Introduction

Maternal health and nutrition are critical to preventing morbidities for both the mother and her child [

1]. In South Africa, 70% of reproductive-aged women are overweight, almost 50% are hypertensive, 30% are anemic, and one-third of children <5 years old are considered clinically stunted [

2]. South Africa, like many countries in Africa, has significant economic disparities. The South African General Household Survey conducted in 2021 indicated that 21% of households had inadequate access to food, with two-thirds of affected households being in urban areas [

3]. It has also been estimated that ~50% of the general South African population was consuming low nutritional diversity meals, with diets based predominantly on starches [

4].

It is well established that diet is a driving factor in gut microbiome composition and function [

5,

6], and short-term dietary interventions have been shown to impact the gut microbiome rapidly [

7,

8,

9]. The gut microbiome is also known to impact systemic inflammation [

8,

9], an underlying cause of many non-communicable diseases in mothers. Chronic inflammation has also been associated with stunting in infants [

10]. Thus, a key question is whether diet modification using locally acceptable fermented foods is an avenue to improve nutrition and systemic inflammatory status in both lactating South African mothers and their infants.

Throughout human history, fermentation has served to preserve and process foods, and there is a growing realization that fermented foods have both nutritional and other health benefits [

8,

11,

12,

13]. Transforming original food substrates through fermentation leads to an extended shelf-life, the formation or increase of bioavailable end-products, including vitamins, amino acid derivatives and organic acids, and may remove or reduce food toxins [

14]. This serves important purposes in regions like Southern Africa where food security is low and access to refrigeration, electricity, and running water is limited [

3]. Significant associations have been reported between the consumption of fermented food and clinical outcomes, including improved weight maintenance [

11], reductions in the risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, gestational diabetes, and overall mortality [

12,

13]. These studies were however primarily conducted in the global North, while data from Africa is scarce. Meanwhile, observational and interventional studies found fermented food consumption to have beneficial impact on the gut microbiota and immunity [

8,

15]. In agreement, a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial (RCTs) that evaluated the effect of fermented foods consumption on systemic inflammation found that fermented food intake decreased tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, a common biomarker of inflammation [

16].

As fermentation is widely practiced in Southern Africa as a household-level technology to preserve foods, a highly fermented food diet is likely to offer a culturally acceptable and easily implementable intervention to improve maternal health outcomes. Mageu is a fermented, non-alcoholic cereal-based sour porridge, popular throughout Southern Africa [

17,

18,

19]. Traditional preparations of mageu include boiling to make a maize-porridge with a natural inoculum source, such as wheat, subsequently added to initiate fermentation with bacteria including

Lactobacillus delbrueckii,

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum,

Streptococcus thermophilus, and

Lactococcus lactis [

20]. Knowledge of traditional recipes of mageu are common in older generations, while nowadays large commercial production of mageu exists in Southern Africa [

21]. However, commercial mageu is pasteurized, which increases the shelf-life of the product further but also reduces the viability of the live organisms that were present during fermentation [

21]. It is unclear whether the consumption of fermented foods that contain live microorganisms at the time of consumption would be superior to consumption of pasteurized fermented foods (without viable organisms) on long-term health benefits, and the gut microbiota and inflammatory status of consumers.

As most clinical evidence for fermented food’s impact on health come from high-income countries, we tested the hypothesis that fermented mageu improves gut microbiota in a pilot RCT among postpartum, lactating South African mothers. We compared gut microbial changes, nutritional metrics, and systemic inflammation between lactating postpartum mothers consuming unpasteurized, live-culture mageu (LCM, developed as part of this project) versus pasteurized, store-bought mageu (SBM) versus no mageu for 6 weeks.

Methods

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the University of Cape Town Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC 004/2022), the South African Health Product Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA ref 20220305) and registered on the South African Clinical Trials Registry (DOH-27-072022-6097, registration approved on 27 July 2022). The trial was implemented in accordance with ICH E6 and South African Good Clinical Practice (GCP). All women provided written informed consent.

Interventional product preparation: LCM was produced by the Centre for Bioprocess Engineering Research (CeBER) at the University of Cape Town, in line with the regulations stipulated in South African National Standards (SANS) 1199:2011 “The production of mageu”. For each batch, a 10 wt% maize-meal in water suspension was prepared and cooked at 90-100°C for 15 minutes. The porridge was cooled to 35-40°C, after which wheat flour was added as the inoculum source (10g: 1L porridge). The LCM taste was also adapted at this point using sugar (20g : 1L porridge), so that the final product matched the SBM flavor (Number 1 Mageu Cream Flavor, RCL FOODS, Westville, South Africa) and nutritional properties as closely as possible. The porridge was fermented at 37°C for 48 h. The quality and nutritional characteristics of the final product were externally verified through an accredited nutritional, microbial and pathogen testing laboratory (Microchem Specialised Lab Services, South Africa).

Interventional product quality control: Quality control evaluations were performed for each batch of LCM and SBM according to SANS 1199:2011. Mageu dilutions were spread onto MacConkey agar plates (Millipore HG00002.500, made according to manufacturer’s instructions), incubated aerobically for 24 hours at 37°C and assessed for the presence of

Escherichia coli. To identify anaerobic spore-forming bacteria (

Clostridium spp.), mageu dilutions were incubated at 80°C for 12 minutes and then plated onto supplemented Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) agar (37g/L BHI, 5g/L yeast extract, 0.5g/L cysteine-HCL, 5mg/L haemin, 1mg/L menadione and 15g/L agar) and incubated anaerobically for 48 hours at 37°C. Bacterial colonies were subcultured onto fresh BHI agar plates at 37°C for 24 hours aerobically to distinguish between

Clostridium spp. versus aerobic spore formers. Colonies of interest on MacConkey agar and oxygen-sensitive colonies on BHI agar were counted to determine the number of colony forming units (cfu/ml). Colonies were typed by PCR and sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene. A previously described colony PCR protocol [

22] was used with the universal 16S rRNA gene primers 27F and 1492R [

23]. Products were Sanger sequenced (Inqaba Biotec) using the 907R primer and the resulting sequences classified by comparing to the NCBI 16S rRNA gene database using the BLAST algorithm [

24].

