Submitted:

05 May 2025

Posted:

09 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

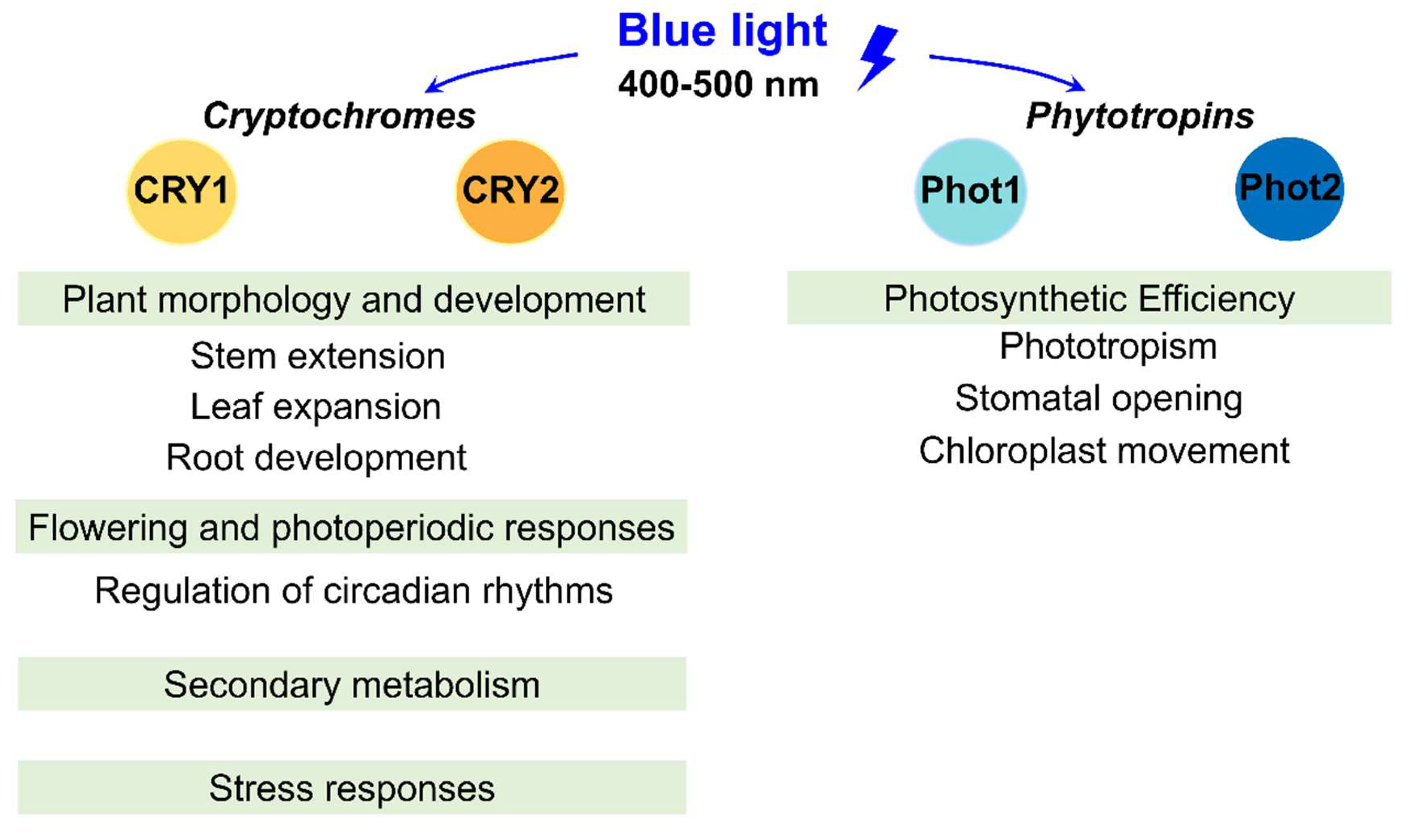

2. Blue Light

3. Effects of Blue Light on Plant Morphology and Development

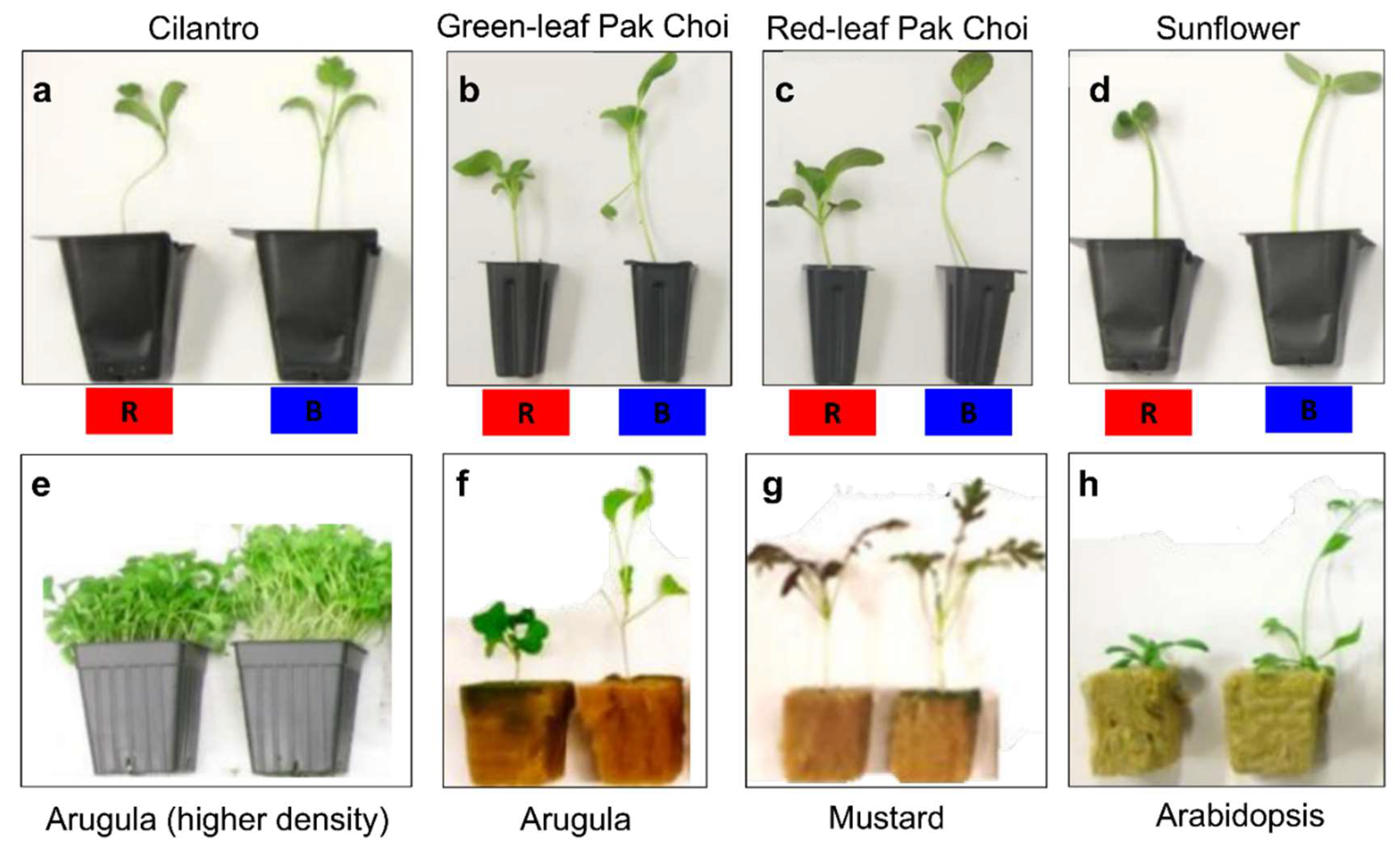

3.1. Growth and Development of Young Plants

3.2. Stem Elongation and Leaf Expansion of Mature Plants

3.3. Root Development and Architecture

3.4. Factors Influencing Blue Light Responses

3.4.1. Species- and Genotype-Specific Sensitivity

