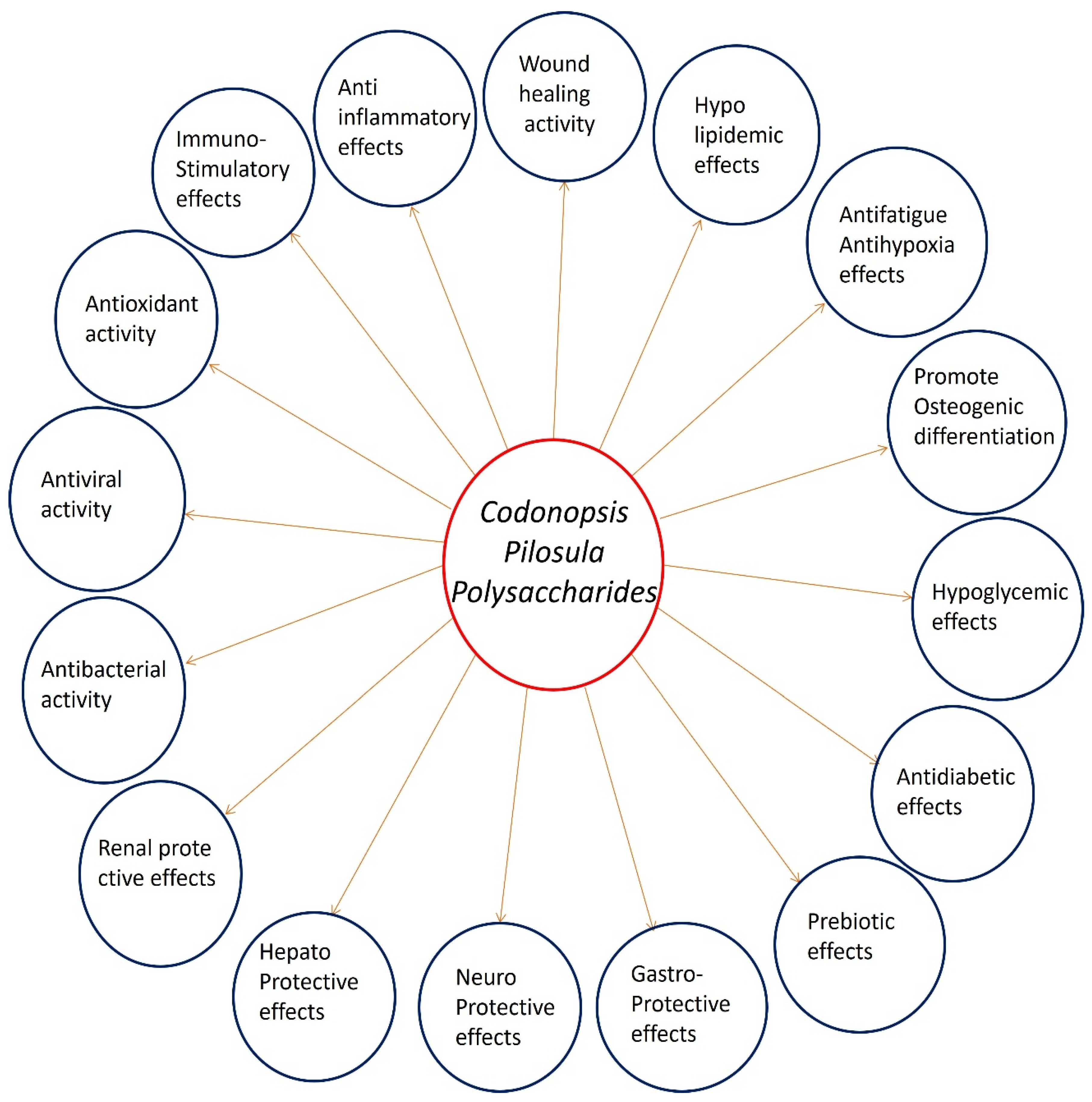

2.1. Immunomodulatory Effects

CPPs exhibit a remarkable capacity to both stimulate and suppress immune responses, with their biological effects being highly dependent on structural characteristics including MW distribution, glycosidic linkage patterns, and monosaccharide composition. Various studies demonstrated that CPPs could simultaneously modulate multiple immune components, including innate immune cells (macrophages, NK cells), adaptive immune cells (T and B lymphocytes), cytokine networks, and even the gut-immune axis. The growing body of evidence suggests that CPPs function through sophisticated structure-activity relationships, making them promising candidates for development as functional food ingredients and immunotherapeutic agents [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28].

Wang et al. (1996) demonstrated the time-dependent immunomodulatory effects of CPPS. Their study showed that short-term CPPS administration (4 weeks) suppressed immune function, reducing T-cell (ConA) and B-cell (LPS) mitogenic responses and inhibiting macrophage reactive nitrogen intermediate production. However, extending treatment to 8 weeks reversed these effects, enhancing splenocyte proliferation and restoring immune responsiveness. This biphasic pattern—initial immunosuppression followed by immunostimulation—occurred without affecting macrophage pinocytic activity or superoxide generation. While these findings highlighted CPPs as unique temporal immunomodulators, the molecular mechanisms behind this time-dependent shift remained unclear [

19]. Zhang et al. (2017) provided critical structural-functional insights through characterization of a pectic polysaccharide (CPP1c) with molecular weights of 1.26-1.49 × 10⁵ Da and

→4)-α-D-GalpA and

→2)-α-L-Rhap linkages. Using an aging mouse model (SAMP8), the researchers demonstrated CPP1c's remarkable ability to enhance both cellular and humoral immunity. CPP1c significantly promoted lymphocyte proliferation while modulating key T-cell subsets (CD4+, CD8+) and co-stimulatory molecules (CD28+, CD152+). At the cytokine level, CPP1c boosted production of IL-2, TNF-α, and IFN-γ, indicating potent Th1 immune stimulation. Mechanistic studies revealed upregulation of CD28, PI3K, and p38MAPK at both transcriptional and translational levels, suggesting activation through TCR/CD28 signaling pathways. Additionally, CPP1c facilitated lymphocyte homing, further demonstrating its comprehensive immunomodulatory potential [

20]. Fu et al. (2018) expanded our understanding of CPP immunomodulation by investigating their effects on gut-associated lymphoid tissue in cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppression. Their comprehensive approach showed that CPP administration (50-200 mg/kg) for 7 days effectively restored systemic immunity through multiple mechanisms. The treatment significantly improved immune organ indices (spleen, thymus, and liver) and enhanced both cellular (IFN-γ, IL-2) and humoral (IgG) immune markers. Notably, CPPs exhibited exceptional mucosal immunoprotective effects, as evidenced by restoration of ileal secretory IgA levels - crucial for intestinal immune defense. Fu et al (2018) findings revealed CPPs as unique immunomodulators capable of simultaneously targeting systemic immunity and gut mucosal defenses, with particular relevance for chemotherapy-induced immunosuppression and intestinal barrier dysfunction [

21].

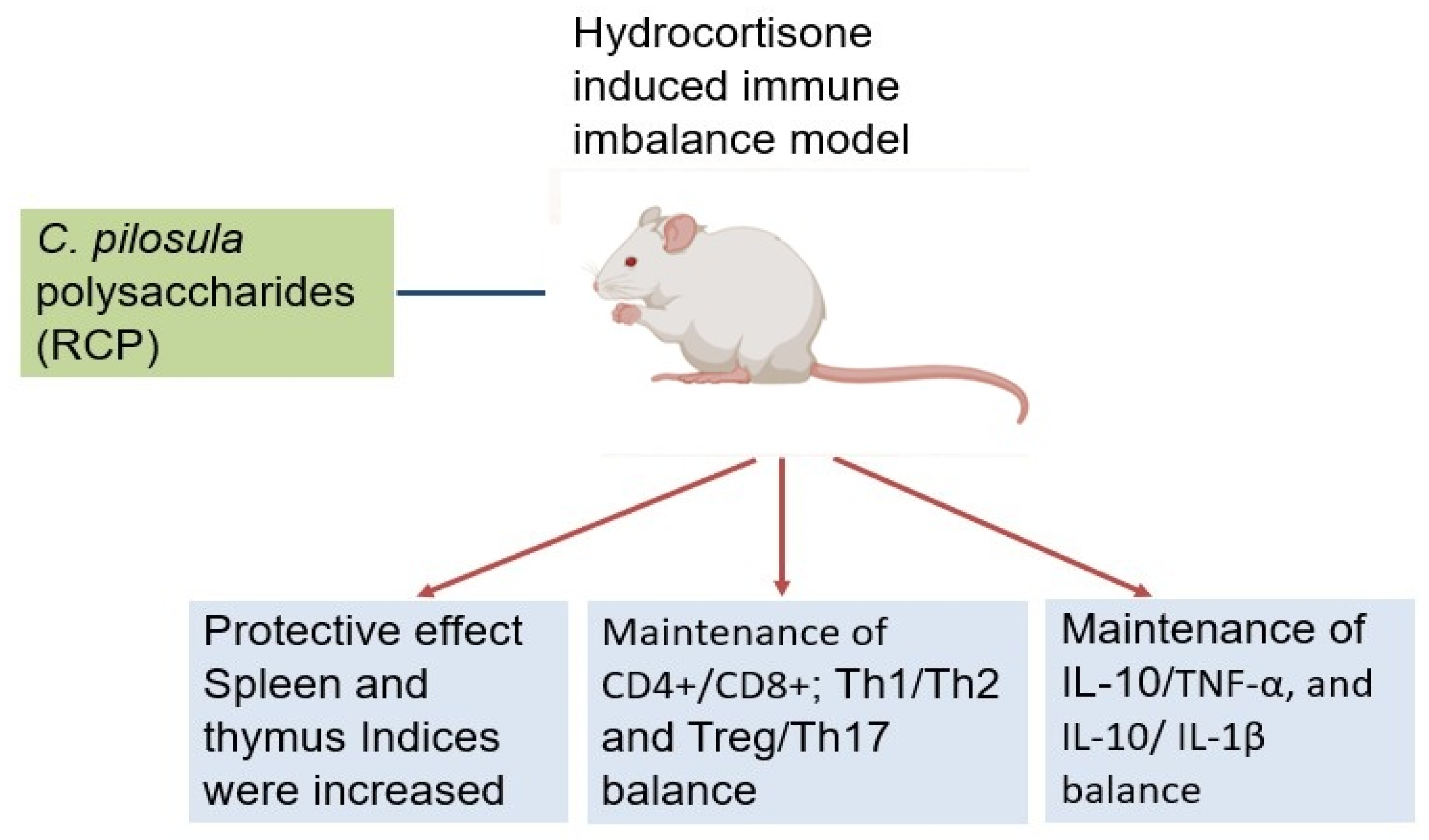

Deng et al. (2019) provided crucial insights into CPPs' ability to maintain immune balance under immunosuppressive conditions. Their study focused on Radix Codonopsis polysaccharide (RCP) in a hydrocortisone-induced immune imbalance model. The 15-day pretreatment protocol effectively preserved immune organ mass (spleen and thymus indices) despite glucocorticoid challenge. Flow cytometry analysis revealed RCP's remarkable capacity to stabilize multiple T-cell populations, maintaining equilibrium between CD8+ T cells, regulatory T cells (Tregs), and Th17 cells. RCP also preserved critical immune ratios including CD4+/CD8+, Th1/Th2, and Treg/Th17 balances. At the cytokine level, RCP maintained homeostasis between pro-inflammatory (TNF-α, IL-1β) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10) factors (

Figure 1). Their findings highlighted RCP's potential as a therapeutic agent for conditions involving T-cell dysregulation, such as autoimmune diseases, transplant rejection, and chronic inflammation, where immune balance restoration is paramount [

22].

