1. Introduction

In recent years, a global increase in drug consumption has been observed, both in general consumption figures and in the percentage of the world's population that consumes drugs. In 2009, the estimated 210 million users represented 4.8% of the global population aged 15 to 64, up from 269 million in 2018, or 5.3% of the population (United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime, 2020). The highest proportion of drug users corresponds to young adults and adolescents, although the percentages of people over 45 years of age with chronic consumption increase every year (European Monitoring Center of Drug Dependence and Addiction, 2017). This consumption is globally more widespread in developed countries than in developing ones.

In order to do an exercise that allows us to foresee the future, it is necessary to know the past and contextualize the present (Moradiellos, 2009). If we intend to explain this phenomenon of drug consumption and its future, a series of fundamental premises must be accepted in the analysis: the use of substances and other addictive behaviors is a multifactorial, non-linear phenomenon, of diverse etiology, where no causal explanations can be used (one cause: one effect), but the different causes root in a complex way with the various consequences. It is a global phenomenon, especially since the end of the 20th century, so any explanation of the evolution of the phenomenon in the Spanish context or in more local contexts must include elements of connection with broader environments (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) and cultural and social phenomena that have been modified over time (Uris, 1995; Elzo et al, 2000). The phenomenon of drug consumption must be contextualized and analyzed with the criteria and categories of each historical and social context, avoiding moral judgments, ethnocentric biases (Harris, 1999) and political arguments, which, in many cases, have served as an excuse or justification fir the appearance, consolidation, maintenance and/or eradication of many of the consequences linked to drug consumption (Edwards and Arif, 1981). Finally, the terminology has been advancing as different aspects of the phenomenon have been known, documented and evidenced, which requires analyzing the concepts and explaining the terms, understanding their meanings within the aforementioned social contexts (Torres, 2009).

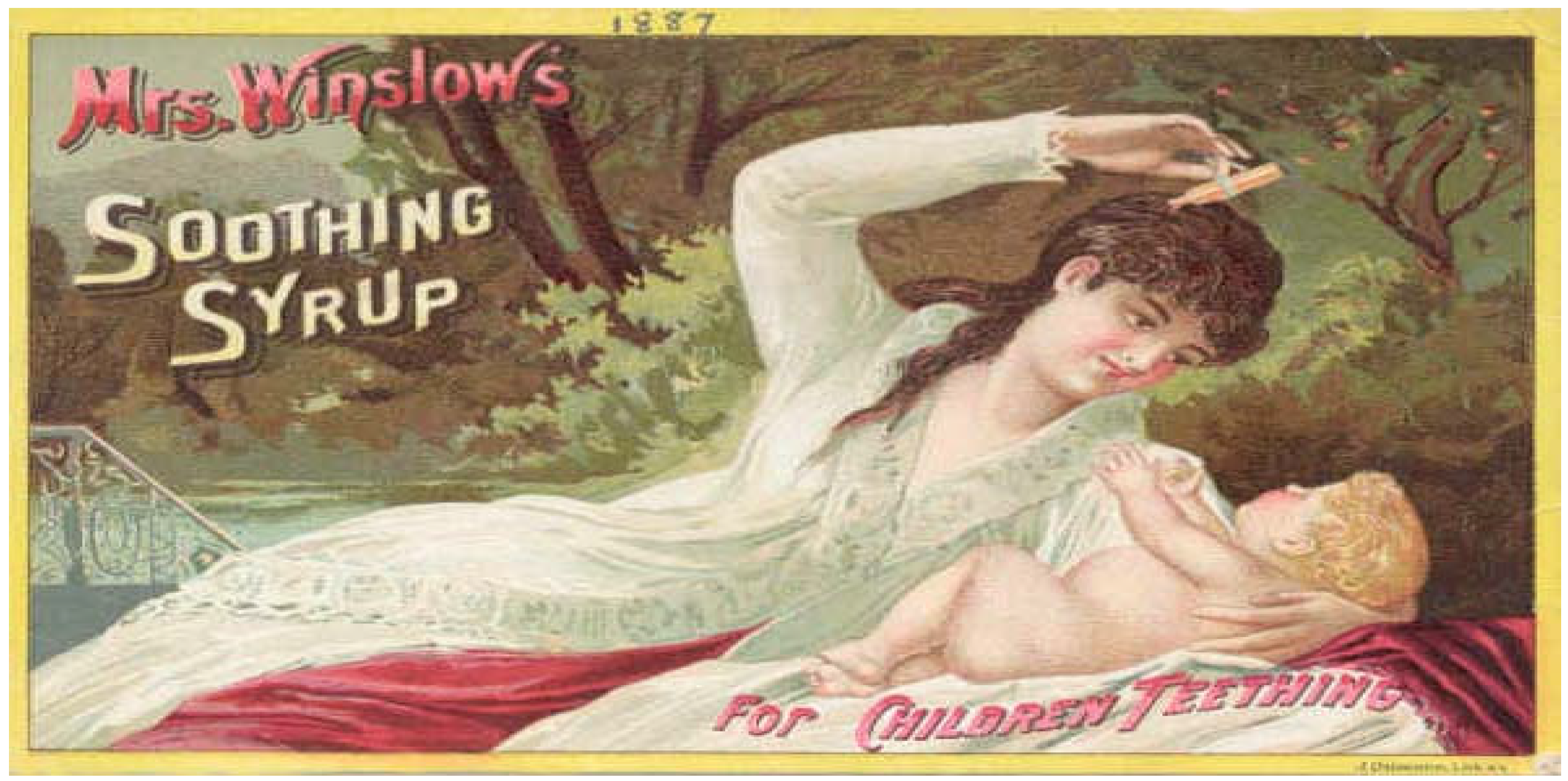

The future of drugs looks too much like the past of substance use. Opioids are a class of drugs found naturally in the poppy plant (Gamella and Martín, 1994). Some opioids are extracted directly from plants, while others are produced in laboratories where scientists use the same chemical structure to create synthetic or semi-synthetic opioids. There isn't much difference between Mrs. Winslow's morphine syrup to reduce tooth pain in teething infants (

Figure 1) and using hypnotics to help "anxious" children sleep at night.

