Submitted:

01 June 2023

Posted:

07 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

PICOs:

2.1. Search Strategy and Data Extraction

2.2. Selection Criteria

2.3. Methodological Quality Assessment

2.4. Assessment of Risk of Bias

2.5. Data Appraisal, Synthesis, and Statistical Analysis

2.6. Sensitivity Analysis

2.7. Mapping

3. Results

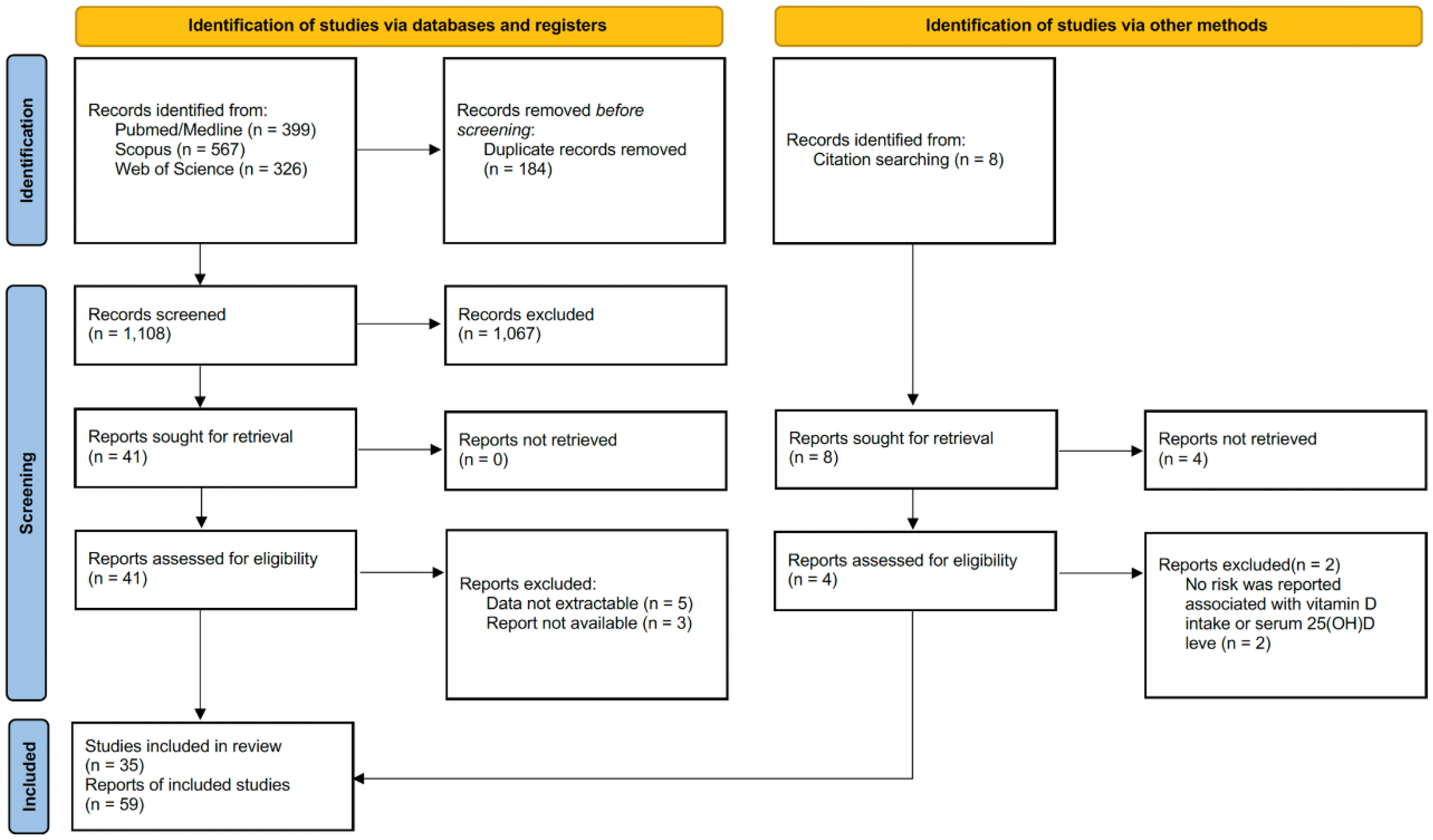

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Baseline Characteristics of the Meta-analyses

| First author/year | Cancer type | Characteristics of the primary studies | Vit-D exposure | Total number of studies (n) | Total sample size (n) | Outcome | NoP studies included for incidence (n) | NoP studies included for mortality (n) | Effect size (ES) and confidence interval (CI) for incidence | Effect size (ES) and confidence interval (CI) for mortality |

| Boughanem 2022 (a)x (21) | Colorectal cancer | Case-control, prospective cohort | Vit-D intake | 31 | 926.237 | Incidence | 12 | N/A | OR = 0.75 (0.67-0.85) | N/A |

| Boughanem 2022 (b)y (21) | Colorectal cancer | Case-control, prospective cohort | Vit-D intake | 31 | 926.237 | Incidence | 6 | N/A | HR = 0.94 (0.79-1.11) | N/A |

| Cheema 2022 (19) | Total cancer | RCTs | Vit-D intake | 13 | 109.543 | Incidence, mortality | 12 | 7 | RR = 0.99 (0.94-1.04) | RR = 0.93 (0.84-1.03) |

