1. Introduction

Lignocellulosic fibers stand out as the most intensively researched biomass for alternative substance utilization. Agricultural waste, in particular, is a highly valuable lignocellulosic resource due to its abundant availability, high yield, and relatively low cost [

1]. Maize, as the world's second-largest agricultural crop, generates substantial straw waste, with China alone producing over 10 million tons annually [

2]. The conversion of maize stover into value-added products and the alleviation of environmental impacts from straw accumulation are urgent challenges that require innovative solutions. Microbial anaerobic fermentation offers a viable approach to transform agricultural waste into a variety of industrial products, including organic acids, biofuels, enzymes, and lipids [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Optimizing microbial fermentation technology for the utilization of maize stover is a strategic direction for creating a cleaner and more sustainable environment.

Anaerobic fermentation of straw is a four-stage process comprising hydrolysis, acidogenesis, acetogenesis, and methanogenesis [

7]. During the hydrolysis stage, complex macromolecules such as cellulose, starch, proteins, and lipids are broken down into simpler monomers-sugars, amino acids, and fatty acids. These monomers are then converted into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), ethanol, hydrogen (H2), and carbon dioxide (CO2) in the acidogenesis phase. Acetogenesis involves the conversion of SCFAs and ethanol into acetate, which is subsequently converted to methane (CH4) either directly or through the reduction of CO2. Methane production is an effective and sustainable method for processing large amounts of lignocellulosic waste to meet global energy demands. SCFAs are more valuable than biomethane as they can be further converted into high-value-added chemicals, such as bioplastics, and biofuels, including biodiesel [

8,

9,

10]. Additionally, SCFAs can be transformed into medium-chain fatty acids (MCFAs) through beta-oxidation, a process that is gaining attention for its potential to yield products of higher economic value [

11,

12].

Rumen microorganisms are well-known for their remarkable degradation abilities, especially in breaking down plant materials rich in fiber, such as maize straw. The rumen's lignocellulosic biomass decomposition efficiency is estimated to be threefold higher compared to traditional anaerobic digesters [

13]. The rumen microbiota converts biomass into SCFAs, supplying nutrients for ruminants [

14], and also produces gases like methane and carbon dioxide. The synthesis of SCFAs and gaseous byproducts is achieved through the synergistic interactions within diverse microbial communities [

15]. The formation of SCFAs requires the participation of electron donors (EDs) and electron acceptors (EAs), initiating from acetic acid and extending the carbon chain via reverse β-oxidation [

16]. Ethanol, a well-known ED in fermentation processes, is oxidized to generate acetyl-CoA, which can engage in reverse β-oxidation. Additionally, the acetyl-CoA produced can promote chain elongation from acetic acid to butyric acid and facilitate the hexanoic acid pathway from butyric acid [

17,

18,

19].

Our previous research has demonstrated that ethanol can enhance SCFA chain elongation in mixed cultures of

in vitro rumen-fermented switchgrass [

20]. Nevertheless, the exact effect of adding ethanol on the relatively larger biomass of corn straw remains unclear. Additionally, the

in vitro degradation of straw by domesticated rumen microbes is a significant hurdle in rumen microbial fermentation. This study aims to explore the effect of ethanol addition on pH and gas production in a continuously passaged culture system, using agricultural waste corn straw as a substrate for

in vitro rumen liquid fermentation. The main focus is on the changes in the composition and chain length of SCFAs and the bacterial and fungal communities of the final generation (eighth generation). The

in vitro domestication of rumen microorganisms provides valuable insights into the utilization of agricultural waste resources, and promoting SCFA chain elongation in fermentation systems by adding EDs has the potential to convert agricultural waste into a high-value resource.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Substrate and Rumen Fluid

The experimental procedures concerning animals were approved by the Animal Care Committee at Yangzhou University (Yangzhou, China). The maize straw was obtained from the Animal Nutrition and Feed Engineering Technology Research Center, Yangzhou University, Jiangsu Province, China. Maize straw was dried at 65°C for 48 h, then ground through a 0.50 mm sieve, and sealed in hermetic/ air-tight bags for later use. Ruminal fluid was obtained from two dry-lactation Holstein cows with permanent ruminal fistulas fed twice daily (8:00 and 16:00) with a 40:60 concentrate to roughage ratio diet, and free access to water at the experimental farm of Yangzhou University (Gaoyou, China). Ruminal contents were collected before morning feeding, filtered through 4 layers of sterile gauze, and brought back to the laboratory immediately in a 39 ℃ water bath [

21].

2.2. Sequential Batch Culture

The saliva buffer was prepared by referring to Menke: 1.10 mg L-1 CaCl2⋅2H2O, 0.83 mg L-1 MnCl2⋅4H2O, 0.08 mg L-1 CoCl2⋅6H2O, 0.67 mg L-1 FeCl3⋅6H2O, 5.83 mg L-1 NaHCO3, 0.95 mg L-1 Na2HPO4, 1.03 mg L-1 KH2PO4, 0.10 mg L-1 MgSO4⋅7H2O [

22]. Maize straw (0.80 g) as fermentation substrate was weighed into 128 mL volume glass anaerobic culture flask before inoculation. 15 mL buffer and 2 mL rumen fluid were mixed and O2 was removed by continuously flushing with CO2. 0.15 mL of 2.5% sodium sulfide solution (w/v) was added as reduced reagent. Ethanol (final concentration, 200 mM in the culture) was supplemented in the flask, sealed with a rubber stopper with an aluminum cap and incubated at 39 ℃ for 72 h. The control group (CON) consisted of flasks containing substrate without ethanol addition. The ethanol (ETH) and CON groups had 6 replicates. Gas volume at 0, 2, 4, 6, 12, 24, 48 and 72h was recorded to calculate gas production. pH value and VFA production of fermentation fluid were tested at 72 h.

All continuous subculture procedures were similar to batch culture. At the first 72 h (first generation), 2 mL of culture fluid was transferred into new 128 mLflasks containing fresh culture media and substrate. pH value and gas production were monitored during the culture period. After 8 generations, the samples were collected for analysis of pH, VFA and bacterial composition.

2.3. Sampling and Analysis

The pH value of the fermentation liquid was determined by pH meter (PHS-25 produced by Shanghai Electronic Instrument Co., LTD.). The pressure values in the flasks at each time point were determined using pressure gauge (barometer DPG1000B15PSG-5, CeComp Electronics Inc.) [

20,

23]. The calculation equation was applied:

where Vgas is the gas volume at 39 ℃, mL, Vj is the vial volume headspace of liquid, mL, Ppsi is the pressure of the vial, psi.

At each sampling time, the fermentation mixture was collected using a syringe, and the samples were pretreated for later determination. Briefly, fermentation liquid was centrifuged (12000 r/min, 20 min), and 1mL supernatant was mixed with 0.2 mL 20% metaphosphoric acid (containing 60mM crotonic acid), and kept overnight in a refrigerator at -20 ℃. After thawing, the acidified samples were centrifuged (12000 r/min, 10 min, 4 ℃) and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.22μm water phase filter membrane. The percentages of the individual VFA (Acetic, propionic, butyric, valeric and caporic acid) were measured by gas chromatography and column type, the same as the gas assay above. The temperature of the injector, column and detector was 200 ℃, 110 ℃, and 200 ℃. The carrier gas was nitrogen, with 50 mL min

-1 flow rate and 1 μL injection volume. In addition to quantifying g/L individual concentrations of individual and total SCFA, total alkyl concentrations(TAL) and average SCFA chain lengths (ACL) were calculated as previously described [

12,

20].

