1. Introduction

The global resistance levels of bacterial isolates have grown relentlessly in the last decades regardless of their source, i.e., clinical settings, in-patients, community, food-related or environmental niches. This led to the increase in the overall morbidity and mortality due to multidrug-resistant bacteria infections [

1]. An estimated 4.95 million deaths worldwide in 2019 were associated with bacterial antimicrobial resistance (AMR), of which 12.7 million deaths have been directly attributed by AMR. Multidrug resistance organsms (MDRO) that include

Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and

Enterobacter species acronymed as ESKAPE pathogens associated AMR deaths were responsible for 929,000 deaths attributable to AMR [

2]. This magnitude of death toll indicates that over 10 million deaths are expected by 2050 [

3]

In clinical practice, antibiotics primarily target bacterial nucleic acids, proteins, and peptidoglycan synthesis. Designing fundamentally new antibacterial drugs with novel modes of action and new targets, on the other hand, remains a potential option. Several novel inhibitors, such as non fluoroquinolone bacterial topoisomerase inhibitors (NBTI) cell division (FtsZ) inhibitors, peptide deformylase inhibitors, fatty acid synthesis (FabI) inhibitors, energy metabolism agents, and bacterial membrane active chemicals, have been produced [

4]. Forexample, the first novel inhibitor, NBTI bind to catalytic center of DNA gyrase/ topoisomerase adjacent to fluoroquinolone binding site, retain potency against fluoroquinolone resistant bacteria by stabilizing DNA cleavage complex [

5].

The recent implication of regulatory sRNAs in antibiotic response and resistance in several bacterial pathogens suggests that they should be considered innovative drug targets [

6]. Antibiotic overuse has resulted in a situation where multidrug-resistant bacteria have become a serious threat to human health around the world. A better knowledge of the principles of pathogens utilizes to adapt to, respond to, and resist antibiotics would open the way for the development of new medicines. Antibiotics are therapeutically relevant stressors that trigger defensive responses in bacterial pathogens [

6,

7].

The coordination of gene expression requires RNA-based interactions between noncoding RNAs and proteins, RNAs, and/or DNA. Antimicrobial, therapeutic, and synthetic biology applications are increasingly focusing on regulatory interactions. There are hundreds of noncoding regulatory RNAs in bacteria, with trans-encoded sRNAs being the most numerous. Short, imperfect base-pairing interactions are used by sRNAs to bind to their mRNA targets [

7].

Most of the previously described sRNAs have been studied in

Enterobacterales, such as

Escherichia coli or

Salmonella spp. However, by using means of differential RNA sequencing, sRNAs have been identified essentially in all bacterial and archaeal species including

alphaproteobacteria, such as photosynthetic

Rhodobacter species, plant-symbiotic rhizobia, and the mammalian pathogen

Brucella abortus [

8].

Small regulatory RNAs are the most common RNA regulators in bacteria, and most frequently bind to one of the major RNA-binding proteins, Hfq or ProQ. Hfq- and ProQ-associated sRNAs usually affect translation initiation and transcript stability by base-pairing with trans-encoded target mRNAs. Given that sRNAs frequently target multiple transcripts and that regulation can involve target repression or activation, it’s becoming increasingly clear that sRNAs can compete with transcription factors in terms of regulatory scope and function [

9]. In general, sRNAs have been classified into two types: trans-acting sRNAs that directly pair with mRNAs and Csr/Rsm-type sRNAs that sequester post-transcriptional regulatory proteins from target mRNAs [

10].

sRNA’s biological mechanism has been investigated thoroughly. These sRNAs are crucial for maintaining microbial cell homeostasis and controlling bacterial gene expression in response to external stress. The sRNA molecule either actively destroys the encoded proteins or halts their transcription by complementing binding to the C-terminus of RNase or a promoter region of a transcription factor [

11].

The “ESKAPE” pathogensare posing serious public consequences globally in the health facilities due to development of resistance to development and spread of resistant to most of the available antimicrobials. The development of novel antibacterial agents is essential to keep up with the constantly evolving resistance in bacteria. sRNAs influence antibiotic resistance by pairing with target mRNAs expressing drug efflux pumps, antibiotic transporters, or enzymes involved in drug catabolism [

6]. So this review highlights the gene regulation mechanisms underlying sRNA-mediated control of multidrug resistant pathogens and recent advances in sRNA-based therapy.

2. Overview of Small Non-Coding RNA in Bacteria

Small non-coding RNAs (sRNA) are short-sized ranging from 50–500 nucleotide transcripts that regulate post-transcriptionally gene expression [

12]. These sRNAs are synthesized under specific environmental conditions and play a major role in the regulation of various cellular processes [

13]. sRNAs can be encoded in the opposite strand of the target mRNA (known as antisense or cis sRNA), or encoded in trans to the target mRNA. The trans acting sRNA, or simply sRNAs, are RNA regulators frequently found in bacteria that interact by imperfect base pairing with its target mRNA [

1].

2.1. Types and Structures of sRNA

Because of their relative abundance in the bacterial cell, the first RNAs were found by chance as intriguing noncoding transcripts in biochemical or functional genetic screening. Numerous first sRNAs to be functionally identified were found on transposons, phages, and plasmids, where they were demonstrated to regulate transposition, maintenance, or replication [

14]. The abundant OmpR-dependent sRNA MicF was identified as the first chromosomally encoded sRNA that represses translation of an mRNA (encoding the OmpF porin), making it a prototype for environmental posttranscriptional regulation by sRNAs. The first sRNA shown to directly affect virulence, RNAIII of S. aureus was then revealed to regulate multiple virulence factor-encoding transcripts [

14].

Some of the small RNAs are fragments of mRNAs, whereas others are from intergenic regions of the genome. Exogenous dsRNAs can also induce the production of small RNAs [

15]. Recent studies have identified a large number of small regulatory RNAs in Escherichia coli and other bacteria [

16].

2.2. RNA Chaperones

In prokaryotes, Complementary base pairing between sRNAs and target RNAs assisted by RNA chaperones like

Hfq and

ProQ, in many occasions, to regulate the cognate gene expression is prevalent in sRNA mechanisms [

17].

Hfq was originally identified in

E. coli as a host factor required for the efficient replication of the RNA bacteriophage Qβ, Hfq is now understood to function as an RNA chaperone within bacterial cells [

18].