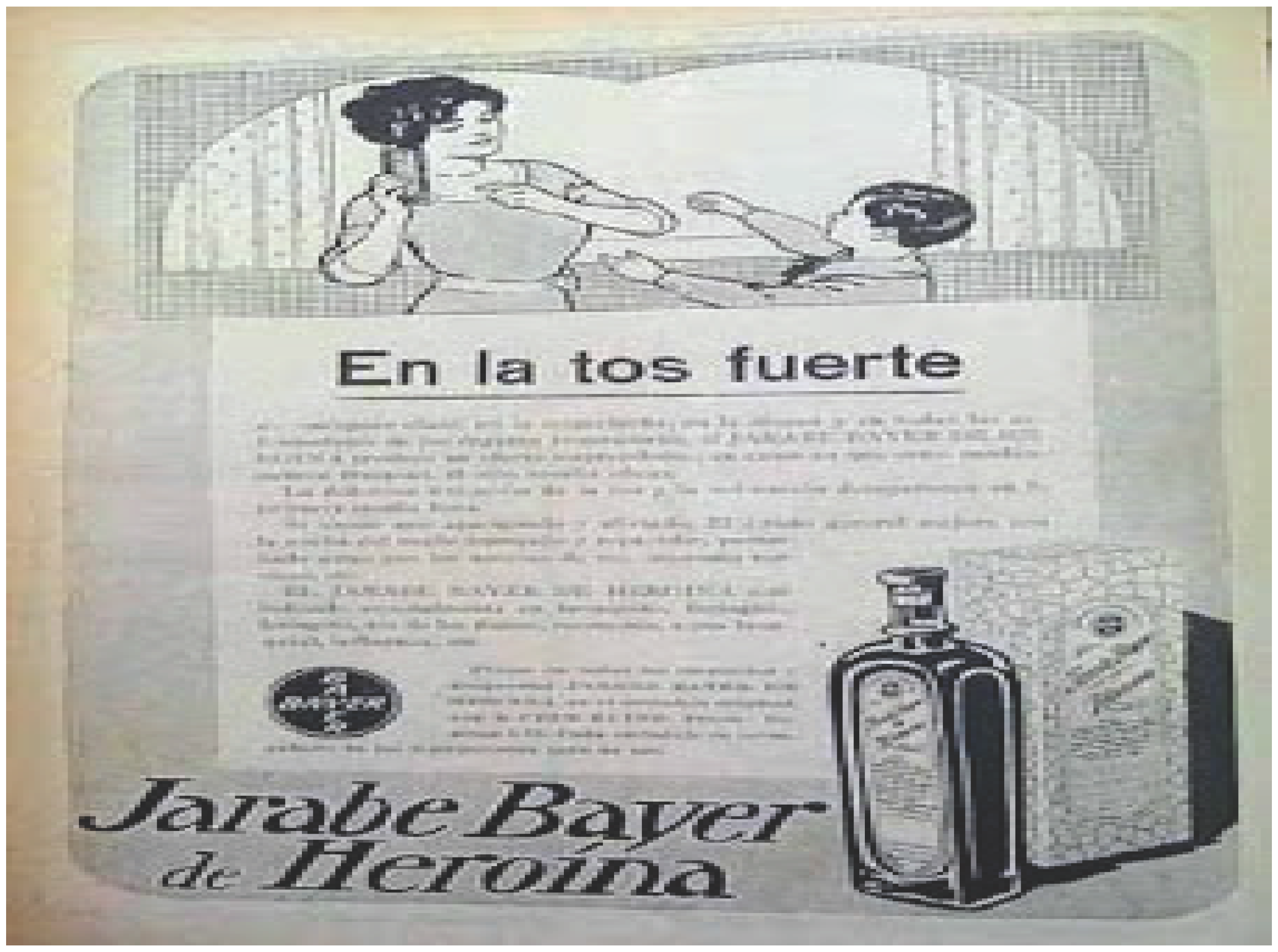

The messages about the use of Bayer cough syrup (made with heroin, let no one forget) (

Figure 2) and the use of alcohol to whet the appetite in children are quite similar to the advertising of technologies and the message of science as a dogma, which are systematically repeated when trying to explain the possible negative consequences of its use. Substances have been present in the development of humanity for thousands of years, both in their therapeutic aspect and in the recreational aspect (NO ENTIENDO ESTE AÑADIDO AQUÍ; QUIZÁ “IMPLICATIONS”, “DERIVATIONS”,…). It is still common for the most toxic way of consuming them to be legitimized with therapeutic use; drug use is still carried out to achieve status in the group or to escape from problems, while it is legitimized in normative individualism and is intended to be abstracted from social mechanisms (Escohotado, 2002; Laespada and Iraurgi, 2009; Vega, 1992; Oughorlian, 1977).

The use of opiates has also changed since the end of XXth century. The use of heroine, especially in the injected way, has been considered as the highest stigma on drug use (Kulesza et al, 2016). Also, the social identity “junky” has created a depictive label for drug users, with the negative perception of the concept (it´s not unusual to find drugs users under treatment than reject the identity “junky”). The situation during the XXIst century is a clear paradox about these strange days in epidemiology and social perspectives of substance use: if there is an epidemic on drug use, actually it´s the clear abuse of prescription pills, mostly of them opiate derivates, which have increased the problems of a lot of regular people all around the world (NIDA, 2024; EMCDDA, 2022; WHO and UNODC, 2022; OEDA, 2023).