The amplification primers for 16S rDNA sequencing were 515F and 806R of the 16S V4 region (515F: 5'-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3') and (806R: 5'-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3'). The ITS amplicon sequencing primers are ITS5-1737F to ITS2-2043R (1737F: 5'-GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG-3', 2043R: 5'-GCTGCGTTCTTCAT CGATGC-3'). The PCR products were sent to Novogene Co., Ltd (Beijing, China) for high-throughput sequencing analysis. Microbial sequencing was analyzed as elaborated previously [

24].

2.4. Statistical analysis

The significance of differences was determined using independent samples T-tests and univariate general linear models in SPSS 26.0 software. The test results were expressed as "mean ± standard deviation", with p-Value less than 0.05 indicating significant differences. It should be noted that due to the insufficient readings of ITS, one sample had to be removed from the ETH group.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effects of Ethanol on Continuous Subcultured Culture of Maize Straw with Rumen Liquid

3.1.1. pH and Gas Production

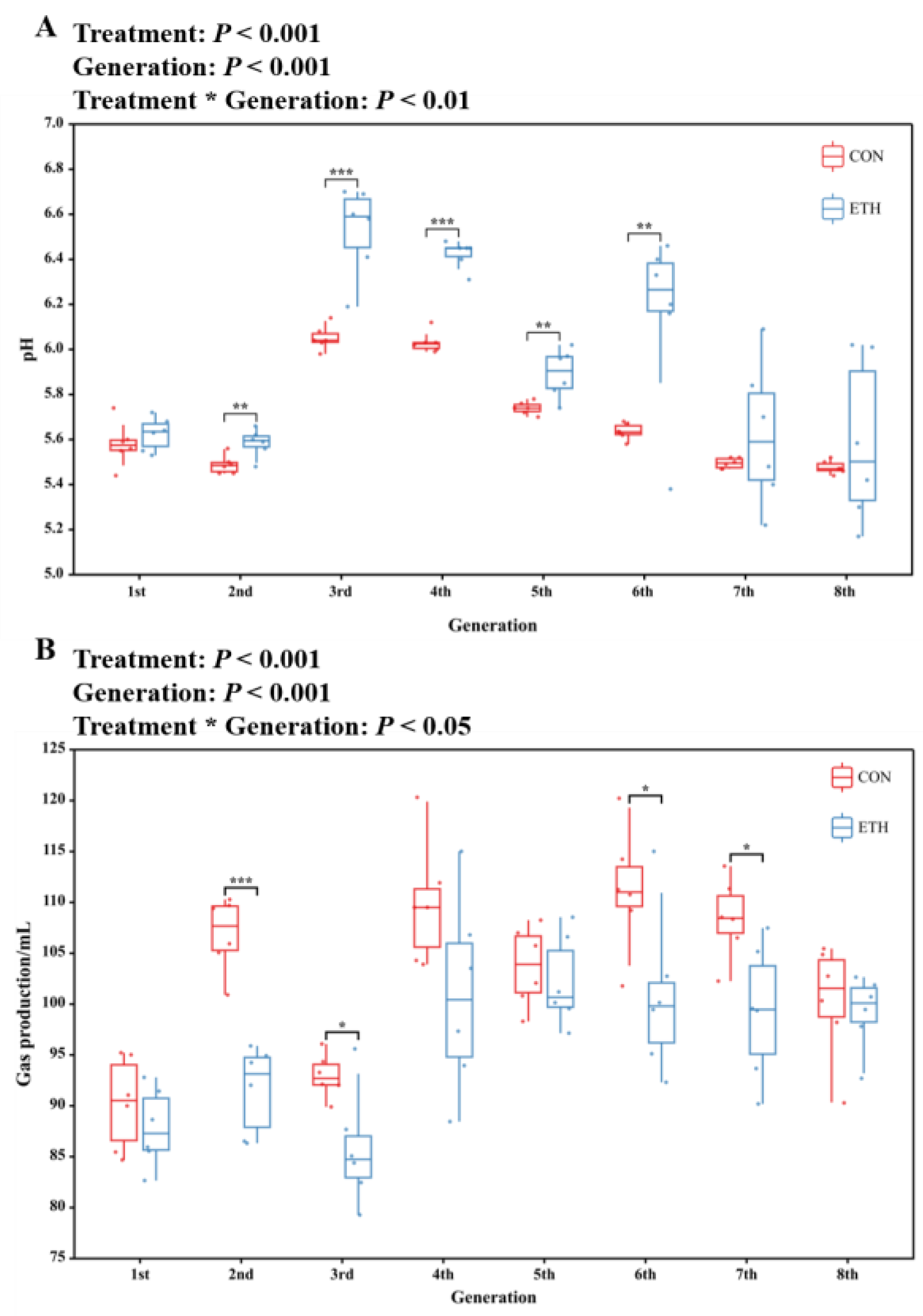

Using rumen fluid as the inoculum and 72-h fermentation fluid for continuous subculture, maize stover was fermented to produce acid. Ethanol was added as an electron donor (ED) to promote chain elongation via β-oxidation for caproic acid production. The variations in pH and gas production during anaerobic fermentation across different generations are shown in

Figure 1. The addition of ethanol and eight consecutive subculturing cycles of the enriched cultures in the same medium led to significant changes in the fermentation pH and total gas production. In the continuous subculturing processes, the pH values at the end of each cycle generally ranged from 5.2 ~ 6.7 (mean = 5.81), and each culture cycle produced 80 ~ 120 mL (mean = 99.5 mL) of gas. The significant increase in the pH of the fermentation broth with ethanol addition compared to the CON group might be due to the effective use of ED to promote organic acid chain elongation, thereby reducing the H+ ion concentration in the fermentation broth [

18,

25,

26]. Interestingly, the amount of gas produced by the ETH group was significantly reduced. Although the composition of the produced gas was not detected, this could indicate that fewer carbon - containing compounds were released into the gas phase.

Figure 1.

Effect of ethanol supplementation and continuous passages on (A) pH and (B) gas production of maize straw fermented with ruminal fluid in vitro (CON: Control; ETH: with 200 mM of ethanol).

Figure 1.

Effect of ethanol supplementation and continuous passages on (A) pH and (B) gas production of maize straw fermented with ruminal fluid in vitro (CON: Control; ETH: with 200 mM of ethanol).

