Submitted:

12 May 2025

Posted:

14 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

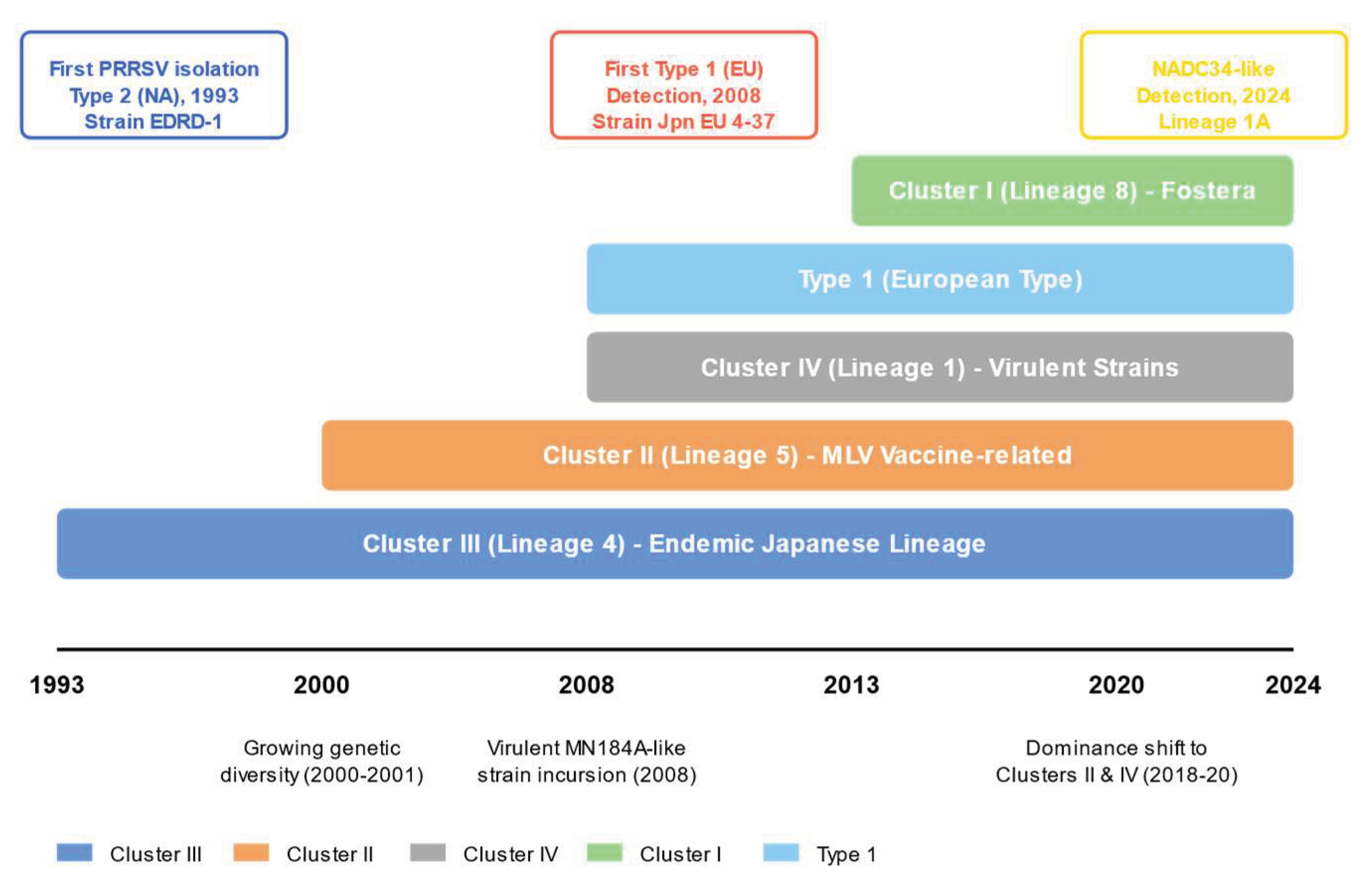

2. Discovery of PRRSV and Characteristics of Early Genotypes in Japan (1993–2007)

3. Incursion of European Type and Expansion of Genetic Diversity (2008–2013)

4. Impact on Production Performance and Economic Losses (2010 Survey and National Estimates)

5. Shift in Cluster Composition and Association with Vaccines (2018–2020)

6. Incursion of Foreign Strains and New Risks (2024: Emergence of NADC34-like strain)

7. Challenges in Vaccines and Preventive Measures

8. Future Actions and Prospects

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Snijder, E.J.; Kikkert, M.; Fang, Y. Arterivirus molecular biology and pathogenesis. J. Gen. Virol. 2013, 94, 2141–2163. [CrossRef]

- Rossow, K.D. Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome. Vet. Pathol. 1998, 35, 1–20.

