Submitted:

08 May 2025

Posted:

09 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. A Brief Overview of Classical AGN Feedback

1.2. Scope of the Current Review

2. Modelling Jet Driven Feedback at Galactic Scales

2.1. Jets in Homogeneous Medium

2.2. Jets in Inhomogeneous Medium

2.2.1. Non-Relativistic Simulations

2.2.2. Relativistic Simulations

- ISM with small size clouds ( pc) could easily be cleared by the jet and result in mean radial velocities higher than the stellar velocity dispersion with moderate values of Eddington ratios (). However, sufficiently accelerating larger clouds, typical of galactic GMC[187,188,189] ( pc), would require higher Eddington ratio () for jets of power (), and hence more efficient outburst from larger mass SMBH. This implies stronger confinement of jets in ISM with larger clouds, which would be more difficult to ablate, as also confirmed in later works [175].

- The jets were found to provide a strong mechanical advantage, higher than unity (defined as the ratio of total outward momentum of clouds to the net momentum imparted by the jet). This also correlated with kinetic energy transfer to the ISM , later refined to slightly lower values by future works [175,190].

3. Summary of Key Results

3.1. Evolutionary Stages of the Jet Through an Inhomogeneous Medium

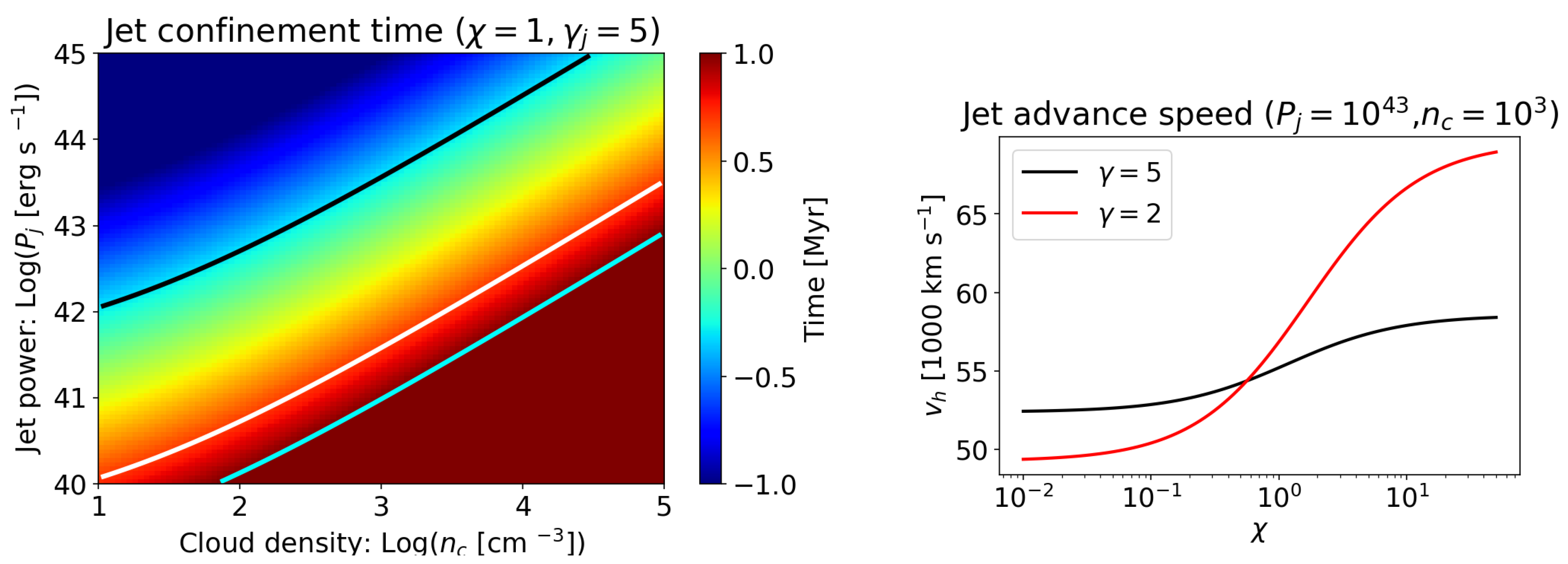

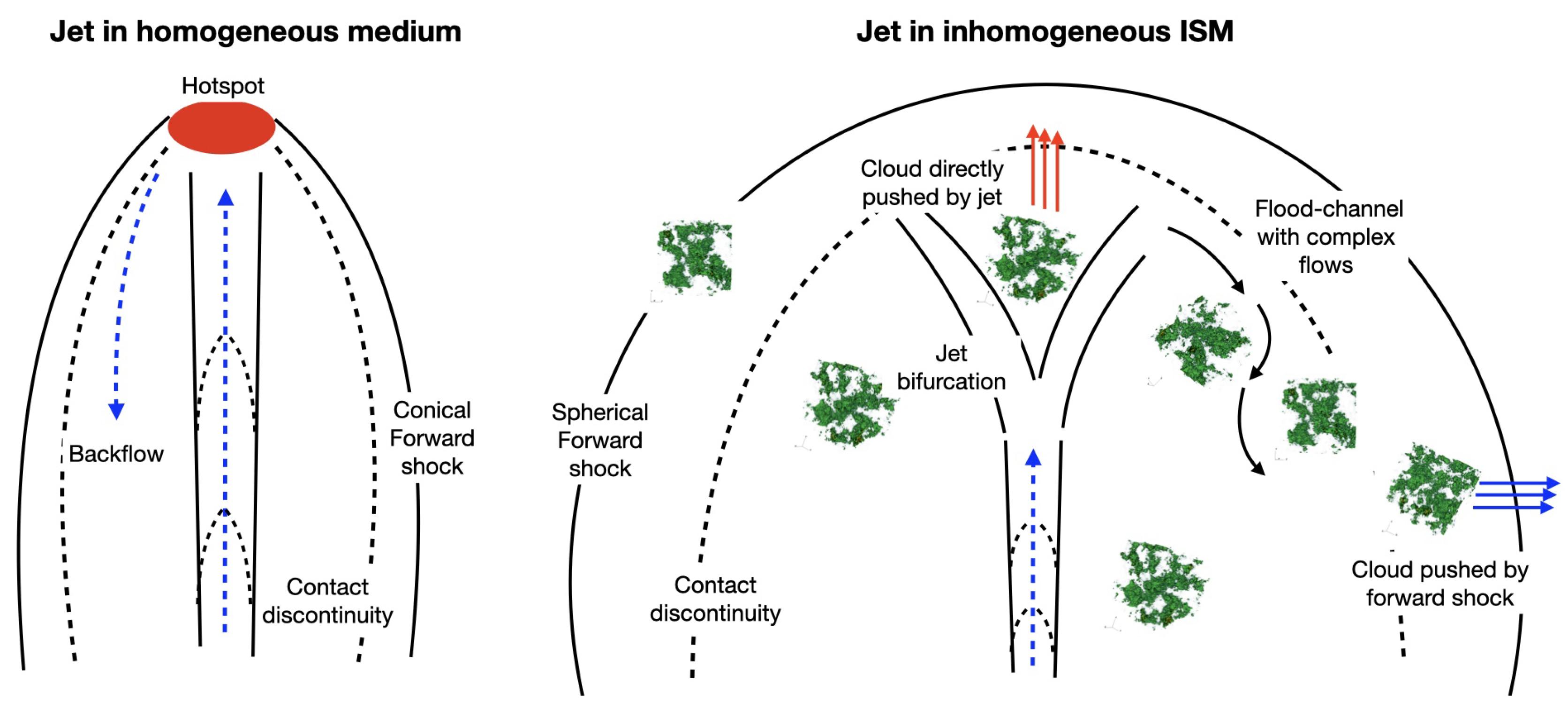

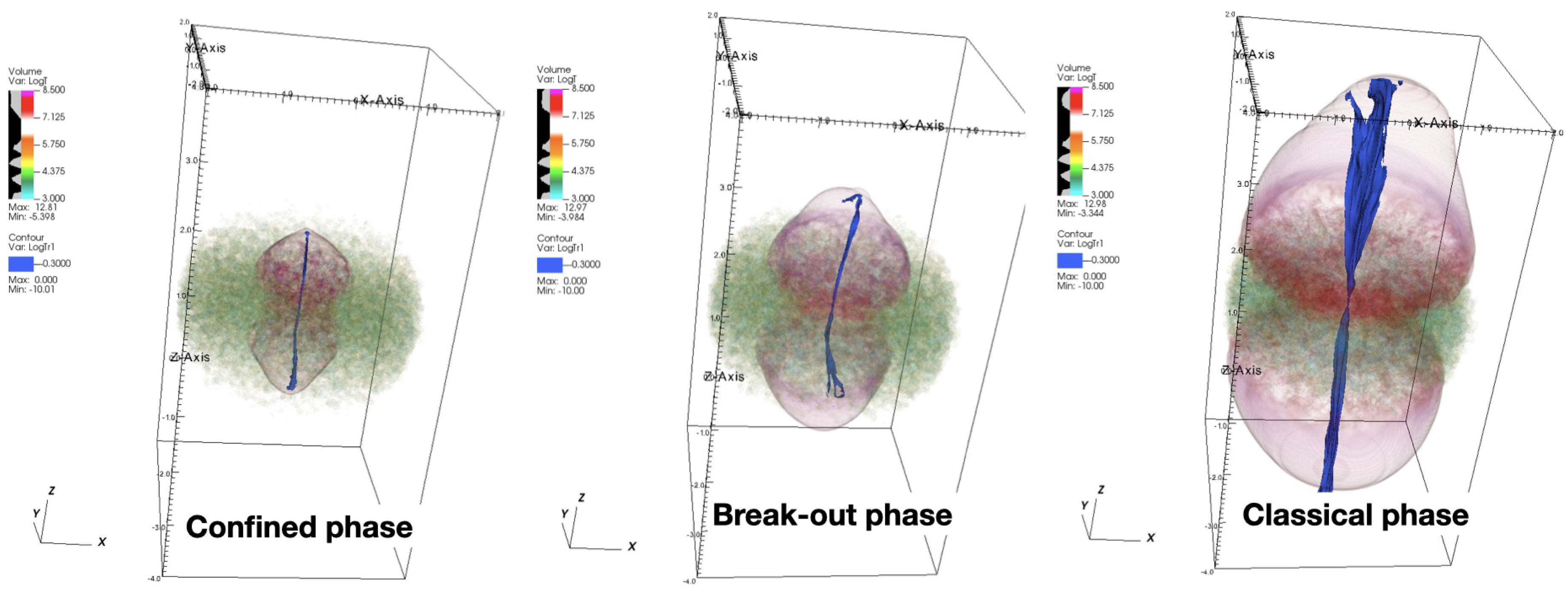

- The Confined phase: The jet remains confined within the clumpy ISM ( kpc), resulting in the formation of a flood-channel scenario (see right panel of Figure 1). The jet-plasma is diverted to low density channels through the clouds, percolating into the ISM. The jet beam’s forward progress is halted, leading to a temporary stalling of the jet-head. However, the jet’s energy is dispersed over a quasi-spherical volume as the forward shock sweeps through the ambient medium in the form a energy driven bubble. Simulations find the time of the confined phase can last from a few hundred kilo-years to a Myr, depending on the power of the jet, the density of the ambient medium and extent of the dense gas. An approximate analytical analysis of the duration of confinement is presented in Appendix A. Since these conditions can vary over wide range between different galaxies, the impact of jet and the efficiency of coupling with the ISM can have a wide variation as well.

- Jet breakout phase: The jet breaks free from the confinement of the dense ISM and the hemi-spherical bubble, to proceed onwards. During this phase the jet driven bubble can still indirectly impact the dense ISM. The bubble remains over-pressurised and eventually engulfs the ISM. This is accentuated by the drafts of backflow from the tip of the jet. This drives shocks into the clouds away from the jet axis, which can raise turbulence [169] and impact starformation over the inner few kpc of the galaxy [169,194,195]. During this phase the jet and its ensuing bubble still has significant impact on the ISM. However, as the decrease in pressure with the expansion of the bubble weakens the impact on the dynamical evolution of the dense gas.

- The classical phase: Beyond the break-out phase, the jet carves a clear path through the ISM. Subsequent energy flows have less impact on the ISM. The jet proceeds into the low density stratified homogeneous halo gas. Beyond this, the dynamics of the jet are similar to the conventional models of jet propagation into a static homogeneous medium. The dynamics of the ISM and perturbed velocity dispersion of the clouds start to decay back to the pre-jet levels [195].

