Submitted:

08 May 2025

Posted:

09 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

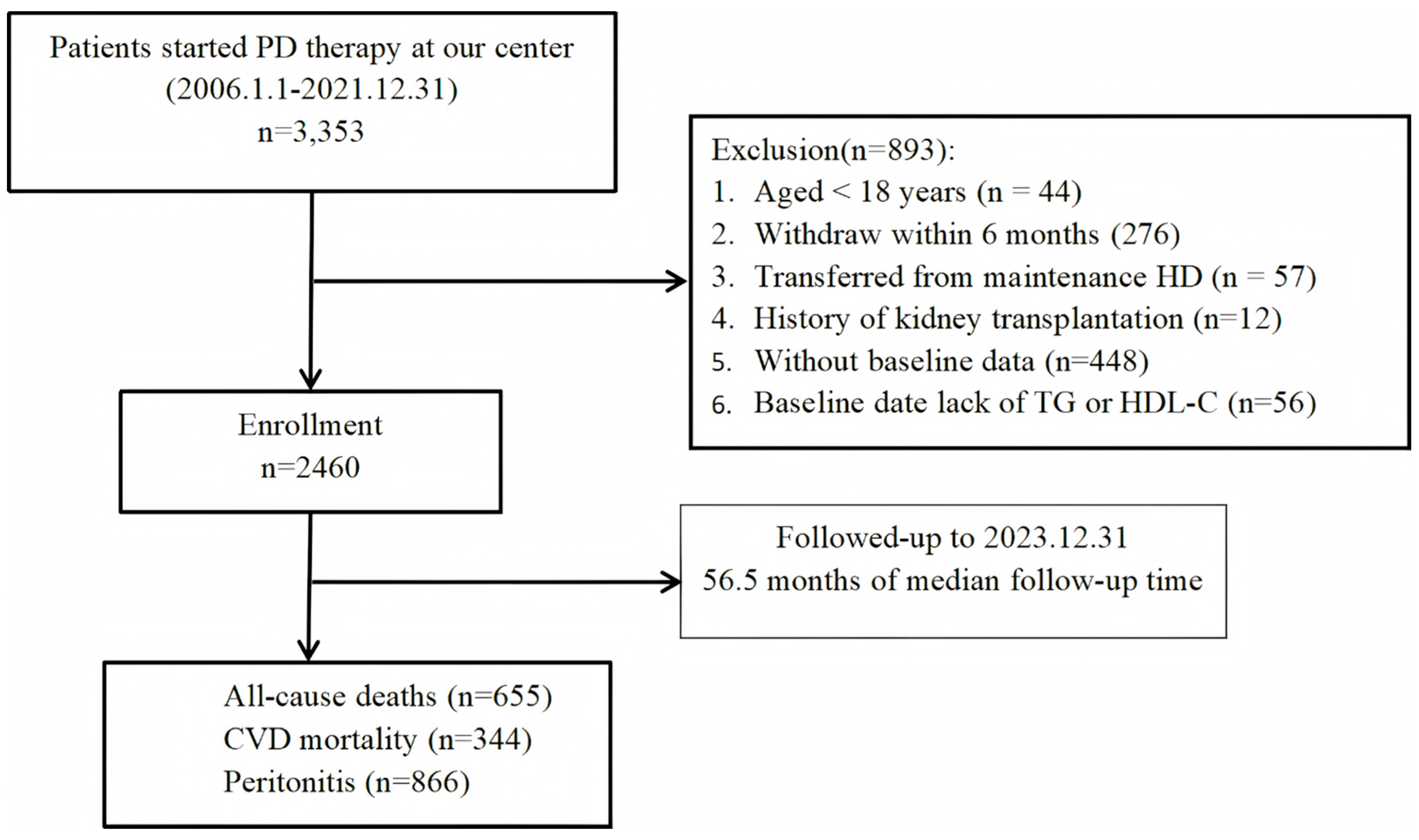

2.1. Population

2.2. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics and Baseline Laboratory Data

2.3. Outcomes and Definitions

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population and Baseline Characteristics Classified by Baseline AIP

