1. Introduction

With increased urbanization, the reliance on cars has increased, and persistent micro-pollution from car tires is inevitable [

1,

2]. Car tires possess a complex chemical composition, including polymeric material, fillers, softeners, vulcanization agents, and other additives that increase their strength, mechanical properties, and durability [

3,

4]. 4-Aminodiphenylamine (4-ADPA) is a common additive in rubber tires, known for its antioxidant properties. It plays a vital role in enhancing tire durability by preventing issues such as drying, cracking, and degradation from prolonged exposure to environmental elements like heat, oxygen, and ozone [

3,

5]. As car tires wear down because of high friction on the roadway, microscopic particles, often called tire wear particles (TWPs), are released into the atmosphere, leading to environmental pollution [

1]. A few recent studies on rubber tires and tire wear particles have identified 4-ADPA as a TWP that can have ecological & toxicological consequences. The 4-ADPA, a common antioxidant used in tire manufacturing, was found in all airborne particulate matter samples collected along a highway in Mississippi, USA [

2]. In the study of two cities in Germany, Kuntz et al. confirmed the presence of 4-ADPA in urban particulate matter aerosol [

6]. The chemical profiling and suspect screening by McMinn et.al. identified the presence of 4-ADPA in crumb rubber extracts [

7]. These studies confirm that many TWPs with varying concentrations are present in urban aerosols, which are potentially carcinogenic and genotoxic to humans [

6]. The environmental residue of 4-ADPA from tire wear is washed away by rain and released into the aquatic environment through urban wastewater runoffs. Many of these particles do not degrade and persist in the aquatic ecosystem, and even bioaccumulate in aquatic life forms, posing threats to various forms of marine life. Various environmental studies have demonstrated the toxicity of TWPs on marine life forms [

3]. The toxicological studies in aquatic organisms exhibited bioaccumulation of these compounds, and long-term exposure causes growth and developmental damage, neurotoxicity, respiratory, reproductive, and intestinal toxicity, and multi-organ failure [

8,

9,

10]. Owing to the ecotoxicological effects on aquatic organisms, TWP-derived compounds have gained increasing attention in environmental health science research.

The free-floating plants growing on the water surface are called duckweeds, comprising monocotyledonous macrophytes [

11,

12]. Among the family

Lemnaceae of this class, the

Lemna genus includes 36 species of floating plants. The species

Lemna minor (

L. minor) is probably the best known of the genus, also known as common duckweed, and is usually found in still or slow-moving waters [

13]. It is widely available in the aquatic ecosystem of Asia, Africa, Europe, and North America, including the United States and Canada [

11]. It has a simple morphology, faster growth, and reproduction rate than other vascular aquatic species [

14]. Aquatic macrophytes are of ecological significance as they are essential in nutrient cycling, sediment stabilization, oxygenation, and providing food and marine habitat. They have various applications in agriculture, pharmaceuticals, phytoremediation, and energy production, and they represent higher aquatic plants in research. The

Lemna species offers several advantages as a study model in physiological and ecotoxicological research, since they are adapted to different climatic conditions, grow rapidly, and reproduce asexually with homogeneity, are easy to maintain in laboratory cultures, and are sensitive to toxicants [

12,

15]. The developmental biomarkers, such as growth parameters and physiological biomarkers like chlorosis and pigment content, are commonly assessed in ecotoxicological studies [

16]. Studies on

L. minor have shown that it contributes to ecotoxicological research as a representative of aquatic plants, and standardized protocols for performing growth inhibition tests on this plant species have been developed [

12,

17]. It facilitates ecotoxicity tests under controlled laboratory conditions and provides measurable endpoints like frond morphology, biomass, and photosynthetic pigments such as chlorophyll and carotenoid content, making it ideal for assessing the toxicity of environmental pollutants on aquatic ecosystems [

12,

15].

