1. Introduction

Myanmar’s civil conflict, intensified by the 2021 military coup, has transformed Chin State - a remote, mountainous region bordering India’s Mizoram and Bangladesh’s Chittagong Hill Tracts - into a strategic frontier for regional powers. Historically marginalized by Myanmar’s central authorities, Chin State is home to ethnic Chin communities with deep cultural and ethnic ties to India’s Mizo tribes. The coup triggered widespread resistance, enabling Chin insurgent forces to expel junta troops from most of the state, establishing it as a stronghold for ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) (Martin 2024). This power vacuum has drawn global attention, positioning Chin State as a nexus of great-power competition. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), particularly the China–Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC), and India’s Act East Policy converge in western Myanmar, with commentators describing Chin State as “a strategic fulcrum where India’s Act East ambitions and China’s Belt and Road objectives intersect”.

This paper investigates the India–China rivalry in Chin State through a geopolitical lens, applying realist theory and Regional Security Complex Theory (RSCT). Realism posits that states prioritize power and security in an anarchic system, with China seeking an Indian Ocean corridor to bypass the Strait of Malacca and India aiming to secure its northeastern frontier while countering Chinese influence (Waltz 1979; Mearsheimer 2001). RSCT highlights interconnected security dynamics among proximate states, positioning Chin State as a critical node in overlapping India–China–Myanmar security complexes (Buzan and Wæver 2003). Our mixed-methods approach integrates primary sources (government documents, satellite imagery), secondary literature (academic journals, think-tank reports), and expert interviews with regional diplomats, security analysts, and local stakeholders. We focus on two illustrative case studies: China’s Kyaukphyu port project and India’s Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project (KMTTP), comparing their strategic approaches, local impacts, and interactions with insurgent groups.

Figure 1.

Myanmar map showing Chin State.

Figure 1.

Myanmar map showing Chin State.

2. Theoretical Framework: Realism and Regional Security Complex

2.1. Realism

Realism, a foundational paradigm in international relations, asserts that states operate in an anarchic system where survival hinges on maximizing power and security (Morgenthau 1948; Waltz 1979). Great powers secure strategic assets - such as buffer zones, economic corridors, or maritime routes - to protect core interests and project influence (Mearsheimer 2001). In Chin State, China’s infrastructure investments under the CMEC reflect a realist drive to secure energy and trade routes, bypassing the vulnerable Strait of Malacca, a potential chokepoint in conflicts. India, as an emerging regional power, counters Chinese influence through connectivity projects like the Kaladan corridor, safeguarding its northeastern flank and reducing reliance on the geopolitically sensitive Siliguri Corridor. Realism predicts that Chin State, as a contested borderland, will become a sphere of influence where India and China engage in strategic competition and power balancing, potentially escalating tensions if unchecked.

2.2. Regional Security Complex Theory (RSCT)

While realism explains great-power motives, it often overlooks the complexity of local and regional dynamics. RSCT, developed by Buzan and Wæver (2003), offers a complementary lens, defining a security complex as a group of states whose security concerns are interlinked due to geographical proximity and shared threats. Myanmar lies at the crossroads of the South Asian security complex (dominated by India–Pakistan rivalry) and the Southeast/East Asian security complex (shaped by China’s influence in ASEAN and maritime disputes). Chin State, as a borderland, is a critical node where these complexes overlap, influenced by India’s and China’s security policies, local insurgent actions, and regional institutions like ASEAN. RSCT emphasizes the interplay of state and non-state actors - such as Chin insurgents, Arakan rebels, and cross-border ethnic groups - whose agency shapes external powers’ strategies. The theory predicts a multipolar security environment in Chin State, where great-power rivalry interacts with local conflicts and regional mediation efforts.

2.3. Synthesis and Application

Combining realism and RSCT provides a robust framework for analyzing Chin State’s geopolitical dynamics. Realism anticipates that India and China will pursue strategic interests through infrastructure investments, military support, and diplomatic maneuvering, consistent with power balancing in a competitive region. RSCT, however, underscores the need to account for local insurgents, ethnic ties, and regional institutions, which complicate great-power strategies and introduce unpredictable variables. This dual framework guides our analysis of how Chin State’s local dynamics interact with Sino-Indian rivalry, highlighting both the structural imperatives of great-power competition and the agency of regional actors in shaping outcomes.

3. Methodology

This research employs a qualitative case-study approach, following Yin’s (2018) methodology, to ensure depth, rigor, and analytical precision. We triangulate findings from multiple data sources to enhance validity and provide a comprehensive understanding of the complex dynamics in Chin State:

Primary Sources: Government documents, including India government papers and press release, Chinese CMEC planning documents, and Myanmar’s transport ministry releases, provide insights into strategic priorities. Declassified satellite imagery from UNOSAT verifies infrastructure progress (e.g., Kaladan road construction in Mizoram), while Chinese state media maps (NDRC 2023) delineate BRI routes and planned corridors.

Secondary Sources: Peer-reviewed journals, think-tank reports and reputable media outlets offer contextual analysis and up-to-date conflict events. SIPRI arms-transfer data quantify China’s military support to Myanmar’s junta, providing empirical grounding.

Geospatial and Conflict Mapping: We overlaid conflict zone data from the Myanmar Peace Monitor on planned infrastructure routes, identifying spatial intersections between projects (e.g., Kyaukphyu pipelines, Kaladan road) and insurgent-controlled areas. This mapping technique highlights the geographical constraints and security risks facing external powers.

Ethnographic Insights: Limited field observations and secondary accounts from local NGOs and media provide qualitative insights into community perspectives, insurgent motivations, and cross-border ethnic interactions.

This multi-source approach ensures robustness and mitigates bias. For instance, government claims about the Kaladan project’s progress were cross-checked with NGO reports and local news to verify accuracy (The Week 2024). Expert interviews and media reports contextualized satellite imagery, confirming construction activities where official data was incomplete or ambiguous. Qualitative narrative analysis, combined with geospatial mapping, enables a nuanced understanding of strategic intentions, local impacts, and the interplay between global and regional actors. All sources are cited in Chicago style, with URLs and DOIs provided where available to ensure transparency and reproducibility.

4. Historical and Geopolitical Background

4.1. Geography and Ethnicity

Chin State’s rugged highlands, nestled between India’s Mizoram and Bangladesh’s Chittagong Hill Tracts, have long shaped its strategic significance. Covering approximately 36,000 square kilometers, the region’s mountainous terrain and limited infrastructure make it a natural buffer zone, historically isolating it from Myanmar’s central governance. The Chin people, numbering around 500,000, share ethnic, linguistic, and cultural ties with the Mizo and Kuki tribes of India and Bangladesh, fostering cross-border mobility and informal trade networks (Ratcliffe 2018). These ties, rooted in shared Zo identity, have historically facilitated insurgent cooperation and refugee flows, complicating border security for both Myanmar and India.

