1. Introduction

Adult stem cells reside within specialized niche microenvironments that critically govern their tissue regeneration trajectories in response to microenvironmental dynamics [

1,

2]. The sutural tissue located at the interfaces of the facial and mandibular bones is frequently subjected to diverse biological and physical stimuli, which collectively drive microenvironmental remodeling through ECM reorganization and cellular mechanotransduction [

3]. At this critical stage, stem cells detach from their microenvironment and migrate to the leading edge of the tissue, entering a state of lineage plasticity. During this phase, they simultaneously maintain their original cellular identity while acquiring the potential to differentiate into new cellular lineages. The precise regulation of this fate transition is essential for effective tissue repair [

4].

We utilize the technique of trans-sutural distraction osteogenesis (TSDO) to correct midfacial hypoplasia in pediatric patients with cleft lip and palate [

5]. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) residing within the sutural tissue at the craniofacial bone junctions function as the primary cellular responders, initiating new bone formation in response to mechanical traction. These MSCs undergo a transition into a state of lineage plasticity, subsequently differentiating into functional osteoblasts [

6,

7]. However, this therapeutic approach presents several clinical limitations, including the requirement for extended traction periods, compromised patient compliance due to discomfort, and significantly prolonged overall treatment durations [

8].

Consequently, there exists an urgent clinical need to elucidate the molecular mechanisms governing stem cell lineage plasticity under mechanical traction conditions. Although the critical role of MSC lineage plasticity in bone regeneration has gained increasing recognition, the precise signaling pathways and molecular cascades underlying this process remain incompletely understood. Extensive research has demonstrated that the primary cellular response to mechanical stimulation is characterized by the rapid activation of mechanosensitive ion channels, triggering a subsequent influx of calcium ions (Ca²⁺) into the cytoplasm [

9,

10]. External microenvironmental factors are known to activate mechanosensitive ion channels, specifically Piezo1 and

Piezo2, which in turn induce calcium ion influx [

11]. The cytoplasmic calcium ion concentration is recognized as a modulator of MSCs differentiation [

12,

13]. A sustained increase in intracellular calcium ion (Ca²⁺) concentration initiates the activation of multiple mechanotransduction pathways critical for osteogenic differentiation, including but not limited to the Hedgehog (Hh), Wnt, Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP), Notch, and Hippo signaling cascades [

14,

15].

Accumulating evidence from recent studies has demonstrated that retinoic acid (RA), the biologically active metabolite of vitamin A, plays a pivotal role in regulating stem cell lineage plasticity [

4]. RA promotes osteogenic differentiation in vitro by upregulates the expression of a variety of genes related to osteogenesis in different cell types [

16,

17,

18,

19]. RA has been shown to play a crucial regulatory role in physiological bone remodeling processes [

20]. In vitro experimental studies have consistently demonstrated that physiologically relevant concentrations of RA promote osteogenic activity, enhancing both bone formation and osteoblast differentiation [

21]. Exogenous RA treatment increases the expression of

Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 (

BMP-2) and facilitates fracture healing [

9,

10]. The RA and BMP signaling pathway cooperate in the regulation of osteogenic process [

19,

22]. RA also regulates ALP, which hydrolyzes pyrophosphate and generates inorganic phosphate for the proper mineralization of cartilage and bone [

23,

24].

The precise molecular mechanism through which RA induces osteogenic differentiation in cranial suture-derived MSCs remains to be fully elucidated. To investigate this mechanism, we conducted a series of in vitro mechanical stretch experiments using suture-derived MSCs, comparing RA-supplemented and non-supplemented conditions. Transcriptomic analysis revealed that RA significantly upregulates key osteogenic markers in murine MSCs, suggesting a synergistic effect between RA signaling and mechanical stimulation on osteogenic differentiation. Notably, our transcriptomic profiling identified Piezo2, a mechanosensitive ion channel, as a significantly differentially expressed gene. This finding was consistently validated through both in vitro mechanostimulation assays and in vivo RA-treated murine models. To further elucidate the functional role of Piezo2, we performed genetic knockout experiments in MSCs followed by mechanical stretching under osteogenic induction conditions. Quantitative analysis demonstrated a significant enhancement (p<0.01) in calcium nodule formation in RA-treated groups compared to controls. Collectively, these findings provide compelling evidence that RA potentiates mechanical strain-induced osteogenic differentiation through a Piezo2-mediated mechanism.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Model for Surgical Procedures

Four-week-old male C57BL/6J mice (n = 3 per group) were randomly allocated into three experimental groups: (1) sham control, (2) distraction osteogenesis (DO), and (3) DO with RA treatment. A custom-designed W-shaped nickel-titanium alloy distractor (diameter = 0.25 mm; spring constant = 4.3 N/mm, Beijing NiTi Nuo Technology Co., Ltd, China) was surgically implanted to deliver continuous traction force (30 g) at 7 mm compression. The anterior fixation point was anchored at the medial zygomatic arch margin, while the posterior end was secured in a 0.3 mm diameter drill hole posterior to the zygomatic arch. Sham controls underwent identical surgical procedures without distractor placement. For RA treatment, 50 µL of all-trans retinoic acid (10 µM in DMSO/sterile PBS) was administered intraoperatively into the distraction gap and subsequently every 72 hours until sacrifice at postoperative day 7.

2.2. Suture MSCs Isolation and Culture

Zygomaticomaxillary sutures were excised from C57BL/6J female mice and cut into tissue blocks about 5 mm in diameter. The tissue blocks were spread in a culture flask and cultured at 37°C under 5% CO2 conditions with complete culture medium (high-glucose DMEM, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin). After cells reached 70-80% confluence, they were digested with 0.25% trypsin and passaged for further cultivation. Experiments were conducted with cells at passage 3-6.

