Submitted:

14 May 2025

Posted:

14 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Food’s Sample Collection

1.2. Hand’s Sample Collection

1.3. Escherichia coli Isolation

1.4. DNA Extraction and 16S PCR

1.5. Determination of stx1, stx2, and Eae Virulence Genes in Escherichia coli Strains

1.6. Antibiogram

| Antibiotics | Classes |

|---|---|

| Ampicillin (AMP) 10 µg | Beta lactamine Penicillin group A |

| Amoxicillin-clavulamic acid (AMC) 20/10 µg | Beta lactamine + Clavulamic acid, Penicillin group A |

| Aztreonam (ATM) 30 µg | Beta lactamine, Monobactam |

| Cephalotin (CF) 30 µg | Beta lactamine, Cephalosporin 1ère generation |

| Cefoxitin (FOX) 30 µg | Beta lactamine, Cephalosporin 2ème generation |

| Cefotaxime (CTX) 30 µg | Beta lactamine, Cephalosporin 3ème generation |

| Chloramphenicol (CHL) 30 µg | Phenocolate |

| Ciprofloxacin (CIP) 5 µg | Quinolone |

| Gentamicin (GMN) 10 µg | Aminoside |

| Tetracycline (TET) 30 µg | Tetracycline |

| Antibiotics | Reference inhibition diameters in mm | |

|---|---|---|

| S ≥ | R ˂ | |

| Aztreonam | 26 | 21 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 25 | 22 |