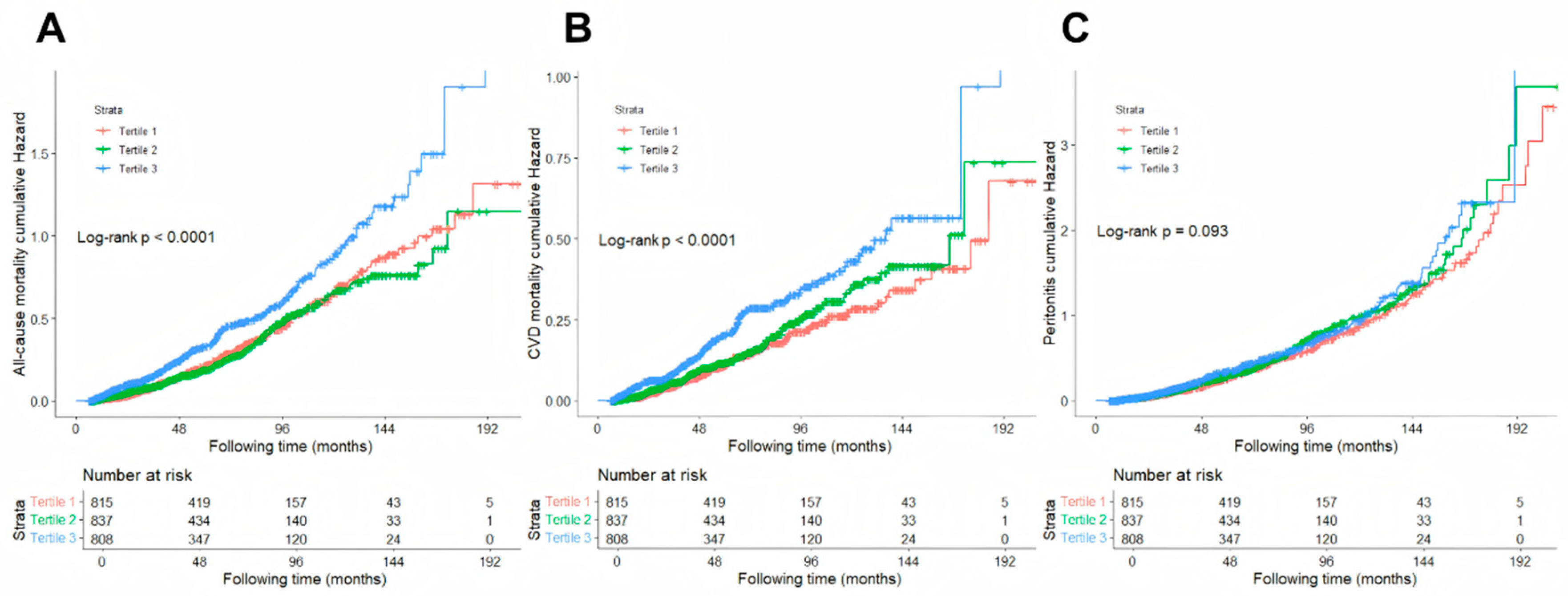

3.2. Associations of AIP with All-Cause and CVD Mortality

3.3. Associations of AIP and PD-Related Peritonitis in PD Patients

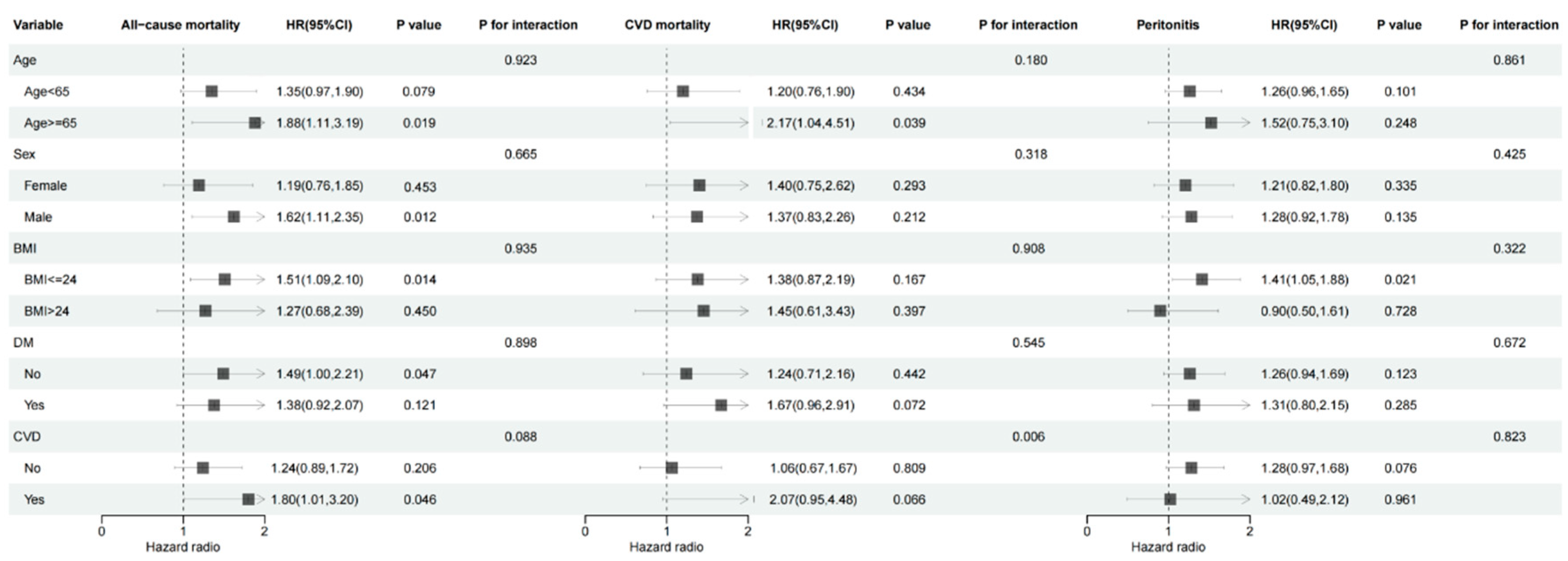

3.4. Subgroup Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Funding

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

- AIP, atherogenic index of plasma;

- PD, peritoneal dialysis;

- CKD, chronic kidney diseases;

- HD, hemodialysis;

- CVD, cardiovascular disease;

- LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol;

- TG, triglyceride;

- HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol;

- BMI, body mass index;

- ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor;

- ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker;

- TC, total cholesterol;

- Hb, hemoglobin;

- ALB, serum albumin;

- Scr, serum creatinine;

- BUN, blood urea nitrogen;

- UA, uric acid;

- iPTH, intact parathyroid hormone;

- eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate;

- MACEs, major adverse cardiovascular events;

- PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention;

- RAAS, Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System;

- SdLDL, small and dense LDL;

- ESRD, end stage renal disease;

- ROS, reactive oxygen species;

- IR, insulin resistance;

- Ang II, angiotensin II;

- TGF-β1, transforming growth factor-beta.

References

