Submitted:

07 March 2025

Posted:

11 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

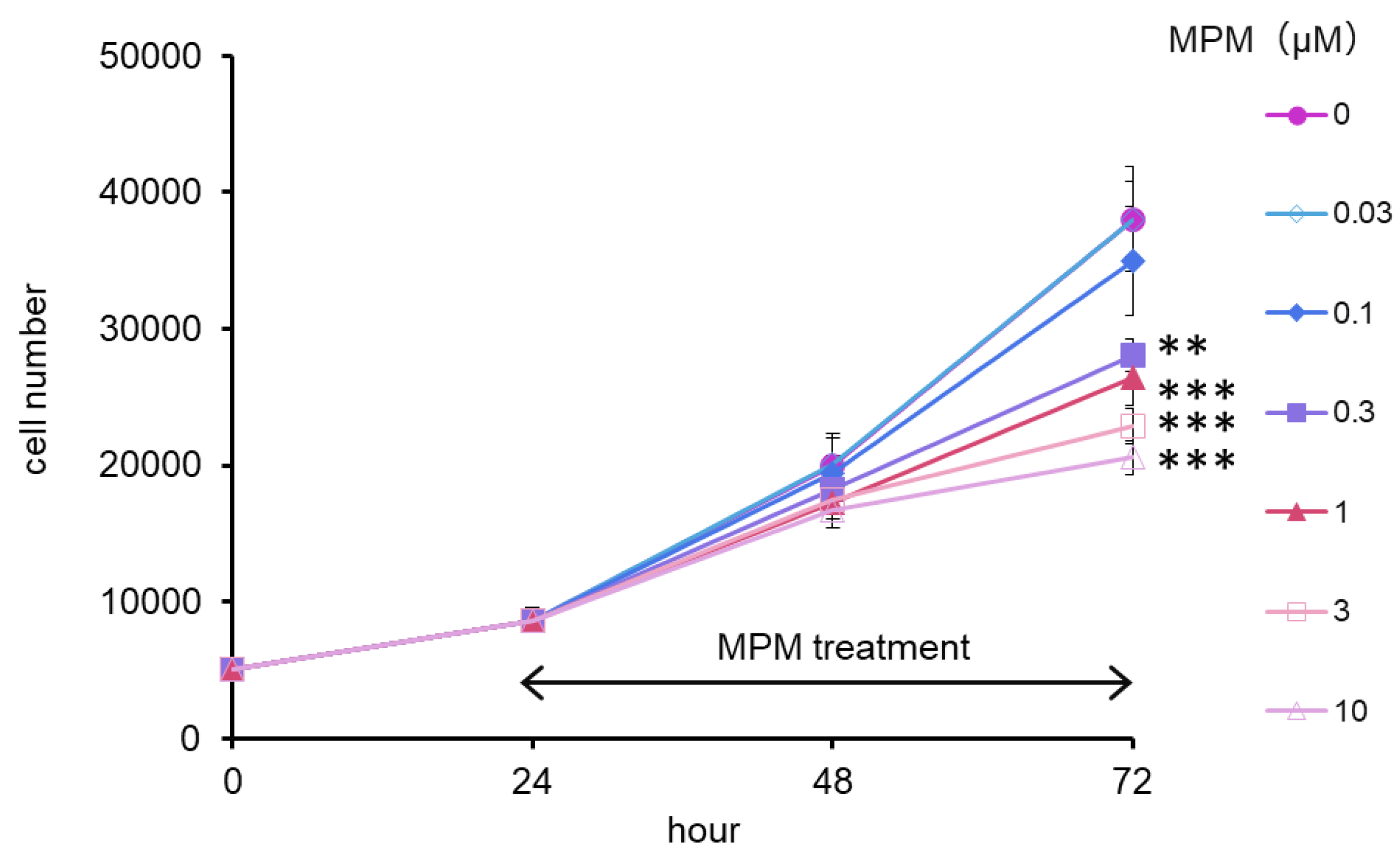

2.1. MPM Inhibited HEPM Cell Proliferation in a Dose- and Time-Dependent Manner

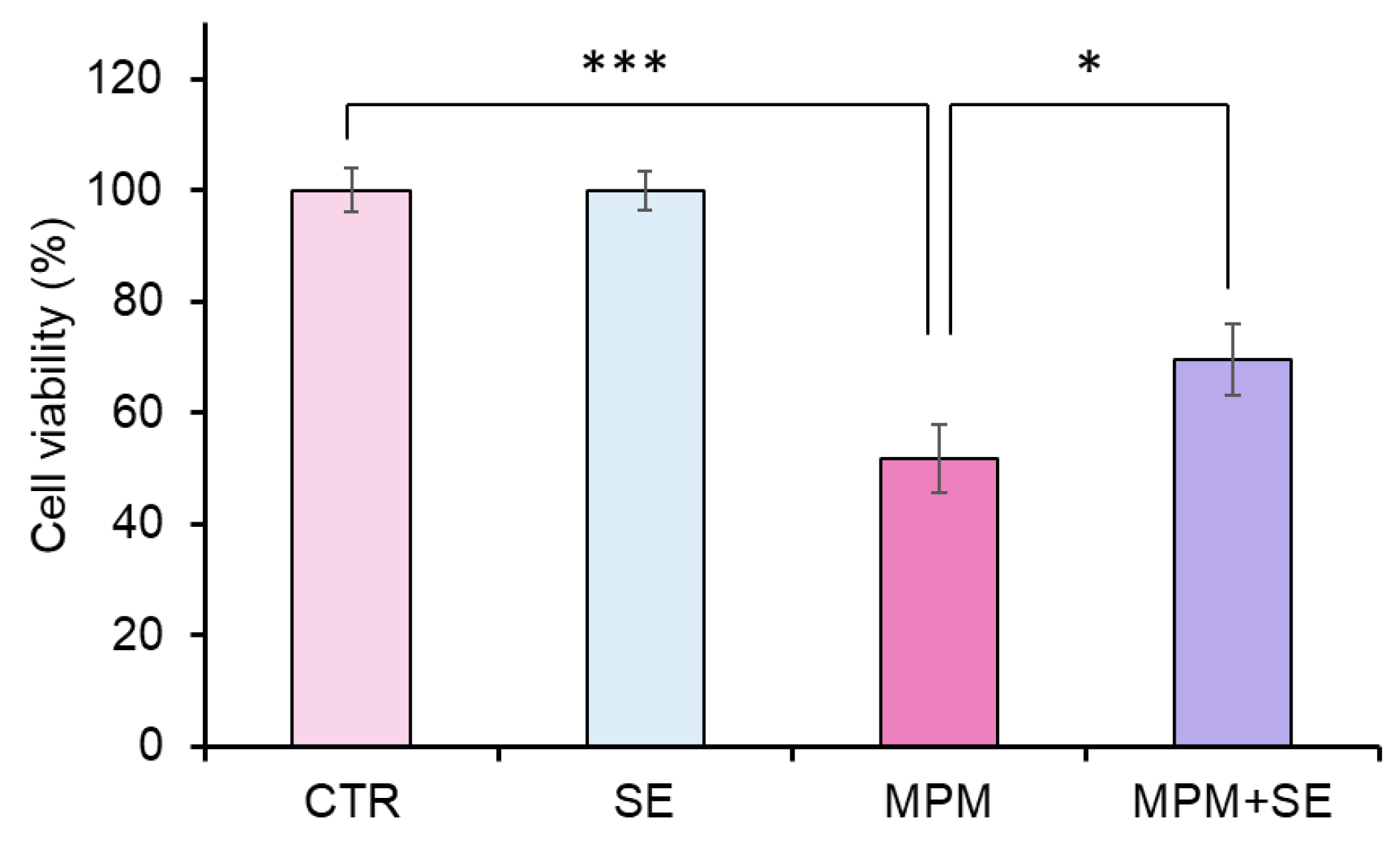