The studies by Sun et al. (2019) and Li et al. (2022) systematically investigated how MW influences CPP immunomodulatory directionality. Sun's team characterized three distinct polysaccharides (RCNP with 11.4 kDa, RCAP-1 with 50.9 kDa, and RCAP-2 with 258 kDa), revealing striking functional differences. While the pectin-type RCAP-1 and RCAP-2 significantly stimulated macrophage NO production without toxicity, the neutral RCNP showed minimal activity. Li's research further elucidated this MW-activity relationships by comparing low-MW PSDSs-1 (3.3 kDa) and high-MW PSDSs-2 (>2000 kDa). The low-MW fraction exhibited clear pro-inflammatory activity (increased TNF-α, IL-6; decreased IL-10), while the high-MW fraction showed opposite, anti-inflammatory effects. These two studies established MW as a critical determinant of immunomodulatory direction, providing a scientific basis for targeted CPP applications in different immune contexts [

23,

24]. Gao et al. (2020) demonstrated how chemical modification could enhance CPP immunomodulatory potency through selenylation. Structural analysis revealed that selenization transformed CPPS from a galactose/arabinose-rich polymer (52.2%/29.9%) to a glucose-dominant (96.3%) derivative (sCPPS). This modification significantly boosted biological activity: in vitro, sCPPS at 3.125 μg/mL optimally enhanced lymphocyte proliferation and CD4+/CD8+ ratios when combined with PHA or LPS. In vivo studies using OVA-immunized mice showed sCPPS (0.1 mg/mL) consistently outperformed native CPPS in elevating immunoglobulin (IgG, and IgM) and cytokine (IFN-γ, IL-2, and IL-4) levels throughout the 28-day observation period. The modified polysaccharide, sCPPS particularly excelled in balancing Th1/Th2 responses, with IFN-γ and IL-2 levels remaining significantly higher than CPPS groups from day 7 onward. These findings not only demonstrated selenium's role in enhancing immunopotency but also established sCPPS as a superior candidate for vaccine adjuvants and immunotherapeutic applications [

16].

The studies by Li et al. (2021) and Ji et al. (2022) focused on low-MW CPP variants and their macrophage-activating properties. Li's team isolated a unique 1,698 Da glucan (CPC) featuring an unusual branched structure (1,4-linked α-D-glucose backbone with 1,6-linked β-D-glucose branches). This small polysaccharide demonstrated remarkable dose-dependent (250-1000 μg/mL) immunostimulatory effects in RAW 264.7 macrophages, enhancing proliferation, phagocytosis, and ROS production comparable to LPS. It uniquely balanced pro-inflammatory (TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10) cytokine secretion while upregulating iNOS expression. Ji's research optimized extraction of a 4.23 kDa glucofructan (CPPs) with (2

→1)-β-D-Fruf backbone and (2

→6)-β-D-Fruf branches, showing potent NO and cytokine (IL-6, TNF-α) induction without cytotoxicity. Both studies highlighted how specific low-MW structures could effectively activate macrophages through potential pattern recognition receptor interactions, offering advantages for targeted immune stimulation [

25,

26]. Sun et al. (2022) investigated the immunomodulatory potential of a chitosan-graphene oxide-Codonopsis pilosula polysaccharide (CS-GO-CPP) complex on RAW264.7 macrophages. The study synthesized CS-GO nanocomposites through electrostatic interaction and loaded them with CPP to form CS-GO-CPP. Structural characterization using FTIR, zeta potential, and thermogravimetric analysis confirmed the composite's stability without altering CPP’s core structure while enhancing its thermal properties. Immunological assays revealed that CS-GO-CPP (0.78–12.5 μg·mL⁻¹) significantly boosted macrophage phagocytosis (P < 0.05) and upregulated NO, IL-4, and IFN-γ secretion. Additionally, it elevated surface markers (CD40, CD86, F4/80) and activated the NF-κB pathway, evidenced by p65 nuclear translocation [

12].

Long et al. (2024) explored CPP applications in oncology through development of selenium nanoparticle conjugates (CPP-SeNPs). In H22 tumor-bearing mice, these nanocomposites showed impressive dose-dependent antitumor activity, with the high-dose group (1.5 mg/kg) achieving 47.18% tumor growth inhibition while protecting immune organ function. Mechanistic studies revealed CPP-SeNPs operated through multiple synergistic pathways: enhancing systemic immunity (elevated TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-2; increased NK cytotoxicity; boosted macrophage phagocytosis; promoted lymphocyte proliferation) while directly inducing tumor apoptosis via mitochondrial pathway regulation (increased Bax, decreased Bcl-2). The researchers also identified potential gut microbiota modulation and SCFA metabolism as contributing mechanisms. These multifactorial actions position CPP-SeNPs as promising combinatory agents for cancer immunotherapy, capable of simultaneously enhancing immune surveillance and directly targeting tumor cells [

27]. Fu et al. (2025) conducted the most comprehensive structure-activity analysis, comparing four CPP variants (CPW, CPS0.2, CPS0.5, CPS1), revealed how subtle structural differences dramatically influence immunomodulatory properties. CPW (5,722 Da, 83% fructose) showed potent anti-inflammatory activity, suppressing LPS-induced IL-1β and TNF-α in THP-1 cells. In contrast, CPS0.2 (bimodal MW distribution with 74.6% <10,000 Da, 15% glucose) emerged as the strongest immunostimulant, likely due to enhanced receptor interaction from its extended chain conformation. The intermediate CPS0.5 (6% glucose) showed moderate activity, while high-MW CPS1 (31,981 Da, 61% fructose) was least active. The above studies established monosaccharide composition, MW distribution, and chain conformation as critical determinants of immunomodulatory specificity, providing a roadmap for rational design of CPP-based immunotherapeutics [

28]. The collective evidence from these studies (

Table 1) revealed CPPs as sophisticated, multifunctional immunomodulators with immense therapeutic potential.

2.2. Anticancer Activity of CPPs

CPPs have emerged as promising natural anticancer agents with multifaceted mechanisms of action. Extensive research over the past decade has revealed their ability to directly inhibit tumor cell proliferation while modulating immune responses against cancer. Their excellent safety profiles and multi-target mechanisms position CPPs as attractive candidates for cancer therapy and prevention. The anticancer potential of CPPs was systematically investigated by Jian-Ping (2011), who isolated two novel polysaccharides (CPS-3 and CPS-4) through DEAE-52 cellulose chromatography. CPS-3, with a MW of 1.24×10⁶ Da and unique xylose-glucose-galactose composition (1.17:0.96 ratio), showed selective cytotoxicity against gastric adenocarcinoma BGC-823 cells. CPS-4, comprising two fractions (1.96×10⁶ and 1.51×10⁶ Da), exhibited potent growth suppression of hepatoma Bel-7402 cells [

29]. Xin et al. (2012) significantly advanced understanding of CPP mechanisms by characterizing an acidic polysaccharide (CPPA, MW: 4.2×10⁴ Da) with potent anti-metastatic activity against ovarian cancer HO-8910 cells. Their comprehensive approach demonstrated CPPA's multimodal action: dose-dependent proliferation inhibition (reducing viability to 39.35% at 200 μg/mL), 69% suppression of cell migration in transwell assays, and significant impairment of matrigel adhesion. The groundbreaking discovery of CD44 downregulation (p<0.01-0.001) provided mechanistic insight into CPPA's anti-metastatic effects, highlighting its ability to disrupt cancer cell-extracellular matrix interactions critical for metastasis [

30]. Xu et al. (2012) conducted pivotal comparative studies between intact CPPW1 and its deglycosylated backbone (CPPW1B), revealing critical structure-function relationships. While both compounds showed antitumor effects in H22-bearing mice (56.73% vs 36.33% inhibition at 100 mg/kg), only CPPW1 exhibited significant immunostimulatory properties: enhancing T/B-cell proliferation (40-60% increase), boosting macrophage phagocytosis, and elevating NO production to LPS-comparable levels. These findings demonstrated that sugar side chains are essential for CPPs' dual functionality as both direct antitumor agents and immune potentiators, providing a rationale for structure-based optimization of anticancer polysaccharides [

31]. Yang et al. (2013) isolated and characterized CPP1b, a pectic polysaccharide with a unique structural composition of rhamnose, arabinose, galactose, and galacturonic acid (0.25:0.12:0.13:2.51 molar ratio). This 1.45 × 10⁵ Da molecule features a backbone of 1,4-linked α-d-GalpA (46.7% methyl-esterified) with distinctive 1,2-linked α-l-Rhap and 1,2,6-linked β-d-Galp branches, adopting an ovoid morphology. The polysaccharide demonstrated significant dose- and time-dependent cytotoxicity against A549 lung cancer cells, with its high galacturonic acid content potentially driving this antitumor activity. Notably, CPP1b showed synergistic effects with methotrexate, enhancing cancer cell inhibition [

32]. Chen et al. (2015) subsequently developed a selenized derivative (sCPP1b) that exhibited superior anticancer properties across multiple cell lines (A549, BGC-823, HeLa) at low concentrations (25-400 μg/mL), while maintaining selectivity against normal cells. The modified compound demonstrated enhanced apoptotic induction, greater migration inhibition, more effective G2/M phase arrest (29.81% vs 44.02%), and higher apoptosis rates (11.01% vs 8.14%) compared to the native polysaccharide. Both compounds activated the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway through Bax upregulation, Bcl-2 downregulation, and caspase-3 cleavage, with sCPP1b showing consistently stronger effects [

33].

