1. Introduction

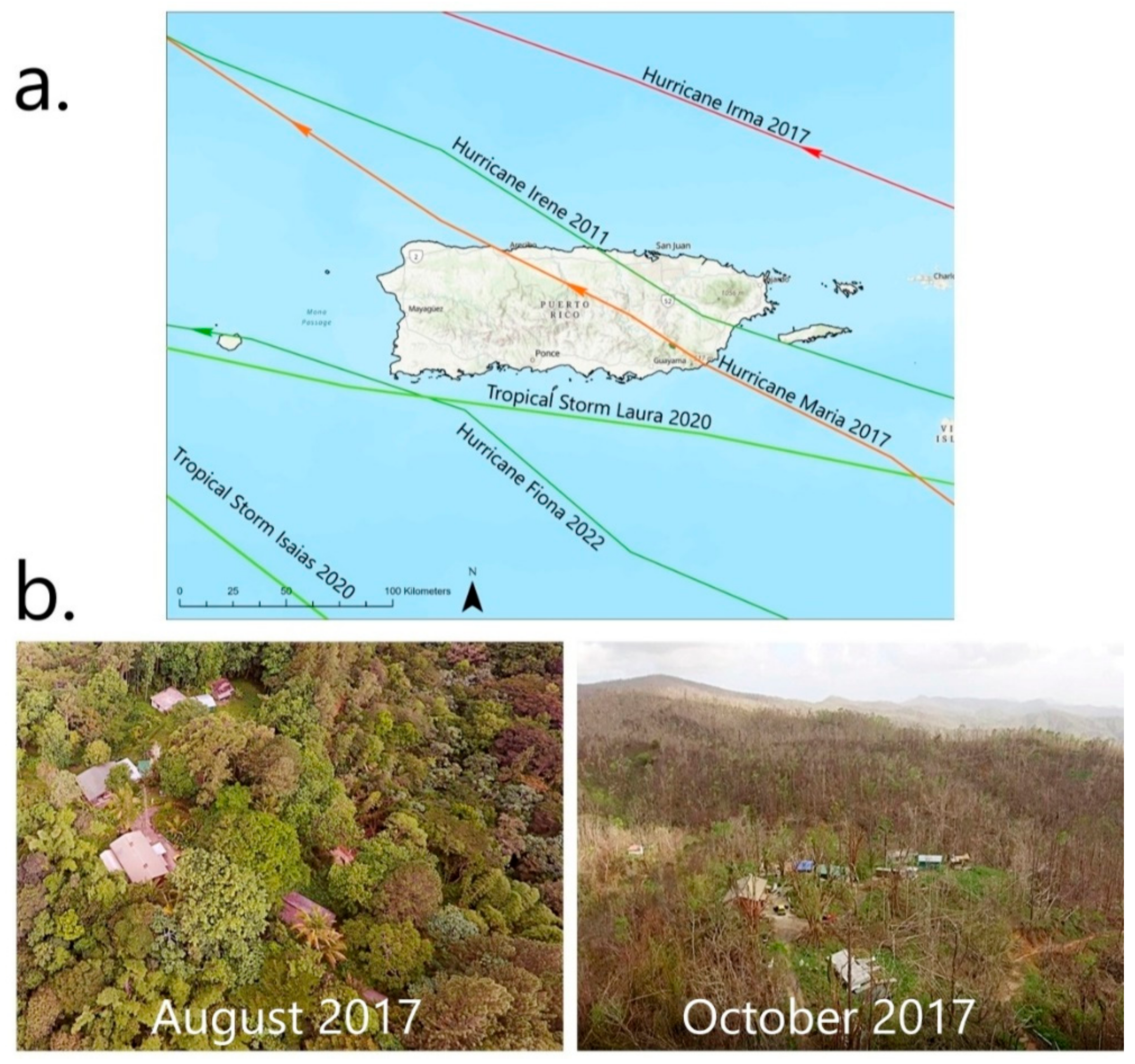

Hurricanes are severe weather events that are common throughout the Caribbean. As these storms make landfall, they result in extremely dangerous winds, torrential rain, strong storm surges, and coastal flooding. The island of Puerto Rico is frequently in the path of these powerful storms which are expected to increase in intensity due to warming ocean surface temperatures [

1,

2,

3], rapidly intensify more frequently [

4,

5], and produce more extreme rainfall [

6,

7,

8] as a result of climate change. The most recent and most powerful hurricane to impact the island since 1928 was Hurricane Maria in 2017. Hurricane Maria made landfall in Puerto Rico on September 20, 2017 as a strong upper category 4 storm with winds up to 241 kph and causing up to

$90 billion in damage [

9]. As Maria made landfall, it crippled the island’s power grid [

10], cut off access to clean water supplies [

11] and caused substantial damage to the forest [

12,

13,

14,

15].

Extensive research on how hurricane disturbances affect tropical forests really kicked off following the aftermath of Hurricane Hugo in 1989, with much of the research being conducted within the Luquillo Experimental Forest in Puerto Rico [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Following a hurricane, trees are damaged from the loss of leaves (defoliation), damage to small branches, breaking of larger branches, and the snapping and uprooting of tree stems [

26]. There are numerous factors involved that can contribute to the severity of forest damage which includes topography of the land [

14,

25,

26], land use history [

27,

28], forest fragmentation [

29], tree size [

18], tree species [

20,

30,

31], distance from the storm [

13,

14], and intensity of the storm [

15,

32]. A recent study conducted by Uriarte et al. 2019 compared hurricane-induced forest damage caused between hurricanes Hugo (1989, category 3), Georges (1998, category 3), and Maria (2017, category 4) in the Luquillo Experimental Forest in Puerto Rico. They found that Hurricane Maria had killed twice as many trees and had broken up to 2- to 12-fold more stems compared to the other storms [

15]. Taller trees with larger diameters at breast height (dbh) have also been shown to be more vulnerable to snapping or uprooting when compared to shorter trees [

18].

While the damage to the forest following a hurricane gives the appearance of significant mortality, the actual mortality of trees in the forest is quite low (4-8% recorded by previous studies in the Caribbean [

26,

33]) and much of the forest will recover and quickly reestablish new leaves with some species obtaining new leaves as early as two weeks post-hurricane [

14,

18,

26]. In general, studies have shown that the forests of eastern Puerto Rico and the Caribbean are quite resilient to a wide variety of disturbances whether natural or anthropogenic [

23,

24] and that hurricanes play important roles in forest community dynamics such as increasing spatial heterogeneity, resetting successional patterns and nutrient flows, altering species composition, and inducing longer-term evolutionary change [

21,

34,

35].

While most of the previous work has focused on natural forests, plantation forestry has played an important role in many parts of the Caribbean [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. There is much less published research on hurricane impacts in plantation forests, and findings suggest that patterns of damage and recovery vary depending on the tree species. For example, pine trees favored in plantations typically do not resprout or regrow if the main stem is broken or uprooted, unlike many species in natural tropical forests [

18,

20,

26,

41,

42]. Monoculture plantations differ from natural forests in vertical structure especially in terms of understory vegetation, which may make them more vulnerable to stronger damage from wind [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. Sustainable forestry practices can differ from monocultures in several ways: they are not based on clear-cutting the existing forest to make space for planting the preferred species; more than one species of trees may be planted, interspersed with the existing vegetation; the understory may be retained thereby maintaining a more complex vertical structure to the forest than in monocultures. More research is needed to understand the impacts of hurricanes in such plantations to better inform sustainable management of economically valuable forests.

In this study, we focused on measuring hurricane damage and assessing recovery seven years post-Maria in a sustainable multi-species forestry plantation site at a property called Las Casas de la Selva in southeastern Puerto Rico. Using a combination of 360° photography and virtual reality to analyze forest vertical structure and ground cover and canopy closure across 75 sites, we compared sites that took severe damage to sites that took light and moderate damage to determine whether there were long-term differences between forest vertical structure, ground cover and canopy closure. Our overall scientific goal was to learn more about the long-term impacts a major Hurricane such as Maria can have on a subtropical wet plantation forest in Puerto Rico.

Our overarching questions are:

How does forest vertical structure, groundcover, and canopy closure at sites with significant damage compare to sites with light/moderate damage seven years later?

How does the underlying topography (elevation, slope, aspect) in this mountainous region influence the amount of damage to the forest (canopy closure, vertical structure, and groundcover) on the property?

2. Study Area

Las Casas de la Selva is a property that was established in 1983 in Patillas, Puerto Rico as an experimental sustainable forestry and rainforest enrichment project. The Institute of Ecotechnics started this project to develop science-driven methods to grow commercially valuable timber species while also helping the regeneration of naturally occurring species in a mixed plantation forest. The goal was to both get a better understanding of sustainable practices for managing such mixed plantations and to demonstrate the value of such an approach to private landowners. The property consists of 409 hectares of tabonuco forest which is located along very steep slopes at an average elevation of 600 meters (range 508-607m) and receives an average annual rainfall of ~3,000 mm [

36,

47].

