Submitted:

09 May 2025

Posted:

12 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Motivation

-

Mesh-free nature: Mesh-free nature: AI-driven methods like Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) and Deep Galerkin Methods (DGM) for solving nonlinear PDEs operate without the need for a predefined grid or mesh. This is a significant departure from traditional numerical methods such as finite element methods (FEM), finite difference methods (FDM), and finite volume methods (FVM), which rely on discretizing the computational domain. Instead:(1) Point-Based Learning: These methods evaluate the solution at scattered points across the domain, which can be sampled randomly or strategically.(2) Neural Representation: The solution u(x,t) is represented as a continuous function, parameterized by the weights of a neural network. For example: PINNs approximate u(x,t) directly by minimizing the residuals at the sampled points. Points do not need to follow any specific spatial organization (e.g., grid).

- High-dimensional scalability: AI-driven methods can handle problems with a large number of spatial, temporal, or parameter dimensions without significantly increasing computational complexity. Traditional numerical approaches, like finite element methods (FEM) or finite difference methods (FDM), struggle with high-dimensional problems due to the curse of dimensionality, whereas AI methods, particularly neural network-based approaches, excel in this regard.

- Learning capabilities: AI-driven approaches, particularly neural network-based models, combine data-driven and physics-informed strategies. This allows them to handle noisy data or unknown parameters, making them well-suited for solving nonlinear PDEs. These capabilities enable them to generalize across complex domains, learn representations of solutions efficiently, and adapt to variations in physical systems.

2. AI Techniques for Nonlinear PDEs

2.1. Deep Learning Models for Nonlinear PDEs

2.1.1. Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs)

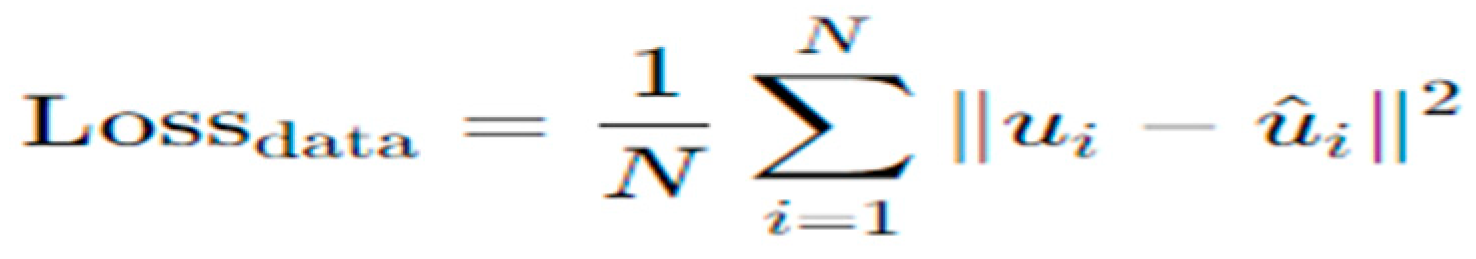

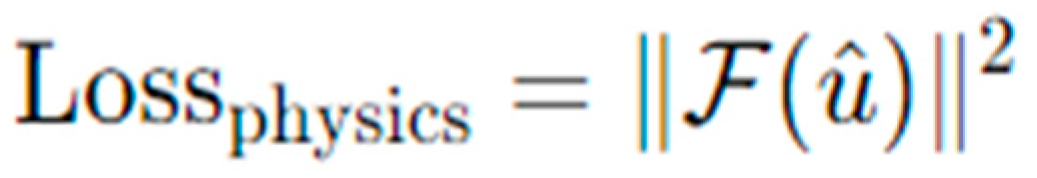

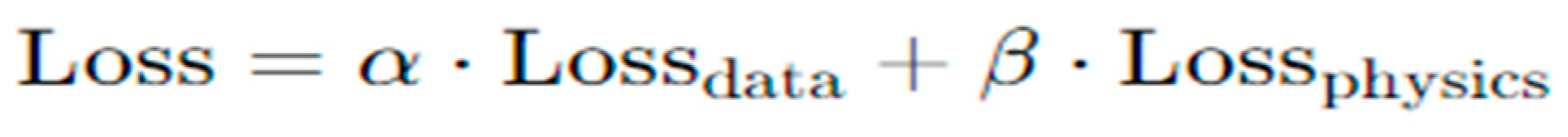

- Physics-Based Loss Function: Instead of relying solely on data, PINNs directly encode the differential equation into the loss function, ensuring that the model’s predictions adhere to the governing physical laws.

- Example: For solving fluid dynamics problems (e.g., Navier-Stokes equations), PINNs use both boundary/initial conditions and the PDE residual in the loss function to enforce physical constraints, where PINN Loss Function is:

- No need for labeled data.

- Solves forward and inverse problems.

2.1.2. Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs)

- Nonlinear Mapping: ANNs can approximate highly nonlinear functions due to their layered structure, where each layer transforms the input data nonlinearly.

- Approach: The general approach involves using neural networks to represent the unknown solution u(x,t) of a nonlinear PDE. The network learns to satisfy the PDE by minimizing the residual of the equation during training.

- Example: For a nonlinear heat equation:

2.1.3. Deep Galerkin Method (DGM)

2.1.4. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

- CNNs are particularly useful in solving PDEs that involve image-based data or spatiotemporal dynamics. These networks can capture local features and spatial patterns efficiently. Zhu et al [7] discussed using CNNs for modeling high-dimensional, spatiotemporal PDEs while enforcing physical constraints, making them ideal for image-based data. Long [8] introduced PDE-Net, which uses CNNs to learn differential operators and approximate solutions to PDEs, showcasing the suitability of CNNs for spatiotemporal dynamics. CNNs are widely used in fluid dynamics, image-based simulation problems, and tasks where the solution exhibits local spatial correlations. They can be used to approximate solution fields directly from data, such as predicting velocity or temperature fields. For example: Solving a convection-diffusion equation using CNNs:

2.2. Neural Operators for PDEs

2.2.1. Fourier Neural Operators (FNOs)

2.2.2. DeepONet (Deep Operator Network)

- ✓

- Encodes the input function f into a low-dimensional representation.

- ✓

- Input: Discretized or sampled points of f(x).

- ✓

- Output: Latent features representing the input function.

- ✓

- Encodes the evaluation points x into another feature space.

- ✓

- Input: Coordinates where the solution u(x) is to be computed.

- ✓

- Output: Latent features representing the evaluation points.

- ✓

- Operator Learning: Directly learns a mapping , where f is an input function (e.g., boundary conditions, initial conditions, or source terms), and u(x) is the solution.

- ✓

- Flexibility: Applicable to linear and nonlinear PDEs, and handles parametric PDEs with variable coefficients or source terms.

- ✓

- Efficiency: Once trained, DeepONet provides real-time solutions for any valid input function fff, bypassing traditional iterative solvers.

- ✓

- Scalability: Applied to high-dimensional PDEs or systems of PDEs.

2.3. Reinforcement Learning for PDEs

- Approach: In this setting, the agent explores possible solutions by interacting with the environment (the PDE), receiving feedback (the objective function), and adjusting its strategy over time. For example, Han et al [14] demonstrated how RL techniques can solve stochastic control problems, which often involve nonlinear PDEs, by approximating value functions using deep learning methods. Rabault et al [15] applied deep reinforcement learning to optimal control problems in fluid dynamics, showcasing its capability to handle nonlinear PDEs governing such systems. Bucci et al [16] explored how RL methods can be adapted for the control of systems described by PDEs, particularly nonlinear dynamics, by framing the control as an optimization problem.

- Applications: Used in control problems such as inverse design of systems governed by PDEs, where the goal is to optimize parameters subject to physical constraints.

- Example: Solving a PDE in a control context, such as optimizing the shape of a membrane subject to dynamic forces.

2.4. Evolutionary Algorithms and Genetic Programming

- Approach: GP evolves mathematical expressions or programs over generations, selecting those that best satisfy the PDE’s conditions. For example, Jin et al [84] reviewed multi-objective optimization techniques, including evolutionary approaches, and discusses their application to discovering and solving PDEs in complex parameter landscapes. Schmid et al [85] introduced an approach using genetic programming to discover symbolic representations of governing equations, including PDEs, from data. Bongard et al [86] demonstrated how genetic programming can uncover the structure of nonlinear dynamical systems, which often involve PDEs, through evolutionary exploration. Deb et al [87] discussed how genetic algorithms can optimize mesh structures and discretization strategies, providing insights for numerical solvers of PDEs.

- Applications: Discovering new, unknown forms of nonlinear PDEs or solving highly complex problems where traditional methods may struggle.

2.5. Hybrid AI-Numerical Methods

- AI techniques such as deep learning are used to extract important features or optimize initial guesses for numerical solvers. And numerical solvers operate on a reduced basis, enhancing efficiency.

- For data-driven correction, we use numerical methods to solve a coarse version of the PDE, and AI models learn the residual errors and correct the solution iteratively. For example, Raissi et al. [88] demonstrated how AI models, such as neural networks, can be integrated with traditional solvers to approximate fine-scale features by learning residuals. Bar-Sinai et al [89] illustrated how AI can learn corrections to coarse-grid discretizations for PDEs, blending data-driven methods with traditional numerical solvers. Geneva et al. [903] introduced a framework where AI models learn the discrepancy between numerical solutions and true solutions, iteratively refining the accuracy. Kashinath et al. [91] explored hybrid approaches where traditional solvers provide a base solution and AI models learn residuals to enhance the accuracy, especially for real-time applications. Rolfo et al. [270] highlighted the integration of machine learning techniques with numerical methods to solve PDEs more efficiently.