Zhang et al (2016) conducted the most extensive structure-activity evaluating 26 CPPs from diverse regions. Their hierarchical clustering and PLS regression identified galacturonic acid as the most significant positive contributor to HepG2 cytotoxicity, followed by arabinose, rhamnose, galactose, and fructose. This systematic approach established quantitative structure-activity relationships and provided a framework for quality control and targeted optimization of anticancer CPPs [

34]. Bai et al. (2018) provided compelling evidence supporting the antitumor capabilities of CPPs through their meticulous investigation of two water-soluble fractions, CPP1a and CPP1c. Their comprehensive structural elucidation revealed CPP1a as a complex branched macromolecule (molecular weight 1.01×10⁵ Da) featuring an intricate arrangement of β-l-rhamnopyranosyl-(1

→4), β-arabinopyranosyl-(1

→5), β-d-galactopyranosyluronic acid-(1

→4), β-d-galactopyranosyl-(1

→6), and terminal β-d-glucopyranosyl residues in a distinctive 1:12:1:10:3 molar ratio. Both polysaccharide fractions displayed remarkable cancer cell selectivity, exhibiting particularly potent activity against HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma cells relative to cervical (HeLa) and gastric (MKN45) cancer cell lines. The researchers documented multiple anticancer mechanisms, including induction of characteristic morphological changes in cancer cells, substantial suppression of cellular migration, and effective blockade of the cell cycle at the G2/M checkpoint. Detailed mechanistic investigations uncovered that these polysaccharides trigger programmed cell death through modulation of the Bax/Bcl-2 apoptotic pathway and subsequent activation of caspase-3. Of particular significance, CPP1c demonstrated superior biological activity compared to CPP1a, a phenomenon the research team correlated with its elevated uronic acid content. This critical observation reinforces the emerging paradigm that acidic functional groups significantly contribute to the antitumor efficacy of plant-derived polysaccharides, providing valuable insights for future structure-activity relationship studies and the rational design of polysaccharide-based anticancer therapeutics [

35].

Liu et al. (2021) uncovered the potent anticancer activity of digested CPP (dCPP) against melanoma through its unique ability to reprogram tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). The purified dCPP, composed predominantly of mannose (97.2%), exhibited remarkable immunomodulatory properties by suppressing pro-tumorigenic M2-type TAMs while dramatically upregulating M1-polarized macrophages—evidenced by a striking 218-fold increase in IL-1β expression and elevated levels of other M1 markers (IL-6, iNOS, TNF-α). This macrophage repolarization was further confirmed by reduced expression of M2-associated markers (Arg1/Mrc1). In vivo studies demonstrated that combining crude CPCP (

C. pilosula crude polysaccharide fraction) with Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharides reduced melanoma tumor volumes by 49.2% and decreased CD68+ macrophage infiltration. Structural analysis revealed dCPP as an acidic polysaccharide with β-glycosidic linkages and a flexible, non-helical conformation, highlighting its potential as a dual-function immunotherapeutic agent capable of simultaneously inhibiting tumor-supportive M2 macrophages and activating antitumor M1 macrophages through cytokine regulation [

36]. Li et al. (2023) further advanced this field by systematically evaluating the impact of MW on the antitumor efficacy of CPPs. By fractionating the polysaccharides into three distinct groups (CPPS-I: <60 kDa, CPPS-II: 60-100 kDa, CPPS-III: >100 kDa), they identified CPPS-II as the most biologically active, demonstrating superior antitumor effects both in vitro and in vivo. Notably, CPPS-II at 125 μg/mL achieved tumor inhibition comparable to 10 μg/mL doxorubicin while also enhancing macrophage activation and nitric oxide production. In vivo, CPPS-II not only increased the M1/M2 macrophage ratio but also synergized with doxorubicin, outperforming the chemotherapy drug alone. CPPS-II as a highly promising therapeutic candidate, with its optimal activity attributed to its intermediate MW (60-100 kDa), which effectively balances immune modulation and direct antitumor effects. This study emphasizes the critical role of MW standardization in developing polysaccharide-based anticancer therapies and adjuvants [

37].

Wang et al. (2024) demonstrated the remarkable dual regulatory effects of CPP on precancerous gastric lesions through comprehensive preclinical studies. Their research revealed CPP's unique bifunctional mechanism: in hypoxia-stressed GES-1 cells, it activated the Wnt/β-catenin pathway (up to 32.3% increase in Wnt-1, β-catenin, and TCF-4), while in malignant AGS cells, it suppressed the same pathway (40.8% reduction in key markers) and inhibited proliferation by 27.2%. In PLGC rat models, CPP administration (110-440 mg/kg) produced multifaceted protective effects, including gastric mucosa repair, weight normalization, improved serum biomarkers (PGI, G17), oxidative stress reduction (enhanced SOD/GSH-Px, decreased MDA), and inflammation control (lowered IL-1β, TNF-α). The polysaccharide significantly promoted precancerous cell apoptosis through Bax/Bcl-2 ratio modulation (49.8% decrease) and caspase-3 activation (46.3% increase). Metabolomic analysis identified 20 significantly altered metabolites, connecting CPP's efficacy to glycine/serine/threonine metabolism pathways [

38].

Huang et al. (2024) elucidated the potent anticancer mechanisms of CPP against NSCLC through sophisticated in vitro and in vivo investigations. Their work established that CPP induces NLRP3/GSDMD-mediated pyroptosis in A549 cells, characterized by: (1) significant upregulation of pyroptotic proteins (NLRP3, ASC, GSDMD, caspase-1), (2) classical cell swelling and membrane rupture morphology, and (3) substantial release of IL-1β, IL-18 and LDH (p<0.05). The polysaccharide exhibited concentration-dependent efficacy, with optimal tumor growth inhibition at 40 μmol/L and maximal apoptosis induction at 20 μmol/L. Mechanistic studies revealed CPP's activation of the NF-κB pathway (increased p-NF-κB p65/p65 ratio) and ROS accumulation as key drivers of its anticancer effects. In xenograft models, CPP treatment significantly reduced tumor volume/weight (p<0.05) while enhancing both apoptosis (TUNEL-positive cells) and pyroptosis markers in tumor tissues. These findings demonstrate CPP's dual therapeutic action: direct cancer cell elimination through pyroptosis induction and tumor microenvironment modulation via inflammatory cytokine regulation, offering new possibilities for NSCLC treatment through innate immune activation and inflammatory cell death pathways [

39]. All these studies demonstrate CPPs as versatile anticancer agents with multi-target mechanisms, including direct cytotoxicity, immunomodulation, and metabolic regulation (

Table 2). Their structural diversity enables specific bioactivities, while chemical modifications like selenization further enhance therapeutic potential.