- MIKOLASEVIC I, ŽUTELIJA M, MAVRINAC V, et al. Dyslipidemia in patients with chronic kidney disease: etiology and management [J]. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis, 2017, 10: 35-45. [CrossRef]

- BERBERICH A J, HEGELE R A. A Modern Approach to Dyslipidemia [J]. Endocr Rev, 2022, 43(4): 611-53. [CrossRef]

- FENG X, ZHAN X, WEN Y, et al. Hyperlipidemia and mortality in patients on peritoneal dialysis [J]. BMC Nephrol, 2022, 23(1): 342. [CrossRef]

- HUANG Y J, JIANG Z P, ZHOU J F, et al. Hypertriglyceridemia is a risk factor for treatment failure in patients with peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis [J]. Int Urol Nephrol, 2022, 54(7): 1583-9. [CrossRef]

- STEPANOVA N, BURDEYNA O. Association between Dyslipidemia and Peritoneal Dialysis Technique Survival [J]. Open Access Maced J Med Sci, 2019, 7(15): 2467-73. [CrossRef]

- HONDA Y, MARUYAMA Y, NAKAMURA M, et al. Association between lipid profile and residual renal function in incident peritoneal dialysis patients [J]. Ther Apher Dial, 2022, 26(6): 1235-40. [CrossRef]

- WON K B, HEO R, PARK H B, et al. Atherogenic index of plasma and the risk of rapid progression of coronary atherosclerosis beyond traditional risk factors [J]. Atherosclerosis, 2021, 324: 46-51. [CrossRef]

- KIM S H, CHO Y K, KIM Y J, et al. Association of the atherogenic index of plasma with cardiovascular risk beyond the traditional risk factors: a nationwide population-based cohort study [J]. Cardiovasc Diabetol, 2022, 21(1): 81. [CrossRef]

