Submitted:

08 May 2025

Posted:

09 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

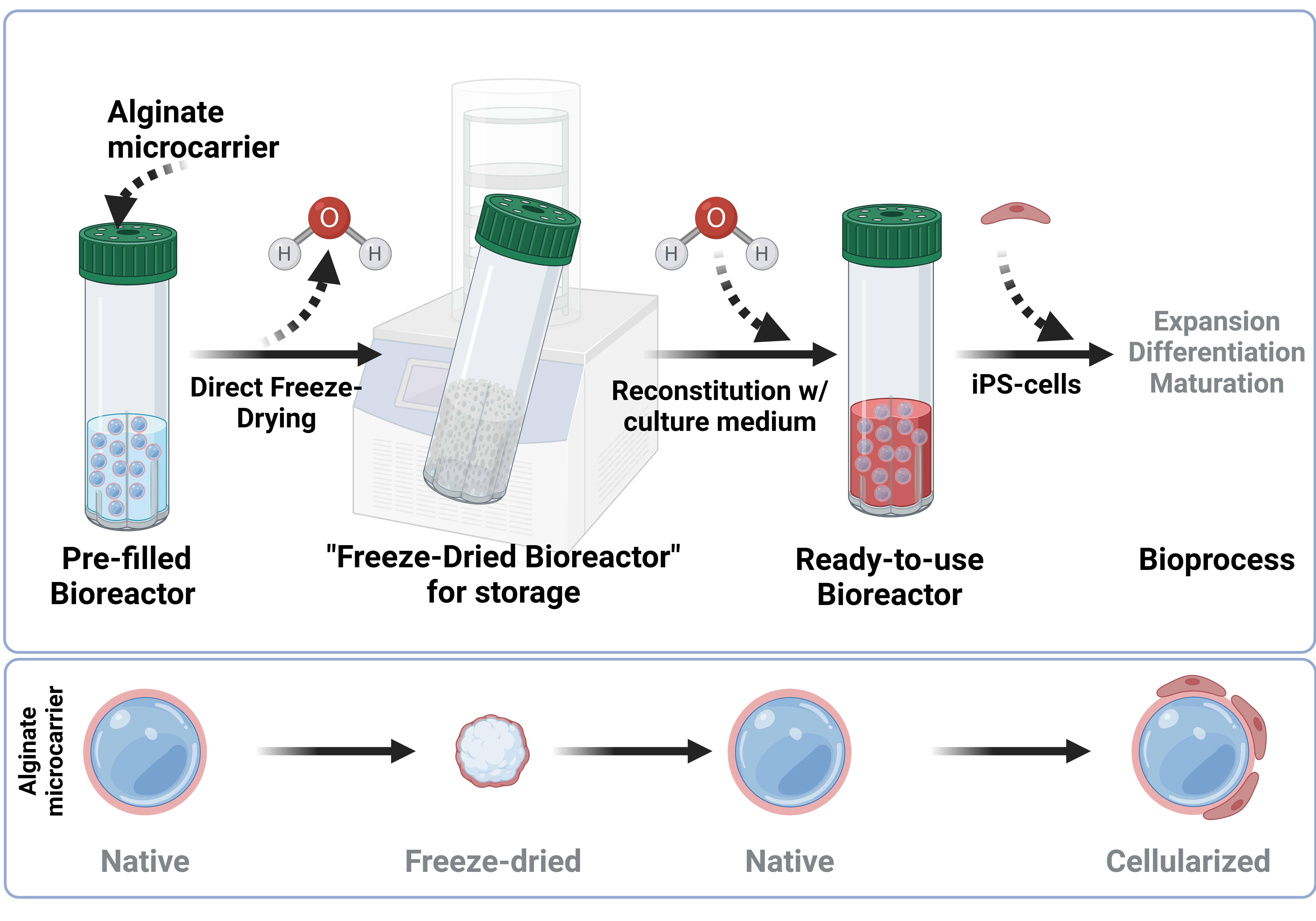

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

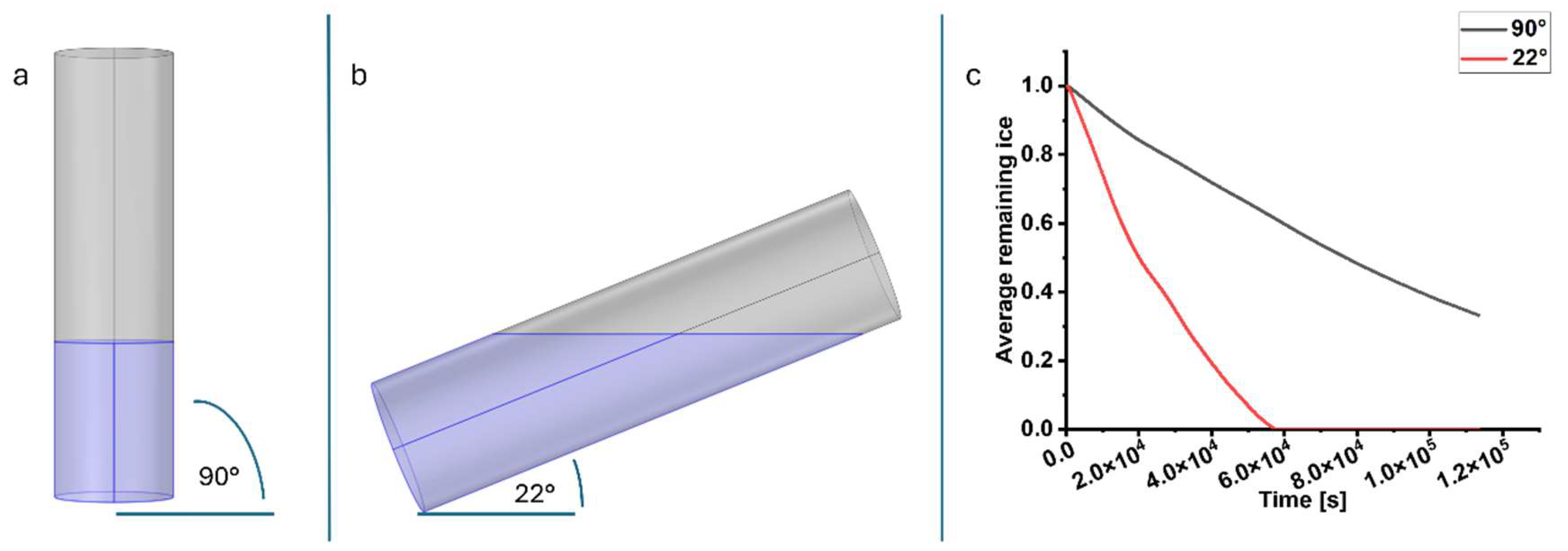

2.1. Simulation of a Modified Freeze-Drying Process for “Ready-to-Use” Alginate Microcarrier Hydrogels

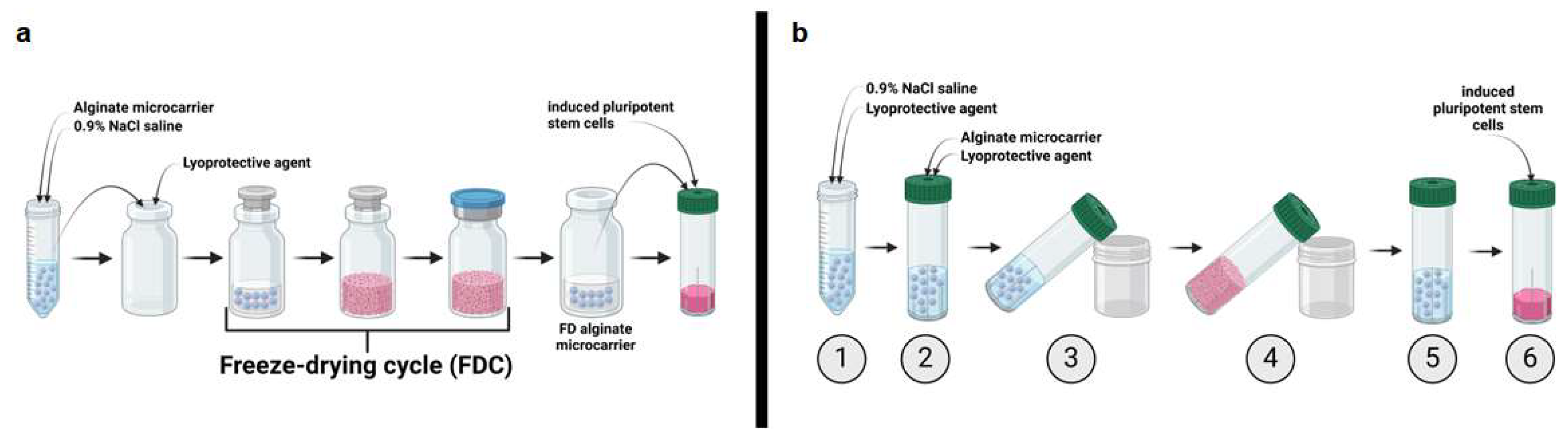

2.2. Implementation of a Freeze-Drying Process for “Ready-to-Use” Alginate Microcarrier

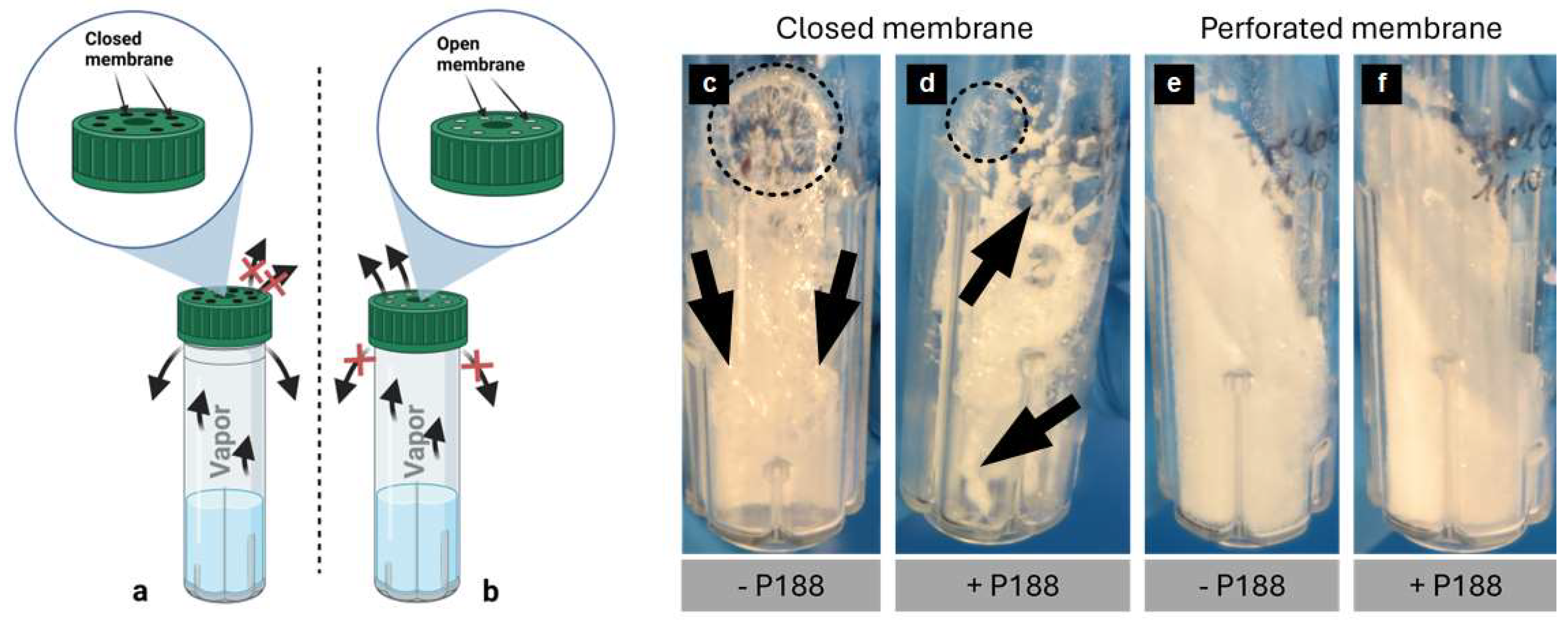

2.3. Analysis of Lyophilized Cake Appearance

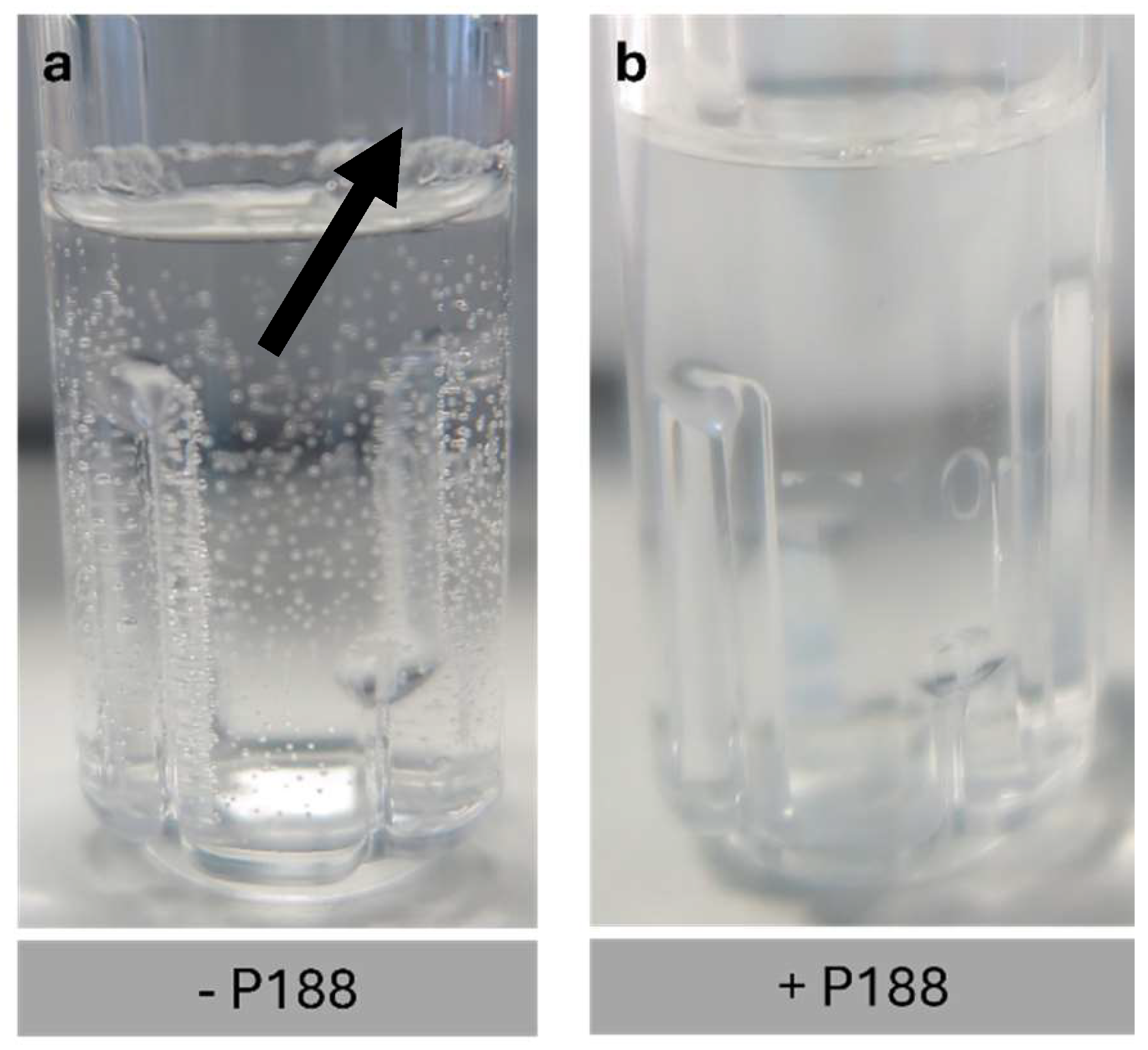

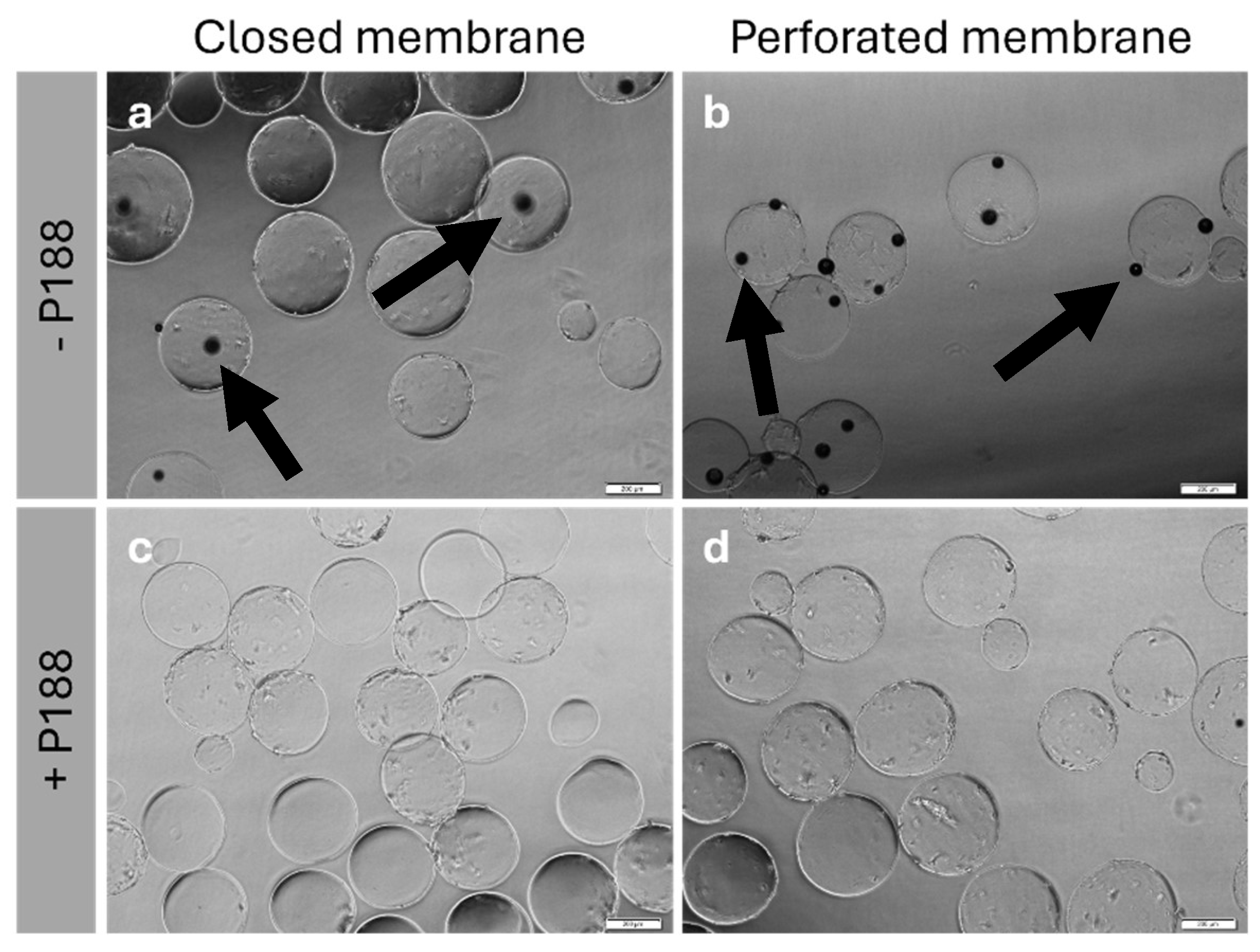

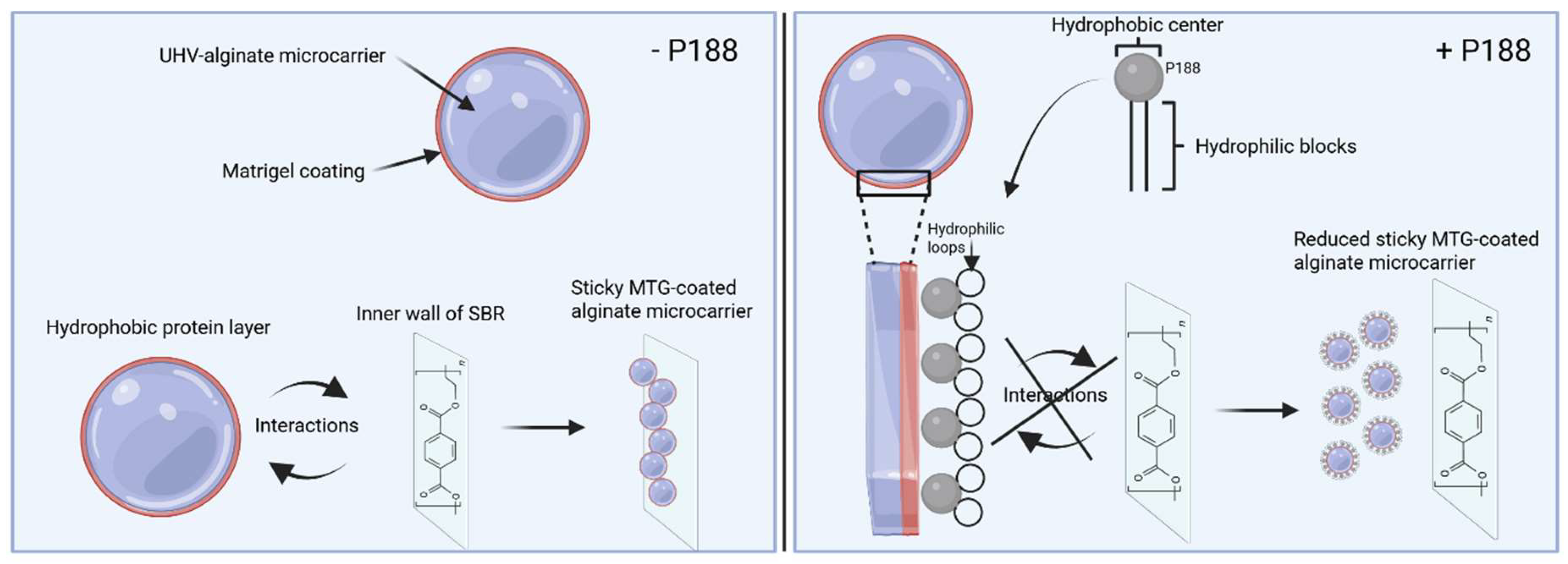