3.4.2. Spectral Interactions and Light Recipes

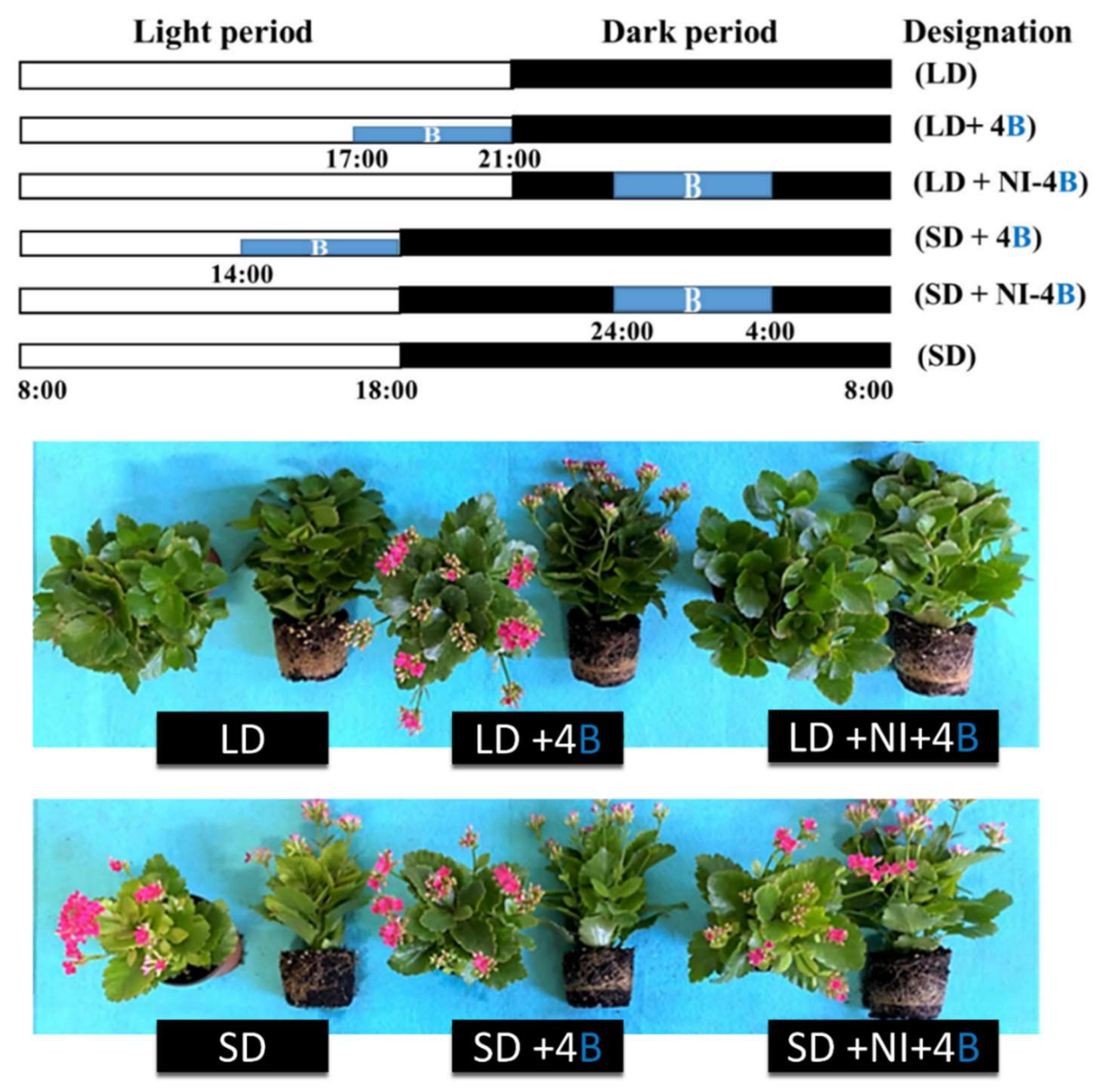

3.4.3. Night Interruption

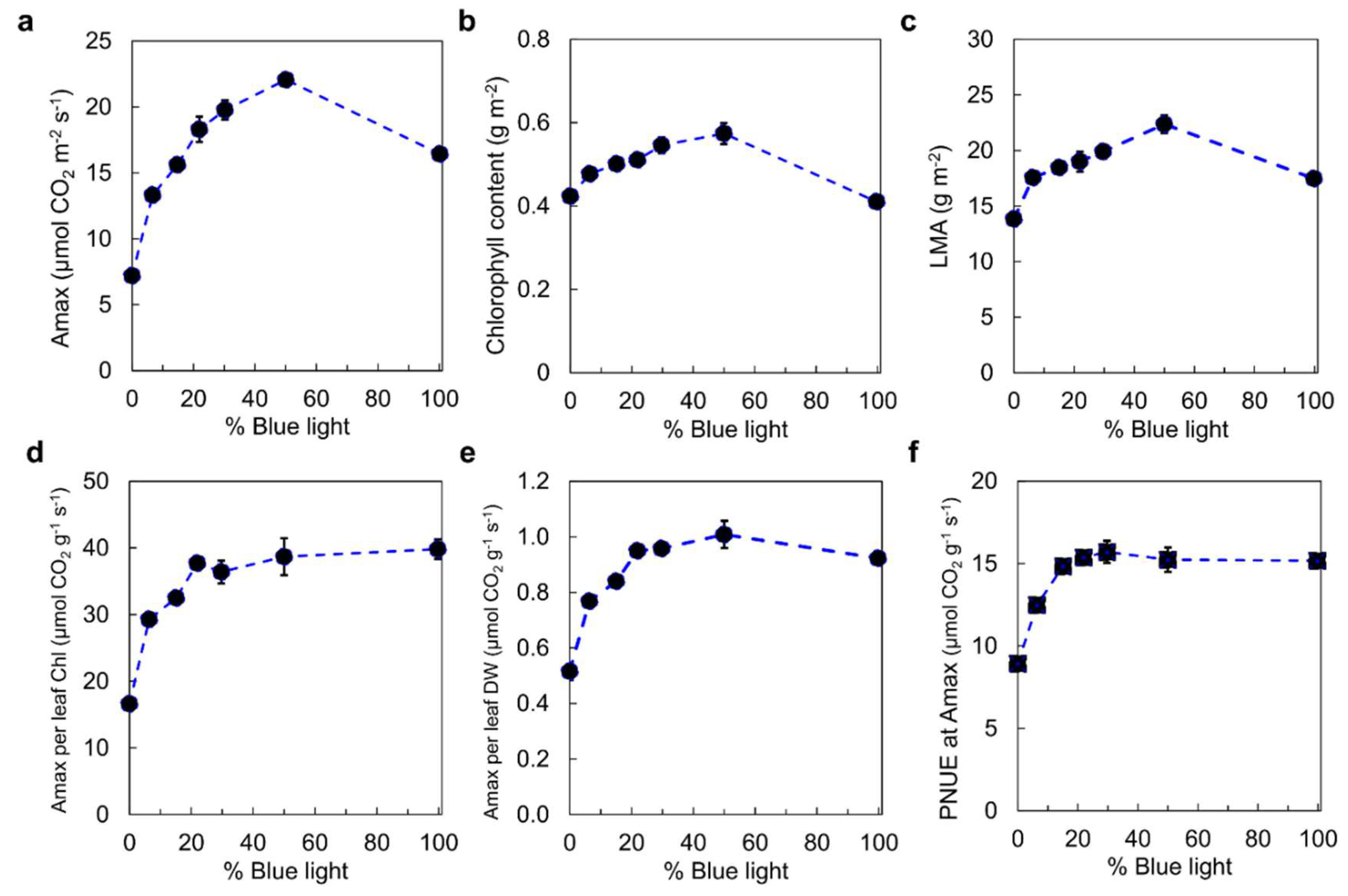

4. Photosynthetic Efficiency

5. Flowering and Photoperiodic Responses

6. Plant Secondary Metabolism

7. Blue Light-Mediated Stress Resilience

7.1. Drought Stress

7.2. Salt Stress

8. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Wilkinson, A.; Gerlach, C.; Karlsson, M.; Penn, H. Controlled environment agriculture and containerized food production in northern north america. J Agric Food Syst Co 2021, 10, 127-142. [CrossRef]

- Nelkin, J.; Caplow, T. Sustainable controlled environment agriculture for urban areas. Proceedings of the International Symposium on High Technology for Greenhouse System Management, Vols 1 and 2 2008, 449-455, . [CrossRef]

- Takakura, T. Controlled environment agriculture. Xi International Congress - the Use of Plastics in Agriculture, Vol 1 1990, F3-F10.

