1. Problem Statement

Since the early 1980’s when American astronomer Vera Rubin [

1] first published a number of accurate line of sight velocity measurements taken from edge-on spiral galaxies, it has been known that the observed velocity curves correlate poorly with predictions based on Kepler’s laws of orbital dynamics. This became known as the galaxy rotation curve anomaly. Rotation curves have now been obtained from a large number of spiral galaxies using a technique called Doppler Spectroscopy [

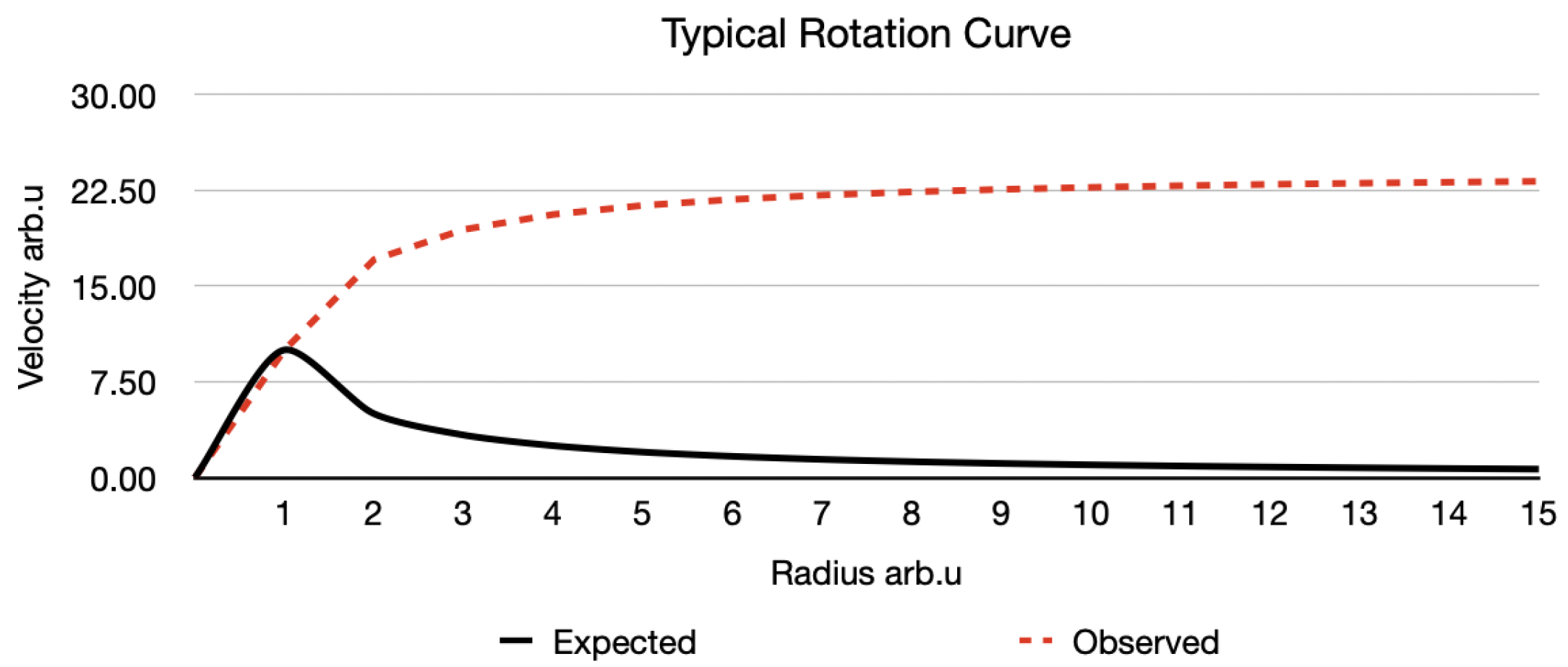

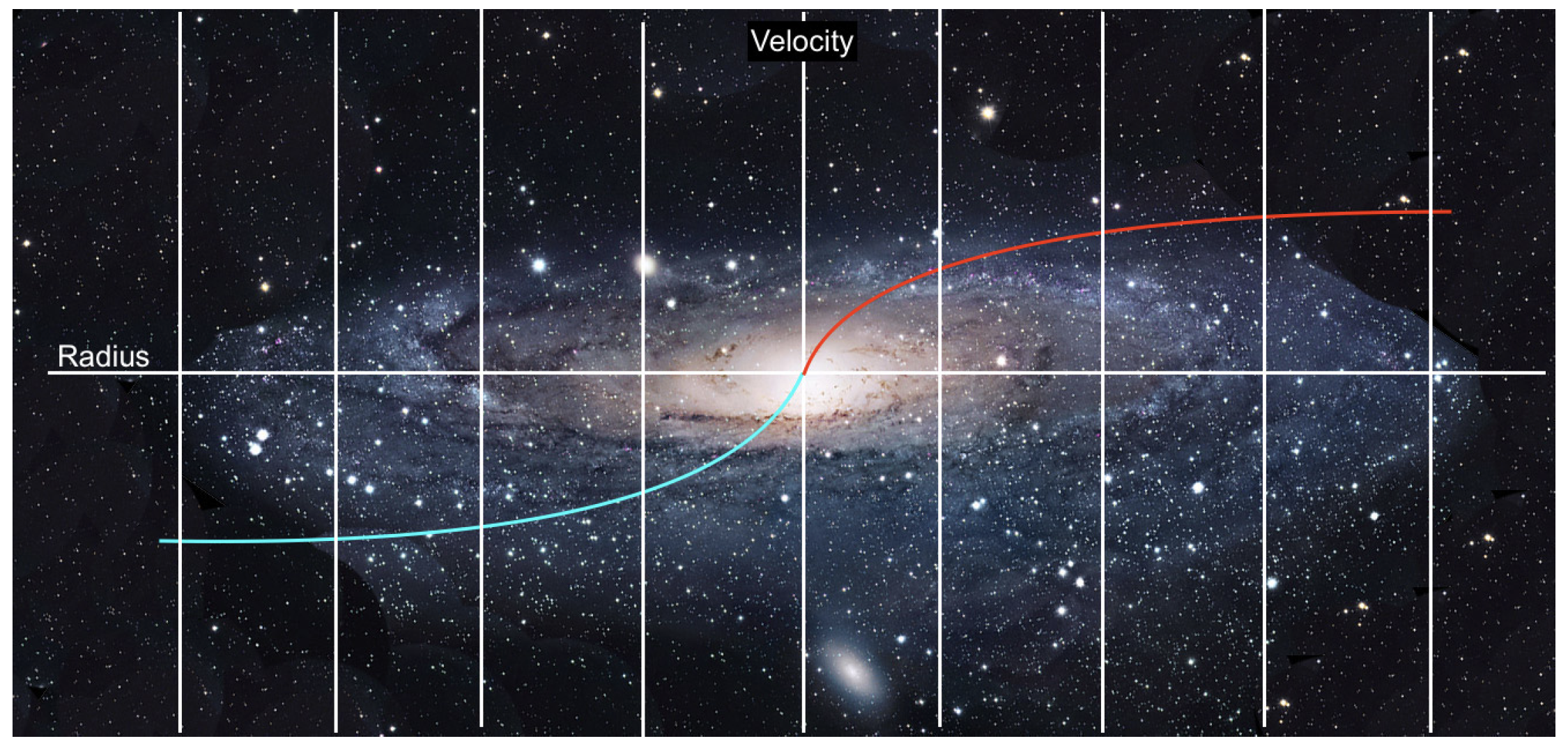

5]. Doppler spectroscopy is a line of sight method and when this is converted to circular motion and plotted as a function of the radius, the typical galaxy rotation curve shows an initial sharp rise in velocity close to the rotational centre of the galaxy, which gradually flattens out as shown in approximation

Figure 1 dashed line plot.