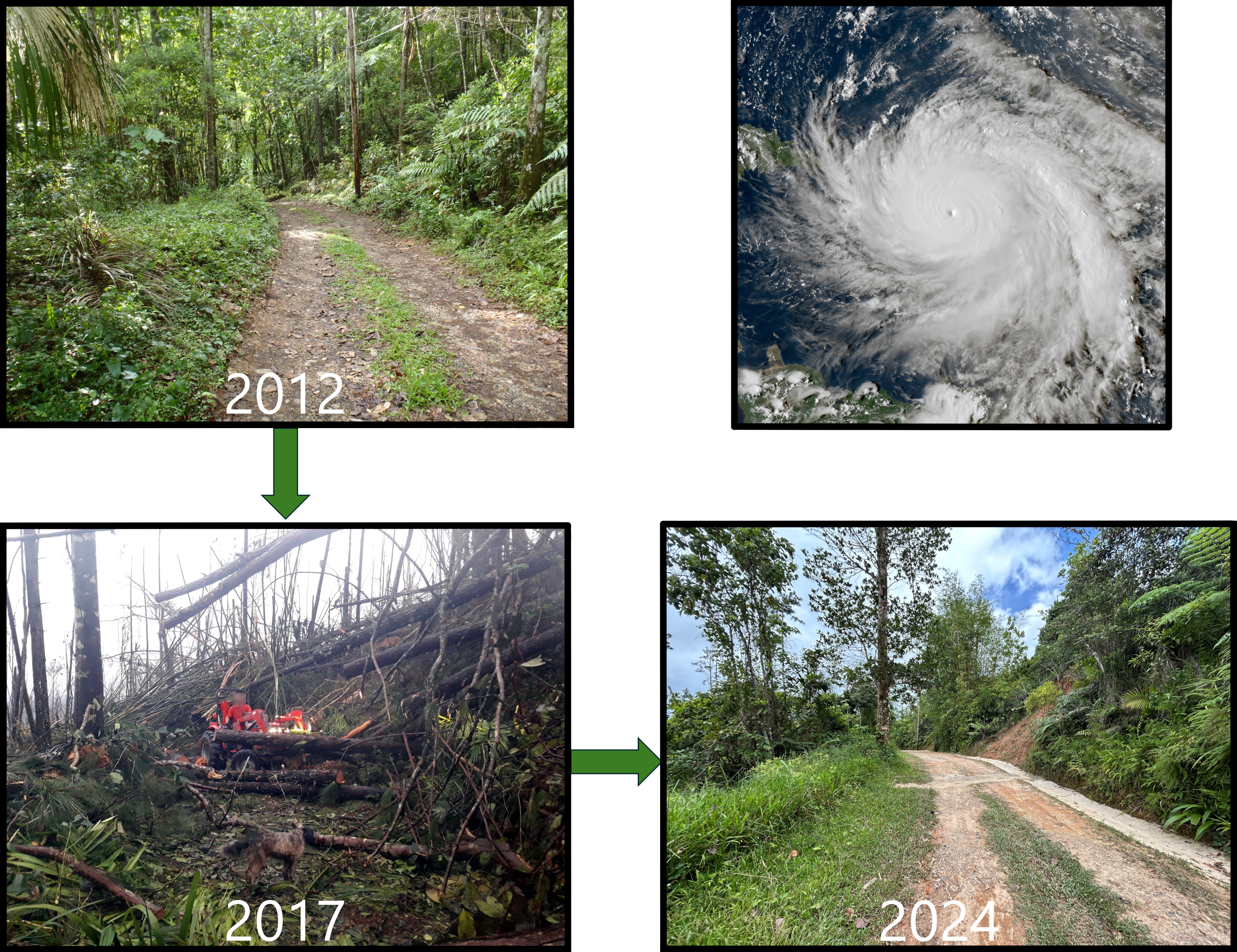

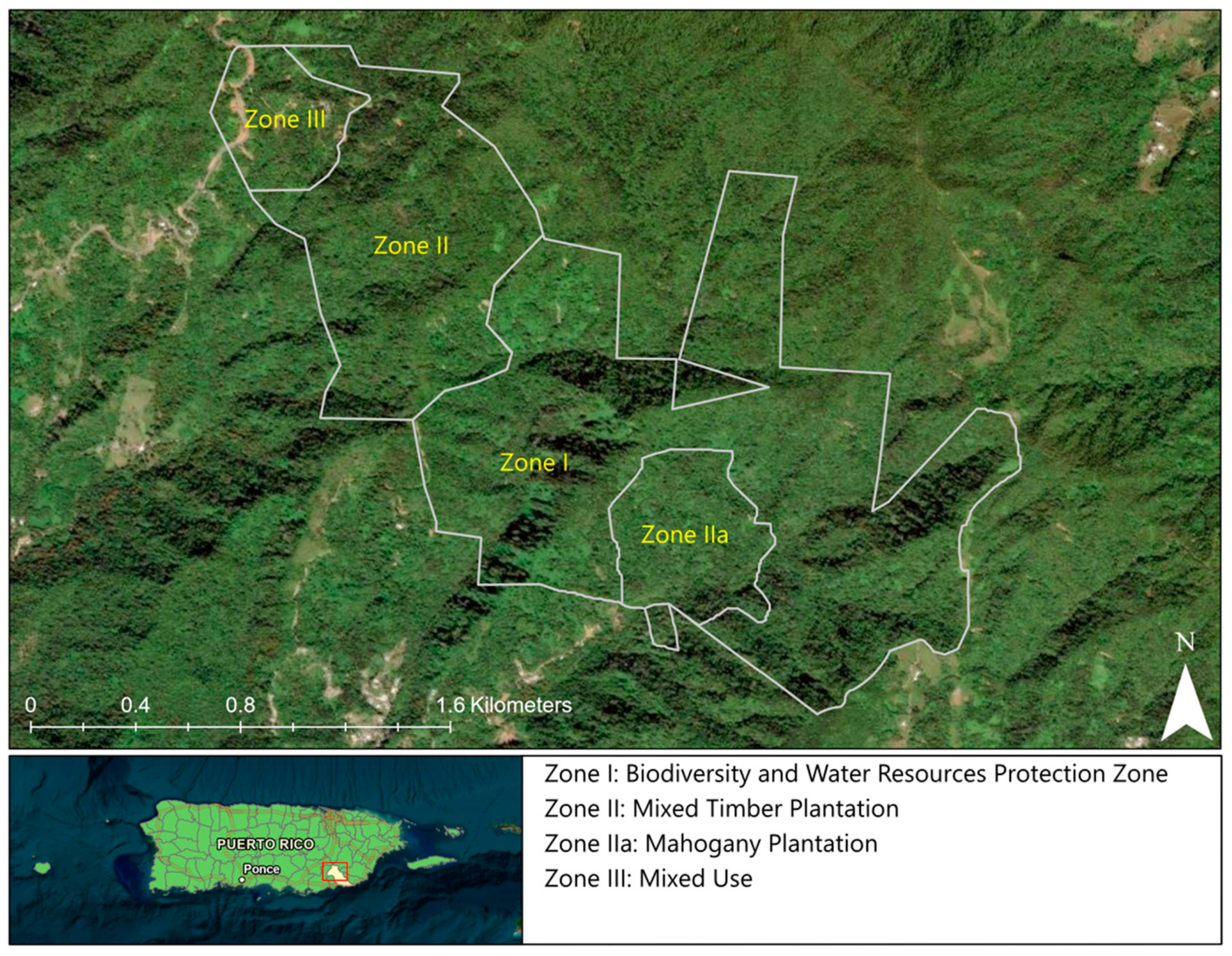

The forest on the property is a mature second-growth forest and is classified as subtropical wet forest on the Holdridge Life Zone classification system [

48]. Our study site consists of four zones on the property, of which zones II and III were utilized for our research (

Figure 1). Zones I and IIa occupy harsher terrain and have become much more difficult to access following landslides and other damage from Hurricane Maria. Zone II is a mixed timber plantation consisting of Mahogany (

Swietenia macrophylla x S. mahagoni) and Blue Mahoe (

Talipariti elatum) and zone III is classified as mixed use consisting of both forest, trails, and human built structures. When Hurricane Maria made landfall in Puerto Rico on September 20, 2017, it made a direct hit on the property causing extensive damage. Hundreds of trees were lost, many branches were broken, and much of the forest was completely defoliated (

Figure 2). Even today, seven years after Hurricane Maria, the damage caused can still be seen throughout the property and it is hard to miss for those who have visited before (

Figure 3).