- Kotilainen, T.; Robson, T.M.; Hernández, R. Light quality characterization under climate screens and shade nets for controlled-environment agriculture. Plos One 2018, 13. [CrossRef]

- Pocock, T. Advanced lighting technology in controlled environment agriculture. Lighting Res Technol 2016, 48, 83-94. [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.G.; Moon, B.Y.; Kang, N.J. Effects of led light on the production of strawberry during cultivation in a plastic greenhouse and in a growth chamber. Sci Hortic-Amsterdam 2015, 189, 22-31. [CrossRef]

- Al Murad, M.; Razi, K.; Jeong, B.R.; Samy, P.M.A.; Muneer, S. Light emitting diodes (leds) as agricultural lighting: Impact and its potential on improving physiology, flowering, and secondary metabolites of crops. Sustainability-Basel 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Saebo, A.; Krekling, T.; Appelgren, M. Light quality affects photosynthesis and leaf anatomy of birch plantlets in-vitro. Plant Cell Tiss Org 1995, 41, 177-185. [CrossRef]

- Sumida, S.; Ehara, T.; Osafune, T.; Ohkuro, I.; Hase, E. Effects of blue-light on chloroplast development in dark-grown euglena-gracilis z. J. Electron Microsc. 1984, 33, 304-305.

- Zeiger, E. Light perception in guard-cells. Plant Cell Environ 1990, 13, 739-744. [CrossRef]

- Senger, H. The effect of blue-light on plants and microorganisms. Photochemistry and Photobiology 1982, 35, 911-920. [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, D.J. Rapid suppression of growth by blue-light - occurrence, time course, and general-characteristics. Plant Physiol. 1981, 67, 584-590. [CrossRef]

- Talbott, L.D.; Hammad, J.W.; Harn, L.C.; Nguyen, V.H.; Patel, J.; Zeiger, E. Reversal by green light of blue light-stimulated stomatal opening in intact, attached leaves of arabidopsis operates only in the potassium-dependent, morning phase of movement. PCPhy 2006, 47, 332-339. [CrossRef]

- Frechilla, S.; Talbott, L.D.; Bogomolni, R.A.; Zeiger, E. Reversal of blue light-stimulated stomatal opening by green light. PCPhy 2000, 41, 171-176.

- Yang, J.; Song, J.N.; Jeong, B.R. Blue light supplemented at intervals in long-day conditions intervenes in photoperiodic flowering, photosynthesis, and antioxidant properties in chrysanthemums. Antioxidants-Basel 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Song, J.; Jeong, B.R. Low-intensity blue light supplemented during photoperiod in controlled environment induces flowering and antioxidant production in kalanchoe. Antioxidants-Basel 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Song, J.; Jeong, B.R. Lighting from top and side enhances photosynthesis and plant performance by improving light usage efficiency. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Jeong, B.R. Side lighting enhances morphophysiology by inducing more branching and flowering in chrysanthemum grown in controlled environment. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.L.; Song, J.N.; Jeong, B.R. Flowering and runnering of seasonal strawberry under different photoperiods are affected by intensity of supplemental or night-interrupting blue light. Plants-Basel 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.A. Using light to improve commercial value. Hortic Res-England 2018, 5. [CrossRef]

- Mccree, K.J. Action spectrum, absorptance and quantum yield of photosynthesis in crop plants. Agr. Meteorol. 1972, 9, 191-&. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.G.; Terzaghi, W.; Deng, X.W. Genomic basis for light control of plant development. Protein Cell 2012, 3, 106-116. [CrossRef]

- Cashmore, A.R.; Jarillo, J.A.; Wu, Y.J.; Liu, D.M. Cryptochromes: Blue light receptors for plants and animals. Science 1999, 284, 760-765. [CrossRef]

- Huché-Thélier, L.; Crespel, L.; Le Gourrierec, J.; Morel, P.; Sakr, S.; Leduc, N. Light signaling and plant responses to blue and uv radiations-perspectives for applications in horticulture. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2016, 121, 22-38. [CrossRef]

- Hogewoning, S.W.; Trouwborst, G.; Maljaars, H.; Poorter, H.; van Ieperen, W.; Harbinson, J. Blue light dose-responses of leaf photosynthesis, morphology, and chemical composition of grown under different combinations of red and blue light. Journal of Experimental Botany 2010, 61, 3107-3117. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.J.; Zhang, Y.T.; Liu, H.C.; Li, Y.M.; Liu, Y.L.; Hao, Y.W.; Lei, B.F. Supplemental blue light increases growth and quality of greenhouse pak choi depending on cultivar and supplemental light intensity. J Integr Agr 2018, 17, 2245-2256. [CrossRef]

- Yanagi, T.; Okamoto, K.; Takita, S. Effects of blue, red, and blue/red lights of two different ppf levels on growth and morphogenesis of lettuce plants. International Symposium on Plant Production in Closed Ecosystems - Automation, Culture, and Environment 1997, 117-122.