Such flat rotation curves are contrary to what is expected from a galaxy where most of the luminous mass is concentrated near the galactic centre. According to Kepler’s laws of orbital motion [

3] the tangential velocity ought to rise almost linearly inside the central distribution of mass (this is assumed), and once outside the central distribution of mass the radial velocity ought to observe the

rule or Kepler’s law of orbital motion around a central mass (Equation (

1)) and consequently look something like the solid line plot in (

Figure 1).

Rotation curves have been obtained from numerous galaxies and a notable discrepancy between what is expected and what is observed has been found. This problem persists even after accounting for the luminous mass distribution of the different galaxies.

Non-baryonic Dark Matter [

10] is currently the most popular hypothesis proposed to explain the problem. Additional dark matter in the galaxy would have the effect of increasing the angular velocity. The dark matter hypothesis originated in the 1930’s when Fritz Zwicky [

10] first proposed it after applying the Virial Theorem to the motion of galaxies in the coma cluster. Later in the 1980’s Zwicky’s Dark Matter hypothesis was proposed as a solution to the galaxy rotation curve problem.

To this day, only indirect evidence for dark matter has been found. Despite this, billions of dollars have been spent on major experimental efforts to detect dark matter directly, including the Large Underground Xenon (LUX) experiment [

14], XENON1T [

15], LZ [

16], PandaX [

17], and the Super Cryogenic Dark Matter Search (SuperCDMS) [

18]. None have yet confirmed its existence.

Another contending theory is Modified Newtonian Dynamics or MOND by M. Milgrom [

2] , MOND basically suggests modifying the laws of physics to a best-fit model, but many do not not consider this an elegant solution. The anomalous galaxy rotation curves remain an astronomical problem to this day, so without further comment on other theories, a new pragmatic explanation is proposed.

2. Historical Background (Doppler vs Kepler)

Let us review how orbital motion was measured and recorded, both in the past and in the present.

One of the pioneers of modern astronomy, the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe [

4], spent much of the 16th century meticulously measuring and recording planetary motions. Brahe subscribed to a geo-heliocentric model in which the Sun orbited Earth, while the other planets orbited the Sun (

Figure 2). To support this theory, he made precise measurements of planetary positions over many years. Despite using relatively primitive instruments — essentially large sextants — Brahe’s data remained unrivaled for centuries.

By considering the celestial sphere as fixed and making observations at the same time each night, Tycho Brahe effectively stopped the Earth’s rotation.

Brahe’s precise records laid the foundation for Johannes Kepler’s [

3] later works, who in around 1609 formulated a theory of orbital mechanics. Based upon Kepler’s work, Sir Isaac Newton [

8] published his

Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica in 1687, establishing what we today refer to as classical mechanics and cementing the concept of orbital motion as inherently positive.

Now almost 300 years later we have a much better understanding of the Universe and know that galaxies are many orders of magnitude larger than the solar system explored by Kepler, however they are still expected to obey the same physical laws. Unfortunately, the vast distances and orbital periods, often hundreds of millions of light-years, make it impractical to use Tycho Brahe’s method to measure orbital velocity. Instead, astronomers developed new techniques for measuring

line-of-sight velocity called

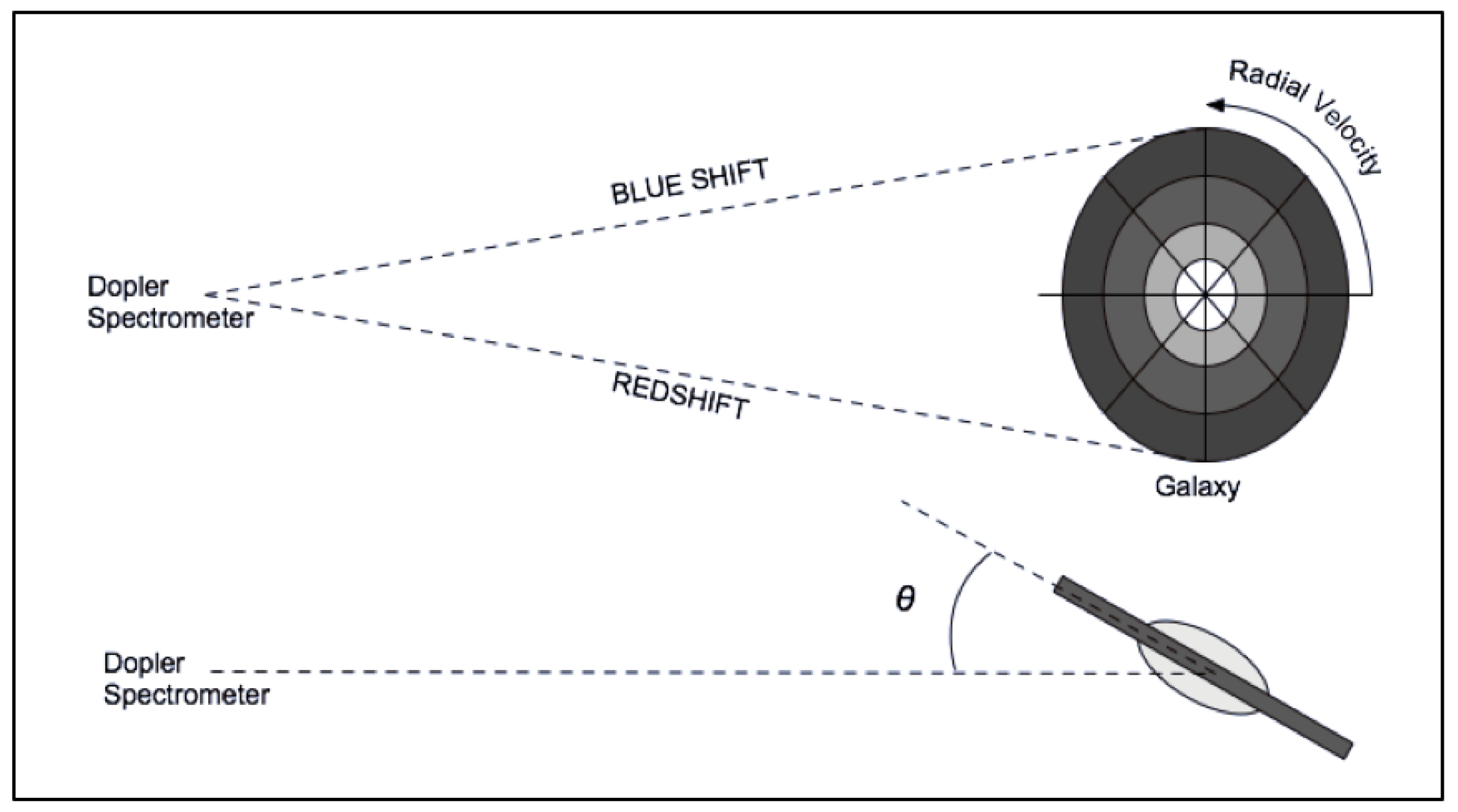

Doppler spectroscopy [

5]. By observing galaxies whose orbital planes are inclined relative to the line of sight, astronomers now measure the line of sight velocity of stars along the radial axis. (see

Figure 3).

In suitably aligned galaxies, where the edge of the disk lies along the observer’s line of sight, astronomers measure stellar velocity at various radii on both sides of the galactic disk [

6]. Spectral lines from light sources moving away from an observer will be shifted towards the red and when moving towards the observer the lines are shifted towards the blue, commonly referred to as

redshift or

blueshift.

The observed spectroscopy velocities are then corrected for the angle of inclination (Equation (

2)):

Here, and represent the measured line-of-sight velocities from blueshifted and redshifted components respectively, and is the angle of inclination between the galaxy plane and the observer.

