Submitted:

14 May 2025

Posted:

15 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Literature Survey: An extensive review of 40 key publications from 2010–2025 on power measurement, estimation, and governance in data centers.

- Conceptual Framework: A synthesized model of hierarchical energy governance combining DVFS, server consolidation, and QoS strategies.

- Pilot Simulation Study: A mathematical simulation assessing the power-performance trade-offs of the proposed model in solar-constrained scenarios.

- Systems Proposal: A forward-looking architectural integration of SDN and AI/ML for predictive and autonomous energy governance.

- Future Outlook: Strategic recommendations for implementing intelligent, renewable-aware infrastructure in next-generation data centers.

2. Literature Survey

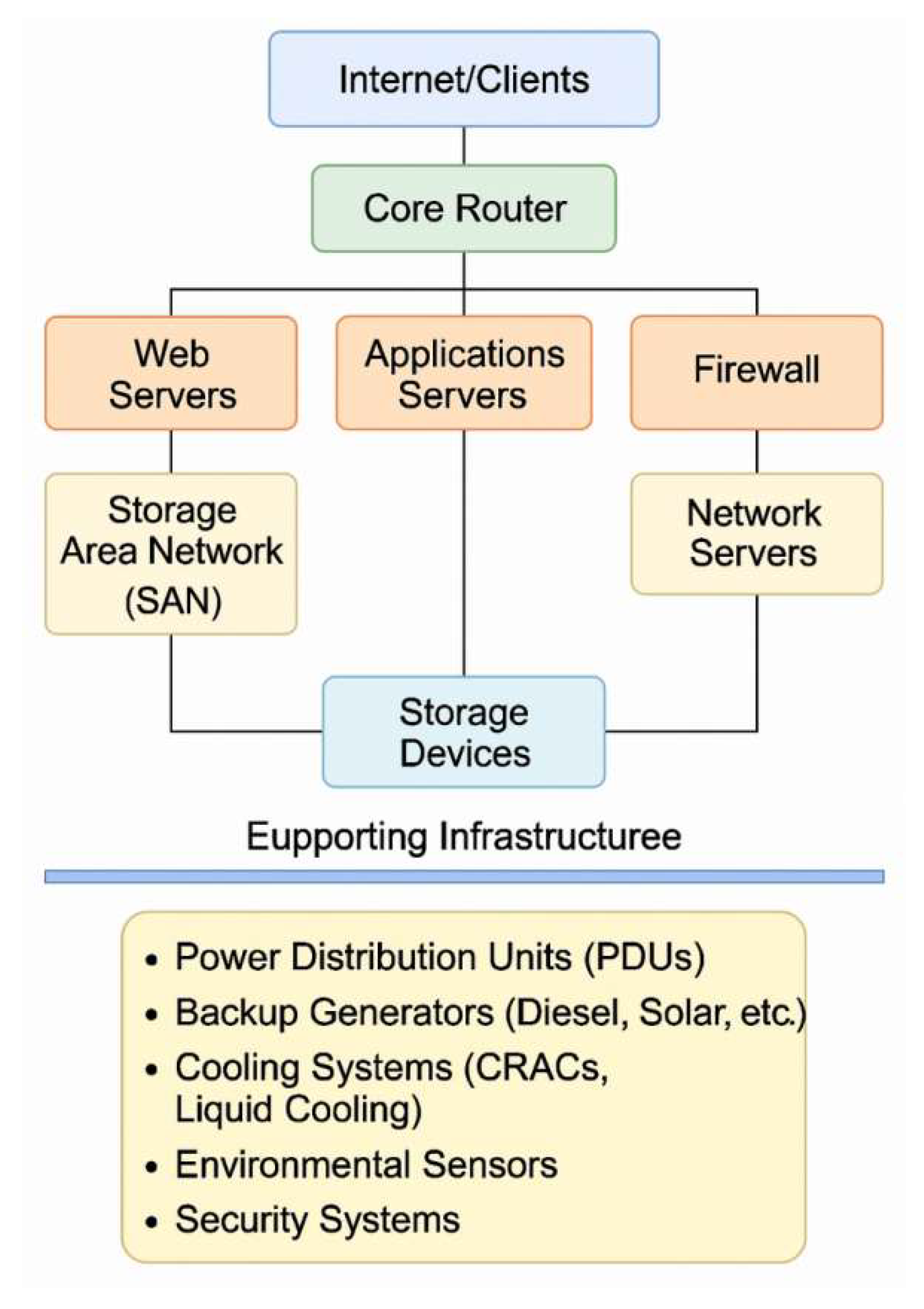

3. Data Centers — Architecture, Components, and Energy Challenges

-

IT Equipment:

- ○

- Servers: Compute nodes hosting applications, databases, and services.

- ○

- Storage Devices: Disk arrays, SAN/NAS devices storing vast amounts of data.

- ○

- Networking Gear: Switches, routers, and load balancers interconnecting internal and external systems.

-

Support Infrastructure:

- ○

- Power Systems: Uninterruptible power supplies (UPS), power distribution units (PDUs), and backup generators ensure continuous power delivery.

- ○

- Cooling Systems: Precision air conditioning, chilled water systems, and increasingly, advanced cooling methods such as liquid cooling to dissipate heat generated by IT equipment.

- ○

- Physical Security: Biometric scanners, surveillance systems, and fire suppression systems.

-

Management Systems:

- ○

- Monitoring Platforms: Environmental monitoring, power usage tracking, and workload management platforms optimize operational efficiency.

- Cooling infrastructure alone can consume around 40–50% of total energy.

- IT equipment (servers, storage, and networking) accounts for roughly 30–40%.

- Auxiliary systems (lighting, security) account for a small but non-negligible fraction.

- Over-provisioned servers operating at low utilization.

- Inefficient cooling architectures.

- Power losses during conversion and distribution.

- Virtualization: Consolidating workloads to fewer servers to reduce energy usage.

- Dynamic Resource Management: Using predictive analytics to scale resources based on demand.

- Free Cooling: Leveraging ambient air or water for cooling rather than relying solely on mechanical chillers.

- Renewable Energy Sources: Solar, wind, and hydroelectric power are increasingly being integrated.

- Advanced Materials: Innovations in server design, such as low-power chips and high-efficiency power supplies.