- The volume filling factor of the dense gas ().

- Jet’s orientation with respect the ISM morphology, with jets inclined to a gas disk being more productive ().

- Jet power ().

- Mean density of the clouds in the ISM ().

3.2. Global Impact on the ISM

- Direct impact of jet-beam ( kpc): Clouds directly along the path of the jet are strongly impacted by the flow and eventually ablated. Such an interaction affects both the clouds as well as the jet. For large clouds (e.g., a GMC of size pc) directly along the jet-beam, which may nearly cover the jet’s width, the jet is strongly decelerated till the cloud moves away from the jet’s path or is completely disintegrated. The region of such impact is usually confined to kpc, where the jet-beam and its ensuing backflow directly interacts with the ISM. This region experiences much higher turbulent velocity dispersion and density enhancement [195] due to stronger ram pressure driven shocks. In addition, the stronger interaction in the central region also results in mass removal and formation of a cavity [169,173,195]. However, simulations that better resolve the cloud structures show that such cavities are not completely devoid of dense gas [192,196]. Strands of dense cloud cores, with a radiative shock enhanced high density outer shell remain embedded inside such cavities, that are slowly ablated by the jet driven flows [169,192].

- Indirect impact by energy bubble ( kpc): As mentioned earlier in Section 3.1, the confined jet’s energy spreads out in the form of an energy bubble sweeping through the ISM. The indirect interaction operates differently depending on the evolutionary phase of the jet (see Section 3.1). During the jet confinement phase, the forward shock sweeps through the ISM. The embedded clouds face a steady outward radial flow of the jet plasma being re-directed in lateral directions from the jet axis, through the flood-channel mechanism. This results in outward radial flows inside the ISM, away from the jet axis. In the jet breakout phase and beyond, the jet expands beyond the immediate confines along its path and the over-pressured cocoon engulfs the ISM. This is more prominent for gas disks, as shown in the right panel of Figure 3. Such indirect interactions are responsible for more large scale impact of the jet, beyond the central 1 kpc range. This raises the velocity dispersion of the gas in general all through the ISM and also shocks a larger volume of the ISM [199,200]. Inclined jets strongly confined within the ISM [163,169,176,192] are also able to process a large volume as the jet-plasma spreads beyond the decelerated jet-head and drive radial inflows through the ISM.

3.3. Impact on ISM Kinematics

3.3.1. Multi-Phase Outflow:

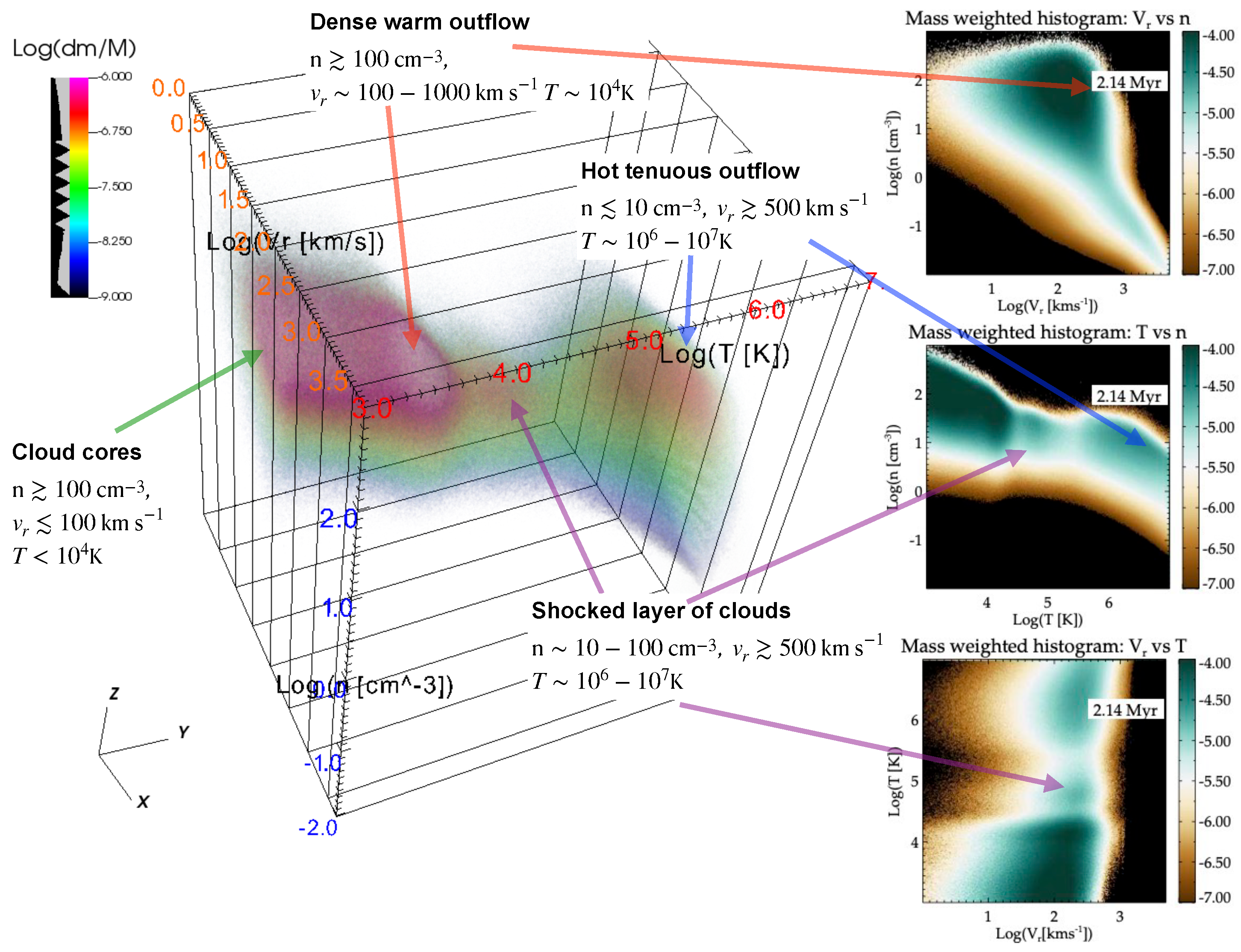

- Cloud cores: There is collection of mass at K, with high densities near the left face of the 3D figure. This corresponds to the cores of the clouds, with a temperature near the cooling floor of the simulation (K). The clouds have some positive radial velocity () which likely correspond to the turbulent bulk velocity of the clouds injected at initialisation and also mild acceleration after jet-ISM interaction.

- Dense warm outflow: There is a distinct collection of mass in Figure 4, shifted from the cloud cores, that is centred around K in temperature and extending from in velocity and density . This corresponds to dense shock heated gas that has cooled and accelerated to high velocities. This phase has the highest mass among all of the outflowing gas, and hence accounts for the dominant contributor to the kinetic energy budget of the outflows. In observational studies, this phase would correspond to the warm molecular gas [202,210,211,212] and may also proxy the cold gas outflows [204,209,213] as modelled in Mukherjee et al. [192].

- Shocked cloud layers: Beyond the dense warm phase, there is another distinct, but small, collection of mass peaking between K, and at a lower density () than the dense warm phase. The temperature range corresponds to the peak of the cooling curve. This phase belongs to either the outskirts of the clouds being shocked by the enveloping pressure bubble or shocked dense cloud-lets ablated from large clouds [169,200]. This phase accounts for the majority of the observed emission in optical lines used as diagnostics of shock ionisation such as O[II], O[III], S[II] etc. [192,200]. It should be noted that the mass represented in this phase is small compared to the dense phase. Hence, inferences of ionised gas mass from shocked gas are often lower limits to the gas mass actually contained in the ISM, but often missed due to lack of multi-wavelength coverage of the system.

- Hot tenuous outflow: The jet driven outflows pushes out the ablated gas in a tenuous hot form (, K). This gas forms a tail of the distribution extending to very low densities and high velocities. Such a hot tenuous gas is predicted to be seen in X-rays wavebands [33]. Detecting the soft X-rays from such thermal gas with sufficient spatial resolution to distinguish it from the central nucleus is challenging, owning to the contribution from the AGN, but has been tenatively confirmed in some sources [214,215].

3.3.2. Galactic Fountain:

3.3.3. Turbulent Velocity Dispersion:

3.4. Impact on Starformation Rate

4. Observational Implications

4.1. Observations of Jet-ISM Interactions

4.2. Implications for Compact and Peaked Sources (CSS/GPS/CSO)

5. Concluding Perspectives

- Are RLAGN gas rich? One of the major concerns of the role of jets on their host galaxy was whether radio loud galaxies have enough gas in the first place to be affected by jets. The traditional view has been that in the nearby universe, powerful radio jets are usually found in early type galaxies (ETG), which were considered to be gas poor. However, systematic surveys of such systems have uncovered a significant fraction ([267]) to host dense gas, with higher fractions for radio loud AGN ( [268]). A summary of the various surveys can be found in Table 4 of Tadhunter et al. [268]; also see recent the recent review Ruffa and Davis [269] for more details on molecular gas in local ETG. Interestingly, fractions of radio loud galaxies with molecular gas and the estimated masses, have also been found to increase in with redshift [270], with masses spanning . Thus, dense gas is present in a significant fraction of radio galaxies, opening up the potential for jet-driven local feedback, should jets have significant coupling with the ISM.

- Radio detected fraction of AGN? Earlier studies of AGN populations had demonstrated that the radio-detected fraction of AGN reaches up to for high mass galaxies [271,272]. This, though small, is non-negligible. More recent sensitive radio surveys [273] have extended these to lower radio luminosities and have substantially increased the fractions, to point towards more ubiquitous distribution of nuclear radio activity. Although the higher fractions correspond to radio powers an order of magnitude or more lower than considered earlier, implying weaker nature of the AGN, they nonetheless, provide credence to wide-spread presence of radio activity. Furthermore, it is important to distinguish between the traditional definition of “radio-loudness” inferred from correlations of [OIII] and 1.4 GHz radio luminosity may not often imply radio “silent”. As demonstrated in recent surveys [263,264] a significant fraction of traditional “radio-quiet” sources may harbor nuclear radio emission driven by an AGN, or a jet. They may also demonstrate jet-ISM interaction, as shown in Figure 5 [219].

- Extent of the jet’s impact: Although the apparent beam of radio jets are often found to be thin, collimated structures, the fact that they can have a wider influence, has been well demonstrated by simulations and observations, as outlined in this review. The observed size in radio wavelengths, may often under-represent the large scale impact (e.g., in 4C 31.04 [203], and several other sources in Section B) as the jets are broken into low density streams in the flood-channel phase. However, the even though such impacts may extend beyond the immediate confines of the jet, in most cases, the impact has been seen to be in the central few kpc. Though non-negligible, there needs to be better proof for more wider scale impact, to confirm/discard the predictions from simulations.

- Nature of jet’s impact: outflows, turbulence, starformation: Observed studies have strongly established the presence of jet driven outflows in the central few kpc of several sources, in line with predictions from simulations as outlined in Section 4. The outflows are coincident with broad line widths indicating turbulent motions, demonstrating the jet’s ability to affect the local gas. However, the broader long term implications for such actions in the context of galaxy evolution, especially with regards to starformation, is an open question. Although, several prominent radio loud sources are known to show deficiency in star formation rate [210,225], the ubiquitousness of such cases of jet feedback have been questioned in other recent studies that find less impact on wider scale molecular gas [266]. Even from a theoretical point of view, the theory of turbulence regulated starformation applied to large scale simulations is in its infancy. It should also be noted that any impact from a given jet/AGN feedback episode may not have an instantaneous impact on the SFR, but will have accumulated effect, as stressed in recent reviews [2]. Hence, more systematic studies of long term impact of jets in particular, and AGN in general are needed in future to answer these questions.