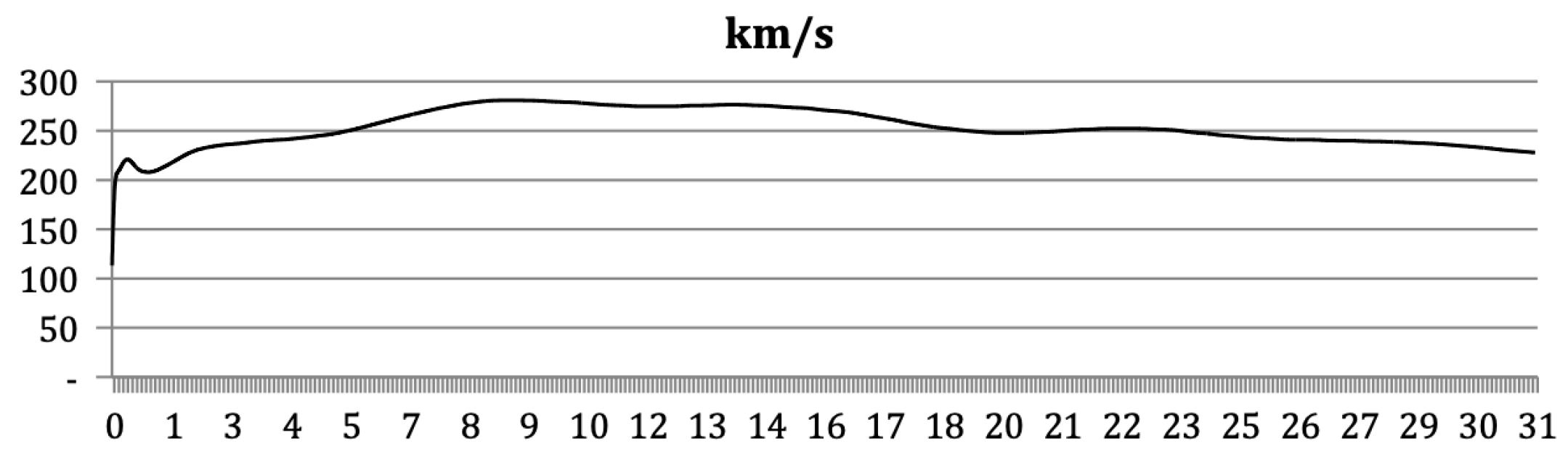

These radial velocities [

6], measured across various radii, allow astronomers to construct rotation curves, such as the example from galaxy NGC-224 (

Figure 4). The rotation curve data was retrieved from the University of Tokyo rotation curve database [

9].

In principle, Doppler spectroscopy is a straightforward and accurate method. It directly measures the change in velocity along the line of sight over time.

In essence, the problem is that the observed orbital velocity measured by doppler spectroscopy significantly exceeds what one would expect, based on the luminous mass observed by optical telescopes.

3. Solving The Problem

3.1. Fiducial Reference Frames

To understand the radial motion of celestial bodies, it is helpful to classify movement into two directions and one state of rest. Radial motion is effectively binary:

- (a)

Motion toward the observer

- (b)

At rest with respect to the observer

- (c)

Motion away from the observer (toward infinity)

A velocity vector defined relative to a fiducial reference point, can be described as positive, negative or zero. The chosen convention is arbitrary, but must remain consistent once adopted. Change of reference frame necessitates re-evaluating the direction and sign of all vectors.

Conventionally Keplerian orbital motion has been a positive velocity vector, so for consistency, we follow that convention in this paper.

| Note: The concept of speed refers to motion without regard to direction. For example, a wheel rotating on a shaft is assigned a positive angular speed, regardless of whether it spins clockwise or counter-clockwise. In contrast, velocity is directional. In astronomy, it is crucial to distinguish the two when interpreting line-of-sight motion. |

When dealing with orbital motion, there are no rigid mechanical constraints—bodies move freely along equipotential (geodesic) paths. Their velocities are governed by the potential difference between the observer and the orbiting body. Given the expanding Universe, with space itself stretching between objects, it is more accurate to speak of bodies as having velocity rather than speed with respect to the observer.

4. Direction of Motion

Doppler spectroscopy, as described, measures the line-of-sight velocity between the instrument and a moving light source—in this case, stars. (

Figure 5) shows a typical galaxy with a symbolic rotation curve overlay, blue line representing the velocity of stars moving towards the instrument and red line indicating the velocity of stars moving away from the instrument.

Velocities obtained by Doppler are instrument-referenced; the instrument serves as the fiducial or fixed reference point for the measurement.

Kepler, on the other hand, based his laws on observations by Tycho Brahe, where the situation is more complex.

With his laboratory situated on a rotating platform (Earth), Brahe’s best strategy was to time his observations precisely according to a 24-hour period. In doing so, he effectively froze Earth’s rotation relative to the celestial sphere.

This method had the unintended consequence of switching the fixed fiducial from Earth to

a distant inertial frame, and simultaneously switching the apparent direction of motion. A similar phenomenon can be seen today when a spoked wheel appears to rotate backwards under certain lighting conditions — known as the

stroboscopic effect [

12].

While unintentional, Brahe’s method may have been the earliest astronomical use of a principle analogous to the stroboscopic effect.

He meticulously plotted the positions of planets thereby producing a map of perceived motion - motion as seen from infinity, not line of sight , Brahe arbitrarily gave the planetary motions a positive velocity.

Based on Brahe’s measurements, Kepler formulated the standard expression for orbital velocity, which everyone is familiar with. (Equation (

3)).

It should now be clear why Kepler’s laws of orbital motion are incompatible with measurements made via Doppler spectroscopy: the two methods reference different fixed frames. Recognizing this discrepancy is essential for reconciling observations.

We also know that space is constantly expanding. Astronomer Edwin Hubble measured the velocities and distances of many galaxies [

13] finding a roughly linear relationship between recessional velocity and distance — now known as

Hubble’s Law, with a constant of approximately 70 km/s per megaparsec.

Hubble’s constant introduces a velocity offset that depends on the chosen frame of reference. While this offset is negligible in the context of galaxy rotation, it must nonetheless be accounted for when interpreting Doppler measurements.

Kepler and Newton defined orbital velocity relative to the fixed background stars and treated it as positive. Doppler spectroscopy, on the other hand, references the local instrument. To reconcile these systems, any observed Doppler velocity must be factored by to match the Keplerian frame.

In summary, it appears that galaxy rotation curves may have been plotted with a reversed sign convention, values that should have been plotted in the bottom right quadrant were plotted in the top right quadrant and vice versa on the left.

As a consequence, we can say that traditional astronomers effectively measured velocities from inside the gravitational system (relative to the fixed background stars), while modern Doppler spectroscopy measures velocities from outside the system (relative to the instrument). Thus, modern measurements capture what we may term an inverse velocity.

4.1. Orbital v Escape Velocity

Escape velocity is particularly interesting because it is one of the few equations that remains valid under both Newtonian and relativistic frameworks. It represents the radial outward velocity required to reach infinity without further energy input. The classical and relativistic forms is given by: (Equation (

4)):

Notably, escape velocity is only

larger than Kepler’s orbital velocity (Equation (

3)). This ratio can be illustrated geometrically.

For an observer inside the orbit, a body in a stable circular orbit requires both radial and tangential influences. While the radial component is technically accelleration, we may treat both components conceptually as unit vectors. According to the Pythagorean theorem their combined influence becomes , which elegantly explains the difference between orbital and escape velocities.

To an observer located outside the orbit (i.e., at infinity), these radial and tangential vectors will appear collinear and aligned radially with respect to the observer. Therefore the instant velocity

as observed by Doppler is not keplerian orbital velocity, but rather the full escape velocity, which according to our adopted convention should be negative (opposite to Kepler) (Equation (

5)):

Applying this correction produces a significantly better correlation between our predictions and Doppler velocity.

4.2. Kinetic and Gravitational Potential Energy

To test the preceding hypothesis, five galaxies with high resolution imagery and reliable Doppler velocity data were selected for modelling. Accurate radial mass distribution curves were obtained by extracting grayscale pixel values along the radial axis of each galaxy image. Using a spreadsheet the pixel values were converted into arbitrary mass units according to the shell theorem [

11], which says that all mass within a given radius contributes to the gravitational potential within that radius.