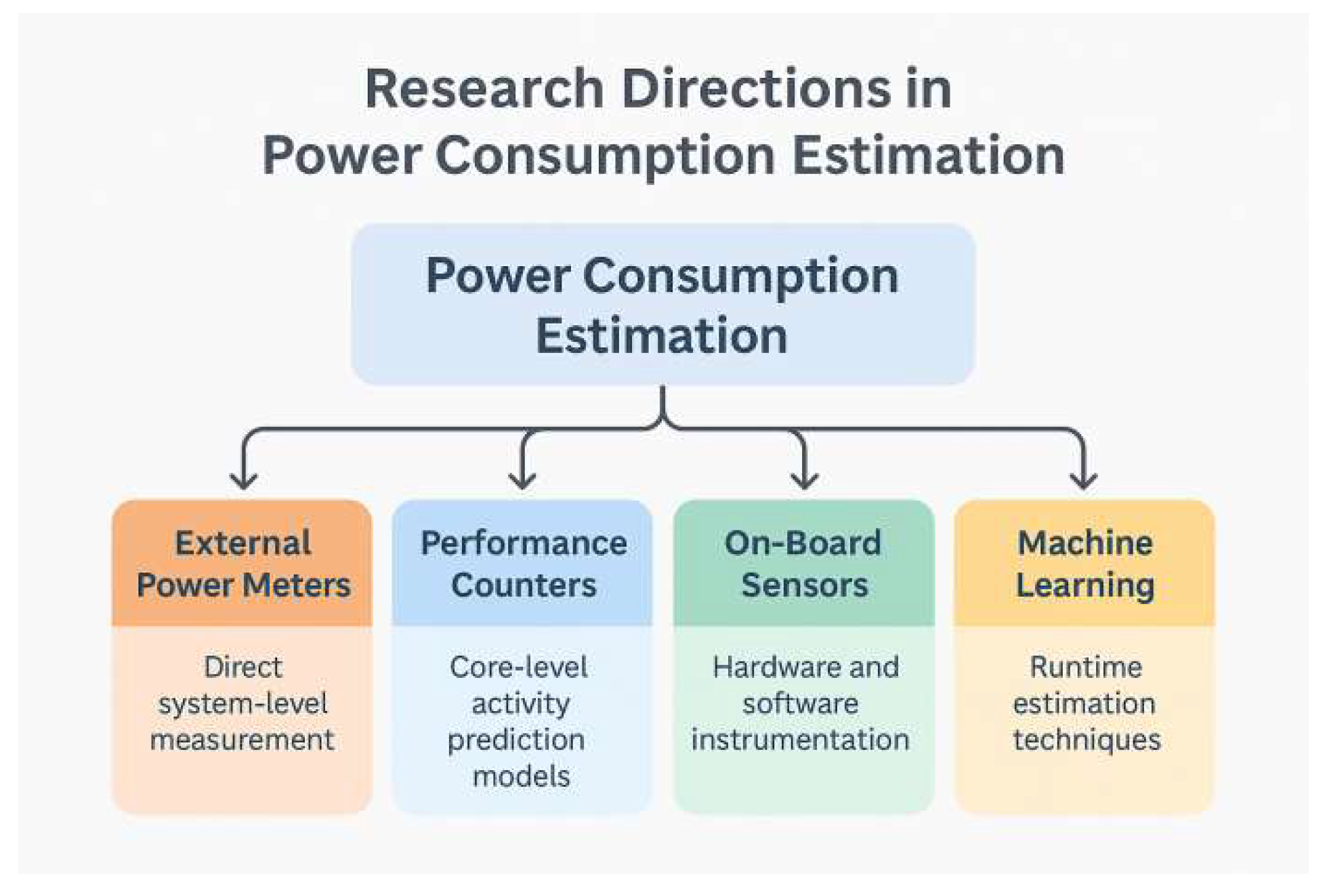

4. Examined Techniques for Enhancing Power Consumption

4.1. Dynamic Voltage and Frequency Scaling (DVFS)

4.2. Server Consolidation

4.3. Quality of Service (QoS) Degradation

- Reducing video streaming bitrates,

- Delaying batch analytics and non-urgent backups,

- Postponing system maintenance operations.

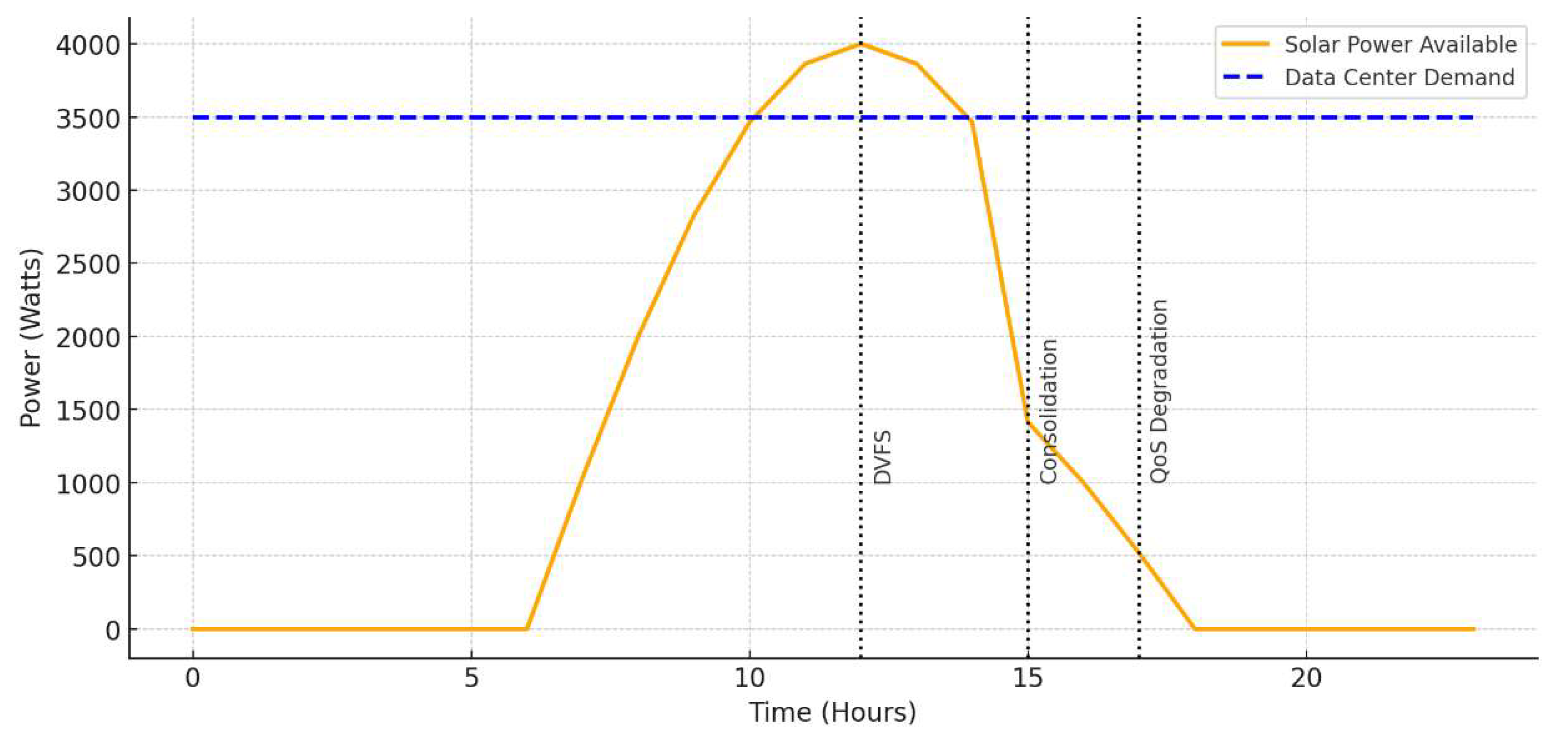

4.4. Multi-Stage Dynamic Governance Process

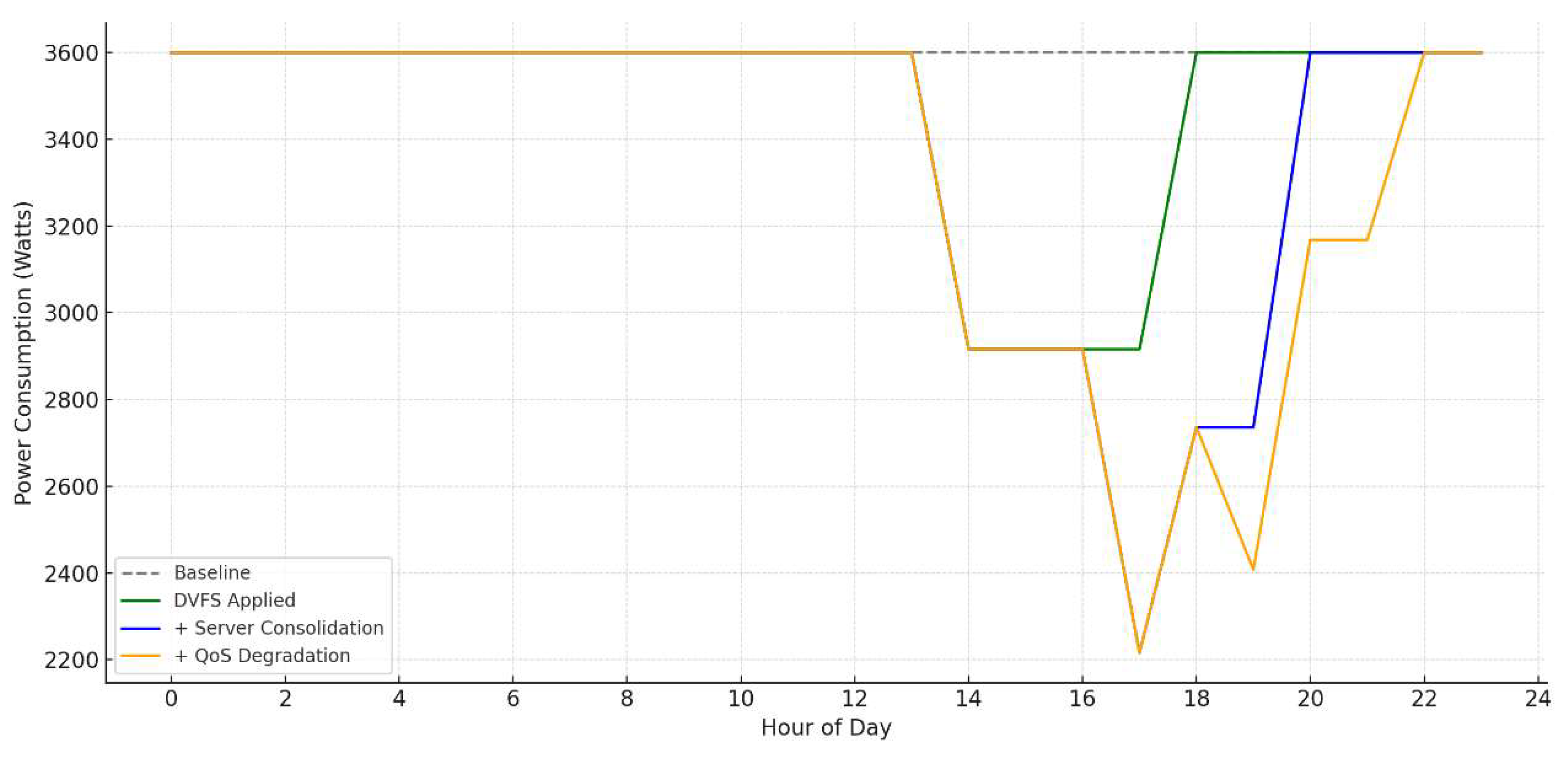

- Stage 1: Apply DVFS to reduce dynamic power.

