Submitted:

13 May 2025

Posted:

13 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

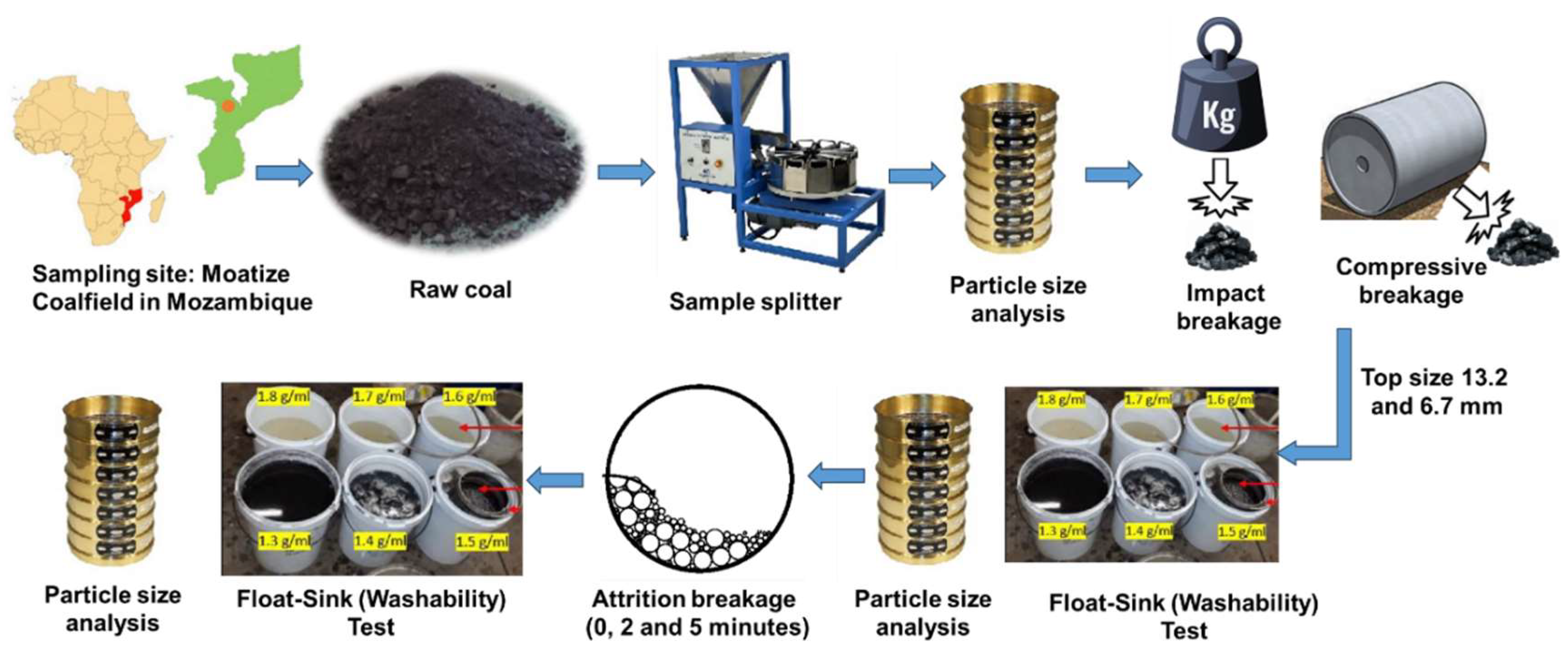

2. Experimental Procedures

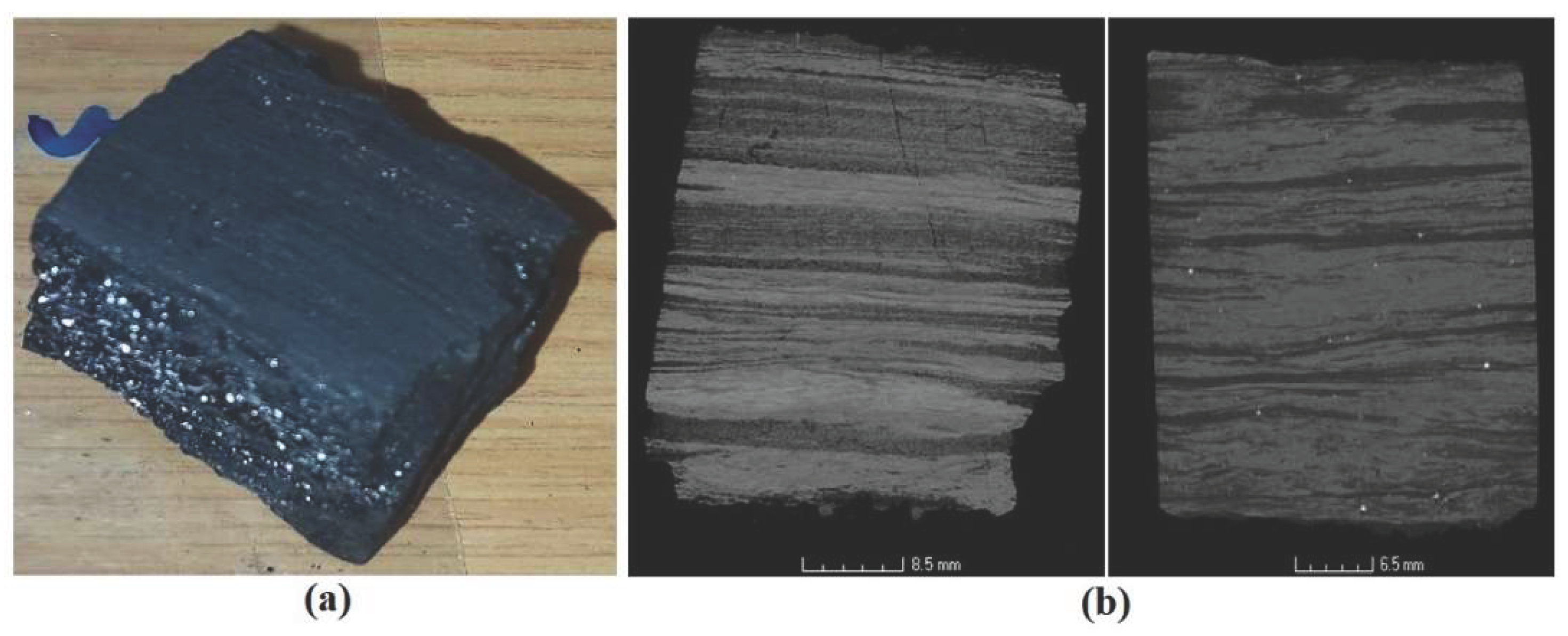

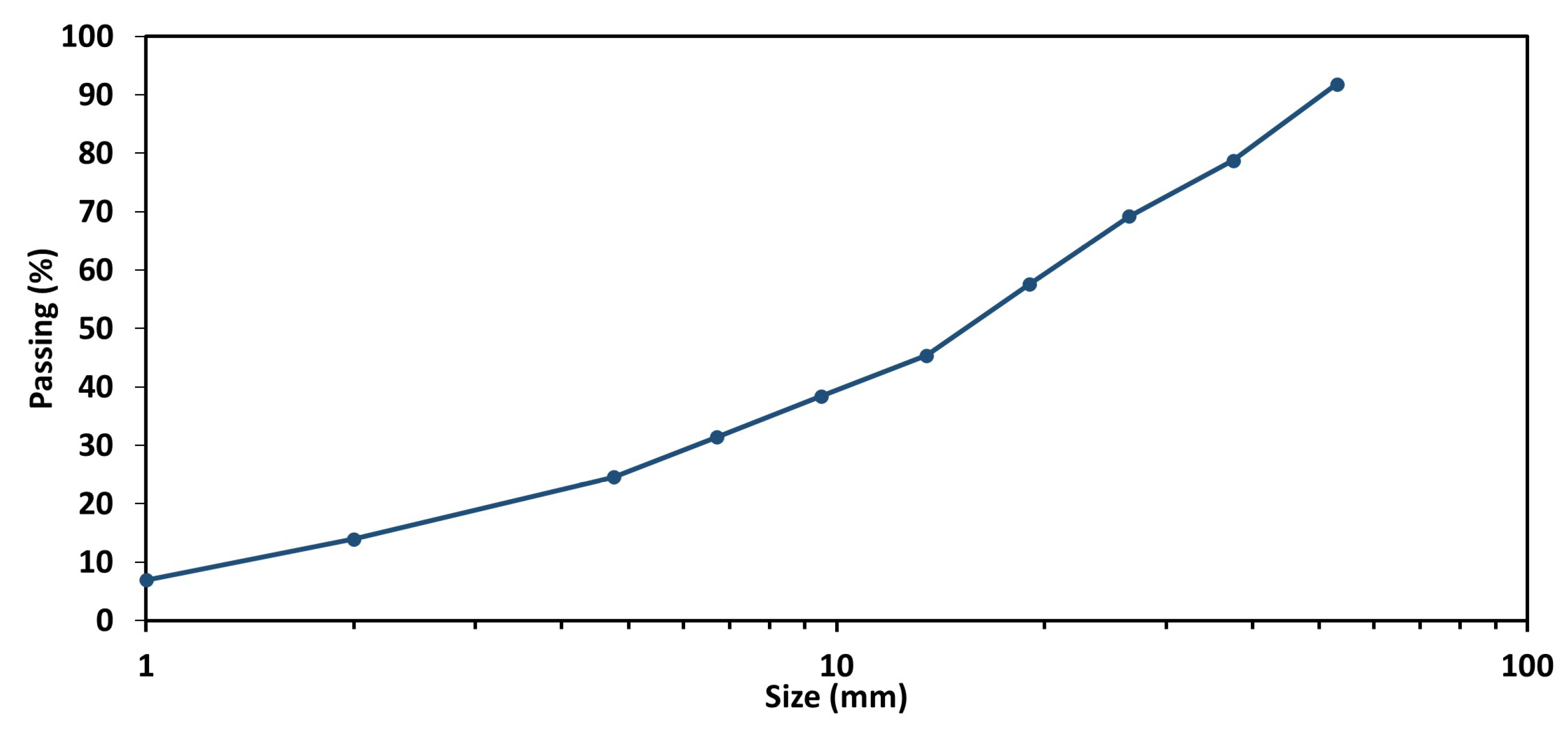

2.1. Materials

2.2. Experimental Design and Breakage Strategy

3. Results

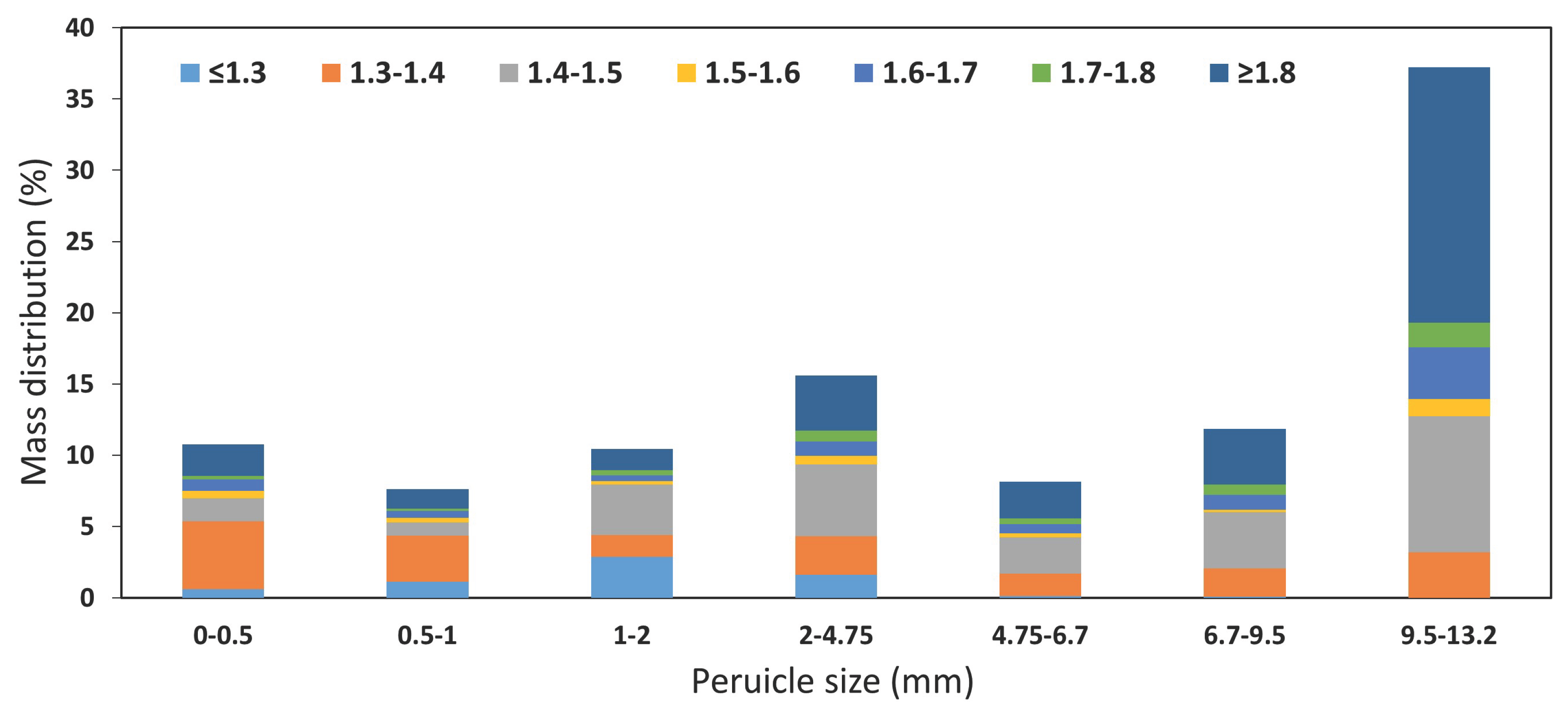

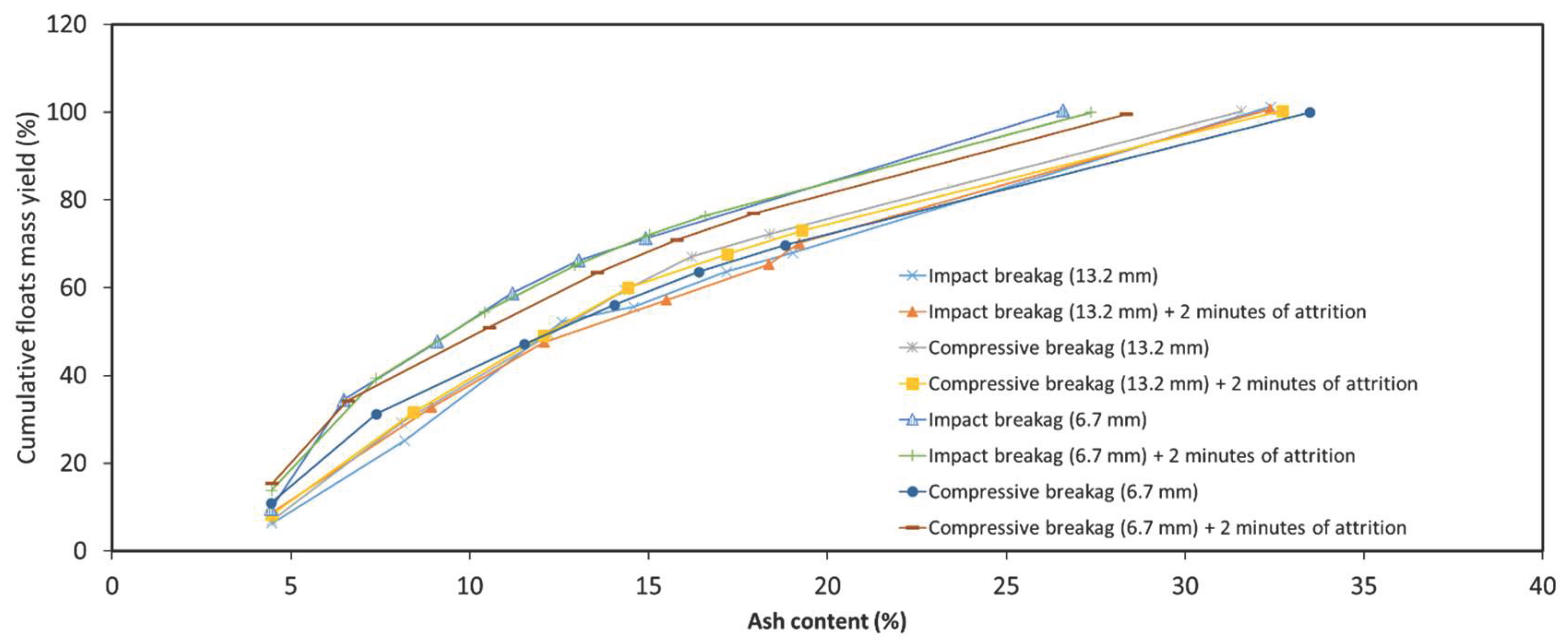

3.1. Effect of Impact and Attrition Breakage on Size-by-Washability Distribution

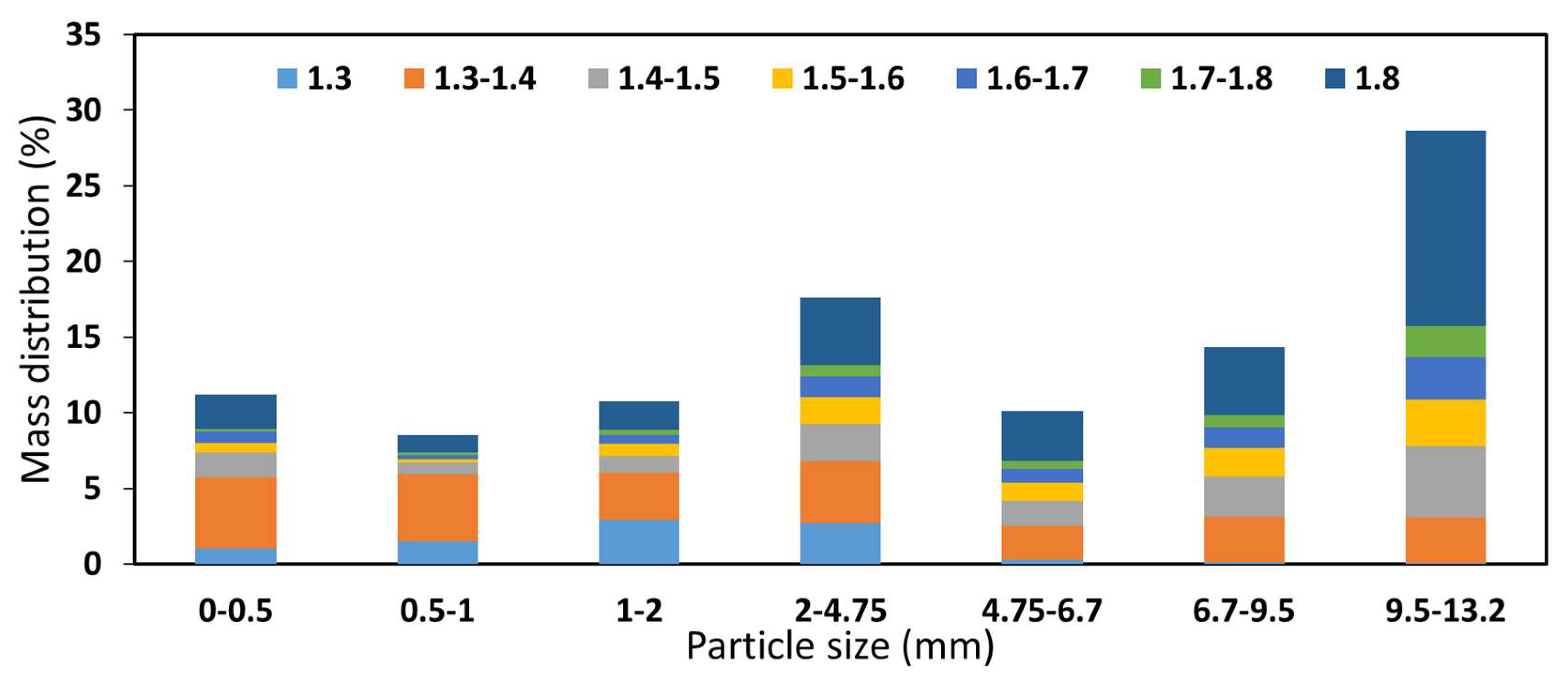

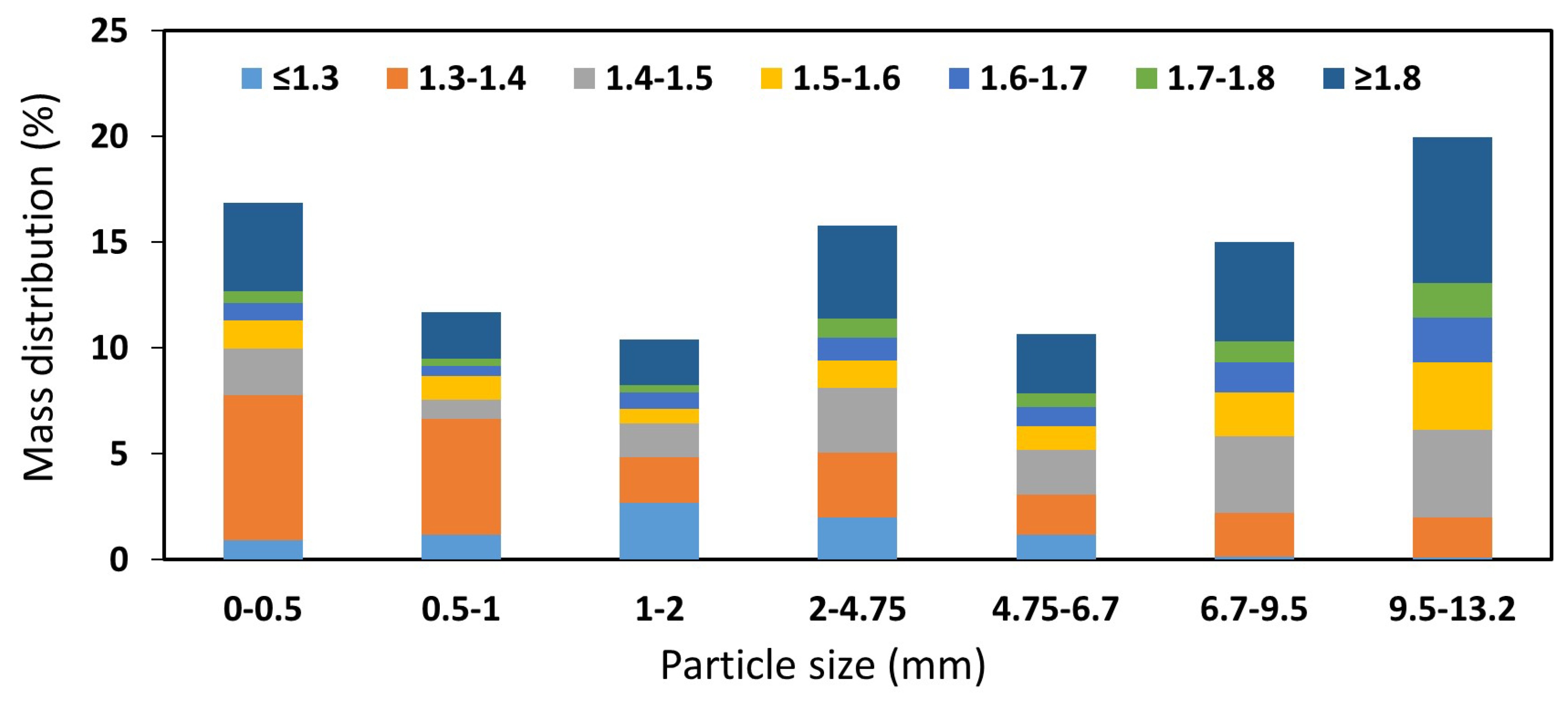

3.1.1. Top Particle Size of 13.2 mm

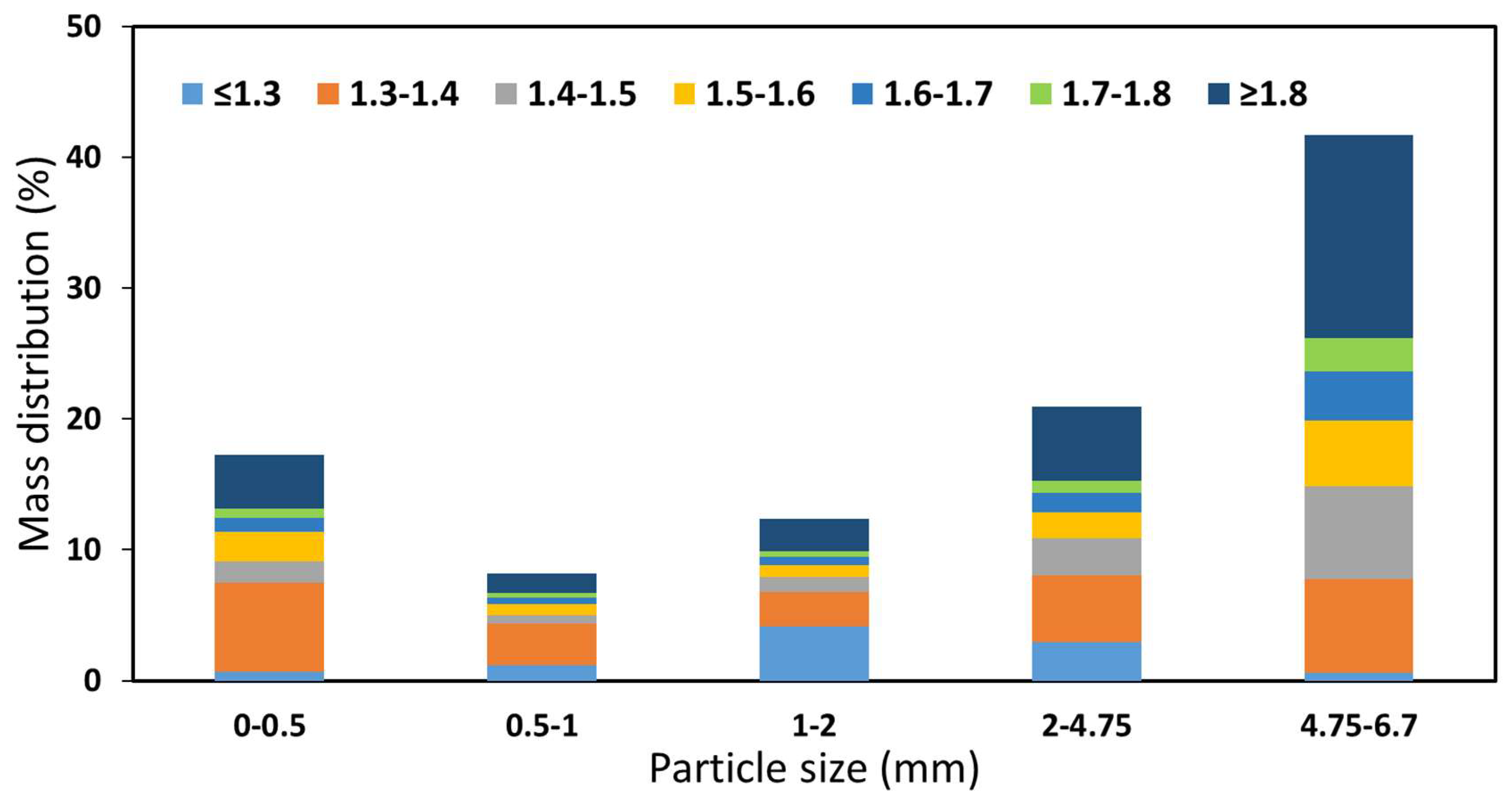

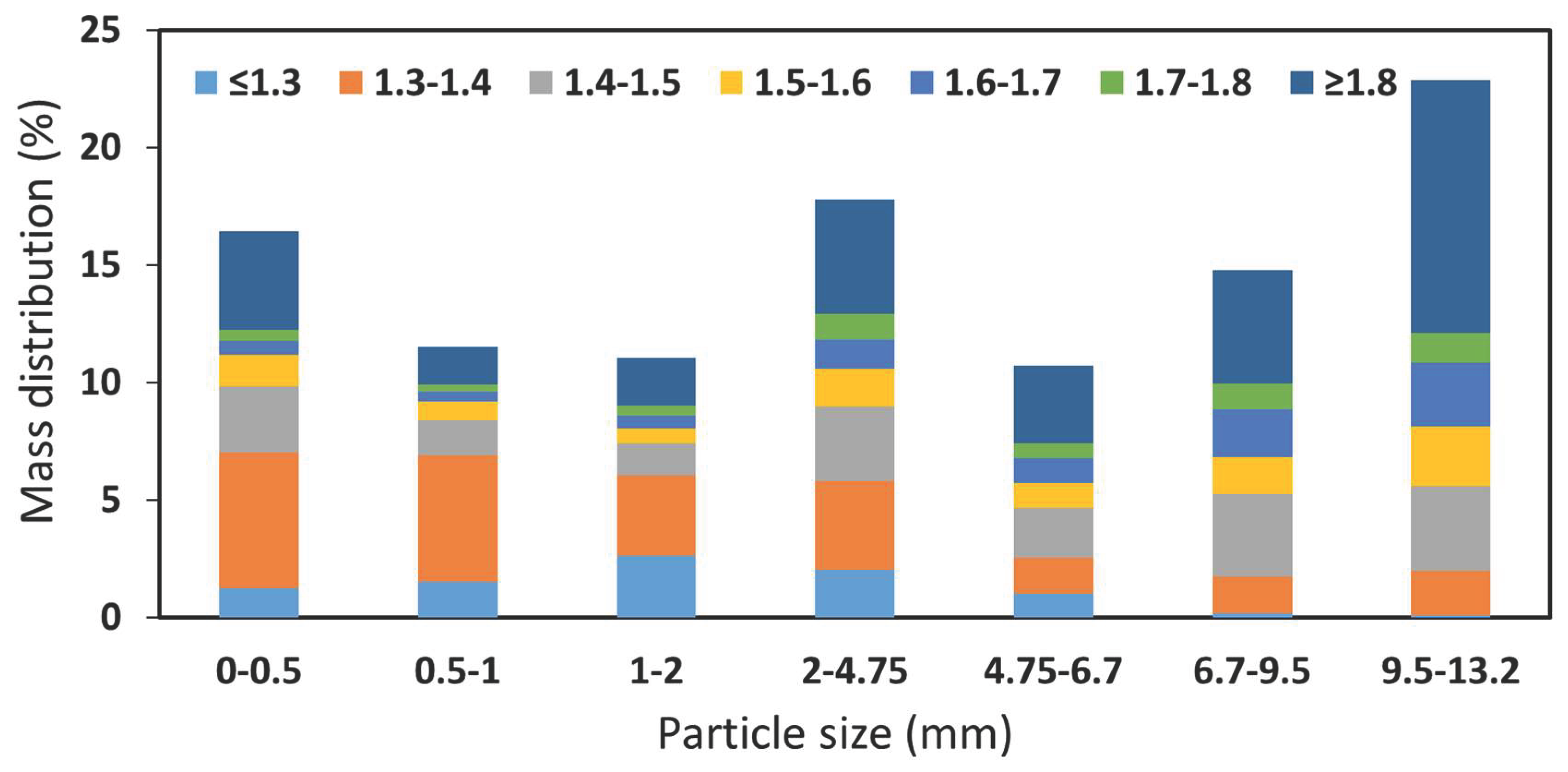

3.1.2. Top Particle Size of 6.7 mm

3.2. Effect of Compressive and Attrition Breakage on Size-by-Washability Distribution

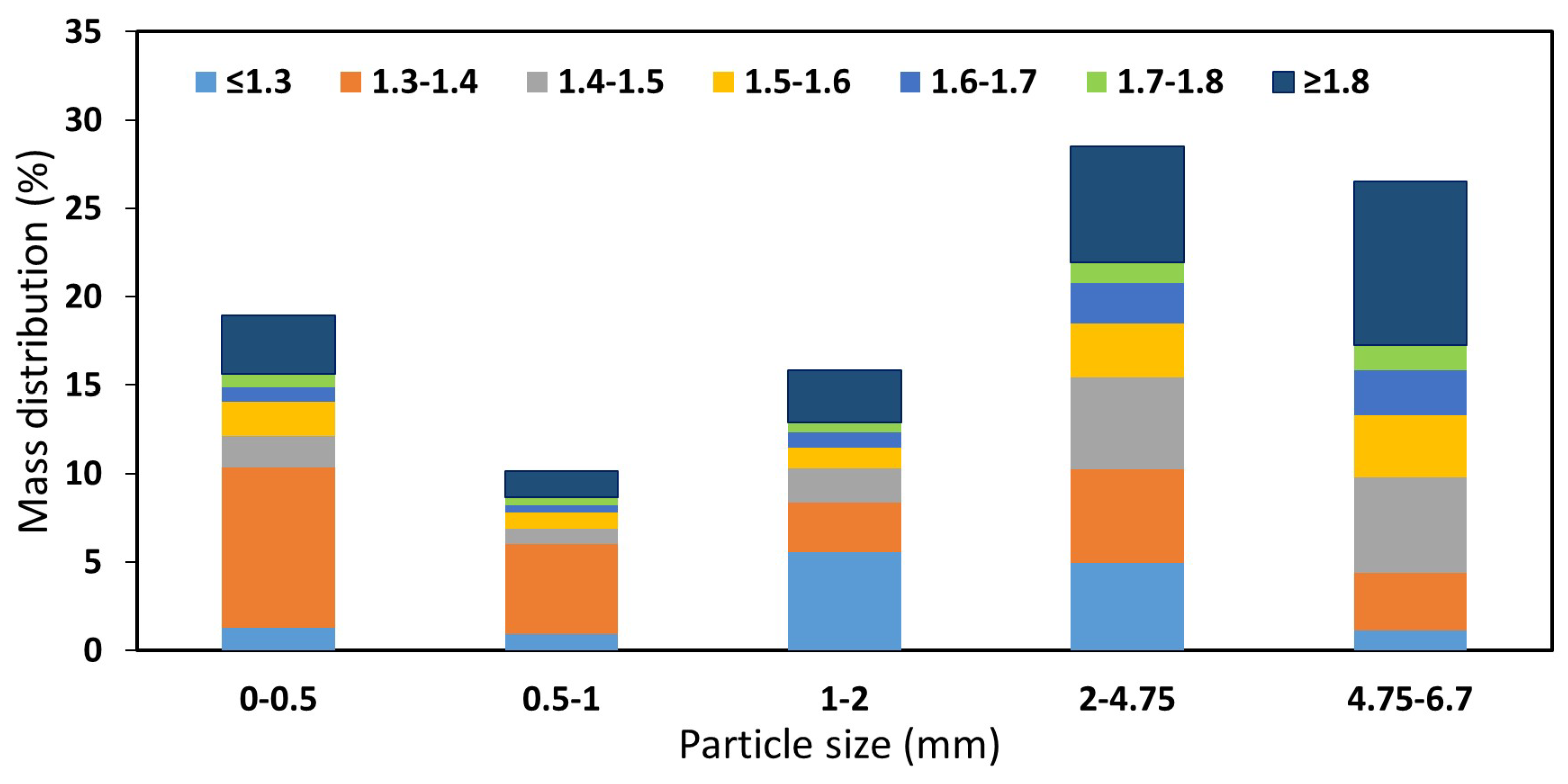

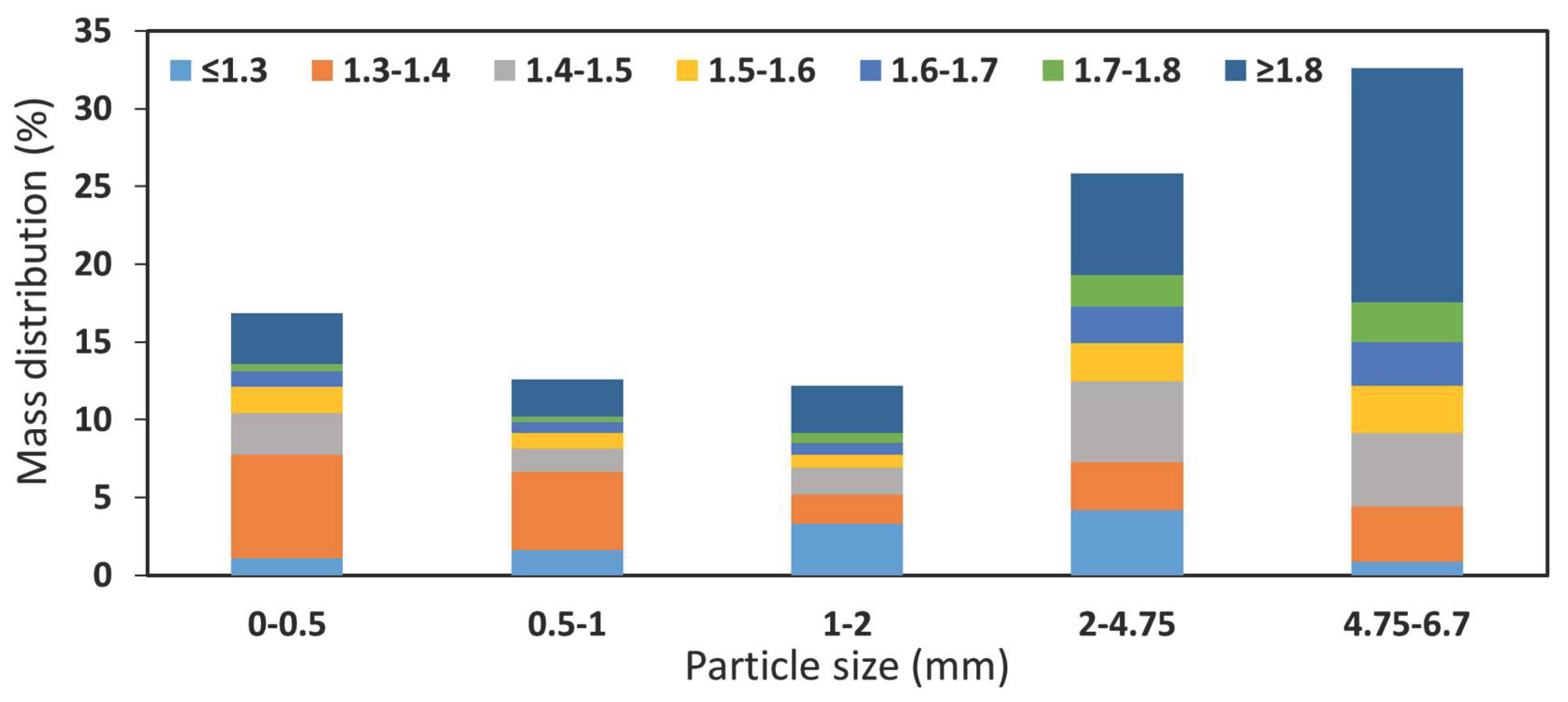

3.2.1. Top Particle Size of 13.2 mm

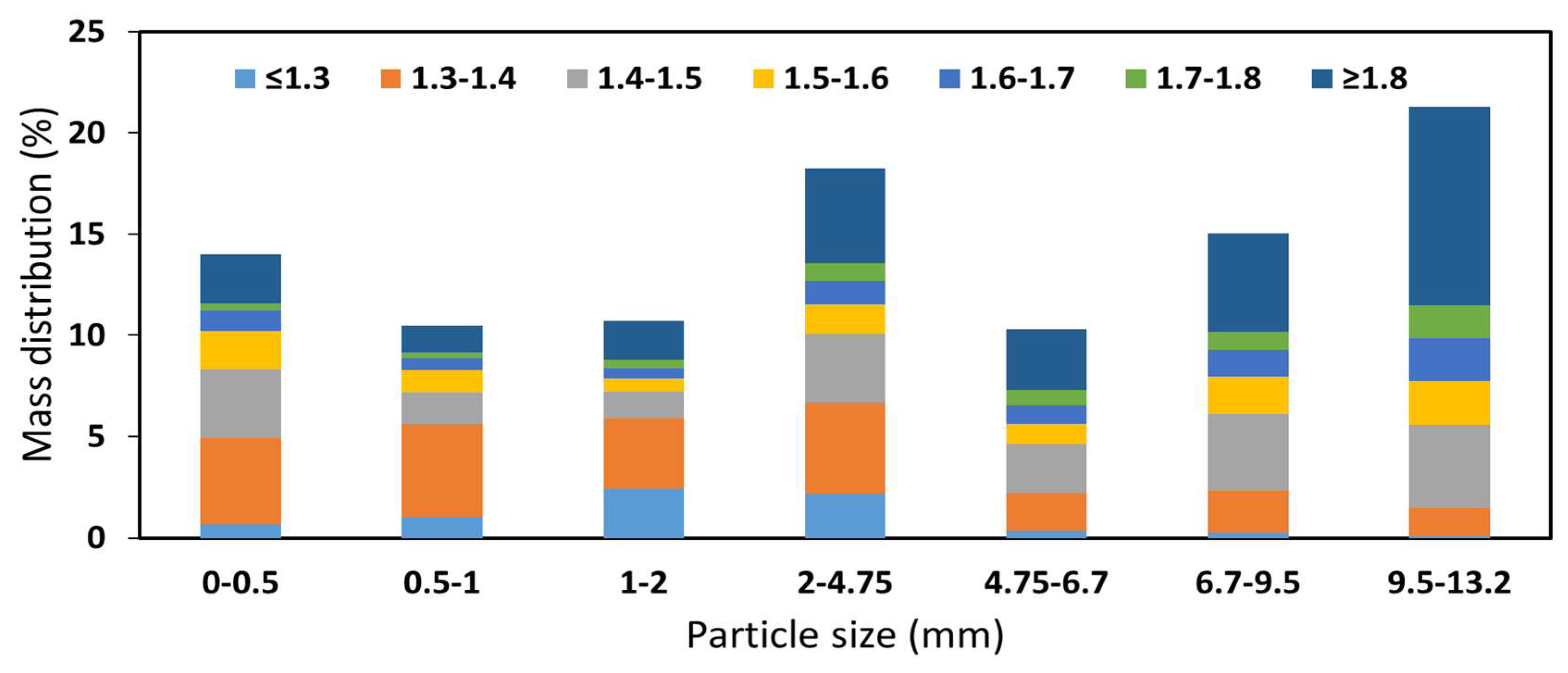

