1. Introduction

Globally, 34% of the adult population over aged 18 are considered to be hypertensive of which only 58.7% of the patients are aware of their status [

1]. It is estimated that in the Indian population 28% of the population, which is older than 18 have hypertension, which amounts to 220 million people [

2]. Of the 220 million hypertensive patients in India, only 12% of the patients have their hypertension in control [

3]. Overall, 90% of adults with hypertension in India were either undiagnosed, untreated, or even though they were being treated their hypertension was not optimally controlled [

2]. The Fifth National Family Survey [NFHS-5] of hypertension reported that not only is there a continued increase in the prevalence of hypertension in India, but it is also increasingly observed in younger age patients [

4]. Chronic hypertension is a predisposing factor for multiple cardiovascular diseases [

5] and cardiovascular disease are now the leading cause of death in India [

6].

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Indian healthcare faces challenges of inadequate resources, insufficient funding, poor healthcare infrastructure, and rural-urban disparity [

7]. The WHO’s data on the distribution of doctors around the world shows that while there are 26.1 doctors per 10,000 patients in the US, that number in India is only 7.3 doctors per 10,000 patients for a population of 1.3 billion. When accounting for actual medical qualification the number of doctors further drops to 5.0 per 10,000 patients in India [

8]. In addition to recruiting and training more doctors, India could also utilize other well-trained paramedical professionals to address this major challenge of healthcare provision.

In 2008, India started granting PharmD degrees for pharmacy students who completed six years of college education and clinical training. This was an important step in enabling clinical pharmacists to improve patient care, however, pharmacists continue to be underutilized members of healthcare teams, simply dispensing drugs instead of working with doctors to optimize patient therapy to improve patient outcome and quality of life.

Currently, in India just like in the US 30 years ago, there is a lack of awareness about how pharmacists can contribute to improving patient healthcare outcomes. The “Asheville studies” demonstrated the role of pharmacists in improving patient outcomes, while reducing healthcare costs in the US [

9]. The results were so impressive that the American Pharmacy Association (APhA) foundation launched a “ten-cities diabetes challenge,” resulting in positive outcomes from pharmacist intervention and led Medicare to start payments for an annual prescription review by a pharmacist.

More recently pharmacist interventions have led to better patient outcomes in developing countries such as South Africa [

10] and Pakistan [

11]. They have led to positive impacts on improving medication adherence in COPD [

12] as well as medication error reporting [

14]. However, to the best of our knowledge this would be the first randomized controlled intervention study on the impact of a pharmacist intervention on any disease management in India.

2. Materials and Methods

Setting – Outpatient pharmacy of a tertiary care hospital in the state of Andhra Pradesh, South India.

Participants - Patients with known and de-novo diagnosis of hypertension using at least one antihypertensive drug and hypertension not under control as well as patients self-identifying as hypertensives were invited to participate in this study.

Inclusion criterion – Adults above 25 years of age of both genders who are currently being treated for hypertension and agreed to provide signed informed consent to participate in this study.

Exclusion criterion – Pregnant, children, cancer, mentally impaired and legally restricted patients. Patients with renal disorders like acute or chronic kidney disease, Pre-eclampsia, oedema and patients who were not willing to participate in the study.

Study Protocol – Patients providing written informed consent were randomly assigned to either the Non-Intervention [NI] or Intervention [I] group. For the non-intervention group, patients were given their prescribed drug(s) with simple instructions on how often to take it.

In the intervention group, PharmD interns counseled each patient in private, educating them on life-style modifications that could help control blood pressure and various long-term consequences of uncontrolled blood pressure. PharmD interns also provided patients with drug monographs, patient information leaflets on hypertension management and added auxiliary labels onto their filled prescriptions as well as weekly pill organizers - none of this is a standard of practice in India.

Patients in both non-intervention and intervention groups were seen on a monthly basis for the following three months by PharmD interns, and blood pressure was measured for all the patients in both groups. In the non-intervention group, the interns only measured and recorded the patients’ blood pressure and pharmacists dispensed them the next month’s supply of medications. Whereas, in the invention group, each subsequent visit provided the opportunity for the intern and the pharmacist to assess the patients’ medication adherence, lifestyle modifications, and provide additional counseling to reinforce the importance of blood pressure control. The last visit of Phase 1 of the study was 3 additional months later (6 months after the beginning of the study), during which the interns took a 5th and final blood pressure measurement for phase 1. In phase 1 - no pharmacist directed dosage adjustments were made.

