Submitted:

09 May 2025

Posted:

12 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

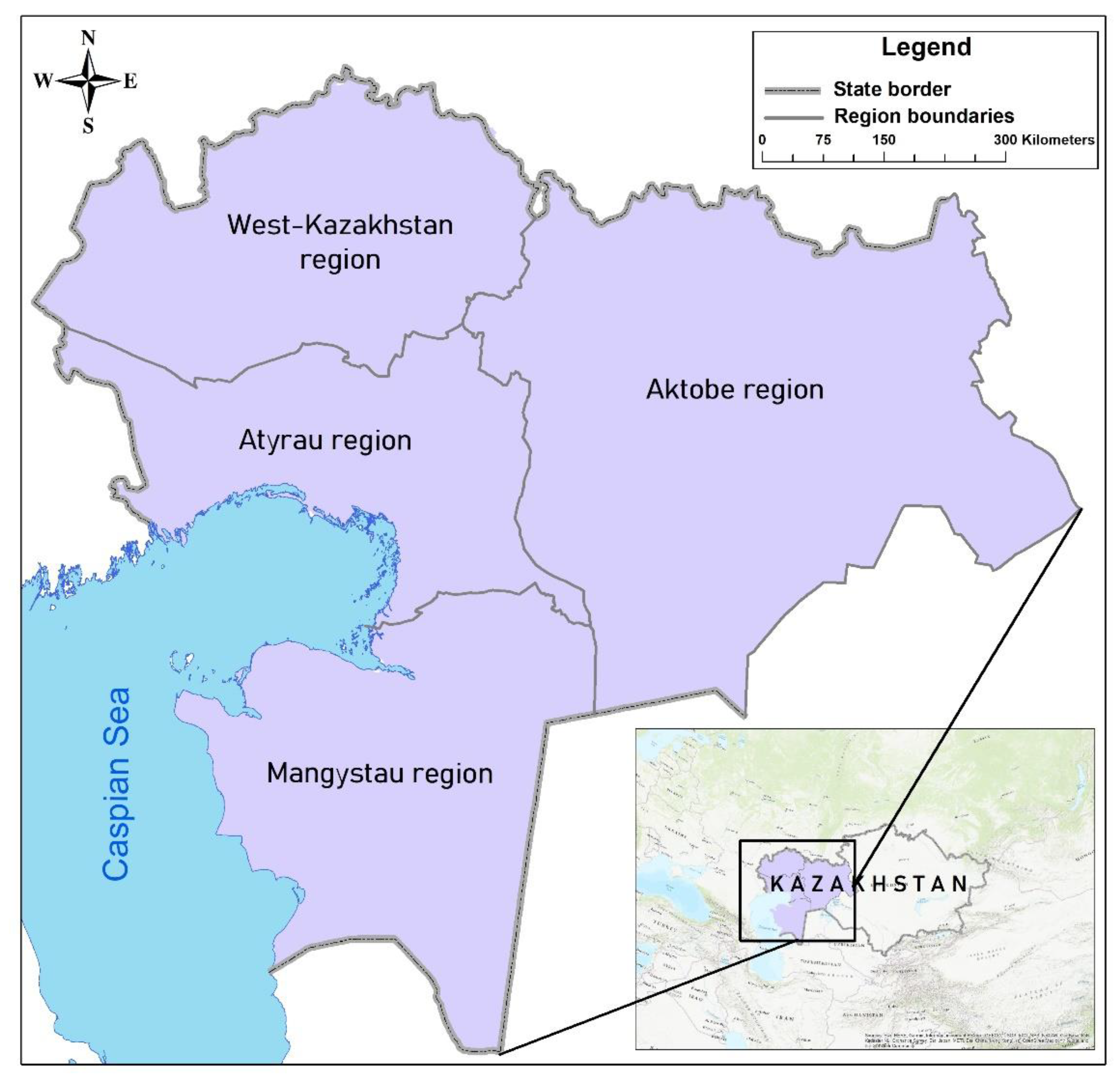

2.1. Case Study Area

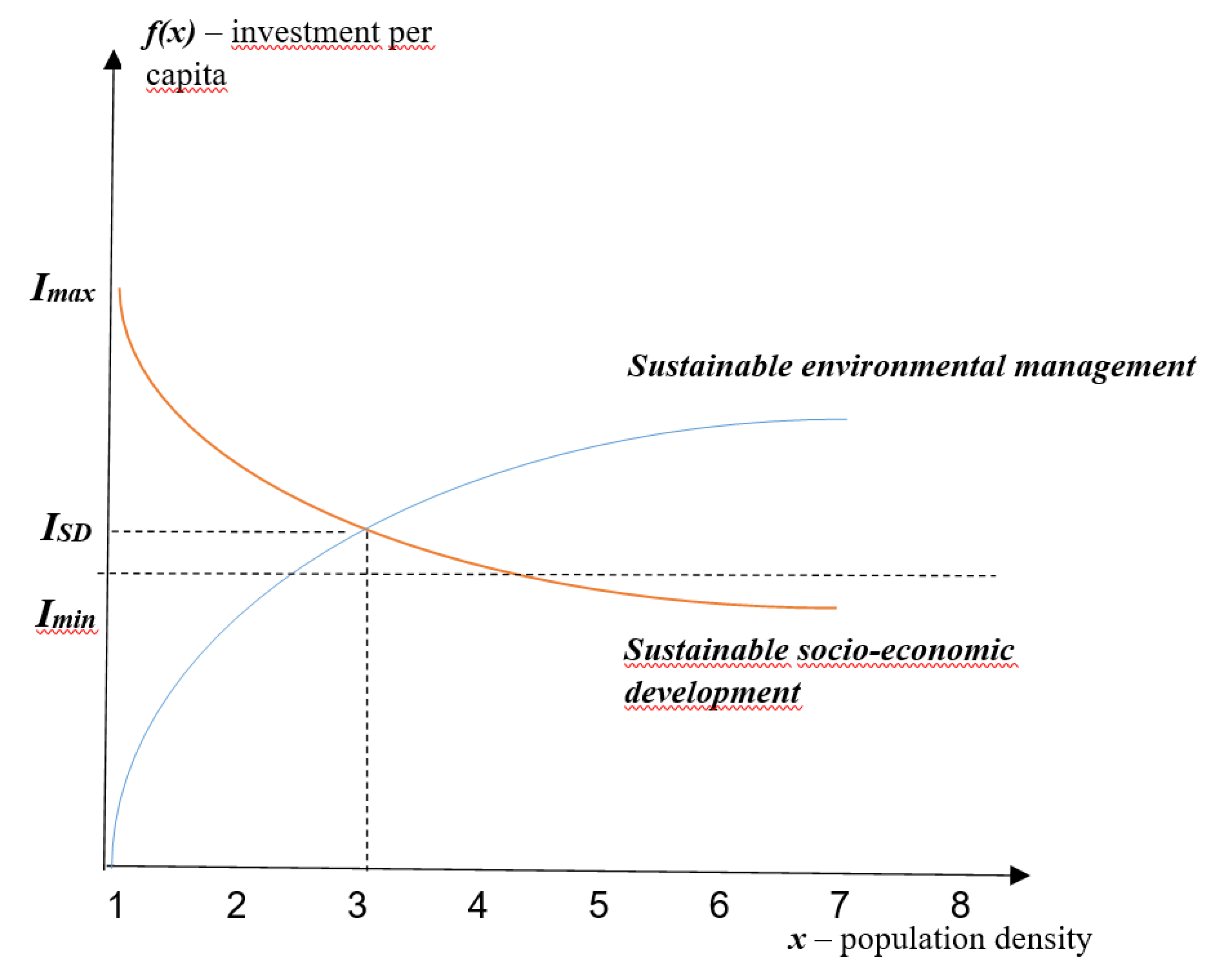

2.2. Estimation Strategy of Sustainability

- Water stress coefficient.

- Atmospheric air pollution coefficient.

- Landscape stress factor.

- Biodiversity distribution coefficient.