We then scaled the arbitrary mass units by a constant (expressed in units of solar mass) to align it with published baryonic mass estimates. Radial escape velocities were calculated at each interval using these mass profiles. Although the resulting velocity curves followed the expected general shape, they were consistently high and —suggestive of a relativistic influence.

To investigate this, an Einstein gravitational gamma factor (Equation (

6)) was applied to the luminous mass profile to account for relativistic effects due to the gravitational potential near the galactic centre:

When computed across the radial profile, we found ranged from approximately 1.0 up to nearly 2.5— larger than initially expected. Factoring the luminous mass by significantly improved the correlation between calculated and observed Doppler velocities.

Only minor adjustments to the luminosity profile were required to produce large changes in velocity, revealing the model’s sensitivity to mass distribution, it became evident that best agreement with the Doppler data occurred when .

This led to the realisation that an Einstein gravitational gamma factor approaching is not an anomaly but a characteristic feature of stable stellar orbits in galaxies. Deviations from this value are more likely attributable to observational or modelling inaccuracies rather than the presence of exotic physics.

With this understanding, it became a straightforward matter to extract the true mass distribution from any galaxy with high-quality Doppler data, by rearranging the equation for escape velocity and solving for M(r) as in (Equation (

7)):

5. Results

In support of the arguments presented above, Doppler velocity data for several galaxies were obtained from the University of Tokyo rotation curve database [

9], and high resolution images of the corresponding galaxies were sourced from various astronomical archives [

20].

Luminous mass distributions were derived by first converting each galaxy image to grayscale and extracting 8-bit pixel intensity values along the radial axis from the galactic center.

These values were used to construct a radial luminosity profile, which was then converted into arbitrary mass units using the shell theorem [

11], assuming that all enclosed mass contributes to the gravitational potential within a given radius.

The arbitrary units were subsequently scaled by a constant factor (in solar mass units) to yield a luminous mass profile. This profile was then multiplied by the Einstein gravitational gamma factor to obtain the relativistic mass.

No modifications were made to the Doppler data other than inverting the velocity sign, which now placed the rotation curve plot it in the lower right quadrant.

The resulting velocity curves proved highly sensitive to small variations in total mass, indicating that even minor inaccuracies in our luminous mass profile could significantly impact the velocity predictions. Mass estimates as little as 10% over the luminous mass estimates would cause the velocity curve to become asymptotic.

For each galaxy studied, the luminous mass was adjusted to the highest permissible value not exceeding and in all cases, the resulting mass was in good agreement with published baryonic mass estimates.

Additionally, an inferred luminous mass profile was computed directly from the Doppler velocity data using (Equation (

6)), showing excellent correlation with the original image-derived mass distribution.

The following subsections present the results for the five galaxies studied.

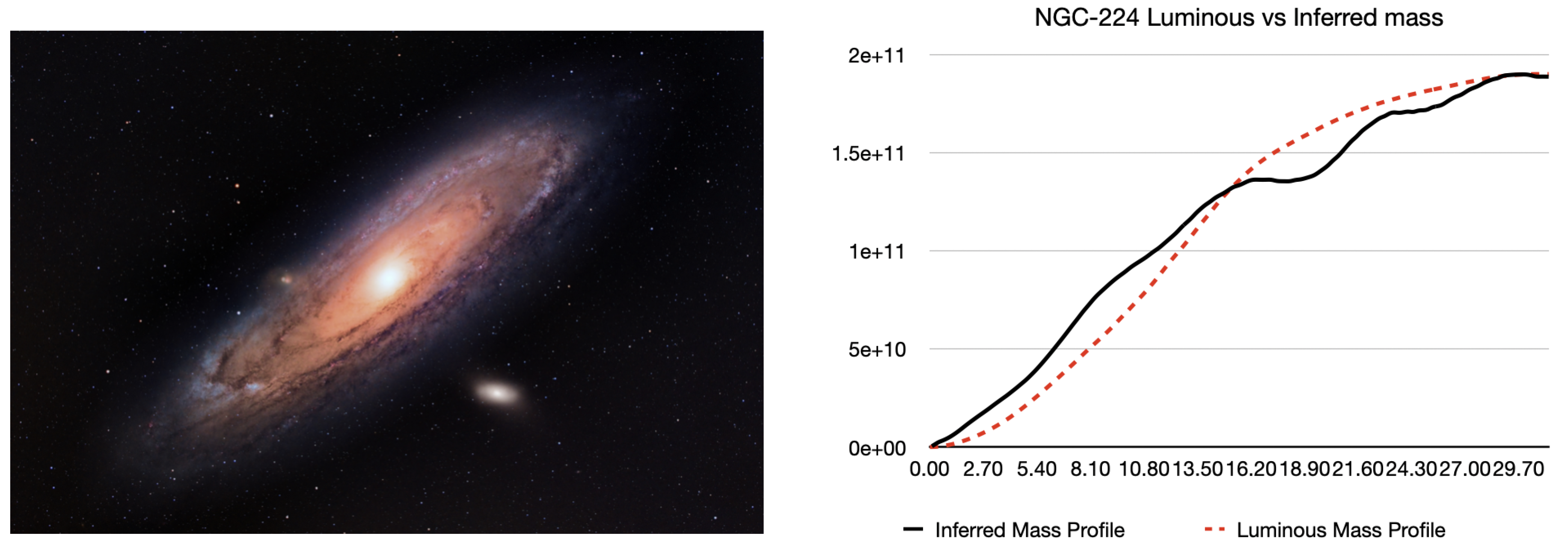

5.1. NGC-224

The Andromeda Galaxy (NGC-224) is the nearest spiral galaxy to the Milky Way and offers the most detailed available observational data. Using the method described above, we obtained a total luminous mass of ,. This is slightly above the currently accepted baryonic mass of Andromeda, which is around ,

As shown in

Figure 6, a slight difference in mass distribution between the estimated luminous mass and the inferred mass is sufficient to bring the orbital velocity (

Figure 6) in line with observations.

1

Figure 6.

NGC-224 Luminous mass distribution.

Figure 6.

NGC-224 Luminous mass distribution.

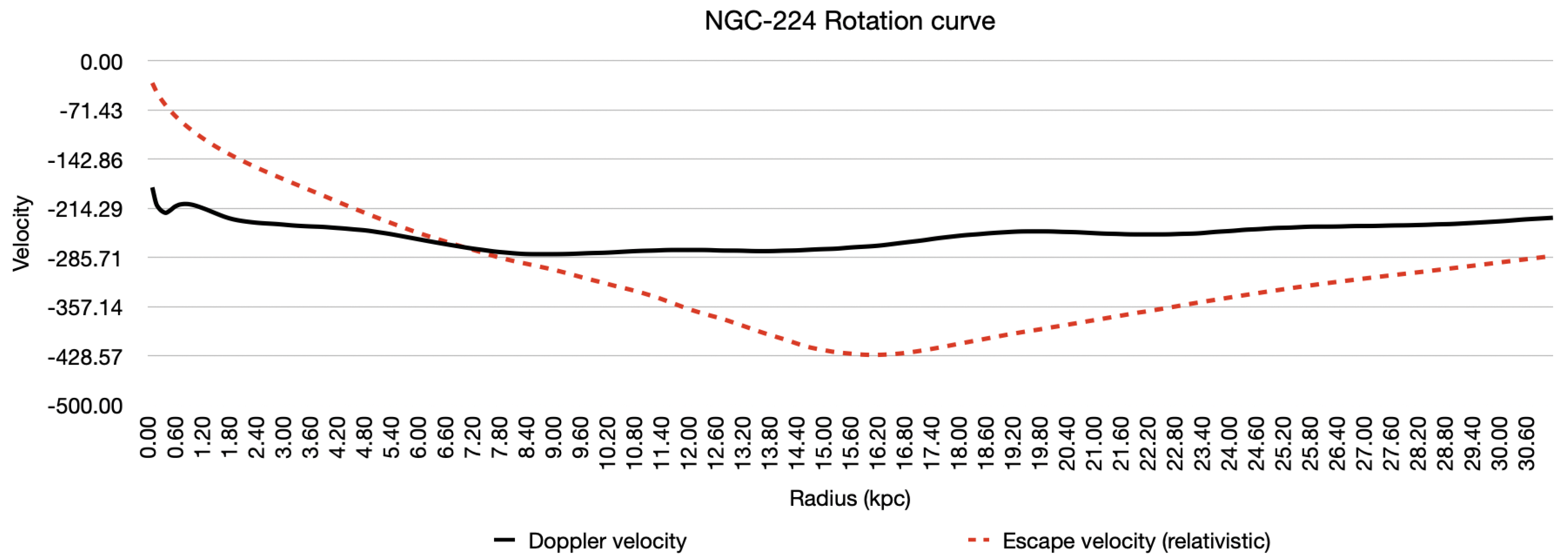

Figure 7.