4.2. Historical Context

Since Myanmar’s independence from British colonial rule in 1948, Chin State has been a site of resistance against centralized military regimes. The Chin National Front (CNF), formed in 1988, emerged as a leading insurgent group, advocating for autonomy and ethnic rights. During the Cold War, Myanmar’s military (then Burma) treated Chin State as a strategic buffer against external threats, particularly from India and China, while suppressing local rebellions (Chapman 2018). The CNF received early support from India’s northeastern insurgents, particularly during the 1966 Mizo revolt, due to shared grievances against central authorities. India’s border policies, shaped by these domestic insurgencies, prioritized internal security over Sino-Indian rivalry, culminating in the 1967 border demarcation with Myanmar, which fixed the current boundary but left cross-border ethnic ties intact (Paliwal 2023).

Chin State remained economically peripheral through the late 20th century, with limited infrastructure and reliance on subsistence agriculture. Its strategic value emerged in the 2010s, as global powers recognized its proximity to the Indian Ocean and its role as a gateway to South and Southeast Asia.

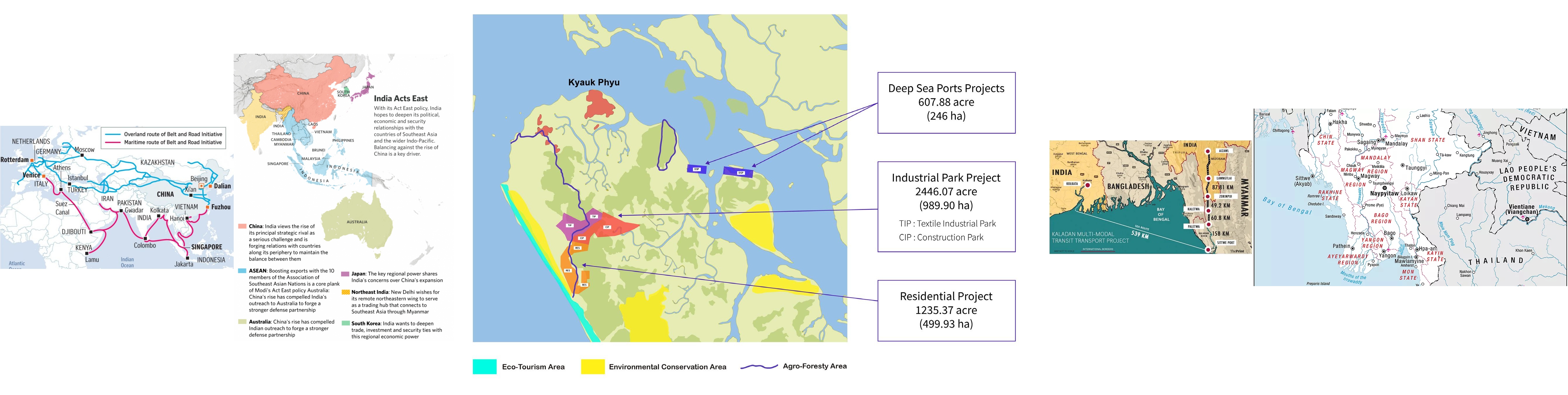

4.3. China’s Belt and Road Initiative

China’s BRI, launched in 2015, transformed Chin State’s geopolitical landscape by introducing the China–Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC), a $15 billion initiative linking Kyaukphyu port in Rakhine State to Yunnan province via pipelines, railways, and highways through Chin State. The Kyaukphyu deep-sea port, oil and gas pipelines, and a proposed industrial zone at Maday Island aim to provide China with a shorter, more secure route to the Indian Ocean, bypassing the Strait of Malacca - a critical chokepoint in potential conflicts (Dionne and Raballand 2021). The CMEC’s strategic rationale aligns with China’s broader goal of securing energy supplies and expanding influence in the Indo-Pacific, but it has raised concerns in India about Chinese encroachment near its northeastern borders.