2.2. SE Alleviated MPM-Induced Proliferation Inhibition in HEPM Cells

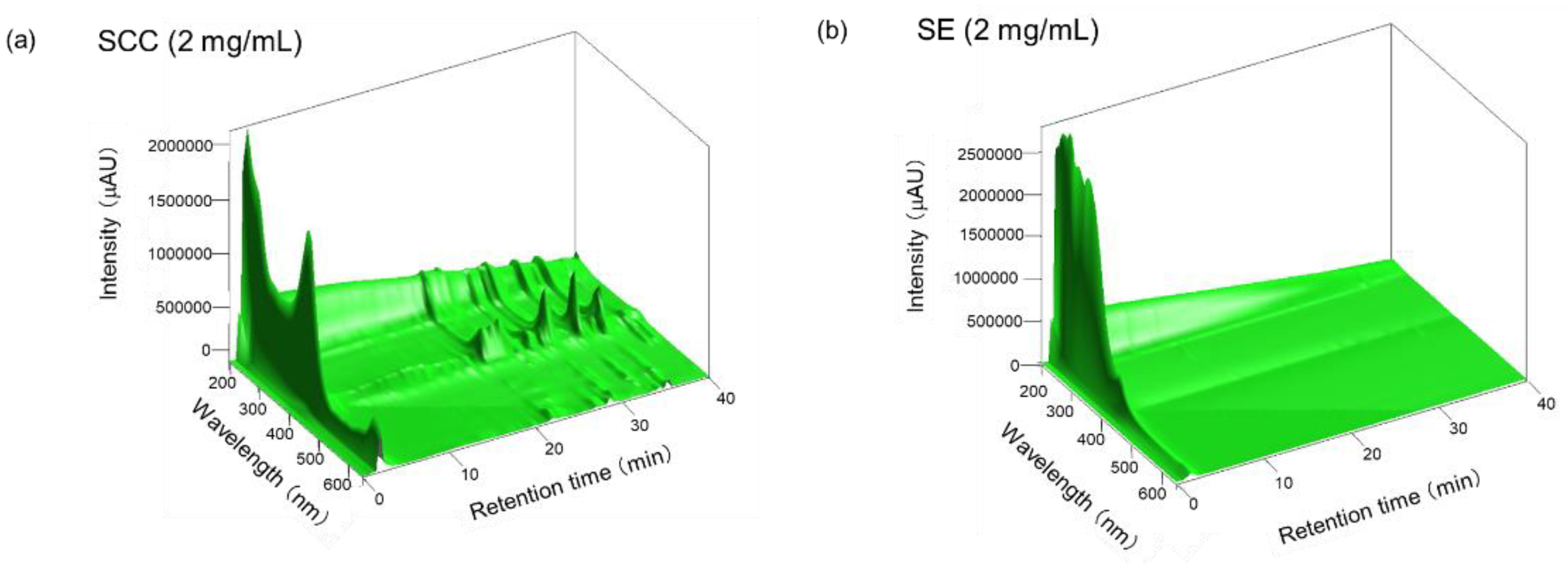

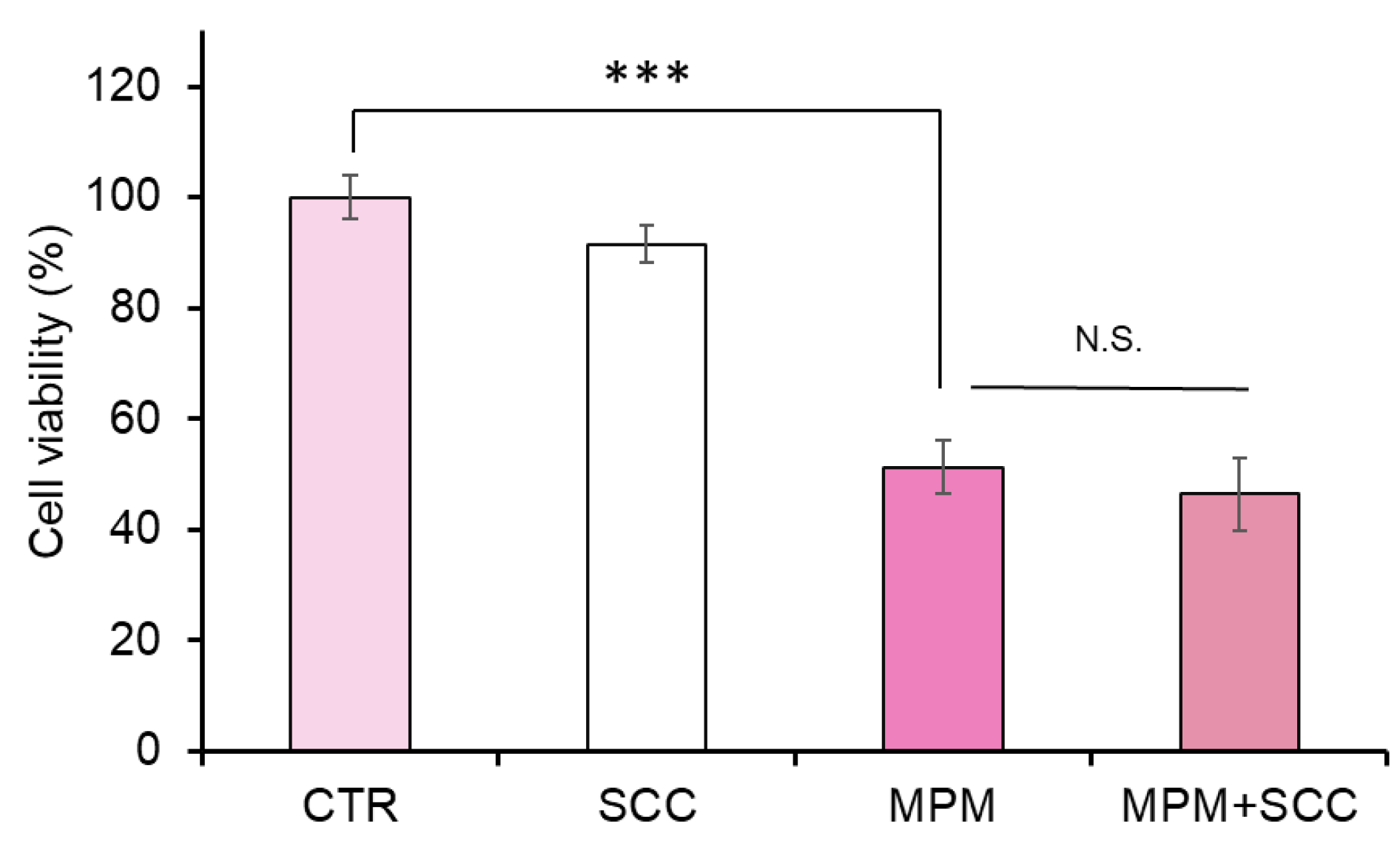

2.3. Cotreatment with Sodium Copper Chlorophyllin (SCC) Failed to Recover MPM-Induced Cell Proliferation Reduction in HEPM Cells

