1. Introduction

Coseismic landslides are a geological event where a rock or soil mass, which is approaching or is already at a critical state, experiences premature sliding triggered by an earthquake [

1]. Coseismic landslides pose immense hazards, sometimes surpassing the damage caused by earthquakes themselves. In recent years, the occurrence of powerful earthquakes worldwide, such as the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake (Ms8.0), the 2010 Yushu earthquake (Ms7.1), the 2018 Indonesia earthquake (Ms7.4), and the 2023 Turkey earthquake (Ms7.8), has drawn significant attention to the evaluation of coseismic landslide susceptibility. This has become a critical and challenging issue in the academic and engineering fields.

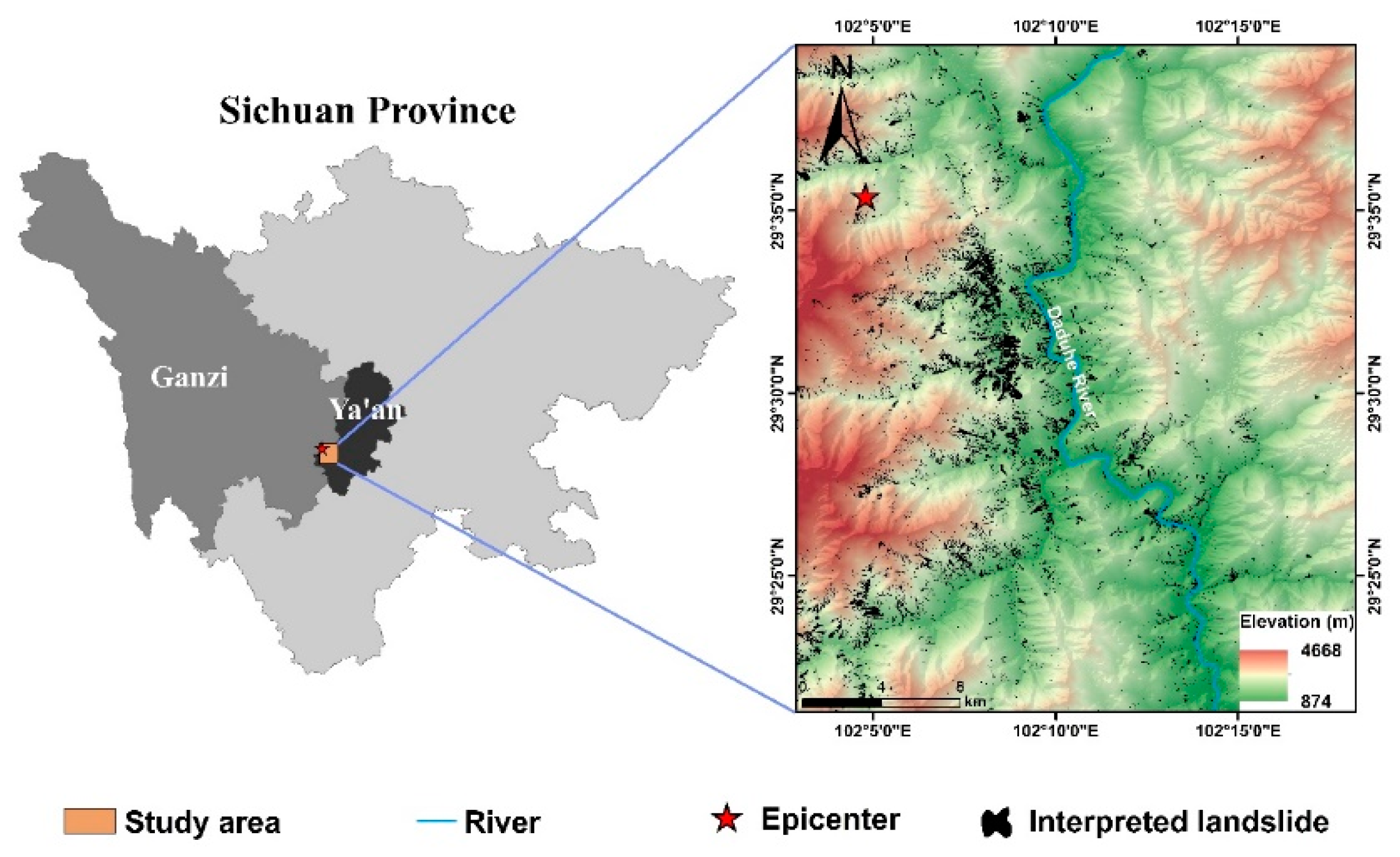

According to the China Earthquake Networks Center (

https://news.ceic.ac.cn/), on September 5, 2022, a magnitude 6.8 earthquake occurred in Moxi Town, Luding County, Ganzi Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan Province, southwestern China. The epicenter was located at 29.59°N, 102.08°E, with a focal depth of 16 km. This earthquake triggered numerous landslides in mountainous areas, resulting in a total of 93 fatalities and 20 people missing, as well as enormous economic losses [

2]. Considering the immense hazards posed by coseismic landslides, conducting a regional analysis of the susceptibility to such events is of vital significance for post-disaster reconstruction and ensuring people’s well-being.

The commonly used methods for analyzing the regional susceptibility to coseismic landslides can be roughly categorized into three types: the engineering geological analysis method, the statistical regression analysis method, and the mechanical analysis method. The engineering geological analysis method is a comprehensive qualitative method based on understanding of slope stability and engineering experience. In the early stages of landslide research, due to the limitations of research methods and the complex geological conditions of slopes, this method was commonly used for evaluation of the seismic stability of slopes [

3]. The statistical regression method is based on analyzing factors that influence the development of coseismic landslides, summarizing regularities, and making predictions. By summarizing the distribution patterns of post-coseismic landslides and studying the relationships between landslides and seismic parameters as well as other influencing factors, the susceptibility trends of coseismic landslides can be extrapolated based on established statistical patterns. Alternatively, semi-quantitative predictions can be made based on expert knowledge, such as comprehensive index methods. Predictive analyses can also be conducted using models such as cluster analysis, information entropy, evidence weight, discriminant analysis, and logistic regression [

4,

5,

6,

7]. However, this method has several limitations: (1) it heavily relies on basic data, and if the inventory of landslides is not comprehensive, the analysis results may have significant errors and cannot be applied to potential seismic source areas; (2) although several factors are considered, they are often not independent of each other; and (3) the lack of consideration of dynamic mechanisms makes the physical significance of the prediction process unclear [

8].

