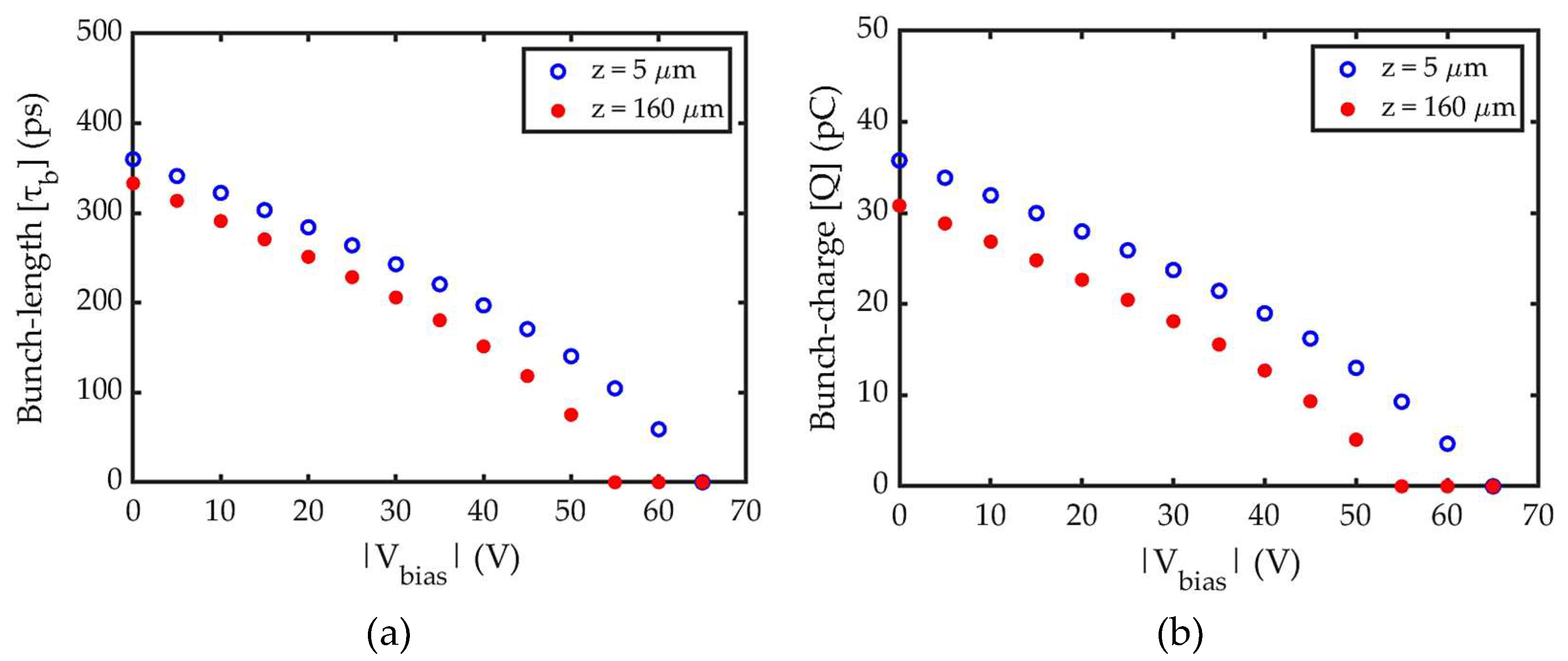

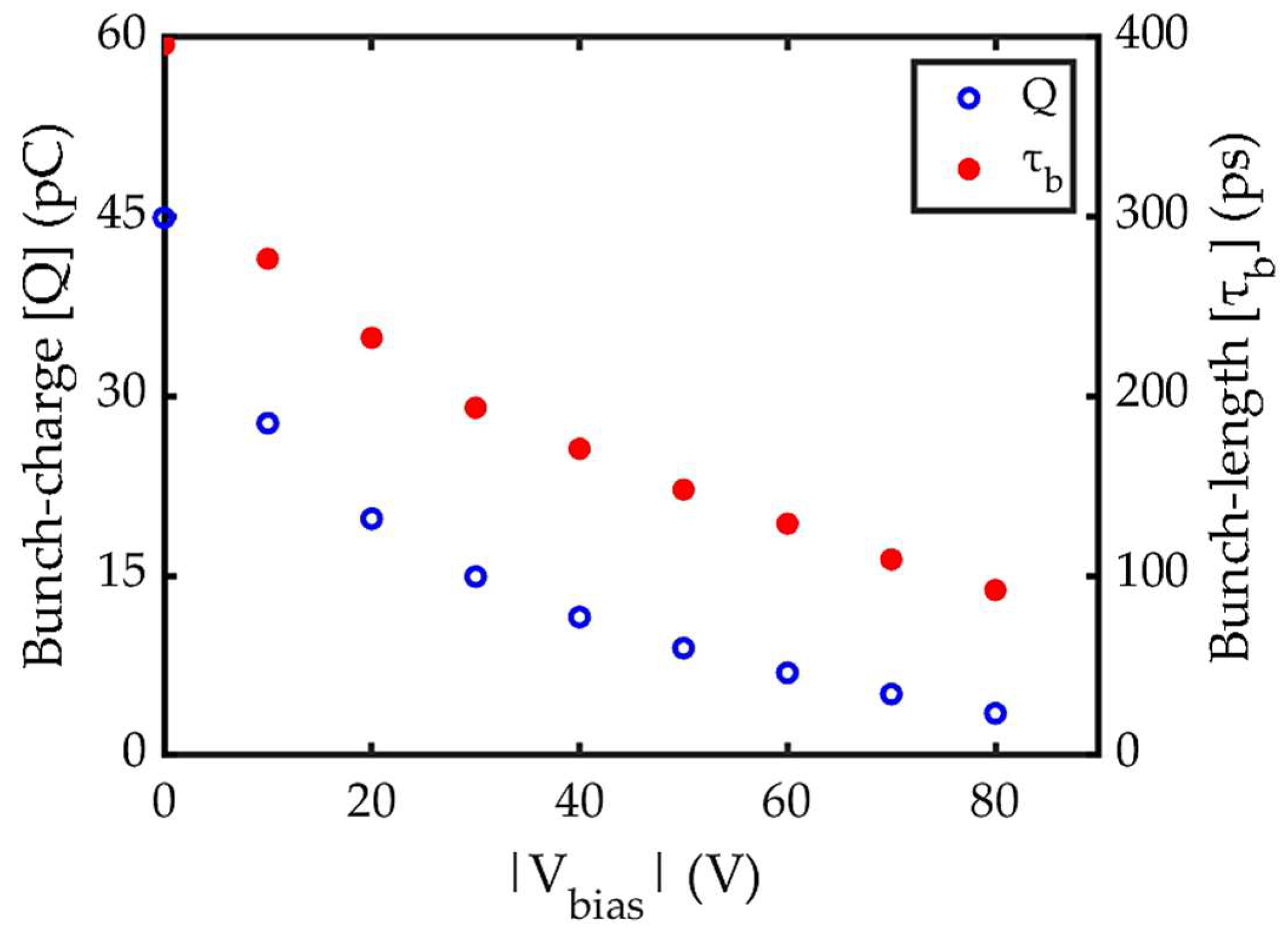

5.1. Performance of the RF Gated Gun (Cathode – Grid Space)

The bunch characteristics, specifically the full width (

) and charge (

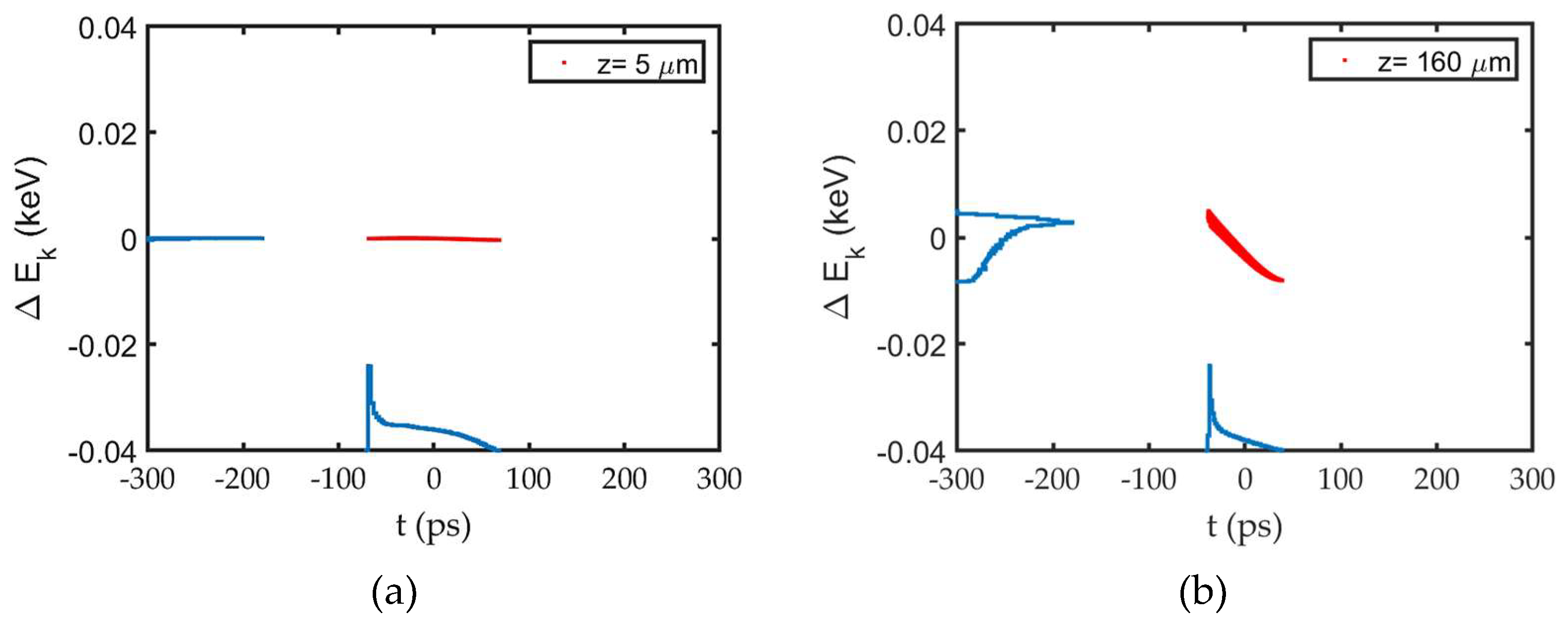

), are analyzed at two positions: near cathode (z = 5 µm) and at the grid (z = 160 µm).

is calculated with the threshold of 0.01% of the peak value of