| Chen 2022 (a) (36) | Gastric cancer | Case-control, prospective cohort | Serum 25(OH)D | 11 | N/A | Incidence | 11 | N/A | OR = 0.93 (0.77-1.11) | N/A |

| Chen 2022 (b) (36) | Gastric cancer | Case-control, prospective cohort | Vit-D intake | 11 | N/A | Incidence | 4 | N/A | OR = 1.00 (0.86-1.16) | N/A |

| Ekmekcioglu 2017 (12) | Colorectal cancer | Case-control, prospective cohort | Serum 25(OH)D | 14 | 12.110 | Incidence | 14 | N/A | RR = 0.62 (0.56-0.70) | N/A |

| Gao 2018 (37) | Prostate cancer | Case-control, prospective cohort | Serum 25(OH)D | 19 | 48.369 | Incidence | 19 | N/A | RR = 1.15 (1.06-1.24) | N/A |

| Goulão 2018 (18) | Total cancer | RCTs | Vit-D intake | 30 | 18.808 | Incidence | 24 | 7 | RR = 1.03 (0.91-1.15) | RR = 0.88 (0.70-1.09) |

| Guo 2020 (13) | Liver cancer | Case-control, prospective cohort | Serum 25(OH)D | 6 | 60.811 | Incidence | 6 | N/A | RR = 0.78 (0.63-0.95) | N/A |

| Guo 2022 (20) | Total cancer | RCTs | Vit-D intake | 26 | 121.529 | Incidence, mortality | 19 | 11 | RR = 0.98 (0.94-1.02) | RR = 0.88 (0.80-0.96) |

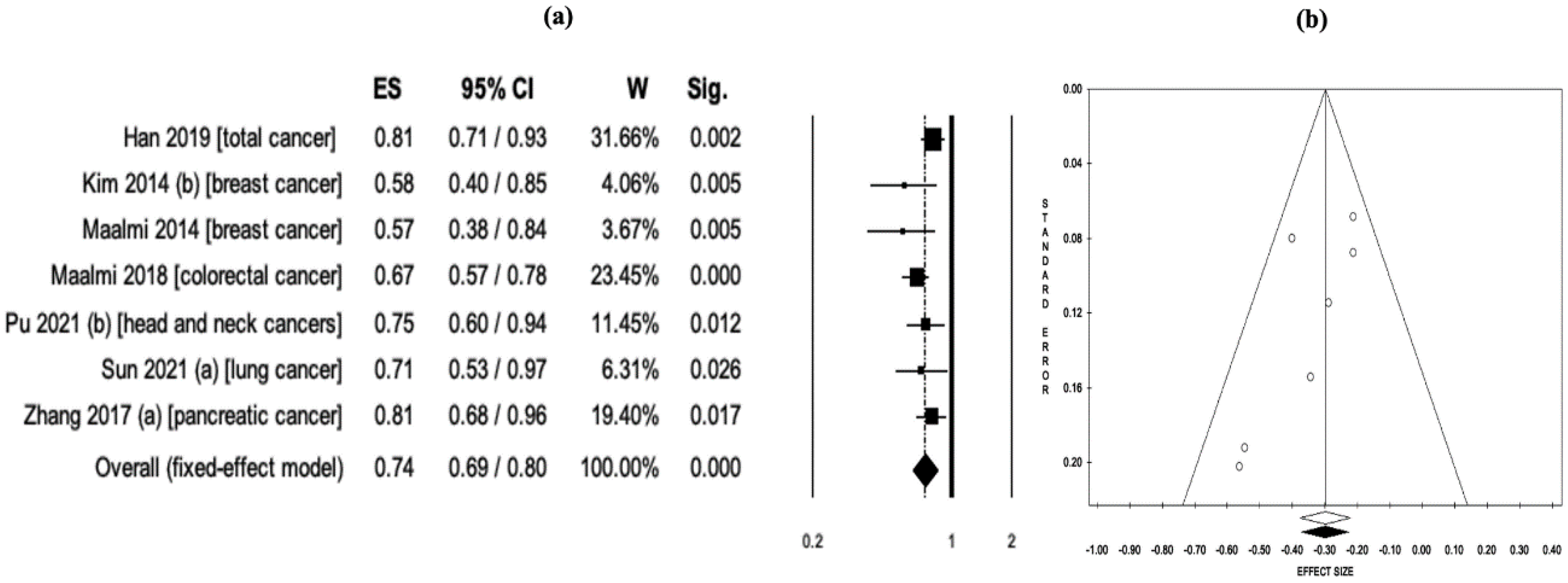

| Han 2019 (38) | Total cancer | Prospective cohort | Serum 25(OH)D | 23 | 170.618 | Incidence, mortality | 8 | 16 | RR = 0.86 (0.73-1.02) | RR = 0.81 (0.71-0.93) |

| Haykal 2019 (39) | Total cancer | RCTs | Vit-D intake | 10 | 79.055 | Incidence, mortality | 9 | 5 | RR = 0.96 (0.86-1.07) | RR = 0.87 (0.79-0.96) |

| Hernandez-Alonso 2023 (a) (14) | Colorectal cancer | Case-control | Serum 25(OH)D | 28 | 140.112 | Incidence | 11 | N/A | OR = 0.61 (0.52-0.71) | N/A |

