Submitted:

09 May 2025

Posted:

12 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

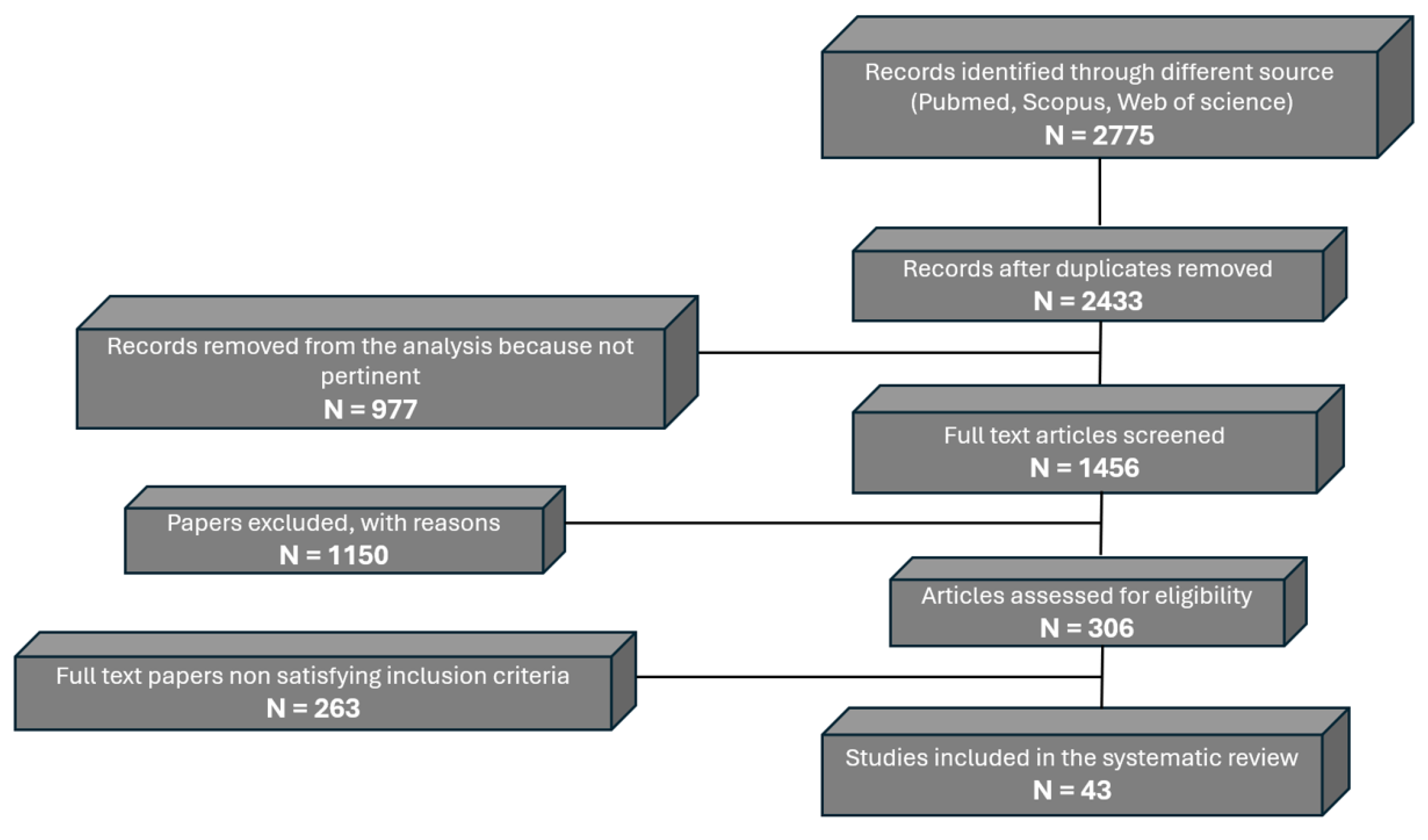

2. Methods

2.1. Sources

2.2. Study Selection

- Design: Original research articles including observational studies, clinical trials, case reports, and technical method evaluations; reviews and small cohort studies were excluded.

