1. Introduction

Indonesia is very susceptible to earthquakes and tsunamis due to its position at the intersection of four significant tectonic plates: the Indo-Australian, Eurasian, Philippine, and Pacific [

1,

2,

3,

4]. This complex tectonic interaction creates a highly dynamic and seismically active environment, resulting in significant loss of life and economic devastation. For example, the loss of life and economic loss due to the 2024 Aceh earthquake and tsunami, it is estimated that the death toll reached 173,741 people and the financial loss was worth 4.9 billion USD [

5]. The Indonesian Tsunami Early Warning System (InaTEWS) was built in 2008 to warn early of tsunamis caused by significant offshore earthquakes, lowering risks and boosting community resilience.

Earthquake magnitude estimation is crucial for earthquake and tsunami early warnings, while magnitude scaling is derived primarily from seismic sensors. However, magnitude saturation often occurs for large earthquakes (Mw > 7.5), leading to underestimated initial values. For example, in the 26 December 2004 Aceh tsunami, the

Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC) initially estimated a magnitude of Mw 8.0, 11 minutes after origin time (OT), 1 hour later rise to Mw 8.5, and a few days later revised to Mw 9.2 after more seismic data became available [

6,

7,

8]. Similarly, during the 2011 Tohoku tsunami in Japan, the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) first estimated Mw 7.9 within three minutes, later updating it to Mw 8.4 and finally to Mw 9.0 after several days [

9,

10]. If the actual size of earthquakes had been determined earlier, more effective evacuations could have been possible.

Magnitude saturation occurs when seismic signals from surrounding sensors are clipped, resulting in off-scale amplitudes. Large earthquakes generate signals that surpass the seismometer's dynamic range, resulting in incorrect results [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Furthermore, acceleration recordings are utilized in the near-field of major earthquakes because they do not undergo amplitude saturation. However, identifying the magnitude involves integrating acceleration to obtain displacement, which was caused by baseline drift due to factors such as instrument tilt and rotation [

13,

15,

16]. High-rate GNSS data, however, provide direct displacement measurements without these limitations, making them valuable for real-time earthquake magnitude estimation [

13,

14,

15,

16].

Numerous studies have demonstrated that peak ground displacement (PGD) derived from high-frequency (1 Hz) GNSS data can accurately estimate earthquake magnitude, even before the rupture process is completed [

17,

18,

19,

20]. PGD is defined as the maximum displacement observed in a time series. Crowell et al. [

12] introduced the PGD Scaling Law, which establishes a quantitative relationship between peak ground displacement and the distance from the earthquake epicenter. This algorithm enables the rapid and accurate calculation of earthquake moment magnitude (Mw) by comparing the maximum ground displacements recorded at multiple GNSS stations.

Indonesia's Tsunami Early Warning System (InaTEWS) relies on seismometer recordings to determine earthquake parameters, including location, magnitude, and moment tensor. Despite Indonesia having 473 continuously operating GNSS stations within the Indonesian Continuously Operating Reference Station (InaCORS) network, high-rate GNSS (HR-GNSS) data has not yet been incorporated into earthquake parameter determination in InaTEWS. Instead, GNSS data is primarily used in surveying and applications. [

21]

This paper introduces a novel PGD Scaling Law that utilizes PGD extracted from GNSS displacement waveforms to determine earthquake magnitude in Indonesia. Initially, we examine the attenuation relationship of PGD concerning hypocentral distance using 87 displacement records from 21 moderate to large earthquakes in Indonesia. We then use this attenuation relationship to derive a PGD scaling law. Finally, we apply the PGD scaling law to estimate and compare earthquake magnitudes with the reported moment magnitudes. Our regional PGD Scaling Law, derived from Indonesia-specific GNSS data, demonstrates accuracy compared to global models, as evidenced by a more favorable mean absolute deviation (MAD) value, and provides robust estimates of earthquake magnitude.