Study participants: Mothers were recruited between June 2022 – June 2023 from the Midwife Obstetric Unit in Khayelitsha, an informal settlement in urban Cape Town, South Africa. Maternal eligibility criteria included having had a negative HIV test in the past six weeks, age between 18 and 50 years, electing to breastfeed, access to a refrigerator and electricity at home, willing and able to consent and be randomised, and having delivered at full term, average for gestational age birth weight infant within the past 10 days. Exclusion criteria included complications during pregnancy and delivery (i.e. gestational diabetes, body mass index [BMI] > 40 prior to pregnancy, chorioamnionitis or eclampsia), active tuberculosis or other infectious diseases, or administration of antibiotics, commercial probiotics, prebiotics, or immunoregulatory products. A screening questionnaire was administered to assess maternal fermented food consumption, and women who had consumed >5 servings of fermented foods in the week prior to delivery were excluded. Based on previous work [

8], serving sizes of the items included in the questionnaire were set as follows: mageu, amasi (a milk based traditional fermented food), buttermilk and yoghurt: 1 serving = 250ml/g; atchar (pickles): 1 serving = 62.5ml/45g, homemade fermented porridge: 1 serving = 250ml/g and traditional/home brewed beer: 1 serving = 250ml. Administration of the screening questionnaire involved showing potential participants a picture card of each item and asking them whether they had consumed it in the week prior to giving birth. The amount of indicated items consumed was quantified by determining the frequency consumed in that week, and the typical serving size, which was then converted to a total number of servings consumed per week. Quantification of serving sizes was done using applicable line sketches and actual containers.

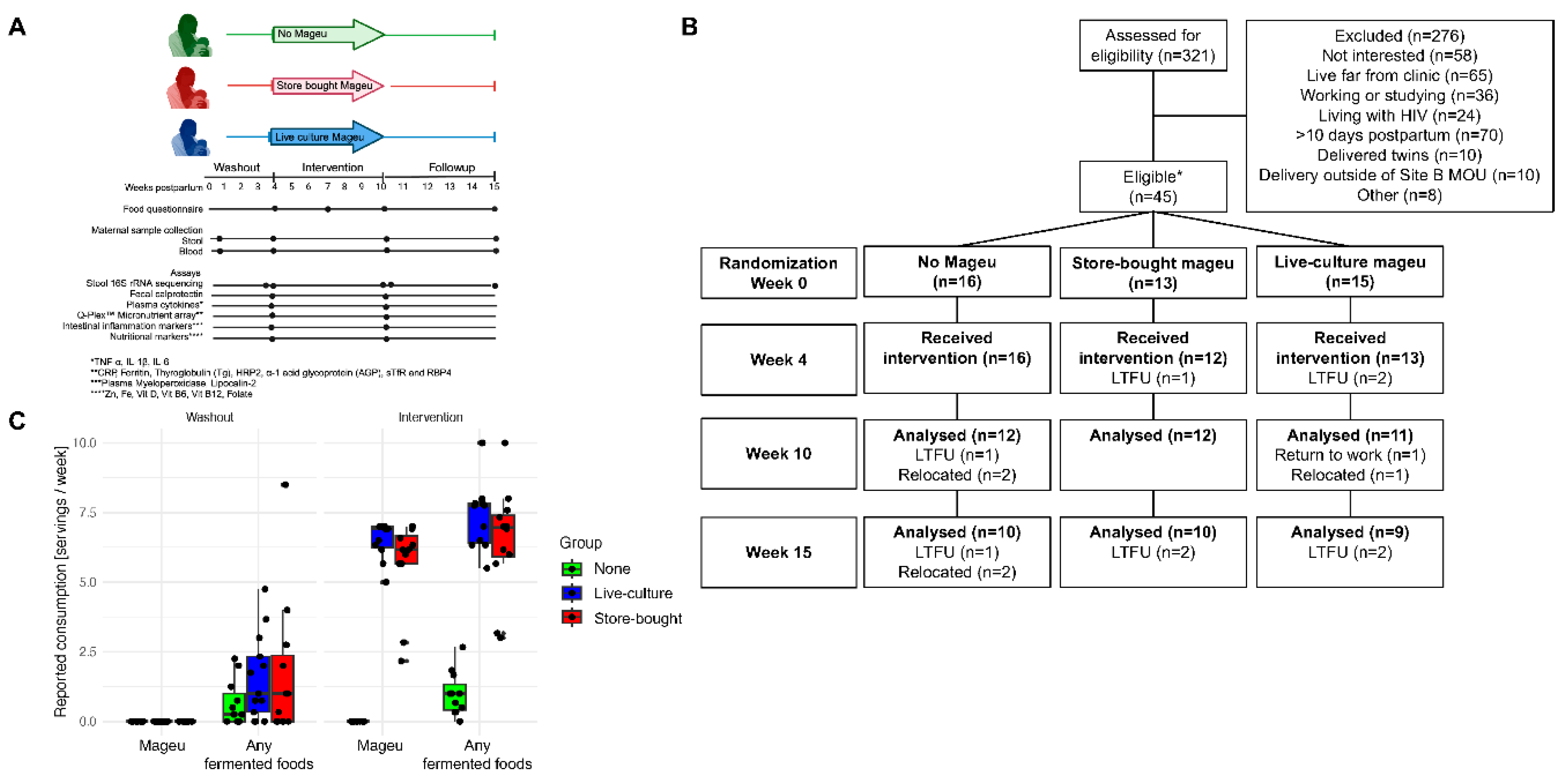

Randomization and masking: At enrollment, women were randomly assigned 1:1:1 to the SBM, LCM, or no mageu group. Participants were assigned using the Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) function “randomize”, and the randomisation list was issued to the pharmacist. Participants were blinded to the allocated intervention arm, except for the no mageu arm. All personnel involved in clinical and laboratory testing and investigators were masked to group assignments, except for the dietitians analysing the dietary data and pharmacists.