2.3. Antioxidant Activities of CPPs

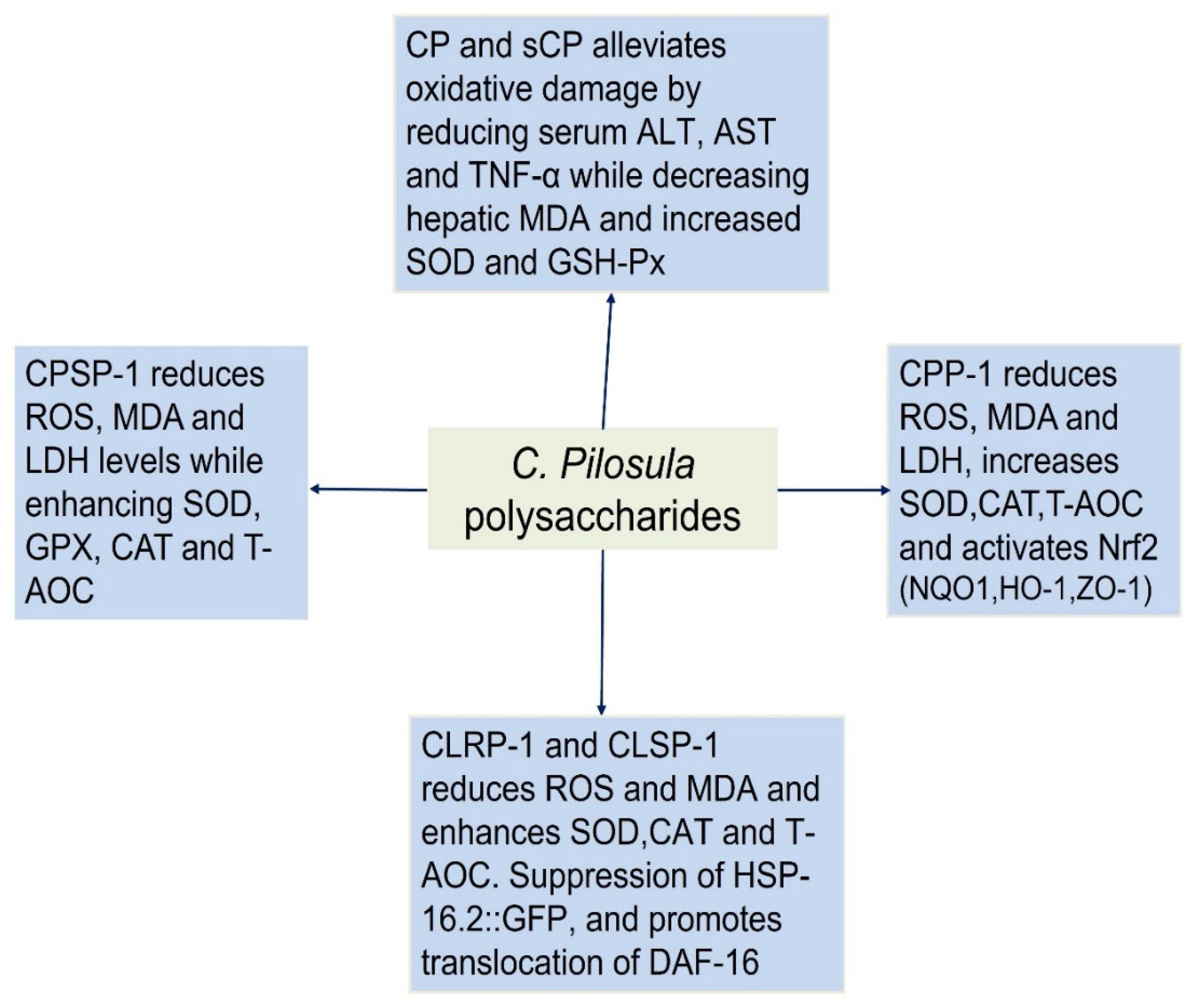

CPPs exhibit remarkable antioxidant properties, with structural variations influencing their bioactivity. Factors such as MW, monosaccharide composition, and chemical modifications (e.g., sulfation) significantly enhance their free radical scavenging and cellular protective effects. These findings position CPPs as promising natural antioxidants for combating oxidative stress-related diseases. Zou et al. (2020) reported that CPSP-1, a pectic polysaccharide with a MW of 13.1 kDa, consists primarily of homogalacturonan (HG) and rhamnogalacturonan-I (RG-I) regions, with arabinogalactan type II (AG-II) side chains. The monosaccharide composition revealed high galacturonic acid (GalA) content (70.1 mol%), along with smaller proportions of arabinose (Ara, 8.9 mol%), rhamnose (Rha, 9.3 mol%), and galactose (Gal, 11.0 mol%). CPSP-1 demonstrated significant antioxidant activity in intestinal porcine epithelial cells (IPEC-J2), effectively mitigating oxidative stress induced by H₂O₂. It reduced ROS, MDA, and LDH levels while enhancing T-AOC and the activity of key antioxidant enzymes such as SOD, GPX, and CAT. Notably, CPSP-1 upregulated the expression of antioxidant genes (GPXs, SOD1, CAT) without activating the Nrf2 signaling pathway, suggesting an alternative mechanism for its protective effects. Additionally, it restored the expression of the tight junction protein ZO-1, highlighting its role in preserving intestinal barrier integrity. The study attributed CPSP-1’s potent bioactivity to its lower MW and specific structural features, such as shorter AG-II chains, which may facilitate stronger interactions with cellular antioxidant systems. These findings underscore CPSP-1’s potential as a therapeutic agent for oxidative stress-related intestinal disorders [

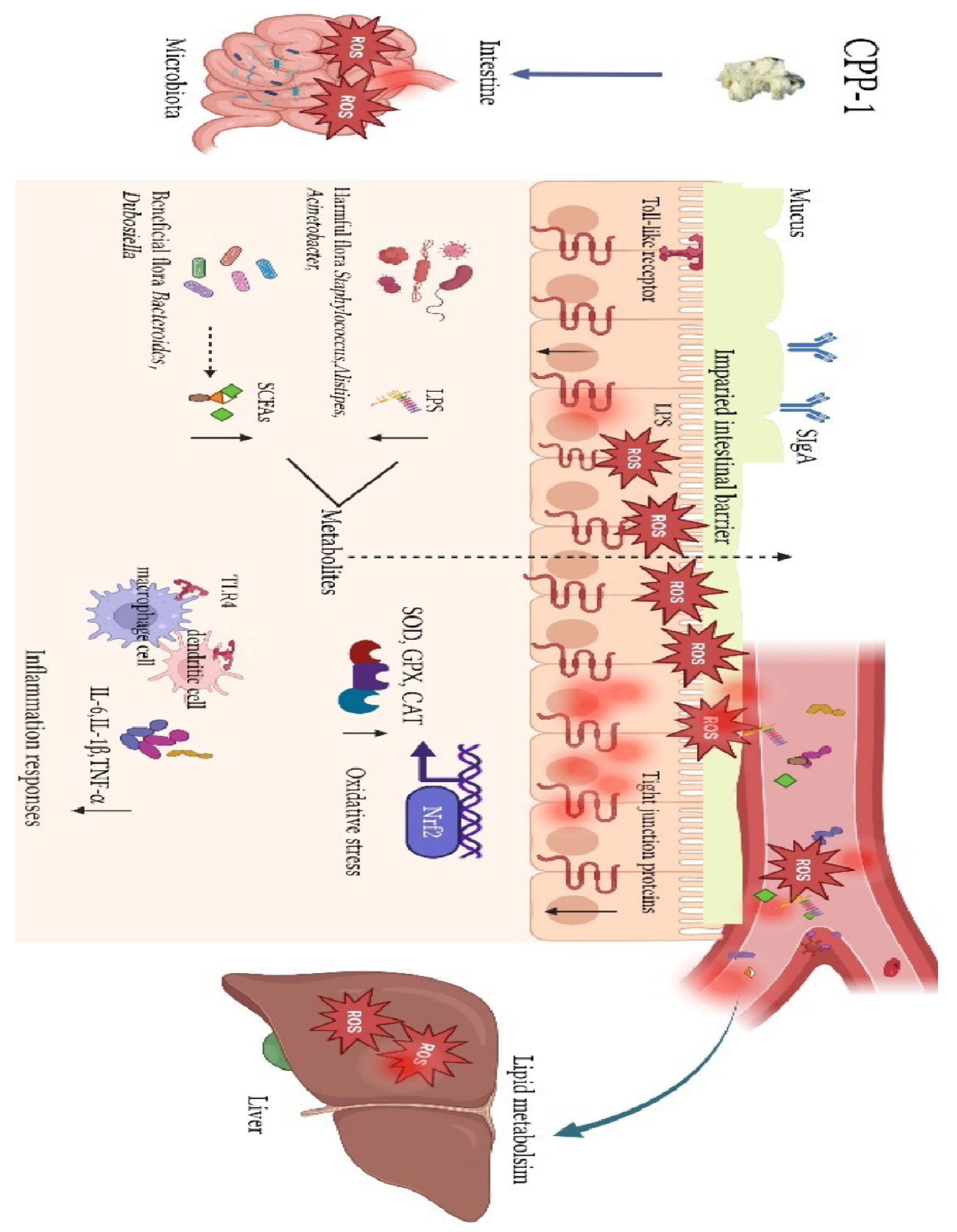

15]. In another study, Zou et al. (2021) isolated CPP-1, a pectic polysaccharide, using boiling water extraction and chromatography. With a MW of 21.0 kDa, CPP-1 comprised arabinose (16.7%), rhamnose (9.4%), galactose (12.8%), galacturonic acid (58.9%), and traces of fucose/mannose. Structurally, it featured a long homogalacturonan (HG) backbone with rhamnogalacturonan I (RG-I) side chains, methyl-esterified GalA units, and shorter HG regions. The antioxidant activity of CPP-1 was evaluated using IPEC-J2 cells, a model for intestinal oxidative stress. CPP-1 significantly mitigated H2O2-induced oxidative damage by enhancing cell viability and T-AOC. It reduced oxidative stress markers, including ROS, MDA, and LDH, while upregulating antioxidant enzymes like CAT. CPP-1 demonstrated superior efficacy in boosting T-AOC and reducing MDA levels, likely due to its lower MW, higher Ara/Gal content, and shorter AG-I side chains. Mechanistically, CPP-1 activated the Nrf2 pathway, increasing the expression of antioxidant genes (NQO1, HO-1) and tight junction proteins (ZO-1). These findings highlight CPP-1 as a promising natural antioxidant for intestinal health applications, with its bioactivity strongly linked to its unique structural features [

40]. Further studies by Zou et al. (2023), CPP-1 demonstrated potent antioxidant activity in the gut of naturally aging mice, primarily targeting the jejunum where its effects were most pronounced. At the gene level, CPP-1 significantly upregulated the expression of key antioxidant enzymes, including SOD, GPX, and CAT, as well as the transcription factor Nrf2, a master regulator of cellular antioxidant responses. This upregulation was particularly evident in the duodenum and jejunum, with high-dose CPP-1 treatment showing the most robust enhancement of these markers. In contrast, the ileum exhibited a more limited response, with only CAT and GPX gene expressions being significantly elevated. At the protein level, CPP-1 further confirmed its antioxidant potential by increasing the activity of SOD, CAT, and T-AOC in the jejunum while simultaneously reducing ROS levels [

41].

Two acidic polysaccharides, CLRP-1 (isolated from roots) and CLSP-1 (isolated from aerial parts) exhibited significant antioxidant properties in both in vitro and in vivo models. CLRP-1 had a MW of 15.9 kDa and consisted of arabinose, rhamnose, fucose, xylose, mannose, galactose, glucuronic acid (GlcA), and galacturonic acid (GalA) in a molar ratio of 3.8:8.4:1.0:0.8:2.4:7.4:7.5:66.7. In contrast, CLSP-1 had a higher molecular weight of 26.4 kDa and a simpler monosaccharide composition, consisting of Ara, Rha, Gal, and GalA in a ratio of 5.8:8.9:8.0:77.0. Similar to CLRP-1, CLSP-1 was also classified as a pectic polysaccharide but possessed a longer HG backbone and shorter arabinogalactan side chains compared to CLRP-1. Both polysaccharides demonstrated potent antioxidant effects in various experimental models. In IPEC-J2 cells, a porcine intestinal epithelial cell line used to study intestinal antioxidant defense, CLRP-1 and CLSP-1 significantly increased cell viability under H₂O₂-induced oxidative stress. They enhanced T-AOC and elevated the activities of key antioxidant enzymes, including SOD and CAT, while simultaneously reducing MDA levels, a well-established marker of lipid peroxidation. Notably, CLRP-1 exhibited superior antioxidant activity compared to CLSP-1, likely due to its lower MW and shorter HG backbone, which may facilitate better bioactivity. Further validation of their antioxidant potential was conducted in Caenorhabditis elegans, a widely used model organism for oxidative stress and aging studies. Both polysaccharides effectively reduced ROS and MDA levels while increasing SOD, CAT, and T-AOC in a dose-dependent manner. Additionally, they suppressed the expression of HSP-16.2::GFP, a stress-responsive protein, indicating enhanced resistance to oxidative and thermal stress. Moreover, CLRP-1 and CLSP-1 promoted the nuclear translocation of DAF-16, a transcription factor that regulates the expression of antioxidant genes such as sod-3, further confirming their role in enhancing cellular antioxidant defenses [

42].