2. Materials and Method

2.1. High-Rate GNSS Data Collection

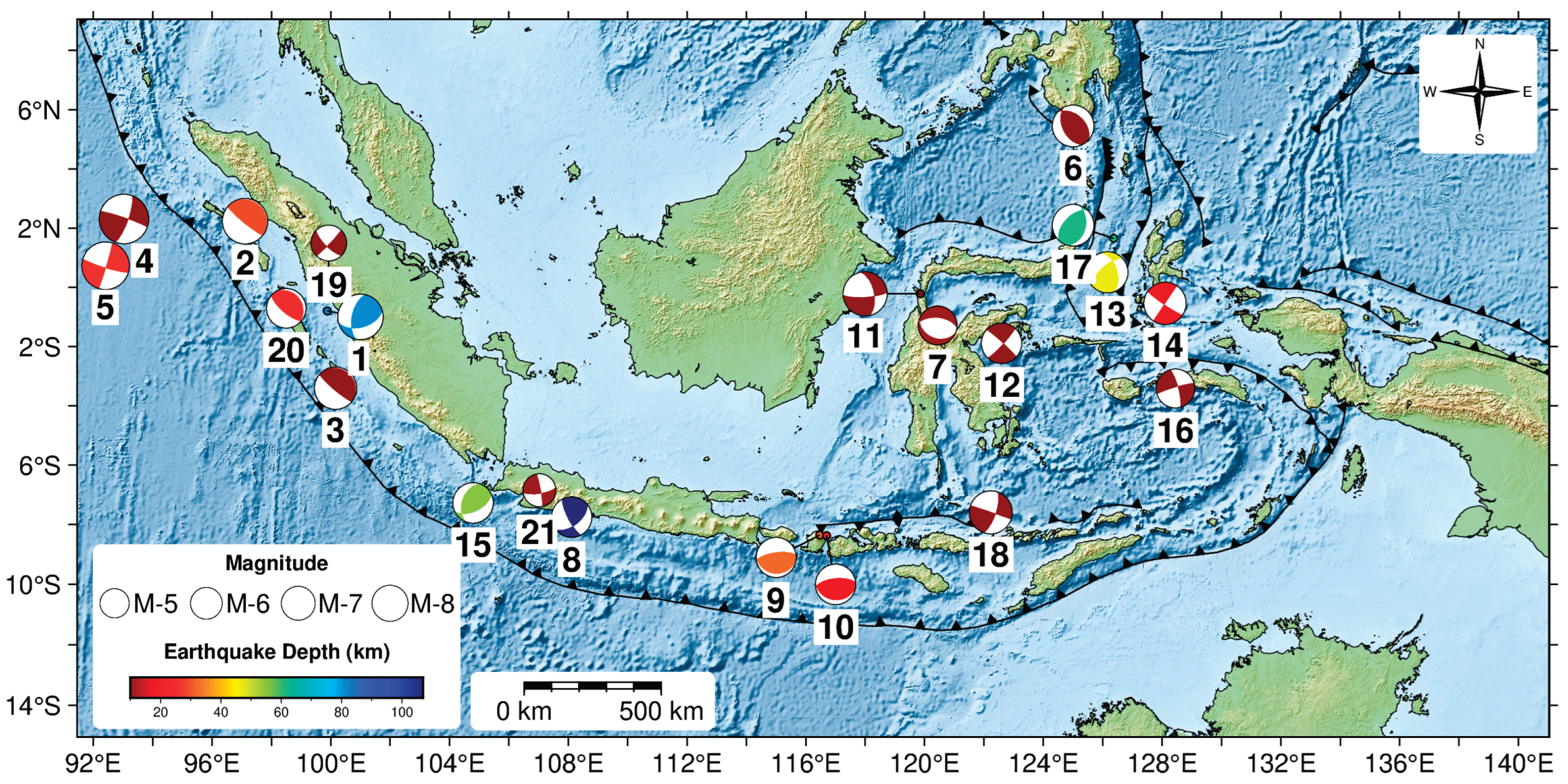

We acquired 1 Hz high-rate GNSS data of 21 moderate to large earthquakes in Indonesia between 2009 and 2022, with magnitudes ranging from Mw 5.6 to 8.4 (

Figure 1 and

Table 1). This high-rate GNSS data, a significant component of our research, was collected from two networks: the Sumatran GPS Array (SuGAr) and the Indonesia Continuously Operating Reference Station (InaCORS). SuGAr stretches over a thousand kilometers at the tectonic border where the Indo-Australian and Asian plates converge. The Earth Observatory of Singapore (EOS) manages this network, which has recently extended to include 60 continuous GNSS stations. It offers essential data for understanding the Sunda megathrust and the Sumatran fault [

23]. The Geospatial Information Agency (BIG) administers InaCORS, which comprises 473 GNSS stations across Indonesia. This network may enable various applications, including high-precision mapping, navigation, and geodynamic monitoring [

21].

Due to the inherent noise levels of approximately 1-2 cm in GNSS data [

15], stations farther from the earthquake hypocenter often fail to record substantial signals for certain moderate-magnitude events. Consequently, we selected GNSS waveforms exhibiting peak amplitudes of no less than 2 cm, resulting in 87 high-rate GNSS recordings across three components (east, north, and vertical) from 21 moderate to large earthquakes in Indonesia. The HR GNSS data, provided in the Receiver Independent Exchange Format (RINEX), were processed to derive earthquake displacement data using the Precise Point Positioning with Ambiguity Resolution (PPP-AR) technique [

24,

25,

26], implemented through the PRIDE PPP-AR software developed by the GNSS Research Center at Wuhan University [

27]. The PPP-AR method necessitates the integration of precise satellite orbit and clock corrections, thereby ensuring centimeter-level accuracy in the displacement measurements.

2.2. PGD Scaling Law

Peak Ground Displacement (PGD) is the maximum dynamic displacement recorded at a GNSS station during an earthquake. This value is calculated as the Euclidean norm of the three components (N, E, U), expressed mathematically as follows:

PGD Scaling Law defines the relation between PGD, moment magnitude (Mw), and the distance from the earthquake hypocenter to the GNSS station (R) as follows [

15,

16,

17,

18].

where M

w is moment magnitude (M

w) determined by BMKG; R is the hypocentral distance in km; and A, B and C are the regression coefficients.

Another study previously employed a PGD Scaling Law for moderate to large earthquakes, based on global displacement HR GNSS worldwide [

13,

14,

15]. We attempted to develop our local PGD scaling law using 87 HR Data GNSS from 21 moderate to major earthquakes in Indonesia. We use linear regression with the least squares method to analyze the 87 PGD measurement data and obtain the regression coefficients (A, B, C). We estimate them using a bootstrap approach, randomly removing 10% of PGD measurements and rerunning the regression. We repeat this step 1000 times to estimate the variance of the coefficients and present the uncertainties as the 95% confidence intervals of each coefficient.