-

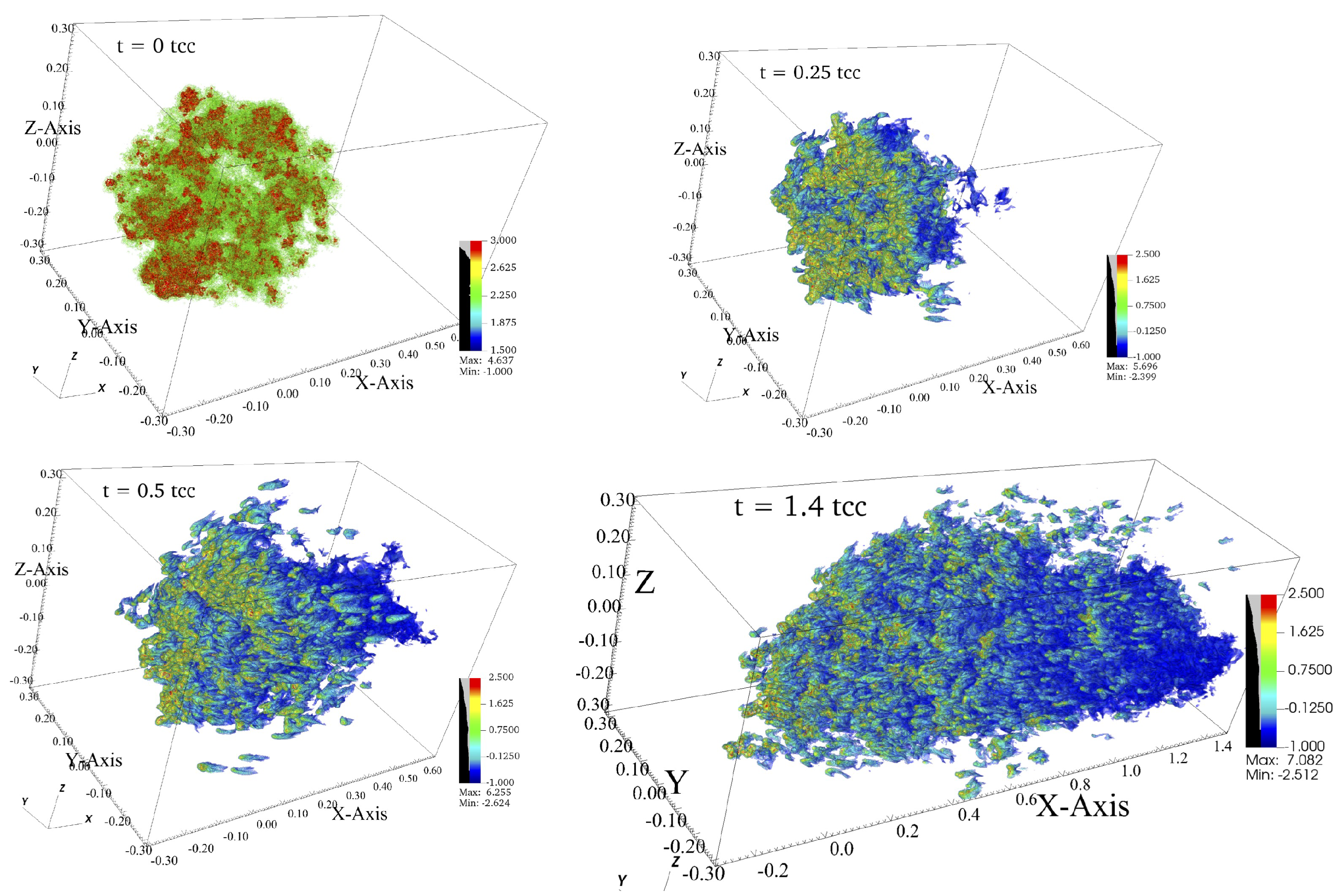

Need for theoretical improvements: As outlined in the review, recent simulations efforts have reached high levels of sophistication and realism in modeling jet-ISM interaction and its impact on galaxy evolution. There however do remain several lacunae that needs improvement. A primary drawback of kpc scale simulations of jet-ISM interaction is the inability to resolve cooling length scales at the outer surface of dense clouds. For example, as outlined in Appendix A of Meenakshi et al. [200], the typical cooling length5 in multi-phase simulations of Mukherjee et al. [169] ranges from pc, below the resolution of the simulations. Achieving such resolutions will require an order of magnitude increase in current resources, which remains a challenging task. Such resolutions are further required also to better understand the shock-cloud interaction, as demonstrated in Figure 2. Such intricate substructures of the cloudlets are not resolved in current simulations.Besides the need for better resolutions, most of the simulations in this domain have been carried out for only a few Myr, due to limitations of computational time requirements. However, this explores only a very short phase of the jet and galaxy’s lifetime. Larger scale feedback studies exploring the heating-cooling cycles of jet driven large scale feedback [20,274,275,276] have explored longer run times up to a Gyr. However, they do not resolve the multi-phase gas structures internal to the ISM. Future efforts have to explore at least few tens of Myr of run time, with self-consistent injection of AGN power to account for at least one duty cycle of the AGN. All of these would require larger computational resources, which is expected to become available in near future.In addition to the above, new physics based modules need to be incorporated to augment current capabilities of simulations. One such of primary importance is the need for inclusion of the chemistry of ionized and molecular gas phases and other species such as dust. Most numerical codes follow a single fluid prescription, with cooling of matter primary driven by pre-computed tables based on gas densities and temperatures. Very works [208,277] have included more sophisticated treatments of individual fluid elements. In addition to this, impact of photoionizing radiation from the central AGN have been largely unexplored in large scale simulations of AGN feedback, barring a few works [196,199,278,279]. Although well explored for studying cloud dynamics in broad line regions or close to wind lauch zones [e.g., see [280,281,282], and references therein], their effect on larger kpc scale simulations are yet to fully explored.Another ill-explored parameter is the effect of magnetic field on shock-cloud dynamics and starformation. Very simulations have included the evolution of magnetic fields [177,178] in simulations of jet-ISM interaction. Magnetic fields can potentially change the nature of shock-cloud interaction by affecting Kelvin-Helmholtz growth rates and also affect estimates of turbulence regulated starformation rates [229], and should be explored in more detail.Lastly, another key ingredient overlooked in the current literature is the effect of cosmic rays on the fluid dynamics of jet-ISM interaction in particular, and AGN feedback in general. Active interaction of the jet with dense clouds are expected to be strong sites of production of cosmic rays, due to diffusive shock acceleration at jet-cloud interfaces. Cosmic rays are expected to provide additional momentum and pressure to the fluid, which would in turn affect the local dynamics of the gas. This has been tentatively explored in some cases, e.g., for IC 5063 [283]. Inclusion of cosmic ray diffusion and heating in MHD simulations of galaxy formation is being actively explored by several groups [e.g., [284,285,286]]. However, their impact is yet to be explored in the context of multi-phase AGN feedback.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Appendix A. Duration of the Confined Phase of the Jet in the ISM

Appendix B. Observations of Jet-ISM Interaction

| Source/Survey | Gas phase | Comments & References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | J1430 (Tea Cup), J1509, J1356, part of the QSOFEED survey | Molecular (CO, WH2, PAH), Ionised | Part of a sample of 48 Type-2 Seyferts (44 detected in radio) with several examples of well defined jetted system driving outflows. [222,289,290,291,292,293] |

| 2 | NGC 5929 | Molecular (WH2), Ionised (FeII) | Outflows perpendicular to the jet axis.[218,294] |

| 3 | QFeedS survey [263] | Molecular (CO), Ionised ( HNOS) | Spatially resolved analysis of 5 sources from the QFeedS sample, also showing outflows perpendicular to the jet. [219,220,295] |

| 4 | NGC 5972 | Ionised (HOS) | Detection of jet induced shocks. [296] |

| 5 | 3C 293 (UGC 8782) | Molecular (WH2), Atomic (HI absorption), Ionised (HNS) | [297,298,299,300,301] |

| 6 | IC 5063 | Molecular (CO,WH2), Ionised (Emission lines IR/optical+Xrays) | A very well studied source with a jet strongly inclined into a kpc scale disk. Shows outflow perpendicular to the jet.[204,302,303,304,305,306] |

| 7 | NGC 5643, NGC 1068, NGC 1386, NGC 1365 | Ionised | Part of the MAGNUM survey, also including IC 5063. Several of these sources show outflow perpendicular to the jet. [217,307,308] |

| 8 | NGC 3393 | Molecular (CO), Ionised (Emission lines optical+Xrays) | [309,310,311] |

| 9 | NGC 7319 in Stephan’s quintet | Molecular (CO), Ionised | A well studied group of 5 interacting galaxies with one showing prominent jet-ISM interaction. [312,313] |

| 10 | 3C 326 | Molecular (CO,WH2), Ionised | Early evidence of strong jet induced turbulence, refined with better spatial resolution (JWST) to uncover in-situ outflows [210,314,315,316] |

| 11 | GATOS survey | Molecular (CO), Ionised | A survey of dusty CND of 19+ Seyferts [317,318]. Several show very prominent jet-ISM interaction, reported as part of this survey and also from other multi-wavelength observations. [319,320,321,322,323] |

| 12 | WIDE-AEGIS-2018003848 | Ionised | Detection of strong shock from emission line modelling, likely powered by the radio jet. [324] |

| 13 | B2 0258+35 (NGC 1167) | Molecular (CO), Ionised (Xray) | A confirmed detection of jet clearing the central kpc of dense gas. Tentative confirmation of thermal X-rays. [209,214,216,249] |

| 14 | NGC 3100, IC 1531, NGC 3557 | Molecular (CO,tentative HCO+) | A subset from a survey of 11 LERG, showing evidence of only mild jet-ISM interaction, in spite of potential conditions available for more stronger effects observed elsehwere. [197,325,326,327] |

| 15 | NGC 1052 | Ionised | Prominent ionised bubble along the galaxy’s minor axis, blown by a jet inclined towards a nuclear gas disk, besides detection of large scale disturbed kinematics and shocks. [328,329,330,331] |

| 16 | NGC 3079 | Radio (deceleration of knots), Ionised | A well studied source with prominent gas filaments from nuclear outflows [332]. Observed pc scale jet-ISM interaction[333,334], which may power the large scale outflow [335,336]. |

| 17 | XID2028 | Molecular (CO), Ionised | Co-spatial collimated molecular, ionised jet-driven outflows outflow piercing gas shells ( kpc) from the nucleus. [337],[338] |

| 18 | 4C 31.04 | Ionised, Neutral | CSS source with pc jet but large scale ( kpc) shocked gas. [203],[213] |

| 19 | NGC 3998 | Radio | Indirect evidence of jet-medium interaction from radio emission. [339] |

| 20 | NGC 4579 (Messier 58) | Molecular (CO,WH2,PAH), Ionised | [340] |

| 21 | IRAS 10565+2448 | Molecular (CO), Atomic (HI emission+absorption), Ionised | [341] |

| 22 | 4C 41.17 | Molecular (CO), Ionised | A galaxy associated with positive feedback [225,342] |

| 23 | PKS 1549-79 | Molecular (CO), Ionised, Atomic (HI absorption) | Nuclear molecular outflow, extended ionised outflow. [343,344] |

| 24 | Sub sample of 9 sources from the southern 2 Jy sample [345] | Ionised | Broad integrated outflowing emission lines (, FWHM) driven by jets. [346] |

| 25 | 3C 273 | Molecular (CO), Ionised | Expanding jet driven cocoon impinging on a gas disk. [347] |

| 26 | HE 1353-1917, HE0040-1105 | Ionised | Nuclear scale jet driven outflow. Part of the CARS survey. [348,349] |

| 27 | 4C 12.50 (F13451+1232) | Molecular (CO,WH2), Ionised | Strong jet driven nuclear ( pc) outflow[350][351][352], but not on large scales[353]. |

| 28 | TNJ 1338-1942 | Ionised | Jet impact on extra-galactic gas cloud with extreme kinematics. [354,355,356] |

| 29 | NGC 6328 (PKS 1718-649) | Molecular (CO) | GPS source with pc scale jet interacting with ambient gas. [357] |

| 30 | PKS 0023-26 | Molecular (CO) | [358] |

| 31 | HzRG-MRC 0152-209 (Dragonfly galaxy) | Molecular (CO) | Molecular outflow (jet/AGN driven) perpendicular to the jet, with indications of jet-ISM interaction at small scales. [359] |

| 32 | ESO 420-G13 | Molecular (CO), Ionised | [360] |

| 33 | Jet driven HI outflows (including 3C 236, 3C 305, 3C 459, OQ 208) | Molecular (CO), Atomic (HI absorption) | [361,362,363,364] |

| 34 | NGC 4258 (Messier 106) | Molecular (WH2), Ionised, Xrays | Detection of shocks and turbulence induced by jets. [231,232,233] |

| 35 | Molecular Hydrogen Emission line Galaxies (MOHEG) | Molecular (WH2) | A sample of 17 Radio Loud galaxies with detections of warm H2 lines and indications of jet driven shocks. [365] |

| 36 | PKS B1934-63 | Ionised, WH2 | Compact GPC source with ionised outflow but not in molecular phase. [366] |

| 37 | Cen A (NGC 5128) | Molecular (CO) | Jet induced inefficient starformation in filaments along the jet. [367],[368] |

