1. Introduction

High-precision target positioning is critical in disaster relief, hazard monitoring, unmanned driving, and precision mapping. Target position information is generally obtained by combining global navigation satellite systems, navigation stations, and other navigation systems using onboard navigation devices. However, some targets cannot be equipped with navigation devices or fail to acquire navigation information, requiring external measurement equipment for positioning. In this way, the means to locate targets include radio[

1,

2], radar[

3], LiDAR[

4,

5], and optical approaches[

6,

7,

8]. Among these, optical positioning is passive and determines target positions without actively emitting electromagnetic waves, offering strong concealment[

9]. Additionally, visible light has a short wavelength and enjoys high observation resolution, providing high-precision target positioning. Driven by these advantages, this study focuses on target positioning under optical observation.

Common approaches using optical positioning include ground-based observation [

10,

11] and satellite[

12,

13] observation. The latter offers advantages such as a wide field of view, minimal influence from Earth's curvature and terrain, and broad operational coverage, making it a primary measuring platform for target positioning through external observation. However, due to the high relative velocity between the satellite and the target, conventional optical satellites have long imaging intervals, making continuous observation of targets challenging[

14]. In contrast, video satellites, with their short imaging intervals and capability for constant tracking imaging, can effectively overcome the limitations of conventional optical satellites in target positioning[

15].

In general, the target positioning methods based on optics included kinematic estimation method, image-matching method, and method that rely entirely on angle measurement data. The kinematic estimation method typically utilizes filtering algorithms to estimate the target position by combining a target kinematic model with observational data [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Furtherly, artificial intelligence methods such as neural networks[

20] and adaptive algorithms[

21] can be integrated to solve the problem that the kinematic model is too complex. Image-matching methods generally employ convolutional neural networks and other optical image recognition techniques to match target images with geographic information systems for target positioning[

22]. However, in practical applications, the factors such as the distance between the target and the satellite, camera performance, and target characteristics make it difficult to establish an accurate kinematic model and make it unable to match image. In contrast, methods that rely entirely on angle measurement data have a wider applicability. The approach determines the target’s position using the angular relationship between the satellite and the target under optical observation, that is, employing line-of-sight (LOS) angle intersection to calculate the position[

10]. Since the method does not require target feature information or other prior data, it overcomes the challenges associated with the kinematic estimation method and image-matching method. Therefore, this study focuses on target positioning under continuous observation using a single video satellite, and the fundamental idea is, after continuous stare observation of the target using a video satellite, determining the target position by using multiple observations of LOS angles and satellite position data.

The practical factors such as satellite manufacturing, launch conditions, and the space environment introduce errors in the measured LOS angles, causing discrepancies between the observed and actual values and further reducing positioning accuracy. In the distributed optical observation positioning scenario considered in this study, the target observation equation is inherently nonlinear, methods such as the Gauss-Newton (GN) method, Levenberg-Marquardt (LM)[

23] method, and maximum likelihood estimation can be used to estimate the target position. These methods enjoy good positioning accuracy under the assumption that observational errors follow a normal distribution. But in more general cases, there is bias in the error between the satellite LOS angle observations and the true value, which results in a reduction in the positioning accuracy of the above methods and an inability to effectively locate the target. In engineering applications, in order to eliminate the influence of the fixed error part in the error, the calibration method is often used to calculate the error compensation. However, there are short term fixed errors such as thermal deformation in practice, and long calibration periods cannot effectively solve such problems, and even in some cases satellites may not have calibration conditions.

Typical parameter estimation methods under non-ideal noise conditions include information-assisted correction[

24], state separation estimation[

25], error distribution estimation and compensation[

26], and systematic error self-correction[

27,

28]. Among these methods, the information-assisted correction method requires certain auxiliary prior information, but the prior information cannot be obtained in some cases. The state separation estimation method involves mathematically transforming the model to separate fixed biases with the target position, which is challenging to apply in this positioning situation. Besides, the error distribution estimation and compensation method needs to compute different fixed errors and estimated quantities separately, leading to high computational complexity. the systematic error self-correction method originates from spacecraft autonomous navigation and relies solely on observational data with relatively low computational complexity. Based on the approach, this paper proposes an analytical-iterative combined target positioning method for systematic error self-correction in video satellite systems. Specifically, the state is augmented by introducing extended-dimensional unknown variables to treat the fixed biases in observation as unknown parameters, and a combined approach of initial analytical estimation and iterative accuracy refinement is adopted. Precisely, the projection transformation method provides an initial analytical solution of the extended-dimensional unknown parameters. Then, the unknown parameters are iteratively optimized further, ultimately achieving a high-precision estimation of the target position.

In this paper, the distribution of errors in observation of video satellite is analyzed, and a new high precision target location method considering mixed observation errors is proposed. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

(1) Considering the influence of fixed error on target positioning accuracy, a fixed error processing method based on system error self correction is proposed. The fixed errors have been considered as unknowns in this method. A projection transformation method is proposed to make the positioning equations linear after extended-dimension.

(2) Given that the projection transformation method can only provides low linearized solution accuracy and that iterative computation can be time-consuming when the initial value is poor, this paper recommends an analytical-iterative combined algorithm. This developed scheme uses the projection transformation method to achieve an initial solution, followed by iterative computation for further optimization.

The remainder of this paper is as follows.

Section 2 presents the target positioning model under the video satellite stare mode.

Section 3 analyzes the errors generated during the target positioning process and establishes an error model based on this analysis.

Section 4 introduces a representation method that treats fixed errors as unknown parameters, along with the linearization approach for this positioning model, and proposes an analytical-iterative combined target position estimation method.

Section 5 provides experimental simulations and analyzes the results of the proposed method. Finally,

Section 6 concludes this work.

Notation: In this paper, scalars, column vectors, and matrices are represented by italic letters, bold italic lowercase letters, and bold italic uppercase letters, respectively. The notation refers to the observed value of a, while is its estimated value. denotes the identity matrix, and represents a diagonal matrix with as its diagonal elements.

2. Target Positioning Model in Stare Mode

A video satellite can identify and determine a target through feature extraction and classification algorithms. Based on this identification, the satellite utilizes image information and control methods to achieve stare tracking via its attitude control system, adjusting the target to the desired position within the field of view (FoV)[

29,

30,

31,

32]. Target images are captured from different angles during tracking, enabling target position calculation. Thus, to minimize the impact of camera imaging distortion errors, the target is typically positioned at the center of the FoV, which ensuring that roll-direction errors do not compromise positioning accuracy.