Due to the adverse ecological and human health effects, TWP derivatives like 4-ADPA are recognized as emerging environmental contaminants [

2]. Despite being a pollutant of rising concern, studies on 4-ADPA and its ecotoxicity are limited. Therefore, assessing the ecotoxicological impact of 4-ADPA is important for environmental pollution monitoring and for characterizing the risks to various aquatic life forms, as TWPs are a persistent source of pollution. Among the potentially exposed aquatic species are aquatic macrophytes like

lemna. Additionally,

L. minor serves as a suitable model for assessing the toxicity of environmental pollutants due to its relatively small size, rapid growth, and ease of clonal propagation [

18].

Considering the above, the present study aimed to observe how the tire-wear-derived compound 4-ADPA influences the growth and photosynthesis of the aquatic macrophyte L. minor and evaluate its ecotoxicological impact on it.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

The Chemical standard of 4-ADPA was obtained from Cayman Chemical Company. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and electronic grade methanol were purchased from Fisher Scientific. The basal salt mixture used to prepare Hoagland media was obtained from Caisson Laboratories. Andonstar AD246SP, an HDMI Digital microscope, was used for imaging, and ImageJ software was used to count the frond number. The Ohaus AV812 Adventurer Pro digital balance was used for measuring plant biomass. A Thermo Scientific Spectronic 200 Spectrophotometer was used to quantify photosynthetic pigments.

2.2. Plant Materials and Culture Conditions

L. minor was collected initially from the Louisiana State University Lake, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and the duckweed culture was established at the Environmental Health Sciences Laboratory at Southern University and A&M College, Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The plants were grown and maintained in 100 mm x 15 mm petri dishes with approximately 50 mL of Hoagland’s culture media under controlled, continuous light exposure and normal lab temperature conditions. The total medium was renewed once a week.

2.3. Experiment Design

4-ADPA was prepared by dissolving 4-ADPA crystals in DMSO. 0.1 mg of 4-ADPA crystals were first dissolved in 1 mL of 100 % DMSO. This solution was then diluted with Hoagland's culture media to prepare a stock solution of 1 mg/L of 4-ADPA containing 1% DMSO. The test solutions were prepared by diluting this stock solution in Hoagland’s culture media to obtain the final desired 4-ADPA concentrations. The preliminary tests with L. minor were performed with a range of reported relevant environmental concentrations of 4-ADPA, and the correlation between growth parameters and photosynthetic pigments was found. After optimization, the ideal range that can effectively evaluate the desired biological response was identified for the experiment. The tested concentrations of 4-ADPA were 10 μg/L, 25 μg/L, 50 μg/L, 100 μg/L, and Hoagland’s media was used as a control treatment.

Healthy duckweed plants with 2-3 fronds from laboratory stock culture were selected as test specimens. Three

Lemna plants with three fronds were exposed in a 6-well culture plate in three replicates with a final volume of 5 mL of Hoagland’s media per well supplemented with a tested range of 4-ADPA concentrations. The test was conducted for 7-day and 14-day exposure periods under controlled temperature and continuous light exposure, based on OECD guidelines [

17]. At the end of the 7-day and 14-day experiment periods, fronds from each treatment group were collected, and relative growth rates based on fresh weight and frond number were recorded. Then, the plants were placed in Eppendorf microtubes for further analysis.

2.4. Plant Growth Determnination

The growth rate of L. minor was determined after 7 and 14 days of exposure to different concentrations of 4-ADPA under laboratory conditions. The Lemna fronds were surface dried on absorbent paper and then weighed in an analytical balance to determine fresh weight. The fronds were photographed using a digital microscope, and the frond numbers were counted using ImageJ software.

2.5. Physiological Markers Analysis

2.5.1. Photosynthetic Pigment Contents

Pigments were extracted from

L. minor fronds using 1 mL of 100% methanol per replicate, under room temperature and dark conditions, based on the protocol by Hiscox and Israelstam (1979) [

19]. After 24 hours, the absorbance of supernatants was measured at 470 nm, 652 nm, and 665 nm using a Thermo Scientific Spectronic 200 Spectrophotometer. The extraction solution was used as a blank. Photosynthetic pigments (chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll, and carotenoid) were calculated following the equations proposed by Lichtenthaler (1987), and results were expressed in milligrams per gram of fresh weight (mg/g) [

20].