NGC-224 Doppler vs predicted.

Figure 7.

NGC-224 Doppler vs predicted.

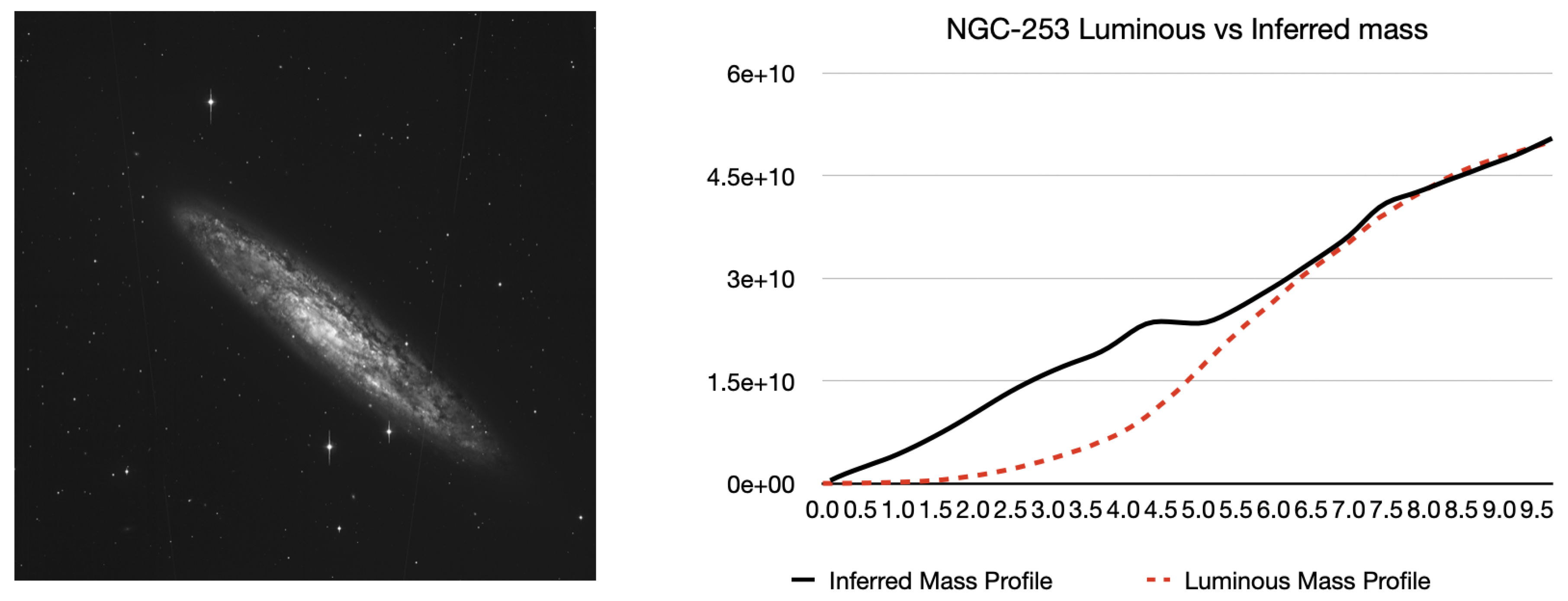

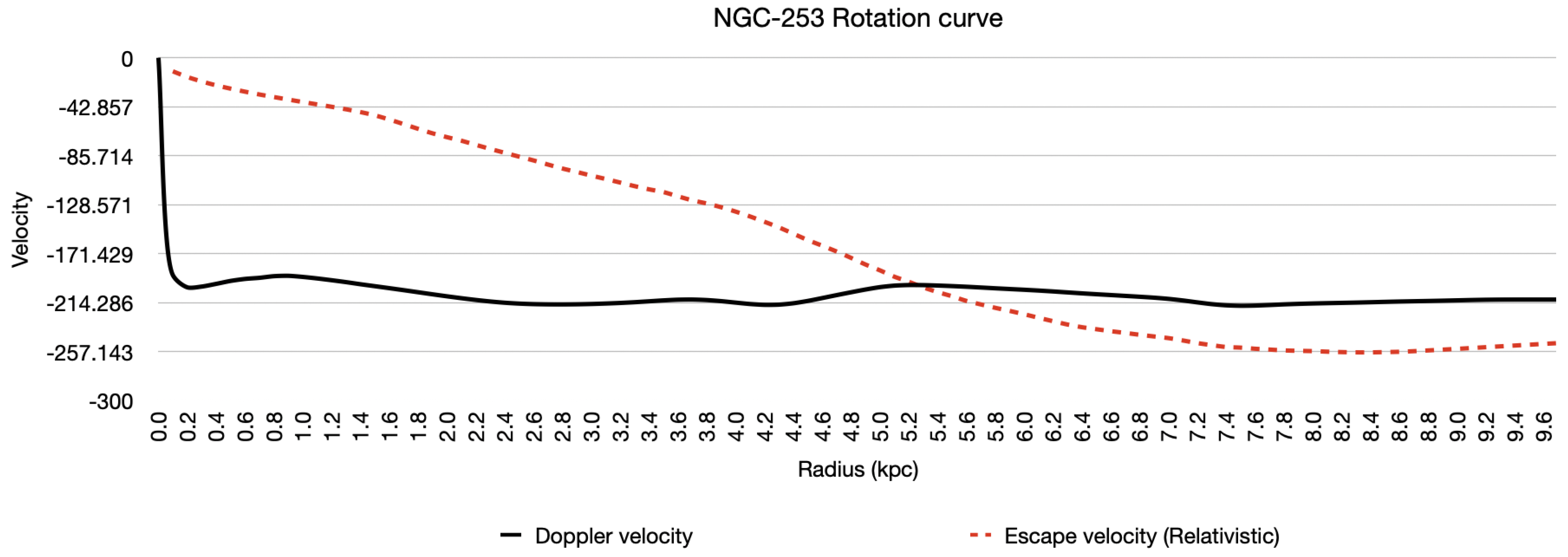

5.2. NGC-253

A similar analysis was performed for NGC-253 also known as the

Sculptor Galaxy (

Figure 8), yielding a total luminous mass of approximately

. A notable discrepancy was observed between the inferred and expected mass in the central region, which we attribute to dust obscuration — a well-documented feature of this galaxy that likely reduces the apparent brightness in the optical band. This underestimation of central mass also affected the derived velocity curve (

Figure 9), resulting in velocities that were slightly higher than expected in the inner region, though the overall profile remains consistent with the observed shape. Our inferred total mass is somewhat higher than the commonly cited baryonic mass estimate of

, but this may be reconciled by accounting for obscured stellar mass and uncertainties in gas content.