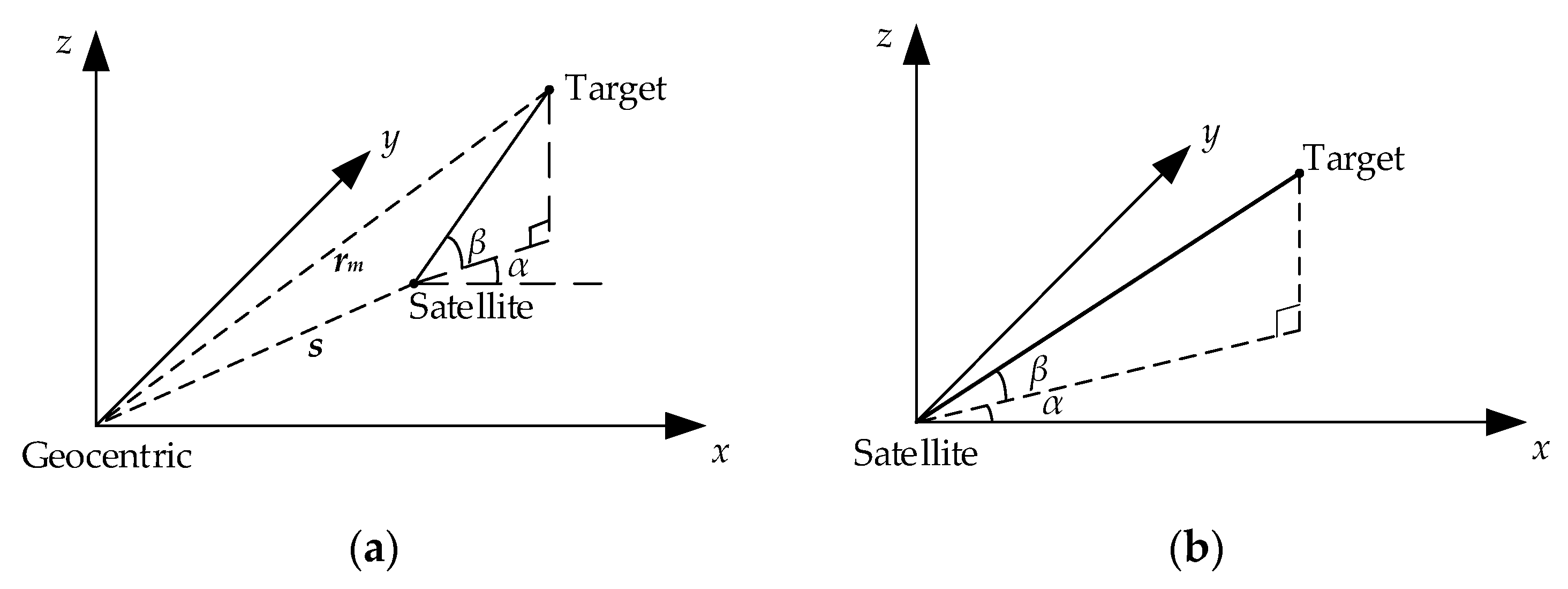

To better represent the position and the relationship of satellite and the target, this study adopts the Earth-centered, Earth-fixed (ECEF) coordinate system to facilitate calculations.

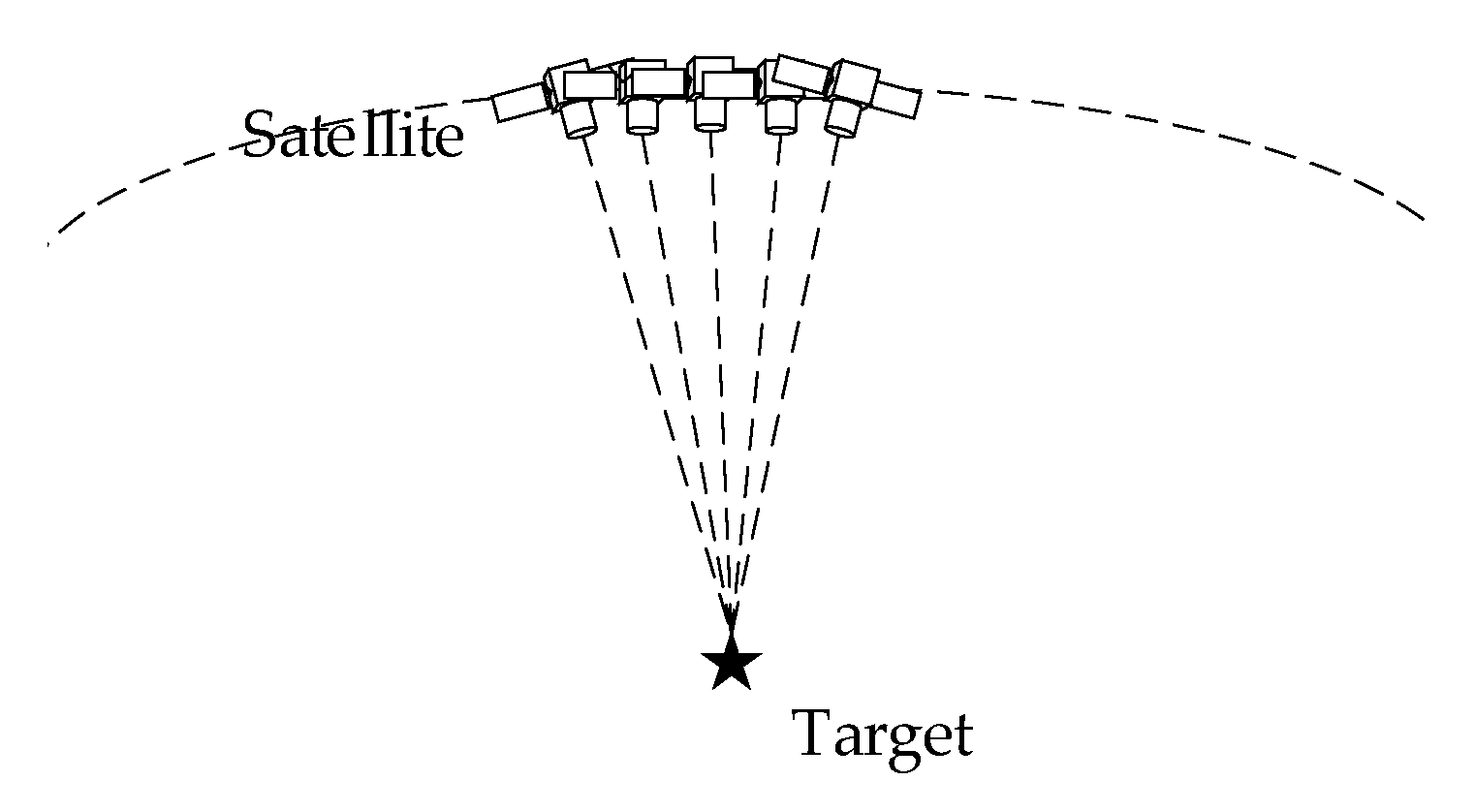

As illustrated in

Figure 1, at the

j-th observation (

j=1,2,…,

m; where

m is the total number of observations), the satellite's coordinates are given by

. The observed azimuth angle (Az) and elevation angle (El) of the target are denoted as

, where

is the Az and

is the El. Let the target position be estimated as

. The target observation is formulated as follows:

A single observation from one satellite (Eq. (1)) comprises two observation equations, while the target position contains three unknown variables. Therefore, at least two observations are required for an analytical solution, which is given by:

Eq. (2) is a nonlinear system of equations, which can be solved using the Newton iteration method in combination with the Aitken method[

33].

3. Error Analysis Affecting Positioning Accuracy

Various factors introduce errors in the observed LOS angles during satellite manufacturing, launch, and operation in the space environment, causing deviations from the true values. These errors ultimately degrade the accuracy of space target positioning. Therefore, analyzing the factors influencing satellite observation errors and establishing an observation model that accounts for them is mandatory, laying the foundation for high-precision positioning.