The aim of this paper is to make a revision about the actual situation of use of these opiate derivates, fundamentally the evolution of the use of these prescription pills and the consequences/aftermaths of their use for general population. As a secondary aim, the prospective perspective will be used to determinate the risks and processes for next future in the use of these substances.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology

The research was conducted using the method of historical logic as the central axis of analysis and reflection (Moradiellos, 2001) and using the qualitative research content analysis technique as a procedure in performing scientific tasks, with the study of historical trends as an object of research. The method of analysis used in this article is a specific method of critical discourse analysis (CDA) and is supported by the researchers' feedback on the results of the analysis. This section will discuss the importance of discourse analysis (DA) and critical discourse analysis (CDA). The approach used in this paper will then be described in relation to CDA (Gee, 2014). According to Gee, DA is the study of the use of language to perform three functions: to communicate messages, to perform actions, and to position oneself in relation to others (Gee, 2014). There are different types of DA. While some DA methods are considered descriptive and may focus on the nature of language and how it works, other methods are considered critical and seek to move beyond the pure understanding and expression of language, but seek to understand the existence of language in some way. Gee describes proponents of the second approach as follows:

"They also want to talk about and even intervene in institutional, social or political issues, problems and contradictions in the world."

In particular, Gee contrasts researchers who criticize critical methods as "unscientific" because they contribute to the destruction of objectivity in the research process. On the other hand, supporters of the critical approach claim that this approach is necessary if we want to be only passive observers who only describe events and phenomena and assume our social and political responsibility for change. Critical approaches promote engagement with social causes, using self-reflection to challenge the unfair shortcomings that arise, for example, from reductionist and/or dogmatic arguments that ignore complexity. The goal is to promote inclusion based on publicly accepted ethical principles. Many authors cite several principles that help TO define the critical method. In particular, Van Dijk lists eight principles as characteristics of the CDA approach (see

Table 1 below).

The approach used in this article, while having strong affinities with the principles mentioned above, is more concerned with the relationship between disciplines than with groups of people, although it does not exclude this dimension either. In fact, it can be said that any discipline is likely to reflect a "paradigm" consciously or unconsciously adopted by its practitioners. Therefore, for the sake of accuracy, the approach of this article could perhaps be more accurately described as Critical Discipline Discourse Analysis (or CDDA) to emphasize where the emphasis lies (Wodak, 2001). This method examines three community-oriented disciplines, referring to key texts and references and comparing them along the following key dimensions:

define levels;

philosophical level;

strategy/method level;

Measuring/monitoring performance levels. A possible criticism that can be raised here is that it can be argued that there may be a bias in the selection of argument sources. There are two responses to this criticism: First, select key references representing the three disciplines covered to build AN argument. Second, feedback was sought on an earlier version of this article from seven academics representing each of the three disciplines covered (some of whom had cross-disciplinary backgrounds) to understand the relevance of the arguments and how they could be improved. The feedback received helped TO refine and further develop the ideas in this article. However, it is clear that there are multiple perspectives within these disciplines that can also be influenced by 'ideological' perspectives (Fairclough and Wodak, 1997).

3. Results

The use of drugs depends on what they chemically and biologically offer, and also on what they represent as pretexts for minorities and majorities. They are certain substances, but the administration guidelines depend greatly on what you think about them at each time and place. Specifically, the conditions of access to its consumption are at least as decisive as what is consumed. (Escohotado, 2002).

Opioids are a class of drugs that includes heroin, synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, and some morphine-derived pain relievers such as oxycodone, hydrocodone, codeine, and others. These synthetic opioids are the true pharmaceutical epidemic of the 21st century, and it must be said that this epidemic is occurring and will continue to develop, especially with the use of synthetic opioids, which are drugs derived from opium and produced from a neurochemical. In perspective, these companies invest a lot of money to develop highly effective products that have huge addictive potential and are safe due to their marketing and advertising campaigns and images of harmless effects and therefore easy to spread.

Billings and Block described the use of a morphine drip as “slow euthanasia”. And, in a statement about physician-assisted suicide, the US Supreme Court described this treatment as pain relief that advances death. Wall believes these views perpetuate myths surrounding the use of morphine, despite the fact that claims about its addictive potential and safety have now been successfully challenged. He concludes that “we must help patients to be absolutely clear that their treatment for pain is just that, it is not an alternative route to an early grave (Sykes and Thorns, 2003)

As mentioned in the introduction, this is not a new phenomenon, as both morphine and heroin experienced similar circumstances from discovery to prohibition and stigmatization (Earnshaw, 2013), although they have been shown to have analgesic effects and be useful for terminally ill patients, but disproportionately due to use and chronic pain.

Opioids and sedative drugs are commonly used to control symptoms in patients with advanced cancer. However, it is often assumed that the use of these drugs inevitably results in shortening of life. Ethically, this outcome is excused by reference to the doctrine of double effect. In this review, we assess the evidence for patterns of use of opioids and sedatives in palliative care and examine whether the doctrine of double effect is needed to justify their use. We conclude that patients are more likely to receive higher doses of both opioids and sedatives as they get closer to death. However, there is no evidence that initiation of treatment, or increases in dose of opioids or sedatives, is associated with precipitation of death. Thus, we conclude that the doctrine of double effect is not essential for justification of the use of these drugs, and may act as a deterrent to the provision of good symptom control. (Sykes and Thorns, 2003)

Synthetic opioids are currently the drugs most commonly associated with overdose deaths in the United States and their use is beginning to spread to other countries, as has occurred in Europe through France, Germany and, to a lesser extent, Spain. Fentanyl is produced in the laboratory. The most common are fentanyl, oxycodone, and hydrocodone (NIDA, 2023).

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid similar to morphine. Like morphine, it is often used to treat patients with severe pain, especially after surgery. It is also sometimes used to treat chronic pain patients who have physical tolerance to other opioids. This synthetic product is sold illegally in powder form, dripped onto absorbent paper, in eye drop or nasal spray containers, or in pills similar to other prescription opioids. Some drug users mix fentanyl with other drugs such as heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine and MDMA. They do this because a very small amount of fentanyl can cause a high concentration, making it a cheaper option. This is especially dangerous when drug users are unaware that the drugs they are using may contain fentanyl as a cheap but dangerous additive. They may take stronger opioids than their bodies are used to and are more than likely to overdose (NIDA, 2023).