There was a three-month gap between the patients’ 4th and 5th visits for Phase 1 of the study. The positive impact of pharmacist counseling on the intervention group was so significant that we were ethically bound to offer the Pharm-D intern intervention to the “non-intervention” group patients from the Phase 1 study. Thus, for Phase 2, only the 90 patients in the Phase 1 “non-intervention” group were asked and they all agreed to participate. No patient from the “intervention” group of Phase 1 was followed in Phase 2. In Phase 2, the formerly non-intervention group were provided the same monthly counseling as the Phase 1 intervention group, and their blood pressure was measured after 3 more months (6th visit: 9 months after the beginning of the study) and 6 months (7th visit: 1 year after the beginning of the study). During this Phase 2 portion of the study – pharmacist recommended, and physician approved drug and dosage adjustments were also made on 49 patients.

Statistical Analysis/Data Analysis

The non-intervention and intervention groups were compared to ascertain that they were not very different from each other at the start of the study. The ages of the participants in the two groups were compared using two-sample t-test and a chi-square test was used to compare the numbers of males and females.

The SBP and DBP values were not normally distributed. Therefore, non-parametric methods were used for comparison of blood pressure values. The median and interquartile ranges are presented as the central tendency throughout the manuscript. The non-intervention and intervention in phase-1 were compared using the two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

3. Results

Phase 1

Demographic characteristics in the two groups resulting from randomized enrollment is shown in

Table 1. In the non-intervention group there were 30 females, and 60 males compared to 41 females and 49 males in the intervention group. The average age of the patients in the NI and I groups were comparable 61.3±10.8 and 62.1±10.1 (p=0.64). The median SBP / DBP blood pressure during the first visit in the non-intervention group was 145 (139,155) / 87 (80,90) and the intervention group was 140 (130,150)/ 80 (80,90). While the SBP and DBP levels in the intervention group were lower, the difference was not statistically significant (P-values comparing SBP and DBP across groups were 0.06 and 0.57, respectively). At the first visit 1.1% of patients in the non-intervention and 3.3% of patients in the intervention group were normotensive with SBP<120 and DBP< 80.