| 38 | Cygnus A | Molecular (WH2, PAH), Ionised | High velocity kpc scale outflow driven by jet. [369] |

| 39 | SINFONI survey of RLAGN | Molecular (WH2), Ionised | A survey of 33 powerful RLAGN, confirming widespread jet-driven extreme gas kinematics. [211,212,370] |

| 40 | NGC 6951 | Ionised | [371] |

References

- Fabian, A.C. Observational Evidence of Active Galactic Nuclei Feedback. ARAA 2012, 50, 455–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C.M.; Ramos Almeida, C. Observational Tests of Active Galactic Nuclei Feedback: An Overview of Approaches and Interpretation. Galaxies 2024, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, S.M.; Silk, J.; Kellogg, E.; Murray, S. Thermal-Bremsstrahlung Interpretation of Cluster X-Ray Sources. ApJL 1973, 184, L105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowie, L.L.; Binney, J. Radiative regulation of gas flow within clusters of galaxies: a model for cluster X-ray sources. ApJ 1977, 215, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, A.C.; Nulsen, P.E.J. Subsonic accretion of cooling gas in clusters of galaxies. MNRAS 1977, 180, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, A.C.; Nulsen, P.E.J. Cooling flows, low-mass objects and the Galactic halo. MNRAS 1994, 269, L33. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, J.R.; Paerels, F.B.S.; Kaastra, J.S.; Arnaud, M.; Reiprich, T.H.; Fabian, A.C.; Mushotzky, R.F.; Jernigan, J.G.; Sakelliou, I. X-ray imaging-spectroscopy of Abell 1835. A&A 2001, 365, L104–L109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, T.; Kaastra, J.S.; Peterson, J.R.; Paerels, F.B.S.; Mittaz, J.P.D.; Trudolyubov, S.P.; Stewart, G.; Fabian, A.C.; Mushotzky, R.F.; Lumb, D.H.; et al. X-ray spectroscopy of the cluster of galaxies Abell 1795 with XMM-Newton. A&A 2001, 365, L87–L92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croton, D.J.; Springel, V.; White, S.D.M.; De Lucia, G.; Frenk, C.S.; Gao, L.; Jenkins, A.; Kauffmann, G.; Navarro, J.F.; Yoshida, N. The many lives of active galactic nuclei: cooling flows, black holes and the luminosities and colours of galaxies. MNRAS 2006, 365, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silk, J.; Rees, M.J. Quasars and galaxy formation. A&A 1998, 331, L1–L4. [Google Scholar]

- Bower, R.G.; Benson, A.J.; Malbon, R.; Helly, J.C.; Frenk, C.S.; Baugh, C.M.; Cole, S.; Lacey, C.G. Breaking the hierarchy of galaxy formation. MNRAS 2006, 370, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandford, R.; Meier, D.; Readhead, A. Relativistic Jets from Active Galactic Nuclei. ARAA 2019, 57, 467–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komissarov, S.; Porth, O. Numerical simulations of jets. New Astronomy Reviews 2021, 92, 101610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veilleux, S.; Maiolino, R.; Bolatto, A.D.; Aalto, S. Cool outflows in galaxies and their implications. Astron Astrophys Rev 2020, 28, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laha, S.; Reynolds, C.S.; Reeves, J.; Kriss, G.; Guainazzi, M.; Smith, R.; Veilleux, S.; Proga, D. Ionized outflows from active galactic nuclei as the essential elements of feedback. Nature Astronomy 2021, 5, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C.M. Impact of supermassive black hole growth on star formation. Nature Astronomy 2017, 1, 0165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morganti, R. The many routes to AGN feedback. Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences 2017, 4, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, D.; Gaspari, M.; Gastaldello, F.; Le Brun, A.M.C.; O’Sullivan, E. Feedback from Active Galactic Nuclei in Galaxy Groups. Universe 2021, 7, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combes, F. Active Galactic Nuclei: Fueling and Feedback; 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourne, M.A.; Yang, H.Y.K. Recent Progress in Modeling the Macro- and Micro-Physics of Radio Jet Feedback in Galaxy Clusters. Galaxies 2023, 11, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadhunter, C. Radio AGN in the local universe: unification, triggering and evolution. Astron Astrophys Rev 2016, 24, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dea, C.P.; Saikia, D.J. Compact steep-spectrum and peaked-spectrum radio sources. Astron Astrophys Rev 2021, 29, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardcastle, M.J.; Croston, J.H. Radio galaxies and feedback from AGN jets. New Astronomy Reviews 2020, 88, 101539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldi, R.D. The nature of compact radio sources: the case of FR 0 radio galaxies. Astron Astrophys Rev 2023, 31, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morganti, R.; Oosterloo, T. The interstellar and circumnuclear medium of active nuclei traced by H i 21 cm absorption. Astron Astrophys Rev 2018, 26, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storchi-Bergmann, T.; Schnorr-Müller, A. Observational constraints on the feeding of supermassive black holes. Nature Astronomy 2019, 3, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspari, M.; Tombesi, F.; Cappi, M. Linking macro-, meso- and microscales in multiphase AGN feeding and feedback. Nature Astronomy 2020, 4, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combes, F. Fueling Processes on (Sub-)kpc Scales. Galaxies 2023, 11, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.Y.; Bicknell, G.V.; Umemura, M.; Sutherland, R.S.; Silk, J. Galaxy-scale AGN feedback - theory. Astronomische Nachrichten 2016, 337, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D.; Bicknell, G.V.; Wagner, A.Y. Resolved simulations of jet–ISM interaction: Implications for gas dynamics and star formation. Astronomische Nachrichten 2021, 342, 1140–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morganti, R.; Murthy, S.; Guillard, P.; Oosterloo, T.; Garcia-Burillo, S. Young Radio Sources Expanding in Gas-Rich ISM: Using Cold Molecular Gas to Trace Their Impact. Galaxies 2023, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, M.G.H. Jet Feedback in Star-Forming Galaxies. Galaxies 2023, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, R.S.; Bicknell, G.V. Interactions of a Light Hypersonic Jet with a Nonuniform Interstellar Medium. ApJS 2007, 173, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandford, R.D.; Rees, M.J. A “twin-exhaust” model for double radio sources. MNRAS 1974, 169, 395–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuer, P.A.G. Models of extragalactic radio sources with a continuous energy supply from a central object. MNRAS 1974, 166, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandford, R.D.; Ostriker, J.P. Particle acceleration by astrophysical shocks. ApJL 1978, 221, L29–L32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayburn, D.R. A numerical study of the continuous beam model of extragalactic radio sources. MNRAS 1977, 179, 603–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokosawa, M.; Ikeuchi, S.; Sakashita, S. Structure and Expansion Law of a Hypersonic Beam. PASJ 1982, 34, 461. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, M.L.; Winkler, K.H.A.; Smarr, L.; Smith, M.D. Structure and dynamics of supersonic jets. A&A 1982, 113, 285–302. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, M.J.; Scheuer, P.A.G. The anisotropy of emission from hotspots in extragalactic radio sources. MNRAS 1983, 205, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.G.; Gull, S.F. A three-dimensional model of the fluid dynamics of radio-trail sources. Nature 1984, 310, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, C.N.; Arnett, W.D. Three-dimensional Structure and Dynamics of a Supersonic Jet. ApJL 1986, 305, L57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardee, P.E.; Clarke, D.A. The non-Linear Dynamics of a Three-Dimensional Jet. ApJ 1992, 400, L9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, M.L.; Balsara, D.S. 3-D Hydrodynamical Simulations of Extragalactic Jets. In Jets in Extragalactic Radio Sources; Röser, H.J., Meisenheimer, K., Eds.; 1993; Volume 421, p. 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, M.L.; Hardee, P.E. Spatial Stability of the Slab Jet. II. Numerical Simulations. ApJ 1988, 334, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D.A.; Norman, M.L.; Burns, J.O. Numerical Simulations of a Magnetically Confined Jet. ApJL 1986, 311, L63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D.A.; Norman, M.L.; Burns, J.O. Numerical Observations of a Simulated Jet with a Passive Helical Magnetic Field. ApJ 1989, 342, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koessl, D.; Mueller, E. Numerical simulations of astrophysical jets: the influence of boundary conditions and grid resolution. A&A 1988, 206, 204–218. [Google Scholar]

- Mignone, A.; Rossi, P.; Bodo, G.; Ferrari, A.; Massaglia, S. High-resolution 3D relativistic MHD simulations of jets. MNRAS 2010, 402, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.H.; Kellermann, K.I.; Shaffer, D.B.; Linfield, R.P.; Moffet, A.T.; Romney, J.D.; Seielstad, G.A.; Pauliny-Toth, I.I.K.; Preuss, E.; Witzel, A.; et al. Radio sources with superluminal velocities. Nature 1977, 268, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dell, S.L. The continuum radiation of compact extragalactic objects. In Proceedings of the BL Lac Objects; Wolfe, A.M., Ed. 1978; pp. 312–325. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, M.H.; Pearson, T.J.; Readhead, A.C.S.; Seielstad, G.A.; Simon, R.S.; Walker, R.C. Superluminal variations in 3C 120, 3C 273, and 3C 345. ApJ 1979, 231, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandford, R.D.; McKee, C.F.; Rees, M.J. Super-luminal expansion in extragalactic radio sources. Nature 1977, 267, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandford, R.D.; Königl, A. Relativistic jets as compact radio sources. ApJ 1979, 232, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.J. Steady relativistic fluid jets. MNRAS 1987, 226, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti, J.M.; Mueller, E.; Ibanez, J.M. Hydrodynamical simulations of relativistic jets. A&A 1994, 281, L9–L12. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, G.C.; Hughes, P.A. Simulations of Relativistic Extragalactic Jets. ApJL 1994, 436, L119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti, J.M.A.; Muller, E.; Font, J.A.; Ibanez, J.M. Morphology and Dynamics of Highly Supersonic Relativistic Jets. ApJL 1995, 448, L105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koide, S.; Nishikawa, K.I.; Mutel, R.L. A Two-dimensional Simulation of Relativistic Magnetized Jet. ApJL 1996, 463, L71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí, J.M.; Müller, E.; Font, J.A.; Ibáñez, J.M.Z.; Marquina, A. Morphology and Dynamics of Relativistic Jets. ApJ 1997, 479, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, A.; Hughes, P.A.; Duncan, G.C.; Hardee, P.E. A Comparison of the Morphology and Stability of Relativistic and Nonrelativistic Jets. ApJ 1999, 516, 729–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodo, G.; Mamatsashvili, G.; Rossi, P.; Mignone, A. Linear stability analysis of magnetized relativistic jets: the non-rotating case. MNRAS 2013, 434, 3030–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Putten, M.H.P.M. Knots in Simulations of Magnetized Relativistic Jets. ApJL 1996, 467, L57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, K.I.; Koide, S.; Sakai, J.i.; Christodoulou, D.M.; Sol, H.; Mutel, R.L. Three-Dimensional Magnetohydrodynamic Simulations of Relativistic Jets Injected along a Magnetic Field. ApJL 1997, 483, L45–L48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, K.I.; Koide, S.; Sakai, J.i.; Christodoulou, D.M.; Sol, H.; Mutel, R.L. Three-dimensional Magnetohydrodynamic Simulations of Relativistic Jets Injected into an Oblique Magnetic Field. ApJ 1998, 498, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komissarov, S.S. Numerical simulations of relativistic magnetized jets. MNRAS 1999, 308, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komissarov, S.S. A Godunov-type scheme for relativistic magnetohydrodynamics. MNRAS 1999, 303, 343–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koldoba, A.V.; Kuznetsov, O.A.; Ustyugova, G.V. An approximate Riemann solver for relativistic magnetohydrodynamics. MNRAS 2002, 333, 932–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Zanna, L.; Bucciantini, N. An efficient shock-capturing central-type scheme for multidimensional relativistic flows. I. Hydrodynamics. A&A 2002, 390, 1177–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Zanna, L.; Bucciantini, N.; Londrillo, P. An efficient shock-capturing central-type scheme for multidimensional relativistic flows. II. Magnetohydrodynamics. A&A 2003, 400, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leismann, T.; Antón, L.; Aloy, M.A.; Müller, E.; Martí, J.M.; Miralles, J.A.; Ibáñez, J.M. Relativistic MHD simulations of extragalactic jets. A&A 2005, 436, 503–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignone, A.; Plewa, T.; Bodo, G. The Piecewise Parabolic Method for Multidimensional Relativistic Fluid Dynamics. ApJS 2005, 160, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignone, A.; Bodo, G. An HLLC Riemann solver for relativistic flows - II. Magnetohydrodynamics. MNRAS 2006, 368, 1040–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D.; Bodo, G.; Mignone, A.; Rossi, P.; Vaidya, B. Simulating the dynamics and non-thermal emission of relativistic magnetized jets I. Dynamics. MNRAS 2020, 499, 681–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meenakshi, M.; Mukherjee, D.; Bodo, G.; Rossi, P. A polarization study of jets interacting with turbulent magnetic fields. MNRAS 2023, 526, 5418–5440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattia, G.; Del Zanna, L.; Bugli, M.; Pavan, A.; Ciolfi, R.; Bodo, G.; Mignone, A. Resistive relativistic MHD simulations of astrophysical jets. A&A 2023, 679, A49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perucho, M.; López-Miralles, J.; Gizani, N.A.B.; Martí, J.M.; Boccardi, B. On the large scale morphology of Hercules A: destabilized hot jets? MNRAS 2023, 523, 3583–3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, P.; Bodo, G.; Massaglia, S.; Capetti, A. The different flavors of extragalactic jets: Magnetized relativistic flows. A&A 2024, 685, A4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upreti, N.; Vaidya, B.; Shukla, A. Bridging simulations of kink instability in relativistic magnetized jets with radio emission and polarisation. Journal of High Energy Astrophysics 2024, 44, 146–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Bodo, G.; Tavecchio, F.; Rossi, P.; Capetti, A.; Massaglia, S.; Sciaccaluga, A.; Baldi, R.D.; Giovannini, G. FR0 jets and recollimation-induced instabilities. A&A 2024, 682, L19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Bodo, G.; Tavecchio, F.; Rossi, P.; Coppi, P.; Sciaccaluga, A.; Boula, S. How do recollimation-induced instabilities shape the propagation of hydrodynamic relativistic jets? arXiv e-prints arXiv:2503.18602. [CrossRef]