Oxycodone is a drug in the opioid family used to treat moderate to severe pain. It is usually taken orally and is available in immediate-release and controlled-release formulations. The immediate-release formula generally provides pain relief. In some countries it is distributed to be used parenterally (injected), which greatly increases its risk. For a long time, it was defended according to the American DEA (Drug Enforcement Administration) and the manufacturers of this medication, that it was very rare for psychological addiction to appear when it was used in the recommended doses and for not very long periods of time. Not only was this not true, but it generated a false image of safety in the use of the opiate that greatly increased its use, both on prescription and over the counter (NIDA, 2023).

Its abuse profile is similar to other opioids, so it became instantly popular and abused by people with addiction problems. The drug's contraindications even explain how they can be used in addictive ways: "Extended-release tablets should not be crushed, chewed, or crushed, as this may cause an overdose."

After oxycodone was introduced to the market in 1995, cases of abuse began to emerge. Bypassing the long-acting mechanism, some users crush oxycodone tablets into a powder and then self-administer intranasally, intravenously, intramuscularly or subcutaneously, or even rectally to promote rapid absorption into the body. Most oxycodone-related deaths involve taking relatively large amounts of the drug with other substances, such as alcohol or certain benzodiazepines. Drug company owners insist on this to avoid admitting that their drugs are responsible for hundreds of thousands of opioid overdose deaths in the United States in the 21st century.

In fact, they still advocate that “While high doses of oxycodone can be fatal for someone who is not addicted or who has not yet developed tolerance, this is not the most common case (NIDA, 2023).

Hydrocodone is also a synthetic opioid, in this case an opioid derived from codeine, used as an oral pain reliever and cough suppressant to treat moderate to severe pain. It is available in tablets, syrup or capsules and is considered a narcotic substance that can cause addiction and severe withdrawal symptoms. In 1943, in the middle of World War II, the aforementioned FDA approved the drug for sale in the United States. In 2014, the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) listed hydrocodone on Schedule II of the Controlled Substances Act, which means it has a high potential for abuse, has very limited medical use, and can cause serious psychological or physical harm. As an anesthetic, it relieves pain by binding to opiate receptors in the brain and spinal cord. When used with alcohol, it can increase dizziness. Hydrocodone can be addictive and cause physical and mental dependence. The likelihood of addiction varies from person to person. The sale and production of these drugs has increased significantly in recent years, as has their diversion and illegal use in the United States. Hydrocodone has most of the side effects of other opioids, such as euphoria, drowsiness, and nightmares. Like the aforementioned oxycodone, it remains one of the most widely used recreational drugs in the United States well into the 21st century. Hydrocodone users report satisfaction, especially at higher doses. Others mention a euphoric or warm feeling in the body, which is one of the more well-known effects of the drug.

As with heroin's original use, hydrocodone was found in more than 200 cough syrup and lozenge formulations until the FDA pushed for a review of these formulations in 2006 in the wake of deaths of children under six years old. In 2010, 9 out of 10 medications containing hydrocodone were withdrawn from the market (NIDA, 2023).

The combined use of these substances is a real epidemiological and social problem in various countries, especially in the United States. Between 1999 and 2008, there was a significant increase in overdose deaths and the sale and abuse of painkillers. Since 2015, heroin has killed more people in the United States each year than car crashes and shootings combined. Drug overdose is the leading cause of death in Americans under the age of 50, with opioids currently responsible for two-thirds of deaths. This has contributed to a decline in life expectancy in the United States in recent years. Unlike in the past, drug addiction is no longer limited to certain social groups in big cities, but mostly affects middle-class Americans in rural areas. The main reason is that opioids are too easy to use for pain relief.

Over the past two decades, the opioid epidemic in the United States has killed more than half a million people from overdoses, according to government data. In parallel, more than 3,300 opioid lawsuits have been filed nationwide against the drug's manufacturers, distributors, and pharmacy chains (NIDA, 2023).

In Europe, opioid consumption has not had the brutal consequences that have been identified in the USA, but its use cannot be considered moderate.

Opioid use remains a major part of the drug problem in Europe and a major contributor to the associated harms. Heroin is the most frequently used illicit opioid, but other opioids such as methadone, buprenorphine, tramadol, fentanyl derivatives and benzimidazole opioids (nitazenes) are also available on the illicit market (for definitions, see Box Opiates, opioids and heroin). Due to data availability, this module of EU Drug Markets: In-depth analysis focuses on heroin. However, where information is available, analysis is also presented on other opioids commonly found on the illicit market in the EU (EMCDDA, 2024).

Countries like Spain have tripled their use of opioid analgesics in the general population (OEDA, 2023), with consumption data close to those of the US population, but without, yet, reaching their intensity of use and its devastating consequences.

15.8% of the Spanish population aged 15 to 64 admits having used opioid painkillers with or without a prescription occasionally. As with hypnosedatives, although with a smaller difference, the consumption of these substances is more widespread among women than among men, with their prevalence increasing in both groups over time. as age does. Evolutionarily, there is an increase in the prevalence of consumption in both men as in women, for the time periods of once in life and last 30 days. Codeine and tramadol are the opioid analgesics that have a higher prevalence of consumption among the population aged 15 to 64 years. Although, in both cases their consumption has decreased in favor of fentanyl and other opioids. (oxycodone, hydromorphone, pethidine, tapentadol, methadone and buprenorphine) (OEDA, 2023).

The opioid market is increasingly complex, including diverted medicines and internationally controlled and new synthetic opioids from a range of sources. Methadone, buprenorphine, fentanyl and its derivatives and new highly potent synthetic opioids have become more visible in data on health outcomes. In 2021, six new synthetic opioids were reported for the first time to the EU Early Warning System on new psychoactive substances, of which three were benzimidazoles and three were classed as other opioids (EMCDDA, 2024).