3.1.2. Ethanol Promotes the Production of Caproic Acid and Chain Extension

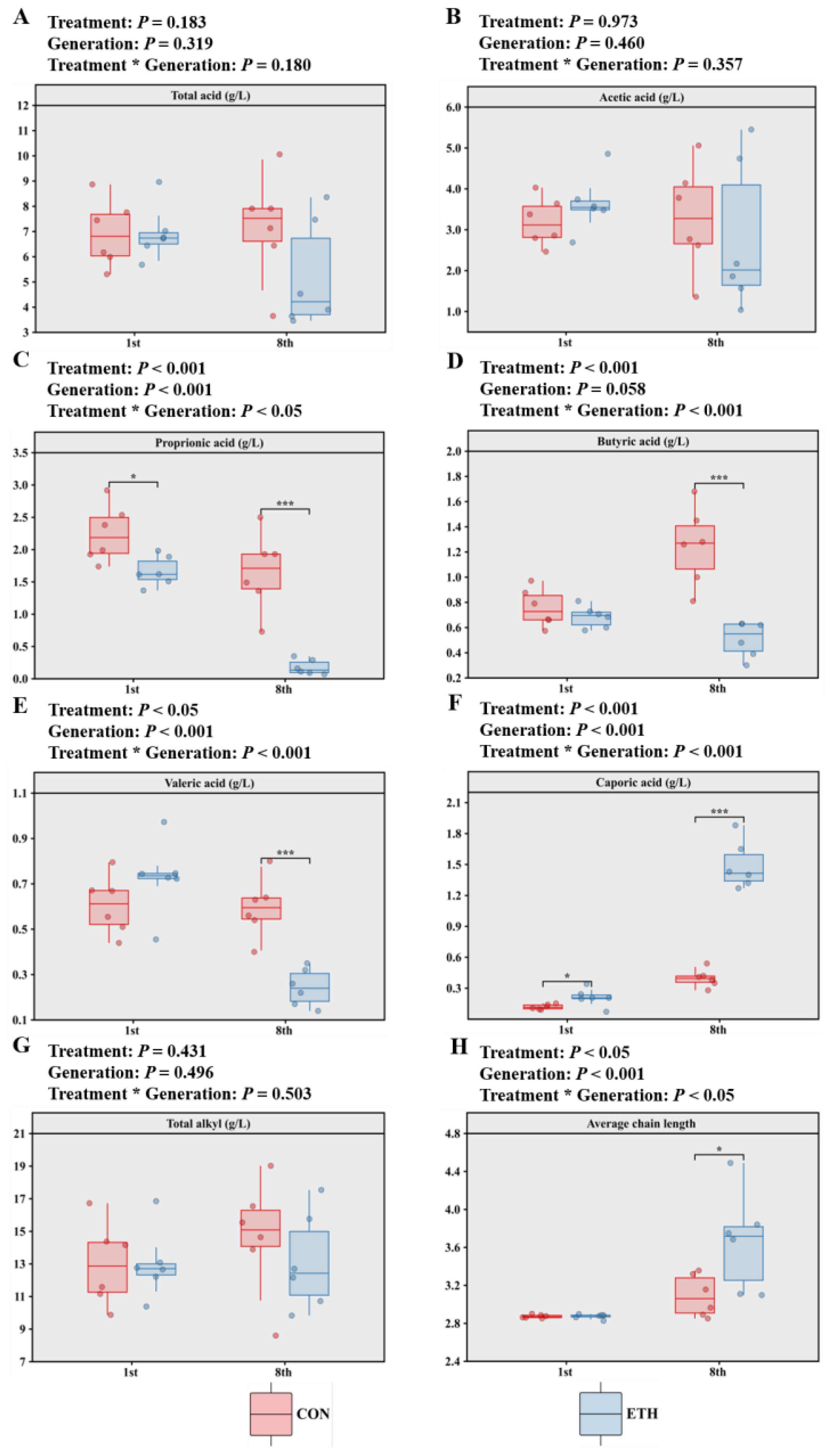

Adding ethanol to the fermentation of maize stover with rumen fluid led to acetate dominance, with propionate, butyrate, valerate, and caproate contents (in g/L) being successively lower (

Figure 2). Prior to subculturing, although ethanol addition to the fermentation could reduce propionate production and increase caproate production, it did not significantly increase the total VFA yield or the average chain length (ACL) (CON: 2.87 vs ETH: 2.87). However, after subculturing, consistent with expectations, the ETH group exhibited reduced production of propionate (CON: 1.66 g/L vs ETH: 0.18 g/L), butyrate (CON: 1.25 g/L vs ETH: 0.51 g/L), and valerate (CON: 0.58 g/L vs ETH: 0.24 g/L), along with enhanced caproate production (CON: 0.4 g/L vs ETH: 1.49 g/L) and an extended average VFA chain length (CON: 3.09 vs ETH: 3.66). Additionally, valerate production and ACL extension were influenced by the interaction between ethanol addition and subculturing.

Figure 2.

Effect of ethanol supplementation and passages on (A-F) SCFAs, (G) total alkyl and (H) average chain length of maize straw fermented with ruminal fluid in vitro (CON: Control; ETH: with 200 mM of ethanol;1st: first generation; 8th: 8th generation).

Figure 2.

Effect of ethanol supplementation and passages on (A-F) SCFAs, (G) total alkyl and (H) average chain length of maize straw fermented with ruminal fluid in vitro (CON: Control; ETH: with 200 mM of ethanol;1st: first generation; 8th: 8th generation).

Early studies have shown that ethanol, as an electron donor, generates acetyl-CoA by supplying reducing equivalents like NADH and FADH₂. Acetyl-CoA is a key intermediate in the reverse β-oxidation (RBO) cycle for carbon chain elongation [

12,

27,

28,

29]. In our experiment, ethanol was metabolized by rumen microorganisms into intermediate products such as acetyl-CoA, which participated in caproate synthesis, thereby increasing caproate production. Since the carbon chain of caproate is longer than those of propionate and butyrate, etc., the average VFA chain length naturally extends as caproate production increases. Upon ethanol addition to the maize stover-rumen fluid fermentation, a similar RBO pathway may be activated, prompting microorganisms to convert more substrates into caproate while reducing propionate and butyrate production. Moreover, during subculturing, microorganisms continuously adapt to metabolic product changes and further adjust their metabolic pathways [

20,

30]. With the number of subcultures increases, microbial ethanol utilization efficiency improves, potentially yielding more caproate. Enhanced feedback inhibition amplifies the impact on valerate production and ACL, thus forming an interactive effect between ethanol addition and subculturing.