| Gentamicin | 17 | 17 |

| Tetracycline | - | - |

| Chloramphenicol | 17 | 17 |

| Cefotaxime | 20 | 17 |

| Cefoxitin | 19 | 19 |

| Amoxicillin | 19 | 19 |

| Amplicillin | 19 | 19 |

1.7. Statistical Analysis

2. Results

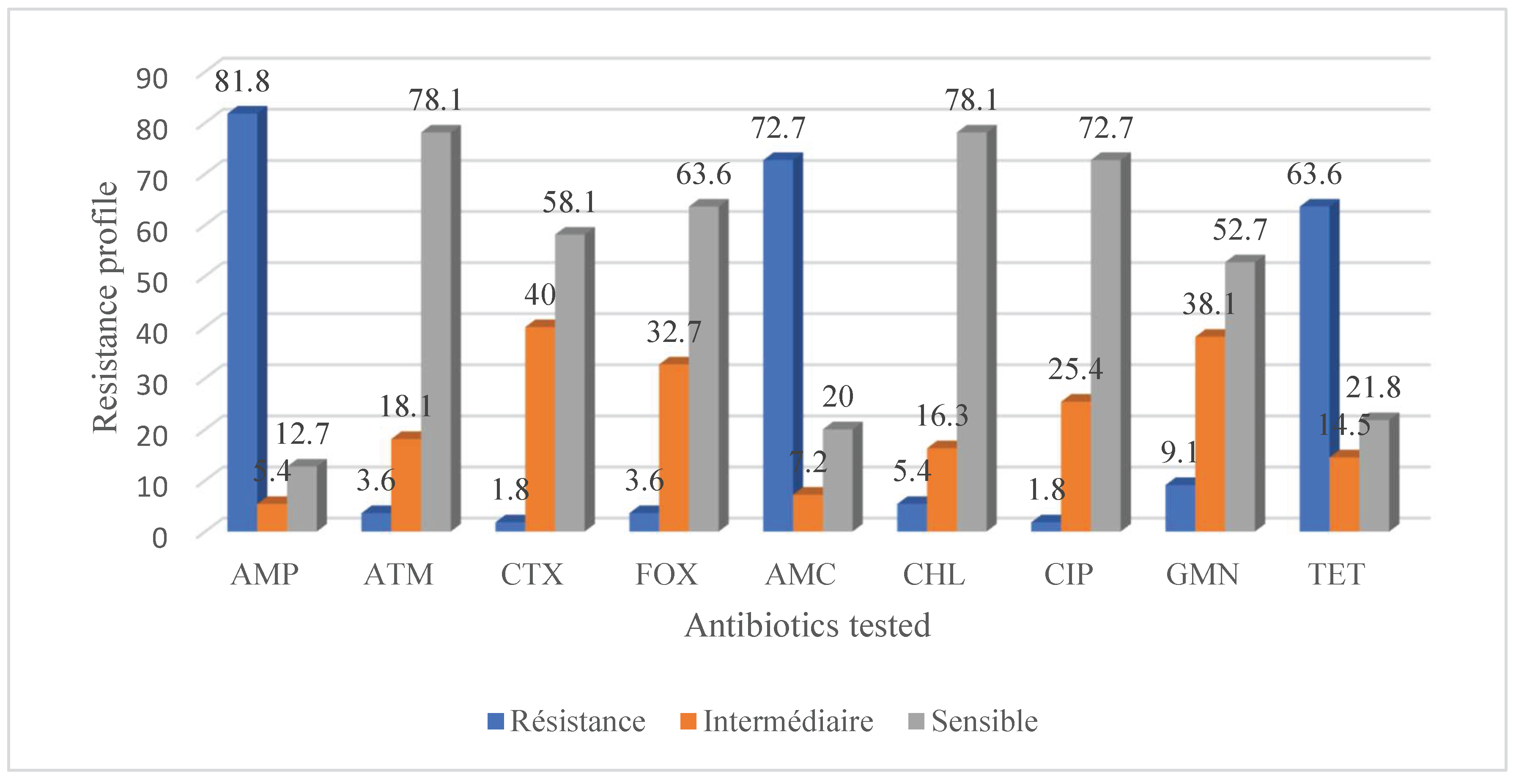

2.1. Antibiotic Resistance and Virulence of Escherichia coli Strains Isolated from Food of Animal Origin and Hands

2.2. Multidrug Resistance Profile of Escherichia coli Strains Isolated from Food of Animal Origin and Surfaces to Antibiotics

2.3. Virulence Gene Profile of Escherichia coli Strains Isolated from Foods of Animal Origin and Hands

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Salamandane, A.; Alves, S.; Chambel, L.; Malfeito-Ferreira, M.; Brito, L. Characterization of Escherichia Coli from Water and Food Sold on the Streets of Maputo: Molecular Typing, Virulence Genes, and Antibiotic Resistance. Applied Microbiology 2022, 2 (1), 133–147.

- Soriyi, I.; Agbogli, H. K.; Dongdem, J. T. A Pilot Microbial Assessment of Beef Sold in the Ashaiman Market, a Suburb of Accra, Ghana. African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development 2008, 8 (1), 91–103. [CrossRef]

- Bahir, M. A.; Errachidi, I.; Hemlali, M.; Sarhane, B.; Tantane, A.; Mohammed, A.; Belkadi, B.; Filali-Maltouf, A. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices (KAP) Regarding Meat Safety and Sanitation among Carcass Handlers Operating and Assessment of Bacteriological Quality of Meat Contact Surfaces at the Marrakech Slaughterhouse, Morocco. International Journal of Food Science 2022, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Gurmu, E. B.; Gebretinsae, H. Assessment of Bacteriological Quality of Meat Contact Surfaces in Selected Butcher Shops of Mekelle City, Ethiopia. Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health 2013, 2 (2), 61–66. [CrossRef]

- Olasoju, M. I.; Olasoju, T. I.; Adebowale, O. O.; Adetunji, V. O. Knowledge and Practice of Cattle Handlers on Antibiotic Residues in Meat and Milk in Kwara State, Northcentral Nigeria. Plos one 2021, 16 (10), e0257249. [CrossRef]

- Tuglo, L. S.; Agordoh, P. D.; Tekpor, D.; Pan, Z.; Agbanyo, G.; Chu, M. Food Safety Knowledge, Attitude, and Hygiene Practices of Street-Cooked Food Handlers in North Dayi District, Ghana. Environmental health and preventive medicine 2021, 26 (1), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Kaper, J. B.; Nataro, J. P.; Mobley, H. L. Pathogenic Escherichia Coli. Nature reviews microbiology 2004, 2 (2), 123–140.

- K Bhardwaj, A.; Vinothkumar, K.; Rajpara, N. Bacterial Quorum Sensing Inhibitors: Attractive Alternatives for Control of Infectious Pathogens Showing Multiple Drug Resistance. Recent patents on anti-infective drug discovery 2013, 8 (1), 68–83.

