Submitted:

14 May 2025

Posted:

15 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: 90C26; 65K05; 49K35; 41A25

1. Introduction

2. Preliminaries

- (i)

-

The Frechet sub-differential of f at is denoted by and defined as:Among others, we set when .

- (ii)

- The limiting sub-differential of f at is written as and defined by

- (i)

- From Definition 3, which implies that holds for all , and given that is a closed set, is also a closed set.

- (ii)

- Suppose that is a sequence that converges to , and converges to with . Then, by the definition of the sub-differential, we have .

- (iii)

- If is a local minimum of f, then it follows that .

- (vi)

- Assuming that is a continuously differentiable function, we can derive:

3. Algorithm and Convergence Analysis

- (i)

- In NIP-ADMM, the inertial parameters η and θ are both in , and S is a positive semi-definite matrix.

- (ii)

- The update scheme for the y-subproblem adopts the gradient descent method, where is the gradient of the function L with respect to y, and γ is called the learning rate.

- (iii)

- The inertial structure we adopted employs a structurally balanced acceleration strategy. This update strategy is mathematically symmetric, with the only distinction being the values of the parameters η and θ.

| Algorithm 1: NIP-ADMM |

|

Initialization: Input , and , let , and . Given constants . Set .

While "not converge" Do Compute . Execute to determine . Calculate . Update dual variable . Let . End While Output: output of the problem (4). |

- (ii)

- S is a positive semidefinite matrix.

- (iii)

- For convenience, we introduce the following symbols:

- (iv)

- To analyze the monotonicity of , we set .

- (i)

- M and are two non-empty compact sets. As , it follows that and .

- (ii)

- .

- (iii)

- .

- (iv)

- The sequence converges, and .

- (i)

- Based on the definitions of M and , the conclusion can be satisfied.

- (ii)

- Combining Lemma 5 with the definitions of and , we obtain the desired conclusion.

- (iii)

-

Let , then we obtain that a subsequence of can converge to . By combining Lemma 5, as , one has , which implies . On one hand, noting that is the optimal solution to the x-subproblem, we haveFrom Lemma 6, we know that , and combining this with , we conclude that the equality holds. On the other hand, since is a lower semi-continuous function, we deduce that , so one getsMoreover, given the closedness of and the continuity of , along with and the optimality condition of NIP-ADMM (6), we assert thatand as established in Definition 4.

- (v)

-

Let , and assume that there exists a subsequence of that converges to . Combining the relations (14), (19), and the continuity of g, we haveConsidering that is monotonically non-increasing, it follows that is convergent. Consequently, for any , the relationship can be established as

- (i)

-

For any and given that , it follows from Lemma 1 and Lemma 5 that there exists a constant such that

- (ii)

-

Assume that for any , the inequality holds. Sinceit follows that for any , there exists such that for all , we have:Moreover, noting thatit implies that for any , there exists such that for all , the inequality holds:Hence, given and , when , we haveAnd, based on Lemma 3, the following holds for all , it can be deduced thatFurthermore, using the concavity of , we derive the following:Noting the fact that , together with the conclusion obtained in Lemma 7, we can infer thatwhere represents and represents Combining Lemma 5, we can rewrite (22) as followswhere (22) can be equivalently expressed asBy applying the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality and multiplying both sides by 6, we obtainThen, by further applying the fundamental inequality, we can deduce thatNext, summing up (23) from to and rearranging the terms, one getsFurthermore, as and m approaches positive infinity, we can conclude thatwhich impliesThis demonstrates that forms a Cauchy sequence, which ensures its convergence. By applying Theorem 1, it follows that converges to a critical point of .