Table 1.

Equations for the determination of Chlorophyll a (Ca), Chlorophyll b (Cb), Total chlo-rophyll (Ca+b), and Carotenoids in Lemna minor extracts using methanol as a solvent. The pigment concentrations were obtained by inserting the respective absorbance values in the given equation.

Table 1.

Equations for the determination of Chlorophyll a (Ca), Chlorophyll b (Cb), Total chlo-rophyll (Ca+b), and Carotenoids in Lemna minor extracts using methanol as a solvent. The pigment concentrations were obtained by inserting the respective absorbance values in the given equation.

| Pigment |

Equation |

| Ca

|

(16.72*A665.2) - (9.16*A652.4) |

| Cb

|

(34.09*A652.4) -(15.28*A665.2) |

| Ca+b

|

(1.44*A665.2) -(24.93*A652.4) |

| Carotenoids |

(1000*A470-1.63*Ca-104.96*Cb)/221 |

2.5.2. Histological Analysis for Starch Accumulation

Starch accumulation was determined following the protocol by Bourgeade et al. (2021) [

21]. The decolorized plant tissue after methanolic extraction was gently washed with water, dried, and then stained with Lugol’s solution. Relevant areas of starch accumulation were identified and recorded using an HDMI camera coupled to a light microscope.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Bonferroni post-hoc t-test was performed to analyze the significant difference between the treatment and control groups. A p-value of less than 5% (p <0.05) was considered statistically significant. Microsoft Excel was used for all statistical analyses.

4. Discussion

Lemna minor, a common duckweed, has been widely used as a study model in ecotoxicology to assess how toxic some chemicals or pollutants might be to non-target species, because of its high sensitivity to a wide range of chemicals, a short reproduction cycle, and ease of growth, maintenance, and manipulation in the laboratory [

22]. In addition, duckweeds, an integral part of the aquatic ecosystem that grow in aggregates of colonies forming large blankets across the water surface, play a key role in habitat provision, phytoremediation, and nutrient cycling, so it is also an ecologically significant species [

12,

23]. In recent years, the toxicity and hidden threats of tire wear leachates to aquatic habitats and species like coho salmon, Rainbow trout, algae,

L. minor, etc., have been studied widely [

24,

25,

26,

27]. Various types of TWPs are generated by the friction between the tire and the road surface, accounting for more than 50% of microplastics in the environment [

28]. Despite 4-ADPA being one of the tire-derived pollutants, its effects on the aquatic environment and species remain poorly understood.