- Naznin, M.T.; Lefsrud, M.; Gravel, V.; Azad, M.O.K. Blue light added with red leds enhance growth characteristics, pigments content, and antioxidant capacity in lettuce, spinach, kale, basil, and sweet pepper in a controlled environment. Plants-Basel 2019, 8. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.T.P.; Kitayama, M.; Lu, N.; Takagaki, M. Improving secondary metabolite accumulation, mineral content, and growth of coriander (coriandrum sativum l.) by regulating light quality in a plant factory. J. Horticult. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 95, 356-363. [CrossRef]

- Appelgren, M. Effects of light quality on stem elongation of pelargonium invitro. Sci Hortic-Amsterdam 1991, 45, 345-351. [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, R.M.; Mackowiak, C.L.; Sager, J.C. Soybean stem growth under high-pressure sodium with supplemental blue lighting. Agron. J. 1991, 83, 903-906. [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.S.; Schuerger, A.C.; Sager, J.C. Growth and photomorphogenesis of pepper plants under red light-emitting-diodes with supplemental blue or far-red lighting. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 1995, 120, 808-813. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Seo, J.M.; Lee, M.K.; Chun, J.H.; Antonisamy, P.; Arasu, M.V.; Suzuki, T.; Al-Dhabi, N.A.; Kim, S.J. Influence of different led lamps on the production of phenolic compounds in common and tartary buckwheat sprouts. Ind Crop Prod 2014, 54, 320-326. [CrossRef]

- Hernández, R.; Kubota, C. Physiological responses of cucumber seedlings under different blue and red photon flux ratios using leds. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2016, 121, 66-74. [CrossRef]

- Tymoszuk, A.; Kulus, D.; Błażejewska, A.; Nadolna, K.; Kulpińska, A.; Pietrzykowski, K. Application of wide-spectrum light-emitting diodes in the indoor production of cucumber and tomato seedlings. Acta Agro 2023, 76. [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Zheng, Y.B. Magic blue light: A versatile mediator of plant elongation. Plants-Basel 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.X.; Xu, Z.G.; Dong, R.Q.; Chang, S.X.; Wang, L.Z.; Khalil-Ur-Rehman, M.; Tao, J.M. An rna-seq analysis of grape plantlets grown in vitro reveals different responses to blue, green, red led light, and white fluorescent light. Front Plant Sci 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.J.; Kwon, S.J.; Eom, S.H. Red and blue light-specific metabolic changes in soybean seedlings. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Hahn, E.J.; Kozai, T.; Paek, K.Y. Combinations of blue and red leds increase the morphophysiological performance and furanocoumarin production of brosimum gaudichaudii trécul in vitro. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 680545.

- Rabara, R.C.; Behrman, G.; Timbol, T.; Rushton, P.J. Effect of spectral quality of monochromatic led lights on the growth of artichoke seedlings. Front Plant Sci 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Ji, L.Y.; Xing, Y.Y.; Zuo, Z.C.; Zhang, L. Data-independent acquisition proteomics reveals the effects of red and blue light on the growth and development of moso bamboo (phyllostachys edulis) seedlings. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Kochetova, G.V.; Avercheva, O.V.; Bassarskaya, E.M.; Kushunina, M.A.; Zhigalova, T.V. Effects of red and blue led light on the growth and photosynthesis of barley (hordeum vulgare l.) seedlings. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 1804-1820. [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.L.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Hong, A.Y.; Liu, Y. Effects of photoperiod extension via red-blue light-emitting diodes and high-pressure sodium lamps on the growth and photosynthetic characteristics in. Acta Physiol Plant 2020, 42. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Liao, Q.H.; Li, Q.M.; Yang, Q.C.; Wang, F.; Li, J.M. Effects of led red and blue light component on growth and photosynthetic characteristics of coriander in plant factory. Horticulturae 2022, 8. [CrossRef]

- Wollaeger, H.M.; Runkle, E.S. Growth of impatiens, petunia, salvia, and tomato seedlings under blue, green, and red light-emitting diodes. HortScience 2014, 49, 734-740. [CrossRef]

- Wollaeger, H.M.; Runkle, E.S. Growth and acclimation of impatiens, salvia, petunia, and tomato seedlings to blue and red light. HortScience 2015, 50, 522-529. [CrossRef]

- Correia, C.; Magnani, F.; Pastore, C.; Cellini, A.; Donati, I.; Pennisi, G.; Paucek, I.; Orsini, F.; Vandelle, E.; Santos, C.; et al. Red and blue light differently influence actinidia chinensis performance and its interaction with pseudomonas syringae pv. Actinidiae. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.Q.; Niu, Y.N.; Hossain, Z.; Zhao, B.Y.; Bai, X.D.; Mao, T.T. New insights into light spectral quality inhibits the plasticity elongation of maize mesocotyl and coleoptile during seed germination. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.W.; Dai, X.; Sun, G.Y. Morphological and physiological responses of morus alba seedlings under different light qualities. Not Bot Horti Agrobo 2016, 44, 382-392. [CrossRef]

- Snowden, M.C.; Cope, K.R.; Bugbee, B. Sensitivity of seven diverse species to blue and green light: Interactions with photon flux. Plos One 2016, 11. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Huang, M.Y.; Lin, K.H.; Wong, S.L.; Huang, W.D.; Yang, C.M. Effects of light quality on the growth, development and metabolism of rice seedlings (oryza sativa l.). Res J Biotechnol 2014, 9, 15-24.