- Applications: In multi-physics problems or where traditional methods are computationally expensive, AI can help reduce the computational burden or enhance accuracy.

2.6. Transfer Learning for Nonlinear PDEs

2.7. Supervised Learning for PDE Solutions

2.8. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

3. AI Methods for Solving Exact Analytical Solutions of Nonlinear PDEs

3.1. Symbolic Computation

3.2. Hirota Bilinear Methods

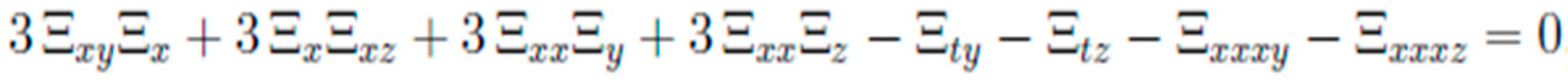

3.3. Bilinear Neural Network Methods

4. Challenges in AI-Driven Nonlinear PDE Solvers

4.1. Challenges

- (1).

- Computational Complexity

- (2).

- Generalization and Extrapolation

- (3).

- Data Dependency

- (4).

- Handling Stiffness and Nonlinearity

- (5).

- Loss Function Design and Balancing

- (6).

- Sampling Strategies

- (7).

- Scalability to Real-World Problems

- (8).

- Numerical Stability and Convergence

- (9).

- Interpretability

- (10).

- Integration with Existing Frameworks

- (11).

- Lack of Standardization: There is no standardized framework for AI-based PDE solvers, leading to variations in implementations and results. Thus developing unified benchmarks and evaluation metrics is essential for consistency.

- (12).

- Ethical and Practical Concerns

4.2. Strategies to Address Challenges

5. Conclusion and Future Directions

Acknowledgments

References

- M. Raissi, P.Perdikaris, & G. E.Karniadakis, Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. Journal of Computational Physics, 2019, 378, 686–707. [CrossRef]

- I. E.Lagaris, A.Likas, & D. I.Fotiadis, Artificial neural networks for solving ordinary and partial differential equations. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks, 1998, 9(5), 987-1000. [CrossRef]

- J. Sirignano, & K. Spiliopoulos, DGM: A deep learning algorithm for solving PDEs. Journal of Computational Physics, 2018, 375, 1339–1364.

- Han J, Jentzen A, E W. Solving high-dimensional partial differential equations using deep learning, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2018, 115(34), 8505-8510. [CrossRef]

- Beck, C., E, W., & Jentzen, A., Machine learning approximation algorithms for high-dimensional fully nonlinear partial differential equations and second-order backward stochastic differential equations. Journal of Nonlinear Science, 2019, 29(4), 1563-1619. [CrossRef]

- Nian, X., & Zhang, Y., A review on reinforcement learning for nonlinear PDEs. Journal of Scientific Computing, 2020, 85, 28.

- Zhu, Y., Zabaras, N., Koutsourelakis, P. S., & Perdikaris, P. (2019). Physics-constrained deep learning for high-dimensional surrogate modeling. Journal of Computational Physics, 394, 56–81. [CrossRef]

- Long, Z., Lu, Y., Ma, X., & Dong, B., PDE-Net: Learning PDEs from data[C], Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), 2018. https://proceedings.mlr.press/v80/long18a.html.

- Li, Z., Kovachki, N. B., Azizzadenesheli, K., Liu, B., Bhattacharya, K., Stuart, A., & Anandkumar, A. (2021). Fourier Neural Operator for Parametric Partial Differential Equations. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR). https://arxiv.org/abs/2010.08895.

- Kovachki, N. B., Li, Z., Liu, B., Azizzadenesheli, K., Bhattacharya, K., Stuart, A. M., & Anandkumar, A. (2023). Neural operator learning for PDEs. Nature Machine Intelligence, 5, 356–365.

- Pang G, D’Elia M, Parks M, et al. nPINNs: Nonlocal physics-informed neural networks for a parametrized nonlocal universal Laplacian operator. Algorithms and applications, Journal of Computational Physics, 2020, 422: 109760. [CrossRef]

- Lu, L., Jin, P., Pang, G., Zhang, Z., & Karniadakis, G. E., Learning nonlinear operators via DeepONet based on the universal approximation theorem of operators. Nature Communications, 2021,12, Article 6138.

- Wang, S., Yu, X., & Perdikaris, P.. Learning the solution operator of parametric partial differential equations with physics-informed DeepONets. Science Advances, 2021, 7(40), eabi8605. [CrossRef]

- Han, J., & E, W., Deep learning approximation for stochastic control problems. Deep Learning and Applications in Stochastic Control and PDEs Workshop, NIPS. 2016. https://arxiv.org/abs/1611.07422.

- Rabault, J., Kuchta, M., Jensen, A., Reglade, U., & Cerardi, N., Artificial neural networks trained through deep reinforcement learning discover control strategies for active flow control. Nature Machine Intelligence, 2019, 1, 317–324.

- Bucci, M., & Kutz, J. N.. Control of partial differential equations using reinforcement learning. Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science, 2021, 31(3), 033148.

- Meng X, Li Z, Zhang D, et al. PPINN: Parareal physics-informed neural network for time- dependent PDEs [J]. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 2020, 370: 113250. [CrossRef]

- Jagtap A D, Shin Y, Kawaguchi K, et al. Deep Kronecker neural networks: A general framework for neural networks with adaptive activation functions [J]. Neurocomputing, 2022, 468: 165–180. [CrossRef]

- Jagtap A D, Kawaguchi K, Em Karniadakis G. Locally adaptive activation functions with slop recovery for deep and physics-informed neural networks [J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society A, 2020, 476 (2239): 20200334. [CrossRef]

- Jagtap A D, Kawaguchi K, Karniadakis G E. Adaptive activation functions accelerate convergence in deep and physics-informed neural networks [J]. Journal of Computational Physics, 2020, 404: 109136. [CrossRef]

- Lu L, Meng X, Mao Z, et al. DeepXDE: A deep learning library for solving differential equations [J]. SIAM Review, 2021, 63 (1): 208–228. [CrossRef]

- Haghighat E, Juanes R. SciANN: A Keras/TensorFlow wrapper for scientific computations and physics-informed deep learning using artificial neural networks [J]. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 2021, 373: 113552. [CrossRef]

- Zubov K, McCarthy Z, Ma Y, et al. NeuralPDE: Automating Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) with Error Approximations [J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.09443, 2021.

- Jin X, Cai S, Li H, et al. NSFnets (Navier-Stokes flow nets): Physics-informed neural net works for the incompressible Navier-Stokes equations [J]. Journal of Computational Physics, 2021, 426: 109951. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0021999120307257. [CrossRef]

- Hennigh O, Narasimhan S, Nabian M A, et al. NVIDIA SimNet™: An AI-Accelerated Multi-Physics Simulation Framework [C] // Paszynski M, Kranzlmüller D, Krzhizhanovskaya V V, et al. In Computational Science – ICCS 2021, Cham, 2021: 447–461.

- Araz J Y, Criado J C, Spannwosky M. Elvet – a neural network-based differential equation and variational problem solver. 2021.

- McClenny L D, Haile M A, Braga-Neto U M. TensorDiffEq: Scalable Multi-GPU Forward and Inverse Solvers for Physics Informed Neural Networks [J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.16034, 2021.

- Koryagin A, Khudorozhkov R, Tsimfer S. PyDEns: a Python Framework for Solving Differential Equations with Neural Networks [J]. CoRR, 2019, abs/1909.11544. http://arxiv.org/ abs/1909.11544.

- Kidger P, Chen R T Q, Lyons T. “Hey, that’s not an ODE”: Faster ODE Adjoints via Seminorms [J]. International Conference on Machine Learning, 2021.

- Rackauckas C, Ma Y, Martensen J, et al. Universal Differential Equations for Scientific Machine Learning [J]. CoRR, 2020, abs/2001.04385. https://arxiv.org/abs/2001.04385.

- Xiang Z, Peng W, Zheng X, et al. Self-adaptive loss balanced Physics-informed neural networks for the incompressible Navier-Stokes equations[J]. Acta Mechanica Sinica, 2021,37(1):47–52.

- Peng W, Zhang J, Zhou W, et al. IDRLnet: A Physics-Informed Neural Network Library, eprint arXiv:2107.04320, 2021.

- Wang L, Yan Z. Data-driven rogue waves and parameter discovery in the defocusing nonlin ear Schrödinger equation with a potential using the PINN deep learning [J]. Physics Letters A, 2021, 404: 127408. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0375960121002723.

- Xu J, Pradhan A, Duraisamy K. Conditionally Parameterized, Discretization-Aware Neural Networks for Mesh-Based Modeling of Physical Systems. arXiv:2012, 2109.09510.

- Krishnapriyan A S, Gholami A, Zhe S, et al. Characterizing possible failure modes in physics informed neural networks [J]. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2021, 34.