- World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH). Infection with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. In Terrestrial Animal Health Code. Available online: https://www.google.com/search?q=https://www.woah.org/en/what-we-do/standards/codes-and-manuals/terrestrial-code-online-access/%3Fid%3D169%26L%3D1%26htmfile%3Dchapitre_prrs.htm (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Holtkamp, D.J.; Kliebenstein, J.B.; Neumann, E.J.; Zimmerman, J.J.; Rotto, H.F.; Yoder, T.K.; Wang, C.; Yeske, P.E.; Mowrer, C.L.; Haley, C.A. Assessment of the economic impact of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus on United States pork producers. J. Swine Health Prod. 2013, 21, 72–84. [CrossRef]

- Yamane, I.; Kure, K.; Ishikawa, H.; Takagi, M.; Miyazaki, A.; Suzuki, T.; et al. Evaluation of the economical losses due to the outbreaks of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome. (A questionnaire-based epidemiological survey and estimation of the total economical losses in Japan). Proc. Jpn. Pig Vet. Soc.2009, 55, 33–37. (In Japanese).

- Yamane, I.; Kure, K.; Ishikawa, H.; Takagi, M.; Yoshii, M.; Okinaga, T.; et al. Evaluation of the economical losses due to the outbreaks of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome. (Results from 6 targeted farms being investigated). Proc. Jpn. Pig Vet. Soc. 2009, 54, 8–13. (In Japanese).

- Hanada, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Nakane, T.; Hirose, O.; Gojobori, T. The origin and evolution of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome viruses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2005, 22, 1024–1031. [CrossRef]

- Kimman, T.G.; Cornelissen, L.A.; Moormann, R.J.; Rebel, J.M.; Stockhofe-Zurwieden, N. Challenges for porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) vaccinology. Vaccine 2009, 27, 3704–3718. [CrossRef]

- Charerntantanakul, W. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus vaccines: Immunogenicity, efficacy and safety aspects. World J. Virol. 2012, 1, 23–30. [CrossRef]

- Peng, N.; Zhou, P.; Pei, Y.; Lin, C.; Li, H.; Feng, Z.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Z.; Ma, J.; Huang, L. Genetic background influences pig responses to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1289570.

- Mateu, E.; Diaz, I. The challenge of PRRS immunology. Vet. J. 2008, 177, 345–351. [CrossRef]

- Opriessnig, T.; Giménez-Lirola, L.G.; Halbur, P.G. PRRSV: Interaction with other respiratory pathogens. Pig333, 29 July 2013. Available online: https://www.pig333.com/articles/prrsv-interaction-with-other-respiratory-pathogens_7443/ (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Fiers, J.; Cay, A.B.; Maes, D.; Tignon, M. A Comprehensive Review on Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus with Emphasis on Immunity. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12, 935. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Cao, D.; Zhang, T.; Tang, Y.-D.; Liu, W.-M.; Cao, Y.-C.; Wei, J.-C.; Zhang, L.-C.; Zhang, G.-H. PRRSV evades innate immune cGAS-STING antiviral function via its Nsp5 to deter STING translocation and activation. bioRxiv 2025, 2025.02.24.639812 (Preprint).

- Ito, H.; Ouchi, S.; Kato, K.; Komoda, M.; Higuchi, A.; Yamada, T.; et al. The first outbreak of predicted PRRS in Japan. (1) The case in Gunma Prefecture. Proc. Jpn. Pig Vet. Soc. 1995, 26, 6–9. (In Japanese).