3. Materials and Methods

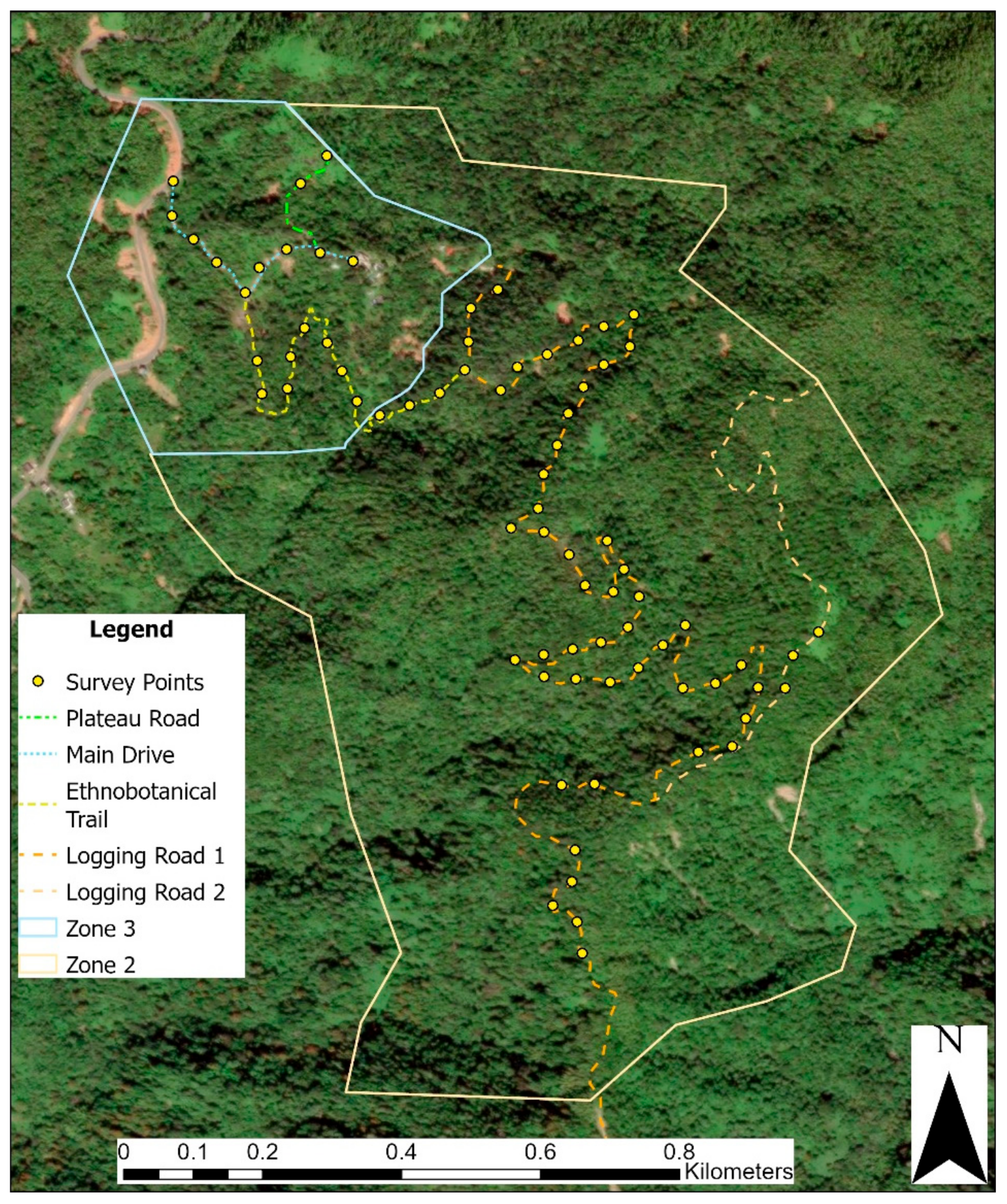

3.1. Establishing Survey Points

Prior to fieldwork, we established a total of 99 survey points randomly located across the study area on the map using ArcGIS Pro version 3.0.0. However, during a pilot test run at the property, we found reaching most of them to be unfeasible due to extreme terrain and the density of vegetation from secondary growth following Maria. Forced us to change our sampling strategy, we therefore established 75 survey points along existing trails at 40-meter interval distances (

Figure 4). We chose the 40-meter distance to minimize any overlap in the 360° photos between adjacent sites.

3.2. 360° Photography and Assigning Damage Ranks

The fieldwork was conducted entirely by the first author, Michael Caslin. To reach each survey point, Michael utilized a Garmin GPSMAP 65s unit (

Figure 5) in the field. Once arriving at a survey point, he attached the Ricoh Theta V 360° camera (

Figure 6) to a 5-foot smallrig tripod to reduce blur and to stabilize the camera and then took several photos. He assigned a damage rank to each survey point by counting the total number of remaining dead and recovering trees using the following key: (1) Light damage <= 10 dead and recovering trees, (2) Moderate damage > 10 and <= 25 dead and recovering trees, and (3) Severe damage >25 dead and recovering trees.

3.3. Data Analysis of 360° and Hemispherical Photos:

3.3.1. Estimating Forest Vertical Structure of 360° Photos through Virtual Reality

Forest vertical structure is often referred to as the “vertical stratification or layering of forest communities in space…” which is an essential characteristic for plant communities [

49] (p. 1). To estimate forest vertical structure, each 360° photo was analyzed within the Oculus Go Virtual Reality headset (

Figure 7). For each photo, Caslin determined the presence of four layers which include: (1) Herbaceous Layer, (2) Shrub Layer, (3) Understory Layer, and (4) Canopy Layer. The different layers were primarily determined by the height of the vegetation. The herbaceous layer consisted of vegetation that had no woody stems which included grass, ferns, and vines. For the herbaceous layer, the height ranged from 0.15 to 1.3 meters. The shrub layer consisted of plants with woody stems such as shrubs and small trees. This layer’s height ranged from 1.3 to 4.3 meters. The understory layer consists of vegetation in a wooded area where shrubs and trees are growing between the forest canopy and forest floor. In this layer the height ranged from 4.3 meters up to just below the canopy. Finally, the canopy layer consists of the top layer of a forest which makes up the crowns of all the trees that overlap to form the roof over the rest of the forest.

To determine the presence of these layers within the VR headset, Caslin first selected a landmark location (e.g., a tree or landscape feature). Next, turning clockwise, he recorded the presence of foliage in each of the 4 layers within 30° slices of the 360° view to capture the entire image (

Figure 8). Throughout the analysis for each photo, the PI recorded himself and then listened to the recording later to enter the data within a spreadsheet. Following Bai’s (2024) method, we calculated a Vertical Habitat Diversity Index (VHDI) by applying the Shannon-Weiner Index to these data, using layer for “species” and frequency of each layer as “abundance”.

3.3.2. Analysis of Ground Cover Vegetation

Many of the sampling locations featured a dense growth of vegetation covering up much of the ground. The ground cover consisted of the ground itself ranging from bare ground (dirt/soil) to leaf litter, rocks, and gravel as well as the types of low growing plants that are commonly found throughout the forest floor which can range from low-growing plants such as grass and ferns up to small trees. The higher growing trees were also accounted for when our sampling points were overlaid on top of them. We grouped the ground cover into eight categories: (1) Trees (2) small trees/saplings, (3) shrubs, (4) ferns, (5) bamboo, (6) vines, (7) herbaceous (specifically grass), and (8) bare ground/leaves/rock/gravel.

To analyze the ground cover, we transformed each 360° photo into hemispherical photos focusing on the ground, using GIMP version 2.10.12. We batch processed images within GIMP using an additional plugin called BIMP (Batch Image Manipulation Plugin). Next, we created a systematic point sampling grid utilizing Krita version 5.2.6. A total of 51 sample points were overlaid on each hemispherical photo (

Figure 9). The ground cover type was then determined at each of the 51 systematic point locations in each photo. Finally, we investigated three ground cover classes that would most likely be associated with hurricane disturbance in JMP Pro 16 which included (1) grass/herbaceous, (2) ferns, and (3) ground/leaves/rocks/gravel. However, before doing this, we first had to transform the ferns and ground/leaves/rocks/gravel class data using the Johnson and Box-Cox transformation methods to meet the assumption of normality.

3.3.3. Analysis of Forest Canopy Closure

Within the field of forestry, “canopy cover is the area of the ground covered by a vertical projection of the canopy, while canopy closure is the proportion of the sky hemisphere obscured by vegetation when viewed from a single point” [

50] (p. 59). To measure canopy closure, we again transformed the 75 360° photos into hemispherical images pointing up rather than down, i.e., only focusing on the canopy and excluding the ground. Each photo was then separately analyzed utilizing the % Cover app (

Figure 10). The % Cover app is an environmental application that was designed to be used on iOS devices and provides a direct estimate of canopy closure.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

We carried out all statistical analyses to test our hypotheses about how much influence elevation, damage rank, slope, and aspect had on canopy closure, vertical structure, and groundcover, utilizing JMP Pro version 16 (SAS Institute). We used ANOVA and Logistic Regression to analyze the data.