| Hernandez-Alonso 2023 (b) (14) | Colorectal cancer | Prospective cohort | Serum 25(OH)D | 28 | 140.112 | Incidence | 6 | N/A | HR = 0.80 (0.66-0.97) | N/A |

| Huncharek 2009 (40) | Colorectal cancer | Case-control, cohort | Vit-D intake | 60 | N/R | Incidence | 10 | N/A | RR = 0.94 (0.83-1.06) | N/A |

| Keum 2014 (41) | Total cancer | RCTs | Vit-D intake | 4 | 45.151 | Incidence, mortality | 4 | 3 | RR = 1.00 (0.94-1.06) | RR = 0.88 (0.78-0.98) |

| Khayatzadeh 2015 (a) (42) | Gastric cancer | Case-control, cohort | Vit-D intake | 7 | 59.626 | Incidence | 4 | N/A | OR = 1.09 (0.94-1.25) | N/A |

| Khayatzadeh 2015 (b) (42) | Gastric cancer | Case-control, cohort | Serum 25(OH)D | 7 | 59.626 | Incidence | 3 | N/A | OR = 0.92 (0.74-1.14) | N/A |

| Kim 2014 (a) (43) | Breast cancer | Case-control, cohort | Vit-D intake | 30 | 762.859 | Incidence | 12 | N/A | RR = 0.95 (0.88-1.01) | N/A |

| Kim 2014 (b) (43) | Breast cancer | Case-control, cohort | Serum 25(OH)D | 30 | 762.859 | Incidence, mortality | 14 | 4 | RR = 0.92 (0.83-1.02) | RR = 0.58 (0.40-0.85) |

| Lee 2011 (44) | Colorectal cancer | Case-control, cohort | Serum 25(OH)D | 8 | N/A | Incidence | 8 | N/A | OR = 0.66 (0.54-0.81) | N/A |

| Liao 2015 (45) | Bladder cancer | Case-control, cohort | Serum 25(OH)D | 5 | 89.610 | Incidence | 5 | N/A | RR = 0.75 (0.65-0.87) | N/A |

| Liao 2020 (22) | Ovarian cancer | Case-control, cohort | Vit-D intake | 29 | 963.604 | Incidence | 6 | N/A | RR = 0.80 (0.67-0.95) | N/A |

| Liu 2015 (46) | Colorectal cancer | Cohort | Vit-D intake | 47 | 870.330 | Incidence | 17 | N/A | RR = 0.87 (0.77-0.99) | N/A |

| Liu 2017 (a) (23) | Lung cancer | Case-control, cohort | Vit-D intake | 22 | 813.801 | Incidence | 6 | N/A | OR = 0.89 (0.83-0.97) | N/A |

| Liu 2017 (b) (23) | Lung cancer | Case-control, cohort | Serum 25(OH)D | 22 | 813.801 | Incidence, mortality | 8 | 3 | OR = 0.72 (0.61-0.85) | OR = 0.39 (0.28-0.54) |

| Liu 2018 (a)* (47) | Pancreatic cancer | Case-control, cohort, RCTs |

Vit-D intake | 25 | 1.213.821 | Incidence | 11 | N/A | RR = 0.90 (0.83-0.98) | N/A |

| Liu 2018 (b)** (47) | Pancreatic cancer | Case-control, cohort, RCTs |

Vit-D intake | 25 | 1.213.821 | Incidence | 14 | N/A | RR = 0.79 (0.73-0.85) | N/A |

| Lopez-Caleya 2022 (48) | Colorectal cancer | Case-control | Vit-D intake | 55 | 55.522 | Incidence | 23 | N/A | OR = 0.96 (0.93-0.98) | N/A |

| Maalmi 2014*** (49) | Breast cancer | Cohort | Serum 25(OH)D | 5 | 4.413 | Mortality | N/A | 3 | N/A | HR = 0.57 (0.38-0.84) |

| Maalmi 2018*** (50) | Colorectal cancer | Cohort | Serum 25(OH)D | 11 | 7.718 | Mortality | N/A | 6 | N/A | HR = 0.67 (0.57-0.78) |

| Pu 2021 (a) (51) | Head and neck cancer | Case-control, cohort | Vit-D intake | 16 | 81.908 | Incidence | 3 | N/A | OR = 0.77 (0.65-0.92) | N/A |

| Pu 2021 (b) (51) | Head and neck cancer | Case-control, cohort | Serum 25(OH)D | 16 | 81.908 | Incidence, mortality | 5 | 3 | OR = 0.68 (0.59-0.78) | OR = 0.75 (0.60-0.94) |

| Shahvazi 2019 (52) | Prostate cancer | Clinical trials | Vit-D intake | 22 | 1.902 | Mortality | N/A | 3 | N/A | RR = 1.05 (0.81-1.36) |

| Sun 2021 (a) (24) | Lung cancer | Case-control, cohort, RCTs | Serum 25(OH)D | 40 | 1.566.662 | Incidence, mortality | 16 | 9 | RR = 0.91 (0.84-0.98) | RR = 0.71 (0.53-0.97) |

| Sun 2021 (b) (24) | Lung cancer | Case-control, cohort, RCTs | Vit-D intake | 40 | 1.566.662 | Incidence | 4 | N/A | RR = 0.90 (0.80-1.03) | N/A |

