Submitted:

11 June 2025

Posted:

12 June 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

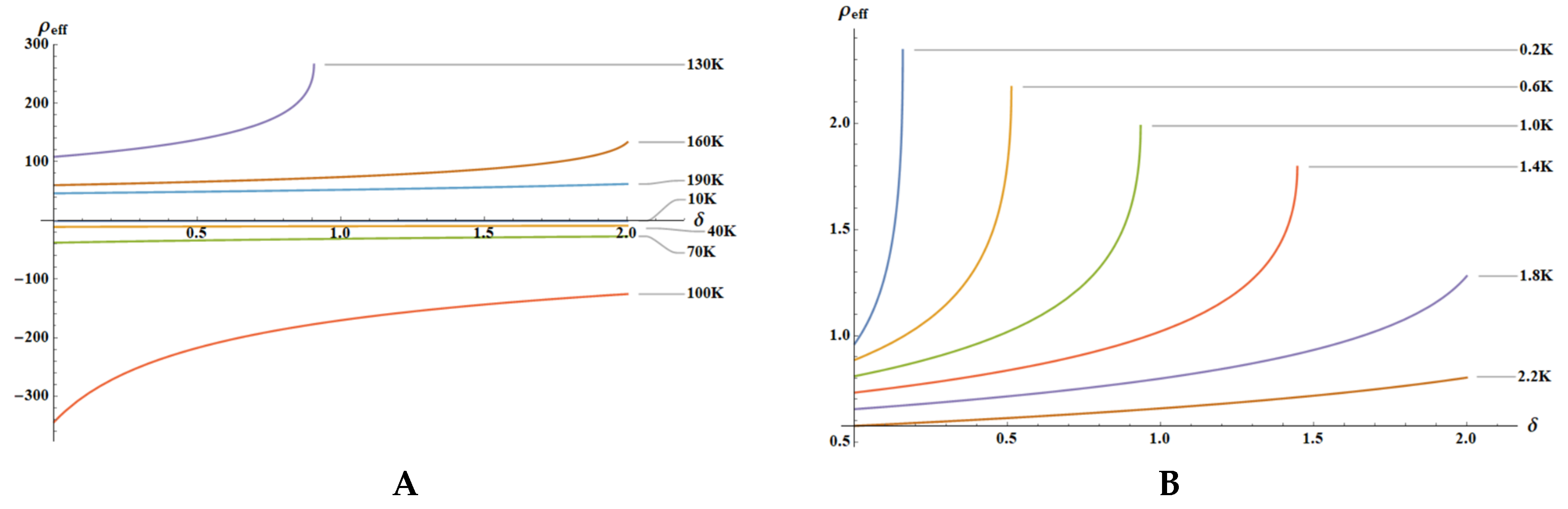

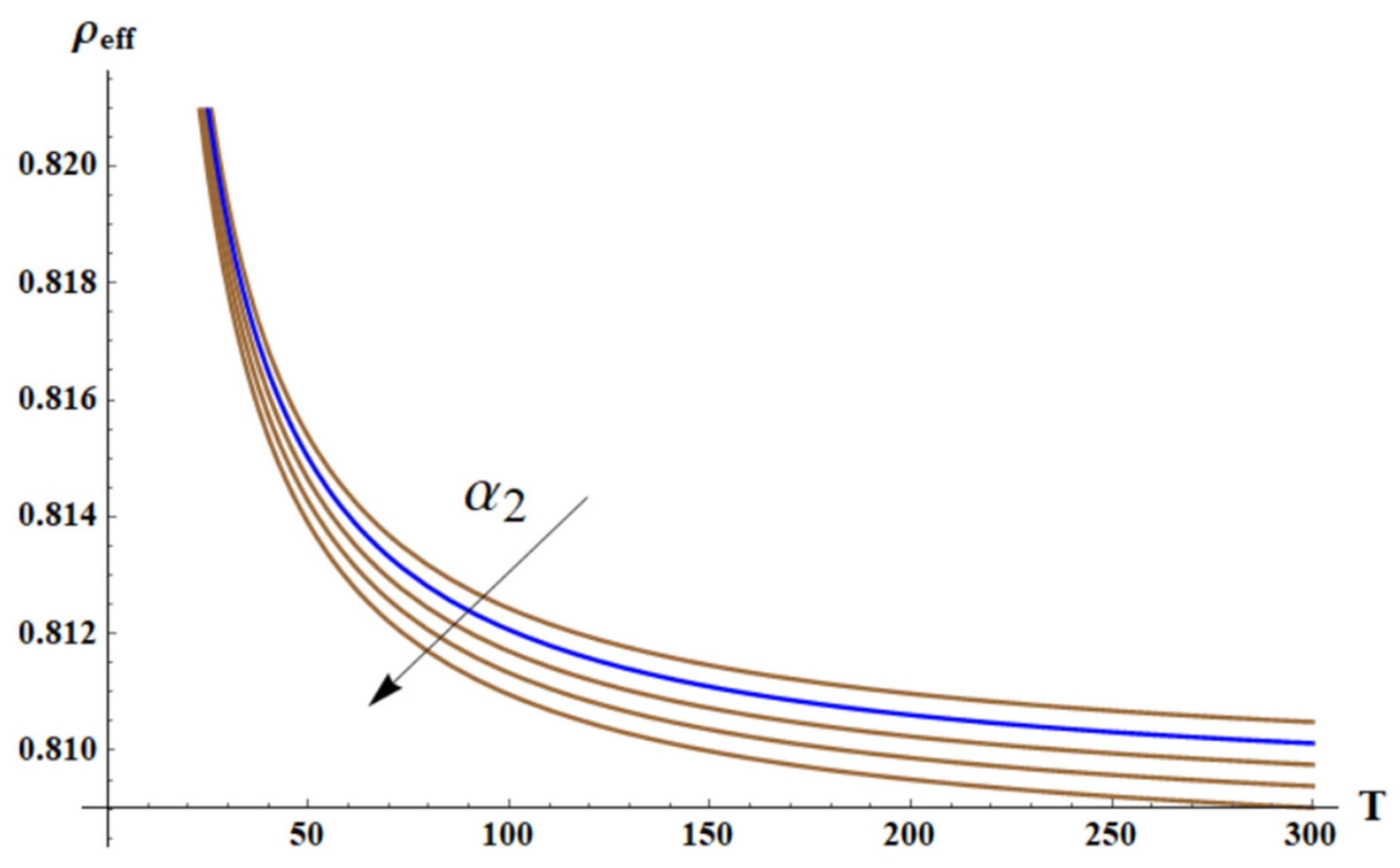

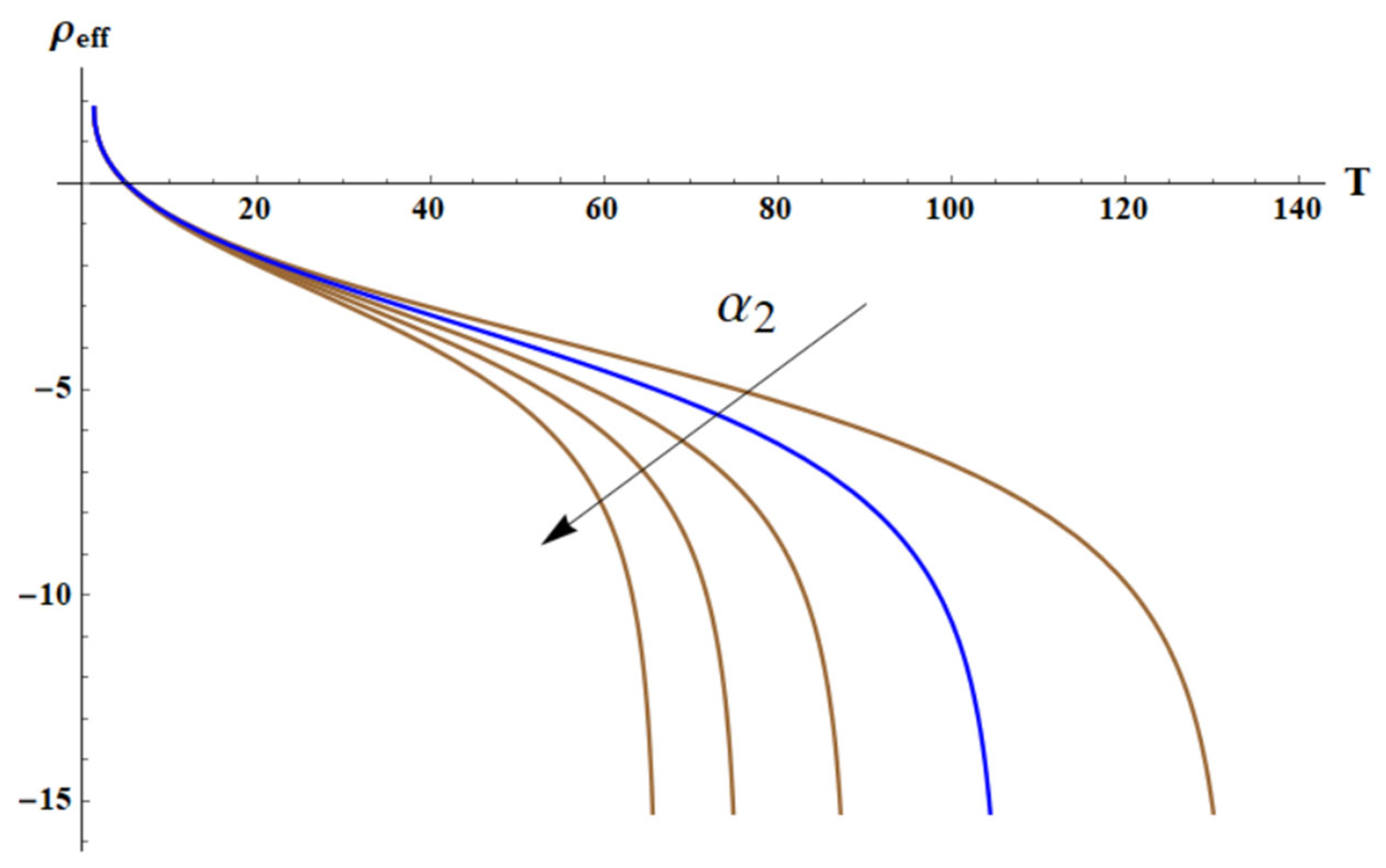

