Submitted:

10 May 2025

Posted:

12 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

2.2. Measurements

3. Results and Discussion

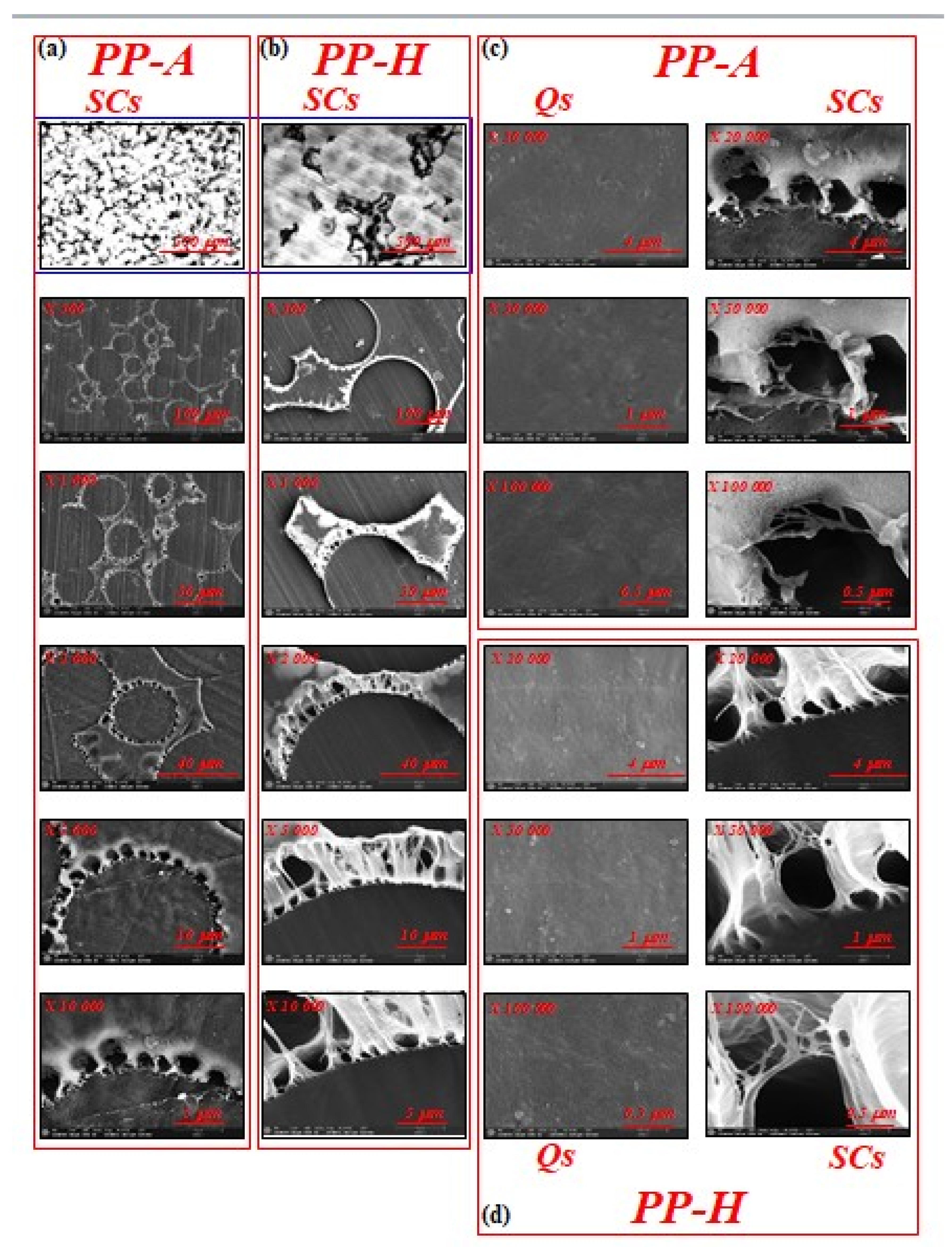

3.1. Microstructure Investigation

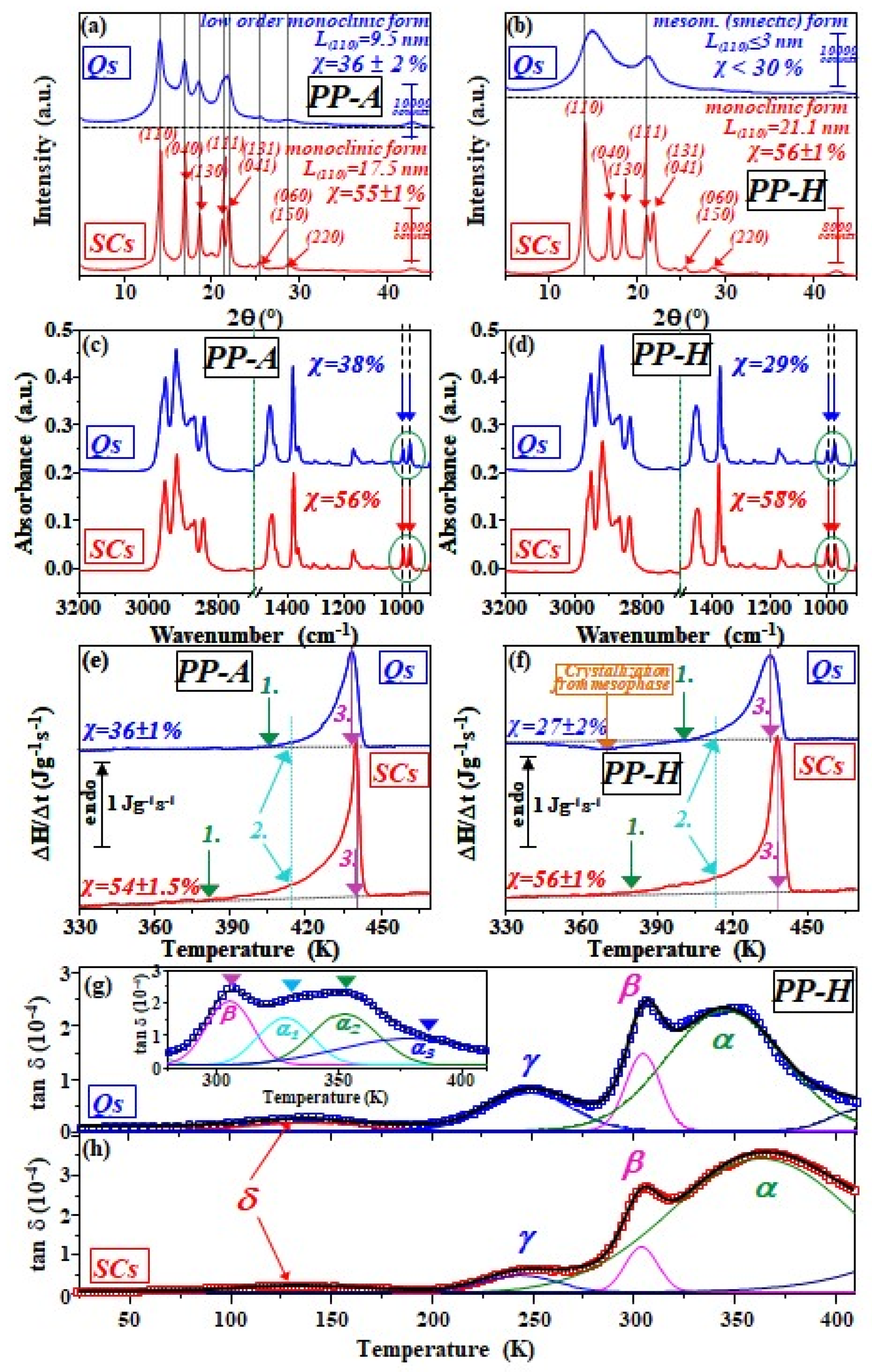

3.2. WAXD Study

3.3. ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy

3.4. Calorimetric Study

3.5. DRS Study

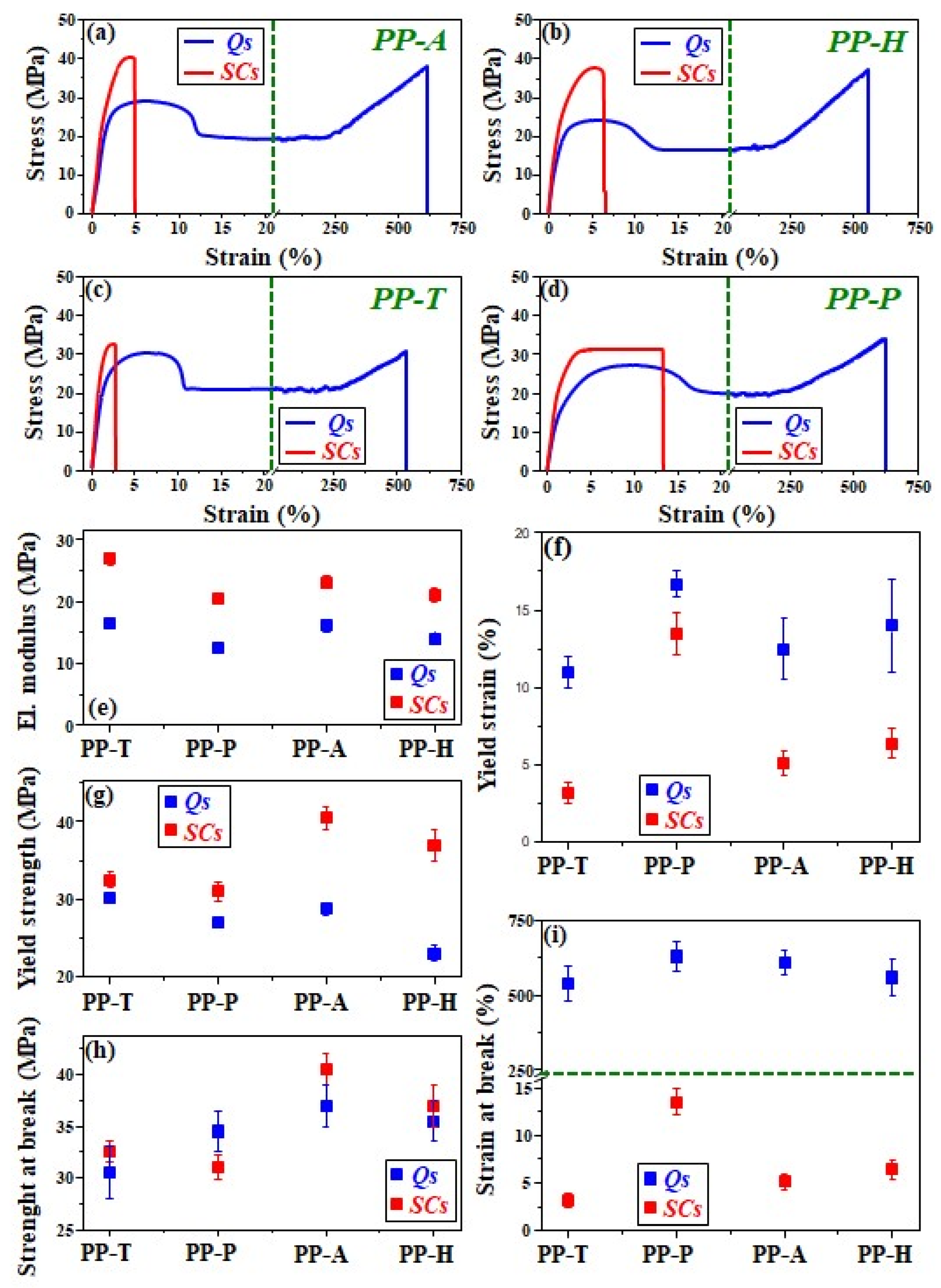

3.6. Mechanical Study

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aboulfaraj, M., G'Sell, C., Ulrich, B., Dahoun, A., 1995. In situ observation of the plastic deformation of polypropylene spherulites under uniaxial tension and simple shear in the scanning electron microscope. Polymer 36, 731-742. [CrossRef]

- Addeo, A., 2005. Polypropylene Handbook. Hanser Gardner.

- Amer, I., van Reenen, A., Mokrani, T., 2015. Molecular weight and tacticity effect on morphological and mechanical properties of Ziegler–Natta catalyzed isotactic polypropylenes. Polímeros 25, 556-563. [CrossRef]

- An, H., Li, X., Geng, Y., Wang, Y., Wang, X., Li, L., Li, Z., Yang, C., 2008. Shear-Induced Conformational Ordering, Relaxation, and Crystallization of Isotactic Polypropylene. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 112, 12256-12262. [CrossRef]

- An, Y., Wang, S., Li, R., Shi, D., Gao, Y., Song, L., 2019. Effect of different nucleating agent on crystallization kinetics and morphology of polypropylene. e-Polymers 19, 32-39. [CrossRef]

- Androsch, R., 2008. In Situ Atomic Force Microscopy of the Mesomorphic−Monoclinic Phase Transition in Isotactic Polypropylene. Macromolecules 41, 533-535. [CrossRef]

- Androsch, R., Di Lorenzo, M.L., Schick, C., Wunderlich, B., 2010. Mesophases in polyethylene, polypropylene, and poly(1-butene). Polymer 51, 4639-4662. [CrossRef]

- Ariff, Z., Ariffin, A., Jikan, S., Abdul Rahim, N., 2012. Rheological Behaviour of Polypropylene Through Extrusion and Capillary Rheometry, in: Dogan, F. (Ed.), Polypropylene pp. 29-48.