- Penwarden M, Jagtap A D, Zhe S, et al. A unified scalable framework for causal sweeping strategies for Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) and their temporal decompositions [J]. Journal of Computational Physics, 2023: 112464. [CrossRef]

- Yang X, Zhou Z, Li L, et al. Collaborative robot dynamics with physical human–robot interaction and parameter identification with PINN [J]. Mechanism and Machine Theory, 2023, 189: 105439. [CrossRef]

- Tian S, Cao C, Li B. Data-driven nondegenerate bound-state solitons of multicomponent Bose-Einstein condensates via mix-training PINN [J]. Results in Physics, 2023, 52: 106842. [CrossRef]

- Saqlain S, Zhu W, Charalampidis E G, et al. Discovering governing equations in discrete systems using PINNs [J]. Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation, 2023: 107498. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Liu W, Yan X, et al. Adaptive transfer learning for PINN [J]. Journal of Computational Physics, 2023, 490: 112291. [CrossRef]

- Son H, Cho S W, Hwang H J. Enhanced physics-informed neural networks with Augmented Lagrangian relaxation method (AL-PINNs) [J]. Neurocomputing, 2023, 548: 126424. [CrossRef]

- Batuwatta-Gamage C P, Rathnayaka C, Karunasena H C, et al. A novel physics-informed neural networks approach (PINN-MT) to solve mass transfer in plant cells during drying [J]. Biosystems Engineering, 2023, 230: 219–241. [CrossRef]

- Meng Z, Qian Q, Xu M, et al. PINN-FORM: A new physics-informed neural network for reliability analysis with partial differential equation [J]. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 2023, 414: 116172. [CrossRef]

- Liu C, Wu H. cv-PINN: Efficient learning of variational physics-informed neural network with domain decomposition [J]. Extreme Mechanics Letters, 2023, 63: 102051.

- Pu J, Chen Y. Complex dynamics on the one-dimensional quantum droplets via time piecewise PINNs [J]. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena, 2023, 454: 133851. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y H, Xu Z, Qian C, et al. Solving free-surface problems for non-shallow water using boundary and initial conditions-free physics-informed neural network (bif-PINN) [J]. Journal of Computational Physics, 2023, 479: 112003.

- Penwarden M, Zhe S, Narayan A, et al. A metalearning approach for Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs): Application to parameterized PDEs [J]. Journal of Computational Physics, 2023, 477: 111912. [CrossRef]

- Guo Q, Zhao Y, Lu C, et al. High-dimensional inverse modeling of hydraulic tomography by physics informed neural network (HT-PINN) [J]. Journal of Hydrology, 2023, 616: 128828. [CrossRef]

- P Villarino J, Álvaro Leitao, García Rodríguez J. Boundary-safe PINNs extension: Application to non-linear parabolic PDEs in counterparty credit risk [J]. Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics, 2023, 425: 115041.

- He G, Zhao Y, Yan C. MFLP-PINN: A physics-informed neural network for multiaxial fatigue life prediction [J]. European Journal of Mechanics - A/Solids, 2023, 98: 104889. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Mao B, Che Y, et al. Physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) for 4D hemodynamics prediction: An investigation of optimal framework based on vascular morphology [J]. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 2023, 164: 107287. [CrossRef]

- Yin Y-H, Lü X. Dynamic analysis on optical pulses via modified PINNs: Soliton solutions, rogue waves and parameter discovery of the CQ-NLSE [J]. Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation, 2023, 126: 107441. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z-Y, Zhang H, Liu Y, et al. Generalized conditional symmetry enhanced physics-informed neural network and application to the forward and inverse problems of nonlinear diffusion equations [J]. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 2023, 168: 113169. [CrossRef]

- Peng W-Q, Pu J-C, Chen Y. PINN deep learning method for the Chen–Lee–Liu equation: Rogue wave on the periodic background [J]. Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation, 2022, 105: 106067.

- Wang R-Q, Ling L, Zeng D, et al. A deep learning improved numerical method for the simulation of rogue waves of nonlinear Schrödinger equation [J]. Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation, 2021, 101: 105896. [CrossRef]

- Zhu B-W, Fang Y, Liu W, et al. Predicting the dynamic process and model parameters of vector optical solitons under coupled higher-order effects via WL-tsPINN [J]. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 2022, 162: 112441. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Li B. Mix-training physics-informed neural networks for the rogue waves of nonlinear Schrödinger equation [J]. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 2022, 164: 112712. [CrossRef]

- Pu J-C, Chen Y. Data-driven vector localized waves and parameters discovery for Manakov system using deep learning approach [J]. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 2022, 160: 112182. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Wang L, Zhang P, et al. The nonlinear wave solutions and parameters discovery of the Lakshmanan-Porsezian-Daniel based on deep learning [J]. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 2022, 159: 112155. [CrossRef]

- Yuan L, Ni Y-Q, Deng X-Y, et al. A-PINN: Auxiliary physics informed neural networks for forward and inverse problems of nonlinear integro-differential equations [J]. Journal of Computational Physics, 2022, 462: 111260. [CrossRef]

- Gao H, Zahr M J, Wang J-X. Physics-informed graph neural Galerkin networks: A unified framework for solving PDE-governed forward and inverse problems [J]. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 2022, 390: 114502. [CrossRef]

- Yang L, Meng X, Karniadakis G E. B-PINNs: Bayesian physics-informed neural networks for forward and inverse PDE problems with noisy data [J]. Journal of Computational Physics, 2021, 425: 109913. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z Y, Zhang H, Zhang L S, et al. Enforcing continuous symmetries in physics- informed neural network for solving forward and inverse problems of partial differential equations [J]. Journal of Computational Physics, 2023, 492: 112415. [CrossRef]

- Wei Guo J, zhong Yao Y, Wang H, et al. Pre-training strategy for solving evolution equations based on physics-informed neural networks [J]. Journal of Computational Physics, 2023, 489: 112258.

- Long Guan W, han Yang K, sheng Chen Y, et al. A dimension-augmented physics-informed neural network (DaPINN) with high level accuracy and efficiency [J]. Journal of Computational Physics, 2023, 491: 112360.

- Luo, K., Liao, S., Guan, Z. et al. An enhanced hybrid adaptive physics-informed neural network for forward and inverse PDE problems. Appl Intell. , 2025,55, 255. [CrossRef]

- Li Wang X, kang Wu Z, jing Han W, et al. Deep learning data-driven multi-soliton dynamics and parameters discovery for the fifth-order Kaup–Kuperschmidt equation [J]. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena, 2023, 454: 133862.

- Ping Tang S, long Feng X, Wu W, et al. Physics-informed neural networks combined with polynomial interpolation to solve nonlinear partial differential equations [J]. Computers & Mathematics with Applications, 2023, 132: 48–62.

- Zhong M, bo Gong S, Tian S-F, et al. Data-driven rogue waves and parameters discovery in nearly integrable PT-symmetric Gross–Pitaevskii equations via PINNs deep learning [J]. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena, 2022, 439: 133430.

- Song J, Yan Z Y. Deep learning soliton dynamics and complex potentials recognition for 1D and 2D PT-symmetric saturable nonlinear Schrödinger equations [J]. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena, 2023, 448: 133729.

- Jian Zhou Z, Yan Z Y. Solving forward and inverse problems of the logarithmic nonlinear Schrödinger equation with PT-symmetric harmonic potential via deep learning [J]. Physics Letters A, 2021, 387: 127010.

- Wang L, Yan Z Y. Data-driven peakon and periodic peakon solutions and parameter discovery of some nonlinear dispersive equations via deep learning [J]. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena, 2021, 428: 133037.

- Lin S N, Chen Y. A two-stage physics-informed neural network method based on conserved quantities and applications in localized wave solutions [J]. Journal of Computational Physics, 2022, 457: 111053.

- Wu C X, Zhu M, Tan Q Y, et al. A comprehensive study of non-adaptive and residual-based adaptive sampling for physics-informed neural networks [J]. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 2023, 403: 115671.

- Qin S-M, Li M, Xu T, et al. A-WPINN algorithm for the data-driven vector-soliton solutions and parameter discovery of general coupled nonlinear equations [J]. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena, 2023, 443: 133562. [CrossRef]

- Lin S, Chen Y. Physics-informed neural network methods based on Miura transformations and discovery of new localized wave solutions [J]. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena, 2023, 445: 133629. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Duan J, Hu J, et al. Data-driven method to learn the most probable transition pathway and stochastic differential equation [J]. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena, 2023, 443: 133559. [CrossRef]

- Hao Y, Xie X, Zhao P, et al. Forecasting three-dimensional unsteady multi-phase flow fields in the coal-supercritical water fluidized bed reactor via graph neural networks [J]. Energy, 2023, 282: 128880. [CrossRef]

- Zhang P, Tan S, Hu X, et al. A double-phase field model for multiple failures in composites [J]. Composite Structures, 2022, 293: 115730. [CrossRef]

- Wu Z, Ye H, Zhang H, et al. Seq-SVF: An unsupervised data-driven method for automatically identifying hidden governing equations [J]. Computer Physics Communications, 2023, 292: 108887. [CrossRef]

- Peng J-Z, Aubry N, Li Y-B, et al. Physics-informed graph convolutional neural network for modeling geometry-adaptive steady-state natural convection [J]. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 2023, 216: 124593. [CrossRef]

- Li H-W-X, Lu L, Cao Q. Motion estimation and system identification of a moored buoy via physics informed neural network [J]. Applied Ocean Research, 2023, 138: 103677.

- Cui S, Wang Z. Numerical inverse scattering transform for the focusing and defocusing Kundu-Eckhaus equations [J]. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena, 2023, 454: 133838. [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y., & Sendhoff, B., Pareto-based multi-objective machine learning: An overview and case studies. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part C: Applications and Reviews, 2009, 38(3), 397-415.