In the study by Lu et al. (2023), a novel α-1,6-glucan polysaccharide (CPP 2-4) with a high MW of 3.9×10⁴ kDa was successfully extracted using an optimized aqueous two-phase system (ATPS) method, achieving an impressive extraction yield of 31.57%. This polysaccharide demonstrated significant antioxidant activity, as evidenced by its strong DPPH radical scavenging capacity (IC50 = 0.105 mg/mL) and dose-dependent responses in both FRAP and ABTS assays, indicating potent reducing power and free radical neutralization capabilities. Interestingly, despite its high MW- which typically correlates with reduced bioactivity, CPP 2-4 exhibited remarkable antioxidant performance, challenging conventional structure-activity assumptions. Furthermore, the polysaccharide showed promising anti-inflammatory effects by significantly inhibiting NO production in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages, suggesting its potential to mitigate oxidative stress-related inflammatory responses. This study not only introduced an efficient ATPS extraction method but also identified a unique glucan structure in C. pilosula, expanding our understanding of this plant's polysaccharide composition and its potential applications in functional foods and therapeutics targeting oxidative stress and inflammation [

43]

Sulfation modification was shown to significantly enhance the antioxidant properties of CPPs (CP), with the sulfated derivative (sCP) demonstrating superior free radical scavenging capacity in vitro compared to native CP. This improved antioxidant activity was further validated in vivo using a BCG/LPS-induced hepatic injury mouse model, where sCP administration at 150-200 mg/kg doses effectively protected against oxidative liver damage by significantly reducing serum ALT, AST and TNF-α levels while decreasing hepatic MDA content - a key marker of lipid peroxidation. sCP also showed remarkable ability to restore hepatic antioxidant defenses, as evidenced by significantly increased SOD and GSH-Px activities in liver homogenates compared to both the injury model group and mice treated with unmodified CP at equivalent doses. Histopathological examination confirmed these biochemical findings, with sCP-treated groups exhibiting near-normal liver architecture while the model group showed severe pathological changes. The study clearly demonstrated that sulfation modification potentiates the inherent antioxidant capacity of CP, with sCP outperforming its native counterpart in both radical scavenging assays and hepatoprotective efficacy. These findings highlight the potential of chemical modification strategies to enhance the therapeutic value of plant polysaccharides, particularly for combating oxidative stress-related disorders. The superior performance of sCP in restoring antioxidant enzyme activities and mitigating oxidative damage markers suggests its promise as a hepatoprotective agent, while also providing insights into structure-activity relationships that could guide development of more effective polysaccharide-based antioxidants [

17]. CPPs, particularly pectic and sulfated variants, exhibit potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects across in vitro and in vivo models. Their bioactivity is closely tied to structural features like molecular weight, monosaccharide composition, and chemical modifications. Future research should explore clinical applications, optimizing CPP formulations for targeted oxidative stress mitigation. Antioxidant activities of various CPPs through different mechanisms were represented in

Figure 2.

2.4. Neuroprotective Effects of CPs

Emerging research highlights CPPs as promising neuroprotective agents against Alzheimer's disease (AD) pathology. Studies demonstrate CPPs' ability to target multiple AD hallmarks, including Aβ aggregation, tau hyperphosphorylation, oxidative stress, and synaptic dysfunction. Zhang et al (2018) demonstrated that CPPs significantly alleviate tau pathology in AD models. Their research showed CPPs reduce tau hyperphosphorylation by activating protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) without altering its expression levels. In cellular studies, CPPs (50-200 μg/ml) increased PP2A activity by 30-50%, decreasing phosphorylation at critical tau sites (Ser199, Ser202/Thr205). These effects were confirmed in tau-overexpressing mice, where 300 mg/kg CPPs enhanced hippocampal PP2A activity by 35% while reducing pathological tau phosphorylation by 40-50%. The treatment also reversed cognitive deficits, improving memory test performance 2.5-fold and restoring synaptic plasticity by 80%. Structural analysis revealed CPPs maintained dendritic spine density and boosted synaptic protein levels (synaptotagmin and synaptophysin) by 1.8-2.2 fold. While PP2A activation appears central to CPPs' mechanism, the precise molecular interactions require further investigation. Notably, these neuroprotective effects were dose-dependent, with 100 mg/kg CPPs showing minimal impact [

44].

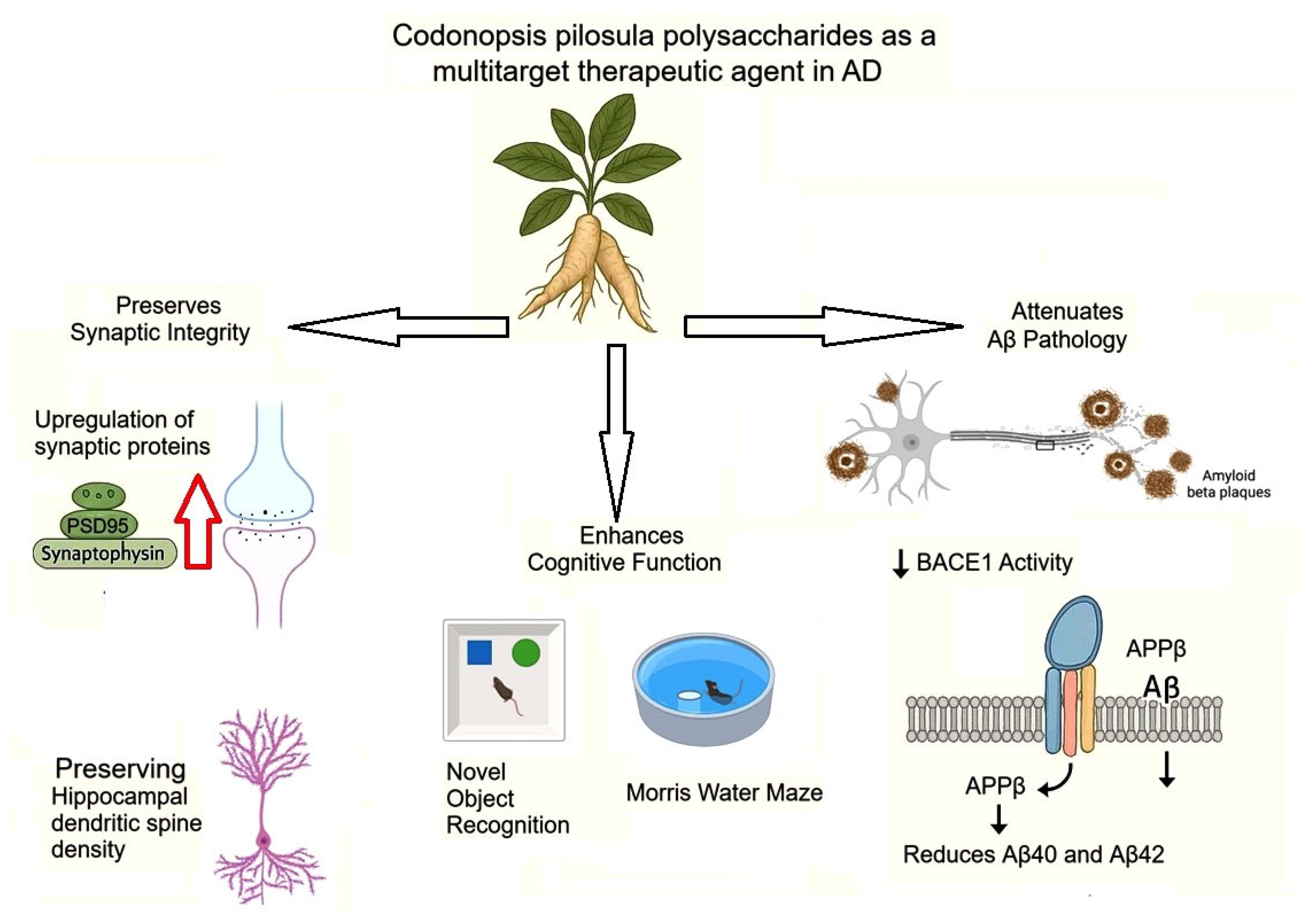

Wan et al (2020) demonstrated that CPPs exert significant neuroprotective effects in APP/PS1 transgenic mice, a model of Alzheimer's disease (AD), by reducing Aβ accumulation and improving cognitive function. Their study revealed that one-month intragastric administration of CPPs (100-300 mg/kg) rescued memory deficits in APP/PS1 mice, as evidenced by improved performance in the Novel Object Recognition (NOR) and Morris Water Maze (MWM) tests. Notably, CPPs restored synaptic plasticity by increasing key synaptic proteins (PSD95 and synaptotagmin) and preserving dendritic spine density in the hippocampus. Mechanistically, CPPs significantly reduced Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels in APP/PS1 mice by suppressing β-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1) activity, the rate-limiting enzyme in Aβ production. Western blot analysis confirmed decreased APPβ fragments and BACE1 activity in CPP-treated mice. These findings were corroborated in vitro, where CPPs (200 μg/mL) reduced Aβ42 secretion in N2a-APP and HEK293-APP cells without affecting cell viability. Strikingly, CPPs directly inhibited recombinant human BACE1 activity at higher concentrations (500-1000 μg/mL), suggesting a specific interaction with the enzyme. Furthermore, CPPs alleviated Aβ-induced synaptotoxicity in primary neurons, upregulating synaptophysin and PSD95 expression. The study highlights CPPs as a multitarget therapeutic agent that: (1) enhances cognitive function, (2) preserves synaptic integrity, and (3) attenuates Aβ pathology through BACE1 inhibition (

Figure 3) [

45].