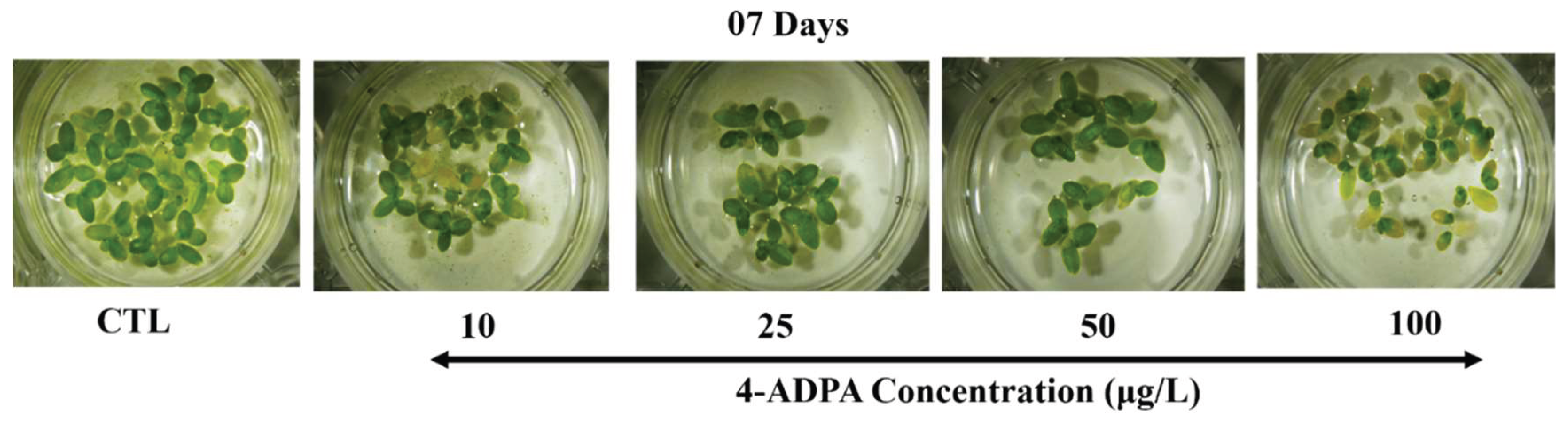

This study tested tire-derived compound 4-ADPA for its aquatic ecotoxicity using

L. minor as a study model. The 4-ADPA treatment suppressed the growth of plants, with visible chlorosis and disintegrating fronds in the exposed