- Schmidt, M., & Lipson, H., Distilling free-form natural laws from experimental data. Science, 2009, 324(5923), 81-85. [CrossRef]

- Bongard, J., & Lipson, H., Automated reverse engineering of nonlinear dynamical systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2007, 104(24), 9943-9948. [CrossRef]

- Deb, K., & Goyal, M., Optimizing engineering designs using a combined genetic search. Complex Systems, 1997, 9, 213-230.

- Raissi, M., Yazdani, A., & Karniadakis, G. E., Hidden fluid mechanics: Learning velocity and pressure fields from flow visualizations. Science, 2020, 367(6481), 1026-1030. [CrossRef]

- Bar-Sinai, Y., Hoyer, S., Hickey, J., & Brenner, M. P., Learning data-driven discretizations for partial differential equations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2019,116(31), 15344-15349. [CrossRef]

- Geneva, N., & Zabaras, N., Modeling the dynamics of PDE systems with physics-constrained deep auto-regressive networks. Journal of Computational Physics, 2020, 403, 109056. [CrossRef]

- Kashinath, K., Mustafa, M., Albert, A., et al. , Physics-informed machine learning for real-time PDE solutions. Proceedings of the Royal Society A, 2021, 477, 20210400.

- Gupta, S., & Jacob, R. A. (2021).Transfer learning in physics-informed neural networks for solving parametric PDEs. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 384, 113938. [CrossRef]

- Ruthotto, L., & Haber, E., Deep neural networks motivated by partial differential equations.Journal of Mathematical Imaging and Vision, 2020, 62, 352–364. [CrossRef]

- Jin, X., Chen, Y., & Li, Z. , Transfer learning for accelerated discovery of PDE solutions using neural networks. Scientific Reports, 2022, 12, Article 3267.

- Lusch S., Kutz J. N., Brunton S. L., Deep learning for universal linear embeddings of nonlinear dynamics, Nature Communications (2018).

- Bhattacharya, K., Hosseini, B., Kovachki, N., & Stuart, A. M., Model reduction and neural networks for parametric PDEs. The SMAI Journal of Computational Mathematics, 2021, 7, 121-157. [CrossRef]

- Xiaoxuan Zhang and Krishna Garikipati, Label-free learning of elliptic partial differential equation solvers with generalizability across boundary value problems, Computer methods in applied mechanics and engineering, 2023, 417, p.116214. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y., Zabaras, N., Koutsourelakis, P.-S., & Perdikaris, P., Physics-Constrained Deep Learning for High-Dimensional Surrogate Modeling and Uncertainty Quantification Without Labeled Data. Journal of computational physics, 2019-10, Vol.394, p.56-81. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L., Zhang, D., & Karniadakis, G. E., Physics-Informed Generative Adversarial Networks for Stochastic Differential Equations, SIAM journal on scientific computing, 2020-02, 42 (1). [CrossRef]

- Xie, X., Zheng, C., Li, X., & Xu, L. , Physics-informed generative adversarial networks for solving inverse problems of partial differential equations. Journal of Computational Physics, 2020, 416, 109560.

- Sun, L., Gao, H., Pan, S., & Wang, J.-X., Physics-constrained generative adversarial network for parametric fluid flow simulation. Theoretical and Applied Mechanics Letters, 2020, 10(3), 161-169.

- 2024; Yulong Lu, Wuzhe Xu , Generative Downscaling of PDE Solvers with Physics-Guided Diffusion Models, Journal of scientific computing, 2024, 101 (3), 71. [CrossRef]

- Mehdi Taghizadeh, Mohammad Amin Nabian, Negin Alemazkoor., Multi-Fidelity Physics-Informed Generative Adversarial Network for Solving Partial Differential Equations, Journal of computing and information science in engineering, 2024, 24 (11) 111003. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Lu ; Meng, Xuhui ; Mao, Zhiping ; Karniadakis, George Em, DeepXDE: A Deep Learning Library for Solving Differential Equations, SIAM review, 2021, 63 (1), p.208-228. [CrossRef]

- Hereman W, Nuseir A. Symbolic methods to construct exact solutions of nonlinear partial differential equations [J]. Mathematics and Computers in Simulation, 1997, 43 (1): 13–27. [CrossRef]

- Borg M, Badra N M, Ahmed H M, et al. Solitons behavior of Sasa-Satsuma equation in birefringent fibers with Kerr law nonlinearity using extended F-expansion method [J]. Ain Shams Engineering Journal, 2023: 102290. [CrossRef]

- Rabie W B, Ahmed H M. Cubic-quartic solitons perturbation with couplers in optical metamaterials having triple-power law nonlinearity using extended F-expansion method [J]. Optik, 2022, 262: 169255. [CrossRef]

- Yu J P, Ma W X, Sun S Y L, et al. N–fold Darboux transformation and conservation laws of the modified Volterra lattice [J]. Mod. Phys. Lett. B, 2018, 32: 1850409.

- Abdel Rady A, Osman E, Khalfallah M. The homogeneous balance method and its application to the Benjamin–Bona–Mahoney (BBM) equation [J]. Applied Mathematics and Computation, 2010, 217 (4): 1385–1390.

- Eslami M, Fathi vajargah B, Mirzazadeh M. Exact solutions of modified Zakharov–Kuznetsov equation by the homogeneous balance method [J]. Ain Shams Engineering Journal, 2014, 5 (1): 221–225. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen L T K. Modified homogeneous balance method: Applications and new solutions [J]. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 2015, 73: 148–155.

- Hirota R. The direct method in soliton theory [M]. Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Lü X, Lin F H, Qi F H. Analytical study on a two–dimensional Korteweg–de Vries model with bilinear representation, Bäcklund transformation and soliton solutions [J]. Appl. Math. Model., 2015, 39: 3221–3226.

- Chen S J, Ma W X, Lü X. Bäcklund transformation, exact solutions and interaction behaviour of the (3+1)–dimensional Hirota–Satsuma–Ito–like equation [J]. Commun Nonlinear Sci Numer Simulat, 2020, 83: 105135.

- Wazwaz A-M. The extended tanh method for new compact and noncompact solutions for the KP–BBM and the ZK–BBM equations [J]. Chaos, Solitons Fractals, 2008, 38 (5): 1505–1516.

- Hirota R. The direct method in soliton theory [M]. Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Yao R X, Li Y, Lou S Y. A new set and new relations of multiple soliton solutions of (2 + 1)- dimensional Sawada–Kotera equation [J]. Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation, 2021, 99: 105820.

- Zhang X E, Chen Y. Rogue wave and a pair of resonance stripe solitons to a reduced (3+1)- dimensional Jimbo–Miwa equation [J]. Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation, 2017, 52: 24–31.

- Wang H F, Zhang Y F. A kind of nonisospectral and isospectral integrable couplings and their Hamiltonian systems [J]. Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation, 2021, 99: 105822.

- Yao R X, Xu G Q, Li Z B. Conservation laws and soliton solutions for generalized seventh order KdV equation [J]. Communications in Theoretical Physics, 2004, 41 (4): 487–492.

- An H L, Feng D L, Zhu y j N v p d d, Hua Xing title= General MM-lump, high-order breather and localized interaction solutions to the 2+12+1-dimensional Sawada–Kotera equation.

- Li Y, Yao R X, Lou S Y. An extended Hirota bilinear method and new wave structures of (2+1)-dimensional Sawada–Kotera equation [J]. Applied Mathematics Letters, 2023, 145: 108760.

- Wang M, Zhang J, Li L. The decay mode solutions of the cylindrical/spherical nonlinear Schrödinger equation [J]. Applied Mathematics Letters, 2023, 145: 108744. [CrossRef]

- Zhang T T, Zhang L D. Dynamic behaviors of vector breather waves and higher-order rogue waves in the coupled Gerdjikov–Ivanov equation [J]. Applied Mathematics Letters, 2023, 143: 108691. [CrossRef]

- Zhao B, Huang D W, Guo B. L., Blow-up criterion of solutions of the horizontal viscous primitive equations with horizontal eddy diffusivity [J]. Applied Mathematics Letters, 2023, 145: 108743.

- Wang D S, Zhang H Q., Further improved F-expansion method and new exact solutions of Konopelchenko–Dubrovsky equation [J]. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 2005, 25 (3): 601–610.

- Xia T C, Lü Z S, Zhang H Q., Symbolic computation and new families of exact soliton-like solutions of Konopelchenko-Dubrovsky equations [J]. Chaos, Solitons and Fractals, 2004, 20 (3): 561-566.

- Zhang Z, Yang X Y, Li B, et al. Generation mechanism of high-order rogue waves via the improved long-wave limit method: NLS case [J]. Physics Letters A, 2022, 450: 128395. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Hao H Q, Guo R. Periodic solutions and Whitham modulation equations for the Lakshmanan–Porsezian–Daniel equation [J]. Physics Letters A, 2022, 450: 128369.

- Wu J J, Sun Y J, Li B. Degenerate lump chain solutions of (4+1)-dimensional Fokas equation [J]. Results in Physics, 2023, 45: 106243.

- Yao Y Q, Chen D Y, Zhang D J. Multisoliton solutions to a nonisospectral (2+1)- dimensional breaking soliton equation [J]. Physics Letters A, 2008, 372 (12): 2017–2025.