3. Results

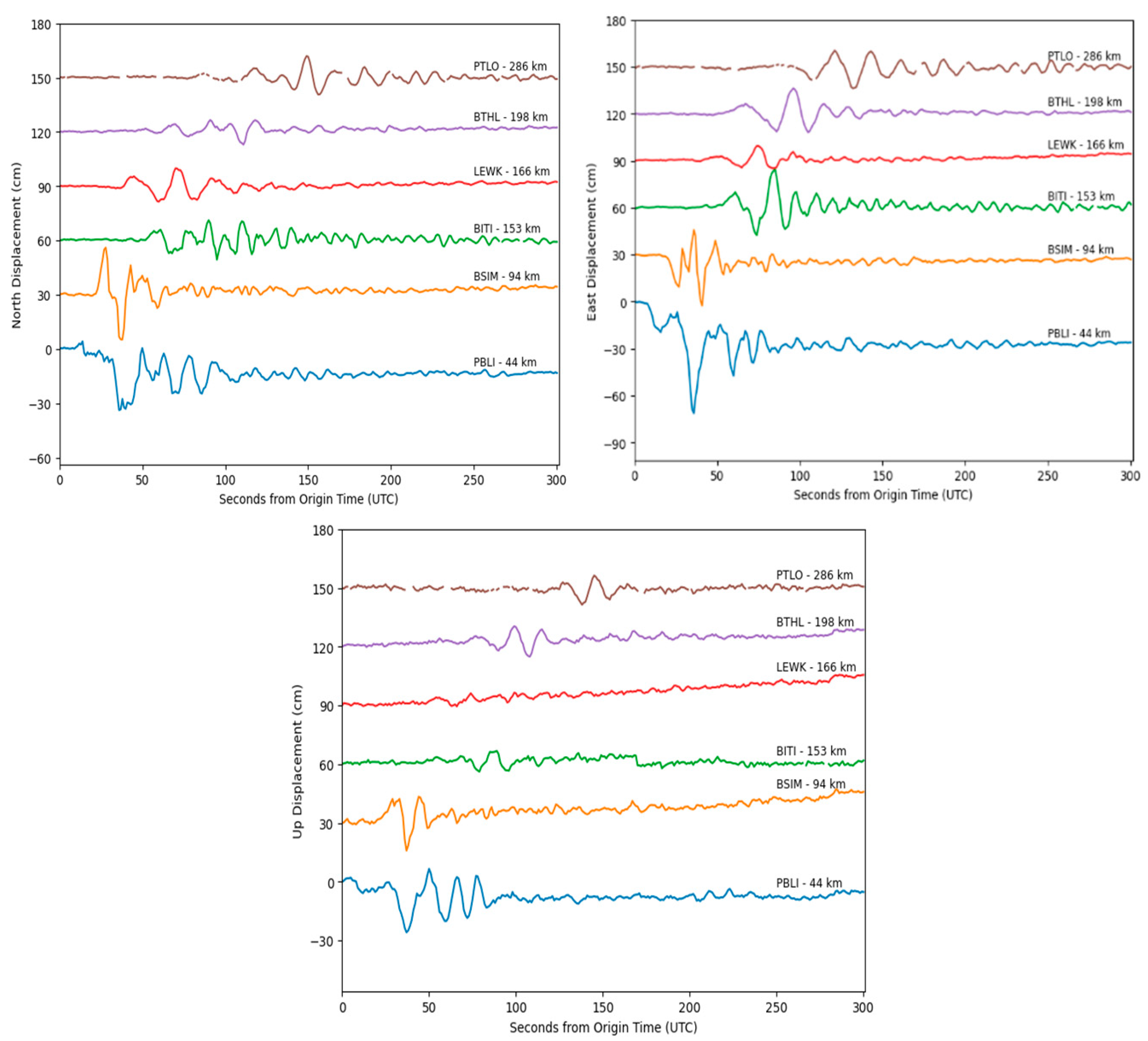

To evaluate the effectiveness of early peak ground displacement (PGD) measurements for rapid magnitude estimation, the kinematic displacement time series was truncated to a 5–7 minute window following the earthquake origin time (OT).

Figure 2 presents the displacement waveforms of the Mw 7.7 Sinabang earthquake (6 April 2010) in three components (East, North, and Up), as recorded by six high-rate GNSS stations. A systematic decrease in displacement amplitude with increasing hypocentral distance is observed, consistent with theoretical expectations of ground motion attenuation.

Figures S1–S5 in the Supplementary Material shows the epicenters and GNSS station locations alongside the displacement waveforms recorded by at least six High-Rate GNSS stations for selected earthquakes.

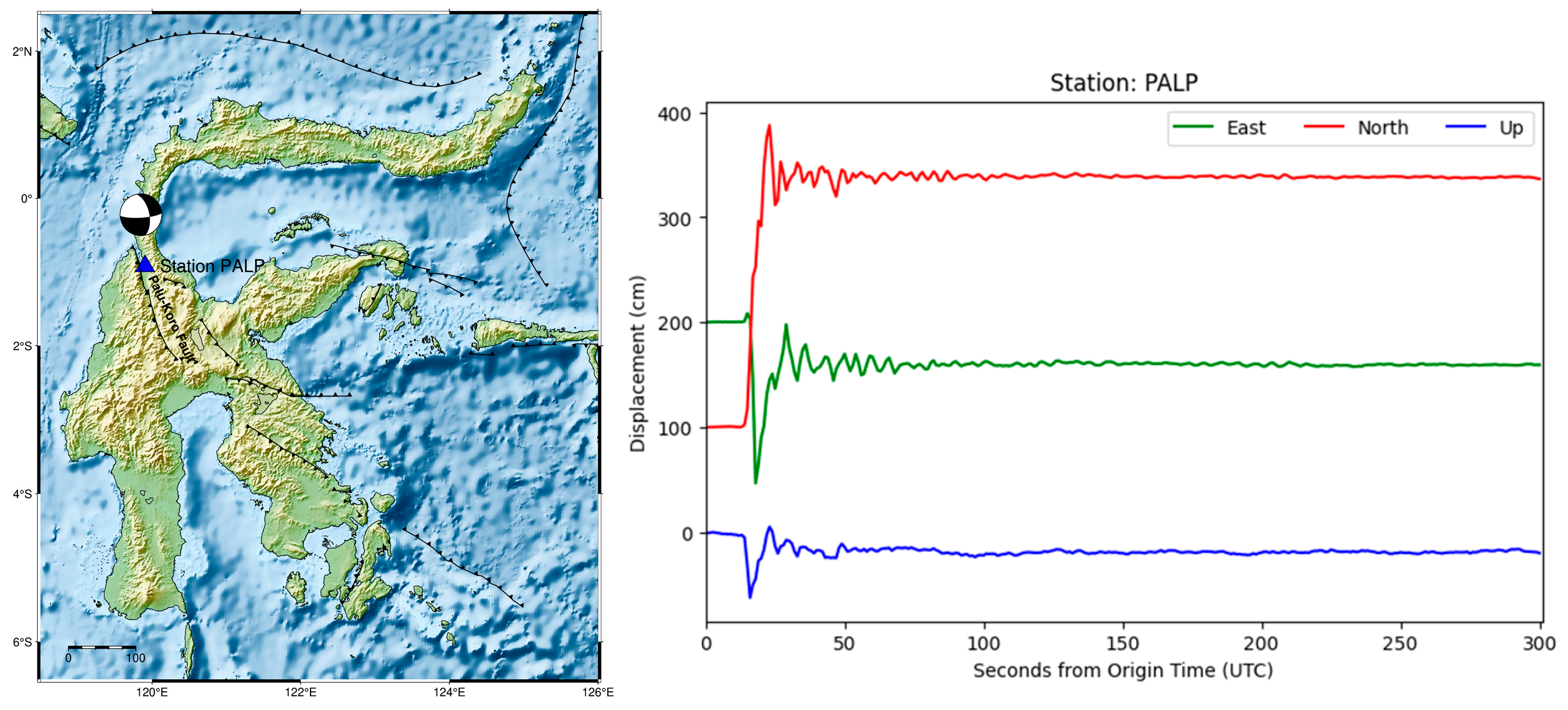

Table S1 in the Supplementary Material presents the Peak Ground Displacement (PGD) calculation results and the corresponding hypocentral distances for each HR GNSS station across 21 moderate to large earthquakes. The PGD values, derived from 87 HR GNSS stations, range from 2.01 cm to 292.96 cm. The smallest PGD (2.01 cm) was recorded at the CPMK station during the Mw 6.9 earthquake on December 15, 2017, in Tasikmalaya, West Java. In contrast, the largest PGD (292.96 cm) was observed at the PALP station for the Mw 7.5 earthquake on September 28, 2018, in Palu-Donggala, Central Sulawesi. The hypocentral distances of the HR GNSS stations ranged from 17 km to 1287 km.

