of craniofacial and tooth development. Nat Genet 1994, 6, (4), 348-56. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Song, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, X.; Fermin, C.; Chen, Y., Rescue of cleft palate in Msx1-deficient mice by transgenic Bmp4 reveals a network of BMP and Shh signaling in the regulation of mammalian palatogenesis. Development 2002, 129, (17), 4135-46.

- Scapoli, L.; Martinelli, M.; Pezzetti, F.; Palmieri, A.; Girardi, A.; Savoia, A.; Bianco, A. M.; Carinci, F., Expression and association data strongly support JARID2 involvement in nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Hum Mutat 2010, 31, (7), 794-800. [CrossRef]

- Hammond, N. L.; Dixon, M. J., Revisiting the embryogenesis of lip and palate development. Oral Dis 2022, 28, (5), 1306-1326.

- Wang, X.; Zhao, X.; Zheng, X.; Peng, X.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Meng, M.; Du, J., Sirt6 loss activates Got1 and facilitates cleft palate through abnormal activating glycolysis. Cell Death Dis 2025, 16, (1), 159. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, A.; Li, A.; Gajera, M.; Abdallah, N.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, Z.; Iwata, J., MicroRNA-374a, -4680, and -133b suppress cell proliferation through the regulation of genes associated with human cleft palate in cultured human palate cells. BMC Med Genomics 2019, 12, (1), 93. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, A.; Abdallah, N.; Gajera, M.; Jun, G.; Jia, P.; Zhao, Z.; Iwata, J., Genes and microRNAs associated with mouse cleft palate: A systematic review and bioinformatics analysis. Mech Dev 2018, 150, 21-27. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, A.; Yoshioka, H.; Summakia, D.; Desai, N. G.; Jun, G.; Jia, P.; Loose, D. S.; Ogata, K.; Gajera, M. V.; Zhao, Z.; Iwata, J., MicroRNA-124-3p suppresses mouse lip mesenchymal cell proliferation through the regulation of genes associated with cleft lip in the mouse. BMC Genomics 2019, 20, (1), 852. [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, H.; Li, A.; Suzuki, A.; Ramakrishnan, S. S.; Zhao, Z.; Iwata, J., Identification of microRNAs and gene regulatory networks in cleft lip common in humans and mice. Hum Mol Genet 2021, 30, (19), 1881-1893. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. D.; Lin, Y. S.; Shi, B.; Jia, Z. L., Identifying New Susceptibility Genes of Non-Syndromic Orofacial Cleft Based on Syndromes Accompanied With Craniosynostosis. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2025, 10556656251313842. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. S.; Choi, Y. J.; Cho, J.; Lee, H.; Lee, H.; Park, S. J.; Park, J. S.; Hong, Y. C., Environmental and Genetic Risk Factors of Congenital Anomalies: an Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. J Korean Med Sci 2021, 36, (28), e183. [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Zou, S., Maternal alcohol consumption and oral clefts: a meta-analysis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2019, 57, (9), 839-846. [CrossRef]

- Nicoletti, D.; Appel, L. D.; Siedersberger Neto, P.; Guimaraes, G. W.; Zhang, L., Maternal smoking during pregnancy and birth defects in children: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Cad Saude Publica 2014, 30, (12), 2491-529. [CrossRef]

- Puho, E. H.; Szunyogh, M.; Metneki, J.; Czeizel, A. E., Drug treatment during pregnancy and isolated orofacial clefts in hungary. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2007, 44, (2), 194-202. [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, H.; Suzuki, A.; Iwaya, C.; Iwata, J., Suppression of microRNA 124-3p and microRNA 340-5p ameliorates retinoic acid-induced cleft palate in mice. Development 2022, 149, (9). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Gilboa, S. M.; Herdt, M. L.; Lupo, P. J.; Flanders, W. D.; Liu, Y.; Shin, M.; Canfield, M. A.; Kirby, R. S., Maternal exposure to ozone and PM(2.5) and the prevalence of orofacial clefts in four U.S. states. Environ Res 2017, 153, 35-40.

- Wang, Z.; DeWitt, J. C.; Higgins, C. P.; Cousins, I. T., A Never-Ending Story of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs)? Environ Sci Technol 2017, 51, (5), 2508-2518.