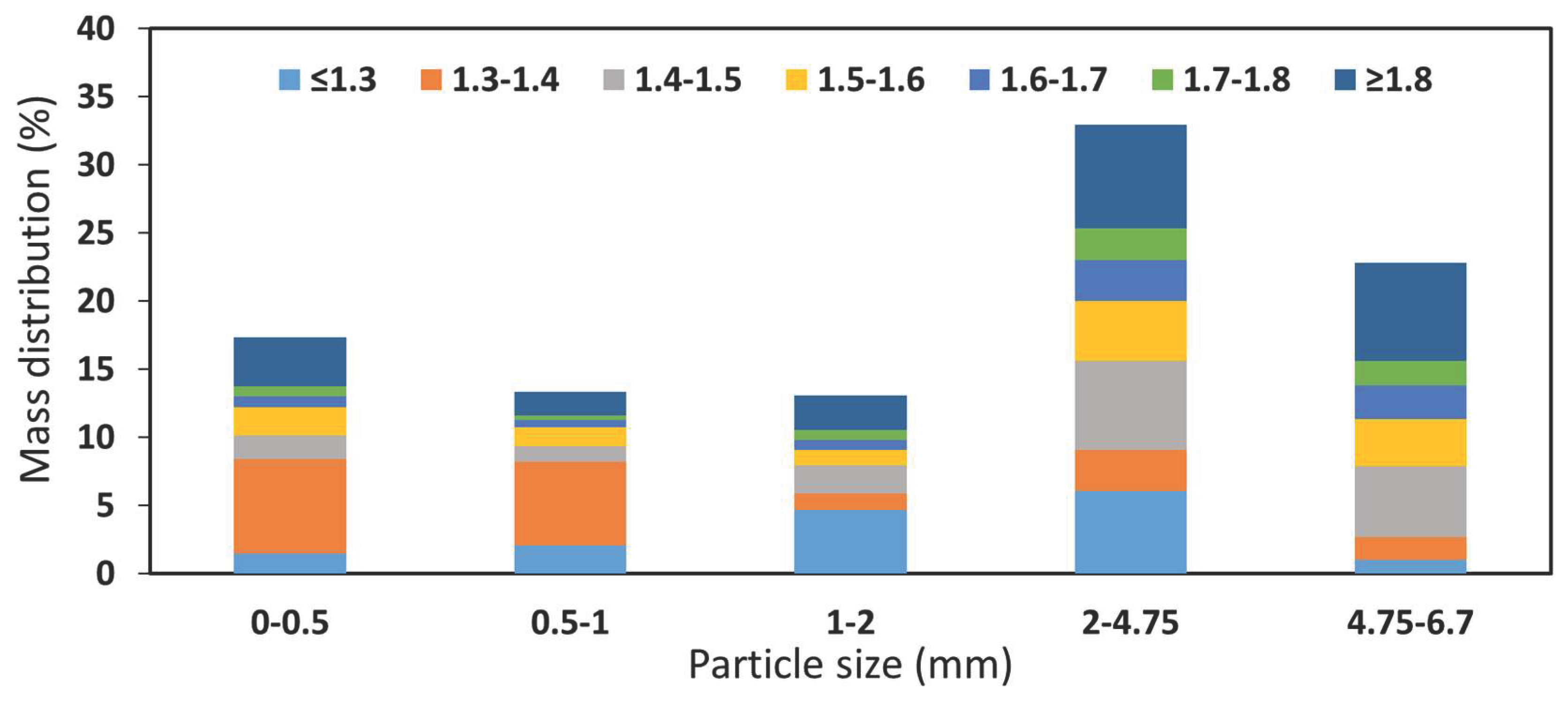

3.2.2. Top Particle Size of 6.7

4. Conclusions

References

- Guldris Leon, L.; Bengtsson, M. Selective Comminution Applied to Mineral Processing of a Tantalum Ore: A Technical, Economic Analysis. Minerals 2022, 12, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norgate, T.; Haque, N. Energy and Greenhouse Gas Impacts of Mining and Mineral Processing Operations. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeswiet, J.; Szekeres, A. Energy Consumption in Mining Comminution. Procedia CIRP 2016, 48, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Kojovic, T.; Larbi-Bram, S.; Manlapig, E. Development of a Rapid Particle Breakage Characterisation Device: The JKRBT. Miner. Eng. 2009, 22, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reedy, R.C.; Scanlon, B.R.; Bagdonas, D.A.; et al. Coal Ash Resources and Potential for Rare Earth Element Production in the United States. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2024, 11, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhaei, F.; Corchado-Albelo, J.; Alagha, L.; Moats, M.; Munoz-Garcia, N. Progress, Challenges, and Perspectives of Critical Elements Recovery from Sulfide Tailings. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankefa, T.; Nasah, J.; Laudal, D.; Andraju, N. Advances in Efficient Utilization of Low-Rank Fuels in Coal and Biomass-Fired Systems: A Comprehensive Review. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinbami, O.M.; Oke, S.R.; Bodunrin, M.O. The State of Renewable Energy Development in South Africa: An Overview. Alex. Eng. J. 2021, 60, 5077–5093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botlhoko, S.; Campbell, Q.P.; Le Roux, M.; Nakhaei, F. Application of Rhovol Information for Coal Washability Analysis. In Proceedings of the Coal Processing Conference, Secunda, South Africa; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Botlhoko, S.; Campbell, Q.P.; Le Roux, M.; Nakhaei, F. Washability Analysis of Coal Using RhoVol: A Novel 3D Image-Based Method. Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. Rev. 2023, 44, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Q.P.; Le Roux, M.; Nakhaei, F. Coal Moisture Variations in Response to Rainfall Events in Mine and Coal-Fired Power Plant Stockpiles—Part 2: Evaporation. Minerals 2021, 11, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Du, M.; Liu, L. Study on the Liberation of Organic Macerals in Coal by Liquid Nitrogen Quenching Pretreatment. Minerals 2020, 10, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, N.; Le Roux, M.; Campbell, Q.P.; Nakhaei, F. A Review of the Dry Methods Available for Coal Beneficiation. Miner. Eng. 2024, 216, 108847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornn, V.; Ito, M.; Yamazawa, R.; Shimada, H.; Tabelin, C.B.; Jeon, S.; Park, I.; Hiroyoshi, N. Kinetic Analysis for Agglomeration-Flotation of Finely Ground Chalcopyrite: Comparison of First-Order Kinetic Model and Experimental Results. Mater. Trans. 