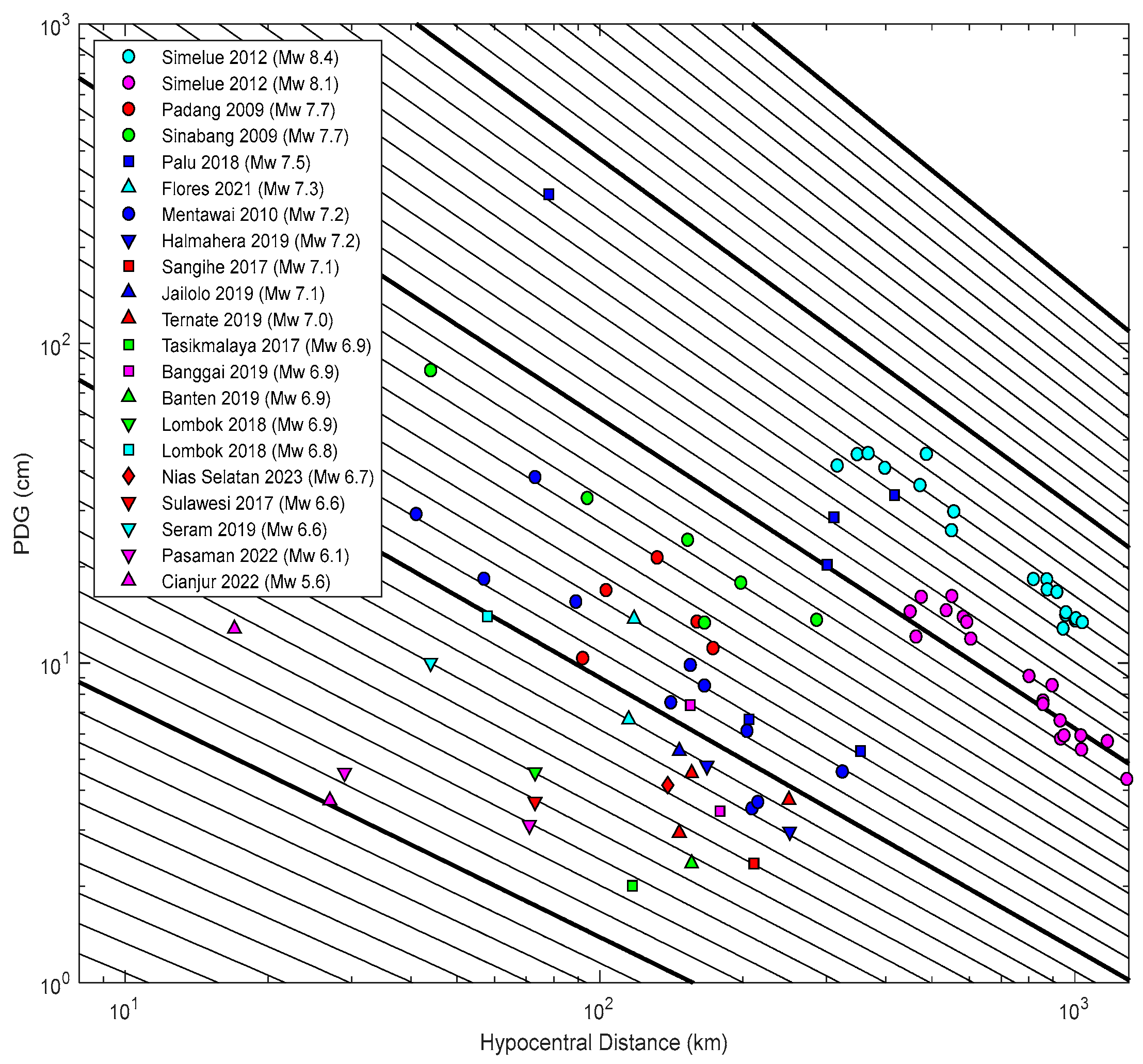

The regression coefficients obtained from the linear regression analysis were as follows: A = -4.729 ± 0.255, B = 1.055 ± 0.045, and C = -0.121 ± 0.006, with a residual standard deviation of 0.30 magnitude units. The Peak Ground Displacement (PGD) Scaling Law was derived based on data from 87 High-Rate GNSS stations, corresponding to 21 moderate to major earthquakes in Indonesia, and is expressed as follows:

Figure 3 presents the distribution of PGD as a function of hypocentral distance. PGD measurements at each station are plotted, with color and marker types distinguishing different earthquakes. The oblique lines illustrate predicted magnitudes as a function of PGD and hypocentral distance. The PGD measurements for each event generally fluctuate among the oblique lines and decrease in amplitude as the hypocentral distance increases. The plot reveals a clear attenuation trend, with PGD decreasing approximately logarithmically with distance. Events of higher magnitude consistently produce larger PGDs at all distances.

Several well-recorded large-magnitude earthquakes (e.g., the doublet Simeulue 2012, Padang 2009, Sinabang 2010, Palu-Donggala 2018) form an upper bound to the PGD distribution. Meanwhile, moderate-magnitude events (e.g., Cianjur 2022, Mw 5.6) show PGDs confined to the lower part of the graph. Additionally, shallow earthquakes, particularly strike-slip events such as Palu 2018 (Mw 7.5), generate high PGDs at relatively short hypocentral distances, highlighting the hazard potential of near-field ruptures. In contrast, deeper events (e.g., Tasikmalaya 2017, depth 107 km) generate significantly lower surface displacements, even at moderate distances.

Using the determined PGD Scaling Law, we compute the mean PGD magnitude (M

PGD) estimation and its standard deviation for each of the 21 events, as detailed in

Table 1.

Table 1 also informs 21 earthquake events across Indonesia between 2009 and 2022 that were analyzed to evaluate the relationship between moment magnitude (Mw) and magnitude estimated from peak ground displacement (M

PGD). The events exhibit diverse tectonic settings, encompassing strike-slip, reverse, and normal fault mechanisms. Most earthquakes occurred at shallow depths (<30 km), with a few exceptions such as the Padang (81 km) and Tasikmalaya (107 km) events, which occurred at intermediate depths.

Table 1 also shows the number of High-Rate GNSS (HR GNSS) stations that recorded surface displacement during earthquakes, ranging from 1 to 19 per event. As of the most recent data, Indonesia has 473 continuous HR GNSS stations under the InaCORS (Indonesian Continuous GNSS Network), although the overall density remains relatively sparse. The average inter-station distance is approximately 72 km, and has steadily expanded since 2021 [

29], while adequate for broad-scale monitoring, may limit the spatial resolution of surface displacement data, particularly in seismically active regions.