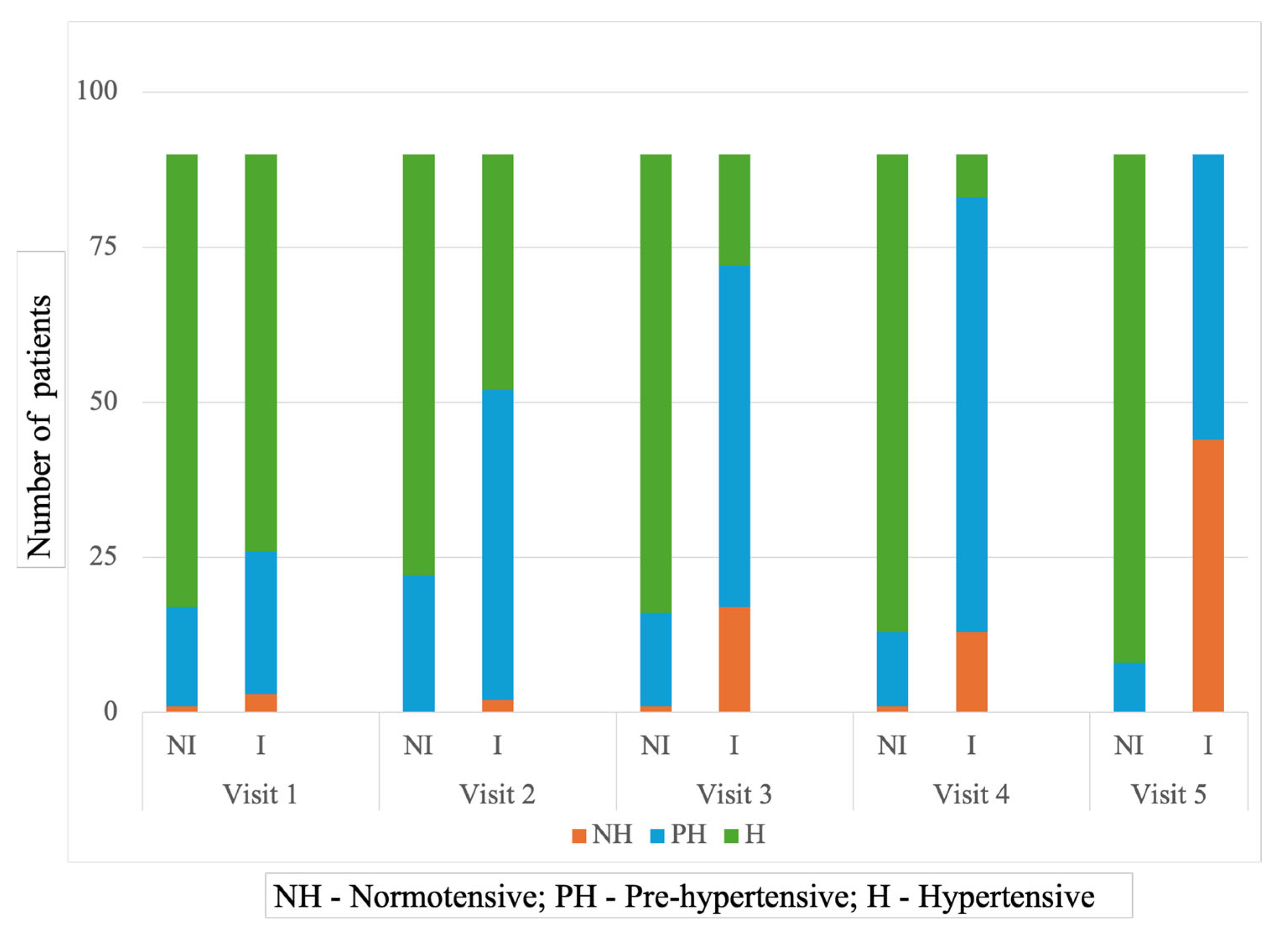

Figure 1 displays the distribution of patients in each blood pressure category across outpatient visits in the two experimental groups. While the hypertensive distribution of patients in the two groups during the first visit was comparable, there was a remarkable difference in that distribution during the 5th visit – with 0 [0%] patients in the non-intervention group compared to 44 [48.8%] patients in the intervention group achieving normotensive status.

It is also interesting to note that with each succeeding visit the number of hypertensive patients in the intervention group decreased gradually with a corresponding increase in the number of pre-hypertensives, followed by normotensives. On the other hand, most patients in the non-intervention group continue to be categorized as hypertensive throughout Phase 1 of the study [

Figure 1].