3.2. Microbial Community Analysis

3.2.1. Alpha and Beta Diversity Analysis

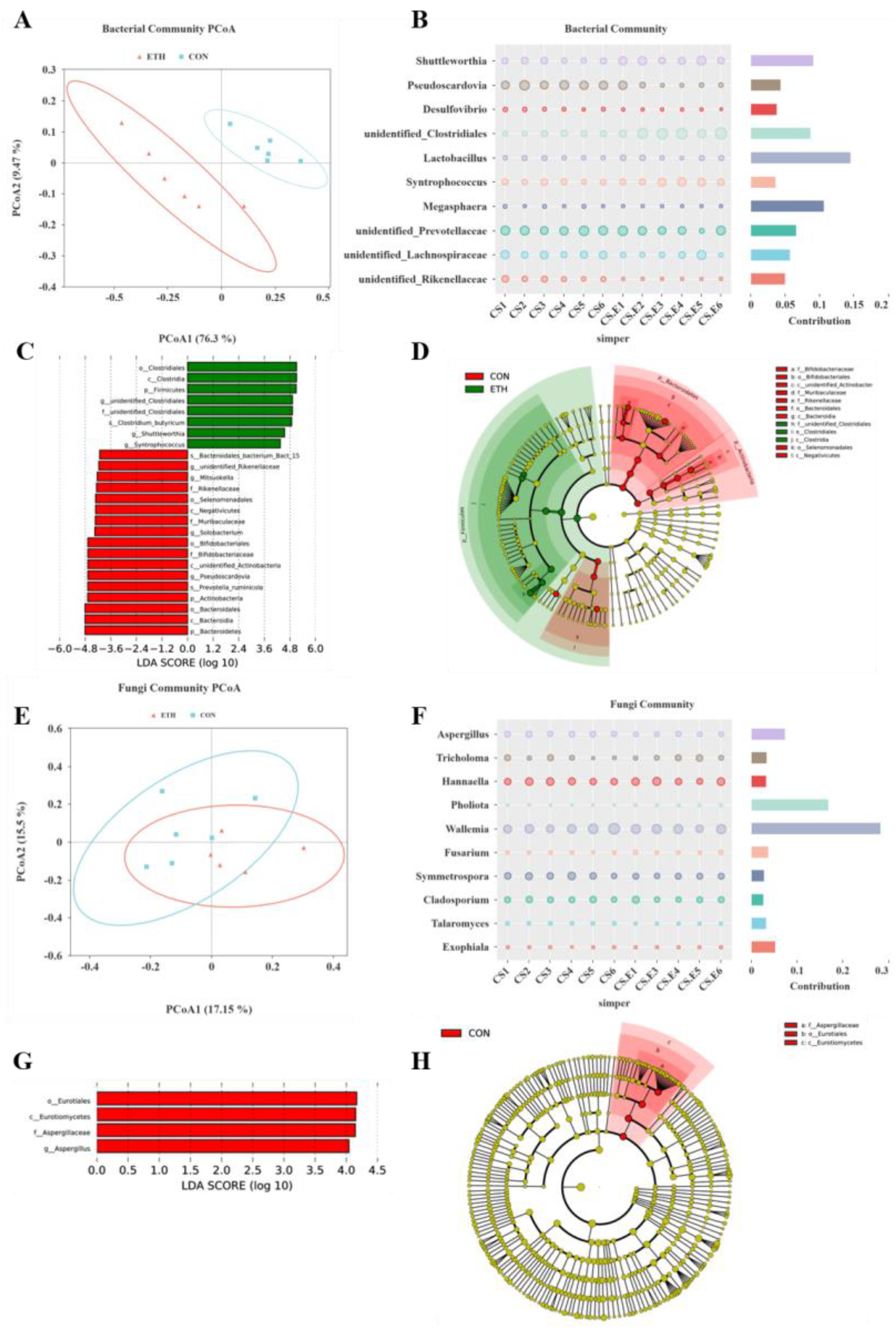

Ethanol significantly reduced the ACE, Chao 1, Shannon, and Simpson indices of bacteria (

Table 1). Overall, ethanol addition had no significant effect on fungal species richness (Ace and Chao1 indices) but significantly increased the fungal community’s Shannon diversity index (P = 0.035). This indicates that ethanol has a certain positive effect on fungal community diversity under the experimental conditions yet little impact on community dominance. It suggests that ethanol reduces bacterial species number and diversity, simplifying the community structure. PcoA results also show that ethanol remarkably alters the bacterial community structure in the fermentation broth but has no significant effect on the fungal community (

Figure 3A, and E). Additionally, certain species became dominant in the community, suppressing other species’ growth. This finding is consistent with our previous research on wheat straw and ethanol in vitro co-culture, where ethanol increased valeric and caproic acid production, and bacteria played a more crucial role than fungi [

21]. On the other hand, ethanol-caused reduction in bacterial richness and diversity implies that some bacteria could not survive [

20,

21,

31]. The decrease in pH and gas production might be associated with these changes in bacterial richness and diversity.

3.2.2. Community Structure of Bacteria and Fungi

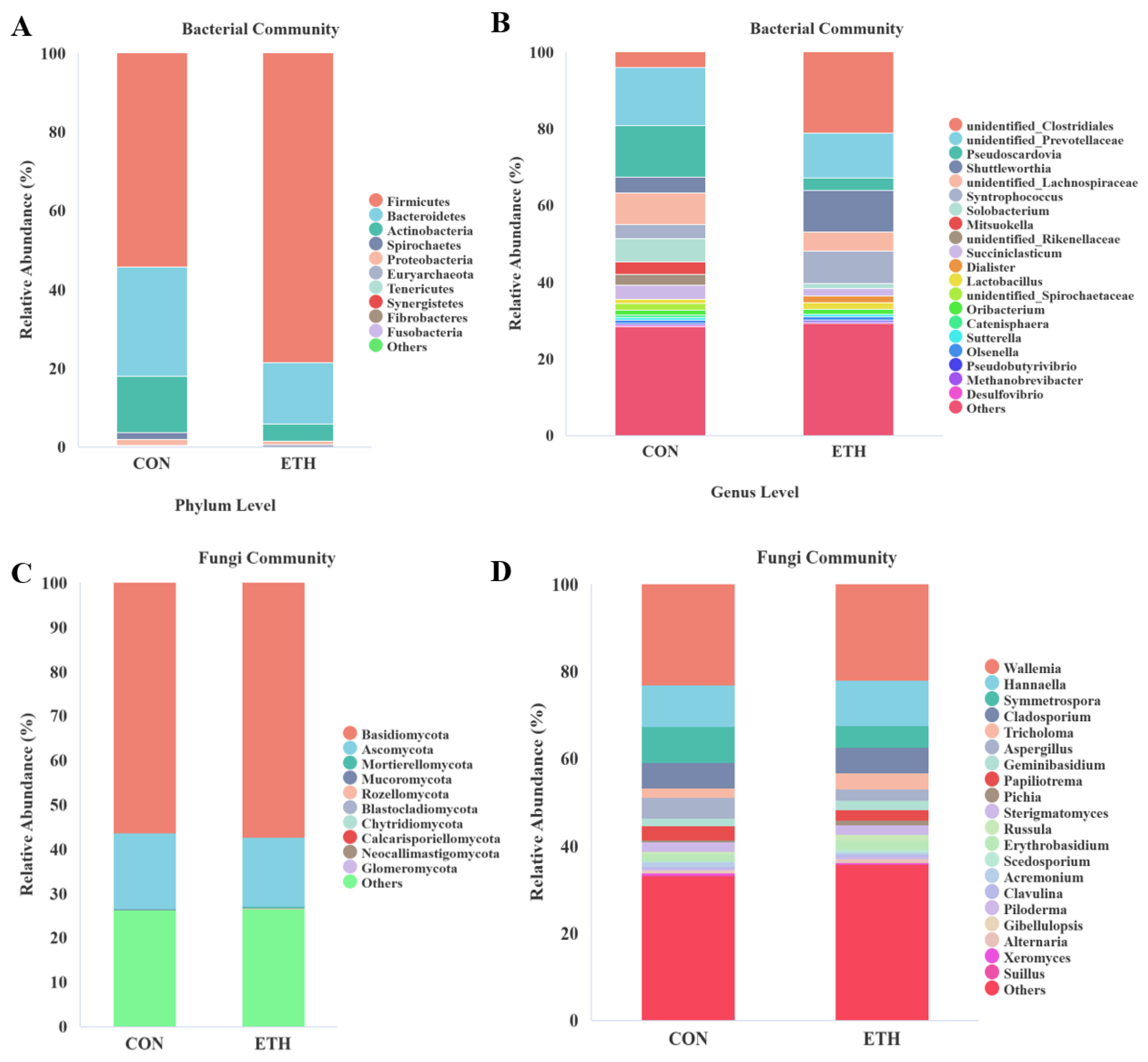

The top 10 most abundant bacterial and fungal phyla in terms of relative abundance are shown in