- Perucho, M.; Martí, J.M. A numerical simulation of the evolution and fate of a Fanaroff-Riley type I jet. The case of 3C 31. MNRAS 2007, 382, 526–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, P.; Mignone, A.; Bodo, G.; Massaglia, S.; Ferrari, A. Formation of dynamical structures in relativistic jets: the FRI case. A&A 2008, 488, 795–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perucho, M.; Martí, J.M.; Laing, R.A.; Hardee, P.E. On the deceleration of Fanaroff-Riley Class I jets: mass loading by stellar winds. MNRAS 2014, 441, 1488–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaglia, S.; Bodo, G.; Rossi, P.; Capetti, S.; Mignone, A. Making Faranoff-Riley I radio sources. I. Numerical hydrodynamic 3D simulations of low-power jets. A&A 2016, 596, A12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaglia, S.; Bodo, G.; Rossi, P.; Capetti, S.; Mignone, A. Making Faranoff-Riley I radio sources. II. The effects of jet magnetization. A&A 2019, 621, A132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, P.; Bodo, G.; Massaglia, S.; Capetti, A. The different flavors of extragalactic jets: The role of relativistic flow deceleration. A&A 2020, 642, A69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaglia, S.; Bodo, G.; Rossi, P.; Capetti, A.; Mignone, A. Making Fanaroff-Riley I radio sources. III. The effects of the magnetic field on relativistic jets’ propagation and source morphologies. A&A 2022, 659, A139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, A.; Seo, J.; Ryu, D.; Kang, H. A Simulation Study of Low-power Relativistic Jets: Flow Dynamics and Radio Morphology of FR-I Jets. ApJ 2024, 976, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perucho, M.; Martí, J.M.; Quilis, V. Long-term FRII jet evolution: clues from three-dimensional simulations. MNRAS 2019, 482, 3718–3735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; Kang, H.; Ryu, D. A Simulation Study of Ultra-relativistic Jets. II. Structures and Dynamics of FR-II Jets. ApJ 2021, 920, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perucho, M.; Martí, J.M.; Quilis, V. Long-term FRII jet evolution in dense environments. MNRAS 2022, 510, 2084–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begelman, M.C.; Cioffi, D.F. Overpressured Cocoons in Extragalactic Radio Sources. ApJ 1989, 345, L21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, C.R.; Alexander, P. A self-similar model for extragalactic radio sources. MNRAS 1997, 286, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falle, S.A.E.G. Self-similar jets. MNRAS 1991, 250, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, J.C.; O’Dea, C.P. Evolution of Global Properties of Powerful Radio Sources. I. Hydrodynamical Simulations in a Constant Density Atmosphere and Comparison with Self-similar Models. ApJS 2002, 141, 337–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S.M.; Tregillis, I.L.; Jones, T.W.; Ryu, D. Three-dimensional Simulations of MHD Jet Propagation through Uniform and Stratified External Environments. ApJ 2005, 633, 717–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perucho, M.; Quilis, V.; Martí, J.M. Intracluster Medium Reheating by Relativistic Jets. ApJ 2011, 743, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardcastle, M.J.; Krause, M.G.H. Numerical modelling of the lobes of radio galaxies in cluster environments. MNRAS 2013, 430, 174–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perucho, M.; Martí, J.M.; Quilis, V.; Ricciardelli, E. Large-scale jets from active galactic nuclei as a source of intracluster medium heating: cavities and shocks. MNRAS 2014, 445, 1462–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardcastle, M.J.; Krause, M.G.H. Numerical modelling of the lobes of radio galaxies in cluster environments - II. Magnetic field configuration and observability. MNRAS 2014, 443, 1482–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, W.; Hardcastle, M.J.; Krause, M.G.H. Numerical modelling of the lobes of radio galaxies in cluster environments - III. Powerful relativistic and non-relativistic jets. MNRAS 2016, 461, 2025–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, W.; Hardcastle, M.J.; Krause, M.G.H. Numerical modelling of the lobes of radio galaxies in cluster environments - IV. Remnant radio galaxies. MNRAS 2019, 490, 5807–5819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.H.; Heinz, S.; Enßlin, T.A. Jets, bubbles, and heat pumps in galaxy clusters. MNRAS 2019, 489, 1939–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerrim, L.A.; Shabala, S.S.; Yates-Jones, P.M.; Krause, M.G.H.; Turner, R.J.; Anderson, C.S.; Stewart, G.S.C.; Power, C.; Rodman, P.E. Faraday rotation as a probe of radio galaxy environment in RMHD AGN jet simulations. MNRAS 2024, 531, 2532–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, G.; Bagchi, J.; Thorat, K.; Deane, R.P.; Delhaize, J.; Saikia, D.J. Probing the formation of megaparsec-scale giant radio galaxies: I. Dynamical insights from magnetohydrodynamic simulations. A&A 2025, 693, A77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardcastle, M.J. A simulation-based analytic model of radio galaxies. MNRAS 2018, 475, 2768–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, J.H.; Bell, A.R.; Blundell, K.M.; Araudo, A.T. Ultrahigh energy cosmic rays from shocks in the lobes of powerful radio galaxies. MNRAS 2019, 482, 4303–4321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; Ryu, D.; Kang, H. A Simulation Study of Ultra-relativistic Jets. III. Particle Acceleration in FR-II Jets. ApJ 2023, 944, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; Ryu, D.; Kang, H. Model Spectrum of Ultrahigh-energy Cosmic Rays Accelerated in FR-I Radio Galaxy Jets. ApJ 2024, 962, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmura, T.; Machida, M. Simulations of two-temperature jets in galaxy clusters. I. Effect of jet magnetization on dynamics and electron heating. A&A 2023, 679, A160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmura, T.; Machida, M.; Akamatsu, H. Simulations of two-temperature jets in galaxy clusters. II. X-ray properties of the forward shock. A&A 2023, 679, A161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, R.K.; Chattopadhyay, I. The Morphology and Dynamics of Relativistic Jets with Relativistic Equation of State. ApJ 2023, 948, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, P.; Bodo, G.; Capetti, A.; Massaglia, S. 3D relativistic MHD numerical simulations of X-shaped radio sources. A&A 2017, 606, A57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, M.A.; Wagner, A.Y.; Bicknell, G.V.; Sutherland, R.S.; McNamara, B.R. Jet-intracluster medium interaction in Hydra A - I. Estimates of jet velocity from inner knots. MNRAS 2014, 444, 1600–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, M.A.; Wagner, A.Y.; Bicknell, G.V.; Sutherland, R.S.; McNamara, B.R. Jet-intracluster medium interaction in Hydra A - II The effect of jet precession. MNRAS 2015. submitted. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, M.A.; Krause, M.G.H.; Hardcastle, M.J. 3D hydrodynamic simulations of large-scale precessing jets: radio morphology. MNRAS 2020, 499, 5765–5781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, G.; Vaidya, B.; Rossi, P.; Bodo, G.; Mukherjee, D.; Mignone, A. Modelling X-shaped radio galaxies: Dynamical and emission signatures from the Back-flow model. A&A [arXiv:astro-ph.GA/2203.01347]. 2022, 662, A5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, G.; Vaidya, B.; Fendt, C. Deciphering the Morphological Origins of X-shaped Radio Galaxies: Numerical Modeling of Backflow versus Jet Reorientation. ApJS 2023, 268, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, G.; Fendt, C.; Thorat, K.; Bodo, G.; Rossi, P. X-shaped radio galaxies: probing jet evolution, ambient medium dynamics, and their intricate interconnection. Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences 2024, 11, 1371101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tregillis, I.L.; Jones, T.W.; Ryu, D. Simulating Electron Transport and Synchrotron Emission in Radio Galaxies: Shock Acceleration and Synchrotron Aging in Three-dimensional Flows. ApJ 2001, 557, 475–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tregillis, I.L.; Jones, T.W.; Ryu, D. Synthetic Observations of Simulated Radio Galaxies. I. Radio and X-Ray Analysis. ApJ 2004, 601, 778–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, B.; Mignone, A.; Bodo, G.; Rossi, P.; Massaglia, S. A Particle Module for the PLUTO Code. II. Hybrid Framework for Modeling Nonthermal Emission from Relativistic Magnetized Flows. ApJ 2018, 865, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D.; Bodo, G.; Rossi, P.; Mignone, A.; Vaidya, B. Simulating the dynamics and synchrotron emission from relativistic jets - II. Evolution of non-thermal electrons. MNRAS 2021, 505, 2267–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.H.; Heinz, S.; Hooper, E. A numerical study of the impact of jet magnetic topology on radio galaxy evolution. MNRAS 2023, 522, 2850–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meenakshi, M.; Mukherjee, D.; Bodo, G.; Rossi, P.; Harrison, C.M. A comparative study of radio signatures from winds and jets: modelling synchrotron emission and polarization. MNRAS 2024, 533, 2213–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.P.; Fendt, C.; Vaidya, B. Particles in Relativistic MHD Jets. I. Role of Jet Dynamics in Particle Acceleration. ApJ 2023, 952, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.P.; Fendt, C.; Vaidya, B. Particles in Relativistic Magnetohydrodynamic Jets. II. Bridging Jet Dynamics with Multi–wave band Nonthermal Emission Signatures. ApJ 2024, 976, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandford, R.D.; Koenigl, A. A Model for the Knots in the M87 Jet. ApJL 1979, 20, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Kraft, R.P.; Forman, W.R.; Jones, C.; Murray, S.S.; Hardcastle, M.J.; Worrall, D.M. Chandra Observations of the X-Ray Jet in Centaurus A. ApJ 2002, 569, 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardcastle, M.J.; Worrall, D.M.; Kraft, R.P.; Forman, W.R.; Jones, C.; Murray, S.S. Radio and X-Ray Observations of the Jet in Centaurus A. ApJ 2003, 593, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worrall, D.M. The X-ray jets of active galaxies. Astron Astrophys Rev 2009, 17, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogensberger, D.; Miller, J.M.; Mushotzky, R.; Brandt, W.N.; Kammoun, E.; Zoghbi, A.; Behar, E. Superluminal proper motion in the X-ray jet of Centaurus A. arXiv e-prints arXiv:2408.14078. [CrossRef]

- Begelman, M.C. Baby Cygnus A’s. In Proceedings of the Cygnus A: Study of a Radio Galaxy; Carilli, C.L., Harris, D.A., Eds.; Cambridge, 1996; p. 209. [Google Scholar]