- Patient inclusion criteria: Human males with infertility of various etiologies, including idiopathic infertility and metabolic-related dysfunctions affecting sperm quality.

- Patient exclusion criteria: Review articles, studies involving animal models; male infertility with well-established causes such as varicocele, cryptorchidism, infections of male accessory glands, genetic abnormalities (e.g., Y chromosome microdeletions), testicular torsion or trauma, and systemic diseases including thyroid, pituitary, adrenal disorders, kidney or liver failure.

- Study intervention: Application or evaluation of diagnostic or research tools and techniques aimed at identifying biomarkers or characterizing sperm metabolic pathways and developmental processes.

- Study outcome: Assessment of the utility, accuracy, and relevance of advanced methods and emerging technologies for evaluating sperm metabolism and their usefulness in diagnosing or understanding metabolic sperm-related infertility.

3. Results

4. Energy Metabolism Pathways in Spermatozoa

5. Energy Metabolism Pathways in Spermatozoa

5.1. Metabolic Substrates and Transport

5.2. Metabolic Adaptations During Maturation and Transit

6. Molecular Biomarkers and Oxidative Stress

7. Influence of the Seminal Microbiome

8. Advanced Techniques and Tools for Evaluating Sperm Metabolism

9. Clinical Implications: Metabolic Dysfunction in Male Infertility

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- R. Bohnensack and W. Halangk, “Control of respiration and of motility in ejaculated bull spermatozoa,” Biochim Biophys Acta, vol. 850, no. 1, pp. 72–79, Jun. 1986. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Du Plessis, A. Agarwal, J. Halabi, and E. Tvrda, “Contemporary evidence on the physiological role of reactive oxygen species in human sperm function,” J Assist Reprod Genet, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 509–520, Apr. 2015. [CrossRef]

- P. E. Visconti, “Sperm bioenergetics in a nutshell,” Biol Reprod, vol. 87, no. 3, p. 72, Sep. 2012. [CrossRef]

- R. Sciorio and S. D. Fleming, “Intracytoplasmic sperm injection vs. in-vitro fertilization in couples in whom the male partners had a semen analysis within normal reference ranges: An open debate,” Andrology, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 20–29, 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. Ombelet et al., “Now is the time to introduce new innovative assisted reproduction methods to implement accessible, affordable, and demonstrably successful advanced infertility services in resource-poor countries,” Human Reproduction Open, vol. 2025, no. 1, p. hoaf001, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- “Infertility.” Accessed: Apr. 17, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/factsheets/detail/infertility.

- Agarwal, A. Mulgund, A. Hamada, and M. R. Chyatte, “A unique view on male infertility around the globe,” Reprod Biol Endocrinol, vol. 13, p. 37, Apr. 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Amaral, J. Castillo, J. M. Estanyol, J. L. Ballesca, J. Ramalho-Santos, and R. Oliva, “Human sperm tail proteome suggests new endogenous metabolic pathways,” Molecular and Cellular Proteomics, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 330–342, 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. He et al., “Association between semen microbiome disorder and sperm DNA damage.,” Microbiol Spectr, vol. 12, no. 8, p. e0075924, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. Milardi et al., “Novel Biomarkers of Androgen Deficiency From Seminal Plasma Profiling Using High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry,” JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGY & METABOLISM, vol. 99, no. 8, pp. 2813–2820, Aug. 2014. [CrossRef]

- R. Sharma et al., “Functional proteomic analysis of seminal plasma proteins in men with various semen parameters,” REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY AND ENDOCRINOLOGY, vol. 11, May 2013. [CrossRef]

- R. Sharma et al., “Proteomic analysis of human spermatozoa proteins with oxidative stress,” REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY AND ENDOCRINOLOGY, vol. 11, May 2013. [CrossRef]

- Quijano, M. Trujillo, L. Castro, and A. Trostchansky, “Interplay between oxidant species and energy metabolism,” Redox Biology, vol. 8, pp. 28–42, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Tombes and B. M. Shapiro, “Metabolite channeling: a phosphorylcreatine shuttle to mediate high energy phosphate transport between sperm mitochondrion and tail,” Cell, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 325–334, May 1985. [CrossRef]