4. Results

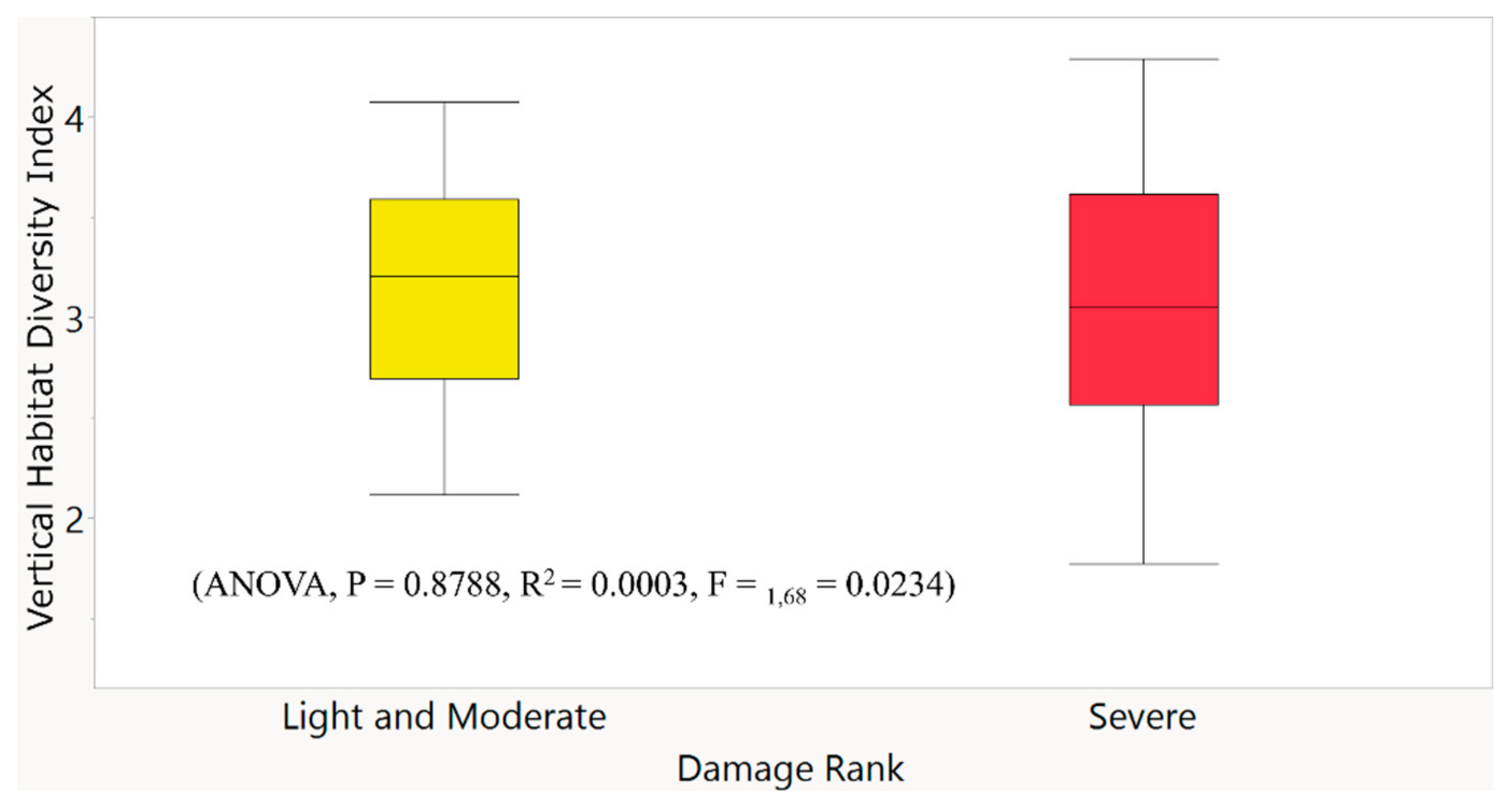

4.1. Forest Vertical Structure (Vertical Habitat Diversity Index) Did Not Vary with Damage Rank:

We found no significant difference in the VHDI (Johnson/Box Cox transformed to meet ANOVA assumptions of normality) between damage rank categories (

Figure 11; ANOVA,

P = 0.8788,

R2 = 0.0003,

F =

1,68 = 0.0234).

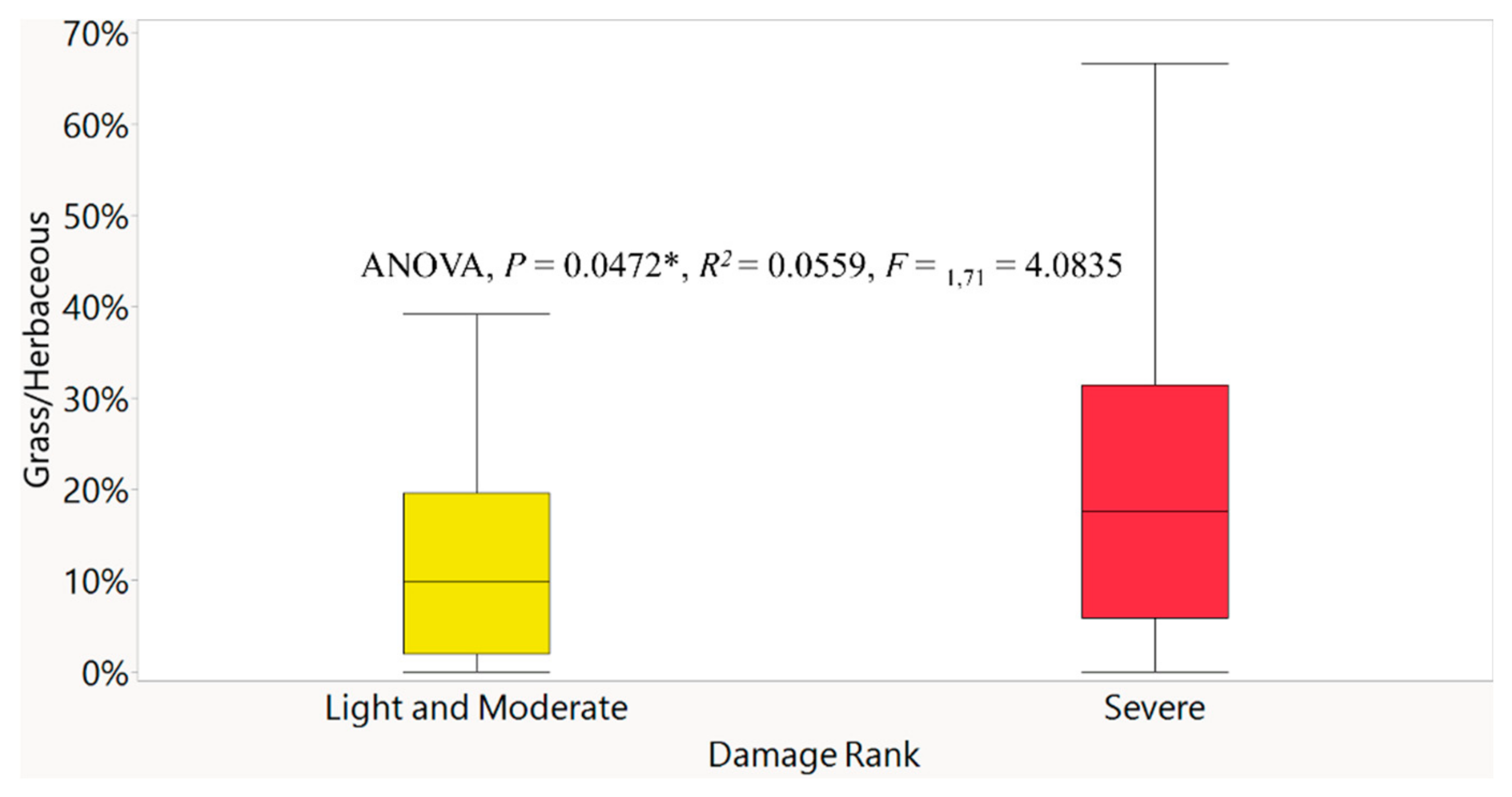

4.2. Grass/Herbaceous Ground Cover is higher at Severely Impacted Sites:

We found there to be a greater amount of Grass/Herbaceous Ground Cover at the more severely impacted sites than at the light/moderately impacted sites seven years after Hurricane Maria (

Figure 12, ANOVA,

P = 0.0472,

R2 = 0.0559,

F =

1,71 = 4.0835). None of the other ground cover variables showed significant variation among the damage rank categories.