2.3. Cell Proliferation Assay

MSCs were plated in 96-well culture plates at a density of 3 × 10³ cells/well (200 μL/well) and maintained in DMEM-High glucose medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C in a 5% CO₂ humidified incubator. Cellular morphology and confluency were monitored every 3 hours for 72 hours using the IncuCyte® Live-Cell Analysis System (Sartorius, Germany), with phase-contrast images acquired at 10× magnification.

2.4. Immunofluorescence

Following in vitro cell traction, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton-X-100 (Beyotime, China) for 15 minutes. Cells were blocked with 1% BSA (Beyotime, China) for 30 minutes, then incubated with the primary antibody overnight at 4℃. Subsequently, samples were incubated with the secondary antibody for 1.5 hours at 37℃ in the dark, and nuclei were stained with DAPI for 15 minutes. Images were captured by Zeiss confocal microscopes. The following antibodies were used in our study: Piezo2 (1:200; Invitrogen, USA), goat anti-mouse IgG (1:200; Abcam, UK), and anti-rabbit IgG (1:200; CST, USA).

2.5. Tissue Histology

Zygomatic arches from C57BL/6 mice were isolated and fixed overnight at room temperature in 4% paraformaldehyde (Solarbio, China), followed by a 14-day decalcification process in 0.5 M EDTA (Servicebio, China). After being decalcified, the samples were embedded in paraffin and sliced sagittally to a thickness of 5 mm. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Masson’s trichrome staining were conducted following standard procedures.

Immunohistochemical staining was performed using an anti-Piezo2 antibody(1:200; Invitrogen, USA). After dewaxing and rehydration, paraffin sections were incubated with the primary antibody overnight at 4℃. Subsequently, the sections were incubated with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (ZSGB-bio, China) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Diaminobenzidine (DAB) reagent (ZSGB-bio, China) was applied for 1 minute. Nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin for 30 seconds.

2.6. Lentiviral Transduction

Lentiviral solutions, which include the HBLV-h-Piezo-3xflag plasmid and a Piezo -specific shRNA plasmid with puromycin resistance and GFP fluorescence, were obtained from Beijing MIJIA Scientific, Inc. China. MSCs were seeded in 6-well plates and incubated overnight, Once the cell density reached 50%, the cells were infected with a lentiviral solution mixed with half the original medium volume of the complete medium. After 6 hours, the complete medium was changed and a new complete medium was introduced after 24 hours. GFP fluorescence intensity was checked after 48 to 72 hours. RNA was harvested at 72 hours post-transfection for RT-qPCR analysis to evaluate the efficiency of gene knockdown.

2.7. Micro-Computed Tomography (Micro-CT) Imaging

The skulls from animals were obtained, fixed in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution, and scanned in a coronal orientation using high-resolution microCT (Quantum GX, PerkinElmer). The bone structural parameters were analyzed using the system in the Micro-CT machine. Three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction and morphological measurement were performed by Mimics 21.0 (Materialise, Belgium).

2.8. Flow Cytometry Analysis

Cells were resuspended in flow cytometry buffer (1×PBS containing 0.1% BSA) to a cell concentration of 3×105/ml. A total of 100 µL of cell suspension was taken, and 2 µL of primary antibody was added. The cells were incubated at 4 °C for 30 minutes. Subsequently, the cells were washed with 200 µL flow cytometry buffer, centrifuged at 250 g for 5 minutes, and the supernatant was discarded. Cells were then incubated with 2 µL of fluorescent secondary antibody against the primary antibody at 4 °C for 30 minutes. After resuspending the cells in 300~500 µL flow cytometry buffer, they were analyzed by the FACS Calibur cytometer (BD Biosciences). FlowJo V7.6.2 software was used to assess the MSCs.

2.9. Stem Cell Osteogenic, Adipogenic, and Chondrogenic Differentiation

MSCs in logarithmic phase were plated at 2×10⁴ cells/cm² and cultured to 70% confluence (37°C, 5% CO2). Osteogenic differentiation was induced using specific medium (

Table S1), refreshed every 2 days for 21 days. Cells were then fixed (4% formaldehyde, 30 min) and stained with Alizarin Red.(Sigma, USA). For chondrogenic differentiation, following similar protocol, cells were stained with Alcian blue. Adipogenic differentiation involved 1-day maintenance medium followed by 3-day induction medium, with Oil Red O staining after 21 days.

2.10. In vitro Stretching and RA Treatment of MSCs

MSCs were cultured at a density of 2 × 104 cells/cm² per well with type I rat tail collagen for 24 hours. When cells reached 50% confluence, mechanical stretching CELL TANK (Dongdi Beijing Technology Co., Ltd, China) was applied at a frequency of 1Hz with a cyclic elongation of 8% for 2 hours and 3 days (6 hours per day) with or without 1 µM RA (Sigma).

2.11. Analysis of mRNA Expression for Bone-Related Genes

Total RNA was extracted from MSCs by Trizol (Tiangen, China) and transcribed into cDNA through M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Vazyme). Real-time qPCR reactions were performed in 20 µL volumes containing 10 µL SYBR Green PCR Max Mix (Yeasen), 0.7 µM forward and reverse primers (

Table S2), 1 µL cDNA, and RNase-free water. Reactions were carried out on the real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad) with an amplification profile: 95°C for 5 min, 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 60°C for 15 s. Primers for target genes were listed in Table 2. Relative gene expression was normalized to the housekeeping gene

GAPDH. After calculation of ΔC

T (C

T, gene of interest - C

T, GAPDH), the relative expression level was calculated as 2

-ΔCT. The 2

-ΔCT value of static group was set to 1 for normalization. The experiment was conducted using three independent biological replicates.

