1. Introduction

Entropic forces are emergent forces that arise from the statistical tendency of a system to increase its entropy[

1,

2]. Unlike other fundamental forces (like gravity or electromagnetism), entropic forces originate from the system’s tendency to maximize the number of accessible microstates [

3]. Entropic origin of these forces represents the tendency of a system to evolve into a more probable state, rather than simply into one of lower potential energy [

1]. Elasticity of polymers is driven to a much extent by entropy [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Maximizing entropy of a polymer chain implies reducing the distance between its two free ends. Consequently, an entropic elastic force emerges, that tends to collapse the chain. Elasticity of the muscles arises from entropy in a way very similar to the entropy-driven elasticity of polymer chains [

8]. Entropic forces drive contraction of cytoskeletal networks [

9]. Verlinde suggested that gravity is actually the entropic force [

10]. According to Verlinde, gravity emerges from fundamental principles of statistical mechanics and information theory rather than being a fundamental interaction like electromagnetism. His idea is rooted in holographic principle and thermodynamics [

10]. Verlinde showed that if information about matter is stored on a holographic screen (a surface encoding information about space), then the tendency of entropy to maximize leads to an effect that mimics Newton’s law of gravity [

10]. In a similar way the Coulomb interaction was treated as an entropic force [

11].

Usually, entropic forces grow with temperature, however, the exceptions to this rule were reported, when the system of elementary magnets supposed to be in the thermal equilibrium with the thermal bath is exposed to external magnetic field [

12]. A diversity of polymer materials demonstrate entropic elasticity, including rubber [

13], Polydimethylsiloxane PDMS [

14] and thermoplastic elastomers [

15,

16]. Entropic elasticity is inherent for tropocollagen, which is the building block of collagen fibrils and fibers that provide mechanical support in connective tissues [

17]. Entropic elasticity was observed in slide-ring gels [

18]. Somewhat surprisingly, entropic elasticity was reported in cubic crystals of

[

19].

Our paper addresses the situation when the entropic/polymer spring gives rise to the effect of the negative mass. The effect of the negative mass is a resonance effect, emerging in core-shell mechanical systems. This effect occurs when the frequency of the harmonic external force acting on core-shell system connected by a Hookean massless spring, approaches from above to the eigen-frequency of the system [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Negative-inertia converters for both translational and rotational motion were introduced [

25].

The energy of the vibrated core-shell system is not conserved, due to the fact that it is exposed to the external harmonic force, as it occurs, for example, in the famous Kapitza pendulum, in which the pivot point vibrates in a vertical direction, up and down [

26,

27]. 2020). Unlike the Kapitza pendulum, the effect of “negative effective mass” arises in the linear approximation to the analysis of the motion [

20,

21,

22,

28]. The effect of the negative effective mass/negative effective density may be achieved with the plasma oscillations of the free electron gas in metals [

29,

30,

31].

The effects of negative mass and negative density gave rise to the novel mechanic and thermal metamaterials [

32,

33,

34]. The negative effective mass materials were manufactured by dispersion of soft silicon rubber coated heavy spheres in epoxy, acting as the mechanical resonators [

20]. The negative density metamaterial was manufactured in an aluminum plate, comprising the resonant structure [

35]. Soft 3D acoustic metamaterials polymer materials demonstrating negative effective density were reported [

36]. Our paper is devoted to the possibility of realization of negative mass/density metamaterials exploiting entropic elastic forces.

2. Materials and Methods

Numerical calculations were performed with the Wolfram Mathematica software.

3. Results

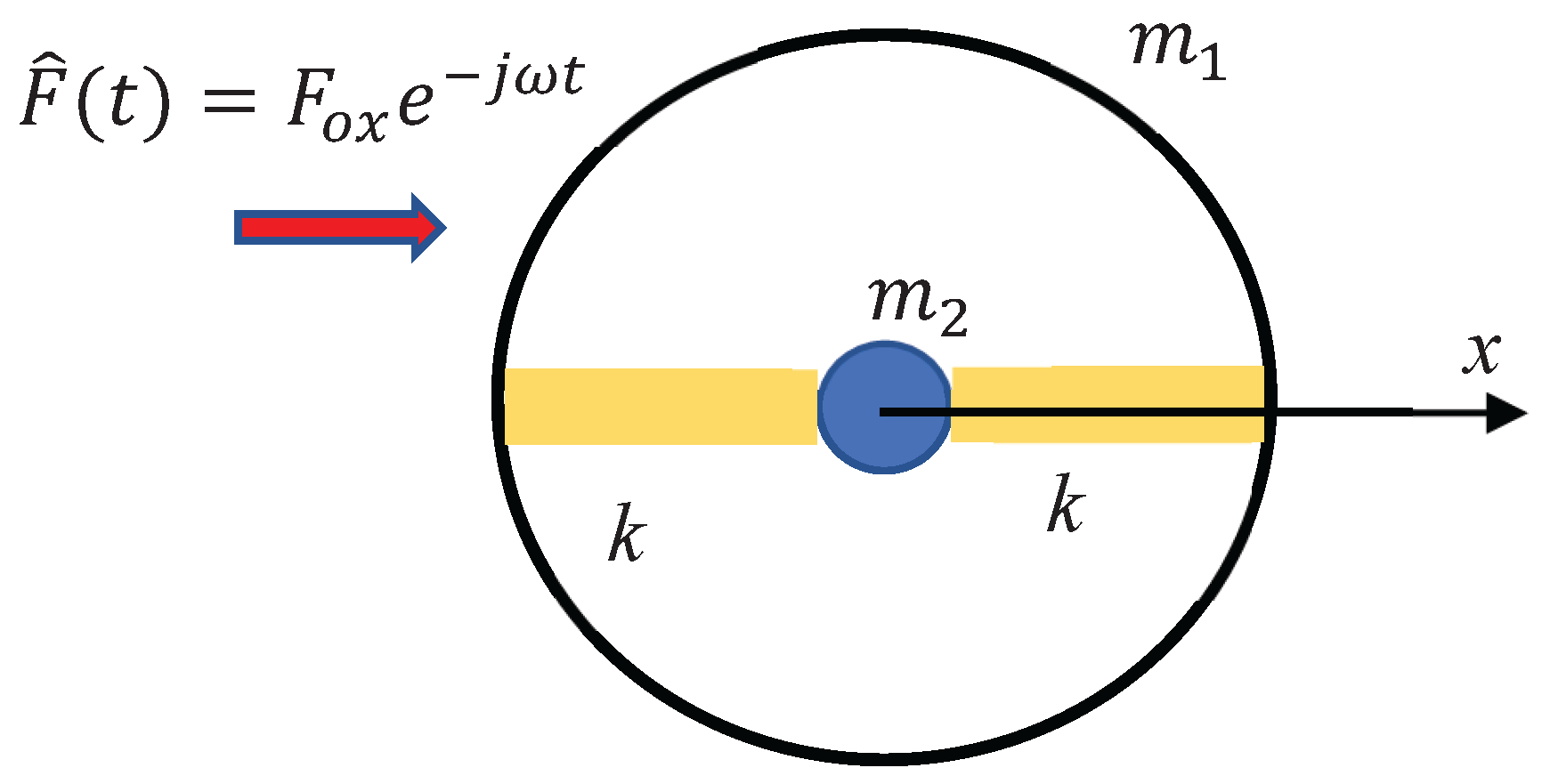

3.1. Negative Mass in the Core-Shell System Driven by Entropic Elastic Force

Consider the core-shell mechanical system, depicted in

Figure 1. The core mass

is connected to the shell

with two polymer stripes/springs. The entire system is subjected to the external sinusoidal force

, as shown in

Figure 1. We assume that the masses of the polymer stripes are much smaller than both masses of the core and shell; thus, the masses of polymer springs are negligible. The core-shell system may be replaced with a single effective mass

expressed with Eq. 1 (for the rigorous derivation of Eq. 1, see: [

23,

24,

28,

29].

where

, and

k is the elastic constant of the polymer stripe (the core mass is driven by the pair of polymer springs).

It is easily seen from Eq. 1 that, when the frequency ω approaches

from above, the effective mass

will be negative [

21,

22,

28,

29] . For the sake of simplicity we assume that the polymer stripe/spring is built of

ξ identical polymer chains, each of which may be represented by the ideal Kuhn equivalent freely jointed chain, built of

N Kuhn monomers, the length of the Kuhn segment is

b [

5]. The elastic constant

k of the polymer spring is given by Eq. 2:

where

is the Boltzmann constant, and

T is the temperature; we assume that the temperature is constant along the addressed core-shell system [

5]. Substitution of Eq. 2 into Eq. 1 yields for the effective mass of the entire core-shell system (the masses of the polymer springs are neglected):