Hfq has been characterized as a member of the conserved RNA-binding

Lsm (like-Sm)/

Sm-like protein family found in eukaryotes, bacteria, and archaea. In recent years,

Hfq has gotten a lot of interest as it was discovered to serve a key role in sRNA-mediated gene regulation. It is necessary for successful sRNA stabilization and annealing to their mRNA targets [

19,

20].

Hfq can also protect sRNAs from degradation by ribonucleases [

21].

ProQ is another second known Gram-negative RNA chaperone protein that is crucial in modulating RNA-RNA interactions, like

Hfq. However,

ProQ is a monomeric protein with a predilection for structured RNAs, in contrast to hexametric

Hfq [

22].

Several of the base pairing sRNAs found in Gram-positive bacteria, such S. aureus, do not require Hfq to operate, even when the organism does contain

Hfq, in contrast to gram-negative bacteria [

23]. The absence of

Hfq in a number Gram-positive bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecium, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Streptococcus pyogenes of is due to low GC content (<50%). Remarkably, proteobacteria with a high GC content (≥50%) include Salmonella enterica and E. coli, two species where Hfq plays a significant role. Therefore, it was postulated that

Hfq’s function is most crucial for organisms with high GC content and that its role in sRNA-mediated regulation is related to the GC content of the genome [

24].

2.3. 6S RNA

Regulatory ncRNAs are involved in a variety of regulatory mechanisms, including gene expression and modulation of outer membrane surface proteins (Omp) [

25]. Some ncRNAs, like the 6S RNA that forms a complex with RNA polymerase, may bind to proteins to control their functions (RNAP). During the stationary phase, 6S RNA binds to the RNA polymerase (RNAP)-s70 complex and regulates transcription by changing RNAP’s promoter specificity [

26]. The abundant 6S RNA is conserved in Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria and its double-stranded RNA hairpin structure mimics DNA in an open promoter complex, allowing it to bind at the active site of σ70-RNA polymerase. In the stationary phase, 6S RNA accumulates to high levels, sequestering σ70-RNAP and favoring transcription by the RpoS-containing RNA polymerase. Upon transition from the stationary phase to the exponential phase, 6S RNA is released from the inhibited RNAP complex, resulting in the synthesis of a short transcript of 14 nt (pRNA), in which 6S RNA works as a template that requires a high NTP concentration. The formation of the pRNA–6S RNA complex induces a structural change that causes 6S to be released, which is subsequently removed by degradation [

27].

2.4. Orthogonality of sRNA

The specificity of sRNA interactions with their target mRNAs is referred to as orthogonality in the context of bacterial sRNAs. This implies that sRNA should not interact with other mRNAs in the cell, but only with its specific target mRNA. For bacteria to precisely regulate gene expression, orthogonal sRNA-mRNA interactions are essential [

28].

Several factors contribute to the orthogonality of bacterial sRNA-mRNA interactions:

Seed sequence: The seed sequence is a short stretch of nucleotides (typically 6-8 bases) at the 5’ end of the sRNA that is responsible for recognizing and binding to the target mRNA. The seed sequence should be unique to the target mRNA and not match other mRNAs in the cell [

29].

Target site accessibility: The target site on the mRNA, which is typically located in the ribosome binding site (RBS) or the coding region, should be accessible for sRNA binding. This means that the target site should not be folded into a secondary structure that prevents sRNA interaction [

30].

Complementary base pairing: The sRNA and its target mRNA should have complementary base pairing at the seed sequence and other regions of interaction to form a stable duplex [

31].

Hfq chaperone: The

Hfq chaperone protein plays a critical role in facilitating and stabilizing sRNA-mRNA interactions.

Hfq binds to both the sRNA and the target mRNA, bringing them into close proximity and promoting their interaction [

31].

Competing RNA molecules: The presence of competing RNA molecules, such as other sRNAs or mRNAs, can interfere with sRNA-mRNA interactions and reduce the orthogonality of sRNA regulation [

32].

The orthogonality of bacterial sRNA-mRNA interactions is essential for maintaining the precise control of gene expression and ensuring proper cellular function. Disruptions in sRNA orthogonality can lead to misregulation of gene expression and contribute to bacterial pathogenesis [

33]. The challenges of maintaining the orthogonality of sRNAs in bacteria are significant, but with careful engineering and design strategies, many of these issues can be effectively addressed. By leveraging bacterial mechanisms and synthetic biology tools, researchers can develop reliable, orthogonal sRNA systems that function independently, opening up new avenues for synthetic gene regulation and metabolic engineering (34). Summary of challenges in maintaining orthogonality of sRNAs in bacteria as illustrated in

Table 1.

3. Regulatory Mechanisms of sRNAs in Bacteria

Small RNAs regulate mRNAs via direct binding interactions between the sRNA and the target. Typically, sRNA binds to the 5′ end of the mRNA and prevents ribosomes from binding [

35]. Regulatory RNAs have the ablity to influence transcription, translation, mRNA stability, and DNA maintenance or silencing. They achieve these promising outcomes through a variety of mechanisms, including mRNA leaders that affect cis expression, small RNAs that bind to proteins or base pair with target RNAs [

36,

37].

3.1. Anti-Sense or Cis-Encoded sRNA

The

cis-encoded ncRNAs are found in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. They are encoded at the same locus as their target mRNA, but in the anti-sense of duplex, making them fully complementary during the interaction. The mechanism of the post-transcriptional response of gene regulation involves a high degree of sequence complementarity, which was thought to indicate that interaction of the Hfq protein would be unnecessary. These ncRNAs function by complementing the mRNA ribosome-binding site, thereby inhibiting translation [

37].

3.2. Trans-Encoded sRNA

Trans-encoded sRNA molecules exist on the chromosome in a different location than their targets and thus have only limited complementarity with them. Trans-acting sRNAs sequester the ribosome-binding site (RBS) of a target mRNA by base-pairing to the Shine–Dalgarno (SD) sequence or the start codon, and may also interact with the mRNAs’ coding sequence. Most of the previously identified trans- sRNAs are tightly coupled with the activity of RNases, which are enzymes involved in RNA turnover via RNA cleavage, to exploit their regulatory functions [

37].