- Gluge, J.; Scheringer, M.; Cousins, I. T.; DeWitt, J. C.; Goldenman, G.; Herzke, D.; Lohmann, R.; Ng, C. A.; Trier, X.; Wang, Z., An overview of the uses of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Environ Sci Process Impacts 2020, 22, (12), 2345-2373. [CrossRef]

- Vazquez Loureiro, P.; Nguyen, K. H.; Rodriguez Bernaldo de Quiros, A.; Sendon, R.; Granby, K.; Niklas, A. A., Identification and quantification of per- and polyfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS) migrating from food contact materials (FCM). Chemosphere 2024, 360, 142360. [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Wang, T.; Liu, S.; Jones, K. C.; Sweetman, A. J.; Lu, Y., Industrial source identification and emission estimation of perfluorooctane sulfonate in China. Environ Int 2013, 52, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhai, Z.; Liu, J.; Hu, J., Estimating industrial and domestic environmental releases of perfluorooctanoic acid and its salts in China from 2004 to 2012. Chemosphere 2015, 129, 100-9. [CrossRef]

- Das, K. P.; Grey, B. E.; Rosen, M. B.; Wood, C. R.; Tatum-Gibbs, K. R.; Zehr, R. D.; Strynar, M. J.; Lindstrom, A. B.; Lau, C., Developmental toxicity of perfluorononanoic acid in mice. Reprod Toxicol 2015, 51, 133-44. [CrossRef]

- Negri, E.; Metruccio, F.; Guercio, V.; Tosti, L.; Benfenati, E.; Bonzi, R.; La Vecchia, C.; Moretto, A., Exposure to PFOA and PFOS and fetal growth: a critical merging of toxicological and epidemiological data. Crit Rev Toxicol 2017, 47, (6), 482-508. [CrossRef]

- Jane, L. E. L.; Yamada, M.; Ford, J.; Owens, G.; Prow, T.; Juhasz, A., Health-related toxicity of emerging per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances: Comparison to legacy PFOS and PFOA. Environ Res 2022, 212, (Pt C), 113431. [CrossRef]

- Omotola, E. O.; Ohoro, C. R.; Amaku, J. F.; Conradie, J.; Olisah, C.; Akpomie, K. G.; Malloum, A.; Akpotu, S. O.; Adegoke, K. A.; Okeke, E. S., Evidence of the occurrence, detection, and ecotoxicity studies of perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) in aqueous environments. J Environ Health Sci Eng 2025, 23, (1), 10. [CrossRef]

- Chain, E. P. o. C. i. t. F.; Knutsen, H. K.; Alexander, J.; Barregard, L.; Bignami, M.; Bruschweiler, B.; Ceccatelli, S.; Cottrill, B.; Dinovi, M.; Edler, L.; Grasl-Kraupp, B.; Hogstrand, C.; Hoogenboom, L. R.; Nebbia, C. S.; Oswald, I. P.; Petersen, A.; Rose, M.; Roudot, A. C.; Vleminckx, C.; Vollmer, G.; Wallace, H.; Bodin, L.; Cravedi, J. P.; Halldorsson, T. I.; Haug, L. S.; Johansson, N.; van Loveren, H.; Gergelova, P.; Mackay, K.; Levorato, S.; van Manen, M.; Schwerdtle, T., Risk to human health related to the presence of perfluorooctane sulfonic acid and perfluorooctanoic acid in food. EFSA J 2018, 16, (12), e05194. [CrossRef]

- Save-Soderbergh, M.; Gyllenhammar, I.; Schillemans, T.; Lindfeldt, E.; Vogs, C.; Donat-Vargas, C.; Ankarberg, E. H.; Glynn, A.; Ahrens, L.; Helte, E.; Akesson, A., Fetal exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in drinking water and congenital malformations: A nation-wide register-based study on PFAS in drinking water. Environ Int 2025, 198, 109381. [CrossRef]

- Thibodeaux, J. R.; Hanson, R. G.; Rogers, J. M.; Grey, B. E.; Barbee, B. D.; Richards, J. H.; Butenhoff, J. L.; Stevenson, L. A.; Lau, C., Exposure to perfluorooctane sulfonate during pregnancy in rat and mouse. I: maternal and prenatal evaluations. Toxicol Sci 2003, 74, (2), 369-81.