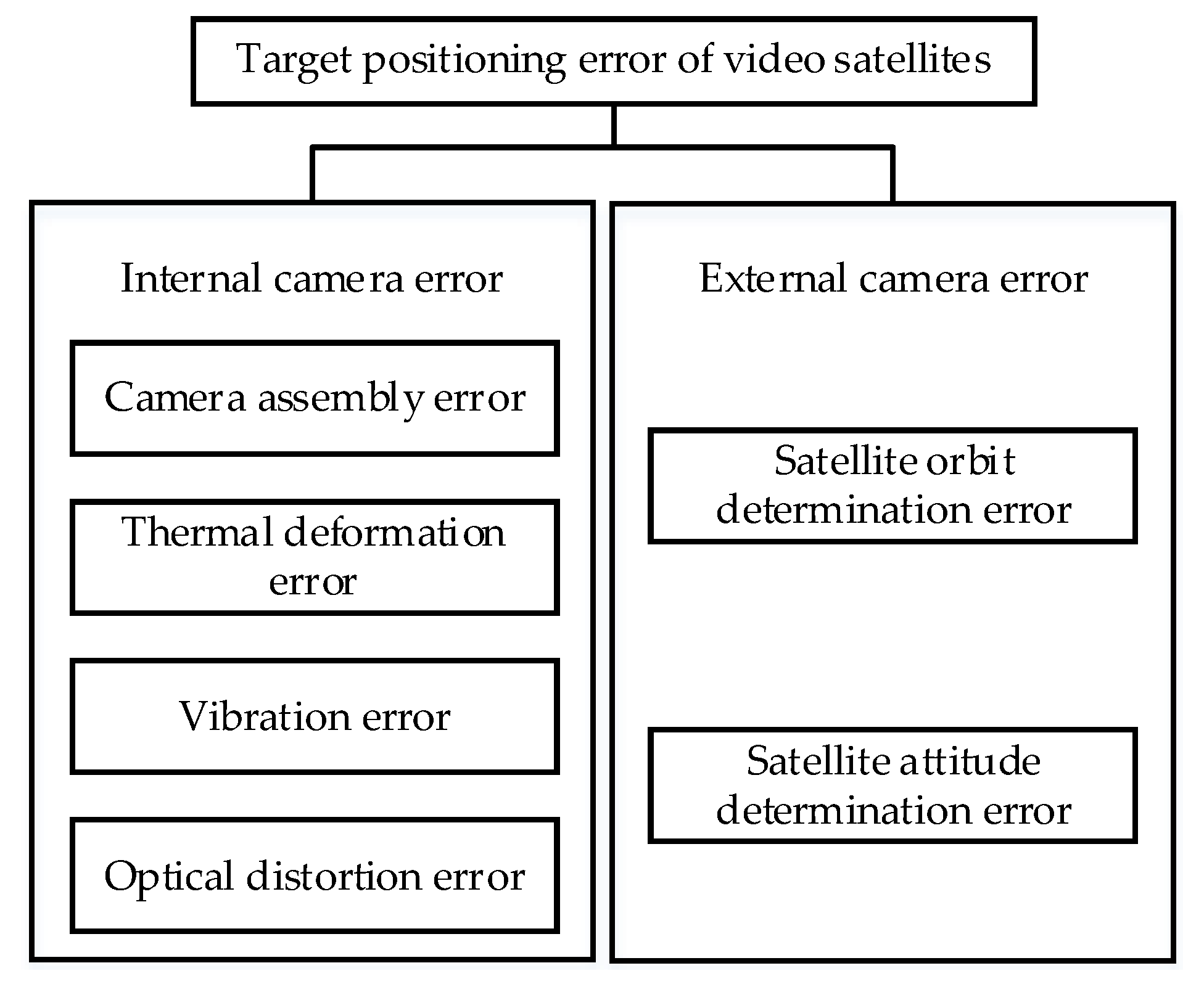

3.1. Sources of Errors

As illustrated in

Figure 2, the errors in optical remote sensing satellite target positioning can be categorized into internal and external camera errors[

34]. Internal camera errors include assembly, thermal deformation, vibration-induced, and optical distortion errors, while external errors include satellite orbit and satellite attitude determination errors.

3.1.1. Analysis of Internal Camera Errors

Camera assembly error arise from inaccuracies in the installation position of the camera during actual engineering applications[

35]. Such inaccuracies prevent the precise determination of the camera’s optical axis orientation after stare tracking control, leading to significant positioning errors. These errors mainly stem from satellite manufacturing and vibrations during launch, which misalign the camera's actual and theoretical coordinate systems.

Thermal deformation error results from the thermal expansion and contraction properties of materials. During satellite operation in orbit, variations in the satellite's relative position to the Earth and the Sun and changes in satellite attitude cause fluctuations in thermal conditions. The primary sources of satellite heating include solar radiation, Earth albedo, and Earth infrared radiation, with solar radiation contributing the most and exhibiting the most significant annual variation. The average annual solar radiation flux is approximately 1367 W/m

2, reaching a minimum of 1322 W/m

2 on the summer solstice and a maximum of 1414 W/m

2 on the winter solstice[

36]. The intensity of Earth's albedo radiation is correlated with solar radiation[

37]. Additionally, the effect of solar radiation on onboard materials is influenced by satellite attitude, solar El, and Earth shadowing, present both diurnal and annual periodic thermal deformations.

Vibration-induced error arises because components such as the camera mount and secondary mirror support structures are not perfectly rigid. When the satellite undergoes attitude maneuvers or is affected by the space environment, structural vibrations cause deviations in the camera’s optical axis from its intended state and introduce errors.

Optical distortion error originates from the nonlinear distortions introduced when the camera lens focuses light during imaging, resulting in image warping[

38]. Self-calibration data from ZY-3 satellite imagery indicate that CCD deformation errors exceed 0.5 pixels at the image edges. Although image correction techniques such as universal mathematical imaging models and image-space affine transformation methods can be used to rectify distortions in severe imaging errors, the effectiveness of these compensation techniques is limited[

39].

3.1.2. Analysis of External Camera Errors

Satellite orbit determination error arises while determining the satellite’s orbital position. Typically, when using the BeiDou Navigation Satellite System for positioning, the orbit determination accuracy is about 10 meters[

40]. When employing orbit extrapolation with periodic ground-based observations (once per orbit), errors can reach the hundred-meter level[

41]. Although ground-based tracking enables high-precision orbit determination, the limited observation arcs in practical applications lead to error divergence over time.

Satellite attitude determination error originates from inaccuracies in the satellite’s attitude determination process. For instance, when using star sensors for attitude determination, errors in the sensor’s optical system can introduce inaccuracies. Similarly, when using satellite navigation-based attitude determination, errors in positioning can propagate into attitude errors. In general, satellite attitude determination errors exceed 2.4 arcseconds[

42], while specialized platforms can achieve accuracy on 0.0001 degrees[

43].

3.2. Errors Model Establishment

Based on their distribution characteristics, errors can be categorized into systematic (fixed) and random. Fixed errors remain constant across multiple observations and are primarily caused by camera assembly error, optical distortion error, and thermal deformation error. Conversely, random errors vary randomly across observations and mainly result from satellite attitude determination error, orbit determination error, and vibration-induced error.

Considering the above analysis, under continuous observation by a single satellite, the relationship between the satellite’s observed LOS angles and their true values is expressed as:

where

represents the LOS angle measurement for the

j-th observation,

denotes the fixed angular error of the satellite, and

represents the random angular error for the

j-th observation. Let

denote the vector of all random observation errors. Under practical conditions, these errors can be assumed to follow a zero-mean normal distribution, with a covariance matrix denoted as

.

4. Target Positioning Under Non-Ideal Error Conditions

Due to observation errors, redundant observations are typically used to estimate the target position and improve positioning accuracy. Since the target positioning equation in stare mode is nonlinear, the equation for estimation is either linearized or solved iteratively using GN or LM methods. However, when non-ideal errors are present, directly applying these algorithms may fail to achieve accurate target positioning. Since fixed errors remain constant across the multiple observations, they can be considered as unknowns in the parameter estimation. The target position and fixed error are estimated simultaneously by the means of extended-dimension unknowns. In general, compared to linearized estimation methods, iterative estimation provides higher accuracy. Furthermore, when initial conditions are favorable, iterative positioning estimation reduces the number of iterations, thereby decreasing computational complexity and enhancing computational efficiency. Therefore, this study first linearizes the extended-dimension positioning model, and thus the analytical linear estimate of the target position is obtained as the favorable initial value. Subsequently, the LM iterative method refines the target position estimation to improve accuracy.

4.1. Extended-Dimension Unknowns Analytical Linear Estimation

The relationship between the angle observations and the target position to be estimated (Eq. (1)) contains unknown squared terms, square root terms, and inverse trigonometric functions, which make the parameter estimation highly nonlinear and complex to solve directly using linear estimation. In order to obtain the analytical initial value of the target position, a linearization representation of the positioning model is required. In order to facilitate the formula transformation, the formula linearization method and the corresponding estimate result are given firstly, then the formula linearization method for the extension dimension of the unknowns is presented.