Hu et al (2021) investigated the neuroprotective effects of CPPs against Aβ1-40-induced toxicity in PC12 cells, a model for early AD. Their study demonstrated that CPPs counteract Aβ1-40-induced damage by restoring energy metabolism, reducing oxidative stress, and modulating NAD+ homeostasis. Aβ1-40 exposure decreased cell viability, ATP levels, and the NAD+/NADH ratio while increasing ROS and mitochondrial dysfunction. However, CPP treatment reversed these effects by enhancing mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) and boosting NAD+ levels, which are critical for cellular energy balance. A key mechanism identified was the downregulation of CD38, an NAD+-degrading enzyme upregulated by Aβ1-40. By suppressing CD38, CPPs preserved NAD+ levels and activated SIRT1 and SIRT3, NAD+-dependent deacetylases essential for mitochondrial function and antioxidant defense. Additionally, CPPs restored PGC-1α expression, a regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis. Notably, when CD38 was silenced using siRNA, CPPs no longer provided additional protection, confirming that their neuroprotective effects depend on CD38 inhibition. These findings suggest that CPPs mitigate Aβ1-40-induced neuronal damage by targeting NAD+ metabolism and mitochondrial function, positioning them as a potential therapeutic intervention for early AD [

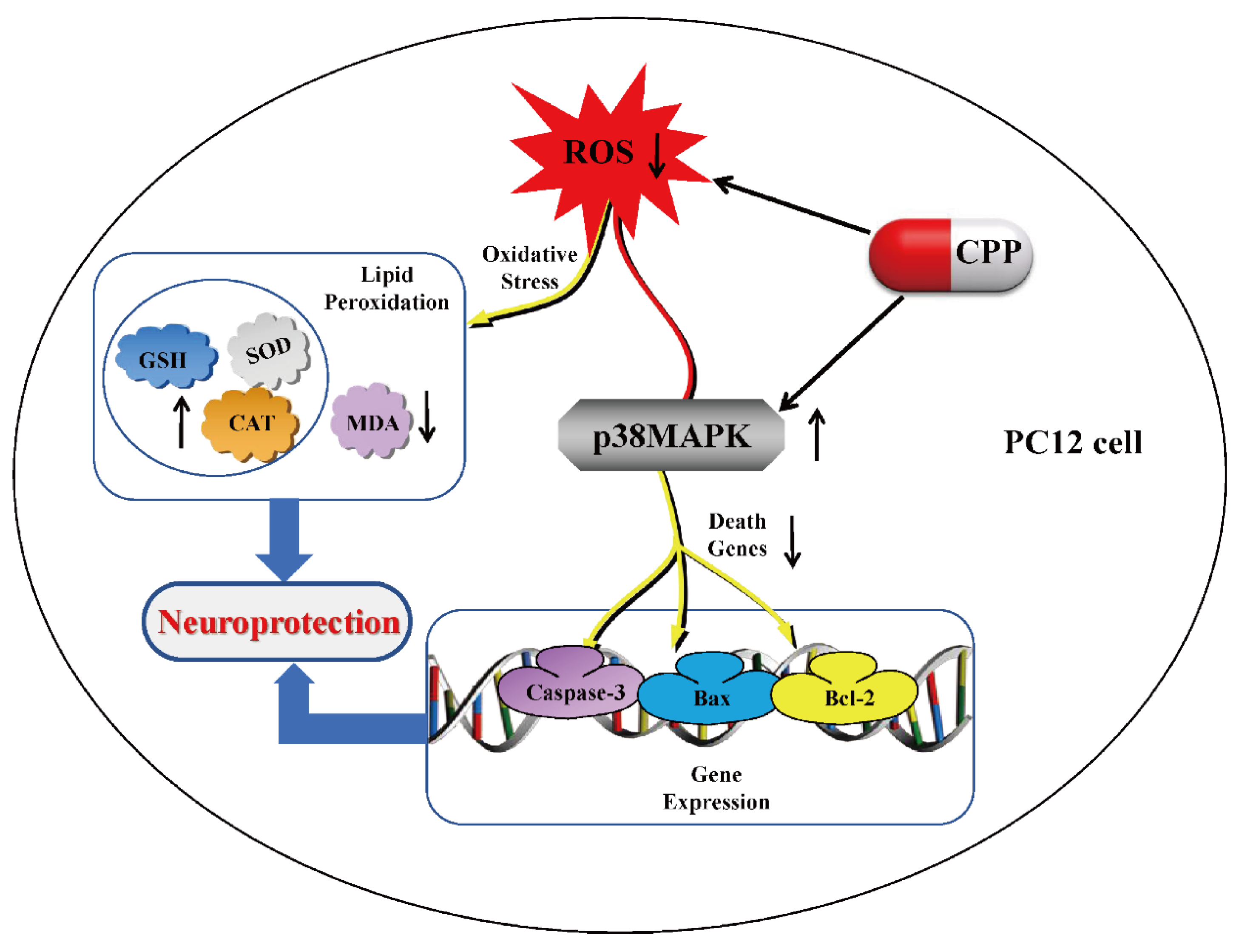

46]. Further Yang et al (2024) explored the neuroprotective role of Codonopsis pilosula polysaccharide (CPP) in Aβ25-35-induced PC12 cells, a model for Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Their study demonstrated that CPP (1 μmol/L) significantly restored cell viability, reduced oxidative stress, and inhibited apoptosis triggered by Aβ25-35. CPP treatment reversed Aβ25-35-induced cytotoxicity, as evidenced by improved cell morphology and increased synapse integrity. Mechanistically, CPP attenuated oxidative damage by lowering ROS and MDA levels while enhancing antioxidant defenses (SOD, GSH, CAT). Furthermore, CPP reduced apoptosis by downregulating pro-apoptotic factors (Bax, caspase-3) and upregulating anti-apoptotic Bcl-2. A key finding was that CPP’s protective effects were mediated via the p38MAPK pathway, as inhibition of p38MAPK abolished CPP’s anti-apoptotic and antioxidant benefits (

Figure 4). These results suggest CPP mitigates Aβ25-35-induced neuronal damage by modulating oxidative stress and apoptosis through p38MAPK signaling [

47]

2.5. Hepatoprotective and Renal Protective Effects of CPPs

CPPs, particularly the purified neutral polysaccharide CPP-1, exhibit significant hepatoprotective effects through multiple mechanisms. CPP-1 is a homogeneous polysaccharide with a molecular weight of 4.89 × 10³ Da, primarily composed of fructose and glucose residues with a small amount of arabinose. Structural analysis revealed its unique configuration featuring α-D-Glcp-(1

→[2)-β-D-Fruf-(1

→2)-β-D-Fruf-(1]₃

→2)-β-D-Fruf linkages, which likely contributes to its biological activity. In vitro studies using AML12 hepatocyte injury models demonstrated CPP-1's ability to enhance cell viability while reducing oxidative damage. The polysaccharide significantly decreased MDA levels and boosted the activity of key antioxidant enzymes including SOD, CAT, and GSH. The hepatoprotective effects were further confirmed in a high-fat diet (HFD)-induced NAFLD mouse model. CPP-1 administration effectively reduced obesity-related parameters including body weight, liver index, and body fat index. Treatment with CPP-1 improved lipid metabolism by significantly lowering serum levels of total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), and LDL-cholesterol while increasing HDL-cholesterol. Liver function tests showed reduced ALT and AST levels, indicating improved hepatocyte integrity. Histopathological examination revealed CPP-1's ability to decrease hepatic steatosis, with treated animals showing reduced lipid droplet accumulation and better preservation of liver architecture compared to untreated controls [

48].

Meng et al (2023) demonstrated that CPP-A-1 exhibits significant hepatoprotective effects against liver fibrosis through multiple mechanisms. Their study characterized CPP-A-1 as a homogeneous polysaccharide (MW 9424 Da) with a backbone of

→(2-β-D-Fruf-1)n

→ and showed its potent antifibrotic activity in both cellular and animal models. In TGF-β1-activated LX-2 hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), CPP-A-1 (50-200 μg/mL) dose-dependently inhibited proliferation and induced apoptosis, while in CCl₄-induced fibrotic mice, it reduced collagen deposition, serum ALT/AST levels, and expression of fibrotic markers (collagen I, α-SMA). CPP-A-1 restored the MMP/TIMP balance to prevent excessive ECM accumulation and enhanced antioxidant defenses by increasing SOD, GSH, and Mn-SOD while decreasing MDA and iNOS levels. The polysaccharide also exhibited strong anti-inflammatory effects by suppressing TNF-α and IL-6 production. Mechanistically, CPP-A-1 targeted two key fibrotic pathways - it downregulated TLR4/NF-κB signaling (reducing TLR4, MyD88, and NF-κBp65) and inhibited TGF-β1/Smad3 activation (decreasing TGF-β1, Smad3, and p-Smad3), with effects comparable to specific pathway inhibitors TAK-242 and LY2157299. These multi-target actions collectively contributed to CPP-A-1's ability to attenuate HSC activation and liver fibrosis progression. The study highlights CPP-A-1 as a promising natural therapeutic candidate for liver fibrosis, with advantages including its ability to simultaneously address oxidative stress, inflammation, and ECM remodeling through modulation of critical signaling pathways, while maintaining a favourable safety profile as a plant-derived compound [

49]. The study by Liu et al. (2015) investigated the hepatoprotective effects of

C. pilosula polysaccharide (CP) and its sulfated derivative (sCP) in a BCG/LPS-induced liver injury mouse model. Both CP and sCP demonstrated protective effects, but sulfation modification significantly enhanced the bioactivity of the polysaccharide. In serum biochemical analysis, the model control group exhibited elevated levels of ALT, AST, ALP, and TNF-α, along with reduced total protein (TP), indicating severe liver damage. Treatment with sCP, particularly at higher doses (150 and 200 mg/kg), effectively normalized these markers, outperforming native CP in reducing liver enzyme levels and suppressing pro-inflammatory TNF-α. Additionally, sCP exhibited superior antioxidative activity in liver tissue, as evidenced by increased SOD and GSH-Px activities and decreased MDA levels compared to CP-treated groups. Histopathological examination further confirmed the enhanced protective effect of sCP, showing near-normal liver architecture with minimal inflammation and necrosis, whereas CP-treated livers still exhibited some inflammatory infiltration. Their findings suggest that both CP and sCP possess hepatoprotective properties through antioxidative and anti-inflammatory mechanisms, but sulfation modification significantly amplifies these effects, making sCP a more potent therapeutic candidate for liver injury [

17]. Nie et al. (2024) investigated the hepatoprotective effects of CPP against sterigmatocystin (STC)-induced liver injury, with a particular focus on its role in modulating gut microbiota. The study revealed that CPP intervention significantly mitigated STC-induced liver injury, as evidenced by reduced liver index, improved histopathological changes, and the regulation of key molecular markers. CPP exerted its protective effects by suppressing liver inflammation and oxidative stress, inhibiting hepatocyte apoptosis, and restoring lipid metabolism. Notably, CPP also reversed STC-induced gut microbiota dysbiosis by enhancing microbial diversity and richness, suggesting that gut microbiota modulation plays a critical role in CPP-mediated liver protection [

50].

