Submitted:

12 May 2025

Posted:

14 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

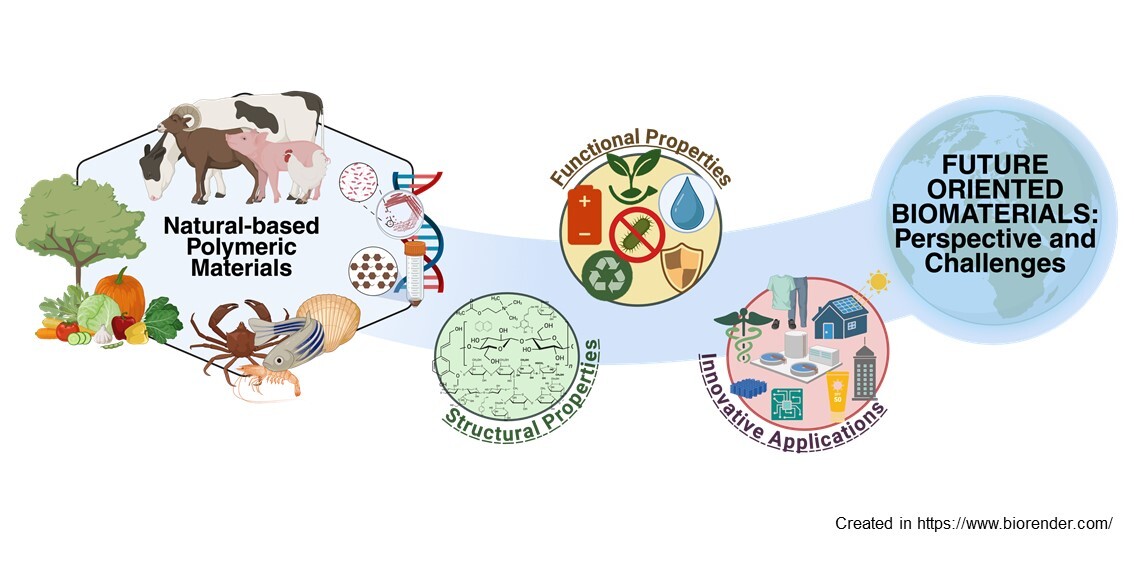

1. Introduction

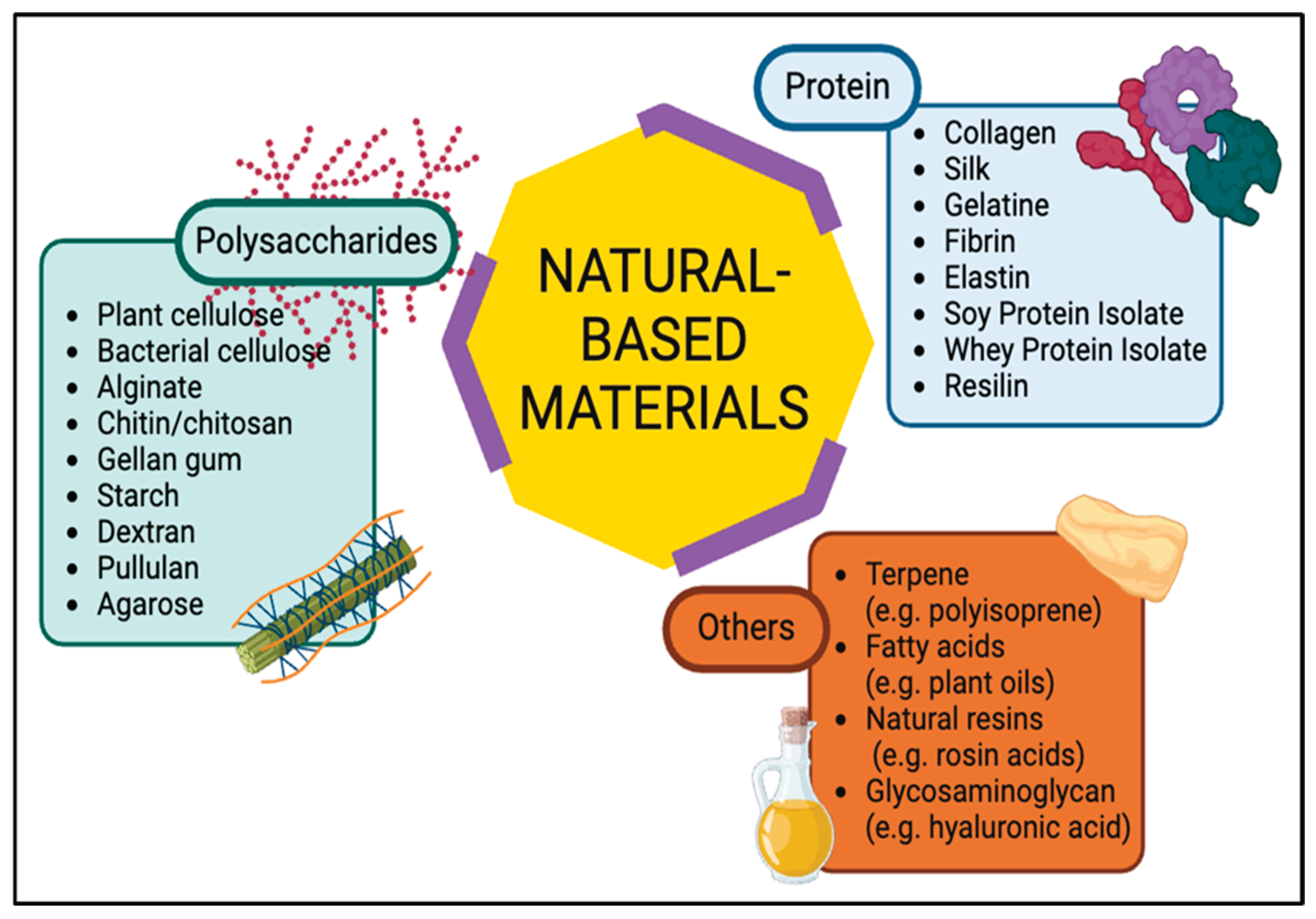

2. Characteristics of Biomaterials

2.1. Polysaccharide-Based Materials

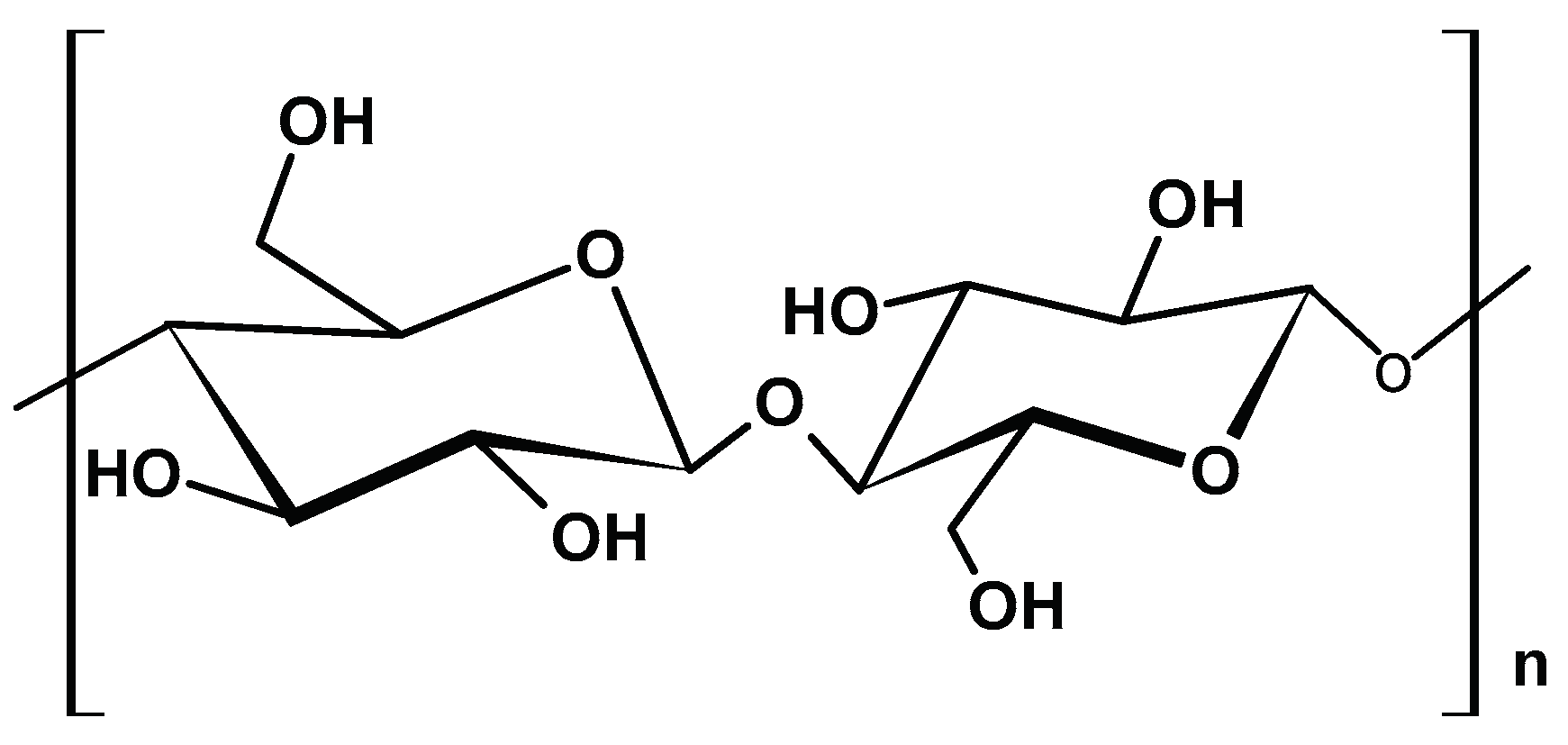

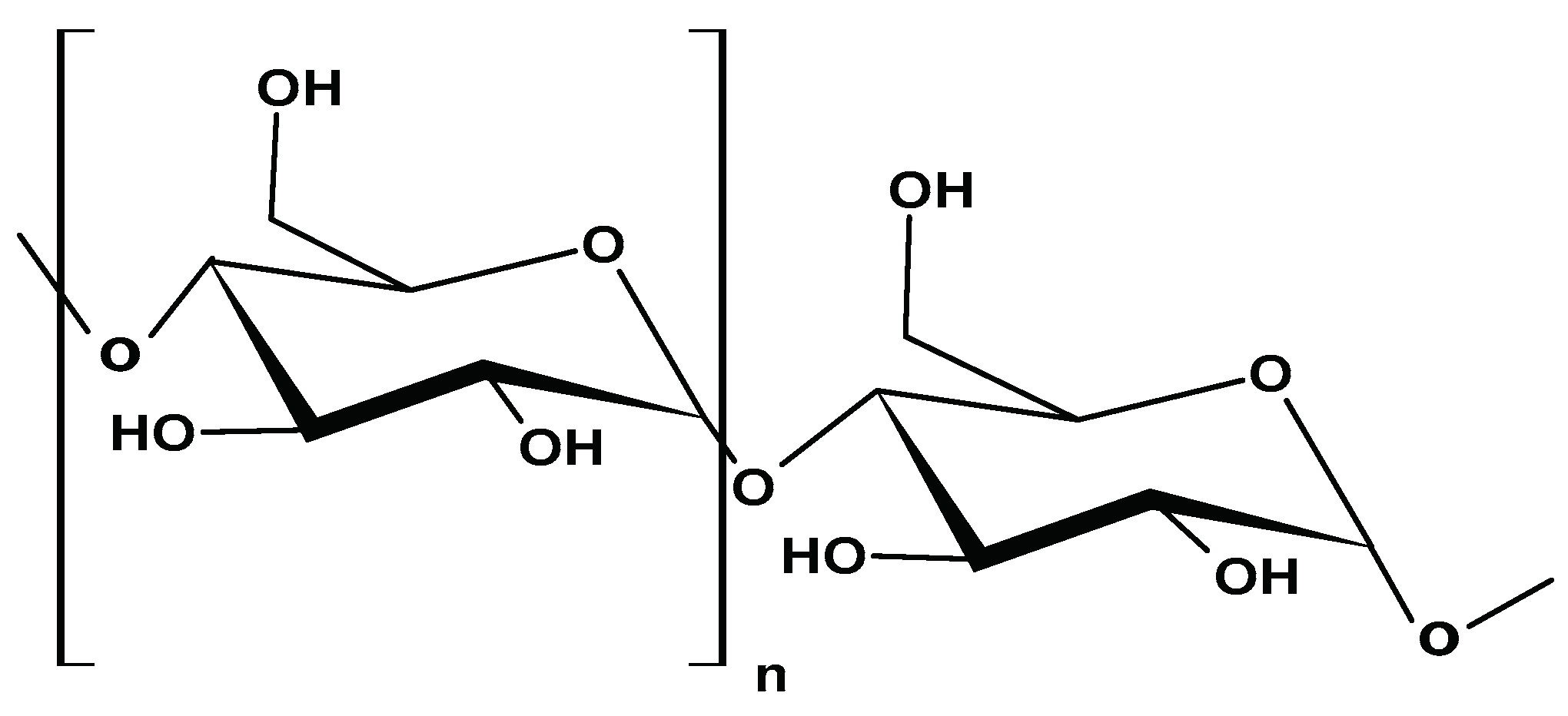

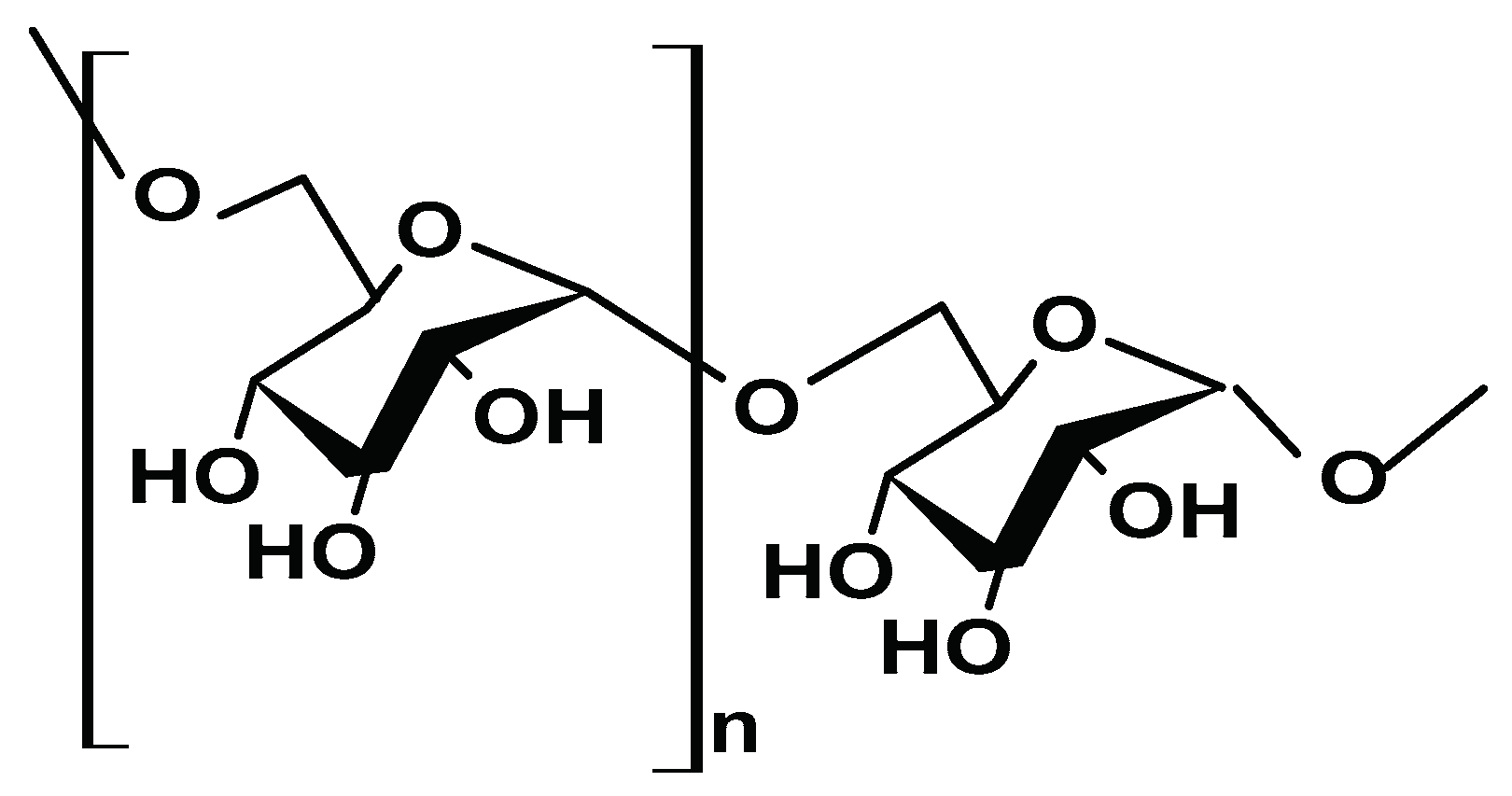

2.1.1. Cellulose

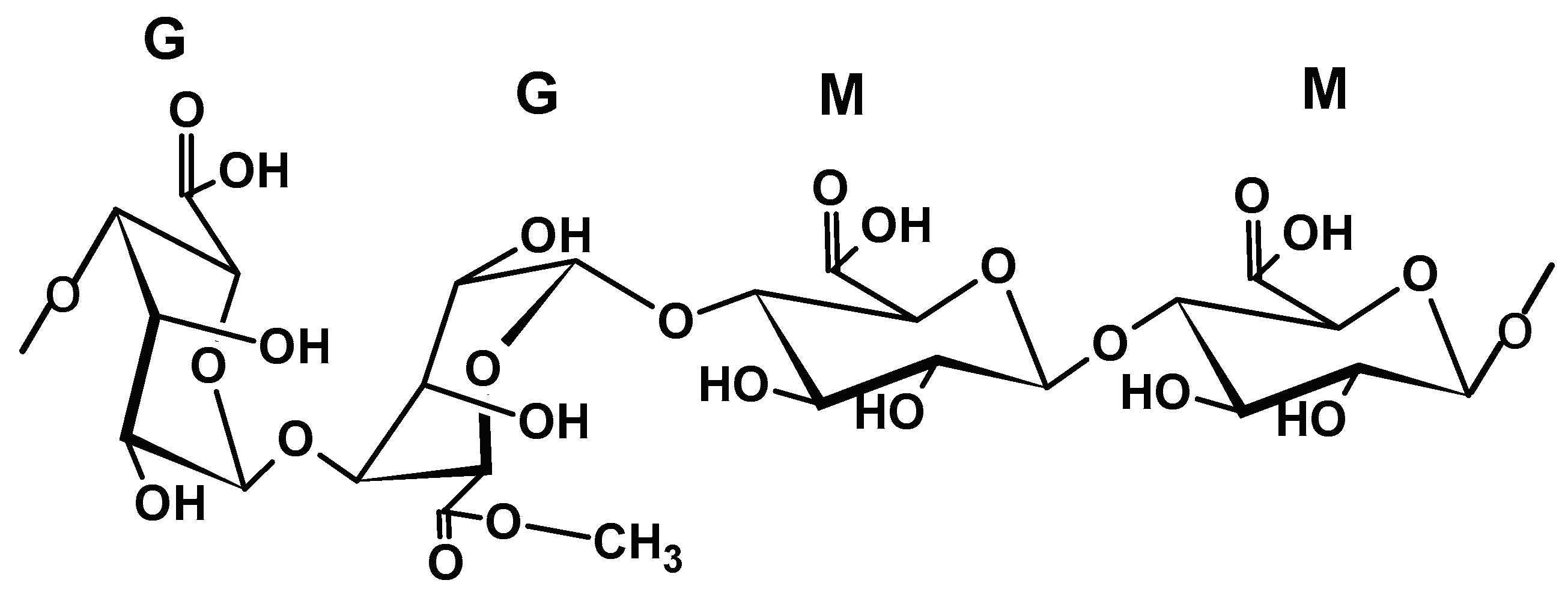

2.1.2. Alginate