. The dependence of these parameters on the absolute value of biasing voltage i.e.

with a fixed

(65 V) is presented in

Figure 5.

Results indicate that for the same

, both

and

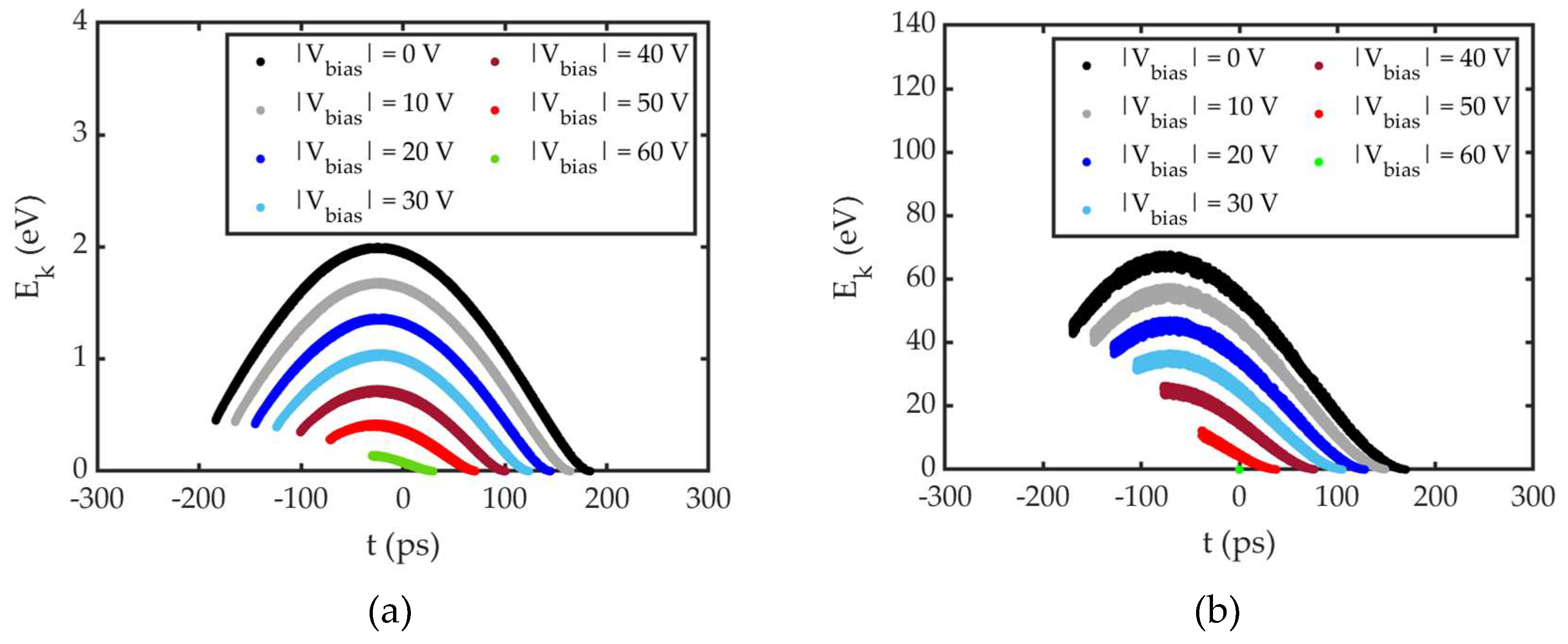

are smaller at grid (z = 160 µm) compared to near cathode (z = 5 µm). To discuss this calculation outcome, we analyse the longitudinal phase space distribution as shown by