4. Numerical Simulations

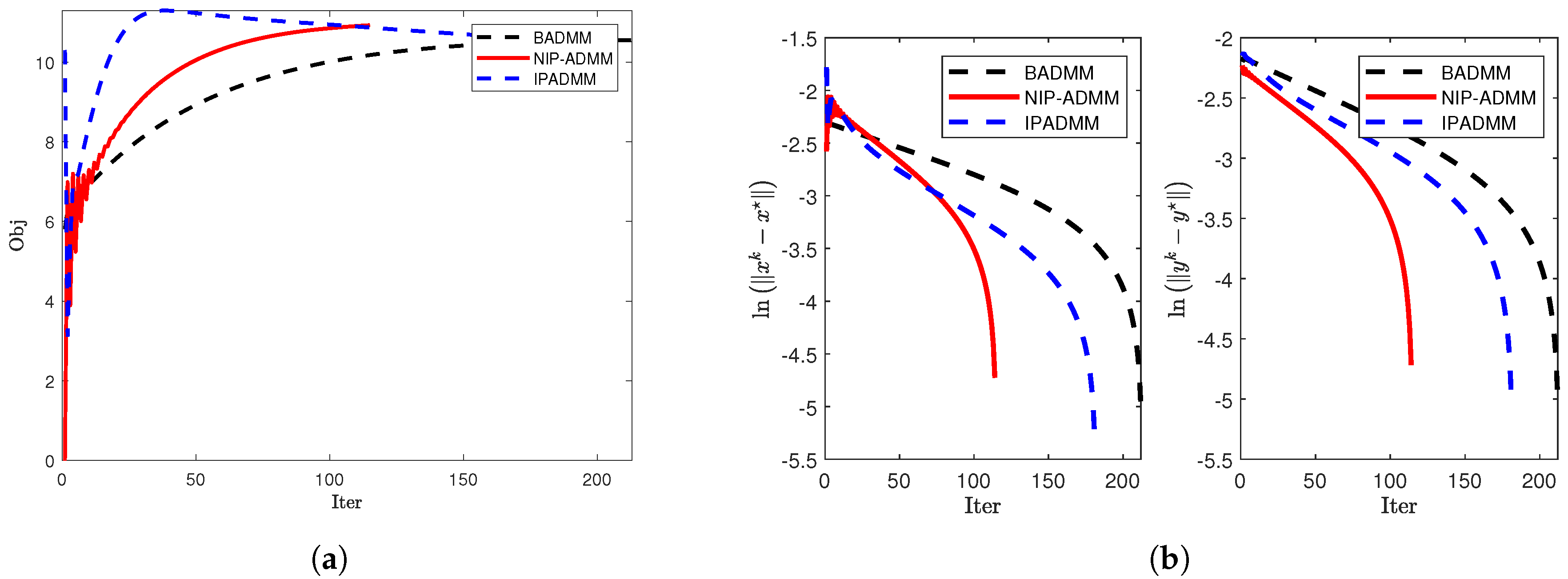

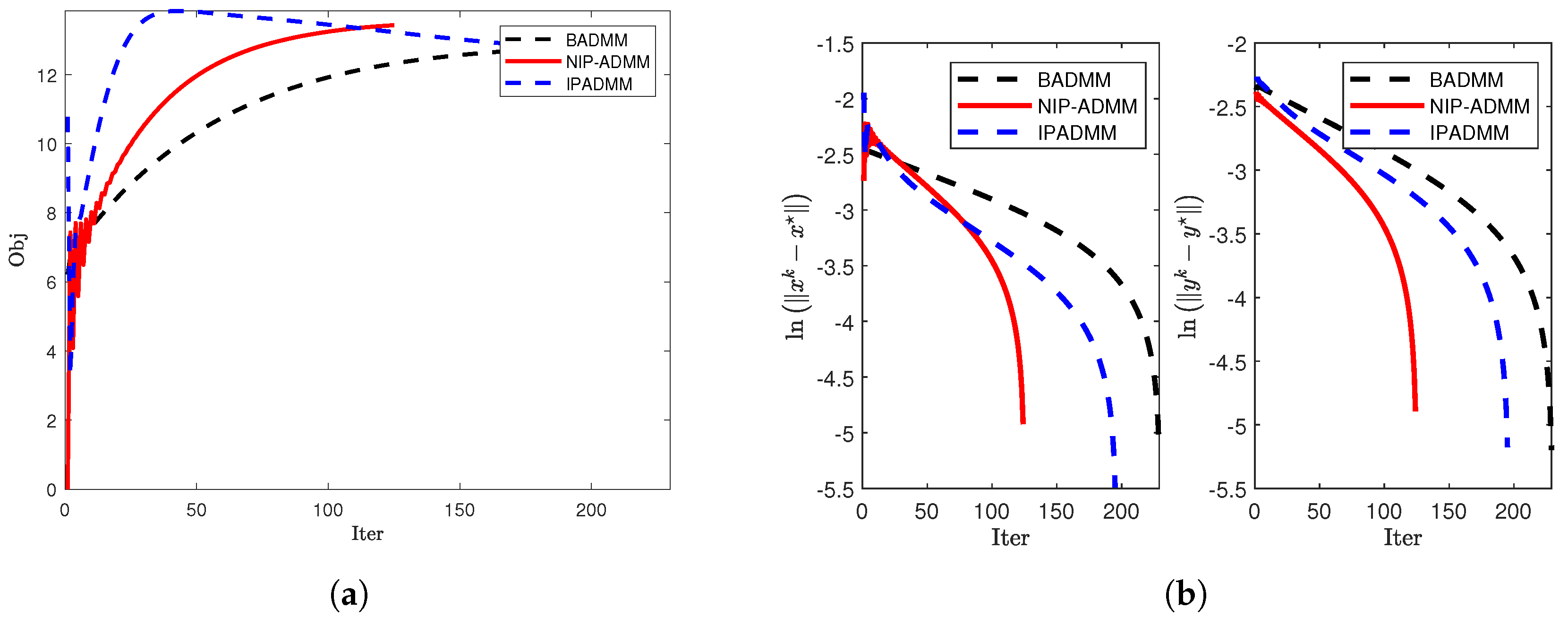

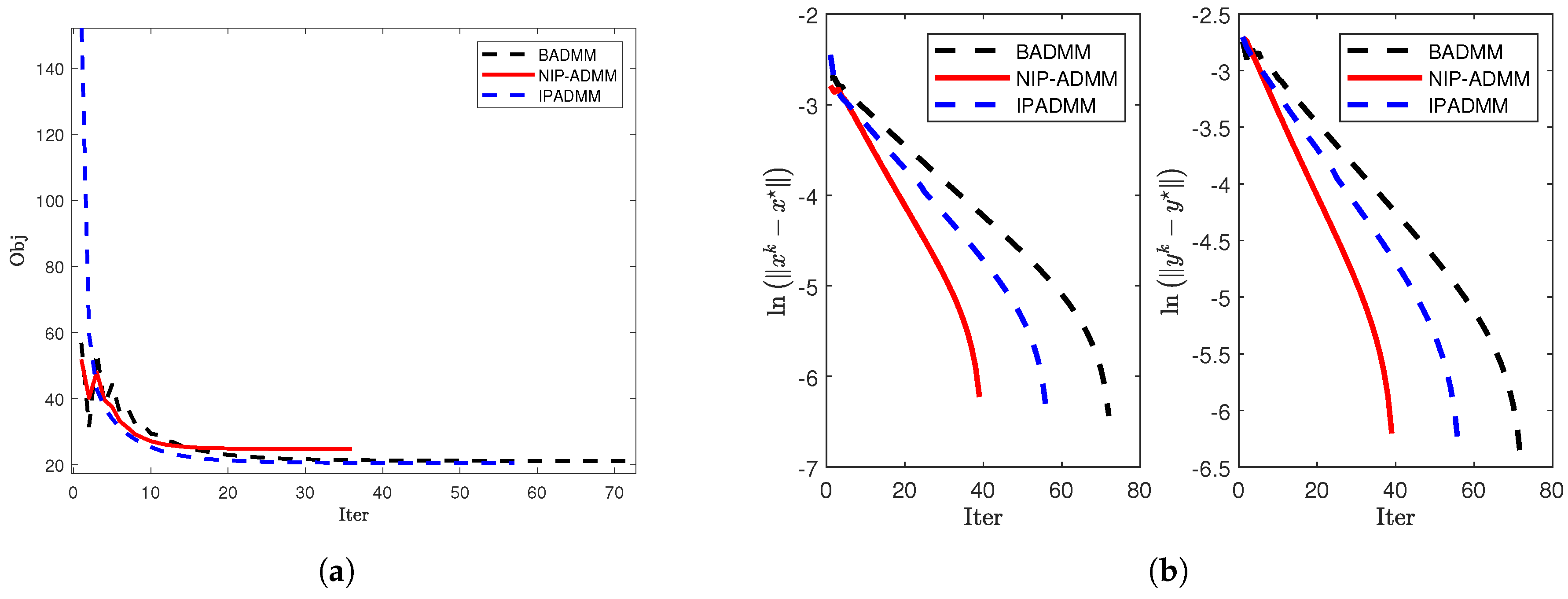

4.1. Signal Recovery

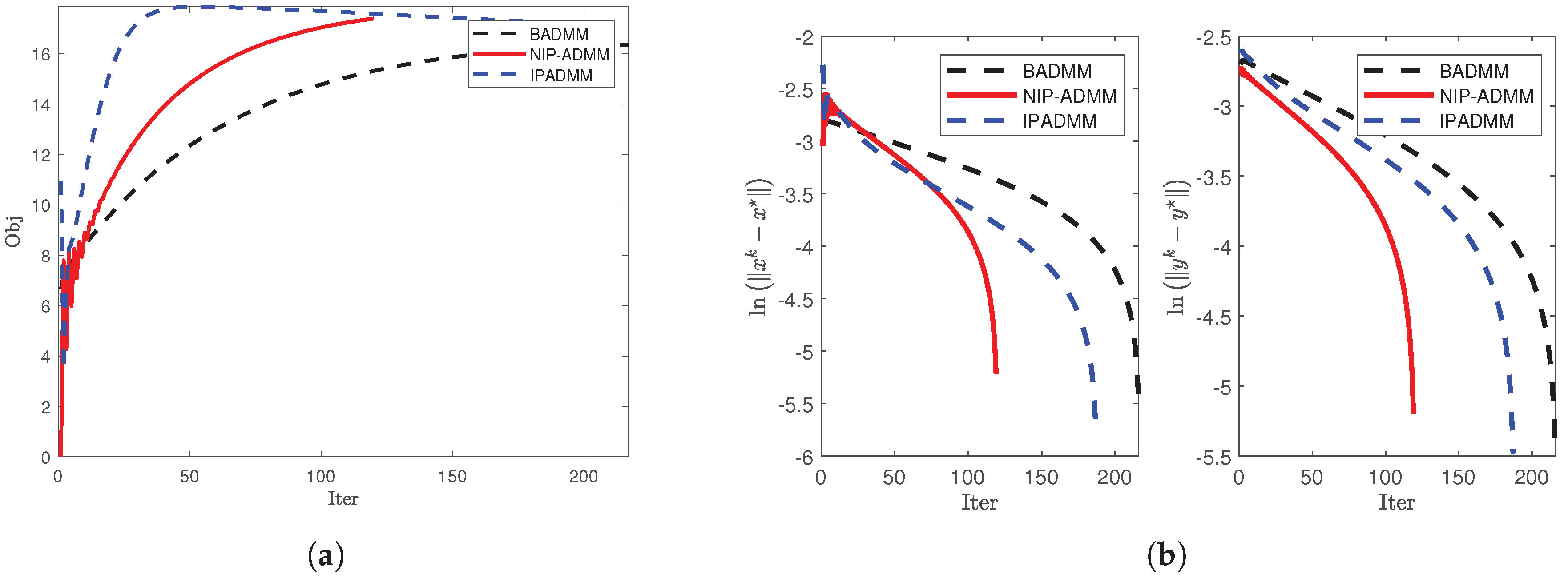

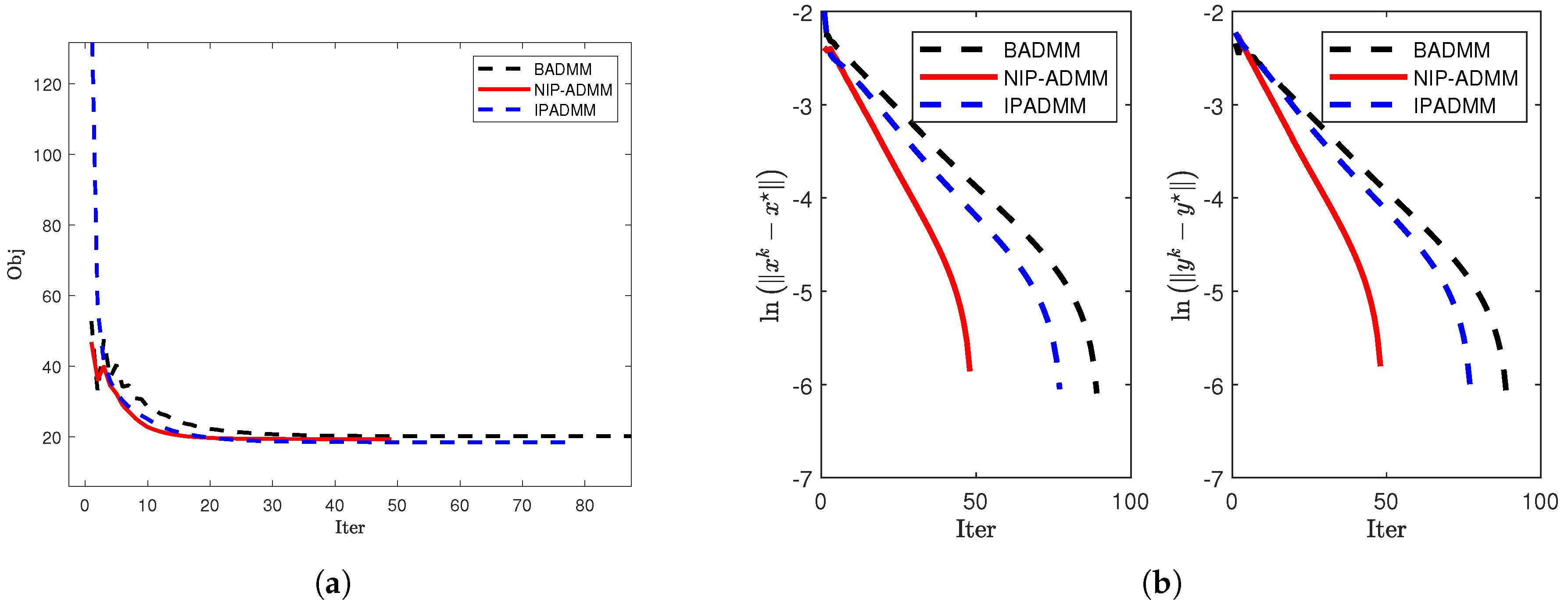

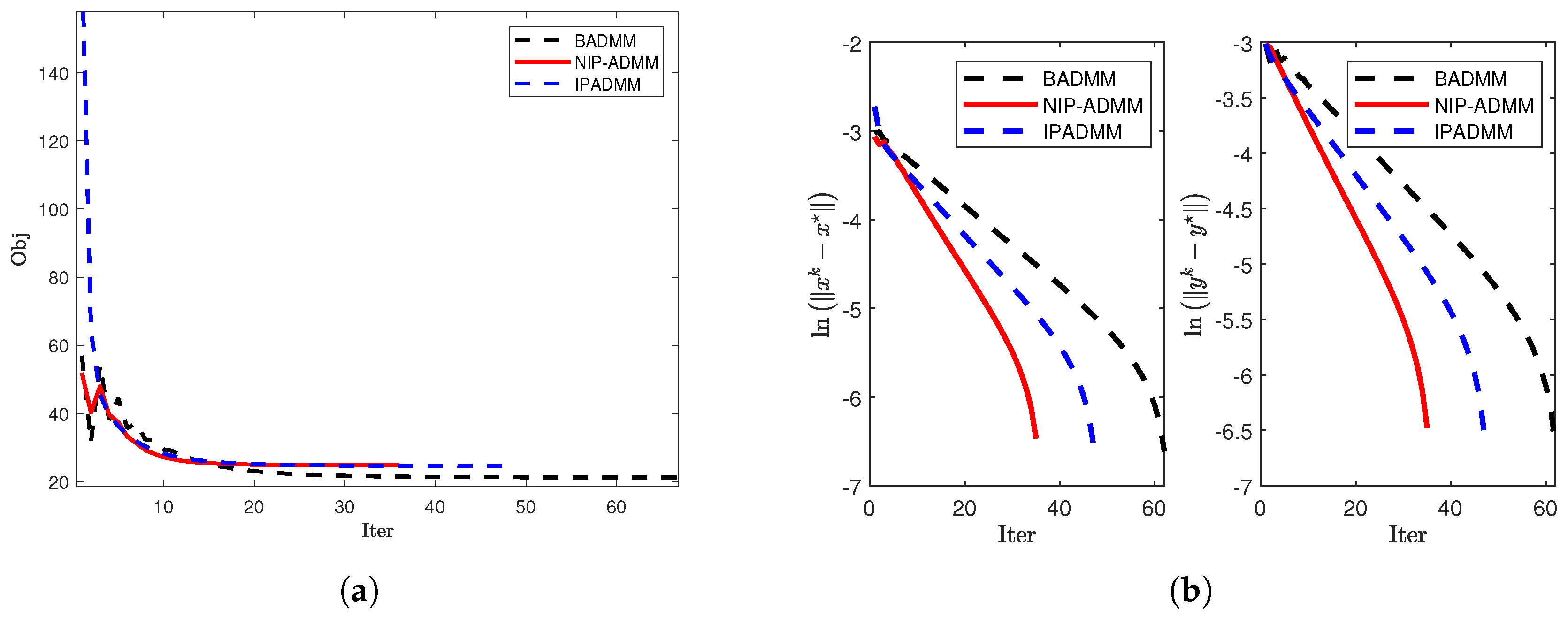

4.2. SCAD Penalty Problem

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, S.R.; Wang, Q.H.; Zhang, B.X.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Li, L.L.; Huang, G.; Zhang, Z.G.; Feng, B.; Yu, T.Y. Cauchy non-convex sparse feature selection method for the high-dimensional small-sample problem in motor imagery EEG decoding. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1292724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doostmohammadian, M.; Gabidullina, Z.R.; Rabiee, H.R. Nonlinear perturbation-based non-convex optimization over time-varying networks. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2024, 11, 6461–6469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiddeman, B.; Ghahremani, M. Principal component wavelet networks for solving linear inverse problems. Symmetry. 2021, 13, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.C.; Liu, Y.; Hu, C.; Jiang, H.J. Distributed nonconvex optimization subject to globally coupled constraints via collaborative neurodynamic optimization. Neural Netw. 2025, 184, 107027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, G.; Fu, H.; Liu, Y.F. High-dimensional cost-constrained regression via nonconvex optimization. Technometrics. 