Submitted:

09 May 2025

Posted:

13 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Experiment Conditions and Switchgrass Management

2.1.1. Field and Weather Characteristics

2.1.2. Switchgrass Cultivars and Management

2.2. Sample Preparation and Chemical Analyses

2.2.1. Plant Material and Silage Preparation

2.2.2. Chemical Analyses of Biomass and Silage

2.3. Anaerobic Digestion Experiments

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Compositions of Harvested and Ensiled Biomasses

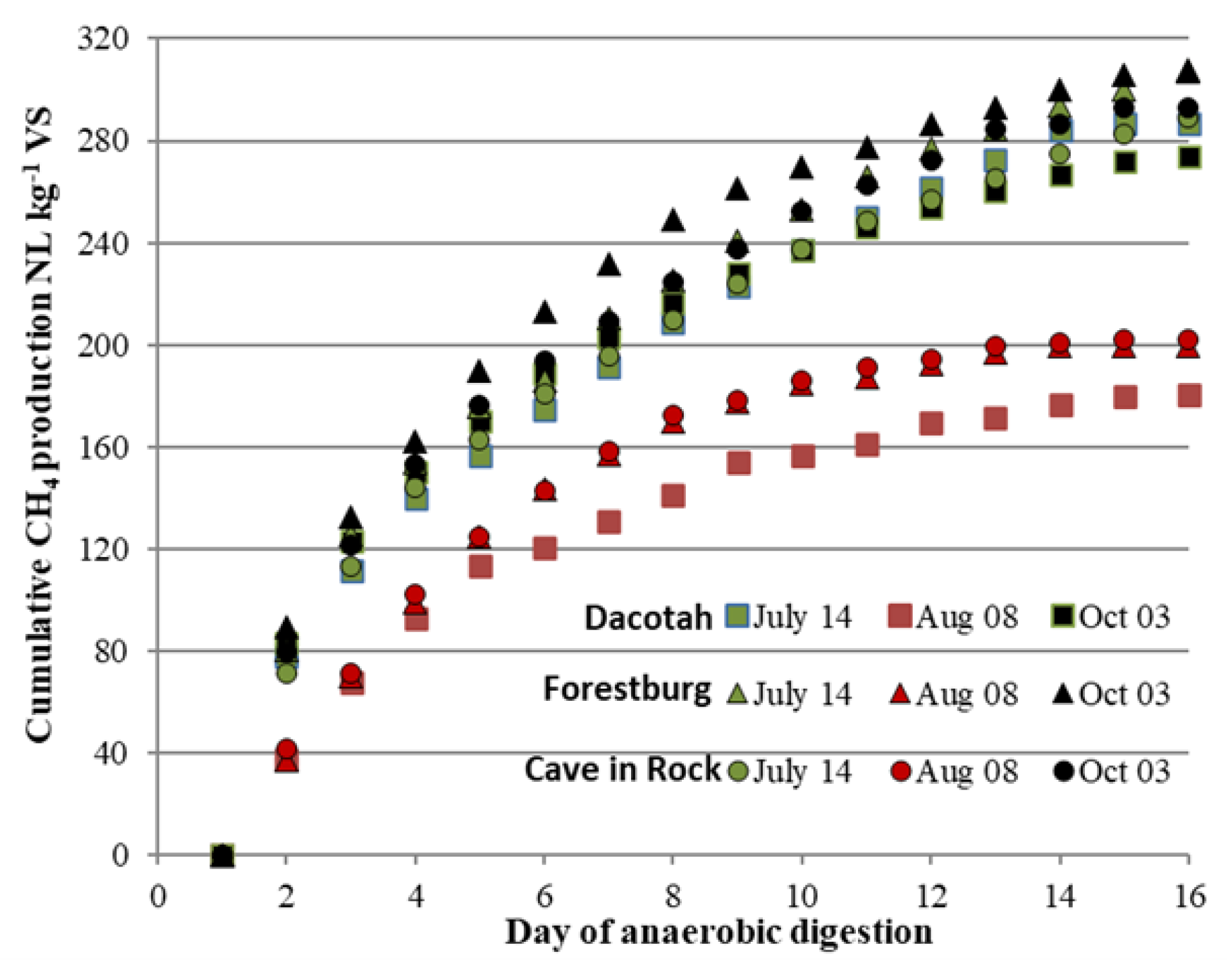

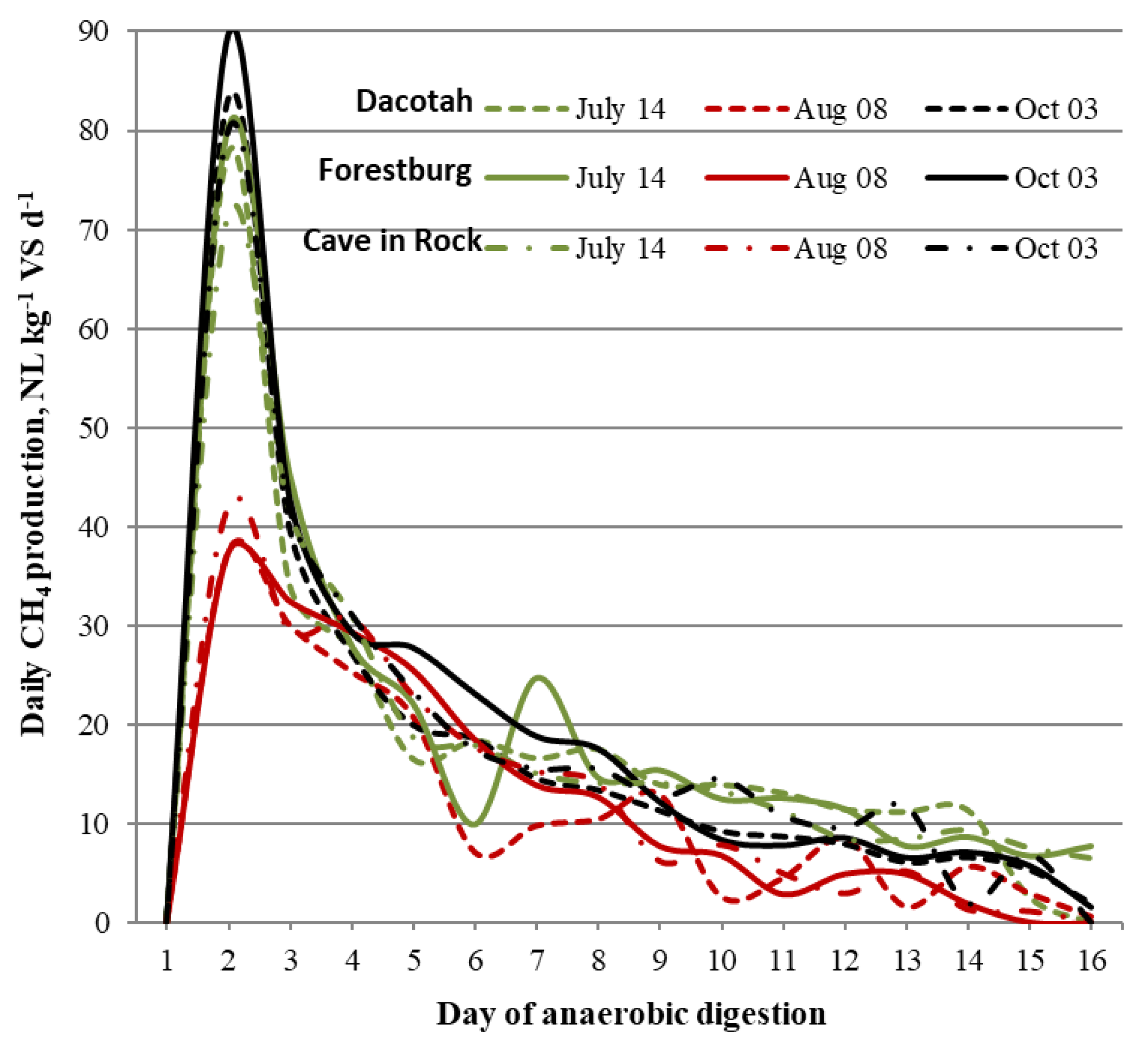

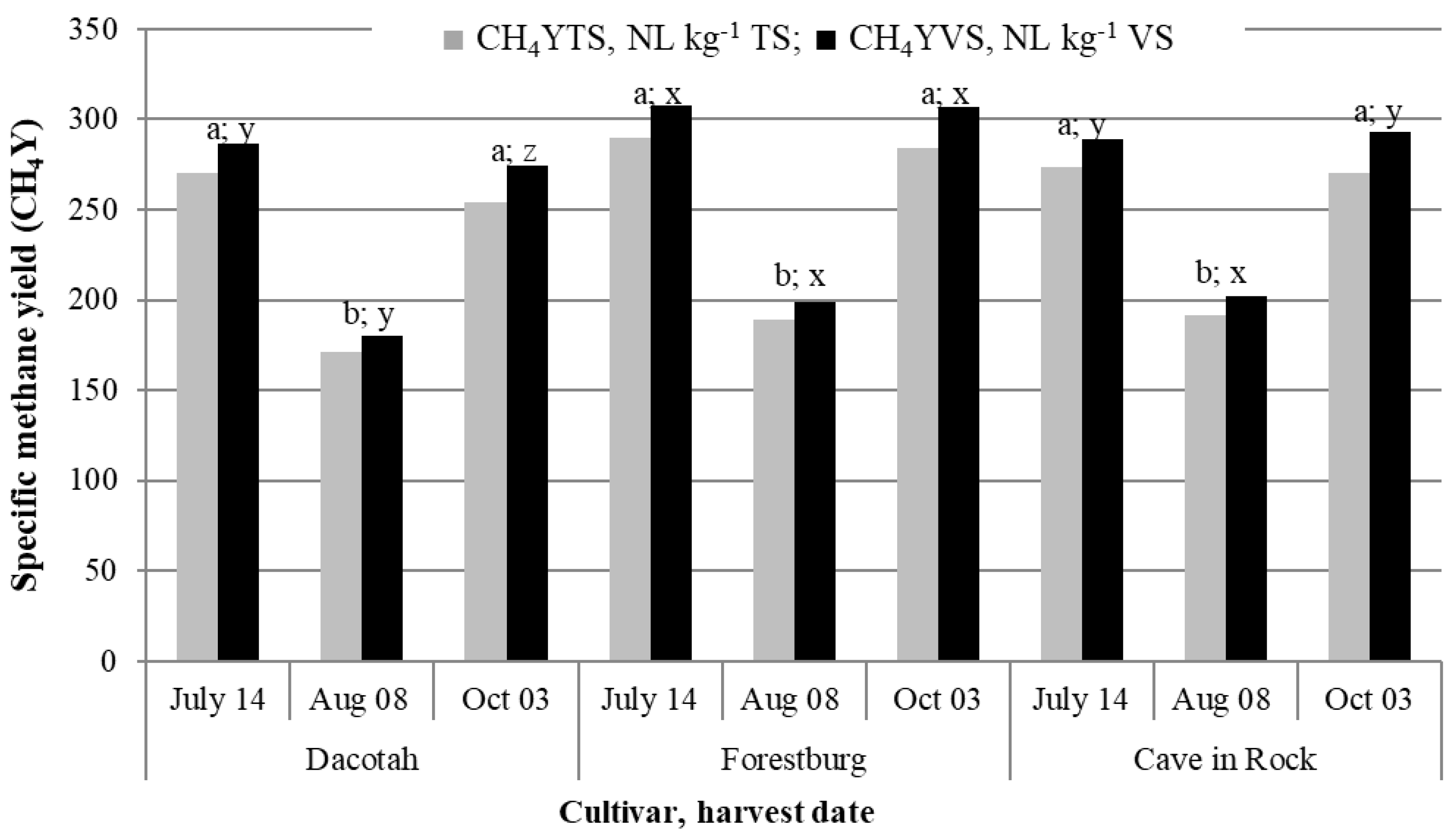

3.2. Cumulative and Area Specific Methane Yield

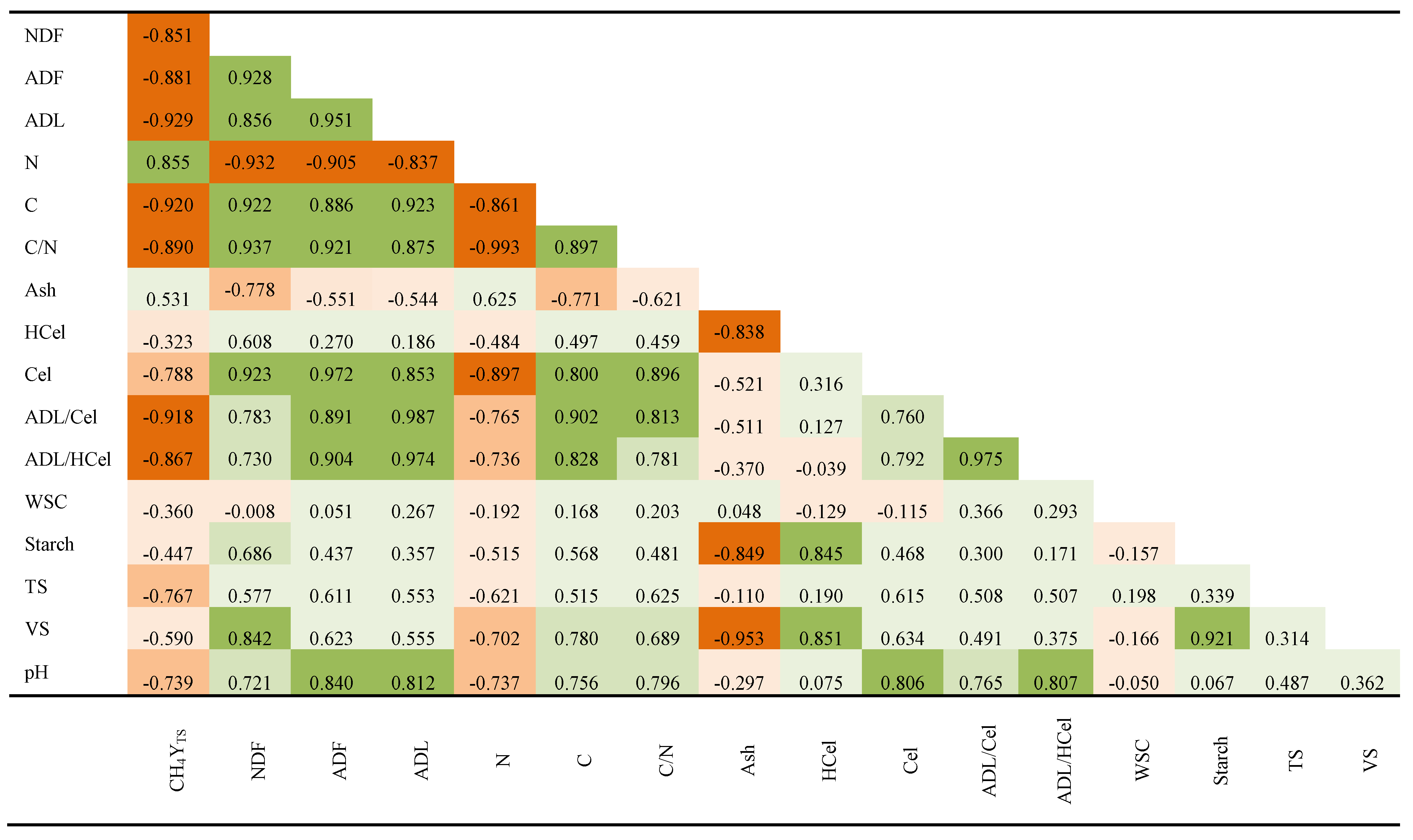

3.3. Association Between Biomass Composition and Specific Methane Yield

3.4. Area specific Methane and Energy Yield

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lewandowski, I. The Role of Perennial Biomass Crops in a Growing Bioeconomy. In Perennial Biomass Crops for a Resource-Constrained World; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Orlando, S.; Greco, C.; Tuttolomondo, T.; Leto, C.; Cammalleri, I.; La Bella, S. Identification of Energy Hubs for the Exploitation of Residual Biomass in an Area of Western Sicily. 2017, 10.5071/25thEUBCE2017-1AO.7.5.