Actual pollutant emissions / Maximum permissible emission standard,

(Endangered species / Total number of species) / (Specially protected area / Total area),

3. Results

3.1. Sustainable Socio-Economic Development: Data-Based Insights

3.2. Sustainable Environmental Management: Data-Based Insights

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: URL https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/ru/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- United Nations. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. Available online: URL https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- United Nations. United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (Rio de Janeiro, 1992) Available online: URL https://www.un.org/ru/conferences/environment/rio1992 (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- United Nations. Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Available online: URL https://www.un.org/ru/documents/decl_conv/conventions/kyoto.shtml (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- United Nations. United Nations Millennium Declaration. Available online: URL https://www.un.org/ru/documents/decl_conv/declarations/summitdecl.shtml (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- United Nations. Millennium Summit (New York, 2000). Available online: URL https://www.un.org/ru/conferences/environment/newyork2000 (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- United Nations. World Summit on Sustainable Development (Johannesburg, 2002). Available online: URL https://www.un.org/en/conferences/environment/johannesburg2002/ (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- United Nations. United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio de Janeiro, 2012). Available online: URL https://www.un.org/ru/conferences/environment/rio2012 / accessed on 28 March 2025).

- United Nations. Paris Agreement. Available online: URL https://www.un.org/ru/climatechange/paris-agreement (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Potschin, M.; Klug, H.; Haines-Young, R.; From Vision to Action: Framing the Leitbild Concept in the context of Landscape planning. Futures 2010, 42, 656–667. [CrossRef]

- Klug, H. An integrated holistic transdisciplinary landscape planning concept after the Leitbild approach. Ecological Indicators 2012, 23, 616–626. [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D.; Randers, J.; Meadows, D. Limits to Growth. 30 years later, 3rd ed.; Earthscan: UK, 2005.

- International Labour Organization. Guidelines for a just transition towards environmentally sustainable economies and societies for all. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_emp/@emp_ent/documents/publication/wcms_432859.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Worster, D. The wealth of nature: environmental history and the ecological imagination; Oxford University Press: New York, USA, 1993.

- Nisbet, R. A. History of the Idea of Progress, 2nd ed.; Routledge: UK, 1994.

- Goudie, A. The human impact on the natural environment, 2nd ed.; MIT Univ. Press: USA, 1986.

- Boyden, S. The Human Component of Ecosystems. Humans as Components of Ecosystems 1993, 72-77.

- Van Zon, H. Geschiedenis & duurzame ontwikkeling: duurzame ontwikkeling; Netwerk Duurzaam Hoger Onderwijs:Netherlands, 2002.

- Columella. On Agriculture, Volume I: Books 1–4; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, 1941.

- Cato, M.P; Varro M.T. On agriculture; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, 1960.

- Marsh, G. P. Man and Nature: Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action; University of Washington Press: Seattle, 2003; p. 512.

- Petty, W. The Economic Writings of Sir William Petty; Legare Street Press: UK, 1899.

- Malthus, T. R. An Essay on the Principle of Population (Rev. ed.); Cambridge University Press: NY, USA, 1803.

- Holley, J. Gifford Pinchot and the Fight for Conservation: The Emergence of Public Relations and the Conservation Movement, 1901–1910. Journalism History 2016, 42, 91–100. [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, F. M.; Van Klooster, H. S. Studien über natürliche und künstliche Sulfoantimonite und Sulfoarsenite. Zeitschrift für anorganische Chemie 1912, 78, 245–268. [CrossRef]

- Veblen, T. An Inquiry into the Nature of Peace and the Terms of its Perpetuation; The Macmillan Company: London, 1918.

- Pigou, A. Economics of Welfare, 3rd ed.; The Macmillan Company: London, 1929.

- Egbert, V. De aarde betaalt: de rijkdommen der aarde en hun betekenis voor wereldhuishouding en politiek; Uitgeverij Albani, 1948.

- William, V.; Baruch B.M., Road to survival; Kessinger Publishing:USA, 2007.

- Osborn, F. Our Plundered Planet, 1st ed.; Little, Brown and Company: Boston, 1948.