Study procedures: At the enrollment visit, all women were requested to refrain from consuming mageu and other fermented foods for a 3-week washout period (including consumption of <500ml of amasi, yoghurt, or buttermilk per week). All women also received dietary counseling to maintain quality protein and calcium intake throughout the study. Information was collected about maternal socioeconomic and demographic indicators, household food insufficiency and insecurity, and dietary intake. Data were entered directly into standardized case report forms on a REDCap database [

25]. A physical exam was performed, including weight and height measurements. All women were encouraged to exclusively breastfeed their infants for 6 months, in accordance with the current World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines [

26]. At 4 weeks postpartum, women returned to the clinic for sample collection and questionnaires, and to receive their randomized intervention (either SBM, LCM, or no mageu). The mageu arms were blinded as to type of mageu women would be receiving, and women were instructed to consume one bottle of 500 ml daily for 6 weeks. Women in the no mageu group were instructed to continue their regular diet. All women were counseled about appropriate caloric intake, to ensure that the addition of mageu to their diets did not result in increased calorie intake and weight gain, and to continue consuming no more than 500 ml of amasi/yoghurt/buttermilk per week and to refrain from the consumption of other fermented foods for the duration of the study. Since the shelf life of opened SBM was four days (as per manufacturer’s instructions, SBM was opened to transfer to fresh packaging as part of blinding protocol), a 3–4-day supply was provided to each participant randomized to SBM and LCM. Twice weekly, the study driver delivered the next few days’ mageu directly to participants’ homes at 4°C. Participants were asked to store the mageu in their household refrigerators. Additional clinic visits were at 7 weeks, 10 weeks (end of 6-week intervention), and 15 weeks (5 weeks post-intervention).

Monitoring of intervention: To monitor compliance with the intervention (mageu intake yes/no and if yes, amount), as well as daily intake from 10 food groups, participants completed daily monitoring sheets for the duration of the 6-week intervention. Participants were trained to mark food groups from which items had been consumed using a food photograph guide developed for these purposes. The 10 food groups were aligned with the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) food group guide for the calculation of dietary diversity for adult women [

27] and included: grains, roots and tubers, pulses, nuts and seeds, dairy, flesh foods, eggs, dark green leafy vegetables, other vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables, other vegetables, and other fruit. Dietary diversity was calculated as a score out of 10 as stipulated by the FAO (2021). Monitoring sheets were reviewed at weeks 7 and 10 by the dietitian to assess adherence. Additional measures of adherence included pharmacy bottle returns.

Clinical assessments: At each visit, maternal health outcomes, including adverse events, were collected using standardized case report forms. The study clinician assessed adverse event severity and relatedness using the DAIDS Table for Grading the Severity of Adult and Pediatric Adverse Events, Corrected Version 2.1 [

28]. Maternal height and weight were measured at each time point to calculate BMI. The use of concomitant medication was captured on daily monitoring sheets.

Nutritional assessments: Dietary assessment for estimation of total energy, macronutrient (carbohydrates, protein, fat), fiber, and micronutrient (minerals, antioxidant compounds, and B vitamins) intake involved three face-to-face 24-hour recalls administered using the multiple pass method [

29] at weeks 4, 7 and 10. Serving size was estimated using a booklet adapted from the Dietary Assessment and Education Kit [

30]. The 24-hour recall data was analyzed using the South African Food Composition Tables [

31]. The three 24-hour recalls were used to calculate the mean energy and nutrient intake adjusted for intra-person variability using the IOM method [

32] over the 6-week intervention period.

Specimen collection: At each visit stool samples from women were collected in sterile specimen collection cups. The stool samples were transported to the laboratory at 2-8°C and stored at -80°C. Six mL of maternal whole blood was collected at matching time points both in Sodium Heparin (NaHep) and Serum Separator (SST) tubes. The whole blood was centrifuged at room temperature for 10 min at 344 × g, aliquoted and plasma and serum stored at -80°C for testing of inflammation and nutritional biomarkers.

Nucleic acid extraction, 16S rRNA gene amplification and sequencing of mageu and maternal stool: DNA was extracted from 400 µl of mageu stored in a 1:1 ratio in Primestore® MTM (Longhorn Vaccines & Diagnostics LLC, Bethesda, US) and from 200 mg of dry maternal stool collected at weeks 4, 10 and 15, using the DNeasy Powersoil Pro kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s protocol, with mechanical disruption by bead-beating at 50 Hz for 10 minutes (Qiagen TissueLyser LT, Hilden, Germany). Positive controls (bacterial mock community HM-280, BEI) and negative controls (nuclease-free water) were included for cross-contamination filtering and error rate modelling. DNA was amplified in triplicate using primers designed to span the V3-V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene (357F/806R), as described previously [

33]. Amplicon libraries were purified using AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter), quantitated via Quant-iT dsDNA High Sensitivity Assay (ThermoFisher, Waltham, US), and pooled in equal mass quantities. Paired-end sequencing was performed on an Illumina Miseq platform using V3 600 cycle kits.