2021, 64, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merzbacher, C.; Mac Aodha, O.; Oyarzún, D.A. Bayesian optimization for design of multiscale biological circuits. ACS Synth. Biol. 2023, 12, 2073–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.j.; Koh, K.; Lustig, M.; Boyd, S.; Gorinevsky, D. An interior-point method for large-scale ℓ1-regularized least Squares. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2007, 1, 606–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chartrand, R.; Staneva, V. Restricted isometry properties and nonconvex compressive sensing. Inverse Problems. 2008, 24, 035020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.S.; Lin, S.B.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Z.B. L1/2 regularization: convergence of iterative half thresholding algorithm. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2014, 62, 2317–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.Y.; Selesnick, I.W. Group-sparse signal denoising: non-convex regularization, convex optimization. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2014, 62, 3464–3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.L. Sparse Bayesian learning for sparse signal recovery using ℓ1/2-norm. Appl. Acoust. 2023, 207, 109340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yan, M.; Rahimi, Y.; Lou, Y.F. Accelerated schemes for the L1/L2 minimization. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2020, 68, 2660–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.; Teboulle, M. A fast iterative shrinkage-thresholding algorithm for linear inverse problems. SIAM J. Imaging Sci. 2009, 2, 183–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.Q.; Li, R.Z. Variable selection via nonconcave penalized likelihood and its oracle properties. J. Amer. Statist. Assoc. 2001, 96, 1348–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.C.; Zhang, H.C.; Li, J.C. A parameterized proximal point algorithm for separable convex optimization. Optim. Lett. 2018, 12, 1589–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, F.; Liu, P.L.; Liu, Y.P.; Qiu, R.C.; Yu, W.X. Robust sparse recovery in impulsive noise via ℓp-ℓ1 optimization. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2017, 65, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.M.; Gao, J.B.; Qian, J.J.; Yang, J.; Xu, C.Y.; Zhang, B. Linear regression problem relaxations solved by nonconvex ADMM with convergence analysis. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2023, 34, 828–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, B.P.W.; Hong, M.Y. Alternating direction method of multipliers for penalized zero-variance discriminant analysis. Comput. Optim. Appl. 2016, 64, 725–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zietlow, C.; Lindner, J.K.N. ADMM-TGV image restoration for scientific applications with unbiased parameter choice. Numer. Algorithms. 