- Ren, M.F.; Liu, S.Z.; Tang, C.Z.; Mao, G.L.; Gai, P.P.; Guo, X.L.; Zheng, H.B.; Tang, Q.Y. Photomorphogenesis and photosynthetic traits changes in rice seedlings responding to red and blue light. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Akbarian, B.; Matloobi, M.; Mahna, N. Effects of led light on seed emergence and seedling quality of four bedding flowers. J. Ornam. Hortic. Plants 2016, 6, 115-123.

- Kong, Y.; Schiestel, K.; Zheng, Y.B. Pure blue light effects on growth and morphology are slightly changed by adding low-level uva or far-red light: A comparison with red light in four microgreen species. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2019, 157, 58-68. [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Schiestel, K.; Zheng, Y.B. Maximum elongation growth promoted as a shade-avoidance response by blue light is related to deactivated phytochrome: A comparison with red light in four microgreen species. Can J Plant Sci 2020, 100, 314-326. [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Kamath, D.; Zheng, Y.B. Blue versus red light can promote elongation growth independent of photoperiod: A study in four brassica microgreens species. HortScience 2019, 54, 1955-1961. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.E.; Kong, Y.; Zheng, Y.B. Elongation growth mediated by blue light varies with light intensities and plant species: A comparison with red light in arugula and mustard seedlings. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020, 169. [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Schiestel, K.; Zheng, Y. Blue light associated with low phytochrome activity can promote flowering: A comparison with red light in four bedding plant specie. Acta Hortic. 2020, 1296, 621-628.

- Kong, Y.; Kamath, D.; Zheng, Y. Blue-light-promoted elongation and flowering are not artifacts from 24-h lighting: A comparison with red light in four bedding plant specie. Acta Hortic. 2020, 1295, 659-666.

- Kong, Y.; Masabni, J.; Niu, G. Effect of temperature variation and blue and red leds on the elongation of arugula and mustard microgreens. Horticulturae 2023. [CrossRef]

- Hirai, T.; Amaki, W.; Watanabe, H. Action of blue or red monochromatic light on stem internodal growth depends on plant species. Sci. Hortic. 2006, 109995.

- Di, Q.H.; Li, J.; Du, Y.F.; Wei, M.; Shi, Q.H.; Li, Y.; Yang, F.J. Combination of red and blue lights improved the growth and development of eggplant (solanum melongena l.) seedlings by regulating photosynthesis. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2021, 40, 1477-1492. [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, K. Effect of different light on the growth and development of pea plant. Int. J. Res. Eng. Sci. 2023, 94-98.

- Hata, N.; Hayashi, Y.; Ono, E.; Satake, H.; Kobayashi, A.; Muranaka, T.; Okazawa, A. Differences in plant growth and leaf sesamin content of the lignan-rich sesame variety 'gomazou' under continuous light of different wavelengths. Plant Biotechnol. 2013, 30, 1-U104. [CrossRef]

- Spaninks, K.; Lamers, G.; van Lieshout, J.; Offringa, R. Light quality regulates apical and primary radial growth of arabidopsis thaliana and solanum lycopersicum. Sci Hortic-Amsterdam 2023, 317. [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Zheng, Y.B. Growth and morphology responses to narrow-band blue light and its co-action with low-level uvb or green light: A comparison with red light in four microgreen species. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020, 178. [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, T.; Amaki, W.; Watanabe, H. Effects of monochromatic light irradiation by led on the growth and anthocyanin contents in leaves of cabbage seedlings. Vi International Symposium on Light in Horticulture 2011, 907, 179-184. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y.; Chang, T.T.; Guo, S.R.; Xu, Z.G.; Li, J. Effect of different light quality of led on growth and photosynthetic character in cherry tomato seedling. Vi International Symposium on Light in Horticulture 2011, 907, 325-330.

- Liu, X.; Guo, S.; Chang, T.; Xu, Z.; Tezuka, T. Regulation of the growth and photosynthesis of cherry tomato seedlings by different light irradiations of light emitting diodes (led). Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2012, 11, 6169–6177.

- Kim, E.Y.; Park, S.A.; Park, B.J.; Lee, Y.; Oh, M.M. Growth and antioxidant phenolic compounds in cherry tomato seedlings grown under monochromatic light-emitting diodes. Hortic Environ Biote 2014, 55, 506-513. [CrossRef]

- Hernández, R.; Eguchi, T.; Kubota, C. Growth and morphology of vegetable seedlings under different blue and red photon flux ratios using light-emitting diodes as sole-source lighting. Viii International Symposium on Light in Horticulture 2016, 1134, 195-200. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Kang, C.Q.; Kaiser, E.; Kuang, Y.; Yang, Q.C.; Li, T. Red/blue light ratios induce morphology and physiology alterations differently in cucumber and tomato. Sci Hortic-Amsterdam 2021, 281. [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowska, R.; Dabrowa, A.; Kolton, A. How monochromatic and composed light affect the kale 'scarlet' in its initial growth stage. Acta Sci Pol-Hortoru 2023, 22, 93-100. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.W.; Runkle, E.S. Growth responses of red-leaf lettuce to temporal spectral changes. Front Plant Sci 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Schiestel, K.; Zheng, Y. Does “blue” light invariably cause plant compactness? Not really: A comparison with red light in four bedding plant species during the transplant stage. Acta Hortic. 2020, 621-628.