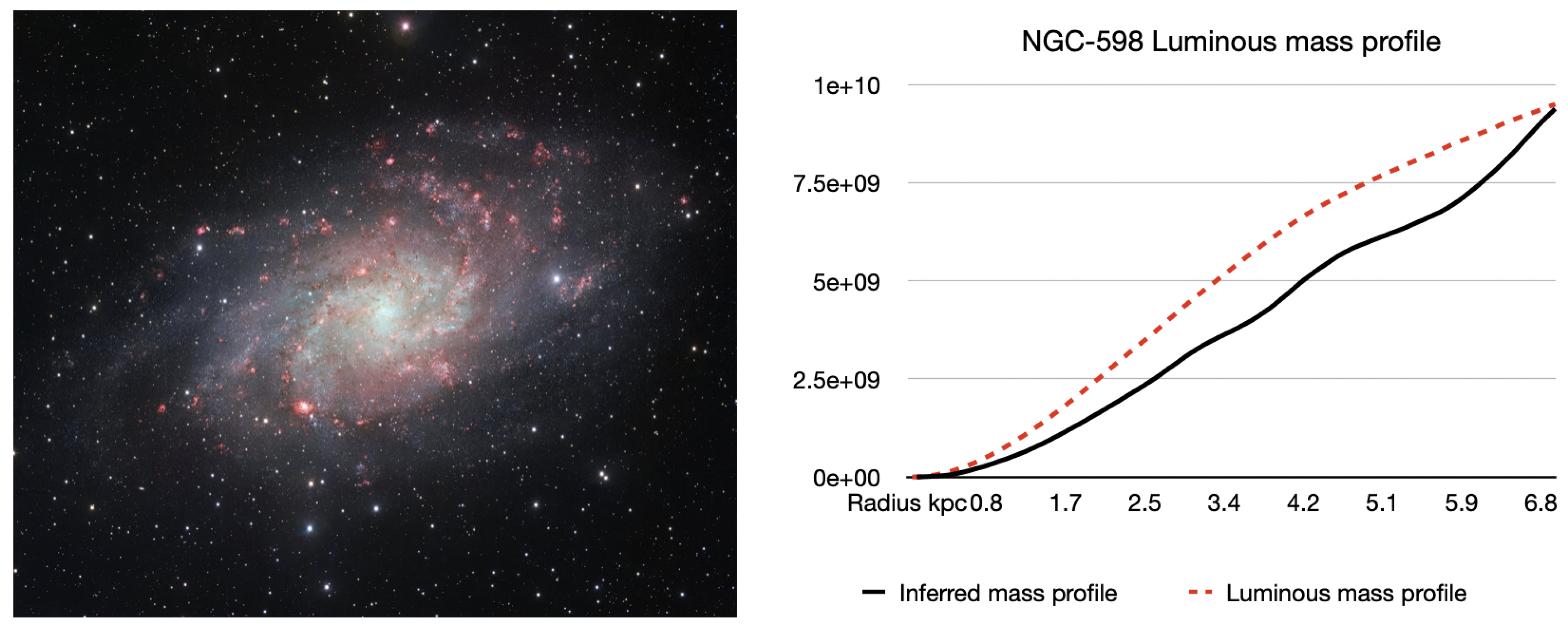

5.3. NGC-598

When put through the same analysis NGC-598 (

Figure 10) came out with an inferred mass of

, once again showing how our luminous mass profile was somewhat off the mark. Our inferred mass shows this galaxy to be somewhat lighter than suggested by prior work which is

.

Figure 10.

NGC-598 luminous mass distribution.

Figure 10.

NGC-598 luminous mass distribution.

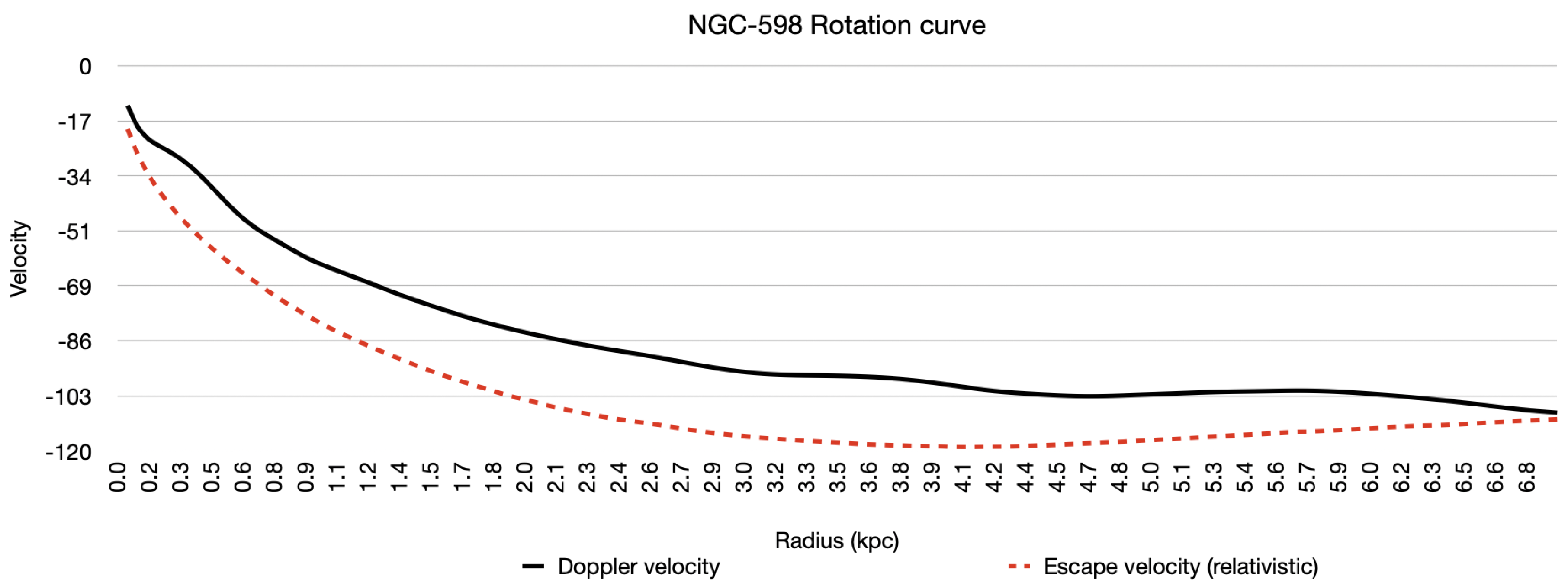

Figure 11.

NGC-598 Doppler vs predicted.

Figure 11.

NGC-598 Doppler vs predicted.