The number of GNSS stations significantly influenced the robustness of the MPGD estimates. Events with more than five GNSS stations, such as the Simeulue and Mentawai earthquakes, exhibited lower standard deviation in MPGD. In contrast, events monitored by only one or two stations, like the Sangihe or Palu 2017 earthquakes, showed larger standard deviation ranges in magnitude estimation. Overall, MPGD estimates are closely aligned with Mw, with a mean residual standard deviation of 0.3 magnitude units, indicating the robustness of PGD scaling for rapid magnitude estimation.

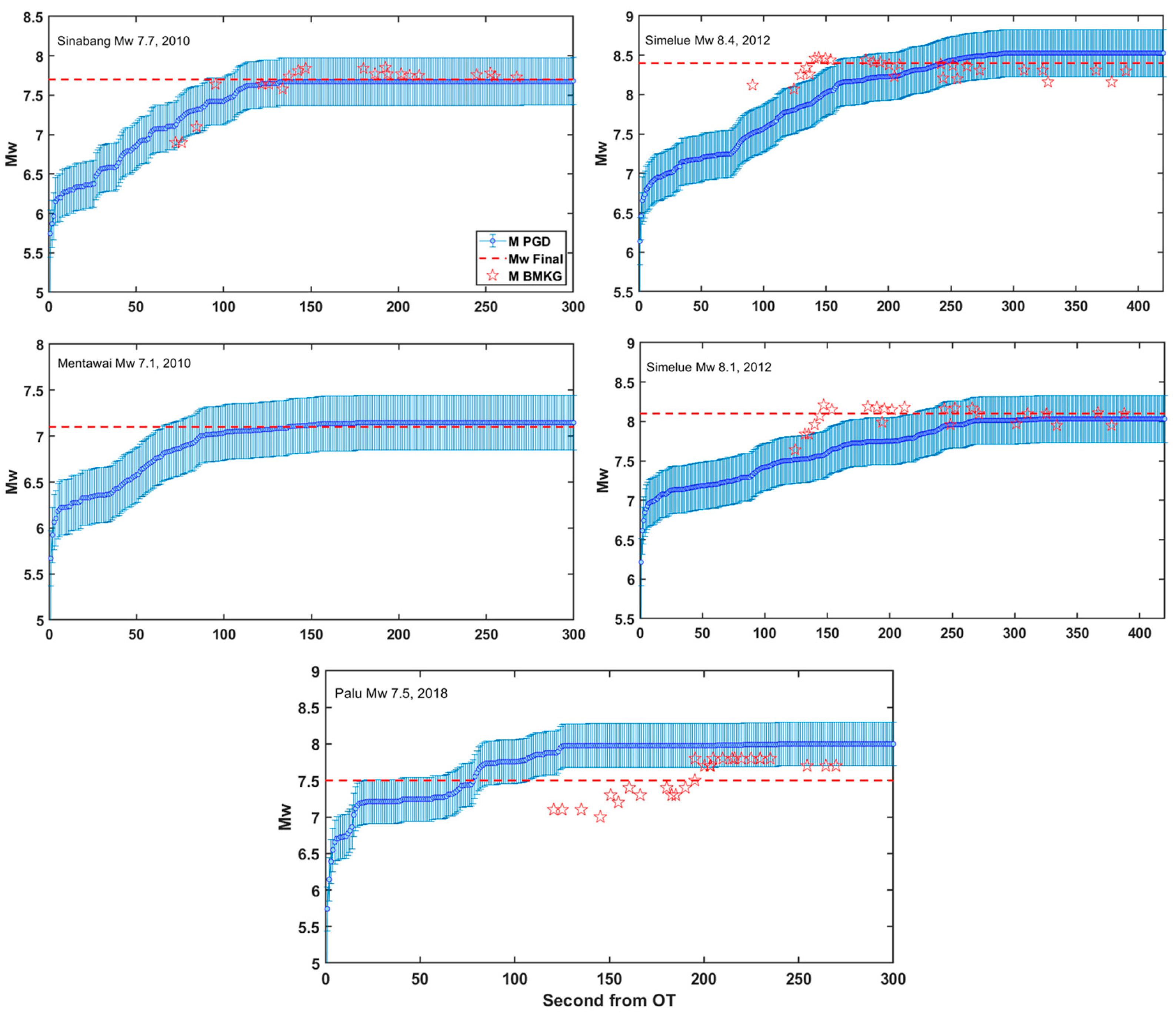

We also conducted retrospective magnitude evolution estimations for several large earthquakes using high-rate GNSS data (

Figure 4), focusing on events recorded by a minimum of six stations to ensure magnitude stability, with a mean error of ≤ 0.3 magnitude units as found in research by Ruhl et al. [

17]. The five earthquakes include: the Mw 7.7 Sinabang (2010), Mw 7.2 Mentawai (2010), Mw 8.4 Simeulue (2012), Mw 8.1 Simeulue (2012), and Mw 7.5 Palu-Donggala (2018) events.

MPGD estimates initially exhibit significant variability within the first 50–100 seconds from OT for all events due to the dynamic rupture evolution and limited early PGD observations. As more GNSS data become available and peak displacements are recorded, the magnitude estimates converge progressively toward stable values. In the case of the Sinabang (2010) and Mentawai (2010) earthquakes, the MPGD stabilized within approximately 125 s from OT, accurately matching the final Mw values of 7.7 and 7.1, respectively. Similarly, for the doublet Simeulue earthquakes (2012), the stable MPGD was achieved at 8.53 ± 0.15 and 8.03 ± 0.12 within approximately 300 s from OT, which closely correspond to the final moment magnitude from BMKG Mw 8.4 and Mw 8.1, respectively. Across all events, BMKG initial seismic magnitude estimates (red stars) tend to underestimate the final Mw, especially for the great magnitude events (Mw > 8.0). In contrast, PGD-based estimates show a more consistent trend toward the final values. These results demonstrate the robustness and reliability of the PGD scaling method for rapid earthquake magnitude estimation.