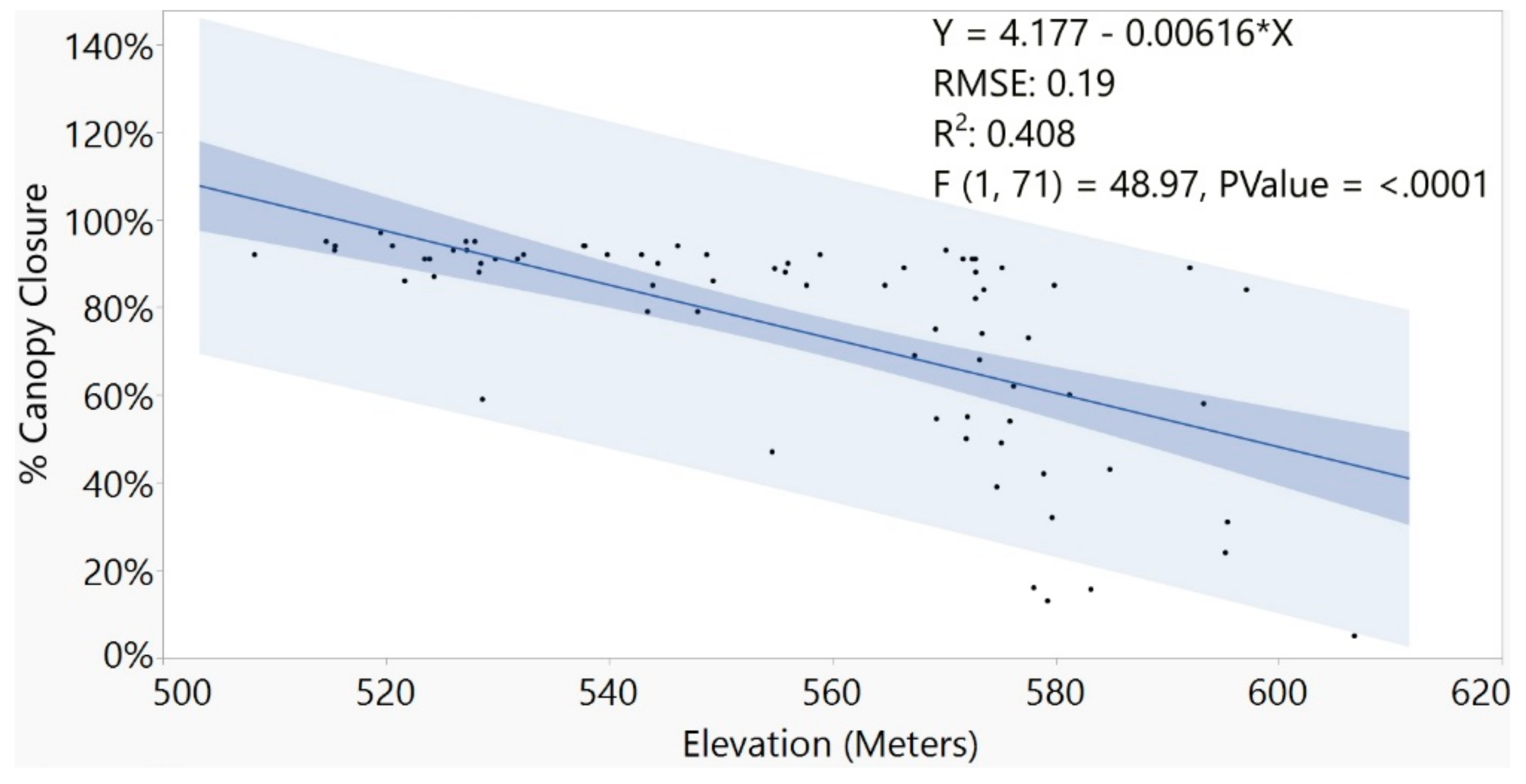

4.3. Canopy Closure is Lower at Higher Elevations:

We found that seven years after Hurricane Maria made landfall, there remains a significant pattern of decreasing canopy closure (%) with increasing elevation (

Figure 13; ANOVA,

P = < .0001,

R2 = 0.408,

F1,71 = 48.97).

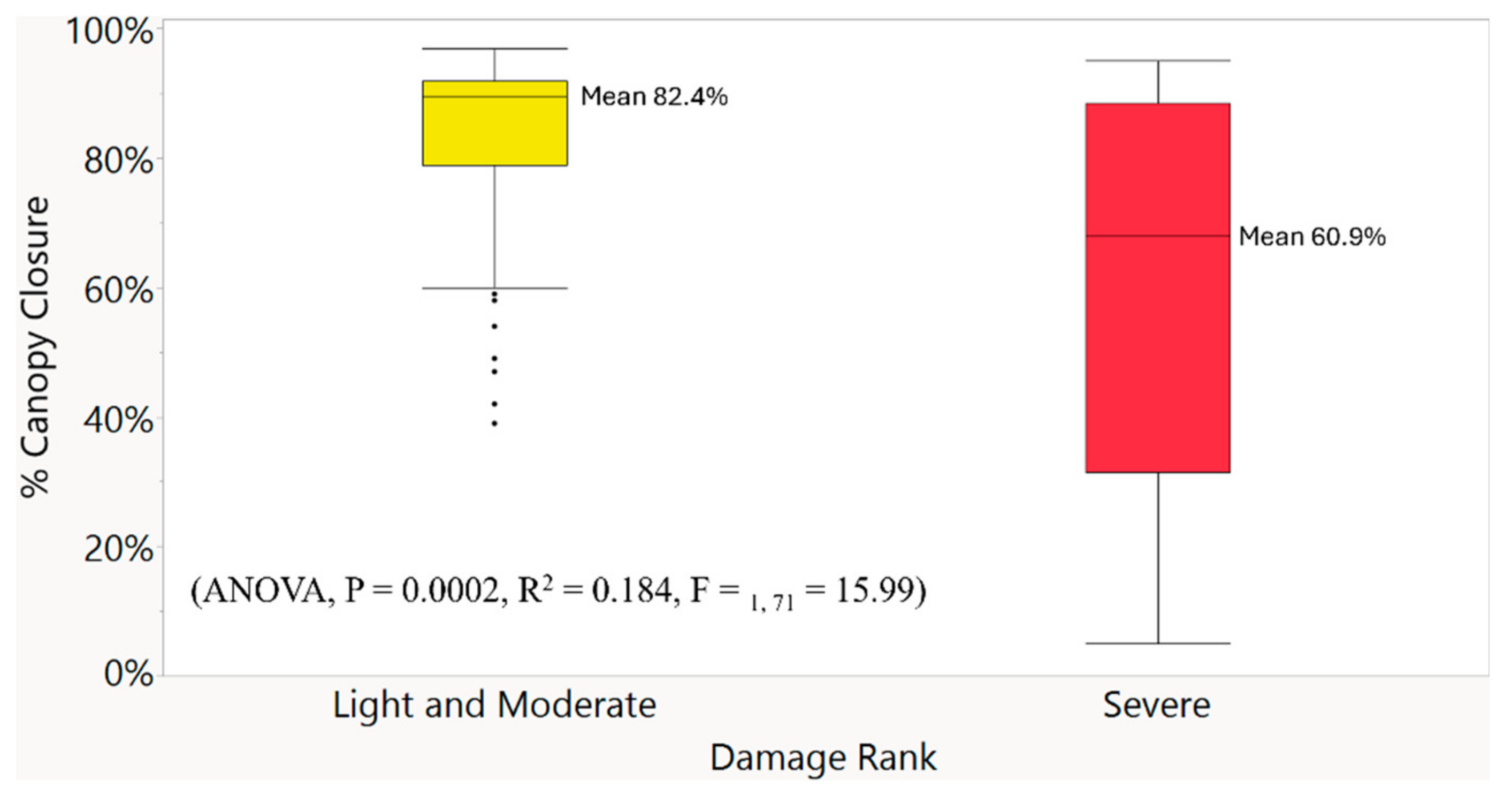

4.4. Canopy Closure is Lower at Severely Impacted Sites

We found a significant difference in percent canopy closure among damage rank categories seven years after Maria (

Figure 14; ANOVA,

P = 0.0002,

R2 = 0.184,

F =

1, 71 = 15.99) with a lower canopy closure associated with more severely impacted sites (Mean = 60.9%) and a higher canopy closure at light and moderately impacted sites (mean = 82.4%).

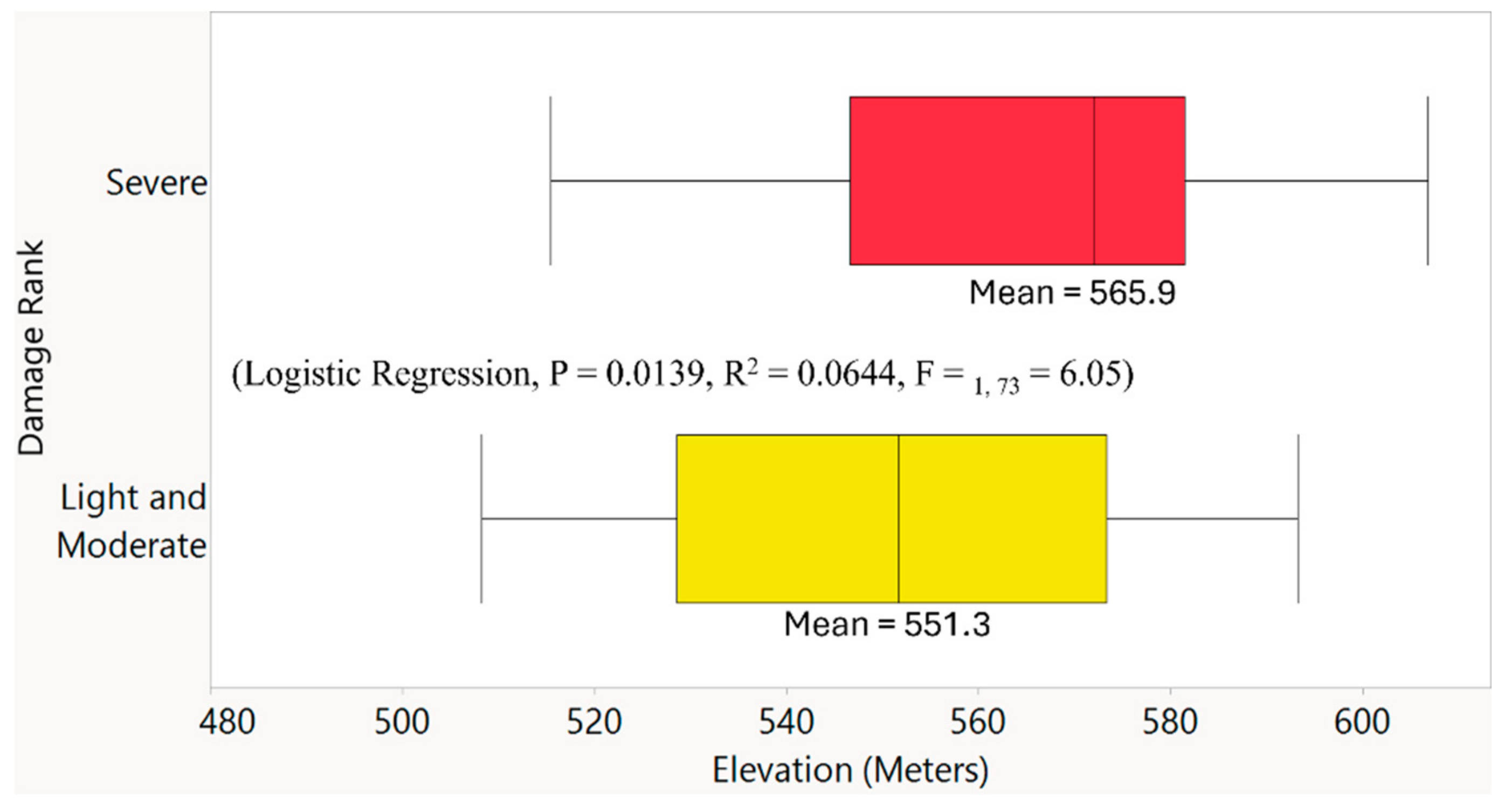

4.5. Damage Rank Is More Severe at Higher Elevations:

Seven years after Maria, we found that higher elevations were associated with more severe damage causing more dead and recovering trees (