- Murakami, Y.; Kato, A.; Tsuda, T.; Morozumi, T.; Miura, Y.; Sugimura, T. Isolation and Serological Characterization of Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome (PRRS) Viruses from Pigs with Reproductive and Respiratory Disorders in Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 1994, 56, 891–894. [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, M.; Yamada, S.; Murakami, Y.; Tsuda, T.; Morozumi, T.; Kokuho, T.; et al. Isolation of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus from Heko-Heko disease of pigs. J. Vet. Med. Sci.1994, 56, 389–391. [CrossRef]

- Yoshii, M.; Kaku, Y.; Murakami, Y.; Shimizu, M.; Kato, K.; Ikeda, H. Genetic variation and geographic distribution of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in Japan. Arch. Virol. 2005, 150, 2313–2324. [CrossRef]

- Iseki, H.; Takagi, M.; Miyazaki, A.; Katsuda, K.; Mikami, O.; Tsunemitsu, H. Genetic analysis of ORF5 in porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in Japan. Microbiol. Immunol. 2011, 55, 211–216. [CrossRef]

- Iseki, H.; Takagi, M.; Kawashima, K.; Shibahara, T.; Kuroda, Y.; Tsunemitsu, H. Type 1 porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus emerged in Japan. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Pig Veterinary Society Congress, Jeju, Korea, 10–13 June 2012; p. 978.

- Iseki, H.; Morozumi, T.; Takagi, M.; Kawashima, K.; Shibahara, T.; Uenishi, H.; et al. Genomic sequence and virulence evaluation of MN184A-like porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in Japan. Microbiol. Immunol. 2016, 60, 824–834. [CrossRef]

- Kyutoku, F.; Yokoyama, T.; Sugiura, K. Genetic Diversity and Epidemic Types of Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome (PRRS) Virus in Japan from 2018 to 2020. Epidemiologia (Basel) 2022, 3, 285–296. [CrossRef]

- Trevisan, G.; Magstadt, D.; Woods, A.; Sparks, J.; Zeller, M.; Li, G.; Krueger, K.M.; Saxena, A.; Zhang, J.; Gauger, P.C.; Linhares, D.C.L. A recombinant porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus type 2 field strain derived from two PRRSV-2-modified live virus vaccines. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1149293. [CrossRef]

- Ruedas-Torres, I.; Rodríguez-Gómez, I.M.; Sánchez-Carvajal, J.M.; Larenas-Muñoz, F.; Gómez-Laguna, J.; Pallarés, F.J.; Carrasco, L.; Oleksiewicz, M.B.; Risalde, M.Á.; Botti, S.; Fraile, L.; Barasona, J.A.; Mínguez, O.; Sánchez-Vizcaíno, J.M.; Mateu, E.; Martín-Acebes, M.A. The jigsaw of PRRSV virulence. Vet. Microbiol. 2021, 260, 109168.

- Yoshii, M.; Okinaga, T.; Miyazaki, A.; Kato, K.; Ikeda, H.; Tsunemitsu, H. Genetic polymorphism of the nsp2 gene in North American type-Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Arch. Virol. 2008, 153, 1173–1178. [CrossRef]

- Iseki, H.; Kawashima, K.; Takagi, M.; Shibahara, T.; Mase, M. Studies on heterologous protection between Japanese type 1 and type 2 porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus isolates. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2020, 82, 935–942. [CrossRef]

- Iseki, H.; Takagi, M.; Kawashima, K.; Shibahara, T.; Kuroda, Y.; Tsunemitsu, H.; et al. Pathogenicity of emerging Japanese type 1 porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in experimentally infected pigs. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2015, 77, 1507–1510. [CrossRef]

- Ishizeki, S.; Ishikawa, H.; Adachi, Y.; Yamazaki, H.; Yamane, I. Study on association of productivity and farm level status of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome in pig farms in Japan. Nihon Chikusan Gakkaiho 2014, 85, 171–177. (In Japanese). [CrossRef]

- Yamane, I. Evaluation of the economical losses due to the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome. Proc. Jpn. Pig Vet. Soc. 2013, 61, 1–4. (In Japanese).

- Yim-im, W.; Anderson, T.K.; Paploski, I.A.D.; VanderWaal, K.; Gauger, P.; Krueger, K.; Shi, M.; Main, R.; Zhang, J.Q.; Chao, D.Y. Refining PRRSV-2 genetic classification based on global ORF5 sequences and investigation of their geographic distributions and temporal changes. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e02916-23.

- Yonezawa, Y.; Taira, O.; Omori, T.; Tsutsumi, N.; Sugiura, K. First detection of NADC34-like porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus strains in Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2025, 87, 110–114. [CrossRef]

- VanderWaal, K.; Pamornchainavakul, N.; Kikuti, M.; Zhang, J.; Zeller, M.; Trevisan, G.; Rossow, S.; Schwartz, M.; Linhares, D.C.L.; Holtkamp, D.J.; Herrera da Silva, J.P.; Corzo, C.A.; Baker, J.P.; Anderson, T.K.; Makau, D.N.; Paploski, I.A.D. PRRSV-2 variant classification: a dynamic nomenclature for enhanced monitoring and surveillance. mSphere 2024, 9, e00709-24. [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Huang, C.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhou, L.; Wu, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; He, Q.; Chen, H.; Qian, P. Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus Prevalence and Pathogenicity of One NADC34-like Virus Isolate Circulating in China. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 796.