2020, 61, 1940–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zancan, P.M.; De Brum, I.A.S.; Ambrós, W.M.; Sampaio, C.H.; Moncunill, J.O. Influence of Igneous Intrusions on Coal Flotation Feasibility: The Case of Moatize Mine, Mozambique. Minerals 2023, 13, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornn, V. , Ito, M., Shimada, H., Tabelin, C. B., Jeon, S., Park, I., & Hiroyoshi, N. (2020). Agglomeration–flotation of finely ground chalcopyrite using emulsified oil stabilized by emulsifiers: Implications for porphyry copper ore flotation. Metals, 10(7), 912.

- Seetharaman, S. (Ed.). (2014). Treatise on Process Metallurgy: Volume 3 – Industrial Processes. Elsevier.

- Viljoen, J. , Campbell, Q. P., Le Roux, M., & De Beer, F. (2015). An analysis of the slow compression breakage of coal using microfocus X-ray computed tomography. International Journal of Coal Preparation and Utilization, 35, 1–13.

- Phengsaart, T. , Srichonphaisan, P., Kertbundit, C., Soonthornwiphat, N., Sinthugoot, S., Phumkokrux, N., Juntarasakul, O., Maneeintr, K., Numprasanthai, A., Park, I., Tabelin, C. B., Hiroyoshi, N., & Ito, M. (2023). Conventional and recent advances in gravity separation technologies for coal cleaning: A systematic and critical review. Heliyon, 9(2), e13083.

- O’Brien, G. Firth, B., & Adair, B. (2011). The application of the coal grain analysis method to coal liberation studies. International Journal of Coal Preparation and Utilization. 31, 2, 96–111.

- Falcon, L. M. Falcon, R. M. S. (1987). The petrographic composition of Southern African coals in relation to friability, hardness, and abrasive indices. Journal of the South African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy. 87, 10, 323–336.

- Shi, F. (2014). Coal breakage characterization – Part 2: Multi-component breakage modelling. Fuel, 117, 1156–1162.

- Kuwik, B. S. Garcia, M., & Hurley, R. C. (2022). Experimental breakage mechanics of confined granular media across strain rates and at high pressures. International Journal of Solids and Structures. 259, 112024.

- Oberholzer, V. Van der Walt, J. (2009). Investigation of factors influencing the attrition breakage of coal. Journal of the Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy. 109, 4, 211–216.

- Wills, B. A. , & Finch, J. A. (2016). Wills’ Mineral Processing Technology: An Introduction to the Practical Aspects of Ore Treatment and Mineral Recovery (8th ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Martinelli, G. , Plescia, P., Tempesta, E., Paris, E., & Gallucci, F. (2020). Fracture analysis of α-quartz crystals subjected to shear stress. Minerals, 10(10), 870.

- Cleary, P. W. , Delaney, G. W., Sinnott, M. D., Cummins, S. J., & Morrison, R. D. (2020). Advanced comminution modelling: Part 1 – Crushers. Applied Mathematical Modelling, 88, 238–265.

