Submitted:

09 May 2025

Posted:

11 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Black-Bounce-Reissner–Nordström Spacetime

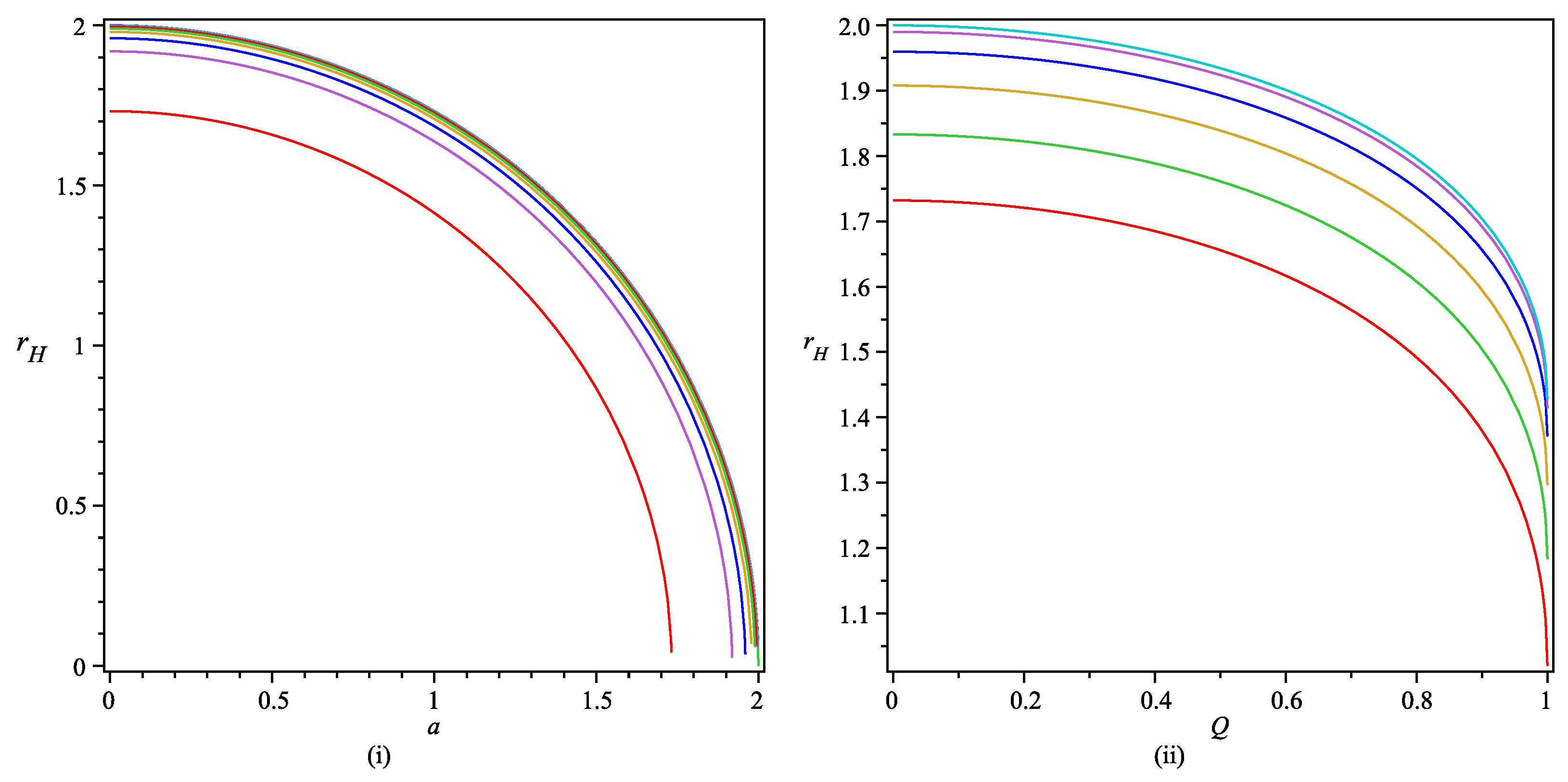

2.1. Event Horizon of Black-Bounce-RNBH Spacetime

3. First Integrals of Geodesic Equations

3.1. Effective Potential for Black-Bounce-RNBH Spacetime

4. Newtonian Radial Acceleration

- To study the effect of the gravitational field of the black-bounce-RNBH spacetime on the orbiting neutral test particle one may be interested to look for the possible distance from where a neutral test particle bounces back as happened in standard RNBH [20]. To derive expression for this distance,one will have to look for the real root of equation . After solving such relation for black-bounce-RNBH, the expression for such distance comes out as,