4. Discussion

Since the beginning of the 21st century, data linking mental disorders, drug use and low income have emerged internationally (UNODC, 2020), as well as various anthropological theories that integrate all factors and the ways in which they reinforce each other, such as how epidemic theory (Singer, 2009). Exacerbating the problem is the increasing complexity of the current drug market, both in terms of the physical market and the use of Internet to obtain various drugs, specifically hundreds of synthetic substances, many of which are not under international control (EMCDDA, 2017; EMCDDA, 2024; National UNDP, 2022). In addition, a significant and rapid increase in the consumption of psychotropic substances other than prescription drugs has been observed (WHO and UNODC, 2020; UNODC, 2020; EMCDDA, 2017). Even with the data, images of substance use remain highly stereotypical: young, male, illicit drug users, recreational or recreational use, urban settings. It is the identity of the consumer in the collective imagination that Jenkins defines as “social identity” (Jenkins, 1996). Meanwhile, in a demographic study on drug and technology use among people aged 14 to 18 (in Spain the study is called ESTUDES), the prevalence of alcohol use is now higher among women than among men. Among males of all ages and all time periods analyzed, the largest gender differences found in historical series were obtained. In intensive use of all alcoholic beverages ("binge drinking", i.e. drinking with the intention of getting drunk quickly in the shortest possible time), the frequency of the above-mentioned use is higher in girls than in boys in all analyzed age groups.Of course, this ratio shows the percentage of female drinkers vs. male drinkers rather than the amount of alcohol consumed, but the data is significant and shows a trend that has remained stable over the years and invisible to the public, what impact it may have in the near future.

Perhaps in ten years we will know if the danger is really over, or if a new opioid epidemic will spread in pharmacies, while the great masters of Spanish drug research continue to predict the future "heroin epidemic". Fortunately, this never happens.

5. Conclusions

The drugs of the 21st century are no longer the socially stigmatized drugs of the 20th century (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2013). The heroin of the 21st century is synthesized in the laboratory of an American pharmaceutical company and is wrapped in scientific validity and protected by paid publications in the Journal Citation Index. From now on, the choice between the red pill and the blue matrix pill will be easy, as "chemsex" users will be taking two pills at the same time, one for erection and one for psychotropic effects. Although technology may appear to be an advance in human relationships and behavioral patterns, it is actually easy to discover old patterns, errors, biases and heuristics of human behavior in their use: emotional biases, external attributions, availability heuristics, echo chamber ("ecological. chamber"), above set control error (or excess, they are compatible),... The tools used have changed, the procedures used have changed, the goal and purpose have not changed.

In this sense, the future of drugs looks all too similar to the past of addiction. Substances have been a part of human development for thousands of years, both therapeutically and recreationally, and the complications they cause. The most toxic forms of consumption are still commonly legalized for therapeutic use. Drug use is still done to achieve status in a group or to avoid problems, even if it is legitimate within the framework of normative individualism and aims to abstract from social mechanisms. The moral, political and economic dimensions of its use persist (Pinker, 2018), becoming increasingly selfish, lying, impulsive and individualistic (Zimbardo, 2007). People continue to talk about "youth and drugs" while more and more adults use drugs more intensively, and this leads to more negative consequences that political decisions facilitate access to the most commonly used drugs while stigmatizing others (Saiz, 2008) and using basic mechanisms of Culture of Control (Garland, 2005).

This is the future: more and more isolated uses to justify socialization, causing emotional discomfort in social welfare. It becomes more and more complex in form and more and more fundamental in society. Short-term expectations and mistakes, medium- and long-term problems and consequences. It doesn't look like a very good future, and we hope these humble writers are wrong.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, X.X. and Y.Y.; methodology, X.X.; software, X.X.; validation, X.X., Y.Y. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, X.X.; investigation, X.X.; resources, X.X.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, X.X.; writing—review and editing, X.X.; visualization, X.X.; supervision, X.X.; project administration, X.X.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the UCM for their support and help; Madri+d for the chance of making this activity into “La Semana de la Ciencia” in comunidad de Madrid; finally, Antonio Jesús Molina would like to give special thanks to Editorial Terra Ignota.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Asociación Americana de Psiquiatría/APA. (2013). Manual diagnóstico y estadístico de los trastornos mentales (5ª ed.).

- Asociación Proyecto Hombre. (2018). Observatorio Proyecto Hombre sobre el perfil del drogodependiente (Observatory Proyecto Hombre about the Pprofile of the Ddrug Uuser). Madrid: APH. Recuperado de: Retrieved from https://proyectohombre.es/informe-observatorio/.

- Aveiga, V., Ostaiza, J., Macías, X., y Macías, M. (2018): “Uso de la tecnología: entretenimiento o adicción”, Revista Caribeña de Ciencias Sociales (agosto 2018). Recuperado de: https://www.eumed.net/rev/caribe/2018/08/tecnologia-entretenimiento-adiccion.html //hdl.handle.net/20.500.11763/caribe1808tecnologia-entretenimiento-adiccion.

- Banks, M. L., Olson, M. E., & Janda, K. D. (2018). Immunopharmacotherapies for Treating Opioid Use Disorder. Trends in pharmacological sciences, 39(11), 908–911. [CrossRef]

- Baptista-Leite, R., (2018). The road towards the responsible and safe legalization of cannabis use in Portugal. Acta Medica Portuguesa, 31(2):115-125.

- Becoña, E. (2007). Bases psicológicas de la prevención del consumo de drogas. Papeles del Psicólogo, 28(1), 11-20.

- Becoña Iglesias, E. (1999). Bases teóricas que sustentan los programas de prevención de drogas. Madrid: Plan Nacional sobre drogas.