2.12. RNA-Seq Analysis

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol and sequencing was conducted on three independent biological replicates. The libraries were sequenced on an Illunima nova 6000 and 150 bp paired-end reads were generated. For RNA-seq data analysis, the sequencing quality was evaluated using FastQC (v.0.11.9). Then reads were mapped to the Mouse genome (GRCm39) using HISAT2(v.2.2.0) with default parameters. The read numbers of individual genes were counted using FeatureCounts software (v.2.0.1). Transcripts Per Million (TPM) of each gene was calculated using an in-house R script. The differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2 (v.1.30.0 R package). P value < 0.05 and log2 (Fold Change) > 1 or log2 (Fold Change) < -1 were set as the threshold for significantly differential expression. GO cluster analysis was performed using clusterProfiler v4.2.2. TBtools was used to perform the heatmap of differential expression genes.

2.13. Statistical Analysis

The data sets were analyzed by GraphPad Prism 9.0 software. The student's t-test were used for difference significance test between two samples.

3. Results

3.1. RA Promoted the Bone Formation of Zygomaticomaxillary Suture in Mice Under Mechanical Traction

To assess osteogenesis resulting from mechanical stimulation, a stretching procedure was performed on 4-week-old mice to apply a sagittal distraction force in the zygomaticomaxillary suture (

Figure 1A). Mirco-CT showed that the ZMS was significantly wider than the control group on the 3 days (

Figure 1B). After a 3-day distraction, H&E staining indicated a notable increase in the bone suture width and visible cell proliferation, yet no new bone was formed. After stretching for 14 days, new bone formation was noticeable in the suture margins, with a partial restoration of the suture width. The cells in the suture showed elongation towards the direction of the applied force, and the boundaries of the bone appeared less distinct (

Figure 1C).

RA-treated group were wider than that of the distraction group. At the 14 days of traction, the bone suture in the traction group was significantly wider than that in the control group, with a large proliferation of cells, fusion of new bone along the osteogenic front, and the formation of a hump-shaped bony projection (

Figure 1C).

To further investigate the role of mechanical traction on bone formation in the ZMS of mice in an in vivo setting, we performed Masson staining on tissue sections. Masson staining showed that, the synthesis of collagen fibers increased significantly in 14 days after distraction with RA group, and the synthesis of new bone fused with new bone along the front edge of the osteogenic bone in the RA-treated group, synthesized significantly more collagen fibers, bone thickening, and new bone formation (

Figure 1D). Mirco-CT imaging also corroborated this observation, revealing that the incorporation of RA treatment in the distraction group led to a significantly wider suture compared to the group that underwent distraction alone.

3.2. Uniaxial Cyclic Stretch (UCS) Induces MSCs Reorientation and Promotes the Expression of Osteogenic-Related Genes

We incorporated tissue blocks into hydrogel and isolated MSCs from the zygomaticomaxillary sutures of mice, and then verified the stem cell properties and differentiation capacity. Flow cytometry analysis of the zygomaticomaxillary suture cells revealed positive expression of MSC markers such as SCA1, CD29, CD90.2, and CD44, and negative markers of CD34, CD31, and CD117 (

Figure 2A). The cells showcased the ability to differentiate into osteogenic, adipogenic, and chondrogenic lineages (

Figure 2B)

. The cells exhibit self-stability under in vitro culture conditions, with the cell proliferation curve displaying a distinct logarithmic phase and plateau phase (

Figure 2C,D). These results substantiate that MSCs exist in zygomaticomaxillary sutures with the ability of multiple differentiation potential.

MSCs derived from mice were cultured on type I collagen-coated tensile substrates for 24 hours before mechanical stretching. The stretching device is depicted in

Figure 3A and 3B. Cells adhered well to collagen and spread extensively. The distribution of MSCs that were not subjected to stretching was random. However, the cells exhibited a perpendicular orientation to the direction of stretch under 1Hz frequency and 8% strain stretching (

Figure 3C). .

To eliminate the potential impact of Type I collagen on MSC differentiation, we assessed the expression of marker genes in MSCs cultured on polystyrene dishes and stretching dishes using RT-qPCR. After confirming there is no significant differences in gene expression, UCS (8% strain and 1Hz stretching frequency) was applied to MSCs cultured on stretching dishes for indicated times. Real time PCR analysis showed that the relative expression levels of

BMP2 and

COL1 were significantly induced by 2 and 4 hours of stretching. Consistently, the relative expression levels of

COL1,

ALP, and

OCN were also increased under 3 days of stretching (

Figure 3D). These results suggest that mechanical stretching positively regulates core osteogenic transcription factors to promote ossification in MSCs.

These results indicate that tension promotes osteogenic differentiation in vitro in a time-dependent manner, with the effects becoming significantly more evident at 2 hours and 3 days. Therefore, 2 hours and 3 days were selected as the time point for further studies.

3.3. Analyses of Differentially Expressed Genes During RA and Mechanical Stretching Treatment

To identify the responsive genes of MSCs to mechanical stretching and RA, RNA-seq analysis was employed in MSCs subjected to 0, 2 hours or 3 days of in vitro stretching with or without 1 µM RA treatment. 20 million reads were acquired per sample, and over 90% of these reads could be mapped to the mice genome (GRCm39). We identified 28340 expressed genes that were expressed in at least one of the 17 samples (Table. S3). PCA showed that 17 samples subject to different treatments could be well divided into 6 categories (

Figure S1A).

