Submitted:

09 May 2025

Posted:

12 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Magnesium and Carcinogenesis

3. Magnesium and Cancer Treatment

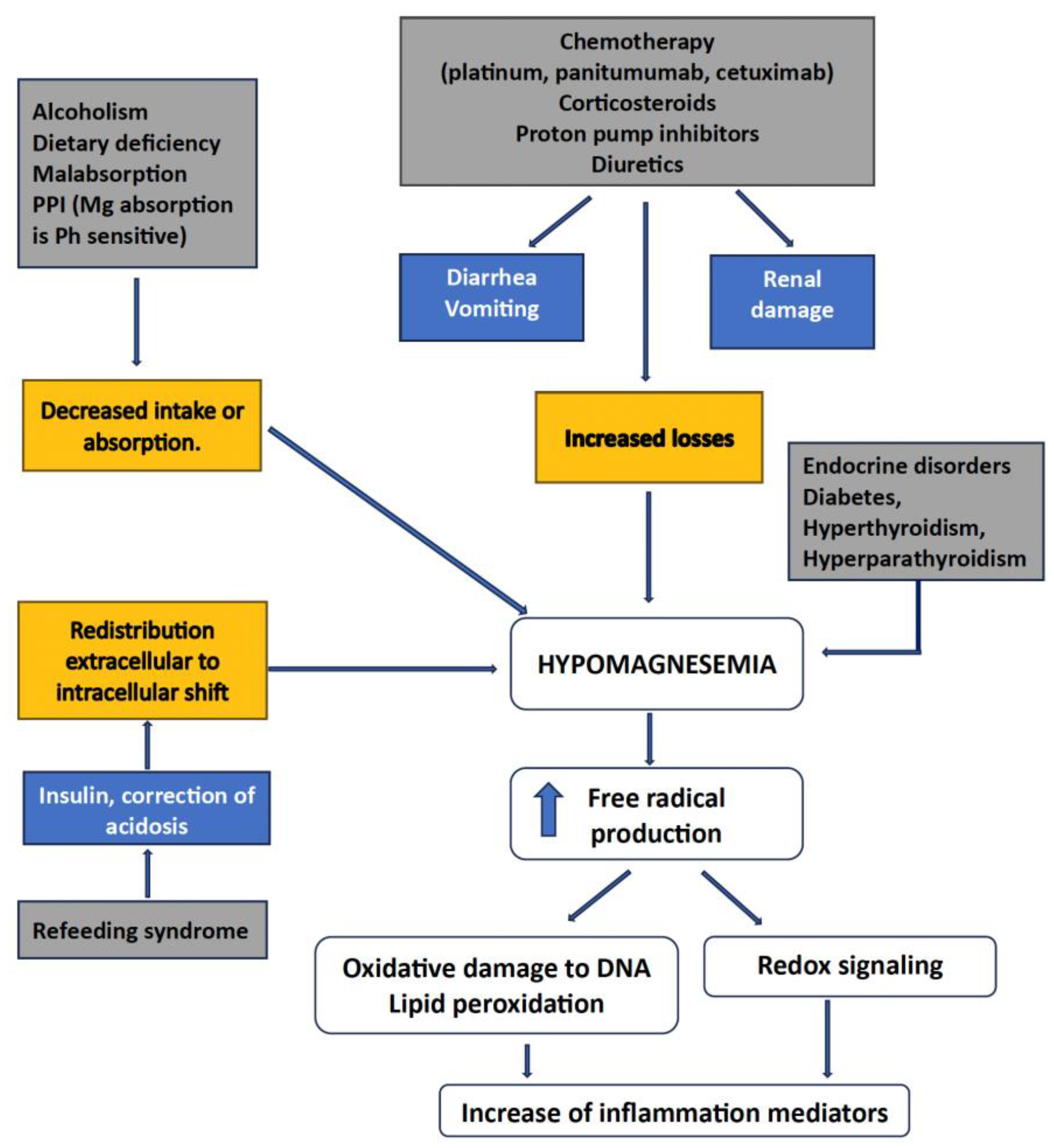

3.1. Hypomagnesemia

3.2. Platinum Salts

3.3. Anti-EGFR Antibodies

3.4. Proton Pump Inhibitors

3.5. Dietary Mg2+ Supplementation

3.6. Cardiotoxicity

3.7. Nephrotoxicity and Nephroprotection from Chemotherapy

3.8. Radiotherapy Protection

3.9. Cachexia

3.10. Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy

3.11. Cancer Pain

3.12. Opioid-Induced Constipation

3.12. Other Drug Interactions

4. Magnesium and Cancer Risk

4.1. Colorectal Cancer

4.2. Esophageal Cancer

4.3. Lung Cancer

4.4. Thyroid Cancer

4.5. Breast Cancer (BC)

4.6. Cervical Cancer

4.7. Endometrial Cancer

4.8. Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)

5. Therapeutic Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Mg2+ | Magnesium2+ |

| CRC | Colorectal carcinoma |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