- W. C. L. Ford, “Glycolysis and sperm motility: does a spoonful of sugar help the flagellum go round?,” Hum Reprod Update, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 269–274, 2006. [CrossRef]

- T. Mann, “Fructose, a Constituent of Semen,” Nature, vol. 157, no. 3977, pp. 79–79, Jan. 1946. [CrossRef]

- G. Frenette, C. G. Frenette, C. Lessard, E. Madore, M. A. Fortier, and R. Sullivan, “Aldose Reductase and Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor Are Associated with Epididymosomes and Spermatozoa in the Bovine Epididymis1,” Biology of Reproduction, vol. 69, no. 5, pp. 1586–1592, Nov. 2003. [CrossRef]

- T. Rigau et al., “Differential effects of glucose and fructose on hexose metabolism in dog spermatozoa,” Apr. 2002. [CrossRef]

- F. Burant, J. F. Burant, J. Takeda, E. Brot-Laroche, G. I. Bell, and N. O. Davidson, “Fructose transporter in human spermatozoa and small intestine is GLUT5.,” Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 267, no. 21, pp. 14523–14526, Jul. 1992. [CrossRef]

- Bucci, J. E. Rodriguez-Gil, C. Vallorani, M. Spinaci, G. Galeati, and C. Tamanini, “GLUTs and Mammalian Sperm Metabolism,” Journal of Andrology, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 348–355, 2011. [CrossRef]

- T. E. King and T. R. R. Mann, “Sorbitol metabolism in spermatozoa,” Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B. Biological Sciences, vol. 151, no. 943, pp. 226–243, Jan. 1997. [CrossRef]

- W. Cao, H. K. W. Cao, H. K. Aghajanian, L. A. Haig-Ladewig, and G. L. Gerton, “Sorbitol Can Fuel Mouse Sperm Motility and Protein Tyrosine Phosphorylation via Sorbitol Dehydrogenase1,” Biology of Reproduction, vol. 80, no. 1, pp. 124–133, Jan. 2009. [CrossRef]

- C. R. Darr, D. D. C. R. Darr, D. D. Varner, S. Teague, G. A. Cortopassi, S. Datta, and S. A. Meyers, “Lactate and Pyruvate Are Major Sources of Energy for Stallion Sperm with Dose Effects on Mitochondrial Function, Motility, and ROS Production1,” Biology of Reproduction, vol. 95, no. 2, pp. 34, 1–11, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- P. Halestrap and N. T. Price, “The proton-linked monocarboxylate transporter (MCT) family: structure, function and regulation,” Biochem J, vol. 343 Pt 2, no. Pt 2, pp. 281–299, Oct. 1999.

- J. Lee, D. R. Lee, and S. Lee, “The genetic variation in Monocarboxylic acid transporter 2 (MCT2) has functional and clinical relevance with male infertility,” Asian Journal of Andrology, vol. 16, no. 5, p. 694, Oct. 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. Blanco and W., H. Zinkham, “Lactate Dehydrogenases in Human Testes,” Science, vol. 139, no. 3555, pp. 601–602, Feb. 1963. [CrossRef]

- Swegen, B. J. Curry, Z. Gibb, S. R. Lambourne, N. D. Smith, and R. J. Aitken, “Investigation of the stallion sperm proteome by mass spectrometry,” Mar. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhu et al., “Exogenous Oleic Acid and Palmitic Acid Improve Boar Sperm Motility via Enhancing Mitochondrial Β-Oxidation for ATP Generation,” Animals, vol. 10, no. 4, Art. no. 4, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Md. M. Islam, T. Umehara, N. Tsujita, and M. Shimada, “Saturated fatty acids accelerate linear motility through mitochondrial ATP production in bull sperm,” Reproductive Medicine and Biology, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 289–298, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Amaral, B. Lourenço, M. Marques, and J. Ramalho-Santos, “Mitochondria functionality and sperm quality,” Reproduction, vol. 146, no. 5, pp. R163-174, 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. Ballester et al., “Evidence for a functional glycogen metabolism in mature mammalian spermatozoa,” Molecular Reproduction and Development, vol. 56, no. 2, pp. 207–219, 2000. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Palomo, J. M. FernÁndez-Novell, A. Peña, J. J. Guinovart, T. Rigau, and J. E. Rodríguez-Gil, “Glucose- and fructose-induced dog-sperm glycogen synthesis shows specific changes in the location of the sperm glycogen deposition,” Molecular Reproduction and Development, vol. 64, no. 3, pp. 349–359, 2003. [CrossRef]