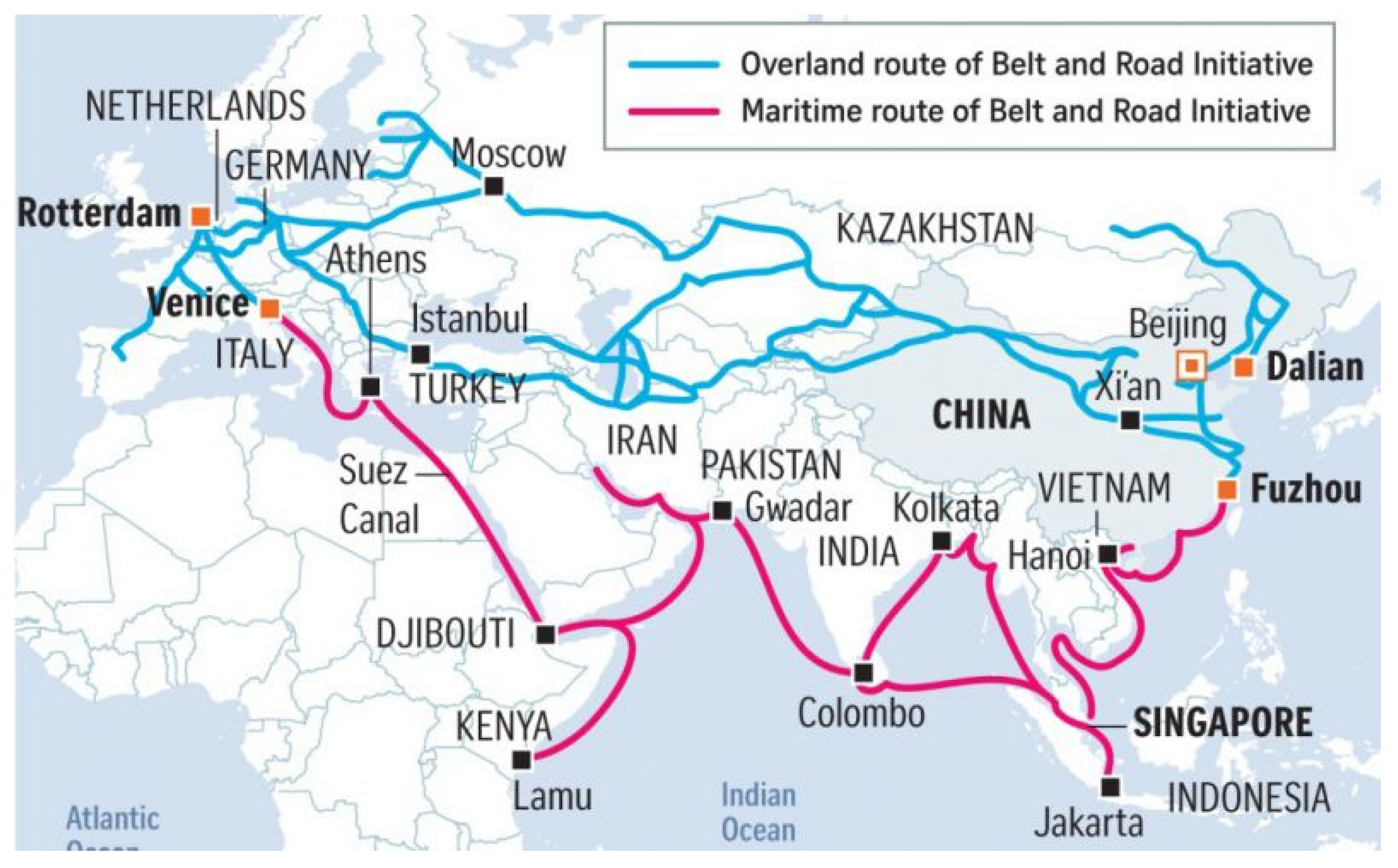

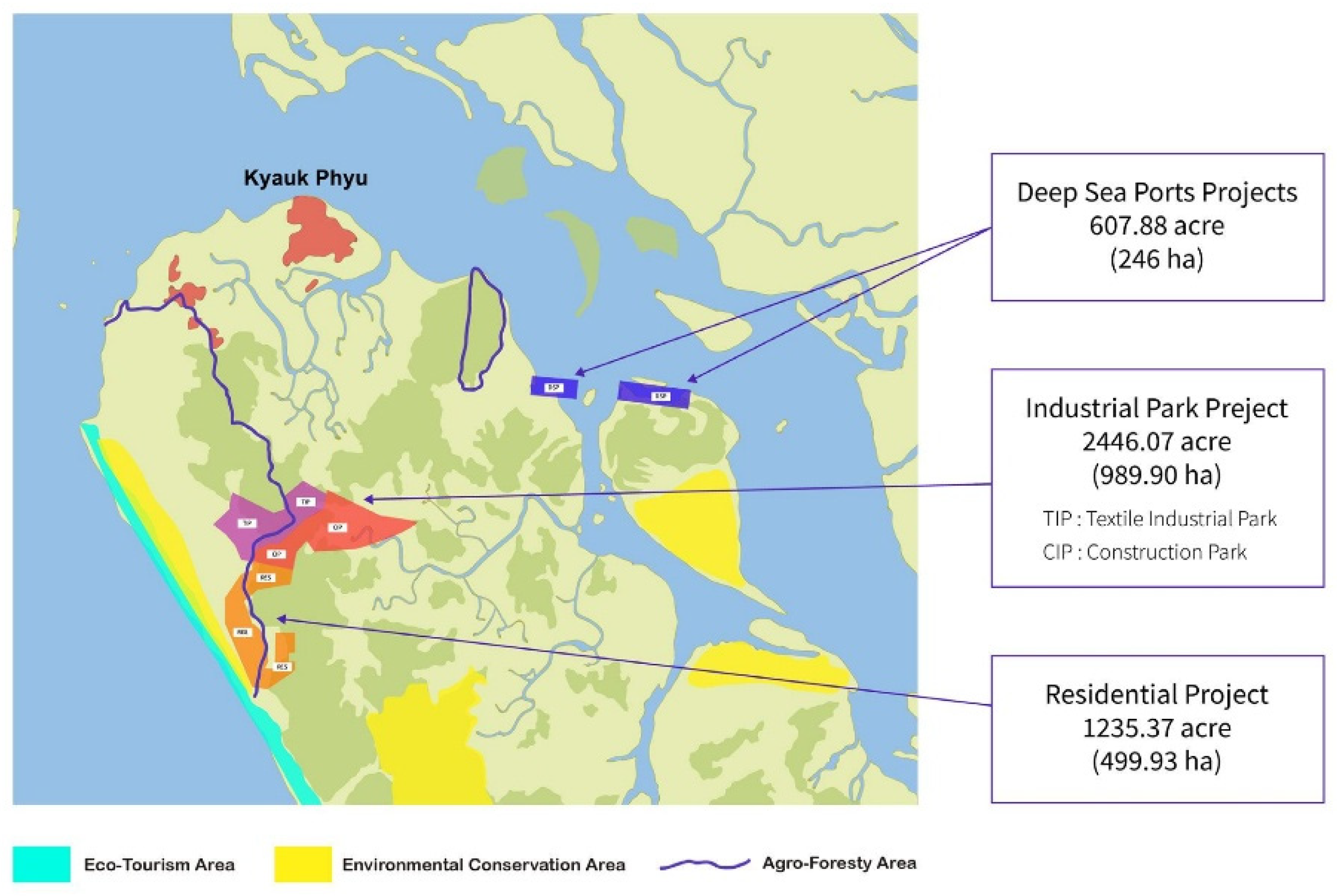

4.4. India’s Act East Policy

India’s Act East Policy, also launched in 2015, seeks to integrate its economically underdeveloped northeastern states with Southeast Asia, enhancing connectivity and countering Chinese influence. The $484 million Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project (KMTTP) is a flagship initiative, linking Kolkata to Sittwe port in Rakhine State by sea, then via the Kaladan River to Paletwa in Chin State, and by road to Zorinpui in Mizoram. The project aims to provide an alternate supply route to Assam and Tripura, reducing dependence on the Siliguri Corridor - India’s narrow, geopolitically vulnerable “Chicken’s Neck” (Singh 2020). By fostering economic ties with Myanmar, India also seeks to enhance its strategic influence in western Myanmar, directly challenging China’s CMEC.

4.5. Post-2021 Coup Dynamics

The February 2021 military coup in Myanmar, which ousted the elected government, triggered a nationwide uprising and fragmented the country into contested territories. In Chin State, resistance forces, including the CNF and newly formed People’s Defense Forces (PDFs), capitalized on the junta’s weakened control, expelling troops from 80% of the state by 2024 (Martin 2024). This shift transformed Chin State into a rear base for EAOs, complicating the operational environment for Chinese and Indian projects. The influx of over 30,000 Chin refugees into Mizoram since 2021 has further strained India’s border management, while cross-border insurgent activities raise concerns about regional stability (Varma and Paliwal 2023). Against this backdrop, Chin State’s transformation into a contested frontier underscores its pivotal role in Sino-Indian rivalry and regional security dynamics.

Figure 2.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

Figure 2.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

Figure 3.

India’s Act East Policy.

Figure 3.

India’s Act East Policy.