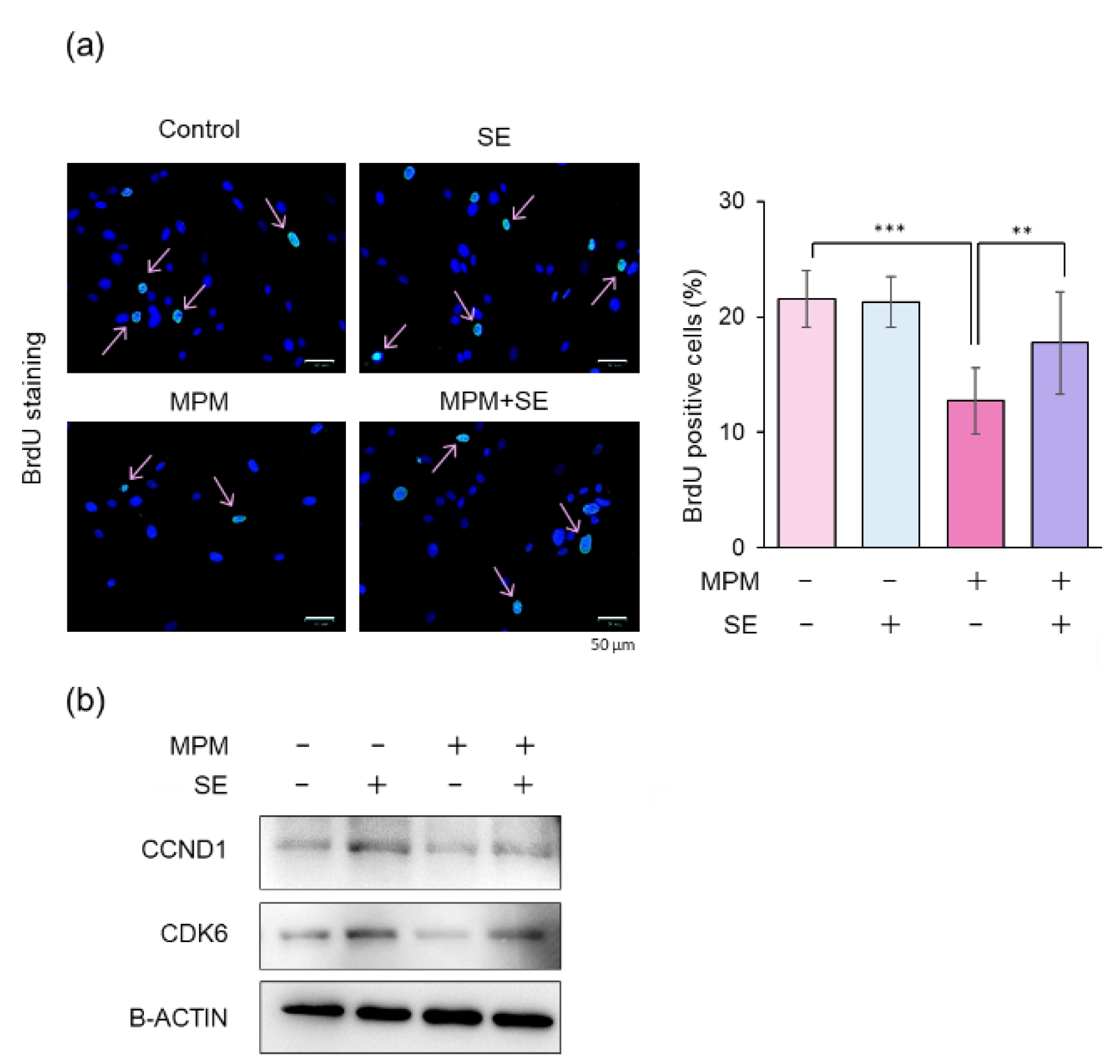

2.4. SE Alleviated MPM-Induced Cell Cycle Arrest in HEPM Cells

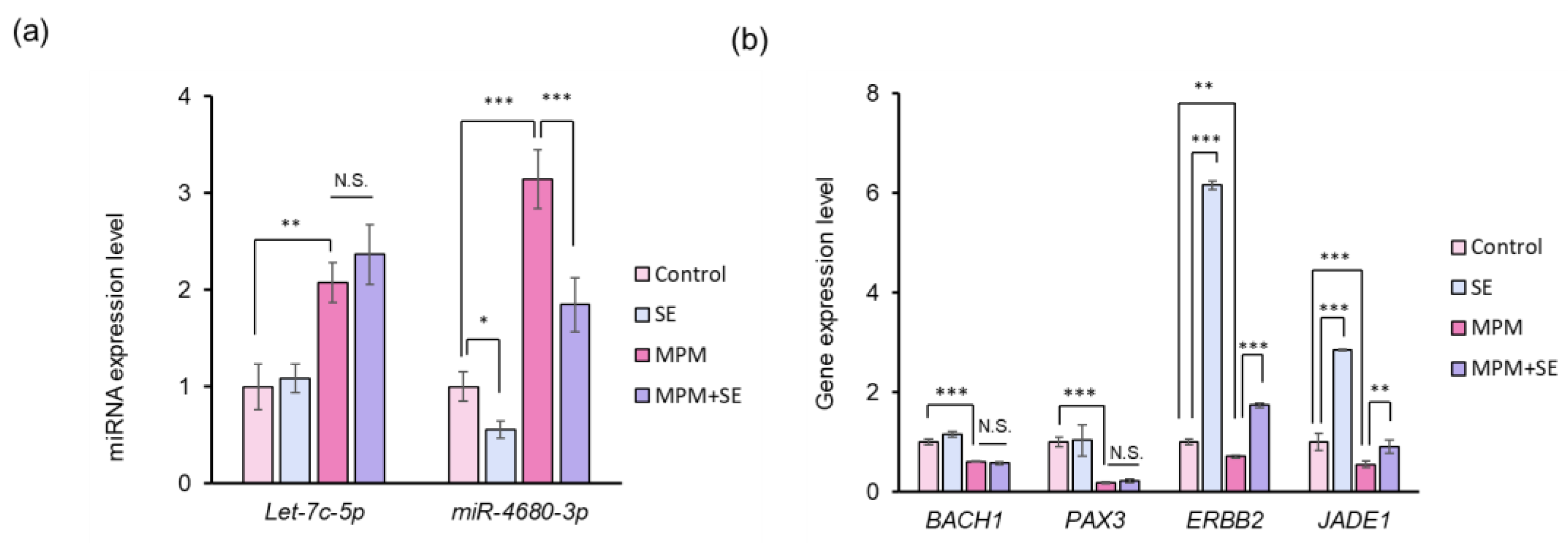

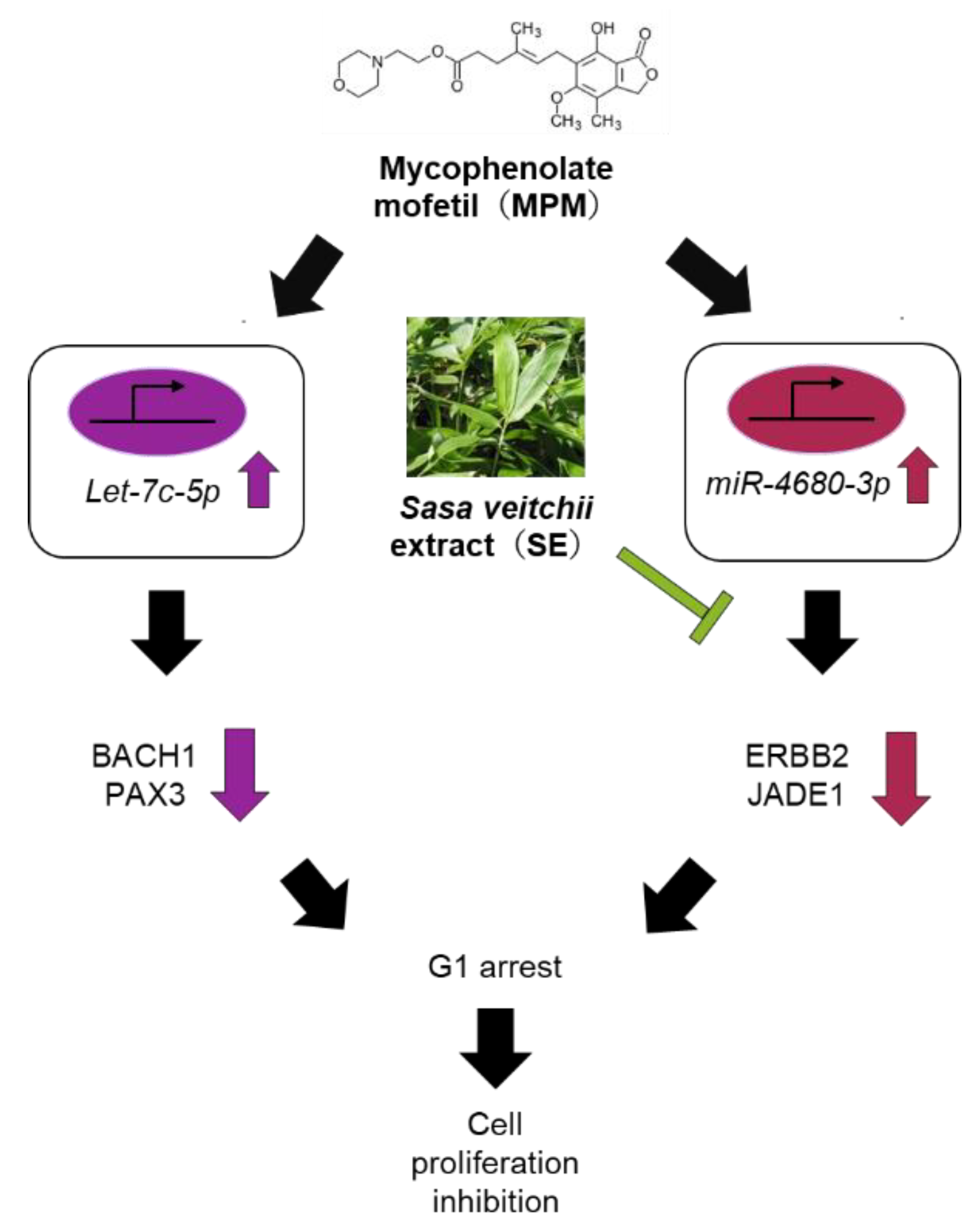

2.5. SE Downregulated miR-4680-3p and Upregulated Its Downstream Genes in HEPM Cells

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture

4.2. Preparation of SE

4.3. HPLC Analysis

4.4. Cell Proliferation Assay

4.5. Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) Incorporation Assay

4.6. Western Blot Analysis

4.7. Quantitative RT-PCR

4.8. Statistical Analyses

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| atRA | all-trans-retinoic acid |

| CDK | cyclin-dependent kinases |

| CL | Cleft lip |

| CP | Cleft palate |

| CL/P | Cleft lip with or without cleft palate |

| EMT | epithelial-mesenchymal transition |

| HEPM | human embryonic palatal mesenchymal |

| HPLC | High performance liquid chromatography |

| miRNA | microRNA |

| MPM | Mycophenolate mofetil |

| Pax | Paired box gene |

| SE | Sasa veitchii extract |

| SCC | sodium copper chlorophyllin |

| TGF | transforming growth factor |

| WNT | Wingless/integrase-1 |

References

- Sadler, T.W. Establishing the Embryonic Axes: Prime Time for Teratogenic Insults. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 2017, 4. [Google Scholar]

- van Gelder, M.M.; van Rooij, I.A.; de Jong-van den Berg, L.T.; Roeleveld, N. Teratogenic mechanisms associated with prenatal medication exposure. Therapie 2014, 69, 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Babai, A.; Irving, M. Orofacial Clefts: Genetics of Cleft Lip and Palate. Genes (Basel) 2023, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, M.J.; Marazita, M.L.; Beaty, T.H.; Murray, J.C. Cleft lip and palate: Understanding genetic and environmental influences. Nat Rev Genet 2011, 12, 167–178. [Google Scholar]