- Wesley, R.D.; Mengeling, W.L.; Lager, K.M.; Clouser, D.F.; Landgraf, J.G.; Frey, M.L. Differentiation of a Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus Vaccine Strain from North American Field Strains by Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism Analysis of ORF 5. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 1998, 10, 140–144. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhu, L.; Li, Y.; Yan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Ji, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, E.-M.; Chen, H.-B. Protective evaluation of the commercialized porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus vaccines in piglets challenged by NADC34-like strain. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1422335.

- Luo, Y.; Xu, J.; Xia, W.; Hou, G.; Wang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Cui, L.; Wang, X.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, G.; Li, J.; Liu, Y. Efficacy of a reduced-dosage PRRS MLV vaccine against a NADC34-like strain of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1493384.

- Iseki, H.; Kawashima, K.; Shibahara, T.; Mase, M. Immunity against a Japanese local strain of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus decreases viremia and symptoms of a highly pathogenic strain. BMC Vet. Res. 2021, 17, 156. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Miller, L.C.; Sang, Y. Current Status of Vaccines for Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome: Interferon Response, Immunological Overview, and Future Prospects. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12, 606. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y., Gao, Y., Su, T., Zhang, L., Zhou, H., Zhang, J., Sun, H., Bai, J., & Jiang, P. Nanoparticle Vaccine Triggers Interferon-Gamma Production and Confers Protective Immunity against Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus. ACS Nano. 2025, 9 (1), 852-870. [CrossRef]

- Kawabata, T. Control measures against porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome in a high-density swine production area. Proc. Jpn. Pig Vet. Soc. 2014, 63, 22–26. (In Japanese).

- Dee, S.; Brands, L.; Edler, R.; Schelkopf, A.; Nerem, J.; Spronk, G.; Kikuti, M.; Corzo, C.A. Further Evidence That Science-Based Biosecurity Provides Sustainable Prevention of Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus Infection and Improved Productivity in Swine Breeding Herds. Animals (Basel) 2024, 14, 2530. [CrossRef]

- Niederwerder, M.C.; Ressenig, K.R.; Gebhardt, J.T.; Bryer, C.L.; Pouggouras, K.C.; Woodworth, J.C.; DeRouchey, J.M.; Dritz, S.S.; Goodband, R.D. An assessment of enhanced biosecurity interventions and their impact on porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus outbreaks within a managed group of farrow-to-wean farms, 2020–2021. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2023, 261 (S1), S57–S66.

- Fukunaga, W.; Hayakawa-Sugaya, Y.; Koike, F.; Diep, N.V.; Kojima, I.; Yoshida, Y.; et al. Newly-designed primer pairs for the detection of type 2 porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus genes. J. Virol. Methods 2021, 291, 114071. [CrossRef]

- Mizukami, Y. Construction of regional network for the PRRS free project. Proc. Jpn. Pig Vet. Soc. 2013, 61, 11–13. (In Japanese).

- Dee, S. How to control and eliminate PRRS from swine herds on farm and regional level. CAB Rev. 2012, 7, 1–9.