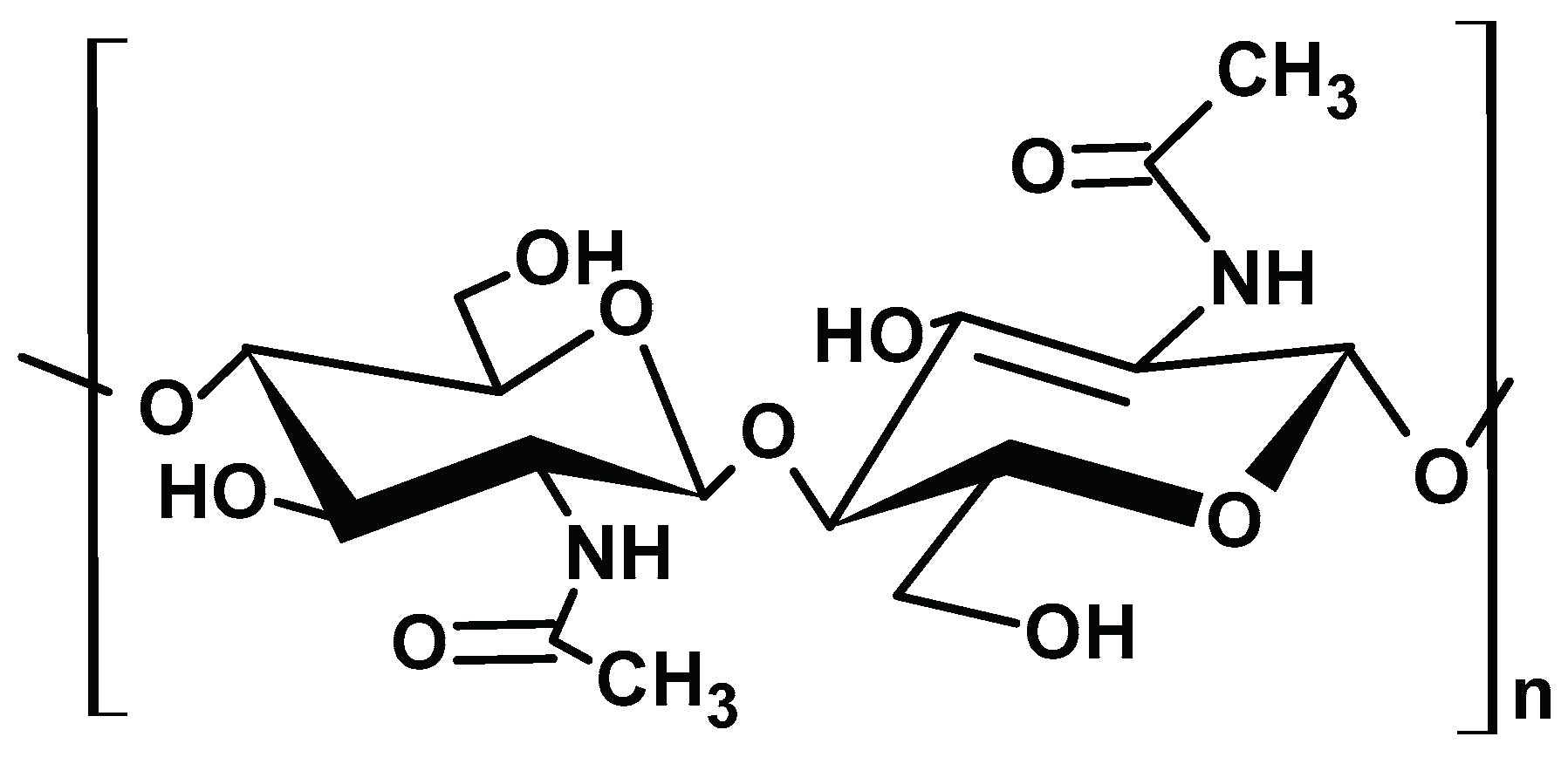

2.1.3. Chitin

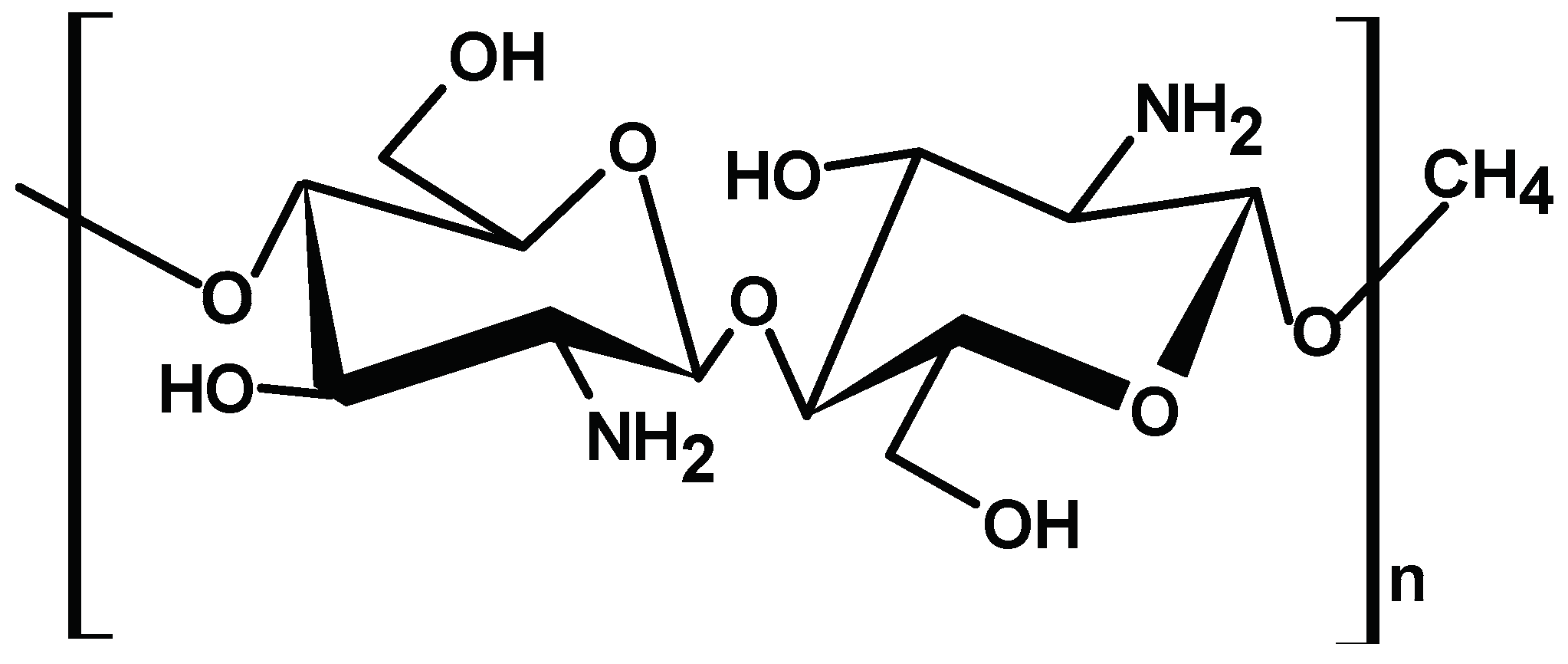

2.1.4. Chitosan

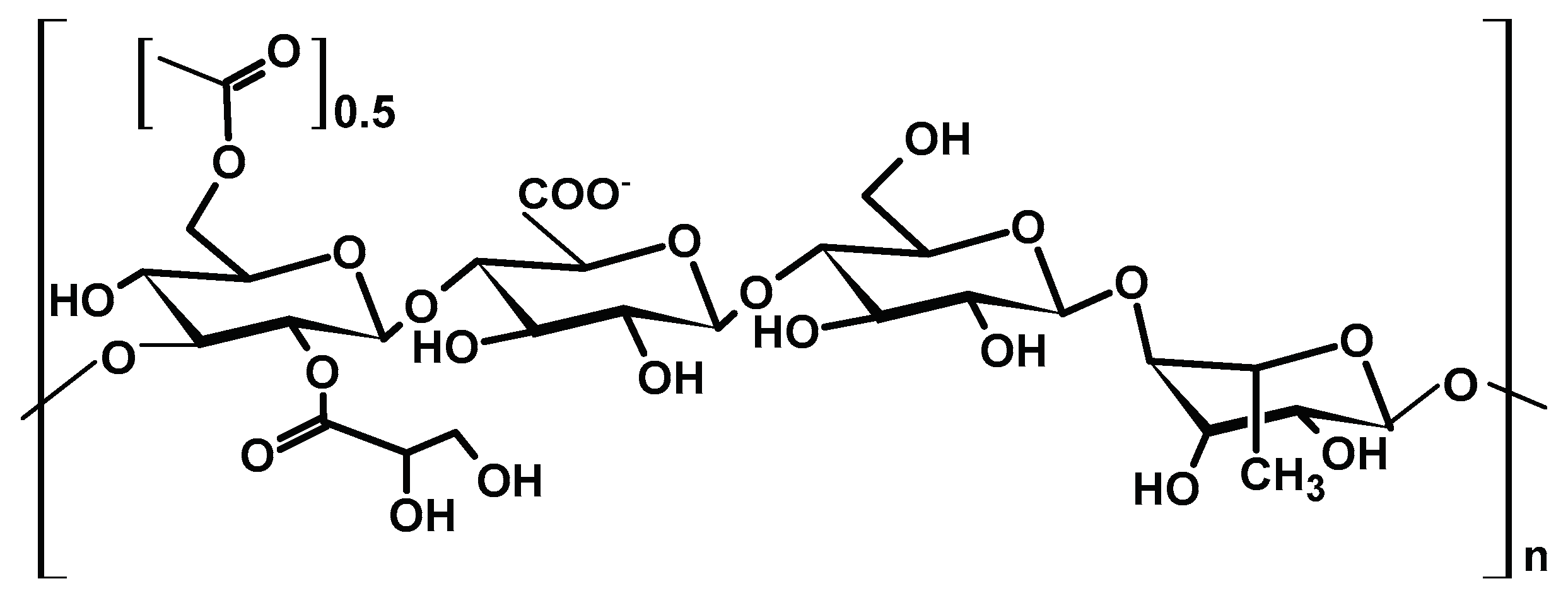

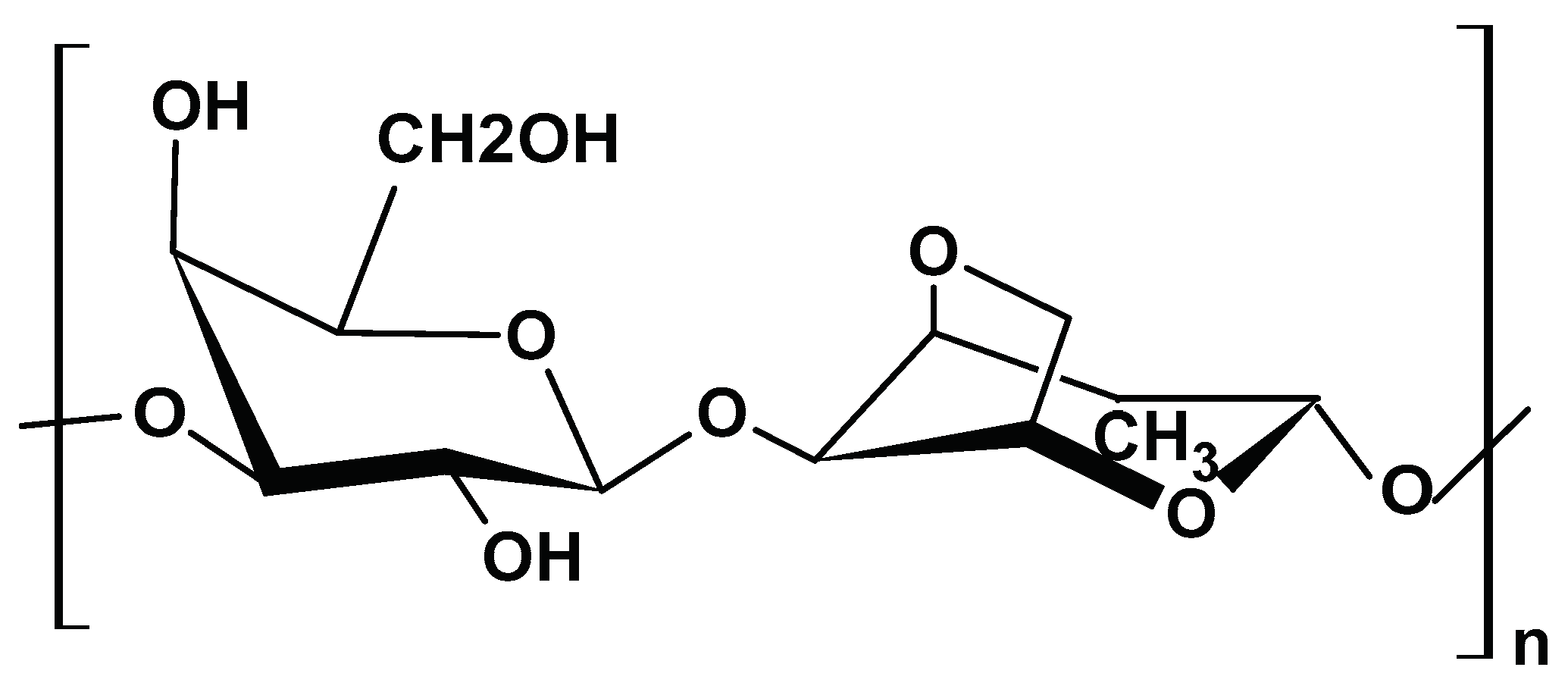

2.1.5. Gellan Gum

2.1.6. Starch

2.1.7. Dextran

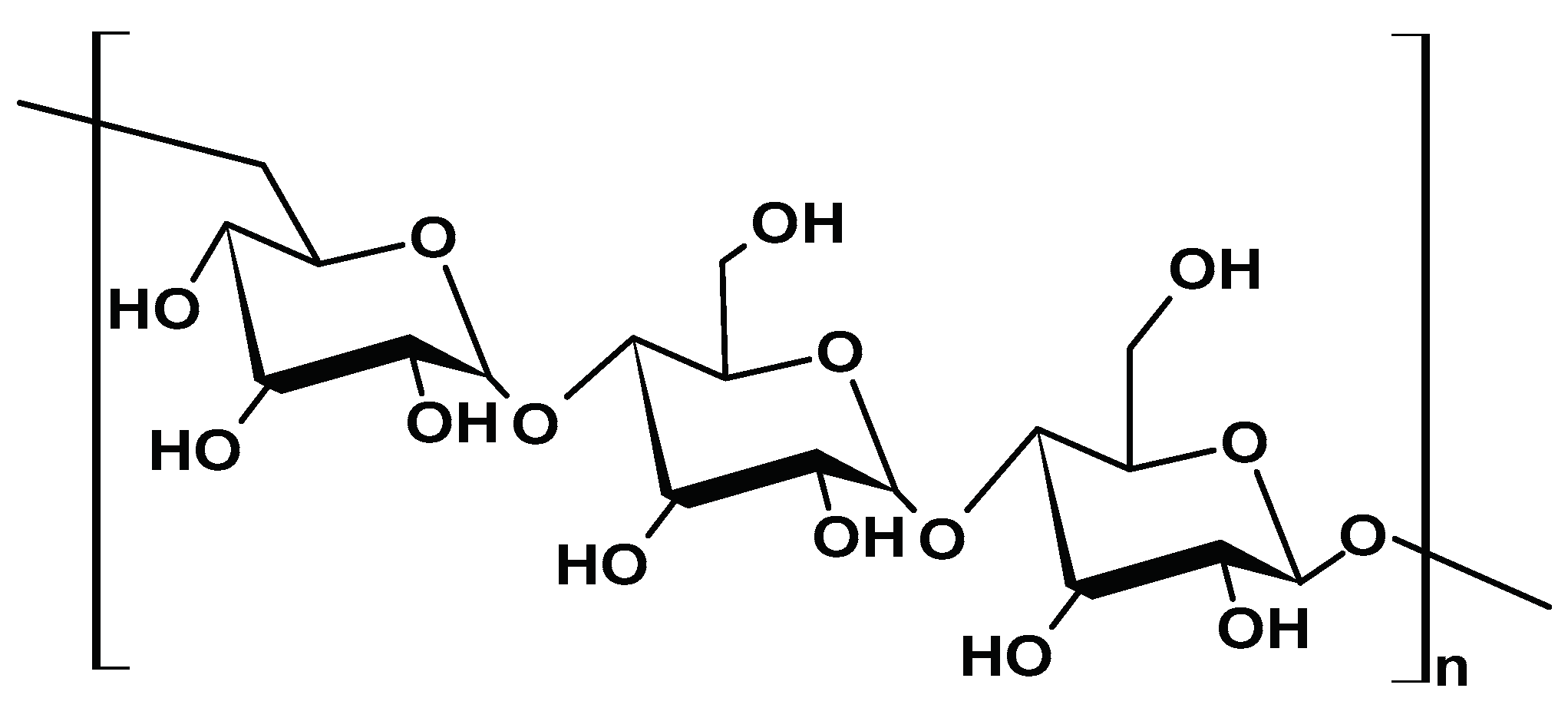

2.1.8. Pullulan

2.1.9. Agarose

2.2. Protein-Based Materials

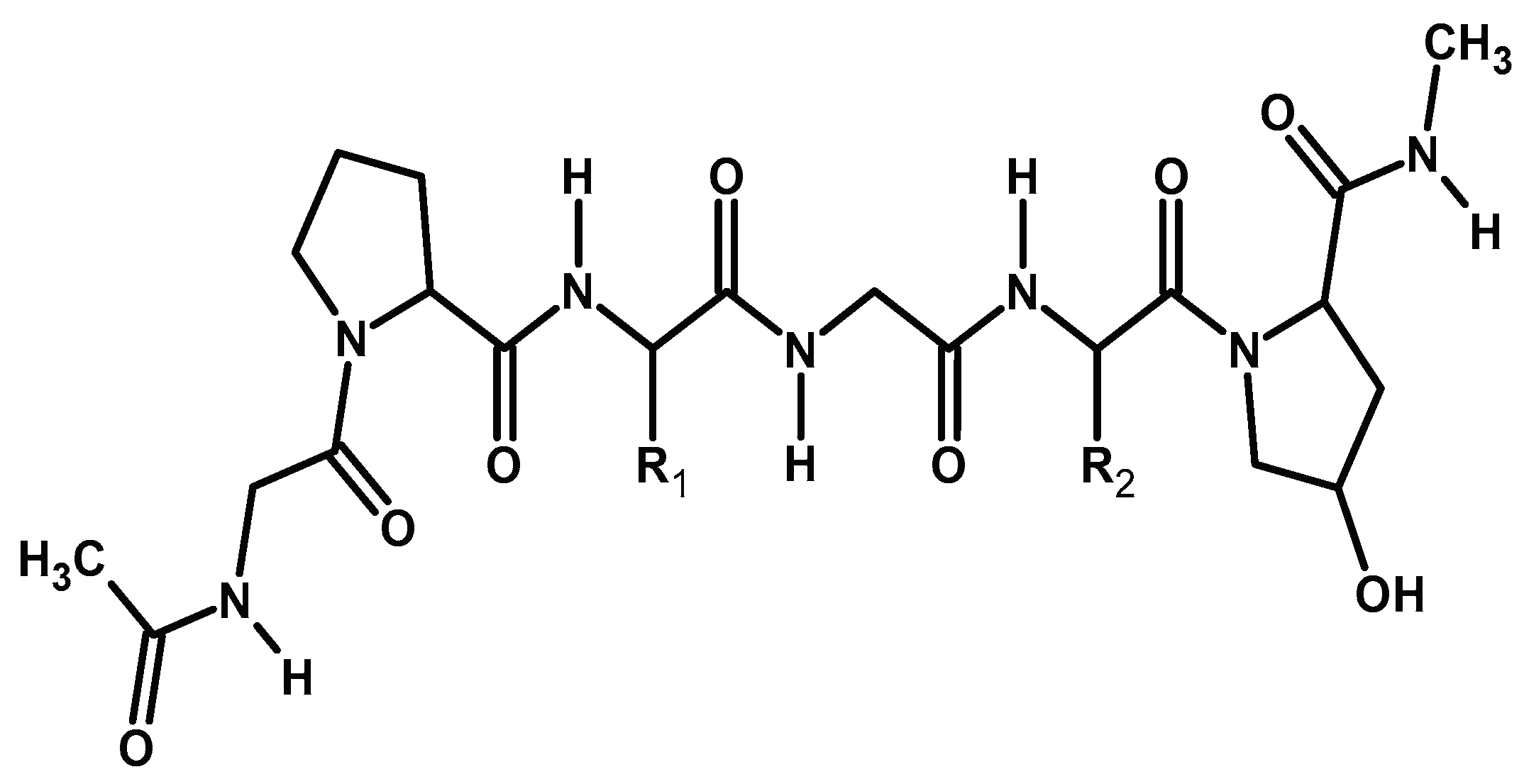

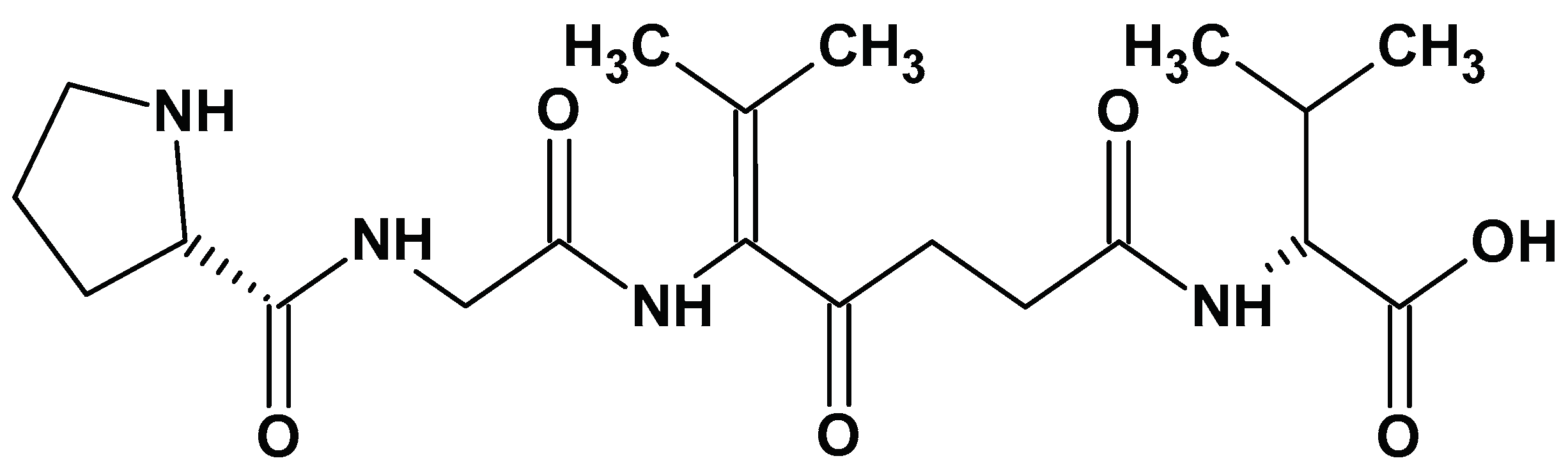

2.2.1. Collagen

