Submitted:

13 May 2025

Posted:

13 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Current Trends in the Functional Food Market

3. Fermented Foods as Antioxidant Sources

3.1. Dairy Products

3.2. Plant-Based Fermented Foods

3.3. Grain-Based Fermented Foods

3.4. Fermented Beverages

3.5. Non-Traditional Substrates

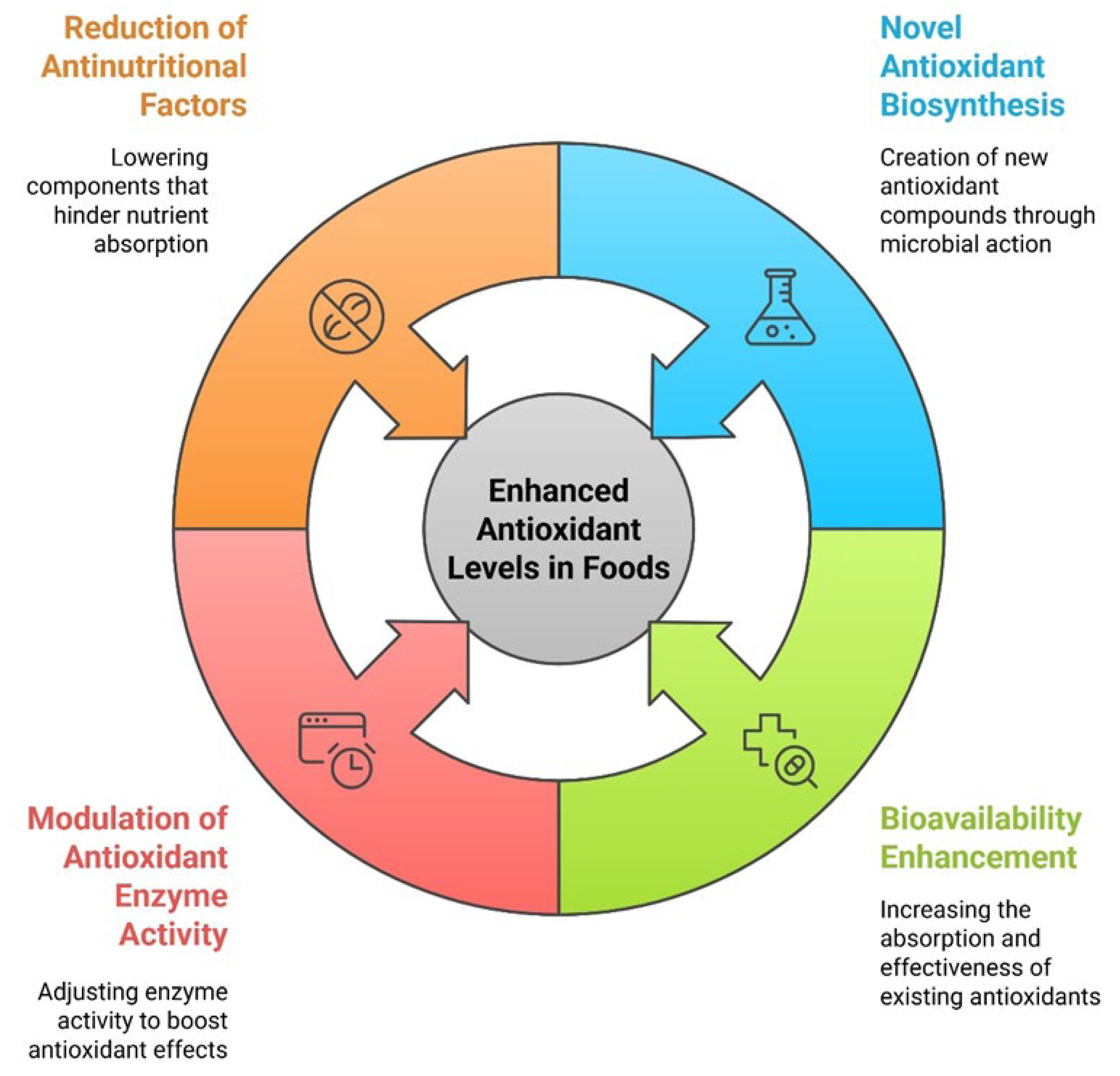

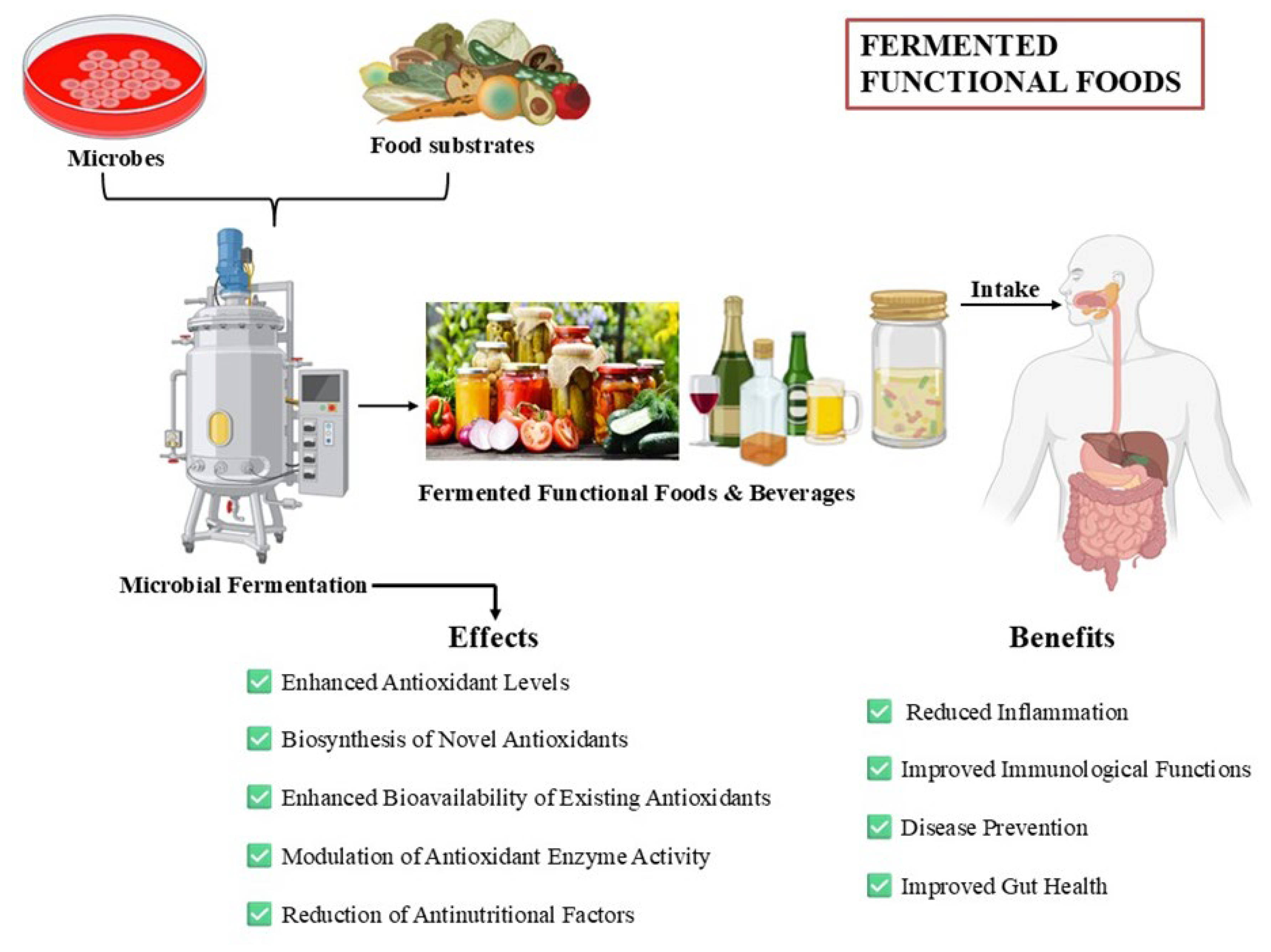

4. Microbes Driven Antioxidant Enhancement in Foods

4.1. Biosynthesis of Novel Antioxidants

4.2. Enhanced Bioavailability of Existing Antioxidants

4.3. Modulation of Antioxidant Enzyme Activity

4.4. Reduction of Antinutritional Factors

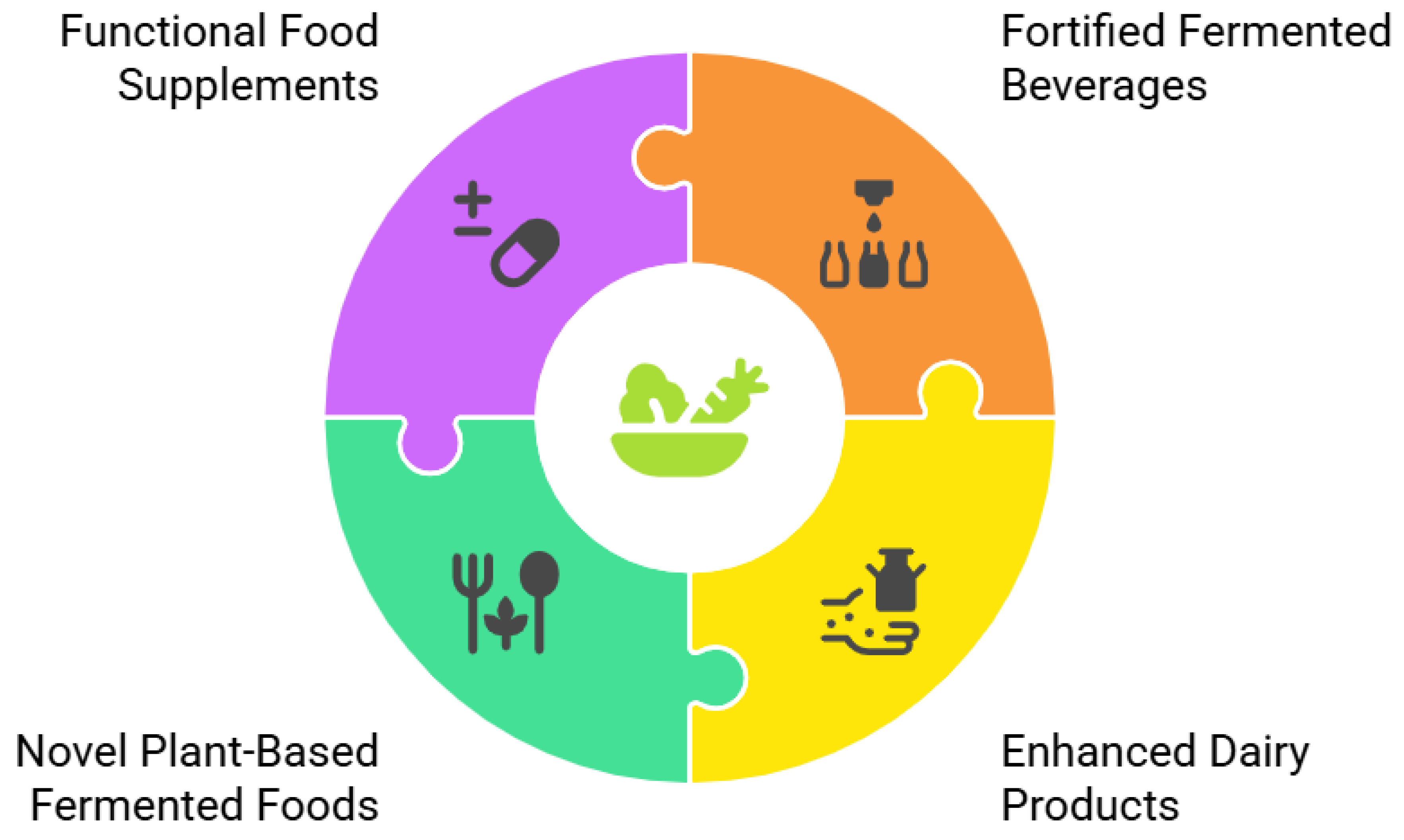

5. Novel Functional Food Development

5.1. Fortified Fermented Beverages

5.2. Enhanced Dairy Products

5.3. Novel Plant-Based Fermented Foods

5.4. Functional Food Supplements

6. Advances in Fermentation Technology for Antioxidant Production

6.1. Precision Fermentation and Microbial Engineering

6.2. Optimization of Fermentation Conditions

6.3. Advances in Bioreactor Design and Automation for Enhanced Antioxidant Production

6.4. Sustainable Practices: Upcycling Food Waste into Antioxidant-Rich Fermented Products

7. Challenges Associated with Fermented Functional Foods

7.1. Technical Challenges

7.1.1. Lack of Standardized Production Processes

7.1.2. Stability of Fermented Foods

7.1.3. Scale-Up Issues & Quality Control

7.2. Research Needs

8. Regulatory and Commercial Considerations

8.1. Regulatory Framework

8.2. Commercial Viability

9. Future Opportunities

10. Conclusions

Funding

Credit Authorship Contribution Statement

Data availability

Acknowledgement

Conflict of Interest

References

- Pizzino, G.; Irrera, N.; Cucinotta, M.; Pallio, G.; Mannino, F.; Arcoraci, V.; Squadrito, F.; Altavilla, D.; Bitto, A. Oxidative Stress: Harms and Benefits for Human Health. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2017, 2017, 8416763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscolo, A.; Mariateresa, O.; Giulio, T.; Mariateresa, R. Oxidative Stress: The Role of Antioxidant Phytochemicals in the Prevention and Treatment of Diseases. IJMS 2024, 25, 3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suruga, K.; Tomita, T.; Kadokura, K. Soybean Fermentation with Basidiomycetes (Medicinal Mushroom Mycelia). Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2020, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gille, D.; Schmid, A.; Walther, B.; Vergères, G. Fermented Food and Non-Communicable Chronic Diseases: A Review. Nutrients 2018, 10, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, G.; Arnone, A.; Ciampaglia, R.; Tenore, G.C.; Novellino, E. Fermentation of Foods and Beverages as a Tool for Increasing Availability of Bioactive Compounds. Focus on Short-Chain Fatty Acids. Foods 2020, 9, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Diwan, B.; Singh, B.P.; Kulshrestha, S. Probiotic Fermentation of Polyphenols: Potential Sources of Novel Functional Foods. Food Prod Process and Nutr 2022, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivamaruthi, B.S.; Kesika, P.; Prasanth, M.I.; Chaiyasut, C. A Mini Review on Antidiabetic Properties of Fermented Foods. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, M.L.; Heeney, D.; Binda, S.; Cifelli, C.J.; Cotter, P.D.; Foligné, B.; Gänzle, M.; Kort, R.; Pasin, G.; Pihlanto, A.; et al. Health Benefits of Fermented Foods: Microbiota and Beyond. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2017, 44, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimidi, E.; Cox, S.; Rossi, M.; Whelan, K. Fermented Foods: Definitions and Characteristics, Impact on the Gut Microbiota and Effects on Gastrointestinal Health and Disease. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saud, S.; Xiaojuan, T.; Fahad, S. The Consequences of Fermentation Metabolism on the Qualitative Qualities and Biological Activity of Fermented Fruit and Vegetable Juices. Food Chemistry: X 2024, 21, 101209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djorgbenoo, R.; Hu, J.; Hu, C.; Sang, S. Fermented Oats as a Novel Functional Food. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellone, V.; Bancalari, E.; Rubert, J.; Gatti, M.; Neviani, E.; Bottari, B. Eating Fermented: Health Benefits of LAB-Fermented Foods. Foods 2021, 10, 2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, K.L.; Hansen, C.; Hecht, E.E. Fermentation Technology as a Driver of Human Brain Expansion. Commun Biol 2023, 6, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longoria-García, S.; Cruz-Hernández, M.A.; Flores-Verástegui, M.I.M.; Contreras-Esquivel, J.C.; Montañez-Sáenz, J.C.; Belmares-Cerda, R.E. Potential Functional Bakery Products as Delivery Systems for Prebiotics and Probiotics Health Enhancers. J Food Sci Technol 2018, 55, 833–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Hong, J.; Wang, L.; Cai, C.; Mo, H.; Wang, J.; Fang, X.; Liao, Z. Effect of Lactic Acid Bacteria Fermentation on Plant-Based Products. Fermentation 2024, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martirosyan, D.; Alvarado, A. Functional Foods Regulation System: Proposed Regulatory Paradigm by Functional Food Center. FFS 2023, 3, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Functional Food Market Size, Growth and Forecast by 2033 Available online:. Available online: https://straitsresearch.com/report/functional-food-market (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Rai, S.; Wai, P.P.; Koirala, P.; Bromage, S.; Nirmal, N.P.; Pandiselvam, R.; Nor-Khaizura, M.A.R.; Mehta, N.K. Food Product Quality, Environmental and Personal Characteristics Affecting Consumer Perception toward Food. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1222760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martirosyan, D.; Stratton, S. Advancing Functional Food Regulation. BCHD 2023, 6, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goksen, G.; Demir, D.; Dhama, K.; Kumar, M.; Shao, P.; Xie, F.; Echegaray, N.; Lorenzo, J.M. Mucilage Polysaccharide as a Plant Secretion: Potential Trends in Food and Biomedical Applications. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 230, 123146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashtiban, A.E.; Okpala, C.O.R.; Karimidastjerd, A.; Zahedinia, S. Recent Advances in Nano-Related Natural Antioxidants, Their Extraction Methods and Applications in the Food Industry. Explor Foods Foodomics 2024, 2, 125–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Oliver, M.; Ponce-Alquicira, E. Environmentally Friendly Techniques and Their Comparison in the Extraction of Natural Antioxidants from Green Tea, Rosemary, Clove, and Oregano. Molecules 2021, 26, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, K.; Srivastav, S.; Sharanagat, V.S. Ultrasound Assisted Extraction (UAE) of Bioactive Compounds from Fruit and Vegetable Processing by-Products: A Review. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2021, 70, 105325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petcu, C.D.; Tăpăloagă, D.; Mihai, O.D.; Gheorghe-Irimia, R.-A.; Negoiță, C.; Georgescu, I.M.; Tăpăloagă, P.R.; Borda, C.; Ghimpețeanu, O.M. Harnessing Natural Antioxidants for Enhancing Food Shelf Life: Exploring Sources and Applications in the Food Industry. Foods 2023, 12, 3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imeneo, V.; Piscopo, A.; Santacaterina, S.; De Bruno, A.; Poiana, M. Sustainable Recovery of Antioxidant Compounds from Rossa Di Tropea Onion Waste and Application as Ingredient for White Bread Production. Sustainability 2023, 16, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safdar, M.N.; Baig, U.Y.; Riaz, M.M.; Mumtaz, A.; Jabbar, S.; E-Zehra, D.; Ur-Rehman, N.; Ahmad, Z.; Malik, H.; Yousaf, S. Extraction of Polyphenols from Different Herbs for the Development of Functional Date Bars. Food Sci. Technol 2022, 42, e43521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, S.A.; Emire, S.A. Production and Processing of Antioxidant Bioactive Peptides: A Driving Force for the Functional Food Market. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stobiecka, M.; Król, J.; Brodziak, A. Antioxidant Activity of Milk and Dairy Products. Animals 2022, 12, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanakis, C.M.; Rizou, M.; Aldawoud, T.M.S.; Ucak, I.; Rowan, N.J. Innovations and Technology Disruptions in the Food Sector within the COVID-19 Pandemic and Post-Lockdown Era. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2021, 110, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentino, V.; Magliulo, R.; Farsi, D.; Cotter, P.D.; O’Sullivan, O.; Ercolini, D.; De Filippis, F. Fermented Foods, Their Microbiome and Its Potential in Boosting Human Health. Microbial Biotechnology 2024, 17, e14428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, P.; Pulina, S.; Del Caro, A.; Fadda, C.; Urgeghe, P.P.; De Bruno, A.; Difonzo, G.; Caponio, F.; Romeo, R.; Piga, A. Gluten-Free Breadsticks Fortified with Phenolic-Rich Extracts from Olive Leaves and Olive Mill Wastewater. Foods 2021, 10, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Lao, F.; Pan, X.; Wu, J. Food Protein-Derived Antioxidant Peptides: Molecular Mechanism, Stability and Bioavailability. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogel-Castillo, C.; Latorre-Castañeda, M.; Muñoz-Muñoz, C.; Agurto-Muñoz, C. Seaweeds in Food: Current Trends. Plants 2023, 12, 2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuamatzin-García, L.; Rodríguez-Rugarcía, P.; El-Kassis, E.G.; Galicia, G.; Meza-Jiménez, M.D.L.; Baños-Lara, Ma.D.R.; Zaragoza-Maldonado, D.S.; Pérez-Armendáriz, B. Traditional Fermented Foods and Beverages from around the World and Their Health Benefits. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, T.S.; Chin, Y.L.; Chai, K.F.; Chen, W.N. Fermentation for Future Food Systems: Precision Fermentation Can Complement the Scope and Applications of Traditional Fermentation. EMBO Reports 2021, 22, e52680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M.-J. Fermented Foods and Food Microorganisms: Antioxidant Benefits and Biotechnological Advancements. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarıtaş, S.; Duman, H.; Karav, S. Nutritional and Functional Aspects of Fermented Algae. International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2024, 59, 5270–5284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaneva, T.; Dinkova, R.; Gotcheva, V.; Angelov, A. Modulation of the Antioxidant Activity of a Functional Oat Beverage by Enrichment with Chokeberry Juice. Food Processing Preservation 2022, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhao, F.; Li, L.; Zhang, J.; Wu, S.; Lü, X.; Zhang, H.; Yi, Y. Enhancing the Antioxidant Capacity and Quality Attributes of Fermented Goat Milk through the Synergistic Action of Limosilactobacillus Fermentum WXZ 2-1 with a Starter Culture. Journal of Dairy Science 2024, 107, 1928–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isık, S.; Dagdemir, E.; Tekin, A.; Hayaloglu, A.A. Metabolite Profiling of Fermented Milks as Affected by Adjunct Cultures during Long-Term Storage. Food Bioscience 2023, 56, 103344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.-C.; Liu, Y.-H.; Lin, S.-P.; Santoso, S.P.; Jantama, K.; Tsai, T.-Y.; Hsieh, C.-W.; Cheng, K.-C. Development of High-Glucosinolate-Retaining Lactic-Acid-Bacteria-Co-Fermented Cabbage Products. Fermentation 2024, 10, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, Z.; Saeed, F.; Nosheen, F.; Ahmed, A.; Anjum, F.M. Comparative Study of Nutritional Properties and Antioxidant Activity of Raw and Fermented (Black) Garlic. International Journal of Food Properties 2022, 25, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Gao, M.; Li, L.; Jiang, H.; Liu, Y.; Gu, T.; Zhang, J. Functional Components and Antioxidant Activity Were Improved in Ginger Fermented by Bifidobacterium Adolescentis and Monascus Purpureus. LWT 2024, 197, 115931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jiang, J.; Li, Y.; Xie, Y.; Cui, M.; Hu, Y.; Yin, R.; Ma, X.; Niu, J.; Cheng, W.; et al. Enhancing Physicochemical Properties, Organic Acids, Antioxidant Capacity, Amino Acids and Volatile Compounds for ‘Summer Black’ Grape Juice by Lactic Acid Bacteria Fermentation. LWT 2024, 209, 116791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pejcz, E.; Lachowicz-Wiśniewska, S.; Nowicka, P.; Wojciechowicz-Budzisz, A.; Spychaj, R.; Gil, Z. Effect of Inoculated Lactic Acid Fermentation on the Fermentable Saccharides and Polyols, Polyphenols and Antioxidant Activity Changes in Wheat Sourdough. Molecules 2021, 26, 4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balli, D.; Cecchi, L.; Pieraccini, G.; Venturi, M.; Galli, V.; Reggio, M.; Di Gioia, D.; Furlanetto, S.; Orlandini, S.; Innocenti, M.; et al. Millet Fermented by Different Combinations of Yeasts and Lactobacilli: Effects on Phenolic Composition, Starch, Mineral Content and Prebiotic Activity. Foods 2023, 12, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubczyk, K.; Kałduńska, J.; Kochman, J.; Janda, K. Chemical Profile and Antioxidant Activity of the Kombucha Beverage Derived from White, Green, Black and Red Tea. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.-M.; Du, T.; Li, P.; Du, X.-J.; Wang, S. Production and Characterization of a Novel Low-Sugar Beverage from Red Jujube Fruits and Bamboo Shoots Fermented with Selected Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum. Foods 2021, 10, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Tan, Q.; Wu, S.; Abbas, B.; Yang, M. Application of Kombucha Fermentation Broth for Antibacterial, Antioxidant, and Anti-Inflammatory Processes. IJMS 2023, 24, 13984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niccolai, A.; Venturi, M.; Galli, V.; Pini, N.; Rodolfi, L.; Biondi, N.; D’Ottavio, M.; Batista, A.P.; Raymundo, A.; Granchi, L.; et al. Development of New Microalgae-Based Sourdough “Crostini”: Functional Effects of Arthrospira Platensis (Spirulina) Addition. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 19433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, L.P.; Vilela, H.; Solinho, J.; Pinheiro, R.; Belo, I.; Lopes, M. Enrichment of Fruit Peels’ Nutritional Value by Solid-State Fermentation with Aspergillus Ibericus and Rhizopus Oryzae. Molecules 2024, 29, 3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, T.R.; Feitosa, P.R.; Gualberto, N.C.; Narain, N.; Santana, L.C. Improvement of Bioactive Compounds Content in Granadilla ( Passiflora Ligularis ) Seeds after Solid-State Fermentation. Food sci. technol. int. 2021, 27, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbulut, M.; Çoklar, H.; Bulut, A.N.; Hosseini, S.R. Evaluation of Black Grape Pomace, a Fruit Juice By-product, in Shalgam Juice Production: Effect on Phenolic Compounds, Anthocyanins, Resveratrol, Tannin, and in Vitro Antioxidant Activity. Food Science & Nutrition 2024, 12, 4372–4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ye, F.; Zhou, Y.; Lei, L.; Chen, J.; Li, S.; Zhao, G. Tailoring the Composition, Antioxidant Activity, and Prebiotic Potential of Apple Peel by Aspergillus Oryzae Fermentation. Food Chemistry: X 2024, 21, 101134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobón-Suárez, A.; Giménez, M.J.; Gutiérrez-Pozo, M.; Zapata, P.J. Development of New Craft Beer Enriched with a By-Product of Orange. Acta Hortic. 