4. Discussion

Based on the PGD (Peak Ground Displacement) magnitude estimation results for the 21 earthquakes used to develop the PGD scaling law, the standard deviation of the estimated magnitudes ranges from 0.02 to 0.74 (

Table 1). Generally, lower standard deviation values are observed for earthquakes in which at least six GNSS stations recorded the displacement. For instance, significant events along the Sumatra plate boundary, such as the Mw 7.7 Sinabang earthquake (2010), the Mw 8.4 Simeulue earthquake (2012), and the Mw 8.1 Simeulue earthquake (2012), exhibited more minor uncertainties. This finding is consistent with the results reported by Ruhl et al. [

17], who demonstrated that stable magnitude estimates, with uncertainties equal to or less than 0.3 magnitude units, require observations from a minimum of six high-rate GNSS stations. It also aligns with the finding by Gao et al. [

16], who noted that an increase in GNSS stations improves the accuracy of the final magnitude estimates. Notably, the estimations for the two great earthquakes in Simeulue (Mw 8.4 and Mw 8.1), with M

PGD values of 8.53 ± 0.15 and 8.03 ± 0.12, respectively, confirm that the PGD magnitude estimations do not exhibit saturation even for very large events.

Anomalously high PGD magnitude estimates were observed for the Mw 7.5 Palu earthquake (28 September 2018), reaching 7.98 ± 0.74. This overestimation is primarily attributed to the large peak ground displacement (2.93 m;

Table S1) recorded at the PALP GNSS station, located approximately 78 km south of the epicenter. The rupture propagated southward along the Palu-Koro fault at supershear velocity, exceeding the crust's shear wave speed, resulting in intense fault-parallel ground motion [

30,

31]. PALP, situated near the fault trace, recorded a fault-parallel velocity (~1.0 m/s) substantially greater than the fault-normal component (~0.7 m/s) [

32], consistent with theoretical and numerical models of supershear rupture dynamics [

33]. The location of the epicenter and PALP station, along with the observed displacement, are shown in

Figure 5. The retrospective analysis reveals that the mean M

PGD reached 7.5 at 78 s after OT and continued to increase, eventually stabilizing at M

PGD 7.98 around 126 s from OT. This finding highlights the capability of the PGD method to provide a rapid and stable magnitude rather than seismic magnitude estimates, which remained underestimated during the initial time of the earthquake.

Numerous studies have established Peak Ground Displacement (PGD) Scaling Laws utilizing high-rate GNSS (HR-GNSS) data from global seismic events, including those by Melgar et al. [

13], Crowell et al. [

14], and Ruhl et al. [

15]. Building upon this foundation, the present study aims to develop a PGD Scaling Law based on regional HR-GNSS displacement data specifically recorded from seismic events in Indonesia.

Table 2 compares the PGD Scaling Law coefficients derived in this study and those reported in the previous works.

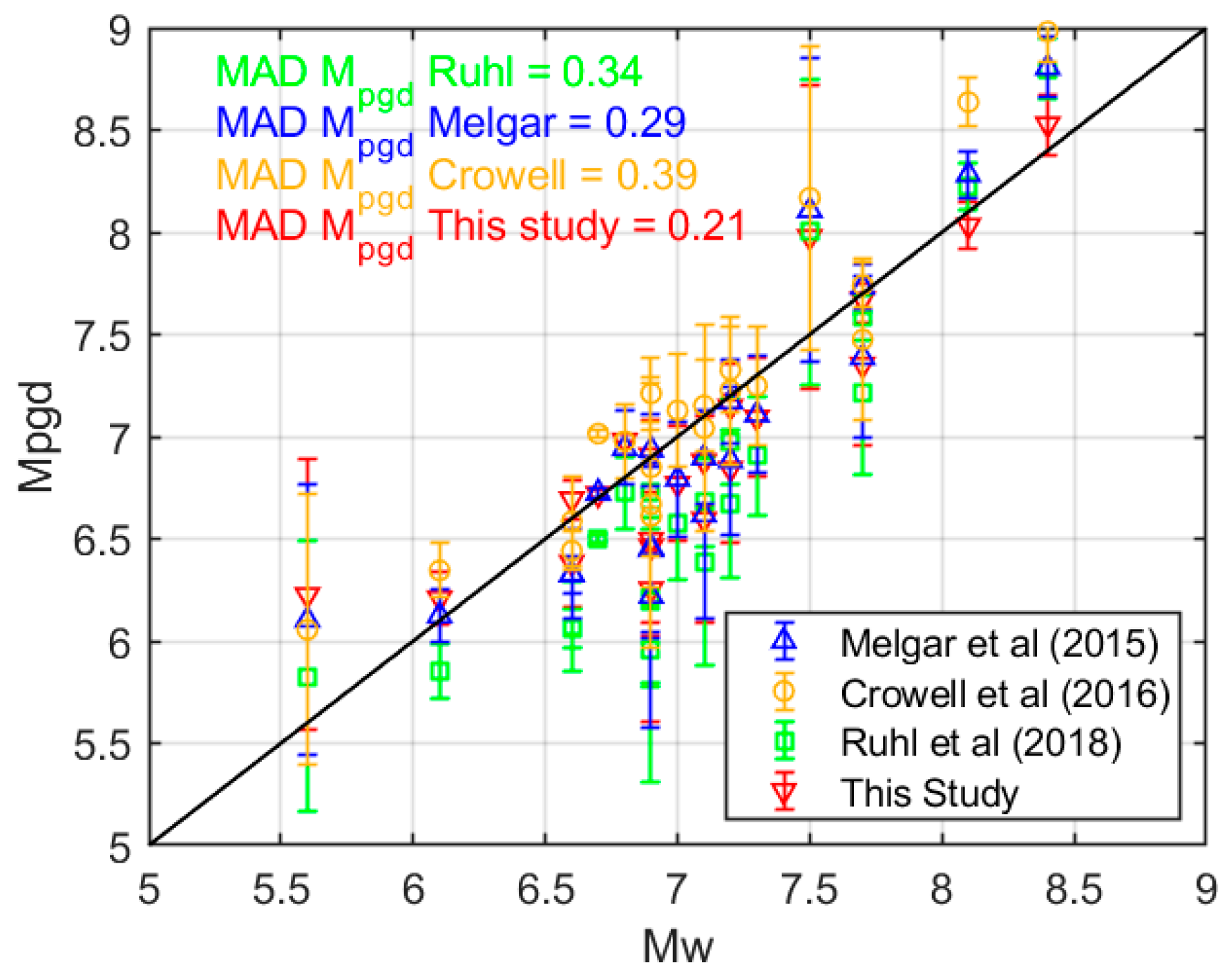

To evaluate the accuracy of the proposed PGD Scaling Law in estimating the magnitude from peak ground displacement (MPGD), a comparative analysis was conducted using 21 moderate to large earthquakes that occurred in Indonesia. The mean absolute deviation (MAD) between the MPGD-derived magnitudes and the catalog moment magnitudes (Mw) was calculated for this study and for scaling laws proposed by Melgar et al. [

13], Crowell et al. [

14], and Ruhl et al. [

15]. As shown in

Figure 6, the MAD for the proposed model is 0.21, which is lower than the MADs of 0.29, 0.39, and 0.34 for the models by Melgar et al., Crowell et al., and Ruhl et al., respectively.