2.2.2. Gelatine

2.2.3. Silk

2.2.4. Fibrin

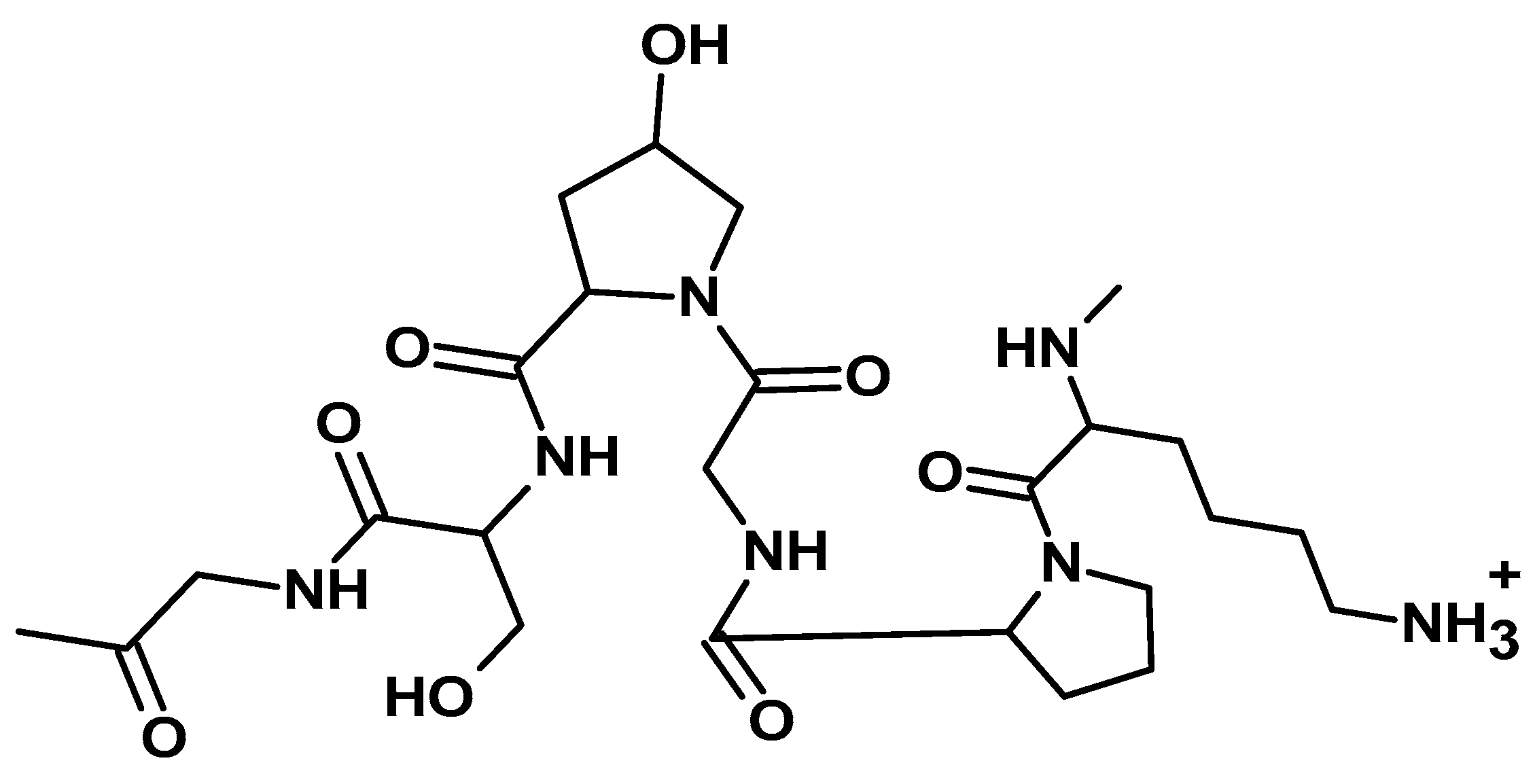

2.2.5. Elastin

2.2.6. Soy Protein

2.2.7. Whey Protein

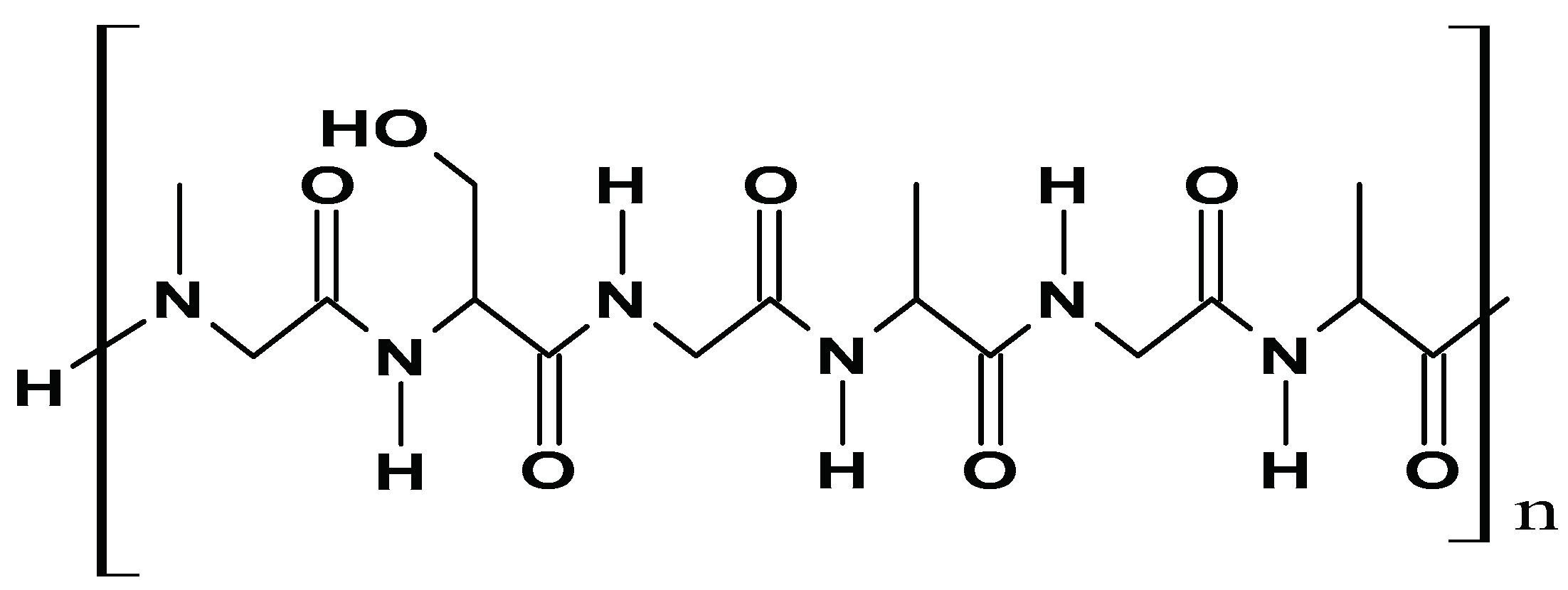

2.2.8. Resilin

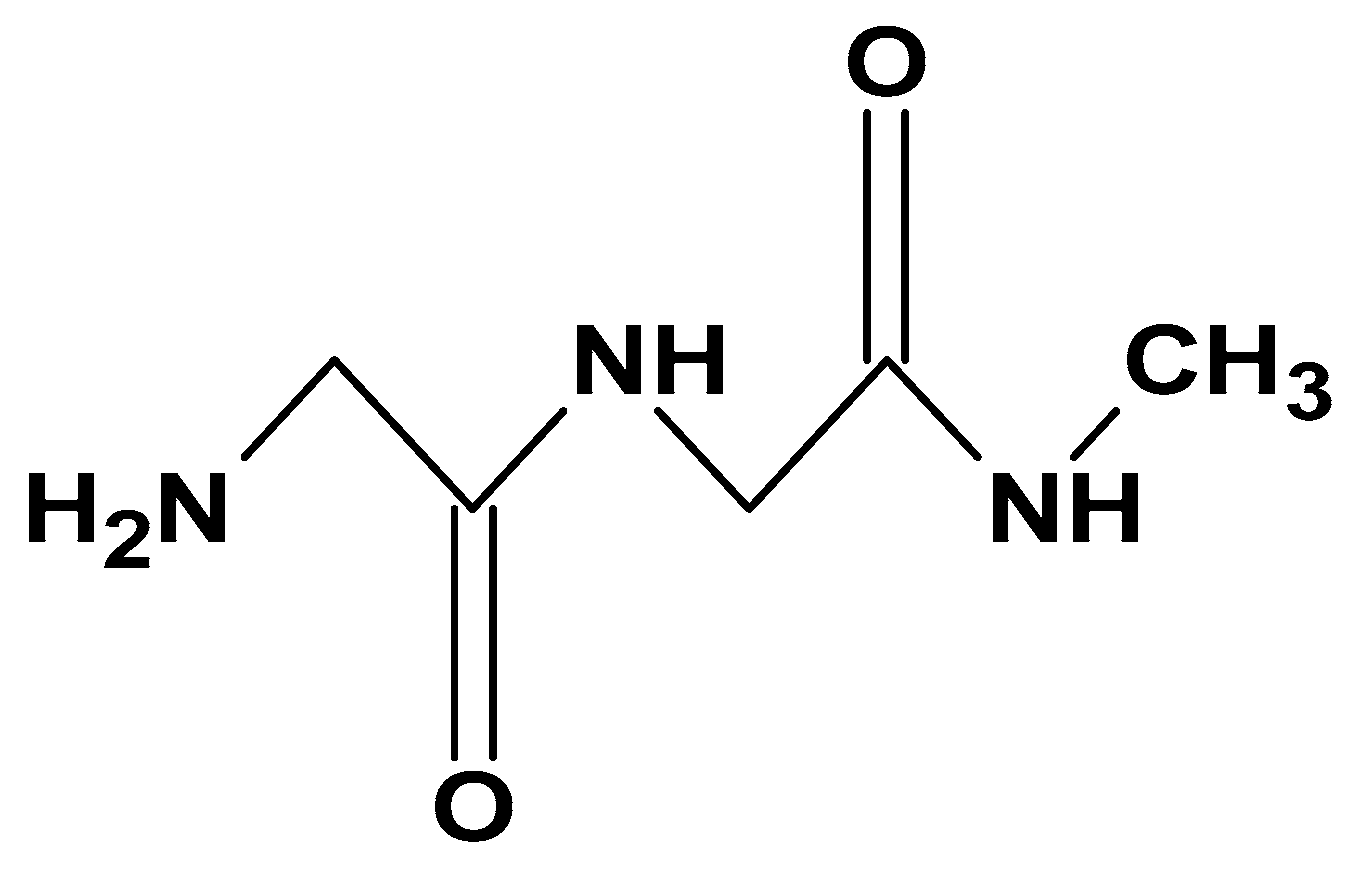

2.3. Other Natural-Based Materials

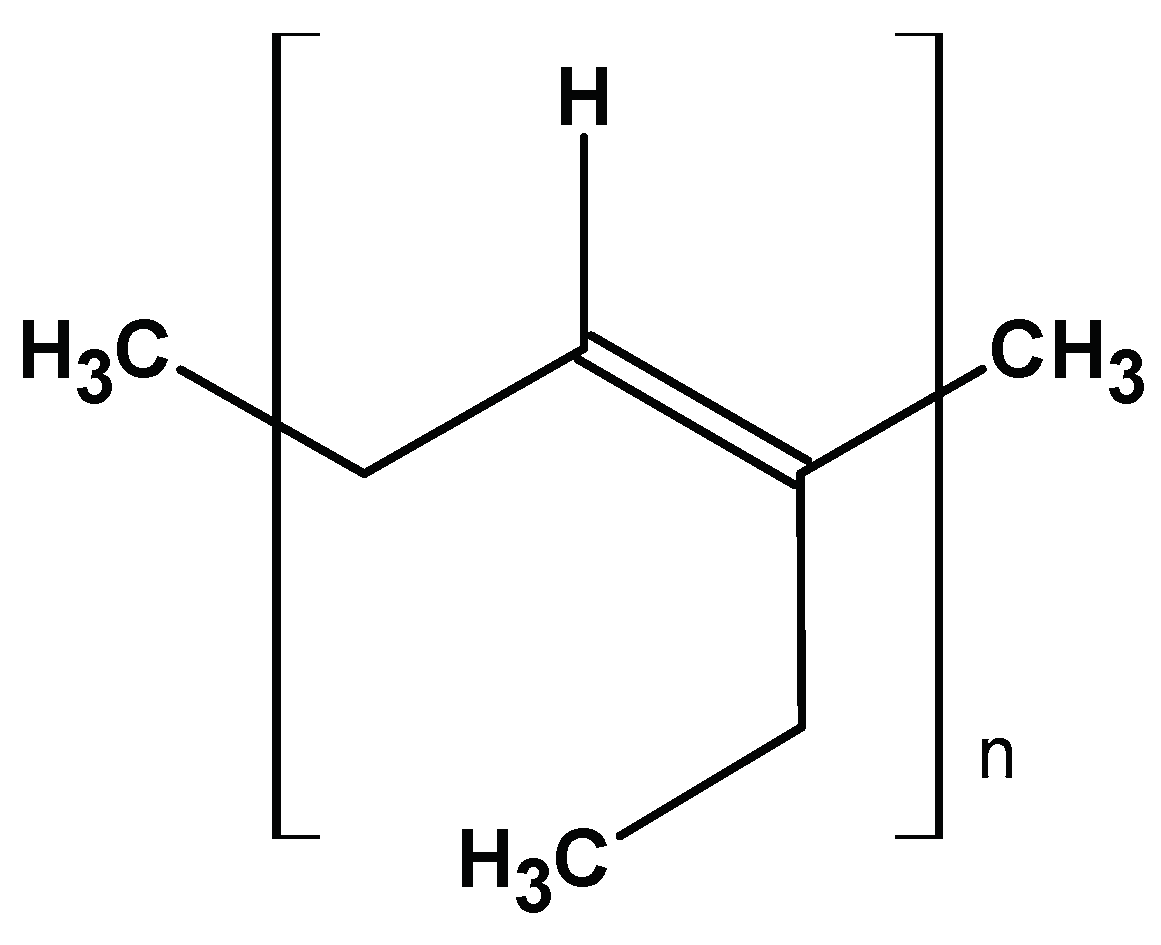

2.3.1. Polyisoprene

2.3.2. Plant Oils

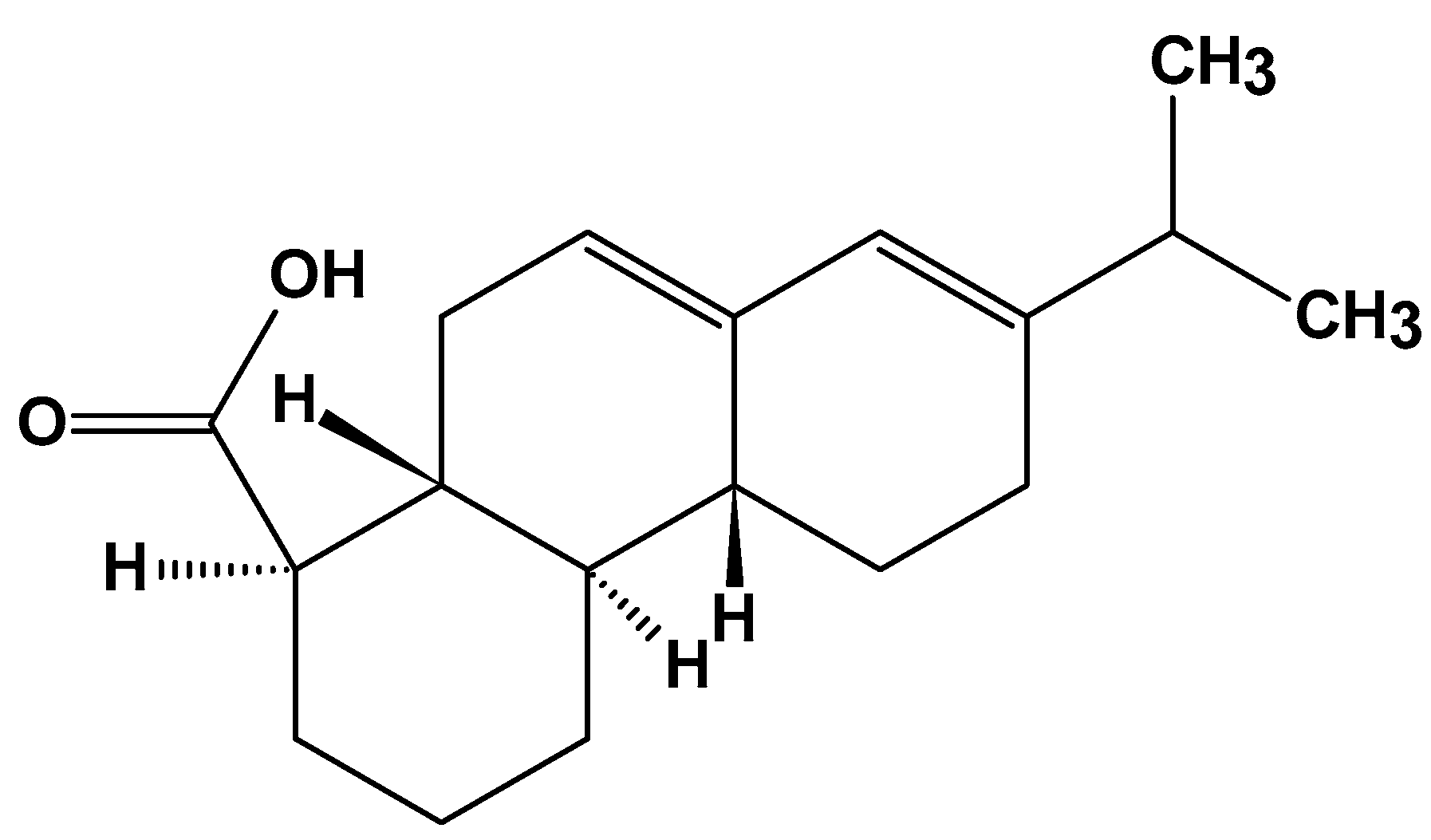

2.3.3. Rosin

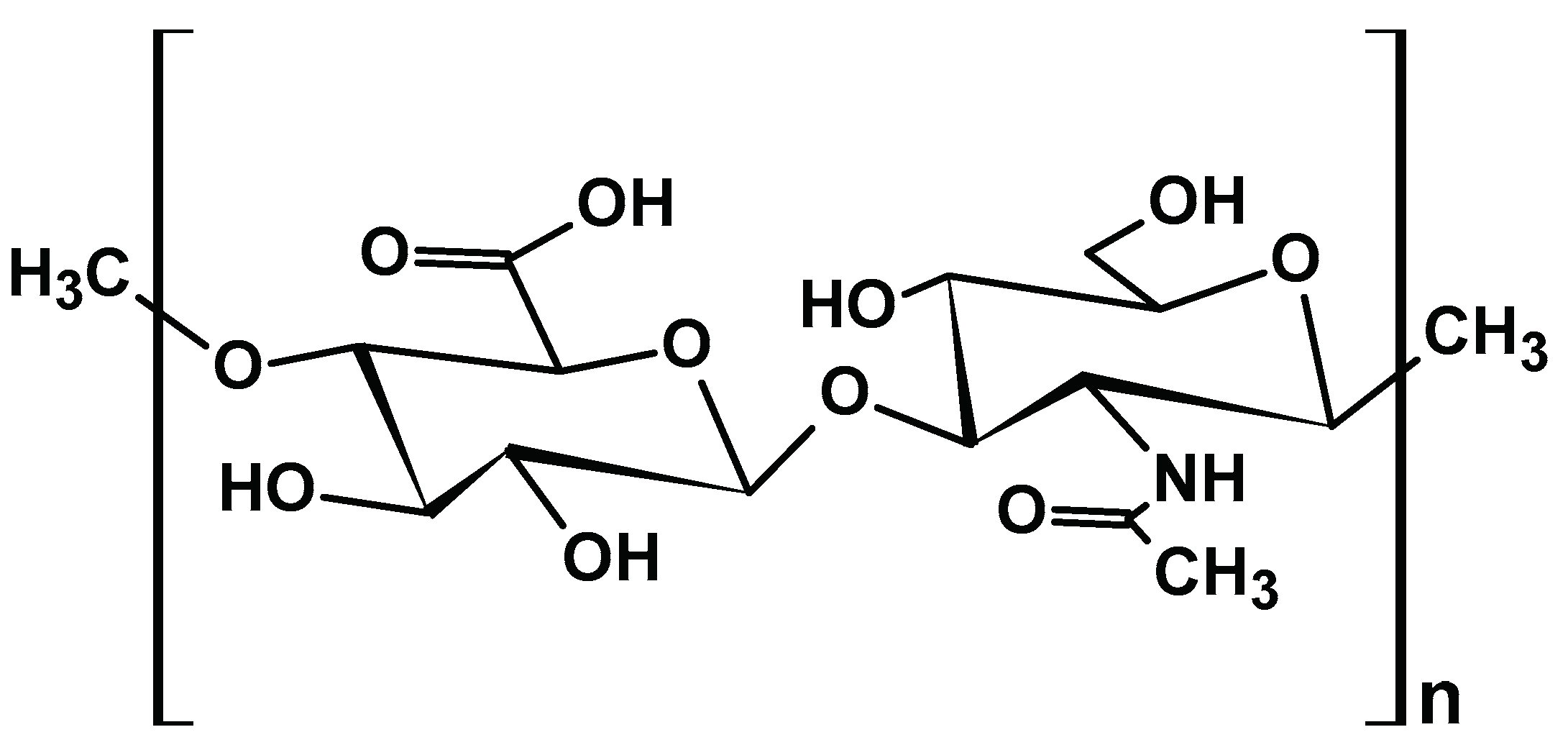