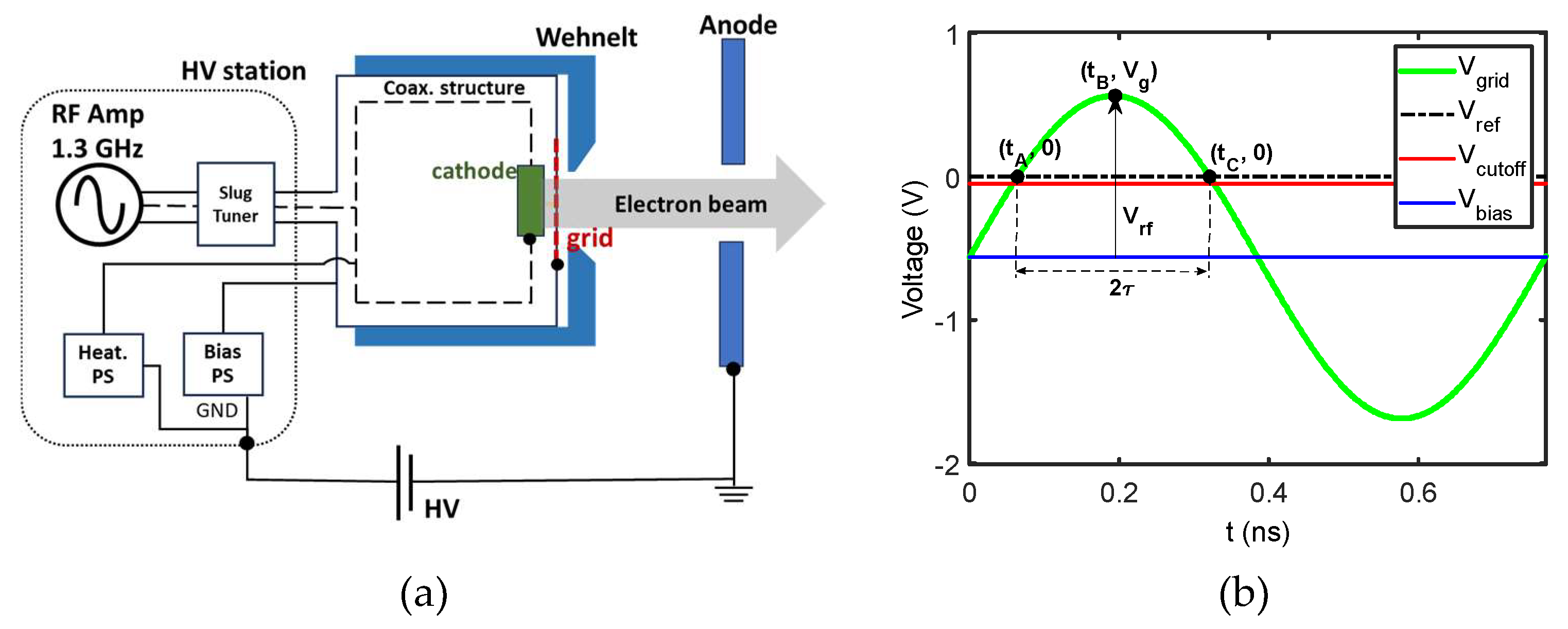

Figure 6. In RF gating, electrons are emitted within

(

Figure 2 (b)), which corresponds to the emission at different phase of the RF field, as illustrated in

Figure 6(a). Due to the phase difference, electrons emitted within

i.e. the front part of the bunch, gain energy more than those emitted within

i.e. the tail part of the bunch while moving from cathode to grid. Consequently, at the grid, energy of the front part of the bunch is higher than that of the tail part, as shown in

Figure 6(b). In this process, the electrons emitted from cathode at time close to

do not gain sufficient energy to cross the cathode-grid gap. As a result, these electrons fail to reach the grid, contributing to the reduction in both

and

, which explains why

are smaller at the grid than near the cathode.

.

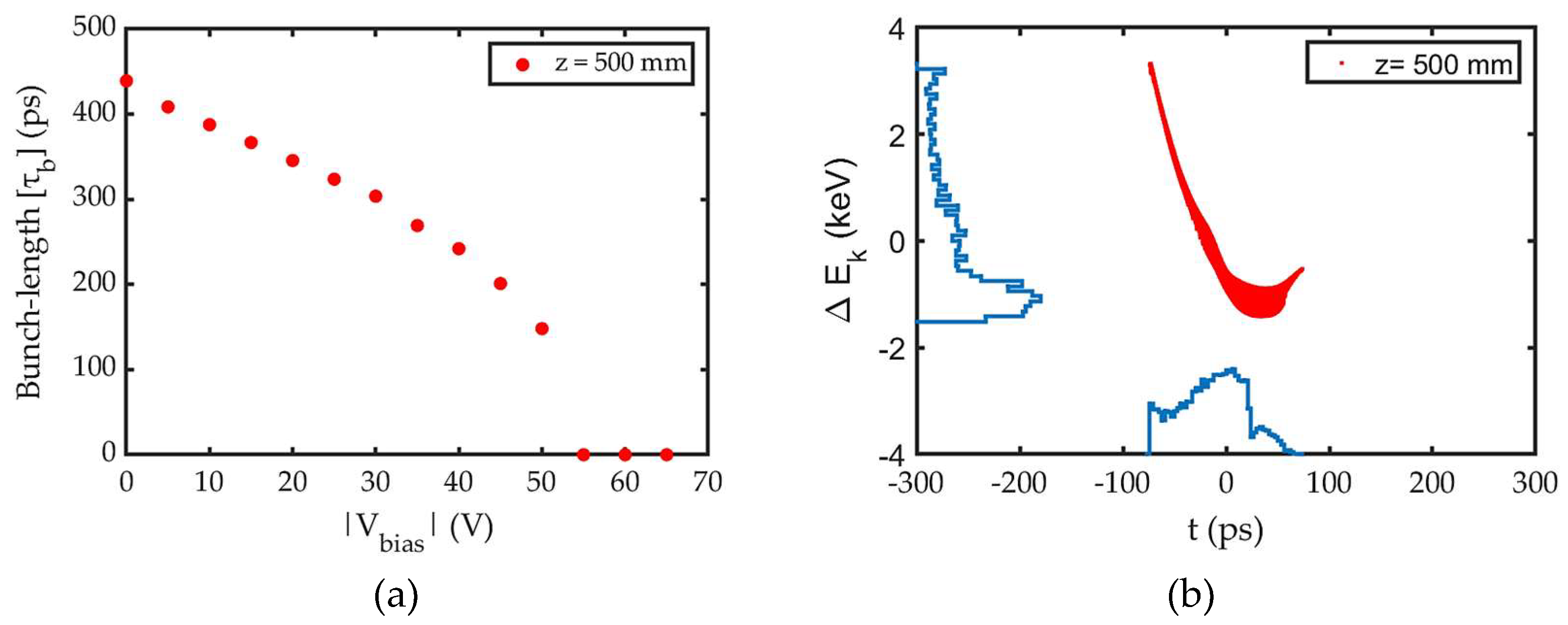

Figure 5 further shows that both

and

continue to decrease with increasing

, eventually dropping to zero for

. This trend is a fundamental characteristic of the RF gating mechanism. Since the emission area represented by

reduces with increasing

explaining the reason for reduction in both parameters. However, to further understand why