- Moraga, C.; Astudillo, C.A.; Estay, R.; Maranek, A. Enhancing Comminution Process Modeling in Mineral Processing: A Conjoint Analysis Approach for Implementing Neural Networks with Limited Data. Mining 2024, 4, 966–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parapari, P.S.; Parian, M.; Rosenkranz, J. Breakage process of mineral processing comminution machines – An approach to liberation. Adv. Powder Technol. 2020, 31, 3669–3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewuyi, S.O.; Ahmed, H.A.M.; Ahmed, H.M.A. Methods of Ore Pretreatment for Comminution Energy Reduction. Minerals 2020, 10, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewuyi, S.O.; Ahmed, H.A.M.; Anani, A.; Saeed, A.; Ahmed, H.M.; Alwafi, R.; Luxbacher, K. Enhancing Iron Ore Grindability through Hybrid Thermal-Mechanical Pretreatment. Minerals 2024, 14, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingman, S.W. Recent developments in microwave processing of minerals. Int. Mater. Rev. 2006, 51, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heshami, M.; Ahmadi, R. Effect of thermal treatment on specific rate of breakage of manganese ore. J. Min. Environ. 2018, 9, 339–348. [Google Scholar]

- Wonnacott, G.; Wills, B.A. Optimisation of Thermally Assisted Liberation of a Tin Ore with the Aid of Computer Simulation. Miner. Eng. 1990, 3, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toprak, N.A.; Altun, O.; Aydogan, N.; Benzer, H. The influences and selection of grinding chemicals in cement grinding circuits. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 68, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

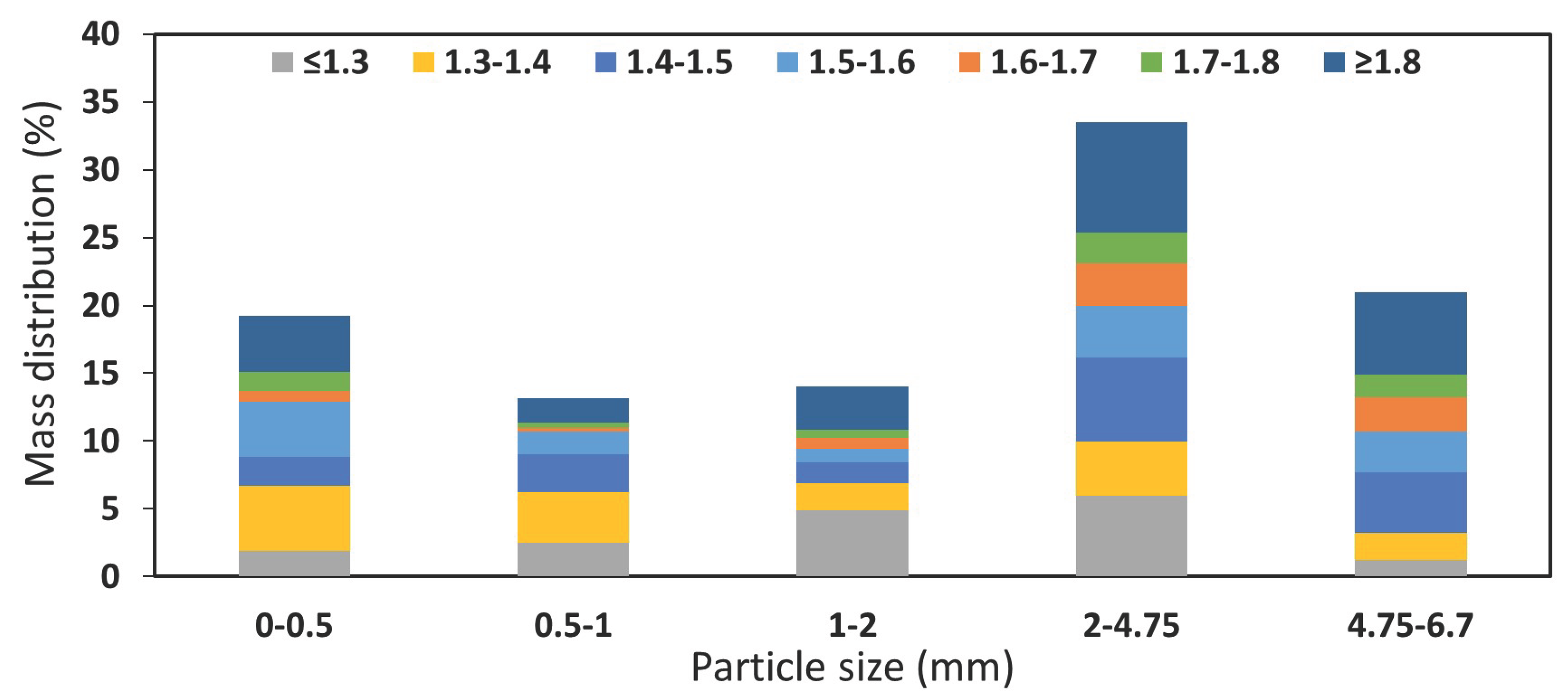

| Size (mm) | Relative density | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.3 | 1.3-1.4 | 1.4-1.5 | 1.5-1.6 | 1.6-1.7 | 1.7-1.8 | >1.8 | ||

| 53-75 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.66 | 4.53 | 0.00 | 8.19 |

| 37.5 -53 | 0.00 | 3.33 | 3.80 | 2.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.89 | 13.03 |

| 26.5-37.5 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.93 | 2.11 | 2.70 | 0.97 | 2.87 | 9.58 |

| 19-26.5 | 0.00 | 1.01 | 2.22 | 2.40 | 0.92 | 1.84 | 3.23 | 11.62 |

| 13.2-19 | 0.00 | 1.28 | 3.26 | 1.65 | 0.90 | 1.04 | 4.08 | 12.21 |

| 9.5-13.2 | 0.09 | 0.76 | 1.71 | 0.89 | 0.96 | 0.34 | 2.16 | 6.91 |

| 6.7-9.5 | 0.19 | 1.10 | 2.00 | 1.12 | 0.61 | 0.49 | 1.66 | 7.07 |

| 4.75-6.7 | 1.02 | 0.92 | 1.46 | 0.91 | 0.58 | 0.47 | 1.42 | 6.58 |

| 2-4.75 | 2.10 | 2.05 | 1.96 | 1.03 | 0.60 | 0.44 | 1.75 | 10.43 |

| 1-2 | 2.42 | 1.88 | 0.72 | 0.53 | 0.42 | 0.15 | 0.88 | 7.00 |

| 0.5-1 | 0.00 | 1.71 | 0.17 | 0.44 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.26 | 2.71 |

| 0-0.5 | 0.00 | 1.99 | 0.45 | 1.00 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.59 | 4.27 |

| Total | 5.82 | 16.03 | 18.68 | 14.09 | 11.52 | 10.47 | 22.79 | 100 |

| Density | Ash (%) | Volatile Matter (%) | Fixed Carbon (%) | Calorific Value (MJ/kg) | Total Sulphur (%) | Free Swelling Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1.3 | 4.47 | 19.19 | 76.35 | 34.18 | 0.98 | 7.5 |

| 1.3-1.4 | 12.8 | 17.48 | 69.72 | 30.67 | 0.9 | 4 |

| 1.4-1.5 | 19.72 | 16.46 | 63.82 | 28.14 | 0.9 | 2.5 |

| 1.5-1.6 | 27.05 | 15.5 | 57.45 | 25.05 | 0.82 | 1 |

| 1.6-1.7 | 35.47 | 14.33 | 50.2 | 21.94 | 0.8 | 0 |

| 1.7-1.8 | 44.26 | 13.1 | 42.64 | 18.38 | 0.86 | 0 |

| >1.8 | 59.22 | 12.93 | 24.85 | 10.64 | 1.7 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).