2.3.4. Hyaluronic Acid

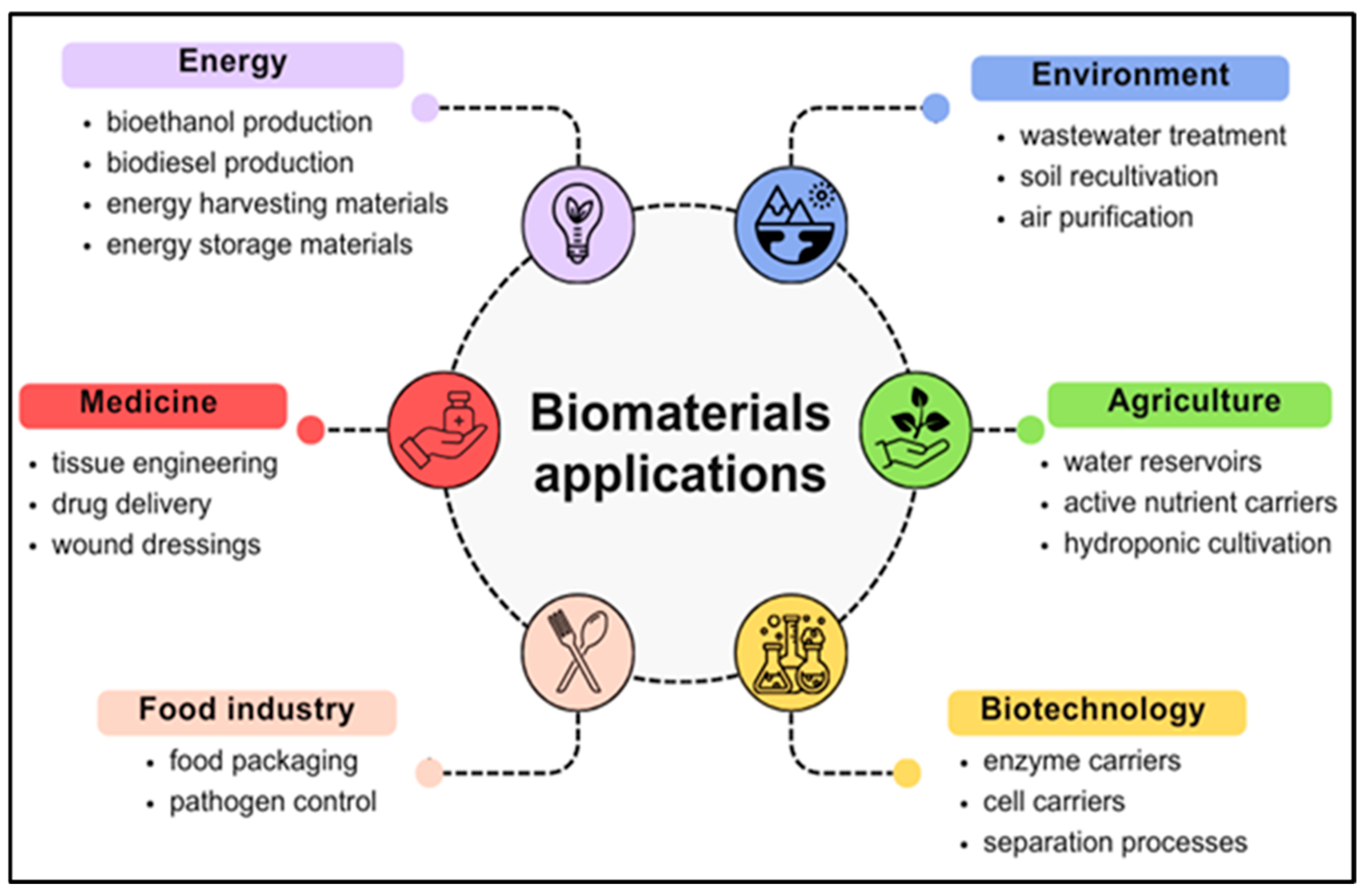

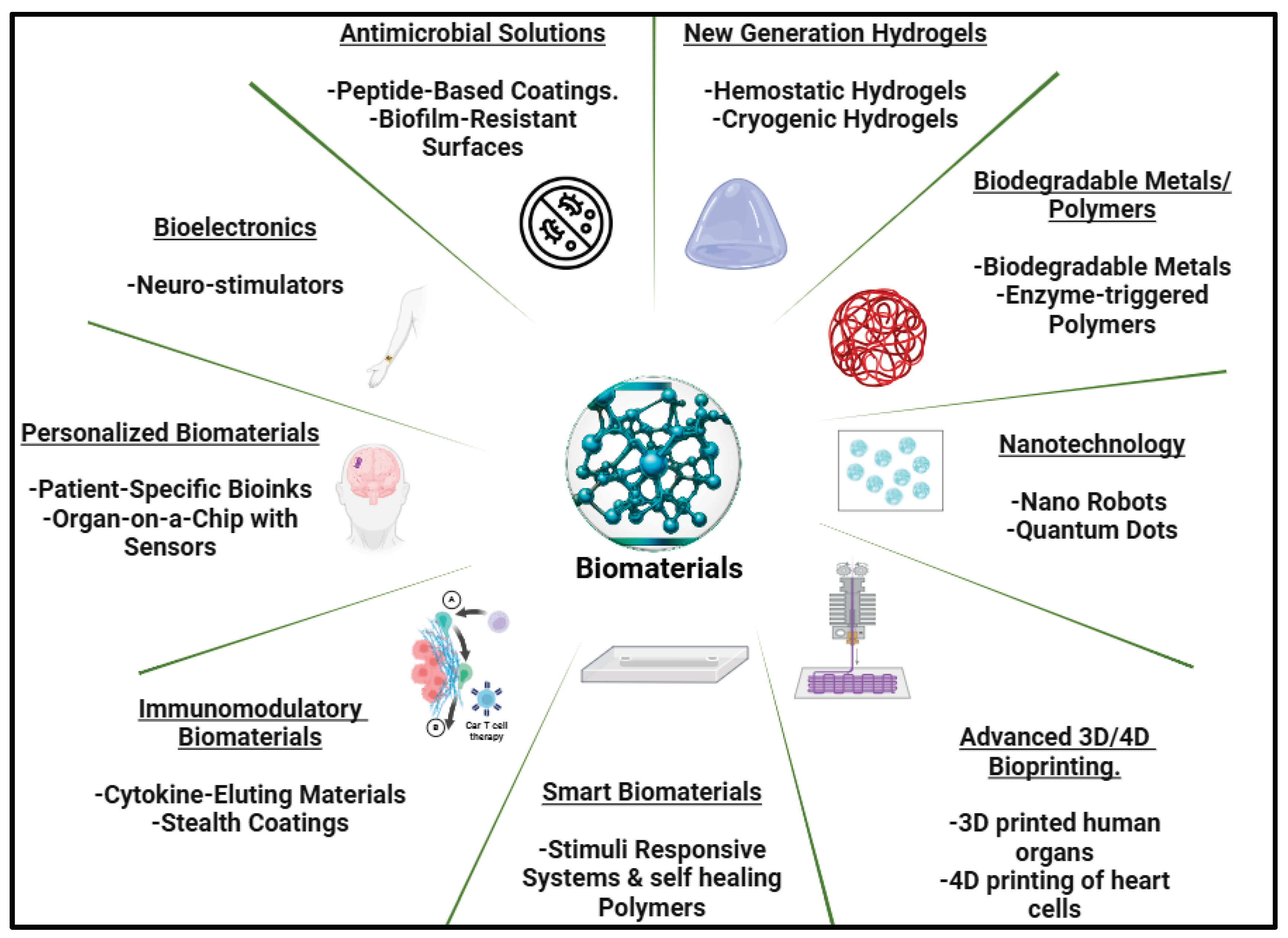

3. Innovations in the Application of Natural-Originated Polymeric Biomaterials

3.1. Energy Sector

3.2. Medical Sector

3.3. Environmental Sector

3.4. Construction Sector

3.5. Textile Sector

4. Future Development Trends

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Environment Programme, International Resource Panel. Global Resources Outlook 2024 – Bend the Trend: Pathways to a Liveable Planet as Resource Use Spikes; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2024. Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/handle/20.500.11822/44901 (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Le DL, Salomone R, Nguyen QT. Circular bio-based building materials: A literature review of case studies and sustainability assessment methods. Build. Environ. 2023, 244, 110774. [CrossRef]