- Stage 2: Initiate server consolidation to minimize idle energy.

- Stage 3: Engage selective QoS degradation to shed non-essential loads.

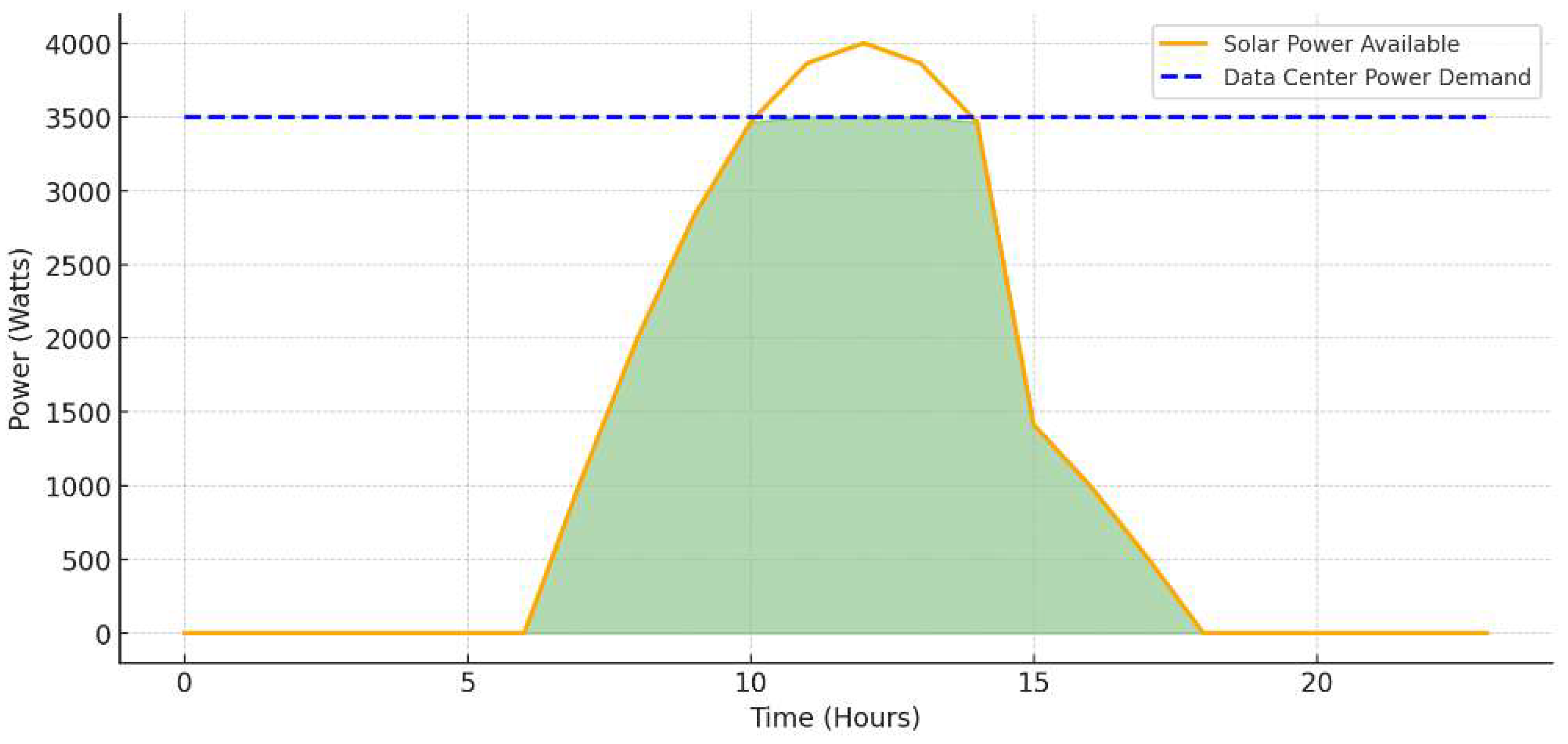

5. Solar-Powered System Planning for Data Centers

- -

- Peak Power Demand (kW): Determined by server load, cooling systems, and auxiliary infrastructure.

- -

- Daily Energy Consumption (kWh): Total energy required over 24 hours.

- -

- Solar Insolation: Average daily solar radiation at the location (kWh/m²/day).

- -

- Available Rooftop or Land Area: Determines how many solar panels can be installed.

- -

- Panel Efficiency and Derating Factor: Includes temperature loss, dust, wiring, and inverter losses.

- -

- Energy Storage Requirements: Batteries needed to supply power during non-sunlight hours or cloudy days.

- -

- Power Redundancy: Required to meet SLAs or Tier III/IV uptime expectations.

- -

- Hybrid Design Considerations: Integration with grid or diesel backup systems if full off-grid design is not feasible.

- PV Oversizing: Consider oversizing PV by 10–20% to account for degradation and future demand growth.

- Energy Shifting: Schedule non-critical workloads during peak solar hours.

- Hybrid Mode: Design with auto-switching to grid or diesel to meet Tier III uptime targets.

- Monitoring: Use IoT-based energy monitoring for real-time system performance.

6. Modeling and Simulation Methodology

- A mathematical model of energy consumption across IT and non-IT infrastructure.

- A simulation-based control algorithm to adapt workloads dynamically in response to power constraints.

- A multi-layer decision engine incorporating DVFS, Server Consolidation, and QoS Degradation strategies.

6.1. System Components and Model Variables:

- P_IT(t): power consumed by servers, storage, and network devices.

- P_cooling(t): cooling demand, approximated as a function of IT load.

- P_base(t): baseline auxiliary loads (e.g., lighting, UPS, monitoring).

- The IT component is further decomposed:

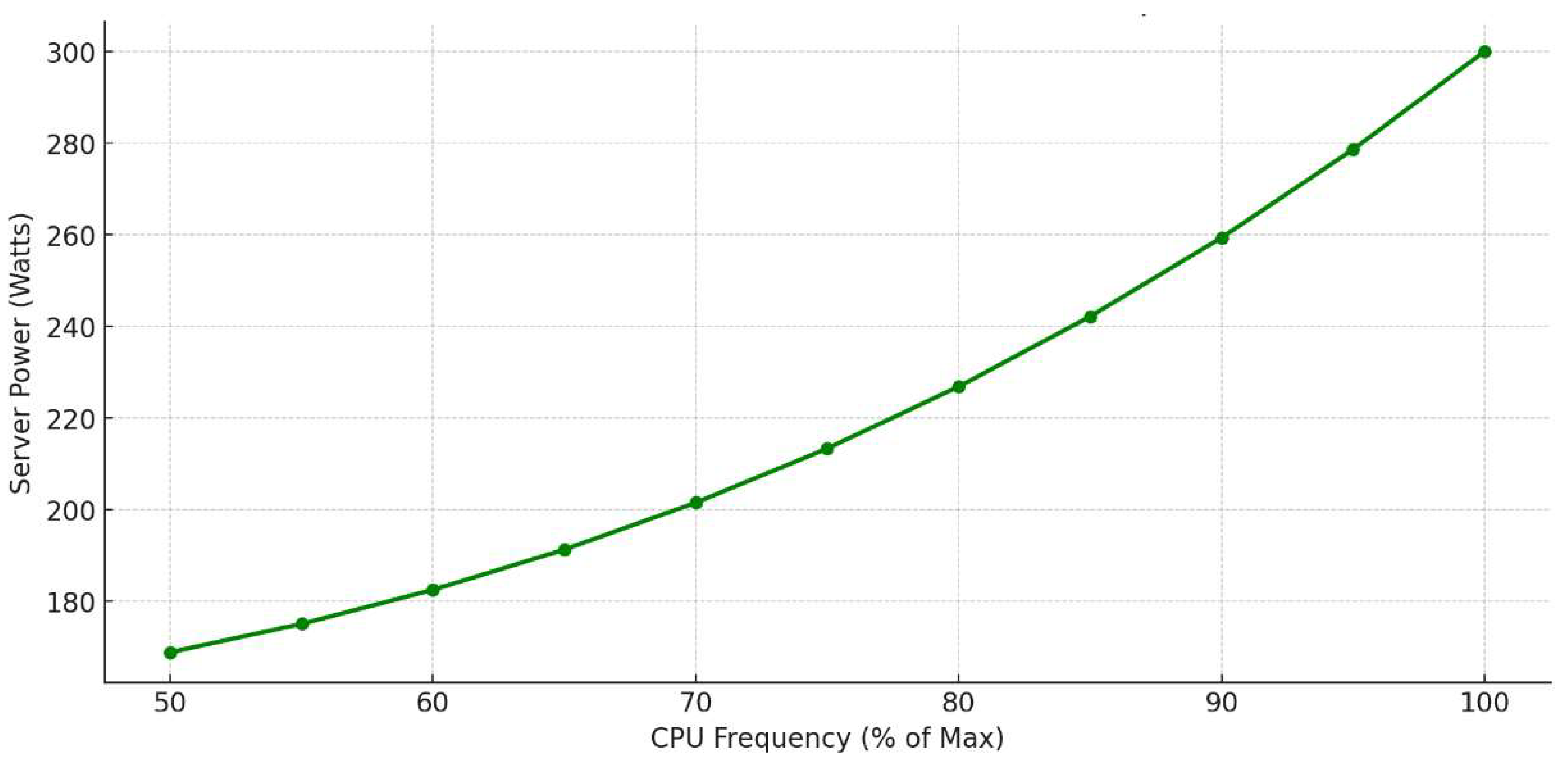

- f_i: CPU frequency

- u_i: CPU utilization

- P_CPU,i ∝ f_i³ * u_i

6.2. Solar Power and Constraint Modeling:

- I(t): solar irradiance (W/m²) at time t

- A: panel area

- η: panel efficiency

6.3. Layered Governance Control Logic:

6.4. Simulation Framework:

| Algorithm 1: Energy-Aware Governance in a Solar-Powered Data Center |

| Inputs: - solar_profile[t]: Forecasted solar irradiance (W/m²) for each hour t ∈ [0, 23] - battery_capacity: Max energy storage (Wh) - server_specs[i]: For each server i, including idle/load power, f_min, f_max - workload_profile[t]: Incoming workload intensity and SLA targets - thresholds: θ1 (DVFS trigger), θ2 (consolidation), θ3 (QoS degradation) Outputs: - Energy usage logs - SLA compliance metrics - Server state matrix (frequency, power state, workload mapping) Initialize: - For each t in 24-hour cycle: - Update solar_input[t] = solar_profile[t] × panel_area × efficiency - Update battery_level from previous time step - Assign workloads to servers For each time step t from 0 to 23: 1. Compute Total IT Power (P_IT): For each active server i: - Determine current utilization u_i and frequency f_i - Calculate P_CPU_i = k * (f_i)^3 * u_i - Sum all P_CPU_i + P_mem_i + P_net_i → P_IT 2. Compute Cooling Power: P_cooling = cooling_factor × P_IT 3. Calculate Total Power Demand: P_total = P_IT + P_cooling + P_auxiliary 4. Determine Available Energy: P_available = solar_input[t] + battery_level[t] ΔP = P_available - P_total 5. Apply Energy Governance Logic: IF ΔP ≥ 0: Maintain current operation (no action) ELSE IF 0 > ΔP ≥ θ1: // Layer 1: DVFS FOR each server i: Reduce f_i = f_i × β (where β ∈ [0.7, 0.9]) Recompute P_CPU_i and update P_total ELSE IF θ1 > ΔP ≥ θ2: // Layer 2: Server Consolidation - Migrate workloads from low-utilization servers - Turn off idle servers - Reassign load while ensuring SLA-critical services remain on - Update cooling and P_total ELSE IF ΔP < θ2: // Layer 3: QoS Degradation - Identify non-critical tasks (e.g., batch, streaming) - Defer or throttle these tasks - Optionally drop frame rates or use lower resolution - Update workload map and P_total 6. SLA Check: - For each service s: - Compute latency_s[t], throughput_s[t] - Check against SLA_s thresholds - Record violations and service impact logs 7. Update battery_level: IF ΔP > 0: Charge battery (if not full) ELSE: Discharge battery (if available) 8. Log all results: - Energy usage breakdown (servers, cooling, storage) - Governance actions taken - SLA compliance report - Server state and frequency maps Repeat for all t ∈ [0, 23] |

6.5. Validation Approach:

- -

- Simulated vs. theoretical power consumption at full load and idle.

- -

- SLA degradation under stress compared to industry benchmarks.

- -

- Consistency of energy trends with solar generation profiles from real deployments.