2024, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, S.D.; Araújo, C.M.; Borges, G.D.S.C.; Lima, M.D.S.; Viera, V.B.; Garcia, E.F.; De Souza, E.L.; De Oliveira, M.E.G. Improvement in Physicochemical Characteristics, Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Acerola (Malpighia Emarginata D.C.) and Guava (Psidium Guajava L.) Fruit by-Products Fermented with Potentially Probiotic Lactobacilli. LWT 2020, 134, 110200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, S.D.; De Souza, E.L.; Araújo, C.M.; Martins, A.C.S.; Borges, G.D.S.C.; Lima, M.D.S.; Viera, V.B.; Garcia, E.F.; Da Conceição, M.L.; De Souza, A.L.; et al. Spontaneous Fermentation Improves the Physicochemical Characteristics, Bioactive Compounds, and Antioxidant Activity of Acerola (Malpighia Emarginata D.C.) and Guava (Psidium Guajava L.) Fruit Processing by-Products. 3 Biotech 2023, 13, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, N.; Bouajila, J.; Beaufort, S.; Rizk, Z.; Taillandier, P.; El Rayess, Y. Development of a New Kombucha from Grape Pomace: The Impact of Fermentation Conditions on Composition and Biological Activities. Beverages 2024, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, B.X.N.; Phan Van, T.; Phan, Q.K.; Pham, G.B.; Quang, H.P.; Do, A.D. Coffee Husk By-Product as Novel Ingredients for Cascara Kombucha Production. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 34, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Gómez, H.; Diez, M.; Abadias, M.; Rivera, A.; Aguiló-Aguayo, I. Promoting a Circular Economy by Developing New Gastronomic Products from Brassica Non-edible Leaves. Int J of Food Sci Tech 2024, 59, 1071–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, D.E.; Dikmetas, D.N.; Karbancioglu-Guler, F.; Tomas, M.; Capanoglu, E. Exploring the Impact of Fermentation on Bioactive Compounds in Two Different Types of Carrot Pomace. Food Bioscience 2024, 61, 104646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Shin, N.; Baik, S. Physicochemical Properties, Antioxidant Activity and Inhibition Ofα-glucosidase of a Novel Fermented Pepper ( C Apsiccum Annuum L.) Leaves-based Vinegar. Int J of Food Sci Tech 2014, 49, 2491–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Millán, J.Á.; Conesa-Bueno, A.; Aguayo, E. A Novel Antidiabetic Lactofermented Beverage from Agro-Industrial Waste (Broccoli Leaves): Process Optimisation, Phytochemical Characterisation, and Shelf-Life through Thermal Treatment and High Hydrostatic Pressure. Food Bioscience 2024, 59, 103999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioni, E.; Di Stasi, M.; Iacono, E.; Lai, M.; Quaranta, P.; Luminare, A.G.; Gambineri, F.; De Leo, M.; Pistello, M.; Braca, A. Enhancing Antimicrobial and Antiviral Properties of Cynara Scolymus L. Waste through Enzymatic Pretreatment and Lactic Fermentation. Food Bioscience 2024, 57, 103441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Fuentes, B.; De Jesús-José, E.; Cabrera-Hidalgo, A.D.J.; Sandoval-Castilla, O.; Espinosa-Solares, T.; González-Reza, Ricardo.M.; Zambrano-Zaragoza, M.L.; Liceaga, A.M.; Aguilar-Toalá, J.E. Plant-Based Fermented Beverages: Nutritional Composition, Sensory Properties, and Health Benefits. Foods 2024, 13, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawant, S.S.; Park, H.-Y.; Sim, E.-Y.; Kim, H.-S.; Choi, H.-S. Microbial Fermentation in Food: Impact on Functional Properties and Nutritional Enhancement—A Review of Recent Developments. Fermentation 2025, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Hui, Y.; Gao, T.; Shu, G.; Chen, H. Function and Characterization of Novel Antioxidant Peptides by Fermentation with a Wild Lactobacillus Plantarum 60. LWT 2021, 135, 110162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamar, H.; He, R.; Li, Y.; Song, M.; Deng, D.; Cui, Y.; Yu, M.; Ma, X. Metabolome and Metagenome Integration Unveiled Synthesis Pathways of Novel Antioxidant Peptides in Fermented Lignocellulosic Biomass of Palm Kernel Meal. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Zang, C.; Zheng, L.; Ding, L.; Yang, W.; Shan Ren; Guan, H. Novel Antioxidant Peptides from Fermented Whey Protein by Lactobacillus Rhamnosus B2-1: Separation and Identification by in Vitro and in Silico Approaches. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 23306–23319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehal, F.; Sahnoun, M.; Smaoui, S.; Jaouadi, B.; Bejar, S.; Mohammed, S. Characterization, High Production and Antimicrobial Activity of Exopolysaccharides from Lactococcus Lactis F-Mou. Microbial Pathogenesis 2019, 132, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouelela, M.E.; Helmy, Y.A. Next-Generation Probiotics as Novel Therapeutics for Improving Human Health: Current Trends and Future Perspectives. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.; Oh, H.; Oh, N.S.; Seo, Y.; Kang, J.; Park, M.H.; Kim, K.S.; Kang, S.H.; Yoon, Y. Anti-Inflammatory Effect of a Peptide Derived from the Synbiotics, Fermented Cudrania Tricuspidata with Lactobacillus Gasseri, on Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Mediators of Inflammation 2020, 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, N.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Oh, S.; Joung, J.Y.; Kim, S.G.; Shin, Y.K.; Lee, K.-W.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, Y. Improved Functionality of Fermented Milk Is Mediated by the Synbiotic Interaction between Cudrania Tricuspidata Leaf Extract and Lactobacillus Gasseri Strains. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2016, 100, 5919–5932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Fakhrany, O.M.; Elekhnawy, E. Next-Generation Probiotics: The Upcoming Biotherapeutics. Mol Biol Rep 2024, 51, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Hu, J.; Leng, T.; Liu, S.; Xie, M. Rosa Roxburghii-Edible Fungi Fermentation Broth Attenuates Hyperglycemia, Hyperlipidemia and Affects Gut Microbiota in Mice with Type 2 Diabetes. Food Bioscience 2023, 52, 102432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Li, Y.; Hao, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Yang, H.; Xu, S.; Li, S.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Y. Fermentation Improves Antioxidant Capacity and γ-Aminobutyric Acid Content of Ganmai Dazao Decoction by Lactic Acid Bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1274353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Miah, Md.A.S.; Islam, Md.F.; Tisa, K.J.; Bhuiyan, Md.H.R.; Bhuiyan, M.N.I.; Afrin, S.; Ahmed, K.S.; Hossain, Md.H. Fermentation with Lactic Acid Bacteria Enhances the Bioavailability of Bioactive Compounds of Whole Wheat Flour. Applied Food Research 2024, 4, 100610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Wang, J. Oxidative Stress Tolerance and Antioxidant Capacity of Lactic Acid Bacteria as Probiotic: A Systematic Review. Gut Microbes 2020, 12, 1801944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowarah, R.; Verma, A.K.; Agarwal, N.; Singh, P.; Singh, B.R. Selection and Characterization of Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria and Its Impact on Growth, Nutrient Digestibility, Health and Antioxidant Status in Weaned Piglets. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łepecka, A.; Szymański, P.; Okoń, A.; Zielińska, D. Antioxidant Activity of Environmental Lactic Acid Bacteria Strains Isolated from Organic Raw Fermented Meat Products. LWT 2023, 174, 114440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prudêncio de Souza, E.R.; Braz, M.V.D.C.; Castro, R.N.; Pereira, M.D.; Riger, C.J. Influence of Microbial Fermentation on the Antioxidant Activity of Phenolic Substances in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2023, 134, lxad148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, V.; Bose, C.; Sunilkumar, D.; Cherian, R.M.; Thomas, S.S.; Nair, B.G. Resveratrol as a Promising Nutraceutical: Implications in Gut Microbiota Modulation, Inflammatory Disorders, and Colorectal Cancer. IJMS 2024, 25, 3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duraiswamy, A.; Sneha A., N. M.; Jebakani K., S.; Selvaraj, S.; Pramitha J., L.; Selvaraj, R.; Petchiammal K., I.; Kather Sheriff, S.; Thinakaran, J.; Rathinamoorthy, S.; et al. Genetic Manipulation of Anti-Nutritional Factors in Major Crops for a Sustainable Diet in Future. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1070398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, L.; Wang, W.; Dou, Z.; Chen, J.; Meng, Y.; Cai, L.; Li, Y. Effects of Mixed Fermentation of Different Lactic Acid Bacteria and Yeast on Phytic Acid Degradation and Flavor Compounds in Sourdough. LWT 2023, 174, 114438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, Q.; Li, Z.; Shen, Z.; Tan, B.; Zhai, X. Changing the Polyphenol Composition and Enhancing the Enzyme Activity of Sorghum Grain by Solid-state Fermentation with Different Microbial Strains. J Sci Food Agric 2024, 104, 6186–6195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Q.; Dekker, S.; Kyriakopoulou, K.; Boom, R.M.; Smid, E.J.; Schutyser, M.A.I. Enhanced Nutritional Value of Chickpea Protein Concentrate by Dry Separation and Solid State Fermentation. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2020, 59, 102269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Sanwal, N.; Bareen, M.A.; Barua, S.; Sharma, N.; Joshua Olatunji, O.; Prakash Nirmal, N.; Sahu, J.K. Trends in Functional Beverages: Functional Ingredients, Processing Technologies, Stability, Health Benefits, and Consumer Perspective. Food Research International 2023, 170, 113046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.R.; Dias, G.; Ferreira, C.L.L.F.; Franceschini, S.C.C.; Costa, N.M.B. Growth of Preschool Children Was Improved When Fed an Iron-Fortified Fermented Milk Beverage Supplemented with Lactobacillus Acidophilus. Nutrition Research 2008, 28, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfek, M.A.; Baker, E.A.; El-Sayed, H.A. Study Properties of Fermented Camels’ and Goats’ Milk Beverages Fortified with Date Palm (<I>Phoenix Dactylifera L</I>.). FNS 2021, 12, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkot, W.F.; Elmahdy, A.; El-Sawah, T.H.; Alghamdia, O.A.; Alhag, S.K.; Al-Shahari, E.A.; AL-Farga, A.; Ismail, H.A. Development and Characterization of a Novel Flavored Functional Fermented Whey-Based Sports Beverage Fortified with Spirulina Platensis. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 258, 128999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmani, B.; Bodbodak, S.; Yerlikaya, O. Development of a Novel Milk-Based Product Fortified with Carrot Juice. Food Bioscience 2024, 58, 103792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, M.; Ahmed, K.A.; Ahmed, I.A.M.; Yehia, H.M.; Abdelkarim, D.O.; Alhamdan, A.; Elfeky, A. Optimization and Storage Stability of Milk–Date Beverages Fortified with Sukkari Date Powder. Processes 2024, 12, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, A.; Gatri, E.; Filannino, P.; M’Hir, S.; Ayed, L. Formulation Design and Functional Characterization of a Novel Fermented Beverage with Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory and Antibacterial Properties. Beverages 2025, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrellou, D.; Kandylis, P.; Kokkinomagoulos, E.; Hatzikamari, M.; Bekatorou, A. Emmer-Based Beverage Fortified with Fruit Juices. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Liu, J.; Cao, W.; Wang, X. Formulating a Novel Fermented Soy Milk Functional Meal Replacement among Overweight Individuals: A Preliminary Weight Loss Clinical Trial. Journal of Food Bioactives 2021, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, U.; Singh, A.; Ahmed, M.; Iqbal, U.; Saini, P. Functional and Physicochemical Characterization of a Novel Pearl Millet—Soy Milk-based Synbiotic Beverage. Food Safety and Health 2025, 3, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liu, H.; Han, J.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, J.; Liu, X. Introducing Bacillus Natto and Propionibacterium Shermanii into Soymilk Fermentation: A Promising Strategy for Quality Improvement and Bioactive Peptide Production during in Vitro Digestion. Food Chemistry 2024, 455, 139585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.; Taneja, N.K.; Singh, A.; Dhewa, T.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, A.; Chauhan, K.; Juneja, V.; Oberoi, H.S. Synergistic Fermentation of Vitamin B2 (Riboflavin) Bio-Enriched Soy Milk: Optimization and Techno-Functional Characterization of next Generation Functional Vegan Foods. Discov Food 2025, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fermented Plant-Based Alternatives Market - A Global and Regional Analysis: Focus on Applications, Products, Patent Analysis, and Country Analysis - Analysis and Forecast, 2019-2026 Available online:. Available online: https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/5359984/fermented-plant-based-alternatives-market-a (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Shahbazi, R.; Sharifzad, F.; Bagheri, R.; Alsadi, N.; Yasavoli-Sharahi, H.; Matar, C. Anti-Inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Properties of Fermented Plant Foods. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukid, F.; Hassoun, A.; Zouari, A.; Tülbek, M.; Mefleh, M.; Aït-Kaddour, A.; Castellari, M. Fermentation for Designing Innovative Plant-Based Meat and Dairy Alternatives. Foods 2023, 12, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila-Real, C.; Costa, C.; Pimenta-Martins, A.; Mbugua, S.; Hagrétou, S.-L.; Katina, K.; Maina, N.H.; Pinto, E.; Gomes, A.M.P. Novel Fermented Plant-Based Functional Beverage: Biological Potential and Impact on the Human Gut Microbiota. Foods 2025, 14, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpelin, C.; De Souza Cordes, C.L.; Kamimura, E.S.; Macedo, J.A.; De Paula Menezes Barbosa, P.; Alves Macedo, G. New Plant-Based Kefir Fermented Beverages as Potential Source of GABA. J Food Sci Technol 2025, 62, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarbati, A.; Canonico, L.; Ciani, M.; Morresi, C.; Damiani, E.; Bacchetti, T.; Comitini, F. Functional Potential of a New Plant-Based Fermented Beverage: Benefits through Non-Conventional Probiotic Yeasts and Antioxidant Properties. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2024, 424, 110857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tritean, N.; Dima, Ștefan-O. ; Trică, B.; Stoica, R.; Ghiurea, M.; Moraru, I.; Cimpean, A.; Oancea, F.; Constantinescu-Aruxandei, D. Selenium-Fortified Kombucha–Pollen Beverage by In Situ Biosynthesized Selenium Nanoparticles with High Biocompatibility and Antioxidant Activity. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanzami, K.; Lalremruati, C.; Vanlalthlana; Lalthasanga, A. ; Tungoe, P.C.; Ralte, J.L.; Lalhlenmawia, H. Changes in Biochemical and Nutritional Properties of Bekang-Um (Fermented Soybean) Prepared by Traditional Method and Customized Incubator. Sci Vis 2019, 19, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xiong, W.; Wang, Y.; Nie, Y.; Wu, Q.; Xu, Y.; Geisen, S. Temperature-Induced Annual Variation in Microbial Community Changes and Resulting Metabolome Shifts in a Controlled Fermentation System. mSystems 5, e00555–20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peñuela-Martínez, A.E.; Moreno-Riascos, S.; Medina-Rivera, R. Influence of Temperature-Controlled Fermentation on the Quality of Mild Coffee (Coffea Arabica L.) Cultivated at Different Elevations. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haile, M.; Kang, W.H. Antioxidant Properties of Fermented Green Coffee Beans with Wickerhamomyces Anomalus (Strain KNU18Y3). Fermentation 2020, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Yang, G.; Che, C.; Liu, J.; Si, M.; He, Q. Enhancing Rhamnolipid Production and Exploring the Mechanisms of Low-Foaming Fermentation under Weak-Acid Conditions 2020.