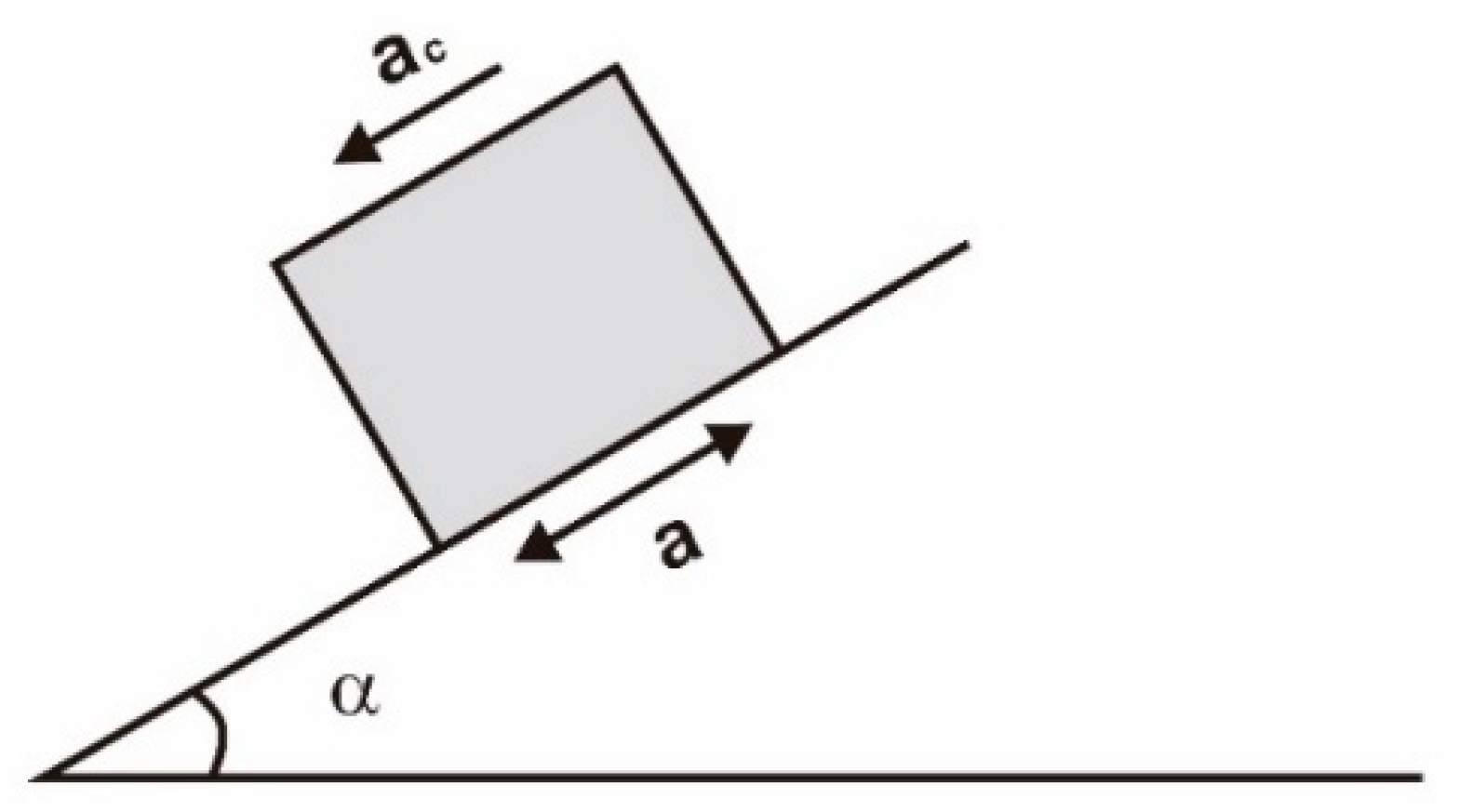

The method of mechanical modeling is based on the principles of mechanics, involving analyzing the instability mechanism and sliding process of slopes to quantitatively characterize mechanical or kinematic parameters. It provides a basis for the analysis of seismic landslide susceptibility, with clear physical significance. Terzaghi first proposed the pseudo-static method [

9]. This method simplifies seismic motion by treating it as a constant body force acting on the potential sliding mass during static limit equilibrium calculations. In this method, the vertical component of the seismic motion is characterized as having a negligible impact on the seismic stability of slopes, so only the horizontal component of the seismic motion is considered. However, this method has some theoretical flaws: (1) the magnitude and direction of the pseudo-static force are constant and unchanged [

10]; (2) the safety factor of the pseudo-static method can only indicate whether the slope is stable and cannot determine whether the slope will fail when the safety factor is less than 1 [

10,

11]; (3) under certain conditions, the minimum safety factor of the circular sliding surface cannot be determined, so the position of the critical circular sliding surface cannot be obtained [

12]; (4) the pseudo-static method only considers the horizontal component of seismic motion and ignores the influence of the vertical component [

13]; (5) the selection of the pseudo-static coefficient lacks a reasonable theoretical basis and can only be determined empirically based on engineering practice [

11]. Clough and Chopra first introduced the finite element method into the analysis of soil dynamic response, marking the introduction of numerical analysis methods into the field of dynamic response analysis of slopes [

14]. However, numerical analysis methods also have certain limitations: they have high computational and time costs, and determining the model scope and boundary conditions is difficult. Therefore, they are commonly used to analyze individual slopes [

8].

Newmark proposed the method of permanent displacement calculation based on the rigid block model, which calculates the permanent displacement of slopes under seismic action, thereby evaluating the stability of slopes under seismic action [

15]. The application of Newmark’s proposed method to multiple strong earthquake records has yielded favorable outcomes, enhancing the validity of this approach for application to individual slopes [

16]. Building upon the foundation of Newmark’s theory, the utilization of a decoupling approximation mindset has addressed the shortcomings of traditional assumptions concerning deep-seated landslides [

17]. Additionally, the implementation of a fully nonlinear decoupled one-dimensional dynamic analysis technique, alongside a nonlinear fully coupled sliding-block model, has further simplified the utilization of this method for seismic displacement prediction [

18]. Subsequently, a simplified methodology was employed to forecast earthquake-induced permanent displacement. This approach utilized a nonlinear fully coupled sliding-block model, integrating critical acceleration, a dominant sliding-block period, and seismic spectral acceleration as contributing factors [

19]. Considering the variability in the natural period observed during the dynamic response of slopes, a unified and streamlined model was developed to enhance the accuracy of predicting earthquake-induced sliding displacements in both rigid and flexible landslide masses [

20].

In a systematic study, Jibson et al. examined using the Newmark method for evaluating regional coseismic landslide susceptibility, focusing on the Oat Mountain area north of the epicenter of the 1994 Northridge earthquake near Los Angeles [

21,

22]. They presented the calculation process of the Newmark method for regional coseismic landslide susceptibility zoning and produced a susceptibility zoning map for the study area. Many scholars have since applied the Newmark method for assessing regional seismic landslide susceptibility. Chen et al. analyzed and predicted potential seismic landslide hazard zones in the Lushan earthquake area in 2013 based on the Newmark model [

23]. Through comparison with actual interpreted landslides, they found the model to be an effective method for predicting coseismic landslides. Similar research was conducted on the 2014 Ludian earthquake, further confirming the validity of the methodology [

24]. Wang et al. proposed a rapid assessment method for seismic landslide hazards based on a simplified Newmark displacement model, taking the heavily affected area of the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake as an example [

25]. They conducted a rapid assessment of seismic landslide hazards in the area, demonstrating the reliability of the method through comparisons with post-earthquake landslide results. Zhang et al. constructed a new model for evaluating seismic slope stability considering the influence of velocity pulse seismic motion on permanent displacements, based on the Newmark model established by Jibson [

26,

27]. The model has the potential to measure the probability of shallow slope failure during future earthquakes in a range from very low to very high by generating seismic landslide hazard maps for near-fault regions. Zang et al. developed an improved model based on the Newmark model, considering the joint roughness coefficient (JRC) and unconfined compressive strength (JCS) of rock joints [

28]. They compared the improved model with the traditional Newmark model using the distribution of landslides induced by the 2014 Ludian earthquake, finding that the improved model had a better fit with the actual landslide distribution. Liu et al. carried out a rapid assessment of coseismic landslides induced by the 2022 Luding earthquake using the Newmark method, delineating hazardous areas and providing recommendations for post-earthquake disaster prevention and mitigation [

29]. This study also validated the effectiveness of the Newmark cumulative displacement method in rapid assessment of coseismic landslides.