Li et al (2012) reported that the polysaccharide S-CPPA1 demonstrates significant renal protective effects against ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury. This homogeneous polysaccharide with a molecular weight of 133.2 kDa exhibits a unique branched structure composed primarily of glucose, galactose, and arabinose in a molar ratio of 10.5:3.4:1.7, along with trace amounts of mannose. Structural analysis reveals five characteristic glycosidic linkages: (1

→4)-linked Glcp, (1

→6)-linked Galp, (1

→2,6)-linked Glcp (serving as branching points), (1

→5)-linked Araf, and terminal (1

→)-linked Glcp. In experimental models of renal I/R injury, S-CPPA1 administration effectively ameliorated kidney damage by significantly reducing elevated levels of blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, and the inflammatory cytokine TNF-α, while also normalizing the activities of LDH and AST. Histopathological examination confirmed its protective effects, showing attenuation of tubular necrosis, interstitial edema, and inflammatory infiltration. The unique structural features of S-CPPA1, especially its branched configuration with (1

→2,6)-linked glucopyranose residues, likely contribute to its biological activity, making it a promising candidate for further investigation in renal protection therapies [

51].

2.6. Antidiabetic Activity of CPPs

Liu et al. (2018) reported CERP1, a neutral heteropolysaccharide of

C. pilosula, exhibits significant hypoglycemic and antidiabetic effects through multiple mechanisms, as demonstrated in both in vitro and in vivo studies. In vitro experiments revealed that CERP1 (0.2–0.8 mg/mL) dose-dependently improved the viability of streptozotocin (STZ)-damaged INS-1 pancreatic β-cells and enhanced insulin secretion, suggesting a protective effect on β-cell function. In vivo studies using HFD/STZ-induced type 2 diabetic mice, oral administration of CERP1 (150–600 mg/kg for 28 days) significantly reduced fasting blood glucose levels, improved insulin sensitivity, and ameliorated oxidative stress by lowering MDA levels while boosting antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT, GSH-Px, and T-AOC). Additionally, CERP1 improved lipid metabolism by reducing TG, TC, and LDL/HDL ratios, while also enhancing hepatic function through decreased liver transaminase activity. Its structural composition—primarily 1-linked, 1,3-linked, and 1,6-linked β-D-glucose, along with 1,3,6-linked β-D-galactose—and low MW (4.84 kDa) contribute to its high bioactivity [

52].

Yang et al. (2023) investigated the antidiabetic effects of ultrasonically extracted

C. pilosula crude polysaccharides (CPCPs) in a T2DM mouse model induced by high-fat/high-glucose diet and STZ injection. Structural analysis revealed CPCPs as β-type pyranose polysaccharides containing uronic acids and sulfate groups, exhibiting a porous, fibrillar morphology. CPCPs demonstrated significant α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity, suggesting direct carbohydrate-digestion modulation. In diabetic mice, 1 g/kg CPCPs (CLD group) exerted multifaceted therapeutic effects: substantially lowering fasting blood glucose (38.6% reduction), improving lipid profile (reducing TG and LDL-C while increasing HDL-C), and protecting pancreatic β-cell function as evidenced by improved organ indices. The polysaccharides significantly ameliorated oxidative stress by enhancing hepatic, renal and pancreatic antioxidant defenses (35.74% increase in SOD, restored GSH-Px and CAT activities) while reducing lipid peroxidation (LPO) and MDA levels. CPCPs also exhibited potent anti-inflammatory effects, markedly suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, and NF-κB). Histopathological evaluation confirmed hepatoprotective and nephroprotective properties, with CPCPs-treated groups showing preserved tissue architecture. Notably, CPCPs modulated gut microbiota composition by correcting the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio imbalance characteristic of diabetes, specifically reducing Enterobacter while increasing Bacteroides abundance - suggesting microbiome-mediated mechanisms. The combined enzymatic inhibition, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and prebiotic activities position CPCPs as a multifunctional antidiabetic agent with potential for managing T2DM and its complications through both direct metabolic effects and indirect microbiota modulation [

53].

Yang et al (2024) further purified six polysaccharide fractions (WCP1, WCP2, WCP3, WCP4, WCP5 and WCP6) from C. pilosula. Among six purified fractions (WCP1-WCP6), WCP5 demonstrated the most potent inhibition against both α-amylase (IC50 = 3.712 mg/mL) and α-glucosidase (IC50 = 2.962 mg/mL). Molecular docking studies revealed WCP5's mechanism involves forming multiple hydrogen bonds with key amino acid residues in the enzymes' active sites, thereby competitively inhibiting their activity. Additionally, certain fractions (particularly WCP4) exhibited significant free radical scavenging capacity, suggesting these polysaccharides may simultaneously address hyperglycemia and oxidative stress - two critical aspects of diabetes pathophysiology [

54].

In a recent study, wang et al. (2025) demonstrated that ultrasound assistance extracted C. pilosula polysaccharides (UA-Cpps3/5) exhibit notable antidiabetic potential through dual antioxidant and enzyme-inhibitory mechanisms. These polysaccharides showed strong free radical-scavenging activity, alleviating oxidative stress linked to diabetes progression. Crucially, UA-Cpps3/5 significantly inhibited α-amylase and α-glucosidase, key enzymes in carbohydrate digestion, via hydrogen-bond interactions revealed by molecular docking. The 1

→4 glycosidic bonds in their structure were identified as critical for both antioxidant effects and enzyme suppression. This dual action—reducing oxidative damage while delaying glucose absorption—positions them as promising natural agents for diabetes management. Their ability to simultaneously target multiple diabetic pathways suggests potential as functional food ingredients or nutraceuticals for metabolic regulation [

55].

2.7. Antiviral and Antibacterial Effects of CPPs

Duck hepatitis A virus type 1 (DHAV) infection causes severe duck viral hepatitis, leading to significant economic losses in the poultry industry. Ming et al (2017) developed phosphorylated CPP (pCPPS) through STMP-STPP modification of native CPPS and confirmed its structural changes using IR spectroscopy and FE-SEM analysis. Comparative evaluation of antiviral activity revealed striking differences between the two compounds - while unmodified CPPS showed no inhibitory effect on DHAV, the phosphorylated derivative pCPPS demonstrated significant antiviral properties. In cell-based assays, pCPPS treatment increased survival rates of DHAV-infected duck embryonic hepatocytes and reduced viral infectivity as measured by TCID50. Real-time PCR analysis further confirmed pCPPS's ability to suppress viral replication, with the observed decrease in IFN-β expression serving as a molecular indicator of reduced viral load since DHAV normally upregulates this cytokine during infection. These findings collectively demonstrate that chemical phosphorylation markedly enhances the antiviral efficacy of CPP against DHAV, with pCPPS acting primarily through inhibition of viral replication rather than immunomodulation [

56]. Further studies by Ming et al (2020) reported that autophagosome formation is crucial for picornavirus replication, this study investigated the role of autophagy regulation in pCPPS-mediated antiviral activity using western blot, confocal microscopy, and ELISA assays in both in vitro and in vivo models. Results demonstrated that unmodified CPPS had no effect on autophagy regulation or therapeutic efficacy in infected ducklings. In contrast, pCPPS significantly downregulated LC3-II expression levels induced by DHAV and rapamycin, indicating suppression of autophagosome formation, which consequently inhibited viral genome replication. Further analysis revealed that pCPPS reduced phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PI3P) levels—a key membrane component required for autophagosome biogenesis—in cells and serum, thereby disrupting autophagy activation. In vivo experiments confirmed pCPPS's therapeutic potential, showing improved survival rates and reduced hepatic injury in infected ducklings. This study not only validate pCPPS as a promising anti-DHAV agent but also highlight how phosphorylation enhances the bioactivity of polysaccharides. By elucidating pCPPS's mechanism of action through autophagy inhibition, this study provides a foundation for developing novel antiviral therapies against DHAV and related pathogens [

57].

Liu et al (2015) demonstrate that combinations of Solomonseal polysaccharide (SP) and sulfated C. pilosula polysaccharide (sCP) exhibit potent synergistic activity against Newcastle disease virus (NDV). Among five tested combinations at varying ratios (9:1, 7:3, 6:4), SP9-sCP1 (9:1 ratio) showed the highest antiviral efficacy in vitro, with significantly elevated cell viability (A570 values) and a remarkable virus inhibition rate. Transmission electron microscopy revealed SP9-sCP1 directly disrupts NDV structure, causing envelope rupture within 30 minutes and complete viral degradation by 120 minutes. Immunofluorescence assays further confirmed its ability to suppress viral antigen expression, suggesting interference with viral attachment, replication, or assembly. In vivo validation in NDV-challenged chickens revealed SP9-sCP1’s superior therapeutic potential, yielding the lowest mortality (16.7%) and highest cure rate (83.3%) compared to controls. The 9:1 ratio proved critical, as higher sCP proportions (e.g., SP7-sCP3) diminished activity, highlighting that sulfation degree (DS) and sulfate group (SO₄²⁻) positioning—not merely concentration—dictate efficacy. SO₄²⁻ may sterically hinder viral-cell interactions or block intracellular replication. Structurally, SP’s β-1,4-linked galactopyranosyl backbone and sCP’s sulfated arabinogalactan components likely synergize to enhance antiviral targeting [

58].

Yuying and Erbing (2016) investigated the antibacterial properties of CPPs against Escherichia coli, comparing extracts from sulfur-fumigated herbs with desulfurized counterparts using the agar-well diffusion method, where they established optimal extraction conditions (45°C desulfurization temperature, 50 min processing time, 700 W ultrasonic power, and 10:1 ethanol-to-material ratio) that achieved a 55.4% desulfurization rate, and demonstrated that desulfurized CPPs exhibited superior antibacterial activity with a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 35 mg/mL compared to 70 mg/mL for sulfur-fumigated CPPs, indicating that sulfur fumigation diminishes while proper desulfurization enhances the polysaccharides' antibacterial efficacy, suggesting their potential as natural antimicrobial agents contingent on appropriate processing methods [

59].

2.8. Gastroprotective and Prebiotic Effects of CPPs

Emerging research highlights CPPs as potent modulators of gut microbiota and intestinal health, demonstrating dual prebiotic and gastroprotective properties. CPPs designated as CPN showed significant gastroprotective and prebiotic effects, particularly in colitis management. Studies reveal CPN's dual action in gut microbiota modulation: stimulating beneficial probiotics (Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, and Akkermansia) while suppressing pathogenic bacteria (Desulfovibrio, Alistipes, and Helicobacter). This selective modulation restores microbial balance, enhances short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production, and improves intestinal metabolic function. CPN further exerts anti-inflammatory effects by regulating cytokine secretion, promoting anti-inflammatory responses (via Th17/Treg balance), and inhibiting pro-inflammatory pathways. In DSS-induced colitis mice, CPN upregulated beneficial taxa like Blautia, Prevotellaceae UCG-001, and Oscillibacter, while downregulating inflammation-associated genera. These changes correlate with accelerated mucosal repair and enhanced gut barrier integrity. By fostering a probiotic-rich environment and mitigating dysbiosis, CPN polysaccharides emerge as promising natural therapeutics for gastrointestinal disorders, combining prebiotic efficacy with gastroprotective benefits [

60].