- Amaro-Reyes, A.; Marcial-Ramírez, D.; Vázquez-Landaverde, P.A.; Utrilla, J.; Escamilla-García, M.; Regalado, C.; Macias-Bobadilla, G.; Campos-Guillén, J.; Ramos-López, M.A.; Favela-Camacho, S.E. Electrostatic Fermentation: Molecular Response Insights for Tailored Beer Production. Foods 2024, 13, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagchandanii, D.D.; Babu, R.P.; Sonawane, J.M.; Khanna, N.; Pandit, S.; Jadhav, D.A.; Khilari, S.; Prasad, R. A Comprehensive Understanding of Electro-Fermentation. Fermentation 2020, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; An, F.; Lin, H.; Li, M.; Wu, J.; Wu, R. Advances in Fermented Foods Revealed by Multi-Omics: A New Direction toward Precisely Clarifying the Roles of Microorganisms. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1044820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maden, B.; Yildirim Kumral, A. Degradation Trends of Some Insecticides and Microbial Changes during Sauerkraut Fermentation under Laboratory Conditions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 14988–14995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, F.S.F.; Clermont, L.; Tung, Q.N.; Antelmann, H.; Seibold, G.M. The Industrial Organism Corynebacterium Glutamicum Requires Mycothiol as Antioxidant to Resist Against Oxidative Stress in Bioreactor Cultivations. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantzourani, I.; Nikolaou, A.; Kourkoutas, Y.; Alexopoulos, A.; Dasenaki, M.; Mastrotheodoraki, A.; Proestos, C.; Thomaidis, N.; Plessas, S. Chemical Profile Characterization of Fruit and Vegetable Juices after Fermentation with Probiotic Strains. Foods 2024, 13, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szydłowska, A.; Zielińska, D.; Sionek, B.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. The Mulberry Juice Fermented by Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum O21: The Functional Ingredient in the Formulations of Fruity Jellies Based on Different Gelling Agents. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 12780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Zhang, M.; Liu, L.; Dong, L.; Ma, Y.; Wei, Z.; Chi, J.; Zhang, R. Co-Culture Submerged Fermentation by Lactobacillus and Yeast More Effectively Improved the Profiles and Bioaccessibility of Phenolics in Extruded Brown Rice than Single-Culture Fermentation. Food Chemistry 2020, 326, 126985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Luo, D.; Xu, W.; Liu, H.; Pang, M.; Chen, G. Regulation of the Phenolic Release and Conversion in Oats (Avena Sativa L.) by Co-Microbiological Fermentation with Monascus Anka, Saccharomyces Cerevisiae and Bacillus Subtilis. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 2025, 48, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Guo, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Yang, X.; Song, L.; Ke, Y.; Yang, J.; Ma, Z. Optimization of the Fermentation Conditions for Producing Antioxidant Peptides From Yak ( Bos Grunniens ) Casein by Bacillus Cereus (XBMU-SK-01). Journal of Food Processing and Preservation 2024, 2024, 7923106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjukta, S.; Sahoo, D.; Rai, A.K. Fermentation of Black Soybean with Bacillus Spp. for the Production of Kinema: Changes in Antioxidant Potential on Fermentation and Gastrointestinal Digestion. J Food Sci Technol 2022, 59, 1353–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez-Cano, A.J.; Ramírez-Esparza, U.; Méndez-González, F.; Alvarado-González, M.; Baeza-Jiménez, R.; Sepúlveda-Torre, L.; Prado-Barragán, L.A.; Buenrostro-Figueroa, J.J. Recovery of Phenolic Compounds with Antioxidant Capacity Through Solid-State Fermentation of Pistachio Green Hull. Microorganisms 2024, 13, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, M.; Gómez-Urios, C.; Razavi, S.H.; Khodaiyan, F.; Blesa, J.; Esteve, M.J. Optimization of Solid-State Fermentation Conditions to Improve Phenolic Content in Corn Bran, Followed by Extraction of Bioactive Compounds Using Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2024, 93, 103621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuellar Alvarez, L.; Cuellar Alvarez, N.; Galeano Garcia, P.; Suárez Salazar, J.C. Effect of Fermentation Time on Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Potential in Cupuassu (Theobroma Grandiflorum (Willd. Ex Spreng.) K.Schum.) Beans. Acta Agron. 2017, 66, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punia, S.; Sandhu, K.S.; Grasso, S.; Purewal, S.S.; Kaur, M.; Siroha, A.K.; Kumar, K.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, M. Aspergillus Oryzae Fermented Rice Bran: A Byproduct with Enhanced Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Potential. Foods 2020, 10, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.; Li, Z.; Fan, G.; Xie, C. Enhancing the Nutritional Value and Antioxidant Properties of Foxtail Millet by Solid-state Fermentation with Edible Fungi. Food Science & Nutrition 2024, 12, 6660–6672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalissavrina, I.; Murdiati, A.; Raharjo, S.; Lestari, L.A. The Effects of Duration of Fermentation on Total Phenolic Content, Antioxidant Activity, and Isoflavones of The Germinated Jack Bean Tempeh (Canavalia Ensiformis). Indonesian J Pharm 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Tang, L.; Lu, Y. Dissolved Oxygen Control Strategy for Improvement of TL1-1 Production in Submerged Fermentation by Daldinia Eschscholzii. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2017, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.-Z.; Xu, W.-C.; Chen, W.-J.; Wu, S.; Huang, Y.-Y. Metabolite and Microbiome Profilings of Pickled Tea Elucidate the Role of Anaerobic Fermentation in Promoting High Levels of Gallic Acid Accumulation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 13751–13759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anupama, M. P. Anupama, M. P. (2024). Bioreactors - a critical review on construction, considerations and applications (pp. 50–76). [CrossRef]