7. Results and Performance Analysis

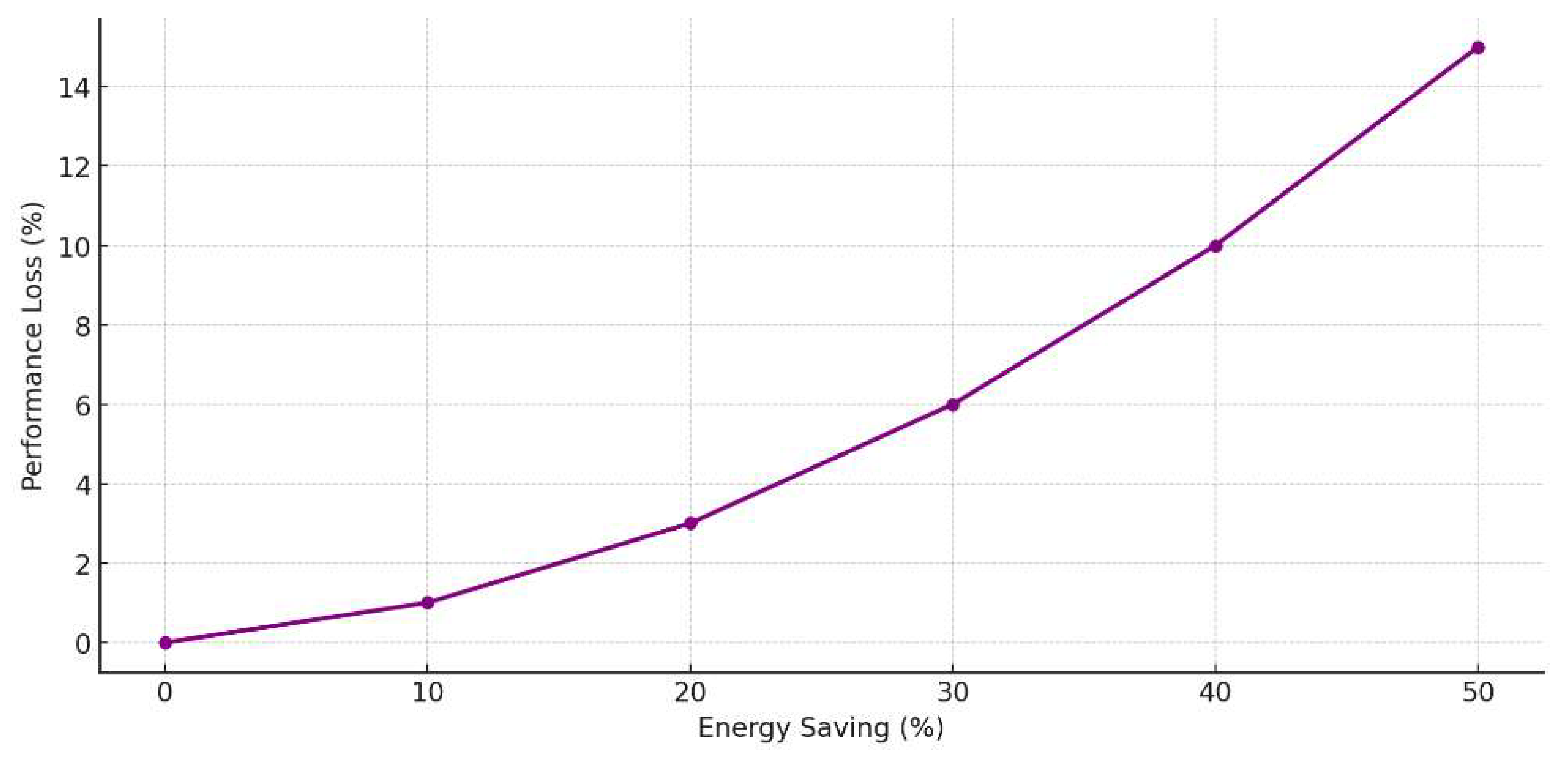

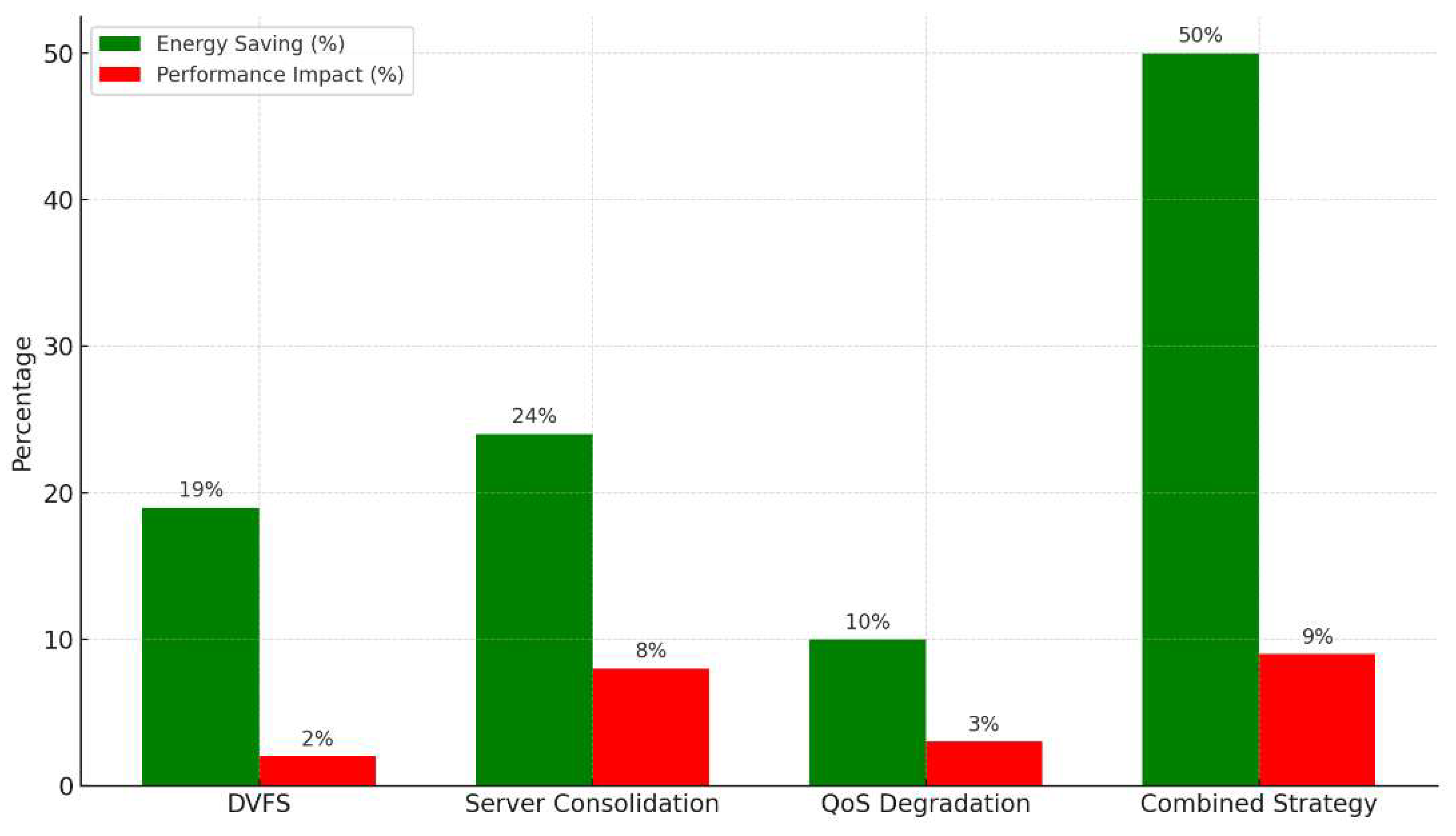

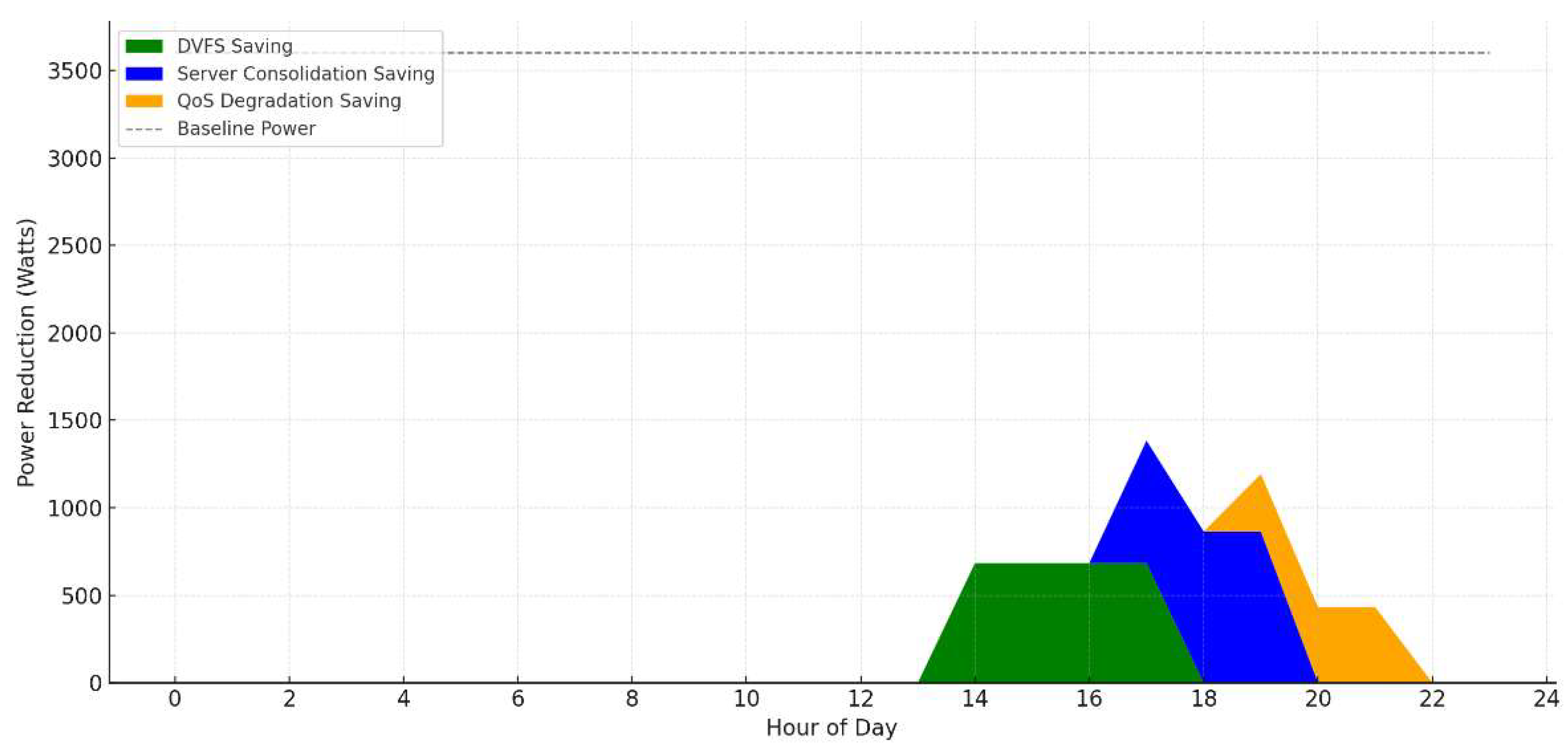

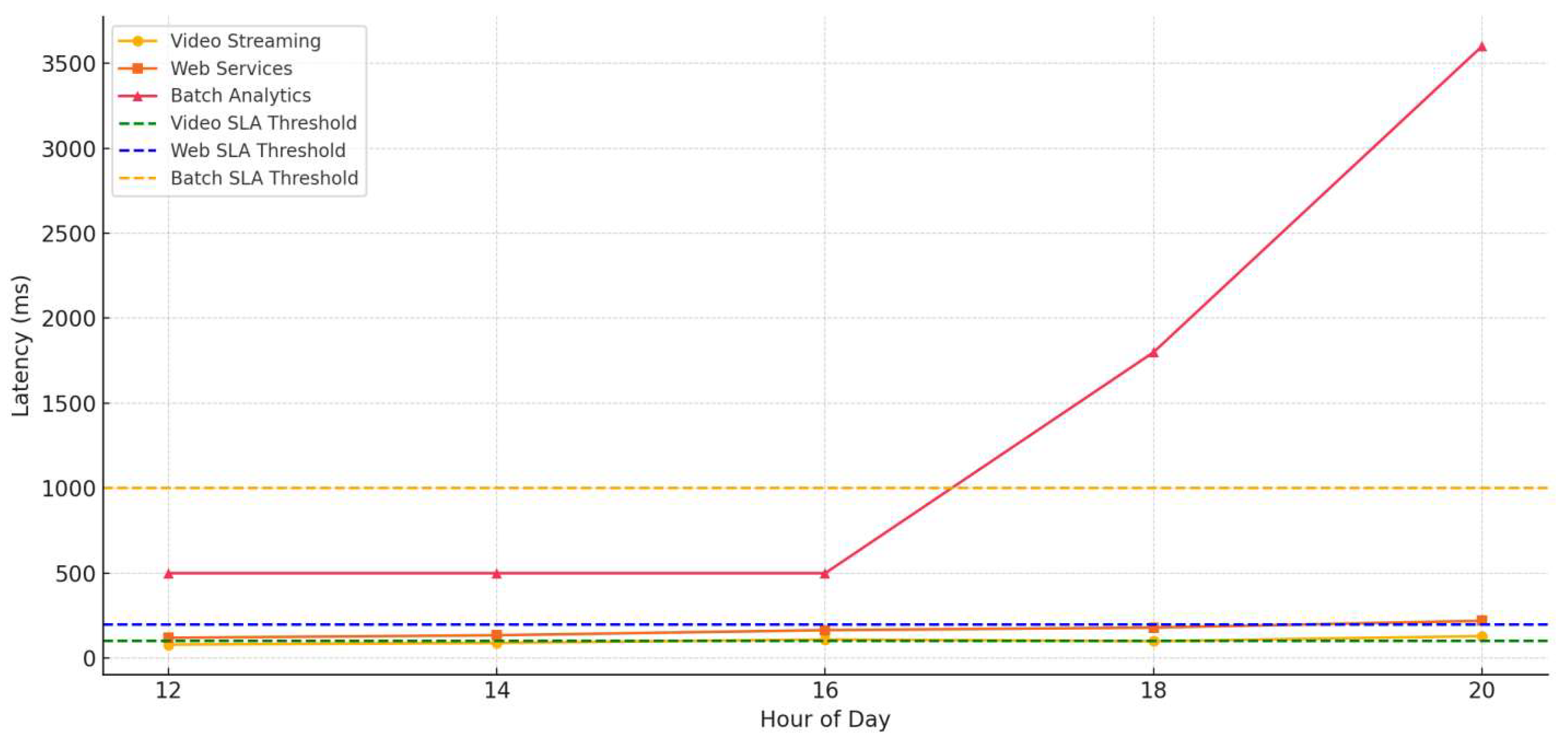

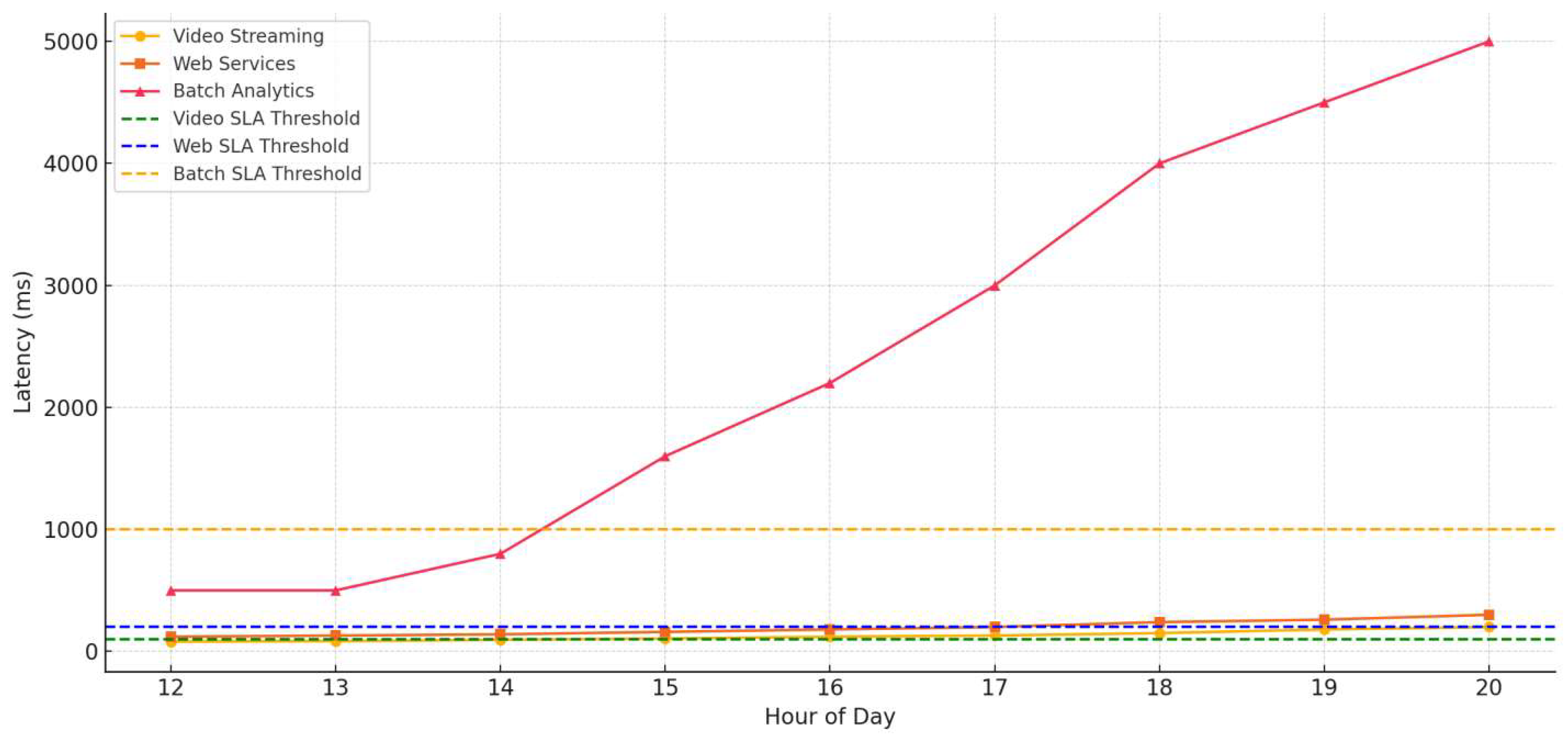

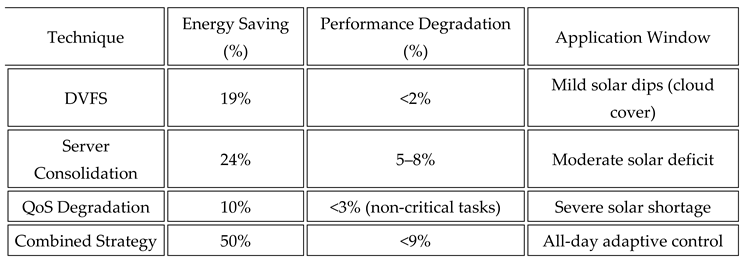