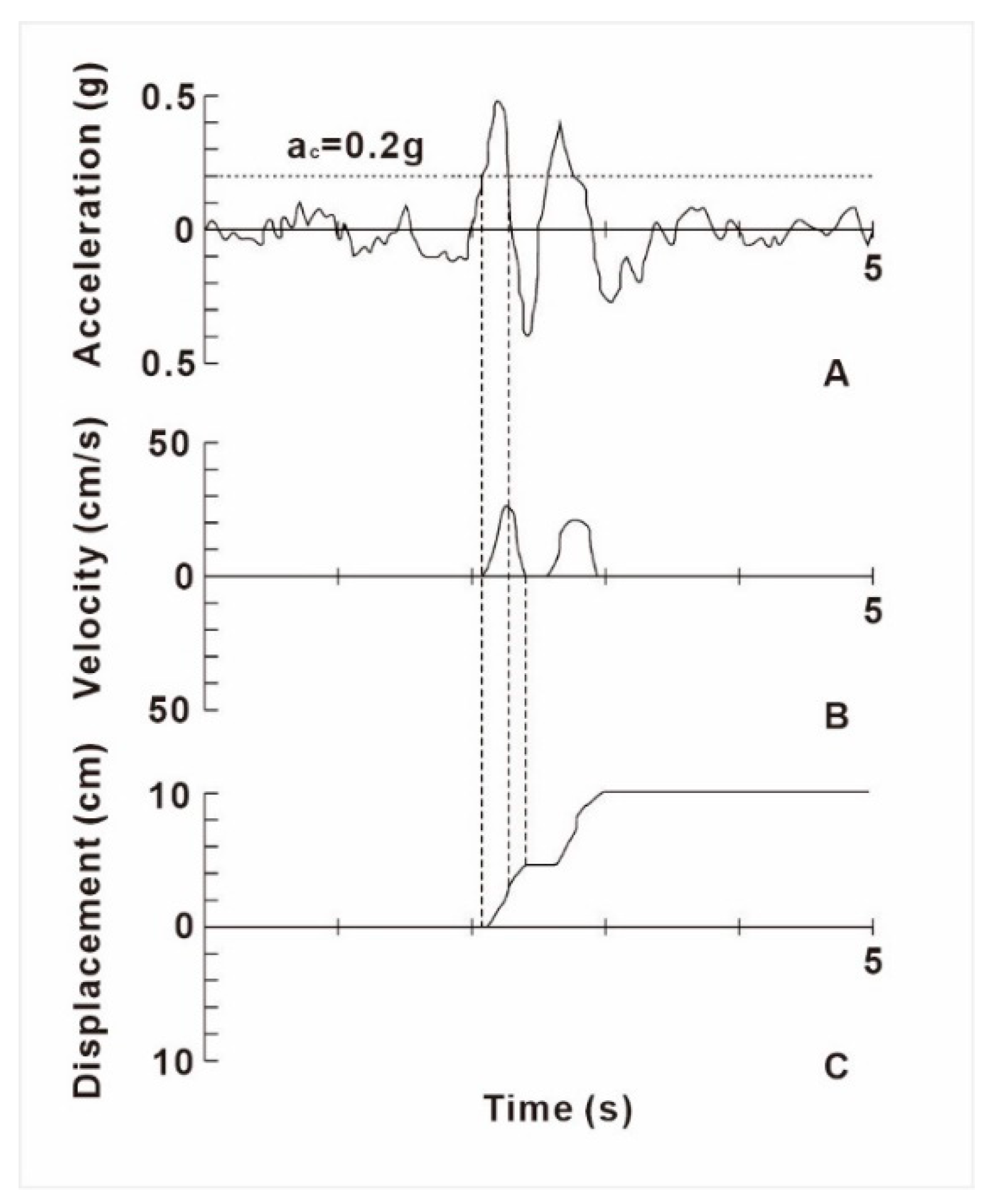

In the Newmark method, the permanent displacement value is obtained by integrating the time during which the seismic acceleration exceeds the critical acceleration of the slope [

15]. In the regional analysis process, it is often necessary to rasterize the study area using GIS techniques. Therefore, it is not practical to calculate the permanent displacement values for each grid cell using the standard Newmark method. To address this issue, some scholars have studied the relationship between Newmark permanent displacement and seismic motion parameters, establishing simple and practical mathematical regression models for rapid prediction of seismic landslide susceptibility in regional analysis. Ambraseys and Menu were the first to conduct such research [

30]. They selected 50 sets of strong ground motion records from 11 earthquakes and proposed a relationship between Newmark permanent displacement

and the ratio of slope critical acceleration

to PGA. Jibson (1993) proposed a relationship between

and Arias intensity (

),

based on 11 strong earthquake records. Later, in 1998 and 2000 (Jibson et al. 1998, 2000), this formula was improved using 555 strong earthquake records from 13 seismic events[

21,

22,

31]. However, the majority of the selected earthquake data in this model had relatively small peak ground acceleration, leading to distorted results when the critical acceleration was larger. Therefore, Jibson selected 2,270 strong earthquake records from 30 global seismic events and fitted regression formulas for displacement with different combinations of seismic motion parameters [

27]. Subsequently, several scholars derived displacement regression formulas with various parameter combinations based on different seismic motion records, such as

, the ratio of

to PGA, PGA, peak ground velocity (PGV), and

[

32,

33,

34,

35]. These regression formulas facilitate the use of the Newmark model in the susceptibility assessment of coseismic landslides. However, some issues should be addressed. The determination of these regression formulas is specific to certain geological backgrounds and particular seismic events. Therefore, their applicability should be validated rather than solely considering the number of factors or the size of the database.

We obtained a comprehensive inventory of landslides caused by the 2022 Luding earthquake. In this paper, we will summarize six types of displacement regression models, choosing the best-fitting model by comparing the predicted displacement with the inventory of actual landslides. The impact of parameters on the fitting of regression models is also explored. Finally, a hazard map of landslides posed by the Luding earthquake is provided using the best-fitting regression model.