4. Role of sRNA in Regulation of Antimicrobial Resistant Bacteria

The development of novel therapeutics to treat drug-resistant bacteria, particularly those caused by ESKAPE pathogens, is urgently needed [

38]. Recent evidence suggests that bacterial sRNAs play important roles in stress responses and the development of antibiotic resistance. Several sRNAs play roles in regulatory circuits that control antibiotic resistance. Evidence suggests that trans-encoded sRNAs play an important role in regulatory circuits that control antibiotic resistance. These networks control a variety of processes, including functions required for antibiotic uptake, modifications to the cell envelope that protect against antimicrobials), drug efflux pumps that expel antibiotics, metabolic enzymes that confer resistance, and the production of biofilms that protect against antibiotics [

39].

Growing evidence suggests that

cis-acting non-coding RNAs also play an important role in regulating the expression of many resistance genes, particularly those that protect against the effects of translation-inhibiting antibiotics. These ncRNAs reside in the regulated gene’s 5’ UTR and detect the presence of antibiotics by recruiting translating ribosomes to short upstream open reading frames (uORFs) embedded in the ncRNA. In the presence of translation-inhibiting antibiotics, ribosomes stall over the uORF, causing the regulator’s RNA structure to change and the expression of the resistance gene to switch to ‘ON’. Based on the length and composition of the respective uORF, the specificity of these ribo regulators is tuned to sense-specific classes of antibiotics [

40].

4.1. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus

Staphylococcus aureus is a major bacterial human pathogen responsible for a wide range of clinical symptoms. Infections are common in both community and hospital settings, and treatment is difficult to manage due to the emergence of multi-drug resistant strains such as MRSA (

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus [

41].

Because of the rapid spread of MRSA clones in healthcare settings, patients’ treatment options have been limited to a few last-line antibiotic classes. Severe MRSA infections are treated with glycopeptide antimicrobials, which inhibit peptidoglycan cell-wall synthesis.

Transcriptional factor

SpoVG is a master regulator of capsule production, virulence, and cell-wall metabolism, as well as a requirement for methicillin and glycopeptide resistance.

SpoVG regulates the l

ytSR operon as well as the glycine glycosyltransferase femAB, which create pentaglycine crosslinks between peptidoglycan strands. SpoVG also hurts the murein hydrolase

lytN. The highly conserved sRNA

SprX base pairs with the spoVG mRNA translation initiation site, preventing ribosome loading.

SpoVG is negatively regulated by sRNA

SprX, which appears to be expressed throughout the early, mid, and late exponential phases but is reduced in stationary growth has been shown to increase sensitivity to glycopeptides, most likely through

SpoVG-dependent cell-wall metabolism perturbations and

SpoVG-independent mechanisms [

42].

According to Eyraud et al.,

S. aureus sRNA

SprX (small pathogenicity island RNA X) shapes bacterial resistance to glycopeptide antibiotics and regulates

SpoVG expression. In fact,

SprX inhibits

SpoVG expression by interacting directly with a C-rich loop of

SprX and the

spoVG ribosomal binding site of yabJ-spoVG mRNA. This complex prevents ribosomal loading onto

spoVG and specifically inhibits translation of the second downstream gene within the yabJ-spoVG operon without affecting mRNA stability [

43].

4.2. Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is one of the most threatening multidrug-resistant pathogens in humans.

P. aeruginosa possesses a significant number of transcriptional regulators (approximately 10% of its genes) and hundreds of sRNAs interspersed throughout its genome, allowing it to adapt and survive in the host while resisting antimicrobial agents.Understanding genetic regulatory mechanisms is therefore critical for combating pathogenesis. The major porins OprD and OpdP are involved in the uptake of carbapenem antibiotics by

P. aeruginosa. In clinical multidrug-resistant isolates, oprD deletion increases carbapenem resistance. Both Sr0161 and ErsA suppress oprD expression to increase bacterial resistance to carbapenems by inhibiting the translation of oprD, whereas

Crc suppresses

oprdP expression [

42].

Sr006 was discovered to be a positive posttranscriptional regulator of the

pagL gene, which encodes the lipid A 3-O deacetylase, using a GRILseq approach. The acetylated form of lipid A has previously been shown to be pro-inflammatory, causing severe pulmonary damage in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients with chronic infection. Sr006 interacts with the 5’UTR of pagL mRNA in an

Hfq-independent manner, increasing

PagL levels and enhancing lipid A deacetylation of the LPS. As a result, polymyxin B susceptibility is increased [

44].

Overexpression of the previously unknown sRNA PA0805.1 in

P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 resulted in decreased motility, increased adherence, cytotoxicity, and tobramycin resistance. Under swarming conditions, however, a PA0805.1 deletion mutant was more susceptible to tobramycin [

45].

Among the numerous novels small RNAs that can be downregulated in Pseudomonas aeruginosa MDR clinical isolates, AS1974 was described as the master regulator to moderate the expression of several drug resistance pathways, including membrane transporters and biofilm-associated antibiotic-resistant genes, and its expression is regulated by methylation sites located at the gene’s 5′ UTR [

46].

4.3. Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase (ESBL)-Producing Enterobacterales

One function of the RNA-binding protein Hfq in

Enterobacterales is to facilitate the interaction of sRNA with their cognate mRNA targets [

47]. Gram-negative bacteria, such as

E. coli and

Salmonella, have an asymmetric outer membrane (OM) that is separated from the inner membrane by a periplasmic space containing peptidoglycan. The composition and assembly of OM components such as OMPs, lipoproteins, and LPSs are tightly controlled. This includes sRNA-mediated control mechanisms and cell envelope stress-responsive pathways that detect and respond to any dysfunction in the assembly or an imbalance in different cell envelope components [

48]. Although

E. coli sRNAs have varied functions, their mechanisms of action can be grouped into three broad categories: 1) RNAs that act via direct RNA–RNA basepairing (

OxyS, MicF, DicF and DsrA); 2) RNAs that act via RNA–protein interactions (

4.5S, CsrB, OxyS and DsrA); 3) and RNAs that have intrinsic activities (tmRNA and RNase P RNA). Some of these RNAs (

OxyS and

DsrA) appear to act by more than one mechanism on different targets [

49].