Figure 3A and C. Compared with the CON group, ethanol significantly increased the relative abundance of

Firmicutes (

P = 0.001) and significantly decreased those of

Bacteroidetes (

P = 0.009),

Actinobacteria (

P = 0.004), and

Spirochaetes (

P = 0.001). Ethanol had no significant effect on the relative abundances of

Basidiomycota (

P = 0.673) and

Ascomycota (

P = 0.454), the major components of the fungal community (

Table A1).

Firmicutes are often involved in carbohydrate metabolism during rumen fermentation;

Bacteroidetes play a role in polysaccharide degradation [

32,

33];

Actinobacteria can decompose complex organic substances (such as polysaccharides, cellulose, starch, chitin, etc.) and promote nutrient cycling [

34];

Spirochaetes act synergistically with other microorganisms (such as

Fibrobacteres) and participate in lignocellulose degradation [

35]. Such significant changes in dominant bacterial phyla indicate that ethanol can profoundly affect the bacterial metabolic networks and functions in fermentation.

The top 20 bacterial and fungal genera in terms of relative abundance are shown in

Figure 3B and D. Ethanol addition induced significant shifts in multiple genera within Firmicutes (

Table A2). Specifically, the relative abundances of

unidentified_Clostridiales (

P = 0.006),

Shuttleworthia (

P = 0.016), and

Syntrophococcus (

P = 0.043) were markedly higher in the ETH group than in the CON group, indicating their potential roles in ethanol-associated metabolic processes and specific fermentation pathways. In contrast, the relative abundances of

Solobacterium (

P < 0.001) and

Mitsuokella (

P = 0.01) were substantially lower in the ETH group, suggesting ethanol-mediated growth inhibition and potential disruption of their original functions in the fermentation system. Within Bacteroidetes, the abundance of

unidentified_Rikenellaceae (

P = 0.016) was significantly reduced in the ETH group, whereas

unidentified_Prevotellaceae abundance showed no significant difference (

P = 0.233). In

Actinobacteria and

Spirochaetes, the relative abundances of

Pseudoscardovia (

P = 0.004) and

unidentified_Spirochaetaceae (

P = 0.001) were notably lower in the ETH group, indicating ethanol strongly inhibited these genera and likely interfered with their roles in lignocellulose degradation and nutrient cycling. For the fungal community at the genus level, ethanol significantly reduced the relative abundance of

Symmetrospora (

Basidiomycota,

P = 0.044) in the ETH group, which may affect the metabolic functions of

Basidiomycota during fermentation. However, most

Basidiomycota genera (e.g.,

Wallemia [

P = 0.841],

Hannaella [

P = 0.682]) exhibited no significant differences, indicating their stability and ethanol resistance in the fermentation system. In

Ascomycota,

Aspergillus (

P = 0.002) and

Acremonium (

P = 0.008) showed substantially lower abundances in the ETH group, suggesting ethanol suppressed these genera and potentially altered metabolic processes such as substrate conversion. Overall, ethanol had a more limited impact on the fungal community at the genus level, with most genera showing stable abundances.

SIMPER analysis revealed that changes in

Lactobacillus,

Megasphaera,

Shuttleworthia, and

unidentified_Clostridiales were key drivers of bacterial community differentiation between groups;

Wallemia,

Pholiota, and

Aspergillus were the primary genera contributing to fungal community differences (

Figure 4B and F). LEfSe results further indicated that

unidentified_Clostridiales,

Shuttleworthia, and

Syntrophococcus were biomarker bacteria for the ETH group, while

Solobacterium,

Mitsuokella,

unidentified_Rikenellaceae, and

Pseudoscardovia characterized the CON group. Aspergillus emerged as the key taxon differentiating the fungal community structure (

Figure 4C, D, G, H).

Mechanistically, specific microorganisms utilize acetic, propionic, and butyric acids alongside ED (e.g., ethanol) to elongate carbon chains via fatty acid β-oxidation, generating valeric and caproic acids. Ethanol, as a critical ED for chain elongation, facilitates the production of medium-chain fatty acids [

36].

Clostridiales, a well-documented ethanol-utilizing taxon, drives caproic acid synthesis from acetic acid through reverse β-oxidation [

29,

37,

38]. Studies have shown that co-culturing

Clostridium kluyveri with ruminal bacteria accelerates carbon chain elongation and enhances caproic acid production [

12]. In this study,

unidentified_Clostridiales was the dominant genus in ethanol-driven caproate production, with a relative abundance of 20.97% in the ETH group (5.36-fold higher than CON).

Syntrophococcus (8.42% in ETH), capable of generating acetic acid from formic acid (a sugar oxidation product), provided essential precursors for caproate biosynthesis [

39].

Shuttleworthia, with a 160% increase in relative abundance in ETH, likely participates in ethanol-dependent caproic acid metabolism, further supporting the observed chain elongation.