2.4. Impact of Poloxamer 188 on the Rehydration

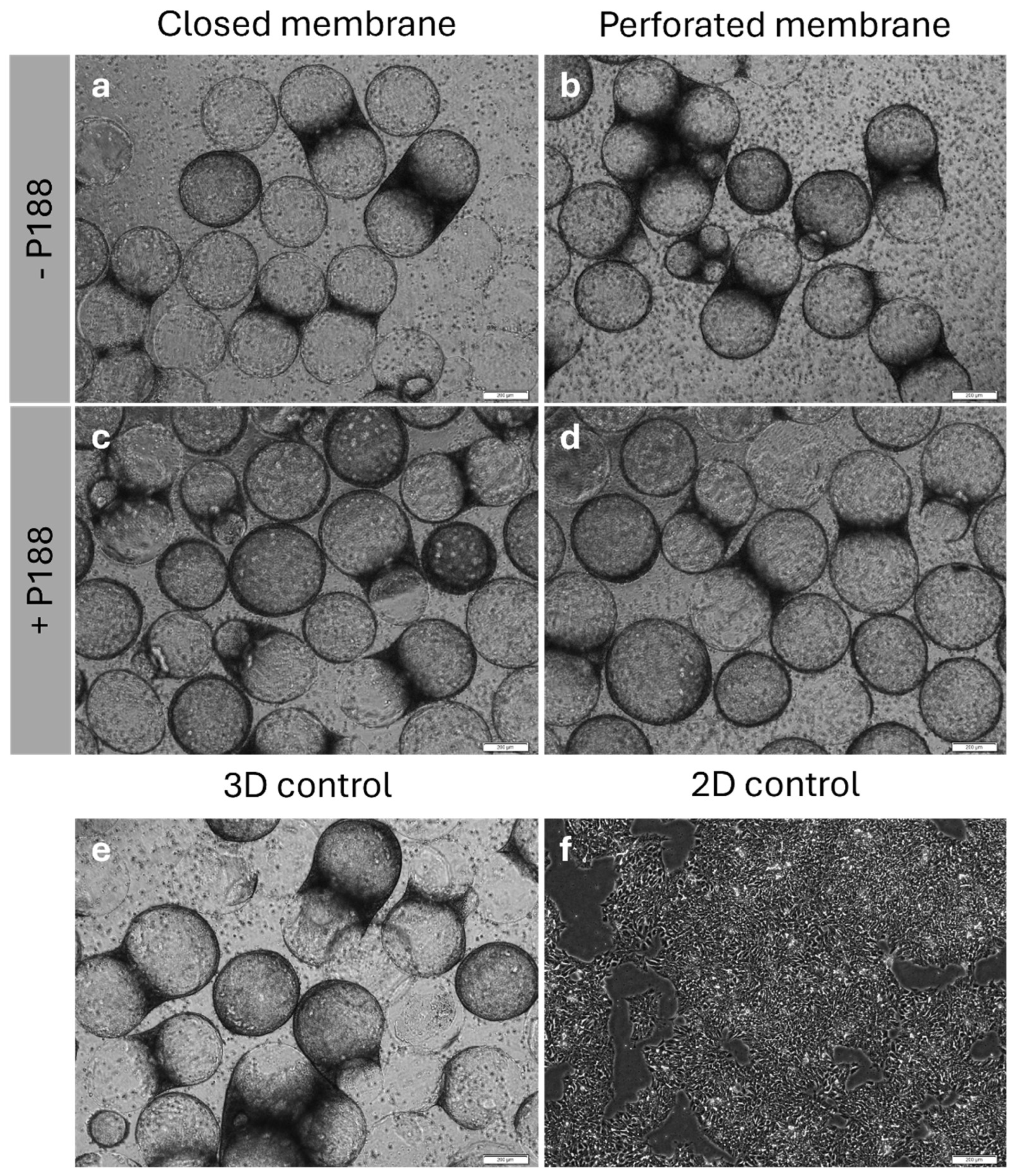

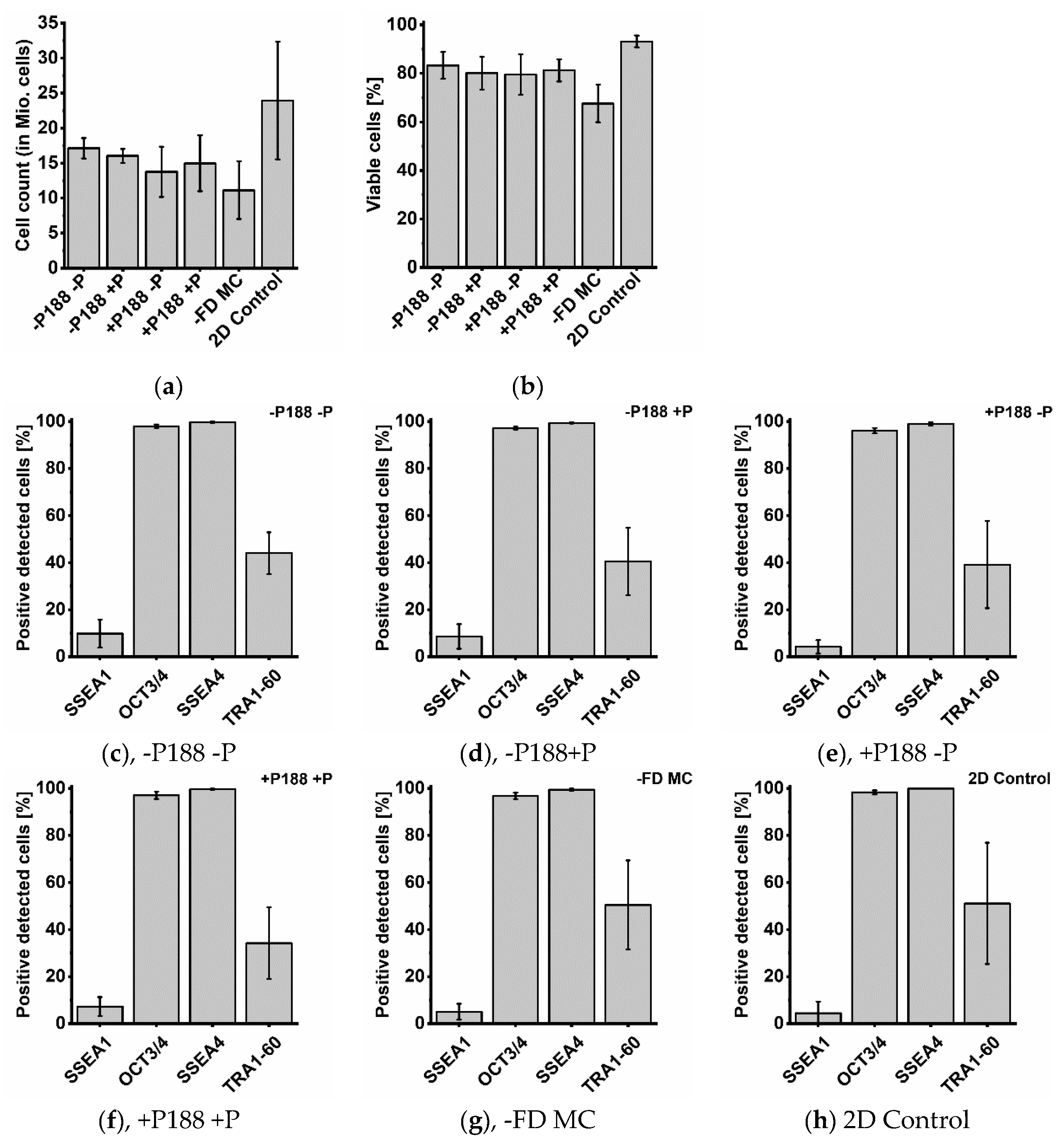

2.5. Cell Count, Cell Viability and Cytometry Analysis

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. In Silico Verification of SBR Orientation During Drying Process

4.2. Cell Culture

4.3. Hydrogel: UHV-Alginate Microcarrier

4.4. Freeze Drying and Rehydration

4.5. Dissociation of Single Cells

4.6. Cultivation of hiPSCs in a Suspension Bioreactor

4.7. Flow Cytometry Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schulz, A.; Gepp, M.M.; Stracke, F.; Briesen, H. von; Neubauer, J.C.; Zimmermann, H. Tyramine-conjugated alginate hydrogels as a platform for bioactive scaffolds. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2019, 107, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapałczyńska, M.; Kolenda, T.; Przybyła, W.; Zajączkowska, M.; Teresiak, A.; Filas, V.; Ibbs, M.; Bliźniak, R.; Łuczewski, Ł.; Lamperska, K. 2D and 3D cell cultures - a comparison of different types of cancer cell cultures. Arch. Med. Sci. 2018, 14, 910–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pampaloni, F.; Reynaud, E.G.; Stelzer, E.H.K. The third dimension bridges the gap between cell culture and live tissue. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, C.; Teng, Y. Is It Time to Start Transitioning From 2D to 3D Cell Culture? AAPS PharmSciTech 2020, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellin, M.; Marchetto, M.C.; Gage, F.H.; Mummery, C.L. Induced pluripotent stem cells: the new patient? Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallabhaneni, H.; Shah, T.; Shah, P.; Hursh, D.A. Suspension culture on microcarriers and as aggregates enables expansion and differentiation of pluripotent stem cells (PSCs). Cytotherapy 2023, 25, 993–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badenes, S.M.; Fernandes, T.G.; Rodrigues, C.A.V.; Diogo, M.M.; Cabral, J.M.S. Microcarrier-based platforms for in vitro expansion and differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells in bioreactor culture systems. J. Biotech. 2016, 234, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, J.G.; Dalton, B.A.; Johnson, G.; Underwood, P.A. Polystyrene chemistry affects vitronectin activity: an explanation for cell attachment to tissue culture polystyrene but not to unmodified polystyrene. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1993, 27, 927–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiger, A.S.; Hinton, B.; van Vliet, K.J. Why the dish makes a difference: quantitative comparison of polystyrene culture surfaces. Acta Biomater. 2013, 9, 7354–7361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Acevedo, S.; Crone, W.C. Substrate stiffness effect and chromosome missegregation in hIPS cells. J. Negat. Results Biomed. 2015, 14, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strale, P.-O.; Azioune, A.; Bugnicourt, G.; Lecomte, Y.; Chahid, M.; Studer, V. Multiprotein Printing by Light-Induced Molecular Adsorption. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 2024–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, K.K.Y.; Buschhaus, J.M.; Zhang, A.; Cutter, A.C.; Humphries, B.; Luker, G.D. Substrate stiffness regulates triple-negative breast cancer signaling through CXCR4 receptor dynamics. bioRxiv 2025. [CrossRef]