- Ariyama, T., Mori, Y., Kaneko, K., 1997. Tensile properties and stress relaxation of polypropylene at elevated temperatures. Polym. Eng. Sci. 37, 81-90. [CrossRef]

- Arranz-Andrés, J., Peña, B., Benavente, R., Pérez, E., Cerrada, M.L., 2007. Influence of isotacticity and molecular weight on the properties of metallocenic isotactic polypropylene. Eur. Polym. J. 43, 2357-2370. [CrossRef]

- Arvidson, S.A., Khan, S.A., Gorga, R.E., 2010. Mesomorphic−α-Monoclinic Phase Transition in Isotactic Polypropylene: A Study of Processing Effects on Structure and Mechanical Properties. Macromolecules 43, 2916-2924. [CrossRef]

- Auriemma, F., De Rosa, C., Corradini, P., 2005. Solid Mesophases in Semicrystalline Polymers: Structural Analysis by DiffractionTechniques, in: Allegra, G. (Ed.), Interphases and Mesophases in Polymer Crystallization II. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 1-74.

- Banford, H.M., Fouracre, R., Faucitano, A., Buttafava, A., Martinotti, F., 1996a. The influence of γ-irradiation and chemical structure on the dielectric properties of PP. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 48, 129-130. [CrossRef]

- Banford, H.M., Fouracre, R.A., Faucitano, A., Buttafava, A., Martinotti, F., 1996b. The influence of chemical structure on the dielectric behavior of polypropylene IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 3, 594-598. [CrossRef]

- Bassett, D.C., 1981. Principles of polymer morphology. Cambridge [Eng.], New York.

- Bassett, D.C., Keller, A., Mitsuhashi, S., 1963. New features in polymer crystal growth from concentrated solutions. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: General Papers 1, 763-788. [CrossRef]

- Bassett, D.C., Olley, R.H., 1984. On the lamellar morphology of isotactic polypropylene spherulites. Polymer 25, 935-943. [CrossRef]

- Bassett, D.C., Vaughan, A.S., 1985. On the lamellar morphology of melt-crystallized isotactic polystyrene. Polymer 26, 717-725. [CrossRef]

- Beuguel, Q., Mija, A., Vergnes, B., Peuvrel-Disdier, E., 2018. Structural, thermal, rheological and mechanical properties of polypropylene/graphene nanoplatelets composites: Effect of particle size and melt mixing conditions. Polym. Eng. Sci. 58, 1937-1944. [CrossRef]

- Bogoeva-Gaceva, G., 2014. Advances in polypropylene based materials. Contributions, Section of Natural, Mathematical and Biotechnical Sciences 35, 121-138. [CrossRef]

- Bohning, M., Goering, H., Fritz, A., Brzezinka, K.-W., Turky, G., Schönhals, A., Schartel, B., 2005. Dielectric study of molecular mobility in poly(propylene-graft-maleic anhydride)/clay nanocomposites. Macromolecules 38, 2764-2774. [CrossRef]

- Brandrup, J., Immergut, E.H., Grulke, E.A., 1999. Polymer Handbook Wiley-Interscience, New York.

- Brandrup, J., Immergut EH., 1975. Polymer Handbook. Wiley, New York.

- Brucato, V., Piccarolo, S., La Carrubba, V., 2002. An experimental methodology to study polymer crystallization under processing conditions. The influence of high cooling rates. Chem. Eng. Sci. 57, 4129-4143. [CrossRef]

- Brückner, S., Meille, S.V., Petraccone, V., Pirozzi, B., 1991. Polymorphism in isotactic polypropylene. Prog. Polym. Sci. 16, 361-404. [CrossRef]

- Burfield, D.R., Loi, P.S.T., 1988. The use of infrared spectroscopy for determination of polypropylene stereoregularity. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 36, 279-293. [CrossRef]

- Butler, M.F., Donald, A.M., Bras, W., Mant, G.R., Derbyshire, G.E., Ryan, A.J., 1995. A Real-Time Simultaneous Small- and Wide-Angle X-ray Scattering Study of In-Situ Deformation of Isotropic Polyethylene. Macromolecules 28, 6383-6393. [CrossRef]

- Caldas, V., Brown, G.R., Nohr, R.S., MacDonald, J.G., Raboin, L.E., 1994. The structure of the mesomorphic phase of quenched isotactic polypropylene. Polymer 35, 899-907. [CrossRef]

- Castejón, M.L., Tiemblo P, Gómez-Elvira JM., 2001. Photo-oxidation of thick isotactic polypropylene films. II. Evolution of the low temperature relaxations and of the melting endotherm along the kinetic stages. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 71, 99-111. [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.-M., Li, L., 2005. Direct Observation of the Growth of Lamellae and Spherulites by AFM, in: Kausch, H.-H. (Ed.), Intrinsic Molecular Mobility and Toughness of Polymers II. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 1-41.

- Chang, B., Schneider, K., Vogel, R., Heinrich, G., 2017. Influence of Annealing on Mechanical αc-Relaxation of Isotactic Polypropylene: A Study from the Intermediate Phase Perspective. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 302, 1700291. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W., Li, X.-y., Liu, Y.-p., Li, J., Zhou, W.-m., Chen, L., Li, L.-b., 2015. The spatial correlation between crystalline and amorphous orientations of isotactic polypropylene during plastic deformation: An in situ observation with FTIR imaging. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 33, 613-620. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W., Zhang, Q., Zhao, J., Li, L., 2020. Molecular and thermodynamics descriptions of flow-induced crystallization in semi-crystalline polymers. Journal of Applied Physics 127. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.Z.D., Janimak, J.J., Zhang, A., Hsieh, E.T., 1991. Isotacticity effect on crystallization and melting in polypropylene fractions: 1. Crystalline structures and thermodynamic property changes. Polymer 32, 648-655. [CrossRef]

- Chodák, I., 1998. High modulus polyethylene fibres: preparation, properties and modification by crosslinking. Prog. Polym. Sci. 23, 1409-1442. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Y., Saraf, R., 2001. A direct correlation function for mesomorphic polymers and its application to the 'smectic' phase of isotactic polpropylene. Polymer 42, 5865-5870. [CrossRef]

- Cong, Y., Hong, Z., Qi, Z., Zhou, W., Li, H., Liu, H., Chen, W., Wang, X., Li, L., 2010. Conformational Ordering in Growing Spherulites of Isotactic Polypropylene. Macromolecules 43, 9859-9864. [CrossRef]

- Cong, Y., Hong, Z., Zhou, W., Chen, W., Su, F., Li, H., Li, X., Yang, K., Yu, X., Qi, Z., Li, L., 2012. Conformational Ordering on the Growth Front of Isotactic Polypropylene Spherulite. Macromolecules 45, 8674-8680. [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, C., Auriemma, F., Circelli, T., Waymouth, R.M., 2002. Crystallization of the α and γ Forms of Isotactic Polypropylene as a Tool To Test the Degree of Segregation of Defects in the Polymer Chains. Macromolecules 35, 3622-3629. [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, C., Auriemma, F., Tarallo, O., Malafronte, A., Di Girolamo, R., Esposito, S., Piemontesi, F., Liguori, D., Morini, G., 2017. The “Nodular” α Form of Isotactic Polypropylene: Stiff and Strong Polypropylene with High Deformability. Macromolecules 50, 5434-5446. [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, M.L., Righetti, M.C., 2018. Crystallization-induced formation of rigid amorphous fraction. POLYMER CRYSTALLIZATION 1, e10023. [CrossRef]