5. Discussion

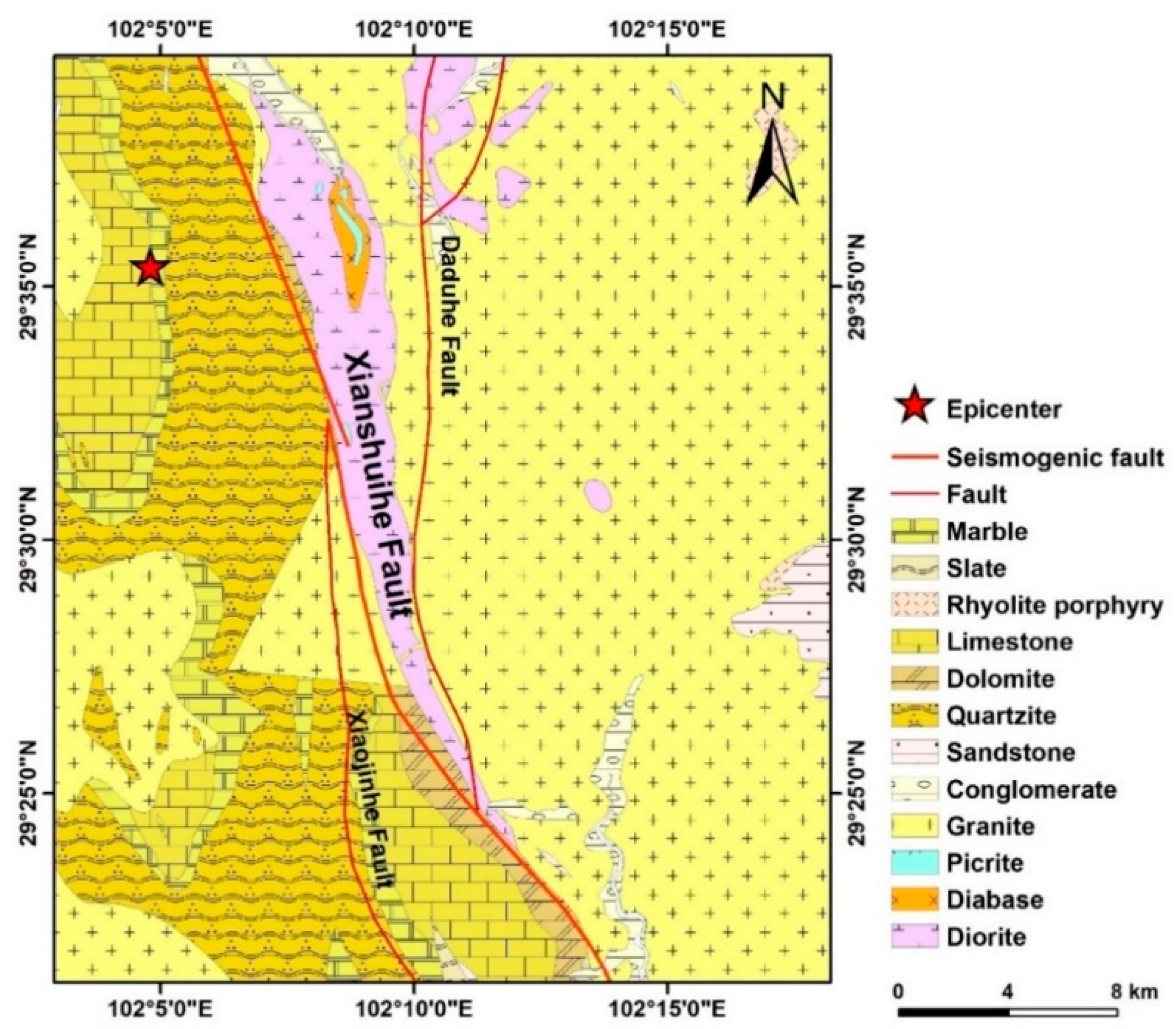

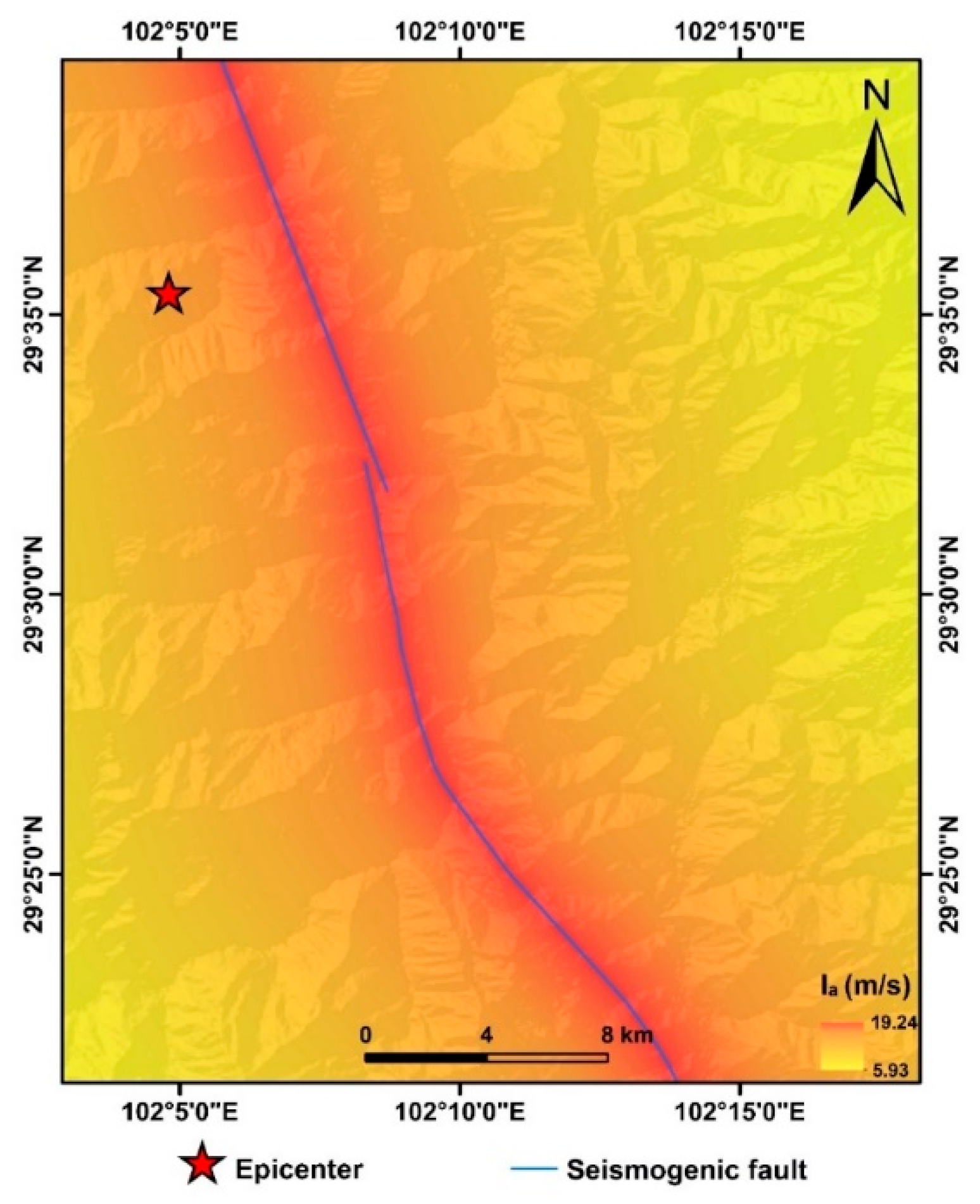

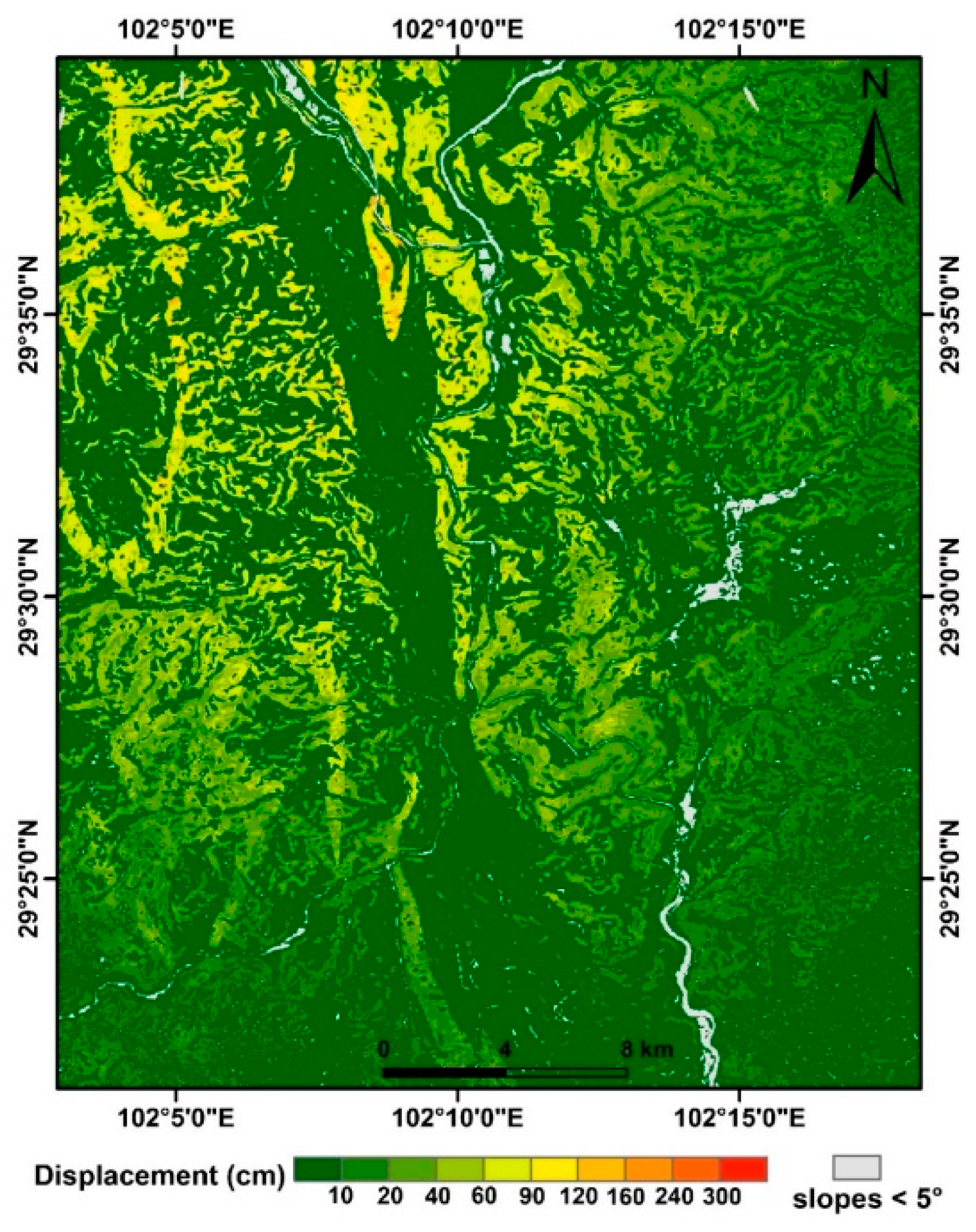

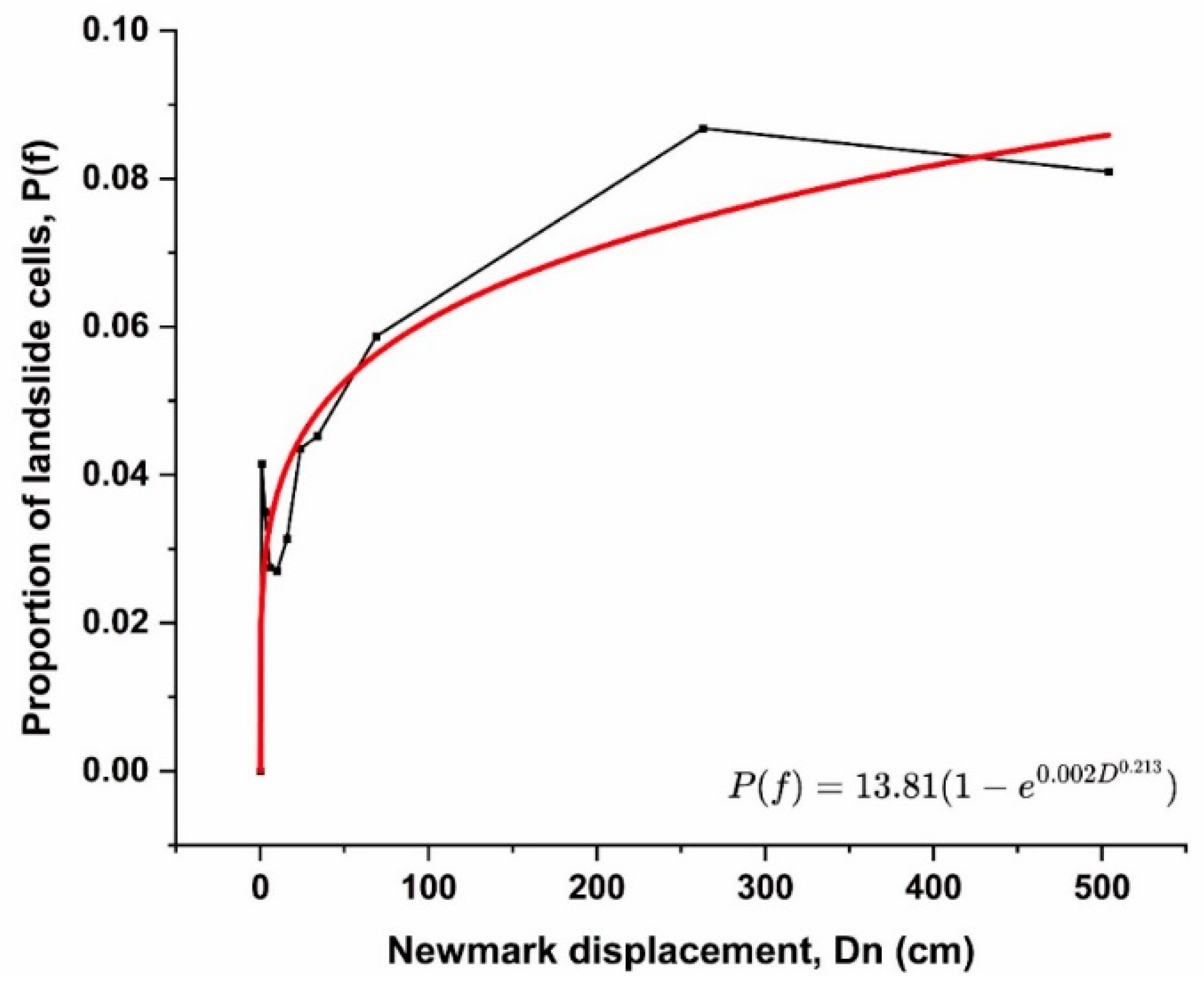

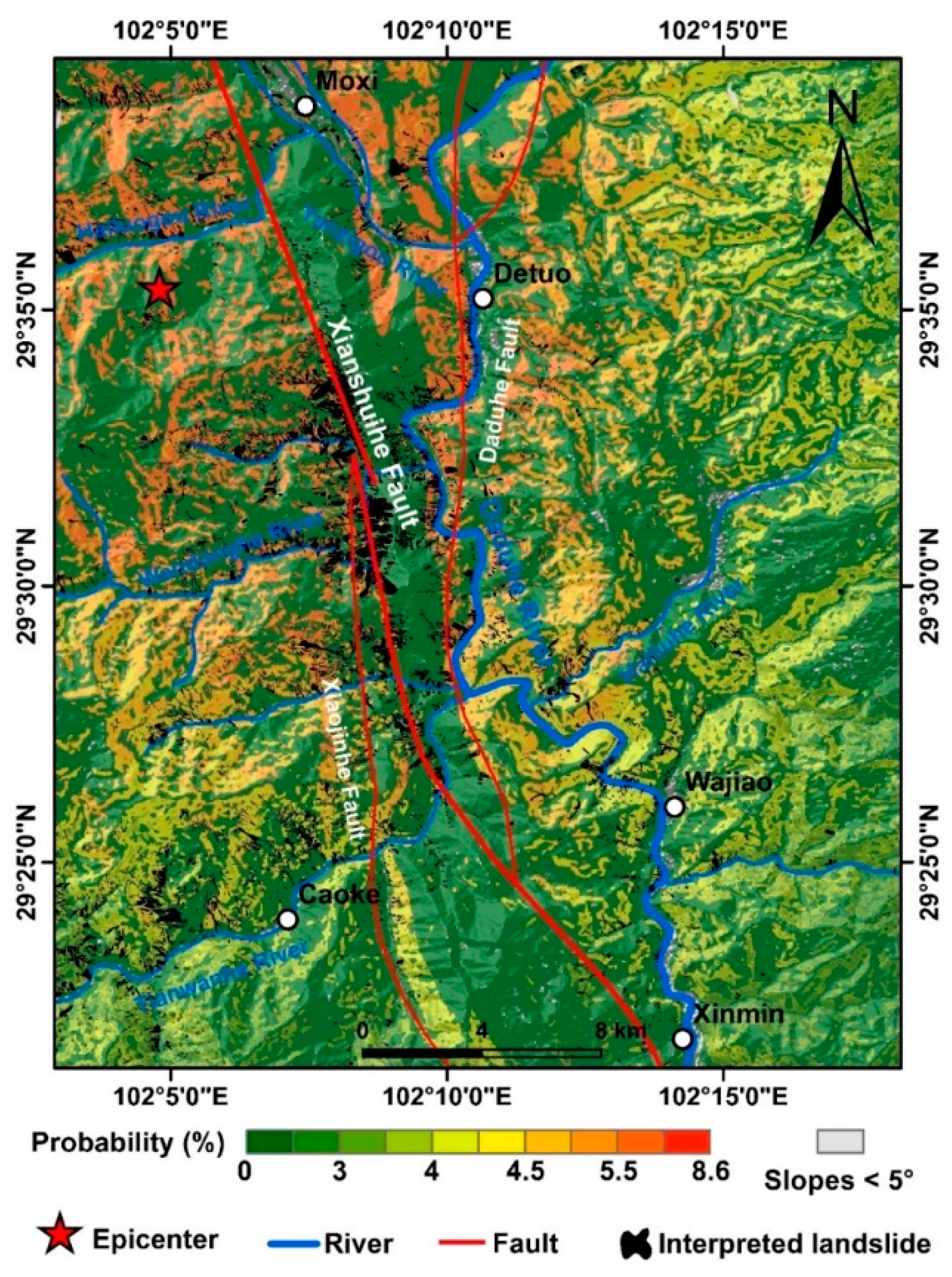

Figure 13 shows that the higher probability areas of coseismic landslides are mainly located at Moxi and Detuo. The overall northwestern part of the study area poses a greater hazard of coseismic landslides compared to the southeastern part, which is consistent with the findings of Liu et al. [

29]. The higher probability areas, where landslides are prone to occur, are concentrated along the Xianshuihe fault belt (

Figure 13), which indicates that the seismogenic fault plays an important role in determining the spatial distribution of coseismic landslides [

42]. The higher probability areas of coseismic landslides are also concentrated in steep slopes on both sides of the Daduhe, Yanzigou, Hailuogou, and Wandonghe river valleys (

Figure 13). Greater slope gradients significantly increase the occurrence of coseismic landslides.