- Tan ECD, Lamers P. Circular bioeconomy concepts—A perspective. Front. Sustain. 2021, 2, 701509. [CrossRef]

- Pandit P, Nadathur GT, Maiti S, Regubalan B. Functionality and properties of bio-based materials. In: Bio-Based Materials for Food Packaging: Green and Sustainable Advanced Packaging Materials; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 81–103. [CrossRef]

- Fusteș-Dămoc I, Dinu R, Măluțan T, Mija A. Valorisation of chitosan natural building block as a primary strategy for the development of sustainable fully bio-based epoxy resins. Polymers 2023, 15(24), 4627. [CrossRef]

- Nwabike Amitaye, A.; Elemike, E.E.; Akpeji, H.B.; Amitaye, E.; Hossain, I.; Mbonu, J.I.; et al. Chitosan: A Sustainable Biobased Material for Diverse Applications. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 1103381. [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.C.Q.; Silvestre, A.J.D.; Vilela, C.; Freire, C.S.R. Natural Polymers-Based Materials: A Contribution to a Greener Future. Molecules 2022, 27, 94. [CrossRef]

- Singhvi, M.S.; Zinjarde, S.S.; Gokhale, D.V. Polylactic Acid: Synthesis and Biomedical Applications. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 127, 1612–1626. [CrossRef]

- Rico-Llanos, G.A.; Borrego-González, S.; Moncayo-Donoso, M.; Becerra, J.; Visser, R. Collagen Type I Biomaterials as Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering. Polymers 2021, 13, 599. [CrossRef]

- Swetha, T.A.; Bora, A.; Mohanrasu, K.; Balaji, P.; Raja, R.; Ponnuchamy, K.; et al. A Comprehensive Review on Polylactic Acid (PLA) – Synthesis, Processing and Application in Food Packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 234, 123715. [CrossRef]

- Fijoł, N.; Aguilar-Sánchez, A.; Mathew, A.P. 3D-Printable Biopolymer-Based Materials for Water Treatment: A Review. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 430, 132801. [CrossRef]

- Andrew, J.J.; Dhakal, H.N. Sustainable Biobased Composites for Advanced Applications: Recent Trends and Future Opportunities—A Critical Review. Compos. Part C Open Access 2022, 7, 100220. [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, M.Z.A.; Rabbi, S.M.F.; Islam, M.D.; Hossain, N. Synthesis and Applications of Natural Fiber-Reinforced Epoxy Composites: A Comprehensive Review. SPE Polym. 2024, 5, e12345. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Q.; Li, R.; Li, B.; et al. Three-Dimensional Hierarchical and Interconnected Honeycomb-Like Porous Carbon Derived from Pomelo Peel for High Performance Supercapacitors. J. Solid State Chem. 2018, 257, 64–71. [CrossRef]

- Capêto, A.P.; Amorim, M.; Sousa, S.; Costa, J.R.; Uribe, B.; Guimarães, A.S.; et al. Fire-Resistant Bio-Based Polyurethane Foams Designed with Two By-Products Derived from Sugarcane Fermentation Process. Waste Biomass Valorization 2024, 15, 2045–2059. [CrossRef]

- Kore, S.D.; Sudarsan, J.S. Hemp Concrete: A Sustainable Green Material for Conventional Concrete. J. Build. Mater. Sci. 2021, 3, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.; Haufe, J.; Carus, M.; Brandão, M.; Bringezu, S.; Hermann, B.; et al. A Review of the Environmental Impacts of Biobased Materials. J. Ind. Ecol. 2012, 16, S169–S181. [CrossRef]

- Azeredo, H.M.C.; Barud, H.; Farinas, C.S.; Vasconcellos, V.M.; Claro, A.M. Bacterial Cellulose as a Raw Material for Food and Food Packaging Applications. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3, 7. [CrossRef]

- Gabryś, T.; Fryczkowska, B.; Fabia, J.; Biniaś, D. Preparation of an Active Dressing by In Situ Biosynthesis of a Bacterial Cellulose–Graphene Oxide Composite. Polymers 2022, 14, 2800. [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.C.Q.; Silvestre, A.J.D.; Vilela, C.; Freire, C.S.R. Natural Polymers-Based Materials: A Contribution to a Greener Future. Molecules 2022, 27, 94. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, G.K.; De, S.; Franco, A.; Balu, A.M.; Luque, R. Sustainable Biomaterials: Current Trends, Challenges and Applications. Molecules 2016, 21, 48. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Chen, X. Fabrication, Applications and Challenges of Natural Biomaterials in Tissue Engineering. Appl. Mater. Today 2020, 20, 100656. [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.C.Q.; Silvestre, A.J.D.; Vilela, C.; Freire, C.S.R. Natural Polymers-Based Materials: A Contribution to a Greener Future. Molecules 2022, 27, 94. [CrossRef]

- Dalwadi, S.; Goel, A.; Kapetanakis, C.; Salas-de la Cruz, D.; Hu, X. The Integration of Biopolymer-Based Materials for Energy Storage Applications: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3975. [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.M.; Heo, Y.; Do, K.; Ghosh, M.; Son, Y.O. Nanocellulose Derived from Agricultural Biowaste By-Products–Sustainable Synthesis, Biocompatibility, Biomedical Applications, and Future Perspectives: A Review. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2024, 8, 100529. [CrossRef]

- Ververis, C.; Georghiou, K.; Christodoulakis, N.; Santas, P.; Santas, R. Fiber Dimensions, Lignin and Cellulose Content of Various Plant Materials and Their Suitability for Paper Production. Ind. Crops Prod. 2004, 19, 245–254. [CrossRef]

- de Amorim, J.D.P.; de Souza, K.C.; Duarte, C.R.; da Silva Duarte, I.; de Assis Sales Ribeiro, F.; Silva, G.S.; et al. Plant and Bacterial Nanocellulose: Production, Properties and Applications in Medicine, Food, Cosmetics, Electronics and Engineering—A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 851–869. [CrossRef]

- Yassin, M.A.; Gad, A.A.M.; Ghanem, A.F.; Abdel Rehim, M.H. Green Synthesis of Cellulose Nanofibers Using Immobilized Cellulase. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 205, 255–260. https:/doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.10.087.

- Ventura-Cruz, S.; Tecante, A. Extraction and Characterization of Cellulose Nanofibers from Rose Stems (Rosa spp.). Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 220, 53–59. [CrossRef]

- Gabryś, T.; Fryczkowska, B.; Fabia, J.; Biniaś, D. Preparation of an Active Dressing by In Situ Biosynthesis of a Bacterial Cellulose–Graphene Oxide Composite. Polymers 2022, 14, 2805. [CrossRef]

- Tanskul, S.; Amornthatree, K.; Jaturonlak, N. A New Cellulose-Producing Bacterium, Rhodococcus sp. MI 2: Screening and Optimization of Culture Conditions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 92, 421–428. [CrossRef]

- Portela, R.; Leal, C.R.; Almeida, P.L.; Sobral, R.G. Bacterial Cellulose: A Versatile Biopolymer for Wound Dressing Applications. Microb. Biotechnol. 2019, 12, 586–610. [CrossRef]

- Betlej, I.; Antczak, A.; Szadkowski, J.; Drożdżek, M.; Krajewski, K.; Radomski, A.; et al. Evaluation of the Hydrolysis Efficiency of Bacterial Cellulose Gel Film after the Liquid Hot Water and Steam Explosion Pretreatments. Polymers 2022, 14, 2104. [CrossRef]

- Kirdponpattara, S.; Khamkeaw, A.; Sanchavanakit, N.; Pavasant, P.; Phisalaphong, M. Structural Modification and Characterization of Bacterial Cellulose–Alginate Composite Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 132, 146–155. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Cai, Z.; Lee, H.S.; Choi, G.S.; Lee, D.H.; Jo, C. Preparation and Characterization of a Bacterial Cellulose/Chitosan Composite for Potential Biomedical Application. J. Polym. Res. 2011, 18, 739–744. [CrossRef]

- Azeredo, H.M.C.; Barud, H.; Farinas, C.S.; Vasconcellos, V.M.; Claro, A.M. Bacterial Cellulose as a Raw Material for Food and Food Packaging Applications. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3, 7. [CrossRef]

- Zia, K.M.; Zia, F.; Zuber, M.; Rehman, S.; Ahmad, M.N. Alginate Based Polyurethanes: A Review of Recent Advances and Perspective. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 79, 377–387. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Tan, H. Alginate-Based Biomaterials for Regenerative Medicine Applications. Materials 2013, 6, 1285–1309. [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, A.; Aljabali, A.A.A.; Mishra, V.; Tambuwala, M.M.; Serrano-Aroca, Á. Alginate: Enhancement Strategies for Advanced Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4486. [CrossRef]

- Mati-Baouche, N.; Elchinger, P.H.; De Baynast, H.; Pierre, G.; Delattre, C.; Michaud, P. Chitosan as an Adhesive. Eur. Polym. J. 2014, 60, 198–212. [CrossRef]

- Alemu, D.; Getachew, E.; Mondal, A.K. Study on the Physicochemical Properties of Chitosan and Their Applications in the Biomedical Sector. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2023, 2023, 5025341. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Gómez, C.P.; Cecilia, J.A. Chitosan: A Natural Biopolymer with a Wide and Varied Range of Applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 3981. [CrossRef]

- Gadgey, K.K.; Bahekar, A. Investigation on Uses of Crab Based Chitin and Its Derivatives. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Technol. 2017, 8, 456–466. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315837234.

- Jiménez-Gómez, C.P.; Cecilia, J.A. Chitosan: A Natural Biopolymer with a Wide and Varied Range of Applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 3981. [CrossRef]

- Nwabike, A.A.; Elemike, E.E.; Akpeji, H.B.; Amitaye, E.; Hossain, I.; Mbonu, J.I.; et al. Chitosan: A Sustainable Biobased Material for Diverse Applications. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113208. [CrossRef]

- Fusteș-Dămoc, I.; Dinu, R.; Măluțan, T.; Mija, A. Valorisation of Chitosan Natural Building Block as a Primary Strategy for the Development of Sustainable Fully Bio-Based Epoxy Resins. Polymers 2023, 15, 4627. [CrossRef]

- Di Liberto, E.A.; Dintcheva, N.T. Biobased Films Based on Chitosan and Microcrystalline Cellulose for Sustainable Packaging Applications. Polymers 2024, 16, 568. [CrossRef]

- Kaewprachu, P.; Jaisan, C. Physicochemical Properties of Chitosan from Green Mussel Shells (Perna viridis): A Comparative Study. Polymers 2023, 15, 2816. [CrossRef]

- Kaewprachu, P.; Jaisan, C. Physicochemical Properties of Chitosan from Green Mussel Shells (Perna viridis): A Comparative Study. Polymers 2023, 15, 2816. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, D.; Batista-Silva, J.P.; Sousa, A.; Passarinha, L.A. Progress and Opportunities in Gellan Gum-Based Materials: A Review of Preparation, Characterization and Emerging Applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 311, 120732. [CrossRef]

- Dev, M.J.; Warke, R.G.; Warke, G.M.; Mahajan, G.B.; Patil, T.A.; Singhal, R.S. Advances in fermentative production, purification, characterization and applications of gellan gum. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 359, 127498. [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Zhu, L.; Guo, J.; Sun, Z.; Zhao, M.; Zhan, X. Enhancing biocompatibility and neuronal anti-inflammatory activity of polymyxin B through conjugation with gellan gum. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 147, 734–740. [CrossRef]

- Aliabadi, H.A.M.; Forouzandeh-Malati, M.; Hassanzadeh-Afruzi, F.; Noruzi, E.B.; Ganjali, F.; Kashtiaray, A.; et al. Magnetic xanthan gum-silk fibroin hydrogel: A nanocomposite for biological and hyperthermia applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127005. [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Giri, T.K. Hydrogels based on gellan gum in cell delivery and drug delivery. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 56, 101586. [CrossRef]

- Muthukumar, T.; Song, J.E.; Khang, G. Biological role of gellan gum in improving scaffold drug delivery, cell adhesion properties for tissue engineering applications. Molecules 2019, 24, 4514. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Hwang, H.S. Starch-Based Hydrogels as a Drug Delivery System in Biomedical Applications. Gels 2023, 9, 951. [CrossRef]

- Falua, K.J.; Pokharel, A.; Babaei-Ghazvini, A.; Ai, Y.; Acharya, B. Valorization of Starch to Biobased Materials: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 2215. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A. Recent Developments in Bio-Nanocomposites for Biomedical Applications; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2011..

- Casettari, L.; Bonacucina, G.; Morris, G.A.; Perinelli, D.R.; Lucaioli, P.; Cespi, M.; Palmieri, G.F. Dextran and its potential use as tablet excipient. Powder Technol. 2015, 273, 125–132. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Montes, E. Dextran: Sources, Structures, and Properties. Polysaccharides 2021, 2, 554–565. [CrossRef]

- Radke, W.; Held, D.; Bock, H.; Kilz, P. Molecular Weight Determination of Dextran According to USP/EP Monograph. Agilent Technologies, 2023. Available online: https://lcms.cz/labrulez-bucket-strapi-h3hsga3/an_wingpc_dextran_usp_ep_gpc_sec_5994_5763en_agilent_d1fd4c393f/an-wingpc-dextran-usp-ep-gpc-sec-5994-5763en-agilent.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2024)..