- Brazaityte, A.; Miliauskiene, J.; Vastakaite-Kairiene, V.; Sutuliene, R.; Lauzike, K.; Duchovskis, P.; Malek, S. Effect of different ratios of blue and red led light on brassicaceae microgreens under a controlled environment. Plants-Basel 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Nie, W.F.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, T.; Zhou, Y.H.; Yang, Y.X. Spectral light quality regulates the morphogenesis, architecture, and flowering in pepper (capsicum annuum l.). J Photoch Photobio B 2023, 241. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xin, G.F.; Shi, Q.H.; Yang, F.J.; Wei, M. Response of photomorphogenesis and photosynthetic properties of sweet pepper seedlings exposed to mixed red and blue light. Front Plant Sci 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.J.; Murthy, H.N.; Song, H.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Park, S.Y. Influence of white, red, blue, and combination of led lights on in vitro multiplication of shoots, rooting, and acclimatization of gerbera jamesonii cv. ‘Shy pink’ plants. Agronomy-Basel 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.H.; Chen, Y.C.; Wu, Q.E.; Lin, H.H. Effects of red and blue light ratio on the morphological traits and flower sex expression in cucurbita moschata duch. Not Bot Horti Agrobo 2023, 51. [CrossRef]

- Izzo, L.G.; Mele, B.H.; Vitale, L.; Vitale, E.; Arena, C. The role of monochromatic red and blue light in tomato early photomorphogenesis and photosynthetic traits. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020, 179. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Bisbis, M.; Heuvelink, E.; Jiang, W.J.; Marcelis, L.F.M. Green light reduces elongation when partially replacing sole blue light independently from cryptochrome 1a. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 173, 1946-1955. [CrossRef]

- Bian, Z.H.; Cheng, R.F.; Yang, Q.C.; Wang, J.; Lu, C.G. Continuous light from red, blue, and green light-emitting diodes reduces nitrate content and enhances phytochemical concentrations and antioxidant capacity in lettuce. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 2016, 141, 186-U216. [CrossRef]

- Taulavuori, K.; Hyöky, V.; Oksanen, J.; Taulavuori, E.; Julkunen-Tiitto, R. Species-specific differences in synthesis of flavonoids and phenolic acids under increasing periods of enhanced blue light. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2016, 121, 145-150. [CrossRef]

- Son, K.H.; Oh, M.M. Growth, photosynthetic and antioxidant parameters of two lettuce cultivars as affected by red, green, and blue light-emitting diodes. Hortic Environ Biote 2015, 56, 639-653. [CrossRef]

- Johkan, M.; Shoji, K.; Goto, F.; Hashida, S.; Yoshihara, T. Blue light-emitting diode light irradiation of seedlings improves seedling quality and growth after transplanting in red leaf lettuce. HortScience 2010, 45, 1809-1814. [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.; Lee, C.; Chakrabarty, D.; Paek, K. Growth responses of marigold and salvia bedding plants as affected by monochromic or mixture radiation provided by a light-emitting diode (led). Plant Growth Regul 2002, 38, 225-230. [CrossRef]

- Samuoliene, G.; Brazaityte, A.; Urbonaviciute, A.; Sabajeviene, G.; Duchovskis, P. The effect of red and blue light component on the growth and development of frigo strawberries. Zemdirbyste 2010, 97, 99-104.

- Gangadhar, B.H.; Mishra, R.K.; Pandian, G.; Park, S.W. Comparative study of color, pungency, and biochemical composition in chili pepper (capsicum annuum) under different light-emitting diode treatments. HortScience 2012, 47, 1729-1735. [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, R.; Ohashi-Kaneko, K.; Fujiwara, K.; Kurata, K. Analysis of the relationship between blue-light photon flux density and the photosynthetic properties of spinach (l.) leaves with regard to the acclimation of photosynthesis to growth irradiance. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2007, 53, 459-465. [CrossRef]

- Yorio, N.C.; Goins, G.D.; Kagie, H.R.; Wheeler, R.M.; Sager, J.C. Improving spinach, radish, and lettuce growth under red light-emitting diodes (leds) with blue light supplementation. HortScience 2001, 36, 380-383. [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.W.; Kang, D.H.; Bang, H.S.; Hong, S.G.; Chun, C.; Kang, K.K. Early growth, pigmentation, protein content, and phenylalanine ammonia-lyase activity of red curled lettuces grown under different lighting conditions. Korean J Hortic Sci 2012, 30, 6-12. [CrossRef]

- Kalaitzoglou, P.; Taylor, C.; Calders, K.; Hogervorst, M.; van Ieperen, W.; Harbinson, J.; de Visser, P.; Nicole, C.C.S.; Marcelis, L.F.M. Unraveling the effects of blue light in an artificial solar background light on growth of tomato plants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2021, 184. [CrossRef]

- Terashima, I.; Fujita, T.; Inoue, T.; Chow, W.S.; Oguchi, R. Green light drives leaf photosynthesis more efficiently than red light in strong white light: Revisiting the enigmatic question of why leaves are green. PCPhy 2009, 50, 684-697. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.H.; Wheeler, R.M.; Sager, J.C.; Goins, G.D. A comparison of growth and photosynthetic characteristics of lettuce grown under red and blue light-emitting diodes (leds) with and without supplemental green leds. Proceedings of the Viith International Symposium on Protected Cultivation in Mild Winter Climates: Production, Pest Management and Global Competition, Vols 1 and 2 2004, 467-475. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.H.; Goins, G.D.; Wheeler, R.M.; Sager, J.C. Green-light supplementation for enhanced lettuce growth under red- and blue-light-emitting diodes. HortScience 2004, 39, 1617-1622. [CrossRef]