MicF, GcvB, and

RyhB are sRNAs that modulate antibiotic resistance in

E. coli.

MicF specifically regulates ompF expression by pairing with ompF mRNA, causing translation inhibition and mRNA degradation and, as a result, decreasing antibiotic permeability. Overexpression of

MicF in

E. coli increases cephalosporin, norfloxacin, and minocycline MICs, whereas depletion of this sRNA reverses those phenotypes, of except minocycline [

6,

39].

The regulatory role of

CsgD as the master regulator of biofilm formation in E. coli is critical for identifying the entire set of CsgD-regulated target genes and operons on the E. coli genome.

RybB is a major RpoE-dependent sRNA that is known to downregulate to inhibit

CsgD biosynthesis and thus the formation of biofilm [

50].

RpoE (encoded by the

rpoE gene), a specialized sigma factor (σ E), which is the founding member of the extracytoplasmic function sigma factor family, regulates periplasmic proteins necessary for protein folding or degradation and the machinery necessary for moving proteins through the inner membrane and inserting them in the outer membrane (51)

Klebsiella pneumoniae infections are heavily influenced by the capsular polysaccharide (CPS) and iron acquisition systems. Ferric uptake repressor (Fur) in bacteria can play a dual role in iron acquisition and CPS biosynthesis. Fur regulates transcription by binding to the promoter region of the small non-coding RNA

RyhB, which modulates cellular functions and virulence. Fur deletion increased

ryhB transcription [

51].

4.4. Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii

Treatment options for carbapenem-resistant

A. baumannii are limited, and the increased expression of chromosomal efflux pumps is a major concern [

52]. The action of efflux pumps (EPs), which extrude antibacterial agents from the cell before they can bind their target, is a primary mechanism governing antimicrobial resistance in

A. baumannii. A novel example of EP regulation in this organism is via sRNA AbsR25, which has been described as a species-specific, negative regulator implicated in fosfomycin efflux pump regulation (AbaF) and, as a result, antibiotic resistance; however, whether this regulation is direct or indirect remains unknown [

42]. Beyond sRNAs like AbsR25, other regulatory factors, such as transcription factors like AceR, also play a crucial role in mediating antibiotic resistance in

A. baumannii AceR is a new TF of the

LysR family, as being in charge of controlling the aceI chlorhexidine EP, which is a member of the EP family proteobacterial antimicrobial compound efflux (PACE).

AceR directly binds chlorohexidine in the form of an active dimer in

A. baumannii, which then binds to the intergenic region between

aceR and

aceI to induce the production of the

AceI EP [

53].

AbsR25 expression is highest during the exponential phase and decreases in fosfomycin-resistant mutants, which correlates with increased abaF mRNA. Both abaF disruption and overexpression suggest that it contributes to fosfomycin resistance. Despite being indirect, these findings indicate that AbsR25 most likely negatively regulates fosfomycin resistance. It most likely works by suppressing the production of genes associated with resistance mechanisms, which decreases the bacteria’s resistance to fosfomycin’s actions. This could entail inactivating enzymes that contribute to resistance or modifying efflux pumps. [

54].

4.5. Vancomycin Resistance Enterococcus faecium and E. faecalis

The main mechanism of glycopeptide resistance (e.g., vancomycin) in

Enterococci involves a change in the peptidoglycan synthesis pathway, specifically the substitution of D-Alanine-D-Alanine (D-Ala-D-Ala) for D-Alanine-D-Lactate (D-Ala-D-Lac) or D-Alanine-D-Serine (D-Ala-D-Serine) (D-Ala-DSer). Variable expressions of glycopeptide resistance can result from such changes. For example, when compared to the normal cell wall precursors D-Ala-D-Ala, the altered D-Ala-D-Lac and D-Ala-D-Ser have lower binding affinity for glycopeptide drugs. The ability to cause such changes is linked to several genes found on mobile genetic elements and/or chromosomally encoded regions of various Enterococcus species [

55].

Although no well-characterized sRNAs have been implicated in glycopeptide resistance in

E. faecium, E. faecium Aus0004, a clade A1 strain, has 61 sRNA candidates in its genome, although only a small number of them are engaged in glycopeptide resistance. Daptomycin treatment dramatically reduced the expression of one sRNA (sRNA_0160). Furthermore, in mutants resistant to daptomycin, sRNA_0160 was likewise markedly suppressed [

56].

5. High-Throughput Technologies for Identification of sRNA

The development of high-throughput RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) techniques has hastened the discovery of sRNA. It has fundamentally altered the understanding of bacterial virulence and pathogenicity, with sRNAs emerging as an important, distinct class of virulence factors in both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria [

57]. Several high-throughput techniques have enabled the identification of sRNAs in bacteria, but experimental detection remains difficult and grossly incomplete for the vast majority of species. As a result, computational tools for predicting bacterial sRNAs are required.

Barman et al proposed a computational method for identifying sRNAs in bacteria using a support vector machine (SVM) classifier, which was validated with

E. coli sRNA and

Salmonella Typhi model [

58].

A computational method based on transcriptional signals to identify intergenic sRNA transcriptional units (TUs) in fully sequenced bacterial genomes. The sRNAscanner tool identifies intergenic sRNA TUs using sliding window-based genome scans and position weight matrices derived from experimentally defined E. coli K-12 MG1655 sRNA promoter and rho-independent terminator signals [

59].

The GLobal Automatic Small RNA Search go (GLASSgo) algorithm is used to find sRNA homologs in large genomic databases starting with a single sequence. GLASSgo combines iterative BLAST with pairwise identity filtering and a graph-based clustering method based on RNA secondary structure information [

60].

6. Therapeutic Strategies of sRNA

6.1. Stability of sRNA

An important determinant of sRNA molecules’ therapeutic efficiency is their stability. Non-coding RNA molecules, or sRNAs, are crucial for controlling the expression of certain genes. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) are the two primary categories into which they can be classified. siRNAs are exogenously inserted RNAs that precisely target complimentary mRNAs for degradation, whereas miRNAs are endogenous RNAs that usually target coding mRNAs for degradation or translational suppression [

61]. Several strategies can be used to improve the stability of sRNAs include: Chemical modifications to sRNA bases, such as methylation and pseudouridylation, can increase sRNA stability by protecting them from degradation by RNases (56), encapsulating sRNAs in liposomes or nanoparticles can protect them from degradation and improve their delivery to target cells [

62], designing sRNAs with specific structural features, such as stem-loop structures, can increase their stability [

63].