- Bicknell, G.V.; Dopita, M.A.; O’Dea, C.P. Unification of the Radio and Optical Properties of GPS and CSS Radio Sources. ApJ 1997, 485, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dea, C.P. The Compact Steep-Spectrum and Gigahertz Peaked-Spectrum Radio Sources. PASP 1998, 110, 493–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begelman, M.C. Young radio galaxies and their environments. In Proceedings of the The Most Distant Radio Galaxies; Röttgering, H.J.A.; Best, P.N.; Lehnert, M.D., Eds. 1999; p. 173. [Google Scholar]

- Mandal, A.; Mukherjee, D.; Federrath, C.; Bicknell, G.V.; Nesvadba, N.P.H.; Mignone, A. Probing the role of self-gravity in clouds impacted by AGN-driven winds. MNRAS [arXiv:astro-ph.GA/2405.10005]. 2024, 531, 2079–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeYoung, D.S. F-R I and F-R II Radio Galaxies. ApJ 1993, 405, L13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Gómez, J.L.; Raga, A.C.; Williams, R.J.R. Jet-Cloud Interactions and the Brightening of the Narrow-Line Region in Seyfert Galaxies. ApJL 1997, 491, L73–L76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooda, J.S.; Wiita, P.J. Three-dimensional Simulations of Extragalactic Jets Crossing Interstellar Medium/Intracluster Medium Interfaces. ApJ 1996, 470, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooda, J.S.; Wiita, P.J. Instabilities in Three-dimensional Simulations of Astrophysical Jets Crossing Tilted Interfaces. ApJ 1998, 493, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, P.A.; Miller, M.A.; Duncan, G.C. Three-dimensional Hydrodynamic Simulations of Relativistic Extragalactic Jets. ApJ 2002, 572, 713–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, S.W.; O’Brien, T.J.; Dunlop, J.S. Structures produced by the collision of extragalactic jets with dense clouds. MNRAS 1999, 309, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wiita, P.J.; Hooda, J.S. Radio Jet Interactions with Massive Clouds. ApJ 2000, 534, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiita, P.J. Jet Propagation Through Irregular Media and the Impact of Lobes on Galaxy Formation. Ap&SS 2004, 293, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.; Wiita, P.J.; Ryu, D. Hydrodynamic Interactions of Relativistic Extragalactic Jets with Dense Clouds. ApJ 2007, 655, 769–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonuccio-Delogu, V.; Silk, J. Active galactic nuclei jet-induced feedback in galaxies - I. Suppression of star formation. MNRAS 2008, 389, 1750–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonuccio-Delogu, V.; Silk, J. Active galactic nuclei jet-induced feedback in galaxies - I. Suppression of star formation. MNRAS 2008, 389, 1750–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, R.; Sharma, P.; Sarkar, K.C.; Stone, J.M. Dissipation of AGN Jets in a Clumpy Interstellar Medium. ApJ 2024, 973, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, R.I.; McKee, C.F.; Colella, P. On the Hydrodynamic Interaction of Shock Waves with Interstellar Clouds. I. Nonradiative Shocks in Small Clouds. ApJ 1994, 420, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.L.; Bicknell, G.V.; Sutherland, R.S.; Bland-Hawthorn, J. Starburst-Driven Galactic Winds: Filament Formation and Emission Processes. ApJ 2009, 703, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittard, J.M.; Hartquist, T.W.; Falle, S.A.E.G. The turbulent destruction of clouds - II. Mach number dependence, mass-loss rates and tail formation. MNRAS 2010, 405, 821–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannapieco, E.; Brüggen, M. The Launching of Cold Clouds by Galaxy Outflows. I. Hydrodynamic Interactions with Radiative Cooling. ApJ 2015, 805, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banda-Barragán, W.E.; Parkin, E.R.; Federrath, C.; Crocker, R.M.; Bicknell, G.V. Filament formation in wind-cloud interactions - I. Spherical clouds in uniform magnetic fields. MNRAS 2016, 455, 1309–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittard, J.M.; Parkin, E.R. The turbulent destruction of clouds - III. Three-dimensional adiabatic shock-cloud simulations. MNRAS 2016, 457, 4470–4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banda-Barragán, W.E.; Federrath, C.; Crocker, R.M.; Bicknell, G.V. Filament formation in wind-cloud interactions- II. Clouds with turbulent density, velocity, and magnetic fields. MNRAS 2018, 473, 3454–3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronke, M.; Oh, S.P. The growth and entrainment of cold gas in a hot wind. MNRAS 2018, 480, L111–L115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottle, J.; Scannapieco, E.; Brüggen, M.; Banda-Barragán, W.; Federrath, C. The Launching of Cold Clouds by Galaxy Outflows. III. The Influence of Magnetic Fields. ApJ 2020, 892, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragile, P.C.; Murray, S.D.; Anninos, P.; van Breugel, W. Radiative Shock-induced Collapse of Intergalactic Clouds. ApJ 2004, 604, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragile, P.C.; Anninos, P.; Croft, S.; Lacy, M.; Witry, J.W.L. Numerical Simulations of a Jet-Cloud Collision and Starburst: Application to Minkowski’s Object. ApJ 2017, 850, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, M.; Alexander, P. Simulations of multiphase turbulence in jet cocoons. MNRAS 2007, 376, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugan, Z.; Gaibler, V.; Silk, J. Feedback by AGN Jets and Wide-angle Winds on a Galactic Scale. ApJ 2017, 844, 37–1608.01370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, C.L.; Jones, J.R.; Scannapieco, E.; Windhorst, R.A. Numerical Simulation of Star Formation by the Bow Shock of the Centaurus A Jet. ApJ 2017, 835, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laužikas, M.; Zubovas, K. Slow and steady does the trick: Slow outflows enhance the fragmentation of molecular clouds. A&A 2024, 690, A396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyakumar, S. Interaction of radio jets with clouds in the ambient medium: Numerical simulations. Astronomische Nachrichten 2009, 330, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolting, C.; Lacy, M.; Croft, S.; Fragile, P.C.; Linden, S.T.; Nyland, K.; Patil, P. Observations and Simulations of Radio Emission and Magnetic Fields in Minkowski’s Object. ApJ 2022, 936, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.Y.; Bicknell, G.V. Relativistic Jet Feedback in Evolving Galaxies. ApJ 2011, 728, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D.; Bicknell, G.V.; Wagner, A.e.Y.; Sutherland, R.S.; Silk, J. Relativistic jet feedback - III. Feedback on gas discs. MNRAS 2018, 479, 5544–5566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicknell, G.V.; Saxton, C.J.; Sutherland, R.S. GPS and CSS Sources - Theory and Modelling. PASA 2003, 20, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxton, C.J.; Bicknell, G.V.; Sutherland, R.S.; Midgley, S. Interactions of jets with inhomogeneous cloudy media. MNRAS 2005, 359, 781–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaibler, V.; Khochfar, S.; Krause, M. Asymmetries in extragalactic double radio sources: clues from 3D simulations of jet-disc interaction. MNRAS 2011, 411, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaibler, V.; Khochfar, S.; Krause, M.; Silk, J. Jet-induced star formation in gas-rich galaxies. MNRAS 2012, 425, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugan, Z.; Bryan, S.; Gaibler, V.; Silk, J.; Haas, M. Stellar Signatures of AGN-jet-triggered Star Formation. ApJ 2014, 796, 113–1404.0381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D.; Bicknell, G.V.; Sutherland, R.; Wagner, A. Relativistic jet feedback in high-redshift galaxies - I. Dynamics. MNRAS 2016, 461, 967–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, R.; Weaver, K.A. Simulations of AGN-driven Galactic Outflow Morphology and Content. AJ 2022, 163, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavijo-Bohórquez, W.E.; de Gouveia Dal Pino, E.M.; Melioli, C. Role of AGN and star formation feedback in the evolution of galaxy outflows. MNRAS 2024, 535, 1696–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asahina, Y.; Nomura, M.; Ohsuga, K. Enhancement of Feedback Efficiency by Active Galactic Nucleus Outflows via the Magnetic Tension Force in the Inhomogeneous Interstellar Medium. ApJ 2017, 840, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiacconi, D.; Sijacki, D.; Pringle, J.E. Galactic nuclei evolution with spinning black holes: method and implementation. MNRAS 2018, 477, 3807–3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, R.Y.; Bourne, M.A.; Sijacki, D. Blandford-Znajek jets in galaxy formation simulations: method and implementation. MNRAS 2021, 504, 3619–3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, R.Y.; Sijacki, D.; Bourne, M.A. Blandford-Znajek jets in galaxy formation simulations: exploring the diversity of outflows produced by spin-driven AGN jets in Seyfert galaxies. MNRAS 2022, 514, 4535–4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, R.Y.; Sijacki, D.; Bourne, M.A. Simulations of spin-driven AGN jets in gas-rich galaxy mergers. MNRAS 2024, 528, 5432–5451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Burillo, S.; Alonso-Herrero, A.; Ramos Almeida, C.; González-Martín, O.; Combes, F.; Usero, A.; Hönig, S.; Querejeta, M.; Hicks, E.K.S.; Hunt, L.K.; et al. The Galaxy Activity, Torus, and Outflow Survey (GATOS). I. ALMA images of dusty molecular tori in Seyfert galaxies. A&A 2021, 652, A98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komissarov, S.S.; Falle, S.A.E.G. LargeScale Structure of Relativistic Jets. In Proceedings of the Energy Transport in Radio Galaxies and Quasars; Hardee, P.E., Bridle, A.H., Zensus, J.A., Eds.; Astronomical Society of the Pacific Conference Series; 1996; Vol. 100, p. 173. [Google Scholar]

- Perucho, M.; Martí, J.M.; Quilis, V.; Borja-Lloret, M. Radio mode feedback: Does relativity matter? MNRAS 2017, 471, L120–L124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.Y.; Bicknell, G.V.; Umemura, M. Driving Outflows with Relativistic Jets and the Dependence of Active Galactic Nucleus Feedback Efficiency on Interstellar Medium Inhomogeneity. ApJ 2012, 757, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A.; Wong, T.; Ott, J.; Muller, E.; Pineda, J.L.; Mizuno, Y.; Bernard, J.P.; Paradis, D.; Maddison, S.; Reach, W.T.; et al. Physical properties of giant molecular clouds in the Large Magellanic Cloud. MNRAS 2010, 406, 2065–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A.; Meidt, S.E.; Colombo, D.; Schinnerer, E.; Pety, J.; Leroy, A.K.; Dobbs, C.L.; García-Burillo, S.; Thompson, T.A.; Dumas, G.; et al. A Comparative Study of Giant Molecular Clouds in M51, M33, and the Large Magellanic Cloud. ApJ 2013, 779, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faesi, C.M.; Lada, C.J.; Forbrich, J. The ALMA View of GMCs in NGC 300: Physical Properties and Scaling Relations at 10 pc Resolution. ApJ 2018, 857, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D.; Bicknell, G.V.; Sutherland, R.; Wagner, A. Erratum: Relativistic jet feedback in high-redshift galaxies I. Dynamics. MNRAS 2017, 471, 2790–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicknell, G.V.; Mukherjee, D.; Wagner, A.Y.; Sutherland, R.S.; Nesvadba, N.P.H. Relativistic jet feedback - II. Relationship to gigahertz peak spectrum and compact steep spectrum radio galaxies. MNRAS 2018, 475, 3493–3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D.; Wagner, A.Y.; Bicknell, G.V.; Morganti, R.; Oosterloo, T.; Nesvadba, N.; Sutherland, R.S. The jet-ISM interactions in IC 5063. MNRAS 2018, 476, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borodina, O.; Ni, Y.; Bennett, J.S.; Weinberger, R.; Bryan, G.L.; Hirschmann, M.; Farcy, M.; Hlavacek-Larrondo, J.; Hernquist, L. You Shall Not Pass! The Propagation of Low-/Moderate-powered Jets Through a Turbulent Interstellar Medium. ApJ 2025, 981, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bieri, R.; Dubois, Y.; Silk, J.; Mamon, G.A.; Gaibler, V. External pressure-triggering of star formation in a disc galaxy: a template for positive feedback. MNRAS 2016, 455, 4166–4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A.; Mukherjee, D.; Federrath, C.; Nesvadba, N.P.H.; Bicknell, G.V.; Wagner, A.Y.; Meenakshi, M. Impact of relativistic jets on the star formation rate: a turbulence-regulated framework. MNRAS 2021, 508, 4738–4757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cielo, S.; Bieri, R.; Volonteri, M.; Wagner, A.Y.; Dubois, Y. AGN feedback compared: jets versus radiation. MNRAS 2018, 477, 1336–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffa, I.; Prandoni, I.; Laing, R.A.; Paladino, R.; Parma, P.; de Ruiter, H.; Mignano, A.; Davis, T.A.; Bureau, M.; Warren, J. The AGN fuelling/feedback cycle in nearby radio galaxies I. ALMA observations and early results. MNRAS 2019, 484, 4239–4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostriker, J.P.; Choi, E.; Ciotti, L.; Novak, G.S.; Proga, D. Momentum Driving: Which Physical Processes Dominate Active Galactic Nucleus Feedback? ApJ 2010, 722, 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meenakshi, M.; Mukherjee, D.; Wagner, A.Y.; Nesvadba, N.P.H.; Morganti, R.; Janssen, R.M.J.; Bicknell, G.V. The extent of ionization in simulations of radio-loud AGNs impacting kpc gas discs. MNRAS 2022, 511, 1622–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