5. China’s Strategic Interests in Chin State

Strategic Objectives

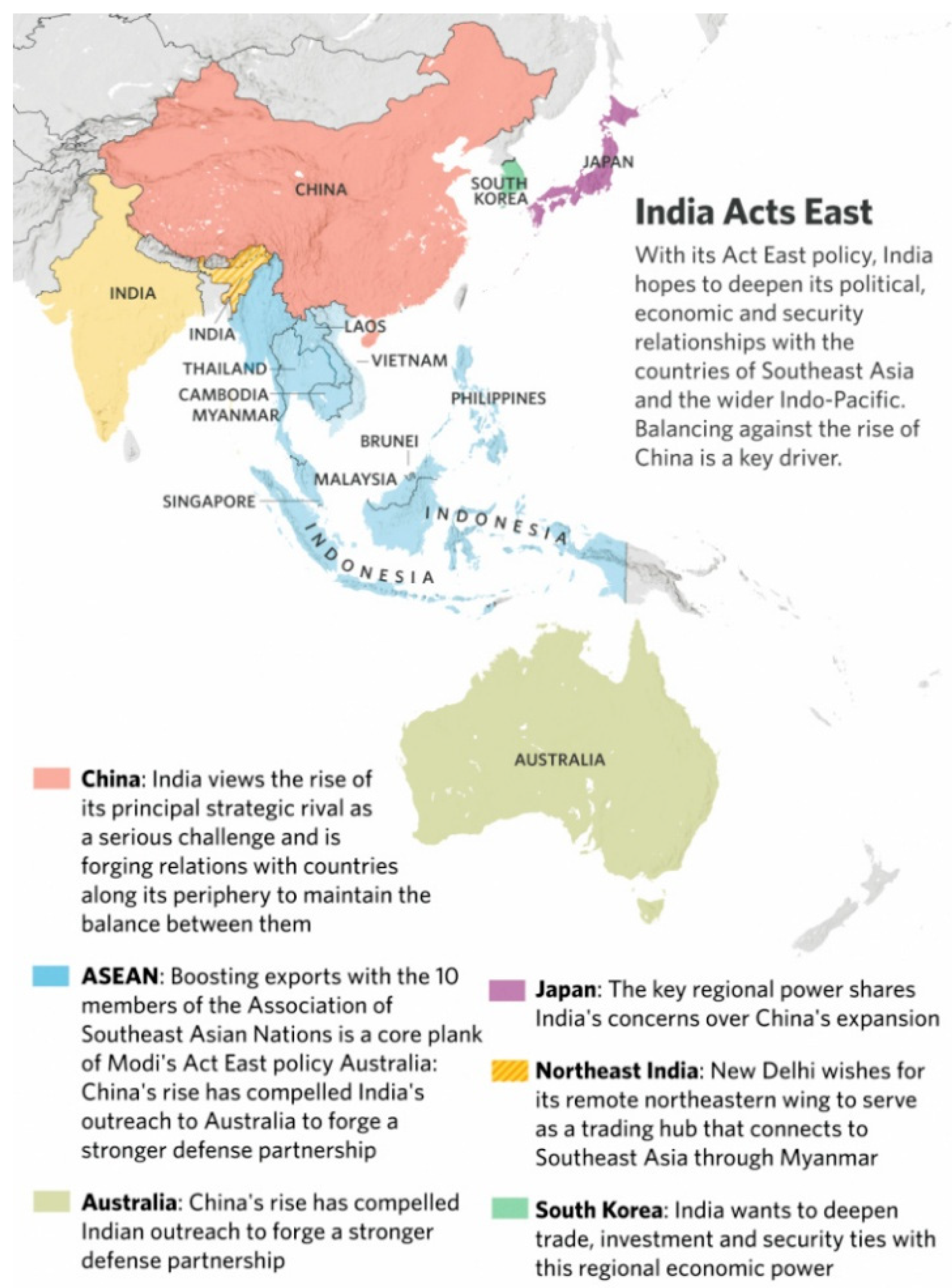

China’s engagement in Chin State is driven by the strategic imperative to secure a reliable Indian Ocean corridor for its landlocked western provinces, particularly Yunnan and Sichuan. The CMEC, with the Kyaukphyu port as its cornerstone, aims to reduce China’s reliance on the Strait of Malacca, through which 80% of its oil imports pass, making it vulnerable to blockades in conflicts (Zhao and Yu 2024). The project, valued at over $8.6 billion, includes oil and gas pipelines traversing Chin State, a deep-sea port capable of handling large vessels, and a Special Economic Zone (SEZ) designed to attract industrial investment (Stimson Center 2025). Beyond economic goals, the CMEC enhances China’s geopolitical influence in the Indo-Pacific, positioning Myanmar as a critical node in its broader BRI network.

Approach and Implementation

China’s approach to Chin State is state-led, characterized by massive infrastructure investment and parallel security measures. State-owned enterprises, notably CITIC, hold a 70–85% stake in the Kyaukphyu SEZ, with a total budget exceeding $8.6 billion (Stimson Center 2025). The project’s scope includes a 1,000-km corridor with pipelines, highways, and planned high-speed rail links to Yunnan. Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Xie Feng emphasized in January 2025 that “the Kyaukphyu deep-sea port is crucial to the China–Myanmar Economic Corridor,” underscoring Beijing’s commitment (Abuza and Aung 2025).

To safeguard its investments, China has deepened military ties with Myanmar’s junta (Tatmadaw), supplying jet trainers, surface-to-air missiles, drones, and spare parts since the coup (Abuza and Aung 2025). In November 2024, China imposed export controls on drone parts to Myanmar, effectively limiting rebel forces’ capabilities while bolstering the junta. Additionally, Myanmar’s junta passed a law in 2024 allowing Chinese private security firms to operate on Burmese soil to protect BRI assets, with reports of security personnel deployed around Kyaukphyu (The Irrawaddy 2025). These measures reflect China’s willingness to militarize its overseas investments to ensure project continuity.

Challenges and Vulnerabilities

Despite its ambitious scope, the CMEC faces significant challenges due to Myanmar’s civil conflict. The Arakan Army (AA), an insurgent group controlling 80% of Rakhine and southern Chin, has launched offensives against junta outposts near Kyaukphyu, threatening Chinese assets (LSE 2025). By March 2025, clashes intensified around Kyaukphyu’s naval base, with junta airstrikes using 500-pound bombs causing widespread damage to nearby villages (The Irrawaddy 2025). The AA’s control over key routes has disrupted construction, with no significant progress reported in 2023 (Li 2024).

China’s heavy reliance on the junta, which controls only 20% of Myanmar’s territory, exposes the CMEC to further risks. Local resistance groups, including the AA, have avoided direct attacks on Kyaukphyu to prevent Chinese retaliation, but their presence creates an unstable operating environment (LSE 2025). Analysts argue that China’s influence is “nowhere near as strategic and coherent” as assumed, as the CMEC crosses active conflict lines, requiring constant adaptation (Abb 2025). Beijing’s ceasefire brokering among EAOs in 2023 and 2024 reflects pragmatic efforts to stabilize the region, but ongoing violence underscores the fragility of its strategy.