- Visonà, A.; Cavalaglio, S.; Labau, S.; Soulan, S.; Joisten, H.; Berger, F.; Dieny, B.; Morel, R.; Nicolas, A. Substrate softness increases magnetic microdiscs-induced cytotoxicity. Nanoscale Adv. 2024, 7, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wezel, A.L. Growth of cell-strains and primary cells on micro-carriers in homogeneous culture. Nature 1967, 216, 64–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-Y.; Chen, J.-Y.; Tong, X.-M.; Mei, J.-G.; Chen, Y.-F.; Mou, X.-Z. Recent advances in the use of microcarriers for cell cultures and their ex vivo and in vivo applications. Biotechnol. Lett. 2020, 42, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sart, S.; Agathos, S.N.; Li, Y. Engineering stem cell fate with biochemical and biomechanical properties of microcarriers. Biotechnol. Prog. 2013, 29, 1354–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spearman, M.; Rodriguez, J.; Huzel, N.; Butler, M. Production and glycosylation of recombinant beta-interferon in suspension and cytopore microcarrier cultures of CHO cells. Biotechnol. Prog. 2005, 21, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Gou, W.; Yuan, X.; Peng, J.; Guo, Q.; Lu, S. Past, present, and future of microcarrier-based tissue engineering. J. Orthop. Translat. 2015, 3, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavassoli, H.; Alhosseini, S.N.; Tay, A.; Chan, P.P.Y.; Weng Oh, S.K.; Warkiani, M.E. Large-scale production of stem cells utilizing microcarriers: A biomaterials engineering perspective from academic research to commercialized products. Biomaterials 2018, 181, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, Q.A.; Coopman, K.; Nienow, A.W.; Hewitt, C.J. Systematic microcarrier screening and agitated culture conditions improves human mesenchymal stem cell yield in bioreactors. Biotechnol. J. 2016, 11, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simão, V.A.; Brand, H.; Da Silveira-Antunes, R.N.; Fukasawa, J.T.; Leme, J.; Tonso, A.; Ribeiro-Paes, J.T. Adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) culture in spinner flask: improving the parameters of culture in a microcarrier-based system. Biotechnol. Lett. 2023, 45, 823–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Kallos, M.S.; Hunter, C.; Sen, A. Improved expansion of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in microcarrier-based suspension culture. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2014, 8, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, A.P.; Briheim, K.; Hanna, V.; Gustafsson, K.; Starkenberg, A.; Vintertun, H.N.; Kratz, G.; Junker, J.P.E. Transplantation of autologous cells and porous gelatin microcarriers to promote wound healing. Burns 2021, 47, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, C.K.; Sébastien, I.; Hariharan, K.; Meiser, I.; Wihan, J.; Altmaier, S.; Karnatz, I.; Bauer, D.; Fischer, B.; Feile, A.; et al. Scalable expansion of iPSC and their derivatives across multiple lineages. Reprod. Toxicol. 2022, 112, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storz, H.; Müller, K.J.; Ehrhart, F.; Gómez, I.; Shirley, S.G.; Gessner, P.; Zimmermann, G.; Weyand, E.; Sukhorukov, V.L.; Forst, T.; et al. Physicochemical features of ultra-high viscosity alginates. Carbohydr. Res. 2009, 344, 985–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storz, H.; Zimmermann, U.; Zimmermann, H.; Kulicke, W.-M. Viscoelastic properties of ultra-high viscosity alginates. Rheol. Acta 2010, 49, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, H.; Shirley, S.G.; Zimmermann, U. Alginate-based encapsulation of cells: past, present, and future. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2007, 7, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gepp, M.M.; Fischer, B.; Schulz, A.; Dobringer, J.; Gentile, L.; Vásquez, J.A.; Neubauer, J.C.; Zimmermann, H. Bioactive surfaces from seaweed-derived alginates for the cultivation of human stem cells. J. Appl. Phycol. 2017, 29, 2451–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodero, A.; Pianella, L.; Vicini, S.; Alloisio, M.; Ottonelli, M.; Castellano, M. Alginate-based hydrogels prepared via ionic gelation: An experimental design approach to predict the crosslinking degree. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 118, 586–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitoh, S.; Araki, Y.; Kon, R.; Katsura, H.; Taira, M. Swelling/deswelling mechanism of calcium alginate gel in aqueous solutions. Dent. Mater. J. 2000, 19, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boontheekul, T.; Kong, H.-J.; Mooney, D.J. Controlling alginate gel degradation utilizing partial oxidation and bimodal molecular weight distribution. Biomater. 2005, 26, 2455–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.L.; Pikal, M.J. Mechanisms of protein stabilization in the solid state. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009, 98, 2886–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensink, M.A.; Frijlink, H.W.; van der Voort Maarschalk, K.; Hinrichs, W.L.J. How sugars protect proteins in the solid state and during drying (review): Mechanisms of stabilization in relation to stress conditions. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2017, 114, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardeshi, S.R.; Deshmukh, N.S.; Telange, D.R.; Nangare, S.N.; Sonar, Y.Y.; Lakade, S.H.; Harde, M.T.; Pardeshi, C.V.; Gholap, A.; Deshmukh, P.K.; et al. Process development and quality attributes for the freeze-drying process in pharmaceuticals, biopharmaceuticals and nanomedicine delivery: a state-of-the-art review. Futur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soofi, S.S.; Last, J.A.; Liliensiek, S.J.; Nealey, P.F.; Murphy, C.J. The elastic modulus of Matrigel as determined by atomic force microscopy. J. Struct. Biol. 2009, 167, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisenbrey, E.A.; Murphy, W.L. Synthetic alternatives to Matrigel. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020, 5, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talbot, N.C.; Caperna, T.J. Proteome array identification of bioactive soluble proteins/peptides in Matrigel: relevance to stem cell responses. Cytotechnology 2015, 67, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diebels, S.; Gepp, M.M.; Meiser, I.; Roland, M.; Stracke, F.; Zimmermann, H. A multiphase model for the cross-linking of ultra-high viscous alginate hydrogels. Proc. Appl. Math. Mech. 2021, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Buckner, I.S.; Block, L.H. Inter-grade and inter-batch variability of sodium alginate used in alginate-based matrix tablets. AAPS PharmSciTech 2014, 15, 1228–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaniotto, F.; Prosapio, V.; Zafeiri, I.; Spyropoulos, F. Freeze drying and rehydration of alginate fluid gels. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 99, 105352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merivaara, A.; Zini, J.; Koivunotko, E.; Valkonen, S.; Korhonen, O.; Fernandes, F.M.; Yliperttula, M. Preservation of biomaterials and cells by freeze-drying: Change of paradigm. J. Control. Release 2021, 336, 480–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odziomek, K.; Drabczyk, A.K.; Kościelniak, P.; Konieczny, P.; Barczewski, M.; Bialik-Wąs, K. The Role of Freeze-Drying as a Multifunctional Process in Improving the Properties of Hydrogels for Medical Use. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pansare, S.K.; Patel, S.M. Lyophilization Process Design and Development: A Single-Step Drying Approach. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 108, 1423–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.M.; Nail, S.L.; Pikal, M.J.; Geidobler, R.; Winter, G.; Hawe, A.; Davagnino, J.; Rambhatla Gupta, S. Lyophilized Drug Product Cake Appearance: What Is Acceptable? J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 106, 1706–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torcello-Gómez, A.; Wulff-Pérez, M.; Gálvez-Ruiz, M.J.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Cabrerizo-Vílchez, M.; Maldonado-Valderrama, J. Block copolymers at interfaces: interactions with physiological media. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014, 206, 414–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollenbach, L.; Buske, J.; Mäder, K.; Garidel, P. Poloxamer 188 as surfactant in biological formulations - An alternative for polysorbate 20/80? Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 620, 121706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakaew, S.; Luangpradikun, K.; Phimnuan, P.; Nuengchamnong, N.; Kamonsutthipaijit, N.; Rugmai, S.; Nakyai, W.; Ross, S.; Ungsurungsei, M.; Viyoch, J.; et al. Investigation into poloxamer 188-based cubosomes as a polymeric carrier for poor water-soluble actives. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Ali, A.; Lanan, M.; Hughes, E.; Wiltberger, K.; Guan, B.; Prajapati, S.; Hu, W. Mechanism investigation for poloxamer 188 raw material variation in cell culture. Biotechnol. Prog. 2016, 32, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.; Fox, R.; Hicks, E.; Ferguson, R.; Chang, K.; Osborne, D.; Hu, W.; Velev, O.D. Investigation of interfacial properties of pure and mixed poloxamers for surfactant-mediated shear protection of mammalian cells. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2017, 156, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, D.M.; Koop, T. Review of the vapour pressures of ice and supercooled water for atmospheric applications. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2005, 131, 1539–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Brand name | Manufacturer or Reference | Dimension | Type | Material | Stiffness |