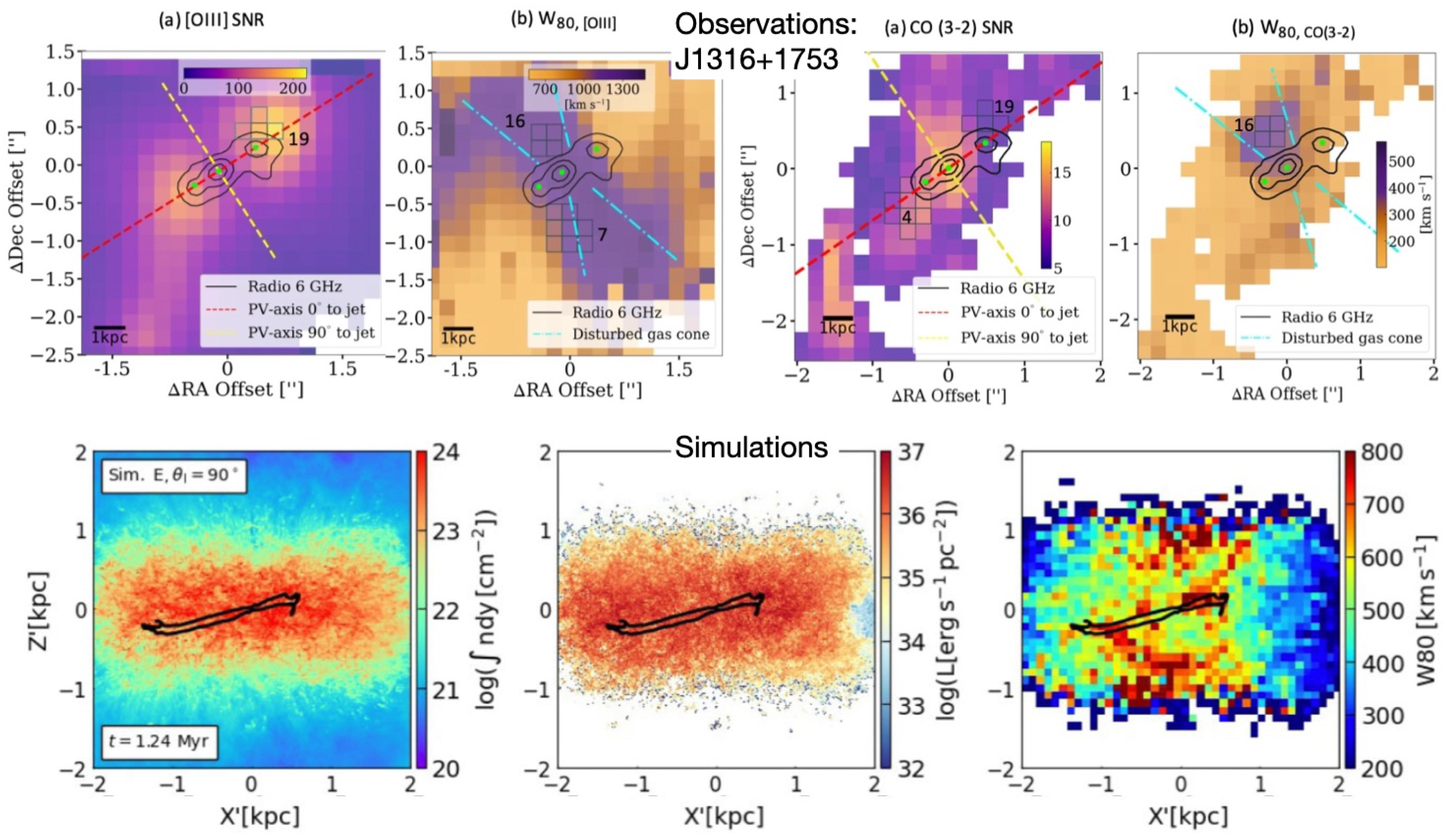

- Meenakshi, M.; Mukherjee, D.; Wagner, A.Y.; Nesvadba, N.P.H.; Bicknell, G.V.; Morganti, R.; Janssen, R.M.J.; Sutherland, R.S.; Mandal, A. Modelling observable signatures of jet-ISM interaction: thermal emission and gas kinematics. MNRAS 2022, 516, 766–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, R.S.; Dopita, M.A. Effects of Preionization in Radiative Shocks. I. Self-consistent Models. ApJS 2017, 229, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesvadba, N.P.H.; De Breuck, C.; Lehnert, M.D.; Best, P.N.; Binette, L.; Proga, D. The black holes of radio galaxies during the “Quasar Era”: masses, accretion rates, and evolutionary stage. A&A 2011, 525, A43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zovaro, H.R.M.; Sharp, R.; Nesvadba, N.P.H.; Bicknell, G.V.; Mukherjee, D.; Wagner, A.Y.; Groves, B.; Krishna, S. Jets blowing bubbles in the young radio galaxy 4C 31.04. MNRAS 2019, 484, 3393–3409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morganti, R.; Oosterloo, T.; Oonk, J.B.R.; Frieswijk, W.; Tadhunter, C. The fast molecular outflow in the Seyfert galaxy IC 5063 as seen by ALMA. A&A 2015, 580, A1–1505.07190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomé, Q.; Krongold, Y.; Longinotti, A.L.; Bischetti, M.; García-Burillo, S.; Vega, O.; Sánchez-Portal, M.; Feruglio, C.; Jiménez-Donaire, M.J.; Zanchettin, M.V. Star formation efficiency and AGN feedback in narrow-line Seyfert 1 galaxies with fast X-ray nuclear winds. MNRAS 2023, 524, 3130–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perucho, M.; López-Miralles, J.; Reynaldi, V.; Labiano, Á. Jet propagation through inhomogeneous media and shock ionization. Astronomische Nachrichten 2021, 342, 1171–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perucho, M.; López-Miralles, J. Numerical simulations of relativistic jets. Journal of Plasma Physics 2023, 89, 915890501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perucho, M. Shocks, clouds, and atomic outflows in active galactic nuclei hosting relativistic jets. A&A 2024, 684, A45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, S.; Morganti, R.; Wagner, A.Y.; Oosterloo, T.; Guillard, P.; Mukherjee, D.; Bicknell, G. Cold gas removal from the centre of a galaxy by a low-luminosity jet. Nature Astronomy 2022, 6, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesvadba, N.P.H.; Boulanger, F.; Salomé, P.; Guillard, P.; Lehnert, M.D.; Ogle, P.; Appleton, P.; Falgarone, E.; Pineau Des Forets, G. Energetics of the molecular gas in the H2 luminous radio galaxy 3C 326: Evidence for negative AGN feedback. A&A 2010, 521, A65–1003.3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collet, C.; Nesvadba, N.P.H.; De Breuck, C.; Lehnert, M.D.; Best, P.; Bryant, J.J.; Hunstead, R.; Dicken, D.; Johnston, H. Kinematic signatures of AGN feedback in moderately powerful radio galaxies at z ~2 observed with SINFONI. A&A 2016, 586, A152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesvadba, N.P.H.; De Breuck, C.; Lehnert, M.D.; Best, P.N.; Collet, C. The SINFONI survey of powerful radio galaxies at z 2: Jet-driven AGN feedback during the Quasar Era. A&A 2017, 599, A123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, S.; Morganti, R.; Oosterloo, T.; Schulz, R.; Paragi, Z. Turbulent circumnuclear disc and cold gas outflow in the newborn radio source 4C 31.04. A&A 2024, 688, A84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbiano, G.; Paggi, A.; Morganti, R.; Baloković, M.; Elvis, M.; Mukherjee, D.; Meenakshi, M.; Siemiginowska, A.; Murthy, S.M.; Oosterloo, T.A.; et al. Jet-ISM Interaction in NGC 1167/B2 0258+35, an LINER with an AGN Past. ApJ 2022, 938, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbiano, G.; Elvis, M. The Interaction of the Active Nucleus with the Host Galaxy Interstellar Medium. In Handbook of X-ray and Gamma-ray Astrophysics; Bambi, C., Sangangelo, A., Eds.; 2022; p. 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, S.; Morganti, R.; Oosterloo, T.; Mukherjee, D.; Bayram, S.; Guillard, P.; Wagner, A.Y.; Bicknell, G. Cold gas bubble inflated by a low-luminosity radio jet. A&A 2025, 694, A110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturi, G.; Cresci, G.; Marconi, A.; Mingozzi, M.; Nardini, E.; Carniani, S.; Mannucci, F.; Marasco, A.; Maiolino, R.; Perna, M.; et al. MAGNUM survey: Compact jets causing large turmoil in galaxies. Enhanced line widths perpendicular to radio jets as tracers of jet-ISM interaction. A&A 2021, 648, A17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riffel, R.A.; Storchi-Bergmann, T.; Riffel, R. An Outflow Perpendicular to the Radio Jet in the Seyfert Nucleus of NGC 5929. ApJL 2014, 780, L24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girdhar, A.; Harrison, C.M.; Mainieri, V.; Bittner, A.; Costa, T.; Kharb, P.; Mukherjee, D.; Arrigoni Battaia, F.; Alexander, D.M.; Calistro Rivera, G.; et al. Quasar feedback survey: multiphase outflows, turbulence, and evidence for feedback caused by low power radio jets inclined into the galaxy disc. MNRAS 2022, 512, 1608–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulivi, L.; Venturi, G.; Cresci, G.; Marconi, A.; Marconcini, C.; Amiri, A.; Belfiore, F.; Bertola, E.; Carniani, S.; D’Amato, Q.; et al. Feedback and ionized gas outflows in four low-radio power AGN at z ∼ 0.15. A&A 2024, 685, A122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruschel-Dutra, D.; Storchi-Bergmann, T.; Schnorr-Müller, A.; Riffel, R.A.; Dall’Agnol de Oliveira, B.; Lena, D.; Robinson, A.; Nagar, N.; Elvis, M. AGNIFS survey of local AGN: GMOS-IFU data and outflows in 30 sources. MNRAS 2021, 507, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audibert, A.; Ramos Almeida, C.; García-Burillo, S.; Combes, F.; Bischetti, M.; Meenakshi, M.; Mukherjee, D.; Bicknell, G.; Wagner, A.Y. Jet-induced molecular gas excitation and turbulence in the Teacup. A&A 2023, 671, L12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomé, Q.; Salomé, P.; Combes, F. Jet-induced star formation in 3C 285 and Minkowski’s Object. A&A 2015, 574, A34–1410.8367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy, M.; Croft, S.; Fragile, C.; Wood, S.; Nyland, K. ALMA Observations of the Interaction of a Radio Jet with Molecular Gas in Minkowski’s Object. ApJ 2017, 838, 146–1703.03006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesvadba, N.P.H.; Bicknell, G.V.; Mukherjee, D.; Wagner, A.Y. Gas, dust, and star formation in the positive AGN feedback candidate 4C 41.17 at z = 3.8. A&A 2020, 639, L13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggal, C.; O’Dea, C.P.; Baum, S.A.; Labiano, A.; Tadhunter, C.; Worrall, D.M.; Morganti, R.; Tremblay, G.R.; Dicken, D. Optical- and UV-continuum Morphologies of Compact Radio Source Hosts. ApJ 2024, 965, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesvadba, N.P.H.; Wagner, A.Y.; Mukherjee, D.; Mandal, A.; Janssen, R.M.J.; Zovaro, H.; Neumayer, N.; Bagchi, J.; Bicknell, G. Jet-driven AGN feedback on molecular gas and low star-formation efficiency in a massive local spiral galaxy with a bright X-ray halo. A&A 2021, 654, A8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumholz, M.R.; McKee, C.F. A General Theory of Turbulence-regulated Star Formation, from Spirals to Ultraluminous Infrared Galaxies. ApJ 2005, 630, 250–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federrath, C.; Klessen, R.S. The Star Formation Rate of Turbulent Magnetized Clouds: Comparing Theory, Simulations, and Observations. ApJ 2012, 761, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Kruit, P.C.; Oort, J.H.; Mathewson, D.S. The Radio Emission of NGC 4258 and the Possible Origin of Spiral Structure. A&A 1972, 21, 169. [Google Scholar]