| Wei 2018 (a) (53) | Lung cancer | Case-control, cohort | Serum 25(OH)D | 16 | 280.127 | Incidence | 12 | N/A | RR = 1.04 (0.94-1.15) | N/A |

| Wei 2018 (b) (53) | Lung cancer | Case-control, cohort | Vit-D intake | 16 | 280.127 | Incidence | 5 | N/A | RR = 0.85 (0.74-0.98) | N/A |

| Xu 2021 (54) | Colorectal cancer | Case-control, cohort | Vit-D intake | 25 | 911.638 | Incidence | 21 | N/A | OR = 0.87 (0.82-0.92) | N/A |

| Zhang 2017 (a) (55) | Pancreatic cancer | Case-control, cohort | Serum 25(OH)D | 12 | 893.168 | Incidence, mortality | 5 | 5 | RR = 1.02 (0.66-1.57) | HR = 0.81 (0.68-0.96) |

| Zhang 2017 (b) (55) | Pancreatic cancer | Case-control, cohort | Vit-D intake | 12 | 893.168 | Incidence | 2 | N/A | RR = 1.11 (0.67-1.86) | N/A |

| Zhang 2019 (56) | Total cancer | RCTs | Vit-D intake | 10 | 81.362 | Incidence, mortality | 10 | 7 | RR = 0.99 (0.94-1.03) | RR = 0.87 (0.79-0.95) |

| Zhang 2021 (57) | Liver cancer | Kohort | Serum 25(OH)D | 6 | 6.357 | Incidence | 6 | N/A | HR = 0.53 (0.41-0.68) | N/A |

| Zhang 2022 (58) | Total cancer | RCTs | Vit-D intake | 12 | 72.669 | Incidence, mortality | 11 | 6 | RR = 0.99 (0.93-1.06) | RR = 0.96 (0.80-1.16) |

| Zhao 2016 (59) | Bladder cancer | Case-control, cohort | Serum 25(OH)D | 7 | 90.757 | Incidence | 7 | N/A | OR = 0.76 (0.66-1.87) | N/A |

| Zhou 2020 (60) | Breast cancer | RCTs | Vit-D intake | 8 | 72.275 | Incidence | 6 | N/A | RR = 1.04 (0.85-1.29) | N/A |