DEGs were identified based on the selection criteria Log

2(|Fold Change|) ≥1 and adj

p value<0.05. A total of 127 and 503 genes showed differential expression in the 2 hour and 3 days samples respectively when compared to non-stretch samples (

Figure S1B). Subsequently, Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis revealed that these DEGs significantly enriched in biological processes such as “extracellular matrix formation”, “vascular endothelial growth factor production”, “regulation of vasculature development”, “blood vessel development”, “regulation of angiogenesis”, “hormone transport”, and “regulation of macrophage migration” (

Figure 4A and

Figure S1C).

Furthermore, DEGs in groups treated with RA and stretching vs. groups subjected to stretching without RA were analyzed. The results showed that there were 1779 and 2158 DEGs in the 2 hours and 3 days samples respectively (

Figure 4E, F and

Table S3). Further analysis using GO enrichment revealed that DEGs significantly concentrate on the biological process “ossification”, “negative regulation of locomotion”, “cell-substrate adhesion”, “amoeboidal-type cell migration”, “epithelial cell proliferation”, “positive regulation of cell adhesion”, “external encapsulating structure organization”, and “extracellular structure organization”, which related to extracellular matrix alterations and osteogenic differentiation (

Figure 4B,C). These findings suggest that RA plays an active role in the stretching process.

3.4. RNA-seq Demonstrate That RA Induces Osteogenesis of MSCs via the TGFβ/BMP and WNT Signaling Pathways, as Well as Through the Activation of the Piezo2 Gene

Heatmap showed that the expression of

Retinoic Acid Receptor γ (

RARγ),

RARβ, and RA metabolism-related genes

CYP26s significantly increased during RA and stretching co-treatment, demonstrating the RA is effective in this experiment (

Figure 4D). Genes of TGFβ/BMP and WNT signaling pathways, which participate in ossification, were significantly upregulated by RA and stretching co-treatment (

Figure 4D).

Piezo1 and

Piezo2, two highly homologous mechanosensitive ion channel proteins, serve as essential mechanotransducers in bone biology [

25,

26]. These channels function as primary mechanosensitive signal receptors, responding to mechanical stimuli by undergoing conformational changes that permit calcium ion (Ca²⁺) influx, thereby initiating downstream signaling cascades [

27,

28]. Emerging evidence suggests that Piezo channels play a pivotal role in skeletal development and the maintenance of bone homeostasis through mechanotransduction pathways [

29]. At the 2-hour and 3-day time points, volcano plots were generated to compare the stretch+RA treatment group with the pure mechanical stretch group. The results indicated that the expression of the

Piezo2 gene was significantly upregulated in the RA treatment group, with statistically significant differences observed (

Figure 4E and F). Consistently, the relative expression levels of

Piezo2 were also increased under stretching with RA in different time (

Figure 4G).