drops to zero for

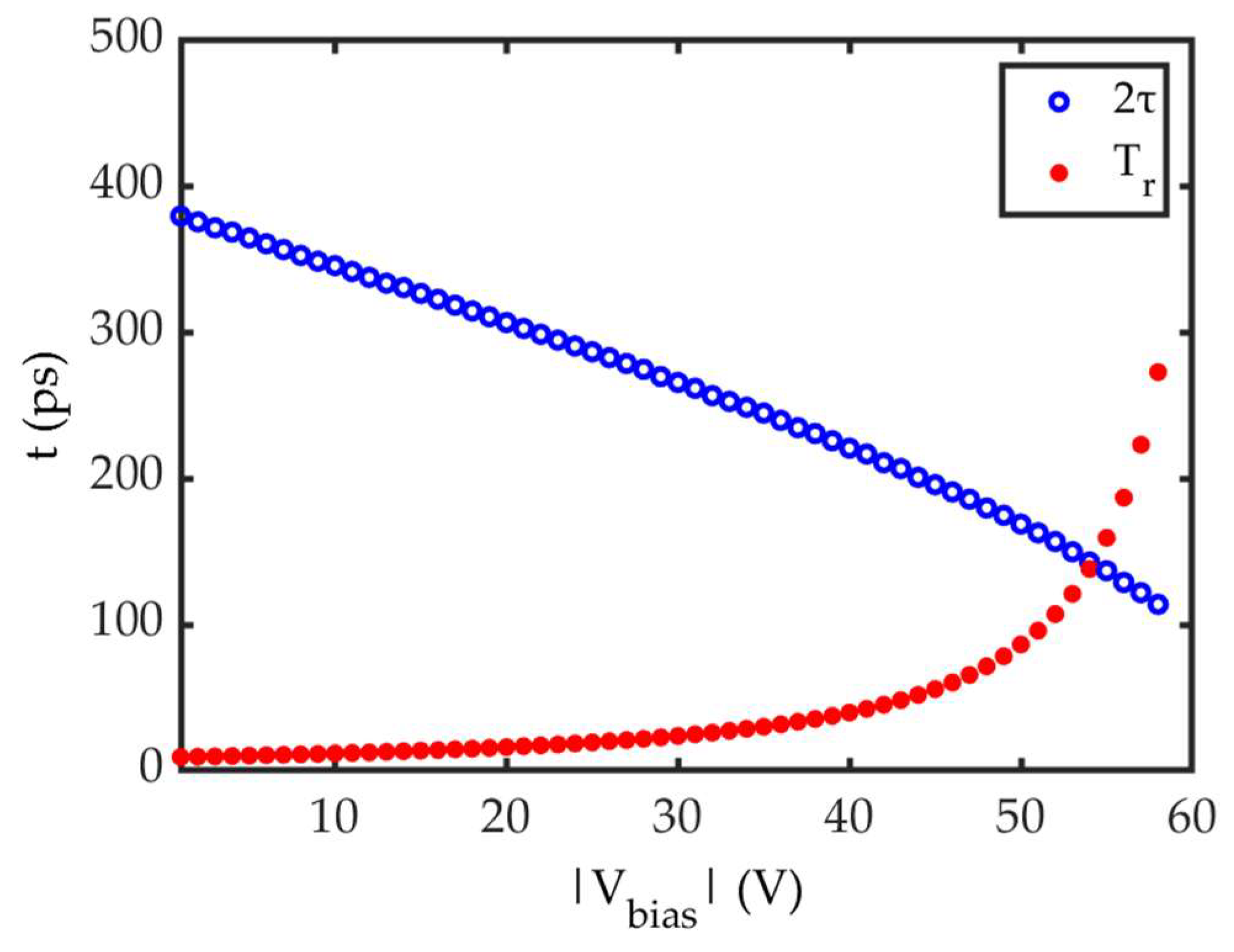

, we examined the electron transit time and the electron acceleration time. Where, the electron acceleration time corresponds to the time in which electrons emit from cathode and accelerate towards grid. The electron acceleration time is therefore same as the emission time

. The transit time

on the other hand represents an average time required for an electron to cross the cathode-grid gap (

) under the effect of time varying

.

is determined through the Eq. (5), (6), (7) and (8) given below. The equations consider the integrated RF field as given in Eq. (7), experience by the emitted electrons over the duration of the emission area and calculates

as follows:

Where

: rest mass of electron,

: Lorentz factor, and

: velocity of electron. The results of transit time and acceleration time calculations are presented in

Figure 7. For

,

exceeds the acceleration time

, indicating insufficient energy imparted to emitted electron to cross the cathode-grid gap within the available acceleration time. Consequently, electrons fail to reach the grid and return to the cathode, causing

and

to drop to zero. The longitudinal phase space distribution for

in

Figure 6 confirms this behavior.

Figure 6(a) shows electron emission, while

Figure 6(b) demonstrates no electrons reaching the grid.

.

Lastly,

Figure 5(a) and (b) showing

and

at grid, helps to determine the optimal

for achieving the required

(~ 8 pC) and smallest achievable

. This is because, electrons reaching the grid do not loss further downstream. Furthermore, the discussion on transit time and acceleration time suggests that the smallest achievable

occurs at

, since beyond this

, electrons could not reach the grid to form bunch. However, the corresponding

is only ~5 pC as seen in

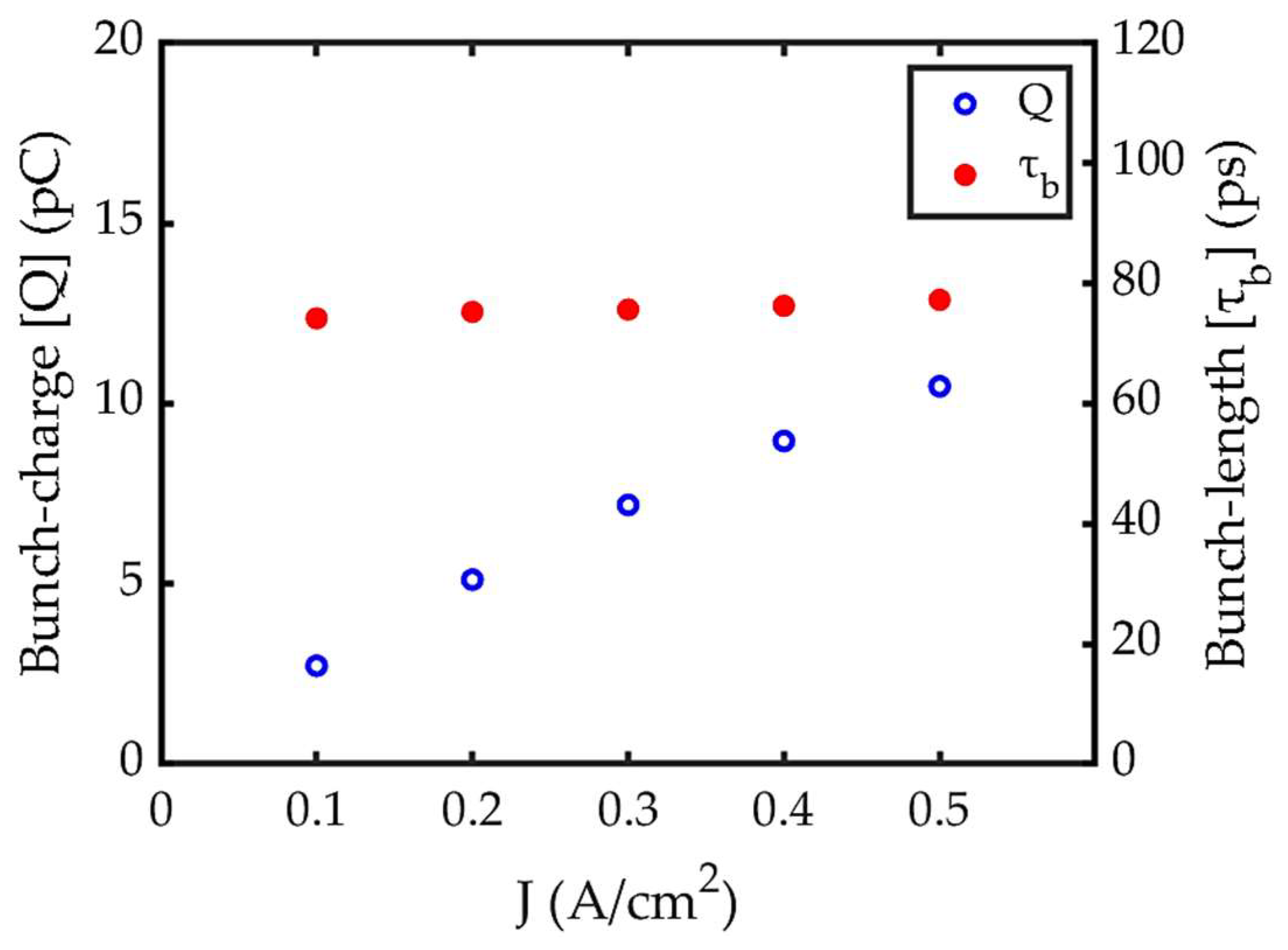

Figure 5(b). This can be resolved by increasing the emission current density from cathode.

with higher emission current density is as shown in

Figure 8. It indicates that with

,

≥ 8 pC can be achieved, if the current density is increased from 0.2 (earlier setting) to 0.4 A/cm². This higher current density can also be achieved easily by slightly increasing the heater voltage. Thus, both conditions of minimum

and required

is satisfied. As expected, there is no significant difference in

obtained with these two current densities at the grid, illustrated by

Figure 8.