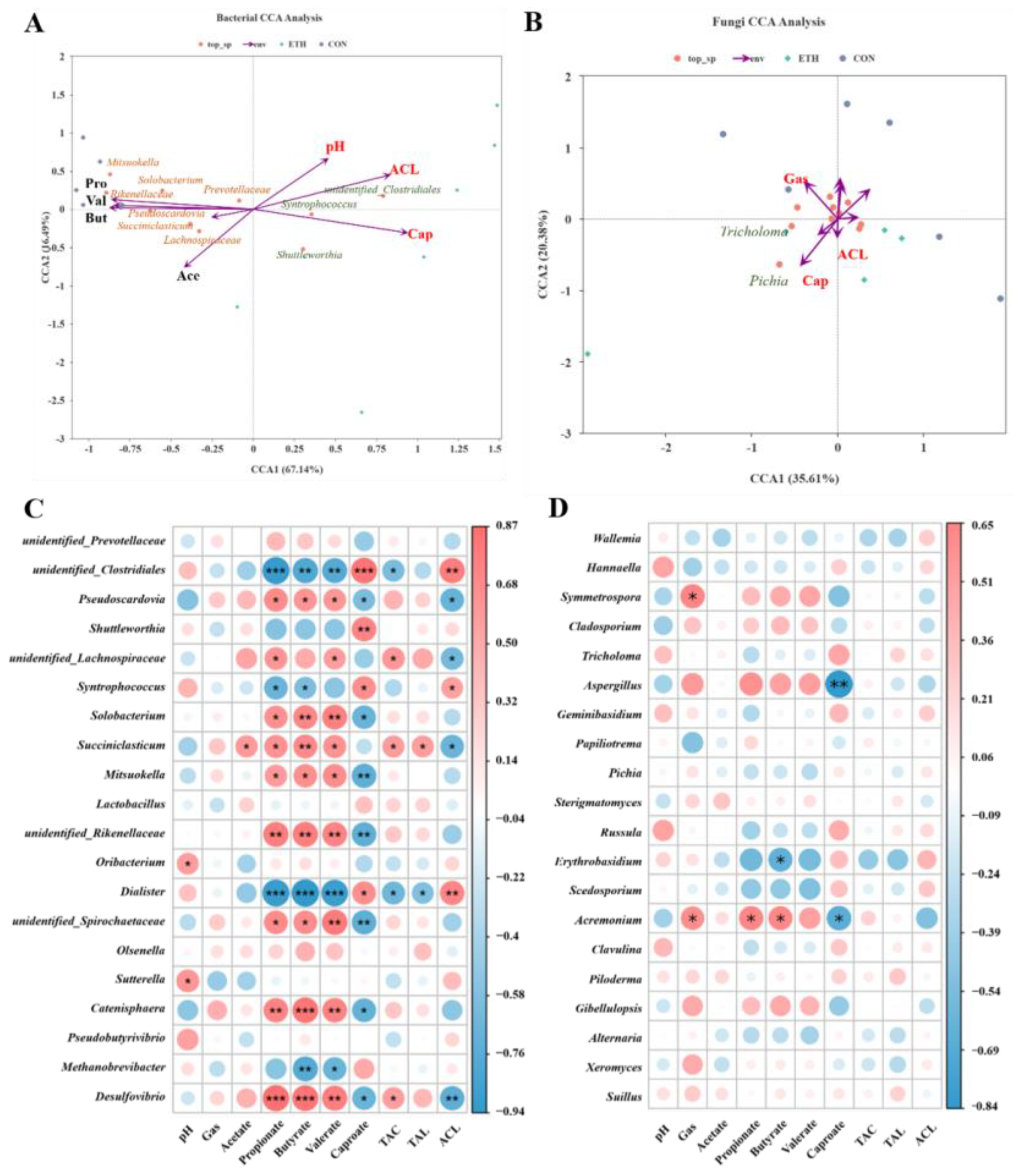

3.2.3. Correlation Between Microorganisms and Fatty Acid Production

To investigate the effects of ethanol on microbial community structure and its interaction with environmental factors, Canonical Correspondence Analysis (CCA) was performed. The results revealed that key bacterial genera including

unidentified_Clostridiales,

Syntrophococcus, and

Shuttleworthia were strongly associated with caproic acid and average chain length (ACL), whereas pH was a critical environmental factor shaping the bacterial community structure (

Figure 5A). Gas production-related parameters significantly influenced the fungal community structure, as shown in

Figure 5B.

To further clarify the associations between the microbial community and fermentation indicators, Spearman correlation analysis was conducted to examine relationships between microbial genera and fermentation parameters. The results indicated that the fungal community exhibited weaker correlations with fatty acid production compared to the bacterial community. Specifically,

Aspergillus (R = -0.836;

P = 0.001) and

Acremonium (R = -0.664;

P = 0.026) in

Ascomycota showed negative correlations with caproic acid production. However, no direct link between these fungi and caproic acid production has been reported previously, suggesting potential indirect effects through fermentation environmental changes or niche-community interactions (

Figure 5D).

Consistent with expectations, the bacterial community was closely associated with fatty acid production. In Firmicutes, unidentified_Clostridiales (R = 0.839; P < 0.001), Shuttleworthia (R = 0.748; P = 0.005), Syntrophococcus (R = 0.685; P = 0.014), and Dialister (R = 0.683; P = 0.014) exhibited significant positive correlations with caproate. Additionally, unidentified_Clostridiales (R = 0.797; P = 0.002), Syntrophococcus (R = 0.58; P = 0.048), and Dialister (R = 0.739; P = 0.006) were positively correlated with ACL, indicating their potential roles in caproic acid biosynthesis and carbon chain elongation. In contrast, Pseudoscardovia (Actinobacteria, R = -0.601; P = 0.039), Solobacterium (Firmicutes, R = -0.692; P = 0.013), Mitsuokella (Firmicutes, R = -0.741; P = 0.006), unidentified_Rikenellaceae (Firmicutes, R = -0.741; P = 0.006), and unidentified_Spirochaetaceae (Spirochaetes, R = -0.741; P = 0.006) showed negative correlations with caproate production, consistent with their low relative abundances in the ETH group. These observations may be attributed to ethanol-mediated antibacterial effects or poor adaptation to long-term in vitro subculturing. Notably, genera positively correlated with caproic acid production were negatively correlated with acetic, butyric, and valeric acid production, and vice versa, aligning with the fermentation results where ethanol promoted the elongation of short-chain fatty acids into caproic acid.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that after eight generations of in vitro domestication, rumen microorganisms can still facilitate short - chain fatty acid chain elongation in maize straw fermentation through electron donor addition, thereby enhancing caproic acid production. Key bacterial genera unidentified_Clostridiales, Shuttleworthia, and Syntrophococcus play critical roles in this process. Future studies should focus on isolating and purifying these microorganisms to validate their functional contributions to caproic acid production.

4. Conclusions

Adding ethanol during in vitro rumen fermentation inhibits the production of acetic and propionic acids while enhancing caproic acid biosynthesis. This study demonstrates that ethanol enables rumen microorganisms to convert acetic and propionic acids into caproic acid when maize stover serves as the fermentation substrate. Specifically, the bacterial genera unidentified_Clostridiales, Shuttleworthia, and Syntrophococcus stably utilize ethanol to facilitate caproic acid production across multiple generations of in vitro subculturing. Rumen fungi exhibit minimal effect on the carbon chain elongation of volatile fatty acids, with bacterial communities playing a dominant role in this process. Future studies should focus on optimizing the maize stover fermentation process to further enhance caproic acid yields, potentially through targeted enrichment of key functional bacteria or metabolic pathway modulation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.C. and M.L.; methodology, Z.C. and Y.S.; software, Z.C. and W.L.; validation, Z.C., Z.M. and L.L.; formal analysis, Z.C. and Z.M.; investigation, Z.C. and Y.S.; resources, G.Z. and M.L.; data curation, Z.C. and M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.C., Z.M. and L.L.; writing—review and editing, M.L., Y.S. and L.W.; visualization, Z.C., Z.M. and W.L.; supervision, Z.C. and M.L.; project administration, M.L. and Y.S.; funding acquisition, M.L. and Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research was funded by Shanghai Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Project (2024-02-08-00-12-F00023); the earmarked fund for CARS (CARS-36).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Yangzhou University (SYXK(Su)2016-0019).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

Effects of ethanol addition on the relative abundances of bacterial and fungal communities at the phylum level in in-vitro fermented maize straw (with an average relative abundance of at least one treatment ≥ 1 %).

Table A1.