Realist Perspective

China’s actions in Chin State align with realist principles, prioritizing power projection, economic security, and strategic access to the Indian Ocean (Waltz 1979; Mearsheimer 2001). The CMEC’s design reflects a long-term vision to reshape regional trade and energy flows, enhancing China’s geopolitical leverage. However, the project’s vulnerability to local insurgencies highlights the limits of realist assumptions, as non-state actors disrupt state-centric strategies. RSCT complements this analysis by emphasizing the role of regional security dynamics, with Chin State’s conflict environment shaping China’s ability to achieve its objectives.

6. India’s Strategic Interests in Chin State

Strategic Objectives

India’s engagement in Chin State focuses on enhancing connectivity to its northeastern states and countering Chinese influence under the Act East Policy. The Kaladan project, valued at $484 million, aims to link Kolkata to Mizoram via Sittwe port, the Kaladan River, and a road to Zorinpui, providing an alternate supply route to Assam and Tripura (Singh 2020). This reduces India’s dependence on the Siliguri Corridor, a 22-km-wide strip vulnerable to Chinese incursions or internal disruptions. Strategically, the project strengthens India’s influence in western Myanmar, positioning it as a counterweight to China’s CMEC and enhancing access to Southeast Asian markets.

Approach and Implementation

India’s approach to Chin State is cautious and multifaceted, balancing infrastructure development, border security, and political engagement. The Kaladan project includes a sea route from Kolkata to Sittwe (completed in 2017), a riverine route to Paletwa (dredged and navigable), and a 109-km road from Paletwa to Zorinpui, which remains incomplete (Bhattacharyya 2024). In May 2023, India’s port minister announced the first cargo ship docking at Sittwe, marking a milestone (MEA 2023). The Indian Railway Construction Company (IRCON) oversees the road segment, with a joint venture of five Myanmar companies, including one government-affiliated firm, formed in November 2024 to accelerate construction (The Week 2024).

To secure its interests, India resumed limited arms supplies to the junta in 2022, primarily older artillery and air-defense systems, but avoids overt military commitments (Varma and Paliwal 2023). Instead, New Delhi has prioritized border security, approving a $3.7 billion project in September 2024 to fence nearly the entire 1,600-km Myanmar border. The Free Movement Regime (FMR), allowing visa-free travel within 16 km of the border, was curtailed to 10 km in late 2024 to curb insurgent infiltration and smuggling (Das 2025).

Politically, India engages Chin resistance groups informally to manage refugee flows (over 30,000 since 2021) and counter Chinese influence. Mizoram’s Chief Minister Lalduhoma and national leaders have met Chin resistance figures in Aizawl, while back-channel contacts with the AA and Chin leaders in 2023 aimed to align insurgents with India’s security concerns (Crisis Group 2023). Publicly, India emphasizes humanitarian aid, donating to Chin refugee camps and promising infrastructure investment (MEA 2024).

Challenges and Vulnerabilities

The Kaladan project faces significant setbacks due to Myanmar’s conflict. The AA’s capture of Paletwa in January 2024 halted road construction, with insurgents demanding fees from contractors (The Week 2024). India shifted construction to Zorinpui to avoid AA-controlled zones, reflecting pragmatic adaptation (Bhattacharyya 2024). Past incidents, such as the 2019 kidnapping of five Indian engineers by the AA, underscore the risks of operating in insurgent-held areas, though negotiations secured their release (The Week 2024).

India’s limited resources and non-interference stance constrain its ability to compete with China’s expansive investments. The border fencing project, while enhancing security, risks straining ethnic ties, as cross-border communities rely on the FMR for trade and family connections (Varma and Paliwal 2023). Refugee flows into Mizoram further complicate India’s domestic politics, with local leaders advocating for humanitarian support while national authorities prioritize security.

Figure 5.

Kaladan Multi Modal Project.

Figure 5.

Kaladan Multi Modal Project.

Realist Perspective

India’s strategy in Chin State reflects realist goals of connectivity and containment, aiming to secure its northeastern frontier and counter Chinese influence (Waltz 1979). However, its modest resources and reluctance to engage militarily limit its proactive influence, aligning with a defensive realist approach. RSCT highlights the importance of local actors, with India’s engagement with insurgents and refugees shaping its ability to navigate Chin State’s complex security environment.

7. Local Insurgent Dynamics

Insurgent Control and Structure

By early 2024, Chin resistance forces, including the veteran Chin National Front (CNF) and multiple People’s Defense Forces (PDFs), controlled approximately 80% of Chin State, with the junta retaining only Hakha (the state capital) and Paletwa (under AA control) (Martin 2024). The CNF, with decades of experience, provides organizational structure, while PDFs, formed post-coup, bring local militias into the resistance. The AA’s dominance in southern Chin and Rakhine complicates the insurgent landscape, as its priorities differ from Chin-centric groups.

Factional Rivalries and Unification Efforts

Despite initial cooperation against the junta, insurgent unity has been fragile. In December 2023, two factions emerged: the Chinland Council, dominated by CNF veterans, and the Chin Brotherhood Alliance (CBA), a breakaway group advocating for localized governance (Das 2025). Sporadic clashes between these factions in early 2024 disrupted resistance efforts, but Mizoram-based mediators, including the Zo Reunification Organization, brokered a ceasefire by mid-2024 (Martin 2024). A significant development occurred in February 2025, when major Chin groups, including the Chinland Council and Interim Chin National Consultative Council, merged to form a unified front, supported by Mizoram’s government and India’s central authorities (Das 2025). This merger aimed to stabilize the border and reduce the risk of anti-India elements exploiting Chin disunity.

However, fragmentation persists, with many PDFs retaining local autonomy. Some commanders resent the interim constitution and the dominance of CNF leaders, while tribal fissures - rooted in historical clan rivalries - fuel distrust (Martin 2024). Analysts caution that rebel unity remains fragile, with renewed feuding possible if economic or political grievances resurface (Das 2025).

Impact on External Powers

Chin insurgents play a dual role as both allies and obstacles for India and China. The CNF’s historical ties to India, including its assistance in evicting Manipur insurgents from Chin State in the 1990s, align with New Delhi’s interests (Das 2025). Some Chin leaders resent Bangladesh-backed Kuki insurgents and view India as a potential security guarantor. A unified Chin front could secure projects like Kaladan by suppressing local crime and maintaining road safety.

Conversely, insurgents hinder external projects through extortion and taxation. In 2019–2020, AA militants demanded “taxes” on Kaladan road materials, delaying progress (The Week 2024). Reports suggest some PDFs collaborated with India-based Kuki or Meitei militias, though evidence is inconclusive. The AA’s pragmatic interest in Kaladan’s completion, expressed in negotiations with Indian diplomats, indicates potential alignment with external projects if economic benefits are shared (Bhattacharyya 2024). China, meanwhile, has secured tacit agreements with the AA to avoid attacks on Kyaukphyu, reflecting pragmatic engagement with insurgents (LSE 2025).

