Submitted:

26 August 2025

Posted:

27 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Enrollment

2.2. Collection of the Follicular Fluid Samples

2.3. Sample Processing and Measurement of Amino Acids

2.3.1. Reagents

2.3.2. Sample Preparation for UHPLC Measurement

2.3.3. Derivatization

2.3.4. UHPLC Method Parameters

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patients’ Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

3.2. Amino Acid Analysis of the FF Samples

3.3. Comparison of Amino Acid Profiles Between EM and Control Groups

3.4. Comparison of Amino Acid Concentration Based on Body Mass Index (BMI)

3.5. Comparison of Amino Acid Concentration Based on the Age of the Patients

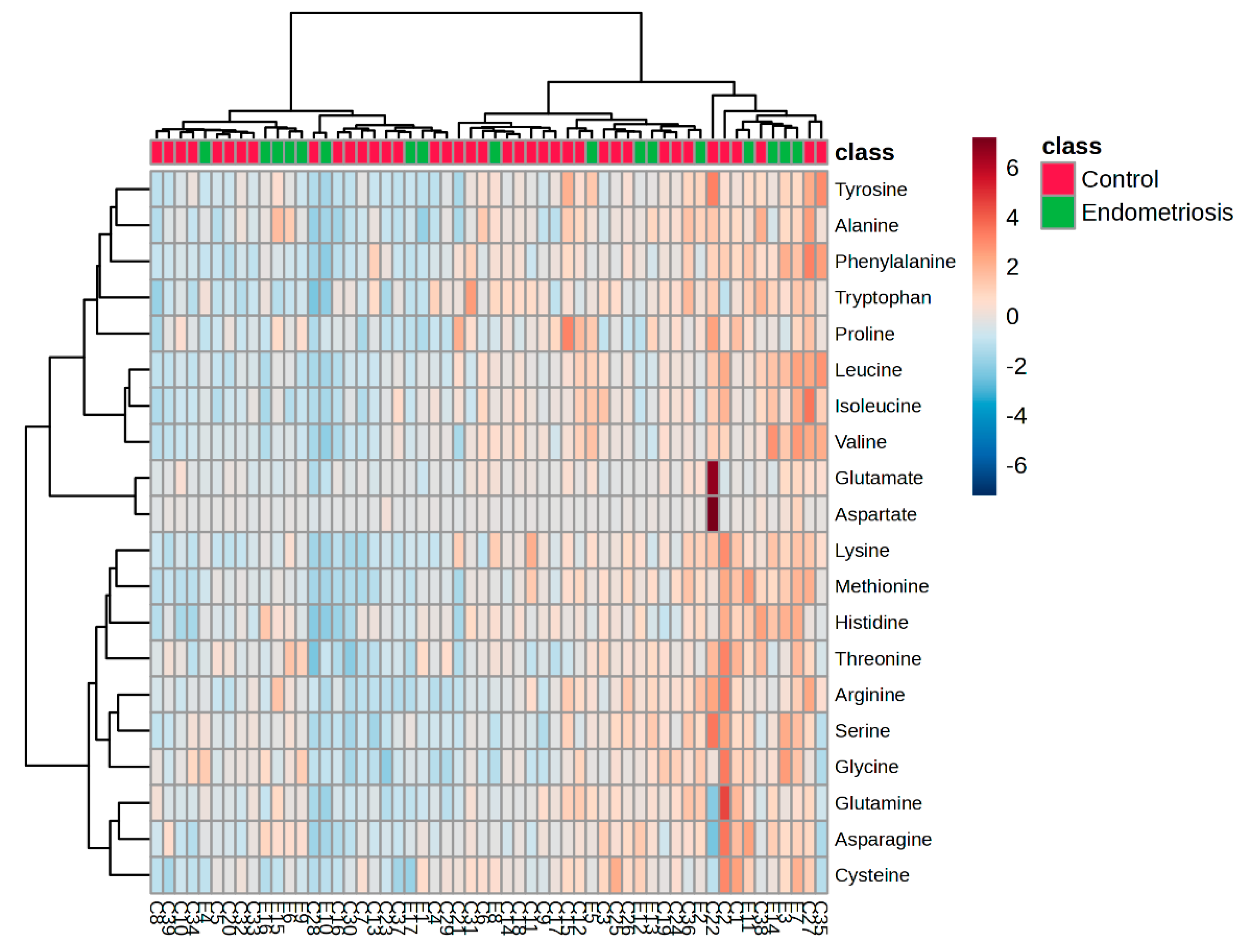

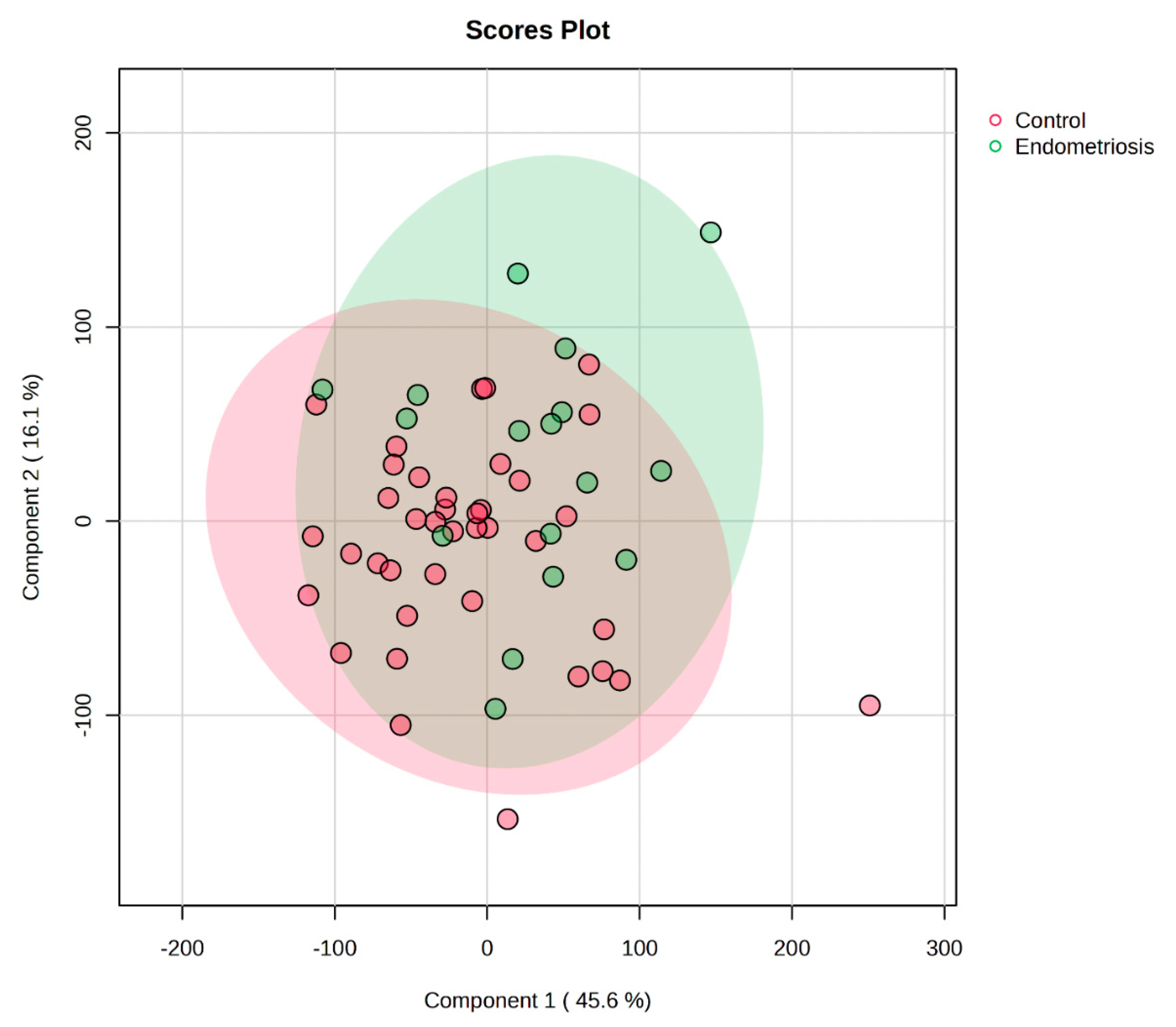

3.6. Heatmap and PLS-DA Analysis

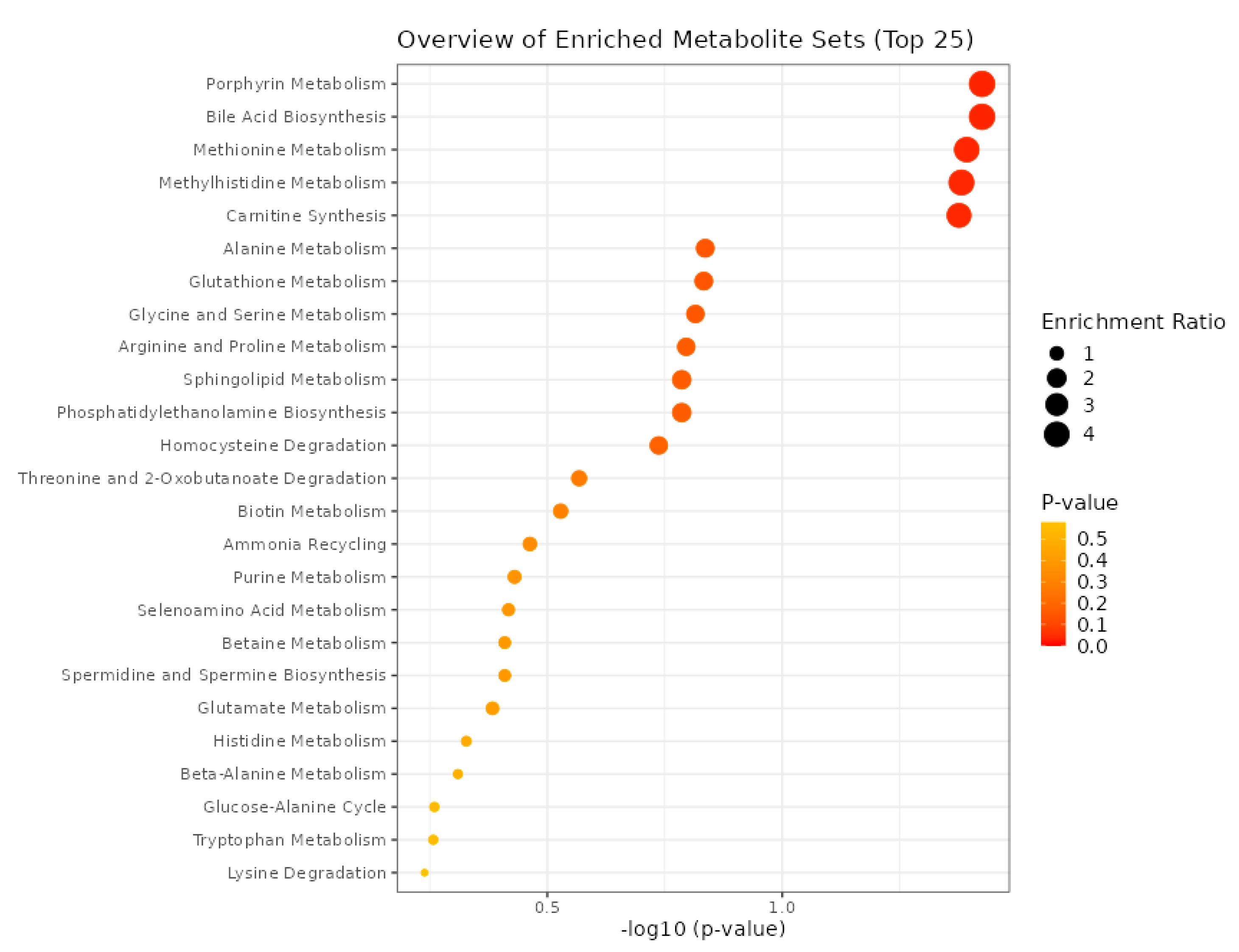

3.7. Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis (MSEA)