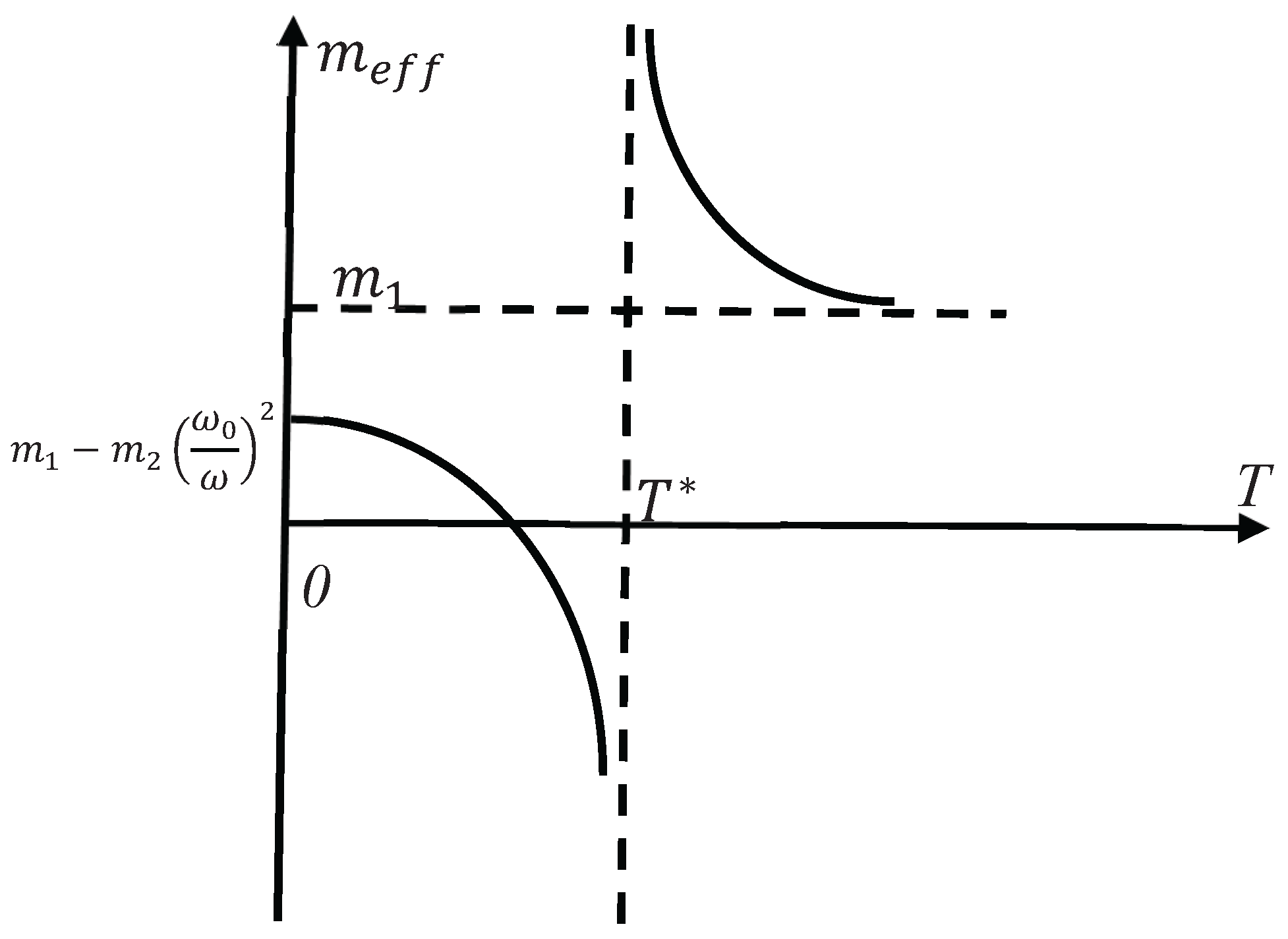

Now we fix the frequency of the external force

ω, and vary the temperature of the core-shell system

T. It is easily seen, that the effective mass

becomes negative when the temperature of the core-shell system approaches the critical temperature

from below, where

is given by Eq. 4:

The dependence

is presented in

Figure 2 (the value of ω is fixed). It is instructive to calculate the asymptotic values of

. When,

we derive from Eq 3.

which is intuitively clear for an infinitively stiff spring. The low-temperature limit of the effective mass is also easily calculated.

Eq. 7 is also intuitively clear; indeed, the influence of the “weak” polymer spring (the temperatures are low) becomes negligible.

3.2. Negative Density of the Chain of Core-Shell Systems Driven by Elastic Forces

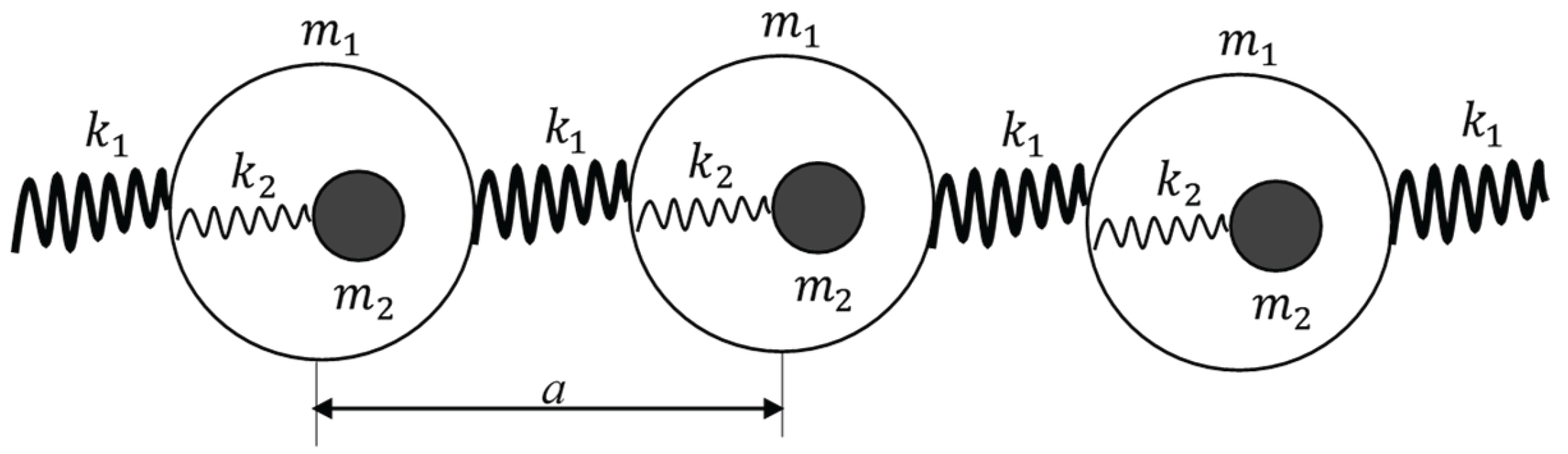

The concept of negative resonant density emerging in the chain of core-shell units, depicted in

Figure 3, was introduced [

29]. The effective density of the chain depicted in

Figure 3;

, was calculated in [

29]; and it is given by Eq. 8:

where

and

are the masses of the shell and core correspondingly, the linear density of the chain

is given by:

;

and

;

; and

a is the lattice constant (see

Figure 3),

. It was demonstrated that the effective density becomes negative, when the frequency of external force

ω approaches

from above [

29].

Now we assume that both of the springs are polymer stripes. The elasticity of the stripes is given by Eqs. 9-10 [

5]:

where

are the numbers and parameters of the Kuhn chains, constituting the strings,

. It is noteworthy that the parameter;

is temperature-independent. Thus, the squared resonant frequency

is given by Eq. 11:

where

. Hence, the effective density of the chain appears as follows:

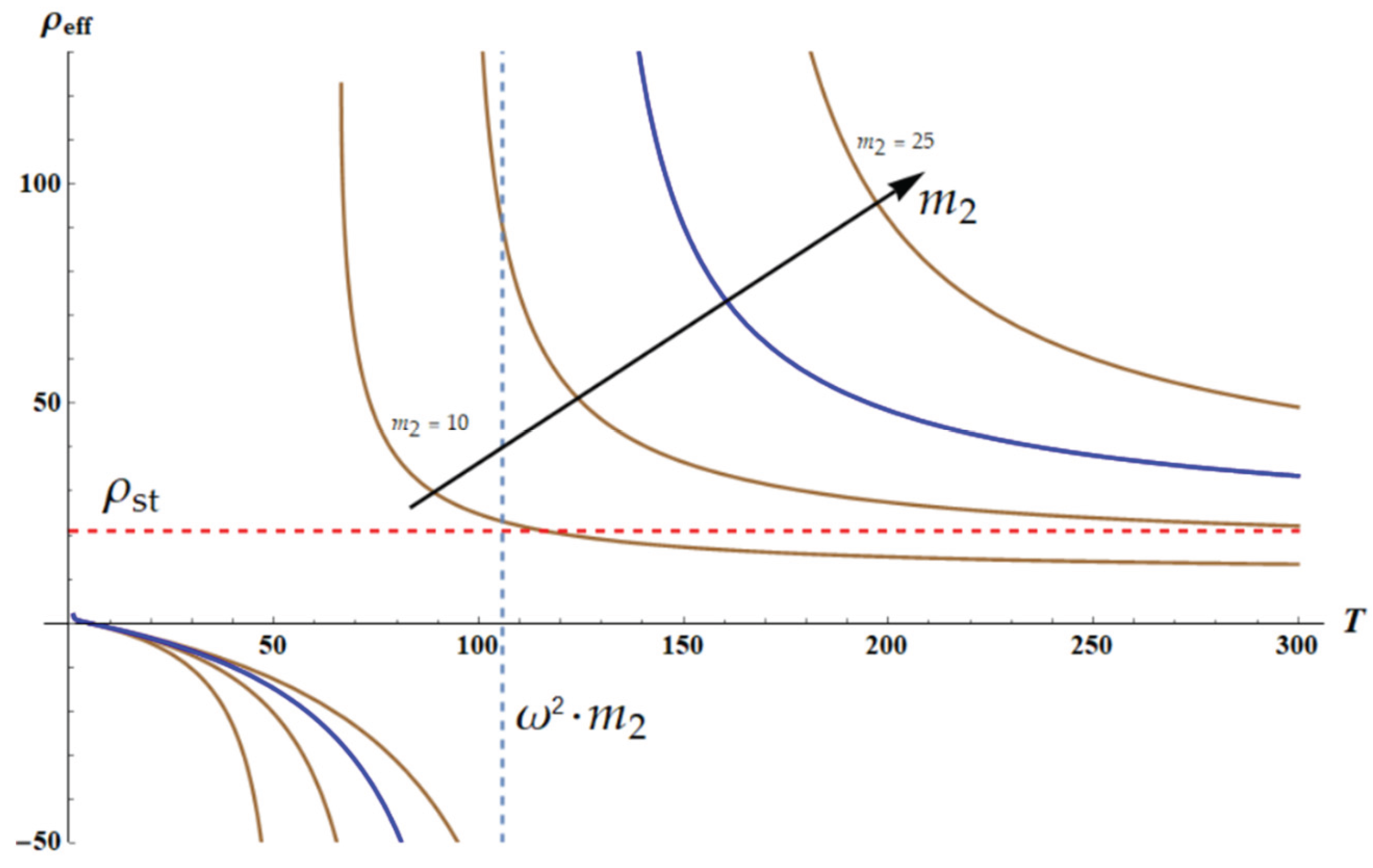

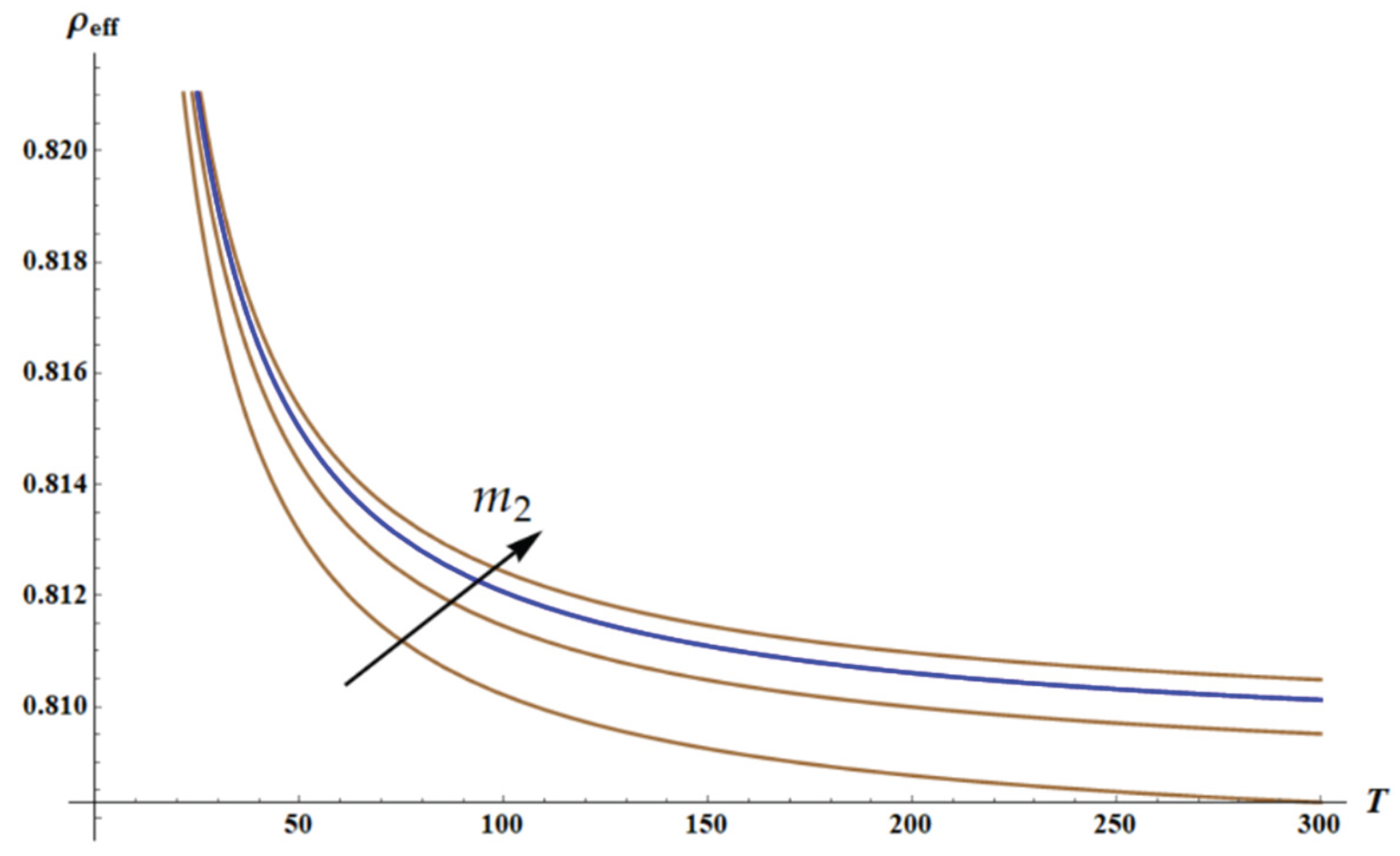

Now we fix the frequency of the external force

ω. The plot

is depicted in

Figure 4. The graph is numerically built with Wolfram Mathematica software. The blue curve depicts the dependence

for the dimensionless parameters:

.

It is recognized that

becomes negative, when the temperature of the core-shell system approaches to the critical temperature

from below, where

is given by Eq. 13:

where

. Set of the brown curves, appearing in

Figure 4, depicts the temperature dependencies of the effective density

calculated for the different values of

. It is easily demonstrated that the high-temperature limit of the effective density is given by Eq. 14:

which is well-expected for the massless, infinitely stiff springs.