Therefore, a detailed analysis of the bunch evolution, including its behavior within the cathode-grid gap and further downstream to the buncher position, is performed for and current density of 0.4 A/cm2 in the following sections. For this analysis, longitudinal phase space distribution is presented as Δ vs time where with : kinematic energy of individual electron and mean kinematic energy of the bunch.

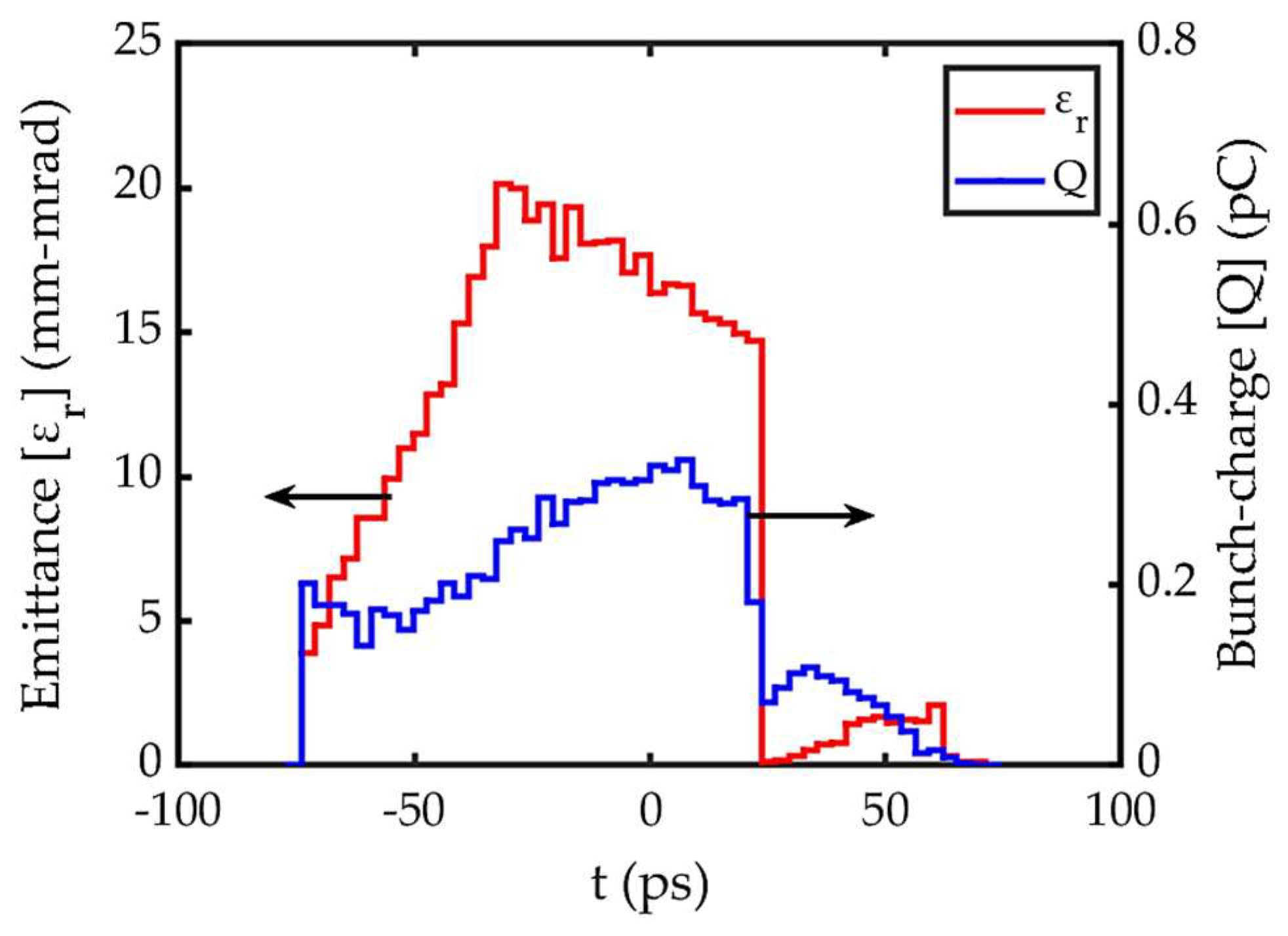

While analyzing the evolution of longitudinal phase space distribution of the bunch from cathode to grid for

(

Figure 9), we observed that the density of the bunch head is higher than the tail. Careful analysis suggests that this comes from the interplay between time-dependent electron emission and

. At

(

Figure 2 (b)), electron emission begins and gradually experience the high accelerating field. Subsequently, the electrons accelerated by the high accelerating field can catch up with the emitted electrons before them. This causes longitudinal compression of the electrons emitted in this region, giving higher density at the bunch head. Electrons emitted in the later region can no longer catch up the earlier emitted electrons. This leads to a more uniform density distribution in the remaining part of the bunch until

falls below the emission threshold and the density drops to zero, as depicted by

Figure 9 (a). This asymmetric electron distribution from the initial emission time plays a crucial role in shaping the bunch evolution downstream of the grid. As shown in

Figure 9 (b), the distribution remains unchanged at the grid i.e. high current density at bunch head. The further evolution downstream the grid is discussed in the following sections.