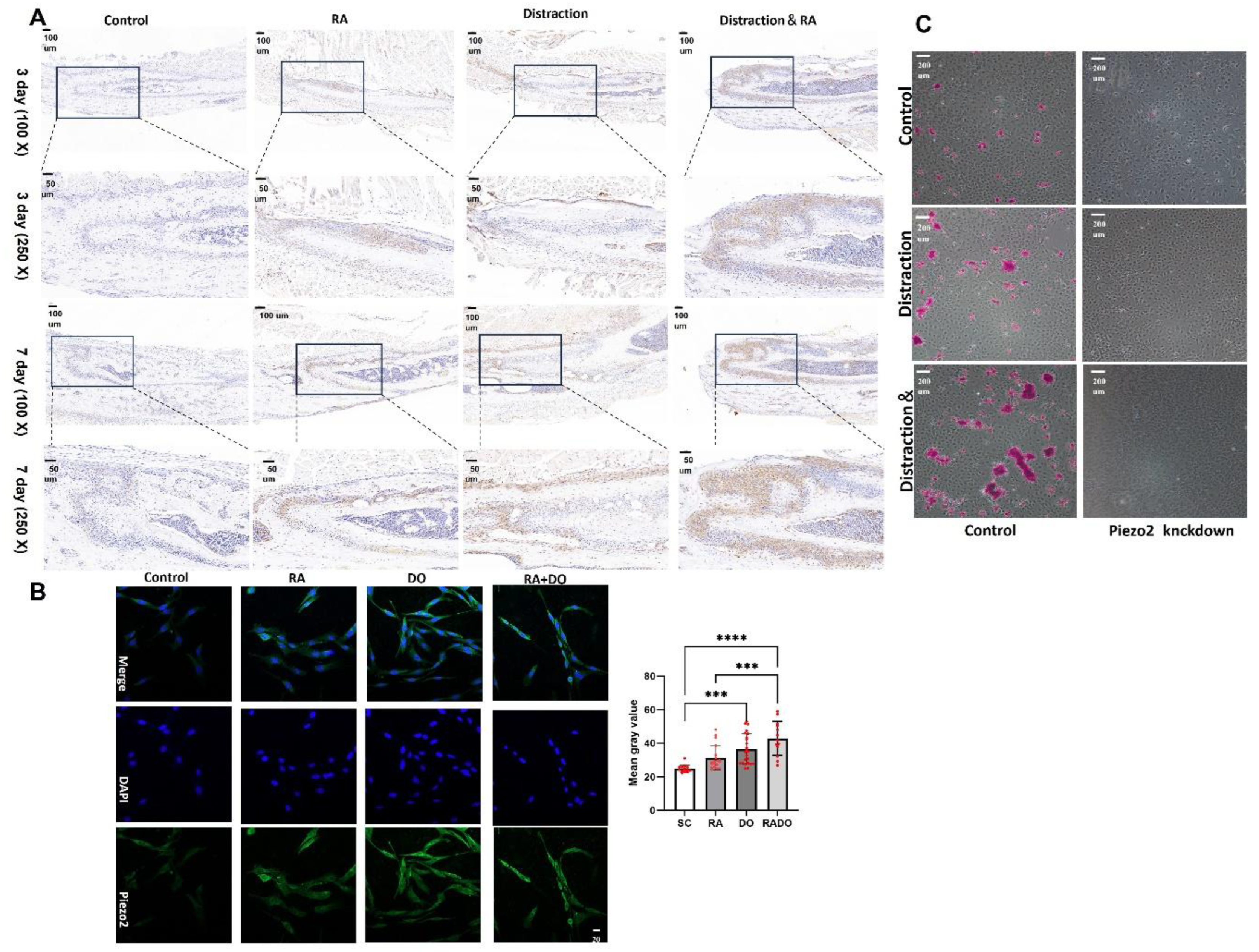

3.5. RA Regulate Distraction Osteogenesis Through Piezo2

Based on the cellular transcriptomic data, Piezo2 was identified as a significantly differentially expressed gene, which was confirmed by RT-PCR. The experimental results indicated that both RA and distraction can promote the growth and differentiation of suture tissue into bone, and both can upregulate Piezo2 expression. Therefore, we propose the hypothesis that RA may regulate distraction osteogenesis through Piezo2.

The immunohistochemical staining results of the mouse ZMS tissue suggest that on day 3 and day 7, the expression of

Piezo2 in the sutures of mice treated with RA alone and subjected to distraction alone was increased compared to the untreated control group. In the sutures of mice subjected to both RA treatment and distraction, the expression of

Piezo2 was significantly higher than that in the groups treated with RA alone and subjected to distraction alone (

Figure 5A).

Consistent results were observed in in vivo cell experiments. After 3 days in vitro cell stretching, immunofluorescence analysis indicated a significant upregulation of

Piezo2 expression following distraction(P<0.01). Notably, the group that underwent both distraction and RA treatment exhibited a markedly higher

Piezo2 expression compared to both the control and the RA treatment alone groups (

Figure 5B).

We transfected MSCs with shRNA targeting

Piezo2 to construct a mutant with

Piezo2 knockdown. Under the influence of osteogenic induction medium, we subjected the cells to in vitro stretching for 18 days, followed by Alizarin Red staining to assess calcium salt deposition, which indicates the osteogenic differentiation capacity of the cells. The results revealed that MSCs with

Piezo2 knockdown exhibited a significant decrease in osteogenic differentiation ability, with no evident calcium salt deposition observed. In contrast, in MSCs without

Piezo2 knockdown, the group subjected to both drug treatment and mechanical stretching showed a markedly higher amount of calcium salt deposition compared to the group subjected to stretching alone (

Figure 5C).

4. Discussion

4.1. Cell Realignment in UCS Promote Osteogenic Genes Expression

Extensive studies have established that mechanical stimuli profoundly regulate fundamental cellular processes, including focal adhesion dynamics, cytoskeletal reorganization, cell cycle progression and lineage commitment [

30,

31,

32]. Cell morphology studies have demonstrated that MSCs reorient themselves in response to a critical stretch magnitude. UCS was found to enhance cellular anisotropy and alignment, which is regarded as a potential adaptive mechanism for stress avoidance. [

32,

33]. Cells remodel their actin filaments to reorient and adjust the direction of stress in response to external stretching. This remodeling ensures mechanical homeostasis by aligning the cells along the directions of minimal substrate deformation [

34]. DEGs induced by RA and stretching co-treatment also enriched in “cell–substrate adhesion” biological process (

Figure 4B,C). External mechanical forces influence nuclear morphology and chromatin organization through cytoskeletal remodeling [

35]. Furthermore, emerging evidence suggests that mechanical signals transmitted to the nucleus can trigger diverse gene expression profiles and modulate the activity of transcription factors [

36]. Mechanical traction serves as a potent stimulus for osteogenic differentiation in MSCs. However, this process is time-consuming and requires further optimization to enhance its efficiency.

4.2. RA Induces Osteogenesis in MSCs

RA plays a pivotal role in regulating cellular processes, including differentiation, proliferation, migration, and inflammation [

37]. In this study, we evaluated the expression levels of genes involved in the retinoid signaling pathway to confirm the activation of RA signaling [

38]. As expected, these genes were significantly upregulated in MSCs treated with RA (

Figure 4D). Previous studies have demonstrated that the expression of the key osteogenic gene ALP can be directly regulated by RA through its regulatory region, the retinoic acid response element (RARE), in the SaOS-2 osteosarcoma cell line [

39]. Similarly,

BMP2 gene activated by RA to promote osteogenic differentiation in human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [

34]. In this study, the expression of ALP and BMP2, both of which are induced by mechanical stretching, was significantly increased in samples co-treated with RA and stretching, suggesting a synergistic effect that may direct MSCs toward osteogenic differentiation. However, contrasting results have been reported in rat bone marrow-derived MSCs, where RA and BMP signaling were found to promote adipogenesis while suppressing osteogenesis [

40]. These findings indicate that the osteogenic effects of RA may be cell type-specific and dose-dependent.

The TGFβ/BMP and WNT signaling pathways play crucial roles in the development of the mammalian craniofacial region [

15], and are known to facilitate osteogenic differentiation [

41,

42]. However, it has been demonstrated that the function of RA cannot be substituted by TGFβ/BMP and/or WNT signaling, suggesting that RA acts as a direct regulator of osteogenesis independent of these pathways [

43]. In this study, we observed that RA significantly enhanced the activation of TGFβ/BMP and WNT signaling pathways under mechanical stretching (

Figure 4D), indicating that low-dose RA may promote osteogenic differentiation of MSCs through these pathways. We propose that RA could serve as a novel approach to enhancing osteogenic differentiation of MSCs under mechanical stimulation. Additionally, our in vitro mechanical stretching system provides an efficient platform for drug screening related to craniofacial suture ossification. This system is designed to operate on a smaller scale, achieve results in shorter time frames, and maintain high reproducibility.