- Asadi, S.; Nayeri-Fasaei, B.; Zahraei-Salehi, T.; Yahya-Rayat, R.; Shams, N.; Sharifi, A. Antibacterial and Anti-Biofilm Properties of Carvacrol Alone and in Combination with Cefixime against Escherichia Coli. BMC microbiology 2023, 23 (1), 55. [CrossRef]

- Komagbe, G. S.; Sessou, P.; Dossa, F.; Sossa-Minou, P.; Taminiau, B.; Azokpota, P.; Korsak, N.; Daube, G.; Farougou, S. Assessment of the Microbiological Quality of Beverages Sold in Collective Cafes on the Campuses of the University of Abomey-Calavi, Benin Republic. Journal of Food Safety and Hygiene 2019, 5 (2), 99–111. [CrossRef]

- Karama, M.; Mainga, A. O.; Cenci-Goga, B. T.; Malahlela, M.; El-Ashram, S.; Kalake, A. Molecular Profiling and Antimicrobial Resistance of Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia Coli O26, O45, O103, O121, O145 and O157 Isolates from Cattle on Cow-Calf Operations in South Africa. Scientific reports 2019, 9 (1), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Richter, L.; Plessis, E. D.; Duvenage, S.; Korsten, L. High Prevalence of Multidrug Resistant Escherichia Coli Isolated from Fresh Vegetables Sold by Selected Formal and Informal Traders in the Most Densely Populated Province of South Africa. Journal of Food Science 2021, 86 (1), 161–168. [CrossRef]

- Jaja, I. F.; Jaja, C.-J. I.; Chigor, N. V.; Anyanwu, M. U.; Maduabuchi, E. K.; Oguttu, J. W.; Green, E. Antimicrobial Resistance Phenotype of Staphylococcus Aureus and Escherichia Coli Isolates Obtained from Meat in the Formal and Informal Sectors in South Africa. BioMed Research International 2020, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Minda Asfaw, G.; Shimelis, R. Escherichia Coli O15: H7 from Food of Animal Origin in Arsi: Occurrence at Catering Establishments and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Profile. The Scientific World Journal 2021, 2021.

- Ajuwon, B. I.; Babatunde, S. K.; Kolawole, O. M.; Ajiboye, A. E.; Lawal, A. H. Prevalence and Antibiotic Resistance of Escherichia Coli O157: H7 in Beef at a Commercial Slaughterhouse in Moro, Kwara State, Nigeria. Access Microbiology 2021, 3 (11). [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, T. J.; Chen, J.; Walker, C. M.; Gonzales, E.; Cleary, T. G. Rifaximin Does Not Induce Toxin Production or Phage-Mediated Lysis of Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia Coli. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2007, 51 (8), 2837–2841. [CrossRef]

- Beyi, A. F.; Fite, A. T.; Tora, E.; Tafese, A.; Genu, T.; Kaba, T.; Beyene, T. J.; Beyene, T.; Korsa, M. G.; Tadesse, F. Prevalence and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Escherichia Coli O157 in Beef at Butcher Shops and Restaurants in Central Ethiopia. BMC microbiology 2017, 17, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Abdissa, R.; Haile, W.; Fite, A. T.; Beyi, A. F.; Agga, G. E.; Edao, B. M.; Tadesse, F.; Korsa, M. G.; Beyene, T.; Beyene, T. J. Prevalence of Escherichia Coli O157: H7 in Beef Cattle at Slaughter and Beef Carcasses at Retail Shops in Ethiopia. BMC infectious diseases 2017, 17 (1), 1–6. [CrossRef]

- El-Baz, A. H.; El-Sherbini, M.; Abdelkhalek, A.; Al-Ashmawy, M. A. Prevalence and Molecular Characterization of Salmonella Serovars in Milk and Cheese in Mansoura City, Egypt. Journal of Advanced Veterinary & Animal Research 2017, 4 (1).

- Sallam, K. I.; Mohammed, M. A.; Hassan, M. A.; Tamura, T. Prevalence, Molecular Identification and Antimicrobial Resistance Profile of Salmonella Serovars Isolated from Retail Beef Products in Mansoura, Egypt. Food control 2014, 38, 209–214. [CrossRef]

- Iwu, C. D.; du Plessis, E.; Korsten, L.; Okoh, A. I. Prevalence of E. Coli O157: H7 Strains in Irrigation Water and Agricultural Soil in Two District Municipalities in South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Studies 2021, 78 (3), 474–483.