- Di Sacco, F., Saidi, S., Hermida-Merino, D., Portale, G., 2021. Revisiting the Mechanism of the Meso-to-α Transition of Isotactic Polypropylene and Ethylene–Propylene Random Copolymers. Macromolecules 54, 9681-9691. [CrossRef]

- Dintilhac, N., Lewandowski, S., Planes, M., Lectez, A.S., Dantras, E., 2023. Tuning dielectric response of polyethylene by low gamma dose: Molecular mobility study improvement by dipolar probes implementation. J. Non•Cryst. Solids 621, 122606. [CrossRef]

- Dudic, D., Kostoski, D., Djokovic, V., Dramicanin, M., 2002. Formation and behaviour of low-temperature melting peak of quenched and annealed isotactic polypropylene. Polym. Int. 51, 111-116. [CrossRef]

- Dudić, D., Kostoski D, Djoković V, Dramićanin MD., 2002. Formation and behaviour of low-temperature melting peak of quenched and annealed isotactic polypropylene. Polym. Int. 51, 111-116. [CrossRef]

- Dudić, D.k., Kostoski, D.a., Djoković, V., Dramićanin, M.D., 2002. Formation and behaviour of low-temperature melting peak of quenched and annealed isotactic polypropylene. Polym. Int. 51, 111-116. [CrossRef]

- Farrow, G., 1963. Crystallinity, ‘crystallite size’ and melting point of polypropylene. Polymer 4, 191-197. [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, A., Ferracini, E., Mazzavillani, A., Malta, V., 2000. A New X-Ray Study of the Quenched Isotactic Polypropylene Transition by Annealing. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part B 39, 109-129. [CrossRef]

- Fouracre, R.A., MacGregor, S.J., Judd, M., Banford, H.M., 1999. Condition monitoring of irradiated polymeric cables. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 54, 209-211. [CrossRef]

- Fournie, R., 1990. All film power capacitors. Endurance tests and degradation mechanisms. Bulletin de la Direction des etudes et recherches. Serie B, Reseaux electriques, materiels electriques 1, 1-31.

- Fu, X., Jia, W., Li, X., Wang, Y., Wang, Z., Liu, C., Shen, C., Shao, C., 2019. Phase transitions of the rapid-compression-induced mesomorphic isotactic polypropylene under high-pressure annealing. J. Polym. Sci., Part B: Polym. Phys. 57, 651-661. [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, Y., Kida, T., Yamaguchi, M., 2023. Mechanical properties of isotactic polypropylene with nodular or spherulite morphologies. Polym. Eng. Sci. 63, 4043-4050. [CrossRef]

- Furuta, M., Kojima, K., 1986. Morphological study of deformation process for linear polyethylene. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part B 25, 349-364. [CrossRef]

- G'sell, C., Favier, V., Hiver, J.M., Dahoun, A., Philippe, M.J., Canova, G.R., 1997. Microstructure transformation and stress-strain behavior of isotactic polypropylene under large plastic deformation. Polym. Eng. Sci. 37, 1702-1711. [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y., Wang, G., Cong, Y., Bai, L., Li, L., Yang, C., 2009. Shear-Induced Nucleation and Growth of Long Helices in Supercooled Isotactic Polypropylene. Macromolecules 42, 4751-4757. [CrossRef]

- Gitsas, A., Floudas, G., 2008. Pressure Dependence of the Glass Transition in Atactic and Isotactic Polypropylene. Macromolecules 41, 9423-9429. [CrossRef]

- Gomez, M.A., Tanaka, H., Tonelli, A.E., 1987. High-resolution solid-state 13C nuclear magnetic resonance study of isotactic polypropylene polymorphs. Polymer 28, 2227-2232. [CrossRef]

- Guleria, D., Ge, S., Cardon, L., Vervoort, S., den Doelder, J., 2024. Impact of resin density and short-chain branching distribution on structural evolution and enhancement of tensile modulus of MDO-PE films. Polym. Test. 139, 108560. [CrossRef]

- Haftka, S., Könnecke, K., 1991. Physical properties of syndiotactic polypropylene. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part B 30, 319-334. [CrossRef]

- Haggenmueller, R., Guthy, C., Lukes, J.R., Fischer, J.E., Winey, K.I., 2007. Single Wall Carbon Nanotube/Polyethylene Nanocomposites: Thermal and Electrical Conductivity. Macromolecules 40, 2417-2421. [CrossRef]

- Hanna, L.A., Hendra, P.J., Maddams, W., Willis, H.A., Zichy, V., Cudby, M.E.A., 1988. Vibrational spectroscopic study of structural changes in isotactic polypropylene below the melting point. Polymer 29, 1843-1847. [CrossRef]

- Hara, T., 1967. Dielectric Property of Some Polymers in Low Temperature Region. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 6, 147-150. [CrossRef]

- Hedvig, P., 1977. Dielectric Spectroscopy of Polymers. Academia Kiado, Budapest.

- Heinen, W., 1959. Infrared determination of the crystallinity of polypropylene. J. Polym. Sci. 38, 545-547. [CrossRef]

- Hendra, P.J., Vile, J., Willis, H.A., Zichy, V., Cudby, M.E.A., 1984. The effect of cooling rate upon the morphology of quenched melts of isotactic polypropylenes. Polymer 25, 785-790. [CrossRef]

- Hine, P., Broome, V., Ward, I., 2005. The incorporation of carbon nanofibres to enhance the properties of self reinforced, single polymer composites. Polymer 46, 10936-10944. [CrossRef]

- Hoyos, M., Tiemblo, P., Gómez-Elvira, J.M., 2007. The role of microstructure, molar mass and morphology on local relaxations in isotactic polypropylene. The α relaxation. Polymer 48, 183-194. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S., Li, H., Jiang, S., 2019. Crystal structure and unique lamellar thickening for poly(l-lactide) induced by high pressure. Polymer 175, 81-86. [CrossRef]

- Huy, T.A., Adhikari, R., Lüpke, T., Henning, S., Michler, G.H., 2004. Molecular deformation mechanisms of isotactic polypropylene in α- and β-crystal forms by FTIR spectroscopy. J. Polym. Sci., Part B: Polym. Phys. 42, 4478-4488. [CrossRef]

- Imai, M., Kaji, K., 2006. Polymer crystallization from the metastable melt: The formation mechanism of spherulites. Polymer 47, 5544-5554. [CrossRef]

- Jia, C., Das, P., Kim, I., Yoon, Y.-J., Tay, C.Y., Lee, J.-M., 2022. Applications, treatments, and reuse of plastics from electrical and electronic equipment. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 110, 84-99. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C., Miao, C., Zhou, J., Yuan, M., 2025. Insights into damage mechanisms and advances in numerical simulation of spherulitic polymers. Polymer 318, 128001. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q., Zhao, Y., Zhang, C., Yang, J., Xu, Y., Wang, D., 2016. In-situ investigation on the structural evolution of mesomorphic isotactic polypropylene in a continuous heating process. Polymer 105, 133-143. [CrossRef]

- Jourdan, C., Cavaille, J.Y., Perez, J., 1989. Mechanical relaxations in polypropylene: A new experimental and theoretical approach. J. Polym. Sci., Part B: Polym. Phys. 27, 2361-2384. [CrossRef]

- Karger-Kocsis, J., Bárány, T., 2019. Polypropylene Handbook Morphology, Blends and Composites: Morphology, Blends and Composites.