Piezo1 and

Piezo2 are two highly homologous mechanosensitive ion channel proteins that serve as critical mechanosensors in cellular responses to mechanical stimuli [

25]. These proteins function as mechanosensitive signal receptors by opening their channels in response to mechanical stimulation, permitting calcium influx into cells and subsequently activating downstream signaling pathways [

44]. Piezo channels play an essential role in skeletal development and the maintenance of bone homeostasis under mechanical stimulation [

45]. Recent studies utilizing clinical samples and mouse models have demonstrated that Piezo1 is a key regulator of skeletal development and bone remodeling [

46,

47]. However, these studies have primarily focused on long bones, which undergo endochondral ossification [

48]. In contrast, the intramembranous ossification process characteristic of craniofacial bones [

49], t has been less extensively studied. Researchers have identified

Piezo2-expressing mesenchymal cells within the midpalatal suture and its surrounding regions. These

Piezo2-positive cells detect mechanical expansion and activate signaling factors involved in osteogenesis [

50,

51]. The bone surrounding the midpalatal suture exhibits the capacity to grow and remodel in response to mechanical strain [

52]. Similarly, in periodontal stem cells, which share a common cranial neural crest origin,

Piezo2 activation modulates the WNT signaling pathway, thereby regulating the proliferation and differentiation of progenitor cells [

53].

5. Conclusions

We demonstrated that stretching in vitro induce the expression of osteogenic-related transcription factors, including BMP2, ALP, OCN, and COL1, in MSCs isolated from zygomaticomaxillary sutures in mouse. Genes regulated by RA and mechanical stretching significantly involved in extracellular matrix alterations and osteogenic differentiation. Mirco-CT showed that the width of zygomaticomaxillary suture in mice was increased after local application of RA compared with simple stretching. Simultaneously, RA cooperate with mechanical stretching to activate TGF-β/BMP and WNT signaling pathways, thus promoting osteogenesis. Compared to the mechanical stretching-only group, Piezo2 was identified as a significantly differentially expressed gene in the group treated with both mechanical stretching and RA. This finding was validated through both in vitro cell experiments and in vivo animal studies. Furthermore, knockout of Piezo2 resulted in a marked reduction in the ability of MSCs to form calcium nodules under mechanical tension. These results indicate that RA putatively promotes osteogenic differentiation under mechanical stretching via Piezo2.

Supplementary Data

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

All authors made contributions to methodology, data curation, data visualization, and analysis of data; All the above authors approved the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Funder of China (No. 81571925).

Data Availability Statement

The RNA-seq data that support the findings of this study have been submitted to the National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive (

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/) under accession number PRJNA1059283.