Based on Indonesia-specific high-rate GNSS data, the regional PGD Scaling Law developed in this study demonstrates improved accuracy over global models, as reflected by a lower mean absolute deviation (MAD), and yields robust and reliable earthquake magnitude estimates. These results indicate that the PGD Scaling Law derived from this study produces a more accurate fit that captures the regional tectonic characteristics of the Indonesian region.

Based on the standard operating procedure of the Indonesia Tsunami Early Warning System (InaTEWS), since 2024, real-time earthquake parameters such as origin time, hypocenter location, and magnitude must be provided by BMKG in less than 3 minutes [

34]. From the results of retrospective analysis of several large earthquakes, the magnitude estimation results were obtained with stable GNSS high rate PGD data in less than 3 minutes, for example the Sinabang earthquake, Mentawai earthquake, and Palu-Donggala earthquake, while for the Simeleu doublet earthquake where the hypocenter location in ocean quite far from the Sumatra mainland where the GNSS sensor is located, around 300 km so that a stable magnitude estimate can be obtained approximately 300 seconds after OT. The results reaffirm the capability of GNSS displacement data to complement and enhance traditional seismic networks to provide reliable earthquake magnitude estimates that are crucial in tsunami and earthquake early warning systems, particularly for large and tsunamigenic events in the Indonesian region. This proves that PGD Magnitude has great potential to be implemented in real time in the Indonesian Tsunami Early Warning System. However, challenges such as station density and data latency remain key considerations and future works for real-time operational implementation.

5. Conclusions

We propose a novel regionally calibrated Peak Ground Displacement (PGD) Scaling Law for rapid and reliable earthquake magnitude estimation in Indonesia. This model is developed using 87 high-rate GNSS (HR-GNSS) displacement records from 21 moderate to large earthquakes and establishes a robust empirical relationship between PGD, hypocentral distance, and moment magnitude (Mw). The resulting PGD-derived magnitudes (MPGD) demonstrate strong agreement with reported catalog Mw values, achieving a mean absolute deviation (MAD) of 0.21, outperforming previously published global models.

Notably, the proposed scaling law shows no evidence of magnitude saturation, even for great earthquakes (Mw > 8.0), and maintains accuracy across various tectonic regimes, including strike-slip, reverse, and normal fault mechanisms. Retrospective analyses further confirm that for events recorded by six or more GNSS stations, PGD-based magnitude estimates converge rapidly, typically within 2–3 minutes of origin time, meeting the operational requirements of Indonesia’s Tsunami Early Warning System (InaTEWS). These findings reaffirm the value of HR-GNSS displacement data as a complementary tool to seismic networks for real-time magnitude estimation, particularly in tectonically complex and tsunami-prone regions like Indonesia. For continuous improvement, further validation using real-time HR GNSS displacement data from future seismic events in Indonesia will be essential to evaluate the scalability and operational reliability of the proposed model.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Epicenter, GNSS Station location and displacement waveform in 3 components (E, N, U) of Mw7.7 Sinabang, 6th April 2010; Figure S2: Epicenter, GNSS Station location and displacement waveform in 3 components (E, N, U) of Mw7.1, Mentawai, 25th October 2010; Figure S3: Epicenter, GNSS Station location, and displacement waveform in 3 components (E, N, U) of Mw8.4, Simelue, 11th April 2012; Figure S4: Epicenter, GNSS Station location, and displacement waveform in 3 components (E, N, U) of Mw8.1, Simelue, 11th April 2012; Figure S5: Epicenter, GNSS Station location, and displacement waveform in 3 components (E, N, U) of Mw7.5, Palu-Donggala, 28th September 2018; Table S1: All Peak Ground Displacement (PGD) value and hypocentral displacement in each stations for 21 moderate and large earthquakes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.H; methodology, T.H., I.M, H.Z.A, and S.S; software, T.H., A.R, B.T.S, and A.S.M.; formal analysis, T.H..; data curation, T.H., M.A.K; writing—original draft preparation, T.H.; writing—review and editing, T.H., I.M, H.Z.A, A.S, S.R.; visualization, T.H., A.R, B.TS, A.S.M, P.H.W; supervision, I.M, H.Z.A, S.S, S.R., R.A.P.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Earthquake parameters (origin time, hypocenter, and Mw) were obtained from InaTEWS Earthquake Repository, developed by Meteorological, Climatological, and Geophysical Agency of Indonesia (BMKG,

https://repogempa.bmkg.go.id/, accessed on 12th November 2024). The source mechanism from Global Centroid Moment Tensor (GCMT) catalog. (

https://www.globalcmt.org/CMTsearch.html, accessed on 12th November 2024).

Acknowledgments

Greatly appreciate to The Earth Observatory of Singapore (EOS) and Indonesian Geospatial Information Agency for providing high-rate GNSS data. PRIDE software [27] comes from

https://github.com/PrideLab/PRIDE-PPPAR, accessed on 20th August 2024. All figures were made using the Generic Mapping Tools (GMT) software package [35] (

https://www.soest.hawaii.edu/gmt), accessed on 17th December 2024.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hutchings, S.J.; Mooney, W.D. The Seismicity of Indonesia and Tectonic Implications. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 2021, 22, e2021GC009812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcomb, K.R.; McCann, W.R. Seismic history and seismotectonics of the Sunda arc. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 1987, 92(B1), 421–439. [CrossRef]

- Bock, Y.; Prawirodirdjo, L.; Genrich, J. F.; Stevens, C. W.; McCaffrey, R.; Subarya, C. , Puntodewo, S.S.O.; Calais, E.; Crustal motion in Indonesia from Global Positioning System measurements. J. Geophys. Res. 2003, 108(B8), 2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton, T.R. Tertiary evolution of the Eastern Indonesia Collision Complex. J. Asian Earth Sci., 2000, 18(5), 603–631. [CrossRef]

- Syamsidik; Nugroho, A: Oktari, R.S.; Fahmi, M.; Aceh Pasca 15 Tahun Tsunami: Kilas Balik dan Proses Pemulihan. Tsunami and Disaster Research Center (TDMRC): Banda Aceh, Indonesia. 2019., pp. I.5–II.4.

- Kerr, R.A. Failure to Gauge the Quake Crippled the Warning Effort. Science, New Series. 2005. 307, 201.

- Stein, S.; Okal, E. Speed and size of the Sumatra earthquake, Nature 2005, 434, 581–582.