- Blencowe, H.; Cousens, S.; Modell, B.; Lawn, J. Folic acid to reduce neonatal mortality from neural tube disorders. Int J Epidemiol 2010, 39 (Suppl 1), i110–i021. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado, E.; Murillo, J.; Barrio, C.; del Rio, A.; Perez-Miguelsanz, J.; Lopez-Gordillo, Y.; Partearroyo, T.; Paradas, I.; Maestro, C.; Martinez-Sanz, E.; Varela-Moreiras, G.; Martinez-Alvarez, C. Occurrence of cleft-palate and alteration of Tgf-beta(3) expression and the mechanisms leading to palatal fusion in mice following dietary folic-acid deficiency. Cells Tissues Organs 2011, 194, 406–420. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Kato, H.; Sato, H.; Yamaza, H.; Hirofuji, Y.; Han, X.; Masuda, K.; Nonaka, K. Folic acid-mediated mitochondrial activation for protection against oxidative stress in human dental pulp stem cells derived from deciduous teeth. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2019, 508, 850–856. [Google Scholar]

- Won, H.J.; Kim, J.W.; Won, H.S.; Shin, J.O. Gene Regulatory Networks and Signaling Pathways in Palatogenesis and Cleft Palate: A Comprehensive Review. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Im, H.; Song, Y.; Kim, J.K.; Park, D.K.; Kim, D.S.; Kim, H.; Shin, J.O. Molecular Regulation of Palatogenesis and Clefting: An Integrative Analysis of Genetic, Epigenetic Networks, and Environmental Interactions. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, S.; Zhou, J.; Fanelli, C.; Wee, Y.; Bonds, J.; Schneider, P.; Mues, G.; D’Souza, R.N. Small-molecule Wnt agonists correct cleft palates in Pax9 mutant mice in utero. Development 2017, 144, 3819–3828. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Lan, Y.; Jiang, R. Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Palate Development. J Dent Res 2017, 96, 1184–1191. [Google Scholar]