- J. Losano et al., “Effect of mitochondrial uncoupling and glycolysis inhibition on ram sperm functionality,” Reproduction in Domestic Animals, vol. 52, no. 2, pp. 289–297, 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. R. Moraes et al., “Effect of glucose concentration and cryopreservation on mitochondrial functions of bull spermatozoa and relationship with sire conception rate,” Animal Reproduction Science, vol. 230, p. 106779, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. A. Bulkeley et al., “Effects from disruption of mitochondrial electron transport chain function on bull sperm motility,” Theriogenology, vol. 176, pp. 63–72, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Balbach et al., “Capacitation induces changes in metabolic pathways supporting motility of epididymal and ejaculated sperm,” Front. Cell Dev. Biol., vol. 11, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S.-K. Jin and W.-X. Yang, “Factors and pathways involved in capacitation: how are they regulated?,” Oncotarget, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 3600–3627, Sep. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Tourmente, E. M. Tourmente, E. Sansegundo, E. Rial, and E. R. S. Roldan, “Capacitation promotes a shift in energy metabolism in murine sperm,” Front. Cell Dev. Biol., vol. 10, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Mateo-Otero et al., “Sperm physiology and in vitro fertilising ability rely on basal metabolic activity: insights from the pig model,” Commun Biol, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 1–9, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Cassina, P. Silveira, L. Cantu, J. Maria Montes, R. Radi, and R. Sapiro, “Defective Human Sperm Cells Are Associated with Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidant Production,” BIOLOGY OF REPRODUCTION, vol. 93, no. 5, Nov. 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Agarwal et al., “Comparative proteomic network signatures in seminal plasma of infertile men as a function of reactive oxygen species,” Clinical Proteomics, vol. 12, no. 1, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Boguenet et al., “Metabolomic signature of the seminal plasma in men with severe oligoasthenospermia,” ANDROLOGY, vol. 8, no. 6, pp. 1859–1866, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Li et al., “Metabolomic characterization of semen from asthenozoospermic patients using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry,” BIOMEDICAL CHROMATOGRAPHY, vol. 34, no. 9, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Zhao et al., “Metabolomic Profiling of Human Spermatozoa in Idiopathic Asthenozoospermia Patients Using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry.,” Biomed Res Int, vol. 2018, p. 8327506, 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Paoli et al., “Mitochondrial membrane potential profile and its correlation with increasing sperm motility,” FERTILITY AND STERILITY, vol. 95, no. 7, pp. 2315–2319, Jun. 2011. [CrossRef]

- S. Larriba, J. F. Sanchez-Herrero, R. Pluvinet, O. Lopez-Rodrigo, L. Bassas, and L. Sumoy, “Seminal extracellular vesicle sncRNA sequencing reveals altered miRNA/isomiR profiles as sperm retrieval biomarkers for azoospermia,” ANDROLOGY, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 137–156, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. D. Costa, S. Amaral, K. Redmann, S. Kliesch, and S. Schlatt, “Spectral features of nuclear DNA in human sperm assessed by Raman Microspectroscopy: Effects of UV-irradiation and hydration,” PLoS ONE, vol. 13, no. 11, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Calvert, S. Reynolds, M. N. Paley, S. J. Walters, and A. A. Pacey, “Probing human sperm metabolism using 13C-magnetic resonance spectroscopy,” MOLECULAR HUMAN REPRODUCTION, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 30–41, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Reynolds, S. J. Calvert, M. N. Paley, and A. A. Pacey, “1H Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy of live human sperm.,” Mol Hum Reprod, vol. 23, no. 7, pp. 441–451, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- N. Aziz, J. Novotny, I. Oborna, H. Fingerova, J. Brezinova, and M. Svobodova, “Comparison of chemiluminescence and flow cytometry in the estimation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in human semen.,” Fertil Steril, vol. 94, no. 7, pp. 2604–2608, Dec. 2010. [CrossRef]