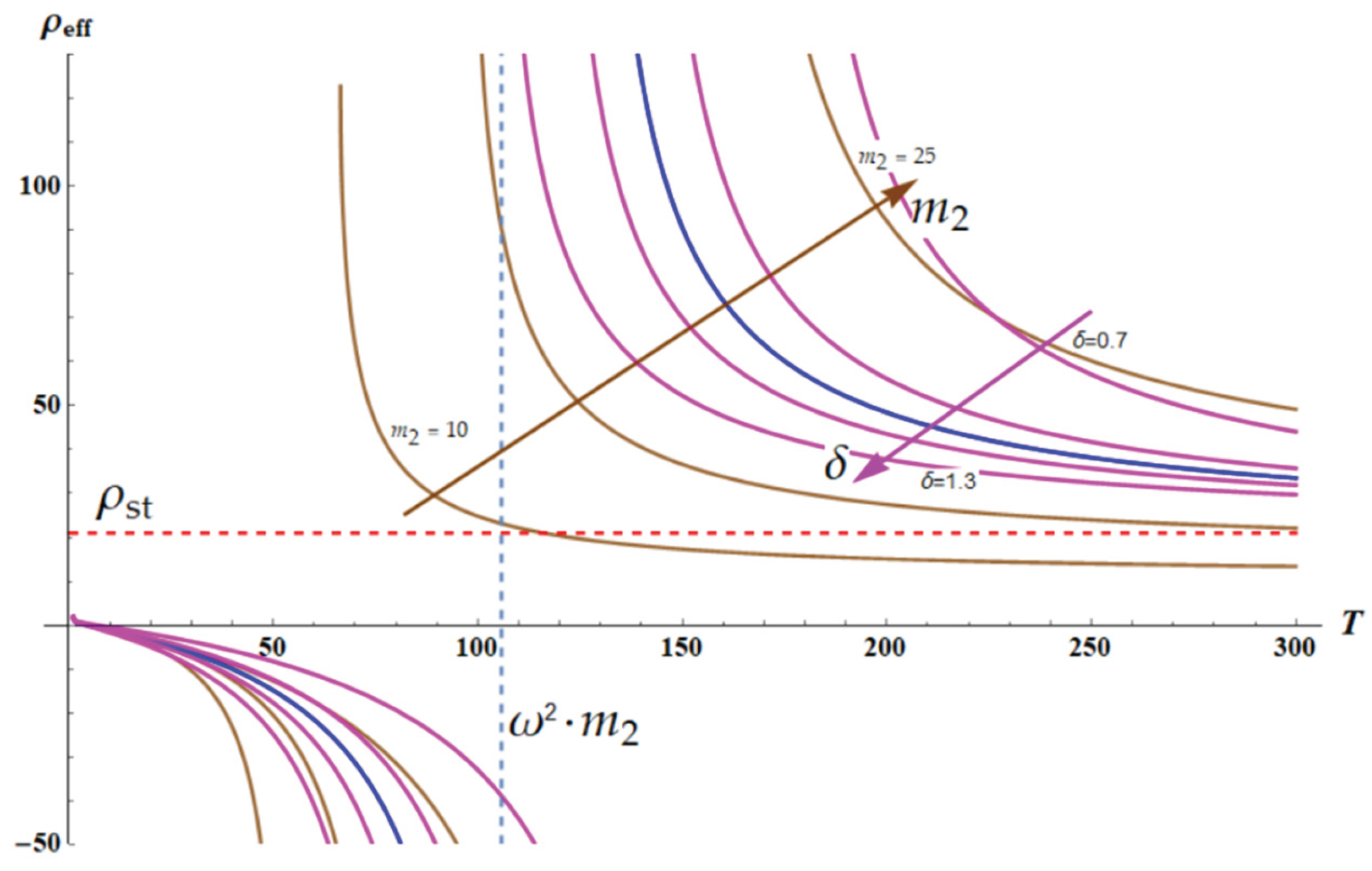

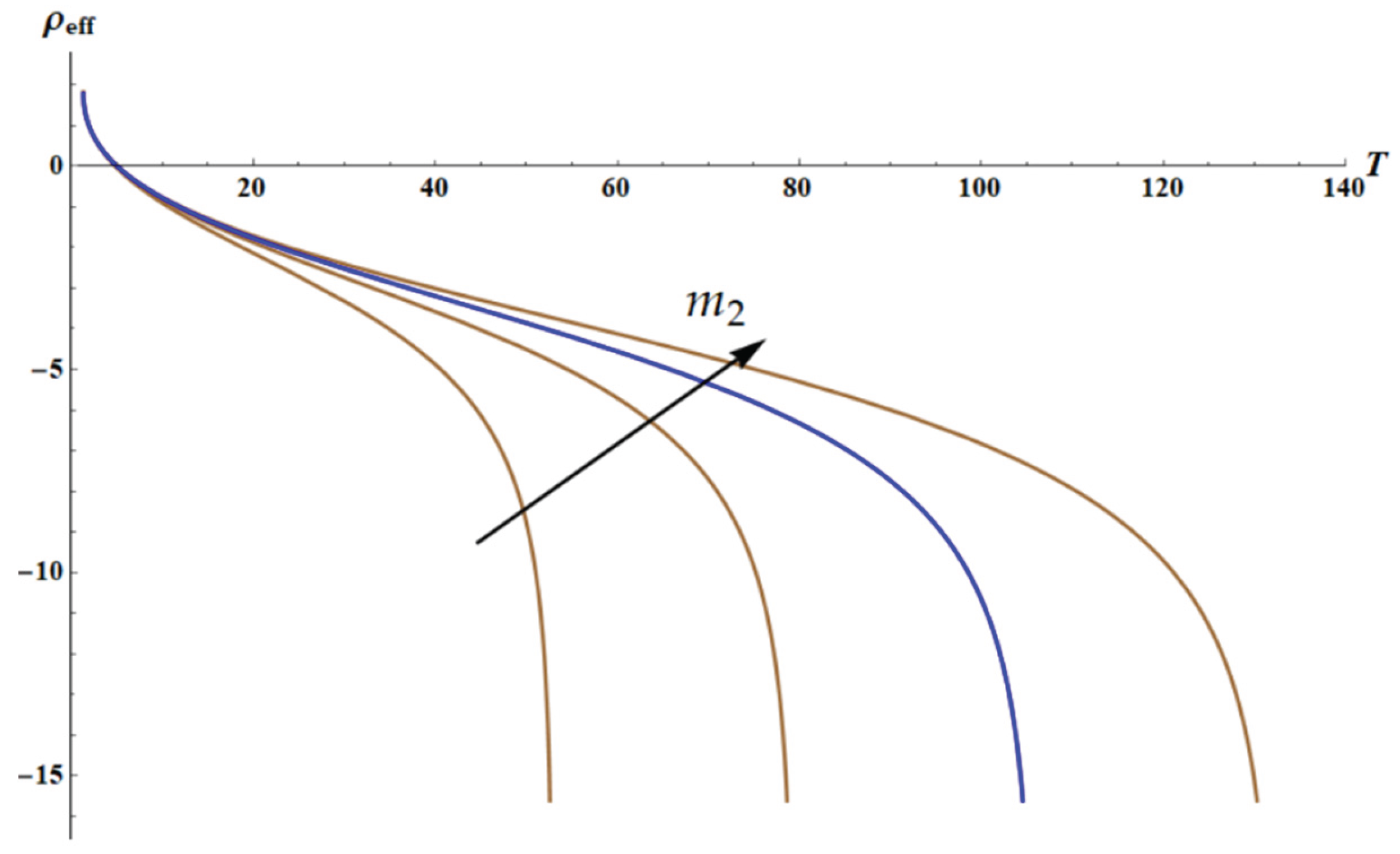

Let’s vary the parameter

in Eq. 8 in the range less and greater than one, namely

. Parameter

quantifies relative stiffness of spring

referred to the string

The variation of parameters

and

is illustrated with

Figure 5. Brown curves are built for the fixed

and demonstrate change of

with

for

. Magenta curves, in turn, illustrate are built for fixed

and

.

Figure 5 illustrates the very important result, increase in

leads to the sharpening of the resonance behavior of

dependence. This result is intuitively quite understandable; indeed, the decrease in stiffness of the outer spring

results in the sharpening of the resonance.

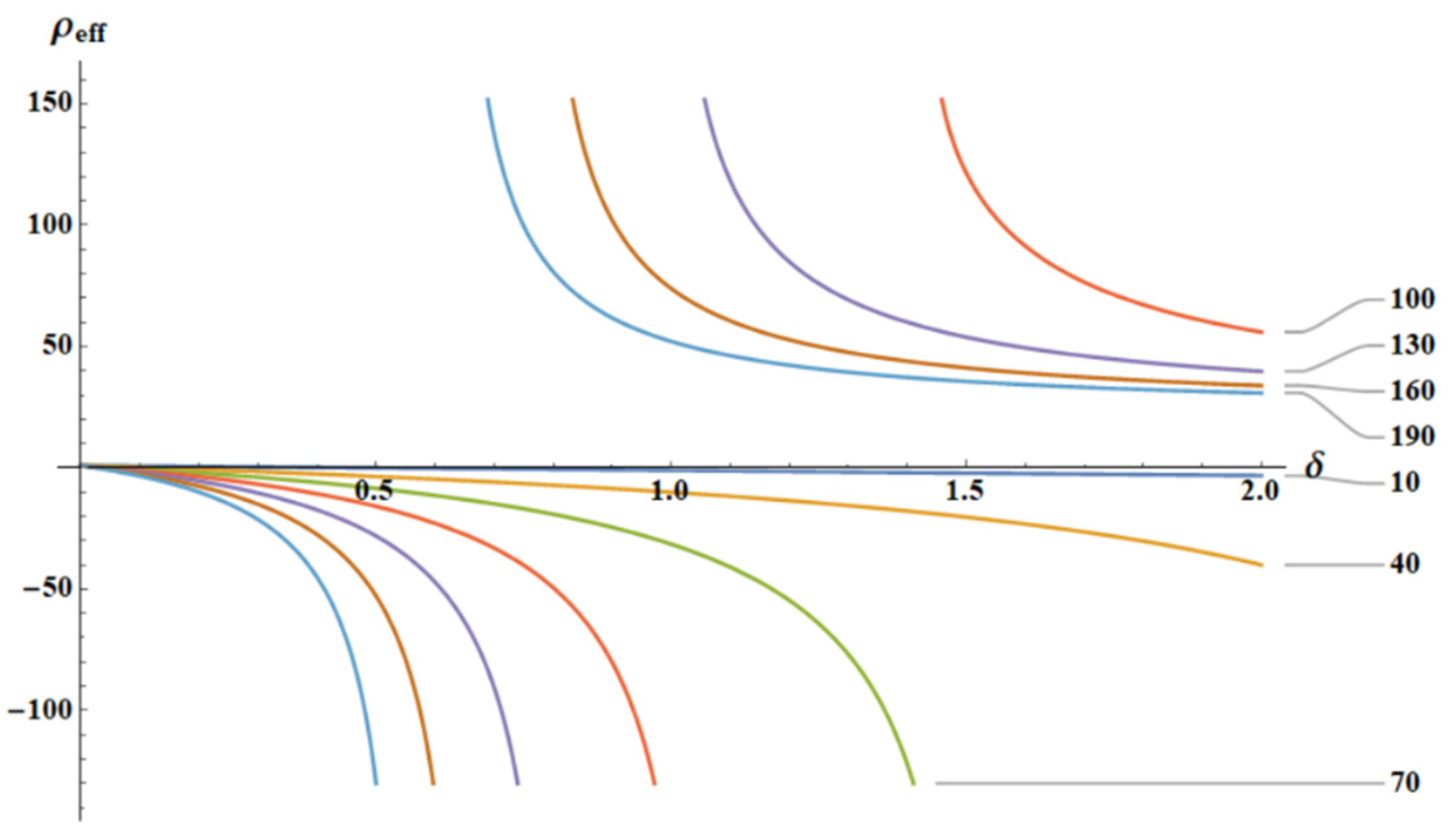

The dependence

as calculated for different temperatures is depicted in

Figure 6. In the low temperature limit, when

and,

the effective density

almost doesn’t change with

, as it is illustrated with

Figure 6.

Now we address a situation, when we remove the temperature dependence of the elasticity of the stripes (Eqs 9-10) one by one. The first case:

. Then Eq. 8 with dimensionless parameters will transform to Eq. 15:

The dependence

calculated for the different values of parameter

is illustrated with

Figure 7.

The second case corresponds to

. Then Eq. 8 with dimensionless parameters will transform to Eq. 16:

The dependence

calculated for the different values of parameter

is illustrated with

Figure 8.

The field of negative densities is clearly recognized in

Figure 8.