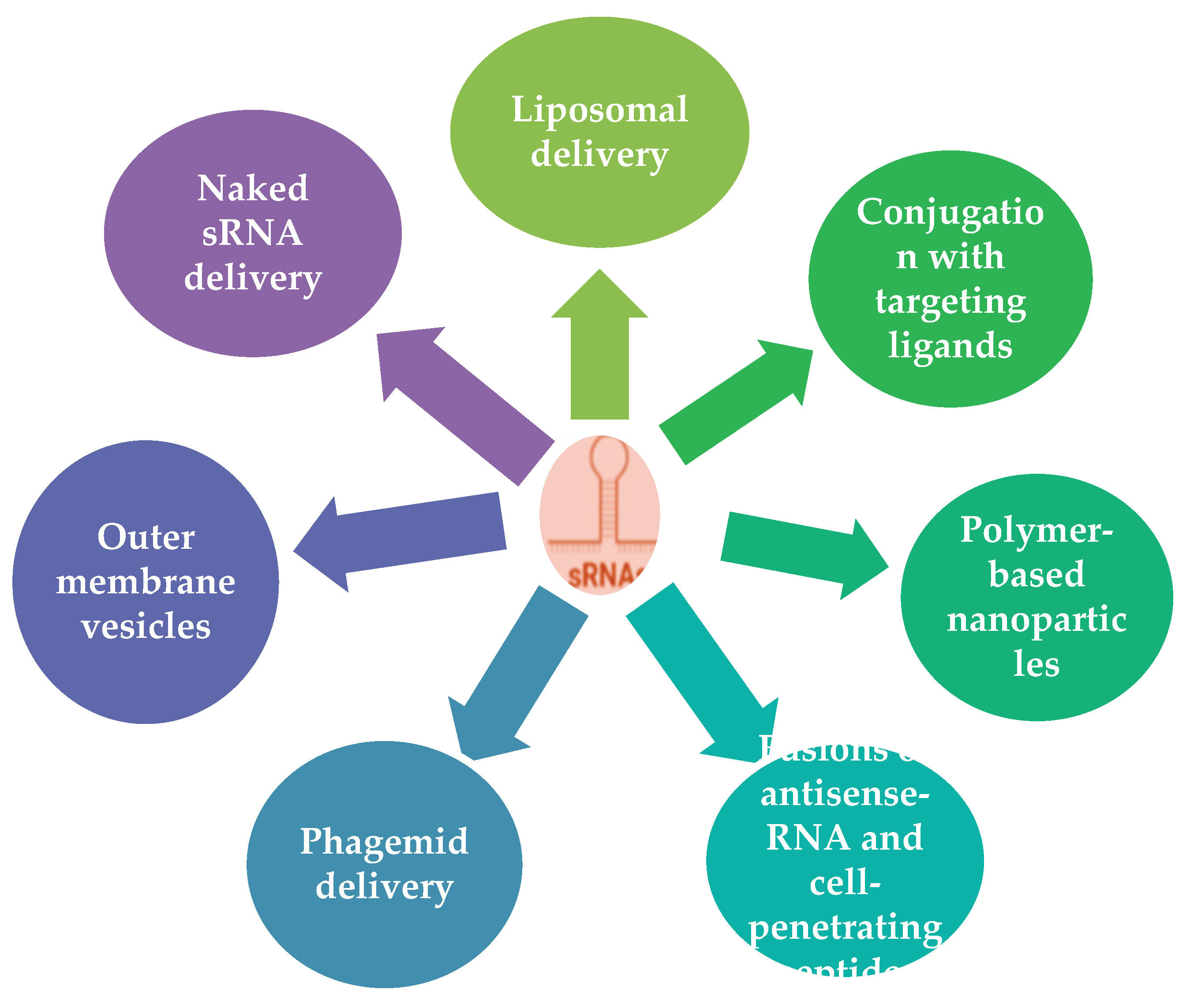

6.2. sRNA Delivery to Target Cell

mRNA vaccines have tremendous potential for SARS-CoV2 vaccines to fight against COVID 19. It was a promising new approach to vaccine development that could provide more effective, safe, and durable protection against SARS-CoV2 and other viral infections [

64]. The delivery of sRNAs to fight AMR is still in its early stages of development, but the potential benefits of this approach are significant. There are several different methods for delivering sRNAs to bacteria, including:

Naked sRNA delivery: This method involves the direct injection of naked sRNAs into bacteria. However, naked sRNAs are intrinsically susceptible to the cleavage and degradation by a variety of circulating ribonucleases (RNases) and hydrolases, and thus rapidly eliminated through renal clearance [

65].

Liposomal delivery: Liposomes are spherical vesicles composed of phospholipids that can encapsulate sRNAs and protect them from degradation. Liposomal delivery can enhance sRNA stability and facilitate cellular uptake, improving therapeutic effectiveness [

66],

Polymer-based nanoparticles: Polymer-based nanoparticles, such as poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles, can also encapsulate sRNAs and provide sustained release. This approach offers better control over sRNA release kinetics and can improve therapeutic outcomes [

67].

Conjugation with targeting ligands: Attaching targeting ligands, such as antibodies or peptides, to sRNAs can direct them to specific bacteria, enhancing their specificity and therapeutic efficacy [

68].

Outer membrane vesicles (OMVs): OMVs are naturally occurring vesicles derived from the outer membrane of bacteria. They can be engineered to encapsulate and deliver sRNAs to target bacteria [

69].

Phagemid vector delivery: Small regulatory asRNAs often contain an

Hfq-binding sequence that down regulates the expression of a specific gene to produce a novel antimicrobial tool using a small (140 nucleotide) RNA with 24-nucleotide antisense (as) region from phagemid vector in

E. coli. Knockdown effects of

rpoS encoding RNA polymerase sigma factor were observed. asRNAs targeting several essential

E. coli genes produced significant growth defects, especially when targeted to

acpP and ribosomal protein-coding genes

rplN, rplL, and

rpsM. Growth inhibited phenotypes were facilitated in hfq- conditions. Phage lysates were prepared from cells harboring phagemids as a lethal-agent delivery tool. Targeting the

rpsM gene by phagemid-derived M13 phage infection of

E. coli containing a carbapenem-producing F-plasmid and multidrug-resistant

Klebsiella pneumoniae containing an F-plasmid resulted in the death of over 99.99% of infected bacteria [

70,

71].