- Osborn F. The limits of the earth, 1st ed.; Faber & Faber:UK, 1954.

- Kapp K. W. The social costs of private enterprise. Science and Society 1953, 17, 79–81.

- Armand D.L. Us and grandchildren; Mysl: M., 1964.. [in Russian].

- Girusov, E.V.; Bobylev, S.N. & Novoselov, A.L. Ecology and the Economics of Natural Resourse Use. In Ecology and the Economics of Nature Management, 2 nd ed.; UNITY: Moscow, Russia, 2000. [in Russian].

- Bobylev, S.N. Economics of Sustainable Development; KNORUS:Moscow, 2021. [in Russian].

- Will Steffen et al. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science Express 2015, 347, 1–41.

- Daly, H. E. Ecological economics. In Dictionary of Ecological Economics; Haddad, B. M., Solomon, B. D. Edit.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2023.

- Daly, H. E; John B.; Cobb, Jr. For the Common Good: Redirecting the Economy toward Community, the Environment, and a Substainable Future; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, 1990.

- Daly, H.E. The steady-state economy: From toward a steady-state economy. In Dictionary of Ecological Economics; Haddad, B. M., Solomon, B. D. Edit.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2023.

- Daly, H.E. Beyond Growth, The Economics of Sustainable Development; Beacon Press: Boston, USA, 1997.

- Daly, H.E. Uneconomic Growth: In Theory, in Fact, in History, and in Relation to Globalization. Clemens Lecture Series 1999, 10, 7–8.

- Wang, B.; Yan, C.; Iqbal, N.; Fareed, Z.; Arslan, A. Impact of human capital and financial globalization on environmental degradation in OBOR countries: Critical role of national cultural orientations. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022, 29. [CrossRef]

- Baloch, Q. B.; Shah, S. N.; Iqbal, N.; Sheeraz, M.; Asadullah, M.; Mahar, S.; Khan, A. U. Impact of tourism development upon environmental sustainability: a suggested framework for sustainable ecotourism. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30. [CrossRef]

- Saud, S.; Chen, S.; Haseeb, A. The role of financial development and globalization in the environment: accounting ecological footprint indicators for selected one-belt-one-road initiative countries. Journal of cleaner production 2020, 250. [CrossRef]

- Lapinskaite, I.; Skvarciany, V.; Janulevicius, P. Impact of Investment Sources for Sustainability on a Country’s Sustainable Development: Evidence from the EU. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 1990 Concept and Measurement of Human Development. Available online: URL https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-1990 (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Hickel, J. The sustainable development index: Measuring the ecological efficiency of human development in the anthropocene. Ecological Economics 2020, 167. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M. J.; Emerson, J. W.; Esty, D. C.; de Sherbinin, A.; Wendling, Z. A. Environmental Performance Index results; New Haven, CT: Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy, 2022. Available online: URL https://epi.yale.edu/ (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Ledger, S.E.H.; Loh, J.; Almond, R. et al. Past, present, and future of the Living Planet Index. Npj Biodivers 2023, 2, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Davidsdottir, Brynhildur. An appraisal of interlinkages between macro-economic indicators of economic well-being and the sustainable development goals. Ecological Economics 2021, 184.

- Stocker, A; Hinterberger, F.; Großmann, A.; Distelkamp, M.; Bernardt, F. Selection of suitable SDG indicators for the evaluation of climate mitigation scenarios meetPASS: meeting the Paris Agreement and Supporting Sustainability Working Paper No. 1; Vienna, 2018.

- Tokbergenova, A.; Kiyassova, L.; Kairova, S. Sustainable Development Agriculture in the Republic of Kazakhstan. Polish Journal of Environmental Studies 2018, 27. [CrossRef]

- Kurmanova, D.S. et al. Investments as a Factor of Sustainable Development of Rural Areas. Journal of Environmental Management and Tourism 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Mustafayev, Z.; Medeu, A.; Skorintseva, I.; Bassova, T.; Aldazhanova, G. Improvement of the Methodology for the Assessment of the Agro-Resource Potential of Agricultural Landscapes, Sustainability 2024, 16.