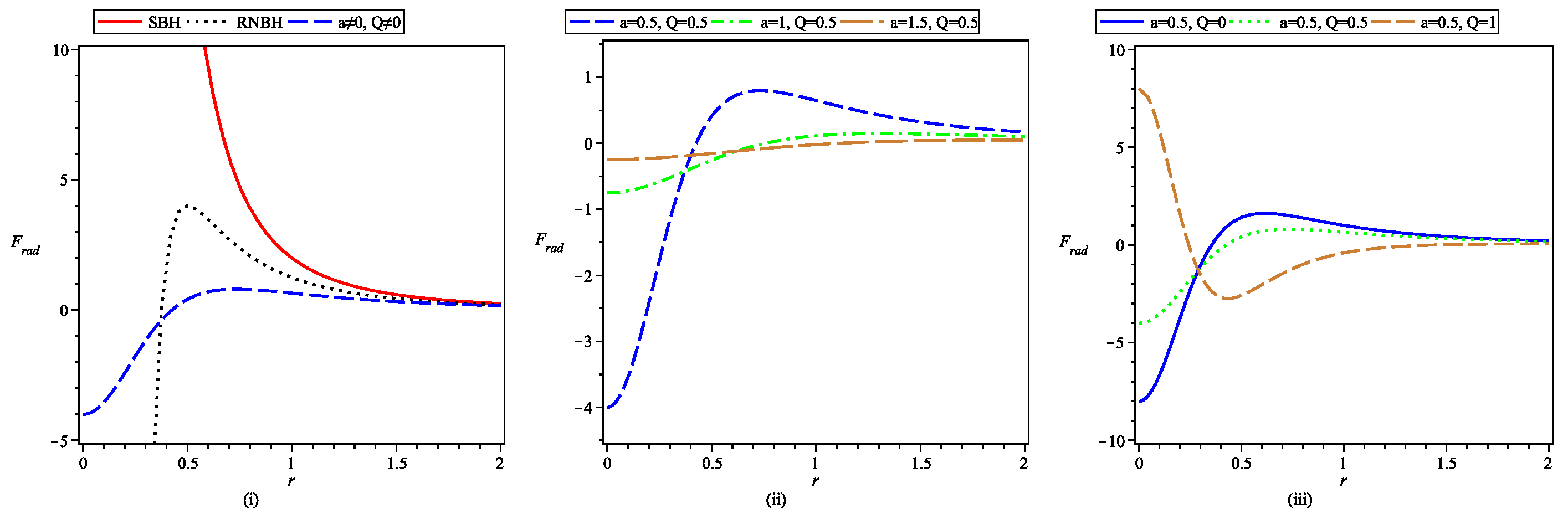

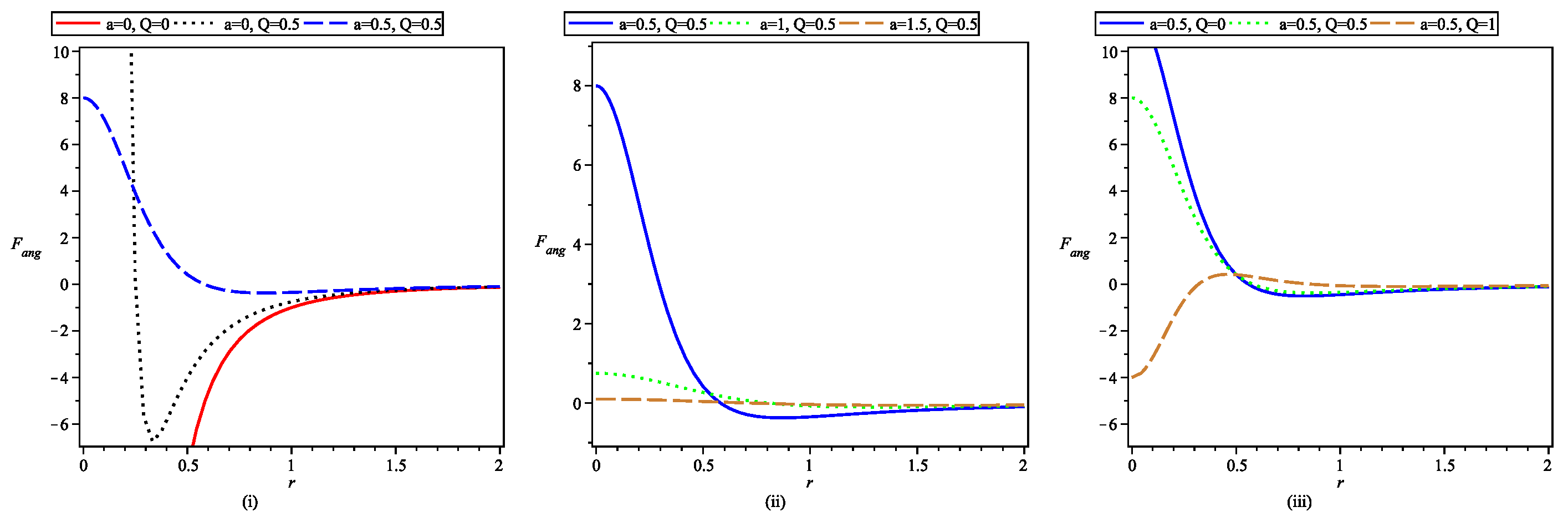

4.1. Analysis of Tidal Forces Acting in Black-Bounce-RNBH Spacetime

5. Revisiting the Geodesic Deviation Equations and Their Solutions

6. Conclusions

- (i)

- The presence or absence of horizons defines whether it’s a black bounce (with event horizon) or a wormhole-like structure (without horizon). The event horizon is present only for moderate charge Q and bounce parameter a satisfying the conditions and .

- (ii)

- The expression for Newtonian radial acceleration is obtained for black-bounce-RNBH spacetime and further the tidal forces in radial and angular directions are analyzed in detail.

- (iii)