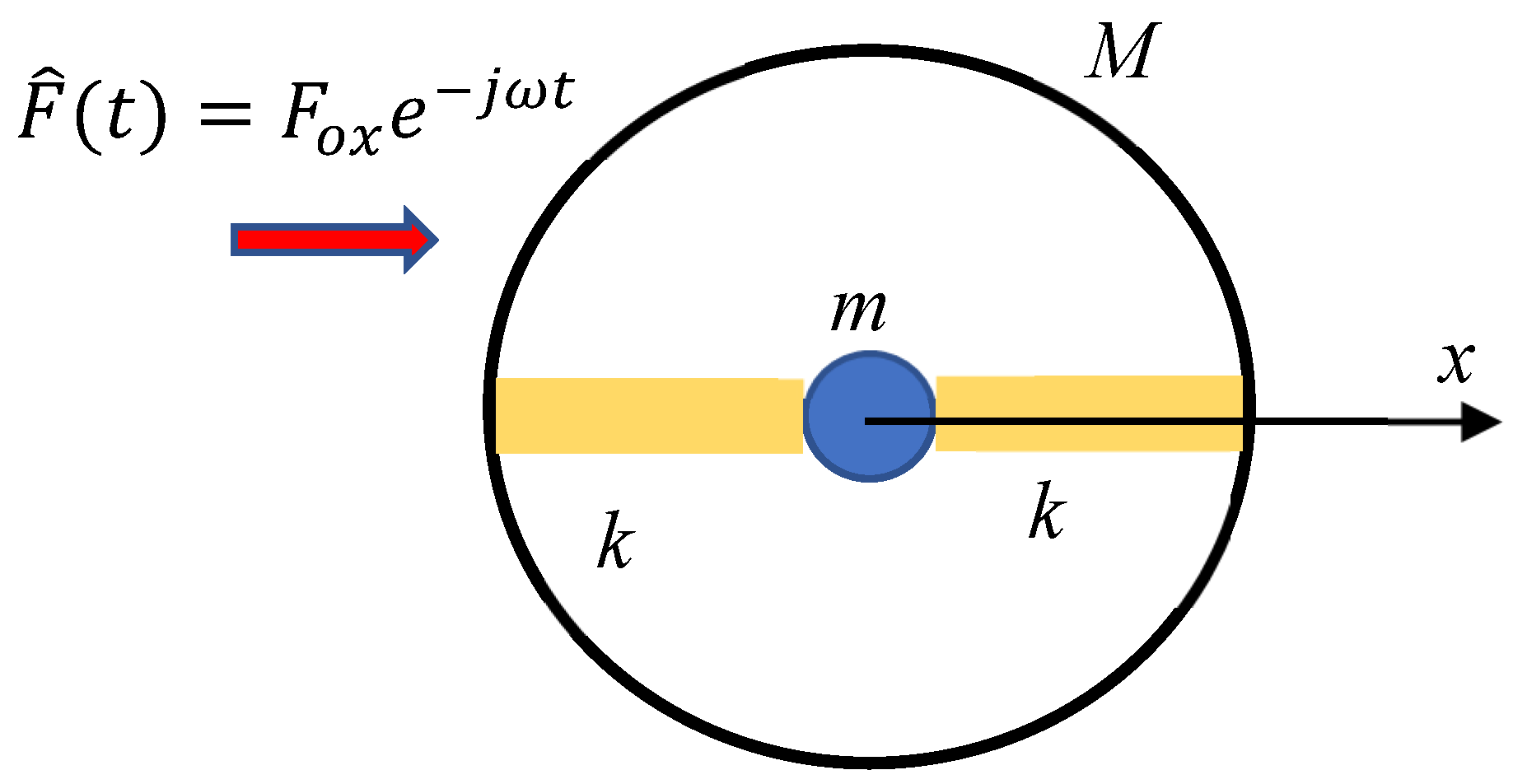

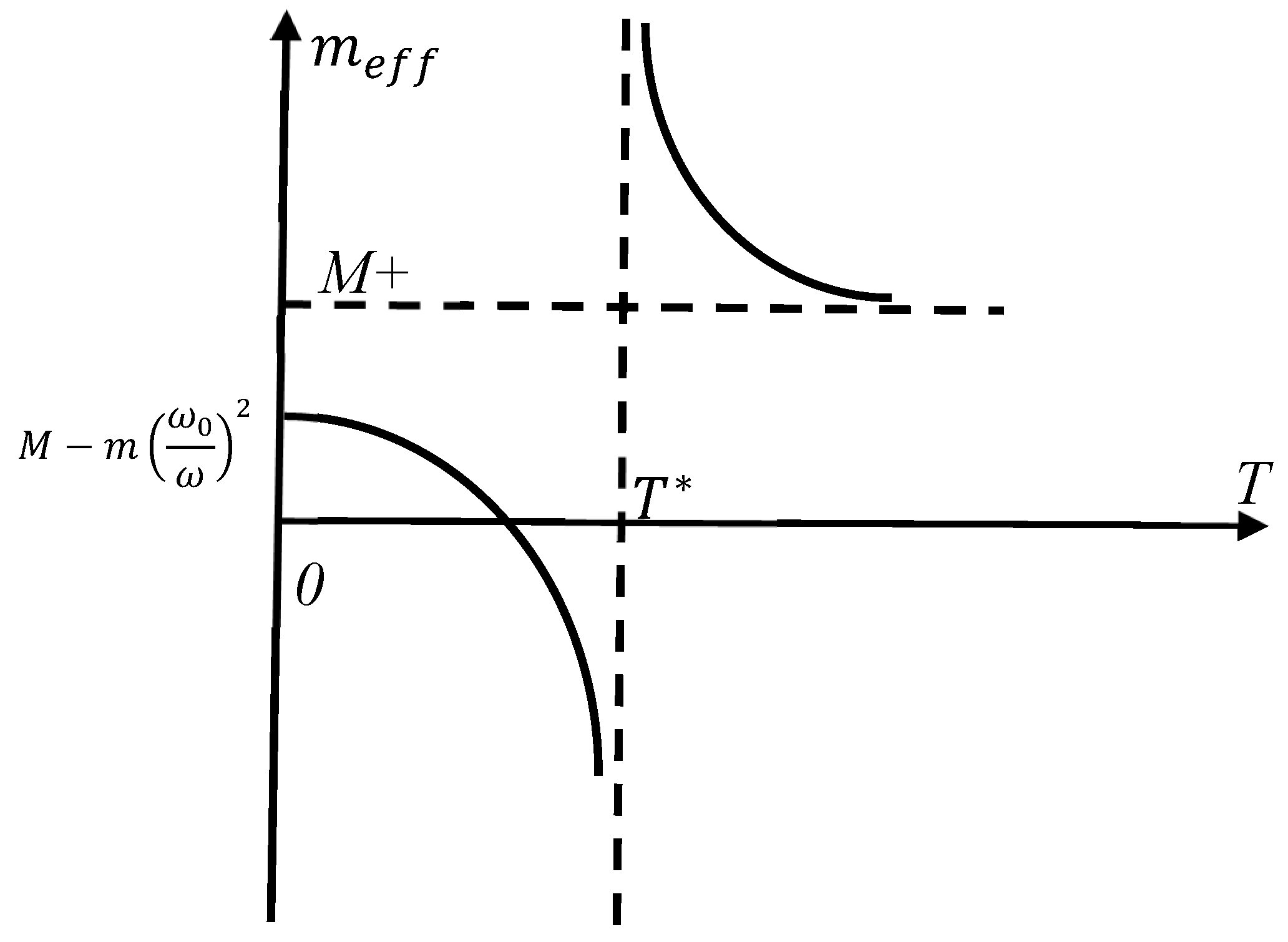

3.1. Negative Mass in the Core-Shell System Driven by Entropic Elastic Force

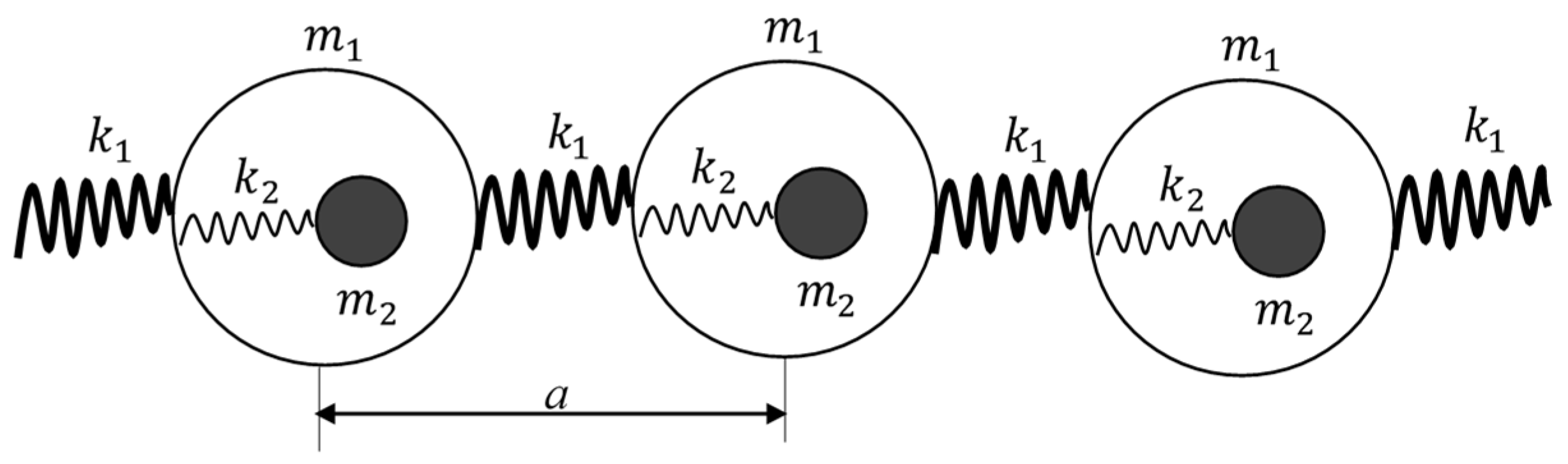