- Li Z Q, Tian S F, Yang J J, et al. Soliton resolution for the complex short pulse equation with weighted Sobolev initial data in space-time solitonic regions [J]. Journal of Differential Equations, 2022, 329: 31–88.

- Lv C, Liu Q P. Multiple higher-order pole solutions of modified complex short pulse equation [J]. Applied Mathematics Letters, 2023, 141: 108518.

- Tian K, Cui M Y, Liu Q P. A note on Bäcklund transformations for the Harry Dym equation [J]. Partial Differential Equations in Applied Mathematics, 2022, 5: 100352.

- Zang L M, Liu Q P. A super KdV equation of Kupershmidt: Bäcklund transformation, Lax pair and related discrete system [J]. Physics Letters A, 2022, 422: 127794.

- Ma W X. N-soliton solutions and the Hirota conditions in (2+1)-dimensions [J]. Opt Quant Electron, 2020, 52: 511.

- Ma W X. Generalized bilinear differential equations [J]. Stud. Nonlinear Sci., 2011, 2 (4): 140–144.

- Ma W X, Fan E G. Linear superposition principle applying to Hirota bilinear equations [J]. Comput. Math. Appl., 2011, 61: 950–959.

- Ma W X. Bilinear equations, Bell polynomials and linear superposition principle [J]. J. Phys. Conf. Ser., 2013, 411: 012021.

- Feng Y, Bilige S. Multiple rogue wave solutions of (2+1)-dimensional YTSF equation via Hirota bilinear method [J]. Waves in Random and Complex Media, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Wazwaz A M, Kaur L. Complex simplified Hirota’s forms and Lie symmetry analysis for multiple real and complex soliton solutions of the modified KdV-Sine-Gordon equation [J]. Nonlinear Dyn., 2019, 95: 2209–2215.

- Wazwaz A-M. The Hirota’s direct method and the tanh-coth method for multiple-soliton solutions of the Sawada-Kotera-Ito seventh-order equation. [J]. Appl. Math. Comput., 2008, 199 (1): 133–138.

- Wazwaz A-M. The Hirota’s bilinear method and the tanh-coth method for multiple-soliton solutions of the Sawada-Kotera-Kadomtsev-Petviashvili equation [J]. Appl. Math. Comput., 2008, 200 (1): 160–166.

- Osman M S, Lu D C, Khater M M A. A study of optical wave propagation in the nonautonomous Schrödinger–Hirota equation with power–law nonlinearity [J]. Results Phys., 2019, 13: 102157.

- Zhou Y, Manukure S, Ma W X. Lump and lump–soliton solutions to the Hirota–Satsuma–Ito equation [J]. Commun. Nonlinear Sci., 2019, 68: 56–62.

- Hua Y F, Guo B L, Ma W X, et al. Interaction behavior associated with a generalized (2+1)–dimensional Hirota bilinear equation for nonlinear waves [J]. Appl. Math. Modell., 2019, 74: 184–198.

- Liu J G, Osman M S, Zhu W H, et al. Different complex wave structures described by the Hirota equation with variable coefficients in inhomogeneous optical fibers [J]. Appl. Phys. B, 2019, 125:175. [CrossRef]

- Fang T, Wang Y H. Interaction solutions for a dimensionally reduced Hirota bilinear equation [J]. Comput. Math. Appl., 2018, 76: 1476–1485.

- Peng W-Q, Chen Y. N-double poles solutions for nonlocal Hirota equation with nonzero boundary conditions using Riemann–Hilbert method and PINN algorithm [J]. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena, 2022, 435: 133274.

- Wazwaz A M. Multiple complex soliton solutions for integrable negative-order KdV and integrable negative-order modified KdV equations [J]. Appl. Math. Lett., 2019, 88: 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Wazwaz A M. A two–mode modified KdV equation with multiple soliton solutions [J]. Appl. Math. Lett., 2019, 70: 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Wazwaz A M. Multiple–soliton solutions for extended (3+1)-dimensional Jimbo-Miwa equations [J]. Appl. Math. Lett., 2017, 64: 21–26.

- Wazwaz A M. Kadomtsev–Petviashvili hierarchy: N-soliton solutions and distinct dispersion relations [J]. Appl. Math. Lett., 2016, 52: 74–79.

- Wazwaz A M, El–Tantawy S A. New (3+1)-dimensional equations of Burgers type and Sharma-Tasso-Olver type: multiple–soliton solutions [J]. Nonlinear Dyn., 2017, 87 (4): 2457–2461.

- Osman M S. One–soliton shaping and inelastic collision between double solitons in the fifth-order variable-coefficient Sawada–Kotera equation [J]. Nonlinear Dyn., 2019, 96: 1491–1496. [CrossRef]

- Osman M S, Wazwaz A M. An efficient algorithm to construct multi-soliton rational solutions of the (2+ 1)-dimensional KdV equation with variable coefficients [J]. Appl. Math. Comput., 2018, 321: 282–289. [CrossRef]

- Lu D C, Seadawy A R, Ali A. Applications of exact traveling wave solutions of Modified Liouville and the Symmetric Regularized Long Wave equations via two new techniques [J]. Results in Physics, 2018, 9: 1403–1410.

- Liua J G, Tian Y, Hu J G. New non-traveling wave solutions for the (3+1)-dimensional Boiti-Leon-Manna-Pempinelli equation [J]. Appl. Math. Lett., 2018, 79: 162-168.

- Cui WY, Zha QL, The third and fourth order rogue wave solutions of the (2+1) dimensional generalized Camassa Holm Kadomtsev Petviashvili equation [J]. Practice and Understanding of Mathematics, 2019, 49 (5), 273-281.

- Lü Z S, Chen Y N. Construction of rogue wave and lump solutions for nonlinear evolution equations [J]. Eur. Phys. J. B, 2015, 88: 187.

- Yang J J, Tian S F, Peng W Q, et al. The lump, lump off and rouge wave solutions of a (3+1)–dimensional generalized shallow water wave equation [J]. Mod. Phys. Lett. B, 2019, 33: 1950190.

- Wu X Y, Tian B, Chai H P, et al. Rogue waves and lump solutions for a (3+1)–dimensional generalized B–type Kadomtsev Petviashvili equation in fluid mechanics [J]. Mod. Phys. Lett. B, 2017, 31 (22): 1750122.

- Du Y H, Yun Y S, Ma W X. Rational solutions to two Sawada Kotera-like equations [J]. Mod. Phys. Lett. B, 2019, 33: 1950108.

- Zhang Y, Dong H H, Zhang X E, et al. Rational solutions and lump solutions to the generalized (3+1)-dimensional Shallow Water-like equation [J]. Comput. Math. Appl., 2017, 73: 246–252.

- Sun Y L, Ma W X, Yu J P, et al. Exact solutions of the Rosenau-Hyman equation, coupled KdV system and Burgers-Huxley equation using modified transformed rational function method [J]. Mod. Phys. Lett. B, 2018, 33: 1850282.

- Feng R Y, Gao X S, Huang Z Y. Rational solutions of ordinary difference equations [J]. Journal of Symbolic Computation, 2008, 43: 746–763.

- Feng R Y, Gao X S. A polynomial time algorithm for finding rational general solutions of first order autonomous ODEs [J]. Journal of Symbolic Computation, 2006, 41: 739–762.

- Ma W X. Lump and interaction solutions to linear (4+1)-dimensional PDSE[J]. Acta Math. Sci., 2019, 39B (2): 498–508.

- Lü J Q, Bilige S D, Chaolu T. The study of lump solution and interaction phenomenon to (2+1)–dimensional generalized fifth–order KdV equation [J]. Nonlinear Dyn., 2018, 91: 1669–1676.

- Lü J Q, Bilige S D. Lump solutions of a (2+1)–dimensional bSK equation [J]. Nonlinear Dyn., 2017, 90: 2119–2124.

- Lü J Q, Bilige S D. The study of lump solution and interaction phenomenon to (2+1) – dimensional Potential Kadomstev – Petviashvili Equation [J]. Anal. Math. Phys., 2018. [CrossRef]

- Lü J Q, Bilige S D, Gao X Q. The study of lump solution and Interaction Phenomenon to (2+1)–dimensional Potential Kadomstev–Petviashvili Equation [J]. Int. J. Nonlinear Sci. Num. Sim., 2018, 20.

- Lü J Q, Bilige S D, Gao X Q, et al. Abundant lump solutions and interaction phenomena to the Kadomtsev–Petviashvili–Benjamin–Bona–Mahony equation [J]. J. Appl. Math. Phys., 2018, 6: 1733–1747.

- Gao X Q, Bilige S D, Lü J Q, et al. Abundant Lump solutions and interaction solutions of The (3+1)–dimensional KP equation [J]. Thermal Science, 2019, 22 (4): 287–294.

- Kaur L, Wazwaz A M. Lump, breather and solitary wave solutions to new reduced form of the generalized BKP equation [J]. Int. J. Numer. Method H., 2019, 29 (2): 569–579. [CrossRef]

- Liu W, Wazwaz A M, Zhang X X. High–order breathers, lumps, and semirational solutions to the (2+1)–dimensional Hirota–Satsuma–Ito equation [J]. Phys. Scr., 2019, 94: 075203.

- Wang H, Wang Y H, Ma W X, et al. Lump solutions of a new extended (2+1)–dimensional Boussinesq equation [J]. Mod. Phys. Lett. B, 2019, 33: 1850376.