3.3. Dispersion Equations: Influence of the Temperature

The dispersion equation for the 1D lattice (

Figure 3) is given by [

29,

30,

31]:

Considering, as earlier, the dimensionless parameters:

Eq. 17 yields:

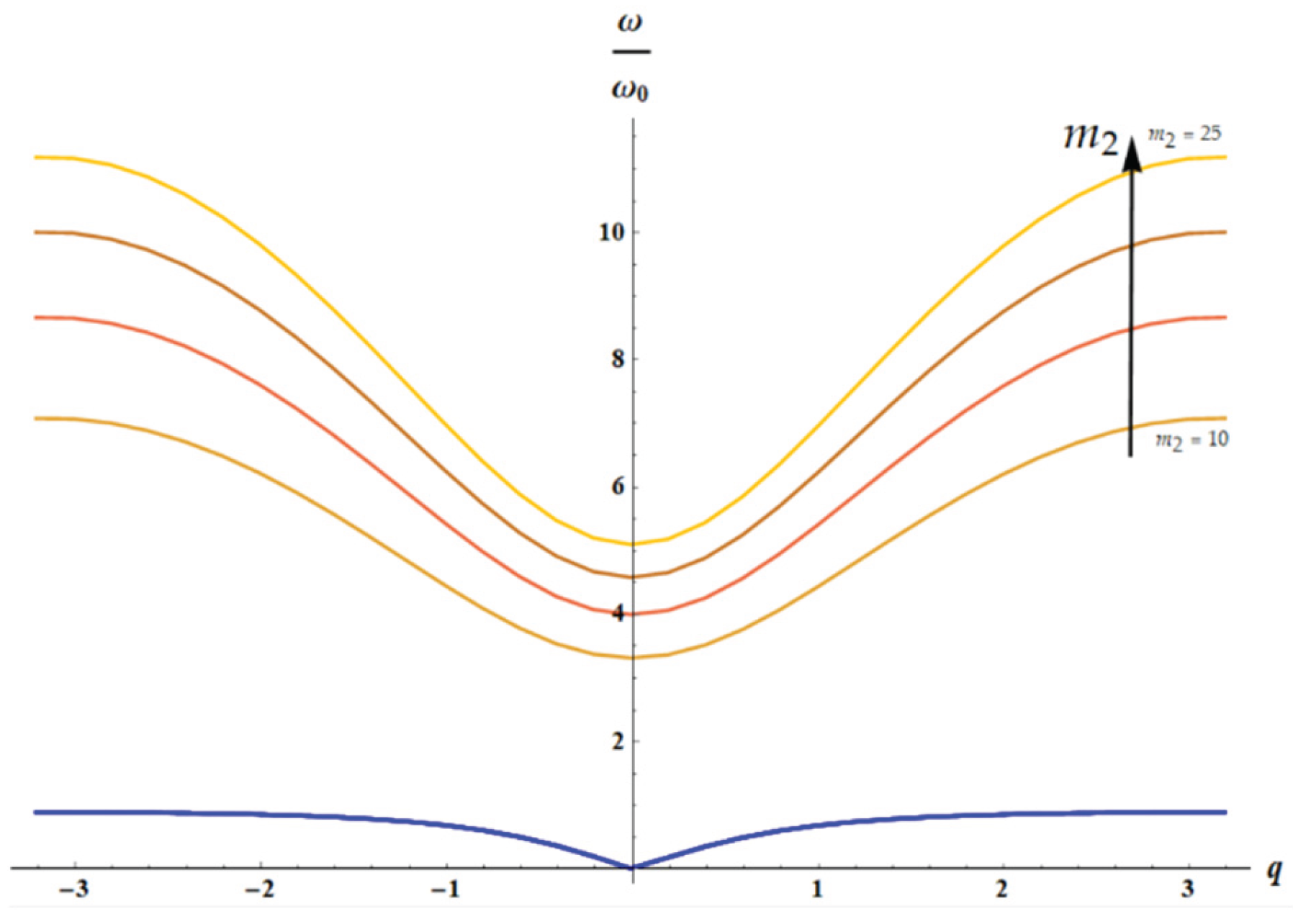

For

(both of springs are entropic) we have:

It is clear that the solution of the dispersion equation (

Figure 9) does not depend on temperature for

Let’s consider two cases (only spring is entropic) and (only spring is entropic).