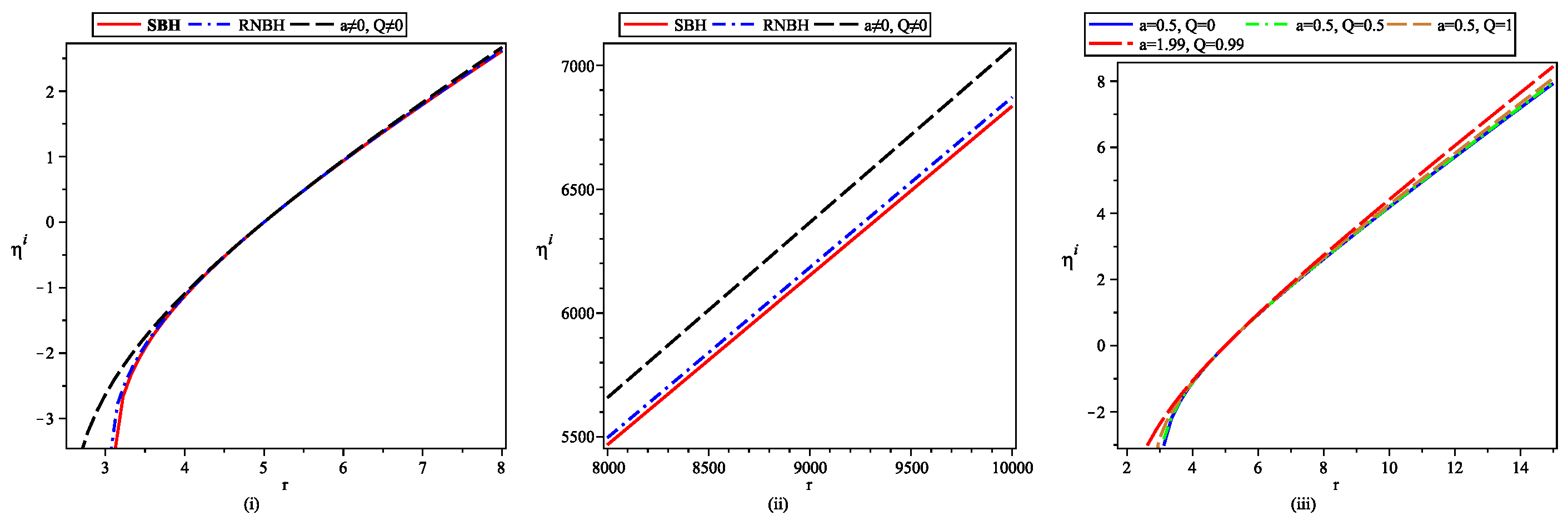

- Comparative plots for tidal forces show the absence of infinite radial stretching and infinite angular compression incase of black-bounce-RNBH spacetime for any object approaching central singularity. As particle reaches near central region, now its not turned apart by infinite forces as incase of SBH but the magnitude of tidal forces reaches their respective maxima and decrease afterwards.

- (iv)

- The generalised set up of geodesic deviation equations around black-bounce-RNBH spacetime are derived and solved analytically in terms of elliptical integrals.

- (v)