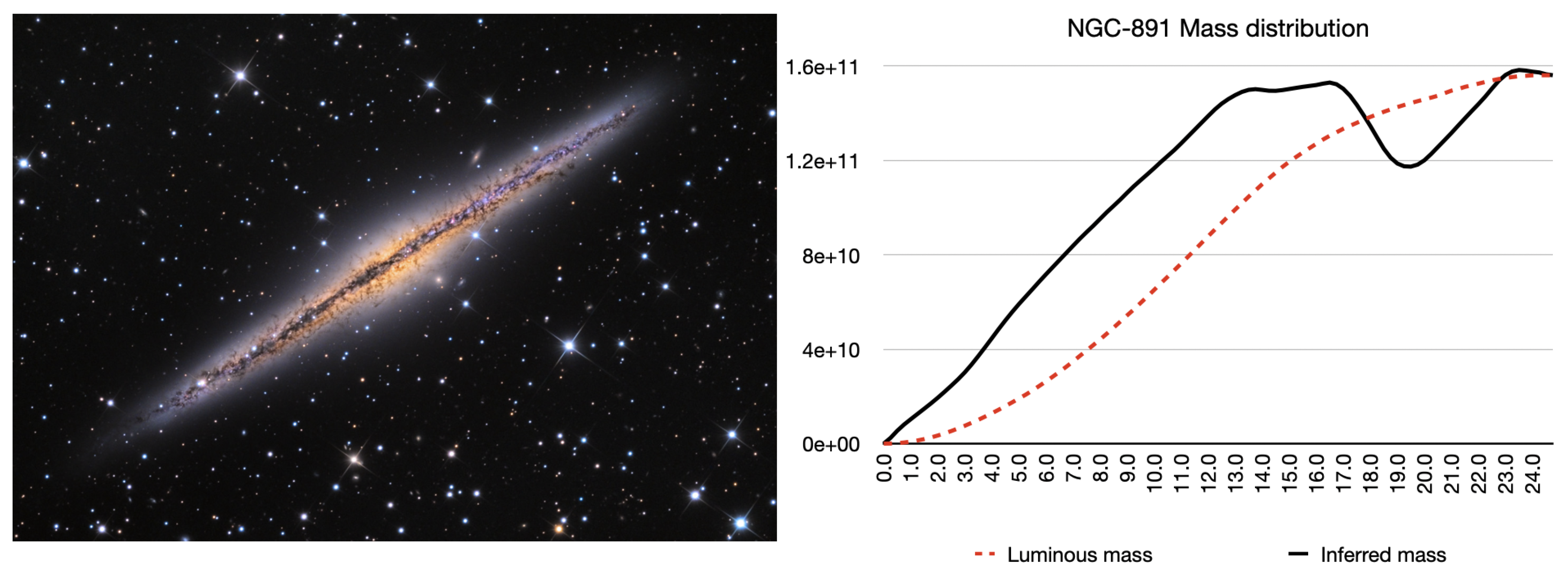

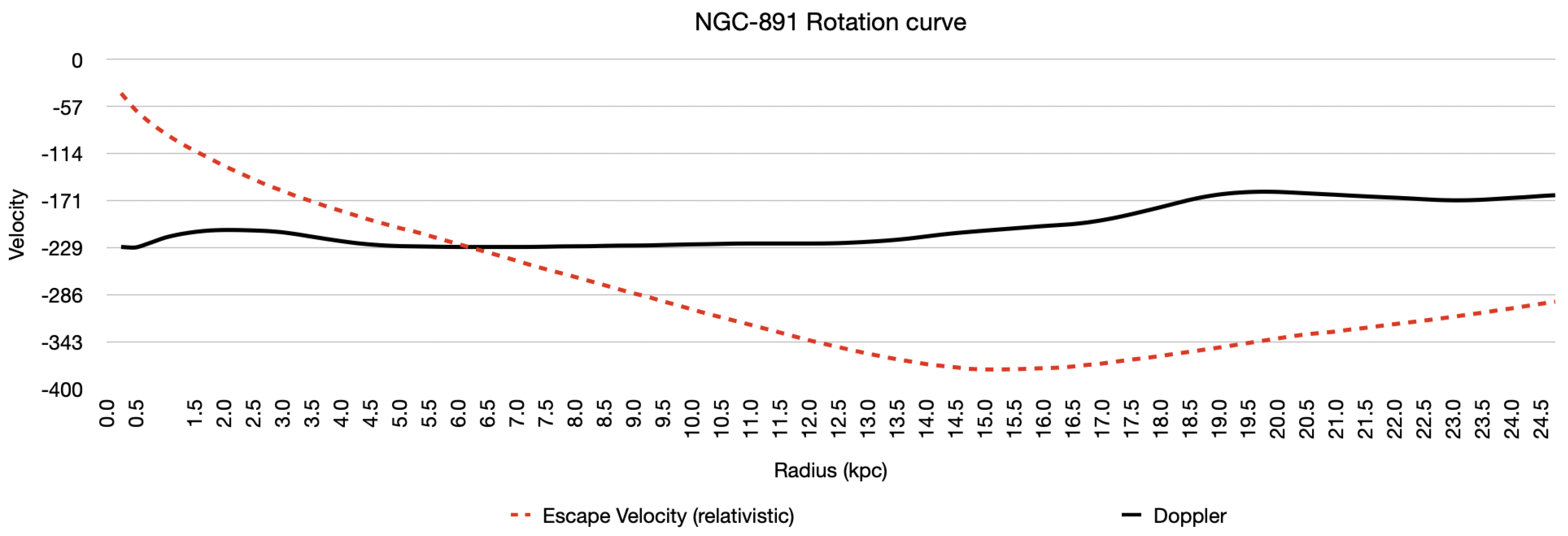

5.4. NGC-891

NGC-891 also known as

Silver Sliver Galaxy (

Figure 12) is around 30 million light years away and presents almost exactly edge on. A rim of dust obscures the luminous regions making luminous mass measurements difficult. Once again our luminous mass estimate

agrees with published values.

Figure 12.

NGC-891 luminous mass distribution.

Figure 12.

NGC-891 luminous mass distribution.

Figure 13.

NGC-891 Doppler vs predicted.

Figure 13.

NGC-891 Doppler vs predicted.