Figure 15; Logistic Regression P = 0.0139, R

2 = 0.0644, F =

1, 73 = 6.05). However, it should be noted that this result is only applicable for the Tabonuco forest found on the island of Puerto Rico and does not account for other types of forest on the island.

5. Discussion

In this study, we investigated Hurricane Maria’s long-term impact on the forest at Las Casas de la Selva at the landscape level. We were specifically interested in determining whether there were any noticeable long-term effects on multiple components of the forest from the canopy down to the ground cover on the forest floor.

There have been many scientific studies investigating the impacts of hurricanes on forests in the Caribbean which includes the immediate damage from the storm [

15,

19,

26,

34,

51] to short-term and long-term recovery [

16,

17,

21] to forest resilience [

23,

24]. However, much of the information we have gained from previous studies has been on hurricanes of categories 3 and lower and thus does not account for a changing climate where hurricanes like Maria are expected to become more common [

1,

5]. One study conducted by Uriarte et al. 2019 has shown that Maria (category 4) caused substantially more damage to the forest compared to two strong category 3 storms in Puerto Rico. Considering this, one important question is whether the resilience of the forest to hurricanes can be maintained as these storms become more severe, more common, and cause even more damage [

15].

When Hurricane Maria made landfall in Puerto Rico, it made a direct hit on the property of Las Casas de la Selva. According to Thrity Vakil (personal communication), the director of the Tropic Ventures Sustainable Forestry & Rainforest Enrichment Project in Puerto Rico, hundreds of trees were lost. In addition, based on observations made by Thrity, the damage caused to the forest on the property was entirely by the wind and she estimates that around 80% of the planted Caribbean Pine and 50% of the planted Blue Mahoe were lost. This indicates considerably higher mortality than the 4-8% reported in previous studies of hurricane impacts in the Caribbean [

26,

33]. She also observed major delays in the production of new leaves for severely impacted trees at higher elevations which lines up with personal observations made by Brokaw and Walker in 1991. However, some of the trees took much longer to regain foliage, like some mahogany trees taking up to three years to exhibit new leaves.

5.1. More Severe Damage at Higher Elevations

The relationship between elevation and greater hurricane damage to the forest has been well documented [

13,

14,

25,

26,

31,

52,

53,

54,

55]. However, there is an inconsistency as to whether hurricane-induced forest damage is worse at higher elevations [

13,

25,

52,

54,

55] or lower elevations [

14,

31,

53]. This is because the interaction between the forest and hurricane is complex with many factors needing to be considered such as differences in forest type and forest composition, storm intensity, storm proximity, elevation, slope, tree species, soil types, and previous land use history.

For our research, we found there to be a statistically significant pattern of the forest canopy closure being lower at higher elevations (P = <.0001) seven years after the hurricane. This means that the canopy of the mixed Tabonuco/Plantation Forest is much more vulnerable at higher elevations at our study site. This result makes sense considering how many trees were lost as well as taking much longer to regain new leaves at higher elevations on the property. In addition, based on personal observations made by the first author during the past (2012 and 2014) and recent (2022 and 2024) visits to the property, many areas of the property at higher elevations were completely transformed (

Figure 16). There were sections of the property that were once densely forested to where little sun reached the forest floor. Now, these once densely forested areas are completely opened up and have remained that way to this day.

One important finding from our research is that during extremely intense storms like Maria, it only takes a small difference in elevation to make the mixed Tabonuco/Plantation Forest more susceptible to major damage. In our study, the mean elevation for the severely impacted sites was 565.9 meters whereas the mean elevation for the light/moderate sites was 551.3 meters. In other words, a mean difference of 14.6 meters in elevation made a significant difference for a site to show more or less severe damage.

However, elevation alone is not the sole predictor of damage. We believe additional factors in combination with elevation have contributed to the overall severity of damage found on the property. These additional factors include the proximity of Maria’s storm path (the eye passed very close to our study site), the category of the storm (upper category 4), and previous agricultural land use that resulted in major erosion throughout parts of the property. This result suggests that there can be major implications for plantations established at higher elevations from more intense storms and that careful consideration must be made before the establishment of new plantations. More research is needed to better understand what the implications to the plantation forest are due to proximity of the storm path, intensity, and previous land use.

5.2. Lower Canopy Closure at More Severely Damaged Sites

We also found that even seven years post-Maria, there remains a statistically significant pattern of lower canopy closure being associated with the more severely impacted sites (P = 0.0002). The average canopy closure at the more severely impacted sites on the property is 60.9% which is 21.5% lower than the average canopy closure found at the light and moderate impacted sites (82.4%). This indicates that much of the canopy at less and moderately impacted sites have recovered whereas much of the canopy at the more severely impacted sites are still recovering seven years post-storm. This makes sense considering how many trees were lost in these areas and it will take a number of years for more trees and new branches to regrow and fill in the gaps within the canopy.

5.3. Persistent Lack of Woody Plant Regeneration at Severely Damaged Sites

For groundcover, we were interested in whether specific groundcover types were more common in the severely impacted category given certain types of vegetation are often frequently found in areas associated with disturbance. In this study, we only found the Grass/Herbaceous ground cover to have higher concentrations at sites that had greater damage. This suggests a relative lack of woody plant regeneration in areas that had the most severe impact that has remained persistent even seven years post-Maria. Possible reasons for this include erosion of soil due to the hurricane with likely subsequent effects on soil nutrients, as well as more direct sunlight limiting the growth of shade-dependent woody plant species. More detailed understanding of this will require further research, but this also suggests the need for greater management attention to areas with severe canopy damage in order to foster the regeneration of trees to restore the forest canopy.

5.4. Similar Recovery of Vertical Forest Structure Across Sites

Finally, we found there to be no difference in vertical forest structure (VHDI) between differing in severity of damage (P = 0.8788) which indicates that these four components of the forest have recovered by the time fieldwork was conducted in July of 2024. This surprising result suggests that forest recovery after the hurricane has been complex, with faster recovery of foliage at different heights resulting in similar vertical structure even as the overhead canopy is taking longer to recover in more severely damaged sites.

Overall, when looking at how much influence different landscape factors had on forest recovery from hurricane damage seven years later, the strongest effects were on canopy closure. This is further indication that at this point in time, most of the vertical structure of the forest as well as much of the groundcover vegetation had recovered while the canopy had not in more severely hit sites. This makes sense considering that the forest canopy is much more exposed to the strong wind gusts from a hurricane, and even more so at higher elevations.

6. Conclusion

Considering the widespread impacts hurricanes have on both natural and plantation forests throughout the Caribbean, it is crucial to continue with long-term research that aims to provide a clearer understanding of hurricane impacts on different components of the forest. We have shown that elevation has a large influence on which areas of the mixed plantation/Tabonuco forest at Las Casas de la Selva will be most susceptible to hurricane damage with trees at higher elevations being the most susceptible to damage as well as having long-lasting impacts that persist for at least 7 years in the case of Hurricane Maria. Within a mixed plantation/Tabonuco forest, we have shown that a difference in elevation as small as 14 meters can make the difference between a site having higher or lower damage. This result has major implications for plantation forestry, and can be used to inform forest/plantation land managers that are in the plantation establishment or re-establishment phase to plant at lower elevations in tabonuco forest in order to avoid the worst hurricane damage.

Ricoh Theta PC App for viewing 360° photos without the VR Headset:

Author Contributions

MC conceptualized and established the project, established the survey points, conducted the fieldwork, data entry, statistical analysis, created the figures and wrote the manuscript. MK provided important guidance and support to MC including conceptualizing the study and writing the manuscript. Dr. Stacy Nelson provided important guidance, helped MC in the establishment of survey points, and proofread the manuscript. Thrity Vakil played an important role by allowing MC to conduct his research on the property and provided much needed information on the history of the property as well as provided critical insight towards the damage caused to the property/forests/plantations and recovery.