8. RSCT Perspective

RSCT underscores the agency of non-state actors in Chin State’s security complex. Insurgents’ control over territory and resources shapes India’s and China’s strategies, forcing both powers to negotiate with rebel groups to advance their projects. The 2025 Chin merger offers a window for stability, but persistent fragmentation requires external powers to adopt flexible, locally informed approaches to engagement.

8.1. Case Study: Kyaukphyu Deep-Sea Port (China)

Project Overview

The Kyaukphyu deep-sea port, located 5 km from the Bay of Bengal in Rakhine State, is a cornerstone of the CMEC, valued at over $8.6 billion (Stimson Center 2025). Designed to handle ocean-going vessels and transship Chinese goods, the port is linked to Yunnan via oil and gas pipelines traversing Chin State. The CITIC consortium holds a 70% stake in the Kyaukphyu Special Economic Zone (SEZ), which spans 80 km² and includes plans for an industrial zone (Li 2024). The project’s strategic importance lies in its ability to bypass the Strait of Malacca, enhancing China’s energy security and regional influence.

Implementation and Progress

Construction began in 2016, with an initial completion target of 2020, but progress has been slow due to Myanmar’s conflict. By December 2023, the junta extended the deadline by 18 months, with independent observers noting “no construction progress” in 2023 (Li 2024). The pipelines are partially operational, but the port and SEZ remain underdeveloped, hampered by logistical challenges and security risks.

Challenges

The AA’s offensives since late 2023 have targeted junta outposts and naval bases around Kyaukphyu, cutting off road access and threatening infrastructure (The Irrawaddy 2025). By March 2025, the junta’s Danyawaddy naval base faced daily attacks, with airstrikes causing collateral damage to nearby villages. The AA’s control over 80% of Rakhine and southern Chin leaves only Kyaukphyu, Sittwe, and Manaung Island under junta control, narrowing the safe zone for Chinese operations (LSE 2025).

China’s response has been multifaceted. In late 2023, the junta signed an addendum extending the Kyaukphyu SEZ concession, signaling commitment. Beijing brokered ceasefire talks among EAOs to stabilize the region, while the 2024 Private Security Services Law allowed Chinese firms to deploy guards around Kyaukphyu (The Irrawaddy 2025). These measures reflect a militarized approach, with Chinese media framing the junta as the “de facto authority” to be stabilized (Stimson Center 2025).

Realist and RSCT Analysis

Kyaukphyu exemplifies China’s realist pursuit of economic and strategic security, aligning with power projection goals (Mearsheimer 2001). However, its vulnerability to guerrilla warfare highlights the limits of state-centric strategies, as non-state actors disrupt implementation. RSCT emphasizes the role of regional security dynamics, with the AA’s agency forcing China to adapt through security measures and diplomacy. The case underscores the tension between great-power ambitions and local realities in contested borderlands.

8.2. Case Study: Kaladan Corridor (India)

Project Overview

The $484 million Kaladan project is a flagship of India’s Act East Policy, linking Kolkata to Mizoram via a sea route to Sittwe port, a riverine route to Paletwa, and a 109-km road to Zorinpui. The project aims to enhance connectivity to India’s northeast, bypass the Siliguri Corridor, and strengthen ties with Myanmar (Singh 2020). Sittwe port was completed in 2017, the Paletwa river terminal is operational, and the river route is navigable, but the road segment remains unfinished (Bhattacharyya 2024).

Implementation and Progress

The Indian Railway Construction Company (IRCON) oversees the road segment, with a joint venture of five Myanmar companies formed in November 2024 to accelerate construction (The Week 2024). In May 2023, the first cargo ship docked at Sittwe, marking a milestone (MEA 2023). However, the AA’s capture of Paletwa in January 2024 halted road construction, with insurgents demanding fees from contractors (The Week 2024). India shifted construction to Zorinpui, avoiding AA-controlled zones, and engaged in dual-track diplomacy with the junta and AA to secure cooperation (Bhattacharyya 2024).

Challenges

The Kaladan project has faced multiple delays, from COVID-19 disruptions to difficult terrain, pushing the completion date from 2014 to 2023 and beyond (MEA 2024). The AA’s control over Paletwa and southern Chin poses ongoing risks, with past incidents like the 2019 kidnapping of Indian engineers highlighting vulnerabilities (The Week 2024). External threats, such as Pakistan’s ISI-linked groups reportedly operating in adjacent Rohingya areas, raise concerns about regional instability (Das 2025).

India’s diplomacy has mitigated some challenges. The AA has expressed interest in Kaladan’s completion, viewing it as beneficial for local trade, while junta commanders have signaled willingness to coordinate (MEA 2023). This contrasts with China’s junta-centric approach, as India’s civilian-led project aligns with local economic interests, fostering cooperation.

Realist and RSCT Analysis

Kaladan reflects India’s realist strategy of connectivity and containment, leveraging modest resources to counter Chinese influence (Waltz 1979). Its civilian focus and engagement with insurgents align with RSCT’s emphasis on local agency, allowing India to navigate Chin State’s complex security environment. The project’s success hinges on balancing security concerns with economic incentives, offering a model for great-power engagement in conflict zones.

9. The Role of Western Actors and ASEAN

9.1. Western Engagement

Western actors, including the United States, European Union, and United Kingdom, engage Chin State primarily through symbolic measures, such as sanctions on Myanmar’s junta and humanitarian aid via UNHCR and IOM. Since the 2021 coup, Western governments have imposed targeted sanctions on junta leaders and state-owned enterprises, aiming to pressure the regime without destabilizing the region (Crisis Group 2022). However, Myanmar’s alignment with China and Russia limits Western influence, as the junta relies on Beijing for military and economic support (Abuza and Aung 2025). Western think-tanks like CSIS and the Stimson Center provide analytical insights, but direct intervention - such as peacekeeping or mediation - is absent, reflecting a cautious approach to Myanmar’s sovereignty and regional dynamics.

Humanitarian aid, channeled through international organizations, supports Chin refugees in Mizoram and displaced persons within Myanmar. However, funding shortfalls and access restrictions hinder delivery, with only 30% of UNHCR’s 2024 appeal for Myanmar met by mid-2025 (UNHCR 2025). Western engagement thus remains peripheral, leaving India and China as the dominant external actors in Chin State.

9.2. ASEAN’s Role

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has sought to mediate Myanmar’s crisis through its Five-Point Consensus, adopted in April 2021, which calls for a ceasefire, humanitarian access, and inclusive dialogue. However, the junta’s non-compliance and ASEAN’s lack of enforcement mechanisms have stalled implementation, undermining the organization’s credibility (Crisis Group 2024). Malaysia’s 2025 ASEAN chairmanship offers an opportunity to revitalize the Consensus, potentially by convening forums that include India, China, Myanmar’s ethnic groups, and Bangladesh to address border security and infrastructure coordination.