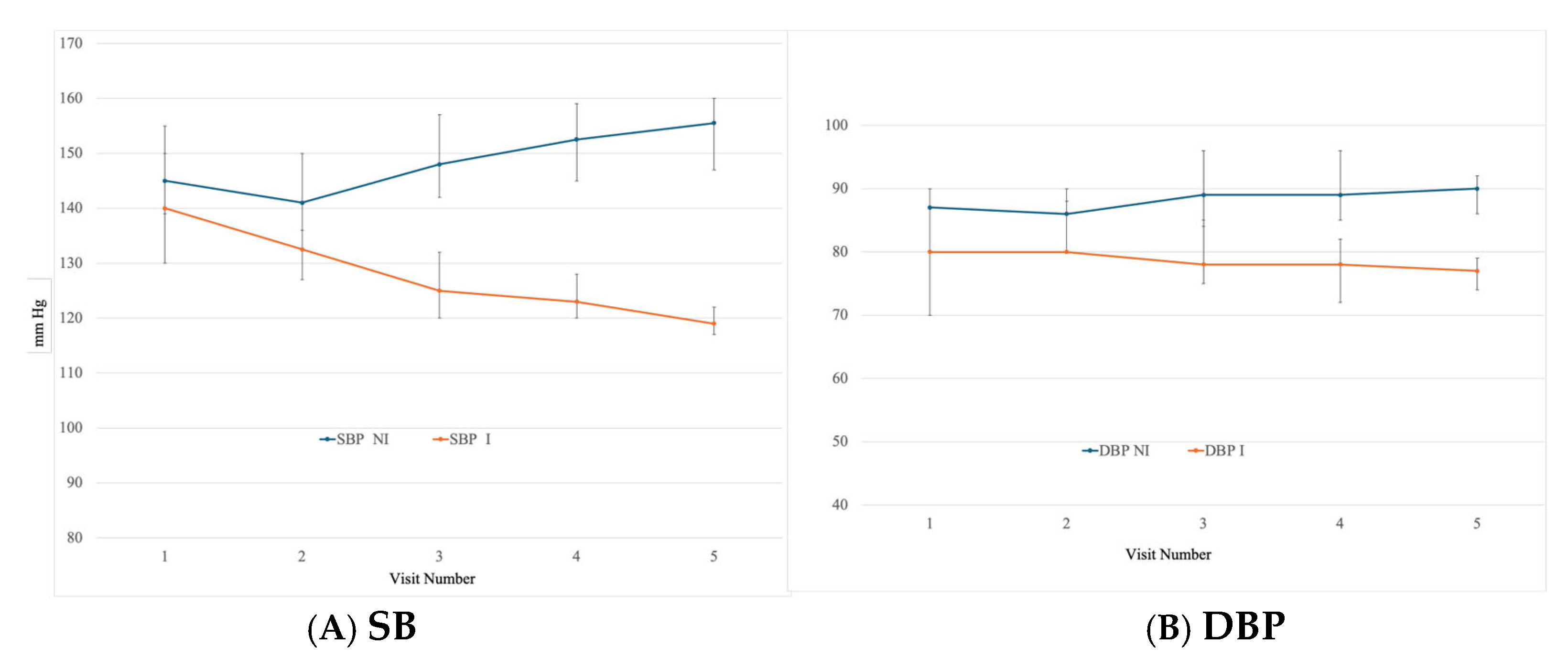

The median drop in SBP and DBP values as shown in

Figure 2A and

Figure 2B following pharmacist intervention supports this conversion of hypertensive to normotensive patients following intervention. In the intervention group, SBP and DBP values fell from 140 to 119 and 80 to 77, respectively, between 1st and 5th visit. Whereas in the non-intervention group, mean SBP value increased from 145 to 155.5 and DBP from 87 to 90. At the conclusion of the phase 1, the reduction in SBP and DBP in the intervention group, compared to the non-intervention group was highly significant with P < 0.001.

At the start of the 2

nd phase of this hypertension project, the pharmacist-intervention was provided to all 90 patients comprising the “non-intervention group” of Phase 1. The SBP (IQR) and DBP (IQR) decreased from 155.5 (147, 160) and 90 (86, 92), respectively during the 5

th visit to 126.5 (122, 132) and DBP 81 (78, 83), respectively in the 6

th visit – 3 months later, following intern and pharmacist interventions. In phase 2, in addition to all the counseling that was provided in phase 1, 64 pharmacist recommended changes in drug and dosage were accepted by the physician [

Table 2].