- Letra, A.; Bjork, B.; Cooper, M.E.; Szabo-Rogers, H.; Deleyiannis, F.W.; Field, L.L.; Czeizel, A.E.; Ma, L.; Garlet, G.P.; Poletta, F.A.; Mereb, J.C.; Lopez-Camelo, J.S.; Castilla, E.E.; Orioli, I.M.; Wendell, S.; Blanton, S.H.; Liu, K.; Hecht, J.T.; Marazita, M.L.; Vieira, A.R.; Silva, R.M. Association of AXIN2 with non-syndromic oral clefts in multiple populations. J Dent Res 2012, 91, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostowska, A.; Hozyasz, K.K.; Wojcicki, P.; Lasota, A.; Dunin-Wilczynska, I.; Jagodzinski, P.P. Association of DVL2 and AXIN2 gene polymorphisms with cleft lip with or without cleft palate in a Polish population. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2012, 94, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Murray, S.A.; Oram, K.F.; Gridley, T. Multiple functions of Snail family genes during palate development in mice. Development 2007, 134, 1789–1797. [Google Scholar]

- Graf, D.; Malik, Z.; Hayano, S.; Mishina, Y. Common mechanisms in development and disease: BMP signaling in craniofacial development. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2016, 27, 129–139. [Google Scholar]

- Ueharu, H.; Mishina, Y. BMP signaling during craniofacial development: New insights into pathological mechanisms leading to craniofacial anomalies. Front Physiol 2023, 14, 1170511. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, A.; Jia, P.; Mallik, S.; Fei, R.; Yoshioka, H.; Suzuki, A.; Iwata, J.; Zhao, Z. Critical microRNAs and regulatory motifs in cleft palate identified by a conserved miRNA-TF-gene network approach in humans and mice. Brief Bioinform 2020, 21, 1465–1478. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.S.; Choi, Y.J.; Cho, J.; Lee, H.; Lee, H.; Park, S.J.; Park, J.S.; Hong, Y.C. Environmental and Genetic Risk Factors of Congenital Anomalies: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. J Korean Med Sci 2021, 36, e183. [Google Scholar]