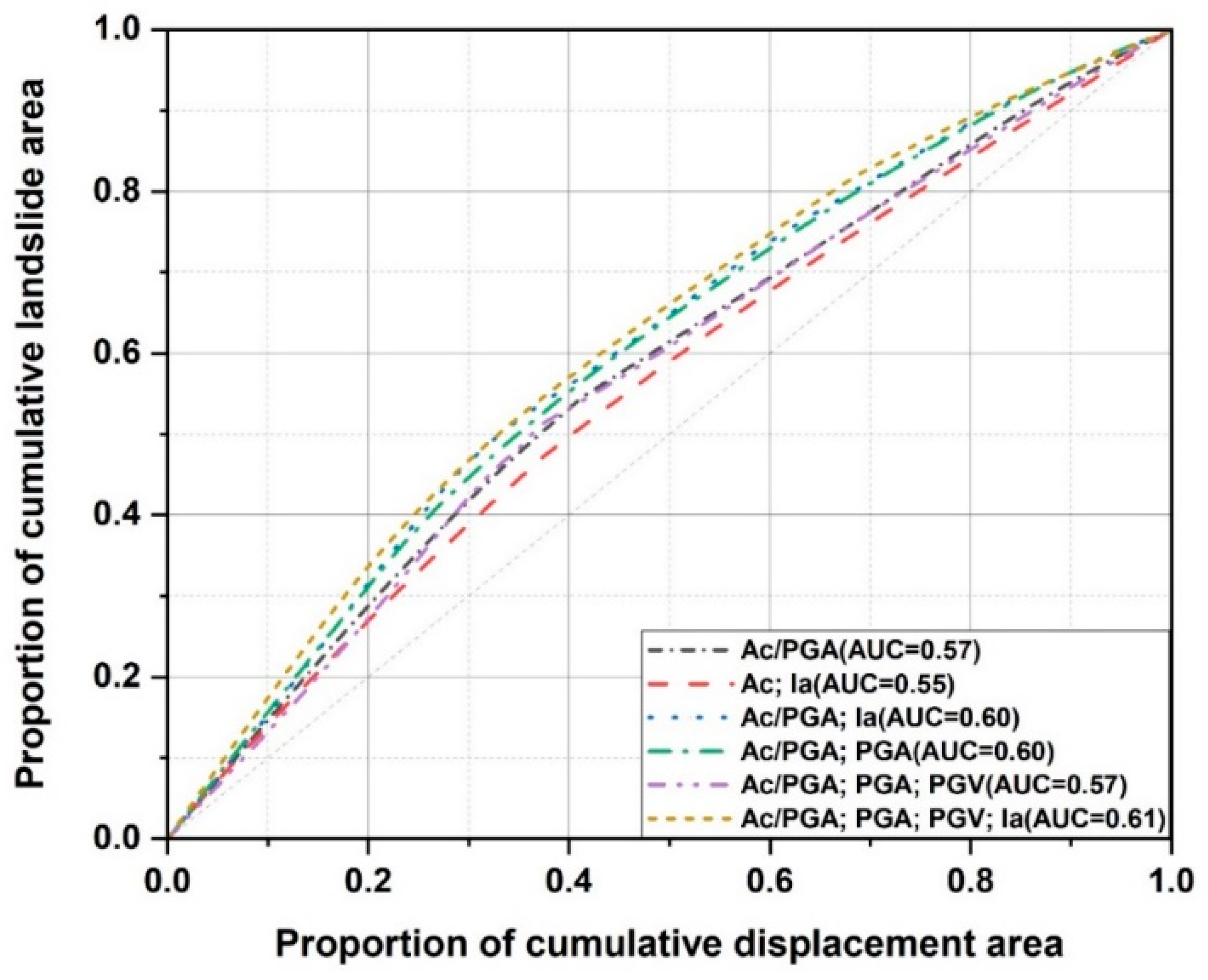

Among the six different regression models, the model proposed by Saygili et al. [

32], which utilized AR,

,

, and

, achieved the highest AUC value and exhibited good fit with the distribution of landslides induced by the 2022 Luding earthquake. However, this is not solely attributed to the number of seismic parameters used in the model, as Saygili et al. achieved an AUC value of 0.57 with their three-parameter model (AR,

, and

), whereas Xu et al. obtained an AUC value of 0.60 with their two-parameter model (AR and

), which is higher than Saygili’s three-parameter model [

32,

34]. Therefore, the number of seismic parameters in the model is not the primary factor contributing to its good fit with actual landslides. This study suggests that the reason behind the good fit of the four-parameter model lies in the correlation between the distribution of

and

(

Figure 8A and B) with the epicentral distance, as well as the correlation between the distribution of

(

Figure 9) and the distance to seismogenic fault. Similarly, Xu et al. (2012) achieved the second-highest AUC value with their two-parameter model (AR and

), which also incorporated

and

[

34]. Both models considered the influence of epicentral distance and the distance to seismogenic fault on seismic parameters, resulting in a good fit with the actual distribution of coseismic landslides. Therefore, it can be indicated that considering both epicentral distance and the distance to seismogenic fault when incorporating seismic parameters in the Newmark model has a favorable impact on the prediction results.

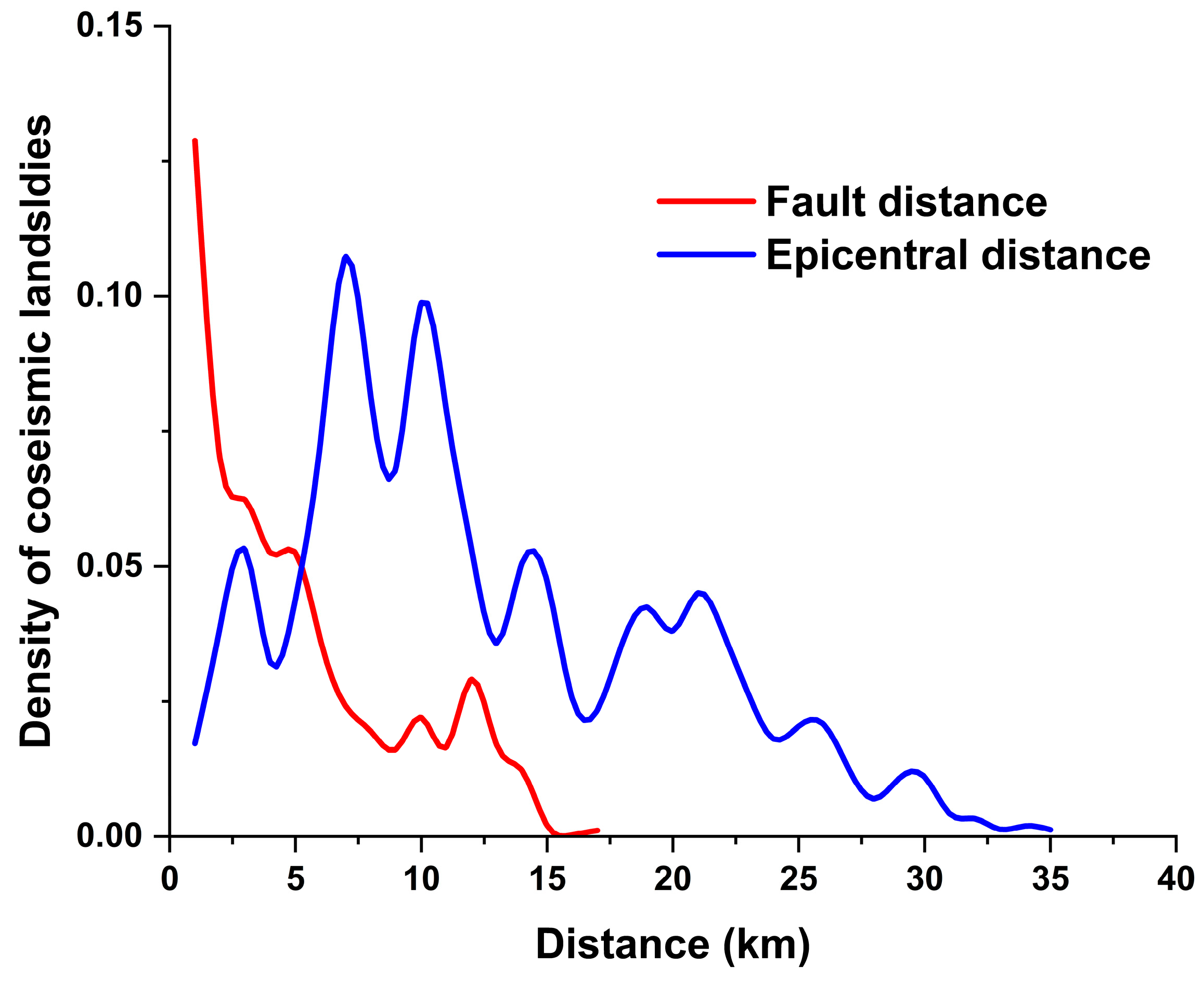

To enhance our understanding of the influence exerted by epicentral distance and the distance to seismogenic fault on the spatial distribution of seismic landslides, we conducted a comparative study.