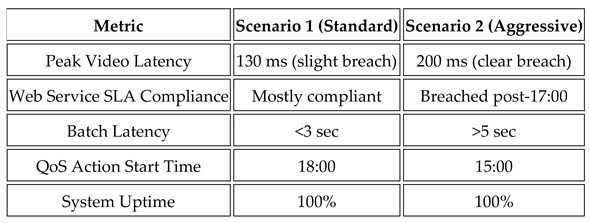

- DVFS yields an average of 19% power saving with less than 2% performance degradation.

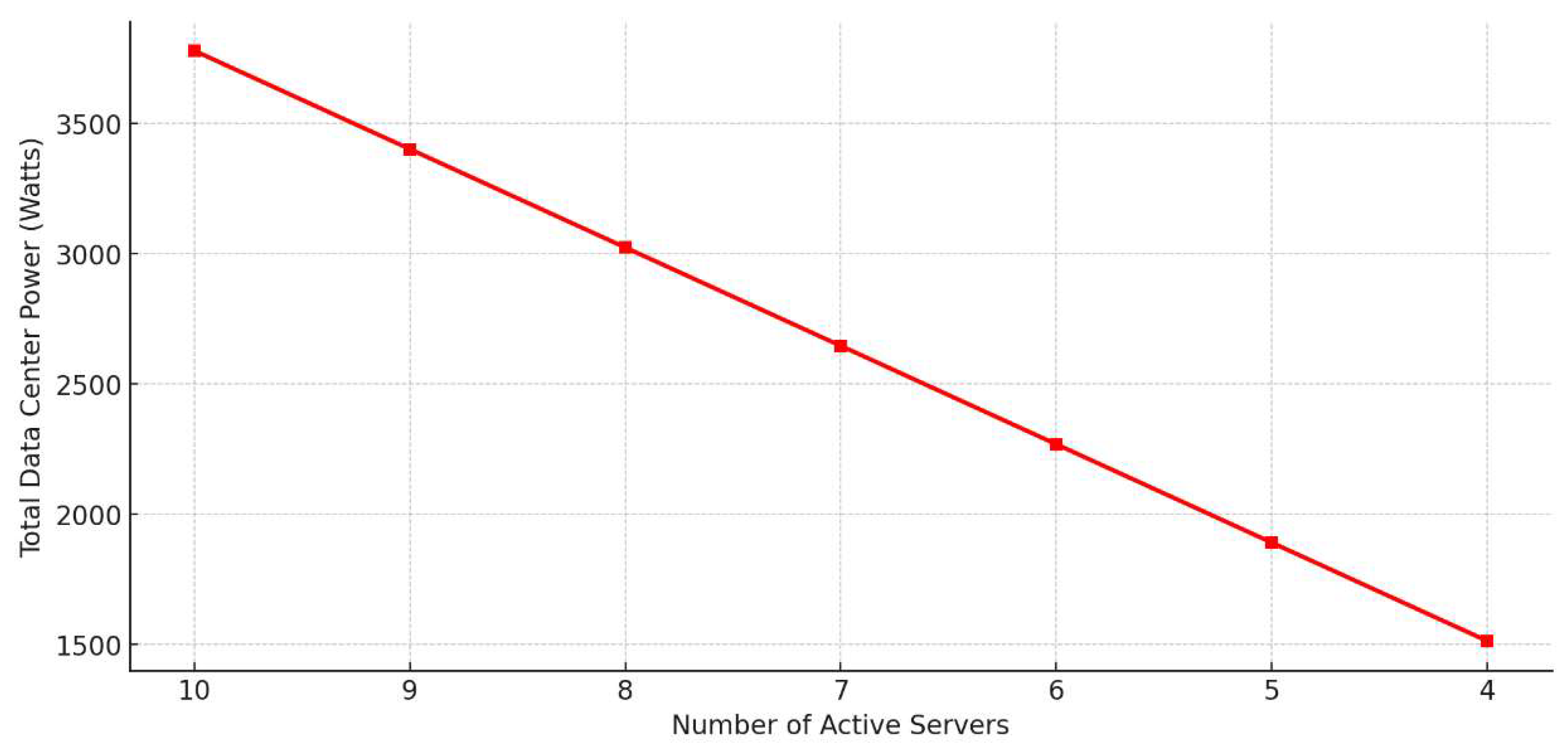

- Server Consolidation adds another 24% saving, albeit with 5–8% latency increase due to higher CPU utilization and workload migration.