- Spinder, N.; Prins, J.R.; Bergman, J.E.H.; Smidt, N.; Kromhout, H.; Boezen, H.M.; de Walle, H.E.K. Congenital anomalies in the offspring of occupationally exposed mothers: A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies using expert assessment for occupational exposures. Hum Reprod 2019, 34, 903–919. [Google Scholar]

- Luteijn, J.M.; Brown, M.J.; Dolk, H. Influenza and congenital anomalies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod 2014, 29, 809–823. [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti, D.; Appel, L.D.; Siedersberger Neto, P.; Guimaraes, G.W.; Zhang, L. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and birth defects in children: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Cad Saude Publica 2014, 30, 2491–2529. [Google Scholar]

- Puho, E.H.; Szunyogh, M.; Metneki, J.; Czeizel, A.E. Drug treatment during pregnancy and isolated orofacial clefts in hungary. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2007, 44, 194–202. [Google Scholar]

- Ebadifar, A.; Hamedi, R.; KhorramKhorshid, H.R.; Kamali, K.; Moghadam, F.A. Parental cigarette smoking, transforming growth factor-alpha gene variant and the risk of orofacial cleft in Iranian infants. Iran J Basic Med Sci 2016, 19, 366–373. [Google Scholar]

- Junaid, M.; Narayanan, M.B.A.; Jayanthi, D.; Kumar, S.G.R.; Selvamary, A.L. Association between maternal exposure to tobacco, presence of TGFA gene, and the occurrence of oral clefts. A case control study. Clin Oral Investig 2018, 22, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.C.; Feinbaum, R.L.; Ambros, V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 1993, 75, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wightman, B.; Ha, I.; Ruvkun, G. Posttranscriptional regulation of the heterochronic gene lin-14 by lin-4 mediates temporal pattern formation in C. elegans. Cell 1993, 75, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Humphries, B.; Yang, C. The microRNA-200 family: Small molecules with novel roles in cancer development, progression and therapy. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 6472–6498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shull, L.C.; Artinger, K.B. Epigenetic regulation of craniofacial development and disease. Birth Defects Res 2024, 116, e2271. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Shi, B.; Chen, J.; Li, C.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, G. An E2F1/MiR-17-92 Negative Feedback Loop mediates proliferation of Mouse Palatal Mesenchymal Cells. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 5148. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Bai, Y.; Li, H.; Greene, S.B.; Klysik, E.; Yu, W.; Schwartz, R.J.; Williams, T.J.; Martin, J.F. MicroRNA-17-92, a direct Ap-2alpha transcriptional target, modulates T-box factor activity in orofacial clefting. PLoS Genet 2013, 9, e1003785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Li, D.; Lou, S.; Zhang, C.; Du, Y.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, W.; Ma, L.; Wang, L. A functional polymorphism in the pre-miR-146a gene is associated with the risk of nonsyndromic orofacial cleft. Hum Mutat 2018, 39, 742–750. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, A.; Li, A.; Gajera, M.; Abdallah, N.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, Z.; Iwata, J. MicroRNA-374a, -4680, and -133b suppress cell proliferation through the regulation of genes associated with human cleft palate in cultured human palate cells. BMC Med Genomics 2019, 12, 93. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, C.; Lou, S.; Zhu, G.; Fan, L.; Yu, X.; Zhu, W.; Ma, L.; Wang, L.; Pan, Y. Identification of New miRNA-mRNA Networks in the Development of Non-syndromic Cleft Lip With or Without Cleft Palate. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 631057. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Chen, B. Clinical mycophenolic acid monitoring in liver transplant recipients. World J Gastroenterol 2014, 20, 10715–10728. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Narayanaswami, P.; Sanders, D.B.; Thomas, L.; Thibault, D.; Blevins, J.; Desai, R.; Krueger, A.; Bibeau, K.; Liu, B.; Guptill, J.T.; Group, P.-M. S. Comparative effectiveness of azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil for myasthenia gravis (PROMISE-MG): A prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol 2024, 23, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Perez-Aytes, A.; Ledo, A.; Boso, V.; Saenz, P.; Roma, E.; Poveda, J.L.; Vento, M. In utero exposure to mycophenolate mofetil: A characteristic phenotype? Am J Med Genet A 2008, 146A, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Song, T.; Ronde, E.M.; Ma, G.; Cui, H.; Xu, M. The important role of MDM2, RPL5, and TP53 in mycophenolic acid-induced cleft lip and palate. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021, 100, e26101. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka, H.; Horita, H.; Tsukiboshi, Y.; Kurita, H.; Ogata, A.; Ogata, K. Cleft Palate Induced by Mycophenolate Mofetil Is Associated with miR-4680-3p and let-7c-5p in Human Palate Cells. Noncoding RNA 2025, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka, H.; Nonogaki, T.; Fukaya, S.; Ichimaru, Y.; Nagatsu, A.; Yoshikawa, M.; Fujii, H.; Nakao, M. Sasa veitchii extract protects against carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatic fibrosis in mice. Environ Health Prev Med 2018, 23, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, I.; Kagawa, S.; Tsuneki, H.; Tanaka, K.; Nagashima, F. Multitasking bamboo leaf-derived compounds in prevention of infectious, inflammatory, atherosclerotic, metabolic, and neuropsychiatric diseases. Pharmacol Ther 2022, 235, 108159. [Google Scholar]

- Kojima, S.; Hakamata, M.; Asanuma, T.; Suzuki, R.; Tsuruda, J.I.; Nonoyama, T.; Lin, Y.; Fukatsu, H.; Koide, N.; Umezawa, K. Cellular Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Activities of Bamboo Sasa albomarginata Leaf Extract and Its Constituent Coumaric Acid Methyl Ester. ScientificWorldJournal 2022, 2022, 8454865. [Google Scholar]