2024, 97, 1481–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, F.M.; Liang, J.W.; Zhang, X.Q. A stochastic alternating direction method of multipliers for non-smooth and non-convex optimization. Inverse Problems. 2021, 37, 075009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, N.; Boyd, S. Proximal Algorithms; Now Publishers: Braintree, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, M.Y.; Luo, Z.Q.; Razaviyayn, M. Convergence analysis of alternating direction method of multipliers for a family of nonconvex problems. SIAM J. Optim. 2016, 26, 337–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.H.; Xu, Z.B.; Xu, H.K. Convergence of Bregman alternating direction method with multipliers for nonconvex composite problems. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1410.8625. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, W.; Shang, Y.; Jin, Z.; Fan, Y. Semi-proximal ADMM for primal and dual robust Low-Rank matrix restoration from corrupted observations. Symmetry. 2024, 16, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Han, D.R.; Wu, T.T. Convergence of alternating direction method for minimizing sum of two nonconvex functions with linear constraints. Int. J. Comput. Math. 2016, 94, 1653–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yin, W.T.; Zeng, J.S. Global convergence of ADMM in nonconvex nonsmooth optimization. J. Sci. Comput. 2019, 78, 29–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.H.; Cao, W.F.; Xu, Z.B. Convergence of multi-block Bregman ADMM for nonconvex composite problems. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2018, 61, 122101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, R.F.; Sidky, E.Y. Convergence for nonconvex ADMM, with applications to CT imaging. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2024, 25, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.F.; Yan, J.C.; Jin, B.; Li, W.H. Distributed and parallel ADMM for structured nonconvex optimization problem. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 51, 4540–4552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez, F.; Attouch, H. An inertial proximal method for maximal monotone operators via discretization of a nonlinear oscillator with damping. Set-Valued Anal. 2001, 9, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.M.; Li, M. General inertial proximal gradient method for a class of nonconvex nonsmooth optimization problems. Comput. Optim. Appl. 2019, 73, 129–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Chan, R.H.; Ma, S.Q.; Yang, J.F. Inertial proximal ADMM for linearly constrained separable convex optimization. SIAM J. Imaging Sci. 2015, 8, 2239–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, M.T.; Zhang, Y.; Jian, J.B. An inertial proximal alternating direction method of multipliers for nonconvex optimization. Int. J. Comput. Math. 2020, 98, 1199–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Q.; Shao, H.; Liu, P.J.; Wu, T. An inertial proximal partially symmetric ADMM-based algorithm for linearly constrained multi-block nonconvex optimization problems with applications. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2023, 420, 114821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.L.N.; Melo, J.G.; Monteiro, R.D.C. Convergence rate bounds for a proximal ADMM with over-relaxation stepsize parameter for solving nonconvex linearly constrained problems. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1702.01850. [Google Scholar]

- Attouch, H.; Bolte, J.; Redont, P.; Soubeyran, A. Proximal alternating minimization and projection methods for nonconvex problems: An approach based on the Kurdyka-Łojasiewicz inequality. Math. Oper. Res. 2010, 35, 438–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolte, J.; Sabach, S.; Teboulle, M. Proximal alternating linearized minimization for nonconvex and nonsmooth problems. Math. Program. 2014, 146, 459–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesterov, Y. Introductory Lectures on Convex Optimization: A Basic Course; Springer: NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.B.; Chang, X.Y.; Xu, F.M.; Zhang, H. L1/2 regularization: A thresholding representation theory and a fast solver. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2012, 23, 1013–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Iter | CPUT(s) | Iter | CPUT(s) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.2 | 0.2 | 75 | 2.2392 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 54 | 1.6014 |