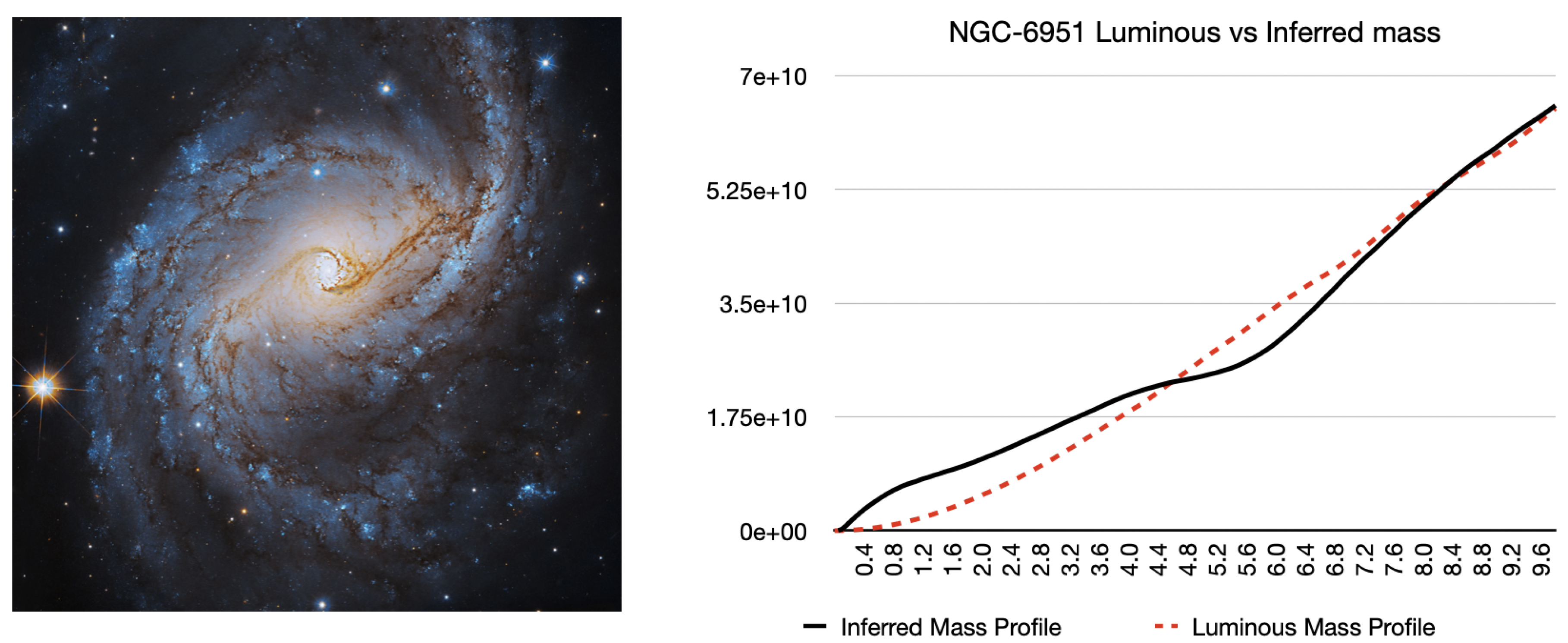

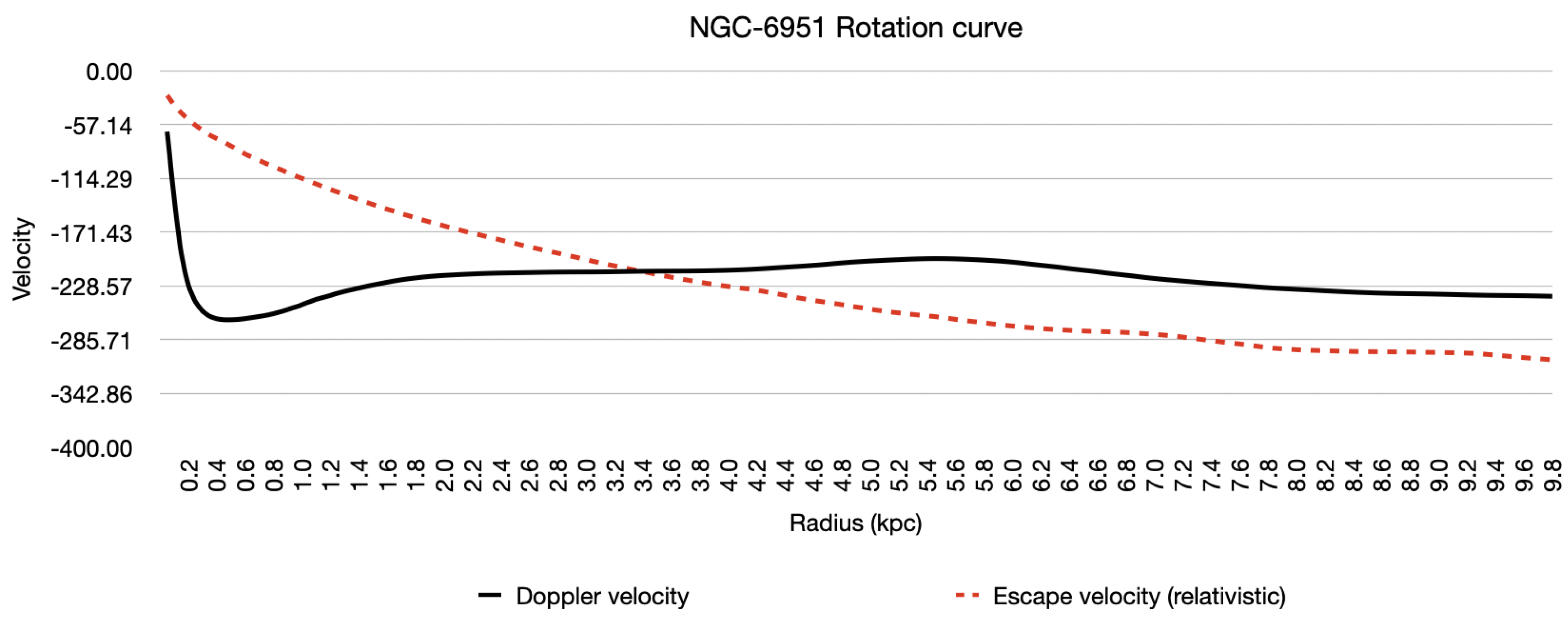

5.5. NGC-6951

NGC-6951 is a barred galaxy at a distance of about 75 million light years. We were not able to find the value of the baryonic mass from the available literature, however our inferred maximum mass based on the doppler velocity is .

Figure 14.

NGC-6951 luminous mass distribution.

Figure 14.

NGC-6951 luminous mass distribution.

Figure 15.

NGC-6951 Doppler vs predicted.

Figure 15.

NGC-6951 Doppler vs predicted.

6. Discussion

The analysis presented in this paper introduces three essential concepts:

The use of consistent reference frames between Doppler spectroscopy and Keplerian orbital models,

The understanding of how orbital-velocity is observed as escape-velocity from outside an orbit, and

The application of a Einstein gravitational-potential gamma factor to galactic-scale systems.

These three corrections appear to resolve the long-standing discrepancy between observed and predicted galaxy rotation curves. Not only do they eliminate the need to invoke non-baryonic dark matter, but they also enable accurate mass distribution estimates in galaxies located thousands of light-years away.

Considering the current global effort to detect dark matter, it would be in the interest of the scientific community to re-evaluate existing rotation curve data within this framework.

A significant amount of doppler spectroscopy data and high resolution astronomical images already exists, making this a fruitful area of research.

At the very least, this work shines a light on the critical importance of clearly defining measurement frames in astrophysical modelling. Continued work with an open-minded approach will be essential for testing the robustness and general applicability of this method.

7. Conclusion

This work shows how galaxy rotation curves and luminous mass can be reconciled without resorting to the dark matter hypothesis. By applying three corrections to classical orbital mechanics, inversion of reference frame, factorisation by and an Einstein gravitational factor, the rotation curves agree with estimated luminous mass to a good approximation.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement The author would like to thanks scientists and the organisations funding them, both in the past and in the present, for the images and data used in this research. The author acknowledges using AI tools like chat GPT 4.0 for spell checking, grammar correction and assistance with LaTex and takes full responsibility for the intellectual content of this publication, most of which came from insights developed in earlier works,

All you need is potential [

7].

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that this research was entirely self funded and that no conflict of interest with third parties exists.

References

- Rubin V.C., Ford W.K. Jr., Thonnard N. Rotational properties of 21 Sc galaxies with a large range of luminosities. The Astrophysical Journal, 1980, v.238, 471–487.

- Milgrom M. A modification of the Newtonian dynamics as a possible alternative to the hidden mass hypothesis. Astrophysical Journal, 1983, v.270, 365–370.

- Caspar M. Kepler. Dover Publications, 1993.

- Christianson J. R. On Tycho’s Island: Tycho Brahe and His Assistants, 1570–1601. Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Gray D. F. The Observation and Analysis of Stellar Photospheres. 3rd ed., Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Carroll B. W., Ostlie D. A. An Introduction to Modern Astrophysics. 2nd ed., Pearson, 2017.

- Sesselmann S.A., All you need is potential. [CrossRef]

- Newton I. Principia Mathematica. (Original Publication).

- Sofue Y. Rotation Curves of Spiral Galaxies. https://www.ioa.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp/~sofue/RC99/rc99.htm.

- Zwicky F. On the Masses of Nebulae and Clusters of Nebulae. Astrophysical Journal, 1937, v.86, October.

- Shell Theorem. Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shell_theorem.

- Halliday D., Resnick R., Walker J. Fundamentals of Physics. 10th ed., Wiley, 2013.

- Hubble E. A Relation between Distance and Radial Velocity among Extra-Galactic Nebulae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 1929, v.15(3), pp.168–173.

- Akerib, D.S., et al. Results from a Search for Dark Matter in the Complete LUX Exposure. Physical Review Letters, 2017, 118(2), 021303.

- Aprile, E., et al. Observation of Excess Electronic Recoil Events in XENON1T. Physical Review D, 2020, 102(7), 072004.

- Akerib, D.S., et al. First Dark Matter Search Results from the LUX-ZEPLIN (LZ) Experiment. arXiv:2207.03764, 2022.

- Cui, X., et al. Dark Matter Results from 54-Ton-Day Exposure of PandaX-II Experiment. Physical Review Letters, 2021, 126, 211301.

- Agnese, R., et al. Projected Sensitivity of the SuperCDMS SNOLAB Experiment. Physical Review D, 2020, 102, 052009.

- Navarro J. F., Frenk C. S., White S. D. M. A Universal Density Profile from Hierarchical Clustering. Astrophysical Journal, 1997, v.490, pp.493–508. [CrossRef]

- European Southern Observatory, Image search, https://www.eso.org/public/images/search/.

| 1 |

This illustrates the sensitivity of relativistic orbital models to even small variations in radial mass distribution. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).