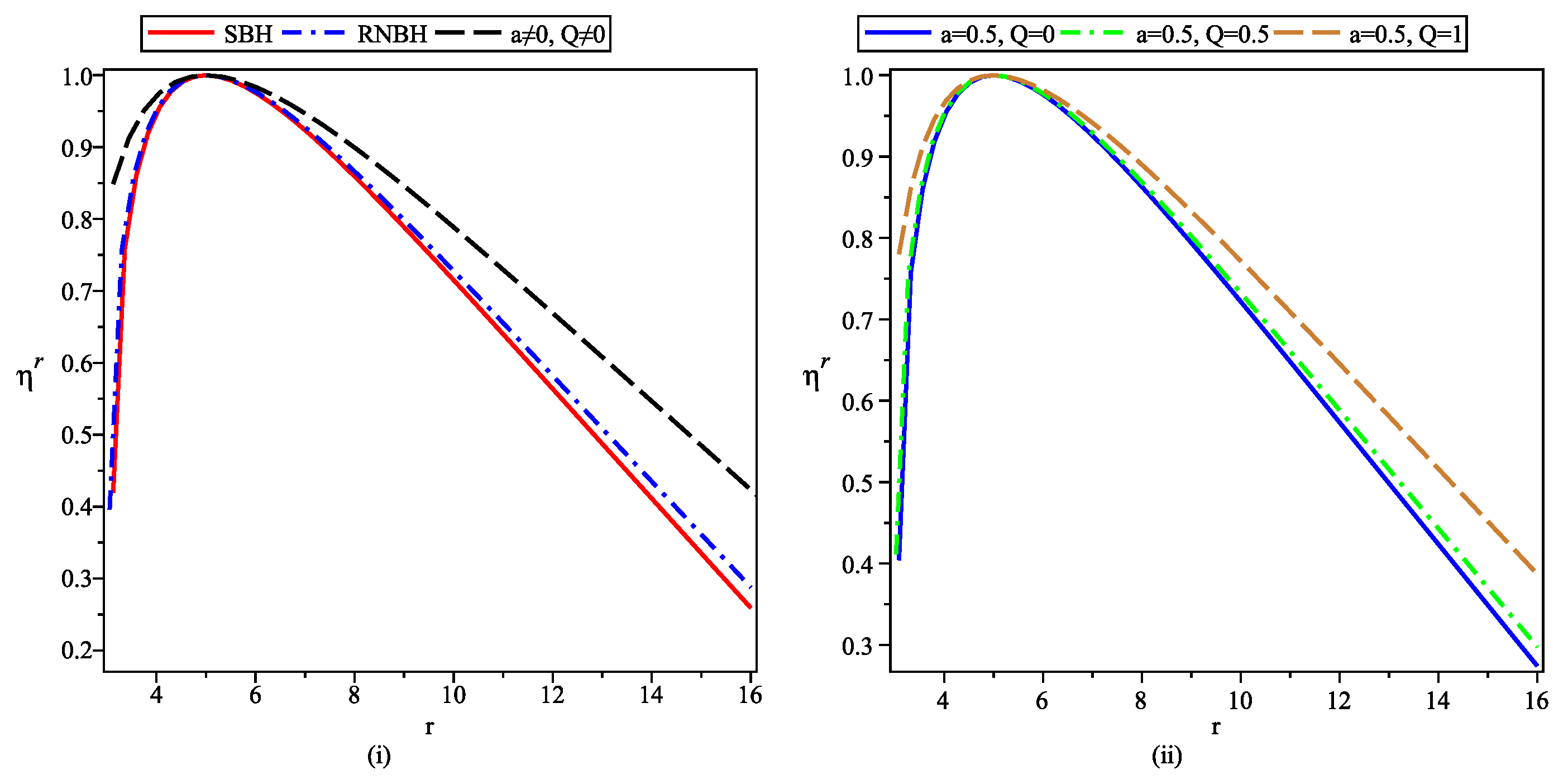

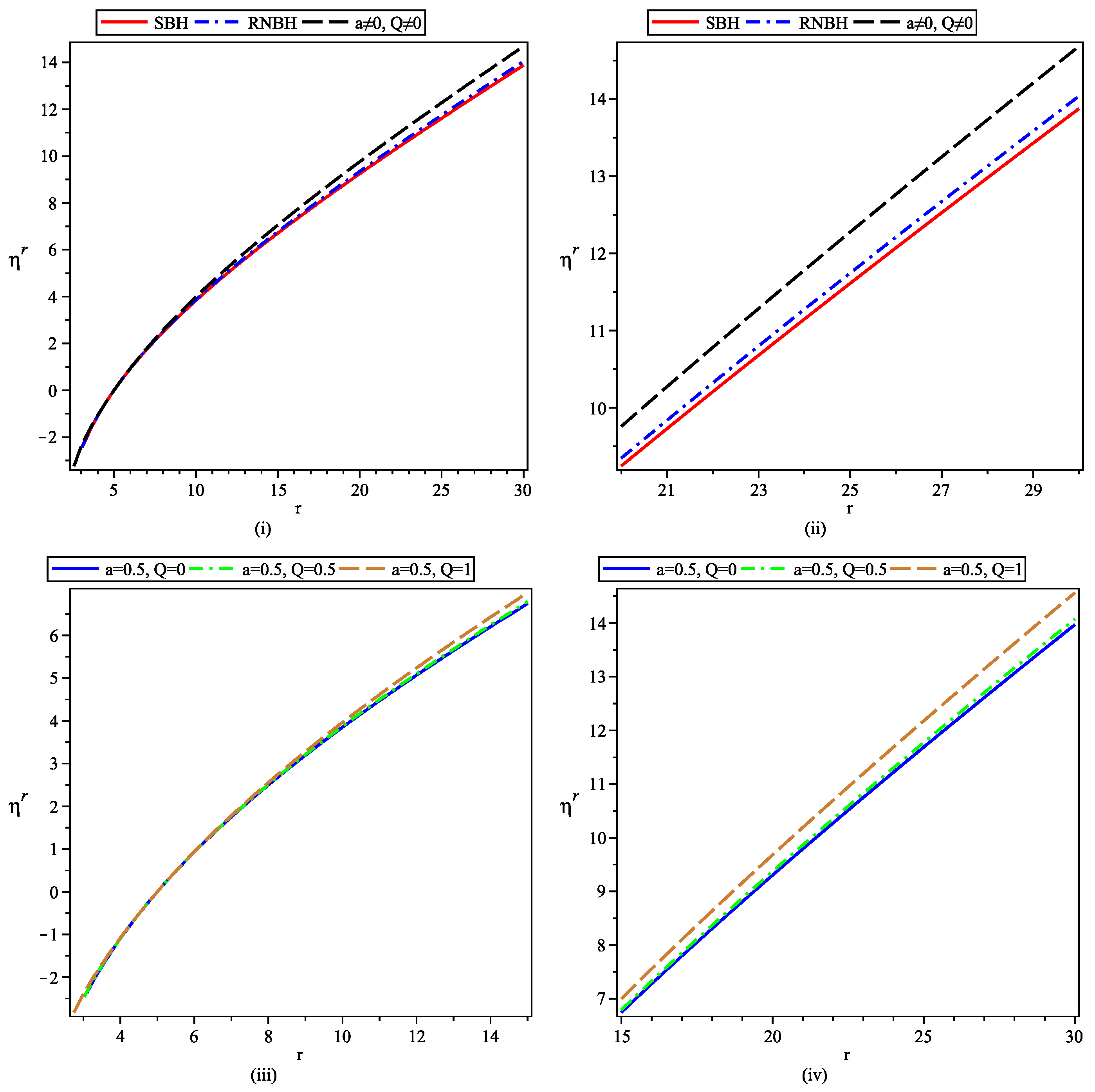

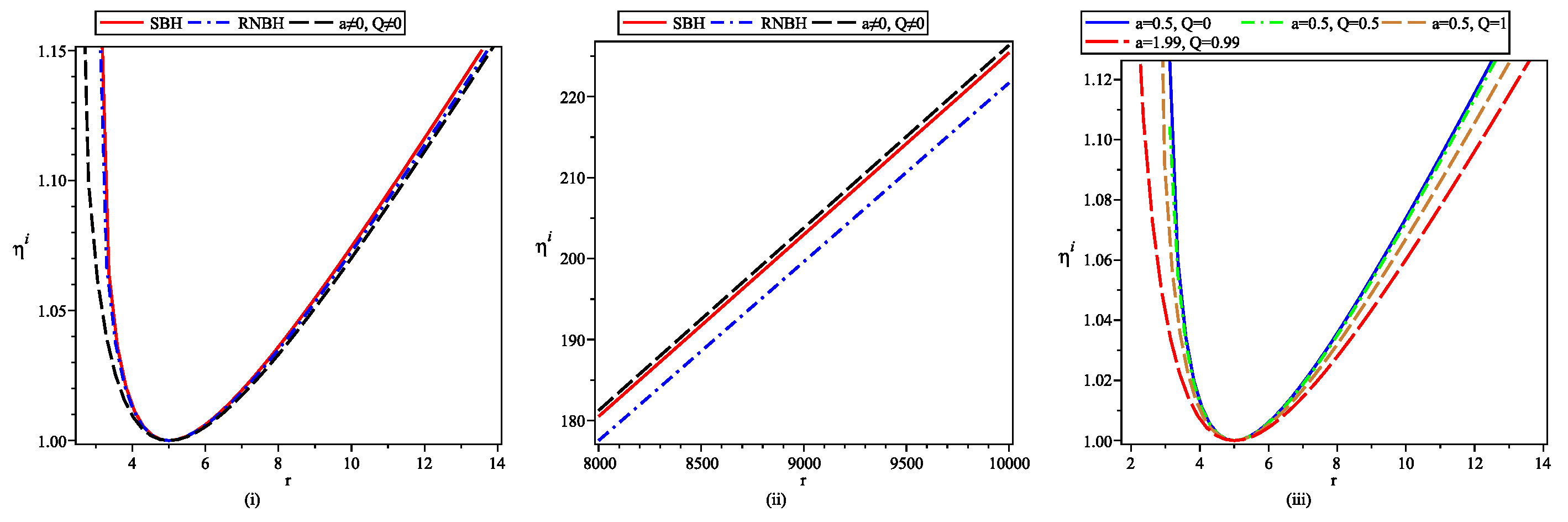

- The geodesic deviation equations are also solved numerically using two initial conditions, first corresponding to the particle starting from rest and having fixed energy while second corresponding to an exploding particle with varying energy value along its path. The numerical plots are shown in Figure (4), Figure (5), Figure (6) and Figure (7). If one observes that under IC-I, radial divergence between neighboring geodesics starts at a fixed r and it increases for far distances from center, while near central region the behaviour is opposite. The strength of relative separation reduces for black-bounce-RNBH spacetime in comparison to SBH and RNBH. In contrast, the initially diverging geodesics keep on diverging in radial as well as angular directions under IC-II.

- (vi)

-

In angular direction, the initially converging geodesics for SBH become diverging under IC-I. Now if one observes the far field behavior, the non-zero and increasing values of both Q and a result in larger magnitude of separation vector, thus helping the relative divergence of geodesics. Similar pattern is seen under IC-II in angular direction.This work presented in this article is important to have a better understanding of the gravitational field of black-bounce-RNBH spacetime. It can be extended further to discuss the tidal force transition through the bounce can be studied in order to understand the gravitating effects of a wormhole-like or bounce passage to another region.