- Attard, G.; Comparetti, A.; Febo, P.; Greco, C.; Mammano, M.; Orlando, S. Case Study of Potential Production of Renewable Energy Sources (RES) from Livestock Wastes in Mediterranean Islands. Chemical Engineering Transactions, 2017, 58, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comparetti, A.; Febo, P.; Greco, C.; Navickas, K.; Nekrosius, A.; Orlando, S.; Venslauskas, K. ASSESSMENT OF ORGANIC WASTE MANAGEMENT METHODS THROUGH ENERGY BALANCE. American Journal of Applied Sciences, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wit, M.; Faaij, A. European biomass resource potential and costs. Biomass and Bioenergy 2010, 34, 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadžiulienė, Ž.; Tilvikienė, V.; Liaudanskienė, I.; Pocienė, L.; Černiauskienė, Ž.; Zvicevicius, E.; Raila, A. Artemisia dubia growth, yield and biomass characteristics for combustion. Zemdirbyste 2017, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comparetti, A.; Greco, C.; Navickas, K.; Orlando, S.; Venslauskas, K. Life Cycle Impact Assessment applied to cactus pear crop production for generating bioenergy and biofertiliser. Riv. DI Stud. SULLA SOSTENIBILITA’ 2020, 11, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popp, D.; von Gillhaussen, P.; Weidlich, E.W.A.; Sträuber, H.; Harms, H.; Temperton, V.M. Methane yield of biomass from extensive grassland is affected by compositional changes induced by order of arrival. GCB Bioenergy 2017, 9, 1555–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolan, S.; Padhye, L.P.; Jasemizad, T.; Govarthanan, M.; Karmegam, N.; Wijesekara, H.; Amarasiri, D.; Hou, D.; Zhou, P.; Biswal, B.K.; et al. Impacts of climate change on the fate of contaminants through extreme weather events. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 909, 168388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, A.M.; Brown, R.A.; Rosenberg, N.J.; Izaurralde, R.C.; Benson, V. Climate Change Impacts for the Conterminous USA: An Integrated Assessment. Clim. Change 2005, 69, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheffield, J.; Wood, E.F. Projected changes in drought occurrence under future global warming from multi-model, multi-scenario, IPCC AR4 simulations. Clim. Dyn. 2008, 31, 79–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendramini, J.M.B.; Silveira, M.L.; Moriel, P. Resilience of warm-season (C4) perennial grasses under challenging environmental and management conditions. Anim. Front. 2023, 13, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrt, C.S.; Grof, C.P.L.; Furbank, R.T. C4 Plants as Biofuel Feedstocks: Optimising Biomass Production and Feedstock Quality from a Lignocellulosic PerspectiveFree Access. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2011, 53, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouton, J. Improvement of Switchgrass as a Bioenergy Crop. In Genetic Improvement of Bioenergy Crops; Springer New York: New York, NY; pp. 309–345.

- Liu, L.; Basso, B. Spatial evaluation of switchgrass productivity under historical and future climate scenarios in Michigan. GCB Bioenergy 2017, 9, 1320–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, R.; Mani, S.; Boddey, R.; Sokhansanj, S.; Quesada, D.; Urquiaga, S.; Reis, V.; Ho Lem, C. The Potential of C 4 Perennial Grasses for Developing a Global BIOHEAT Industry. CRC. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2005, 24, 461–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.N.; Mann, J.J.; Kyser, G.B.; Blumwald, E.; Van Deynze, A.; DiTomaso, J.M. Tolerance of switchgrass to extreme soil moisture stress: Ecological implications. Plant Sci. 2009, 177, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, D.J.; Fike, J.H. The Biology and Agronomy of Switchgrass for Biofuels. CRC. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2005, 24, 423–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, S.M.; Stahlheber, K.A.; Gross, K.L. Drought minimized nitrogen fertilization effects on bioenergy feedstock quality. Biomass and Bioenergy 2020, 133, 105452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeets, E.M.W.; Lewandowski, I.M.; Faaij, A.P.C. The economical and environmental performance of miscanthus and switchgrass production and supply chains in a European setting. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 1230–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, D.J.; Casler, M.D.; Monti, A. The Evolution of Switchgrass as an Energy Crop. In; 2012; pp. 1–28.