- ZHANG Y, CHEN S, TIAN X, et al. Association between cumulative atherogenic index of plasma exposure and risk of myocardial infarction in the general population [J]. Cardiovasc Diabetol, 2023, 22(1): 210. [CrossRef]

- ZHENG H, WU K, WU W, et al. Relationship between the cumulative exposure to atherogenic index of plasma and ischemic stroke: a retrospective cohort study [J]. Cardiovasc Diabetol, 2023, 22(1): 313. [CrossRef]

- NAM J S, KIM M K, PARK K, et al. The Plasma Atherogenic Index is an Independent Predictor of Arterial Stiffness in Healthy Koreans [J]. Angiology, 2022, 73(6): 514-9. [CrossRef]

- HUANG Q, LIU Z, WEI M, et al. The atherogenic index of plasma and carotid atherosclerosis in a community population: a population-based cohort study in China [J]. Cardiovasc Diabetol, 2023, 22(1): 125. [CrossRef]

- YOU F F, GAO J, GAO Y N, et al. Association between atherogenic index of plasma and all-cause mortality and specific-mortality: a nationwide population-based cohort study [J]. Cardiovasc Diabetol, 2024, 23(1): 276. [CrossRef]

- DUIYIMUHAN G, MAIMAITI N. The association between atherogenic index of plasma and all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease-specific mortality in hypertension patients: a retrospective cohort study of NHANES [J]. BMC Cardiovasc Disord, 2023, 23(1): 452. [CrossRef]

- LEE M J, PARK J T, HAN S H, et al. The atherogenic index of plasma and the risk of mortality in incident dialysis patients: Results from a nationwide prospective cohort in Korea [J]. PLoS One, 2017, 12(5): e0177499. [CrossRef]

- HU Y, YANG L, SUN Z, et al. The association between the atherogenic index of plasma and all-cause mortality in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis: a multicenter cohort study [J]. Lipids Health Dis, 2025, 24(1): 91. [CrossRef]

- MA L, SUN F, ZHU K, et al. The Predictive Value of Atherogenic Index of Plasma, Non- High Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (Non-HDL-C), Non-HDL-C/HDL-C, and Lipoprotein Combine Index for Stroke Incidence and Prognosis in Maintenance Hemodialysis Patients [J]. Clin Interv Aging, 2024, 19: 1235-45. [CrossRef]

- PENG Y, SHUAI D, YANG Y, et al. Higher atherogenic index of plasma is associated with intradialytic hypotension: a multicenter cross-sectional study [J]. Ren Fail, 2024, 46(2): 2407885. [CrossRef]

- LEVEY A S, STEVENS L A. Estimating GFR using the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) creatinine equation: more accurate GFR estimates, lower CKD prevalence estimates, and better risk predictions [J]. Am J Kidney Dis, 2010, 55(4): 622-7. [CrossRef]

- LIU R, PENG Y, WU H, et al. Uric acid to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio predicts cardiovascular mortality in patients on peritoneal dialysis [J]. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis, 2021, 31(2): 561-9. [CrossRef]

- LI P K, CHOW K M, CHO Y, et al. ISPD peritonitis guideline recommendations: 2022 update on prevention and treatment [J]. Perit Dial Int, 2022, 42(2): 110-53. [CrossRef]

- EDWARDS M K, BLAHA M J, LOPRINZI P D. Atherogenic Index of Plasma and Triglyceride/High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Ratio Predict Mortality Risk Better Than Individual Cholesterol Risk Factors, Among an Older Adult Population [J]. Mayo Clin Proc, 2017, 92(4): 680-1. [CrossRef]

- GUO Q, ZHOU S, FENG X, et al. The sensibility of the new blood lipid indicator--atherogenic index of plasma (AIP) in menopausal women with coronary artery disease [J]. Lipids Health Dis, 2020, 19(1): 27. [CrossRef]

- ÇELIK E, ÇORA A R, KARADEM K B. The Effect of Untraditional Lipid Parameters in the Development of Coronary Artery Disease: Atherogenic Index of Plasma, Atherogenic Coefficient and Lipoprotein Combined Index [J]. J Saudi Heart Assoc, 2021, 33(3): 244-50. [CrossRef]