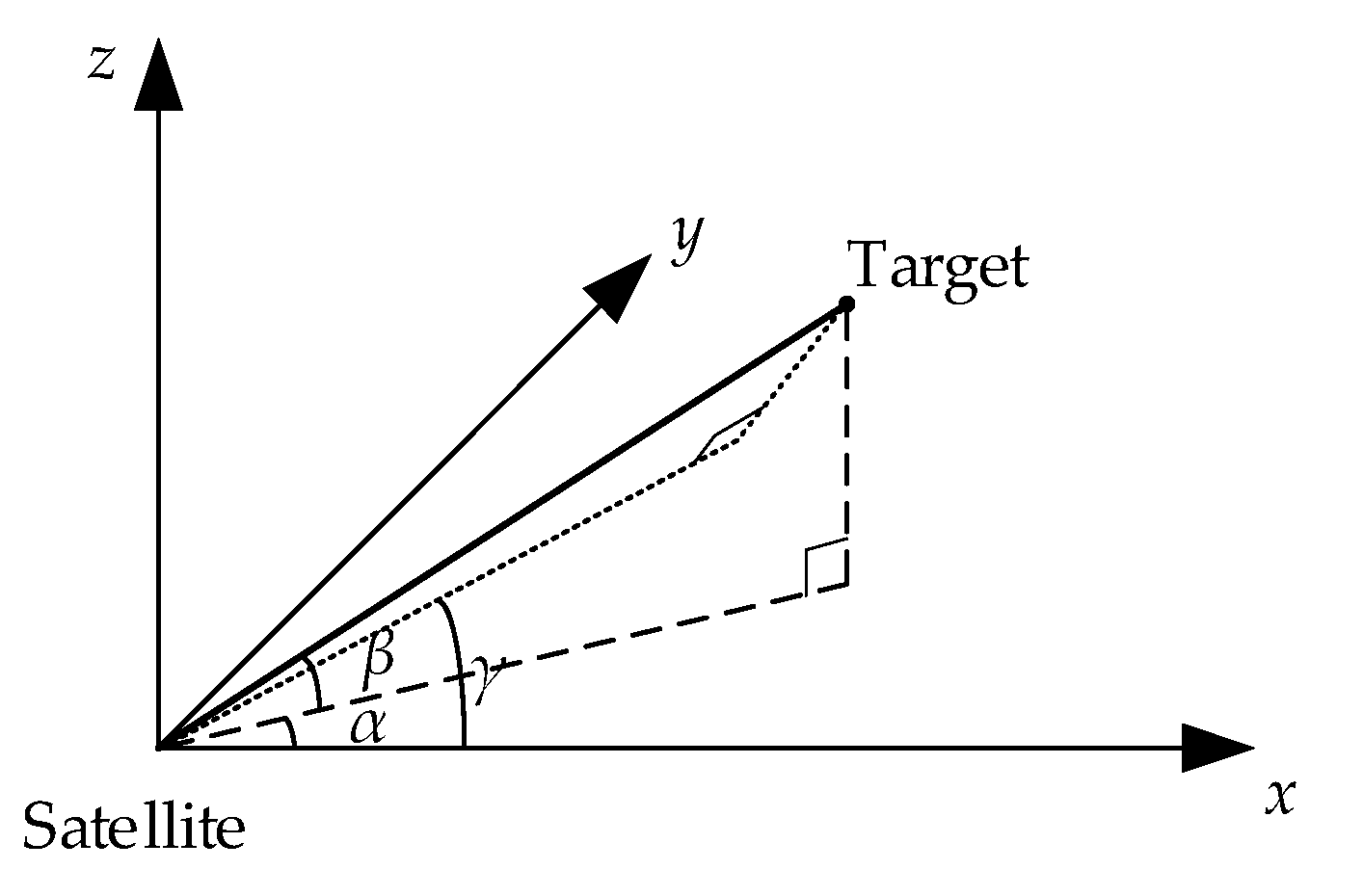

4.1.1. Projection Transformation for Target Position Equation

Consider the linearization of Eq. (1), the squared and square root terms of the unknowns mainly appear in the second term. To reduce the nonlinearity and preserve the completeness of the observation information, this study adopts the projection transformation method for the pitch angle in the second term of Eq. (1).

Figure 3 depicts the projection angle

in the

xOz plane. The relationship between the projection angle

, the Az

, and El

is given by:

By replacing

with

, we eliminate the square root and squared terms containing the unknowns in Eq. (1) while maintaining the completeness of the observation information. This strategy reduces the nonlinearity of the equation. Moreover, after substituting Eq. (4) into Eq. (1), we obtain:

This derivation transforms the equation containing the square root and square terms into a form that is more conducive to linearization and the derivation of a closed-form solution. Regarding the inverse trigonometric functions of the unknowns in Eq. (5), we expand them to obtain the linearized equation:

To facilitate further derivation, Eq. (6) is converted into a matrix form:

where

In order to improve target position accuracy, we explore the positioning problem under redundant observations, as presented in

Figure 4. Notably, the least squares method can solve the target position for multiple observations. Based on Eq. (7), the expression for the target position under multiple observations is given by:

where

In practice, the true values of the LOS angles cannot be obtained, so the observed LOS angles are used here. Thus,

where

and

represent the random and fixed errors in Eq. (9), respectively. Therefore, based on the least squares method, the estimated target position is given by:

4.1.2. Linear Transformation After Extended-Dimension

The estimation method presented in

Section 4.1.1 cannot effectively address the fixed errors in the target positioning model. Bringing the fixed errors in Eq. (3) into Eq. (5) as an unknown:

This leads to the following projection transformation:

where

Notably, completing the linearization as done in Eq. (6) is impossible, and thus, the fixed errors to be estimated are first extracted from the trigonometric calculations. Since fixed errors are relatively small, Eq. (14) can be approximated by linearizing

as follows:

Based on Eq. (15),

in Eq. (14) is determined by

and

, so it can be approximated linearly as:

where

is the Jacobian matrix of

with respect to the elements of

, and is expanded as:

where

The approximately linearized equation is then expanded as:

After extracting the fixed errors, Eq. (20) still contains a quadratic term involving the target position and fixed errors, which requires further linearization to derive the closed-form solution. Since the quadratic term in the target position to be estimated is the same across multiple observations, the multiple observation equations can be differentiated to eliminate the quadratic terms. It should be noted that the quadratic terms in Eq. (20) have different forms and quantities and, therefore, must be handled separately. First, a first-order differencing operation is performed for the first equation in Eq. (20), which contains a single quadratic term. By differencing the equations for two adjacent observations, we obtain:

By subtracting the term containing

, we can get:

where

Next, two differentiations are required for the second term in Eq. (20), which has two quadratic terms with different coefficients. By combining the adjacent two observation equations, we get:

Through subtraction, we eliminate the terms involving

:

where

After eliminating

, the same method can be used to eliminate the terms involving

, resulting in:

where

By combining Eqs. (22) and (27), we obtain the equations as:

where

where

ξ represents

x,

y,

z,

α,

β, 0.

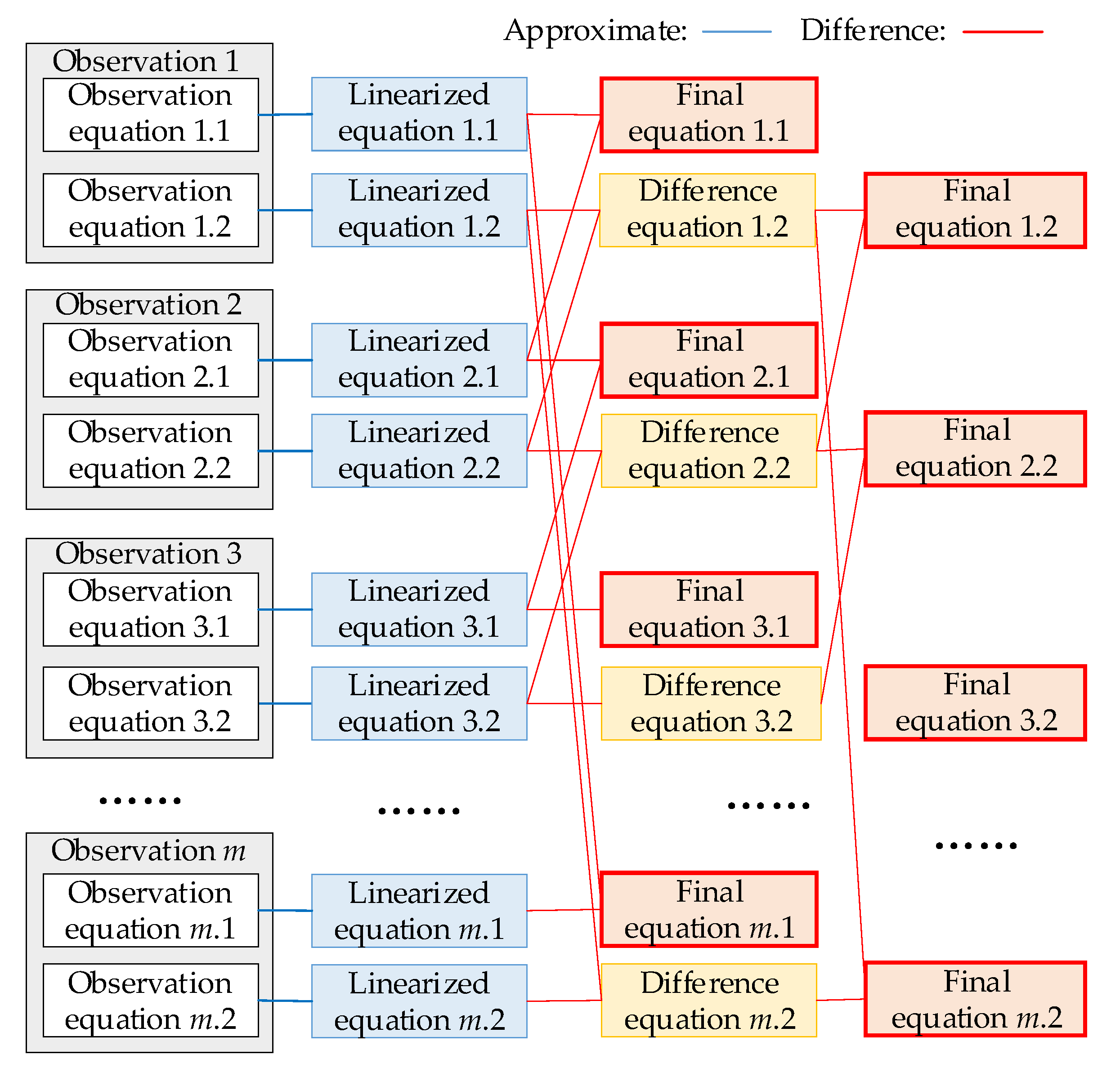

So far, the linear equation including the target position and the fixed error as the unknown is derived. A linearization flowchart is depicted in