- Kavlak, S. Effects of Molecular Weight of Dextran on Dynamic Mechanical Properties in Functional Polymer Blend Systems. Hacettepe J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 50, 325–333. [CrossRef]

- García-Gareta, E.; Coathup, M.J.; Blunn, G.W. Osteoinduction of bone grafting materials for bone repair and regeneration. Bone 2015, 81, 112–121. [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Liu, G.L.; Jia, S.L.; Chi, Z.; Hu, Z.; Chi, Z.M. Pullulan biosynthesis and its regulation in Aureobasidium spp. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 251, 117020. [CrossRef]

- de Souza, C.K.; Ghosh, T.; Lukhmana, N.; Tahiliani, S.; Priyadarshi, R.; Hoffmann, T.G.; et al. Pullulan as a sustainable biopolymer for versatile applications: A review. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 36, 105469. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Patil, R.; Dubey, S.K.; Bahadur, P. Derivatization approaches and applications of pullulan. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 269, 296–308. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.S.; Kaur, N.; Kennedy, J.F. Pullulan production from agro-industrial waste and its applications in food industry: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 217, 46–57. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Katakura, O.; Morimoto, N.; Akiyoshi, K.; Kasugai, S. Effects of cholesterol-bearing pullulan (CHP)-nanogels in combination with prostaglandin E1 on wound healing. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2009, 91, 55–60. [CrossRef]

- Thangavel, P.; Vilvanathan, S.P.; Kuttalam, I.; Lonchin, S. Topical administration of pullulan gel accelerates skin tissue regeneration by enhancing collagen synthesis and wound contraction in rats. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 149, 395–403. [CrossRef]

- Autissier, A.; Letourneur, D.; Le Visage, C. Pullulan-based hydrogel for smooth muscle cell culture. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2007, 82, 336–342. [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, N.; Endo, T.; Iwasaki, Y.; Akiyoshi, K. Design of hybrid hydrogels with self-assembled nanogels as cross-linkers: Interaction with proteins and chaperone-like activity. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6, 1829–1834. [CrossRef]

- Brun-Graeppi, A.K.A.S.; Richard, C.; Bessodes, M.; Scherman, D.; Merten, O.W. Cell microcarriers and microcapsules of stimuli-responsive polymers. J. Control. Release 2011, 149, 209–224. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, W.; Lv, G.; Zhu, J.; Wang, W.; Ma, X.; et al. The Artificial Organ: Cell Encapsulation. In Comprehensive Biotechnology, 2nd ed.; Moo-Young, M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 99–114.

- Nilsson, K.; Scheirer, W.; Merten, O.W.; Östberg, L.; Liehl, E.; Katinger, H.W.D.; Mosbach, K. Entrapment of animal cells for production of monoclonal antibodies and other biomolecules. Nature 1983, 302, 629–630.

- Karoubi, G.; Ormiston, M.L.; Stewart, D.J.; Courtman, D.W. Single-cell hydrogel encapsulation for enhanced survival of human marrow stromal cells. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 5445–5455. [CrossRef]

- Parenteau-Bareil, R.; Gauvin, R.; Berthod, F. Collagen-Based Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering Applications. Materials 2010, 3, 1863–1887. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Pei, Y.; Tang, K.; Albu-Kaya, M.G. Structure, Extraction, Processing, and Applications of Collagen as an Ideal Component for Biomaterials—A Review. Collagen Leather 2023, 5, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Rico-Llanos, G.A.; Borrego-González, S.; Moncayo-Donoso, M.; Becerra, J.; Visser, R. Collagen Type I Biomaterials as Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering. Polymers 2021, 13, 599. [CrossRef]

- Rezvani Ghomi, E.; Nourbakhsh, N.; Akbari Kenari, M.; Zare, M.; Ramakrishna, S. Collagen-Based Biomaterials for Biomedical Applications. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2021, 109, 1986–1999. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Li, Z.; Zou, Y.; Lu, G.; Ronca, A.; D’Amora, U.; Chen, F.; Chen, Z.; Lin, H.; Fan, Y. Advanced Application of Collagen-Based Biomaterials in Tissue Repair and Restoration. J. Leather Sci. Eng. 2022, 4, 15. [CrossRef]

- Andreazza, R.; Morales, A.; Pieniz, S.; Labidi, J. Gelatin-Based Hydrogels: Potential Biomaterials for Remediation. Polymers 2023, 15(4), 1026. [CrossRef]

- Valcarcel, J.; Fraguas, J.; Hermida-Merino, C.; Hermida-Merino, D.; Piñeiro, M.M.; Vázquez, J.A. Production and Physicochemical Characterization of Gelatin and Collagen Hydrolysates from Turbot Skin Waste Generated by Aquaculture Activities. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19(9), 491. [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Wang, J.; Hao, Z.; Zhao, D. Gelatin-Based Biomaterials and Gelatin as an Additive for Chronic Wound Repair. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1398939. [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Bai, Q.; Wu, W.; Sun, N.; Cui, N.; Lu, T. Gelatin-Based Adhesive Hydrogel with Self-Healing, Hemostasis, and Electrical Conductivity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 183, 2142–2151. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, J.; Thakur, S.; Mamba, G.; Prateek; Gupta, R.K.; Thakur, V.K. Hydrogel of Gelatin in the Presence of Graphite for the Adsorption of Dye: Towards the Concept for Water Purification. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9(1), 104694. [CrossRef]

- Marciano, J.S.; Ferreira, R.R.; de Souza, A.G.; Barbosa, R.F.S.; de Moura Junior, A.J.; Rosa, D.S. Biodegradable Gelatin Composite Hydrogels Filled with Cellulose for Chromium (VI) Adsorption from Contaminated Water. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 181, 112–124. [CrossRef]

- Kumar Sahi, A.; Gundu, S.; Kumari, P.; Klepka, T.; Sionkowska, A. Silk-Based Biomaterials for Designing Bioinspired Microarchitecture for Various Biomedical Applications. Biomimetics 2023, 8(1), 55. [CrossRef]

- Le, B.H.T.; Minh, T.; Nguyen, D.; Minh, D. Naturally Derived Biomaterials: Preparation and Application. In Regenerative Medicine and Tissue Engineering; Andrades, J.A., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Saikia, S.; Saikia, M. Physical and Chemical Properties of Indian Silk Fibres. Pharma Innov. J. 2022, 11(3S), 732–738..

- Gamboa-Martínez, T.C.; Gómez Ribelles, J.L.; Gallego Ferrer, G. Fibrin Coating on Poly(L-lactide) Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering. J. Bioact. Compat. Polym. 2011, 26(5), 464–477. [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Murillo, J.A.; Simental-Mendía, M.A.; Moncada-Saucedo, N.K.; Delgado-Gonzalez, P.; Islas, J.F.; Roacho-Pérez, J.A.; et al. Physical, Mechanical, and Biological Properties of Fibrin Scaffolds for Cartilage Repair. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23(23), 14789. [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.C.; Barker, T.H. Fibrin-Based Biomaterials: Modulation of Macroscopic Properties through Rational Design at the Molecular Level. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10(4), 1502–1514. [CrossRef]

- Uzunova, Y.; Pilicheva, B.; Wein, S.; Schemmer, C.; Aischa, M.; Enezy-Ulbrich, A.; et al. Fibrin-Based Hydrogels with Reactive Amphiphilic Copolymers for Mechanical Adjustments Allow for Capillary Formation in 2D and 3D Environments. Gels 2024, 10(2), 123. [CrossRef]

- Bencherif, S.A. Fibrin: An Underrated Biopolymer for Skin Tissue Engineering. J. Regen. Med. 2017, 6(1), 1–5..

- Gonzalez de Torre, I.; Alonso, M.; Rodriguez-Cabello, J.C. Elastin-Based Materials: Promising Candidates for Cardiac Tissue Regeneration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 758. [CrossRef]

- Prado-Audelo, M.L.; Mendoza-Muñoz, N.; Escutia-Guadarrama, L.; Giraldo-Gomez, D.M.; González-Torres, M.; et al. Recent Advances in Elastin-Based Biomaterials. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 23(1), 1–15..

- Wang, K.; Meng, X.; Guo, Z. Elastin Structure, Synthesis, Regulatory Mechanism and Relationship with Cardiovascular Diseases. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 596622. [CrossRef]

- Tarakanova, A.; Chang, S.W.; Buehler, M.J. Computational Materials Science of Bionanomaterials: Structure, Mechanical Properties and Applications of Elastin and Collagen Proteins. In Handbook of Nanomaterials Properties; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 941–962. [CrossRef]

- Moscarelli, P.; Boraldi, F.; Bochicchio, B.; Pepe, A.; Salvi, A.M.; Quaglino, D. Structural Characterization and Biological Properties of the Amyloidogenic Elastin-Like Peptide (VGGVG)₃. Matrix Biol. 2014, 36, 15–27. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, S.; Jing, D.; Liu, N.; Luo, X. The Construction of Elastin-Like Polypeptides and Their Applications in Drug Delivery System and Tissue Repair. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21(1), 12. [CrossRef]

- Tansaz, S.; Boccaccini, A.R. Biomedical Applications of Soy Protein: A Brief Overview. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2016, 104, 553–569. [CrossRef]

- Chien, K.B.; Aguado, B.A.; Bryce, P.J.; Shah, R.N. In Vivo Acute and Humoral Response to Three-Dimensional Porous Soy Protein Scaffolds. Acta Biomater. 2013, 9, 8983–8990. [CrossRef]

- Peles, Z.; Binderman, I.; Berdicevsky, I.; Zilberman, M. Soy Protein Films for Wound-Healing Applications: Antibiotic Release, Bacterial Inhibition and Cellular Response. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2013, 7, 401–412. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xiao, M.; Dai, S.; Song, J.; Ni, X.; Fang, Y.; Corke, H.; Jiang, F. Interactions Between Carboxymethyl Konjac Glucomannan and Soy Protein Isolate in Blended Films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 101, 136–145. [CrossRef]

- Nishinari, K.; Fang, Y.; Guo, S.; Phillips, G.O. Soy Proteins: A Review on Composition, Aggregation and Emulsification. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 39, 301–318. [CrossRef]

- Shankar, A.; Seyam, A.F.M.; Hudson, S.M. Electrospinning of Soy Protein Fibers and Their Compatibility with Synthetic Polymers. J. Text. Appar. Technol. Manag. 2013, 8.

- Zhao, S.; Yao, J.; Fei, X.; Shao, Z.; Chen, X. An Antimicrobial Film by Embedding In Situ Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles in Soy Protein Isolate. Mater. Lett. 2013, 95, 142–144. [CrossRef]

- Gbassi, G.K.; Yolou, F.S.; Sarr, S.O.; Atheba, P.G.; Amin, C.N.; Ake, M. Whey Proteins Analysis in Aqueous Medium and in Artificial Gastric and Intestinal Fluids. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2012, 6, 1828–1837. [CrossRef]

- Sigma-Aldrich. Albumin from Bovine Serum. 2000. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/PL/pl/product/sigma/f7524 (accessed on 29 August 2024)..

- Sigma-Aldrich. Albumin from Bovine Serum. 2000. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/PL/pl/product/sigma/f7524 (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Rascón-Cruz, Q.; Espinoza-Sánchez, E.A.; Siqueiros-Cendón, T.S.; Nakamura-Bencomo, S.I.; Arévalo-Gallegos, S.; Iglesias-Figueroa, B.F. Lactoferrin: A Glycoprotein Involved in Immunomodulation, Anticancer, and Antimicrobial Processes. Molecules 2021, 26, 205. [CrossRef]

- Mehra, R.; Kumar, H.; Kumar, N.; Ranvir, S.; Jana, A.; Buttar, H.S.; et al. Whey Proteins Processing and Emergent Derivatives: An Insight Perspective from Constituents, Bioactivities, Functionalities to Therapeutic Applications. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 87, 104760. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, J.S.S.; Yan, S.; Pilli, S.; Kumar, L.; Tyagi, R.D.; Surampalli, R.Y. Cheese Whey: A Potential Resource to Transform into Bioprotein, Functional/Nutritional Proteins and Bioactive Peptides. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015, 33, 756–774. [CrossRef]

- Smithers, G.W. Whey and Whey Proteins—From “Gutter-to-Gold.” Int. Dairy J. 2008, 18, 695–704. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Hua, X.; Huang, L.; Xu, Y. Bio-Utilization of Cheese Manufacturing Wastes (Cheese Whey Powder) for Bioethanol and Specific Product (Galactonic Acid) Production via a Two-Step Bioprocess. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 272, 70–76. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Kiick, K.L. Resilin-Based Materials for Biomedical Applications. ACS Macro Lett. 2013, 2, 635–640. [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.; Fabry, B.; Boccaccini, A.R. Fibrous Protein-Based Hydrogels for Cell Encapsulation. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 6727–6738. [CrossRef]

- Su, R.S.C.; Kim, Y.; Liu, J.C. Resilin: Protein-Based Elastomeric Biomaterials. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 1601–1611. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wen, T. Estimation of C-MGARCH Models Based on the MBP Method. Stat. Probab. Lett. 2013, 83, 665–673. [CrossRef]

- Renner, J.N.; Cherry, K.M.; Su, R.S.C.; Liu, J.C. Characterization of Resilin-Based Materials for Tissue Engineering Applications. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 3678–3685. [CrossRef]

- Truong, M.Y.; Dutta, N.K.; Choudhury, N.R.; Kim, M.; Elvin, C.M.; Hill, A.J.; et al. A pH-Responsive Interface Derived from Resilin-Mimetic Protein Rec1-Resilin. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 4434–4446. [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.; Cornish, K.; Bahmankar, M.; Naghavi, M.R. Natural Rubber-Producing Sources, Systems, and Perspectives for Breeding and Biotechnology Studies of Taraxacum kok-saghyz. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 170, 113747. [CrossRef]

- Nurchi, C.; Buonvino, S.; Arciero, I.; Melino, S. Sustainable Vegetable Oil-Based Biomaterials: Synthesis and Biomedical Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12345. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Lee, Y.K.; Lee, D.S.; Yoo, J.E.; Shin, M.S.; Yamabe, N.; et al. Abietic Acid Isolated from Pine Resin (Resina Pini) Enhances Angiogenesis in HUVECs and Accelerates Cutaneous Wound Healing in Mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 203, 279–287. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Q.; Chen, Y. Rosin: A Comprehensive Review on Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, and Pharmacology. Fitoterapia 2024, 177, 105321. [CrossRef]

- Salwowska, N.M.; Bebenek, K.A.; Żądło, D.A.; Wcisło-Dziadecka, D.L. Physiochemical Properties and Application of Hyaluronic Acid: A Systematic Review. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2016, 15, 520–526. [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Segarra, M.; Tortosa, C.; Ruiz-Díez, C.; Desmaële, D.; Gea, T.; Barrena, R.; et al. A Plant-Like Battery: A Biodegradable Power Source Ecodesigned for Precision Agriculture. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 2900–2915. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Hou, H.; Yu, B.; Bai, J.; Guan, Y.; Wang, L.; et al. Fully Biodegradable and Long-Term Operational Primary Zinc Batteries as Power Sources for Electronic Medicine. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 5727–5739. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhang, Z.; Xiao, M.; Wang, S.; Huang, S.; Han, D.; et al. Polymeric Binders Used in Lithium Ion Batteries: Actualities, Strategies and Trends. ChemElectroChem 2024, 11, e202400123. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Yang, D.; Zhang, W.; Qiu, X.; Li, Q.; Li, C. Dual-Templated Synthesis of Mesoporous Lignin-Derived Honeycomb-Like Porous Carbon/SiO₂ Composites for High-Performance Li-Ion Battery. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2021, 111004. [CrossRef]

- Lahtinen, P. Berry Extracts and Nanocellulose as Bioactive Skin Sprays and Surgical Dressings to Prevent the Growth of Dangerous Microbes | VTT Finland. VTT Research 2024, Available online: https://www.vttresearch.com/en/news-and-ideas/berry-extracts-and-nanocellulose-bioactive-skin-sprays-and-surgical-dressings (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Bioretec Ltd. Renewing Orthopedics, Activa™. Bioretec 2024, Available online: https://bioretec.com/products/activa (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Emulate Inc. Culture of Innovation Leveraging Human Biology + Technology to Ignite a New Era in Human Health. Emulate Bio 2025, Available online: https://emulatebio.com/about/ (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Chen, J.; Zhao, C.; Liu, H.; Wang, Z.; Ma, L.; Zhang, J.; et al. Integrated Micro/Nano Drug Delivery System Based on Magnetically Responsive Phase-Change Droplets for Ultrasound Theranostics. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1323056. doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2024.1323056.