Fusions of antisense-RNA and cell-penetrating peptides: Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs), a class of short peptides with a unique ability to pierce cell membranes, are one of the many delivery technologies that hold tremendous promise for the intracellular administration of a variety of physiologically active payloads [

72].

The fusion of antisense-RNA (asRNA) and cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) has emerged as a promising strategy for the development of novel antimicrobials against pathogenic bacteria. asRNA molecules can specifically target and silence essential bacterial genes, while CPPs facilitate the cellular uptake of asRNA, enabling its intracellular delivery and silencing of target genes [

73].One common strategy involves conjugating the asRNA molecule to a CPP sequence. This conjugation facilitates the cellular uptake of asRNA by exploiting the CPP’s ability to penetrate cell membranes. Another approach involves co-formulation of asRNA and CPPs in a delivery system, such as nanoparticles or liposomes. This approach can protect the asRNA from degradation and enhance its stability in biological fluids [

74]. Studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of asRNA-CPP conjugates and co-formulations against various pathogenic bacteria, including S. aureus, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa. These studies have shown that asRNA-CPP combinations can effectively inhibit bacterial growth and virulence [

75]. The summary of strategies of sRNA delivery to cell [

Figure 1].

7. Advantage and Disadvantage of sRNAs Drug

Whether or not sRNAs would be a competitive drug in terms of the cost of antibiotics is difficult to say at this stage. The cost of sRNA-based drugs will likely depend on a number of factors, including the cost of production, the complexity of the delivery method, and the length of treatment [

76].

In general, sRNA-based drugs are likely to be more expensive than traditional antibiotics. This is because sRNAs are more complex molecules to produce and deliver than traditional antibiotics. Additionally, sRNA-based drugs may need to be administered for a longer duration than traditional antibiotics, which would increase the overall cost of treatment. However, the cost of sRNA-based drugs may be justified by their potential benefits. sRNA-based drugs have several advantages over traditional antibiotics, including: high specificity, versatility, durability and can be combined with other therapeutic modalities, such as chemotherapy or immunotherapy, to enhance treatment outcomes [

77,

78].However in terms of accessibility, sRNAs are likely to be initially limited to developed countries. This is because the cost of sRNA-based drugs is likely to be highest in these countries. Additionally, the infrastructure for developing and testing sRNA-based drugs is more advanced in developed countries [

79].

8. Conclusion and Future Perspective

The use of small RNAs represents an untapped source of potential molecules for antibacterial design. Our understanding of gene regulation has been transformed by the recent discovery of sRNAs as a general class of powerful regulators. In response to stress or when cells are exposed to antibiotics, sRNAs are involved in a variety of cellular processes. Uncovering the roles of sRNAs in virulence and host immunity will provide fundamental knowledge that can be used to develop next-generation antibiotics that use sRNAs as original targets. However, many questions about RNA biology remain unanswered, but we are confident that sRNA-based therapeutic treatment of infectious diseases will become useful tools future shortly. To develop safe, effective, and affordable sRNA therapeutics for a wide range of bacterial infections, developing effective novel delivery methods, improving sRNA stability, and understanding the mechanisms of resistance, sRNA-based therapies have the potential to revolutionize the treatment of AMR.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.A., A.B., E.G, T.E and A.F.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.A, A.F, H.M., J.B., M.K.L., S.K., A.S., N.H. and S.M.G.; writing—review and editing, A.B and E.G.,.; supervision, A.F and T. E. All authors have read and approved to the published the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Parmeciano Di Noto, Gisela, María Carolina Molina, and Cecilia Quiroga. Insights into non-coding RNAs as novel antimicrobial drugs. Front Genet. 2019, 10, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.J.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Aguilar, G.R.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; Johnson, S.C. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. The Lancet. 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.K.; Hussein, S.; Qurbani, K.; Ibrahim, R.H.; Fareeq, A.; Mahmood, K.A.; Mohamed, M.G. Antimicrobial resistance: Impacts, challenges, and future prospects. Journal of Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health. 2024, 2, 100081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattoir, V.; Felden, B. Future antibacterial strategies: From basic concepts to clinical challenges. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 220, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, A.; Bush, N.G.; Germe, T.; McKie, S.J. Non-quinolone topoisomerase inhibitors. Antimicrobial Resistance in the 21st Century. 2018, 593–618. [Google Scholar]