Figure 5 to make the linearization process more straightforward. The process begins by extracting the fixed errors from the trigonometric calculations through approximation expansion, followed by differentiating between equations to eliminate higher-order terms, resulting in a linear system of equations.

Based on Eq. (29), substituting the observed LOS angles for the true values leads to:

where

is the random error. The dimension-extended linear method estimates of the target position and fixed errors can then be calculated as:

4.2. Iterative Solution of Extended-Dimension Unknowns

Estimating the target position using the dimension-extended linear method presented in

Section 4.1 amplifies the random errors on positioning accuracy, due to the differentiation operations and mathematical transformations used to eliminate the second-order terms. This imposes the dimension-extended linear method to underperform when random errors are significant. Hence, this study proposes a method that iterative optimization of the unknowns based on the dimension-extended linear estimation as the initial value to improve the parameter estimation accuracy.

Considering that the LM method converges fast and has a high estimation accuracy, it can improve the target positioning accuracy. Therefore, the LM is adopted as a method for further iterative optimization results. For ease of representation, the representation of Eq. (13) after the extended-dimension is simplified into:

which is then referred to as:

This process involves the following steps.

Step 1: Determine the initial iteration value, accuracy, and damping factor. The estimated result from Eq. (32) is used as the initial value , and the iteration accuracy σ and damping factor are set.

Step 2: Calculate the correction factor. A first-order Taylor expansion of

is performed at the

i-th iteration result

:

where

is the Jacobian matrix of

with respect to

θ, expanded as:

The expansion of Eq. (36) is provided in the Appendix. The correction factor and residual vector are defined as:

The residual vector is used to calculate the correction factor and assess the iteration stop condition, with the correction factor adjusting the previous iteration result. Substituting Eq. (37) into Eq. (35) and separating the random errors provides:

For faster convergence, a damping term

is added into Eq. (38), and the observed values are substituted for the true values to estimate the (

i+1)-th iteration correction factor:

Step 3: Compute the iteration result and residual vector. Use the correction factor from Step 2, adjust the (

i-1)-th iteration estimate, and calculate the

i-th iteration estimate as follows:

Next, calculate the residual vector at

as:

Step 4: End judgment and damping factor adjustment. When

, the iteration process terminates. When

, adjust the damping factor and continue the iteration. The damping factor affects the step size and direction of each iteration in the LM. The damping factor is updated in each iteration to ensure both estimation accuracy and convergence speed by comparing the change in the residual vector before and after iteration. If the residual does not decrease compared to the previous iteration, i.e.,

, explaining that the iteration step size is too large or the direction is incorrect, and resulting in an over-corrected estimation. In this case, the iteration step size must be reduced, and the recalculated estimation is:

where

is the negative feedback coefficient, ranging from (0, 1). At the same time, the iteration result is not updated, i.e.,

Then, the process returns to Eq. (39) for recalculation. If the residual decreases compared to the previous iteration, i.e.,

, explaining that the estimation is not over-corrected, and the iteration step size continues to increase:

where

is the positive feedback coefficient, ranging from (1, +∞). At the same time, the iteration result is updated:

Then, the process returns to Step 2 and continues iterating.

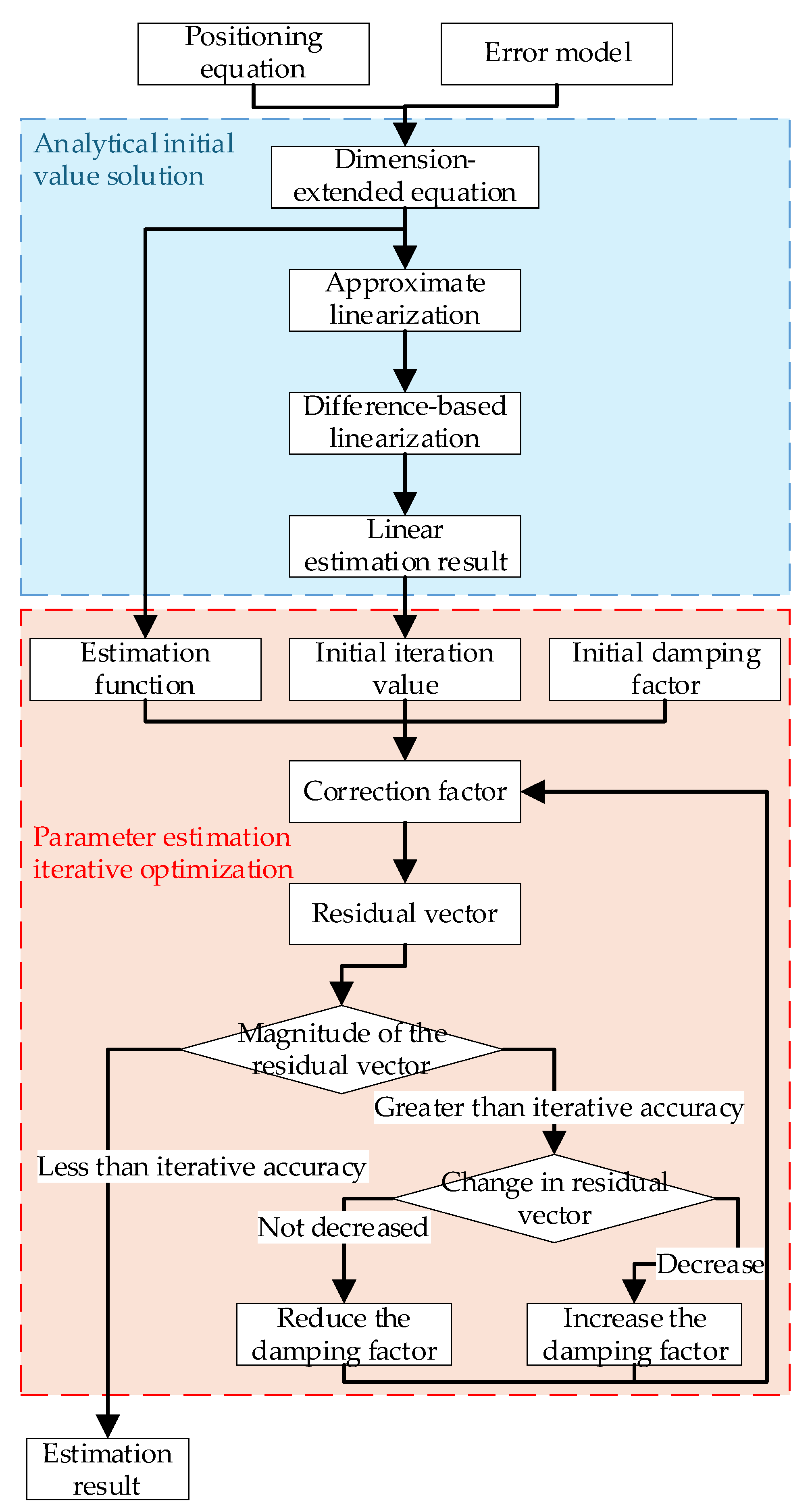

Figure 6 illustrates the flowchart of the proposed dimension-expanded combined method, which first derives the extended-dimension equations based on the positioning variance and error model. Then, the target position is estimated through the two analytical solving steps and the parameter estimation iteration optimization. The first step provides a good initial value for the latter optimization, which, in turn, the latter step yields a more accurate estimation result.