References

- Hartle, J.B. Gravity: An Introduction to Einstein’s General Relativity; Pearson Education Inc.: Singapore, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wald, R.M. General Relativity; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Poisson, E. A Relativist’s Toolkit: The Mathematics of Black-Hole Mechanics; Cambridge University Press: London, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardeen, J. Non-singular general-relativistic gravitational collapse. In Proceedings of the GR5, Tbilisi, USSR, 1968; Vol. 42, p. 174.

- Simpson, A.; Visser, M.; Cosmol, J. Astropart. Phys. 2019, 2, 042. [CrossRef]

- Cañate, P. Black bounces as magnetically charged phantom regular black holes in Einstein-nonlinear electrodynamics gravity coupled to a self-interacting scalar field. Phys. Rev. D 2022, p. 024031.

- Bokuli´c, A.; Smoli´c, I.; Juri´c, T. Constraints on singularity resolution by nonlinear electrodynamics. Phys. Rev. D 2022, p. 064020.

- Franzin, E.; Liberati, S.; Mazza, J.; Simpson, A.; Visser, M. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2021, 7.

- Mazza, J.; Franzin, E.; Liberati, S. A novel family of rotating black hole mimickers. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, F.; Rodrigues, M.; Silva, M.; Simpson, A.; Visser, M. Novel black-bounce spacetimes: Wormholes, regularity, energy conditions, and causal structure. Phys. Rev. D 2021, p. 084052.

- Xu, Z.and Tang, M. Rotating spacetime: Black-bounces and quantum deformed black hole. Eur. Phys. J. C 2021, p. 863.

- Churilova, M.S. Quasinormal modes of the Dirac field in the consistent 4D Einstein–Gauss–Bonnet gravity. Phys. Dark Univ. 2021, 31, 100748, [arXiv:gr-qc/2004.00513]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xie, Y. Gravitational lensing by a black-bounce-Reissner–Nordström spacetime. Eur. Phys. J. C 2022, 82, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzin, E.; Liberati, S.; Mazza, J.; Simpson, A.; Visser, M. Charged black-bounce spacetimes. JCAP 2021, 07, 036, [arXiv:gr-qc/2104.11376]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Miao, Y.G. Charged black-bounce spacetimes: Photon rings, shadows and observational appearances. Nucl. Phys. B 2022, 983, 115938, [arXiv:gr-qc/2112.01747]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murodov, S.; Badalov, K.; Rayimbaev, J.; Ahmedov, B.; Stuchlík, Z. Charged Particles Orbiting Charged Black-Bounce Black Holes. Symmetry 2024, 16, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, H. J. Math. Phys. 1973, 14, 104. [CrossRef]

- Uniyal, R.; Chandrachani Devi, N.; Nandan, H.; Purohit, K.D. Geodesic Motion in Schwarzschild Spacetime Surrounded by Quintessence. Gen. Rel. Grav. 2015, 47, 16, [arXiv:gr-qc/1406.3931]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uniyal, R. Tidal forces around Schwarzschild black hole in cloud of strings and quintessence. Eur. Phys. J. C 2022, 82, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crispino, L.C.B.; Higuchi, A.; Oliveira, L.A.; de Oliveira, E.S. Tidal forces in Reissner–Nordström spacetimes. Eur. Phys. J. C 2016, 76, 168, [arXiv:gr-qc/1602.07232]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel, K.; Poisson, E. A One parameter family of time symmetric initial data for the radial infall of a particle into a Schwarzschild black hole. Phys. Rev. D 2002, 66, 084001, [gr-qc/0107104]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandeev, V.P.; Semenova, A.N. Tidal forces in Kottler spacetimes. Eur. Phys. J. C 2021, 81, 610, [arXiv:grqc/2204.13203]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, S.; Jing, J. Tidal effects of a dark matter halo around a galactic black hole*. Chin. Phys. C 2022, 46, 105104, [arXiv:gr-qc/2203.14039]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, R.M. Geodesics and Geodesic Deviation in a Stringy Charged Black Hole. Astrophys. Space Sci. 2010, 330, 107–114, [arXiv:math-ph/0708.2841]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).