- Lemežienė, N.; Norkevičienė, E.; Liatukas, Ž.; Dabkevičienė, G.; Cecevičienė, J.; Butkutė, B. Switchgrass from North Dakota – an adaptable and promising energy crop for northern regions of Europe. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B — Soil Plant Sci. 2015, 65, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawatdeenarunat, C.; Surendra, K.C.; Takara, D.; Oechsner, H.; Khanal, S.K. Anaerobic digestion of lignocellulosic biomass: Challenges and opportunities. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 178, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campiotti, C.A.; Bibbiani, C.; Greco, C. Renewable energy for greenhouse agriculture. Qual. - Access to Success 2019, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Budzianowski, W.M. Sustainable biogas energy in Poland: Prospects and challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massé, D.; Gilbert, Y.; Savoie, P.; Bélanger, G.; Parent, G.; Babineau, D. Methane yield from switchgrass harvested at different stages of development in Eastern Canada. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 9536–9541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butkutė, B.; Lemežienė, N.; Kanapeckas, J.; Navickas, K.; Dabkevičius, Z.; Venslauskas, K. Cocksfoot, tall fescue and reed canary grass: Dry matter yield, chemical composition and biomass convertibility to methane. Biomass and Bioenergy 2014, 66, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandel, T.P.; Sutaryo, S.; Møller, H.B.; Jørgensen, U.; Lærke, P.E. Chemical composition and methane yield of reed canary grass as influenced by harvesting time and harvest frequency. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 130, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandel, T.P.; Gislum, R.; Jørgensen, U.; Lærke, P.E. Prediction of biogas yield and its kinetics in reed canary grass using near infrared reflectance spectroscopy and chemometrics. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 146, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickeduisberg, M.; Laser, H.; Tonn, B.; Isselstein, J. Tall wheatgrass ( Agropyron elongatum ) for biogas production: Crop management more important for biomass and methane yield than grass provenance. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 97, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, M.; Oechsner, H.; Koch, S.; Seggl, A.; Hrenn, H.; Schmiedchen, B.; Wilde, P.; Miedaner, T. Impact of genotype, harvest time and chemical composition on the methane yield of winter rye for biogas production. Biomass and Bioenergy 2011, 35, 4316–4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleszek, M.; Król, A.; Tys, J.; Matyka, M.; Kulik, M. Comparison of biogas production from wild and cultivated varieties of reed canary grass. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 156, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandikas, V.; Heuwinkel, H.; Lichti, F.; Drewes, J.E.; Koch, K. Correlation between biogas yield and chemical composition of energy crops. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 174, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, C.; Idler, C.; Heiermann, M. Biogas crops grown in energy crop rotations: Linking chemical composition and methane production characteristics. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 206, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Weijde, T.; Kiesel, A.; Iqbal, Y.; Muylle, H.; Dolstra, O.; Visser, R.G.F.; Lewandowski, I.; Trindade, L.M. Evaluation of Miscanthus sinensis biomass quality as feedstock for conversion into different bioenergy products. GCB Bioenergy 2017, 9, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, G.; Mårtensson, L.; Prade, T.; Svensson, S.; Jensen, E.S. Perennial species mixtures for multifunctional production of biomass on marginal land. GCB Bioenergy 2017, 9, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 11277 (2020). Soil quality — Determination of particle size distribution in mineral soil material — Method by sieving and sedimentation. 2020.