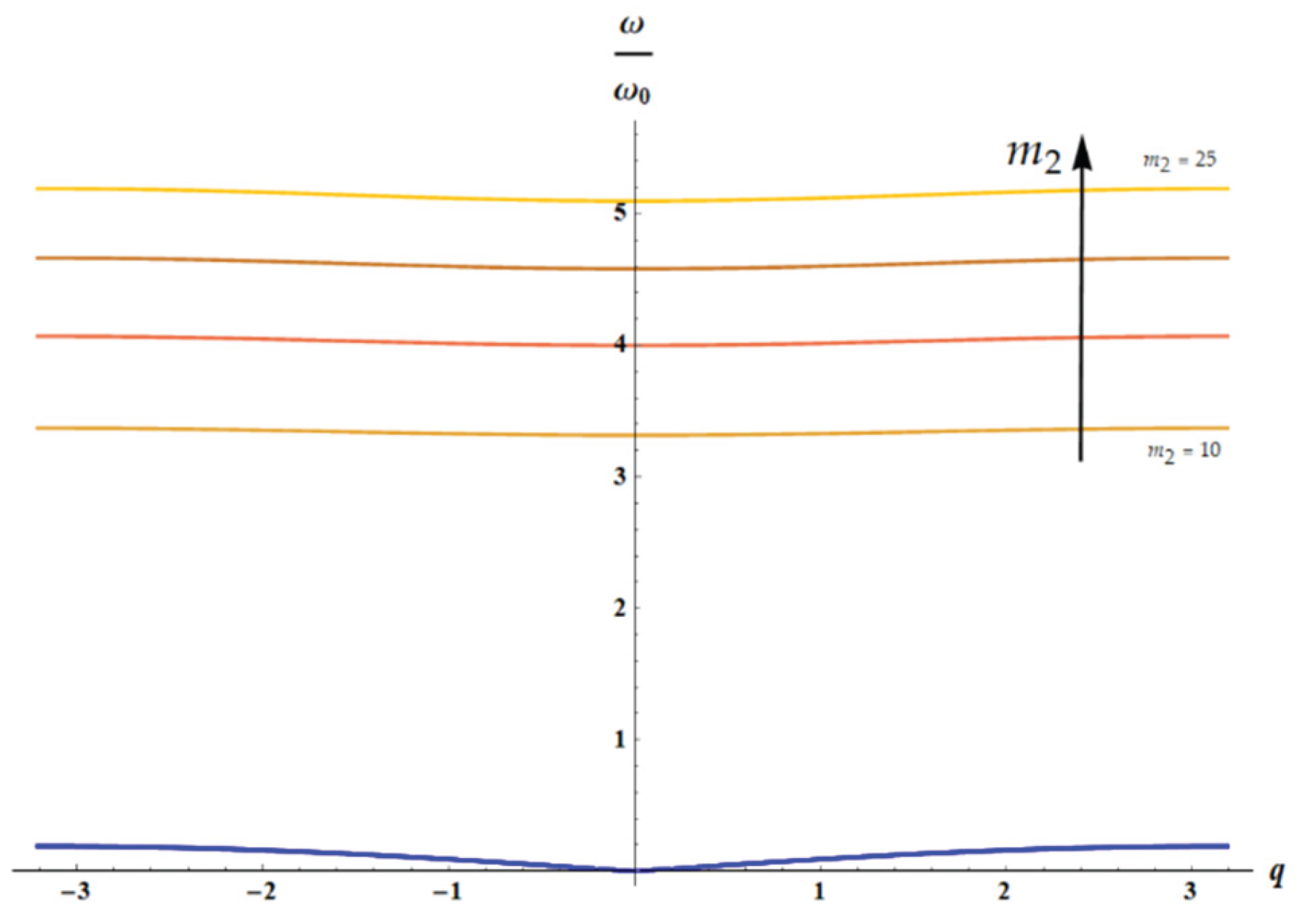

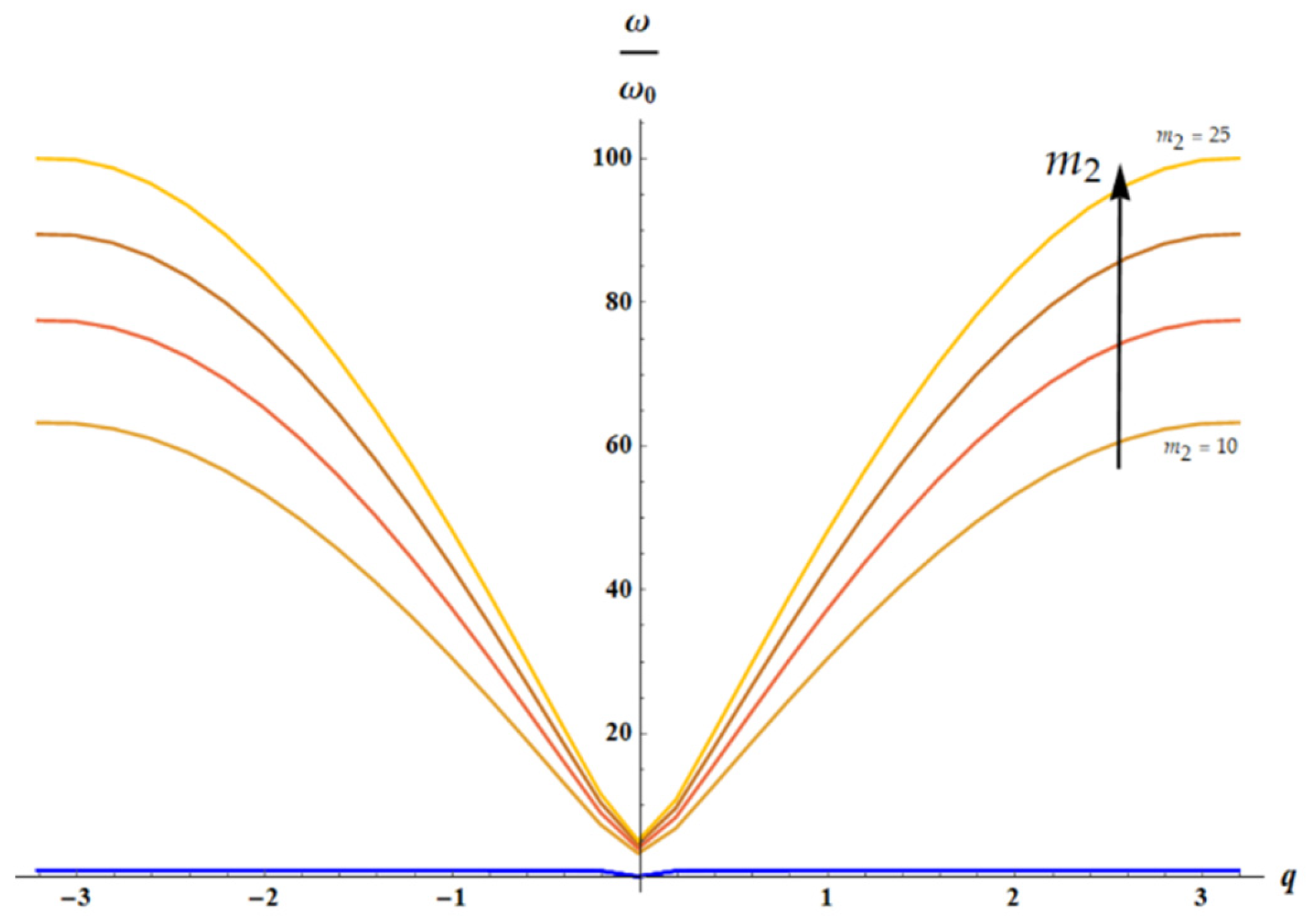

Figure 10.

The solution of dispersion equation (Eq. 18) for is depicted: acoustic (blue curves) and optical branches (from brown () to orange () curve), calculated for . The arrow indicates the direction of increase in parameter value.

Figure 10.

The solution of dispersion equation (Eq. 18) for is depicted: acoustic (blue curves) and optical branches (from brown () to orange () curve), calculated for . The arrow indicates the direction of increase in parameter value.

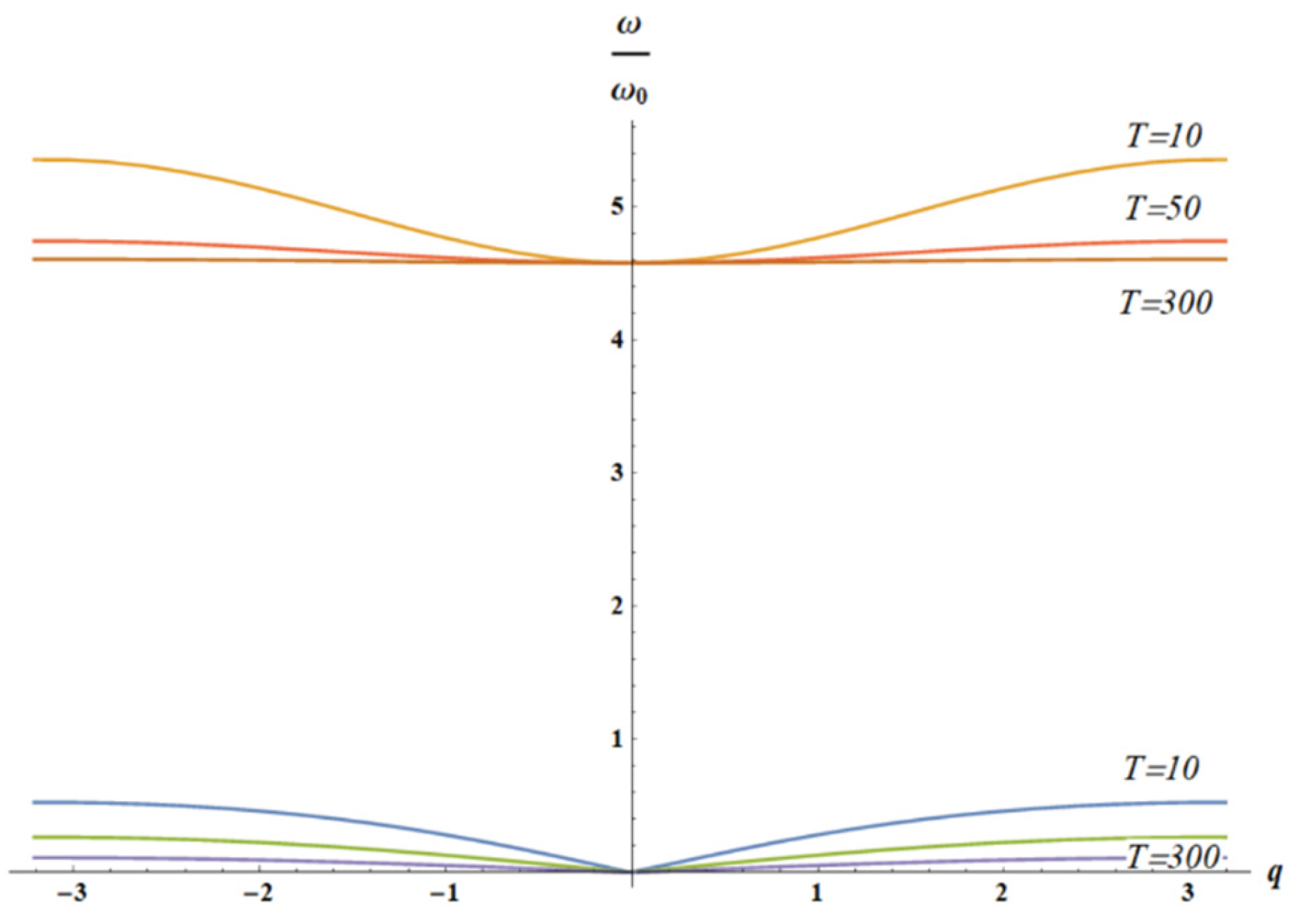

Figure 11.

The solution of dispersion equation (Eq. 18) for is depicted. Here . It is evident that with increasing temperature T both acoustic (blue, green and purple) and optical branches (orange, red, brown) depend weakly on the wave vector q.

Figure 11.

The solution of dispersion equation (Eq. 18) for is depicted. Here . It is evident that with increasing temperature T both acoustic (blue, green and purple) and optical branches (orange, red, brown) depend weakly on the wave vector q.