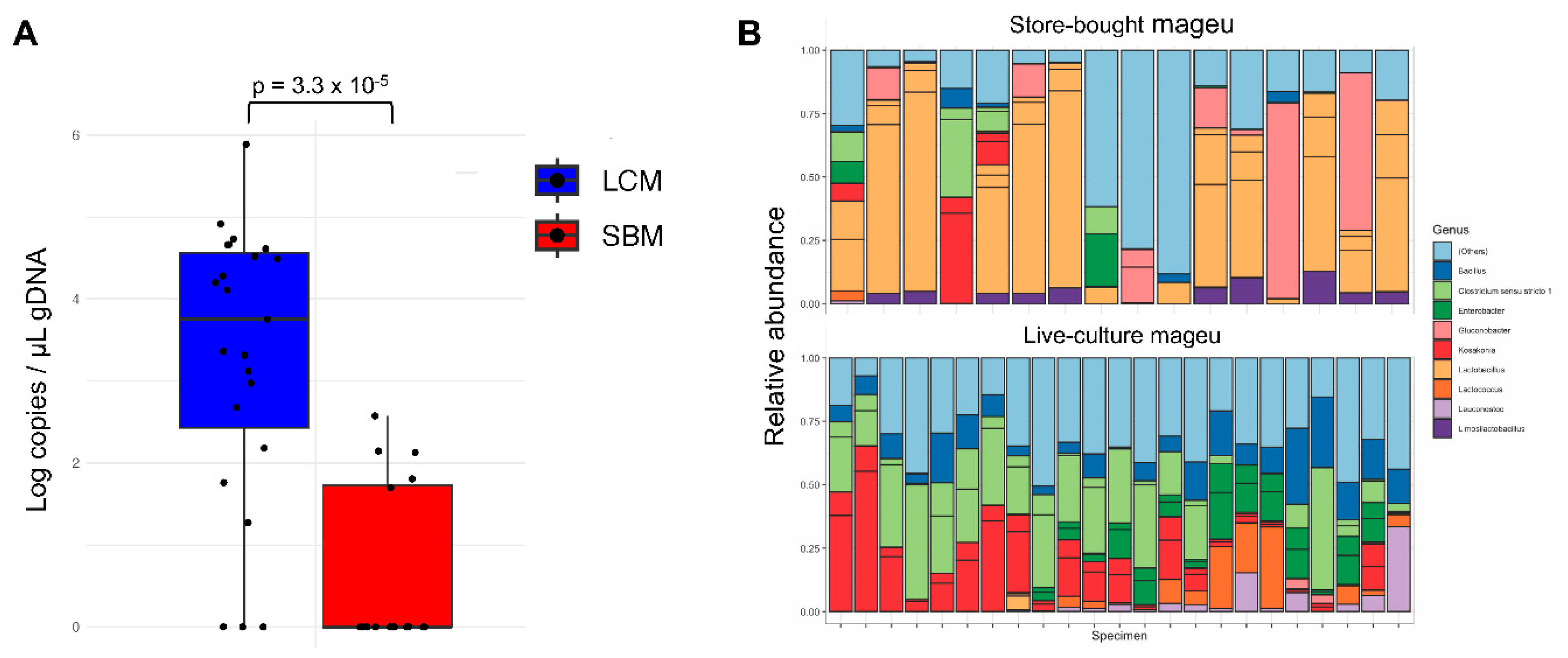

Quantification of total bacterial abundance in mageu samples: Total 16S rRNA gene copies/µL extracted gDNA were measured as previously described [

34]. Standards from 1e8 to 10 copies, a no-template control, and samples were run in duplicate using the SsoAdvanced Universal Probes Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, US) and acquired on a QuantStudio 7 Flex Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, US). Samples were re-run if their Ct standard deviation was high, or the Ct values were outside of the standard curve. Samples with less than 10 total 16S rRNA gene copies/ µL gDNA were deemed to be below the lower limit of detection of the assay.

Measurement of gut and peripheral inflammation and nutritional biomarkers: Concentrations of Interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α were quantified in undiluted maternal plasma collected at weeks 4 and 10, using a Millipore Milliplex Human High Sensitivity T Cell Luminex Panel (Premixed 13-plex; HSTCMAG28SPMX13, Burlington, US), as per manufacturer’s recommendations. Data was acquired using the Bio-PlexTM Suspension Array Reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc®, Hercules, US), and a 5PL regression line was used to determine the cytokine concentrations from the standard curves using the Bio-PlexTM manager software.

At weeks 4 and 10, lipocalin-2 (R&D Biotechne Human Lipocalin-2/NGAL Quantikine, Minneapolis, US) and myeloperoxidase (R&D Biotechne Human Myeloperoxidase Quantikine, Minneapolis, US) concentrations in maternal plasma and faecal calprotectin (R&D Biotechne Human S100A8/S100A9 Heterodimer Quantikine, Minneapolis, US) in maternal faecal extracts were measured by ELISA. Faecal extract was derived from 30 mg of dry maternal stool, as per kit instructions. The protein concentration in each stool sample was measured using a NanoDrop Spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher, Waltham, US) at A280nm and 30 µg of total protein per sample was used. For all ELISA and multiplex assays, intra- and inter-plate controls were included, and coefficients of variations (CVs) ≤ 20% were deemed acceptable. Maternal plasma collected at weeks 4 and 10 was evaluated for soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR, iron sufficiency); retinol binding protein 4 (RBP4, indicator of vitamin A and protein status), thyroglobulin (Tg, iodine status), C-reactive protein (CRP) and Alpha-1-acid glycoprotein (AGP, systemic inflammation) using the Q-Plex Human Micronutrient array (Quansys Biosciences). 25-hydroxy vitamin D [25(OH)VitD3], Vitamin B12, ferritin, and iron levels were measured in maternal serum collected at weeks 4 and 10 by the local National Health Laboratory Service Pathology lab in Cape Town, South Africa.