- Metzger M., J. , Shkaruba A. D., Jongman R. H. G., B.R.G.H. Descriptions of the European environmental zones and strata, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mulkey, V.R.; Owens, V.N.; Lee, D.K. Management of Switchgrass-Dominated Conservation Reserve Program Lands for Biomass Production in South Dakota. Crop Sci. 2006, 46, 712–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norkevičienė, E.; Lemežienė, N.; Cesevičienė, J.; Butkutė, B. Switchgrass ( Panicum virgatum L.) from North Dakota—a New Bioenergy Crop for the Nemoral Zone of Europe. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2016, 47, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Soest, P.J.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for Dietary Fiber, Neutral Detergent Fiber, and Nonstarch Polysaccharides in Relation to Animal Nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.; MacKown, C.T.; Starks, P.J.; Kindiger, B.K. Rapid Analysis of Nonstructural Carbohydrate Components in Grass Forage Using Microplate Enzymatic Assays. Crop Sci. 2010, 50, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badshah, M.; Lam, D.M.; Liu, J.; Mattiasson, B. Use of an Automatic Methane Potential Test System for evaluating the biomethane potential of sugarcane bagasse after different treatments. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 114, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strömberg, S.; Nistor, M.; Liu, J. Towards eliminating systematic errors caused by the experimental conditions in Biochemical Methane Potential (BMP) tests. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 1939–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidaki, I.; Alves, M.; Bolzonella, D.; Borzacconi, L.; Campos, J.L.; Guwy, A.J.; Kalyuzhnyi, S.; Jenicek, P.; van Lier, J.B. Defining the biomethane potential (BMP) of solid organic wastes and energy crops: a proposed protocol for batch assays. Water Sci. Technol. 2009, 59, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldheim, L. and T.N. Heating Value of Gases from Biomass Gasification. TPS01/16. IEA Bioenergy Agreement Subcommittee on Thermal Gasification of Biomass, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bélanger, G.; Savoie, P.; Parent, G.; Claessens, A.; Bertrand, A.; Tremblay, G.F.; Massé, D.; Gilbert, Y.; Babineau, D. Switchgrass silage for methane production as affected by date of harvest. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2012, 92, 1187–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richner, J.M.; Kallenbach, R.L.; Roberts, C.A. Dual Use Switchgrass: Managing Switchgrass for Biomass Production and Summer Forage. Agron. J. 2014, 106, 1438–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nges, I.A.; Wang, B.; Cui, Z.; Liu, J. Digestate liquor recycle in minimal nutrients-supplemented anaerobic digestion of wheat straw. Biochem. Eng. J. 2015, 94, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.A.; Fike, J.H.; Galbraith, J.M.; Fike, W.B.; Parrish, D.J.; Evanylo, G.K.; Strahm, B.D. Effects of harvest frequency and biosolids application on switchgrass yield, feedstock quality, and theoretical ethanol yield. GCB Bioenergy 2015, 7, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurangzaib, M.; Moore, K.J.; Archontoulis, S. V.; Heaton, E.A.; Lenssen, A.W.; Fei, S. Compositional differences among upland and lowland switchgrass ecotypes grown as a bioenergy feedstock crop. Biomass and Bioenergy 2016, 87, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casler, M.D.; Boe, A.R. Cultivar × Environment Interactions in Switchgrass. Crop Sci. 2003, 43, 2226–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guretzky, J.A.; Biermacher, J.T.; Cook, B.J.; Kering, M.K.; Mosali, J. Switchgrass for forage and bioenergy: harvest and nitrogen rate effects on biomass yields and nutrient composition. Plant Soil 2011, 339, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, D.W.; Bates, G.E.; Keyser, P.D.; Allen, F.L.; Harper, C.A.; Waller, J.C.; Birckhead, J.L.; Backus, W.M. Forage Harvest Timing Impact on Biomass Quality from Native Warm-Season Grass Mixtures. Agron. J. 2016, 108, 1524–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.; Fritz, J.; Moore, K.; Moser, L.; Vogel, K.; Redfearn, D.; Wester, D. Predicting Forage Quality in Switchgrass and Big Bluestem. Agron. J. 2001, 93, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HEATON, E.A.; DOHLEMAN, F.G.; LONG, S.P. Seasonal nitrogen dynamics of Miscanthus × giganteus and Panicum virgatum. GCB Bioenergy 2009, 1, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, A.B.; Berdahl, J.D.; Hanson, J.D.; Liebig, M.A.; Johnson, H.A. Biomass and Carbon Partitioning in Switchgrass. Crop Sci. 2004, 44, 1391–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butkutė, B.; Lemežienė, N.; Cesevičienė, J.; Liatukas, Ž.; Dabkevičienė, G. Carbohydrate and lignin partitioning in switchgrass biomass (Panicum virgatum L.) as a bioenergy feedstock. Zemdirbyste-Agriculture 2013, 100, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butkutė, B.; Cesevičienė, J.; Lemežienė, N.; Norkevičienė, E.; Dabkevičienė, G.; Liatukas, Ž. The Variation of Ash and Inorganic Elements Concentrations in the Biomass of Lithuania-Grown Switchgrass (Panicum Virgatum L.). In Renewable Energy in the Service of Mankind Vol I; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; pp. 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghpour, A.; Gorlitsky, L.E.; Hashemi, M.; Weis, S.A.; Herbert, S.J. Response of Switchgrass Yield and Quality to Harvest Season and Nitrogen Fertilizer. Agron. J. 2014, 106, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, K.A. Forage and pasture management for laminitic horses. Clin. Tech. Equine Pract. 2004, 3, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H.K.; Smith, M.C.; Kondrad, S.L.; White, J.W. Evaluation of Biogas Production Potential by Dry Anaerobic Digestion of Switchgrass–Animal Manure Mixtures. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2010, 160, 965–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dandikas, V.; Heuwinkel, H.; Lichti, F.; Drewes, J.E.; Koch, K. Predicting methane yield by linear regression models: A validation study for grassland biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 265, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luna-delRisco, M.; Normak, A.; Orupõld, K. Biochemical methane potential of different organic wastes and energy crops from Estonia. Agron. Res. 2011, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Barbanti, L.; Di Girolamo, G.; Grigatti, M.; Bertin, L.; Ciavatta, C. Anaerobic digestion of annual and multi-annual biomass crops. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 56, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragaglini, G.; Dragoni, F.; Simone, M.; Bonari, E. Suitability of giant reed (Arundo donax L.) for anaerobic digestion: Effect of harvest time and frequency on the biomethane yield potential. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 152, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mashad, H.M. Kinetics of methane production from the codigestion of switchgrass and Spirulina platensis algae. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigon, J.C.; Roy, C.; Guiot, S.R. Anaerobic co-digestion of dairy manure with mulched switchgrass for improvement of the methane yield. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2012, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackowiak, D.; Frigon, J.C.; Ribeiro, T.; Pauss, A.; Guiot, S. Enhancing solubilisation and methane production kinetic of switchgrass by microwave pretreatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capecchi, L.; Galbe, M.; Wallberg, O.; Mattarelli, P.; Barbanti, L. Combined ethanol and methane production from switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) impregnated with lime prior to steam explosion. Biomass and Bioenergy 2016, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butkute, B.; Lemežiene, N.; Kanapeckas, J.; Navickas, K.; Dabkevičius, Z.; Venslauskas, K. Cocksfoot, tall fescue and reed canary grass: Dry matter yield, chemical composition and biomass convertibility to methane. Biomass and Bioenergy 2014, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Li, C.; Liu, J.; Yi, Z.; Han, Y. Changes in composition, cellulose degradability and biochemical methane potential of Miscanthus species during the growing season. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 235, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaducci, S.; Perego, A. Field evaluation of Arundo donax clones for bioenergy production. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 75, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seppälä, M.; Paavola, T.; Lehtomäki, A.; Rintala, J. Biogas production from boreal herbaceous grasses – Specific methane yield and methane yield per hectare. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 2952–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butkutė, B.; Lemežienė, N.; Kanapeckas, J.; Navickas, K.; Dabkevičius, Z.; Venslauskas, K. Cocksfoot, tall fescue and reed canary grass: Dry matter yield, chemical composition and biomass convertibility to methane. Biomass and Bioenergy 2014, 66, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilvikiene, V.; Kadziuliene, Z.; Dabkevicius, Z.; Venslauskas, K.; Navickas, K. Feasibility of tall fescue, cocksfoot and reed canary grass for anaerobic digestion: Analysis of productivity and energy potential. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 84, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandel, T.P.; Ward, A.J.; Elsgaard, L.; Møller, H.B.; Lærke, P.E. Methane yield from anaerobic digestion of festulolium and tall fescue cultivated on a fen peatland under different harvest managements. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B — Soil Plant Sci. 2017, 67, 670–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, Y.; Sun, S.; Qiao, W.; Xiao, M. Effect of biological pretreatments in enhancing corn straw biogas production. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 11177–11182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalak, J.; Kasprzycka, A.; Martyniak, D.; Tys, J. Effect of biological pretreatment of Agropyron elongatum ‘BAMAR’ on biogas production by anaerobic digestion. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 200, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinuccio, E.; Balsari, P.; Gioelli, F.; Menardo, S. Evaluation of the biogas productivity potential of some Italian agro-industrial biomasses. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 3780–3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Yang, G.; Feng, Y.; Ren, G.; Han, X. Optimizing feeding composition and carbon–nitrogen ratios for improved methane yield during anaerobic co-digestion of dairy, chicken manure and wheat straw. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 120, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triolo, J.M.; Sommer, S.G.; Møller, H.B.; Weisbjerg, M.R.; Jiang, X.Y. A new algorithm to characterize biodegradability of biomass during anaerobic digestion: Influence of lignin concentration on methane production potential. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 9395–9402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Year | Soil property | ||||||