- QoS Degradation, selectively applied to non-critical tasks, contributes an additional 10% energy reduction with minimal SLA violations.

- When applied together in a layered fashion, the combined strategy achieves up to 50% energy savings while maintaining performance loss below 9%.

- The green area represents the power saved by DVFS.

- The blue area quantifies additional savings due to server consolidation.

- The orange area illustrates the incremental gains from QoS degradation during critical power shortages.

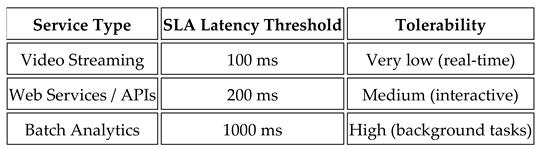

- Dynamic governance mechanisms must be aware of service criticality and prioritize essential functions accordingly.

- Deferred execution and graceful degradation are acceptable strategies for non-critical workloads during energy crises.

8. Future Enhancements: AI/ML and SDN Integration for Intelligent Power Optimization

8.1. Rationale for SDN Adoption:

- Global visibility: The SDN controller maintains a global view of server, application, and energy status.

- Fine-grained control: It can dynamically route, scale, or throttle data flows and workloads based on real-time constraints.

- Programmable power policies: Energy-related decisions (e.g., workload migration, path optimization) can be implemented as software policies, updated at runtime.

8.2. Role of AI/ML in Dynamic Power Governance:

- Solar irradiance trends and weather forecasts,

- CPU, memory, and network utilization per node,

- Energy consumption patterns,

- Application demand and SLA sensitivity.

- Predict short-term solar power availability (Psolar(t+Δt)P_{solar}(t+\Delta t)Psolar(t+Δt)),

- Forecast workload surges or underutilization,

- Recommend energy-saving actions (DVFS tuning, server shutdowns, traffic re-routing),

- Learn performance–power tradeoffs for different applications.

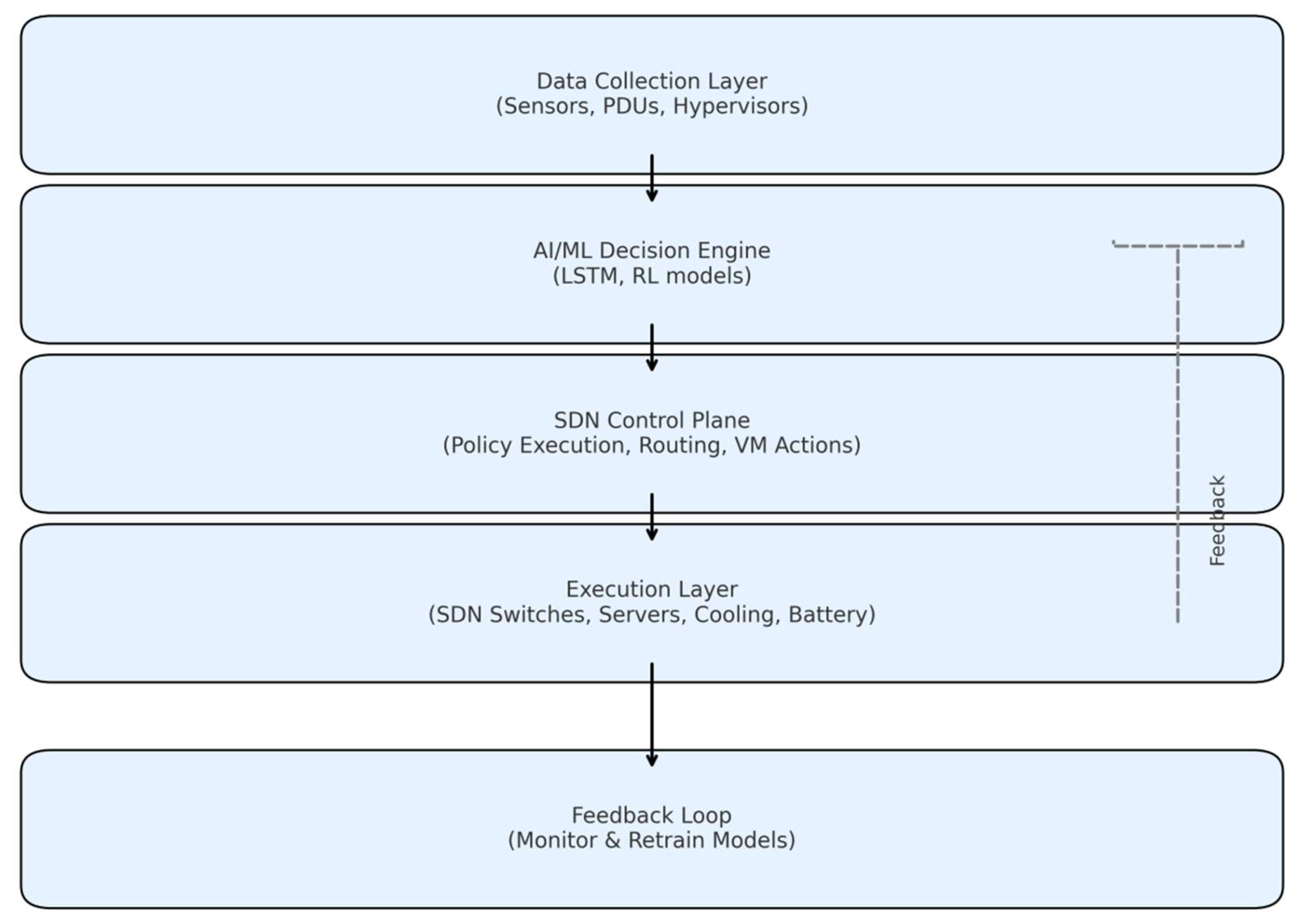

8.3. Conceptual Architecture:

- Data Collection Layer

- 2.

- AI/ML Decision Engine

- 3.

- SDN Control Plane

- 4.

- Execution Layer (Infrastructure)

- 5.

- Feedback Loop

8.4. Example Use Case: Predictive Server Consolidation

- Migrates VMs from 3 lightly loaded servers to others with spare capacity,

- Powers down the 3 idle servers,

- Reroutes network traffic through energy-efficient paths with fewer switches.

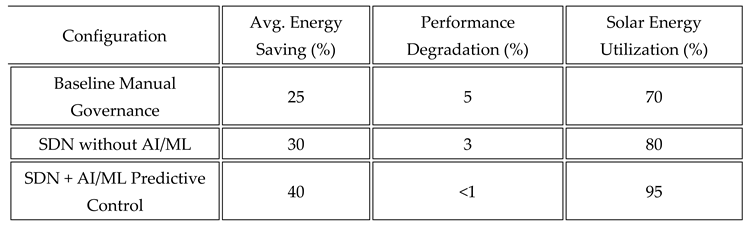

8.5. Estimated Benefits:

- Baseline (manual policy + basic DVFS),

- SDN-controlled data center without AI/ML,

- SDN + AI/ML with predictive power scheduling and workload management.

8.6. Implementation Challenges: Despite its benefits, this approach poses several challenges:

- Data Availability: High-quality training data for AI models may not always be available.

- Inference Latency: Real-time inference needs to be fast enough to support control loops.

- Interoperability: Requires integration across SDN controllers, hypervisors, energy APIs, and ML frameworks.

- Security & Trust: AI-driven control must be verifiable and resilient against false triggers or adversarial input.

9. Conclusions

References

- R. Ge, X. Feng, and K. Cameron, "PowerPack: Energy Profiling and Analysis of High-Performance Systems and Applications," IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems, vol. 21, no. 5, pp. 658–671, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Y. Nagasaka, K. Komoda, S. Yamada, M. Tanimoto, and H. Nakamura, "Statistical Power Modeling of GPU Kernels Using Performance Counters," in Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Low Power Electronics and Design (ISLPED), 2010.