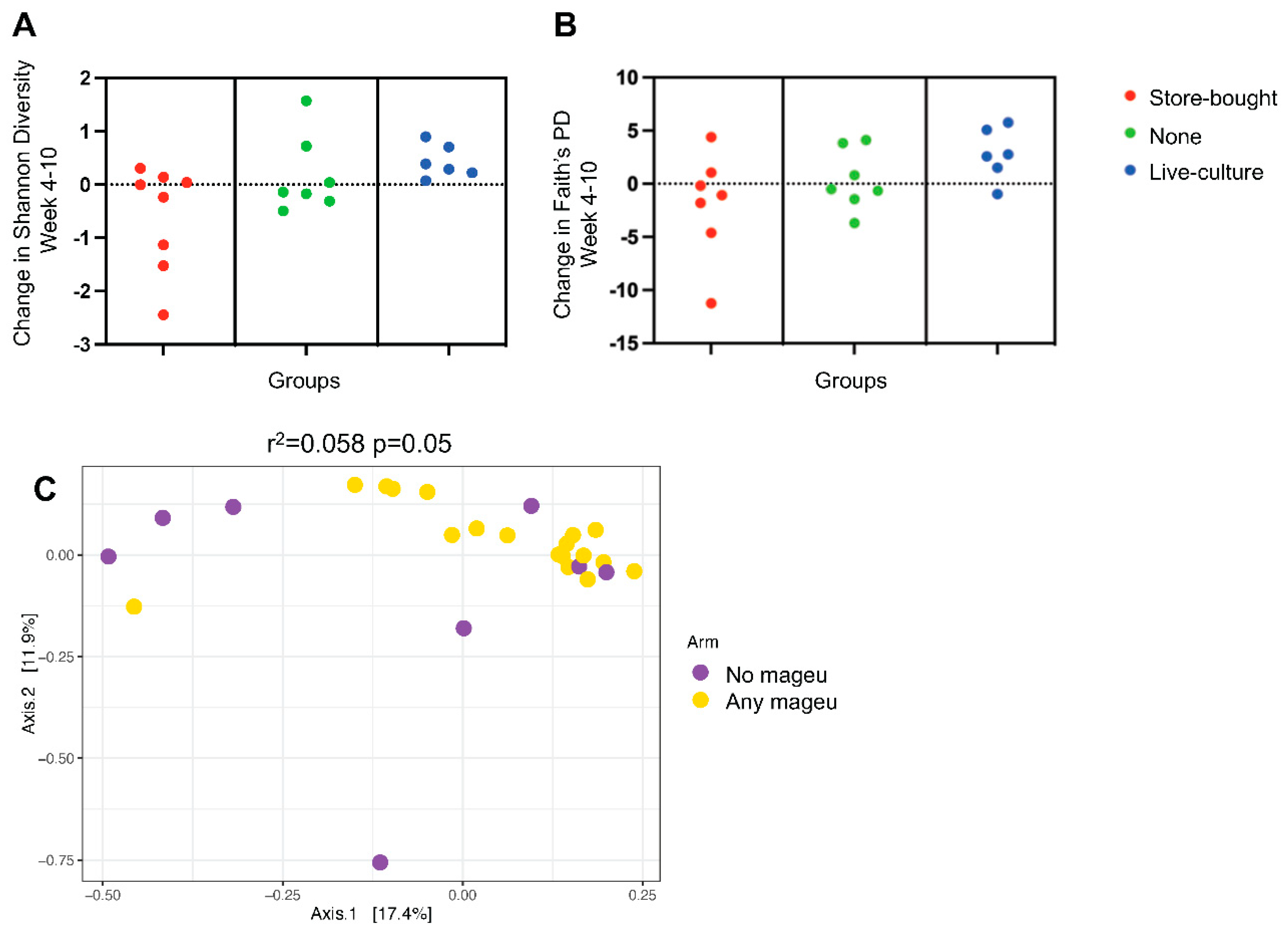

Justification of sample size: The primary outcome was change in maternal stool alpha diversity using Shannon or Faith’s PD index, from the start to end of the intervention (week 4 to week 10). This primary outcome was assessed in the intention to treat (ITT) population (including all women who were randomized). Secondary outcomes included cross-sectional differences in maternal gut microbiota alpha and beta diversity and bacterial taxa at weeks 10 and 15, and changes in systemic inflammatory and nutritional markers from week 4 to week 10. While this was a pilot trial, we estimated that we would have 80% power to detect a 17% difference in stool alpha diversity with a sample size of 15 women per group based on a preliminary analysis of 69 stool samples from non-pregnant, reproductive age women in Cape Town who had a mean gut microbiota Shannon Index of 3.48 (standard deviation, sd, 0.56).

Data analysis: All sequence data processing, classification, and amplicon sequence variant (ASVs) calling was performed using the DADA2 package (version 1.32.0) [

35] within the R framework (version 4.4.0). ASVs were taxonomically classified using an updated version of the Silva training set version 132 [

36], available at

https://github.com/itsmisterbrown/updated_16S_dbs. Run-specific contamination filtering was performed via decontam (version 1.24.0) [

37], and samples with fewer than 1,000 reads filtered, annotated reads were discarded. The phyloseq (version 1.48.0) [

38], picante (version 1.8.2) [

39], ape (version 5.8) [

40], Deseq2 (version 1.44.0) [

41], microbiome (version 1.26.0) [

42], and vegan (version 2.6.6.1) [

43] packages were used for ecological analyses of bacterial communities. Inter-community distance was assessed using Bray-Curtis distance of relative abundance transformed abundance estimates. Alpha-diversity was calculated using Shannon and Faith’s phylogenic diversity. Because microbiome data is compositional, we employed centered log ratio (CLR) transformation [

44] for the differential abundance regression analysis. Taxa were agglomerated to the species level or lowest taxonomic annotation. Statistical tests used include permutational ANOVA (or PERMANOVA) for comparisons among multiple (>2) groups, and Wilcoxon Rank Sum tests for comparisons among two groups. For longitudinal analysis of diversity and CLR transformed relative abundances, we utilized linear mixed models accounting for repeated measures using lmer package in R (version 3.1.3) [

45]. Benjamini Hochberg correction was utilized for multiple comparisons. The Data Integration Analysis for Biomarker discovery using Latent cOmponents (DIABLO) framework, as part of the mixOmics R Bioconductor package (version 6.25.1) [

46], was used for multi-omics analyses integrating the microbial, nutrition and inflammation data. Although this was a pilot trial, p-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using Dunn’s test. [

47]

Discussion

Diet is a major driver of gut microbiome composition and function [

5,

6,

52,

53] and subsequent systemic inflammation, [

8,

9] both of which have been described as underlying causes of many metabolic diseases such as obesity, hypertension, and diabetes [

54,

55]. Maternal nutrition is crucial not only for the mother’s health but also that of their children. Many people in southern Africa face challenges of poverty and inadequate access to a diverse array of foods [

56]. Assessing the impact of a locally acceptable fermented food on maternal gut and immune health provides significant insight into the feasibility of local foods to improve health of a population at risk. Our results utilizing a store-bought pasteurized mageu versus a traditional live-culture preparation of mageu versus no mageu assessed the impact on the postpartum lactating women’s gut microbiota, nutritional status, and inflammation.