References

- Behers, B.J.; Melchor, J.; Behers, B.M.; Meng, Z.; Swanson, P.J.; Paterson, H.I.; Araque, S.J.M.; Davis, J.L.; Gerhold, C.J.; Shah, R.S.; et al. Vitamins and Minerals for Blood Pressure Reduction in the General, Normotensive Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Six Supplements. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez, L.J.; Veronese, N.; Barbagallo, M. Magnesium and the Hallmarks of Aging. Nutrients 2024, 16, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashique, S.; Kumar, S.; Hussain, A.; Mishra, N.; Garg, A.; Gowda, B.H.J.; Farid, A.; Gupta, G.; Dua, K.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. A narrative review on the role of magnesium in immune regulation, inflammation, infectious diseases, and cancer. J. Heal. Popul. Nutr. 2023, 42, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbagallo, M.; Veronese, N.; Dominguez, L.J. Magnesium in Aging, Health and Diseases. Nutrients 2021, 13, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwalfenberg, G.K.; Genuis, S.J. The Importance of Magnesium in Clinical Healthcare. Scientifica 2017, 2017, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapani, V.; Wolf, F.I. Dysregulation of Mg2+ homeostasis contributes to acquisition of cancer hallmarks. Cell Calcium 2019, 83, 102078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trapani, V.; Arduini, D.; Cittadini, A.; Wolf, F.I. From magnesium to magnesium transporters in cancer: TRPM7, a novel signature in tumour development. Magnes. Res. 2013, 26, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weglicki, W.B. Hypomagnesemia and Inflammation: Clinical and Basic Aspects. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2012, 32, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaque, M.S. Magnesium: Are We Consuming Enough? Nutrients 2018, 10, 1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlach, J.; Bara, M.; Guiet-Bara, A.; Collery, P. Relationship between magnesium, cancer, and carcinogenic or anti-cancer metals. Anti-cancer Res. 1986, 6, 1353–1361. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Castiglioni, S.; Maier, J.A. Magnesium and cancer: a dangerous liason. Magnes. Res. 2011, 24, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błaszczyk, U.; Duda-Chodak, A. Magnesium: its role in nutrition and carcinogenesis. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 2013, 64, 165–71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nasulewicz, A.; Wietrzyk, J.; Wolf, F.I.; Dzimira, S.; Madej, J.; Maier, J.A.M.; Rayssiguier, Y.; Mazur, A.; Opolski, A. Magnesium deficiency inhibits primary tumor growth but favors metastasis in mice. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Basis Dis. 2004, 1739, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karska, J.; Kowalski, S.; Saczko, J.; Moisescu, M.G.; Kulbacka, J. Mechanosensitive Ion Channels and Their Role in Cancer Cells. Membranes 2023, 13, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappadone, C.; Merolle, L.; Marraccini, C.; Farruggia, G.; Sargenti, A.; Locatelli, A.; Morigi, R.; Iotti, S. Intracellular magnesium content decreases during mitochondria-mediated apoptosis induced by a new indole-derivative in human colon cancer cells. Magnes. Res. 2012, 25, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, F.I.; Maier, J.A.M.; Nasulewicz, A.; Feillet-Coudray, C.; Simonacci, M.; Mazur, A.; Cittadini, A. Magnesium and neoplasia: From carcinogenesis to tumor growth and progression or treatment. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2006, 458, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anghileri, L.J. Magnesium, calcium and cancer. Magnes. Res. 2009, 22, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, F.I.; Trapani, V. Magnesium and its transporters in cancer: a novel paradigm in tumour development. Clin. Sci. 2012, 123, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, P.; Vandsemb, E.N.; Børset, M. Phosphatases of regenerating liver are key regulators of metabolism in cancer cells – role of Serine/Glycine metabolism. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2021, 25, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, F.I.; Maier, J.A.M.; Nasulewicz, A.; Feillet-Coudray, C.; Simonacci, M.; Mazur, A.; Cittadini, A. Magnesium and neoplasia: From carcinogenesis to tumor growth and progression or treatment. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2006, 458, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, M.; Workeneh, B.T.; Uppal, N.N. Hypomagnesemia in Patients With Cancer: The Forgotten Ion. Semin. Nephrol. 2022, 42, 151347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosner, M.H.; Renaghan, A.D. Disorders of Divalent Ions (Magnesium, Calcium, and Phosphorous) in Patients With Cancer. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2022, 28, 447–459.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liamis, G.; Hoorn, E.J.; Florentin, M.; Milionis, H. An overview of diagnosis and management of drug-induced hypomagnesemia. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2021, 9, e00829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whang, R. Magnesium deficiency: Pathogenesis, prevalence, and clinical implications. Am. J. Med. 1987, 82, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workeneh, B.T.; Uppal, N.N.; Jhaveri, K.D.; Rondon-Berrios, H. Hypomagnesemia in the Cancer Patient. Kidney360 2021, 2, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, M.-C.; Wu, C.-F.; Chen, C.-W.; Shi, C.-S.; Huang, W.-S.; Kuan, F.-C. Hypomagnesemia and clinical benefits of anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies in wild-type KRAS metastatic colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oronsky, B.; Caroen, S.; Oronsky, A.; Dobalian, V.E.; Oronsky, N.; Lybeck, M.; Reid, T.R.; Carter, C.A. Electrolyte disorders with platinum-based chemotherapy: mechanisms, manifestations and management. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2017, 80, 895–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikking, C.; Niggebrugge-Mentink, K.L.; van der Sman, A.S.E.; Smit, R.H.P.; Bouman-Wammes, E.W.; Beex-Oosterhuis, M.M.; van Kesteren, C. Hydration Methods for Cisplatin Containing Chemotherapy: A Systematic Review. Oncol. 2023, 29, e173–e186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhang, W.; Yue, L.; Liu, T. A systematic review for prevention of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity using different hydration protocols and meta-analysis for magnesium hydrate supplementation. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2023, 28, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, H.; Iihara, H.; Suzuki, A.; Kobayashi, R.; Matsuhashi, N.; Takahashi, T.; Yoshida, K.; Itoh, Y. Hypomagnesemia is a reliable predictor for efficacy of anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody used in combination with first-line chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2016, 77, 1209–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alem, A.; Edae, C.K.; Wabalo, E.K.; Tareke, A.A.; Bedanie, A.A.; Reta, W.; Bariso, M.; Bekele, G.; Zawdie, B. Factors influencing the occurrence of electrolyte disorders in cancer patients. SAGE Open Med. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrag, D.; Chung, K.Y.; Flombaum, C.; Saltz, L. Cetuximab Therapy and Symptomatic Hypomagnesemia. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2005, 97, 1221–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miltiadous, G.; Christidis, D.; Kalogirou, M.; Elisaf, M. Causes and mechanisms of acid–base and electrolyte abnormalities in cancer patients. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2008, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrelli, F.; Borgonovo, K.; Cabiddu, M.; Ghilardi, M.; Barni, S. ; Md Risk of anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody-related hypomagnesemia: systematic review and pooled analysis of randomized studies. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2011, 11, S9–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsura, H.; Suga, Y.; Kubo, A.; Sugimura, H.; Kumatani, K.; Haruki, K.; Yonezawa, M.; Narita, A.; Ishijima, R.; Ikesue, H.; et al. Risk Evaluation of Proton Pump Inhibitors for Panitumumab-Related Hypomagnesemia in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2024, 47, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Meyer, L.; Morse, M.; Li, Y.; Song, J.; Engle, R.; Lopez, G.; Narayanan, S.; Soliman, P.T.; Ramondetta, L.; et al. Dietary Magnesium Replacement for Prevention of Hypomagnesemia in Patients With Ovarian Cancer Receiving Carboplatin-Based Chemotherapy. JCO Oncol. Pr. 2024, 20, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vejpongsa, P.; Yeh, E.T. Prevention of Anthracycline-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Circ. 2014, 64, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, C.; Rienzo, A.; Piscopo, G.; Barbieri, A.; Arra, C.; Maurea, N. Management of QT prolongation induced by anti-cancer drugs: Target therapy and old agents. Different algorithms for different drugs. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2018, 63, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Li, S.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Rios, F.J.; Zou, Z.; Touyz, R.M. Cardiovascular toxicity of tyrosine kinase inhibitors during cancer treatment: Potential involvement of TRPM7. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1002438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crona, D.J.; Faso, A.; Nishijima, T.F.; McGraw, K.A.; Galsky, M.D.; Milowsky, M.I. A Systematic Review of Strategies to Prevent Cisplatin-Induced Nephrotoxicity. Oncol. 2017, 22, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, A.G.; Hernández-Sánchez, M.T.; López-Hernández, F.J.; Martínez-Salgado, C.; Prieto, M.; Vicente-Vicente, L.; Morales, A.I. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy of clinically tested protectants of cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 76, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhang, W.; Yue, L.; Liu, T. A systematic review for prevention of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity using different hydration protocols and meta-analysis for magnesium hydrate supplementation. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2023, 28, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Glezerman, I.G.; Hirsch, J.S.; Chewcharat, A.; Wells, S.L.; Ortega, J.L.; Pirovano, M.; Kim, R.; Chen, K.L.; Jhaveri, K.D.; et al. Intravenous Magnesium and Cisplatin-Associated Acute Kidney Injury. JAMA Oncol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanzawa, S.; Yoshioka, H.; Misumi, T.; Miyauchi, E.; Ninomiya, K.; Murata, Y.; Takeshita, M.; Kinoshita, F.; Fujishita, T.; Sugawara, S.; et al. Clinical impact of hypomagnesemia induced by necitumumab plus cisplatin and gemcitabine treatment in patients with advanced lung squamous cell carcinoma: a subanalysis of the NINJA study. Ther. Adv. Med Oncol. 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Kawaguchi, T.; Funakoshi, T.; Fujiwara, Y.; Yasuda, Y.; Ando, Y. Efficacy of Magnesium Supplementation in Cancer Patients Developing Hypomagnesemia Due to Anti-EGFR Antibody: A Systematic Review. Cancer Diagn. Progn. 2024, 4, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Gao, M.; Xu, X.; Liu, H.; Lu, K.; Song, Z.; Yu, J.; Liu, X.; Han, X.; Li, L.; et al. Elevated serum magnesium levels prompt favourable outcomes in cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint blockers. Eur. J. Cancer 2024, 213, 115069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Eguiluz, D.; Leyva-Islas, J.A.; Luvián-Morales, J.; Martínez-Roque, V.; Sánchez-López, M.; Trejo-Durán, G.E.; Jiménez-Lima, R.; Leyva-Rendón, F.J. Nutrient Recommendations for Cancer Patients Treated with Pelvic Radiotherapy, with or without Comorbidities. Rev. de Investig. Clin. organo