L. minor plants (

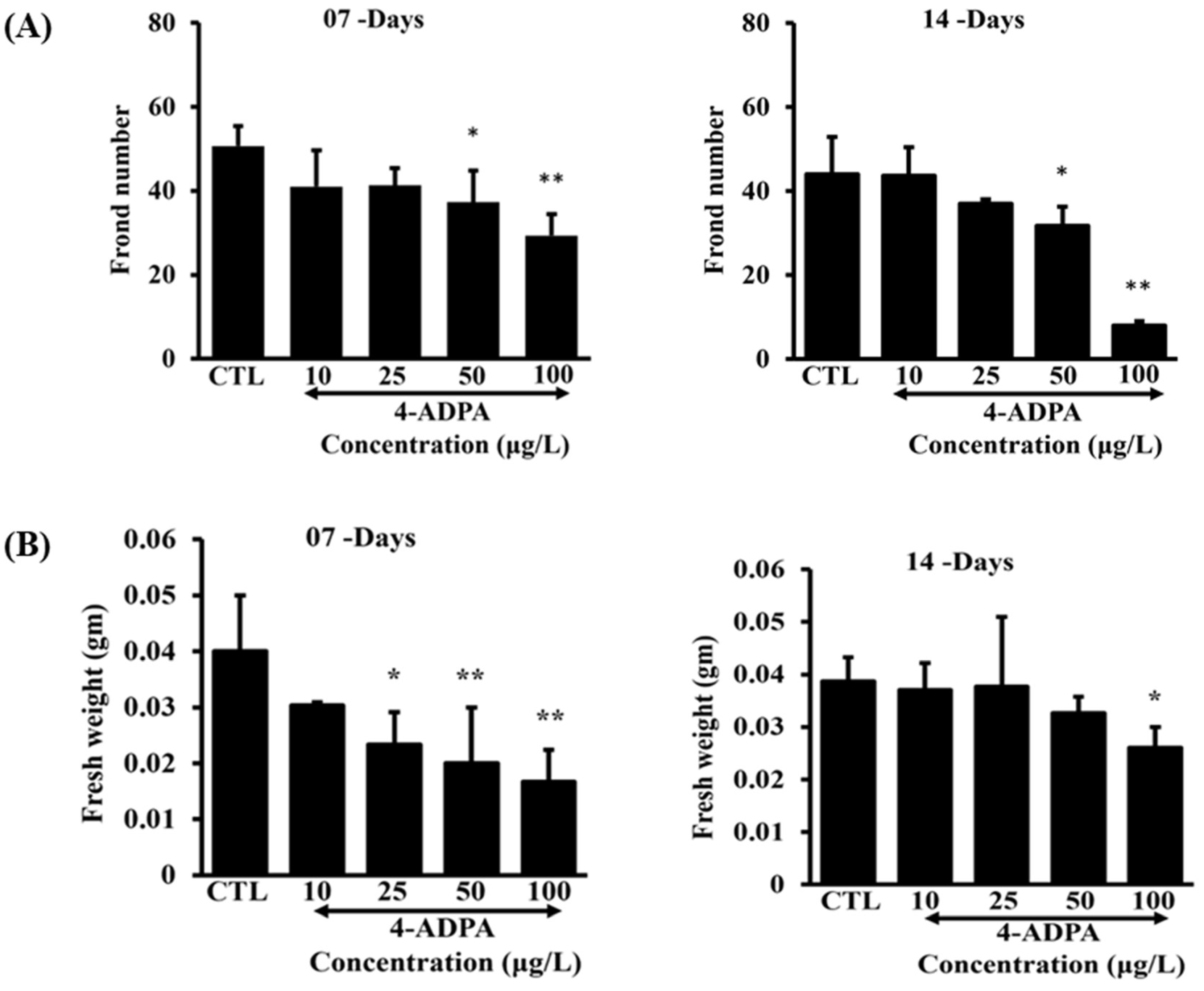

Figure 1). The number of fronds also substantially decreased in a dose-dependent manner following 4-ADPA exposure (

Figure 2A). Fresh biomass was reduced by more than 50% after seven days of exposure (

Figure 2B). By day 14, fresh weight increased compared to day seven of the experiment, suggesting the plant's potential adaptation and tolerance over time; however, a dose-dependent reduction was still evident across the treatment groups [

29] (

Figure 2B). The growth-related parameters of this study align with findings reported by Dumont et al., where chlorosis and a significant decrease in growth based on frond number and dry weight were observed following exposure to TWP leachates [

30]. Chlorosis is the progression from green-colored fronds to pale, yellow fronds. It is attributed to reduced chloroplast density per cell and chlorophyll content due to nutrient deficiency, oxidative stress, bacterial or fungal infestations, chemical exposure, pollution, etc. [

23]. Chlorosis affects photosynthetic efficacy, leading to a decreased ability of plants to synthesize carbohydrates and produce energy. This can result in stunted growth, detachment of some fronds, and plant death [

23].