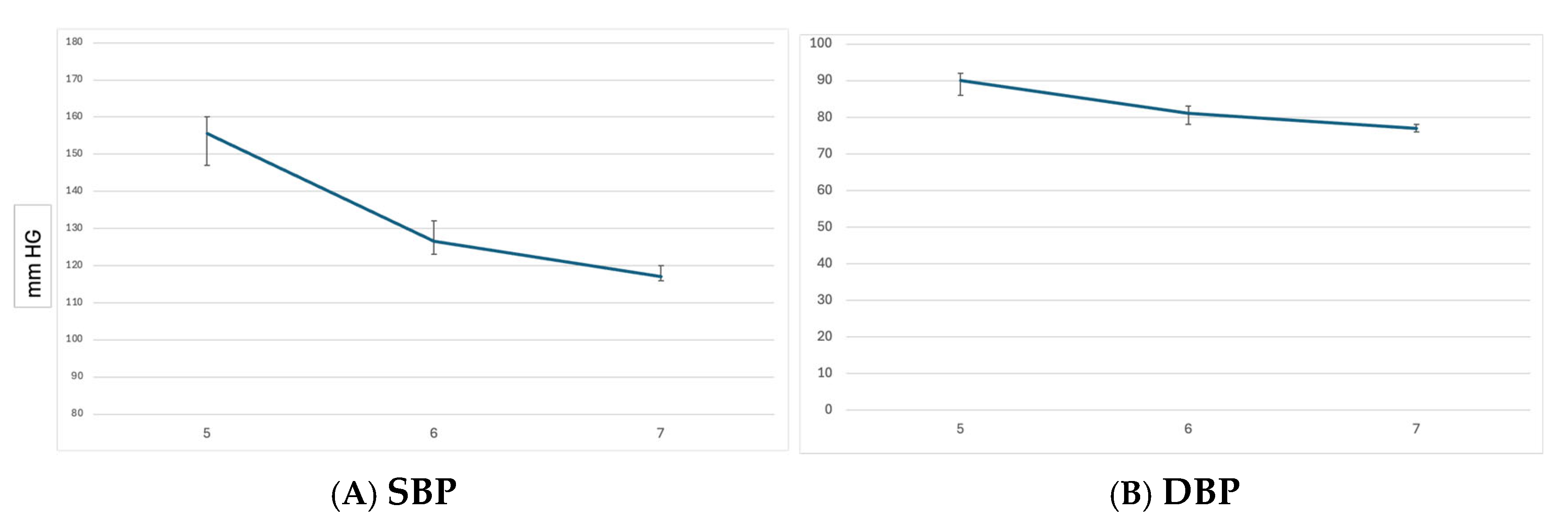

There was a further reduction in the SBP and DBP at the 7

th visit, which was the conclusion of the study. At 7

th visit, 6 months after initiation of Phase 2, the patients who were formerly in the Non-intervention group had a median SBP (IQR) of 117 (116, 120) and median DBP (IQR) of 77 (76, 78) [

Figure 3A & 3B].