- Kida, T., Fukuda, Y., Yamaguchi, M., Otsuki, Y., Kimura, T., Mizukawa, T., Murakami, T., Hato, K., Okawa, T., 2023. Morphological transformation of extruded isotactic polypropylene film from the Mesophase to α-form crystals. React. Funct. Polym. 191, 105682. [CrossRef]

- Kida, T., Yamaguchi, M., 2022. Role of Rigid–Amorphous chains on mechanical properties of polypropylene solid using DSC, WAXD, SAXS, and Raman spectroscopy. Polymer 249, 124834. [CrossRef]

- Kilic, A., Jones, K., Shim, E., Pourdeyhimi, B., 2016. Surface crystallinity of meltspun isotactic polypropylene filaments. Macromolecular Research 24, 25-30. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M., Park, T.Y., Hong, S., 2021. Experimental determination of the plastic deformation and fracture behavior of polypropylene composites under various strain rates. Polym. Test. 93, 107010. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.C., Ahn, W., Kim, C.Y., 1997. A study on multiple melting of isotactic polypropylene. Polym. Eng. Sci. 37, 1003-1011. [CrossRef]

- Kissin, Y.V., 1985. Isospecific Polymerization of Olefins With Heterogeneous Ziegler-Natta Catalysts. Springer: Berlin.

- Konishi, T., Nishida, K., Kanaya, T., 2006. Crystallization of Isotactic Polypropylene from Prequenched Mesomorphic Phase. Macromolecules 39, 8035-8040. [CrossRef]

- Konishi, T., Nishida, K., Kanaya, T., Kaji, K., 2005. Effect of Isotacticity on Formation of Mesomorphic Phase of Isotactic Polypropylene. Macromolecules 38, 8749-8754. [CrossRef]

- Kostoski, D., Galovic, S., Suljovrujic, E., 2004. Charge trapping and dielectric relaxations of gamma irradiated radiolytically oxidized highly oriented LDPE. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 69 245-248. [CrossRef]

- Lamberti, G., Brucato, V., 2003. Real-time orientation and crystallinity measurements during the isotactic polypropylene film-casting process. J. Polym. Sci., Part B: Polym. Phys. 41, 998-1008. [CrossRef]

- Lanyi, F.J., Wenzke, N., Kaschta, J., Schubert, D.W., 2018. A method to reveal bulk and surface crystallinity of Polypropylene by FTIR spectroscopy - Suitable for fibers and nonwovens. Polym. Test. 71, 49-55. [CrossRef]

- Lanyi, F.J., Wenzke, N., Kaschta, J., Schubert, D.W., 2020. On the Determination of the Enthalpy of Fusion of α-Crystalline Isotactic Polypropylene Using Differential Scanning Calorimetry, X-Ray Diffraction, and Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy: An Old Story Revisited. Adv. Eng. Mater. 22, 1900796. [CrossRef]

- Laura, D.M., Keskkula, H., Barlow, J.W., Paul, D.R., 2003. Effect of rubber particle size and rubber type on the mechanical properties of glass fiber reinforced, rubber-toughened nylon 6. Polymer 44, 3347-3361. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M., Kim, C.-H., Koo, C.-S., Kim, B.-R., Lee, Y., 2003. The variation of structure and physical properties of XLPE during thermal aging process. Polymer (Korea) 27, 249-254.

- Li, J., Zhu, Z., Li, T., Peng, X., Jiang, S., Turng, L.-S., 2020. Quantification of the Young's modulus for polypropylene: Influence of initial crystallinity and service temperature. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 137, 48581. [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Liu, T., Zhao, L., Yuan, W.-k., 2011. Effect of compressed CO2 on the melting behavior and βα-recrystallization of β-form in isotactic polypropylene. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids 60, 137-143. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., Zhou, Y., Wang, X., Liu, H., Cheng, L., Liu, W., Li, S., Guo, J., Xu, Y., 2024. Failure mechanism of metallized film capacitors under DC field superimposed AC harmonic: From equipment to material. High Voltage 9, 1081-1089. [CrossRef]

- Liparoti, S., Sorrentino, A., Speranza, V., 2021. Morphology-Mechanical Performance Relationship at the Micrometrical Level within Molded Polypropylene Obtained with Non-Symmetric Mold Temperature Conditioning. Polymers 13, 462. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.-M., Juska, T.D., Harrison, I.R., 1986. Plastic deformation of polypropylene. Polymer 27, 247-249. [CrossRef]

- Luongo, J.P., 1960. Infrared study of polypropylene. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 3, 302-309. [CrossRef]

- Maddah, H., 2016. Polypropylene as a Promising Plastic: A Review. Am. J. Polym. Sci. 6, 1-11.

- Makarewicz, C., Safandowska, M., Idczak, R., Rozanski, A., 2022. Plastic Deformation of Polypropylene Studied by Positron Annihilation Lifetime Spectroscopy. Macromolecules 55, 10062-10076. [CrossRef]

- Martorana, A., Piccarolo, S., Sapoundjieva, D., 1999. SAXS/WAXS study of the annealing process in quenched samples of isotactic poly(propylene). Macromol. Chem. Phys. 200, 531-540. [CrossRef]

- McCrum, N.G., 1964. Density-independent relaxations in polypropylene. Journal of Polymer Science Part B: Polymer Letters 2, 495 - 498. [CrossRef]

- Michaeli, W., Gutberlet, D., Glißmann, M., 2001. Characterisation of the spherulite structure of polypropylene using light-microscope methods. Polym. Test. 20, 459-467. [CrossRef]

- Mileva, D., Androsch, R., Radusch, H.-J., 2009. Effect of structure on light transmission in isotactic polypropylene and random propylene-1-butene copolymers. Polym. Bull. 62, 561-571. [CrossRef]

- Mileva, D., Tranchida, D., Gahleitner, M., 2018. Designing polymer crystallinity: An industrial perspective. Polymer Crystallization 1, e10009. [CrossRef]

- Milicevic, D., Micic, M., Stamboliev, G., Leskovac, A., Mitric, M., Suljovrujic, E., 2012. Microstructure and crystallinity of polyolefins oriented via solid-state stretching at an elevated temperature. Fibers Polym. 13, 466-470. [CrossRef]

- Milicevic, D., Micic, M., Suljovrujic, E., 2014. Radiation-induced modification of dielectric relaxation spectra of polyolefins: polyethylenes vs. polypropylene. Polym. Bull. 71, 2317-2334. [CrossRef]