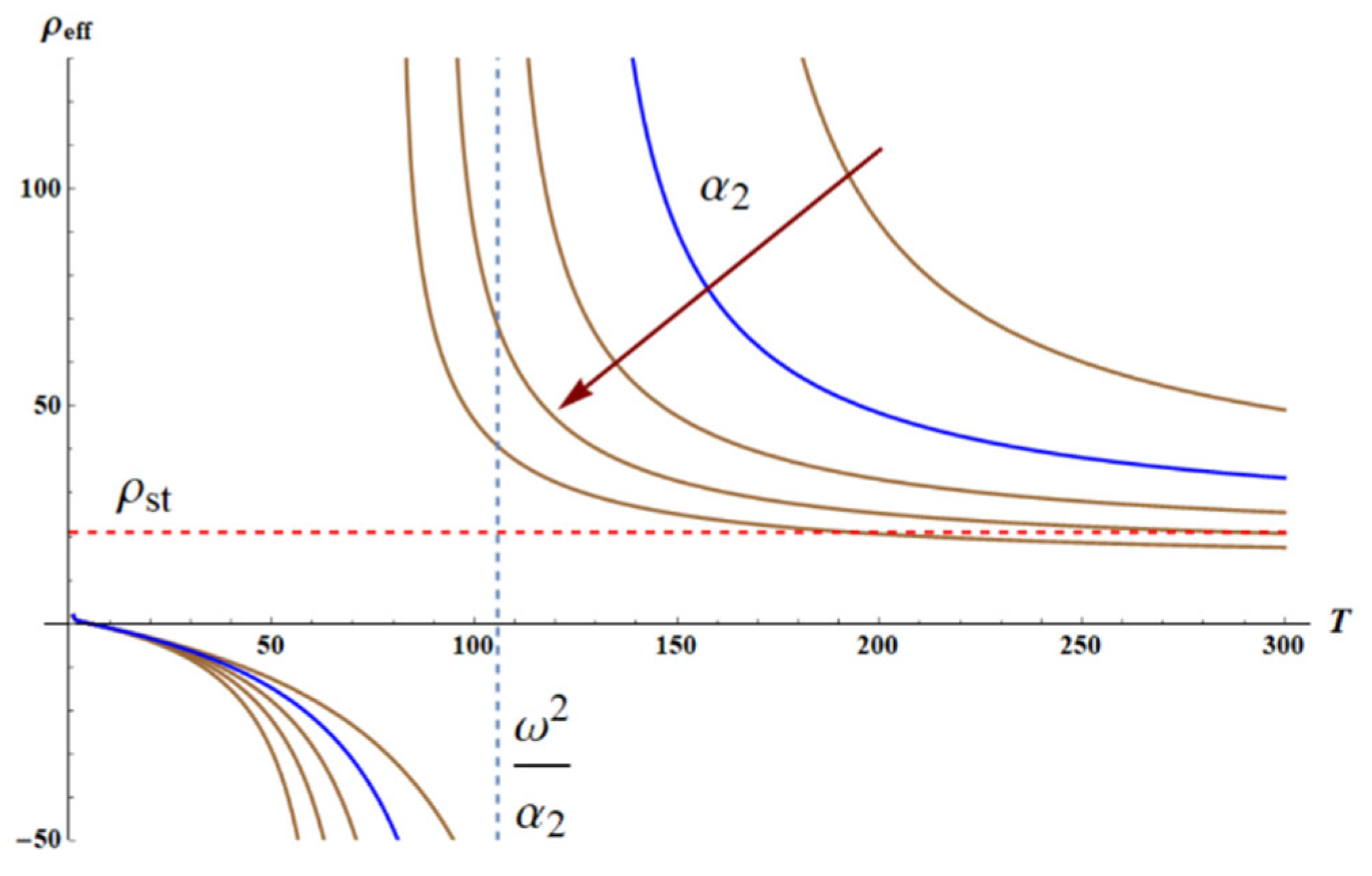

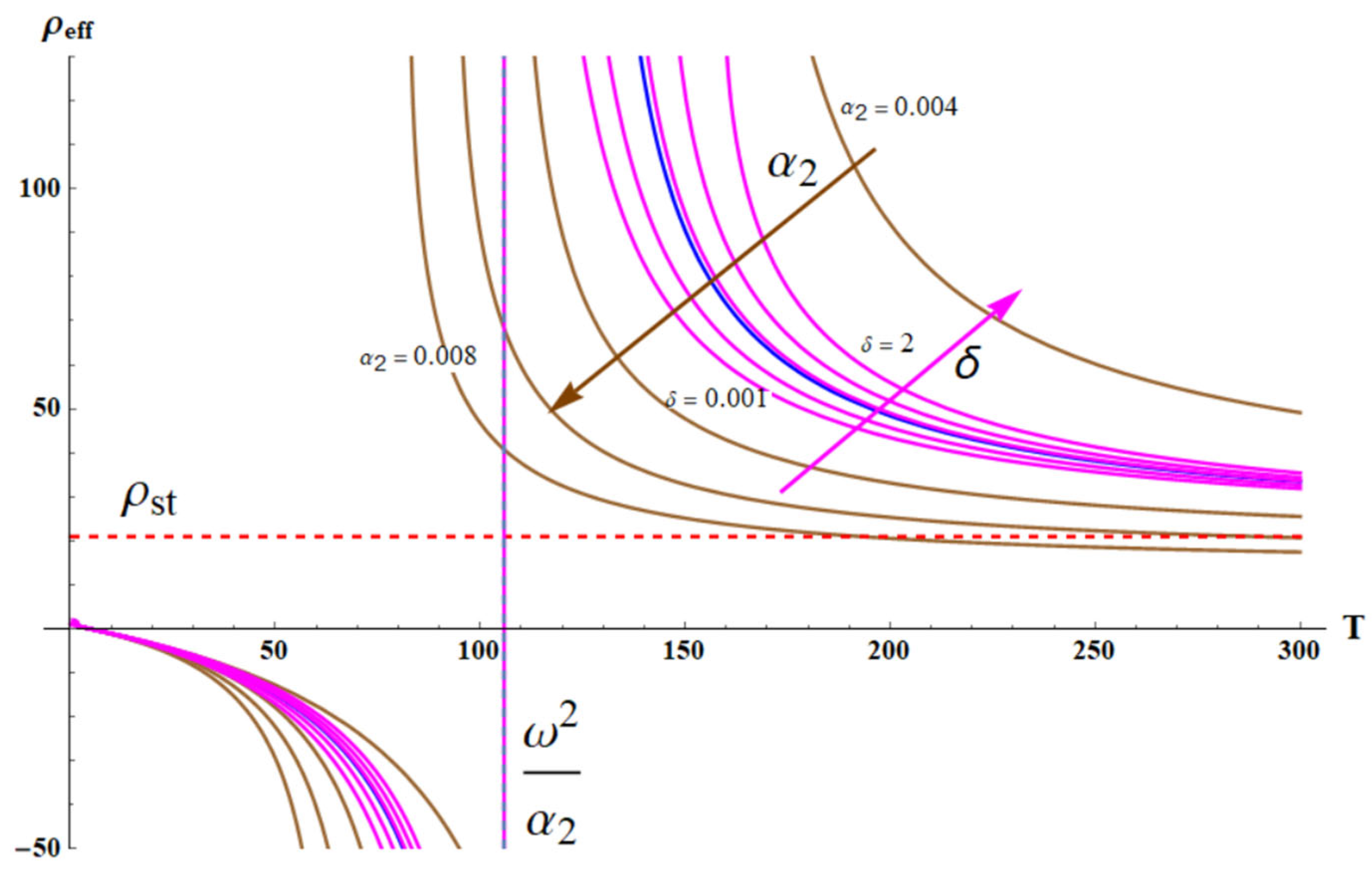

3.2. Negative Density of the Chain of Core-Shell Systems Driven by Elastic Forces

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

References

- Taylor, P.L.; Tabachnik, J. Entropic Forces—Making the Connection between Mechanics and Thermodynamics in an Exactly Soluble Model. Eur J Phys 2013, 34, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissner-Gross, A.D.; Freer, C.E. Causal Entropic Forces. Phys Rev Lett 2013, 110, 168702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokolov, I.M. Statistical Mechanics of Entropic Forces: Disassembling a Toy. Eur J Phys 2010, 31, 1353–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedde, U.W. Polymer Physics; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2001; ISBN 978-0-412-62640-1. [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein, M.; Colby, R.H. Polymer Physics, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press, 2003; ISBN 019852059X. [Google Scholar]

- Graessley, W.W. Polymeric Liquids & Networks; Garland Science, 2003; ISBN 9780203506127.