Figure 14 shows that the density of coseismic landslides reaches its peak near the Xianshuihe fault, followed by an approximately monotonic decrease as the distance to seismogenic fault increases. When the distance to seismogenic fault reaches 15 km, the density of coseismic landslides nearly diminishes to zero. Conversely, landslides are seldom distributed in the vicinity of the epicenter, with their prevalence peaking as the epicentral distance extends to 7 km. Subsequently, the density of coseismic landslides exhibits a fluctuating decrease with further increases in epicentral distance, ultimately approaching zero at an epicentral distance of 35 km. It is deduced that when the predicted region encompasses or is in close proximity to the seismogenic fault, precedence should be given to the influence of the distance to seismogenic fault, followed by the impact of the epicentral distance. Conversely, when the predicted region is situated far from the seismogenic fault, the fault’s influence on coseismic landslides becomes less pronounced. In such instances, the distribution density of coseismic landslides is primarily influenced by the epicentral distance, with additional considerations required for factors such as lithology and topography.

In the study by Jin et al., a comparison between Eq. 5 and Eq. 7 was conducted using data from the 2013 Lushan Ms7.0 earthquake [

35]. It was found that Eq. 5 exhibited a significantly smaller root mean square error compared to Eq. 7. However, in the present investigation, Eq. 5 yielded the lowest AUC value of 0.55, diverging from the findings reported by Jin et al. This discrepancy can be attributed to the approach employed by Jin et al., where Eq. 5 was fitted to the seismic records by inputting

values within the range from 0.01 to 0.15 in increments of 0.01. The model coefficients were subsequently readjusted based on these standardized values. Notably, this process overlooked the consideration of region-specific critical accelerations influenced by lithology and topography. In contrast, our study validated the model results using the actual distribution of landslide occurrences, resulting in outcomes differing from those reported by Jin et al.. Consequently, it is recommended that future coseismic hazard assessments employing the Newmark method should involve the refitting of model coefficients based on historical earthquake data specific to the study area. Subsequent displacement predictions using the revised model are crucial for obtaining accurate and region-specific results.

When computing permanent displacement using the Newmark displacement regression formula Eq. 4 in a regional analysis, only the grid cell where

is greater than

is taken into account. This precaution is taken due to the model’s formula violating mathematical laws, resulting in a negative value in the logarithmic component when considering the grid cell where

exceeds

(

Table 3). However, this rationale is consistent with the principles of the Newmark method. As the Newmark displacement originates from the double integration of the segment where

exceeds

[

15], the following question arises: should a similar procedure be applied when employing alternative Newmark displacement regression formulas for regional analysis, focusing solely on grid cells where

surpasses

? To address this question, we conducted a comparative analysis using the Newmark displacement regression formula with the highest degree of fit (Eq. 9). In one scenario, calculations were performed exclusively for grid cells in the region where

exceeds

, assuming stability and no sliding for other grid cells. In the second scenario, computations were carried out for all grid cells in the region, regardless of whether the

in a particular grid cell exceeded

or not. Simultaneously, the magnitude of the AUC values was employed to compare the accuracy of the two calculation methods. The results indicated that when exclusively considering the grid cells where

is smaller than

, the resulting AUC value was 0.6094, whereas, without imposing this condition, the model yielded an AUC value of 0.6092. It can be deduced that this condition exerts a negligible impact on the overall calculation. Nevertheless, in practical coseismic landslide occurrences, some landslides do take place in the grid cells where

exceeds

. Although the calculated displacement values for these grid cells in the theoretical model are relatively small, they still pose a certain level of hazard. Relying solely on calculations that consider the grid cells where

is greater than

might not accurately predict hazardous areas. Therefore, it is advisable to omit this condition when utilizing Newmark displacement regression models for calculation to obtain more comprehensive and reliable results.

As mentioned in the introduction section, statistical analysis is also an important method for assessing the susceptibility of coseismic landslides. Previous studies have shown that slope gradient and the distance to seismogenic fault are two important factors influencing the distribution density of coseismic landslides [

42,

43]. Research conducted by Jibson et al. has demonstrated that the Newmark modeling procedure is slope-driven [

21,

22]. Consequently, the Newmark method adeptly delineates the impact of slope gradient on the spatial distribution of coseismic landslides. The study presented in this paper demonstrates that the epicentral distance and the distance to seismogenic fault can influence the predictive performance of the Newmark method, thereby affecting the accuracy of coseismic landslide susceptibility assessments. Constrained by the seismic parameter data obtained, the distribution of

and

appears in concentric circular shapes, without reflecting the influence of the seismogenic fault. This somewhat diminishes the impact of the distance to seismogenic fault on the Newmark method, resulting in a decrease in the AUC value. Continuous improvement in subsequent research endeavors is required to address this limitation. Furthermore, the study area selected in this paper does not revolve around the epicenter but rather centers on the seismogenic fault. Additionally, efforts were made to encompass as many interpreted coseismic landslides as possible. However, this approach may not objectively reflect the influence of epicentral distance on the assessment outcomes of coseismic landslide susceptibility, thus contributing to the relatively modest AUC values observed. From the foregoing discussion, it is evident that the selection of fundamental data such as terrain and seismic parameters significantly impacts the assessment accuracy of the Newmark method. This amplifies the complexity of its application and underscores the need for dedicated analysis and special consideration in future applications.

6. Conclusion

This study conducted a susceptibility assessment of coseismic landslides triggered by the 2022 Luding Ms6.8 earthquake using six different Newmark displacement regression models and explored the factors affecting the applicability of the models. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) The 2022 Luding earthquake induced 13,759 landslides within an area of 964.8 km2. These landslides were predominantly concentrated along steep mountain slopes on both sides of the fault and in the valley area on the right bank of the Daduhe River. The prediction outcomes designate Moxi Town, Detuo Town, both sides of the Daduhe River, Wandonghe River, Hailuogou River, and Yanzigou River as high susceptibility areas for coseismic landslides.

(2) The model composed of seismic parameters such as AR, , , and demonstrates a commendable fit to the distribution of coseismic landslides. Conversely, models that solely account for and yield unsatisfactory fitting results. Consequently, when employing the Newmark displacement method for susceptibility assessment of coseismic landslides, it becomes imperative to validate the fitting formula, taking into account the specific geological and environmental conditions.

(3) In the proximity of the fault, priority should be given to considering the influence of distance to seismogenic fault and epicentral distance when assessing the susceptibility of coseismic landslides. However, when situated far from the fault, the impact of distance to seismogenic fault on landslides diminishes. In such cases, attention should be directed towards factors like epicentral distance, topography, and lithology, which become more significant in influencing susceptibility.