- Era, S.; Harada, K. H.; Toyoshima, M.; Inoue, K.; Minata, M.; Saito, N.; Takigawa, T.; Shiota, K.; Koizumi, A., Cleft palate caused by perfluorooctane sulfonate is caused mainly by extrinsic factors. Toxicology 2009, 256, (1-2), 42-7. [CrossRef]

- Tsukiboshi, Y.; Horita, H.; Mikami, Y.; Noguchi, A.; Yokota, S.; Ogata, K.; Yoshioka, H., Involvement of microRNA-4680-3p against phenytoin-induced cell proliferation inhibition in human palate cells. J Toxicol Sci 2024, 49, (1), 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Tominaga, S.; Yoshioka, H.; Yokota, S.; Tsukiboshi, Y.; Suzui, M.; Nagai, M.; Hara, H.; Miura, N.; Maeda, T., Copper-induced renal toxicity controlled by period1 through modulation of Atox1 in mice. Biomed Res 2024, 45, (4), 143-149. [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, H.; Wu, S.; Moriishi, T.; Tsukiboshi, Y.; Yokota, S.; Miura, N.; Yoshikawa, M.; Inagaki, N.; Matsushita, Y.; Nakao, M., Sasa veitchii extract alleviates nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in methionine–choline deficient diet-induced mice by regulating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha. Traditional & Kampo Medicine 2023, 10, (3), 259-268. [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, H.; Tominaga, S.; Amano, F.; Wu, S.; Torimoto, S.; Moriishi, T.; Tsukiboshi, Y.; Yokota, S.; Miura, N.; Inagaki, N.; Matsushita, Y.; Maeda, T., Juzentaihoto alleviates cisplatin-induced renal injury in mice. Traditional & Kampo Medicine 2024, 11, (2), 147-155. [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, H.; Ramakrishnan, S. S.; Shim, J.; Suzuki, A.; Iwata, J., Excessive All-Trans Retinoic Acid Inhibits Cell Proliferation Through Upregulated MicroRNA-4680-3p in Cultured Human Palate Cells. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 618876. [CrossRef]

- Tsukiboshi, Y.; Ogata, A.; Noguchi, A.; Mikami, Y.; Yokota, S.; Ogata, K.; Yoshioka, H., Sasa veitchii extracts protect phenytoin-induced cell proliferation inhibition in human lip mesenchymal cells through modulation of miR-27b-5p. Biomed Res 2023, 44, (2), 73-80. [CrossRef]

- Dhulipala, V. C.; Welshons, W. V.; Reddy, C. S., Cell cycle proteins in normal and chemically induced abnormal secondary palate development: a review. Hum Exp Toxicol 2006, 25, (11), 675-82. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Chen, D.; Wang, A.; Ding, X.; Liu, Z.; Ling, L.; He, Q.; Zhao, T., Folic acid rescue of ATRA-induced cleft palate by restoring the TGF-beta signal and inhibiting apoptosis. J Oral Pathol Med 2011, 40, (5), 433-9. [CrossRef]

- Smane, L.; Pilmane, M.; Akota, I., Apoptosis and MMP-2, TIMP-2 expression in cleft lip and palate. Stomatologija 2013, 15, (4), 129-34.

- Schoen, C.; Aschrafi, A.; Thonissen, M.; Poelmans, G.; Von den Hoff, J. W.; Carels, C. E. L., MicroRNAs in Palatogenesis and Cleft Palate. Front Physiol 2017, 8, 165. [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Jia, P.; Mallik, S.; Fei, R.; Yoshioka, H.; Suzuki, A.; Iwata, J.; Zhao, Z., Critical microRNAs and regulatory motifs in cleft palate identified by a conserved miRNA-TF-gene network approach in humans and mice. Brief Bioinform 2020, 21, (4), 1465-1478. [CrossRef]

- Ulhaq, Z. S.; Tse, W. K. F., Perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS) induces oxidative stress and causes developmental toxicities in zebrafish embryos. J Hazard Mater 2023, 457, 131722. [CrossRef]

- Sherr, C. J.; Roberts, J. M., Living with or without cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases. Genes Dev 2004, 18, (22), 2699-711. [CrossRef]

- Fassl, A.; Geng, Y.; Sicinski, P., CDK4 and CDK6 kinases: From basic science to cancer therapy. Science 2022, 375, (6577), eabc1495. [CrossRef]

- Ettl, T.; Schulz, D.; Bauer, R. J., The Renaissance of Cyclin Dependent Kinase Inhibitors. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, (2).