| NuncTM | Thermo Fisher Scientific, [8,9] | Flat | Wellplates, culture dishes, flasks | Polystyrene (Nunclon delta) | 2.28-3.28 GPa [10] |

| Elastically Supported Surface (ESS) | Ibidi, [11,12] | Flat | Culture dishes | Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) with glass bottom | 1.5, 15. 28 kPa |

| SoftwellTM, Petrisoft, Softslip, Soft Flask | Matrigen, https://store.matrigen.com | flat | Wellplates, culture dishes, flasks | Polyacrylamide-based gel bound on polystyrene or glass | 0.1-100 kPa |

| CytoSoft® | Advanced BIOMATRIX, https://advancedbiomatrix.com/cytosoft/ | Flat | Wellplates, flasks | PDMS (with glass bottom) | 0.2-64 kPa |

| MecaChips® | Cell&Soft, [13] | Flat | Culture dishes, wellplates | ECM Proteins or synthetic amino acid | 1-25 kPa |

| CytodexTM 1 | Cytiva, [14,15] | Sphere | Microcarrier | Diethylaminoethyl (DEAE)-groups coupled on Dextran | n.d. |

| CytodexTM 3 | Cytiva, [15,16] | Sphere | Microcarrier | Denaturated collagen coated on dextran | n.d. |

| CytoporeTM 1 | Cytiva, [15,17] | Sphere | Microcarrier | DEAE-groups coupled on cellulose | n.d. |

| Solohill® | Sartorius, [18,19] | Sphere | Microcarrier | (Modified or cross-linked) polystyrene & available with (surface modified) Type 1 porcine collagen coating | n.d. |

| Corning® Microcarrier | Corning, [20] | Sphere | Microcarrier | Polystyrene coated with e.g., Synthemax II® | n.d. |

| Dissolvable microcarriers | IamFluidics & Rousselot Biomedical, https://iamfluidics.com/products/dissolvable-microcarriers/ | Sphere | Dissolvable microcarrier | Sodium alginate coated with denaturated collagen | n.d. |

| CultiSpher®: G, GL, S | Percell Biolytica, [21,22,23] | Sphere | Microcarrier | Gelatine | n.d. |

| Parameter | Ramp | Hold | Ramp | Hold | Ramp | Hold |

| Temperature [°C] | Maximum | Maximum | Maximum | Maximum | 20 | 20 |

| Pressure [mbar] | / | / | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Time [h] | 2.5 | 12 | 1.5 | 30 | 5 | ≥8 |

| Event | Freezing | Freezing | Primary drying | Primary drying | Secondary drying | Secondary drying |

| Program | Rotation period [s] | Rotation speed [rpm] | Agitation period [min] | Agitation pause [min] | Duration |

| Inoculation | 4 | 40 | 2 | 5 | 12 h |

| Cultivation | 4 | 40 | 2 | / | 7 days |

| Harvesting | 5 | 60 | / | / | 20 min |

| Antibodies | Dilution |

| Alexa Fluor® 647 Rat anti-SSEA4 Alexa 647 Mouse IgG3, K Isotype Control |

20 µl per million cells |

| PerCP-CyTM 5.5 Mouse anti-OCT3/4 PerCP-CyTM 5.5 Mouse IgG1, K Isotype Control |

20 µl per million cells |

| PE Rat anti-SSEA1 PE Mouse IgM, K Isotype Control |

20 µl per million cells |

| Alexa Fluor® 488 anti-human TRA1-60 Alexa 488 Mouse IgM, K Isotype Control |

5 µl per million cells |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).