- Yay, C.; Cinar, Z.O.; Donmez, S.; Tumer, T.B.; Guneser, O.; Hosoglu, M.I. Optimizing Bioreactor Conditions for Spirulina Fermentation by Lactobacillus Helveticus and Kluyveromyces Marxianus: Impact on Chemical & Bioactive Properties. Bioresource Technology 2024, 403, 130832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhanja, T.; Rout, S.; Banerjee, R.; Bhattacharyya, B.C. Studies on the Performance of a New Bioreactor for Improving Antioxidant Potential of Rice. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2008, 41, 1459–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.M.; Matos, I.L.O.; Cordeiro, F.M.M.; Silva, A.C.M.D.; Cavalcanti, E.B.; Lima, Á.S. Enhanced Oxygen Mass Transfer in Mixing Bioreactor Using Silica Microparticles. Fermentation 2024, 10, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, L.J.; Vorländer, D.; Ostsieker, H.; Rasch, D.; Lohse, J.-L.; Breitfeld, M.; Grosch, J.-H.; Wehinger, G.D.; Bahnemann, J.; Krull, R. 3D-Printed Micro Bubble Column Reactor with Integrated Microsensors for Biotechnological Applications: From Design to Evaluation. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 7276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lung, M.Y.; Chang, Y.C. In Vitro Antioxidant Properties of Polysaccharides from Armillaria Mellea in Batch Fermentation. African Journal of Biotechnology 2011, 10, 7048–7057. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, D.; Salgado, J.M.; Cambra-López, M.; Dias, A.; Belo, I. Biotechnological Valorization of Oilseed Cakes: Substrate Optimization by Simplex Centroid Mixture Design and Scale-up to Tray Bioreactor. Biofuels Bioprod Bioref 2023, 17, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Luo, C.-Y.; Yao, X.-Z.; Jiao, Y.-J.; Lu, L.-T. Optimization of the Theabrownins Process by Liquid Fermentation of Aspergillus Niger and Their Antioxidant Activity. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 9720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Niu, M.; Song, D.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Li, S.; Lu, B. Evaluation of Biochemical and Antioxidant Dynamics during the Co-fermentation of Dehusked Barley with Rhizopus Oryzae and Lactobacillus Plantarum. J Food Biochem 2020, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Ma, Y.; An, F.; Yu, M.; Zhang, L.; Tao, X.; Pan, G.; Liu, Q.; Wu, J.; Wu, R. Ultrasound-Assisted Fermentation for Antioxidant Peptides Preparation from Okara: Optimization, Stability, and Functional Analyses. Food Chemistry 2024, 439, 138078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, N.; Zhao, L.; Wu, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, F. Process Optimization for Production of Ferulic Acid and Pentosans from Wheat Brans by Solid-State Fermentation and Evaluation of Their Antioxidant Activities. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 2, 1114–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd. Razak, D.L.; Abd. Rashid, N.Y.; Jamaluddin, A.; Abd Ghani, A.; Abdul Manan, M. Antioxidant Activities, Tyrosinase Inhibition Activity and Bioactive Compounds Content of Broken Rice Fermented with Amylomyces Rouxii. Food Res. 2021, 5, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhou, B.; Shi, J.; Xu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, N.; Li, P.; Jiang, L. Research on the Development and Biological Activity of an Antioxidant Compound Fruit and Vegetable Ferment.; Jinan City, China, 2020; p. 020009.

- Mendes, A.R.; Spínola, M.P.; Lordelo, M.; Prates, J.A.M. Advances in Bioprocess Engineering for Optimising Chlorella Vulgaris Fermentation: Biotechnological Innovations and Applications. Foods 2024, 13, 4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohlscheidt, M.; Charaniya, S.; Bork, C.; Jenzsch, M.; Noetzel, T.L.; Luebbert, A. Bioprocess and Fermentation Monitoring. In Encyclopedia of Industrial Biotechnology; Wiley, 2013; pp. 1469–1491 ISBN 9780471799306.

- Roberts, J.; Power, A.; Chapman, J.; Chandra, S.; Cozzolino, D. The Use of UV-Vis Spectroscopy in Bioprocess and Fermentation Monitoring. Fermentation 2018, 4, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandenius, C.-F. Recent Developments in the Monitoring, Modeling and Control of Biological Production Systems. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 2004, 26, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikita, S.; Mishra, S.; Gupta, K.; Runkana, V.; Gomes, J.; Rathore, A.S. Advances in Bioreactor Control for Production of Biotherapeutic Products. Biotech & Bioengineering 2023, 120, 1189–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larios-Cruz, R.; Buenrostro-Figueroa, J.; Prado-Barragán, A.; Rodríguez-Jasso, R.M.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R.; Montañez, J.C.; Aguilar, C.N. Valorization of Grapefruit By-Products as Solid Support for Solid-State Fermentation to Produce Antioxidant Bioactive Extracts. Waste Biomass Valor 2019, 10, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiharto, S.; Widiastuti, E.; Yudiarti, T.; Wahyuni, H.I.; Sartono, T.A. Improving the Nutritional Values of Cassava Pulp Through Supplementation of Selected Leaves Meal and Fermentation with Chrysonilia Crassa. JAP 2021, 23, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousif, E.-S.; Yaseen, A.; Abdel-Fatah, A.-F.; Shouk, A.-H.; Gdallah, M.; Mohammad, A. Antioxidant and Cytotoxic Properties of Nano and Fermented-Nano Powders of Wheat and Rice by-Products 2022.