3.3. Outcomes

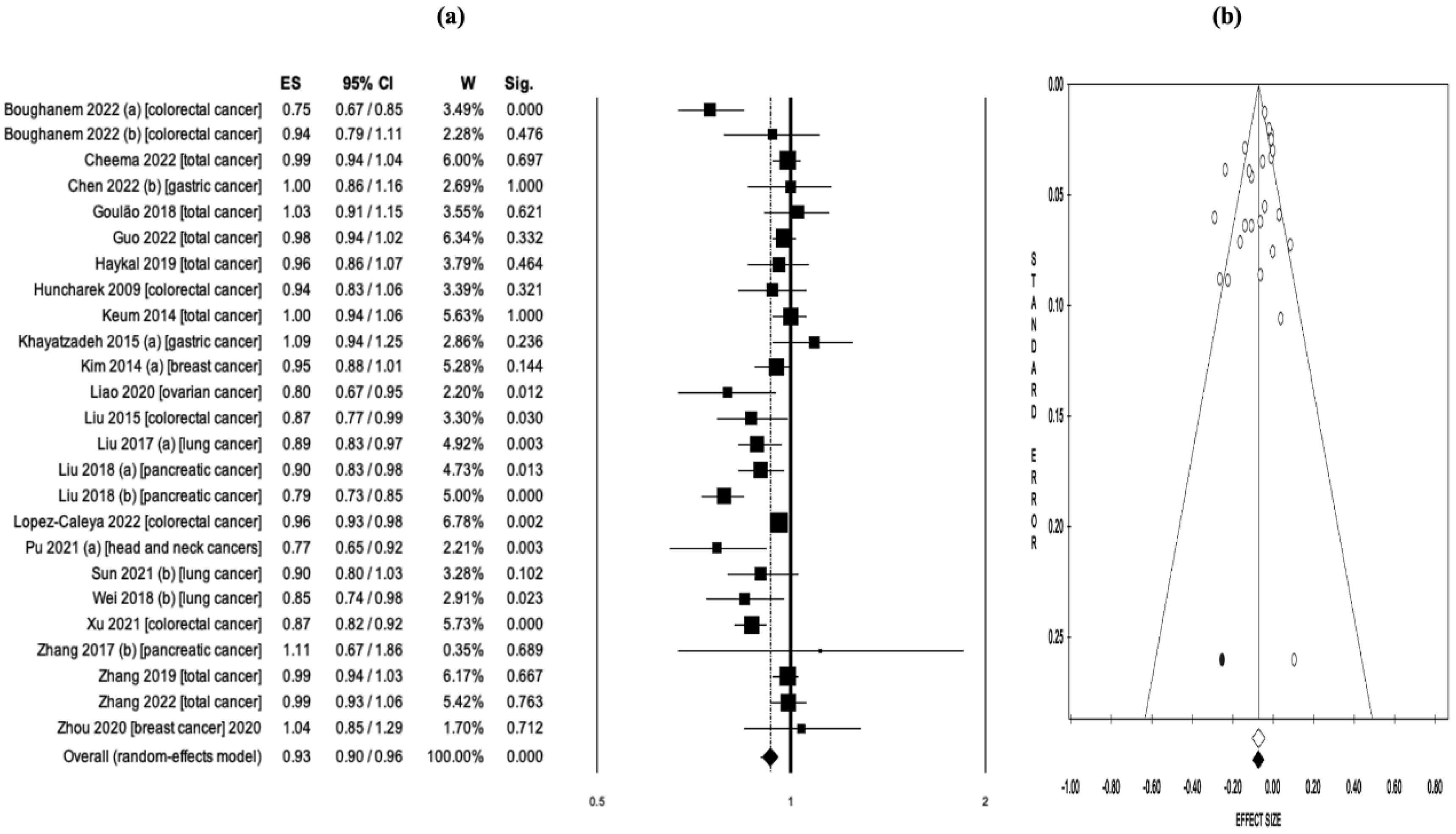

3.4. Vitamin D Intake and Cancer Risk/Mortality

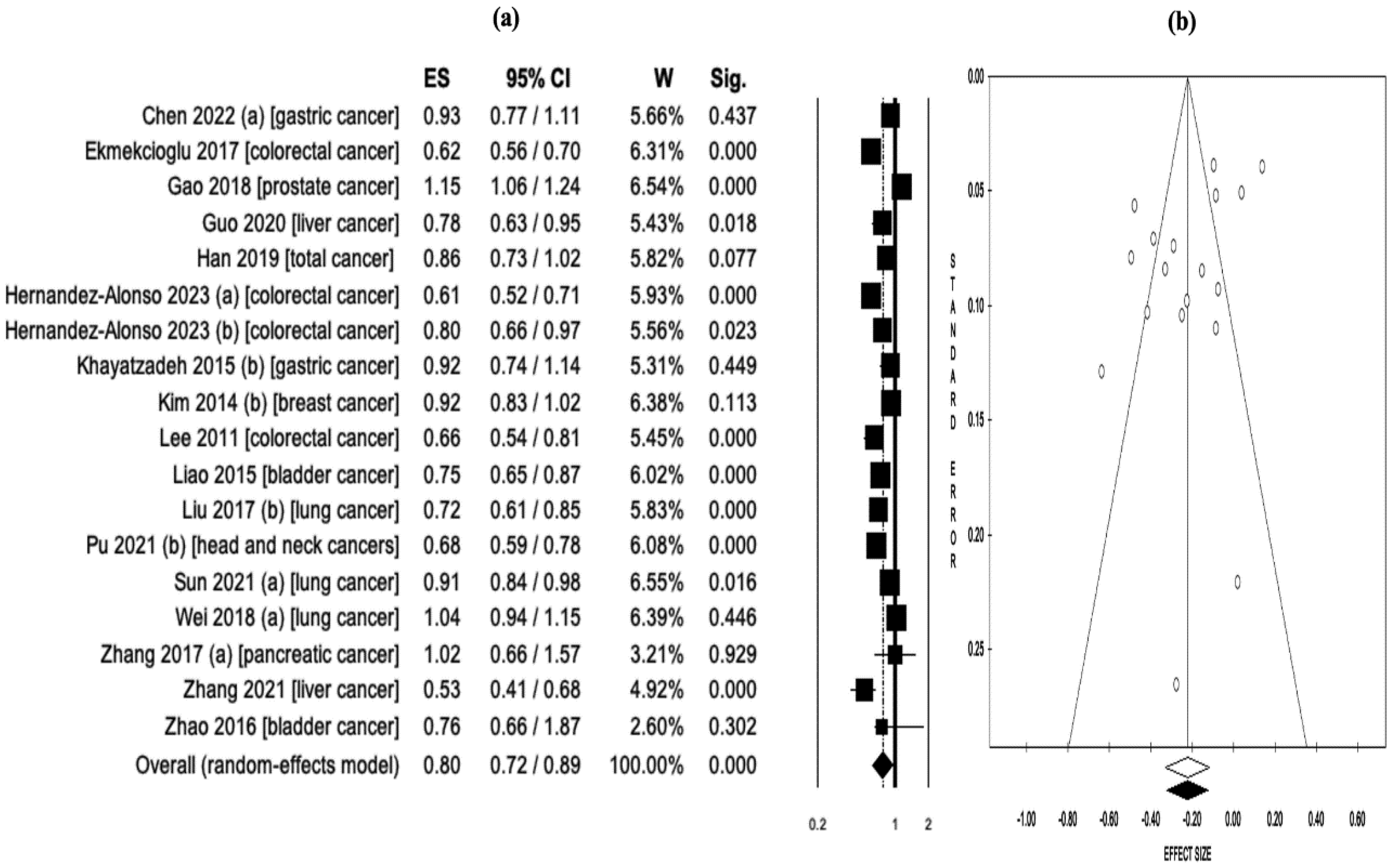

3.5. Serum 25-hidroxyvitamin-D Levels and Cancer Risk/Mortality

3.6. Subgroup Analysis

| Analysis | Model | Number of reports (n) | Effect size (ES) [OR or RR] | 95% CI | p value | I2 | p value | Intercept | Tau (t) | p value |

| Vitamin D intake and cancer risk* | ||||||||||

| Total cancer | Fixed | 7 | 0.99** | 0.97-1.01 | 0.300 | 0.00 | 0.983 | 0.37 | 0.72 | 0.506 |