- Felden, B.; Cattoir, V. Bacterial adaptation to antibiotics through regulatory RNAs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, 10–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, C.A.; Vincent, H.A.; Callaghan, A.J. Reprogramming gene expression by targeting RNA-based interactions: A novel pipeline utilizing RNA array technology. ACS Synthetic Biology. 2021, 10, 1847–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgmann, J.; Schäkermann, S.; Bandow, J.E.; Narberhaus, F. A small regulatory RNA controls cell wall biosynthesis and antibiotic resistance. MBio 2018, 9, 10–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyos, M.; Huber, M.; Förstner, K.U.; Papenfort, K. Gene autoregulation by 3’UTR-derived bacterial small RNAs. eLife 2020, 9, e58836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djapgne, L.; Oglesby, A.G. Impacts of small RNAs and their chaperones on bacterial pathogenicity. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.; Ho, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Wong, S.H.; Chan, M.T.; Wu, W.K. Potential and use of bacterial small RNAs to combat drug resistance: A systematic review. Infect Drug Resist. 2017, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Elena, R.C.; Marquez, P.H. The roles of small RNAs: Insights from bacterial quorum sensing. ExRNA 2019, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalaouna, D.; Eyraud, A.; Chabelskaya, S.; Felden, B.; Masse, E. Regulatory RNAs involved in bacterial antibiotic resistance. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svensson, S.L.; Sharma, C.M. Small RNAs in bacterial virulence and communication. Virulence Mechanisms of Bacterial Pathogens. 5th edition. 2016, 169–212. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, J.F.; Micheva-Viteva, S.; Li, N.; Hong-Geller, E. Small RNA-mediated regulation of host–pathogen interactions. Virulence. 2013, 4, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani-Fard, E.; Taghvimi, S.; Abedi Kichi, Z.; Weber, C.; Shabaninejad, Z.; Taheri-Anganeh, M.; et al. Insights into the Function of Regulatory RNAs in Bacteria and Archaea. J Transl Med. 2021, 1, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, T.; Srivastava, S. Small RNA-mediated regulation in bacteria: A growing palette of diverse mechanisms. Gene. 2018, 656, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavita, K.; de Mets, F.; Gottesman, S. New aspects of RNA-based regulation by Hfq and its partner sRNAs. Current opinion in microbiology. 2018, 42, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lay, N.; Schu, D.J.; Gottesman, S. Bacterial small RNA-based negative regulation: Hfq and its accomplices. J Biol Chem. 2013, 288, 7996–8003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, D.; Arya, D.P. Regulatory roles of small RNAs in prokaryotes: Parallels and contrast with eukaryotic mirna. Non-coding RNA Investig. 2019, 3, 21037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dendooven, T.; Sinha, D.; Roeselová, A.; Cameron, T.A.; De Lay, N.R.; Luisi, B.F.; Bandyra, K.J. A cooperative PNPase-Hfq-RNA carrier complex facilitates bacterial riboregulation. Molecular Cell. 2021, 81, 2901–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westermann, A.J.; Venturini, E.; Sellin, M.E.; Förstner, K.U.; Hardt, W.D.; Vogel, J. The major RNA-binding protein ProQ impacts virulence gene expression in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. MBio. 2019, 10, 10–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottesman, S.; Storz, G. Bacterial small RNA regulators: Versatile roles and rapidly evolving variations. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2011, 3, a003798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christopoulou, N.; Granneman, S. The role of RNA-binding proteins in mediating adaptive responses in Gram-positive bacteria. The FEBS journal. 2022, 289, 1746–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matera, G.; Altuvia, Y.; Gerovac, M.; El Mouali, Y.; Margalit, H.; Vogel, J. Global RNA interactome of Salmonella discovers a 5′ UTR sponge for the MicF small RNA that connects membrane permeability to transport capacity. Mol. Cell. 2022, 82, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warrier, I.; Hicks, L.D.; Battisti, J.M.; Raghavan, R.; Minnick, M.F. Identification of novel small RNAs and characterization of the 6S RNA of Coxiella burnetii. PLoS ONE. 2014, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, G.; Raina, S. Small regulatory bacterial regulating the envelope stress response. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2017, 45, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, Y.; Abe, K.; Nakashima, S.; Yoshida, W.; Ferri, S.; Sode, K.; Ikebukuro, K. Improving the gene-regulation ability of small RNAs by scaffold engineering in Escherichia coli. ACS Synth. Biol. 2014, 3, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Tian, S.; Ui-Tei, K. The siRNA off-target effect is determined by base-pairing stabilities of two different regions with opposite effects. Genes. 2022, 13, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, D.; Vanderpool, C.K. New developments in post-transcriptional regulation of operons by small RNAs. RNA biology. 2013, 10, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekzema, M.; Romilly, C.; Holmqvist, E.; Wagner, E.G.H. Hfq-dependent mRNA unfolding promotes sRNA-based inhibition of translation. EMBO J. 2019, 38, e101199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villa, J.K.; Su, Y.; Contreras, L.M.; Hammond, M.C. Synthetic Biology of Small RNAs and Riboswitches. Microbiol Spectr. 2018, 6, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Ignatov, D.; Vaitkevicius, K.; Durand, S.; Cahoon, L.; Sandberg, S.S.; Liu, X.; Kallipolitis, B.H.; Rydén, P.; Freitag, N.; Condon, C.; Johansson, J. An mRNA-mRNA interaction couples expression of a virulence factor and its chaperone in Listeria monocytogenes. Cell reports. 2020, 30, 4027–4040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J.P.; Silva, A.F.; Arraiano, C.M.; Andrade, J.M. Bacterial Small RNAs: Diversity of Structure and Function. InRNA Structure and Function. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2023, 259-277.