| 0.3 | 0.2 | 78 | 2.3039 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 49 | 1.4583 |

| 0.3 | 0.3 | 69 | 1.9476 | 0.8 | 0.75 | 49 | 1.4309 |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 60 | 1.7622 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 56 | 1.6445 |

| 0.6 | 0.6 | 56 | 1.6516 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 84 | 2.4614 |

| m | n | NIP-ADMM | IPADMM | BADMM | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iter | CPUT(s) | Obj | Iter | CPUT(s) | Obj | Iter | CPUT(s) | Obj | ||

| 1000 | 1000 | 49 | 1.2698 | 19.36 | 78 | 2.1407 | 18.46 | 90 | 2.3407 | 20.14 |

| 1500 | 2000 | 44 | 4.9152 | 23.17 | 72 | 8.4978 | 22.12 | 76 | 8.5387 | 23.69 |

| 3000 | 3000 | 40 | 15.0464 | 21.02 | 57 | 22.3823 | 20.56 | 73 | 27.4115 | 21.18 |

| 3000 | 4000 | 55 | 34.0601 | 23.21 | 98 | 62.8206 | 23.11 | 76 | 48.3825 | 23.22 |

| 4000 | 5000 | 36 | 40.6110 | 24.02 | 53 | 61.7431 | 23.09 | 65 | 74.4521 | 24.03 |

| 4500 | 5500 | 40 | 61.7638 | 24.05 | 45 | 71.7627 | 23.79 | 67 | 102.6028 | 24.06 |

| 6000 | 6000 | 40 | 88.7702 | 24.99 | 48 | 108.3045 | 24.56 | 63 | 135.8133 | 25.00 |

| Iter | CPUT(s) | Iter | CPUT(s) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.2 | 0.2 | 196 | 2.0092 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 149 | 1.5017 |

| 0.3 | 0.2 | 187 | 1.9122 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 134 | 1.3693 |

| 0.3 | 0.3 | 181 | 1.8690 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 133 | 1.3503 |

| 0.4 | 0.5 | 170 | 1.7650 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 127 | 1.3467 |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 159 | 1.6438 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 126 | 1.3100 |

| m | n | NIP-ADMM | IPADMM | BADMM | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iter | CPUT(s) | Obj | Iter | CPUT(s) | Obj | Iter | CPUT(s) | Obj | ||

| 1000 | 1000 | 121 | 1.3366 | 10.91 | 213 | 2.3065 | 10.55 | 182 | 1.9632 | 10.55 |

| 1000 | 1300 | 115 | 1.9246 | 12.96 | 211 | 3.5724 | 12.48 | 174 | 2.9611 | 13.13 |

| 1500 | 1000 | 130 | 1.9270 | 8.92 | 228 | 3.2943 | 8.59 | 172 | 2.4709 | 7.49 |

| 1500 | 1300 | 140 | 3.0474 | 13.38 | 259 | 5.7832 | 12.90 | 215 | 4.7147 | 11.88 |

| 1500 | 1500 | 125 | 3.6104 | 13.43 | 230 | 6.6865 | 12.81 | 196 | 5.4584 | 12.71 |

| 1800 | 1500 | 146 | 4.6432 | 13.47 | 257 | 8.0396 | 12.94 | 209 | 6.1925 | 11.83 |

| 1800 | 2000 | 115 | 5.8341 | 15.00 | 210 | 10.7513 | 14.29 | 182 | 9.1033 | 14.69 |

| 2500 | 2000 | 142 | 8.9043 | 14.95 | 250 | 15.6397 | 14.29 | 201 | 12.2370 | 13.07 |

| 2900 | 2700 | 134 | 15.3647 | 17.70 | 245 | 28.4289 | 16.71 | 203 | 22.9945 | 16.50 |

| 3000 | 3000 | 125 | 17.1686 | 17.20 | 217 | 34.1575 | 16.34 | 188 | 25.0864 | 17.22 |

| 3500 | 3000 | 128 | 20.2808 | 16.87 | 234 | 37.1725 | 15.84 | 194 | 30.6876 | 15.94 |

| 3500 | 3500 | 123 | 24.5455 | 19.80 | 223 | 44.4163 | 18.69 | 200 | 39.2771 | 19.43 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).