- Irsalieva S.A. ‘One Belt, One Road’ as an international initiative: goals, objectives, features. In the conference materials “The economic Belt of the silk Road and Current Issues of Sino-Kazakhstan Cooperation”, Astana, Kazakhstan, 2 July 2018. Available online: URL https://isca.kz/ru/analytics-ru/2765 (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- International Center for Green Technologies and Investment Projects. Available online: URL https://igtipc.org/history/ (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals in Kazakhstan. Available online: URL https://kazakhstan.un.org/ru/sdgs (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Official website of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Strategy “Kazakhstan-2050”. Available online: URL https://www.akorda.kz/ru/official_documents/strategies_and_programs (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Official website of the Prime Minister of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Strategic Plan 2025. Available online: URL https://primeminister.kz/ru/documents/gosprograms/stratplan-2025 (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Official website of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Legal Acts. Available online: URL https://akorda.kz/ru/ob-utverzhdenii-perechnya-nacionalnyh-proektov-1391918 (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Coordinating Council. Available online: URL https://eri.kz/ru/Celi_ustojchivogo_razvitija/Koordinacionnyj_sovet/ (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 2015. Available online: URL https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-2015 (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 2021-22. Available online: URL https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-2015 (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- United Nations Development Programme. National Human Development Report: Sustainable development goals and the development of Kazakhstan’s Regions Based on Their Productive Capacities, 2016. Available online: URL https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/2016humandevelopmentreportpdf1pdf.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Bureau of National Statistics of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Main socio-economic indicators for Aktobe region. Available online: URL https://stat.gov.kz/ru/region/aktobe/dynamic-tables/291541/ (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Fraser E. D; Dougill A. J; Mabee W. E; Reed M; McAlpine P. Bottom up and top down: analysis of participatory processes for sustainability indicator identification as a pathway to community empowerment and sustainable environmental management. Journal of Environmental Management 2006, 78, 114–127. [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Global SDG Database. Available online: URL https://w3.unece.org/SDG/ru/Indicator?id=140 (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Shaykhutdinova, A. A. Methods of biodiversity assessment: methodological guidelines; Orenburg State Univ. Orenburg: OGU, 2019.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian National Accounts: Insights into public investment. Available online: URL https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/insights-public-investment (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Bureau of National Statistics of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Investment activity of Aktobe region. Available online: URL https://stat.gov.kz/ru/region/aktobe/spreadsheets/?industry=&year=&name=68430&period=&type= (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources of the Republic of Kazakhstan. National report on the state of the environment and the use of natural resources of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Available online: URL https://www.gov.kz/uploads/2022/1/21/195d4245b75123a2c2aecce3ed1ccb39_original.38998496.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Bureau of National Statistics of the Agency for Strategic Planning and Reforms of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Yearbook on Aktobe region for 2022. Available online: URL https://stat.gov.kz/ru/region/aktobe/ (accessed on 21 April 2025).

| Indicators | Australia | Aktobe region (KZ) |

|---|---|---|

| Water stress coefficient | 0.05 | 0.482 |

| Atmospheric air pollution coefficient | 1.5 | 0.506 |

| Landscape stress factor | 0.51 | 0.44 |

| Biodiversity distribution coefficient | 0.04 | 4.4 |

| Ecological sensitivity index | 0.19 | 0.541 |

| Population density | 3.4 | 3.07 |

| Indicators | Aktobe region (KZ) |

|---|---|

| Investments in fixed assets | 960 038 538 thousand KZT (2022) 817 136 000 thousand KZT (2021) |

| Environmental protection investments (green) | 4 335 302 thousand KZT |

| Average annual population | 922 456 persons |

| Import | US$ 1 379 712. 9 |

| Export | US$ 3 568 372.3 |

| GRP (Gross Regional Product) | 4 416 89.4 million KZT (2022) 3 586 222.6 million KZT (2021) |

| Human development index | 0.593 |

| Population density | 3.07 |

| Per capita investment in environmental management | 170 803.23 KZT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).