| Corg. | N-NO3 | N-NH4 | K2O | P2O5 | S | pHKCl | |

| g kg-1 | mg kg-1 | ||||||

| Before establishment of experiment in 2014 | 21.3 | 7.60 | 1.80 | 158 | 196 | 2.5 | 6.8 |

| After the investigation in 2016 | 23.1 | 4.29 | 1.59 | 162 | 154 | 1.7 | 6.9 |

| Harvest regime | Cut | Harvest date | Growth stage | ||

| ‘Dacotah’ | ‘Foresburg’ | ‘Cave in Rock’ | |||

| I | First | July 13 | Heading | Heading | Booting |

| Second | October 06 | Regrowth of aftermath | |||

| II | First | August 08 | Flowering | Flowering | Heading |

| Second | October 06 | Regrowth of aftermath | |||

| Cultivar | Harvestdate | NDF | ADF | ADL | WSC | Starch | Ash | N | C | Cel | HCel | C/N | ADL/Cel | ADL/HCel | Silage characteristics | ||

| g kg-1 DM | pH | TS,% WM | VS,% TS | ||||||||||||||

| Dacotah | July 14 | 697 b; x | 418 b; x | 62.4 b; x | 65.9 b; y | 91.7 a; x | 52.3 b; x | 10.30 a; x | 481 b; x | 356 | 279 | 46.7 b; x | 0.175 | 0.223 | 4.2 | 32.8 | 94.3 |