Figure 6.

Flowchart of the dimension-expanded combined method.

Figure 6.

Flowchart of the dimension-expanded combined method.

5. Simulation Experiment and Analysis

The simulated experiment involves continuous observation of the target from a single satellite with orbital elements, as reported in

Table 1, at the initial observation time. The observation interval is set to 1 second, and the observation value are affected by identical noise distribution. The target coordinates are [-2210.8,5012.5,3253.0] km. The experimental setup involves a 64-bit Windows 11 Home Edition, an AMD R7-7840HS CPU, and 16GB of RAM.

The positioning accuracy of the proposed method is evaluated under three different scenarios against the Aitken method[

33], projection transformation method (Eq. (12)), LM method[

23], combined method (Results calculated based on projection transformation method as initial values of LM algorithm without extended-dimension unknowns), dimension-extended linear method (Eq. (32)), dimension-expanded LM method (Results calculated based on the Aitken method as initial values of LM algorithm with extended-dimension unknowns), and dimension-expanded combined method (Results calculated based on dimension-extended linear method as initial values of LM algorithm with extended-dimension unknowns). The experimental scenarios are: (1) The satellite observation counts and random errors distribution remain unchanged while the effect of different fixed errors on positioning accuracy is analyzed. (2) The satellite observation counts and fixed errors magnitude remain unchanged while the effect of different random errors on positioning accuracy is analyzed. (3) The fixed errors and random errors magnitude distribution remain unchanged, while the effect of different satellite observation counts on positioning accuracy is analyzed.

Legend: Pink line for Aitken acceleration, blue line for the projection transformation method, cyan line for the LM method, black line for the combination method, red line for the dimension-extended linear method, yellow line for the dimension-extended LM method, and green line for the dimension-extended combination method.

These simulations aim to assess the performance of different methods in improving positioning accuracy across various scenarios. Additionally, since noise in a single trial is highly random, a Monte Carlo simulation with 10,000 iterations is performed to better illustrate the methods' effectiveness. It should be noted that the fixed error magnitude is denoted as dg and the random error magnitude as ds to describe the simulation results clearly.