- Hamanaka, J.; Mikami, Y.; Horiuchi, A.; Yano, A.; Amano, F.; Shibata, S.; Ogata, A.; Ogata, K.; Nagatsu, A.; Miura, N.; Sano, M.; Suzui, M.; Yoshioka, H. Sasa veitchii extract exhibits antitumor effect against murine pancreatic adenocarcinoma in vivo and in vitro. Traditional & Kampo Medicine n/a, (n/a). [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka, H.; Wu, S.; Moriishi, T.; Tsukiboshi, Y.; Yokota, S.; Miura, N.; Yoshikawa, M.; Inagaki, N.; Matsushita, Y.; Nakao, M. Sasa veitchii extract alleviates nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in methionine–choline deficient diet-induced mice by regulating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha. Traditional & Kampo Medicine 2023, 10, 259–268. [Google Scholar]

- Sakagami, H.; Tomomura, M. Dental Application of Natural Products. Medicines (Basel) 2018, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukiboshi, Y.; Mikami, Y.; Horita, H.; Ogata, A.; Noguchi, A.; Yokota, S.; Ogata, K.; Yoshioka, H. Protective effect of Sasa veitchii extract against all-trans-retinoic acid-induced inhibition of proliferation of cultured human palate cells. Nagoya J Med Sci 2024, 86, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yoshioka, H.; Tsukiboshi, Y.; Horita, H.; Kurita, H.; Ogata, A.; Ogata, K.; Horiguchi, H. Sasa veitchii extract alleviates phenobarbital-induced cell proliferation inhibition by upregulating transforming growth factor-beta 1. Traditional & Kampo Medicine 2024, 11, 192–199. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.X.; Dai, M.S.; Lu, H. Mycophenolic acid activation of p53 requires ribosomal proteins L5 and L11. J Biol Chem 2008, 283, 12387–12392. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Yang, H.; Wang, Y.; Tian, J.; Li, R.; Zhou, X. Evaluation of the inhibitory effect of tacrolimus combined with mycophenolate mofetil on mesangial cell proliferation based on the cell cycle. Int J Mol Med 2020, 46, 1582–1592. [Google Scholar]

- Takebe, N.; Cheng, X.; Fandy, T.E.; Srivastava, R.K.; Wu, S.; Shankar, S.; Bauer, K.; Shaughnessy, J.; Tricot, G. IMP dehydrogenase inhibitor mycophenolate mofetil induces caspase-dependent apoptosis and cell cycle inhibition in multiple myeloma cells. Mol Cancer Ther 2006, 5, 457–466. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka, H.; Horita, H.; Tsukiboshi, Y.; Kurita, H.; Mikami, Y.; Ogata, K.; Ogata, A. Mycophenolate mofetil reduces cell viability associated with the miR-205-PAX9 pathway in human lip fibroblast cells. Biomed Res 2025, 46, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Schoen, C.; Aschrafi, A.; Thonissen, M.; Poelmans, G.; Von den Hoff, J.W.; Carels, C.E.L. MicroRNAs in Palatogenesis and Cleft Palate. Front Physiol 2017, 8, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, M.; Tan, M.; Ji, Y.; Shu, S.; Liang, Y. MiRNA-470-5p suppresses epithelial-mesenchymal transition of embryonic palatal shelf epithelial cells by targeting Fgfr1 during palatogenesis. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2023, 248, 1124–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Shen, Z.; Xing, Y.; Zhao, H.; Liang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhong, X.; Shi, L.; Wan, X.; Zhou, J.; Tang, S. MiR-106a-5p modulates apoptosis and metabonomics changes by TGF-beta/Smad signaling pathway in cleft palate. Exp Cell Res 2020, 386, 111734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, H.; Ramakrishnan, S.S.; Shim, J.; Suzuki, A.; Iwata, J. Excessive All-Trans Retinoic Acid Inhibits Cell Proliferation Through Upregulated MicroRNA-4680-3p in Cultured Human Palate Cells. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 618876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshioka, H.; Jun, G.; Suzuki, A.; Iwata, J. Dexamethasone Suppresses Palatal Cell Proliferation through miR-130a-3p. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukiboshi, Y.; Horita, H.; Mikami, Y.; Noguchi, A.; Yokota, S.; Ogata, K.; Yoshioka, H. Involvement of microRNA-4680-3p against phenytoin-induced cell proliferation inhibition in human palate cells. J Toxicol Sci 2024, 49, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Roush, S.; Slack, F.J. The let-7 family of microRNAs. Trends Cell Biol 2008, 18, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.L.; Chen, P.S.; Johansson, G.; Kuo, M.L. Function and regulation of let-7 family microRNAs. Microrna 2012, 1, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarden, Y.; Pines, G. The ERBB network: At last, cancer therapy meets systems biology. Nat Rev Cancer 2012, 12, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avraham, R.; Yarden, Y. Feedback regulation of EGFR signalling: Decision making by early and delayed loops. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2011, 12, 104–117. [Google Scholar]

- Arteaga, C.L.; Engelman, J.A. ERBB receptors: From oncogene discovery to basic science to mechanism-based cancer therapeutics. Cancer Cell 2014, 25, 282–303. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Timms, J.F.; White, S.L.; O’Hare, M.J.; Waterfield, M.D. Effects of ErbB-2 overexpression on mitogenic signalling and cell cycle progression in human breast luminal epithelial cells. Oncogene 2002, 21, 6573–6586. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Suzuki, A.; Iwata, J.; Jun, G. Secondary Genome-Wide Association Study Using Novel Analytical Strategies Disentangle Genetic Components of Cleft Lip and/or Cleft Palate in 1q32.2. Genes (Basel) 2020, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Borgal, L.; Rinschen, M.M.; Dafinger, C.; Hoff, S.; Reinert, M.J.; Lamkemeyer, T.; Lienkamp, S.S.; Benzing, T.; Schermer, B. Casein kinase 1 alpha phosphorylates the Wnt regulator Jade-1 and modulates its activity. J Biol Chem 2014, 289, 26344–26356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriwardana, N.S.; Meyer, R.D.; Panchenko, M.V. The novel function of JADE1S in cytokinesis of epithelial cells. Cell Cycle 2015, 14, 2821–2834. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Havasi, A.; Haegele, J.A.; Gall, J.M.; Blackmon, S.; Ichimura, T.; Bonegio, R.G.; Panchenko, M.V. Histone acetyl transferase (HAT) HBO1 and JADE1 in epithelial cell regeneration. Am J Pathol 2013, 182, 152–162. [Google Scholar]