Overall, our intervention was found to be feasible. Our inoculum produced product with a wide array of microbes. While batch-to-batch effects were present, the core genera were

Lactobacillus,

Enterococcus, and

Lactococcus, in line with previously descriptions of mageu composition by sequencing [

20,

57]. In contrast, the SBM overall microbial load was low, and had its standard inoculum of

lactobacilli consistently identified by sequencing. This demonstrates that LCM can reliably be produced without contamination with pathogens and contains more complex microbial communities than pasteurized SBM.

Postpartum women enrolled in this study showed good compliance with the intervention. Women in the no mageu group reported increased consumption of starchy foods compared to mageu users, indicating that mageu users were likely substituting normal intake of other starchy foods with mageu. This supports the cultural acceptability of mageu. Furthermore, dietary intake in the three groups was comparable, with the only difference being the significantly higher intake of plant protein among women consuming mageu, regardless of whether this was store-bought or live-culture product, as compared to non-consumers. Importantly, there were no

significant changes in BMI from the beginning to the end of the intervention period, which may be linked to the finding that that total energy intake in all three groups was in line with the EER and did not differ significantly between the groups. This is not surprising as participants received dietary counselling to ensure that energy intake during the study period was aligned with optimal caloric intake. The dietary diversity score for the intervention period was found to be poor and on the lower cut-off of 5 out of 10 for good diversity [

27], but did not differ significantly between groups. The trend towards a poorer dietary diversity may explain the low intake of fiber, calcium, magnesium, vitamin C, vitamin E and folate in all three groups. Inadequate intake of calcium, vitamin C and folate in lower socio-economic communities in the Western Cape is not uncommon [

58].

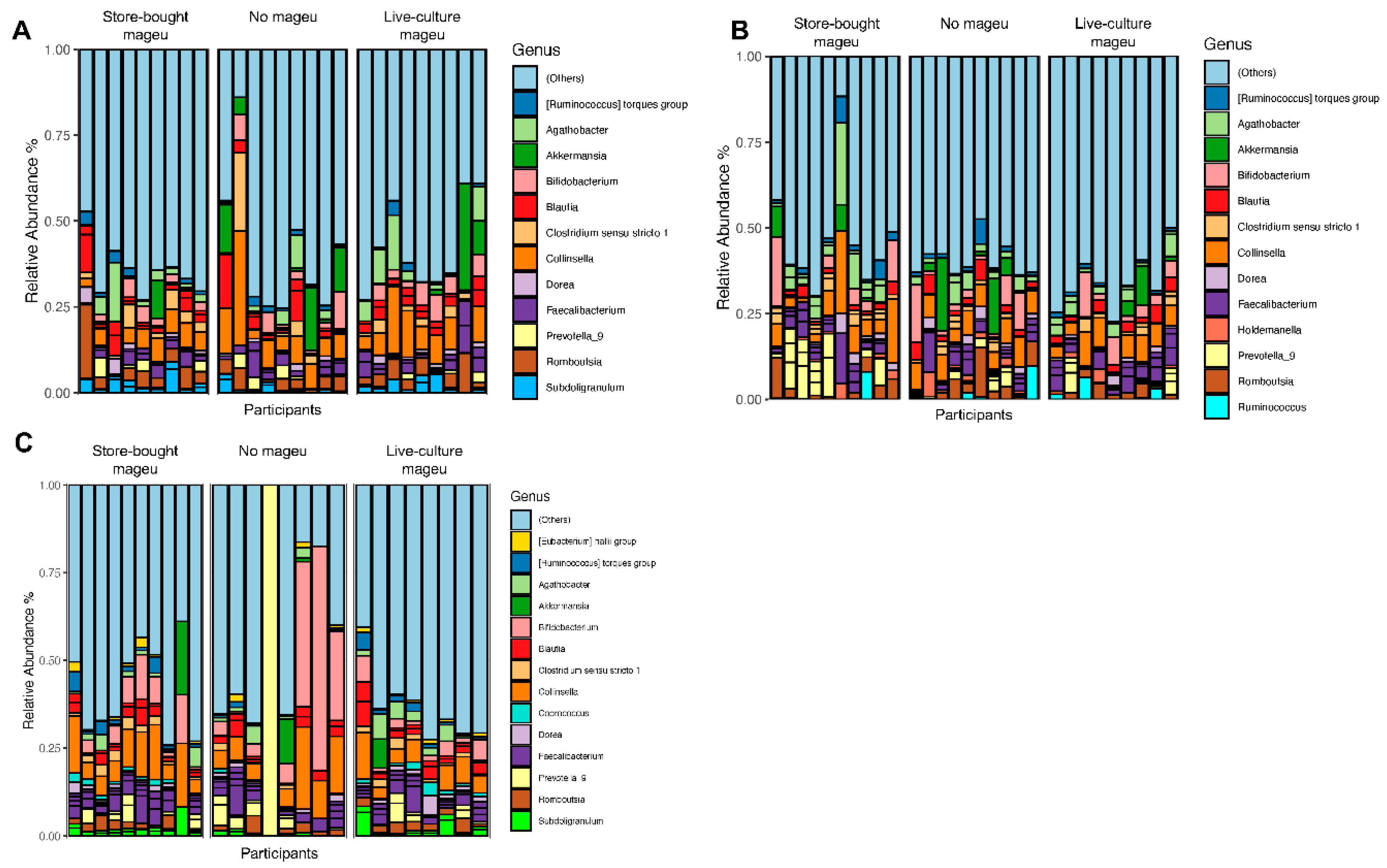

We found that stool microbial diversity was higher and increased during the study in women randomized to LCM, significantly more so than in mothers receiving SBM or no mageu. These results encouragingly suggest that LCM might be an acceptable, cheap, easily implementable, and already available avenue to improve gut health in lactating mothers. Furthermore, the change in Shannon diversity was maintained until week 15 in the LCM group, although this was not true for Faith’s phylogenic diversity. It is thus unclear how long these changes may last or if they require continued mageu consumption to be sustained. Improved gut microbial diversity has been associated with decreased risk of obesity [

59,

60] and insulin resistance [

61], suggesting that mageu may improve metabolic health in women. However, as we recorded no change in BMI over the 6-week intervention period, a larger sample and longer intervention period may be necessary to investigate these potential health benefits.