- Kartsovnik, V.I.; Volchenkov, D. Elastic Entropic Forces in Polymer Deformation. Entropy 2022, 24, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tskhovrebova, L.; Trinick, J.; Sleep, J.A.; Simmons, R.M. Elasticity and Unfolding of Single Molecules of the Giant Muscle Protein Titin. Nature 1997, 387, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, M.; Lansky, Z.; Hilitski, F.; Dogic, Z.; Diez, S. Entropic Forces Drive Contraction of Cytoskeletal Networks. BioEssays 2016, 38, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlinde, E. On the Origin of Gravity and the Laws of Newton. Journal of High Energy Physics 2011, 2011, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T. Coulomb Force as an Entropic Force. Physical Review D 2010, 81, 104045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormashenko, E. Magnetic Entropic Forces Emerging in the System of Elementary Magnets Exposed to the Magnetic Field. Entropy 2022, 24, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Mao, Y.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Yang, Z.; Chan, C.T.; Sheng, P. Locally Resonant Sonic Materials. Science (1979) 2000, 289, 1734–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.T.; Li, J.; Fung, K.H. On Extending the Concept of Double Negativity to Acoustic Waves. Journal of Zhejiang University-SCIENCE A 2006, 7, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, G.W.; Willis, J.R. On Modifications of Newton’s Second Law and Linear Continuum Elastodynamics. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2007, 463, 855–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.N.; Hu, G.K.; Huang, G.L.; Sun, C.T. An Elastic Metamaterial with Simultaneously Negative Mass Density and Bulk Modulus. Appl Phys Lett 2011, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Ma, G.; Yang, Z.; Sheng, P. Coupled Membranes with Doubly Negative Mass Density and Bulk Modulus. Phys Rev Lett 2013, 110, 134301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lončar, J.; Igrec, B.; Babić, D. Negative-Inertia Converters: Devices Manifesting Negative Mass and Negative Moment of Inertia. Symmetry (Basel) 2022, 14, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, R.; Nosonovsky, M. Vibro-Levitation and Inverted Pendulum: Parametric Resonance in Vibrating Droplets and Soft Materials. Soft Matter 2014, 10, 4633–4639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.S.; Nosonovsky, M. Method of Separation of Vibrational Motions for Applications Involving Wetting, Superhydrophobicity, and Microparticle Extraction. Phys Rev Fluids 2020, 5, 054201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormashenko, E. Bioinspired Materials and Metamaterials; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2025; ISBN 9781003178477. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.H.; Sun, C.T.; Huang, G.L. On the Negative Effective Mass Density in Acoustic Metamaterials. Int J Eng Sci 2009, 47, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormashenko, E.; Legchenkova, I. Negative Effective Mass in Plasmonic Systems. Materials 2020, 13, 1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormashenko, E.; Legchenkova, I.; Frenkel, M. Negative Effective Mass in Plasmonic Systems II: Elucidating the Optical and Acoustical Branches of Vibrations and the Possibility of Anti-Resonance Propagation. Materials 2020, 13, 3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshetrimayum, R.S. A Brief Intro to Metamaterials. IEEE Potentials 2005, 23, 44–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, B.; Ghayesh, M.H. Dynamics of Graphene Origami-Enabled Auxetic Metamaterial Beams via Various Shear Deformation Theories. Int J Eng Sci 2024, 203, 104123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qin, Y.; Luo, K.; Tian, Q.; Hu, H. Dynamic Modeling and Simulation of Hard-Magnetic Soft Beams Interacting with Environment via High-Order Finite Elements of ANCF. Int J Eng Sci 2024, 202, 104102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, S.; Mhannawee, A.; Wang, Z. A Design of Active Elastic Metamaterials with Negative Mass Density and Tunable Bulk Modulus. Acta Mech 2019, 230, 1003–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet, T.; Merlin, A.; Mascaro, B.; Zimny, K.; Leng, J.; Poncelet, O.; Aristégui, C.; Mondain-Monval, O. Soft 3D Acoustic Metamaterial with Negative Index. Nat Mater 2015, 14, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feynman, R. The Feynman Lectures on Physics; Addison Wesley Publishinng Co. Reading: Massachusetts, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Ogata, K. System Dynamics, 4th ed. Pearson, 2003.

- Manevitch, L.I.; Gendelman, O. V. Tractable Models of Solid Mechanics; Foundations of Engineering Mechanics, 1st ed.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; ISBN 978-3-642-15371-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg, R.; Svendsen, W.; Mølhave, K.; Boisen, A. Temperature and Pressure Dependence of Resonance in Multi-Layer Microcantilevers. Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering 2005, 15, 1454–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantini, C.; Jorio, A.; Souza, M.; Strano, M.S.; Dresselhaus, M.S.; Pimenta, M.A. Optical Transition Energies for Carbon Nanotubes from Resonant Raman Spectroscopy: Environment and Temperature Effects. Phys Rev Lett 2004, 93, 147406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livneh, T. Resonant Raman Scattering in UO2 Revisited. Phys Rev B 2022, 105, 045115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiryaev, A.A.; Ekimov, E.A.; Prokof’ev, V.Y. Temperature Dependence of the Fano Resonance in Nanodiamonds Synthesized at High Static Pressures. Jetp. Lett. 2022, 115, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Zhou, X.; Hu, G. Experimental Study on Negative Effective Mass in a 1D Mass–Spring System. New J Phys 2008, 10, 043020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, L.; Lifshitz, E. Mechanics: Volume 1 (Course of Theoretical Physics S); Butterworth-Heinemann, 2000.

- Rico-Pasto, M.; Ritort, F. Temperature-dependent elastic properties of DNA, Biophysical Reports, 2022, 2 (3), 100067.

- Fok, L.; Zhang, X. Negative Acoustic Index Metamaterial. Phys Rev B 2011, 83, 214304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavassilas, N.; Autran, J.-L.; Aniel, F.; Fishman, G. Energy and temperature dependence of electron effective masses in silicon, J. Appl. Phys. 2002, 92, 1431–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).