- Navajas-Porras, B.; Delgado-Osorio, A.; Hinojosa-Nogueira, D.; Pastoriza, S.; Del Carmen Almécija-Rodríguez, M.; Rufián-Henares, J.Á.; Fernandez-Bayo, J.D. Improved Nutritional and Antioxidant Properties of Black Soldier Fly Larvae Reared on Spent Coffee Grounds and Blood Meal By-Products. Food Research International 2024, 196, 115151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinina, I.; Fatkullin, R.; Naumenko, N.; Popova, N.; Stepanova, D. Using Spent Brewer’s Yeast to Encapsulate and Enhance the Bioavailability of Sonochemically Nanostructured Curcumin. International Journal of Food Science 2024, 2024, 7593352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bas-Bellver, C.; Barrera, C.; Betoret, N.; Seguí, L. Impact of Fermentation Pretreatment on Drying Behaviour and Antioxidant Attributes of Broccoli Waste Powdered Ingredients. Foods 2023, 12, 3526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T. , Yin, X., Cai, M., Zhu, R., Huang, H., Liao, S., Qu, C., Dong, X.-X., Zhou, Y.-H., & Ni, J. Varieties systematization and standards status analysis of fermented Chinese medicine 2023, 48, 2699–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravyts, F.; Vuyst, L.D.; Leroy, F. Bacterial Diversity and Functionalities in Food Fermentations. Engineering in Life Sciences 2012, 12, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, E.M.C.; Aguiar, N.F.B.; Voss, G.B.; Pintado, M.E. Properties of Fermented Beverages from Food Wastes/By-Products. Beverages 2023, 9, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashaolu, T.J.; Khalifa, I.; Mesak, M.A.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Farag, M.A. A Comprehensive Review of the Role of Microorganisms on Texture Change, Flavor and Biogenic Amines Formation in Fermented Meat with Their Action Mechanisms and Safety. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2023, 63, 3538–3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IZAH, S. C., T KIGIGHA, L., & OKOWA, I. P. (2016). Microbial quality assessment of fermented maize Ogi (a cereal product) and options for overcoming constraints in production. Biotechnological Research, 2(2), 81-93. Retrieved from http://br.biomedpress.org/index.php/br/article/view/718.

- Dikhanbayeva, F.T.; Uzakov, Y.M.; Dauletbakov, B.D.; Smailova, Zh.Zh.; Kuzembayeva, G.К.; Bazylkhanova, E.Ch. Mathematical Modeling of Quality Parameters of Fermented Milk Products. jour 2024, 146, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, K.Y.; Kho, C.; Ong, Y.Y.; Thoo, Y.Y.; Lim, R.L.H.; Tan, C.P.; Ho, C.W. Studies on the Storage Stability of Fermented Red Dragon Fruit (Hylocereus Polyrhizus) Drink. Food Sci Biotechnol 2018, 27, 1411–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, H.-L.; Yang, T.-C.; Chou, C.-C. Effects of Storage Conditions on the Stability of Isoflavone Isomers in Lactic Fermented Soymilk Powder. Food Bioprocess Technol 2013, 6, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Gao, P.; Xu, Y.; Xia, W.; Hua, Q.; Jiang, Q. Effect of Storage Conditions on Microbiological Characteristics, Biogenic Amines, and Physicochemical Quality of Low-Salt Fermented Fish. Journal of Food Protection 2020, 83, 1057–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, N.; Seifan, M.; Berenjian, A. Fermentation of Menaquinone-7: The Influence of Environmental Factors and Storage Conditions on the Isomer Profile. Processes 2023, 11, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhao, F.; Liu, H.; Li, R.; Wang, Y.; Liao, X. Fermented Minced Pepper by High Pressure Processing, High Pressure Processing with Mild Temperature and Thermal Pasteurization. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2016, 36, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-H.; Moon, S.-Y.; Cho, B.-Y.; Choi, S.-I.; Jung, T.-D.; Choi, S.-H.; Kim, J.-D.; Lee, O.-H. Stability of Ethanolic Extract from Fermented Cirsium Setidens Nakai by Bioconversion during Different Storing Conditions. The Korean Journal of Food And Nutrition 2017, 30, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouaabou, R.; Hssaini, L.; Ennahli, S.; Alahyane, A. Evaluating the Impact of Storage Time and Temperature on the Stability of Bioactive Compounds and Microbial Quality in Cherry Syrup from the ‘Burlat’ Cultivar. Discov Food 2024, 4, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, T.-T.; Guo, R.-R.; Ye, Q.; Zhao, H.-L.; Huang, X.-H. The Regulation of Key Flavor of Traditional Fermented Food by Microbial Metabolism: A Review. Food Chemistry: X 2023, 19, 100871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowron, K.; Budzyńska, A.; Grudlewska-Buda, K.; Wiktorczyk-Kapischke, N.; Andrzejewska, M.; Wałecka-Zacharska, E.; Gospodarek-Komkowska, E. Two Faces of Fermented Foods—The Benefits and Threats of Its Consumption. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 845166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Qin, C.; Wen, M.; Zhang, L.; Wang, W. The Effects of Food Nutrients and Bioactive Compounds on the Gut Microbiota: A Comprehensive Review. Foods 2024, 13, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, S.; Sha, S.P.; Ghatani, K. Metabolomics of Ethnic Fermented Foods and Beverages: Understanding New Aspects through Omic Techniques. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1040567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgaz, C.; Sánchez-Ruiz, A.; Colmenarejo, G. Identifying and Filling the Chemobiological Gaps of Gut Microbial Metabolites. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 6778–6798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padhi, S.; Sarkar, P.; Sahoo, D.; Rai, A.K. Potential of Fermented Foods and Their Metabolites in Improving Gut Microbiota Function and Lowering Gastrointestinal Inflammation. J Sci Food Agric 2024, jsfa.13313. [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Valencia, R.; Santiago-López, L.; Mojica, L.; Hernández-Mendoza, A.; Vallejo-Cordoba, B.; Sáyago-Ayerdi, S.G.; Beltrán-Barrientos, L.M.; González-Córdova, A.F. Effect of Fermented Foods on Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Focus on the MAPK and NF-Kβ Pathways. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 5, 398–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngamsamer, C.; Muangnoi, C.; Tongkhao, K.; Sae-Tan, S.; Treesuwan, K.; Sirivarasai, J. Potential Health Benefits of Fermented Vegetables with Additions of Lacticaseibacillus Rhamnosus GG and Polyphenol Vitexin Based on Their Antioxidant Properties and Prohealth Profiles. Foods 2024, 13, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, E.; Balasubramanian, R.; Ferri, A.; Cotter, P.D.; Clarke, G.; Cryan, J.F. Fibre & Fermented Foods: Differential Effects on the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Van Beeck, W.; Hanlon, M.; DiCaprio, E.; Marco, M.L. Lacto-Fermented Fruits and Vegetables: Bioactive Components and Effects on Human Health. Annual Review of Food Science and Technology 2025, 16, 289–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubeyitogullari, A.; Ahmadzadeh, S.; Kandhola, G.; Kim, J. Polysaccharide-based Porous Biopolymers for Enhanced Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability of Bioactive Food Compounds: Challenges, Advances, and Opportunities. Comp Rev Food Sci Food Safe 2022, 21, 4610–4639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chourasia, R.; Chiring Phukon, L.; Abedin, M.M.; Padhi, S.; Singh, S.P.; Rai, A.K. Bioactive Peptides in Fermented Foods and Their Application: A Critical Review. Syst Microbiol and Biomanuf 2023, 3, 88–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rein, M.J.; Renouf, M.; Cruz-Hernandez, C.; Actis-Goretta, L.; Thakkar, S.K.; Da Silva Pinto, M. Bioavailability of Bioactive Food Compounds: A Challenging Journey to Bioefficacy. Brit J Clinical Pharma 2013, 75, 588–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laya, A.; Wangso, H.; Fernandes, I.; Djakba, R.; Oliveira, J.; Carvalho, E. Bioactive Ingredients in Traditional Fermented Food Condiments: Emerging Products for Prevention and Treatment of Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. Journal of Food Quality 2023, 2023, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harahap, I.A.; Suliburska, J.; Karaca, A.C.; Capanoglu, E.; Esatbeyoglu, T. Fermented Soy Products: A Review of Bioactives for Health from Fermentation to Functionality. Comp Rev Food Sci Food Safe 2025, 24, e70080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, A.; Gómez-Sala, B.; O’Connor, E.M.; Kenny, J.G.; Cotter, P.D. Global Regulatory Frameworks for Fermented Foods: A Review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 902642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chieffi, D.; Fanelli, F.; Fusco, V. Legislation of Probiotic Foods and Supplements. In Probiotics for Human Nutrition in Health and Disease; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 25–44 ISBN 9780323899086.