- Cecil, G.; Greenhill, L.J.; DePree, C.G.; Nagar, N.; Wilson, A.S.; Dopita, M.A.; Pérez-Fournon, I.; Argon, A.L.; Moran, J.M. The Active Jet in NGC 4258 and Its Associated Shocks. ApJ 2000, 536, 675–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogle, P.M.; Lanz, L.; Appleton, P.N. Jet-shocked H2 and CO in the Anomalous Arms of Molecular Hydrogen Emission Galaxy NGC 4258. ApJL 2014, 788, L33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, P.N.; Diaz-Santos, T.; Fadda, D.; Ogle, P.; Togi, A.; Lanz, L.; Alatalo, K.; Fischer, C.; Rich, J.; Guillard, P. Jet-related Excitation of the [C II] Emission in the Active Galaxy NGC 4258 with SOFIA. ApJ 2018, 869, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, H.R.; van Breugel, W.; Miley, G.K. Optical observations of radio jets. ApJ 1980, 235, 749–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miley, G.K.; Heckman, T.M.; Butcher, H.R.; van Breugel, W.J.M. Optical emission from the extended radio source 3C 277.3 (Coma A). ApJL 1981, 247, L5–L9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckman, T.M.; Miley, G.K.; Balick, B.; van Breugel, W.J.M.; Butcher, H.R. An optical and radio investigation of the radio galaxy 3C 305. ApJ 1982, 262, 529–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miley, G.K.; Heckman, T.M.; Butcher, H.R.; van Breugel, W.J.M. Optical emission from the extended radio source 3C 277.3 (Coma A). ApJL 1981, 247, L5–L9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Breugel, W.; Heckman, T.; Butcher, H.; Miley, G. Extended optical line emission from 3C 293 : radio jets propagating through a rotating gaseous disk. ApJ 1984, 277, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Breugel, W.; Fomalont, E.B. Is 3C 310 blowing bubbles ? ApJL 1984, 282, L55–L58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, K.C.; Miley, G.K.; van Breugel, W. Alignment of radio and optical orientations in high-redshift radio galaxies. Nature 1987, 329, 604–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, P.J.; van Breugel, W.; Spinrad, H.; Djorgovski, S. A Correlation between the Radio and Optical Morphologies of Distant 3 CR Radio Galaxies. ApJL 1987, 321, L29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, W.H.; O’Dea, C.P.; Baum, S.A.; Sparks, W.B.; Biretta, J.; de Koff, S.; Golombek, D.; Lehnert, M.D.; Macchetto, F.; McCarthy, P.; et al. Hubble Space Telescope Imaging of Compact Steep-Spectrum Radio Sources. ApJS 1997, 110, 191–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vries, W.D.; O’Dea, C.P.; Baum, S.A.; Barthel, P.D. Optical-Radio Alignment in Compact Steep-Spectrum Radio Sources. ApJ 1999, 526, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, P.J. High redshift radio galaxies. ARAA 1993, 31, 639–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukreti, P.; Morganti, R.; Tadhunter, C.; Santoro, F. Ionised gas outflows over the radio AGN life cycle. A&A 2023, 674, A198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukreti, P.; Wylezalek, D.; Alb\’an, M.; DallAgnol de Oliveira, B. Feedback from low-to-moderate luminosity radio-AGN with MaNGA. arXiv e-prints [arXiv:astro-ph.GA/2503.20889]. arXiv:2503.20889. [CrossRef]

- Calistro Rivera, G.; Alexander, D.M.; Harrison, C.M.; Fawcett, V.A.; Best, P.N.; Williams, W.L.; Hardcastle, M.J.; Rosario, D.J.; Smith, D.J.B.; Arnaudova, M.I.; et al. Ubiquitous radio emission in quasars: Predominant AGN origin and a connection to jets, dust, and winds. A&A 2024, 691, A191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, P.; Stalin, C.S.; Saikia, D.J. Warm Ionized Gas Outflows in Active Galactic Nuclei: What Causes it? arXiv e-prints arXiv:2503.06719. [CrossRef]

- Murthy, S.; Morganti, R.; Oosterloo, T.; Schulz, R.; Mukherjee, D.; Wagner, A.Y.; Bicknell, G.; Prandoni, I.; Shulevski, A. Feedback from low-luminosity radio galaxies: B2 0258+35. A&A 2019, 629, A58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drevet Mulard, M.; Nesvadba, N.P.H.; Meenakshi, M.; Mukherjee, D.; Wagner, A.; Bicknell, G.; Neumayer, N.; Combes, F.; Zovaro, H.; Janssen, R.M.J.; et al. Star formation in a massive spiral galaxy with a radio-AGN. A&A 2023, 676, A35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgia, M. Spectral Ages of CSOs and CSS Sources. PASA 2003, 20, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, T.; Baan, W.A. The Dynamic Evolution of Young Extragalactic Radio Sources. ApJ 2012, 760, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, P.; Nyland, K.; Whittle, M.; Lonsdale, C.; Lacy, M.; Lonsdale, C.; Mukherjee, D.; Trapp, A.C.; Kimball, A.E.; Lanz, L.; et al. High-resolution VLA Imaging of Obscured Quasars: Young Radio Jets Caught in a Dense ISM. ApJ 2020, 896, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetti, A.; Dallacasa, D.; Fanti, C.; Fanti, R.; Mack, K.H. The B3-VLA CSS sample. VII. WSRT polarisation observations and the ambient Faraday medium properties revisited. A&A 2008, 487, 865–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, F.; Rossetti, A.; Junor, W.; Saikia, D.J.; Salter, C.J. Radio polarimetry of compact steep spectrum sources at sub-arcsecond resolution. A&A 2013, 555, A4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orienti, M. Radio properties of Compact Steep Spectrum and GHz-Peaked Spectrum radio sources. Astronomische Nachrichten 2016, 337, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemiginowska, A.; LaMassa, S.; Aldcroft, T.L.; Bechtold, J.; Elvis, M. X-Ray Properties of the Gigahertz Peaked and Compact Steep Spectrum Sources. ApJ 2008, 684, 811–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemiginowska, A.; Sobolewska, M.; Migliori, G.; Guainazzi, M.; Hardcastle, M.; Ostorero, L.; Stawarz. X-Ray Properties of the Youngest Radio Sources and Their Environments. ApJ 2016, 823, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, R.S.; Rodríguez-Ardila, A.; Dahmer-Hahn, L.; Fonseca-Faria, M.A.; Riffel, R.; Marinello, M.; Beuchert, T.; Callingham, J.R. Optical properties of Peaked Spectrum radio sources. MNRAS 2022, 511, 214–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanti, C. Radio properties of CSSs and GPSs. Astronomische Nachrichten 2009, 330, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda Marques, B.L.; Rodríguez-Ardila, A.; Fonseca-Faria, M.A.; Panda, S. Powerful Outflows of Compact Radio Galaxies. ApJ 2025, 978, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldi, R.D.; Capetti, A.; Massaro, F. FR0CAT: a FIRST catalog of FR 0 radio galaxies. A&A 2018, 609, A1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, M.E.; Harrison, C.M.; Mainieri, V.; Alexander, D.M.; Arrigoni Battaia, F.; Calistro Rivera, G.; Circosta, C.; Costa, T.; De Breuck, C.; Edge, A.C.; et al. The quasar feedback survey: discovering hidden Radio-AGN and their connection to the host galaxy ionized gas. MNRAS 2021, 503, 1780–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njeri, A.; Harrison, C.M.; Kharb, P.; Beswick, R.; Calistro-Rivera, G.; Circosta, C.; Mainieri, V.; Molyneux, S.; Mullaney, J.; Sasikumar, S. The quasar feedback survey: zooming into the origin of radio emission with e-MERLIN. MNRAS 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, M.E.; Harrison, C.M.; Mainieri, V.; Calistro Rivera, G.; Jethwa, P.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Alexander, D.M.; Circosta, C.; Costa, T.; De Breuck, C.; et al. High molecular gas content and star formation rates in local galaxies that host quasars, outflows, and jets. MNRAS 2020, 498, 1560–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molyneux, S.J.; Calistro Rivera, G.; De Breuck, C.; Harrison, C.M.; Mainieri, V.; Lundgren, A.; Kakkad, D.; Circosta, C.; Girdhar, A.; Costa, T.; et al. The Quasar Feedback Survey: characterizing CO excitation in quasar host galaxies. MNRAS 2024, 527, 4420–4439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, T.A.; Greene, J.E.; Ma, C.P.; Blakeslee, J.P.; Dawson, J.M.; Pandya, V.; Veale, M.; Zabel, N. The MASSIVE survey - XI. What drives the molecular gas properties of early-type galaxies. MNRAS 2019, 486, 1404–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadhunter, C.; Oosterloo, T.; Morganti, R.; Ramos Almeida, C.; Martín, M.V.; Emonts, B.; Dicken, D. An ALMA CO(1-0) survey of the 2Jy sample: large and massive molecular discs in radio AGN host galaxies. MNRAS 2024, 532, 4463–4485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffa, I.; Davis, T.A. Molecular Gas Kinematics in Local Early-Type Galaxies with ALMA. Galaxies 2024, 12, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audibert, A.; Dasyra, K.M.; Papachristou, M.; Fernández-Ontiveros, J.A.; Ruffa, I.; Bisigello, L.; Combes, F.; Salomé, P.; Gruppioni, C. CO in the ALMA Radio-source Catalogue (ARC): The molecular gas content of radio galaxies as a function of redshift. A&A 2022, 668, A67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, P.N.; Kauffmann, G.; Heckman, T.M.; Brinchmann, J.; Charlot, S.; Ivezić, Ž.; White, S.D.M. The host galaxies of radio-loud active galactic nuclei: mass dependences, gas cooling and active galactic nuclei feedback. MNRAS 2005, 362, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauch, T.; Sadler, E.M. Radio sources in the 6dFGS: local luminosity functions at 1.4GHz for star-forming galaxies and radio-loud AGN. MNRAS 2007, 375, 931–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabater, J.; Best, P.N.; Hardcastle, M.J.; Shimwell, T.W.; Tasse, C.; Williams, W.L.; Brüggen, M.; Cochrane, R.K.; Croston, J.H.; de Gasperin, F.; et al. The LoTSS view of radio AGN in the local Universe. The most massive galaxies are always switched on. A&A 2019, 622, A17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspari, M.; Melioli, C.; Brighenti, F.; D’Ercole, A. The dance of heating and cooling in galaxy clusters: three-dimensional simulations of self-regulated active galactic nuclei outflows. MNRAS 2011, 411, 349–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspari, M.; Ruszkowski, M.; Sharma, P. Cause and Effect of Feedback: Multiphase Gas in Cluster Cores Heated by AGN Jets. ApJ 2012, 746, 94–1110.6063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.Y.K.; Reynolds, C.S. How AGN Jets Heat the Intracluster Medium–Insights from Hydrodynamic Simulations. ApJ 2016, 829, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richings, A.J.; Faucher-Giguère, C.A. The origin of fast molecular outflows in quasars: molecule formation in AGN-driven galactic winds. MNRAS 2018, 474, 3673–3699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, O.; Juneau, S.; Bournaud, F.; Gabor, J.M. Thermal and Radiative Active Galactic Nucleus Feedback have a Limited Impact on Star Formation in High-redshift Galaxies. ApJ 2015, 800, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieri, R.; Dubois, Y.; Rosdahl, J.; Wagner, A.; Silk, J.; Mamon, G.A. Outflows driven by quasars in high-redshift galaxies with radiation hydrodynamics. MNRAS 2017, 464, 1854–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proga, D.; Kallman, T.R. Dynamics of Line-driven Disk Winds in Active Galactic Nuclei. II. Effects of Disk Radiation. ApJ 2004, 616, 688–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proga, D.; Jiang, Y.F.; Davis, S.W.; Stone, J.M.; Smith, D. The Effects of Irradiation on Cloud Evolution in Active Galactic Nuclei. ApJ 2014, 780, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyda, S.; Dannen, R.C.; Kallman, T.R.; Davis, S.W.; Proga, D. Time-Dependent AGN Disc Winds II – Effects of Photoionization. arXiv e-prints arXiv:2504.00117. [CrossRef]