Effects of ethanol addition on the relative abundances of bacterial and fungal communities at the phylum level in in-vitro fermented maize straw (with an average relative abundance of at least one treatment ≥ 1 %).

| Phylum |

Treatments |

p-value |

| CON |

ETH |

| Bacterial |

|

|

|

| Firmicutes |

54.11 ± 2.42 |

78.58 ± 5.01 |

0.001 |

| Bacteroidetes |

27.89 ± 1.99 |

15.58 ± 3.21 |

0.009 |

| Actinobacteria |

14.35 ± 1.40 |

4.31 ± 2.27 |

0.004 |

| Spirochaetes |

1.72 ± 0.26 |

0.08 ± 0.03 |

0.001 |

| Proteobacteria |

1.39 ± 0.18 |

0.82 ± 0.20 |

0.061 |

| Fungi |

|

|

|

| Basidiomycota |

56.39 ± 1.56 |

57.34 ± 1.47 |

0.673 |

| Ascomycota |

16.97 ± 1.02 |

15.59 ± 1.51 |

0.454 |

Table A2.

Effects of ethanol addition on the relative abundances of bacterial and fungal communities at the genus level in in-vitro fermented maize straw (with an average relative abundance of at least one treatment ≥ 0.5%).

Table A2.

Effects of ethanol addition on the relative abundances of bacterial and fungal communities at the genus level in in-vitro fermented maize straw (with an average relative abundance of at least one treatment ≥ 0.5%).