- TAO S, YU L, LI J, et al. Multiple triglyceride-derived metabolic indices and incident cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and coronary heart disease [J]. Cardiovasc Diabetol, 2024, 23(1): 359. [CrossRef]

- ZHI Y W, CHEN R G, ZHAO J W, et al. Association Between Atherogenic Index of Plasma and Risk of Incident Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events [J]. Int Heart J, 2024, 65(1): 39-46. [CrossRef]

- QIN Z, ZHOU K, LI Y, et al. The atherogenic index of plasma plays an important role in predicting the prognosis of type 2 diabetic subjects undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: results from an observational cohort study in China [J]. Cardiovasc Diabetol, 2020, 19(1): 23. [CrossRef]

- FU L, ZHOU Y, SUN J, et al. Atherogenic index of plasma is associated with major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus [J]. Cardiovasc Diabetol, 2021, 20(1): 201. [CrossRef]

- WANG Y, WANG S, SUN S, et al. The predictive value of atherogenic index of plasma for cardiovascular outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with LDL-C below 1.8mmol/L [J]. Cardiovasc Diabetol, 2023, 22(1): 150. [CrossRef]

- FROHLICH J, DOBIáSOVá M. Fractional esterification rate of cholesterol and ratio of triglycerides to HDL-cholesterol are powerful predictors of positive findings on coronary angiography [J]. Clin Chem, 2003, 49(11): 1873-80. [CrossRef]

- BENDZALA M, SABAKA P, CAPRNDA M, et al. Atherogenic index of plasma is positively associated with the risk of all-cause death in elderly women : A 10-year follow-up [J]. Wien Klin Wochenschr, 2017, 129(21-22): 793-8. [CrossRef]

- TAMOSIUNAS A, LUKSIENE D, KRANCIUKAITE-BUTYLKINIENE D, et al. Predictive importance of the visceral adiposity index and atherogenic index of plasma of all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged and elderly Lithuanian population [J]. Front Public Health, 2023, 11: 1150563. [CrossRef]

- NANSSEU J R, MOOR V J, NOUAGA M E, et al. Atherogenic index of plasma and risk of cardiovascular disease among Cameroonian postmenopausal women [J]. Lipids Health Dis, 2016, 15: 49. [CrossRef]

- HOLZER M, TRIEB M, KONYA V, et al. Aging affects high-density lipoprotein composition and function [J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2013, 1831(9): 1442-8. [CrossRef]

- PŁACZKOWSKA S, SOŁKIEWICZ K, BEDNARZ-MISA I, et al. Atherogenic Plasma Index or Non-High-Density Lipoproteins as Markers Best Reflecting Age-Related High Concentrations of Small Dense Low-Density Lipoproteins [J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2022, 23(9). [CrossRef]

- SER Ö S, KESKIN K, ÇETINKAL G, et al. Evaluation of the Atherogenic Index of Plasma to Predict All-Cause Mortality in Elderly With Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Long-Term Follow-Up [J]. Angiology, 2024: 33197241279587. [CrossRef]

- LI X, LU L, CHEN Y, et al. Association of atherogenic index of plasma trajectory with the incidence of cardiovascular disease over a 12-year follow-up: findings from the ELSA cohort study [J]. Cardiovasc Diabetol, 2025, 24(1): 124. [CrossRef]

- BJöRKEGREN J L M, LUSIS A J. Atherosclerosis: Recent developments [J]. Cell, 2022, 185(10): 1630-45. [CrossRef]

- HOLZER M, BIRNER-GRUENBERGER R, STOJAKOVIC T, et al. Uremia alters HDL composition and function [J]. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2011, 22(9): 1631-41. [CrossRef]

- KHATANA C, SAINI N K, CHAKRABARTI S, et al. Mechanistic Insights into the Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein-Induced Atherosclerosis [J]. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2020, 2020: 5245308. [CrossRef]

- LI Y W, KAO T W, CHANG P K, et al. Atherogenic index of plasma as predictors for metabolic syndrome, hypertension and diabetes mellitus in Taiwan citizens: a 9-year longitudinal study [J]. Sci Rep, 2021, 11(1): 9900. [CrossRef]

- PEDERSEN D J, GUILHERME A, DANAI L V, et al. A major role of insulin in promoting obesity-associated adipose tissue inflammation [J]. Mol Metab, 2015, 4(7): 507-18. [CrossRef]