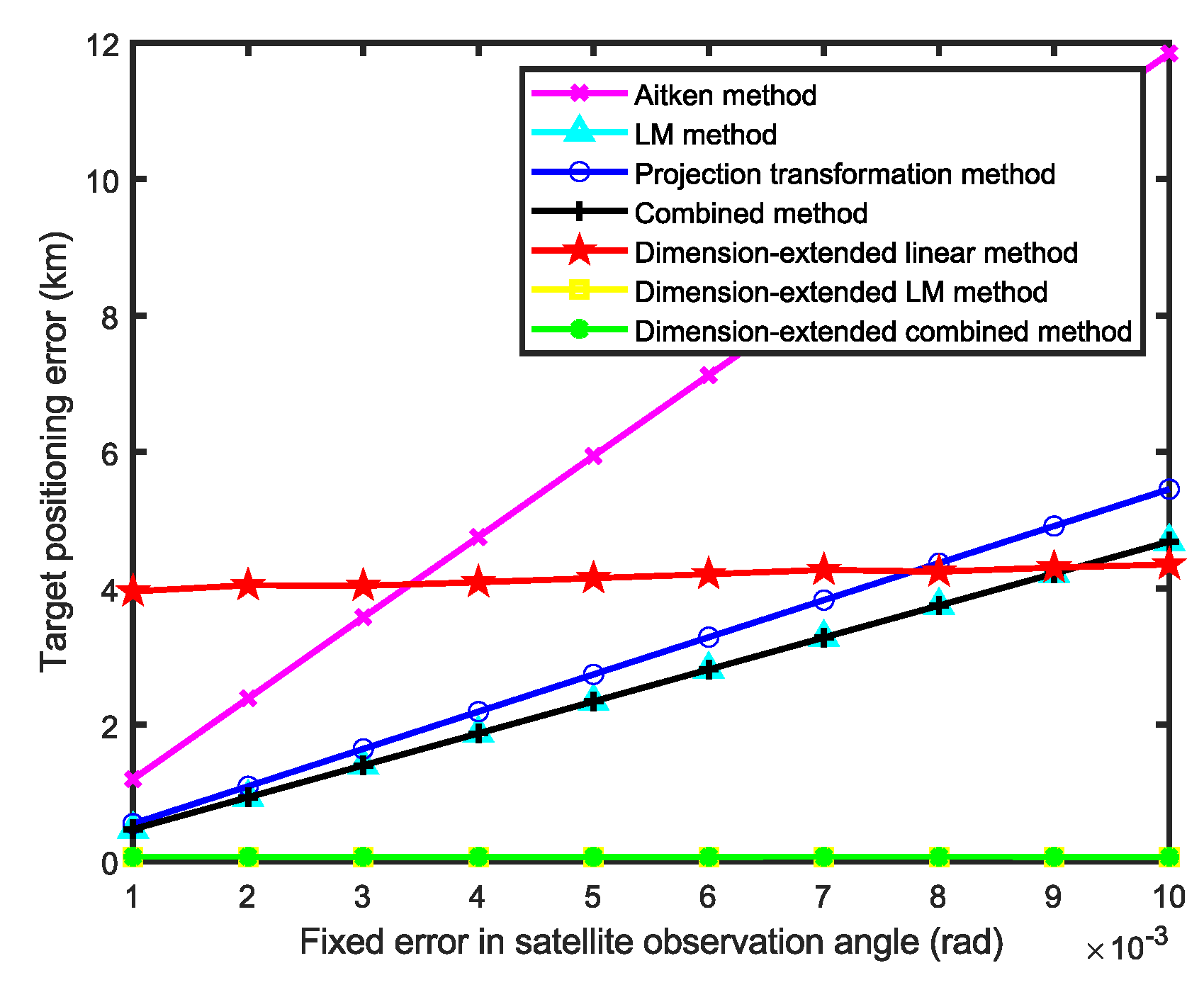

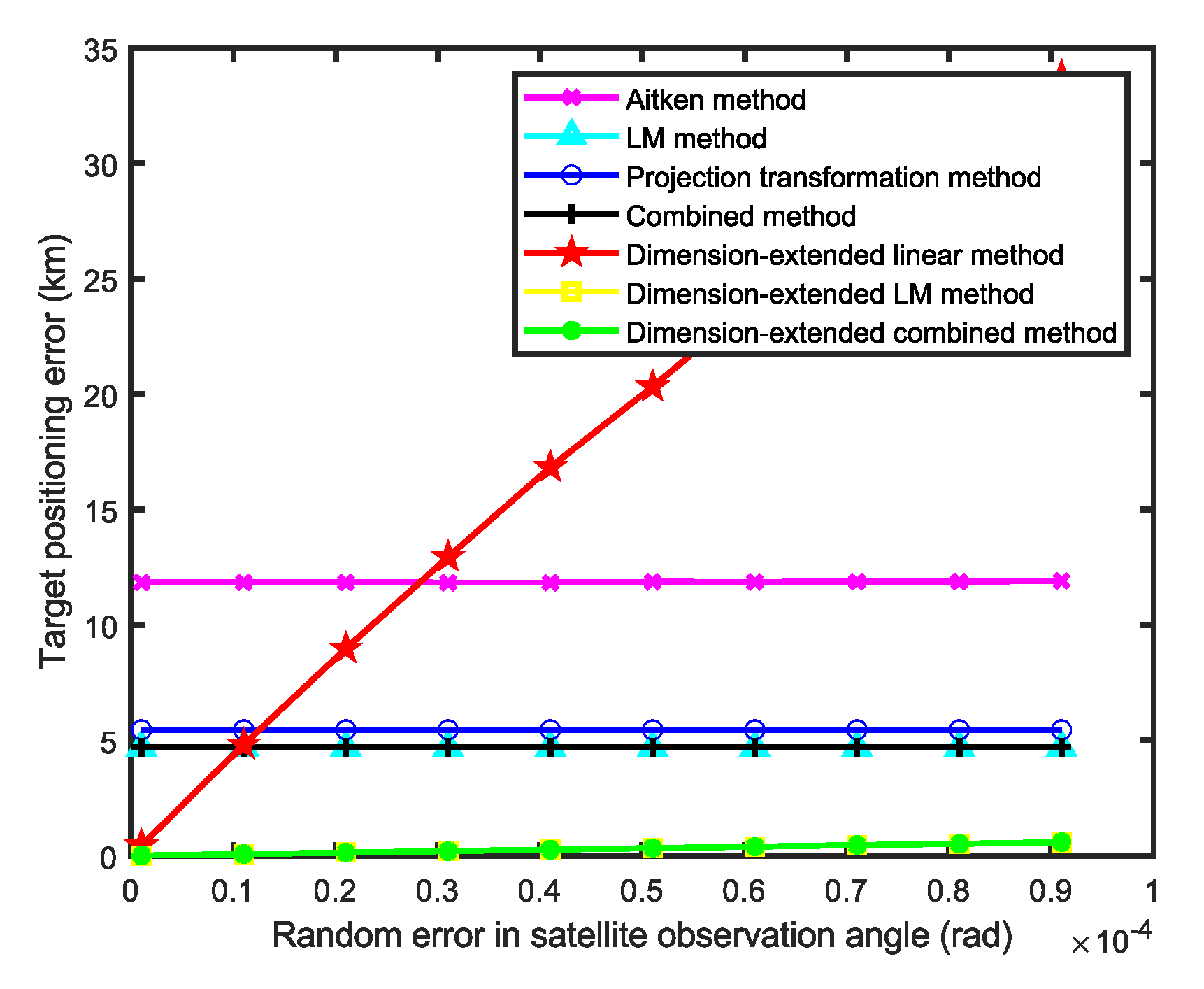

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 present the simulation results for 12 satellite observations, where

Figure 7 illustrating the variation of target positioning error with

dg when

ds=1×10

-5 rad and

Figure 8 depicting the variation of target positioning error with

ds when

dg=1×10

-2 rad. According to

Figure 7, as the fixed error increases, the positioning error of methods that do not consider fixed errors gradually increases. In contrast, the positioning error of the dimension-extended linear method increases slightly. The dimension-extended LM method and the dimension-extended combination method present a positioning error that is unchanged with the increasing of fixed errors. At this point it can be concluded that these two methods have identical positioning accuracy, unaffected by changes in the fixed error, and demonstrate superior performance compared to the other methods. And the positioning accuracy of the dimension-extended linear method is slightly affected by changes in the fixed error. According to

Figure 8, as the random error increases, the positioning error of all methods increases slightly, except for the dimension-extended linear method, where the positioning error increases significantly. The primary reason for this is that the differencing calculation in the linearization process of the dimension-extended linear method amplifies the impact of random errors. Meanwhile, the positioning accuracy of the dimension-extended LM method and the dimension-extended combination method remains identical and superior to other methods. Analyzing both figures reveals that the dimension-extended linear method effectively suppresses the influence of fixed errors on positioning accuracy but is sensitive to random errors. In contrast, the dimension-extended LM method and the dimension-extended combination method effectively suppress the influence of fixed errors on positioning accuracy without amplifying the impact of random errors.

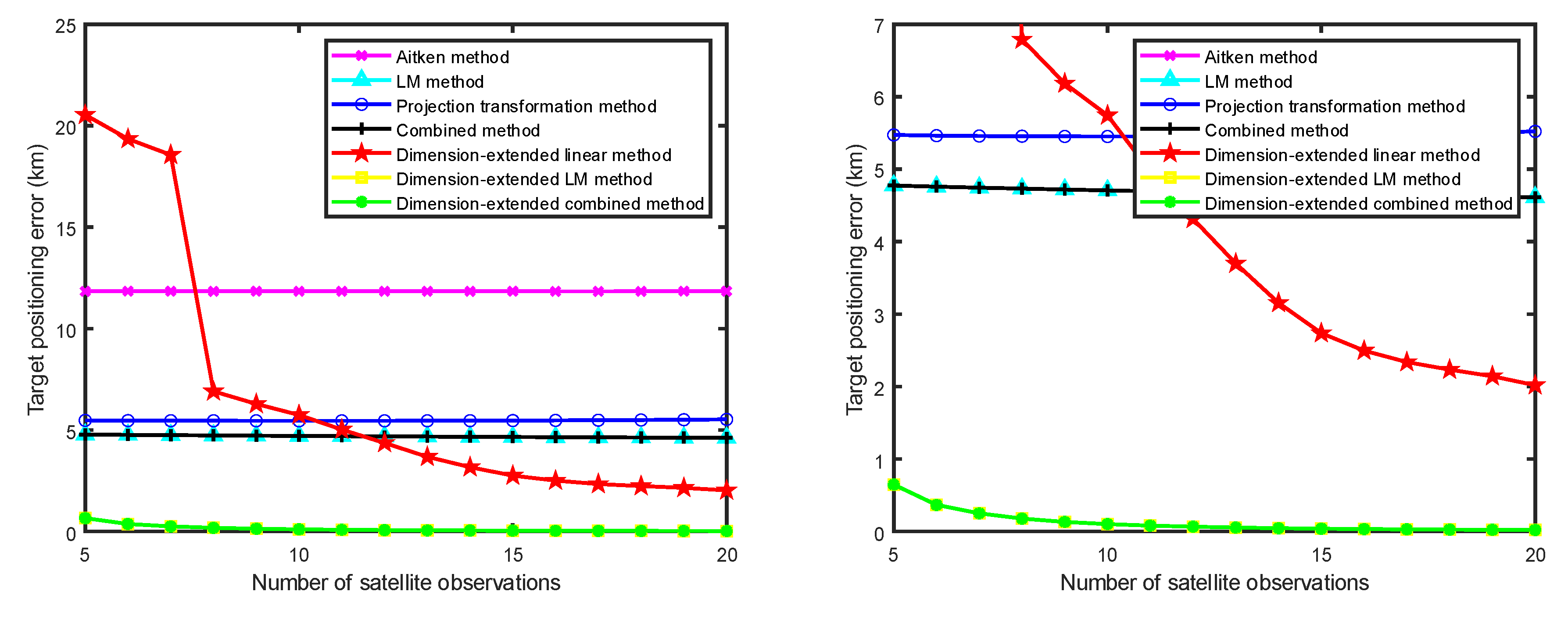

Figure 9 illustrates the variation in positioning accuracy of the aforementioned methods with respect to the number of observations. The simulation is conducted with

ds=1×10

-5 rad and

dg=1×10

-2 rad. According to

Figure 9, except for the Aitken acceleration method (which only utilizes the first two observations), the positioning accuracy of all methods improves as the number of satellite observations increases. When the number of satellites is small, the positioning accuracy of the dimension-extended linear method is relatively low. As the number of satellites increases, the accuracy of the extended-dimension linear method improves significantly, eventually surpassing the accuracy of algorithms that do not account for fixed errors. Notably, the dimension-extended LM method and the dimension-extended combination method consistently demonstrate high positioning accuracy.

Table 2 compares the processing speed of the methods evaluated here, indicating that linear estimation methods (including the projection transformation method and the dimension-extended linear method) are the fastest, approximately an order of magnitude faster than iterative methods. Combination algorithms (including the combination method and the dimension-extended combination method) are approximately twice as fast as purely iterative methods (including the LM and dimension-extended LM methods). Moreover, within combination algorithms, the impact of extended-dimension on computational speed is minimal.

6. Conclusions

This paper addresses the target positioning problem under non-ideal errors in camera LOS angles. A combined analytical-iterative target positioning method with systematic error self-correction is proposed, which formulates a dimension-extended equation by incorporating the target position and fixed errors as the parameters to be estimated. Furthermore, this method introduces a linear-iterative combined estimation strategy for high-precision and rapid target positioning. Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed dimension-extended combined algorithm effectively improves positioning accuracy under non-ideal errors compared to state-of-the-art algorithms while ensuring that the positioning accuracy remains unaffected by variations in fixed errors. Notably, the combined algorithm achieves approximately twice the processing speed of an iterative algorithm. This method can be further applied to high-precision, time-sensitive tasks such as emergency response and precision mapping, enabling video satellites to play a more effective role in relevant applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.B. and H.S.; methodology, X.B.; software, X.B. and H.S.; validation, X.B. and L.H.; formal analysis, X.B. and L.H.; investigation, X.B. and C.F.; resources, C.F. and Y.Y.; data curation, H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, X.B.; writing—review and editing, H.S. and C.F.; visualization, X.B. and Y.Y.; supervision, H.S.; project administration, C.F.; funding acquisition, C.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the China Pre - research projects for civil aerospace technology under the Grant D030201.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LOS |

Line-of-sight |

| GN |

Gauss-Newton algorithm |

| LM |

Levenberg-Marquarat algorithm |

| FoV |

Field of view |

| Az |

Azimuth angle |

| El |

Elevation angle |

| RAAN |

Right ascension of ascending node |

Appendix

The specific expansion of Eq. (36) is listed here:

where

The partial derivatives further be expanded are:

References

- Li, Y.B. Foreign Aerospace Electronic Reconnaissance Equipment: Development and Enlightenment. Telecommunication Engineering 2023, 63, 598-604. [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Wu, Y. Modeling and simulations of ECCM of ocean surveillance satellite electronic intelligence. In Proceedings of the 2012 5th International Conference on BioMedical Engineering and Informatics, 2012; pp. 1476-1480.