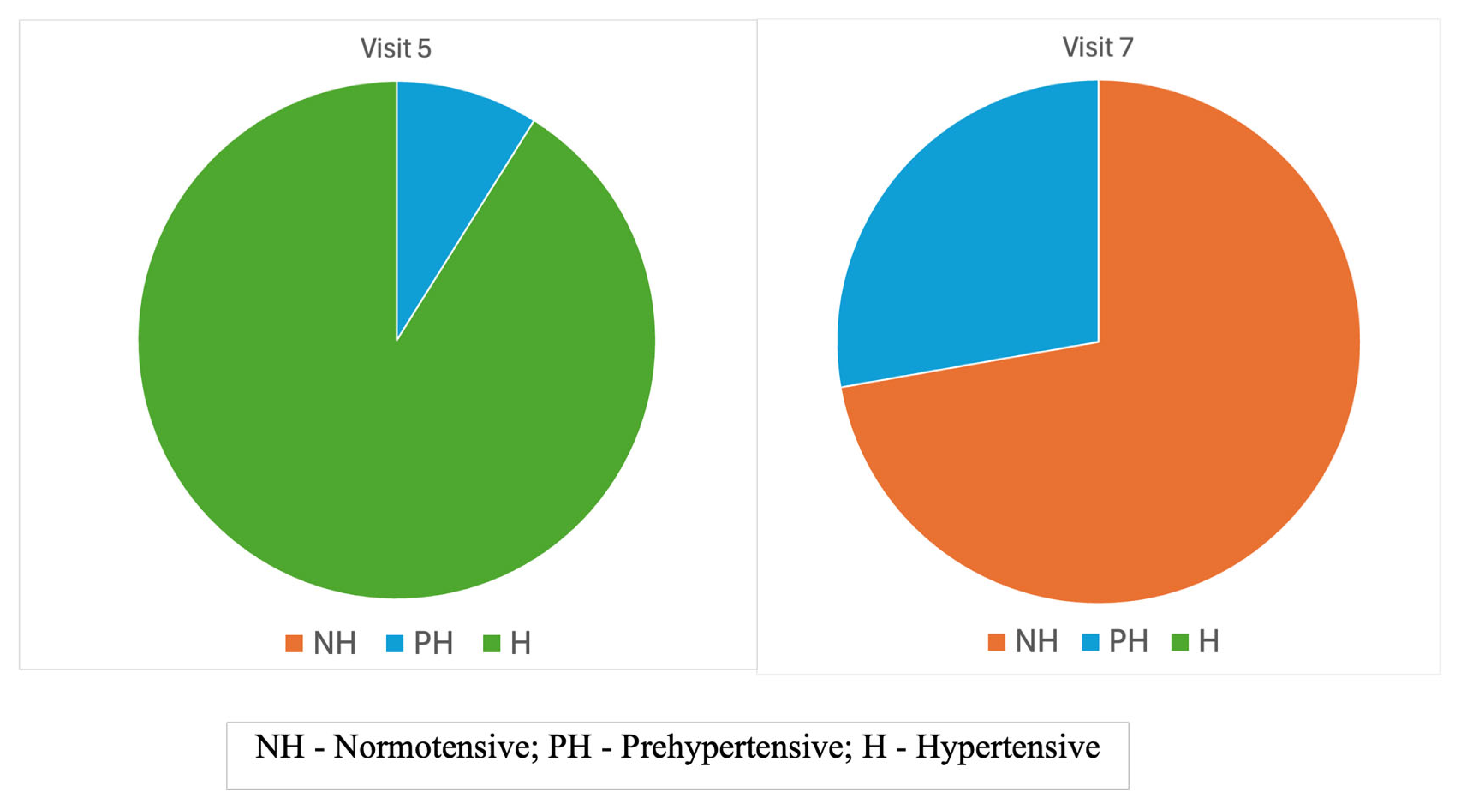

In this final visit of Phase 2, 65 patients [72.2%] were normotensive, 25 patients [28.8%] were pre-hypertensive and not a single patient was hypertensive, in contrast to 82 [91.1%] patients being hypertensive at the beginning of Phase 2 [visit 5] [

Figure 4].

Both Phase 1 and Phase 2 of our study clearly demonstrate the benefits of pharmacist intervention on patient’s blood pressure control in an Indian outpatient setting.

4. Discussion

Pharmacists are the most underutilized healthcare professionals around the world [

14,

15], and in developed countries, there have been efforts to increase pharmacists’ role in patient care. Unfortunately, in countries like India, where pharmacists could make an even greater impact – due to limited access to other healthcare professionals - such a recognition is still lacking. The purpose of this investigation was to demonstrate the impact a pharmacist intervention could make on one of the most pressing health problems in India – hypertension.

In other countries, numerous randomized clinical trials of pharmacist-led interventions have demonstrated improved hypertension outcomes [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Pharmacist intervention in the Ying Le et al. [

16] study done in China involved a monthly review of medications, patient education, and medication adjustment advice to medical doctors over 6 months. Compared to the non-intervention group, which was given basic patient education about hypertension (a service not provided in India), a significantly higher percentage of pharmacist intervention patients [60.7% vs 40.9%, P<0.01] at 6 months had their blood pressure under control. The higher percentage of patients with better blood pressure control in the Chinese patient population may be attributed to the “basic patient education” available to Chinese patients even in the non-intervention group. Our SBP drop of 21 mm Hg in Phase 1 of our study is comparable to a drop in SBP of 18.3 mm Hg that was reported in the AlbertaCanada Clinical Trial in Optimizing Hypertension [RxACTION] [

19], which was conducted between 2009-2013. In Phase 2 of our study, there was an even larger drop in SBP of 31 mm, which may be explained by the more aggressive intervention that involved dosage adjustments by pharmacists, which resulted in 64 drug and dosage recommendations that were all accepted by physicians.

Pharmacist intervention in the US veterans population [

2]] led to a decrease of 8 mm/4 mm in diabetic patients and 14 mm/5 mm in non-diabetic patients over a six month period and both the decreases were statistically significant. A pharmacist-led intervention on health outcomes in hypertension management at community pharmacies in Nigeria found improved behavior, attitude and adherence in the intervention group but found no change in health status, interestingly in this study they never actually measured blood pressure [

21]. A pharmacist intervention study from Portugal [

22] reported better blood pressure control in the intervention group than the non-intervention group. In a study reported from France [

23] 61.7% of the patients in the intervention group reached their therapeutic goals compared to 33.3% of patients in the non-intervention group.

To the best of our knowledge no randomized controlled study on the impact of pharmacist intervention on hypertension or any other disease has been reported from India. Few non-drug, non-pharmacist involved RCT on hypertension management studies have been reported from India. In a small study with 40 individuals randomly assigned to control or home-based isometric handgrip (IHG) training, after 8 weeks there was a significant reduction in blood pressure and pulse rate in the IHG group [

24].

In another randomized control study involving non-pharmacological treatment of hypertension with physical exercise, salt intake reduction and yoga, all treatments showed significant decrease - 5.3/6.0; 2.5/2.0 and 2.3/2.4 in blood pressure [

25]. As the patients in the intervention group in our study were advised on lifestyle modifications - including exercise and importance of DASH diet, those could have also contributed to the positive outcome in our study.

Even in countries like the US, where healthcare is more advanced, only 25% of the patients with hypertension have their blood pressure fully under control. Dixon et al. [

26], reported on cost-effectiveness analysis of pharmacist intervention from the Alabama Clinical Trial in Optimizing Hypertension [

19] and found that a 50% uptake of a pharmacist prescribing intervention would improve blood pressure control, saving

$1.137 trillion and an estimated 30.2 million life-years over a 30-year period. Schultz et al. [

27] economic analysis of hypertension management with and without medication therapy management resulted in incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of

$38,798 gain per quality-adjusted life year, and they concluded that the current reimbursement rate of pharmacist services is inadequate.