- Lahou, E.; Uyttendaele, M. Evaluation of Three Swabbing Devices for Detection of Listeria Monocytogenes on Different Types of Food Contact Surfaces. International journal of environmental research and public health 2014, 11 (1), 804–814. [CrossRef]

- Dougnon, V.; Houssou, V. M. C.; Anago, E.; Nanoukon, C.; Mohammed, J.; Agbankpe, J.; Koudokpon, H.; Bouraima, B.; Deguenon, E.; Fabiyi, K. Assessment of the Presence of Resistance Genes Detected from the Environment and Selected Food Products in Benin. Journal of Environmental and Public Health 2021, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Turnidge, J.; Abbott, I. J. EUCAST Breakpoint Categories and the Revised “I”: A Stewardship Opportunity for “I” Mproving Outcomes. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2022, 28 (4), 475–476.

- Sessou, P.; Klotoe, J. R.; Dougnon, V.; Osseni, S. D.; Hounkpe, E.; Azokpota, P.; Issaka, Y.; Loko, F.; Sohounhloue, D.; Farougou, S. Safety Evaluation of Traditional Cheese Wagashi Treated with Essential Oils in Wistar Rats: A Subchronic Toxicity Study. Food and Public Health 2015, 5 (4), 138–143.

- Amente, D. T.; Shimelis Mangistu Hailu, D. D. B.; Kitila, A. H. W.; Musa, S. A. Assessment of Meat Handling Practices and Occurrence of Escherichia Coli O157: H7 in Beef Meat and Meat Associated Contact Surfaces along the Meat Supply Chain in Haramaya District, Eastern Ethiopia. IJBB 2022, 4 (1), 06–21.

- Onyeka, L. O.; Adesiyun, A. A.; Keddy, K. H.; Madoroba, E.; Manqele, A.; Thompson, P. N. Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia Coli Contamination of Raw Beef and Beef-Based Ready-to-Eat Products at Retail Outlets in Pretoria, South Africa. J Food Prot 2020, 83 (3), 476–484. [CrossRef]

- Estaleva, C. E. L.; Zimba, T. F.; Sekyere, J. O.; Govinden, U.; Chenia, H. Y.; Simonsen, G. S.; Haldorsen, B.; Essack, S. Y.; Sundsfjord, A. High Prevalence of Multidrug Resistant ESBL- and Plasmid Mediated AmpC-Producing Clinical Isolates of Escherichia Coli at Maputo Central Hospital, Mozambique. BMC Infect Dis 2021, 21 (1), 16. [CrossRef]

- Abebe, E.; Gugsa, G.; Ahmed, M.; Awol, N.; Tefera, Y.; Abegaz, S.; Sisay, T. Occurrence and Antimicrobial Resistance Pattern of E. Coli O157: H7 Isolated from Foods of Bovine Origin in Dessie and Kombolcha Towns, Ethiopia. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2023, 17 (1), e0010706.

- Ahoyo, A. T.; Baba-Moussa, L.; Anago, A. E.; Avogbe, P.; Missihoun, T. D.; Loko, F.; Prevost, G.; Sanni, A.; Dramane, K. Incidence of Infections Dues to Escherichia Coli Strains Producing Extended Spectrum Betalactamase, in the Zou/Collines Hospital Centre (CHDZ/C) in Benin. Medecine et maladies infectieuses 2007, 37 (11), 746–752.

- Beneduce, L.; Spano, G.; Nabi, A. Q.; Lamacchia, F.; Massa, S.; Aouni, R.; Hamama, A. Occurrence and Characterization of Escherichia Coli O157 and Other Serotypes in Raw Meat Products in Morocco. Journal of food protection 2008, 71 (10), 2082–2086. [CrossRef]

- Oje, O. J.; Adelabu, O. A.; Adebayo, A. A.; Adeosun, O. M.; David, O. M.; Moro, D. D.; Famurewa, O. Antibiotic Resistance Profile of β-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia Coli O157: H7 Isolated from Ready-to-Eat Foods in Ekiti State, Nigeria.

- Shecho, M.; Thomas, N.; Kemal, J.; Muktar, Y. Cloacael Carriage and Multidrug Resistance Escherichia Coli O157: H7 from Poultry Farms, Eastern Ethiopia. Journal of veterinary medicine 2017, 2017.