- Milicevic, D., Trifunovic, S., Galovic, S., Suljovrujic, E., 2007a. Thermal and crystallization behaviour of gamma irradiated PLLA. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 76, 1376-1380. [CrossRef]

- Milicevic, D., Trifunovic, S., Popovic, M., Vukasinovic-Milic, T., Suljovrujic, E., 2007b. The influence of orientation on the radiation-induced crosslinking/oxidative behavior of different PEs. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. B 260, 603-612. [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.L., 1960. On the existence of near-range order in isotactic polypropylenes. Polymer 1, 135-143. [CrossRef]

- Mollova, A., Androsch, R., Mileva, D., Gahleitner, M., Funari, S.S., 2013. Crystallization of isotactic polypropylene containing beta-phase nucleating agent at rapid cooling. Eur. Polym. J. 49, 1057-1065. [CrossRef]

- Montanari, G.C., Fabiani D, Palmieri F, Kaempfer D, Thomann R, Mülhaupt R., 2004. Modification of electrical properties and performance of EVA and PP insulation through nanostructure by organophilic silicates. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 11 754-762. [CrossRef]

- Moore, E.P., 1996. Polypropylene Handbook: Polymerization, Characterization, Properties, Processing, Applications. Hanser Publishers.

- Morosoff, N., Peterlin, A., 1972. Plastic deformation of polypropylene. IV. Wide-angle x-ray scattering in the neck region. Journal of Polymer Science Part A-2: Polymer Physics 10, 1237-1254. [CrossRef]

- Na, B., Lv, R., 2007. Effect of cavitation on the plastic deformation and failure of isotactic polypropylene. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 105, 3274-3279. [CrossRef]

- Natta, G., 1955. Une nouvelle classe de polymeres d'α-olefines ayant une régularité de structure exceptionnelle. J. Polym. Sci. 16, 143-154. [CrossRef]

- Nitta, K.-H., 2018. Tensile Properties in β-Modified Isotactic Polypropylene, in: Wang, W., Zeng, Y. (Eds.), Polypropylene - Polymerization and Characterization of Mechanical and Thermal Properties. IntechOpen, Rijeka.

- Nitta, K.-h., Odaka, K., 2009. Influence of structural organization on tensile properties in mesomorphic isotactic polypropylene. Polymer 50, 4080-4088. [CrossRef]

- Nitta, K.h., Yamaguchi, N., 2006. Influence of Morphological Factors on Tensile Properties in the Pre-yield Region of Isotactic Polypropylenes. Polym. J. 38, 122-131. [CrossRef]

- Norton, D.R., Keller, A., 1985. The spherulitic and lamellar morphology of melt-crystallized isotactic polypropylene. Polymer 26, 704-716. [CrossRef]

- Olivares, N., Tiemblo, P., Gomez-Elvira, J.M., 1999. Physicochemical processes along the early stages of the thermal degradation of isotactic polypropylene I. Evolution of the γ relaxation under oxidative conditions. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 65, 297-302. [CrossRef]

- Ozzetti, R.A., De Oliveira Filho, A.P., Schuchardt, U., Mandelli, D., 2002. Determination of tacticity in polypropylene by FTIR with multivariate calibration. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 85, 734-745. [CrossRef]

- Padden, F.J., Jr., Keith, H.D., 1959. Spherulitic Crystallization in Polypropylene. Journal of Applied Physics 30, 1479-1484. [CrossRef]

- Park, J., Eom, K., Kwon, O., Woo, S., 2001. Chemical Etching Technique for the Investigation of Melt-crystallized Isotactic Polypropylene Spherulite and Lamellar Morphology by Scanning Electron Microscopy. Microscopy and microanalysis : the official journal of Microscopy Society of America, Microbeam Analysis Society, Microscopical Society of Canada 7, 276-286.

- Pasquini, N., 2005. Polypropylene Handbook. Carl Hanser Verlag.

- Paukkeri, R., Lehtinen, A., 1993a. Thermal behaviour of polypropylene fractions: 1. Influence of tacticity and molecular weight on crystallization and melting behaviour. Polymer 34, 4075-4082. [CrossRef]

- Paukkeri, R., Lehtinen, A., 1993b. Thermal behaviour of polypropylene fractions: 2. The multiple melting peaks. Polymer 34, 4083-4088. [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, A., Rozanski, A., Galeski, A., 2013. Thermovision studies of plastic deformation and cavitation in polypropylene. Mech. Mater. 67, 104-118. [CrossRef]

- Perepechko, I.I., 1977. Svoistva polimerov pri nizkih temperaturah. Khimiya, Moskva.

- Peterlin, A., 1971. Molecular model of drawing polyethylene and polypropylene. J. Mater. Sci. 6, 490-508. [CrossRef]

- Peterson, J.M., 1966. Thermal Initiation of Screw Dislocations in Polymer Crystal Platelets. Journal of Applied Physics 37, 4047-4050. [CrossRef]

- Peterson, J.M., 1968. Peierls Stress for Screw Dislocations in Polyethylene. Journal of Applied Physics 39, 4920-4928. [CrossRef]

- Pluta, M., Kryszewski, M., 1987. Studies of alpha-relaxation process in spherulitic and non-spherulitic samples of isotactic polypropylene with different molecular ordering. Acta Polym. 38, 42-52. [CrossRef]

- Qian, C., Zhao, Y., Wang, Z., Liu, L., Wang, D., 2021. Probing the difference of crystalline modifications and structural disorder of isotactic polypropylene via high-resolution FTIR spectroscopy. Polymer 224, 123722. [CrossRef]

- Qian, S., Igarashi, T., Nitta, K.-h., 2011. Thermal degradation behavior of polypropylene in the melt state: molecular weight distribution changes and chain scission mechanism. Polym. Bull. 67, 1661-1670. [CrossRef]

- Quijada-Garrido, I., Barrales-Rienda, J.M., Pereña, J.M., Frutos, G., 1997. Dynamic mechanical and dielectric behavior of erucamide (13-Cis-Docosenamide), isotactic poly(propylene), and their blends. J. Polym. Sci., Part B: Polym. Phys. 35, 1473-1482. [CrossRef]

- Quynn, R.G., Riley, J.L., Young, D.A., Noether, H.D., 1959. Density, crystallinity, and heptane insolubility in isotactic polypropylene. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2, 166-173. [CrossRef]

- Raimo, M., Silvestre, C., 2009. Topographic Analysis of Isotactic Polypropylene Spherulites by Atomic Force Microscopy. Journal of Scanning Probe Microscopy 4, 45-47. [CrossRef]