- Benoit, T. y Jauffret-Roustide, M. (2016)., Improving the management of violence experienced by women who use psychoactive substances. Consultation of professionals in September and October 2015 in four European cities: Paris, Rome, Madrid and Lisbon. Estrasburgo: Consejo de Europa/Instituto Pompidou.

- Beranuy, M. & Carbonell, X. (2010). Entre marcianitos y avatares: adicción y factores de riesgo para la juventud en un mundo digital. Revista de eEstudios de jJuventud, 88 (2010), pp. 131-145.

- Bertran, E., & Chamarro, A. (2016). Videojugadores del League of Legends : El papel de la pasión en el uso abusivo y en el rendimiento [Video gamers of League of Legends: The role of passion in abusive use and in performance]. Adicciones, 28(1), 28–34. [CrossRef]

- Bird, C.E. y Rieker, P.P. (2008). Gender and Health: The Effect of Constrained Choices and Social Policies. Nueva York: Cambridge University Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979) The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.Campos, R. (1997) Alcoholismo, medicina y sociedad en España. Madrid: CSIC.

- Bumbarger, B. K., & Campbell, E. M. (2012). A state agency-university partnership for translational research and the dissemination of evidence-based prevention and intervention. Administration and policy in mental health, 39(4), 268–277. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.C. (2002) Health consequences of intimate partner violence. The Lancet, 359(9314), 1331 – 1336.

- Carbonell, X. (2020). Digitalidad y adicción: experiencias y reflexiones. Revista Española de Drogodependencias, 45(4), 9–13.

- Castaños, M. (2007). Intervención en drogodependencias con enfoque de género. Colección Salud 10. Madrid: Instituto de la mujer.

- Chóliz, M., Echeburúa, E. y Ferre, F., (2017). Screening Tools for Technological Addictions: A Proposal for the Strategy of Mental Health. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 15(2), 423–433. [CrossRef]

- Cole, E.R. (2009) Intersectionality and research in psychology. American Psychology, 64, :170–180.

- Comas, D. (1999). «Adicción a sustancias psicoactivas y exclusión social», en Tezanos, J.F. (1999) Tendencias de desigualdad y exclusión social en la sociedad española. Madrid: Sistema.

- Comas, D. (20086). .El estado de salud de la juventud. Madrid, Instituto de la Juventud.

- Comunidades Terapéuticas en España: situación actual y propuesta fun- cional. Madrid: Fundación Atenea.

- Comisión Interministerial (1975) «Memoria del gGrupo de tTrabajo», Revista de sSanidad e hHigiene pPública, número especial, mayo-junio.

- Covington, S. S. (2008). Women and addiction: a trauma-informed approach. Journal of psychoactive drugs, 5,377–385. [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K.W. (1995) The intersection of race and gender. En: Crenshaw KW, Gotanda N, Peller G, Thomas K, editors. Critical Race Theory: the Key Writings that Formed the Movement. The New York Press; New York, NY: 1995. pp. 357–383.

- Damasio, A. (1994). El error de Descartes: Emoción, Razón, y el Cerebro Humano. Ed. Putnam.

- Deacon B. J. (2013). The Bbiomedical Mmodel of Mmental Ddisorder: a Ccritical Aanalysis of its Vvalidity, Uutility, and Eeffects on Ppsychotherapy Rresearch. Clinical psychology review, 33(7), 846–861. [CrossRef]

- Echeburúa, E. (1999). ¿Adicciones… sin drogas? Las nuevas adicciones (juego, sexo, comida, compras, trabajo, Internet). Bilbao: Desclée de Brouwer.

- Echeburúa, E. y Requesens, A. (2012). Adicción a las redes sociales y nuevas tecnologías en niños y adolescentes: Guía para educadores. Ed. Pirámidel.

- Earnshaw, V.A.; Bogart, L.M.; Dovidio, J.F. y Williams, D.R. (2013) Stigma and racial/ethnic HIV disparities: moving forward. American Psychology, ; 68, :225–236.

- Edwards, G. y Arif, A. (1981) Los problemas de la droga en el contexto sociocultu ral. Una base para la formulación de políticas y la planificación de programas. Ginebra: OMS.

- EMCDDA/Observatorio Europeo de las Drogas y las Toxicomanías (2017). Respuestas sanitarias y sociales a los problemas relacionados con las drogas: una guía europea. Luxemburgo: Oficina de Publicaciones de la Unión Europea.

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction and Europol (2024), EU Drug Markets Analysis: Key insights for policy and practice, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

- Escohotado, A. (2002). Aprendiendo de las drogas. Usos y abusos, prejuicios y desafíos. Madrid: Editorial Anagrama.

- Elster, J. (2001). Sobre las pasiones: emoción, adicción y conducta humana. Barcelona : Paidós Ibérica. ISBN 84-493-1097-0.

- Elzo, J.; Comas, D.; Salazar, L.; Vielva, T., y Laespada, T. (2000) Las culturas de las drogas en los jóvenes. Vitoria: Gobierno Vasco.

- Fernández-Serrano, M. J., Pérez-García, M., Perales, J. C. y VerdejoGarcía, A. (2010). Prevalence of executive dysfunction in cocaine, heroin and alcohol users enrolled in therapeutic communities. European Journal of Pharmacology, 626, 104-112. [CrossRef]

- Freixa, F. (2000) «Percepción crítica del movimiento asociativo en alcoholismo (1950- 1999)", Revista eEspañola de dDrogodependencias, 25(2).

- Gamella, J.F. y Martín, E. (1994) «Las rentas del Anfión: El monopolio español del opio en filipinas (1844-1898) y su rechazo por la administración americana», Revista de Indias, 194.

- García del Castillo, J. A., (2013). ADICCIONES TECNOLÓGICAS: EL AUGE DE LAS REDES SOCIALES. Salud y drogas, 13(1), 5-13.

- Garland, D. (2005). La cCultural del cControl. Barcelona: Ed. Gedisa.

- Gee, J.P. An Introduction to Discourse Analysis, 4th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014.