- Lukasik, P.; Zaluski, M.; Gutowska, I., Cyclin-Dependent Kinases (CDK) and Their Role in Diseases Development-Review. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, (6). [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.; Zunic, A.; Venkat, S.; Feigin, M. E.; Atanassov, B. S., Regulation of Cyclin D1 Degradation by Ubiquitin-Specific Protease 27X Is Critical for Cancer Cell Proliferation and Tumor Growth. Mol Cancer Res 2022, 20, (12), 1751-1762.

- Jablonska, B.; Aguirre, A.; Vandenbosch, R.; Belachew, S.; Berthet, C.; Kaldis, P.; Gallo, V., Cdk2 is critical for proliferation and self-renewal of neural progenitor cells in the adult subventricular zone. J Cell Biol 2007, 179, (6), 1231-45. [CrossRef]

- Ohtsubo, M.; Theodoras, A. M.; Schumacher, J.; Roberts, J. M.; Pagano, M., Human cyclin E, a nuclear protein essential for the G1-to-S phase transition. Mol Cell Biol 1995, 15, (5), 2612-24.

- Huang, J.; Zheng, L.; Sun, Z.; Li, J., CDK4/6 inhibitor resistance mechanisms and treatment strategies (Review). Int J Mol Med 2022, 50, (4).

- Purohit, L.; Jones, C.; Gonzalez, T.; Castrellon, A.; Hussein, A., The Role of CD4/6 Inhibitors in Breast Cancer Treatment. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, (2).

- Lee, R. C.; Feinbaum, R. L.; Ambros, V., The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 1993, 75, (5), 843-54. [CrossRef]

- Wightman, B.; Ha, I.; Ruvkun, G., Posttranscriptional regulation of the heterochronic gene lin-14 by lin-4 mediates temporal pattern formation in C. elegans. Cell 1993, 75, (5), 855-62. [CrossRef]

- Artigas-Arias, M.; Curi, R.; Marzuca-Nassr, G. N., Myogenic microRNAs as Therapeutic Targets for Skeletal Muscle Mass Wasting in Breast Cancer Models. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, (12). [CrossRef]

- Shull, L. C.; Artinger, K. B., Epigenetic regulation of craniofacial development and disease. Birth Defects Res 2024, 116, (1), e2271. [CrossRef]

- Shulman, E.; Kargoli, F.; Aagaard, P.; Hoch, E.; Di Biase, L.; Fisher, J.; Gross, J.; Kim, S.; Ferrick, K. J.; Krumerman, A., Socioeconomic status and the development of atrial fibrillation in Hispanics, African Americans and non-Hispanic whites. Clin Cardiol 2017, 40, (9), 770-776.

- Wang, J.; Bai, Y.; Li, H.; Greene, S. B.; Klysik, E.; Yu, W.; Schwartz, R. J.; Williams, T. J.; Martin, J. F., MicroRNA-17-92, a direct Ap-2alpha transcriptional target, modulates T-box factor activity in orofacial clefting. PLoS Genet 2013, 9, (9), e1003785.

- Pan, Y.; Li, D.; Lou, S.; Zhang, C.; Du, Y.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, W.; Ma, L.; Wang, L., A functional polymorphism in the pre-miR-146a gene is associated with the risk of nonsyndromic orofacial cleft. Hum Mutat 2018, 39, (5), 742-750. [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, H.; Jun, G.; Suzuki, A.; Iwata, J., Dexamethasone Suppresses Palatal Cell Proliferation through miR-130a-3p. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, (22). [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, H.; Mikami, Y.; Ramakrishnan, S. S.; Suzuki, A.; Iwata, J., MicroRNA-124-3p Plays a Crucial Role in Cleft Palate Induced by Retinoic Acid. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 621045. [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Chen, Q.; Du, H.; Qiu, L., 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-Dioxin Suppresses Mesenchymal Cell Proliferation and Migration Through miR-214-3p in Cleft Palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2024, 10556656241286314. [CrossRef]