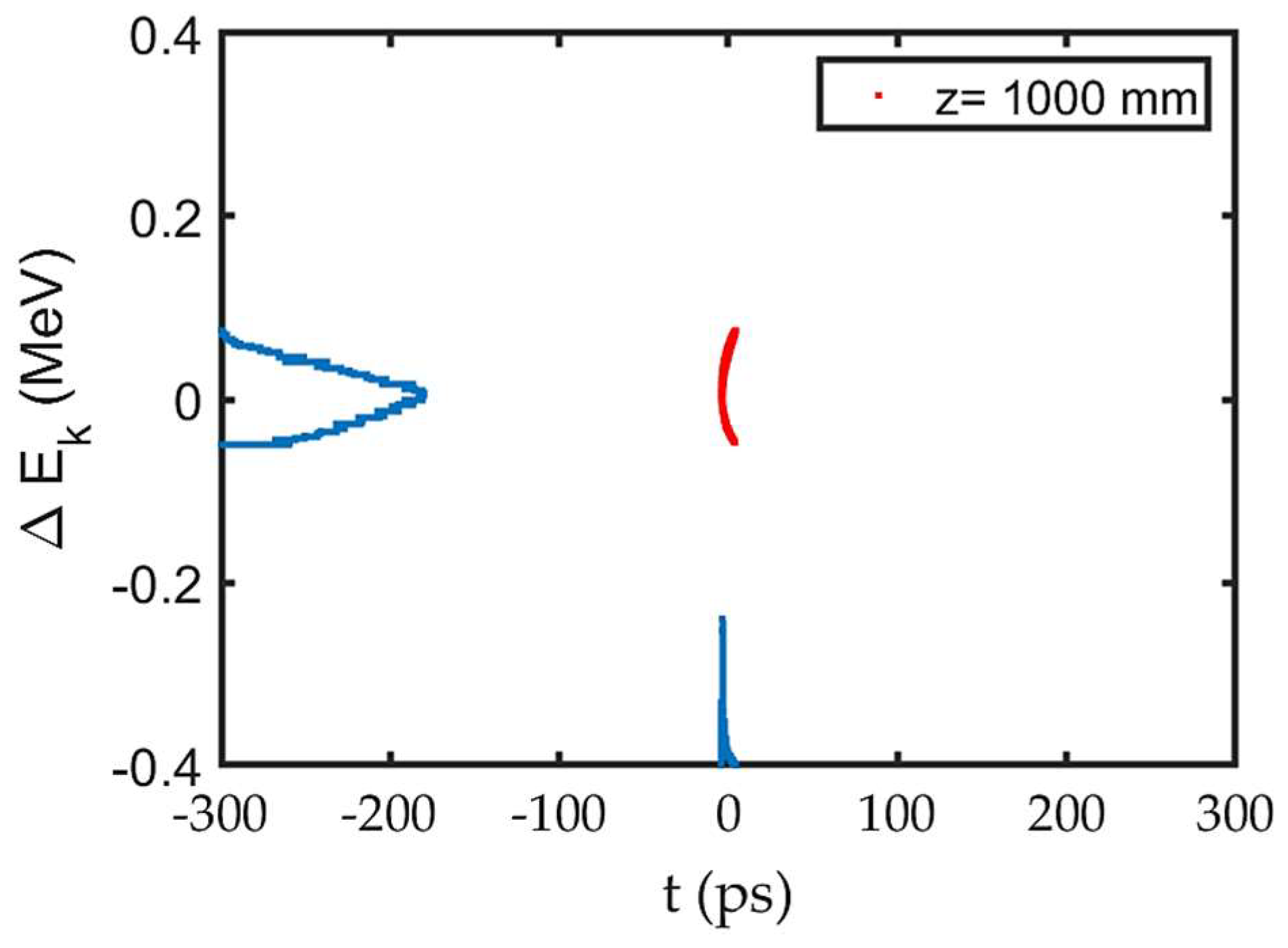

5.2. Performance of the RF Gated Gun (Grid – Anode Space)

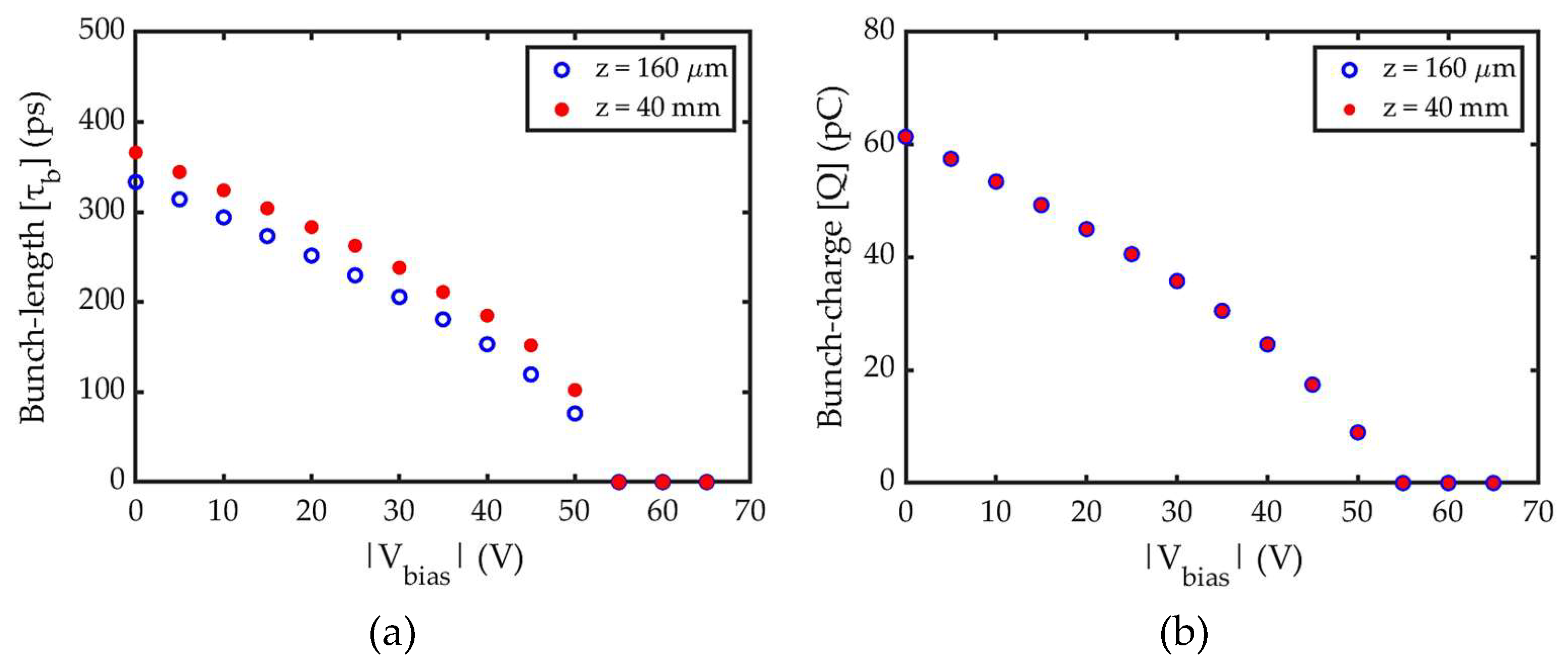

and

obtained for different

at z = 40 mm i.e. 2 mm downstream the anode is as shown in

Figure 10 (a) and (b) respectively. As expected,

downstream the anode (z= 40 mm) remains same as at grid (z= 160 µm) indicating no loss of

between the grid and the anode. However,

increases as bunch moves from grid to anode for the same

.