| Aug 08 | 736 a; y | 440 a; y | 74.3 a; y | 95.0 a; x | 99.5 a; x | 49.3 c; x | 7.79 b; x | 486 a; y | 366 | 296 | 62.4 a; y | 0.203 | 0.251 | 4.4 | 42.4 | 94.9 | |

| Oct 03 | 666 c; x | 405 b; x | 58.6 c; x | 70.1 b; z | 60.6 b; x | 66.9 a; x | 11.10 a; x | 480 b; x | 346 | 261 | 43.4 b; y | 0.169 | 0.224 | 4.4 | 37.2 | 92.6 | |

| Forestburg | July 14 | 694 b; x | 400 b; y | 51.4 b; y | 61.5 c; y | 80.5 a; y | 51.9 b; x | 10.30 a; x | 481 b; x | 349 | 294 | 46.7 c; x | 0.147 | 0.175 | 4.2 | 31.9 | 94.1 |

| Aug 08 | 745 a; x | 457 a; x | 79.7 a; x | 72.5 b; z | 80.7 a; y | 49.0 c; x | 7.18 c; y | 488 a; x | 377 | 288 | 67.9 a; x | 0.211 | 0.277 | 5.1 | 37.4 | 94.9 | |

| Oct 03 | 669 c; x | 402 b; x | 53.3 b; y | 86.5 a; y | 58.8 b; x | 67.0 a; x | 9.60 b; y | 478 c; y | 349 | 267 | 49.8 b; x | 0.153 | 0.200 | 4.2 | 34.6 | 92.4 | |

| Cave inRock | July 14 | 679 b; y | 384 b; z | 50.6 c; y | 79.7 c; x | 90.8 a; x | 49.1 b; y | 10.20 b; x | 482 b; x | 334 | 294 | 47.2 b; x | 0.152 | 0.172 | 4.0 | 32.4 | 94.7 |

| Aug 08 | 734 a; y | 454 a; x | 83.3 a; x | 89.6 b; y | 82.7 b; y | 45.7 c; y | 7.76 c; x | 488 a; x | 371 | 280 | 62.9 a; y | 0.225 | 0.298 | 4.6 | 34.5 | 94.8 | |

| Oct 03 | 654 c; y | 385 b; y | 57.8 b; x | 98.4 a; x | 55.4 c; x | 61.2 a; y | 11.40 a; x | 480 b; x | 328 | 269 | 42.1 c; y | 0.176 | 0.215 | 4.2 | 30.8 | 92.3 | |

| Day of BMP assay | CH4, % CH4YVS | ||||||||

| Dacotah | Forestburg | Cave in Rock | |||||||

| July 14 | Aug 08 | Oct 03 | July 14 | Aug 08 | Oct 03 | July 14 | Aug 08 | Oct 03 | |

| 2nd | 27.1 | 20.8 | 30.4 | 26.1 | 18.7 | 29.2 | 24.7 | 20.8 | 27.3 |

| 3rd | 11.9 | 16.6 | 14.5 | 14.7 | 16.3 | 14.0 | 14.4 | 14.6 | 14.2 |

| 2nd+3rd | 39.0 | 37.4 | 44.9 | 40.8 | 35.0 | 43.1 | 39.1 | 35.4 | 41.5 |

| 4th | 9.77 | 14.1 | 10.0 | 9.11 | 14.7 | 9.57 | 10.8 | 15.2 | 10.6 |

| 2nd+3rd+4th | 48.8 | 51.4 | 54.8 | 49.9 | 49.8 | 52.7 | 49.8 | 50.6 | 52.2 |

| Cultivar | Harvest date of the first cut (Harvest regime) | CH4YTS, Nm3 ha-1 from biomass of | HHVY GJ ha-1 | LHVY GJ ha-1 | ||

| first cut | second cut | annual | annual | annual | ||

| Dacotah | July 14 (I) | 862 | 266 | 1128 | 44.9 | 40.4 |

| Aug 08 (II) | 828 | 59† | 888 | 35.3 | 31.8 | |

| Average | 845 | 163 | 1008 | 40.1 | 36.1 | |

| Forestburg | July 14 (I) | 1211 | 522 | 1732 | 68.9 | 62.0 |

| Aug 08 (II) | 1247 | 85† | 1332 | 53.0 | 47.7 | |

| Average | 1229 | 304 | 1532 | 61.0 | 54.9 | |

| Cave in Rock | July 14 (I) | 1148 | 752 | 1900 | 75.6 | 68.0 |

| Aug 08 (II) | 1004 | 206† | 1210 | 48.2 | 43.3 | |

| Average | 1076 | 479 | 1555 | 61.9 | 55.7 | |

| Average for three cultivars | July 14 (I) | 1074 | 514 | 1587 | 63.2 | 56.8 |

| Aug 08 (II) | 1026 | 117 | 1143 | 45.5 | 40.9 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).