| Phylum |

Genus |

Treatments |

p-value |

| CON |

ETH |

| Bacterial |

|

|

|

|

| Firmicutes |

unidentified_Clostridiales |

3.91 ± 0.58 |

20.97 ± 3.75 |

0.006 |

| Shuttleworthia |

4.09 ± 0.62 |

10.7 ± 1.89 |

0.016 |

| unidentified_Lachnospiraceae |

8.27 ± 1.21 |

5.00 ± 2.29 |

0.237 |

| Syntrophococcus |

3.74 ± 0.50 |

8.42 ± 1.75 |

0.043 |

| Solobacterium |

5.98 ± 0.60 |

1.44 ± 0.29 |

<0.001 |

| Mitsuokella |

3.26 ± 0.79 |

0.03 ± 0.01 |

0.010 |

| Succiniclasticum |

3.60 ± 0.33 |

1.84 ± 0.60 |

0.027 |

| Dialister |

0.02 ± 0.00 |

1.77 ± 0.69 |

0.053 |

| Lactobacillus |

1.20 ± 0.23 |

1.75 ± 0.36 |

0.226 |

| Oribacterium |

1.36 ± 0.19 |

1.16 ± 0.25 |

0.547 |

| Bacteroidetes |

unidentified_Prevotellaceae |

15.29 ± 1.34 |

11.69 ± 2.5 |

0.233 |

| unidentified_Rikenellaceae |

2.88 ± 0.80 |

0.02 ± 0.01 |

0.016 |

| Actinobacteria |

Pseudoscardovia |

13.36 ± 1.42 |

3.41 ± 2.24 |

0.004 |

| Spirochaetes |

unidentified_Spirochaetaceae |

1.69 ± 0.26 |

0.08 ± 0.03 |

0.001 |

| Fungi |

|

|

|

|

| Basidiomycota |

Wallemia |

23.00 ± 4.00 |

22.00 ± 2.22 |

0.841 |

| Hannaella |

9.63 ± 0.95 |

10.42 ± 1.73 |

0.682 |

| Symmetrospora |

8.24 ± 1.27 |

4.93 ± 0.22 |

0.044 |

| Tricholoma |

2.11 ± 0.85 |

3.78 ± 1.2 |

0.274 |

| Geminibasidium |

1.75 ± 0.82 |

2.08 ± 0.56 |

0.762 |

| Papiliotrema |

3.11 ± 0.34 |

2.52 ± 0.71 |

0.452 |

| Sterigmatomyces |

2.18 ± 0.37 |

2.04 ± 0.43 |

0.810 |

| Erythrobasidium |

1.48 ± 0.41 |

2.18 ± 0.20 |

0.184 |

| Russula |

0.64 ± 0.29 |

1.37 ± 0.57 |

0.259 |

| Ascomycota |

Cladosporium |

5.84 ± 0.46 |

5.82 ± 1.32 |

0.984 |

| Aspergillus |

4.83 ± 0.23 |

2.58 ± 0.49 |

0.002 |

| Acremonium |

1.13 ± 0.14 |

0.47 ± 0.13 |

0.008 |

| Pichia |

0.51 ± 0.15 |

1.03 ± 0.64 |

0.403 |

References

- Langsdorf, A.; Volkmar, M.; Holtmann, D.; Ulber, R. Material Utilization of Green Waste: A Review on Potential Valorization Methods. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2021, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, Y.Z.; Liu, Y.P.; Li, X.J.; Wang, K.S.; Yuan, H.R. Improving Biodegradability and Biogas Production of Corn Stover through Sodium Hydroxide Solid State Pretreatment. Energy Fuels 2008, 22, 2761–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi-Banji, A.A.; Rahman, S.; Cihacek, L.; Nahar, N. Comparison of the Reactor Performance of Alkaline-Pretreated Corn Stover Co-Digested with Dairy Manure Under Solid-State. Waste Biomass Valor 2020, 11, 5211–5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Wang, X.; Yuan, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Wang, G.; Liu, Y. Fed-Batch Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Alkaline Organosolv-Pretreated Corn Stover Facilitating High Concentrations and Yields of Fermentable Sugars for Microbial Lipid Production. Biotechnol Biofuels 2020, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Hernández, J.E.; Loera, O.; Méndez-Hernández, E.M.; Herrera, E.; Arce-Cervantes, O.; Soto-Cruz, N.Ó. Fungal Pretreatment of Corn Stover by Fomes Sp. EUM1: Simultaneous Production of Readily Hydrolysable Biomass and Useful Biocatalysts. Waste Biomass Valor 2019, 10, 2637–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Cai, D.; Zhao, G. Co-Generation of Ethanol and l-Lactic Acid from Corn Stalk under a Hybrid Process. Biotechnol Biofuels 2018, 11, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherzadeh, M.; Karimi, K. Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Wastes to Improve Ethanol and Biogas Production: A Review. IJMS 2008, 9, 1621–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, N.-J.; Park, G.W.; Kang, J.; Kim, Y.-C.; Chang, H.N. Volatile Fatty Acid Production from Lignocellulosic Biomass by Lime Pretreatment and Its Applications to Industrial Biotechnology. Biotechnol Bioproc E 2013, 18, 1163–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, W.; Zhang, D.; Wang, H. Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) Production from Fermented Thermal-Hydrolyzed Sludge by Mixed Microbial Cultures: The Link between Phosphorus and PHA Yields. Waste Management 2019, 96, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Loh, K.-C.; Kuroki, A.; Dai, Y.; Tong, Y.W. Microbial Biodiesel Production from Industrial Organic Wastes by Oleaginous Microorganisms: Current Status and Prospects. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 402, 123543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S.J.; Candry, P.; Basadre, T.; Khor, W.C.; Roume, H.; Hernandez-Sanabria, E.; Coma, M.; Rabaey, K. Electrolytic Extraction Drives Volatile Fatty Acid Chain Elongation through Lactic Acid and Replaces Chemical pH Control in Thin Stillage Fermentation. Biotechnol Biofuels 2015, 8, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weimer, P.J.; Nerdahl, M.; Brandl, D.J. Production of Medium-Chain Volatile Fatty Acids by Mixed Ruminal Microorganisms Is Enhanced by Ethanol in Co-Culture with Clostridium Kluyveri. Bioresource Technology 2015, 175, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayané, A.; Guiot, S.R. Animal Digestive Strategies versus Anaerobic Digestion Bioprocesses for Biogas Production from Lignocellulosic Biomass. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol 2011, 10, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noel, S.J.; Attwood, G.T.; Rakonjac, J.; Moon, C.D.; Waghorn, G.C.; Janssen, P.H. Seasonal Changes in the Digesta-Adherent Rumen Bacterial Communities of Dairy Cattle Grazing Pasture. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S. The Application of Biotechnology on the Enhancing of Biogas Production from Lignocellulosic Waste. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2016, 100, 9821–9836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nerdahl, M.A.; Weimer, P.J. Redox Mediators Modify End Product Distribution in Biomass Fermentations by Mixed Ruminal Microbes in Vitro. AMB Expr 2015, 5, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante, W. de A.; Leitão, R.C.; Gehring, T.A.; Angenent, L.T.; Santaella, S.T. Anaerobic Fermentation for N-Caproic Acid Production: A Review. Process Biochemistry 2017, 54, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Wu, L.; Wei, W.; Ni, B.-J. Insights into the Microbiomes for Medium-Chain Carboxylic Acids Production from Biowastes through Chain Elongation. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 2022, 52, 3787–3812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spirito, C.M.; Richter, H.; Rabaey, K.; Stams, A.J.; Angenent, L.T. Chain Elongation in Anaerobic Reactor Microbiomes to Recover Resources from Waste. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2014, 27, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Dai, X.; Weimer, P.J. Shifts in Fermentation End Products and Bacterial Community Composition in Long-Term, Sequentially Transferred in Vitro Ruminal Enrichment Cultures Fed Switchgrass with and without Ethanol as a Co-Substrate. Bioresource Technology 2019, 285, 121324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Feng, L.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, K. Effect of Ethanol or Lactic Acid on Volatile Fatty Acid Profile and Microbial Community in Short-Term Sequentially Transfers by Ruminal Fermented with Wheat Straw in Vitro. Process Biochemistry 2021, 102, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menke, K.H.; Raab, L.; Salewski, A.; Steingass, H.; Fritz, D.; Schneider, W. The Estimation of the Digestibility and Metabolizable Energy Content of Ruminant Feedingstuffs from the Gas Production When They Are Incubated with Rumen Liquor in Vitro. J. Agric. Sci. 1979, 93, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Schaefer, D.M.; Zhao, G.Q.; Meng, Q.X. Effects of Nitrate Adaptation by Rumen Inocula Donors and Substrate Fiber Proportion on in Vitro Nitrate Disappearance, Methanogenesis, and Rumen Fermentation Acid. Animal 2013, 7, 1099–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Z.; Meng, Z.; Tan, D.; Datsomor, O.; Zhan, K.; Lin, M.; Zhao, G. Effects of Supplementation of Sodium Acetate on Rumen Fermentation and Microbiota in Postpartum Dairy Cows. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1053503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.-S.; Strik, D.P.B.T.B.; Buisman, C.J.N.; Kroeze, C. Production of Caproic Acid from Mixed Organic Waste: An Environmental Life Cycle Perspective. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 7159–7168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Bao, X.; Guo, W.; Wang, B.; Li, Y.; Luo, H.; Wang, H.; Ren, N. Medium Chain Carboxylic Acids Production from Waste Biomass: Current Advances and Perspectives. Biotechnology Advances 2019, 37, 599–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Liu, Z.; Varrone, C.; Zhou, A.; He, Z.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Liu, W.; Yue, X. Elucidating the Microbial Ecological Mechanisms on the Electro-Fermentation of Caproate Production from Acetate via Ethanol-Driven Chain Elongation. Environmental Research 2022, 203, 111875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, M.; Liu, L.; Fan, H.; Li, N.; Pan, H.; Hrynsphan, D.; Tatsiana, S.; Robles-Iglesias, R.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J. Advancements in Chain Elongation Technology: Transforming Lactic Acid into Caproic Acid for Sustainable Biochemical Production. Bioresource Technology 2025, 425, 132312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ma, H.; Gao, M.; Qian, D.; Wang, Q.; Liu, L. Production of Caproate from Lactate by Chain Elongation under Electro-Fermentation: Dual Role of Exogenous Ethanol Electron Donor. Bioresource Technology 2025, 424, 132272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Cheng, Z.; Zong, Y.; Shen, Y.; Jama, S.M.; Lin, M. Enrichment of Rumen Solid-Phase Bacteria for Production of Volatile Fatty Acids by Long-Term Subculturing In Vitro. Fermentation 2025, 11, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickdam, E.; Khiaosa-ard, R.; Metzler-Zebeli, B.U.; Klevenhusen, F.; Chizzola, R.; Zebeli, Q. Rumen Microbial Abundance and Fermentation Profile during Severe Subacute Ruminal Acidosis and Its Modulation by Plant Derived Alkaloids in Vitro. Anaerobe 2016, 39, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, M.; Zhu, S.; Xue, M.-Y.; Chen, H.; Xu, J.; Song, M.; Tang, Y.; Liu, X.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, T.; et al. Single-Cell Transcriptomics across 2,534 Microbial Species Reveals Functional Heterogeneity in the Rumen Microbiome. Nat Microbiol 2024, 9, 1884–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizrahi, I.; Wallace, R.J.; Moraïs, S. The Rumen Microbiome: Balancing Food Security and Environmental Impacts. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021, 19, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazarika, S.N.; Thakur, D. Actinobacteria. In Beneficial Microbes in Agro-Ecology; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 443–476. ISBN 978-0-12-823414-3. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Rui, J.; Pei, Z.; Sun, X.; Zhang, S.; Yan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zheng, T.; Li, X. Straw- and Slurry-Associated Prokaryotic Communities Differ during Co-Fermentation of Straw and Swine Manure. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2014, 98, 4771–4780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chwialkowska, J.; Duber, A.; Zagrodnik, R.; Walkiewicz, F.; Łężyk, M.; Oleskowicz-Popiel, P. Caproic Acid Production from Acid Whey via Open Culture Fermentation – Evaluation of the Role of Electron Donors and Downstream Processing. Bioresource Technology 2019, 279, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandra Harahap, B.; Ahring, B.K. Caproic Acid Production from Short-Chained Carboxylic Acids Produced by Arrested Anaerobic Digestion of Green Waste: Development and Optimization of a Mixed Caproic Acid Producing Culture. Bioresource Technology 2024, 414, 131573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, H.; Wu, P.; Li, J.; Zhang, J. Clostridium Kluyveri Enhances Caproate Production by Synergistically Cooperating with Acetogens in Mixed Microbial Community of Electro-Fermentation System. Bioresource Technology 2023, 369, 128436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiguchi, Y. Syntrophococcus. In Bergey’s Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria; Whitman, W.B., Ed.; Wiley, 2015; pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-1-118-96060-8. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).