del Hosp. de Enfermedades de la Nutr. 2018, 70, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochamat; Cuhls, H.; Marinova, M.; Kaasa, S.; Stieber, C.; Conrad, R.; Radbruch, L.; Mücke, M. A systematic review on the role of vitamins, minerals, proteins, and other supplements for the treatment of cachexia in cancer: a European Palliative Care Research Centre cachexia project. J. Cachex- Sarcopenia Muscle 2016, 8, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schloss, J.M.; Colosimo, M.; Airey, C.; Masci, P.P.; Linnane, A.W.; Vitetta, L. Nutraceuticals and chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN): A systematic review. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 32, 888–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schloss, J.; Colosimo, M.; Vitetta, L. Herbal medicines and chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN): A critical literature review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 57, 1107–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-W.; Liu, C.-T.; Su, Y.-L.; Tsai, M.-Y. A Narrative Review of Complementary Nutritional Supplements for Chemotherapy-induced Peripheral Neuropathy. Altern Ther Health Med. 2020, 26, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Loprinzi, C.L.; Qin, R.; Dakhil, S.R.; Fehrenbacher, L.; Flynn, K.A.; Atherton, P.; Seisler, D.; Qamar, R.; Lewis, G.C.; Grothey, A. Phase III Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Study of Intravenous Calcium and Magnesium to Prevent Oxaliplatin-Induced Sensory Neurotoxicity (N08CB/Alliance). J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, B.; Jahn, F.; Beckmann, J.; Unverzagt, S.; Müller-Tidow, C.; Jordan, K. Calcium and Magnesium Infusions for the Prevention of Oxaliplatin-Induced Peripheral Neurotoxicity: A Systematic Review. Oncology 2016, 90, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofthagen, C.; Tanay, M.; Perlman, A.; Starr, J.; Advani, P.; Sheffield, K.; Brigham, T. A Systematic Review of Nutritional Lab Correlates with Chemotherapy Induced Peripheral Neuropathy. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wesselink, E.; Winkels, R.M.; Van Baar, H.; Geijsen, A.J.M.R.; Van Zutphen, M.; Van Halteren, H.K.; Hansson, B.M.E.; Radema, S.A.; De Wilt, J.H.W.; Kampman, E.; et al. Dietary Intake of Magnesium or Calcium and Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy in Colorectal Cancer Patients. Nutrients 2018, 10, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morel, V.; Pickering, M.-E.; Goubayon, J.; Djobo, M.; Macian, N.; Pickering, G. Magnesium for Pain Treatment in 2021? State of the Art. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.; Deng, F.; Yu, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Huang, D.; Zhou, H. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial to Evaluate the Therapeutic Effect of Magnesium-L-Threonate Supplementation for Persistent Pain After Breast Cancer Surgery. Breast Cancer: Targets Ther. 2023, 15, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.-H.; Jeon, J.; Mahajan, L.; Yan, Y.; Weichman, K.E.; Ricci, J.A. Postoperative Magnesium Sulfate Repletion Decreases Narcotic Use in Abdominal-Based Free Flap Breast Reconstruction. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 2024, 40, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbudak, I.H.; Yilmaz, S.; Ilhan, S.; Tanriverdi, S.Y.; Erdem, E. The effect of preemptive magnesium sulfate on postoperative pain in patients undergoing mastectomy: a clinical trial. Clin Nutr. 2023, 27, 7907–7913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crockett, S.D.; Greer, K.B.; Heidelbaugh, J.J.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Hanson, B.J.; Sultan, S. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the Medical Management of Opioid-Induced Constipation. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kistemaker, K.; Sijani, F.; Brinkman, D.; de Graeff, A.; Burchell, G.; Steegers, M.; van Zuylen, L. Pharmacological prevention and treatment of opioid-induced constipation in cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2024, 125, 102704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessoku, T.; Higashibata, T.; Morioka, Y.; Naya, N.; Koretaka, Y.; Ichikawa, Y.; Hisanaga, T.; Nakajima, A. Naldemedine and Magnesium Oxide as First-Line Medications for Opioid-Induced Constipation: A Comparative Database Study in Japanese Patients With Cancer Pain. Cureus 2024, 16, e55925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kistemaker, K.; de Graeff, A.; Crul, M.; de Klerk, G.; van de Ven, P.; van der Meulen, M.; van Zuylen, L.; Steegers, M. Magnesium hydroxide versus macrogol/electrolytes in the prevention of opioid-induced constipation in incurable cancer patients: study protocol for an open-label, randomized controlled trial (the OMAMA study). BMC Palliat. Care 2023, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, R.; Echizen, H. Clinically Significant Drug Interactions with Antacids. Drugs 2011, 71, 1839–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, C.; McElduff, A. An Unusual Cause of Hypocalcaemia: Magnesium Induced Inhibition of Parathyroid Hormone Secretion in a Patient with Subarachnoid Haemorrhage. Crit. Care Resusc. 2006, 8, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, M.P.; Dresser, L.; Raboud, J.; McGeer, A.; Rea, E.; Richardson, S.E.; Mazzulli, T.; Loeb, M.; Louie, M. Adverse Events Associated with High-Dose Ribavirin: Evidence from the Toronto Outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2007, 27, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohitnavy, M.; Lohitnavy, O.; Thangkeattiyanon, O.; Srichai, W. Reduced oral itraconazole bioavailability by antacid suspension. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2005, 30, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallet, L.; Huang, A. Coadministration of Gatifloxacin and Multivitamin Preparation Containing Minerals: Potential Treatment Failure in an Elderly Patient. Ann. Pharmacother. 2005, 39, 150–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naggar, V.F.; Khalil, S.A. Effect of magnesium trisilicate on nitrofurantoin absorption. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1979, 25, 857–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auwercx, J.; Rybarczyk, P.; Kischel, P.; Dhennin-Duthille, I.; Chatelain, D.; Sevestre, H.; Van Seuningen, I.; Ouadid-Ahidouch, H.; Jonckheere, N.; Gautier, M. Mg2+ Transporters in Digestive Cancers. Nutrients 2021, 13, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, A.; Naghshi, S.; Sadeghi, O.; Larijani, B.; Esmaillzadeh, A. Total, Dietary, and Supplemental Magnesium Intakes and Risk of All-Cause, Cardiovascular, and Cancer Mortality: A Systematic Review and Dose–Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Adv. Nutr. Int. Rev. J. 2021, 12, 1196–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’connor, E.A.; Evans, C.V.; Ivlev, I.; Rushkin, M.C.; Thomas, R.G.; Martin, A.; Lin, J.S. Vitamin and Mineral Supplements for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Cancer. JAMA 2022, 327, 2334–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kordiak, J.; Bielec, F.; Jabłoński, S.; Pastuszak-Lewandoska, D. Role of Beta-Carotene in Lung Cancer Primary Chemoprevention: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Y.; Sun, J.; Yu, J.; Wang, C.; Su, J. Dietary Intakes of Calcium, Iron, Magnesium, and Potassium Elements and the Risk of Colorectal Cancer: a Meta-Analysis. Biol. Trace Element Res. 2018, 189, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.-C.; Pang, Z.; Liu, Q.-F. Magnesium intake and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 66, 1182–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Zhong, X.; Tang, K.; Wu, G.; Jiang, Y. Serum magnesium levels and lung cancer risk: a meta-analysis. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 16, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapelle, N.; Martel, M.; Toes-Zoutendijk, E.; Barkun, A.N.; Bardou, M. Recent advances in clinical practice: colorectal cancer chemoprevention in the average-risk population. Gut 2020, 69, 2244–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, H.-T.; Jeong, S.-Y.; Shin, A. The association between prescription drugs and colorectal cancer prognosis: a nationwide cohort study using a medication-wide association study. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemian, M.; Poustchi, H.; Sharafkhah, M.; Pourshams, A.; Mohammadi-Nasrabadi, F.; Hekmatdoost, A.; Malekzadeh, R. Iron, Copper, and Magnesium Concentration in Hair and Risk of Esophageal Cancer: A Nested Case-Control Study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 26, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Zhong, X.; Tang, K.; Wu, G.; Jiang, Y. Serum magnesium levels and lung cancer risk: a meta-analysis. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 16, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, T.; Li, S.; Hu, W.; Li, D.; Leng, S. Potential Micronutrients and Phytochemicals against the Pathogenesis of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Lung Cancer. Nutrients 2018, 10, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.R.; Sawka, A.M.; Adams, L.; Hatfield, N.; Hung, R.J. Vitamin and mineral supplements and thyroid cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2013, 22, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, F.; Cai, W.-S.; Li, J.-L.; Feng, Z.; Cao, J.; Xu, B. The Association Between Serum Levels of Selenium, Copper, and Magnesium with Thyroid Cancer: a Meta-analysis. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2015, 167, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.K.; Tungalag, T.; Lee, S.-J.; Kim, S.-J. Methyl Jasmonate-induced Increase in Intracellular Magnesium Promotes Apoptosis in Breast Cancer Cells. Anticancer. Res. 2024, 44, 1087–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, P.M.V.; Bezerra, D.L.C.; dos Santos, L.R.; Santos, R.d.O.; Melo, S.R.d.S.; Morais, J.B.S.; Severo, J.S.; Vieira, S.C.; Marreiro, D.D.N. Magnesium in Breast Cancer: What Is Its Influence on the Progression of This Disease? Biol. Trace Element Res. 2017, 184, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Song, M.; Kim, M.S.; Natarajan, P.; Do, R.; Myung, W.; Won, H.-H. An atlas of associations between 14 micronutrients and 22 cancer outcomes: Mendelian randomization analyses. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, P.M.V.; Bezerra, D.L.C.; dos Santos, L.R.; Santos, R.d.O.; Melo, S.R.d.S.; Morais, J.B.S.; Severo, J.S.; Vieira, S.C.; Marreiro, D.D.N. Magnesium in Breast Cancer: What Is Its Influence on the Progression of This Disease? Biol. Trace Element Res. 2017, 184, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-Q.; Long, W.-Q.; Mo, X.-F.; Zhang, N.-Q.; Luo, H.; Lin, F.-Y.; Huang, J.; Zhang, C.-X. Direct and indirect associations between dietary magnesium intake and breast cancer risk. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, M.-H.; Dai, Q.; Millen, A.E.; Nie, J.; Edge, S.B.; Trevisan, M.; Shields, P.G.; Freudenheim, J.L. Associations of intakes of magnesium and calcium and survival among women with breast cancer: results from Western New York Exposures and Breast Cancer (WEB) Study. Am J Cancer Res. 2016, 6, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, D.L.C.; Mendes, P.M.V.; Melo, S.R.d.S.; dos Santos, L.R.; Santos, R.d.O.; Vieira, S.C.; Henriques, G.S.; Freitas, B.d.J.e.S.d.A.; Marreiro, D.D.N. Hypomagnesemia and Its Relationship with Oxidative Stress Markers in Women with Breast Cancer. Biol. Trace Element Res. 2021, 199, 4466–4474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Tan, Y.; Xiang, P.; Luo, Y.; Peng, J.; Xiao, H.; Liu, F. Diet-Related Risk Factors for Cervical Cancer: Data from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2018. Nutr. Cancer 2023, 75, 1892–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Glubb, D.M.; O’mara, T.A. Dietary