- Storz, G.; Vogel, J.; Wassermann, K.M. Regulation by small RNAs in bacteria: Expanding frontiers. Molecular cell. 2011, 43, 880–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, L.S.; Storz, G. Regulatory RNAs in bacteria. Cell. 2009, 136, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González Plaza, J.J. Small RNAs as fundamental players in the transference of Information during Bacterial Infectious Diseases. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Ying, X.; Lu, Q.; Chen, L. Predicting sRNAs and their targets in bacteria. Genomics Proteomics and Bioinformatics 2012, 10, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulani, M.S.; Kamble, E.E.; Kumkar, S.N.; Tawre, M.S.; Pardesi, K.R. Emerging strategies to combat ESKAPE pathogens in the era of antimicrobial resistance: A review. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dersch, P.; Khan, M.A.; Mühlen, S.; Görke, B. Roles of regulatory RNAs for antibiotic resistance in bacteria and their potential value as novel drug targets. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, D.; Sorek, R. Regulation antibiotics resist distance by non-coding RNAs in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2017, 36, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, B.M.A.K.; Easwaran, N.; Gothandam, K.M. Staphylococcus aureus and Virulence-Related Small RNA. Insights into Drug Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. IntechOpen. 2021, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Mediati, D.G.; Wu, S.; Wu, W.; Tree, J.J. Networks of resistance: Small RNA control of antibiotic resistance. Trends Genet. 2021, 37, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyraud, A.; Tattevin, P.; Chabelskaya, S.; Felden, B. A small RNA controls a protein regulator involved in antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 4892–4905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusic, P.; Sonnleitner, E.; Bläsi, U. Specific and global RNA regulators in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, S.R.; Smith, M.L.; Spicer, V.; Lao, Y.; Mookherjee, N.; Hancock, R.E. Overexpression of the small RNA PA0805. 1 in Pseudomonas aeruginosa modulates the expression of a large set of genes and proteins, resulting in altered motility, cytotoxicity, and tobramycin resistance. Msystems. 2020, 5, 10–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, C.O.K.; Huang, C.; Pan, Q.; Lee, J.; Hao, Q.; Chan, T.F.; Lo, N.W.S.; et al. A Small RNA transforms the multidrug resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to drug susceptibility. Molecular Therapy Nucleic Acids 2019, 16, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröger, C.; MacKenzie, K.D.; Alshabib, E.Y.; Kirzinger, M.W.B.; Suchan, D.M.; Chao, T.; et al. The primary transcriptome, small RNAs, and regulation of antimicrobial resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 17978. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 9684–9698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, G.; Raina, S. Small regulatory bacterial regulating the envelope stress response. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2017, 45, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montzka Wassarman, K.; Zhang, A.; Storz, G. Small RNAs in Escherichia coli. Trends.Microbiol 1999, 7, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, P.R.; Pettersen, J.S.; Szczerba, M.; Valentin-hansen, P.; Møller-jensen, J.; Jørgensen, M.G. sRNA-dependent control of curli biosynthesis in Escherichia coli: McaS directs endonucleolytic cleavage of csgD, m.R.N.A. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 6746–6760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.H.; Wang, C.K.; Peng, H.L.; Wu, C.C.; Chen, Y.T.; Hong, Y.M.; Lin, C.T. Role of the small RNA RyhB in the fur regulon in mediating the capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis and iron acquisition systems in Klebsiella pneumoniae. BMC Microbiol. 2012, 12, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyriakidis, I.; Vasileiou, E.; Pana, Z.D.; Tragiannidis, A. Acinetobacter baumannii antibiotic resistance mechanisms. Pathogens. 2021, 10, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, J.L.; Tomlinson, B.R.; Casella, L.G.; Shaw, L.N. Regulatory networkswork important for the survival of Acinetobacter baumannii within the host. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2020, 55, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Arya, S.; Patil, S.D.; Sharma, A.; Jain, P.K.; Navani, N.K.; Pathania, R. Identification of novel regulatory small RNAs in Acinetobacter baumannii. PLoS ONE 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M.O.; Baptiste, K.E. Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci: A Review of Antimicrobial Resistance Mechanisms and Perspectives of Human and Animal Health. Microb. Drug Resist. 2018, 24, 590–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinel, C.; Augagneur, Y.; Sassi, M.; Bronsard, J.; Cacaci, M.; Guérin, F.; et al. Small RNAs in vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium involved in daptomycin response and resistance. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 11067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, I. Provost PRNA-sequencing analyses of small bacterial RNAs their emergence host pathogen- factors in host pathogen interactions. Int J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, R.K.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Das, S. An improved method for identification of small non-coding RNAs in bacteria using support vector machine. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, J.; Narmada, S.R.; Sabarinathan, R.; Ou, H.Y.; Deng, Z.; Sekar, K.; et al. sRNAscanner: A computational tool for intergenic small RNA detection in bacterial genomes. PLoS ONE 2010, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lott, S.C.; Schäfer, R.A.; Mann, M.; Backofen, R.; Hess, W.R.; Voß, B.; Georg, J. GLASSgo - Automated and reliable detection of sRNA homologs from a single input sequence. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Zhong, L.; Weng, Y.; Peng, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liang, X.J. Therapeutic siRNA: State of the art. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020, 5, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, R.P.; Mukherjee, R.; Chang, C.M. Emerging concern with imminent therapeutic strategies for treating resistance in biofilm. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yin, G.; Weng, H.; Zhang, L.; Du, G.; Chen, J.; Kang, Z. Gene knockdown by structure defined single-stem loop small non-coding RNAs with programmable regulatory activities. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2023, 8, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, J.; Han, X.; Wei, Y.; Wei, X. mRNA vaccine: A potential therapeutic strategy. Mol. Cancer. 2021, 20, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, A.M.; Tu, M.J. Deliver the promise: RNAs as a new class of molecular entities for therapy and vaccination. Pharmacol Ther. 2022, 230, 107967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williford, J.M.; Wu, J.; Ren, Y.; Archang, M.M.; Leong, K.W.; Mao, H.Q. Recent advances in nanoparticle-mediated siRNA delivery. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2014, 16, 347–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; Fu, D.; Utupova, A.; Sun, D.; Zhou, M.; Jin, Z.; Zhao, K. Applications of polymer-based nanoparticles in vaccine field. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2019, 8, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, N.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, X.; Yan, Z.; Shao, G.; Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Fu, C. Therapeutic peptides: Current applications and future directions. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koeppen, K.; Hampton, T.H.; Jarek, M.; Scharfe, M.; Gerber, S.A.; Mielcarz, D.W.; Demers, E.G.; Dolben, E.L.; Hammond, J.H.; Hogan, D.A.; Stanton, B.A. A novel mechanism of host-pathogen interaction through sRNA in bacterial outer membrane vesicles. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Ishimoto, T.; Fujita, S.; Kiryu, S.; Wada, M.; Akatsuka, T.; et al. Antimicrobial antisense RNA delivery to F-pili producing multidrug-resistant bacteria via a genetically engineered bacteriophage. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 530, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libis, V.K.; Bernheim, A.G.; Basier, C.; Jaramillo-Riveri, S.; Deyell, M.; Aghoghogbe, I.; Atanaskovic, I.; Bencherif, A.C.; Benony, M.; Koutsoubelis, N.; Löchner, A.C. Silencing of antibiotic resistance in E. coli with engineered phage bearing small regulatory RNAs. ACS Synth. Biol. 2014, 3, 1003–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghian, I.; Heidari, R.; Sadeghian, S.; Raee, M.J.; Negahdaripour, M. Potential of cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) in delivery of antiviral therapeutics and vaccines. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2022, 169, 106094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, M.; Nielsen, P.E.; Good, L. Cell Permeabilization and Uptake of Antisense Peptide-Peptide Nucleic Acid (PNA) into Escherichia Coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 7144–7147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gooding, M.; Malhotra, M.; Evans, J.C.; Darcy, R.; O’Driscoll, C.M. Oligonucleotide conjugates–Candidates for gene silencing therapeutics. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2016, 107, 321–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, P.E.; Shiraishi, T. Peptide nucleic acid (PNA) cell penetrating peptide (CPP) conjugates as carriers for cellular delivery of antisense oligomers. Artificial Dna Pna Xna 2011, 2, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, A.M.; Choi, Y.H.; Tu, M.J. RNA drugs and RNA targets for small molecules: Principles, progress, and challenges. Pharmacol Res. 2020, 72, 862–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattoir, V.; Felden, B. Future Antibacterial Strategies: From Basic Concepts to Clinical Challenges. J Infect Dis. 2019, 220, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, N.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, X.; Yan, Z.; Shao, G.; Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Fu, C. Therapeutic peptides: Current applications and future directions. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).