- Ma W X, Qin Z Y, Lü X. Lump solutions to dimensionally reduced p–gKP and p–gBKP equations [J]. Nonlinear Dyn., 2016, 84: 923–931.

- Yu J, Ma W X, Chen S T. Lump solutions of a new generalized Kadomtsev-Petviashvili equation [J]. Mod. Phys. Lett. B, 2019, 33: 1950126.

- Manukure S, Zhou Y, Ma W X. Lump solutions to a (2+1)-dimensional extended KP equation [J]. Comput. Math. Appl., 2018, 75: 2414–2419.

- Lü X, Wang J P, Lin F H, et al. Lump dynamics of a generalized two-dimensional Boussinesq equation in shallow water [J]. Nonlinear Dyn., 2018, 91: 1249–1259.

- Gao L N, Zi Y Y, Yin Y H, et al. Bäcklund transformation, multiple wave solutions and lump solutions to a (3 + 1)-dimensional nonlinear evolution equation [J]. Nonlinear Dyn., 2017, 89: 2233–2240.

- Hu C C, Tian B, Yin H M, et al. Dark breather waves, dark lump waves and lump wave–soliton interactions for a (3+1)-dimensional generalized Kadomtsev-Petviashvili equation in a fluid [J]. Comput. Math. Appl., 2019, 78: 166–177.

- Wu X Y, Tian B, Chai H P, et al. Rogue waves and lump solutions for a (3+1)–dimensional generalized B–type Kadomtsev Petviashvili equation in fluid mechanics [J]. Mod. Phys. Lett. B, 2017, 31 (22): 1750122.

- Yang J Y, Ma W X. Lump solutions to the BKP equation by symbolic computation [J]. INT. J. MOD. PHYS. B, 2016, 30: 1640028.

- Chen F P, Chen W Q, Wang L, et al. Nonautonomous characteristics of lump solutions for a (2+1)-dimensional Korteweg-de Vries equation with variable coefficients [J]. Appl. Math. Lett., 2019, 96: 33–39.

- Li W T, Zhang Z, Yang X Y, et al. High-order breathers, lumps and hybrid solutions to the (2+1)-dimensional fifth-order KdV equation [J]. INT. J. MOD. PHYS. B, 2019, 33: 1950255.

- Manukure S, Zhou Y. A (2+1)–dimensional shallow water equation and its explicit lump solutions [J]. INT. J. MOD. PHYS. B, 2019, 33: 1950038. [CrossRef]

- Wang H, Tian S F, Zhang T T, et al. Lump wave and hybrid solutions of a generalized (3+1)-dimensional nonlinear wave equation in liquid with gas bubbles [J]. Front. Math. China, 2019, 14 (3): 631–643. [CrossRef]

- Liu J G. Lump–type solutions and interaction solutions for the (2+1)–dimensional generalized fifth–order KdV equation [J]. Appl. Math. Lett., 2018, 86: 36–41.

- Ma W X, Zhouy Y, Dougherty R. Lump–type solutions to nonlinear differential equations derived from generalized bilinear equations [J]. INT. J. MOD. PHYS. B, 2016, 30: 1640018.

- Liu J G. Lump-type solutions and interaction solutions for the (2+1)–dimensional asymmetrical Nizhnik-Novikov-Veselov equation [J]. Eur. Phys. J. Plus, 2019, 134: 56.

- Ma W X. Lump–Type Solutions to the (3+1)-Dimensional Jimbo-Miwa Equation [J]. Int. J. Sci. Num., 2017, 17: 355–359.

- Fang T, Gao C N, Wang H, et al. Lump–type solution, rogue wave, fusion and fission phenomena for the (2+1)-dimensional Caudrey-Dodd-Gibbon-Kotera-Sawada equation [J]. Modern Physics Letters B, 2019, 33: 1950198.

- Fang T, Wang H, Wang Y H, et al. High-Order Lump-Type Solutions and Their Interaction Solutions to a (3+1)-Dimensional Nonlinear Evolution Equation [J]. Commun. Theor. Phys., 2019, 71: 927–934. [CrossRef]

- Manafian J, Lakestani M. Lump-type solutions and interaction phenomenon to the bidirectional Sawada-Kotera equation [J]. Pramana, 2019, 92: 41. [CrossRef]

- Manafian J, Mohammadi-Ivatloo B, Abapour M. Lump-type solutions and interaction phenomenon to the (2+1)–dimensional Breaking Soliton equation [J]. Appl. Math. Comput., 2019, 356: 13–41. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y Q, Wen X Y. Fission and fusion interaction phenomena of mixed lump kink solutions for a generalized (3+1)-dimensional B-type Kadomtsev-Petviashvili equation [J]. Mod. Phys. Lett. B, 2018, 32: 1850161.

- Dong M J, Tian S F, Wang X B, et al. Lump-type solutions and interaction solutions in the (3+1)-dimensional potential Yu-Toda-Sasa-Fukuyama equation [J]. Anal. Math. Phys., 2018. [CrossRef]

- Zhang R F, Bilige S D, Bai Y X, et al. Interaction phenomenon to dimensionally reduced p–gBKP equation [J]. Mod. Phys. Lett. B, 2018, 32: 1850074.

- Lü J Q, Bilige S D. Diversity of interaction solutions to the (3+1)-dimensional Kadomtsev-Petviashvili-Boussinesq-like equation [J]. Mod. Phys. Lett. B, 2018, 32: 1850311.

- Liu W J, Zhang Y J, Wazwaz A M, et al. Analytic study on triple–S, triple–triangle structure interactions for solitons in inhomogeneous multi-mode fiber [J]. Appl. Math. Comput., 2019, 361: 325–331.

- Zhang J B, Ma W X. Mixed lump-kink solutions to the BKP equation [J]. Comput. Math. Appl., 2017, 74: 591–596.

- Chen J, Yu J P, Ma W X, et al. Interaction solutions of the first BKP equation [J]. Mod. Phys. Lett. B, 2019, 33: 1950191.

- Hu C C, Tian B, Wu X Y, et al. Mixed lump-kink and rogue wave-kink solutions for a (3+1)-dimensional B-type Kadomtsev-Petviashvili equation in fluid mechanics [J]. Eur. Phys. J. Plus, 2018, 133: 40.

- Fang T, Wang H, Wang Y H, et al. Lump–stripe interaction solutions to the potential Yu–Toda–Sasa–Fukuyama equation [J]. Anal. Math. Phys., 2019, 9: 1481–1495.

- Ma W X. Interaction solutions to Hirota–Satsuma–Ito equation in (2+1)–dimensions [J]. Front. Math. China, 2019, 14: 619–629.

- Sun Y L, Ma W X, Yu J P, et al. Lump and interaction solutions of nonlinear partial differential equations [J]. Mod. Phys. Lett. B, 2019, 33: 1950133.

- Ma W X, Yong X L, Zhang H Q. Diversity of interaction solutions to the (2+1)–dimensional Ito equation [J]. Comput. Math. Appl., 2018, 75: 289–295.

- Lin F H, Wang J P, Zhou X W, et al. Observation of interaction phenomena for two dimensionally reduced nonlinear models [J]. Nonlinear Dyn., 2018, 94: 2643–2654.

- Chen S J, Yin Y H, Ma W X, et al. Abundant exact solutions and interaction phenomena of the (2+1)–dimensional YTSF equation [J]. Anal.Math.Phys., 2019. [CrossRef]

- Lan Z Z. Dark solitonic interactions for the (3+1)–dimensional coupled nonlinear Schrödinger equations in nonlinear optical fibers [J]. Optics and Laser Technology, 2019, 113: 462–466.

- Huang L L, Yue Y F, Chen Y. Localized waves and interaction solutions to a (3+1)–dimensional generalized KP equation [J]. Comput. Math. Appl., 2018, 89: 831–844.

- Yue Y F, Huang L L, Chen Y. Localized waves and interaction solutions to an extended (3+1)-dimensional Jimbo–Miwa equation [J]. Appl. Math. Lett., 2019, 89: 70–77.

- Liu J G, He Y. New periodic solitary wave solutions for the (3+1)-dimensional generalized shallow water equation [J]. Nonlinear Dyn., 2017, 90.

- Liu J G, Zhu W H, Zhou L, et al. New periodic solitary wave solutions for the (3+1)–dimensional generalized shallow water equation [J]. Nonlinear Dyn., 2019, 97.

- Zhang R F, Bilige S D, Fang T, et al. New periodic wave, cross–kink wave and the interaction phenomenon for the Jimbo- Miwa- like equation [J]. Comput. Math. Appl., 2019, 78: 754–764.

- Zhao Z L, Chen Y, Han B. Lump soliton, mixed lump stripe and periodic lump solutions of a (2+1)-dimensional asymmetrical Nizhnik-Novikov-Veselov equation [J]. Mod. Phys. Lett. B, 2017, 31: 1750157.

- Zhang R F, Bilige S D. New interaction phenomenon and the periodic lump wave for the Jimbo-Miwa equation [J]. Mod. Phys. Lett. B, 2019, 33: 1950067.

- Hornik K. Approximation capabilities of multilayer feedforward networks [J]. Neural Networks,1991, 4 (2): 251-257. [CrossRef]

- Zhang R F, Bilige S D. Bilinear neural network method to obtain the exact analytical solutions of nonlinear partial differential equations and its application to p–gBKP equatuon [J]. Nonlinear Dyn.,2019, 95: 3041-3048.