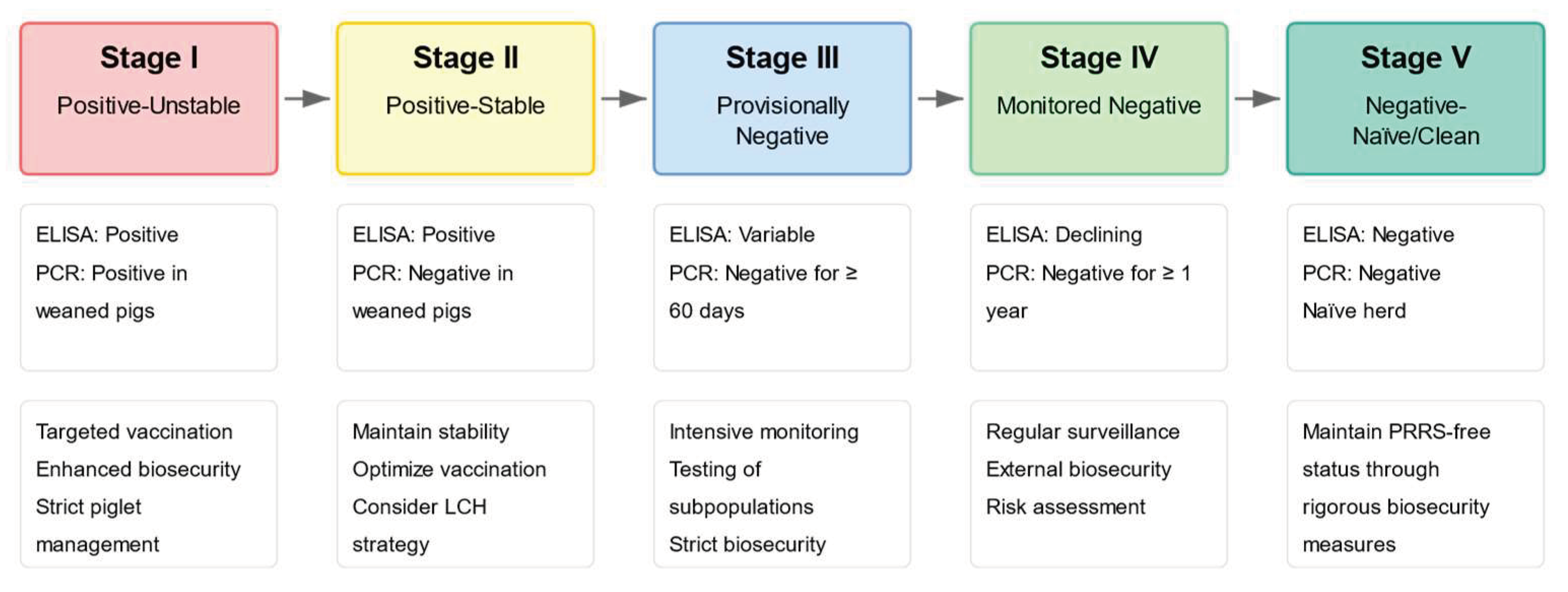

- Farm Stage Definitions for Promoting Eradication of Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome (PRRS). Available online: https://site-pjet.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/document2.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2025). (In Japanese).

- Magalhães, E.S.; Zimmerman, J.J.; Holtkamp, D.J.; Classen, D.M.; Groth, D.D.; Glowzenski, L.; Philips, R.; Silva, G.S.; Linhares, D.C.L. Next Generation of Voluntary PRRS Virus Regional Control Programs. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 769312. [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.P.; Rovira, A.; VanderWaal, K. Repeat offenders: PRRSV-2 clinical re-breaks from a whole genome perspective. Vet. Microbiol. 2025, 302, 110411. [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A.M.; Linhares, D.C.L.; Trevisan, G.; Crim, B.; Burrough, E.; Gauger, P.; Madson, D.; Thomas, J.; Zeller, M.; Zhang, J.; Main, R.; Rovira, A.; Thurn, M.; Lages, P.; Corzo, C.A.; Sturos, M.; VanderWaal, K.; Naikare, H.; Matias-Ferreyra, F.; McGaughey, R.; Retallick, J.; McReynolds, S.; Arruda, L.C.S.P.; Schwartz, M.; Yeske, P.; Murray, D.; Mason, B.; Schneider, P.; Copeland, S.; Dufresne, L.; Boykin, D.; Fruge, C.; Hollis, W.; Robbins, R.; Petznick, T.; Kuecker, K.; Glowzenski, L.; Niederwerder, M.; Huang, X. Harnessing sequencing data for porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV): tracking genetic evolution dynamics and emerging sequences in US swine industry. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, Mar 6:12:1571020. [CrossRef]

- Zuckermann, F.A.; Garcia, E.A.; Luque, I.D.; Christopher-Hennings, J.; Doster, A.R.; Murtaugh, M.P.; Nelson, E.A.; Schwartz, K.-J.; Torrison, J.L.; Wasilk, A.M. Assessment of the efficacy of commercial porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) vaccines based on evaluation of virologic protection following challenge with a virulent strain of type 2 PRRSV. Vaccine 2007, 25, 5098–5108.

| Vaccine Name | Type | Lineage | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ingelvac® PRRS MLV | MLV (Type 2) | Lineage 5 | Boehringer Ingelheim |

| Fostera® PRRS | MLV (Type 2) | Lineage 8 | Zoetis |

| Nisseiken PRRS Vaccine ME | KV (Type 2) | Lineage 4 | Nisseiken Co., Ltd. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).