- Wodak, R. What Critical Discourse Analysis is about-a summary of its history, important concepts and its developments. In Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis; Wodak, R., Meyer, M., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2001; pp. 1–13.

- Fairclough, N.; Wodak, R. Critical Discourse Analysis. In Discourse Studies: A Multidisciplinary Introduction; van Dijk, T., Ed.; Sage: London, UK, 1997; Volume 2, pp. 258–284.

- Van Dijk, T.A. Critical Discourse Analysis. In The Handbook of Discourse Analysis; Schiffrin, D., Tannen, D., Hamilton, H.E., Eds.; Blackwell: Maiden, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 352–371.

- Rogers, R. An Introduction to Critical Discourse Analysis in Education; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: London, UK, 2004.

- Amoussou, F.; Allagbe, A.A. Principles, Theories and Approaches to Critical Discourse Analysis. Int. J. Stud. Engl. Lang. Lit. 2018, 6, 11–18.

- Bourn, D. Understanding Global Skills for 21st Century Professions; Palgrave: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar].

- Godínez, C., & Ramírez, B., (2014). La contribución de los Cannabinoides al tratamiento del dolor. Archivos de Medicina Familiar, 16 (4), 83-88.

- Goldberg, I. (1996). Internet addiction disorder. Recuperado de http://www.cog.brown.edu/brochures/people/duchon/humor/internet.addiction.html.

- Gracia, M., Vigo, M., Fernández, J., Marcó, M. (2002). Problemas conductuales relacionados con el uso de Internet: Un estudio exploratorio. Anales de Psicología. nº18 (2), pp. 273-292.

- Gurung, R.A.R. (2010). Health Psychology: A Cultural Approach. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation,20 (1), 122-122.

- Gutiérrez Resa, A. (2007). Contextualización de las drogas en España. En Drogodependencias y trabajo social / coord. por Antonio Gutiérrez Resa, Javier Martín. ISBN 978-84-96062-98-6, págs. 17-51.

- Hall, W. (2014). What has Rresearch over the Ppast two Ddecades Rrevealed about the Aadverse Hhealth Eeffects of Rrecreational Ccannabis Uuse? Addiction, 110, 19–35. [CrossRef]

- Hall, W., Carter, A., & Forlini, C. (2015). The brain disease model of addiction: is it supported by the evidence and has it delivered on its promises?. The lancet. Psychiatry, 2(1), 105–110. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, G. (2018). La perspectiva de género en los programas y servicios de drogodependencia. Revista Infonova, (35), 35-49.

- Harris, M. (1999). 1999. Theories of Cculture in Ppostmodern Ttimes. Walnut Creek: Altamira Press.

- Hasin, D. S., Sarvet, A. L., Cerda, M., Keyes, K. M., Stohl, M., Galea, S., & Wall, M. M., (2017). US Adult Illicit Cannabis Use, Cannabis Use Disorder, and Medical Marijuana Laws: 1991-1992 to 2012-2013. JAMA Psychiatry, 74, 579-588.

- Hatzenbuehler, M.L., Phelan, J.C. y Link, B.C. (2013). Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. American Journal of Public Health,;103,: 813–821.

- Herrera, M. y Ayuso, L. (2009). Las asociaciones sociales, una realidad a la búsqueda de conceptuación y visualización. Revista eEspañola de iInvestigaciones sSociológicas, nº 126, pp. 39-70.

- Hirschman, A. (1991) Retórica de la intransigencia. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

- Inciardi, J. (2000) The drug Llegalization Ddebate. Londres: SAGE.

- Jenkins, R. (1996) Social identity. Londres: Ed. Routledge.

- Kendler, K.S.; Bulik, C.M.; Silberg, J., Hettema, J.M.; Myers, J. y Prescott, C.A. (2000) Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance use disorders in women: an epidemiological and cotwin control analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry; 57, :953–959.

- Ko, G., Bober, S., Mindra, S.,& Moreau, J., (2016). Medical Cannabis: the Canadian perspective. Journal of Pain Re-search, 9, 735-744.

- Korf, D. J., O'Gorman, A. & Werse, B. (2017). The European Society for Social Drug Research: A reflection on research trends over time. Drugs: Education, Prevention & Policy, 24(4), 321-323.

- Korstanje, M. (2008). Viajando: una aproximación filosófica. Buenos Aires: Ed. Universidad de Palermo.

- Kulesza, M., Matsuda, M., Ramirez, J. J., Werntz, A. J., Teachman, B. A. y Lindgren, K. P. (2016). Towards greater understanding of addiction stigma: Intersectionality with race/ethnicity and gender. Drug and alcohol dependence, 169, 85–91. [CrossRef]

- Laespada, T. e Iraurgi, I. (2009) Reducción de daños: lo aprendido de la heroína. Deusto: Ed. Universidad de Deusto.

- Martínez, P. (2018). Uso de drogas, adicciones y violencia, desde perspectiva de género. Revista Infonova, (35), 23-34.

-

Molina-Fernández, A. (2024). El futuro de las drogas. Editorial Terra Ignota. ISBN 978-84-127558-7-9.

- Molina-Fernández, A. (2024). El futuro de las drogas. Editorial Terra Ignota. ISBN 978-84-127558-7-9.

- Molina-Fernández, A. (2023). La recuperación de adicciones en Europa: teoría, modelo y métodos. De la dependencia de las sustancias a la recuperación de las personas. Editorial Aula Magna, McGraw-Hill Interamericana de España S.L.