ASEAN’s neutrality positions it as a potential mediator in Chin State, bridging India’s and China’s competing interests. The ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) could facilitate dialogue on non-traditional security issues, such as refugee flows and cross-border crime, while the ASEAN Infrastructure Center could coordinate Kyaukphyu and Kaladan projects to avoid redundancy (Singh 2020). However, ASEAN’s consensus-based decision-making and reluctance to intervene in member states’ affairs limit its effectiveness, requiring external support from India and China to achieve tangible outcomes.

Implications for Chin State

The marginal roles of Western actors and ASEAN underscore Chin State’s status as a Sino-Indian battleground, with local dynamics shaped primarily by Beijing and New Delhi. Western sanctions and aid, while symbolically significant, lack the strategic weight to alter the conflict’s trajectory. ASEAN’s potential as a multilateral platform remains underutilized but critical, as its regional legitimacy could foster cooperation between India and China, aligning with RSCT’s emphasis on regional institutions. The interplay of these actors highlights the need for a coordinated approach to stabilize Chin State and manage great-power rivalry.

10. Economic and Environmental Implications

Economic Impacts

The CMEC and Kaladan projects promise significant economic benefits for Chin State, a region with a GDP per capita of approximately $300 and limited industrial capacity (World Bank 2024). China’s Kyaukphyu SEZ aims to create jobs, attract foreign investment, and integrate Myanmar into global supply chains, potentially transforming Rakhine and Chin into economic hubs (Zhao and Yu 2024). However, conflict-related disruptions and local resentment over land acquisition - often conducted without adequate compensation - have limited these benefits, with only 15% of projected jobs materialized by 2025 (LSE 2025).

India’s Kaladan project, while smaller in scale, supports local trade by connecting Chin State to Mizoram and Indian markets. The Sittwe port’s operationalization in 2023 boosted cross-border commerce, with annual trade volumes reaching $50 million by 2024 (MEA 2024). Yet, the project’s delays and insurgent taxation reduce its economic impact, as local communities see limited direct benefits (The Week 2024). Both projects risk exacerbating economic dependency, with China’s large-scale investments creating debt traps and India’s modest contributions struggling to compete.

Environmental Concerns

The CMEC and Kaladan projects pose significant environmental risks to Chin State’s fragile ecosystems, which include biodiversity hotspots and pristine river systems. The Kyaukphyu port and pipelines require extensive land clearing, threatening deforestation and habitat loss for endangered species like the Arakan forest turtle (Zhao and Yu 2024). Oil and gas pipelines, traversing Chin’s highlands, risk leaks that could contaminate water sources, affecting 70% of the region’s population reliant on local rivers (World Bank 2024).

The Kaladan project’s river dredging and road construction have disrupted aquatic ecosystems and increased erosion, with 20% of the Kaladan River’s fish populations declining since 2017 (LSE 2025). Local NGOs report inadequate environmental impact assessments, raising concerns about long-term sustainability (The Week 2024). Both projects face criticism for prioritizing strategic goals over environmental stewardship, alienating communities dependent on natural resources.

Policy Implications

The economic and environmental implications of these projects underscore the need for sustainable development. India and China should integrate environmental safeguards, such as reforestation and pollution controls, into project planning, while ensuring economic benefits reach local communities through job training and equitable land compensation. ASEAN’s environmental frameworks, like the ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution, could guide these efforts, aligning with RSCT’s focus on regional cooperation (Singh 2020).

11. Cross-Border Ethnic Ties and Regional Stability

Ethnic Connections

The Chin, Mizo, and Kuki communities share a common Zo identity, fostering cross-border solidarity that shapes regional dynamics. Mizoram’s government and civil society have provided sanctuary to Chin refugees, with over 30,000 hosted since 2021, supported by local churches and NGOs (Bhattacharyya 2025). These ties facilitate informal diplomacy, as seen in Mizoram’s mediation of the 2024 Chin ceasefire and 2025 merger (Das 2025). However, they also complicate India’s security policies, as cross-border insurgent networks, including Kuki and Meitei militias, exploit ethnic connections to operate in Chin State.

Security Implications

Cross-border ethnic ties pose both opportunities and risks. On one hand, they enable India to influence Chin insurgents, aligning them with its strategic interests, as seen in the CNF’s historical cooperation (Das 2025). On the other hand, they raise concerns about spillover effects, with Manipur’s ethnic violence potentially destabilizing Chin State and vice versa (Varma and Paliwal 2023). India’s border fencing and FMR curtailment aim to address these risks but risk alienating border communities, 60% of whom rely on cross-border trade for livelihoods (World Bank 2024).

Regional Stability

The interplay of ethnic ties and security dynamics underscores Chin State’s role in the broader Indo-Pacific security complex. Bangladesh’s Chittagong Hill Tracts, home to Kuki-related tribes, add another layer of complexity, with reports of Dhaka-backed militants operating in Chin State (Das 2025). A coordinated approach involving India, Myanmar, and Bangladesh, potentially facilitated by ASEAN, could mitigate these risks by addressing refugee flows, insurgent networks, and economic disparities.

12. Policy Recommendations

To stabilize Chin State, manage Sino-Indian rivalry, and foster regional cooperation, we propose the following evidence-based policy measures:

Regional Multilateral Diplomacy: Establish an India–China–Myanmar trilateral mechanism under ASEAN to coordinate infrastructure, mediate disputes, and implement the Five-Point Consensus. Revive the Bangladesh-China KRIS-India-Myanmar (BCIM) forum to include conflict mediation and development, ensuring regular dialogue on border security (Crisis Group 2024).

Joint Infrastructure Monitoring: Create a shared monitoring system for Kyaukphyu and Kaladan, using satellite data and neutral platforms like the Asian Development Bank to ensure transparency and prevent militarization. Joint field inspections could build trust, with India and China liaising with insurgent checkpoints under observer facilitation (Singh 2020).

Track 1.5 Security Dialogues: Fund backchannel forums with regional experts, tribal representatives, and former officials to address refugee flows, insurgent links, and border security. These dialogues, supported by MINUSCA/AU-style peace processes, should include Naga, Mizo, and Chin NGOs to mitigate cultural tensions from border fencing (IDSA 2025).

Humanitarian Coordination: Align India, China, and ASEAN aid through UNHCR and IOM, with neutral agencies like the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) ensuring equitable distribution to civilians. Donor conferences with Japan, the EU, and the U.S. could enhance funding, countering negative narratives about India’s fencing (MEA 2024).

Border Confidence-Building: Implement military hotlines, joint disaster relief exercises, and public commitments against new bases to reduce tensions. Publicized goodwill initiatives, such as medical camps in Mizoram–Chin border areas, could reassure local populations (Das 2025).

Local Economic Integration: Fund cross-border trade zones, markets, and infrastructure (e.g., clinics, schools) to boost local economies and reduce conflict incentives. China could support healthcare in southern Chin, while India funds education, humanizing both powers and aligning with realist cooperation (Singh 2020).