Data Availability Statement

The 360° photos used to support our findings are in the process of being added to Dryad. In the meantime, please contact us directly to gain access our data.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible by funding provided through the McIntire Stennis Capacity Grant #427319-20233. We would like to provide a special thank you to Thrity Vakil, the head of the Tropic Ventures Sustainable Forestry & Rainforest Enrichment Project for her enthusiastic support. She not only allowed us to use the property for our research project but also went out of her way to provide housing and the use of facilities to the principal investigator.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Walsh, Kevin J. E., John L. McBride, Philip J. Klotzbach, Sethurathinam Balachandran, Suzana J. Camargo, Greg Holland, Thomas R. Knutson, et al. 2016. “Tropical Cyclones and Climate Change.” WIREs Climate Change 7 (1): 65–89. [CrossRef]

- Knutson, Thomas R., John L. Mcbride, Johnny Chan, Kerry Emanuel, Greg Holland, Chris Landsea, Isaac Held, James P. Kossin, A. K. Srivastava, and Masato Sugi. 2010. “Tropical Cyclones and Climate Change.” Nature Geoscience 3 (3): 157–63. [CrossRef]

- Knutson, Thomas, Suzana J. Camargo, Johnny C. L. Chan, Kerry Emanuel, Chang-Hoi Ho, James Kossin, Mrutyunjay Mohapatra, et al. 2020. “Tropical Cyclones and Climate Change Assessment: Part II: Projected Response to Anthropogenic Warming.” Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 101 (3): E303–22.

- Radfar, Soheil, Hamed Moftakhari, and Hamid Moradkhani. 2024. “Rapid Intensification of Tropical Cyclones in the Gulf of Mexico Is More Likely during Marine Heatwaves.” Communications Earth & Environment 5 (1): 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Balaguru, Karthik, Gregory R. Foltz, and L. Ruby Leung. 2018. “Increasing Magnitude of Hurricane Rapid Intensification in the Central and Eastern Tropical Atlantic.” Geophysical Research Letters 45 (9): 4238–47. [CrossRef]

- Li, Xudong, Dan Fu, John Nielsen-Gammon, Sudershan Gangrade, Shih-Chieh Kao, Ping Chang, Mario Morales Hernández, Nathalie Voisin, Zhe Zhang, and Huilin Gao. 2023. “Impacts of Climate Change on Future Hurricane Induced Rainfall and Flooding in a Coastal Watershed: A Case Study on Hurricane Harvey.” Journal of Hydrology 616 (January):128774. [CrossRef]

- Reed, Kevin A., Michael F. Wehner, and Colin M. Zarzycki. 2022. “Attribution of 2020 Hurricane Season Extreme Rainfall to Human-Induced Climate Change.” Nature Communications 13 (1): 1905. [CrossRef]

- Trenberth, Kevin E. 2011. “Changes in Precipitation with Climate Change.” Climate Research 47 (1/2): 123–38.

- Pasch, Richard, Andrew Penny, and Robbie Berg. 2017. National Hurricane Center Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Maria.

- Lopez-Cardalda, Guillermo, Melvin Lugo-Alvarez, Sergio Mendez-Santacruz, Eduardo Ortiz Rivera, and Erick Aponte Bezares. 2018. “Learnings of the Complete Power Grid Destruction in Puerto Rico by Hurricane Maria.” In 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Technologies for Homeland Security (HST), 1–6. Woburn, MA, USA: IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Yishan, Maria Sevillano-Rivera, Tao Jiang, Guangyu Li, Irmarie Cotto, Solize Vosloo, Corey M. G. Carpenter, et al. 2020. “Impact of Hurricane Maria on Drinking Water Quality in Puerto Rico.” Environmental Science & Technology 54 (15): 9495–9509. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Yanlei, Robinson I. Negron-Juarez, Christina M. Patricola, William D. Collins, Maria Uriarte, Jazlynn S. Hall, Nicholas Clinton, and Jeffrey Q. Chambers. 2018. “Rapid Remote Sensing Assessment of Impacts from Hurricane Maria on Forests of Puerto Rico.” PeerJ PrePrints, March. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Yanlei, Robinson I. Negrón-Juárez, and Jeffrey Q. Chambers. 2020. “Remote Sensing and Statistical Analysis of the Effects of Hurricane María on the Forests of Puerto Rico.” Remote Sensing of Environment 247 (September):111940. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Tangao, and Ronald B. Smith. 2018. “The Impact of Hurricane Maria on the Vegetation of Dominica and Puerto Rico Using Multispectral Remote Sensing.” Remote Sensing 10 (6): 827. [CrossRef]

- Uriarte, María, Jill Thompson, and Jess K. Zimmerman. 2019. “Hurricane María Tripled Stem Breaks and Doubled Tree Mortality Relative to Other Major Storms.” Nature Communications 10 (1): 1362. [CrossRef]

- Tanner, E. V. J., V. Kapos, and J. R. Healey. 1991. “Hurricane Effects on Forest Ecosystems in the Caribbean.” Biotropica 23 (4): 513–21. [CrossRef]

- Tanner, Edmund V. J., Francisco Rodriguez-Sanchez, John R. Healey, Robert J. Holdaway, and Peter J. Bellingham. 2014. “Long-Term Hurricane Damage Effects on Tropical Forest Tree Growth and Mortality.” Ecology 95 (10): 2974–83. [CrossRef]

- Walker, Lawrence R. 1991. “Tree Damage and Recovery From Hurricane Hugo in Luquillo Experimental Forest, Puerto Rico.” Biotropica 23 (4): 379–85. [CrossRef]

- Walker, Lawrence R., Janice Voltzow, James D. Ackerman, Denny S. Fernandez, and Ned Fetcher. 1992. “Immediate Impact of Hurricance Hugo on a Puerto Rican Rain Forest.” Ecology 73 (2): 691–94. [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, Jess K., Edwin M. Everham, Robert B. Waide, D. Jean Lodge, Charlotte M. Taylor, and Nicholas V. L. Brokaw. 1994. “Responses of Tree Species to Hurricane Winds in Subtropical Wet Forest in Puerto Rico: Implications for Tropical Tree Life Histories.” Journal of Ecology 82 (4): 911–22. [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, Jess K., Michael R. Willig, Lawrence R. Walker, and Whendee L. Silver. 1996. “Introduction: Disturbance and Caribbean Ecosystems.” Biotropica 28 (4): 414–23. [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, Jess K., James Aaron Hogan, Aaron B. Shiels, John E. Bithorn, Samuel Matta Carmona, and Nicholas Brokaw. 2014. “Seven-Year Responses of Trees to Experimental Hurricane Effects in a Tropical Rainforest, Puerto Rico.” Forest Ecology and Management 332 (November):64–74. [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, Jess K., Michael R. Willig, and Edwin A. Hernández-Delgado. 2020. “Resistance, Resilience, and Vulnerability of Social-Ecological Systems to Hurricanes in Puerto Rico.” Ecosphere 11 (10): e03159. [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, Jess K., Tana E. Wood, Grizelle González, Alonso Ramirez, Whendee L. Silver, Maria Uriarte, Michael R. Willig, Robert B. Waide, and Ariel E. Lugo. 2021. “Disturbance and Resilience in the Luquillo Experimental Forest.” Biological Conservation 253 (January):108891. [CrossRef]

- Brokaw, Nicholas V. L., and Jason S. Grear. 1991. “Forest Structure Before and After Hurricane Hugo at Three Elevations in the Luquillo Mountains, Puerto Rico.” Biotropica 23 (4): 386–92. [CrossRef]

- Brokaw, Nicholas V. L., and Lawrence R. Walker. 1991. “Summary of the Effects of Caribbean Hurricanes on Vegetation.” Biotropica 23 (4): 442–47. [CrossRef]

- Boose, Emery R., Mayra I. Serrano, and David R. Foster. 2004. “Landscape and Regional Impacts of Hurricanes in Puerto Rico.” Ecological Monographs 74 (2): 335–52. [CrossRef]

- Uriarte, M., L.W. Rivera, J.K. Zimmerman, T.M. Aide, A.G. Power, and A.S. Flecker. 2004. “Effects of Land Use History on Hurricane Damage and Recovery in a Neotropical Forest.” Plant Ecology Formerly Vegetation 174 (1): 49–58. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Naomi B., María Uriarte, Ruth DeFries, Kristopher M. Bedka, Katia Fernandes, Victor Gutiérrez-Vélez, and Miguel A. Pinedo-Vasquez. 2017. “Fragmentation Increases Wind Disturbance Impacts on Forest Structure and Carbon Stocks in a Western Amazonian Landscape.” Ecological Applications 27 (6): 1901–15. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Donald A. 1983. “Effects of Hurricane Allen on Some Jamaican Forests.” The Commonwealth Forestry Review 62 (2 (191)): 107–15.