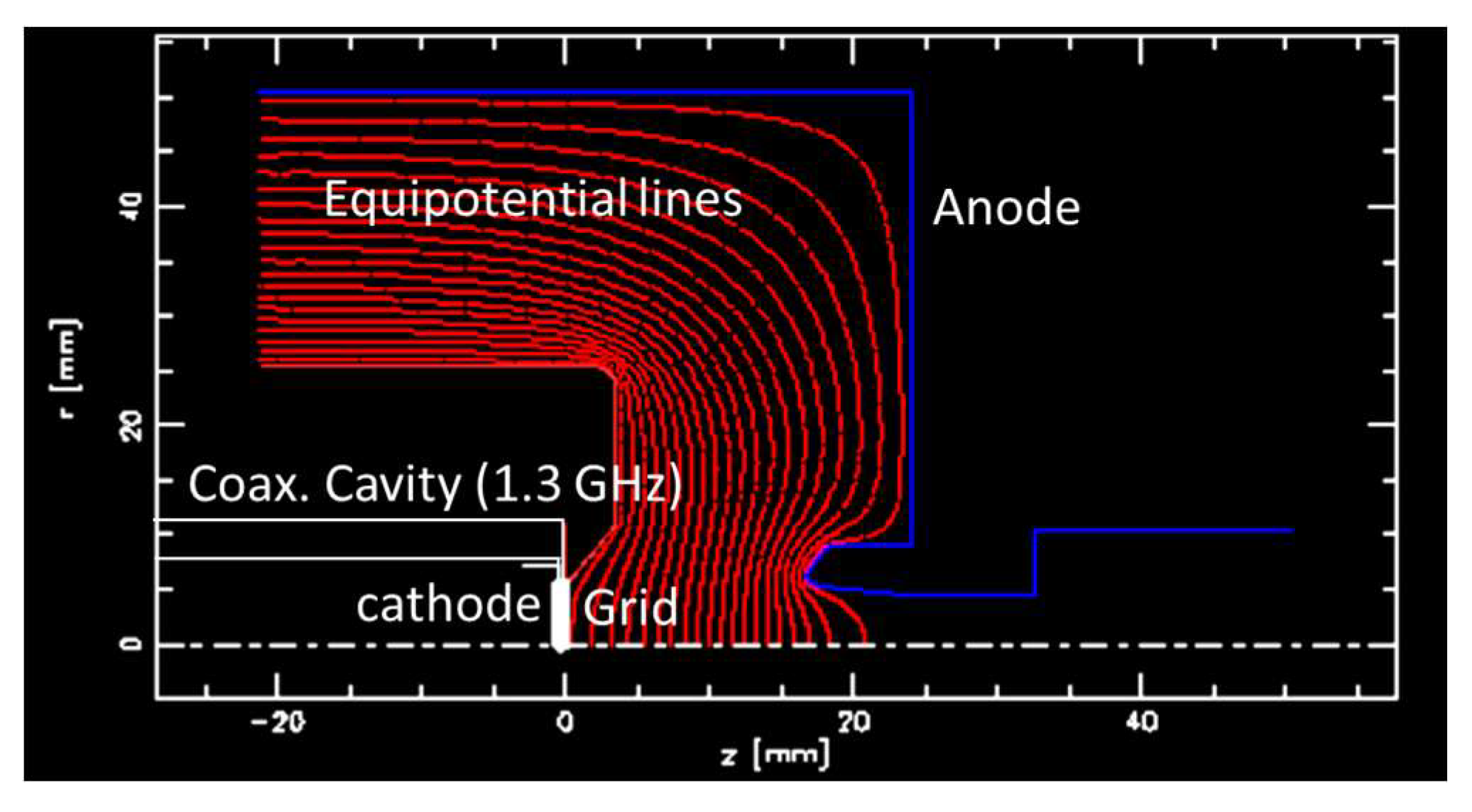

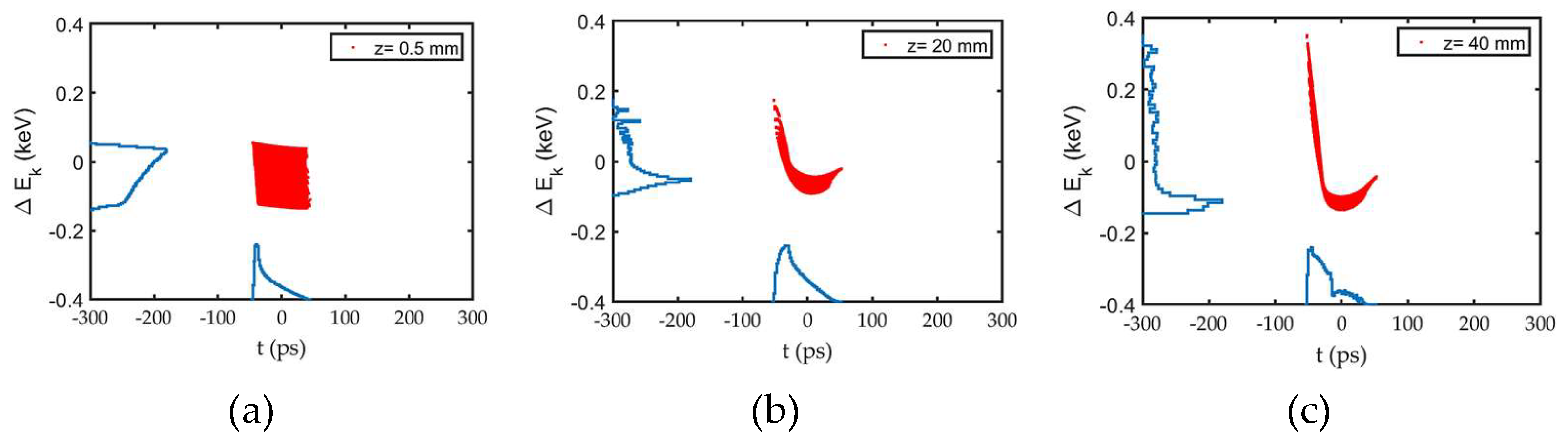

To understand the increase of

and the evolution of bunch downstream the grid up to the anode, the longitudinal phase space distribution is analysed for

as shown in

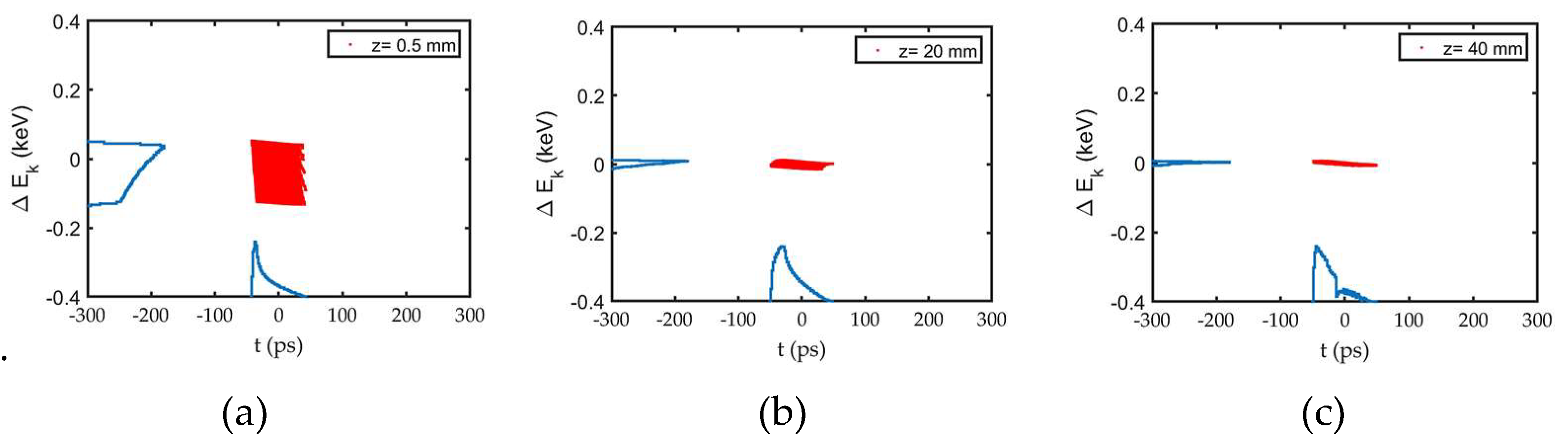

Figure 11. The result reveals an energy spread within the bunch. To investigate the origine of this spread, simulations were conducted both with and without the space charge effect. The results of the simulation without space charge effects are shown in

Figure 12. The comparison of

Figure 11(c) and

Figure 12(c) clearly demonstrates that the high energy of the bunch head is primarily due to the space charge effect. Space charge effect is more pronounced at the bunch head than at bunch tail. The reason is an asymmetric temporal distribution of the bunch i.e. high density at bunch head whose origin is described in previous section. As a result, a stronger accelerating force due to space charge on the bunch head compared to the decelerating force on the bunch tail is present. This explains both the high energy of the bunch head and the longitudinal expansion of the bunch giving longer

at z = 40 mm than at z = 160 µm. However, the energy spread observed after the grid i.e. at z= 0.5 mm, as visible in