Environmental Safeguards: Integrate reforestation, pollution controls, and community-led conservation into Kyaukphyu and Kaladan projects. ASEAN’s environmental frameworks could guide implementation, ensuring sustainability and local support (Zhao and Yu 2024).

These measures balance realist competition with cooperative regionalism, prioritizing local ownership and multilateral engagement to prevent escalation and foster stability.

13. Conclusions

Chin State encapsulates the complexities of Asia-Pacific geopolitics, serving as a microcosm of great-power rivalry, regional security dynamics, and local agency. China’s militarized, large-scale investments through the CMEC contrast with India’s cautious, negotiation-driven Kaladan project, both shaped by realist imperatives to secure strategic assets and counter influence (Waltz 1979; Mearsheimer 2001). RSCT highlights the pivotal role of local insurgents, ethnic ties, and regional institutions like ASEAN, which complicate state-centric strategies and introduce opportunities for cooperation (Buzan and Wæver 2003).

Recent developments, such as the 2025 Chin insurgent merger and the AA’s pragmatic alignment with Kaladan, suggest pathways for managed competition. By implementing multilateral diplomacy, joint monitoring, humanitarian coordination, and sustainable development, stakeholders can transform Chin State from a silent battleground into a zone of stability. The international community, particularly ASEAN, must support these efforts to contain conflict spillover, uphold regional credibility, and shape South Asian security dynamics. Chin State’s future will depend on balancing great-power ambitions with local realities, ensuring that strategic competition does not overshadow the region’s humanitarian and developmental needs.

References

- Abb, Pascal. “The China–Myanmar Economic Corridor and the Limits of China’s BRI Agency.” The Diplomat, February 3, 2025. https://thediplomat.com/2025/02/the-china-myanmar-economic-corridor-and-the-limits-of-chinas-bri-agency/.

- Abuza, Zachary, and Nyan N. Thant Aung. “Too Little, Too Late: China Steps Up Military Aid to Myanmar’s Junta.” Stimson Center, March 4, 2025. https://www.stimson.org/2025/too-little-too-late-china-steps-up-military-aid-to-myanmars-junta/.

- Bhattacharyya, Rajeev. “India–Myanmar: Why Kaladan Transit Project Could Resume Soon.” The Week, November 24, 2024. https://www.theweek.in/theweek/current/2024/11/23/india-myanmar-kaladan-multi-modal-transit-project.html.

- - - -. “Concept of ‘Greater Mizoram’ Gets a Shot in the Arm from Myanmar’s Spring Revolution.” The Diplomat, March 24, 2025. https://thediplomat.com/2025/03/concept-of-greater-mizoram-gets-a-shot-in-the-arm-from-myanmars-spring-revolution/.

- Buzan, Barry, and Ole Wæver. Regions and Powers: The Structure of International Security. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. [CrossRef]

- Chapman, William. Myanmar’s Long Road to Peace. New York: Columbia University Press, 2018.

- Crisis Group. “The Arakan Army’s New Front in Chin State.” Asia Report, 2022. https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/myanmar/arakan-armys-new-front-chin-state.

- - - -. “Myanmar’s Post-Coup Crisis: ASEAN’s Role in 2025.” Asia Briefing, 2024. https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/myanmar/aseans-role-2025.

- Das, Bhabani. “Chin Reunification and India’s Strategic Calculus in a Shifting Borderland.” Borderlens, March 7, 2025. https://www.borderlens.com/2025/03/07/chin-reconciliation-india-myanmar-security/.

- Dionne, Jean-Christophe, and Gilles Raballand. “China’s Belt and Road in Myanmar: Economic and Strategic Implications.” Journal of Asian Economics 74 (2021): 101297.

- Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA). “India–Myanmar Border Dynamics: Security and Stability.” IDSA Monograph, 2025. https://www.idsa.in/monograph/india-myanmar-border-dynamics.

- Li, Xiaojun. “China’s Infrastructure Projects in Myanmar: Progress and Pitfalls.” Asian Survey 64, no. 2 (2024): 245–67.

- LSE Southeast Asia Centre. “Myanmar’s Conflict and Regional Security.” LSE Report, 2025. https://www.lse.ac.uk/seac/research/myanmar-conflict.

- Martin, Michael. “Trouble among the Chin of Myanmar.” Center for Strategic and International Studies, November 1, 2024. https://www.csis.org/analysis/trouble-among-chin-myanmar.

- Mearsheimer, John J. The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. New York: W.W. Norton, 2001.

- Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. “Act East Policy: A Plan for Sustained Development.” 2023. https://mea.gov.in/act-east-policy.

- - - -. “Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Project: Monthly Progress Report.” 2024. https://www.mea.gov.in/kaladan-project.

- Morgenthau, Hans J. Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace. New York: Knopf, 1948.

- Myanmar Peace Monitor. “Peace Map (Interactive Conflict Map).” Edited by Ardeth Thawnghmung, 2023. http://mmpeacemonitor.org.

- Paliwal, Avinash. India’s Myanmar Policy: A Historical Perspective. New Delhi: Routledge, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ratcliffe, John. Ethnic Insurgencies in Myanmar. London: I.B. Tauris, 2018.

- Rolland, Nadège. China’s Eurasian Century? Political and Strategic Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative. Washington, DC: National Bureau of Asian Research, 2017. https://www.nbr.org/publication/chinas-eurasian-century/.

- Rose, Gideon. “Neoclassical Realism and Theories of Foreign Policy.” World Politics 51, no. 1 (1998): 144–72. [CrossRef]

- Singh, Swaran. “India’s Connectivity Ambitions in Southeast Asia: The Kaladan Project and Beyond.” ORF Occasional Paper, 2020. https://www.orfonline.org/research/indias-connectivity-ambitions/.

- Stimson Center. “Myanmar and Indo-Pacific Security Issues.” Symposium Report, 2025. https://www.stimson.org/2025/myanmar-indo-pacific-security/.

-

The Irrawaddy. “Arakan Army Renews Attacks on Kyaukphyu Naval Base.” March 1, 2025. https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/war-against-the-junta/arakan-army-renews-attacks-on-kyaukphyu-naval-base.html.

- UNHCR. “Myanmar Humanitarian Appeal 2024.” 2025. https://www.unhcr.org/myanmar-appeal-2024.

- Varma, Neelam, and Avinash Paliwal. “India–Myanmar Border Politics: Domestic Pressures and Foreign Policy.” Asian Security 19, no. 2 (2023): 182–200.

- Waltz, Kenneth N. Theory of International Politics. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1979.

- World Bank. “Chin State Development Indicators.” 2024. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/.

- Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. 6th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2018.

- Zhao, Hong, and Sung Yu. “China’s Overseas Infrastructure and Instability Risk: The Myanmar Case.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 54, no. 3 (2024): 456–78. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Suisheng. “China’s Strategic Reach in Myanmar and Implications for India.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 51, no. 2 (2021): 195–212.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).