- Boose, Emery R., David R. Foster, and Marcheterre Fluet. 1994. “Hurricane Impacts to Tropical and Temperate Forest Landscapes.” Ecological Monographs 64 (4): 369–400. [CrossRef]

- Canham, Charles D., Jill Thompson, Jess K. Zimmerman, and María Uriarte. 2010. “Variation in Susceptibility to Hurricane Damage as a Function of Storm Intensity in Puerto Rican Tree Species.” Biotropica 42 (1): 87–94. [CrossRef]

- Bellingham, P.J. 1991. “Landforms Influence Patterns of Hurricane Damage: Evidence From Jamaican Montane Forests.” Biotropica 23 (4): 427–33. [CrossRef]

- Boucher, Douglas H. 1990. “Growing Back after Hurricanes.” BioScience 40 (3): 163–66. [CrossRef]

- Lugo, A.E. 2008. “Visible and Invisible Effects of Hurricanes on Forest Ecosystems: An International Review.” Austral Ecology 33 (4): 368–98. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, Mark, Sally Silverstone, Kelly Chinners Reiss, Thrity Vakil, and Molly Robertson. 2011. “Enrichissement Des Forêts Secondaires Subtropicales Par Des Plantations Linéaires Permettant Une Production Forestière Durable à Puerto Rico.” BOIS & FORETS DES TROPIQUES 309 (309): 51. [CrossRef]

- Redondo-Brenes, Alvaro. 2007. “Growth, Carbon Sequestration, and Management of Native Tree Plantations in Humid Regions of Costa Rica.” New Forests 34 (3): 253–68. [CrossRef]

- Francis, John K. 2003. “Mahogany Planting and Research in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands.” In Big-Leaf Mahogany: Genetics, Ecology, and Management, edited by Ariel E. Lugo, Julio C. Figueroa Colón, and Mildred Alayón, 329–41. Ecological Studies. New York, NY: Springer. [CrossRef]

- Francis, J. K., P. L. Weaver, and F. L. Weaver. 1988. “Performance of Hibiscus Elatus in Puerto Rico.” The Commonwealth Forestry Review 67 (4 (213)): 327–38.

- Lugo, Ariel, Carlos Rodriguez, Ian Fermont, and Ivan Vicens. 2018. “Response to Hurricanes of Pinus Caribaea Var Hondurensis Plantations in Puerto Rico.” Caribbean Naturalist 43:1–16.

- Bunce, H. W. F., and J. A. Mclean. 1990. “Hurricane Gilbert’s Impact on the Natural Forests And Pinus Caribaea Plantations of Jamaica.” The Commonwealth Forestry Review 69 (2 (219)): 147–55.

- Boucher, Douglas H., John H. Vandermeer, Katherine Yih, and Nelson Zamora. 1990. “Contrasting Hurricane Damage in Tropical Rain Forest and Pine Forest.” Ecology 71 (5): 2022–24. [CrossRef]

- Everham, Edwin M., and Nicholas V. L. Brokaw. 1996. “Forest Damage and Recovery from Catastrophic Wind.” The Botanical Review 62 (2): 113–85. [CrossRef]

- Lugo, Ariel E. 1997. “The Apparent Paradox of Reestablishing Species Richness on Degraded Lands with Tree Monocultures.” Forest Ecology and Management 99 (1): 9–19. [CrossRef]

- Longworth, J. Benjamin, and G. Bruce Williamson. 2020. “Composition and Diversity of Woody Plants in Tree Plantations Versus Secondary Forests in Costa Rican Lowlands.” Tropical Conservation Science 11 (1). [CrossRef]

- Imbert, Daniel, Patrick Labbέ, and Alain Rousteau. 1996. “Hurricane Damage and Forest Structure in Guadeloupe, French West Indies.” Journal of Tropical Ecology 12 (5): 663–80.

- Nelson, Mark, Sally Silverstone, Kelly C. Reiss, Patricia Burrowes, Rafael Joglar, Molly Robertson, and Thrity Vakil. 2010. “The Impact of Hardwood Line-Planting on Tree and Amphibian Diversity in a Secondary Subtropical Wet Forest of Southeast Puerto Rico.” Journal of Sustainable Forestry 29 (5): 503–16. [CrossRef]

- Ewel, J. J., and J. L. Whitmore. 1973. The Ecological Life Zones of Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

- Zhou, Xiangbei, and Chungan Li. 2023. “Mapping the Vertical Forest Structure in a Large Subtropical Region Using Airborne LiDAR Data.” Ecological Indicators 154 (October):110731. [CrossRef]

- Jennings, SB, ND Brown, and D Sheil. 1999. “Assessing Forest Canopies and Understorey Illumination: Canopy Closure, Canopy Cover and Other Measures.” Forestry: An International Journal of Forest Research 72 (1): 59–74. [CrossRef]

- Pascarella, John B., T. Mitchell Aide, and Jess K. Zimmerman. 2004. “Short-Term Response of Secondary Forests to Hurricane Disturbance in Puerto Rico, USA.” Forest Ecology and Management 199 (2–3): 379–93. [CrossRef]

- Weaver, Peter L. 1986. “Hurricane Damage and Recovery in the Montane Forests of the Luquillo Mountains of Puerto Rico.” Caribbean Journal of Science 22(1-2):53–70.

- Zhang, Xiuying, Ying Wang, Hong Jiang, and Xiaoming Wang. 2013. “Remote-Sensing Assessment of Forest Damage by Typhoon Saomai and Its Related Factors at Landscape Scale.” International Journal of Remote Sensing 34 (21): 7874–86. [CrossRef]

- Van Beusekom, Ashley E., Nora L. Álvarez-Berríos, William A. Gould, Maya Quiñones, and Grizelle González. 2018. “Hurricane Maria in the U.S. Caribbean: Disturbance Forces, Variation of Effects, and Implications for Future Storms.” Remote Sensing 10 (9): 1386. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Qiong, and Mei Yu. 2022. “Elevation Regimes Modulated the Responses of Canopy Structure of Coastal Mangrove Forests to Hurricane Damage.” Remote Sensing 14 (6): 1497. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Property Map of Las Casas de la Selva by Zone.

Figure 1.

Property Map of Las Casas de la Selva by Zone.

Figure 2.

(a) Tracks for some of the more recent storms to impact the island of Puerto Rico; and (b) aerial photos showing Las Casas de la Selva before and after the storm. Images courtesy of Thrity Vakil.

Figure 2.

(a) Tracks for some of the more recent storms to impact the island of Puerto Rico; and (b) aerial photos showing Las Casas de la Selva before and after the storm. Images courtesy of Thrity Vakil.

Figure 3.

Photos documenting the state of the property 7 years after Hurricane Maria. (a) This area of the forest was hit hard with many trees displaying a reduced canopy; (b and c) These two photos show uprooted trees still alive; and (d) This photo shows a severely damaged tree with relatively recent growth. Photos taken by Michael Caslin.

Figure 3.

Photos documenting the state of the property 7 years after Hurricane Maria. (a) This area of the forest was hit hard with many trees displaying a reduced canopy; (b and c) These two photos show uprooted trees still alive; and (d) This photo shows a severely damaged tree with relatively recent growth. Photos taken by Michael Caslin.

Figure 4.

Map showing location of survey points established at 40-meter intervals along the trails within zones II and III of the property.

Figure 4.

Map showing location of survey points established at 40-meter intervals along the trails within zones II and III of the property.

Figure 5.

Garmin GPSMAP 65s unit.

Figure 5.

Garmin GPSMAP 65s unit.

Figure 6.

Ricoh Theta V 360° camera and accessories.

Figure 6.

Ricoh Theta V 360° camera and accessories.

Figure 7.

Oculus Go Virtual Reality Headset.

Figure 7.

Oculus Go Virtual Reality Headset.

Figure 8.

Photo example visualizing how the PI used the VR headset to analyze forest vertical structure.

Figure 8.

Photo example visualizing how the PI used the VR headset to analyze forest vertical structure.

Figure 9.

Hemispherical photo focusing on the ground with 51 systematic sampling points. Points were enlarged to increase visibility.

Figure 9.

Hemispherical photo focusing on the ground with 51 systematic sampling points. Points were enlarged to increase visibility.

Figure 10.

Analysis of canopy closure using the % Cover app.

Figure 10.

Analysis of canopy closure using the % Cover app.

Figure 11.

Transformed Vertical Habitat Diversity Index (Johnson and Box-Cox) showing no association between damage rank.

Figure 11.

Transformed Vertical Habitat Diversity Index (Johnson and Box-Cox) showing no association between damage rank.

Figure 12.

Comparison of Grass/Herbaceous ground cover showing there to be a greater concentration at higher impacted areas.

Figure 12.

Comparison of Grass/Herbaceous ground cover showing there to be a greater concentration at higher impacted areas.

Figure 13.

There was a strong association between lower canopy closure at sites at higher elevations seven years post-Maria.

Figure 13.

There was a strong association between lower canopy closure at sites at higher elevations seven years post-Maria.

Figure 14.

Comparison of % canopy closure by damage rank categories.

Figure 14.

Comparison of % canopy closure by damage rank categories.

Figure 15.

Logistic Regression showing elevation had a significant influence on the damage ranks assessed at each site.

Figure 15.

Logistic Regression showing elevation had a significant influence on the damage ranks assessed at each site.

Figure 16.

Time series showing forest change at the property of Las Casas de la Selva. (a) Photo taken along the driveway in June 2012. (b) Photo taken shortly after Hurricane Maria made landfall in September 2017. (c) Photo showing the current conditions at the site in July 2024. Photo credits Michael Caslin (a and c), Thrity Vakil (b).

Figure 16.

Time series showing forest change at the property of Las Casas de la Selva. (a) Photo taken along the driveway in June 2012. (b) Photo taken shortly after Hurricane Maria made landfall in September 2017. (c) Photo showing the current conditions at the site in July 2024. Photo credits Michael Caslin (a and c), Thrity Vakil (b).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).