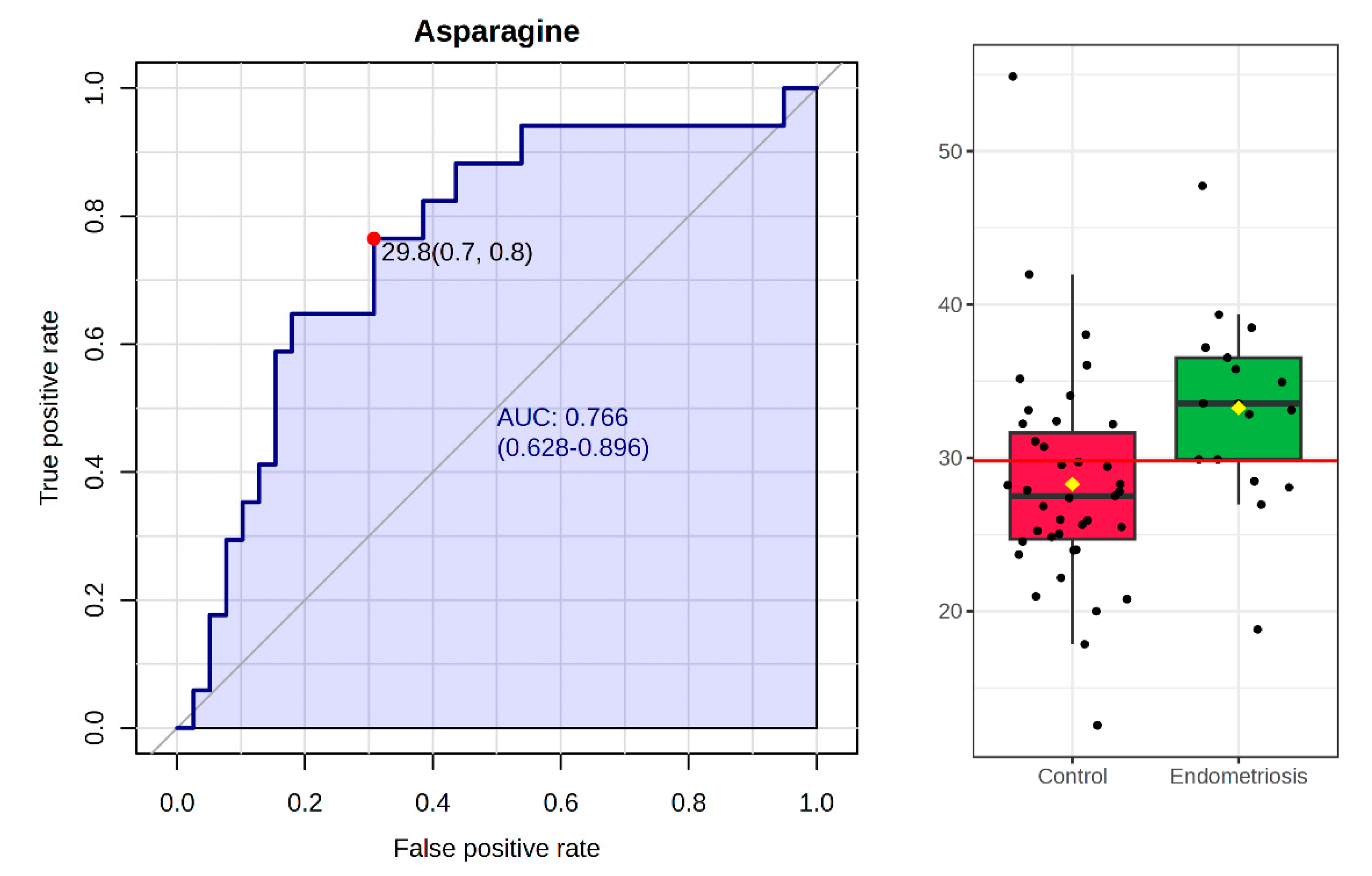

3.8. Biomarker Analysis

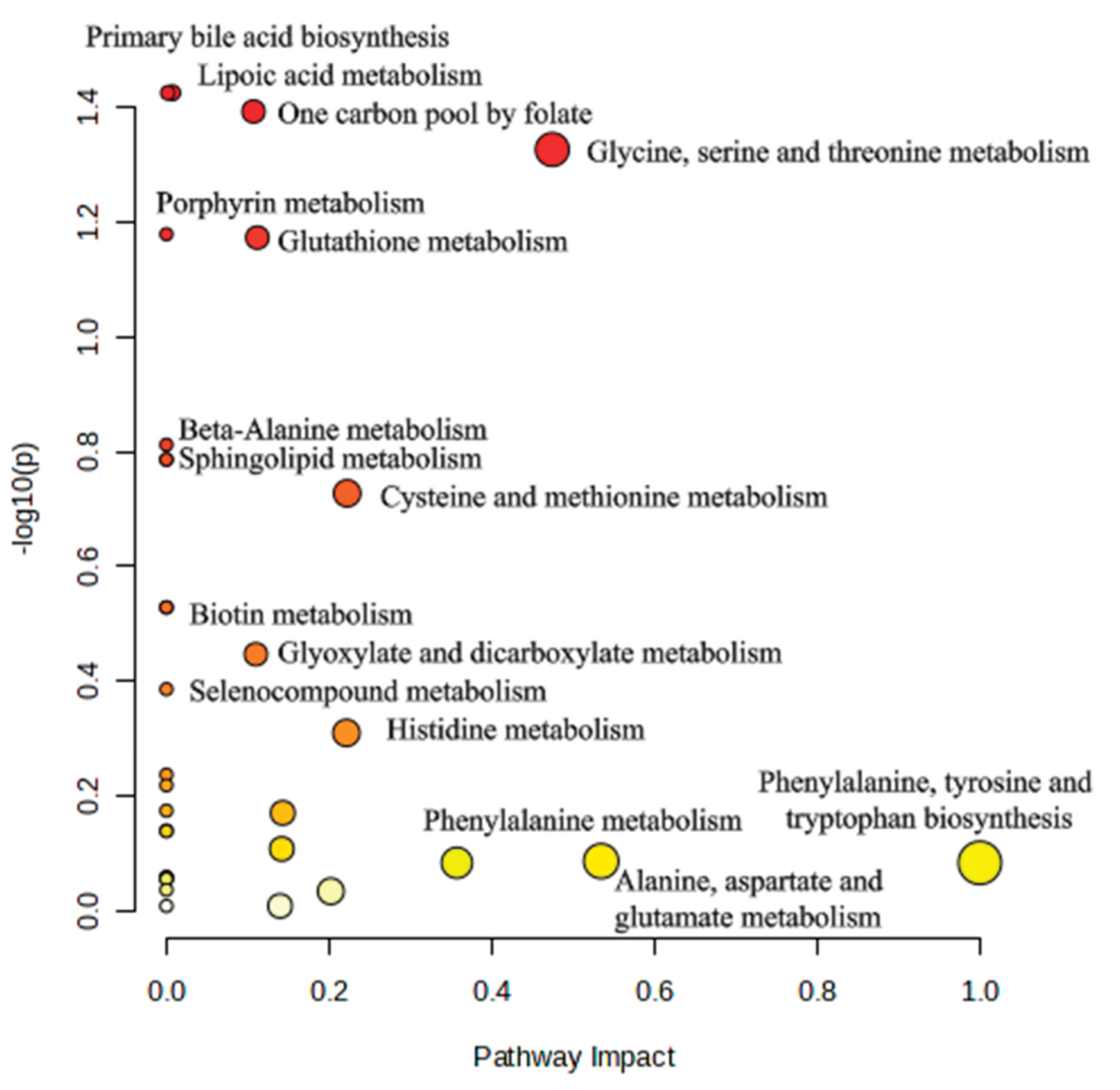

3.9. Pathway Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EM | Endometriosis |

| FF | Follicular fluid |

| ART | Artificial reproductive treatment |

| rFSH | Recombinant follicle stimulating hormone |

| rLH | Recombinant luteinizing hormone |

| hMG | Human menopausal gonadotropin |

| hCG | Human chorionic gonadotropin |

| MPA | 3-mercaptopropionic acid |

| FMOC | 9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl chloride |

| OPA | Ortho-phthalaldehyde |

| RT | Retention time |

| AUC | Area under curve |

| PLS-DA | Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| MSEA | Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis |

| PCOS | Polycystic ovary syndrome |

| BCAAs | Branched-chain amino acids |

References

- Fan, Y.; Yang, Q.; Lin, Y.; Fu, X.; Shu, J. The effect of endometriosis on oocyte quality: mechanisms, diagnosis and treatment. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, P.T.K.; Whitaker, L.H.R.; Horne, A.W. Endometriosis: Improvements and challenges in diagnosis and symptom management. Cell Press. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, S.; Murk, W.; Arici, A. Endometriosis and infertility: Epidemiology and evidence-based treatments. in Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, Blackwell Publishing Inc., 2008, pp. 92–100. [CrossRef]

- Bulletti, C.; Coccia, M.E.; Battistoni, S.; Borini, A. Endometriosis and infertility. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q.; et al. Update on the pathogenesis of endometriosis-related infertility based on contemporary evidence. Frontiers Media SA. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Marca, A.; et al. Fertility preservation in women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod Open 2025, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonavina, G.; Taylor, H.S. Endometriosis-associated infertility: From pathophysiology to tailored treatment. Frontiers Media S.A. 2022, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulletti, C.; Coccia, M.E.; Battistoni, S.; Borini, A. Endometriosis and infertility. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, G. Causal Relationship Between Endometriosis, Female Infertility, and Primary Ovarian Failure Through Bidirectional Mendelian Randomization. Int J Womens Health 2024, 16, 2143–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ban, Y.; Ran, H.; Chen, Y.; Ma, L. Lipidomics analysis of human follicular fluid form normal-weight patients with polycystic ovary syndrome: a pilot study. J Ovarian Res 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrabiah, N.A.; Simintiras, C.A.; Evans, A.C.O.; Lonergan, P.; Fair, T. Biochemical alterations in the follicular fluid of bovine peri-ovulatory follicles and their association with final oocyte maturation. Reproduction and Fertility 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; et al. Human Follicular Fluid Metabolomics Study of Follicular Development and Oocyte Quality. Chromatographia 2017, 80, 901–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; et al. Metabolomics analysis of follicular fluid in ovarian endometriosis women receiving progestin-primed ovary stimulation protocol for in vitro fertilization. Sci Rep 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Broi, M.G.; Giorgi, V.S.I.; Wang, F.; Keefe, D.L.; Albertini, D.; Navarro, P.A. Influence of follicular fluid and cumulus cells on oocyte quality: Clinical implications. J Assist Reprod Genet 2018, 35, 735–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinca, A.T.; et al. Follicular Fluid and Blood Monitorization of Infertility Biomarkers in Women with Endometriosis. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, J.K.; Lindon, J.C.; Holmes, E. understanding the metabolic responses of living systems to pathophysiological stimuli via multivariate statistical analysis of biological NMR spectroscopic data.” [Online]. Available: www.taylorandfrancis.com}.

- Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, Y.; Zhu, P.; Yin, T.; Wan, Q. Metabonomic analysis of follicular fluid in patients with diminished ovarian reserve. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hood, R.B.; et al. Characterizing the follicular fluid metabolome: quantifying the correlation across follicles and differences with the serum metabolome. Fertil Steril 2022, 118, 970–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Józwik, M.; Józwik, M.; Teng, C.; Battaglia, F.C. Amino acid, ammonia and urea concentrations in human pre-ovulatory ovarian follicular fluid. Human Reproduction 2006, 21, 2776–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsipuu, T.; Laks, K.; Velthut-Meikas, A.; Levkov, L.; Salumets, A.; Palumaa, P. Comprehensive elucidation of amino acid profile in human follicular fluid and plasma of in vitro fertilization patients. Gynecological Endocrinology 2015, 31, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdi, C.; et al. Amino Acid Profiling of Follicular Fluid in Assisted Reproduction Reveals Important Roles of Several Amino Acids in Patients with Insulin Resistance. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.; Yi, K.W. What is the link between endometriosis and adiposity? Obstet Gynecol Sci 2022, 65, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; et al. Endometrium metabolomic profiling reveals potential biomarkers for diagnosis of endometriosis at minimal-mild stages. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 2018, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruebel, M.L.; et al. Obesity leads to distinct metabolomic signatures in follicular fluid of women undergoing in vitro fertilization. J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2019, 316, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newgard, C.B.; et al. A Branched-Chain Amino Acid-Related Metabolic Signature that Differentiates Obese and Lean Humans and Contributes to Insulin Resistance. Cell Metab 2009, 9, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; et al. Nontargeted metabolomics analysis of follicular fluid in patients with endometriosis provides a new direction for the study of oocyte quality. MedComm (Beijing) 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamyan, L.; et al. Metabolomic biomarkers of endometriosis: A systematic review. Journal of Endometriosis and Uterine Disorders 2024, 7, 100077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, L. The Impact of Follicular Fluid Oxidative Stress Levels on the Outcomes of Assisted Reproductive Therapy. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.-M.; et al. Metabolic heterogeneity of follicular amino acids in polycystic ovary syndrome is affected by obesity and related to pregnancy outcome. 2014. [Online]. Available: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2393/14/11.