- Blewitt, G.; Kreemer, C. , Hammond, W. C, Plag H-P; Stein, S.; Okal, E., Rapid determination of earthquake magnitude using GPS for tsunami warning systems, Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33, L11309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T. J.; Houlié, N.; Hildyard, M.; and Iwabuchi, T. Real-time, reliable magnitudes for large earthquakes from 1 Hz GPS precise point positioning: The 2011 Tohoku-Oki (Japan) earthquake, Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39, L12302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; Tsushima, H.; Miura, S.; Hino, R.; Takasu, T.; Fujimoto, H.; Iinuma, T.; Tachibana, K.; Demachi, T.; Sato, T.; Ohzono, M.; Umino, N. Quasi real-time fault model estimation for near-field tsunami forecasting based on RTK-GPS analysis: Application to the 2011 Tohoku-Oki earthquake (Mw 9. 0), J. Geophys. Res. 2012, 117, B02311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilich, A.; Cassidy, J.F.; Larson, K.M. GPS seismology: Application to the 2002 Mw 7.9 Denali fault earthquake. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2008, 98, 593–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowell, B.W.; Melgar, D.; Bock, Y.; Haase, J.S.; Geng, J. Earthquake magnitude scaling using seismogeodetic data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2013, 40, 6089–6094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgar, D.; Crowell, B.W.; Geng, J.; Allen, R.M.; Bock, Y.; Riquelme, S.; Hill, E.M.; Protti, M.; Ganas, A. Earthquake magnitude calculation without saturation from the scaling of peak ground displacement. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 5197–5205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowell, B.W.; Schmidt, D.A.; Bodin, P.; Vidale, J.E.; Gomberg, J.; Hartog, J.R.; Kress, V.C.; Melbourne, T.I.; Santillan, M.; Minson, S.E.; Jamison, D.G. Demonstration of the Cascadia G-FAST Geodetic Earthquake Early Warning System for the Nisqually, Washington, earthquake. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2016, 87, 930–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhl, C.J.; Melgar, D.; Geng, J.; Goldberg, D.E.; Crowell, B.W.; Allen, R.M.; Bock, Y.; Barrientos, S.; Riquelme, S.; Baez, J.C.; Cabral-Cano, E.; Pérez-Campos, X.; Hill, E.M.; Protti, M.; Ganas, A.; Ruiz, M.; Mothes, P.; Jarrín, P.; Nocquet, J.-M.; Avouac, J.-P.; and D'Anastasio, E. A global database of strong-motion displacement GNSS recordings and an example application to PGD scaling. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2019, 90, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Li, Y.; Shan, X.; Zhu, C. Earthquake Magnitude Estimation from High-Rate GNSS Data: A Case Study of the 2021 Mw7.3 Maduo Earthquake. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhl, C. J.; Melgar, D. ; Grapenthin, R; Allen, R. M. (2017), The value of real-time GNSS to earthquake early warning, Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 8311–8319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, J.; Xu, C.; Li, X. Scaling earthquake magnitude in real time with high-rate GNSS peak ground displacement from variometric approach. GPS Solut. 2020, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgar, D.; Hayes, G.P. Characterizing large earthquakes before rupture is complete. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaav2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgar, D.; Melbourne, T.I.; Crowell, B.W.; Geng, J.; Szeliga, W.; Scrivner, C.; Santillan, M.; Goldberg, D.E. Real-time high-rate GNSS displacements: performance demonstration during the 2019 Ridgecrest, California, Earthquakes. Seismol Res Lett. 2020, 91, 1943–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundakir, I.A.; Mukti, F.Z.; Mauradhia, A.; Fitri, W.; Wibowo, S.T. Ina-CORS Growth Story. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1418, 012027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- InaTEWS Earthquake Repository. Available online: https://repogempa.bmkg.go.id/ (accessed on 17th December 2024).

- Feng, L.; Hill, E.M.; Banerjee, P.; Hermawan, I.; Tsang, L.L.H.; Natawidjaja, D.H.; Suwargadi, B.W.; Sieh, K. A Unified GPS-Based Earthquake Catalog for the Sumatran Plate Boundary between 2002 and 2013. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2015, 120, 3566–3598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Teferle, F.N.; Shi, C.; Meng, X.; Dodson, A.H.; Liu, J. Ambiguity Resolution in Precise Point Positioning with Hourly Data. GPS Solut. 2009, 13, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Meng, X.; Dodson, A.H.; Teferle, F.N. Integer Ambiguity Resolution in Precise Point Positioning: Method Comparison. J. Geod. 2010, 84, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Shi, C. Rapid Initialization of Real-Time PPP by Resolving Undifferenced GPS and GLONASS Ambiguities Simultaneously. J. Geod. 2016, 90, 1221–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Chen, X.; Pan, Y.; Mao, S.; Li, C.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, K. PRIDE PPP-AR: An Open-Source Software for GPS PPP Ambiguity Resolution. GPS Solut. 2019, 23, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global CMT Catalog Search, https://www.globalcmt.org/CMTsearch.html (accessed on 17th December 2024).

- Kautsar, M.A. (Geospatial Information Agency of Indonesia, BIG, Cibinong). Personal Communication, 2025.

- Bao, H., Ampuero, JP., Meng, L. et al. Early and persistent supershear rupture of the 2018 magnitude 7.5 Palu earthquake. Nat. Geosci. 12, 200–205 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Socquet, A. , Hollingsworth, J., Pathier, E., & Bouchon, M. (2019). Evidence of supershear rupture during the 2018 magnitude 7.5 Palu earthquake from space geodesy. Nature Geoscience, 12(3), 192–199. [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Xu, C.; Wen, Y.; Wang, S.; Xu, G.; Zhao, Y.; Yi, L. The 2018 Mw 7.5 Palu Earthquake: A Supershear Rupture Event Constrained by InSAR and Broadband Regional Seismograms. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, W.; Broerse, T.; Kleptsova, O.; Nijholt, N.; Pietrzak, J.; Naeije, M.; Lhermitte, S.; Visser, P.; Riva, R.; et al. A Tsunami Generated by a Strike-Slip Event: Constraints from GPS and SAR Data on the 2018 Palu Earthquake. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2022, 127, e2022JB024191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deputi Bidang Geofisika, Badan Meteorologi Klimatologi dan Geofisika. Standar Operational Prosedur National Tsunami Warning Center (NTWC), 2024.

- Wessel, P.; Smith, W.H.F.; Scharroo, R.; Luis, J.; Wobbe, F. Generic Mapping Tools: Improved version released. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 2013, 94, 409–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).