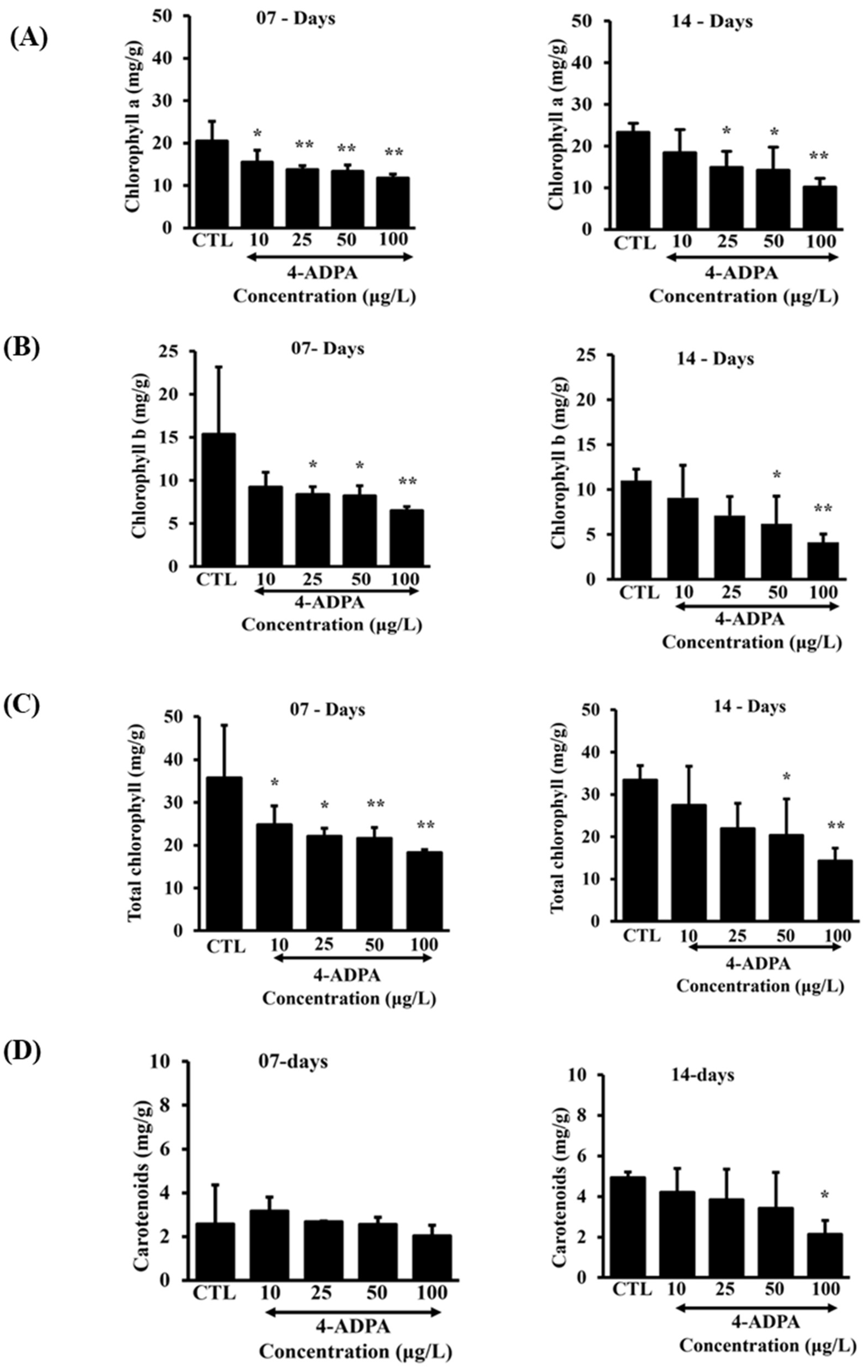

Not only was the plant's growth affected after 4-ADPA treatment, but a similar pattern was observed with the photosynthetic pigment’s analysis. The decline in growth-related parameters correlated closely with the physiological biomarkers like chlorophyll and carotenoid contents in

L. minor exposed to 4-ADPA. In our study, the dose-dependent reduction in pigments like chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and total chlorophyll b was observed (

Figure 3). A similar outcome was also observed in the ecotoxicological studies by Radic et.al [

29] and Kumar et.al [

30], which supports our findings. Chlorophyll is a pigment within the plant's chloroplast, giving plants a characteristic green color. The amount of chlorophyll in leaf tissue is affected by nutrient deficiency and environmental conditions like pollutants, temperature, drought, etc. Plants have two types of chlorophyll pigment, chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b, which play a unique role in the physiology and productivity of green plants. Therefore, estimating chlorophyll contents has been of special interest in assessing physiological processes and plant health. Chlorophyll a is a bluish-green pigment and a primary pigment that converts light energy into chemical energy during photosynthesis. It is about three times more abundant than chlorophyll b in plant tissue. Chlorophyll b is an accessory, yellowish green pigment that helps to absorb light energy at different wavelengths and transfer it to chlorophyll a. Total chlorophyll is simply the sum of chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b [

31,

32]. Carotenoids are essential pigments of terpenoid groups crucial to photosynthesis, phytoprotection, and structural stabilization of photosynthetic complexes [

23,

33]. The carotenoid content was not significantly affected after 7 days of 4-ADPA exposure. However, after 14 days, the carotenoid content progressively declined with increased 4-ADPA exposure. In our study, the effects of 4-ADPA on carotenoid content were less apparent compared to those of chlorophylls, consistent with the findings by Radic et al. [