- Adefisoye, M. A.; Okoh, A. I. Identification and Antimicrobial Resistance Prevalence of Pathogenic Escherichia Coli Strains from Treated Wastewater Effluents in Eastern Cape, South Africa. Microbiologyopen 2016, 5 (1), 143–151. [CrossRef]

- Pillay, L.; Olaniran, A. O. Assessment of Physicochemical Parameters and Prevalence of Virulent and Multiple-Antibiotic-Resistant Escherichia Coli in Treated Effluent of Two Wastewater Treatment Plants and Receiving Aquatic Milieu in Durban, South Africa. Environmental monitoring and assessment 2016, 188 (5), 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Malema, M. S.; Abia, A. L. K.; Tandlich, R.; Zuma, B.; Mwenge Kahinda, J.-M.; Ubomba-Jaswa, E. Antibiotic-Resistant Pathogenic Escherichia Coli Isolated from Rooftop Rainwater-Harvesting Tanks in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2018, 15 (5), 892. [CrossRef]

- Diab, M. S.; Tarabees, R.; Elnaker, Y. F.; Hadad, G. A.; Saad, M. A.; Galbat, S. A.; Albogami, S.; Hassan, A. M.; Dawood, M. A.; Shaaban, S. I. Molecular Detection, Serotyping, and Antibiotic Resistance of Shiga Toxigenic Escherichia Coli Isolated from She-Camels and In-Contact Humans in Egypt. Antibiotics 2021, 10 (8), 1021.

- Agbagwa, O. E.; Chinwi, C. M.; Horsfall, S. J. Antibiogram and Multidrug Resistant Pattern of Escherichia Coli from Environmental Sources in Port Harcourt. African Journal of Microbiology Research 2022, 16 (6), 217–222. [CrossRef]

- Chigor, V. N.; Umoh, V. J.; Smith, S. I.; Igbinosa, E. O.; Okoh, A. I. Multidrug Resistance and Plasmid Patterns of Escherichia Coli O157 and Other E. Coli Isolated from Diarrhoeal Stools and Surface Waters from Some Selected Sources in Zaria, Nigeria. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2010, 7 (10), 3831–3841.

- Chissaque, A.; De Deus, N.; Vubil, D.; Mandomando, I. The Epidemiology of Diarrhea in Children Under 5 Years of Age in Mozambique. Curr Trop Med Rep 2018, 5 (3), 115–124. [CrossRef]

- Berendes, D.; Knee, J.; Sumner, T.; Capone, D.; Lai, A.; Wood, A.; Patel, S.; Nalá, R.; Cumming, O.; Brown, J. Gut Carriage of Antimicrobial Resistance Genes among Young Children in Urban Maputo, Mozambique: Associations with Enteric Pathogen Carriage and Environmental Risk Factors. PLoS One 2019, 14 (11), e0225464. [CrossRef]

- Hounkpe, E. C.; Sessou, P.; Farougou, S.; Daube, G.; Delcenserie, V.; Azokpota, P.; Korsak, N. Prevalence, Antibiotic Resistance, and Virulence Gene Profile of Escherichia Coli Strains Shared between Food and Other Sources in Africa: A Systematic Review. Veterinary World 2023, 16 (10), 2016. [CrossRef]

- Madoroba, E.; Malokotsa, K. P.; Ngwane, C.; Lebelo, S.; Magwedere, K. Presence and Virulence Characteristics of Shiga Toxin Escherichia Coli and Non-Shiga Toxin–Producing Escherichia Coli O157 in Products from Animal Protein Supply Chain Enterprises in South Africa. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ombarak, R. A.; Hinenoya, A.; Awasthi, S. P.; Iguchi, A.; Shima, A.; Elbagory, A.-R. M.; Yamasaki, S. Prevalence and Pathogenic Potential of Escherichia Coli Isolates from Raw Milk and Raw Milk Cheese in Egypt. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2016, 221, 69–76. [CrossRef]

- Fayemi, O. E.; Akanni, G. B.; Elegbeleye, J. A.; Aboaba, O. O.; Njage, P. M. Prevalence, Characterization and Antibiotic Resistance of Shiga Toxigenic Escherichia Coli Serogroups Isolated from Fresh Beef and Locally Processed Ready-to-Eat Meat Products in Lagos, Nigeria. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2021, 347, 109191. [CrossRef]

- Abong’o, B. O.; Momba, M. N. Prevalence and Characterization of Escherichia Coli O157: H7 Isolates from Meat and Meat Products Sold in Amathole District, Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. Food microbiology 2009, 26 (2), 173–176.