- Gajera, M.; Desai, N.; Suzuki, A.; Li, A.; Zhang, M.; Jun, G.; Jia, P.; Zhao, Z.; Iwata, J., MicroRNA-655-3p and microRNA-497-5p inhibit cell proliferation in cultured human lip cells through the regulation of genes related to human cleft lip. BMC Med Genomics 2019, 12, (1), 70. [CrossRef]

- Kouroupis, D.; Kaplan, L. D.; Huard, J.; Best, T. M., CD10-Bound Human Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cell-Derived Small Extracellular Vesicles Possess Immunomodulatory Cargo and Maintain Cartilage Homeostasis under Inflammatory Conditions. Cells 2023, 12, (14). [CrossRef]

- Fathi, M.; Omrani, M. A.; Kadkhoda, S.; Ghahghaei-Nezamabadi, A.; Ghafouri-Fard, S., Impact of miRNAs in the pathoetiology of recurrent implantation failure. Mol Cell Probes 2024, 74, 101955. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Wang, H.; Xu, Y.; Wang, M.; Tian, Z., miR-374a-5p inhibits non-small cell lung cancer cell proliferation and migration via targeting NCK1. Exp Ther Med 2021, 22, (3), 943.

- Chiquet, B. T.; Henry, R.; Burt, A.; Mulliken, J. B.; Stal, S.; Blanton, S. H.; Hecht, J. T., Nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate: CRISPLD genes and the folate gene pathway connection. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2011, 91, (1), 44-9. [CrossRef]

- Creton, M.; Wagener, F.; Massink, M.; Fennis, W.; Bloemen, M.; Schols, J.; Aarts, M.; van der Molen, A. M.; van Haaften, G.; van den Boogaard, M. J., Concurrent de novo ZFHX4 variant and 16q24.1 deletion in a patient with orofacial clefting; a potential role of ZFHX4 and USP10. Am J Med Genet A 2023, 191, (4), 1083-1088. [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Shi, J.; Zhu, Z.; Lu, X.; Jiang, H.; Yu, H.; Liu, H.; Chen, W., CRISPLD1 promotes gastric cancer progression by regulating the Ca(2+)/PI3K-AKT signaling pathway. Heliyon 2024, 10, (5), e27569. [CrossRef]

- Ardizzone, A.; Bova, V.; Casili, G.; Repici, A.; Lanza, M.; Giuffrida, R.; Colarossi, C.; Mare, M.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Esposito, E.; Paterniti, I., Role of Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor in Cancer: Biological Activity, Targeted Therapies, and Prognostic Value. Cells 2023, 12, (7). [CrossRef]

- Hausott, B.; Pircher, L.; Kind, M.; Park, J. W.; Claus, P.; Obexer, P.; Klimaschewski, L., Sprouty2 Regulates Endocytosis and Degradation of Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 1 in Glioblastoma Cells. Cells 2024, 13, (23). [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S. A.; Robertson, S., History of the development of the Confederation of Australian Critical Care Nurses. Confed Aust Crit Care Nurses J 1991, 4, (3), 17. [CrossRef]

- Chang, M. M.; Lai, M. S.; Hong, S. Y.; Pan, B. S.; Huang, H.; Yang, S. H.; Wu, C. C.; Sun, H. S.; Chuang, J. I.; Wang, C. Y.; Huang, B. M., FGF9/FGFR2 increase cell proliferation by activating ERK1/2, Rb/E2F1, and cell cycle pathways in mouse Leydig tumor cells. Cancer Sci 2018, 109, (11), 3503-3518.

- Rice, R.; Spencer-Dene, B.; Connor, E. C.; Gritli-Linde, A.; McMahon, A. P.; Dickson, C.; Thesleff, I.; Rice, D. P., Disruption of Fgf10/Fgfr2b-coordinated epithelial-mesenchymal interactions causes cleft palate. J Clin Invest 2004, 113, (12), 1692-700.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).