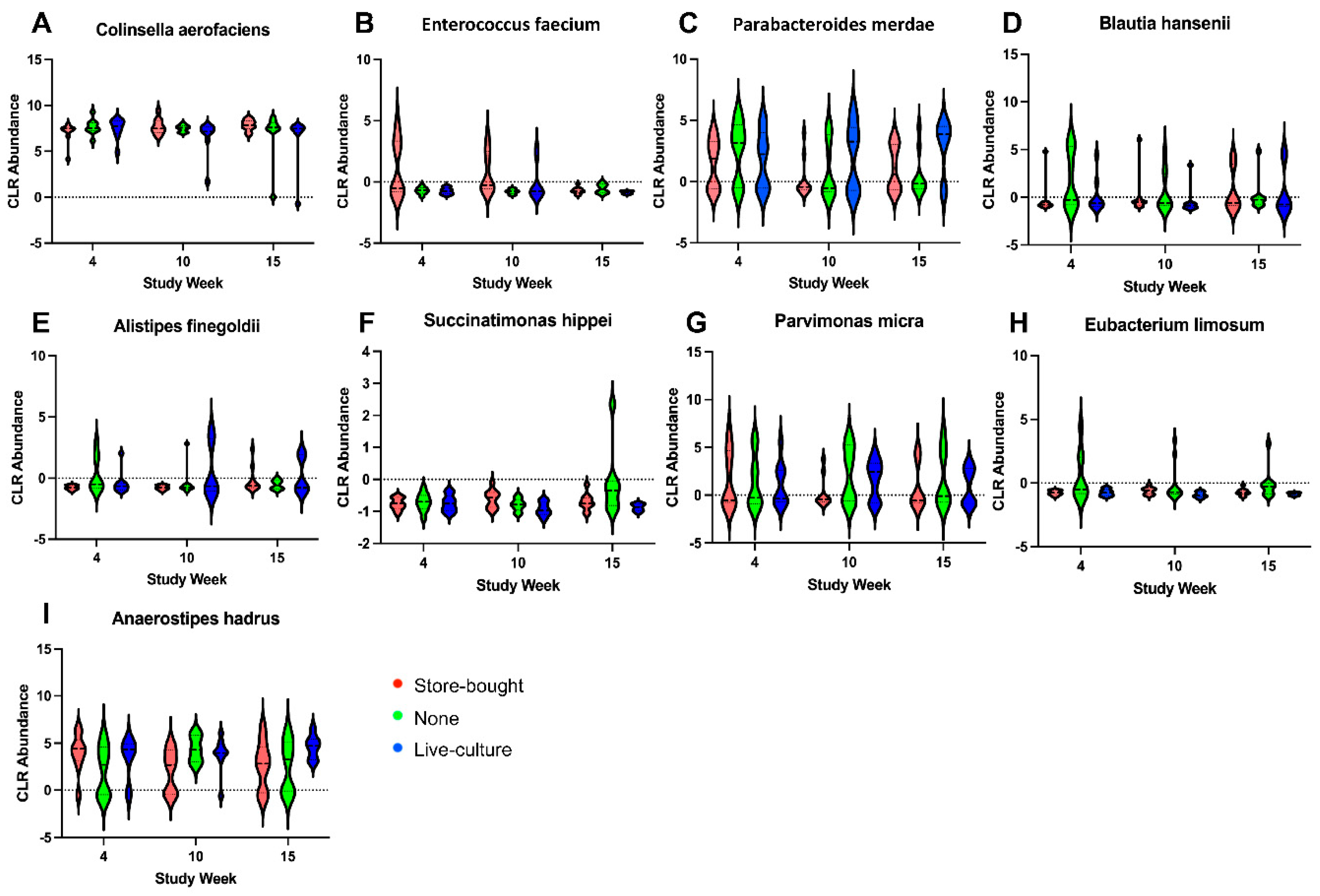

We found changes in faecal bacterial taxa indicative of risk for metabolic diseases that differed between mageu randomization groups and over time. For example, using centered log ratio transformed abundance of taxa,

Blautia hanseii was increased in the SBM group and decreased in the no mageu group.

B. hansenii is negatively associated with visceral fat accumulation [

62] and in animal models was found to mitigate the effects of a high fat diet [

63]. LCM increased

Anaerostipes hadrus relative abundance, a bacterium known to degrade fructooligosaccharides and to increase short-chain fatty acids [

64]. In contrast,

A. hadrus was decreased with time in the SBM group. One study found

A. hadrus, which harbors a composite inositol catabolism-butyrate biosynthesis pathway, to be associated with low host metabolic risk assessed by BMI and abdominal circumference [

65]. The no mageu group had a decrease in

Parabacteroides merdae, which has been associated with branched chain amino acid catabolism and decreased atherosclerosis [

66]. Overall, these findings suggest that LCM may alter the evolving postpartum microbiota favoring taxa associated with metabolic health.

The change in gut microbial diversity was not accompanied by a general decrease in inflammation, neither for intestinal nor for systemic markers measured. This is inconsistent with a previous meta-analysis of RCTs that found fermented foods to lead to a reduction of TNF-α levels [

16]. However, the same authors found that intake of fermented foods did not improve circulating CRP and IL-6 [

16], which is in line with our findings. The relatively short duration of the intervention and small sample size might have not been sufficient to see modulation of the immune system through changes in the stool microbiota. Further, in this group of women without comorbidities, who were recently pregnant (a state of relatively low inflammation), it may be more difficult to see changes in inflammation. We however found that ferritin was significantly lower in the LCM group than the no mageu group at week 10. Ferritin is an acute-phase reactant that coordinates cellular defense against oxidative stress and inflammation along with transferrin and its receptor [

51]. Ferritin levels are also markers of iron sufficiency [

51] . As we did not see differences between groups in transferrin receptor and iron levels, low ferritin indeed might have been a marker of low inflammation, with its decrease coinciding with an increase in stool diversity. As differences in stool microbial diversity and ferritin levels were only observed in the LCM group, this could point towards the superiority of live-culture over pasteurized mageu in its ability to improve gut and immune health of lactating women.