- P. Irigoyen, P. Pintos-Polasky, L. Rosa-Villagran, M. F. Skowronek, A. Cassina, and R. Sapiro, “Mitochondrial metabolism determines the functional status of human sperm and correlates with semen parameters,” Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, vol. 10, 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Almeida, M. Cunha, L. Ferraz, J. Silva, A. Barros, and M. Sousa, “Caspase-3 detection in human testicular spermatozoa from azoospermic and non-azoospermic patients,” INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ANDROLOGY, vol. 34, no. 5, pp. E407–E414, Oct. 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Barceló, A. Mata, L. Bassas, and S. Larriba, “Exosomal microRNAs in seminal plasma are markers of the origin of azoospermia and can predict the presence of sperm in testicular tissue.,” Hum Reprod, vol. 33, no. 6, pp. 1087–1098, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- V. Calle-Guisado et al., “AMP-activated kinase in human spermatozoa: identification, intracellular localization, and key function in the regulation of sperm motility,” ASIAN JOURNAL OF ANDROLOGY, vol. 19, no. 6, pp. 707–714, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. Deng et al., “Lipidomics random forest algorithm of seminal plasma is a promising method for enhancing the diagnosis of necrozoospermia,” METABOLOMICS, vol. 20, no. 3, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. Fietz et al., “Proteomic biomarkers in seminal plasma as predictors of reproductive potential in azoospermic men.,” Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), vol. 15, p. 1327800, 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Fukuda, H. Miyake, N. Enatsu, K. Matsushita, and M. Fujisawa, “Seminal level of clusterin in infertile men as a significant biomarker reflecting spermatogenesis,” ANDROLOGIA, vol. 48, no. 10, pp. 1188–1194, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Hashemitabar, S. Sabbagh, M. Orazizadeh, A. Ghadiri, and M. Bahmanzadeh, “A proteomic analysis on human sperm tail: comparison between normozoospermia and asthenozoospermia.,” J Assist Reprod Genet, vol. 32, no. 6, pp. 853–863, Jun. 2015. [CrossRef]