- Chiang, S.K.; Chen, S.E.; Chang, L.C. The role of HO-1 and its crosstalk with oxidative stress in cancer cell survival. MDPI. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izumi, Y.; et al. Hepcidin as a key regulator of iron homeostasis triggers inflammatory features in the normal endometrium. Free Radic Biol Med 2023, 209, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scutiero, G.; et al. Oxidative Stress and Endometriosis: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Hindawi Limited. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; et al. Integrative analysis of transcriptomic and metabolomic profiles reveals abnormal phosphatidylinositol metabolism in follicles from endometriosis-associated infertility patients. Journal of Pathology 2023, 260, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, R.; Tian, G.; Liu, J.; Cao, L. The gut microbiota and endometriosis: From pathogenesis to diagnosis and treatment. Frontiers Media S.A. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, K.; Ding, J.; Sun, S.; Ni, Z.; Yu, C. Influence of the gut microbiota on endometriosis: Potential role of chenodeoxycholic acid and its derivatives. Frontiers Media S.A. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, K.; Ding, J.; Sun, S.; Ni, Z.; Yu, C. Influence of the gut microbiota on endometriosis: Potential role of chenodeoxycholic acid and its derivatives. Frontiers Media S.A. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, S.; Xu, H.; Lei, S.; Zhao, D. Overexpressed nicotinamide N-methyltransferase in endometrial stromal cells induced by macrophages and estradiol contributes to cell proliferation in endometriosis. Cell Death Discov 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newgard, C.B.; et al. A Branched-Chain Amino Acid-Related Metabolic Signature that Differentiates Obese and Lean Humans and Contributes to Insulin Resistance. Cell Metab 2009, 9, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murgia, F.; et al. Metabolic Profile of Patients with Severe Endometriosis: a Prospective Experimental Study”. [CrossRef]

- Atkins, H.M.; Bharadwaj, M.S.; Cox, A.O.; Furdui, C.M.; Appt, S.E.; Caudell, D.L. Endometrium and endometriosis tissue mitochondrial energy metabolism in a nonhuman primate model. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 2019, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clower, L.; Fleshman, T.; Geldenhuys, W.J.; Santanam, N. Targeting Oxidative Stress Involved in Endometriosis and Its Pain. MDPI. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Máté, G.; Bernstein, L.R.; Török, A.L. Endometriosis Is a Cause of Infertility. Does Reactive Oxygen Damage to Gametes and Embryos Play a Key Role in the Pathogenesis of Infertility Caused by Endometriosis? Frontiers Media S.A. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; et al. Chronic Stress Blocks the Endometriosis Immune Response by Metabolic Reprogramming. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; et al. Identification of Potential Molecular Mechanism Related to Infertile Endometriosis. Front Vet Sci 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Endometriosis [Mean ± SD] (n=17) |