- W. L. Bircher and L. K. John, "Complete System Power Estimation: A Trickle-Down Approach Based on Performance Events," in Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Performance Analysis of Systems and Software (ISPASS), 2007.

- A. Shah and K. Hinton, "Monitoring Data Center Energy Consumption and Emissions: Models and Tools," IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 1897–1910, 2016.

- Nvidia Corporation, "Tesla K20 GPU Accelerator Board Specification," 2012.

- IBM, "AMESTER: Automated Measurement of Systems for Temperature and Energy Reporting," Technical Report, 2011.

- Hewlett Packard, "HP Integrated Lights Out (iLO) User Guide," 2010.

- W. L. Bircher, M. Valluri, J. Law, and L. K. John, "Runtime Identification of Microprocessor Energy Saving Opportunities," in Proceedings of the International Symposium on Low Power Electronics and Design (ISLPED), 2005.

- R. Bertran, M. Gonzalez, X. Martorell, N. Navarro, and E. Ayguadé, "Decomposing Processor Power Consumption," in Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Performance Engineering (ICPE), 2010.

- C. Isci, A. Buyuktosunoglu, C. Cher, P. Bose, and M. Martonosi, "An Analysis of Efficient Multi-Core Global Power Management Policies: Maximizing Performance for a Given Power Budget," in Proceedings of the IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture (MICRO), 2006.

- W. Shiue and C. Chakrabarti, "Memory Exploration for Low Power, Embedded Systems," in Proceedings of the 36th Annual ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC), 1999.

- G. Contreras and M. Martonosi, "Power Prediction for Intel XScale Processors Using Performance Monitoring Unit Events," in Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Low Power Electronics and Design (ISLPED), 2005.

- Y. Chen, A. Sivasubramaniam, and M. Kandemir, "Profiling Power Behavior of Data Memory Subsystems for Stream Computing," in Proceedings of the IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture (MICRO), 2002.

- R. Joseph and M. Martonosi, "Run-Time Power Estimation in High-Performance Microprocessors," in Proceedings of the IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Low Power Electronics and Design (ISLPED), 2001.

- T. Li and L. K. John, "Run-Time Modeling and Estimation of Operating System Power Consumption," in Proceedings of the ACM SIGMETRICS International Conference on Measurement and Modeling of Computer Systems, 2003.

- P. Jarus, T. Włostowski, and A. Mielewczyk, "Efficient Run-Time Energy Estimation in HPC Systems," in Proceedings of the IEEE International Green and Sustainable Computing Conference (IGSC), 2013.

- J. Moreno and J. Xu, "Neural Network-Based Energy Efficiency Optimization for Virtualized Data Centers," in Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Cloud Computing Technology and Science (CloudCom), 2011.

- A. Lewis, S. Ardestani, and J. Renau, "Chaotic System Behavior and Power Modeling," in Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on High-Performance Computer Architecture (HPCA), 2012.

- R. Basmadjian and H. de Meer, "Evaluating and Modeling Power Consumption of Multi-Core Processors," in Proceedings of the IEEE Green Computing Conference (IGCC), 2012.

- J. McCullough, Y. Agarwal, J. Chandrashekar, S. Kuppuswamy, A. C. Snoeren, and R. Gupta, "Evaluating the Effectiveness of Model-Based Power Characterization," in Proceedings of the USENIX Annual Technical Conference (ATC), 2011.

- Al-Dulaimy, A., Itani, W., Zekri, A., & Zantout, R. (2016). Power management in virtualized data centers: State of the art. Journal of Cloud Computing, 5(6). [CrossRef]

- Ayanoglu, E. (2019). Energy Efficiency in Data Centers. IEEE Communications Society. https://www.comsoc.org/publications/tcn/2019-nov/energy-efficiency-data-centers.

- Gizli, V., & Gómez, J. M. (2018). A Framework for Optimizing Energy Efficiency in Data Centers. In From Science to Society (pp. 317–327). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Schlichting, A. (2016). Data Center Energy Efficiency Technologies and Methodologies. MITRE. https://www.mitre.org/news-insights/publication/data-center-energy-efficiency-technologies-and-methodologies.

- Federal Energy Management Program. (2019). Energy Efficiency in Data Centers. U.S. Department of Energy. https://www.energy.gov/femp/energy-efficiency-data-centers.

- Gozcu, O., Ozada, B., Carfi, M. U., & Erden, H. S. (2017). Worldwide energy analysis of major free cooling methods for data centers. In 2017 16th IEEE Intersociety Conference on Thermal and Thermomechanical Phenomena in Electronic Systems (ITherm) (pp. 968–976). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., et al. (2021). Usage impact on data center electricity needs: A system dynamic forecasting model. Applied Energy, 285, 116421. [CrossRef]

- MITRE Corporation. (2016). Data Center Energy Efficiency Technologies and Methodologies. https://www.mitre.org/news-insights/publication/data-center-energy-efficiency-technologies-and-methodologies.

- ABB. (2022). Data center energy efficiency and management. Data Center Dynamics. https://www.datacenterdynamics.com/en/whitepapers/data-center-energy-efficiency-and-management/.

- Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. (2024). 2024 United States Data Center Energy Usage Report. https://www.sfgate.com/tech/article/berkeley-report-data-centers-energy-19994091.php.

- U.S. Department of Energy. (2019). Energy Efficiency in Data Centers. https://www.energy.gov/femp/energy-efficiency-data-centers.

- Lei, L., et al. (2022). Prediction of Overall Energy Consumption of Data Centers in Different Locations. Sensors, 22(9), 3178. [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency. (2024). How AI Is Fueling a Boom in Data Centers and Energy Demand. Time. https://time.com/6987773/ai-data-centers-energy-usage-climate-change/.

- DeepSeek. (2025). AI is 'an energy hog,' but DeepSeek could change that. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/climate-change/603622/deepseek-ai-environment-energy-climate.

- International Monetary Fund. (2025). AI economic gains likely to outweigh emissions cost. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/climate-energy/ai-economic-gains-likely-outweigh-emissions-cost-says-imf-2025-04-22/.

- Business Insider. (2025). Climate tech startups are banking on an energy-guzzling sector: data centers. https://www.businessinsider.com/climate-tech-startups-data-center-boom-ai-funding-2025-4.

- Federal Energy Management Program. (2019). Center of Expertise for Energy Efficiency in Data Centers. U.S. Department of Energy. https://www.energy.gov/femp/center-expertise-energy-efficiency-data-centers.

- Sandia National Laboratories. (2023). Holistic Data Center Design Integrates Energy- and Water-Efficiency, Flexibility, and Resilience. https://www.energy.gov/femp/articles/sandias-liquid-cooled-data-center-boosts-efficiency-and-resiliency.

- International Energy Agency. (2024). How AI Is Fueling a Boom in Data Centers and Energy Demand. Time. https://time.com/6987773/ai-data-centers-energy-usage-climate-change/.

- Ali, Q.I., Design & implementation of a mobile phone charging system based on solar energy harvesting, EPC-IQ01 2010 - 2010 1st International Conference on Energy, Power and Control, 2010, pp. 264–267, 5767324.

- Ali, Q. I. (2016). "Enhanced power management scheme for embedded road side units." IET Computers & Digital Techniques, 10(4), 174-185. [CrossRef]

- Ali, Q. I. (2012). "Design and implementation of an embedded intrusion detection system for wireless applications." IET Information Security, 6(3), 171-182. [CrossRef]

- Ali, Q. I. (2016). "Securing solar energy-harvesting road-side unit using an embedded cooperative-hybrid intrusion detection system." IET Information Security, 10(6), 386-402. [CrossRef]

- Q. I. Ali, "Performance evaluation of WLAN internet sharing using DCF & PCF modes," Int. Arab. J. e Technol., vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 38-45, 2009.

- Lazim Qaddoori, S., Ali, Q.I.: An embedded and intelligent anomaly power consumption detection system based on smart metering. IET Wirel. Sens. Syst. 13(2), 75–90.

- Merza, M.E., Hussein, S.H., Ali, Q.I., Identification scheme of false data injection attack based on deep learning algorithms for smart grids, Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, 2023, 30(1), pp. 219–228. [CrossRef]

- Alhabib M.H., Ali Q.I., Internet of Autonomous Vehicles Communication Infrastructure: A Short Review, n(2023), 24 (3). [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value |

| Total Server Load | 12 × 300 W = 3600 W |

| Cooling Load | 0.4 × 3600 W = 1440 W |

| Total Avg. Power | 5040 W = 5.04 kW |

| Daily Energy Need | 5.04 kW × 24 h = 121 kWh |

| System Efficiency | η = 0.80 |

| Solar Hours (Erbil) | 5.5 h/day |

| Required PV Size | 121 / (5.5 × 0.80) ≈ 27.5 kW |

| Battery Storage (1 day, DoD margin) | 121 × 1.25 = 151.25 kWh |

| Inverter Sizing (20% margin) | 1.2 × 5.04 kW = 6.05 kW |

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).