- Zhang R F. Multiple exact analytical solutions of nonlinear partial differential equations based on bilinear transformation [D]. Master Thesis,Inner Mongolia University of Technology 2020.

- Gai L T, Bilige S D, Abundant multilayer network model solutions and bright-dark solitons for a (3 + 1)-dimensional p-gBLMP equation [J]. Nonlinear Dynamics, 2021, 106: 867-877.

- Zhu G Z, Wang H L, ao Mou Z, et al. Various solutions of the (2+1)-dimensional Hirota–Satsuma–Ito equation using the bilinear neural network method [J]. Chinese Journal of Physics, 2023, 83:292-305.

- Lv N, Yue Y C, Zhang R F, et al. Fission and annihilation phenomena of breather/rogue waves and interaction phenomena on nonconstant backgrounds for two KP equations [J]. Nonlinear Dynamics, 2023, 111: 10357-10366.

- Shen J L, Wu X Y. Periodic-soliton and periodic-type solutions of the (3+1)-dimensional Boiti–Leon–Manna–Pempinelli equation by using BNNM [J]. Nonlinear Dynamics, 2021, 106: 831–840.

- Qiao J-M, Zhang R-F, Yue R-X, et al. Three types of periodic solutions of new (3 + 1)-dimensional Boiti –Leon-Manna-Pempinelli equation via bilinear neural network method [J]. Mathematical Methods in the Applied Sciences, 2022, 45 (9): 5612–5621.

- Liu J-G, Zhu W-H, Wu Y-K, et al. Application of multivariate bilinear neural network method to fractional partial differential equations [J]. Results in Physics, 2023, 47: 106341. [CrossRef]

- Feng Y Y, Bilige S D. Resonant multi-soliton and multiple rogue wave solutions of (3+1)-dimensional Kudryashov-Sinelshchikov equation [J]. Phys. Scr., 2021, 96: 095217.

- Feng Y Y, Bilige S D, Zhang R F. Evolutionary behavior of various wave solutions of the (2+1)-dimensional Sharma–Tasso–Olver equation [J]. Indian J. Phys., 2022, 96: 2107–2114.

- Zeynel M, Yaşar E. A new (3 + 1) dimensional Hirota bilinear equation: Periodic, rogue, bright and dark wave solutions by bilinear neural network method [J]. Journal of Ocean Engineering and Science, 2022.

- Cao N, Yin X, Bai S, et al. Breather wave, lump type and interaction solutions for a high dimensional evolution model [J]. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 2023, 172: 113505.

- Bai S T, jun Yin X, Cao N, et al. A high dimensional evolution model and its rogue wave solution, breather solution and mixed solutions [J]. Nonlinear Dynamics, 2023, 111: 12479–12494.

- Zhang Y, Zhang R F, Yuen K V. Neural network-based analytical solver for Fokker–Planck equation[J]. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 2023, 125: 106721. [CrossRef]

- Zhang R F, Li M C, Albishari M, et al. Generalized lump solutions, classical lump solutions and rogue waves of the (2+1)–dimensional Caudrey-Dodd-Gibbon-Kotera-Sawada-like equation [J]. Appl. Math. Comput., 2021, 403: 126201.

- Zhang R F, Li M C, Yin H M. Rogue wave solutions and the bright and dark solitons of the (3+1)-dimensional Jimbo–Miwa equation [J]. Nonlinear Dyn., 2021, 103: 1071-1079.

- Konopelchenko B, Dubrovsky V. Some new integrable nonlinear evolution equations in 2+1 dimensions [J]. Phys. Lett. A, 1984, 102 (1): 15–17. [CrossRef]

- Manafian J, Lakestani M. N-lump and interaction solutions of localized waves to the (2+1)-dimensional variable-coefficient Caudrey-Dodd-Gibbon-Kotera-Sawada equation [J]. J. Geom. Phys., 2020, 150: 103598.

- Cheng X P, Yang Y Q, Ren B, et al. Interaction behavior between solitons and (2+1)-dimensional CDGKS waves [J]. Wave Motion, 2019, 86: 150–161.

- Tang Y, Tao S, Guan Q. Lump solitons and the interaction phenomena of them for two classes of nonlinear evolution equations [J]. Comput. Math. Appl., 2016, 72 (9): 2334–2342. [CrossRef]

- Wazwaz A-M. Painlevé analysis for new (3+1)-dimensional Boiti-Leon-Manna-Pempinelli equations with constant and time-dependent coefficients [J]. International Journal of Numerical Methods for Heat and Fluid Flow, 2020, 30: 4259–4266.

- Liu J G, Du J Q, Zeng Z F, et al. New three-wave solutions for the (3+1)-dimensional Boiti-Leon-Manna-Pempinelli equation [J]. Nonlinear Dyn., 2017, 88.

- Hu L, Gao Y T, Jia T T, et al. Higher-order hybrid waves for the (2 + 1)-dimensional Boiti-Leon-Manna-Pempinelli equation for an irrotational incompressible fluid via the modified Pfaffian technique[J]. Z. Angew. Math. Phys., 2021, 72.

- Gai L T, Ma W X, Li M C. Lump-type solutions, rogue wave type solutions and periodic lump-stripe interaction phenomena to a (3+1)-dimensional generalized breaking soliton equation [J]. Phys. Lett. A, 2020, 384: 126178.

- Chen R D, Gao Y T, Yu X, et al. Periodic-wave solutions and asymptotic properties for a (3+1)-dimensional generalized breaking soliton equation in fluids and plasmas [J]. Mod. Phys. Lett. B, 2021, 35: 2150344.

- Niwas M, Kumar S, Kharbanda H. Symmetry analysis, closed-form invariant solutions and dynamical wave structures of the generalized (3+1)-dimensional breaking soliton equation using optimal system of Lie subalgebra [J]. Ocea. Eng. Sci., 2021. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2468013321000693. [CrossRef]

- Darvishi M, Najafi M, Kavitha L, et al. Stair and Step Soliton Solutions of the Integrable (2+1) and (3+1)-Dimensional Boiti-Leon-Manna-Pempinelli Equations [J]. Communications in Theoretical Physics, 2012, 58 (6): 785–794.

- Liu J G. Double-periodic soliton solutions for the (3+1)-dimensional Boiti-Leon- Manna- Pempinelli equation in incompressible fluid [J]. Comput. Math. Appl., 2018, 75: 3604–3613.

- Shakeel M, Mohyud-Din S T. Improved (G’/G)-expansion and extended tanh methods for (2+1)-dimensional Calogero-Bogoyavlenskii-Schiff equation [J]. Alexandria Engineering Journal, 2015, 54 (1): 27–33.

- Chen S T, Ma W X. Lump solutions of a generalized Calogero-Bogoyavlenskii-Schiff equation [J]. Comput. Math. Appl., 2018, 76 (7): 1680-1685.

- Zhang RF, The Neural Network Method for Solving Exact Solutions of Nonlinear Partial Differential Equations[D], Ph.D thesis, Dalian University of Technology, 2023.

- Zhang RF, Li MC, Bilinear residual network method for solving the exactly explicit solutions of nonlinear evolution equations [J]. Nonlinear Dynamics, 2022, 108: 521- 531. [CrossRef]

- Zhang RF, Li MC, Cherraf A, Vadyala SR. The interference wave and the bright and dark soliton for two integro-differential equation by using BNNM [J]. Nonlinear Dynamics, 2023, 111: 8637–8646. [CrossRef]

- Zhang RF, Li MC, Gan JY, Li Q, Lan ZZ. Novel trial functions and rogue waves of generalized breaking soliton equation via bilinear neural network method [J]. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 2022, 154: 111692. [CrossRef]

- Zhang RF, Li MC, Albishari M, Zheng FC, Lan ZZ. Generalized lump solutions, classical lump solutions and rogue waves of the (2+1)-dimensional Caudrey Dodd Gibbon Kotera Sawada like equation [J]. Applied Mathematics Computation, 2021, 403:126201.

- Zhang RF, Li MC, Yin HM. Rogue wave solutions and the bright and dark solitons of the (3+1)-dimensional Jimbo–Miwa equation [J]. Nonlinear Dynamics, 2021, 103: 1071–1079. [CrossRef]

- Zhang RF, Bilige SD, Liu JG, Li MC. Bright-dark solitons and interaction phenomenon for p-gBKP equation by using bilinear neural network method [J]. Physica Scripta, 2021, 96:055224. [CrossRef]

- 2024; Zhu Guangzheng, Constructing Analytical Solutions for Nonlinear Partial Differential Equations Using Bilinear Neural Network Method[D], Master Thesis, Guangxi Normal University 2024.

- [258]Zhang RF*, Li MC, Fang T, Zheng FC, Bilige SD. Multiple exact solutions for the dimensionally reduced p-gBKP equation via bilinear neural network method [J]. Modern Physics Letters B, 2022, 36:2150590. [CrossRef]

- [259]Zhang RF*, Li MC, Esmail AM, Zheng FC, Bilige SD. Rogue waves, classical lump solutions and generalized lump solutions for Sawada-Kotera-like equation [J]. International Journal of Modern Physics B, 2022, 36:2250044.

- Qiao JM, Zhang RF*, Yue RX*, Rezazadeh H, Seadawy AR. Three types of periodic solutions of new (3 + 1)-dimensional Boiti–Leon–Manna–Pempinelli equation via bilinear neural network method [J]. Mathematical Methods in Applied Sciences, 2022, 45: 5612-5621.