Control [Mean ± SD] (n=39) |

|

| Age | 35.14 ± 4.34 | 33.26 ± 4.18 |

| BMI | 22.87 ± 5.71 | 25.29 ± 5.66 |

| Number of oocytes retrieved | 8.13 ± 4.49 | 10.49 ± 6.66 |

| Number of fertilized oocytes | 3.18 ± 2.00 | 3.89 ± 3.91 |

| Number of IVF cycles | 1.94 ± 0.93 | 1.86 ± 1.38 |

| Baseline estradiol | 2954.44 ± 749.75 | 2426.51 ± 912.06 |

| FSH dose during stimulation | 1083.94 ± 1430.84 | 1417.31 ± 1382.14 |

| Cause of infertility | ||

| Male factor | - | 26 (66.66 %) |

| Female factor | 15 (88.23%) | 8 (20.51 %) |

| Combined male-female | 2 (11.76%) | 5 (12.82 %) |

| Endometriosis [Mean ± SD] µmol/L |

Control [Mean ± SD] µmol/L |

|

| Aspartate | 7.01± 4.28 | 8.45 ± 16.49 |

| Glutamate | 63.35 ± 20.85 | 69.67 ± 47.92 |

| Asparagine | 33.25 ± 6.28 | 28.29 ± 7.12 |

| Serine | 57.31 ± 15.84 | 50.09 ± 18.28 |

| Glutamine | 350.41 ± 72.65 | 346.30 ± 101.53 |

| Histidine | 58.95 ± 13.26 | 51.71 ± 11.33 |

| Glycine | 178.58 ± 51.28 | 147.43 ± 49.84 |

| Threonine | 109.51 ± 23.00 | 100.46 ± 29.82 |

| Arginine | 34.85 ± 11.00 | 33.16 ± 13.65 |

| Alanine | 240.32 ± 56.45 | 226.05 ± 60.46 |

| Tyrosine | 30.82 ± 8.45 | 30.75 ± 11.26 |

| Cysteine | 20.09 ± 6.56 | 20.40 ± 6.66 |

| Valine | 134.37 ± 53.51 | 128.41 ± 34.81 |

| Methionine | 16.81 ± 4.39 | 15.75 ± 4.10 |

| Tryptophan | 47.65 ± 5.92 | 48.44 ± 6.70 |

| Phenylalanine | 38.52 ± 9.65 | 40.04 ± 9.21 |

| Isoleucine | 27.22 ± 9.19 | 29.42 ± 8.82 |

| Leucine | 54.74 ± 20.94 | 54.74 ± 18.48 |

| Lysine | 89.35 ± 21.57 | 81.89 ± 25.42 |

| Proline | 143.05 ± 42.37 | 150.10 ± 54.00 |

| Significance (p) values | ||||

| EM/CG | BMI | Age | Outcome | |

| Aspartate | 0.515 | 0.177 | 0.967 | 0.314 |

| Glutamate | 0.599 | 0.069 | 0.755 | 0.142 |

| Asparagine | 0.002* | 0.018* | 0.651 | 0.212 |

| Serine | 0.06 | 0.921 | 1 | 0.755 |

| Glutamine | 0.493 | 0.208 | 0.384 | 0.755 |

| Histidine | 0.049* | 0.431 | 0.332 | 0.076 |

| Glycine | 0.025* | 0.42 | 0.033* | 0.350 |

| Threonine | 0.173 | 0.48 | 0.56 | 0.612 |

| Arginine | 0.368 | 0.651 | 0.48 | 0.810 |

| Alanine | 0.25 | 0.273 | 0.393 | 0.838 |

| Tyrosine | 0.493 | 0.135 | 0.663 | 0.482 |

| Cysteine | 0.908 | 0.474 | 0.954 | 0.702 |

| Valine | 0.922 | 0.042* | 0.576 | 0.386 |

| Methionine | 0.465 | 0.758 | 0.712 | 0.402 |

| Tryptophane | 0.782 | 0.556 | 0.576 | 0.281 |

| Phenylalanine | 0.605 | 0.436 | 0.495 | 0.412 |

| Isoleucine | 0.222 | 0.13 | 0.332 | 0.515 |

| Leucine | 0.88 | 0.265 | 0.657 | 0.769 |

| Lysine | 0.151 | 0.863 | 0.818 | 0.587 |

| Proline | 0.838 | 0.25 | 0.44 | 0.551 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).