Figure 11 (a) and

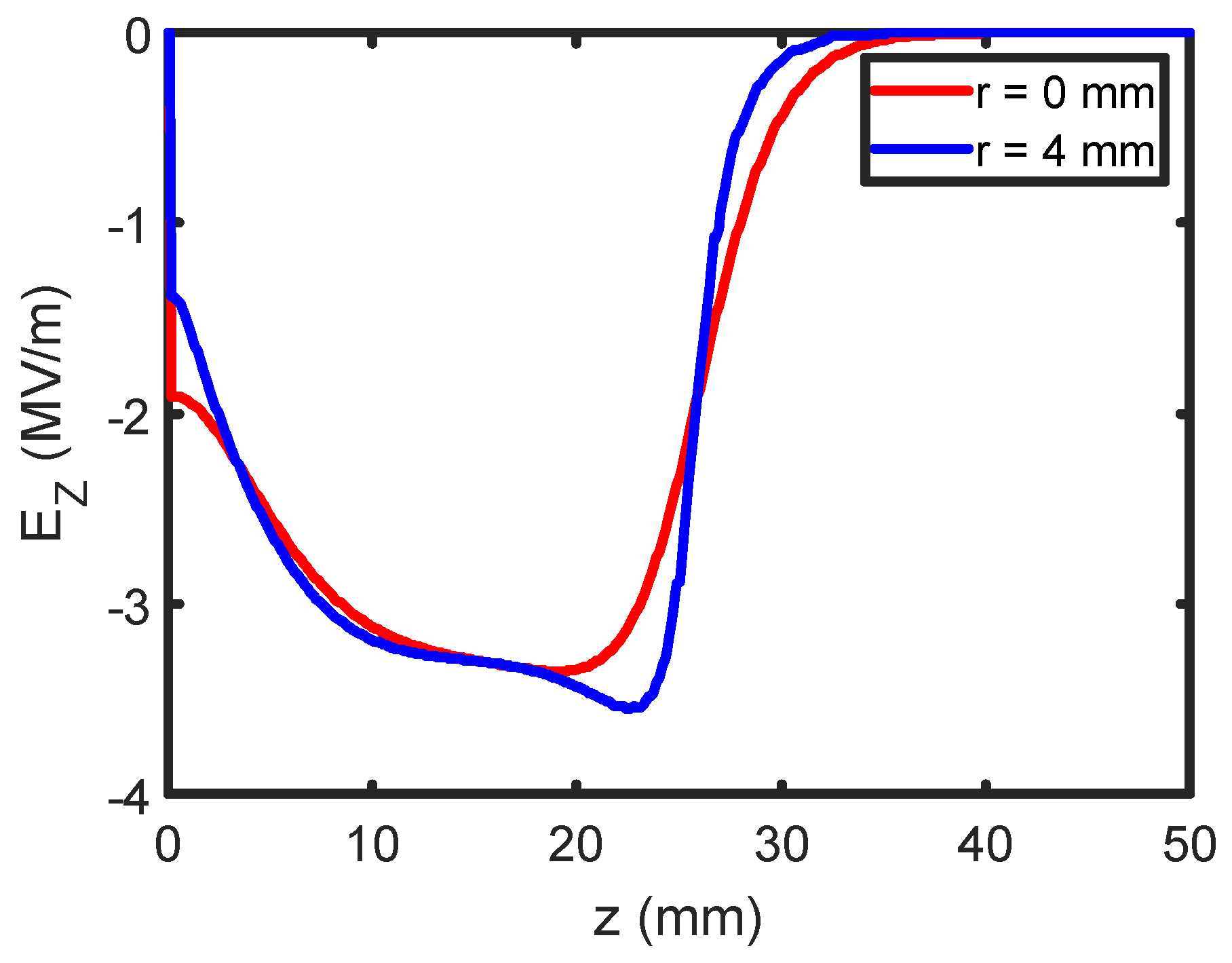

Figure 12 (a), is not attributable to the space charge effect. A detailed analysis revealed that this spread arises from the difference in the HV field experienced by electrons at different transverse positions.

Figure 13 illustrates the HV field along the axis i.e. at r = 0 and at r = 4mm. As a result, electrons along the axis gain higher energy compared to those at the outer positions, resulting in an energy spread within the bunch at this position of z= 0.5 mm.

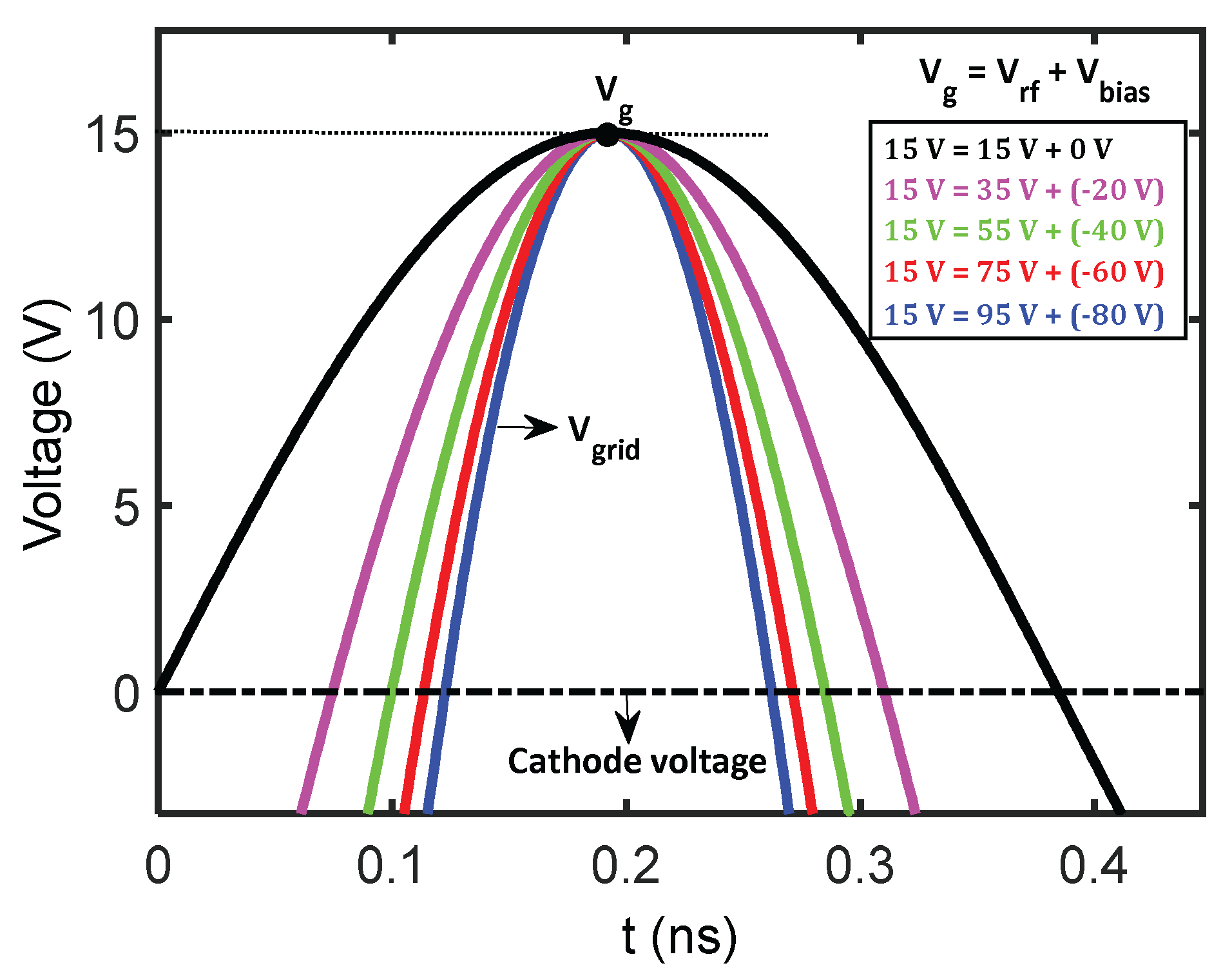

5.5. Other ways to Reduce the Bunch-Length Further

For smallest

, previous section finalizes

with

which gives

, where

, shown in

Figure 2(b). However,

can also be achieved with other combinitions of

and

. We therefore investigated the effect of other combinitions as shown in

Figure 17. While the current RF amplifier at our facility restricts us to

, future improvements may allow for higher

values. In this study, we therfore considered the combinition of

with higher

also.

Our analysis reveals that combinations with higher

values produce shorter bunch-lengths. This relation can be understood from

Figure 18, which demonstrates how the emission area for different

and

combinations (all yielding

) become sharper with increasing

and

, resulting in shorter

. However,

Figure 17 also demonstrates that increasing voltages lead to significant reduction in

. This creates a critical trade-off between achieving shorter

and maintaining sufficient

. The simulations performed in this section indicate that

with

would yield the required

and

< 148 ps but require

and RF power more than 100W.

The test bench to validate the simulation study is currently under developement at our facility. Simulations suggest that our current setup with available 1.3 GHz RF amplifier (100W giving ) satisfies the requirements adequately ( 400 ps). Therefore, the immediate investment in higher-capacity RF amplifiers is not considered for our test bench.