Factors and Endometrial Cancer Risk: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Yang, H.; Mao, Y. Magnesium and liver disease. Ann. Transl. Med. 2019, 7, 578–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Guo, J.; Li, W.; Li, C.; Zhu, X.; Liu, Y.; Wu, X. PPM1H is down-regulated by ATF6 and dephosphorylates p-RPS6KB1 to inhibit progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Ther. - Nucleic Acids 2023, 33, 164–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Paragomi, P.; Wang, R.; Liang, F.; Luu, H.N.; Behari, J.; Yuan, J. High serum magnesium is associated with lower risk of hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Cancer 2023, 129, 2341–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parisse, S.; Ferri, F.; Persichetti, M.; Mischitelli, M.; Abbatecola, A.; Di Martino, M.; Lai, Q.; Carnevale, S.; Lucatelli, P.; Bezzi, M.; et al. Low serum magnesium concentration is associated with the presence of viable hepatocellular carcinoma tissue in cirrhotic patients. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehata, A.K.; Singh, V.; Vikas; Srivastava, P.; Koch, B.; Kumar, M.; Muthu, M.S. Chitosan nanoplatform for the co-delivery of palbociclib and ultra-small magnesium nanoclusters: dual receptor targeting, therapy and imaging. Nanotheranostics 2024, 8, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Betallu, M.; Bhalara, S.R.; Sapnar, K.B.; Tadke, V.B.; Meena, K.; Srivastava, A.; Kundu, G.C.; Gorain, M. Hybrid Inorganic Complexes as Cancer Therapeutic Agents: In-vitro Validation. Nanotheranostics 2023, 7, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Qin, R.; Smith, T.J.; Atherton, P.J.; Barton, D.L.; Sturtz, K.; Dakhil, S.R.; Anderson, D.M.; Flynn, K.; Puttabasavaiah, S.B.; et al. North Central Cancer Treatment Group N10C2 (Alliance). Menopause 2015, 22, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, F.I.; Cittadini, A.R.M.; Maier, J.A.M. Magnesium and tumors: Ally or foe? Cancer Treat. Rev. 2009, 35, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Wark, P.; Lau, R.; Norat, T.; Kampman, E. Magnesium intake and colorectal tumor risk: a case-control study and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 96, 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahabir, S.; Wei, Q.; Barrera, S.L.; Dong, Y.Q.; Etzel, C.J.; Spitz, M.R.; Forman, M.R. Dietary magnesium and DNA repair capacity as risk factors for lung cancer. Carcinog. 2008, 29, 949–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, J.A.; Nasulewicz-Goldeman, A.; Simonacci, M.; Boninsegna, A.; Mazur, A.; Wolf, F.I. Insights Into the Mechanisms Involved in Magnesium-Dependent Inhibition of Primary Tumor Growth. Nutr. Cancer 2007, 59, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, J.; Romani, A.M.; Valentin-Torres, A.M.; A Luciano, A.; Kitchen, C.M.R.; Funderburg, N.; Mesiano, S.; Bernstein, H.B. Magnesium Decreases Inflammatory Cytokine Production: A Novel Innate Immunomodulatory Mechanism. J. Immunol. 2012, 188, 6338–6346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, T.Y.; van Dam, R.M.; E Manson, J.; Hu, F.B. Magnesium intake and plasma concentrations of markers of systemic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction in women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 1068–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, C.; Aaseth, J.O. Magnesium: a scoping review for Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2023. Food Nutr. Res. 2023, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leidi, M.; Wolf, F.; Maier, J.A.M. Magnesium and cancer: more questions than answers. In Magnesium in the Central Nervous System [Internet]; Vink, R., Nechifor, M., Eds.; University of Adelaide Press: Adelaide (AU), 2011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schwalfenberg, G.K.; Genuis, S.J. The Importance of Magnesium in Clinical Healthcare. Scientifica 2017, 2017, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).