| Colorectal cancer | Random | 6 | 0.89** | 0.83-0.96 | 0.002 | 79.4 | < 0.001 | -2.11 | -1.70 | 0.164 |

| Lung cancer | Fixed | 3 | 0.88** | 0.83-0.94 | < 0.001 | 0.00 | 0.817 | -0.72 | -0.59 | 0.658 |

| RCTs*** | Fixed | 8 | 0.99** | 0.97-1.01 | 0.320 | 0.00 | 0.988 | 0.49 | 1.35 | 0.227 |

| Observational | Random | 14 | 0.90** | 0.86-0.95 | < 0.001 | 68.43 | < 0.001 | -1.09 | -1.51 | 0.156 |

| Serum 25 (OH)D levels ve and cancer risk* | ||||||||||

| Colorectal cancer | Fixed | 4 | 0.65** | 0.60-0.70 | < 0.001 | 48.4 | 0.121 | 3.23 | 1.21 | 0.351 |

| Lung cancer | Random | 3 | 0.89** | 0.75-1.05 | 0.178 | 85.84 | 0.001 | -4.32 | -0.68 | 0.619 |

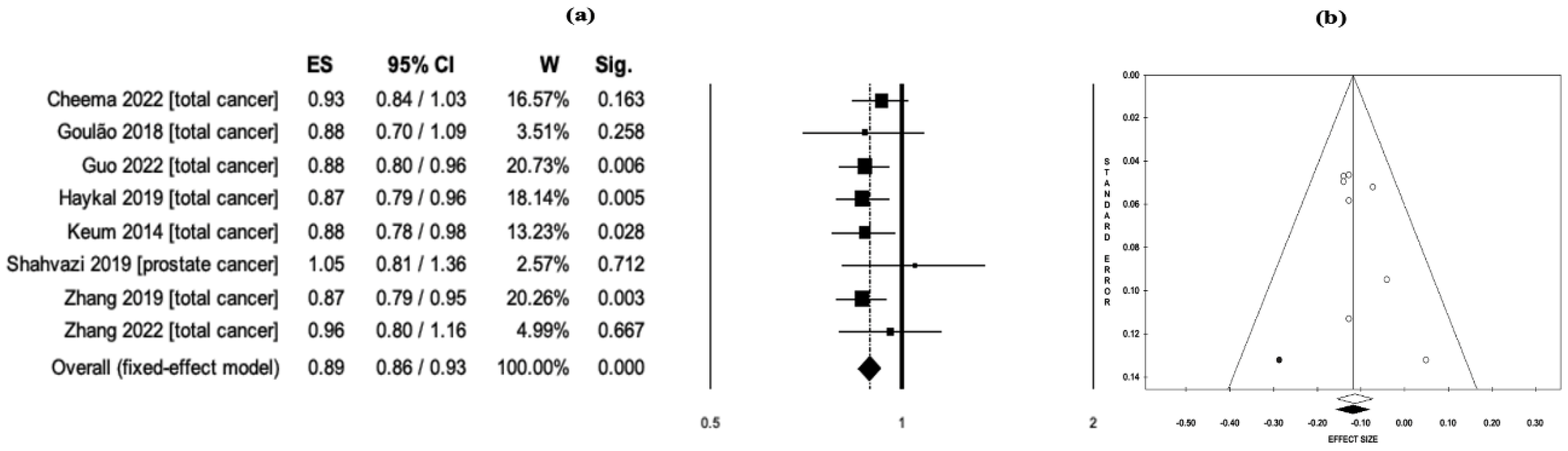

| Vitamin D intake and cancer related mortality* | ||||||||||

| Total cancer | Fixed | 7 | 0.89**** | 0.85-0.93 | < 0.001 | 0.00 | 0.929 | 0.77 | 0.98 | 0.372 |

| RCTs*** | Fixed | 7 | 0.89**** | 0.85-0.93 | < 0.001 | 0.00 | 0.929 | 0.77 | 0.98 | 0.372 |

3.7. Mapping

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data availability statement

Conflicts of Interest statement

Ethics approval statement

Abbreviations

References

- Matthews HK, Bertoli C, de Bruin RAM. Cell cycle control in cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2022;23:74–88. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-021-00404-3. [CrossRef]

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A ve ark. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021;71:209-249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660. [CrossRef]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):7-33. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21654. [CrossRef]

- Arayici ME, Basbinar Y, Ellidokuz H. The impact of cancer on the severity of disease in patients affected with COVID-19: an umbrella review and meta-meta-analysis of systematic reviews and meta-analyses involving 1,064,476 participants. Clin Exp Med. 2022:1-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10238-022-00911-3. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Health Estimates 2020: Deaths by Cause, Age, Sex, by Country and by Region, 2000-2019. WHO; 2020. Accessed March 11, 2023. who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/ghe-leading-causes-of-death.