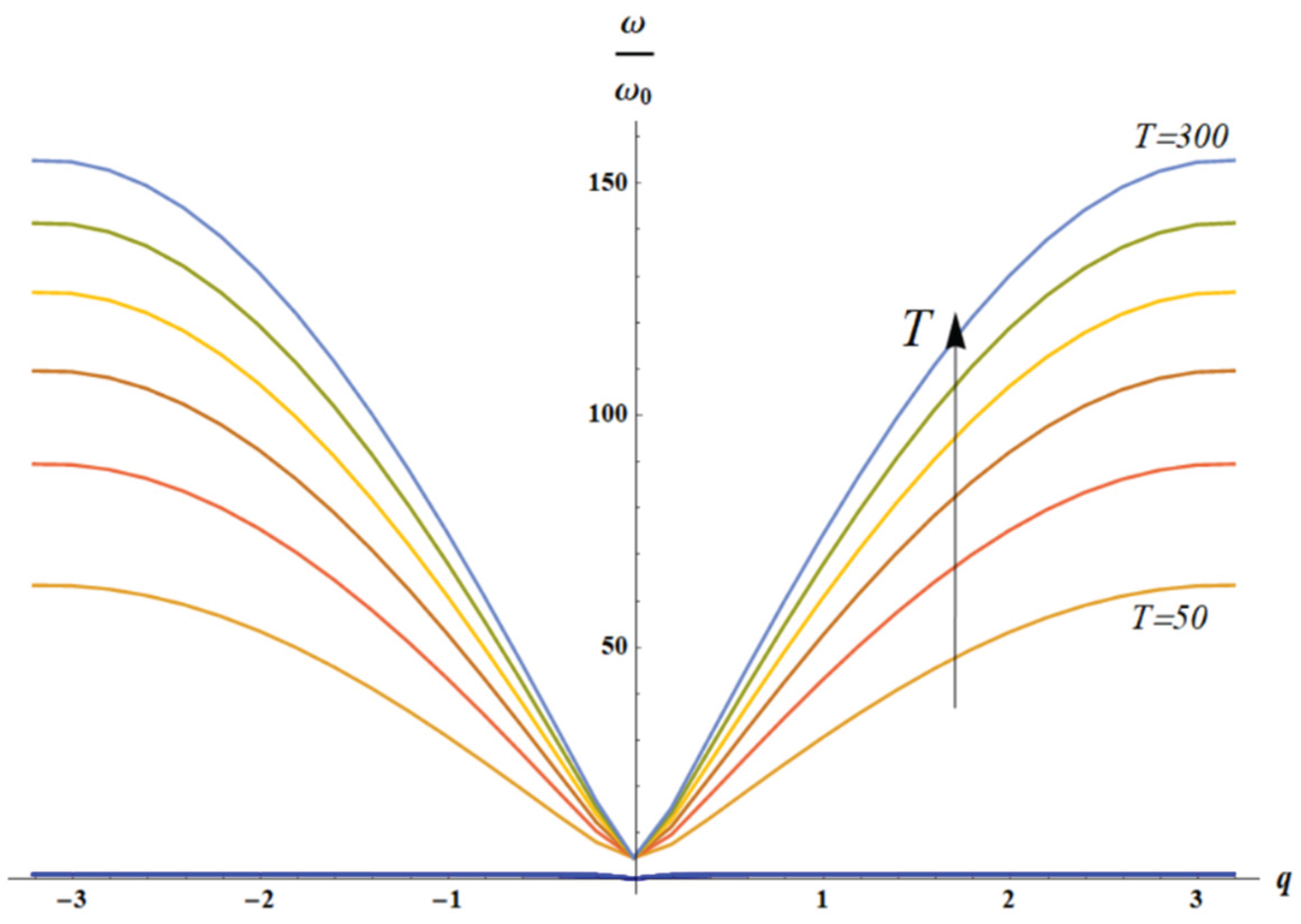

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 illustrate the situation, when optical branch of the vibrations is strongly temperature-dependent; whereas, acoustic branch is slightly temperature dependent.

4. Discussion

Resonances are ubiquitous in nature and engineering [

37,

38,

39]. It is well known, that the resonant phenomena may be temperature dependent. The temperature dependence of the resonance frequency of the fundamental and four higher order modes of a silicon dioxide micro-cantilever was established [

40]. Temperature effects in resonant Raman spectroscopy were registered [

41]. Temperature dependent Raman resonant response in

was reported [

42]. The temperature dependence of the Fano resonance discovered in infrared spectra of nano-diamonds was discussed [

43]. We address the temperature dependent resonant effects giving rise the phenomenon of the “negative effective mass effect”, exerted to the intensive research in the last decade.

It is unnecessary to say that actually there is no negative mass [

29,

44,

45]. The phenomenon of the “negative effective mass” arises when we substitute the core-shell mechanical systems comprising a pair of masses (

M and

m) and the massless Hookean spring

k by a single effective mass

, that is to say that the internal mass

m is hidden and its influence is expressed by the introduction of the mass

[

21,

22,

23,

29,

44]. The negative effective mass represents the contra-intuitive situation of “anti-vibrations”, when the harmonic acceleration of the system is in an opposite direction to the sinusoidal applied force [

21,

22,

23,

28,

29]. We considered the situation when the vibrations are driven by temperature-dependent entropic forces, inherent for natural and biological polymer systems [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

46]. The stiffness of the polymer spring is temperature-dependent, and the physical situation resembling the parametric resonance emerges, when the temperature is varied [

45]. Thus, the temperature-dependent effective mass emerges. The effect may be exemplified with polymer acoustic meta-materials [

36,

47]. The temperature dependent effective mass is not a novel concept; it is broadly used in semiconductors [

48]. However, in our analysis the effect of temperature dependent mass emerges from the entropic origin of the elastic force in resonant systems.

The engineering realization of suggested approach may be realized with rubbers or thermoplastic elastomers [

14,

15,

16]. Negative density materials exploiting thermoplastic materials were already reported [

49]. In particular, negative mass system/waveguide based on styrene butadiene rubber were introduced [

50]. These systems have a potential for the temperature-dependent negative mass behavior.

5. Conclusions

We conclude that the effect of the temperature-dependent effective mass becomes possible in the core-shell systems in which the spring connecting the core mass to the shell is driven by the temperature-dependent entropic elasticity, such as that inherent for polymer materials. The core-shell system may be replaced with a single effective mass exposed to the external harmonic force. When the frequency of the external force ω is fixed and the temperature of the core-shell system T is varied, the resonance becomes possible, and the harmonic acceleration of the shell may move in an opposite direction to the applied force. We demonstrate that the effective mass becomes negative when the temperature of the core-shell system approaches to the critical temperature from below.

We also considered the chain/lattice built of core-shell units, in which entropic forces are acting. In this case, the effect of “negative density” is attainable under variation the temperature of the system. Again, the negative density becomes negative when the temperature of the core-shell system approaches the critical temperature from below. The critical temperature is defined by the parameters of polymer chain and frequency of the external force ω. We varied the parameters of the lattice built of the core-shell elements and connected with the elastic springs. Increase in the stiffness of the springs connecting the core-shell units, leads to the sharpening of the resonance behavior of dependence. We also addressed a situation, and calculated the resonance curves, when we removed the temperature dependence of the elasticity of the “inner” and “outer” elastic elements one by one. In the low temperature limit, the effective density almost doesn’t change with the ratio of the elastic constants of the “internal” and “external springs” appearing in the lattice. . Optical and acoustical branches of vibrations are calculated. The effect may be demonstrated experimentally with polymer meta-materials.

Author Contributions

Edward Bormashenko: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft preparation. Artem Gilevich: Formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft preparation. Shraga Shoval: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, writing—original draft preparation.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to anonymous reviewers for extremely fruitful reviewing of the manuscript.

References

- Taylor, P.L.; Tabachnik, J. Entropic Forces—Making the Connection between Mechanics and Thermodynamics in an Exactly Soluble Model. Eur J Phys 2013, 34, 729–736. [CrossRef]

- Wissner-Gross, A.D.; Freer, C.E. Causal Entropic Forces. Phys Rev Lett 2013, 110, 168702. [CrossRef]

- Sokolov, I.M. Statistical Mechanics of Entropic Forces: Disassembling a Toy. Eur J Phys 2010, 31, 1353–1367. [CrossRef]

- Gedde, U.W. Polymer Physics; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2001; ISBN 978-0-412-62640-1.

- Rubinstein, M.; Colby, R.H. Polymer Physics; 1st ed.; Oxford University Press, 2003; ISBN 019852059X.

- Graessley, W.W. Polymeric Liquids & Networks; Garland Science, 2003; ISBN 9780203506127.

- Kartsovnik, V.I.; Volchenkov, D. Elastic Entropic Forces in Polymer Deformation. Entropy 2022, 24, 1260. [CrossRef]

- Tskhovrebova, L.; Trinick, J.; Sleep, J.A.; Simmons, R.M. Elasticity and Unfolding of Single Molecules of the Giant Muscle Protein Titin. Nature 1997, 387, 308–312. [CrossRef]

- Braun, M.; Lansky, Z.; Hilitski, F.; Dogic, Z.; Diez, S. Entropic Forces Drive Contraction of Cytoskeletal Networks. BioEssays 2016, 38, 474–481. [CrossRef]

- Verlinde, E. On the Origin of Gravity and the Laws of Newton. Journal of High Energy Physics 2011, 2011, 29. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T. Coulomb Force as an Entropic Force. Physical Review D 2010, 81, 104045. [CrossRef]

- Bormashenko, E. Magnetic Entropic Forces Emerging in the System of Elementary Magnets Exposed to the Magnetic Field. Entropy 2022, 24, 299. [CrossRef]

- Treloar, L. R. G. The Physics of Rubber Elasticity, 3rd ed.; Clarendon Press: Oxford, 1975.

- Paul, J. Thermoelastic characterization of carbon nanotube reinforced PDMS elastomer, J. Polym. Eng. 2021, 41 (2), 87-9415.

- Park, H.; Park, S.; Park, J. M.; Sung, B. J. Entropic contribution to the nonlinear mechanical properties of thermoplastic elastomers, Macromolecules 2025, 58 (4), 1993–2004.

- Arruda, E.M.; Boyce, M.C. A three-dimensional constitutive model for the large stretch behavior of rubber elastic materials, J. Mech. Phys. Solids, 1993, 41, 389–412.

- Buehler, M. J.; Wong, S. Y. Entropic elasticity controls nanomechanics of single tropocollagen molecules, Biophysical J. 2007, 93 (1), 37-43.

- Ito, K. Novel entropic elasticity of polymeric materials: why is slide-ring gel so soft? Polym. J. 2012, 44, 38–41.

- Wendt, D.; Bozin, E.; Neuefeind, J.; Page, K.; Ku, W.; Wang, L.; Fultz, B.; Tkachenko, A. V. Zaliznyak, I.A. Entropic elasticity and negative thermal expansion in a simple cubic crystal, Science Adv. 2019; 5, eaay2748.