- Fouly, A.; Daoush, W.M.; Elqady, H.I.; Abdo, H.S. Fabrication of PMMA Nanocomposite Biomaterials Reinforced by Cellulose Nanocrystals Extracted from Rice Husk for Dental Applications. Friction 2024, 12, pp 2808–2825. [CrossRef]

- SmartReactors Inc. Cell Membrane: Mimicking the Human Lung. SmartReactors 2025, Available online: https://www.smartreactors.com/cellmembrane (accessed on 13 September 2024).

- Synakis Corp. Innovative Biomaterial-Based Treatments for Ocular Injuries and Diseases. Synakis 2024, Available online: https://synakis.com/ (accessed on 13 September 2024).

- Lin, X.; Zhang, D.; Chen, X.; Liu, M. Self-Cross-Linked Oxidized Sodium Alginate/Gelatin/Halloysite Hydrogel as Injectable, Adhesive, Antibacterial Dressing for Hemostasis. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 11444-11840. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Yang, L.; Luo, R.; Li, L.; Zheng, T.; Huang, K.; et al. A Drug-Free Cardiovascular Stent Functionalized with Tailored Collagen Supports In-Situ Healing of Vascular Tissues. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 11234. [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Li, J.; Tyagi, R.D.; Zhang, X. Carbon dioxide and methane as carbon source for the production of polyhydroxyalkanoates and concomitant carbon fixation. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 391, 129977. [CrossRef]

- Dhivagar, R.; Suraparaju, S.K.; Atamurotov, F.; Kannan, K.G.; Opakhai, S.; Omara, A.A.M. Performance analysis of snail shell biomaterials in solar still for clean water production: nature-inspired innovation for sustainability. Water Sci. Technol. 2024, 89, 3325–3343. [CrossRef]

- Vu, P.V.; Doan, T.D.; Tu, G.C.; Do, N.H.N.; Le, K.A.; Le, P.K. A novel application of cellulose aerogel composites from pineapple leaf fibers and cotton waste: removal of dyes and oil in wastewater. J. Porous Mater. 2022, 29, 1137–1147. [CrossRef]

- Ughetti, A.; Roncaglia, F.; Anderlini, B.; D’Eusanio, V.; Russo, A.L.; Forti, L. Integrated carbonate-based CO₂ capture-biofixation through cyanobacteria. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10779. [CrossRef]

- Ghazvinian, A.; Gürsoy, B. Mycelium-based composite graded materials: assessing the effects of time and substrate mixture on mechanical properties. Biomimetics 2022, 7, 48. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Liu, B.; Lee, S.H.; Lum, W.C.; Ren, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wang, H.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, J. Fabrication of rigid flame retardant foam using bio-based sucrose-furanic resin for building material applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 495, 153614. [CrossRef]

- Wachsmann, S.B.; Ruf, M.; Prinz, C.; Oehlsen, N.; Zhou, X.; Dyballa, M.; et al. Chitin/chitosan biocomposite foams with chitins from different organisms for sound absorption. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 11841-12269. [CrossRef]

- Hahn, J. TômTex™: Leather Alternative Biomaterial from Seafood Shells and Coffee Grounds. Dezeen 2020, Available online: https://www.dezeen.com/2020/08/22/tomtex-leather-alternative-biomaterial-seafood-shells-coffee/ (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Ochoa, C.; Iszauk, E. Bringing Life to Materials to Replace Plastics and Leather. Extantia Capital Blog 2025, Available online: https://medium.com/extantia-capital/bringing-life-to-materials-to-replace-plastics-and-leather-why-we-invested-in-modern-synthesis-cb4a2c022fe9 (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- MYCO Works™. Mushroom-Based ‘Leather’ Is Now a Scalable Alternative to Animal Leathers, Poised for Market Disruption. MycoWorks 2025, Available online: https://www.mycoworks.com/mushroom-based-leather-is-now-a-scalable-alternative-to-animal-leathers-poised-for-market-disruption (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Walker, K.T.; Keane, J.; Goosens, V.J.; Song, W.; Lee, K.Y.; Ellis, T. Self-pigmenting textiles grown from cellulose-producing bacteria with engineered tyrosinase expression. Nat. Biotechnol. 2024, in press. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Yan, C.; Zhang, X.; Yang, C.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, X. A sustainable platform of lignin: From bioresources to materials and their applications in rechargeable batteries and supercapacitors. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2020, 76, 100778. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Q.; Li, R.; Li, B.; et al. Three-dimensional hierarchical and interconnected honeycomb-like porous carbon derived from pomelo peel for high performance supercapacitors. J. Solid State Chem. 2018, 257, 64–71. [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Li, C.; Cao, J.; Cui, Z.; Du, J.; Fu, Z.; et al. Organ-on-a-chip meets artificial intelligence in drug evaluation. Theranostics 2023, 13, 4526–4558. 10.7150/thno.87266.

- Feng, C.; Deng, L.; Yong, Y.Y.; Wu, J.M.; Qin, D.L.; Yu, L.; et al. The application of biomaterials in spinal cord injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1. [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Zhang, D.; Chen, X.; Liu, M. Self-cross-linked oxidized sodium alginate/gelatin/halloysite hydrogel as injectable, adhesive, antibacterial dressing for hemostasis. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 11444-11840. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Yang, L.; Luo, R.; Li, L.; Zheng, T.; Huang, K.; et al. A drug-free cardiovascular stent functionalized with tailored collagen supports in-situ healing of vascular tissues. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 449022. [CrossRef]

- Swansea University. ProColl: Characterisation of Recombinant Human Procollagen. Swansea University 2024, Available online: https://www.swansea.ac.uk/medicine/enterprise-and-innovation/business-support-projects/accelerate-healthcare-technology-centre/procoll/ (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- ProColl. The Synthetic Biology Company Producing Best-in-Class Bovine and Animal-Free Collagen. ProColl 2025, Available online: https://www.procoll.co.uk/ (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Hasanpour, A.H.; Sepidarkish, M.; Mollalo, A.; Ardekani, A.; Almukhtar, M.; Mechaal, A.; et al. The global prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization in residents of elderly care centers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2023, 12, 82. [CrossRef]

- Mango Materials. The Future is Biodegradable. Mango Materials 2025, Available online: https://www.mangomaterials.com/ (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Capêto, A.P.; Amorim, M.; Sousa, S.; Costa, J.R.; Uribe, B.; Guimarães, A.S. Fire-Resistant Bio-Based Polyurethane Foams Designed with Two By-Products Derived from Sugarcane Fermentation Process. Waste Biomass Valor. 2024, 15, 2045–2059. [CrossRef]

- Vorländer, M. Auralization. Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [CrossRef]

- European Parliament. The Impact of Textile Production and Waste on the Environment (Infographics). European Parliament 2024, Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/en/article/20201208STO93327/the-impact-of-textile-production-and-waste-on-the-environment-infographics (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Skoczinski, P.; Carus, M.; Tweddle, G.; Ruiz, P.; Hark, N.; Zhang, A.; et al. Bio-Based Building Blocks and Polymers – Global Capacities, Production and Trends 2023–2028. Renewable Carbon 2024, Available online: https://renewable-carbon.eu/publications/product/bio-based-building-blocks-and-polymers-global-capacities-production-and-trends-2023-2028/ (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Resonant Link Medical. What Are Bioelectronic Devices and How Are They Fueling Healthcare Innovation. Resonant Link Medical 2025, Available online: https://www.rlmedical.com/resource/bioelectronic-devices-fueling-healthcare-innovation (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Wakefield, E. New Bioprinting Development May Lead to 3D Printed Human Organs. VoxelMatters 2025, Available online: https://www.voxelmatters.com/new-bioprinting-development-may-lead-to-3d-printed-human-organs/ (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Rana, M.M.; De la Hoz Siegler, H. Evolution of Hybrid Hydrogels: Next-Generation Biomaterials for Drug Delivery and Tissue Engineering. Gels 2024, 10, 96. [CrossRef]

- Oluwole, S.A.; Weldu, W.D.; Jayaraman, K.; Barnard, K.A.; Agatemor, C. Design Principles for Immunomodulatory Biomaterials. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2024, 7,8059-8075. [CrossRef]

- Negut, I.; Albu, C.; Bita, B. Advances in Antimicrobial Coatings for Preventing Infections of Head-Related Implantable Medical Devices. Coatings 2024, 14, 282. [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, I. What Are Biodegradable Metallic Materials? AZoM 2024, Available online: https://www.azom.com/article.aspx?ArticleID=23752 (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Weerarathna, I.N.; Kumar, P.; Dzoagbe, H.Y.; Kiwanuka, L. Advancements in Micro/Nanorobots in Medicine: Design, Actuation, and Transformative Application. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 11234–11246. [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Pujol, E.J.; Martínez, G.; Casado-Jurado, D.; Vázquez, J.; León-Barberena, J.; Rodríguez-Lucena, D.; et al. Hydrogels and Nanogels: Pioneering the Future of Advanced Drug Delivery Systems. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 334. [CrossRef]

- Raheem, A. Advancements in 3D-Printed Biomaterials for Personalized Medicine: A Review. Premier J. Sci. 2024, Available online: https://premierscience.com/pjs-24-282/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Park, J.E.; Kim, D.H. Advanced Immunomodulatory Biomaterials for Therapeutic Applications. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2024, 13, 2304125. [CrossRef]

- Bu, N.; Li, L.; Hu, X. Recent Trends in Natural Polymer-Based Hydrogels for Biomedical Applications. Biofunct. Mater. 2024, 2,1. [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Fang, J.; Shen, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, B.; Xu, Z.; et al. Advances of Naturally Derived Biomedical Polymers in Tissue Engineering. Front. Chem. 2024, . [CrossRef]

- Barhoum, A.; Sadak, O.; Ramirez, I.A.; Iverson, N. Stimuli-Bioresponsive Hydrogels as New Generation Materials for Implantable, Wearable, and Disposable Biosensors for Medical Diagnostics: Principles, Opportunities, and Challenges. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 317, 123–147. [CrossRef]

- Dai G.; et al. Biodegradable elastic hydrogels for bioprinting. U.S. Patent US11884765B2, 2023.

| Sector | Biomaterial type | Innovation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | Cellulose | A plant-like battery, also called a biodegradable battery | [127] |

| Gelatine hydrogel | Biodegradable primary zinc-molybdenum (Zn−Mo) battery with gelatin hydrogel electrolyte | [128] | |

| Algal biopolymers | Usage as electrodes, binders, electrolytes, and separators in batteries (green battery cycle---LixC6 and LiFePO4). | [129] | |

| Lignin-derived carbon | Mesoporous lignin-derived honeycomb-like porous carbon/SiO2 composites for high-performance Li-ion battery | [130] | |

| Medicine | Wild berry extract and nanocellulose | Antimicrobial skin sprays and surgical dressings | [131] |

| Poly L-lactide-co-glycolide copolymer (PLGA) | Production of polylactic acid (PLA) and polyglycolic acid (PGA) for the synthesis of bioabsorbable implants applied in orthopedics, cardiovascular interventions and tissue engineering to provide temporary support while facilitating tissue regeneration. | [132] | |

| Collagen, Fibrin and glycoproteins | Integrated in the development of organ on a chip (OoCs) that has great implication on drug testing, screening, disease modeling and personalized medicine | [133] | |

| Lipids-based membrane shells | Integrated micro/nano drug delivery system based on magnetically responsive phase-change droplets for ultrasound theranostics | [134] | |

| Cellulose Nanocrystals from Rice Husks. | Reinforce polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) nanocomposites for dental application. | [135] | |

| Nanocellulose | Nanocellulose membrane that propels artificial lung devices. | [136] | |

| Hyaluronan | Advanced hydrogel designed for precise ocular delivery | [137] | |

| Alginate and gelatine | Oxidized sodium alginate/gelatine/halloysite hydrogel used as an injectable, adhesive, and antibacterial dressing for hemostasis | [138] | |

| Collagen | Formulation of Drug-free coating functionalized with tailored collagen supports for vascular tissue healing. | [139] | |

| Environment | Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) from methanogens | Concurrent carbon capture (CO2 and CH4) and utilization by methanogens for PHA production | [140] |

| Snail shells | Snail shell biomaterials in solar still for clean water production. | [141] | |

| Cellulose | Cellulose from pineapple leaf fibers and cotton waste are used in making aerogel composites for the removal of dyes and oil in wastewater. | [142] | |

| Microalgae biomass | Integrated carbonate-based carbon capture and algae biofixation systems. | [143] | |

| Construction | Mycelium based composite (MBC) | MBC as load-bearing masonry components in construction | [144] |

| Sucrose | Rigid flame-retardant foam as a building material synthesized from Bio-based sucrose-furanic resin. | [145] | |

| Chitin and Chitosan | Chitin/chitosan composite foam for sound absorption | [146] | |

| Textile | Chitosan from mushroom and shrimp shells; bacterial cellulose; mycelium | Animal and petrochemical-free biotextile as alternative to conventional leather and textiles | [147]; [148]; [149] |

| Melanated bacterial cellulose from genetically engineered Komagataeibacter rhaeticus | Used as a self-pigmented biotextile | [150] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).