- Gil Á, Plaza-Diaz J, Mesa MD. Vitamin D: Classic and Novel Actions. Ann Nutr Metab. 2018;72(2):87-95. https://doi.org/10.1159/000486536. [CrossRef]

- Raiten DJ, Picciano MF. Vitamin D and health in the 21st century: bone and beyond. Executive summary. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(6Suppl):1673S-7S. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1673S. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz A, Grant WB. Vitamin D and Cancer: An Historical Overview of the Epidemiology and Mechanisms. Nutrients. 2022;14(7):1448. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14071448. [CrossRef]

- Jeon SM, Shin E. Exploring vitamin D metabolism and function in cancer. Exp Mol Med. 2019;50:1-14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-018-0038-9. [CrossRef]

- Li M, Chen P, Li J, Chu R, Xie D, Wang H. Review: the impacts of circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels on cancer patient outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(7):2327-36. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2013-4320. [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez Mena JM, Brenner H. Vitamin D and cancer: an overview on epidemiological studies. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;810:17-32.

- Ekmekcioglu C, Haluza D, Kundi M. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Status and Risk for Colorectal Cancer and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Epidemiological Studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(2):127. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14020127. [CrossRef]

- Guo XF, Zhao T, Han JM, Li S, Li D. Vitamin D and liver cancer risk: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2020;29(1):175-182. https://doi.org/10.6133/apjcn.202003_29(1).0023. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Alonso P, Boughanem H, Canudas S, Becerra-Tomás N, Fernández de la Puente M, Babio N, et al. Circulating vitamin D levels and colorectal cancer risk: A meta-analysis and systematic review of case-control and prospective cohort studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2023;63(1):1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2021.1939649. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury R, Kunutsor S, Vitezova A, Oliver-Williams C, Chowdhury S, Kiefte-de-Jong JC, et al. Vitamin D and risk of cause specific death: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational cohort and randomised intervention studies. BMJ. 2014;348:g1903. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1903. [CrossRef]

- Feldman D, Krishnan AV, Swami S, Giovannucci E, Feldman BJ. The role of vitamin D in reducing cancer risk and progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(5):342-57. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3691. [CrossRef]

- Giovannucci E. The epidemiology of vitamin D and cancer incidence and mortality: a review (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16(2):83-95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-004-1661-4. [CrossRef]

- Goulão B, Stewart F, Ford JA, MacLennan G, Avenell A. Cancer and vitamin D supplementation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;107(4):652-663. https://doi.org/doi:10.1093/ajcn/nqx047. [CrossRef]

- Cheema HA, Fatima M, Shahid A, Bouaddi O, Elgenidy A, Rehman AU, et al. Vitamin D supplementation for the prevention of total cancer incidence and mortality: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon. 2022;8(11):e11290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11290. [CrossRef]

- Guo Z, Huang M, Fan D, Hong Y, Zhao M, Ding R, et al. Association between vitamin D supplementation and cancer incidence and mortality: A trial sequential meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022:1-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2022.2056574. [CrossRef]

- Boughanem H, Canudas S, Hernandez-Alonso P, Becerra-Tomás N, Babio N, Salas-Salvadó J, et al. Vitamin D Intake and the Risk of Colorectal Cancer: An Updated Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of Case-Control and Prospective Cohort Studies. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(11):2814. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13112814. [CrossRef]

- Liao MQ, Gao XP, Yu XX, Zeng YF, Li SN, Naicker N, et al. Effects of dairy products, calcium and vitamin D on ovarian cancer risk: a meta-analysis of twenty-nine epidemiological studies. Br J Nutr. 2020;124(10):1001-1012. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114520001075. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Dong Y, Lu C, Wang Y, Peng L, Jiang M, et al. Meta-analysis of the correlation between vitamin D and lung cancer risk and outcomes. Oncotarget. 2017;8(46):81040-81051. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.18766. [CrossRef]

- Sun K, Zuo M, Zhang Q, Wang K, Huang D, Zhang H. Anti-Tumor Effect of Vitamin D Combined with Calcium on Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutr Cancer. 2021;73(11-12):2633-2642. https://doi.org/10.1080/01635581.2020.1850812. [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org10.1136/bmj.n71.

- Brooke BS, Schwartz TA, Pawlik TM. MOOSE Reporting Guidelines for Meta-analyses of Observational Studies. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(8):787-788. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0522. [CrossRef]

- Furlan AD, Pennick V, Bombardier C, van Tulder M; Editorial Board, Cochrane Back Review Group. 2009 updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Back Review Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(18):1929-41. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b1c99f. [CrossRef]

- Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4008. [CrossRef]

- Whiting P, Savović J, Higgins JP, Caldwell DM, Reeves BC, Shea B, et al. ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;69:225-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.06.005. [CrossRef]

- Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629-34. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [CrossRef]

- Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088-101.

- Duval S, Tweedie R. A nonparametric “Trim and Fill” method of accounting for Publication Bias in Meta-Analysis. J Am Stat Assoc. 2000;95:89–98.

- Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, Cochrane Collaboration, 2008. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [M]. Wiley-Blackwell.

- ProMeta-3 professional statistical software for conducting meta-analysis. It is based on ProMeta 2.1 deployed by Internovi in 2015. https://idostatistics.com/prometa3/.

- Balduzzi S, Rücker G, Schwarzer G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: a practical tutorial. In Evidence-Based Mental Health. 2019;22:153-160.