- Read, B.E., 1990. Mechanical relaxation in isotactic polypropylene. Polymer 30, 1439-1445. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.R., Tashiro, K., Sakurai, T., Yamaguchi, N., Sasaki, S., Masunaga, H., Takata, M., 2009. Isothermal Crystallization Behavior of Isotactic Polypropylene H/D Blends as Viewed from Time-Resolved FTIR and Synchrotron SAXS/WAXD Measurements. Macromolecules 42, 4191-4199. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Arnold, J., Zhang, A., Cheng, S.Z.D., Lovinger, A.J., Hsieh, E.T., Chu, P., Johnson, T.W., Honnell, K.G., Geerts, R.G., Palackal, S.J., Hawley, G.R., Welch, M.B., 1994. Crystallization, melting and morphology of syndiotactic polypropylene fractions: 1. Thermodynamic properties, overall crystallization and melting. Polymer 35, 1884-1895. [CrossRef]

- Ronkay, F., Molnár, B., Nagy, D., Szarka, G., Iván, B., Kristály, F., Mertinger, V., Bocz, K., 2020. Melting temperature versus crystallinity: new way for identification and analysis of multiple endotherms of poly(ethylene terephthalate). J. Polym. Res. 27, 372. [CrossRef]

- Rungswang, W., Jarumaneeroj, C., Patthamasang, S., Phiriyawirut, P., Jirasukho, P., Soontaranon, S., Rugmai, S., Hsiao, B.S., 2019. Influences of tacticity and molecular weight on crystallization kinetic and crystal morphology under isothermal crystallization: Evidence of tapering in lamellar width. Polymer 172, 41-51. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, A.J., Stanford, J.L., Bras, W., Nye, T.M.W., 1997. A synchrotron X-ray study of melting and recrystallization in isotactic polypropylene. Polymer 38, 759-768. [CrossRef]

- Sakai, A., Tanaka, K., Fujii, Y., Nagamura, T., Kajiyama, T., 2005. Structure and thermal molecular motion at surface of semi-crystalline isotactic polypropylene films. Polymer 46, 429-437. [CrossRef]

- Schawe, J.E.K., 2017. Mobile amorphous, rigid amorphous and crystalline fractions in isotactic polypropylene during fast cooling. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 127, 931-937. [CrossRef]

- Schönherr, H., Snétivy, D., Vansco, G.J., 1993. A nanoscopic view at the spherulitic morphology of isotactic polypropylene by atomic force microscopy. Polym. Bull. 30, 567-574. [CrossRef]

- Scoti, M., De Stefano, F., Di Girolamo, R., Malafronte, A., Talarico, G., De Rosa, C., 2023. Crystallization Behavior and Properties of Propylene/4-Methyl-1-pentene Copolymers from a Metallocene Catalyst. Macromolecules 56, 1446-1460. [CrossRef]

- Séguéla, R., 2002. Dislocation approach to the plastic deformation of semicrystalline polymers: Kinetic aspects for polyethylene and polypropylene. J. Polym. Sci., Part B: Polym. Phys. 40, 593-601. [CrossRef]

- Seguela, R., Staniek, E., Escaig, B., Fillon, B., 1999. Plastic deformation of polypropylene in relation to crystalline structure. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 71, 1873-1885. [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y., Zhao, J., Li, J., Wu, Z., Jiang, S., 2014. Investigations in annealing effects on structure and properties of β-isotactic polypropylene with X-ray synchrotron experiments. Colloid. Polym. Sci. 292, 3205-3221. [CrossRef]

- Sharaf, M.A., Kloczkowski, A., 2024. Evolution of the Deformation- and Flow-Induced Crystallization and Characterization of the Microstructure of a Single Spherulite, Lamella, and Chain of Isotactic Polypropylene. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 225, 2300203. [CrossRef]

- Shirinbayan, M., Nouira, S., Imaddahen, M.-A., Fitoussi, J., 2024. Microstructure-sensitive investigation on the plastic deformation and damage initiation of fiber-reinforced polypropylene composite. Composites Part B: Engineering 286, 111790. [CrossRef]

- Sigalas, N.I., Van Kraaij, S.A.T., Lyulin, A.V., 2023. Effect of Temperature on Flow-Induced Crystallization of Isotactic Polypropylene: A Molecular-Dynamics Study. Macromolecules 56, 8417-8427. [CrossRef]

- Stachurski, Z.H., Macnicol, J., 1998. The geometry of spherulite boundaries. Polymer 39, 5717-5724. [CrossRef]

- Starkweather, H.W., Avakian, P., Matheson, R.R., Fontanella, J.J., Wintersgill, M.C., 1992. Ultralow temperature dielectric relaxations in polyolefins. Macromolecules 25, 6871-6875. [CrossRef]

- Stojanović, Z., Kačarević-Popović, Z., Galović, S., Miličević, D., Suljovrujić, E., 2005. Crystallinity changes and melting behavior of the uniaxially oriented iPP exposed to high doses of gamma radiation. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 87, 279-286. [CrossRef]

- Stupp, S.I., Supan, T.J., Belton, D.J., 1979. Ice-water quenching technique for polypropylene. Orthotics and Prosthet. 33, 16-21.

- Suljovrujic, E., 2000. Radiation modification of the physical properties of polyolefins. University of Belgrade, Belgrade.

- Suljovrujic, E., 2002. Dielectric studies of molecular β-relaxation in low density polyethylene: the influence of drawing and ionizing radiation. Polymer 43, 5969-5978. [CrossRef]

- Suljovrujic, E., 2005. Some aspects of structural electrophysics of irradiated polyethylenes. Polymer 46, 6353-6359. [CrossRef]

- Suljovrujic, E., 2009a. Gel production, oxidative degradation and dielectric properties of isotactic polypropylene irradiated under various atmospheres. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 94, 521-526. [CrossRef]

- Suljovrujic, E., 2009b. The influence of molecular orientation on the crosslinking/oxidative behaviour of iPP exposed to gamma radiation. Eur. Polym. J. 45, 2068-2078. [CrossRef]

- Suljovrujic, E., 2012. Complete relaxation map of polypropylene: radiation-induced modification as dielectric probe. Polym. Bull. 68, 2033-2047. [CrossRef]

- Suljovrujic, E., Kostoski, D., Kacarevic-Popovic, Z., Dojcilovic, J., 1999. Effect of gamma irradiation on the dielectric relaxation of uniaxially oriented low density polyethylene. Polym. Int. 48, 1193-1196.