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Mao, Y.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Yang, Z.; Chan, C.T.; Sheng, P. Locally Resonant Sonic Materials. Science (1979) 2000, 289, 1734–1736. [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.T.; Li, J.; Fung, K.H. On Extending the Concept of Double Negativity to Acoustic Waves. Journal of Zhejiang University-SCIENCE A 2006, 7, 24–28. [CrossRef]

- Milton, G.W.; Willis, J.R. On Modifications of Newton’s Second Law and Linear Continuum Elastodynamics. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2007, 463, 855–880. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.N.; Hu, G.K.; Huang, G.L.; Sun, C.T. An Elastic Metamaterial with Simultaneously Negative Mass Density and Bulk Modulus. Appl Phys Lett 2011, 98. [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Ma, G.; Yang, Z.; Sheng, P. Coupled Membranes with Doubly Negative Mass Density and Bulk Modulus. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 110, 134301. [CrossRef]

- Lončar, J.; Igrec, B.; Babić, D. Negative-Inertia Converters: Devices Manifesting Negative Mass and Negative Moment of Inertia. Symmetry 2022, 14, 529. [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, R.; Nosonovsky, M. Vibro-Levitation and Inverted Pendulum: Parametric Resonance in Vibrating Droplets and Soft Materials. Soft Matter 2014, 10, 4633–4639. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.S.; Nosonovsky, M. Method of Separation of Vibrational Motions for Applications Involving Wetting, Superhydrophobicity, and Microparticle Extraction. Phys Rev Fluids 2020, 5, 054201. [CrossRef]

- Bormashenko, E. Bioinspired Materials and Metamaterials; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2025; ISBN 9781003178477.

- Huang, H.H.; Sun, C.T.; Huang, G.L. On the Negative Effective Mass Density in Acoustic Metamaterials. Int J Eng Sci 2009, 47, 610–617. [CrossRef]

- Bormashenko, E.; Legchenkova, I. Negative Effective Mass in Plasmonic Systems. Materials 2020, 13, 1890. [CrossRef]

- Bormashenko, E.; Legchenkova, I.; Frenkel, M. Negative Effective Mass in Plasmonic Systems II: Elucidating the Optical and Acoustical Branches of Vibrations and the Possibility of Anti-Resonance Propagation. Materials 2020, 13, 3512. [CrossRef]

- Kshetrimayum, R.S. A Brief Intro to Metamaterials. IEEE Potentials 2005, 23, 44–46. [CrossRef]

- Karami, B.; Ghayesh, M.H. Dynamics of Graphene Origami-Enabled Auxetic Metamaterial Beams via Various Shear Deformation Theories. Int J Eng Sci 2024, 203, 104123. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qin, Y.; Luo, K.; Tian, Q.; Hu, H. Dynamic Modeling and Simulation of Hard-Magnetic Soft Beams Interacting with Environment via High-Order Finite Elements of ANCF. Int J Eng Sci 2024, 202, 104102. [CrossRef]

- Sang, S.; Mhannawee, A.; Wang, Z. A Design of Active Elastic Metamaterials with Negative Mass Density and Tunable Bulk Modulus. Acta Mech 2019, 230, 1003–1008. [CrossRef]

- Brunet, T.; Merlin, A.; Mascaro, B.; Zimny, K.; Leng, J.; Poncelet, O.; Aristégui, C.; Mondain-Monval, O. Soft 3D Acoustic Metamaterial with Negative Index. Nat Mater 2015, 14, 384–388. [CrossRef]

- Feynman, R. The Feynman Lectures on Physics; Addison Wesley Publishinng Co. Reading: Massachusetts, 1964.

- Ogata, K. System Dynamics; 4th ed.; Pearson, 2003.

- Manevitch, L.I.; Gendelman, O. V. Tractable Models of Solid Mechanics; Foundations of Engineering Mechanics; 1st ed.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; ISBN 978-3-642-15371-6.

- Sandberg, R.; Svendsen, W.; Mølhave, K.; Boisen, A. Temperature and Pressure Dependence of Resonance in Multi-Layer Microcantilevers. Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering 2005, 15, 1454–1458. [CrossRef]

- Fantini, C.; Jorio, A.; Souza, M.; Strano, M.S.; Dresselhaus, M.S.; Pimenta, M.A. Optical Transition Energies for Carbon Nanotubes from Resonant Raman Spectroscopy: Environment and Temperature Effects. Phys Rev Lett 2004, 93, 147406. [CrossRef]

- Livneh, T. Resonant Raman Scattering in UO2 Revisited. Phys Rev B 2022, 105, 045115. [CrossRef]

- Shiryaev, A.A.; Ekimov, E.A.; Prokof’ev, V.Y. Temperature Dependence of the Fano Resonance in Nanodiamonds Synthesized at High Static Pressures. Jetp. Lett. 2022, 115, 651–656.

- Yao, S.; Zhou, X.; Hu, G. Experimental Study on Negative Effective Mass in a 1D Mass–Spring System. New J Phys 2008, 10, 043020. [CrossRef]

- Landau, L.; Lifshitz, E. Mechanics: Volume 1 (Course of Theoretical Physics S); Butterworth-Heinemann, 2000.

- Rico-Pasto, M.; Ritort, F. Temperature-dependent elastic properties of DNA, Biophysical Reports, 2022, 2 (3), 100067.

- Fok, L.; Zhang, X. Negative Acoustic Index Metamaterial. Phys Rev B 2011, 83, 214304. [CrossRef]

- Cavassilas, N.; Autran, J.-L.; Aniel, F.; Fishman, G. Energy and temperature dependence of electron effective masses in silicon, J. Appl. Phys. 2002, 92, 1431–1433.

- Lai, Y.; Wu, Y.,;Sheng, P.; Zhang, Z-Q. Hybrid elastic solids. Nature Mater. 2011, 10, 620–624. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Sh.; Zhou, X.; Hu, G. Investigation of the negative-mass behaviors occurring below a cut-off frequency, New J. Phys. 2010, 12, 103025. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The core-shell unit giving rise to the effect of the “negative effective mass”. The core mass m is connected with two polymer elastic Hookean springs k to the shell . The core-shell system is exposed to the harmonic external force .

Figure 1.

The core-shell unit giving rise to the effect of the “negative effective mass”. The core mass m is connected with two polymer elastic Hookean springs k to the shell . The core-shell system is exposed to the harmonic external force .

Figure 2.

Temperature dependence of the effective mass is depicted. Dashed lines demonstrate the asymptotic behavior of

Figure 2.

Temperature dependence of the effective mass is depicted. Dashed lines demonstrate the asymptotic behavior of

Figure 3.

Chain of the core-shell units giving rise to the effect of temperature dependent negative density [

22]. The single lattice constant of the 1D chain, defined as the distance between the core-shell units is

a, the mass of the core is

, the mass of the shell is

and

are entropic strings.

Figure 3.

Chain of the core-shell units giving rise to the effect of temperature dependent negative density [

22]. The single lattice constant of the 1D chain, defined as the distance between the core-shell units is

a, the mass of the core is

, the mass of the shell is

and

are entropic strings.

Figure 4.

The temperature dependent effective density of the chain, shown in

Figure 3 is depicted. The blue curve depicts the dependence

for the dimensionless parameters:

The resonance occurs when

Set of brown curves depicts the temperature dependencies of the effective density calculated for the different values of

Blue dashed line demonstrates the asymptotic behavior of

Red dashed line is

Black arrow depicts increase in

.

Figure 4.

The temperature dependent effective density of the chain, shown in

Figure 3 is depicted. The blue curve depicts the dependence

for the dimensionless parameters:

The resonance occurs when

Set of brown curves depicts the temperature dependencies of the effective density calculated for the different values of

Blue dashed line demonstrates the asymptotic behavior of

Red dashed line is

Black arrow depicts increase in

.

Figure 5.

The plots demonstrate change in the resonance curves when parameters and are varied. Brown curves are built for the fixed and demonstrate change of with for . The blue curve demonstrates The magenta curves illustrate variation in and depict Brown arrow depicts increase in ; magenta arrow illustrates increase in

Figure 5.

The plots demonstrate change in the resonance curves when parameters and are varied. Brown curves are built for the fixed and demonstrate change of with for . The blue curve demonstrates The magenta curves illustrate variation in and depict Brown arrow depicts increase in ; magenta arrow illustrates increase in

Figure 6.

The dependence is depicted for various temperatures T. The curves are depicted.

Figure 6.

The dependence is depicted for various temperatures T. The curves are depicted.

Figure 7.

Curves are depicted. Black arow depicts the increase in .

Figure 7.

Curves are depicted. Black arow depicts the increase in .

Figure 8.

Here are curves . The asymptotic behavior corresponds to . Black arrow depicts the increase in

Figure 8.

Here are curves . The asymptotic behavior corresponds to . Black arrow depicts the increase in

Figure 9.

The solution of dispersion equation (Eq. 19) is depicted: acoustic (blue curves) and optical branches (from brown () to orange () curve), calculated for . The arrow indicates the direction of increase in parameter value. It is seen that dependence of acoustic mode on for is negligible.

Figure 9.

The solution of dispersion equation (Eq. 19) is depicted: acoustic (blue curves) and optical branches (from brown () to orange () curve), calculated for . The arrow indicates the direction of increase in parameter value. It is seen that dependence of acoustic mode on for is negligible.

Figure 12.

The solution of dispersion equation (Eq. 18) for is depicted acoustic (blue curves) and optical branches (from brown () to orange () curve), calculated for . The arrow indicates the direction of increase in parameter value.

Figure 12.

The solution of dispersion equation (Eq. 18) for is depicted acoustic (blue curves) and optical branches (from brown () to orange () curve), calculated for . The arrow indicates the direction of increase in parameter value.

Figure 13.

The solution of dispersion equation (Eq. 18) for is depicted. Here temperature T changes from 50 (orange “optical” branch) to 300 (light blue “optical” curve) with a step of 50. Acoustic branch (blue curves) is barely dependent on temperature.

Figure 13.

The solution of dispersion equation (Eq. 18) for is depicted. Here temperature T changes from 50 (orange “optical” branch) to 300 (light blue “optical” curve) with a step of 50. Acoustic branch (blue curves) is barely dependent on temperature.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).