Zhou et al. (2025) examined the therapeutic potential of CPPS in treating dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced ulcerative colitis (UC) in mice. The study found that CPPS - composed of rhamnose, arabinose, galactose, glucose, and galacturonic acid - effectively alleviated UC symptoms by restoring gut microbiota balance. Treatment significantly increased the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio while boosting populations of beneficial bacteria including Ligilactobacillus, Akkermansia, Faecalibaculum, and Odoribacter. Additionally, CPPS enhanced production of SCFAs, especially acetic and butyric acids. The mechanism of action involved CPPS-mediated SCFAs activating G protein-coupled receptors which subsequently inhibited the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway, thereby reducing intestinal inflammation. Fecal microbiota transplantation experiments further confirmed that the gut microbiota modified by CPPS treatment alone could effectively mitigate UC symptoms [

61].

Chen (2016) demonstrated that CPPs exhibit significant prebiotic effects in DSS-induced UC mice by selectively modulating gut microbiota. Treatment with CPPs promoted the growth of probiotic genera, Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, Arthrobacter, and Akkermansia, which are known to enhance gut barrier function and immune regulation. Additionally, CPPs increased the abundance of SCFA producing bacteria such as Anaerovorax, Roseburia, Prevotella, Dialister, Faecalibacterium, Megamonas and Subdoligranulum, leading to elevated SCFA levels that support colonic health and reduce inflammation. Concurrently, CPPs inhibited pathogenic bacteria like Escherichia_Shigella, Bacteroides, and Coprococcus, which are associated with gut dysbiosis and inflammation. By restoring microbial balance and enhancing SCFA production, CPPs exerted gastroprotective effects, mitigating colitis severity, preserving intestinal mucosal integrity, and reducing inflammatory responses [

62].

Li et al (2021) demonstrated that CPP significantly stimulated the growth of beneficial Bifidobacterium (P < 0.05), a key probiotic genus known for its positive effects on gut health and immune function. While not statistically significant, CPP also showed modulatory trends toward other bacterial groups - exhibiting potential stimulation of Acidaminococcus and inhibitory effects on Bilophila, Dorea, and Eggerthella. CPP may function as a selective prebiotic, preferentially promoting beneficial bacteria while potentially suppressing less desirable taxa. The observed growth promotion of Bifidobacterium indicates CPP's ability to serve as a fermentable substrate for probiotics, highlighting its potential to beneficially modulate gut microbiota composition. Further research with larger sample sizes would help clarify CPP's broader impacts on microbial communities and associated health benefits [

63]. CPPs, particularly inulin-type fructans with high degrees of polymerization (DP 16–31), exhibit significant prebiotic activity by selectively stimulating beneficial gut bacteria such as Bifidobacterium longum. These fructans, structurally confirmed by MALDI-TOF-MS and NMR, resist digestion and reach the colon intact, where they are fermented by probiotics, promoting microbial growth and SCFA production. Studies show that at 2.0 g/L, Codonopsis fructans significantly enhance B. longum growth in a time-dependent manner (p < 0.01), comparable to prebiotics like chicory inulin. By modulating gut microbiota composition—increasing Bifidobacteriaceae and Lachnospiraceae—they improve gut barrier function, reduce inflammation, and alleviate gastrointestinal disorders such as ulcerative colitis and IBS. Their mechanisms include competitive exclusion of pathogens, immune modulation via SCFAs, and enhanced nutrient absorption [

64].

Cao et al. (2022) demonstrated that CPP exhibit significant prebiotic effects in spleen deficiency syndrome (SDS) by modulating gut microbiota and host metabolism. Their study revealed that CPP selectively enriched beneficial Lactobacillus while suppressing opportunistic pathogens like Enterococcus and Shigella, with these microbial changes being essential for CPP's therapeutic effects as evidenced by antibiotic ablation experiments. The researchers found that CPP administration improved key SDS indicators including D-xylose absorption, gastrointestinal hormone levels, and goblet cell function. Through integrated 16S rRNA sequencing and targeted metabolomics, Cao et al. identified that CPP significantly altered 25 colonic metabolites, particularly enhancing energy-related pathways involving amino acid metabolism, TCA cycle, and nitrogen metabolism. Their correlation analysis established strong relationships between the microbiota changes, metabolic shifts, and clinical improvements, providing mechanistic evidence for CPP's prebiotic activity in SDS [

65].

Fu et al. (2018) demonstrated that CPP exhibits significant prebiotic activity by modulating gut microbiota and enhancing intestinal mucosal immunity in immunosuppressed mice. CPP administration restored gut-associated immune markers, including ileal secretory IgA (sIgA) and systemic cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-10), while increasing beneficial Lactobacillus abundance and cecal acetic acid levels. These effects suggest CPP selectively stimulates probiotic growth and SCFA production, which are critical for maintaining gut barrier integrity and inhibiting pathogenic colonization. By recovering the spleen index and serum IgG, CPP further linked gut microbiota modulation to systemic immunity. The study highlights CPP’s dual prebiotic role: (1) fostering a probiotic-rich microbiota (Lactobacillus) and (2) enhancing mucosal immunity (sIgA) and anti-inflammatory responses (IL-10), positioning it as a natural immunoregulator [

66].

Zou et al. (2023) elucidated how CPP-1 exerts comprehensive anti-aging effects by orchestrating gut-liver crosstalk. The study revealed that CPP-1 administration (10–20 mg/mL) initiates a cascade of protective mechanisms beginning with gut microbiota restoration, where it selectively enriches beneficial bacteria like Bacteroides and Dubosiella while increasing production of immunomodulatory SCFAs and reducing pro-inflammatory lipopolysaccharides. This microbial reprogramming synergizes with CPP-1's direct reinforcement of intestinal barrier integrity through upregulation of tight junction proteins and enhancement of endogenous antioxidant systems (SOD, GPX, CAT), effectively neutralizing oxidative stress. The polysaccharide's systemic impact emerges through its suppression of TLR4-mediated inflammation, evidenced by reduced IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α levels in both intestinal macrophages and hepatic tissues, thereby breaking the vicious cycle of gut-derived inflammation and liver damage (

Figure 5). Concurrently, CPP-1 ameliorates age-related metabolic dysregulation by normalizing lipid metabolism pathways in the liver, an effect attributed to improved microbial metabolite profiles and diminished LPS translocation. By simultaneously targeting microbial ecology, intestinal barrier function, oxidative stress, and inflammatory signaling, CPP-1 establishes itself as a unique polypharmacological agent that addresses multiple hallmarks of aging through its integrative action on the gut-liver axis, offering novel therapeutic potential for age-related degenerative conditions [

67].

CPPF, an inulin from the roots of

C. pilosula exhibits significant prebiotic effects by modulating gut microbiota composition in immunosuppressed mice. CPPF administration effectively restored microbial diversity, counteracting cyclophosphamide-induced dysbiosis, and enhanced beneficial Firmicutes including Oscillibacter, Ruminococcaceae, and Lachnoclostridium while reducing harmful Bacteroidetes and Deferribacteres. Notably, CPPF promoted the recovery of short-chain fatty acid-producing bacteria like Papillibacter and Clostridium ASF356, which are crucial for gut barrier function and immune regulation. CPPF demonstrated a particular ability to restore key commensal bacteria such as Ruminococcus and Lachnospiraceae, while suppressing inflammation-associated taxa like Muribaculaceae [

68].

2.9. Wound Healing Effects of CPPs

Yang et al. 2022 reported that CPPs exhibit significant wound-healing properties, particularly when formulated into microcapsules (CPPM). Structural and physicochemical analyses revealed that CPPM possesses a hollow, sac-like morphology with rough folds and protrusions, appearing in uniform spherical or ellipsoidal shapes. These microcapsules demonstrate favorable characteristics such as swelling capacity, low hardness, strong adhesion, and stability, making them well-suited for wound care applications. In a rat model, CPPM was found to accelerate wound closure by enhancing the healing rate, with histological evaluations confirming its ability to promote neovascularization and fibroblast proliferation—key processes in tissue regeneration. Mechanistic studies indicate that CPPM increases hydroxyproline content, boosting collagen synthesis and strengthening the extracellular matrix. Additionally, CPPM exhibits potent antioxidant activity, reducing oxidative stress by inhibiting lipid peroxidation and protecting cells from damage. At the molecular level, CPPM upregulates the expression of VEGF (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor) and miRNA-21, which are critical for angiogenesis, cell proliferation, and tissue remodeling [

69].

In a significant advancement in wound healing research, Wang et al. (2022) developed an innovative microencapsulated delivery system for Codonopsis pilosula polysaccharides (CPNP) that demonstrates remarkable therapeutic potential for skin repair. The researchers successfully fabricated CPNP microcapsules through ionic gelation with sodium alginate and Ca²⁺ ions, creating uniformly sized microspheres (21.25 ± 2.84 μm) with exceptional pharmaceutical properties, including a high drug loading capacity (61.59%), impressive encapsulation efficiency (55.99%), and extraordinary swelling behavior (397.38 ± 25.32%) that ensures optimal moisture retention at wound sites. When evaluated in a rat wound model, these microcapsules exhibited outstanding wound healing performance, dramatically accelerating tissue regeneration while effectively suppressing common complications such as inflammation, excessive exudate, and microbial infection. Comprehensive histopathological analysis revealed the microcapsules' ability to orchestrate a sophisticated repair process, stimulating robust neovascularization, promoting the deposition of well-organized collagen fibers, and significantly reducing inflammatory cell infiltration compared to control groups. At the molecular level, the CPNP microcapsules demonstrated a multifaceted mechanism of action, simultaneously downregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines while boosting the activity of crucial antioxidant enzymes (GSH-Px, T-AOC, LPO) and dramatically upregulating expression of key regenerative factors - notably increasing VEGF levels by 2.1-fold and miRNA-21 by 1.8-fold - which collectively enhance angiogenesis, fibroblast proliferation, and extracellular matrix remodeling [

70].