- Panchenko, M.V. Structure, function and regulation of jade family PHD finger 1 (JADE1). Gene 2016, 589, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Lachance, C.; Ricketts, M.D.; McCullough, C.E.; Gerace, M.; Black, B.E.; Cote, J.; Marmorstein, R. The scaffolding protein JADE1 physically links the acetyltransferase subunit HBO1 with its histone H3-H4 substrate. J Biol Chem 2018, 293, 4498–4509. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chitalia, V.C.; Foy, R.L.; Bachschmid, M.M.; Zeng, L.; Panchenko, M.V.; Zhou, M.I.; Bharti, A.; Seldin, D.C.; Lecker, S.H.; Dominguez, I.; Cohen, H.T. Jade-1 inhibits Wnt signalling by ubiquitylating beta-catenin and mediates Wnt pathway inhibition by pVHL. Nat Cell Biol 2008, 10, 1208–1216. [Google Scholar]

- Tauriello, D.V.; Maurice, M.M. The various roles of ubiquitin in Wnt pathway regulation. Cell Cycle 2010, 9, 3700–3709. [Google Scholar]

- Shtutman, M.; Zhurinsky, J.; Simcha, I.; Albanese, C.; D’Amico, M.; Pestell, R.; Ben-Ze’ev, A. The cyclin D1 gene is a target of the beta-catenin/LEF-1 pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999, 96, 5522–5527. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dashwood, R. Chlorophylls as anticarcinogens (review). Int J Oncol 1997, 10, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Suparmi, S.; Fasitasari, M.; Martosupono, M.; Mangimbulude, J.C. Comparisons of Curative Effects of Chlorophyll from Sauropus androgynus (L) Merr Leaf Extract and Cu-Chlorophyllin on Sodium Nitrate-Induced Oxidative Stress in Rats. J Toxicol 2016, 2016, 8515089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortes-Eslava, J.; Gomez-Arroyo, S.; Villalobos-Pietrini, R.; Espinosa-Aguirre, J.J. Antimutagenicity of coriander (Coriandrum sativum) juice on the mutagenesis produced by plant metabolites of aromatic amines. Toxicol Lett 2004, 153, 283–292. [Google Scholar]

- Aizenbud, D.; Peri-Front, Y.; Nagler, R.M. Salivary analysis and antioxidants in cleft lip and palate children. Arch Oral Biol 2008, 53, 517–522. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Huang, C.; Ho, J.C.H.; Leung, C.C.T.; Kong, R.Y.C.; Li, Y.; Liang, X.; Lai, K.P.; Tse, W.K.F. The use of glutathione to reduce oxidative stress status and its potential for modifying the extracellular matrix organization in cleft lip. Free Radic Biol Med 2021, 164, 130–138. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Yue, Y.D.; Jiang, H.; Tang, F. Rapid Screening for Flavone C-Glycosides in the Leaves of Different Species of Bamboo and Simultaneous Quantitation of Four Marker Compounds by HPLC-UV/DAD. Int J Anal Chem 2012, 2012, 205101. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Yue, Y.D.; Tang, F.; Sun, J. TLC screening for antioxidant activity of extracts from fifteen bamboo species and identification of antioxidant flavone glycosides from leaves of Bambusa. textilis McClure. Molecules 2012, 17, 12297–12311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, D.J.; Wang, C.J.; Yeh, C.W.; Tseng, T.H. Inhibition of the Proliferation and Invasion of C6 Glioma Cells by Tricin via the Upregulation of Focal-Adhesion-Kinase-Targeting MicroRNA-7. J Agric Food Chem 2018, 66, 6708–6716. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, S.F.; Qiu, Y.Y.; Chen, L.M.; Jiang, Y.Y.; Huang, W.; Xie, Z.X.; Tang, X.; Sun, J. Myricetin alleviated hepatic steatosis by acting on microRNA-146b/thyroid hormone receptor b pathway in high-fat diet fed C57BL/6J mice. Food Funct 2019, 10, 1465–1477. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, Q.; Chen, T.; Jiang, N.; Guo, Z. Myricetin ameliorates ox-LDL-induced HUVECs apoptosis and inflammation via lncRNA GAS5 upregulating the expression of miR-29a-3p. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 19637. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Najafipour, R.; Momeni, A.M.; Mirmazloomi, Y.; Moghbelinejad, S. Vitexin Induces Apoptosis in MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cells through the Regulation of Specific miRNAs Expression. Int J Mol Cell Med 2022, 11, 197–206. [Google Scholar]

- Zaki, A.; Mohsin, M.; Khan, S.; Khan, A.; Ahmad, S.; Verma, A.; Ali, S.; Fatma, T.; Syed, M.A. Vitexin mitigates oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage, pyroptosis and regulates small nucleolar RNA host gene 1/DNA methyltransferase 1/microRNA-495 axis in sepsis-associated acute lung injury. Inflammopharmacology 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, M.G.; Ko, H.C.; Kim, S.J. Effects of p-coumaric acid on microRNA expression profiles in SNU-16 human gastric cancer cells. Genes Genomics 2020, 42, 817–825. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kheiry, M.; Dianat, M.; Badavi, M.; Mard, S.A.; Bayati, V. Does p-coumaric acid improve cardiac injury following LPS-induced lung inflammation through miRNA-146a activity? Avicenna J Phytomed 2020, 10, 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.Q.; Li, M.H.; Qin, Y.M.; Jiang, H.Y.; Zhang, X.; Wu, M.H. Luteolin Inhibits Tumorigenesis and Induces Apoptosis of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells via Regulation of MicroRNA-34a-5p. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka, H.; Tominaga, S.; Amano, F.; Wu, S.; Torimoto, S.; Moriishi, T.; Tsukiboshi, Y.; Yokota, S.; Miura, N.; Inagaki, N.; Matsushita, Y.; Maeda, T. Juzentaihoto alleviates cisplatin-induced renal injury in mice. Traditional & Kampo Medicine 2024, 11, 147–155. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).