- V. Jayaraman, S. Ghosh, A. Sengupta, S. Srivastava, H. M. Sonawat, and P. K. Narayan, “Identification of biochemical differences between different forms of male infertility by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy,” JOURNAL OF ASSISTED REPRODUCTION AND GENETICS, vol. 31, no. 9, pp. 1195–1204, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M.-A. Kyrgiafini, T. Giannoulis, A. Chatziparasidou, N. Christoforidis, and Z. Mamuris, “Unveiling the Genetic Complexity of Teratozoospermia: Integrated Genomic Analysis Reveals Novel Insights into lncRNAs’ Role in Male Infertility,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 24, no. 19, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Li et al., “Genome-wide methylation analyses of human sperm unravel novel differentially methylated regions in asthenozoospermia,” EPIGENOMICS, vol. 14, no. 16, pp. 951–964, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Liang et al., “Proteomic Profile of Sperm in Infertile Males Reveals Changes in Metabolic Pathways,” Protein Journal, vol. 40, no. 6, pp. 929–939, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu et al., “Raman spectroscopy as an ex vivo noninvasive approach to distinguish complete and incomplete spermatogenesis within human seminiferous tubules,” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 102, no. 1, pp. 54-60.e2, 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. D. Martins, M. K. P. Selvam, A. Agarwal, M. G. Alves, and S. Baskaran, “Alterations in seminal plasma proteomic profile in men with primary and secondary infertility,” SCIENTIFIC REPORTS, vol. 10, no. 1, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. Olesti et al., “Low-polarity untargeted metabolomic profiling as a tool to gain insight into seminal fluid,” Metabolomics, vol. 19, no. 6, 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Olesti et al., “Steroid profile analysis by LC-HRMS in human seminal fluid,” Journal of Chromatography B: Analytical Technologies in the Biomedical and Life Sciences, vol. 1136, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Paiva et al., “Identification of endogenous metabolites in human sperm cells using proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) spectroscopy and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS),” Andrology, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 496–505, 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Qiao et al., “Seminal plasma metabolomics approach for the diagnosis of unexplained male infertility,” PLOS ONE, vol. 12, no. 8, Aug. 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. Soler, V. Labas, A. Thélie, I. Grasseau, A.-P. Teixeira-Gomes, and E. Blesbois, “Intact cell MALDI-TOF MS on sperm: A molecular test for male fertility diagnosis,” Molecular and Cellular Proteomics, vol. 15, no. 6, pp. 1998–2010, 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. Sulc et al., “MALDI Imaging Mass Spectrometry Reveals Lipid Alterations in Physiological and Sertoli Cell-Only Syndrome Human Testicular Tissue Sections.,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 25, no. 15, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Torra-Massana et al., “Altered mitochondrial function in spermatozoa from patients with repetitive fertilization failure after ICSI revealed by proteomics,” Andrology, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 1192–1204, 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Torrezan-Nitao, S. G. Brown, E. Mata-Martínez, C. L. Treviño, C. Barratt, and S. Publicover, “[Ca2+]ioscillations in human sperm are triggered in the flagellum by membrane potential-sensitive activity of CatSper,” Human Reproduction, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 293–304, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Vashisht, P. K. Ahluwalia, and G. K. Gahlay, “A Comparative Analysis of the Altered Levels of Human Seminal Plasma Constituents as Contributing Factors in Different Types of Male Infertility.,” Curr Issues Mol Biol, vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 1307–1324, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Wainstein et al., “MicroRNAs expression in semen and testis of azoospermic men,” ANDROLOGY, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 687–697, 23. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- C. Wang et al., “Altered Profile of Seminal Plasma MicroRNAs in the Molecular Diagnosis of Male Infertility,” CLINICAL CHEMISTRY, vol. 57, no. 12, pp. 1722–1731, Dec. 2011. [CrossRef]

- X. Wu et al., “Unraveling epigenomic abnormality in azoospermic human males by WGBS, RNA-Seq, and transcriptome profiling analyses.,” J Assist Reprod Genet, vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 789–802, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xu et al., “RNASET2 impairs the sperm motility via PKA/PI3K/calcium signal pathways,” REPRODUCTION, vol. 155, no. 4, pp. 383–392, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. Zhao, Q. Zhang, R. Cong, Z. Xu, Y. Xu, and J. Han, “Metabolomic profiling of human semen in patients with oligospermia using high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry.,” Sci Rep, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 23739, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

| Authors | Study Aim | Methods/Tools | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agarwal et al., 2015 [41] | Identify seminal plasma proteins involved in ROS-mediated male infertility |

|

|

| Almeida et al., 2011 [52] | Quantify testicular sperm apoptosis via active caspase-3 in normal and impaired spermatogenesis |

|

|

| Amaral et al., 2013 [8] | Characterize human sperm tail proteome, focusing on metabolism-related proteins |

|

|

| Aziz et al., 2010 [50] | Determine cell type contributions to intracellular H2O2 and peroxynitrite production in sperm |

|

|

| Barceló et al., 2018 [53] | Evaluate seminal plasma exosomal mirnas as markers for Azoospermia origin and sperm presence |

|

|

| Boguenet et al., 2020 [42] | Assess metabolomic signatures of seminal plasma in severe Oligoasthenospermia |

|

|

| Calle-Guisado et al., 2017 [54] | Identify and localize AMP- activated protein kinase (AMPK) in human sperm and evaluate its role in sperm motility |

|

|

| Calvert et al., 2019 [48] | Investigate sperm metabolism |

|

|

| Cassina et al., 2015 [40] | Analyze mitochondrial function and oxidative stress in human sperm affecting fertility |