- Chen X, Li L, Liang Y, Huang T, Zhang H, Fan S, Sun W, Wang Y. Relationship of vitamin D intake, serum 25(OH) D, and solar ultraviolet-B radiation with the risk of gastric cancer: A meta-analysis. J Cancer Res Ther. 2022;18(5):1417-1424. https://doi.org/10.4103/jcrt.jcrt_527_21. [CrossRef]

- Gao J, Wei W, Wang G, Zhou H, Fu Y, Liu N. Circulating vitamin D concentration and risk of prostate cancer: A dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2018;14:95-104. https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S149325. [CrossRef]

- Han J, Guo X, Yu X, Liu S, Cui X, Zhang B, et al. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D and Total Cancer Incidence and Mortality: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Nutrients. 2019;11(10):1-17. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11102295. [CrossRef]

- Haykal T, Samji V, Zayed Y, Gakhal I, Dhillon H, Kheiri B, et al. The role of vitamin D supplementation for primary prevention of cancer: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2019;9(6):480-488. https:///doi.org/10.1080/20009666.2019.1701839. [CrossRef]

- Huncharek M, Muscat J, Kupelnick B. Colorectal cancer risk and dietary intake of calcium, vitamin D, and dairy products: A meta-analysis of 26,335 cases from 60 observational studies. Nutr Cancer. 2009;61(1):47-69. https://doi.org/10.1080/01635580802395733. [CrossRef]

- Keum N, Giovannucci E. Vitamin D supplements and cancer incidence and mortality: A meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2014;111(5):976-80. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.294. [CrossRef]

- Khayatzadeh S, Feizi A, Saneei P, Esmaillzadeh A. Vitamin D intake, serum Vitamin D levels, and risk of gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Res Med Sci. 2015;20(8):790-6. https://doi.org/10.4103/1735-1995.168404. [CrossRef]

- Kim Y, Je Y. Vitamin D intake, blood 25(OH)D levels, and breast cancer risk or mortality: A meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2014;110(11):2772-84. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.175. [CrossRef]

- Lee JE, Li H, Chan AT, Hollis BW, Lee IM, Stampfer MJ, et al. Circulating levels of vitamin D and colon and rectal cancer: the Physicians’ Health Study and a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2011;4(5):735-43. https://doi.org10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0289.

- Liao Y, Huang JL, Qiu MX, Ma ZW. Impact of serum vitamin D level on risk of bladder cancer: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Tumour Biol. 2015;36(3):1567-72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13277-014-2728-9. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Yu Q, Zhu Z, Zhang J, Chen M, Tang P, et al. Vitamin and multiple-vitamin supplement intake and incidence of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Med Oncol. 2015;32(1):1-10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-014-0434-5. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Wang X, Sun X, Lu S, Liu S. Vitamin intake and pancreatic cancer risk reduction: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(13):e0114. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000010114. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Caleya JF, Ortega-Valín L, Fernández-Villa T, Delgado-Rodríguez M, Martín-Sánchez V, Molina AJ. The role of calcium and vitamin D dietary intake on risk of colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Cancer Causes Control. 2022;33(2):167-182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-021-01512-3. [CrossRef]

- Maalmi H, Ordóñez-Mena JM, Schöttker B, Brenner H. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and survival in colorectal and breast cancer patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50(8):1510-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2014.02.006. [CrossRef]

- Maalmi H, Walter V, Jansen L, Boakye D, Schöttker B, Hoffmeister M, et al. Association between blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and survival in colorectal cancer patients: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2018;10(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10070896. [CrossRef]

- Pu Y, Zhu G, Xu Y, Zheng S, Tang B, Huang H, et al. Association Between Vitamin D Exposure and Head and Neck Cancer: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis. Front Immunol. 2021;12(February):1-11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.627226. [CrossRef]

- Shahvazi S, Soltani S, Ahmadi SM, de Souza RJ, Salehi-Abargouei A. The Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials. Horm Metab Res. 2019;51(1):11-21. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0774-8809. [CrossRef]

- Wei H, Jing H, Wei Q, Wei G, Heng Z. Associations of the risk of lung cancer with serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level and dietary vitamin D intake: A dose-response PRISMA meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(37):e12282. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000012282. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Qian M, Hong J, Ng DM, Yang T, Xu L, Ye X. The effect of vitamin D on the occurrence and development of colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021;36(7):1329-1344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-021-03879-w. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Huang XZ, Chen WJ, Wu J, Chen Y, Wu CC, et al. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels, vitamin D intake, and pancreatic cancer risk or mortality: A meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(38):64395-406. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.18888. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Niu W. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on vitamin D supplement and cancer incidence and mortality. Biosci Rep. 2019;39(11):BSR20190369. https://doi.org/10.1042/BSR20190369. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Jiang X, Li X, Găman MA, Kord-Varkaneh H, Rahmani J, et al. Serum Vitamin D Levels and Risk of Liver Cancer: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Nutr Cancer. 2021;73(8):1-9. https://doi.org/10.1080/01635581.2020.1797127. [CrossRef]

- Zhang R, Zhang Y, Liu Z, Pei Y, Xu P, Chong W, et al. Association between Vitamin D Supplementation and Cancer Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(15):3717. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14153717. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Chen C, Pan W, Gao M, He W, Mao R, et al. Comparative efficacy of vitamin D status in reducing the risk of bladder cancer: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Nutrition. 2016;32(5):515-23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2015.10.023. [CrossRef]

- Zhou L, Chen B, Sheng L, Turner A. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on the risk of breast cancer: a trial sequential meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;182(1):1-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-020-05669-4. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).