- Ovesen, L. Regulatory Aspects of Functional Foods: European Journal of Cancer Prevention 1997, 6, 480–482. [CrossRef]

- Craddock, N. Mapping Out the Regulatory Landscape for Functional Foods Across Europe. Journal of Nutraceuticals, Functional & Medical Foods 2000, 2, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugh, P.; Misra, S.; Dhar, M.S.; Raghuwanshi, S. Regulatory Aspects Relevant to Probiotic Products. In Probiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics, and Postbiotics; Kothari, V., Kumar, P., Ray, S., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; ISBN 9789819914623. [Google Scholar]

- Feord, J. Lactic acid bacteria in a changing legislative environment. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek International Journal of General and Molecular Microbiology, 2002, 82, 353–360. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, P. (2015). Regulation of functional foods in China: A framework in flux.

- Csar, P.; Henriques Do Amaral, M.D.P.; Pereira, L.; Santana Pereira, M.C.; Oliveira Pinto, M.A.D. Public Health Policies and Functional Property Claims for Food in Brazil. In Structure and Function of Food Engineering; Amer Eissa, A., Ed.; InTech, 2012 ISBN 9789535106951.

- Dinker, N.; Gangwar, S.; Shrivastava, S. FSSAI: Standards, Rules and Regulations, Non-Compliances and Action Taken. IJCA 2023, 185, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wto | the wto and the fao/who codex alimentarius. Retrieved March 13, 2025, from https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/coher_e/wto_codex_e.htm#:~:text=The%20Codex%20Alimentarius%20is%20a,to%20reduce%20hunger%20and%20poverty.

- Bech-Larsen, T.; Scholderer, J. Functional Foods in Europe: Consumer Research, Market Experiences and Regulatory Aspects. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2007, 18, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, M.L.; Sanders, M.E.; Gänzle, M.; Arrieta, M.C.; Cotter, P.D.; De Vuyst, L.; Hill, C.; Holzapfel, W.; Lebeer, S.; Merenstein, D.; et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) Consensus Statement on Fermented Foods. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 18, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, V. V., & Kerkar, S. (2024). Fermentation assisted functional foods. Iterative International Publishers, Selfypage Developers Pvt Ltd., 2024; pp. 11–32 ISBN 9789362521804. [CrossRef]

- Maurya, N.K. Regulating Innovation: A Review of Product Development and Regulatory Frameworks in the Food Industry. JNFP 2024, 07, 01–08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, J.; Ndang, K.; Chethana, M.B.; Chinmayi, C.S.; Afrana, K.; Gopan, G.; Parambi, D.G.T.; Munjal, K.; Chopra, H.; Dhyani, A.; et al. Opportunities and Regulatory Challenges of Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals During COVID-19 Pandemic. CNF 2024, 20, 1252–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira Araujo Magalhães, C.; Brandão Mafra De Carvalho, G.; Ailton Conceição Bispo, J. ECONOMIC FEASIBILITY STUDY FOR THE IMPLEMENTATION OF A MICRO-INDUSTRY PRODUCING KOMBUCHA FLAVORED WITH PASSION FRUIT FROM THE CAATINGA. RET 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeeranan Wongwatanyoo; Piyachat Thongpaeng; Janjira Chatmontri An Analysis of the Cost Structure and Cost-Effective Investment in the Production of Low-Sodium Fermented Fish with Traditional Flavors from Isaan Local Wisdom. NANO-NTP 2024, 1286–1296. [CrossRef]

- Devi, A.N.; Devi, L.G.; Devi, C.B. Traditional Soybean Fermentation of Meitei of Manipur. Int. J. Agric. Extension Social Dev. 2024, 7, 674–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lys, I.M. The Role of Lactic Fermentation in Ensuring the Safety and Extending the Shelf Life of African Indigenous Vegetables and Its Economic Potential. Applied Research 2025, 4, e202400131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Qu, G.; Wang, D.; Chen, J.; Du, G.; Fang, F. Synergistic Fermentation with Functional Microorganisms Improves Safety and Quality of Traditional Chinese Fermented Foods. Foods 2023, 12, 2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rämö, S.; Kahala, M.; Joutsjoki, V. Aflatoxin B1 Binding by Lactic Acid Bacteria in Protein-Rich Plant Material Fermentation. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 12769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Millán, J.Á.; Aguayo, E. Fermentation for Revalorisation of Fruit and Vegetable By-Products: A Sustainable Approach Towards Minimising Food Loss and Waste. Foods 2024, 13, 3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fruit/Vegetable Source | By-Product utilized | Microorganism employed | Fermentation Product | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Granadilla | Seed | Aspergillus niger | Ingredient for food, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical industries | ↑Total phenolic ↑Total flavonoids ↑Antioxidant capacity |

[52] |

| Black grape | Pomace | Yeast | Shalgam juice | ↑Tannins ↑Total polyphenolic content |

[53] |

| Apple | Apple peel | Aspergillus oryzae | Food ingredient | ↑Polyphenolic content and antioxidant capacity ↑Prebiotic potential | [54] |

| Orange | Peel | Yeast | Enriched beer | ↑Colour ↑Alcohol ↑Total polyphenolic content, antioxidant capacity, Good acceptability |

[55] |

| Acerola, guava | By-products | L. casei L-26, L. fermentum56, L. paracasei106, L. plantarum53 | Food ingredients | ↑Total flavonoids, polyphenols, antioxidant | [56,57] |

| Grape | Pomace | Kombucha consortia inoculum | Kombucha | ↑Anti-inflammatory activities ↑Anti-diabetic activities ↑Total phenolics and anthocyanins |

[58] |

| Coffee | Coffee husk | Brettanomyces bruxellensis, Saccharomycescerevisiae, Komagataeibacter pomaceri, and Komagataeibacter rhaeticus | Enriched kombucha | ↑Total polyphenolic content, flavonoids, antioxidant capacity | [59] |

| Brassica species B. oleraceavar. sabelica× B. oleracea var.Gemmifera Brassica oleracea var.capitata | Leaves | symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast (SCOBY) | Kombucha | ↑Total phenolics ↑Antioxidant capacity | [60] |

| Carrot | Pomace | Lactobacillus acidophilus LA-5, Lactobacillus casei 431, and Lactobacillus plantarum Harvest-LB1 | Food ingredient | ↑Phenolic acid content ↑Anthocyanin content ↑α-carotene |

[61] |

| Pepper | Leaves | Lactobacillus homohiochii JBCC25 and JBCC46, Saccharomyces cerevisiae ATCC18824, Actobacter aceti KACC1978 | Vinegar | ↑Anti-diabetic potential ↑Antioxidant activity ↑Total phenolics |

[62] |

| Broccoli | Leaves | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum | Lactofermented beverage | ↑Total phenolics ↑Isothiocyanates ↑Indoles ↑Antioxidant capacity ↑Anti-diabetic potential |

[63] |

| Artichoke | Leaves, stems, and outer bracts | Lactobacillus casei ATTC3931; L. plantarum ATTC8014; L. casei subs. Rhamnosus ATCC7469; L. fermentum ATCC9338 | Food additives (antimicrobial and antiviral constituents) | ↑Flavonoid content ↑Antimicrobial and antiviral effect | [64] |

| Bioreactor Design/Fermentation process | Substrate/Process | Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cascade Mode Bioreactor | Spirulina fermentation | Enhanced protein hydrolysis and antioxidant activity | [131] |

| Novel Bioreactor for SSF | Rice koji | Increased phenolics and DPPH scavenging activity | [132] |

| Stirred Tank Bioreactor | Armillaria mellea polysaccharides | High antioxidant activity with low EC50 values | [135] |

| Silica Microparticles | Rice fermentation | Improved oxygen transfer and bioreactor performance | [133] |

| 3D-Printed Micro Bubble Column | Saccharomyces cerevisiae cultivation | High oxygen transfer rates and real-time monitoring of process parameters | [134] |

| Solid-State Fermentation | Oilseed cakes | Increased lignocellulolytic enzymes and antioxidants | [136] |

| Liquid Fermentation | Theabrownins production | Higher total phenolic content and antioxidant activity | [137] |

| Co-Fermentation | Dehusked barley | Enhanced antioxidant dynamics and radical scavenging activities | [138] |

| Ultrasound-Assisted Fermentation | Okara peptides | Increased peptide content and DPPH scavenging rate | [139] |

| Solid-State Fermentation | Wheat bran | Increased ferulic acid and pentosans with improved antioxidant activity | [140] |

| Co-Fermentation | Broken rice | Significant increase in total phenolic content and antioxidant activity | [141] |

| Fruit and Vegetable Ferment | Compound fruits and vegetables | Increased polyphenols, flavonoids, and proanthocyanidins | [142] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).