Indian CGP guideline IGH-IV recommends two separate targets for BP control depending on age. For patients less than 65 years-old, the recommended target is 120-130/70-80 and for patients over 65 it is <140/90 [

28]. Based on the global burden of disease estimates, cardiovascular disease [CVD] death rate in India at 272 is higher than the global average of 235 deaths per 100,000 population [

5]. In India, CVD deaths occur at an earlier age than Western countries [

29]. Based on a meta-analysis of 123 studies that included 612,815 patients, every 10 mm drop in SBP significantly reduces risk of various cardiovascular diseases, resulting in a 13% reduction in all-cause mortality [

30]. Therefore, to the extent possible, it would be better to target and aspire for better blood pressure control for each Indian patient.

Even though it is now clearly evident that non-communicable chronic health conditions like CVD are major public health problems in India [

6], very little has been done to address it [

31]. Our current study clearly indicates that inclusion of clinically trained pharmacists that are being graduated from over 200 pharmacy colleges in India could be integral parts of Indian healthcare teams, and integrating pharmacists in effective management of disease conditions may be a hugely significant, cost-effective step towards improving CVD outcomes in India.

5. Conclusions

Our study clearly demonstrates the value of pharmacist intervention in improving patient outcomes for hypertension management in India and is consistent with reports from other parts of the world where similar observations have been reported.

Presentations - An abstract for Phase 1 study was presented at 82nd FIP conference in Cape town, South Africa in September 2024 and from Phase 2 study at the APhA annual meeting in Nashville, TN, March 2025.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fulbright-Nehru award to Dr. Sekar.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Research investigation approval was obtained from both the University of Findlay – 1678 and from the Indian Hospital Institutional Ethics Committee – ECR/81/INST/AP/2013/RR/2019

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Original data presented in this publication can be requested by sending an email to M. Chandra Sekar, sekar@findlay.edu. Please specify the reason for which the requested data will be used.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the University of Findlay and Aster Ramesh Hospitals for their support in carrying out this project, Vignan Pharmacy College Interns for data collection and Padmini Sekar for providing the statistical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

▪ I – Intervention

▪ NI – Non-intervention

▪ SBP – Systolic blood pressure

▪ DBP – Diastolic blood pressure

▪ IQR – Interquartile range

References

- Beaney T, Schutte AE, Stergiou GS, et al. May Measurement Month 2019: The Global Blood Pressure Screening Campaign of the International Society of Hypertension. Hypertension. 2020 Aug;76(2):333-341. Epub 2020 May 18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varghese JS, Venkateshmurthy NS, Sudharsanan N, et al. Hypertension Diagnosis, Treatment, and Control in India. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(10):e2339098. [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. World Development Indicators. Accessed January 6, 2024. https://www.who.int/india/health-topics/hypertension.

- Gupta, R, Gaur, K, Ahuja, S. et al. Recent studies on hypertension prevalence and control in India 2023. Hypertens Res 47, 1445–1456 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Mills, KT, Stefanescu, A, He, J. The global epidemiology of hypertension. Nat Rev Nephrol 16, 223–237 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Srinath Reddy K, Shah B, Varghese C, Ramadoss A. Responding to the threat of chronic diseases in India. Lancet. 2005;366:1744–1749. [CrossRef]

- Madanian S, Parry DT, Airehrour D, Cherrington M. mHealth and big-data integration: promises for healthcare system in India: BMJ Health & Care Informatics 2019;26:e100071.

- Karan A, Negandhi H, Kabeer M, Zapata T, et. al. Achieving universal health coverage and sustainable development goals by 2030: investment estimates to increase production of health professionals in India. Hum Resour Health. 2023 Mar 2;21(1):17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cranor CW, Christensen DB. The Asheville Project: factors associated with outcomes of a community pharmacy diabetes care program. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash). 2003 Mar-Apr;43(2):160-72. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rampamba EM, Meyer JC, Helberg EA, Godman B. Empowering Hypertensive Patients in South Africa to Improve Their Disease Management: A Pharmacist-Led Intervention. J Res Pharm Pract. 2019 Dec 27;8(4):208-213. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Javaid Z, Imtiaz U, Khalid I, et al. A randomized control trial of primary care-based management of type 2 diabetes by a pharmacist in Pakistan. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019 Jun 24;19(1):409. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abdulsalim S, Unnikrishnan MK, Manu MK, et. al. Structured pharmacist-led intervention programme to improve medication adherence in COPD patients: A randomized controlled study. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2018 Oct;14(10):909-914. Epub 2017 Oct 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalasani SH, Ramesh M, Gurumurthy P. Pharmacist-Initiated Medication Error-Reporting and Monitoring Programme in a Developing Country Scenario. Pharmacy (Basel). 2018 Dec 14;6(4):133. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kibicho J, Pinkerton SD, Owczarzak J, et.al. Are community-based pharmacists underused in the care of persons living with HIV? A need for structural and policy changes. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2015 Jan-Feb;55(1):19-30. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- The Hill. https://thehill.com/blogs/ballot-box/278414-the-most-overtrained-and-under-utilized-profession-in-america/ Accessed January 4, 2024.