29]

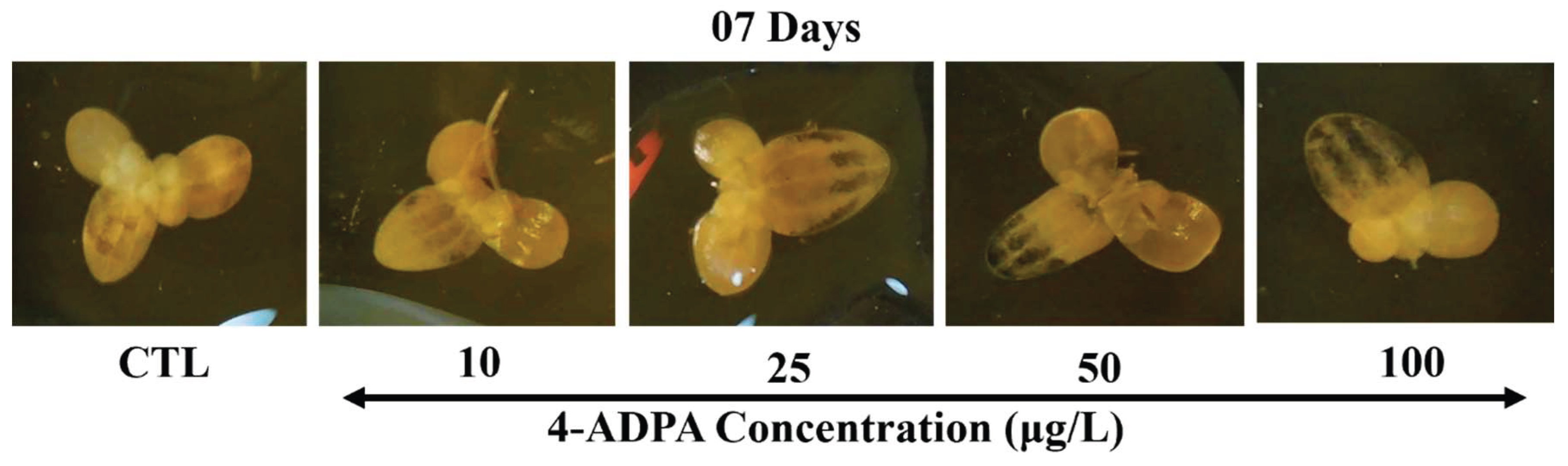

The Lugol staining revealed increased starch accumulation with increased 4-ADPA concentration, which aligns with the results reported by Sree et. al [

34]. In this method, the iodine in Lugol’s solution reacts with starch, making the intracellular starch visible and producing a dark coloration [

22]. Starch forms a helical structure of its monomer glucose, and the iodine from Lugol’s solution gets trapped in the glucose helix, thus producing purple-black-colored areas [

35]. The decreased chlorophyll content with increased 4-ADPA treatment reflected impaired photosynthesis and decreased carbohydrate synthesis. However, increased starch accumulation with a higher concentration of 4-ADPA was detected with Lugol’s staining. This is attributed to the stress the plants are under. Environmental conditions, like pollutants, can cause stressed conditions in plants, leading to less carbohydrate being used for growth, and the excess being stored as starch [

34,

36].

This study adds to our understanding of how TWPs disrupt the aquatic ecosystem. The observed chlorosis with stunted growth, reduced photosynthetic pigments and increased starch accumulation with increased concentrations of 4-ADPA exposure negatively affect photosynthetic efficiency in plants and can be linked to various stress conditions [

23,

36]. The reduced growth and physiological biomarkers with increased 4-ADPA treatment demonstrate the ecotoxicological effects of 4-ADPA on

L. minor; however, our study focuses on only one species, which may not represent the effects on other marine habitats. Therefore, future studies with additional model species like zebrafish, coho salmon,

Caenorhabditis elegans, etc., are suggested for a broader understanding of the ecological impact of 4-ADPA.