- Suljovrujic, E., Kostoski D, Dojcilovic J., 2001. Charge trapping in gamma irradiated low-density polyethylene. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 74, 167-170. [CrossRef]

- Suljovrujic, E., Micic, M., Milicevic, D., 2013. Structural Changes and Dielectric Relaxation Behavior of Uniaxially Oriented High Density Polyethylene. Journal of Engineered Fibers and Fabrics 8, 155892501300800316. [CrossRef]

- Suljovrujic, E., Milicevic, D., Stolic, A., Dudic, D., Vasalic, D., Dzunuzovic, E., Stamboliev, G., 2024. Thermal, mechanical, and dielectric properties of radiation sterilized mesomorphic PP: Comparison between gamma and electron beam irradiation modalities. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 229, 110940. [CrossRef]

- Suljovrujic, E., Stojanovic, Z., Dudic, D., Milicevic, D., 2021. Radiation, thermo-oxidative and storage induced changes in microstructure, crystallinity and dielectric properties of (un)oriented isotactic polypropylene. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 188, 109564. [CrossRef]

- Suljovrujic, E., Trifunovic, S., Milicevic, D., 2010. The influence of gamma radiation on the dielectric relaxation behaviour of isotactic polypropylene. The α relaxation. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 95, 164-171. [CrossRef]

- Tadokoro, H., Kobayashi, M., Ukita, M., Yasufuku, K., Murahashi, S., Torii, T., 1965. Normal Vibrations of the Polymer Molecules of Helical Conformation. V. Isotactic Polypropylene and Its Deuteroderivatives. The Journal of Chemical Physics 42, 1432-1449. [CrossRef]

- Tangirala, R., Baer, E., Hiltner, A., Weder, C., 2004. Photopatternable reflective films produced by nanolayer extrusion. Adv. Funct. Mater. 14, 595-604. [CrossRef]

- Tarani, E., Arvanitidis, I., Christofilos, D., Bikiaris, D.N., Chrissafis, K., Vourlias, G., 2023. Calculation of the degree of crystallinity of HDPE/GNPs nanocomposites by using various experimental techniques: a comparative study. J. Mater. Sci. 58, 1621-1639. [CrossRef]

- Tencé-Girault, S., Lebreton, S., Bunau, O., Dang, P., Bargain, F., 2019. Simultaneous SAXS-WAXS Experiments on Semi-Crystalline Polymers: Example of PA11 and Its Brill Transition. Crystals 9, 271. [CrossRef]

- Teodorescu, G.M., Vuluga, Z., Ion, R.M., Fistoș, T., Ioniță, A., Slămnoiu-Teodorescu, S., Paceagiu, J., Nicolae, C.A., Gabor, A.R., Ghiurea, M., 2024. The Effect of Thermoplastic Elastomer and Fly Ash on the Properties of Polypropylene Composites with Long Glass Fibers. Polymers 16, 1238. [CrossRef]

- Tiemblo, P., Gomez-Elvira, J.M., García Beltrán, S., Matisova-Rychla, L., Rychly, J., 2002. Melting and α relaxation effects on the kinetics of polypropylene thermooxidation in the range 80-170°C. Macromolecules 35, 5922-5926. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, D., 2001. Practical Guide to Polypropylene. Rapra Publishing, Shrewsbury, United Kingdom.

- Umemura, T., Suzuki T, Kashiwazaki T., 1982. Impurity Effect of the Dielectric Properties of Isotactic Polypropylene. IEEE transactions on electrical insulation EI-17, 300-305.

- van der Meer, D.W., 2003. Structure-Property Relationships in Isotactic Polypropylene. Twente University.

- Vittoria, V., Perullo, A., 1986. Effect of quenching temperature on the structure of isotactic polypropylene films. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part B 25, 267-281. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Bao, Z., Ding, S., Jia, J., Dai, Z., Li, Y., Shen, S., Chu, S., Yin, Y., Li, X., 2024. γ-Ray Irradiation Significantly Enhances Capacitive Energy Storage Performance of Polymer Dielectric Films. Adv. Mater., 2308597. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Jiang, Z., Fu, L., Lu, Y., Men, Y., 2014. Lamellar Thickness and Stretching Temperature Dependency of Cavitation in Semicrystalline Polymers. PLoS One 9, e97234. [CrossRef]

- Weeks, J.J., 1963. Melting Temperature and Change of Lamellar Thickness with Time for Bulk Polyethylene. Journal of research of the National Bureau of Standards. Section A, Physics and chemistry 67a, 441-451. [CrossRef]

- Wunderlich, B., 1990. Thermal Analysis. Academic Press, Inc.

- Yamada, K., Matsumoto, S., Tagashira, K., Hikosaka, M., 1998. Isotacticity dependence of spherulitic morphology of isotactic polypropylene. Polymer 39, 5327-5333. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-G., Zhang, L.-Q., Chen, C., Cui, J., Zeng, X.-b., Liu, L., Liu, F., Ungar, G., 2023. 3D Morphology of Different Crystal Forms in β-Nucleated and Fiber-Sheared Polypropylene: α-Teardrops, α-Teeth, and β-Fans. Macromolecules 56, 5502-5511. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C., Dai, X.-Y., Xing, Z.-L., Guo, S.-W., Li, F., Chen, X., Zhou, J.-J., Li, L., 2022. Investigation on the Structure and Performance of Polypropylene Sheets and Bi-axially Oriented Polypropylene Films for Capacitors. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 40, 1688-1696. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-T., Hou, S., Li, D.-L., Cao, Y.-J., Zhan, Y.-P., Jia, L., Fu, M.-l., Huang, H.-D., 2024. Hierarchical Structural Evolution, Electrical and Mechanical Performance of Polypropylene Containing Intrinsic Elastomers under Stretching and Annealing for Cable Insulation Applications. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 63, 11982-11991. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.-J., Liu, J.-G., Yan, S.-K., Dong, J.-Y., Li, L., Chan, C.-M., Schultz, J.M., 2005. Atomic force microscopy study of the lamellar growth of isotactic polypropylene. Polymer 46, 4077-4087. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z., Ma, L., Zhen, W., Sun, X., Ren, Z., Li, H., Yan, S., 2017. An abnormal melting behavior of isotactic polypropylene spherulites grown at low temperatures. Polymer 111, 183-191. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z., Zhou, Q., Ren, Z., Sun, X., Li, H., Li, H., Yan, S., 2015. The αβ-iPP growth transformation of commercial-grade iPP during non-isothermal crystallization. CrystEngComm 17. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X., Yan, D., Fang, Y., 2001. In Situ FTIR Spectroscopic Study of the Conformational Change of Isotactic Polypropylene during the Crystallization Process. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 105, 12461-12463. [CrossRef]

- Zhuravlev, S.P., Zhuravleva NM., Polonskij Yu.A., 2002. Deformation characteristics of polypropylene film and thermal stability of capacitor insulation made on the base of polypropylene film. Elektrotekhnika 11, 36-40.

- Zia, Q., Androsch, R., Radusch, H.-J., Piccarolo, S., 2006. Morphology, reorganization and stability of mesomorphic nanocrystals in isotactic polypropylene. Polymer 47, 8163-8172. [CrossRef]

- Zia, Q., Mileva, D., Androsch, R., 2008. Rigid Amorphous Fraction in Isotactic Polypropylene. Macromolecules 41, 8095-8102. [CrossRef]

- Zia, Q., Radusch, H.-J., Androsch, R., 2009. Deformation behavior of isotactic polypropylene crystallized via a mesophase. Polym. Bull. 63, 755-771. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, F., Keum, J.K., Chen, X., Hsiao, B.S., Chen, H., Lai, S.-Y., Wevers, R., Li, J., 2007. The role of interlamellar chain entanglement in deformation-induced structure changes during uniaxial stretching of isotactic polypropylene. Polymer 48, 6867-6880. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).