- Li Y, Liu G, Liu C, et. al. Effects of Pharmacist Intervention on Community Control of Hypertension: A Randomized Controlled Trial in Zunyi, China. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2021 Dec 21;9(4):890-904. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Santschi V, Chiolero A, Colosimo AL, et. al. Improving blood pressure control through pharmacist interventions: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014 Apr 10;3(2):e000718. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Victor RG, Lynch K, Li N, et. al. A Cluster-Randomized Trial of Blood-Pressure Reduction in Black Barbershops. N Engl J Med. 2018 Apr 5;378(14):1291-1301. Epub 2018 Mar 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tsuyuki RT, Houle SK, Charrois TL, et. al. Randomized Trial of the Effect of Pharmacist Prescribing on Improving Blood Pressure in the Community: The Alberta Clinical Trial in Optimizing Hypertension (RxACTION). Circulation. 2015 Jul 14;132(2):93-100. Epub 2015 Jun 10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker CP, Cunningham CL, Carter BL, Vander Weg MW, Richardson KK, Rosenthal GE. A mixed-method approach to evaluate a pharmacist intervention for veterans with hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014 Feb;16(2):133-40. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ayogu EE, Yahaya RI, Isah A, Ubaka CM. Effectiveness of a pharmacist-led educational intervention on health outcomes in hypertension management at community pharmacies in Nigeria: A two-arm parallel single-blind randomized controlled trial. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2023 Feb;89(2):649-659. Epub 2022 Sep 10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgado M, Rolo S, Castelo-Branco M. Pharmacist intervention program to enhance hypertension control: a randomised controlled trial. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011 Feb;33(1):132-40. Epub 2011 Jan 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Delage C, Lelong H, Brion F, Blacher J. Effect of a pharmacist-led educational intervention on clinical outcomes: a randomised controlled study in patients with hypertension, type 2 diabetes and hypercholesterolaemia. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2021 Nov;28(Suppl 2):e197-e202. Epub 2021 Jun 28. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Punia S, Kulandaivelan S. Home-based isometric handgrip training on RBP in hypertensive adults-Partial preliminary findings from RCT. Physiother Res Int. 2020 Jan;25(1):e1806. Epub 2019 Aug 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian H, Soudarssanane MB, Jayalakshmy R, et. al. Non-pharmacological Interventions in Hypertension: A Community-based Cross-over Randomized Controlled Trial. Indian J Community Med. 2011 Jul;36(3):191-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dixon DL, Johnston K, Patterson J, et. al. Cost-Effectiveness of Pharmacist Prescribing for Managing Hypertension in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Nov 1;6(11):e2341408. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schultz BG, Tilton J, Jun J, et.al. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of a Pharmacist-Led Medication Therapy Management Program: Hypertension Management. Value Health. 2021 Apr;24(4):522-529. Epub 2021 Jan 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satheesh G, Dhurjati R, Balagopalan JP, et. al. Comparison of Indian clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension with the World Health Organization, International Society of Hypertension, American, and European guidelines. Indian Heart J. 2024 Jan-Feb;76(1):6-9. Epub 2024 Jan 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Joshi P, Islam S, Pais P, Reddy S, et. al. Risk factors for early myocardial infarction in South Asians compared with individuals in other countries. JAMA. 2007 Jan 17;297(3):286-94. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A, Anderson SG, et. al. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016 Mar 5;387(10022):957-967. Epub 2015 Dec 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabhakaran D, Jeemon P, Roy A. Cardiovascular Diseases in India: Current Epidemiology and Future Directions. Circulation. 2016 Apr 19;133(16):1605-20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).