- Zhang Y, Zhang RF*, Yuen KV*, Rezazadeh H, Seadawy AR. Neural network-based analytical solver for Fokker–Planck equation [J]. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 2023, 125: 106721 (SCI Q1). [CrossRef]

- Lv N, Yue YC, Zhang RF, Yuan XG, Wang R. Fission and annihilation phenomena of breather/rogue waves and interaction phenomena on non-constant backgrounds for two KP equations [J]. Nonlinear Dynamics, 2023, 111: 10357-10366 (SCI Q1).

- Gai LT, Qian YH, Zhang RF, Qin YP. Periodic bright-dark soliton, breather-like wave and roguewave solutions to a p-GBS equation in (3+1)-dimensions [J]. Nonlinear Dynamics, 2023, 111: 15335–15346.

- Liu JG, Wazwaz AM, Zhang RF, Lan ZZ, Zhu WH. Breather-wave, multiwave and interaction solutions for the (3+1)-dimensional generalized solition equation [J]. Journal of Applied Analysis & Computation, 2022, 12: 2426-2440.

- Li MY, Bilige SD*, Zhang RF, Han LH. Diversity of interaction phenomenon, crosskink wave, and the bright-dark solitons for the (3+1)-dimensional Kadomtsev-Petviashvili–Boussinesq- like equation [J]. International Journal of Nonlinear Sciences and Numerical Simulation, 2022, 23: F623-634.

- .

- Feng YY, Bilige SD, Zhang RF. Evolutionary behavior of various wave solutions of the (2+1)-dimensional Sharma-Tasso-Olver equation [J]. Indian Journal of Physics, 2022, 96: 2107–2114. [CrossRef]

- Han LH, Bilige SD, Wang XM, Li MY, Zhang RF. Rational Wave Solutions and Dynamics Properties of the Generalized (2+1)-Dimensional Calogero-Bogoyavlenskii-Schiff Equation by Using Bilinear Method [J]. Advances in Mathematical Physics, 2021, 2021: 9295547. [CrossRef]

- Lukas Mouton, Florentin Reiter, Ying Chen, Patrick Rebentrost, Deep-Learning-Based Quantum Algorithms for Solving Nonlinear Partial Differential Equations[J], Physical Review A, 2024,110, 022612. [CrossRef]

- 2024; Rolfo S, Machine Learning-Driven Numerical Solutions to Partial Differential Equations[J], Journal of Applied & Computational Mathematics, 2024, 13(4), 1-2.

- Yash Kumar, Subhankar Sarkar & Souvik Chakraborty, GrADE: A graph based data-driven solver for time-dependent nonlinear partial differential equations[J], Mach. Learn. Comput. Sci. Eng., 2025,1, 7. [CrossRef]

- Abdul Mueed Hafiz, Irfan Faiq & Hassaballah M., Solving partial differential equations using large-data models: a literature review[J], Artif Intell Rev. 2024, 57, 152. [CrossRef]

- Di Mei, Kangcheng Zhou, Chun-Ho Liu, Unified finite-volume physics informed neural networks to solve the heterogeneous partial differential equations[J], Knowledge-Based Systems, 2024, Vol. 295, No. C.

- Benjamin G. Cohen, Burcu Beykal, George M. Bollas, Physics-informed genetic programming for discovery of partial differential equations from scarce and noisy data[J], Journal of Computational Physics, Vol. 514, No. C. [CrossRef]

- Qingsong Xu, Yilei Shi, Jonathan Bamber, Chaojun Ouyang, Xiao Xiang Zhu, Physics- embedded Fourier Neural Network for Partial Differential Equations, arXiv:2024, 2407.11158.

- Sachin Kumar, Setu Rani, Nikita Mann, Analytical Soliton Solutions to a (2 + 1)- Dimensional variable Coefficients Graphene Sheets Equation Using the Application of Lie Symmetry Approach: Bifurcation Theory, Sensitivity Analysis and Chaotic Behavior[J], Qualitative Theory of Dynamical Systems, 2025, 24(2),80. [CrossRef]

| Method | Advantages | Challenges | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) | - Integrates physical laws into training. - Reduces dependence on labeled data. - Solves forward and inverse problems simultaneously. - Handles high-dimensional PDEs. |

- Computationally expensive, especially for complex systems. - Struggles with stiff PDEs or noisy data. - Requires careful balance of loss terms (physics vs. data). |

- Solving PDEs with limited or no data. - Inverse problems in engineering (e.g., finding material properties). - Multi-physics simulations. |

| Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) | - General-purpose and flexible. - Effective for both linear and nonlinear mappings. - Can approximate any continuous function (universal approximation theorem). |

- Requires large datasets for accurate training. - Lacks interpretability for scientific applications. - Prone to overfitting on small datasets without regularization. |

- Function approximation in nonlinear systems. - Prediction in time-series models. - General data-driven PDE solutions. |

| Deep Galerkin Method (DGM) | - Efficient for high-dimensional PDEs (avoids grid-based methods). - Trains on scattered data points. - Adaptive and flexible for non-standard boundary conditions. |

- Computational overhead for high-dimensional parameter spaces. - Sensitive to hyperparameter tuning. - May struggle with non-smooth solutions or sharp gradients. |

- Financial modeling (e.g., Black-Scholes equation). - High-dimensional Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman equations. - Quantum systems with many variables. |

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) | - Effective for spatially structured data. - Learns hierarchical features (local-to-global patterns). - Translational invariance improves generalization for grid-based data. |

- Limited for irregular geometries or unstructured data. - Requires data in grid format. - Computationally intensive for high resolutions. |

- Image-based PDEs (e.g., seismic inversion). - Structured grid problems (e.g., fluid dynamics on a uniform grid). |

| Fourier Neural Operators (FNOs) | - Captures global dependencies efficiently. - Resolution-independent once trained. - Suitable for high-dimensional problems and long-range correlations. - Fast inference after training. |

- Training can be computationally intensive. - Requires large, diverse datasets for generalization. - Sensitive to frequency mode selection and domain configurations. |

- Parametric PDEs with varying initial/boundary conditions. - Fluid dynamics (e.g., Navier-Stokes equations). - Problems with global spatial dependencies. |

| DeepONet (Deep Operator Network) | - Learns operators, not just solutions. - Real-time inference for varying input functions. - Handles parametric PDEs with ease. - Generalizes across multiple configurations. |

- High computational cost for generating training data. - Requires diverse input-output pairs. - May struggle with rare or out-of-distribution inputs. |

- Learning mappings between function spaces. - Operator discovery in physics. - Control systems with varying conditions. |

| Reinforcement Learning (RL) | - Adaptive to changing environments. - Solves sequential decision-making problems. - Handles dynamic systems and optimization tasks naturally. - Requires no labeled data. |

- High computational cost for training. - Sparse rewards lead to slower convergence. - May struggle with stability in high-dimensional spaces. |

- Optimal control problems. - Adaptive boundary condition modeling. - Dynamic systems with feedback loops. |

| Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) | - Gradient-free optimization. - Robust to noisy and discontinuous landscapes. - Handles black-box problems effectively. - Avoids local minima traps. |

- Computationally expensive for large search spaces. - Slow convergence for complex or high-dimensional systems. - Requires well-defined fitness functions. |

- Parameter optimization for complex PDE solvers. - Adaptive mesh generation. - Solving non-differentiable or discrete problems. |

| Genetic Programming (GP) | - Discovers symbolic, interpretable solutions. - Effective for problems with missing terms. - Can evolve functional forms directly. - Handles nonlinear dynamics naturally. |

- High computational cost. - Risk of premature convergence. - Requires careful design of crossover and mutation operators. |

- Symbolic PDE discovery. - Closed-form solution generation. - Data-driven discovery of governing equations. |

| Hybrid AI-Numerical Methods | - Combines accuracy of numerical methods with flexibility of AI. - Reduces computational overhead for large-scale problems. - Enhances solution stability and accuracy. |

- Complex implementation. - Integration of AI and traditional solvers can be non-trivial. - Potential for increased computational overhead in hybrid systems. |

- Multiscale simulations. - Coupling turbulence models with AI. - Large-scale fluid dynamics and material simulations. |

| Transfer Learning | - Reduces training time by reusing pre-trained models. - Effective for low-data scenarios. - Leverages knowledge from related domains. |

- Risk of negative transfer if source and target domains differ significantly. - Fine-tuning can introduce overfitting. - Requires careful domain analysis. |

- Low-data PDE problems. - Domain adaptation for scientific applications. - Transfer of pretrained physics models to new scenarios. |

| Supervised Learning | - Straightforward training process. - Handles labeled data effectively. - Can use standard loss functions for clear optimization goals. |

- Requires large labeled datasets. - Prone to overfitting without careful regularization. - Less effective when dealing with partial or noisy data. |

- Classification and regression problems. - Learning mappings for time-dependent or steady-state PDEs. - General numerical PDE approximation. |

| Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) | - Learns complex distributions effectively. - Generates high-quality synthetic data. - Effective for data augmentation and pattern discovery. - Stochastic PDE modeling is possible. |

- Training instability and mode collapse issues. - Requires careful tuning of generator-discriminator balance. - Computationally expensive to train. |

- Generating synthetic data for physics-based problems. - Stochastic PDEs or uncertainty modeling. - Discovering hidden patterns in datasets. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).