|

|

| Costa et al., 2018 [47] | Assessement of sperm DNA damage and biochemical features |

|

|

| Deng et al., 2024 [55] | Profile seminal plasma lipid composition in necrozoospermia and evaluate lipid biomarkers |

|

|

| Fietz et al., 2024 [56] | Discover seminal plasma biomarkers for non-invasive differential diagnosis of Obstructive Azoospermia (OA) vs. Non-Obstructive Azoospermia (NOA) |

|

|

| Fukuda et al., 2016 [57] | Assess impact of seminal clusterin level on spermatogenesis and sperm retrieval in infertile men |

|

|

| Hashemitabar et al., 2015 [58] | Identify novel biomarkers for asthenozoospermia via sperm tail proteomic analysis |

|

|

| He et al., 2024 [9] | Investigate seminal microbiome and metabolome role in high sperm DNA fragmentation index (HDFI) |

|

|

| Irigoyen et al., 2022 [51] | Assess sperm mitochondrial metabolism and ROS production as tools to complement semen analysis |

|

|

| Jayaraman et al., 2014 [59] | Analyze seminal plasma metabolic profiles in idiopathic/male factor infertility |

|

|

| Kyrgiafini et al., 2023 [60] | Identify lncRNA mutations and expression in teratozoospermia |

|

|

| Larriba et al., 2024 [46] | Small RNA profiling in seminal extracellular vesicles for azoospermia classification |

|

|

| Li et al., 2022 [61] | Investigate DNA methylation patterns in asthenozoospermia |

|

|

| Liang et al., 2021 [62] | Proteomic profiling of sperm in severe oligoasthenoteratozoospermia |

|

|

| Liu et al., 2014 [63] | Identify spermatogenesis in testicular tissue |

|

|

| Martins et al., 2020 [64] | Characterize seminal plasma proteome in primary and secondary infertility |

|

|

| Milardi et al., 2014 [10] | Identify seminal biomarkers for secondary male hypogonadism (HH) |

|

|

| Olesti et al., 2023 [65] | Correlate metabolomic profiles with semen quality in young men |

|

|

| Olesti et al., 2020 [66] | Develop steroidomics strategy for human seminal fluid |

|

|

| Paiva et al., 2015 [67] | Comprehensive metabolomic characterization of human sperm cell |

|

|

| Paoli et al., 2011 [45] | Correlate sperm mitochondrial integrity with motility |

|

|

| Qiao et al., 2017 [68] | Metabolic profiling of unexplained male infertility (UMI) |

|

|

| Reynolds et al., 2017 [49] | Examine sperm molecules |

|

|

| Sharma et al., 2013 [11] | Identify seminal plasma proteins as biomarkers of sperm quality |

|

|

| Sharma et al., 2013 [12] | Proteomic profile changes in spermatozoa with elevated ROS |

|

|

| Soler et al., 2016 [69] | Fertility-predictive model profiles of spermatozoa |

|

|

| Sulc et al., 2024 [70] | Phospholipid expression in Sertoli cell-only syndrome (SCOS) testis |

|

|

| Massana et al., 2021 [71] | Proteomic analysis of sperm in fertilization failure after ICSI |

|

|

| Nitao et al., 2021 [72] | Progesterone-induced Ca2+ oscillations in human sperm |

|

|

| Vashisht et al., 2021 [73] | Evaluate seminal plasma biochemical and immunological markers in male infertility |

|

|

| Wainstein et al., 2023 [74] | Study microRNA profiles in semen and testicular tissue of azoospermic men |

|

|

| Wang et al., 2011 [75] | Seminal plasma miRNAs in infertile men and diagnostic value |

|

|

| Wu et al., 2020 [76] | DNA methylation in testicular cells of azoospermia patients |

|

|

| Xu et al., 2018 [77] | Ribonuclease (RNASET2) levels in sperm and relation to motility |

|

|

| Zhao et al., 2018 [44] | Metabolic profiling of idiopathic asthenozoospermia sperm cells |

|

|

| Zhao et al., 2024 [78] | Semen metabolic profiling in oligospermia patients |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).