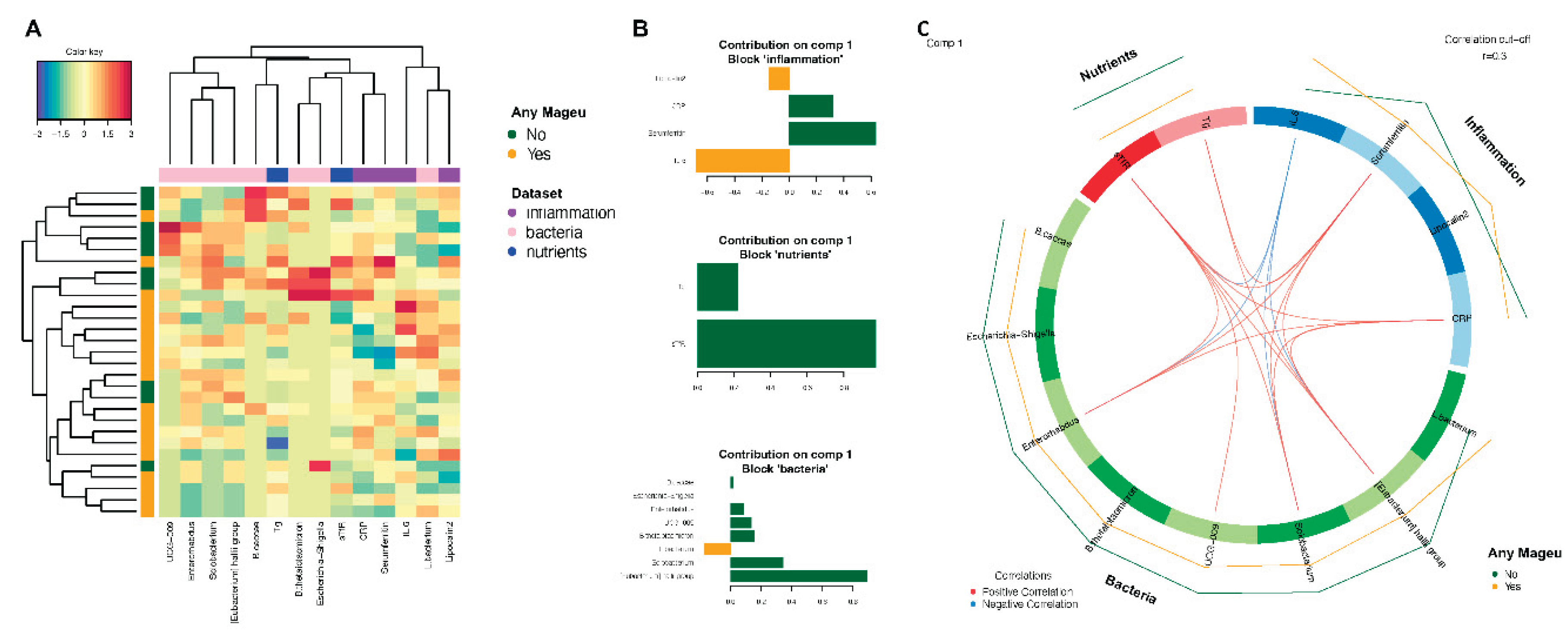

Integration of nutritional, bacterial, and inflammatory datasets revealed that the most variance between mageu and no mageu use was driven by ferritin, sTfR, and

E. halli, all higher with no mageu use, and IL-6, which was lower among no mageu users. IL-6 plays an important role in the activation of host defense after infection and injury. However, excessive or sustained production of IL-6 is involved in various diseases [

67]. A recent systematic review found no effects of fermented food consumption on IL-6 [

16], and larger cohorts are necessary to further elucidate the relationship between IL-6 and mageu consumption. As mentioned above, ferritin can act as a marker of both acute inflammation and iron sufficiency. When tissue iron availability is low, membrane receptors are upregulated to take more iron into the cells, resulting in increased serum sTfR levels [

68], making high sTfR a marker of iron deficiency. Mageu may therefore dampen acute phase inflammation (i.e. lower CRP and ferritin) and stabilize iron stores (i.e. lower sTfR).

E. hallii is considered a key species within the intestinal trophic chain with the potential to impact metabolic balance as well as the gut microbiota/host homeostasis by the formation of short-chain fatty acids [

69]. Butyrate and other short-chain fatty acids, through different mechanisms, inhibit intestinal inflammation, maintain the intestinal barrier, and modulate gut motility [

70].

This study was designed to explore the effects of a locally acceptable fermented food on both the gut microbiota and inflammation in postpartum women – a population group whose nutritional status is central to the development of their children given they are exclusively breastfeeding. Although this study provided critical preliminary and encouraging insights into the effect of mageu consumption on gut microbiota composition and immune status, we acknowledge several limitations. This study included a small sample size of mostly overweight women, which limits power and our ability to generalize results. The intervention phase was limited to 6 weeks, and a longer intervention period might have resulted in more profound changes in gut microbiota and inflammation. Participants in this urban area were generally healthy albeit overweight, with risk of low intake of some micronutrients, and future studies could explore the effect of mageu on gut and immune health among people diagnosed with inflammatory conditions. Strengths included the study of lactating women, a group that is usually excluded from research. Furthermore, the study included a no mageu control arm and comparisons between LCM and SBM, increasing the practicality of the findings. Lastly, the study design also included a washout phase, allowing us to generate a similar ‘baseline’ diet profile among all participants.

In conclusion, we showed that LCM might have beneficial effects on gut and immune health of women. Given the local context and relevance of these findings for maternal and infant nutrition, this should be explored in a larger cohort. Assessment of maternal breastmilk and infant gut microbiota, immune status, and overall health would provide significant insight into the usability of a plant-based, local fermented food to improve maternal and infant health outcomes.