- Thonda, O. A.; Oluduro, A. O.; Oriade, K. D. Prevalence of Multiple Antibiotic Resistant Escherichia Coli Serotypes in Cow Raw Milk Samples and Traditional Dairy Products in Osun State, Nigeria. British Microbiology Research Journal 2015, 5 (2), 117.

- Omoruyi, I. M.; Uwadiae, E.; Mulade, G.; Omoruku, E. Shiga Toxin Producing Strains of Escherichia Coli (STEC) Associated with Beef Products and Its Potential Pathogenic Effect. Microbiology Research Journal International 2018, 23 (1), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Okechukwu, E. C.; Amuta, E. U.; Gberikon, G. M.; Chima, N.; Yakubu, B.; Igwe, J. C.; Njoku, M. Genetic Characterization of Multiple Antibiotics Resistance Genes of Escherichia Coli Strain from Cow Milk and Its Products Sold in Abuja, Nigeria. Journal of Advances in Biology & Biotechnology 2020, 23 (7), 40–50. [CrossRef]

- Vaillant, V.; De Valk, H.; Saura, C. Systèmes de Surveillance Des Maladies d’origine Alimentaire: Sources, Méthodes, Apports, Limites. Santé animale-alimentation 2012, 3.

- Smith, B. A.; Fazil, A. Quelles Seront Les Répercussions Des Changements Climatiques Sur Les Maladies Microbiennes d’origine Alimentaire Au Canada. Relevé des maladies transmissibles au Canada 2019, 45 (4), 119–125. [CrossRef]

- Racloz, V.; Waltner-Toews, D.; Stärk, K. D. Évaluation Intégrée Des Risques Maladies d’origine Alimentaire. ONE HEALTH, UNE SEULE SANTÉ 2020, 129.

- Moore, D. L.; pédiatrie (SCP), S. canadienne de; d’immunisation, C. des maladies infectieuses et. Les Infections d’origine Alimentaire. Paediatrics & Child Health 2008, 13 (9), 785–788.

- Dubois-Brissonnet, F.; Guillier, L. Les Intoxications Alimentaires Microbiologiques.

- John-Onwe, B. N.; Iroha, I. R.; Moses, I. B.; Onuora, A. L.; Nwigwe, J. O.; Adimora, E. E.; Okolo, I. O.; Uzoeto, H. O.; Ngwu, J. N.; Mohammed, I. D. Prevalence and Multidrug-Resistant ESBL-Producing E. Coli in Urinary Tract Infection Cases of HIV Patients Attending Federal Teaching Hospital, Abakaliki, Nigeria. African Journal of Microbiology Research 2022, 16 (5), 196–201. [CrossRef]

| Virulence genes | Primer | Sequence (5' - 3') | Amplicon size (bp) | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| stx1 | F R |

CGCTGAATGTCATTCGCTCTGC CGTGGTATAGCTACTGTCACC |

302 | 23 |

| stx2 | F R |

CCTCGGTATCCTATTCCCGG CTGCTGTGACAGTGACAAAACGC |

516 | 23 |

| eae | F R |

ACCAGATCGTAACGGCTGCCT AGTTTGGGTTATAACGTCTTCATTG |

499 | 1 |

| Type of resistance | Phenotypes | Isolates | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food | Hands | ||

|

Multidrug resistance |

AMP, AMC, CEP, GNM, TET | 2 (5,7 %) | - |

| AMP, AMC, CEP, CTX, TET | 1 (2,9 %) | 1 (5 %) | |

| AMP, AMC, CEP, FOX, TET | - | 1 (5 %) | |

| AMP, AMC, CEP, CIP, TET | 1 (2,9 %) | - | |

| AMP, AMC, CEP, TET | 9 (25,7 %) | 10 (50 %) | |

| AMP, AMC, FOX, TET | 1 (2,9 %) | - | |

| AMP, CEP, GNM, TET | 1 (2,9 %) | - | |

| AMP, AMC, CEP, CIP | - | 1 (5 %) | |

| AMP, CEP, FOX, TET | 1 (2,9 %) | 1 (5 %) | |

| AMP, AMC, CEP, GNM | 1 (2,9 %) | - | |

| AMP, AMC, CEP | 3 (8,6 %) | 4 (20 %) | |

| AMC, CEP, TET | 6 (17,1 %) | 1 (5 %) | |

| AMP, CEP, GNM | 1 (2,9 %) | - | |

| AMC, CEP | 8 (22,9 %) | 1 (5 %) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).