- Molina-Fernández, A., Medrano Chapinal, P. y Comellas Sanz, P. (2022a). Consecuencias psicosociales de la regulación del cannabis: un estudio cualitativo. Health and Addictions / Salud y Drogas, 22(2), 10-21. [CrossRef]

- Molina-Fernández, A.J., Feo-Serrato. M.L. y Serradilla-Sánchez, P. (2022b). Impact evaluation of European strategy on Spanish National Plan on Drugs and the role of civil society. Adicciones. [CrossRef]

- Molina, A., Saiz, J., Gil, F. & Cuenca, M. L. (2021). Models of Recovery: Influence of Psychosocial Factors on Substance Use Recovery. Journal of Substance Use. [CrossRef]

- Molina, A., Saiz, J., Gil, F., Cuenca, M. L. y Goldsby, T. (2020). Psychosocial Intervention in European Addictive Behaviour Recovery Programmes: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare, 8(3), 268. [CrossRef]

- Molina Fernández, A.J., Gil Rodríguez, F., & Cuenca Montesinos, M. L. (2018). Can Neuroscience be a Faustian bargain? Psychosocial factors in recovery of addictive behaviours. International Journal of Psychology and Neuroscience, 4(2), 67-75. [CrossRef]

- Molina Fernández, A., Saiz Galdós, J., Cuenca Montesino, M. L., Gil Rodríguez, F., Mena García, B. y Rodríguez Hansen, G. (2022). Los programas de recuperación en la intervención de los trastornos por abusos de sustancias: buenas prácticas europeas. Revista Española de Drogodependencias, 47(1), 33-46. [CrossRef]

- Molina, A., Saiz, J., Gil, F. & Cuenca, M. L. (2021). Models of Recovery: Iinfluence of Ppsychosocial Ffactors on Ssubstance Uuse Rrecovery. Journal of Substance Use. [CrossRef]

- Molina, A., Saiz, J., Gil, F., Cuenca, M. L. y Goldsby, T. (2020). Psychosocial Intervention in European Addictive Behaviour Recovery Programmes: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare, 8(3), 268. [CrossRef]

- Moradiellos, E. (2009). Las caras de Clío: una introducción a la Historia. Madrid: Ed. Siglo XXI. ISBN 9788432314025.

- NIDA (1997) Preventing Drug Use Among Children and Adolescents: A Research-Based Guide. Bethesda: NIH.

- NIDA (2023). Infofacts. Bethesda: NIH. En https://nida.nih.gov/es/areas-de-investigacion/los-opioides.

- Observatorio Español sobre Drogas y Toxicomanías/OEDT (2022) Encuesta ESTUDES 2020-2021. Madrid: PNSD.

- Observatorio Español sobre Drogas y Toxicomanías/OEDT (2023) Encuesta EDADES 2021-2022. Madrid: PNSD.

- Oughorlian, J.M. (1977) La persona del toxicómano. Barcelona: Herder.

- Pons, X. (2006). Materiales para la intervención social y educativa ante el consumo de drogas. Alicante: Editorial Club Universitario.

- Romaní, O. (1983) A tumba abierta. Barcelona: Anagrama.

- Rosenthal, L. (2016). Incorporating intersectionality into psychology: an opportunity to promote social justice and equity. American Psychology,; 71, :474–485.

- Saiz, J. (2008). El estigma de la cocaína. Revista Española de Sociología, 10, 97-114.

- Secades Villa, R. y Fernández Hermida, J.R. (2006). Tratamiento cognitivo- conductual. En G. Cervera, J.C. Valderrama, J.C. Pérez ce los Cobos, G. Rubio y L. Sanz, Manual SET de Trastornos Adictivos. Madrid: Editorial Médica Panamericana.Singer, M. (2009). Introduction to syndemics : a critical systems approach to public and community health. Ed. Jossey-Bass. ISBN 978-0-470-48298-8. OCLC 428819497.

- Smith, DE. (2012). The process addictions and the new ASAM definition of addiction. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 44(1):1-4. [CrossRef]

- Solé Puig, J.R. (1981). «Drogas y contracultura», en Freixa, F. y Soler Insa, P.A. (1981) Toxicomanías. Un enfoque interdisciplinario. Barcelona: Fontanella.

- Sykes, N. and Thorns, A. The use of opioids and sedatives at the end of life. The Lancet Oncology, Volume 4, Issue 5, 2003, Pages 312-318, ISSN 1470-2045. [CrossRef]

- Unión Nacional de Asociaciones de Drogodependencias. (2019). Profile and Ttrends of Aaddictive Bbehaviours. Madrid: PNSD. https://unad.org/noticias/2416/unad/presenta/el/perfil/y/las/tendencias/de/las/adicciones.

- United Nations Office for Drug and Crime/UNODC. (2013) The Challenge of New Psychoactive Substances. UNODC Global Smart Programme. Oficina de las Naciones Unidas contra las drogas y el Delito. Viena.

- UNODC. (2020) Informe mundial sobre drogas. Oficina de las Naciones Unidas contra las drogas y el Delito. Viena.

- Vega, A. (1992). Modelos interpretativos de la problemática de las drogas. Revista Española de Drogodependencias, 17, 221-232.

- Torres, M.A y cols. (2009) Historia de las adicciones en la España contemporánea. Madrid: Sociodrogalcohol.

- Uris, P. (1995) Alucinema, las drogas y el cine. Barcelona: Royal Books.

- Vega, A. (1992). Modelos interpretativos de la problemática de las drogas. Revista española de drogodependencias, 17, 221-232.

- Velasco, H. (2003). Hablar y pensar: tareas culturales, UNED.

- Verdejo-García, A., y Pérez-García, M. (2007). Ecological assessment of executive functions in substance dependent individuals. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 90, 48-55.

- Volkow, N. D., & Koob, G. (2015). Brain disease model of addiction: why is it so controversial?. The lancet. Psychiatry, 2(8), 677–679. [CrossRef]

- Wasson, R.G.; Wasson, V. (1957) Mushrooms, Rusia and History. New York: Pantehon Books.

- World Health Organization (WHO) y United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) (2020). International Standards for the Treatment of Drug Use Disorders. Oficina de las Naciones Unidas contra las drogas y el Delito. Viena.

- Zimbardo, P. (2007). El efecto Lucifer. Nueva York: Random House.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).