- BJORNSTAD P, ECKEL R H. Pathogenesis of Lipid Disorders in Insulin Resistance: a Brief Review [J]. Curr Diab Rep, 2018, 18(12): 127. [CrossRef]

- DI BARTOLO B A, CARTLAND S P, GENNER S, et al. HDL Improves Cholesterol and Glucose Homeostasis and Reduces Atherosclerosis in Diabetes-Associated Atherosclerosis [J]. J Diabetes Res, 2021, 2021: 6668506. [CrossRef]

- LAMBIE M, BONOMINI M, DAVIES S J, et al. Insulin resistance in cardiovascular disease, uremia, and peritoneal dialysis [J]. Trends Endocrinol Metab, 2021, 32(9): 721-30. [CrossRef]

- TAN M H, JOHNS D, GLAZER N B. Pioglitazone reduces atherogenic index of plasma in patients with type 2 diabetes [J]. Clin Chem, 2004, 50(7): 1184-8. [CrossRef]

- KOU H, DENG J, GAO D, et al. Relationship among adiponectin, insulin resistance and atherosclerosis in non-diabetic hypertensive patients and healthy adults [J]. Clin Exp Hypertens, 2018, 40(7): 656-63. [CrossRef]

- ZHAO G, SHANG S, TIAN N, et al. Associations between different insulin resistance indices and the risk of all-cause mortality in peritoneal dialysis patients [J]. Lipids Health Dis, 2024, 23(1): 287. [CrossRef]

- LIPKE K, KUBIS-KUBIAK A, PIWOWAR A. Molecular Mechanism of Lipotoxicity as an Interesting Aspect in the Development of Pathological States-Current View of Knowledge [J]. Cells, 2022, 11(5). [CrossRef]

- STEPANOVA N. Dyslipidemia in Peritoneal Dialysis: Implications for Peritoneal Membrane Function and Patient Outcomes [J]. Biomedicines, 2024, 12(10). [CrossRef]

- TAIN Y L, HSU C N. The Renin-Angiotensin System and Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Syndrome: Focus on Early-Life Programming [J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2024, 25(6). [CrossRef]

- MORINELLI T A, LUTTRELL L M, STRUNGS E G, et al. Angiotensin II receptors and peritoneal dialysis-induced peritoneal fibrosis [J]. Int J Biochem Cell Biol, 2016, 77(Pt B): 240-50. [CrossRef]

| Variables | Total (n = 2460) | AIP | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < -0.05 | -0.05-0.2 | > 0.20 | |||

| (n = 815) | (n = 837) | (n = 808) | |||

| Age (yr) | 45.9±14.6 | 45.2±14.3 | 44.4±14.2 | 48.1±14.9 | < 0.001 |

| Male (n, %) | 1456(59.2) | 473 (58.0) | 486 (58.1) | 497 (61.5) | 0.261 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.79±3.92 | 20.98±4.90 | 21.58±3.17 | 22.81±3.29 | < 0.001 |

| Primary kidney disease (n, %) | < 0.001 | ||||

| Glomerulonephritis | 1496(60.8) | 531(65.2) | 528(63.1) | 437(54.1) | |

| Diabetic nephropathy | 479(19.5) | 139(17.1) | 146(17.4) | 194(24.0) | |

| Renal vascular diseases | 204(8.3) | 55(6.7) | 69(8.2) | 80(9.9) | |

| Other | 281(11.4) | 90(11.0) | 94(11.2) | 97(12.0) | |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Diabetes (n, %) | 498(20.2) | 142(17.4) | 150(17.9) | 206(25.5) | < 0.001 |

| CVD (n, %) | 290(11.8) | 80(9.8) | 87(10.4) | 123(15.2) | 0.001 |

| Medication use | |||||

| ACEI (n, %) | 277(11.3) | 95(11.7) | 81(9.7) | 101(12.5) | 0.176 |

| ARB (n, %) | 1047(42.6) | 376(46.1) | 340(40.6) | 331(41.0) | 0.041 |

| Lowing-lipid drugs | 315(12.8) | 79(9.7) | 104(12.4) | 132(16.3) | < 0.001 |

| AIP | 0.07(-0.11,0.28) | -0.20(-0.31,-0.11) | 0.07(0.01,0.14) | 0.37(0.28,0.52) | < 0.001 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.27±0.40 | 1.58±0.42 | 1.24±0.28 | 0.98±0.23 | < 0.001 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 3.00±0.94 | 2.94±0.89 | 3.10±0.95 | 2.96±0.97 | < 0.001 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 5.07±1.31 | 5.03±1.25 | 5.05±1.31 | 5.13±1.36 | 0.306 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.43(1.04, 2.02) | 0.92(0.74,1.11) | 1.43(1.25,1.69) | 2.36(1.92,3.18) | < 0.001 |