Ethics Statement

All of the animal procedures were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Regulations for the care and use of animals.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Hsu, Y.C.; Li, L.S.; Fuchs, E. , Emerging interactions between skin stem cells and their niches. Nature Medicine 2014, 20, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, S.J.; Spradling, A.C. , Stem cells and niches: Mechanisms that promote stem cell maintenance throughout life. Cell 2008, 132, 598–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, W.; Ding, P.B.; Qian, J.Y.; Li, G.; Lu, E.H.; Zhao, Z.M. , Polarized M2 macrophages induced by mechanical stretching modulate bone regeneration of the craniofacial suture for midfacial hypoplasia treatment. Cell and Tissue Research 2021, 386, 585–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tierney, M.T.; Polak, L.; Yang, Y.H.; Abdusselamoglu, M.D.; Baek, I.; Stewart, K.S.; Fuchs, E. Vitamin A resolves lineage plasticity to orchestrate stem cell lineage choices. Science 2024, 383, eadi7342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, H.Z.; Song, T.; Sun, X.M.; Yin, N.B.; Liu, L.; Wang, X.G.; Zhao, Z.M. Imaging study of midface growth with bone-borne trans-sutural distraction osteogenesis therapy in growing cleft lip and palate patients. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, Y.; Fan, Y.; Ouchi, T.; Zhao, Z.; Li, L. , Cranial suture mesenchymal stem cells: Insights and advances. Biomolecules 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruyama, T.; Jeong, J.; Sheu, T.-J.; Hsu, W. , Stem cells of the suture mesenchyme in craniofacial bone development, repair and regeneration. Nature Communications 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, H.; Wang, X.; Song, T.; Gao, F.; Yin, J.; Li, H.; Sun, X.; Wang, Y.; Yin, N.; Zhao, Z. , Trans-sutural distraction osteogenesis for midfacial hypoplasia in growing patients with cleft lip and palate. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 2015, 136, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitching, R.; Qi, S.; Li, V.; Raouf, A.; Vary, C.; Seth, A. , Coordinate gene expression patterns during osteoblast maturation and retinoic acid treatment of MC3T3-E1 cells. Journal of bone and mineral metabolism 2002, 20, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paralkar, V.; Grasser, W.; Mansolf, A.; Baumann, A.; Owen, T.; Smock, S.; Martinovic, S.; Borovecki, F.; Vukicevic, S.; Ke, H.; Thompson, D. , Regulation of BMP-7 expression by retinoic acid and prostaglandin E(2). Journal of cellular physiology 2002, 190, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Ahmad, M.; Perrimon, N. , Mechanosensitive channels and their functions in stem cell differentiation. Experimental cell research 2019, 374, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, T.; Sokabe, M. , Sensing substrate rigidity by mechanosensitive ion channels with stress fibers and focal adhesions. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 2010, 22, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Liu, Y.; Lipsky, S.; Cho, M. , Physical manipulation of calcium oscillations facilitates osteodifferentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Faseb Journal 2007, 21, 1472–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Zhao, E.; Li, G.; Bi, H.; Zhao, Z. , Suture Cells in a Mechanical Stretching Niche: Critical Contributors to Trans-sutural Distraction Osteogenesis. Calcified Tissue International 2021, 110, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, A.; Sangani, D.R.; Ansari, A.; Iwata, J. , Molecular mechanisms of midfacial developmental defects. Developmental Dynamics 2015, 245, 276–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, A.; Hoffman, L.; Underhill, T. , Revisiting the role of retinoid signaling in skeletal development, Birth defects research. Part C, Embryo today : reviews 2003, 69, 156–173. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.M.; Nacamuli, R.P.; Xia, W.; Bari, A.S.; Shi, Y.Y.; Fang, T.D.; Longaker, M.T. , High-dose retinoic acid modulates rat calvarial osteoblast biology. Journal of Cellular Physiology 2004, 202, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malladi, P.; Xu, Y.; Yang, G.; Longaker, M. , Functions of vitamin D, retinoic acid, and dexamethasone in mouse adipose-derived mesenchymal cells. Tissue engineering 2006, 12, 2031–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, D.; Shi, Y.; Nacamuli, R.; Quarto, N.; Lyons, K.; Longaker, M. , Osteogenic differentiation of mouse adipose-derived adult stromal cells requires retinoic acid and bone morphogenetic protein receptor type IB signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2006, 103, 12335–12340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaëlsson, K.; Lithell, H.; Vessby, B.; Melhus, H. , Serum retinol levels and the risk of fracture. The New England journal of medicine 2003, 348, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, S.; Nagy, J.; Sullivan, K.; Thomas, K.; Endo, N.; Rodan, G.; Rodan, S. , Induction of vascular endothelial growth factor expression by prostaglandin E2 and E1 in osteoblasts. The Journal of clinical investigation 1994, 93, 2490–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helvering, L.; Sharp, R.; Ou, X.; Geiser, A. , Regulation of the promoters for the human bone morphogenetic protein 2 and 4 genes. Gene 2000, 256, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prins, H.J.; Braat, A.K.; Gawlitta, D.; Dhert, W.J.A.; Egan, D.A.; Tijssen-Slump, E.; Yuan, H.P.; Coffer, P.J.; Rozemuller, H.; Martens, A.C. , In vitro induction of alkaline phosphatase levels predicts in vivo bone forming capacity of human bone marrow stromal cells. 12Stem Cell Research 2014, 12, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira-Baptista, C.; Queirós, A.; Ferreira, R.; Fernandes, M.H.; Gomes, P.S.; Colaço, B. , Retinoic acid induces the osteogenic differentiation of cat adipose tissue-derived stromal cells from distinct anatomical sites. Journal of Anatomy 2023, 242, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coste, B.; Mathur, J.; Schmidt, M.; Earley, T.J.; Ranade, S.; Petrus, M.J.; Dubin, A.E.; Patapoutian, A. , Piezo1 and Piezo2 Are Essential Components of Distinct Mechanically Activated Cation Channels. Science 2010, 330, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Knutson, K.; Alcaino, C.; Linden, D.R.; Gibbons, S.J.; Kashyap, P.; Grover, M.; Oeckler, R.; Gottlieb, P.A.; Li, H.J.; Leiter, A.B.; Farrugia, G.; Beyder, A. , Mechanosensitive ion channel Piezo2 is important for enterochromaffin cell response to mechanical forces. Journal of Physiology-London 2017, 595, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hou, B.; Tumova, S.; Muraki, K.; Bruns, A.; Ludlow, M.J.; Sedo, A.; Hyman, A.J.; McKeown, L.; Young, R.S.; Yuldasheva, N.Y.; Majeed, Y.; Wilson, L.A.; Rode, B.; Bailey, M.A.; Kim, H.R.; Fu, Z.J.; Carter, D.A.L.; Bilton, J.; Imrie, H.; Ajuh, P.; Dear, T.N.; Cubbon, R.M.; Kearney, M.T.; Prasad, K.R.; Evans, P.C.; Ainscough, J.F.X.; Beech, D.J. , Piezol integration of vascular architecture with physiological force. Nature 2014, 515, 279-U308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, M.M.; Nourse, J.L.; Tran, T.; Hwe, J.; Arulmoli, J.; Le, D.T.T.; Bernardis, E.; Flanagan, L.A.; Tombola, F. , Stretch-activated ion channel Piezo1 directs lineage choice in human neural stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2014, 111, 16148–16153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, A.; Miyazaki, A.; Kawarabayashi, K.; Shono, M.; Akazawa, Y.; Hasegawa, T.; Ueda-Yamaguchi, K.; Kitamura, T.; Yoshizaki, K.; Fukumoto, S.; Iwamoto, T. , Piezo type mechanosensitive ion channel component 1 functions as a regulator of the cell fate determination of mesenchymal stem cells. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 17696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, N.; Denecke, B.; Kim, B.; Dreser, A.; Bernhagen, J.; Pallua, N. , The effect of mechanical stress on the proliferation, adipogenic differentiation and gene expression of human adipose-derived stem cells. Journal of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine 2018, 12, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, H.; Pingguan-Murphy, B.; Abbas, A.A.; Merican, A.M.; Kamarul, T. , The proliferation and tenogenic differentiation potential of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cell are influenced by specific uniaxial cyclic tensile loading conditions. Biomechanics and modeling in mechanobiology 2015, 14, 649–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, S.; Buckley, C.; Kelly, D. , Cyclic Tensile Strain Can Play a Role in Directing both Intramembranous and Endochondral Ossification of Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Frontiers in bioengineering and biotechnology 2017, 5, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungbauer, S.; Gao, H.; Spatz, J.; Kemkemer, R. , Two characteristic regimes in frequency-dependent dynamic reorientation of fibroblasts on cyclically stretched substrates. Biophysical journal 2008, 95, 3470–3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, R.; Song, X.Y.; Yan, K.C.; Liang, H.Y. , Uniaxial Cyclic Stretching Promotes Chromatin Accessibility of Gene Loci Associated With Mesenchymal Stem Cells Morphogenesis and Osteogenesis. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2021, 9, 664545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdas, N.; Shivashankar, G. , Cytoskeletal control of nuclear morphology and chromatin organization. Journal of molecular biology 2015, 427, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, T.; Lammerding, J. , Emerging views of the nucleus as a cellular mechanosensor. Nature cell biology 2018, 20, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Yuan, L.; Yang, H.; Zang, A. , transThe mechanism of all- retinoic acid in the regulation of apelin expression in vascular endothelial cells. Bioscience reports 2017, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorgan, T.; Heckt, T.; Rendenbach, C.; Helmis, C.; Seitz, S.; Streichert, T.; Amling, M.; Schinke, T. , Immediate effects of retinoic acid on gene expression in primary murine osteoblasts. Journal of bone and mineral metabolism 2016, 34, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orimo, H.; Shimada, T. , Regulation of the human tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase gene expression by all-trans-retinoic acid in SaOS-2 osteosarcoma cell line. Bone 2005, 36, 866–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Huang, H.; Wang, M.; Wang, A. , Retinoic acid inhibits osteogenic differentiation of mouse embryonic palate mesenchymal cells, Birth defects research. Part A, Clinical and molecular teratology 2010, 88, 965–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.; Kneissel, M. , WNT signaling in bone homeostasis and disease: from human mutations to treatments. Nature medicine 2013, 19, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddi, A. , Role of morphogenetic proteins in skeletal tissue engineering and regeneration. Nature biotechnology 1998, 16, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, S.; Yoshitomi, H.; Sunaga, J.; Alev, C.; Nagata, S.; Nishio, M.; Hada, M.; Koyama, Y.; Uemura, M.; Sekiguchi, K.; Maekawa, H.; Ikeya, M.; Tamaki, S.; Jin, Y.; Harada, Y.; Fukiage, K.; Adachi, T.; Matsuda, S.; Toguchida, J. , In vitro bone-like nodules generated from patient-derived iPSCs recapitulate pathological bone phenotypes. Nature Biomedical Engineering 2019, 3, 558–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coste, B.; Xiao, B.L.; Santos, J.S.; Syeda, R.; Grandl, J.; Spencer, K.S.; Kim, S.E.; Schmidt, M.; Mathur, J.; Dubin, A.E.; Montal, M.; Patapoutian, A. , Piezo proteins are pore-forming subunits of mechanically activated channels. Nature 2012, 483, 176-U172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, L.; Liu, W.; Cao, H.L.; Xiao, G.Z. , Molecular mechanosensors in osteocytes. Bone Research 2020, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.F.; Gao, B.; Fan, Y.; Liu, Y.C.; Feng, S.H.; Cong, Q.; Zhang, X.L.; Zhou, Y.X.; Yadav, P.S.; Lin, J.C.; Wu, N.; Zhao, L.; Huang, D.S.; Zhou, S.H.; Su, P.Q.; Yang, Y.Z. , Piezo1/2 mediate mechanotransduction essential for bone formation through concerted activation of NFAT-YAP1-ss-satenin. Elife 2020, 9, e52779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.J.; You, X.L.; Lotinun, S.; Zhang, L.L.; Wu, N.; Zou, W.G. , Mechanical sensing protein PIEZO1 regulates bone homeostasis via osteoblast-osteoclast crosstalk. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brylka, L.J.; Alimy, A.R.; Tschaffon-Müller, M.E.A.; Jiang, S.; Ballhause, T.M.; Baranowsky, A.; von Kroge, S.; Delsmann, J.; Pawlus, E.; Eghbalian, K.; Püschel, K.; Schoppa, A.; Haffner-Luntzer, M.; Beech, D.J.; Beil, F.T.; Amling, M.; Keller, J.; Ignatius, A.; Yorgan, T.A.; Rolvien, T.; Schinke, T. , Piezo1 expression in chondrocytes controls endochondral ossification and osteoarthritis development. Bone Research 2024, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.X.; Lin, X.X.; Liu, Y.; Greenblatt, M.B.; Xu, R. , Skeletal stem cells in bone development, homeostasis, and disease. Protein & Cell 2024, 15, 559–574. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero-Vargas, J.A.; Silva, T.A.; Macari, S.; de Las Casas, E.B.; Garzón-Alvarado, D.A. , Influence of interdigitation and expander type in the mechanical response of the midpalatal suture during maxillary expansion. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2019, 176, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.S.Y.; Opperman, L.A.; Kyung, H.M.; Buschang, P.H. , Is there an optimal force level for sutural expansion? , American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2011, 139, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; Xu, T.S.; Zhang, L.Q.; Li, Y.C.; Yan, T.X.; Yu, G.X.; Chen, F. , Midpalatal Suture: Single-Cell RNA-Seq Reveals Intramembrane Ossification and Piezo2 Chondrogenic Mesenchymal Cell Involvement. Cells 2022, 11, 3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, F.; Guo, T.; Zhang, M.; Ma, L.; Jing, J.; Feng, J.; Thach, V.H.; Wen, Q.; Chai, Y. , FGF signaling modulates mechanotransduction/WNT signaling in progenitors during tooth root development. Bone Research 2024, 12, 582–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).