- Chen, Y.Z. Primary analysis of location error sources synthetic aperture radar satellite. Aerospace Shanghai 1998, 16-20+34. [CrossRef]

- Qiao P.; Lv X.N.; Zhao J.S.; Xia Y.L.; Li, J.M.; Zhou Y. Space Target Tracking and positioning Algorithm Using Multi-satellites. Spacecraft Engineering 2021, 30, 9-15.

- Lerro, D.; Bar-Shalom, Y. Tracking with debiased consistent converted measurements versus EKF. IEEE transactions on aerospace and electronic systems 1993, 29, 1015-1022.

- Chen, C.P.; Li, H.; Wei, Y.; Xia, T.; Tang, Y.Y. A local contrast method for small infrared target detection. IEEE transactions on geoscience and remote sensing 2013, 52, 574-581.

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, G.; Ma, Y.; Kang, J.U.; Kwan, C. Small infrared target detection based on fast adaptive masking and scaling with iterative segmentation. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2021, 19, 1-5.

- Grumman, N. Hypersonic & Ballistic Tracking Space Sensor; 2022.

- Liu, J.. Research on Single-base Angle Measurement Passive positioning Technology. Master, 2020.

- Long, H.; Li Z.J. Study and Simulation Analysis of Geometry Localization Based on LOS Observation. Computer Simulation 2010, 27, 14-17.

- Qiu, P.; Zou S.M.; Zhang X.M.; Wang, J.F.; Lin Q.; Jiang, X.J. Study on performance testing techniques for astronomical optical cameras. Infrared and Laser Engineering 2023, 52, 197-209.

- Cao, H.; Gao, W.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Fan, B.; Li, S. Overview of ZY-3 satellite research and application. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 63rd IAC (International Astronautical Congress), Naples, Italy, 2012; pp. 1-5.

- Wang, Z.; Luo, J.-A.; Zhang, X.-P. A novel location-penalized maximum likelihood estimator for bearing-only target localization. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2012, 60, 6166-6181.

- Fan, L.J.; Wang, Y.; Yang W.T.; Yu, L.J.; Zhang, G.B. GFDM-1 Satellite System Design and Technical Characteristics. Spacecraft Engineering 2021, 30, 10-19.

- Zhang X.Y. Study on Moving Objects Intelligent Sensing and Tracking Control for Video Satellite. Doctor, 2017.

- Gong, B.C. Research on Angles-only Relative Orbit Determination Algorithms for Spacecraft Autonomous Rendezvous. Doctor, 2016.

- Wang, D.Y; Hou, B.W.; Wang, J.Q.; Ge, D.M.; Li, M.D.; Xu, C.; Zhou, H.Y.. State estimation method for spacecraft autonomous navigation: Review. Acta Aeronautica et Astronautica Sinica 2021, 42, 72-89.

- Garg, S.K. Initial relative-orbit determination using second-order dynamics and line-of-sight measurements. Auburn University, 2015.

- Gong, B.; Wang, S.; Li, S.; Li, X. Review of space relative navigation based on angles-only measurements. Astrodynamics 2023, 7, 131-152.

- Gong, B.; Liu, Y.; Ning, X.; Li, S.; Ren, M. RBFNN-based angles-only orbit determination method for non-cooperative space targets. Advances in Space Research 2024.

- Zhang, Z.; Shu, L.; Zhang, K.; Zhu, Z.; Zhou, M.; Wang, X.; Yin, W. Orbit Determination and Thrust Estimation for Noncooperative Target Using Angle-Only Measurement. Space: Science & Technology 2023, 3, 0073.

- Lei, T.; Guan, B.; Liang, M.; Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; Shang, Y.; Yu, Q. Motion measurements of explosive shock waves based on an event camera. Optics Express 2024, 32, 15390-15409.

- Liu, J.; Xia, Z.X.. Modeling and Identification of Dynamic Systems; 2007.

- Yang, J.; Wang, K.; Xiong, K. In-orbit error calibration of star sensor based on high resolution imaging payload. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE SENSORS, 2015; pp. 1-4.

- Kim, K.H.; Lee, J.G.; Park, C.G. Adaptive two-stage extended Kalman filter for a fault-tolerant INS-GPS loosely coupled system. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems 2009, 45, 125-137.

- Liu, H.-b.; Wang, J.-q.; Tan, J.-c.; Yang, J.-k.; Jia, H.; Li, X.-j. Autonomous on-orbit calibration of a star tracker camera. Optical Engineering 2011, 50, 023604-023604-023608.

- Wei, C.L.; Zhang B.; Zhang, C.Q.. An Attitude Maneuvering Aided Self-calibration Algorithm for Celestial Autonomous Navigation System. Journal of Astronautics 2010, 31, 93-97.

- Zhang, C.Q.; Liu, L.D.; Li, Y. Observability Analysis for Biased Satellites Autonomous Orbit Determinati on Systems. Chinese Space Science And Technology 2006, 1-7+13.

- Fan, X.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Y.P.; Hu, G.H.. Study on Algorithms of Target Recognition and Target Tracking Based on Video Sequence. Fire Control & Command Control 2014, 39, 116-119.

- Wang, H.R.; Liu, X. Study on recognition and tracking algorithm for air vehicle infrared image. Laser & Infrared 2021, 51, 1097-1103.

- Avidan, S. Ensemble tracking. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2007, 29, 261-271.

- Wu, D.; Song, H.; Fan, C. Object tracking in satellite videos based on improved kernel correlation filter assisted by road information. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 4215.

- Shi, J.L.; Liu, S.Z.; Chen G.Z. Computer Numerical Method; 2009; p. 282.

- Zang W.C. Research on Major Errors in Sight Determination of Medium and Low Orbit Optical Satellites. Master, 2018.

- Song, C.; Fan, C.; Song, H.; Wang, M. Spacecraft Staring Attitude Control for Ground Targets Using an Uncalibrated Camera. Aerospace 2022, 9, 283.

- Huang, H.L. On-orbit External Heat Flow Calculation and Internal Thermal Analysis of Satellites. Master, 2019.

- Li, Q.; Kong, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.C. Thermal design and validation of multispectral max width optical remote sensing satellite. Optics and Precision Engineering 2020, 28, 904-913.

- Li, H.H.; Cao, H.; Shi, J. High Precision positioning Technology and Practice for High Resolution Optical Satellite Images. Geo Space Information 2018, 16, 1-8+137.

- Li, L.; Xie, J.H.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.J.; Pen, L.Y. Study on Image Distortion Correction Method of CCD Large Field of View Lens in Down view System. Modern Information Technology 2021, 5, 168-170+173. [CrossRef]

- China Satellite Navigation Engineering Center; China Aerospace Standardization Institute. Performance Specification for Public Service of BeiDou Navigation Satellite System. 2020, GB/T 39473-2020, 16.

- Ji, W.; Bai, T.; Wu, G.Q.; Lin B.J. The accuracy and error analysis of satellite autonomous celestial navigation orbit determination. Electronic Design Engineering 2017, 25, 90-93+97. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Q.; Wang, S.Y.; Chen C. A High-Precision Relative Attitude Determination Method for Satellite. Aerospace Control and Application 2014, 40, 19-24.

- Liu S.; Zhang, W.; Liao, B.; Tang Z.X.; Zhu M.; Xie J.J.; Yao C.. A Sailboard Sunshade High Pointing Accuracy and Stability Satellite Platform System for Morning and Dusk Orbits. CN112977884B, 2023-06-27.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).