| Hemoglobin(g/L) | 107±19 | 106±19 | 108±19 | 107±19 | 0.041 |

| ALB(g/L) | 37.0±4.9 | 36.1±4.7 | 37.1±4.9 | 37.6±4.9 | < 0.001 |

| Calcium (mmol/L) | 2.25±0.20 | 2.21±0.20 | 2.25±0.19 | 2.28±0.21 | < 0.001 |

| Phosphorus (mmol/L) | 1.38±0.44 | 1.39±0.39 | 1.38±0.42 | 1.39±0.50 | 0.873 |

| 24-h urine volume (mL) | 1000(500,1500) | 950(500,1400) | 1000(500,1500) | 950(500,1500) | 0.208 |

| Scr (μmol/L) | 739±249 | 737±246 | 740±247 | 739±255 | 0.970 |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 16.2±5.6 | 17.0±5.9 | 16.2±5.3 | 15.5±5.5 | < 0.001 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 5.57±2.42 | 5.38±2.39 | 5.48±2.33 | 5.84±2.52 | < 0.001 |

| UA (μmol/L) | 408±93 | 393±88 | 411±91 | 419±99 | < 0.001 |

| iPTH | 243.6(121.7,400.1) | 271.1(133.7,432.1.6) | 246.8(130.4,398.0) | 215.8(108.2,379.4) | < 0.001 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) | 7.02±2.76 | 7.00±2.71 | 7.05±2.81 | 7.01±2.75 | 0.935 |

| Outcomes | Event | Model1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |||||

| All-cause mortality | ||||||||||

| Continuous AIP | 655/2460 | 1.814(1.402,2.349) | <0.001 | 1.419(1.072,1.878) | 0.014 | 1.421(1.075,1.879) | 0.014 | |||

| AIP categories | ||||||||||

| Tertile 1 | 206/815 | [Reference] | [Reference] | [Reference] | ||||||

| Tertile 2 | 196/837 | 0.964(0.792,1.173) | 0.715 | 0.953(0.773,1.176) | 0.656 | 0.969(0.785,1.196) | 0.768 | |||

| Tertile 3 | 253/808 | 1.505(1.251,1.810) | <0.001 | 1.271(1.039,1.555) | 0.020 | 1.280(1.046,1.567) | 0.017 | |||

| Cardiovascular mortality | ||||||||||

| Continuous AIP | 344/2460 | 1.892(1.326,2.699) | <0.001 | 1.385(0.944,2.033) | 0.096 | 1.385(0.943,2.033) | 0.096 | |||

| AIP categories | ||||||||||

| Tertile 1 | 96/815 | [Reference] | [Reference] | [Reference] | ||||||

| Tertile 2 | 110/837 | 1.165(0.885,1.533) | 0.275 | 1.153(0.862,1.543) | 0.338 | 1.149(0.858,1.539) | 0.352 | |||

| Tertile 3 | 138/808 | 1.754(1.350,2.278) | <0.001 | 1.433(1.080,1.902) | 0.013 | 1.430(1.078,1.899) | 0.013 | |||

| Peritonitis | ||||||||||

| Continuous AIP | 866/2460 | 1.266(1.007,1.593) | 0.044 | 1.275(0.992,1.637) | 0.057 | 1.272(0.990,1.634) | 0.060 | |||

| AIP categories | ||||||||||

| Tertile 1 | 288/815 | [Reference] | [Reference] | [Reference] | ||||||

| Tertile 2 | 310/837 | 1.130(0.962,1.327) | 0.138 | 1.191(1.007,1.409) | 0.042 | 1.182(0.999,1.399) | 0.052 | |||

| Tertile 3 | 268/808 | 1.199(1.014,1.417) | 0.034 | 1.209(1.010,1.449) | 0.039 | 1.204(1.005,1.442) | 0.044 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).