- Ouzounis, T.; Heuvelink, E.; Ji, Y.; Schouten, H.J.; Visser, R.G.F.; Marcelis, L.F.M. Blue and red led lighting effects on plant biomass, stomata! Conductance, and metabolite content in nine tomato genotypes. Viii International Symposium on Light in Horticulture 2016, 1134, 251-258. [CrossRef]

- Pashkovskiy, P.P.; Kartashov, A.V.; Zlobin, I.E.; Pogosyan, S.I.; Kuznetsov, V.V. Blue light alters mir167 expression and microrna-targeted auxin response factor genes in arabidopsis thaliana plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 104, 146-154. [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.X.; Chen, Q.Y.; Qu, M.; Gao, L.H.; Hou, L.P. Blue light alleviates 'red light syndrome' by regulating chloroplast ultrastructure, photosynthetic traits and nutrient accumulation in cucumber plants. Sci Hortic-Amsterdam 2019, 257. [CrossRef]

- Canamero, R.C.; Bakrim, N.; Bouly, J.P.; Garay, A.; Dudkin, E.E.; Habricot, Y.; Ahmad, M. Cryptochrome photoreceptors cry1 and cry2 antagonistically regulate primary root elongation in. Planta 2006, 224, 995-1003. [CrossRef]

- Vandenbrink, J.P.; Herranz, R.; Medina, F.J.; Edelmann, R.E.; Kiss, J.Z. A novel blue-light phototropic response is revealed in roots of arabidopsis thalianain microgravity. Planta 2016, 244, 1201-1215. [CrossRef]

- Iacona, C.; Muleo, R. Light quality affects adventitious rooting and performance of cherry rootstock colt. Sci Hortic-Amsterdam 2010, 125, 630-636. [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.Z.; Su, X.F.; Li, Y.F.; Shi, M.M.; Yang, B.B.; Wan, W.C.; Wen, X.; Yang, S.J.; Ding, X.T.; Zou, J. Effect of red and blue light on cucumber seedlings grown in a plant factory. Horticulturae 2023, 9. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, S.; Cai, W.; Xiang, Z.X.; Chen, C.Y.; Lu, Y.T.; Yuan, T.T. Pin3-mediated auxin transport contributes to blue light-induced adventitious root formation in arabidopsis. Plant Sci. 2021, 312. [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.W.; Lee, C.W.; Paek, K.Y. Influence of mixed led radiation on the growth of annual plants. J Plant Biol 2006, 49, 286-290. [CrossRef]

- Mckay, M.; Faust, J.E.; Taylor, M.; Adelberg, J. The effects of blue light and supplemental far-red on an in vitro multiple harvest system for the production of cannabis sativa. Plants-Basel 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Vince-Prue, D.; Canham, A.E. Horticultural significance of photomorphogenesis. Encyclopedia of Plant Physiol 1983, NS 16B, 518-544.

- Park, Y.G.; Jeong, B.R. Night interruption light quality changes morphogenesis, flowering, and gene expression in dendranthema grandiflorum. Hortic Environ Biote 2019, 60, 167-173. [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.G.; Jeong, B.R. How supplementary or night-interrupting low-intensity blue light affects the flower induction in chrysanthemum, a qualitative short-day plant. Plants-Basel 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.G.; Jeong, B.R. Both the quality and positioning of the night interruption light are important for flowering and plant extension growth. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2020, 39, 583-593. [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.G.; Jeong, B.R. The quality and quality shifting of the night interruption light 2022.

- Park, Y.G.; Jeong, B.R. Shift in the light quality of night interruption affects flowering and morphogenesis of petunia hybrida. Plants-Basel 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.G.; Jeong, B.R. Photoreceptors modulate the flowering and morphogenesis responses of pelargonium × hortorum to night-interruption light quality shifting. Agronomy-Basel 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.G.; Muneer, S.; Jeong, B.R. Morphogenesis, flowering, and gene expression of dendranthema grandiflorum in response to shift in light quality of night interruption. Int J Mol Sci 2015, 16, 16497-16513. [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.G.; Muneer, S.; Soundararajan, P.; Manivnnan, A.; Jeong, B.R. Light quality during night interruption affects morphogenesis and flowering in petunia hybrida , a qualitative long-day plant. Hortic Environ Biote 2016, 57, 371-377. [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.G.; Muneer, S.; Soundararajan, P.; Manivnnan, A.; Jeong, B.R. Light quality during night interruption affects morphogenesis and flowering in geranium. Hortic Environ Biote 2017, 58, 212-217. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, A.; Tanigawa, T.; Suyama, T.; Matsuno, T.; Kunitake, T. Night break treatment using different light sources promotes or delays growth and flowering of (raf.) shinn. J Jpn Soc Hortic Sci 2008, 77, 69-74. [CrossRef]

- Pérez, C.P.; Ulrichs, C.; Huyskens-Keil, S.; Schreiner, M.; Krumbein, A.; Schwarz, D.; Kläring, H.P. Composition of carotenoids in tomato fruits as affected by moderate uv-b radiation before harvest. International Symposium on Tomato in the Tropics 2009, 821, 217-221. [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Zheng, Y.B. Diverse flowering response to blue light manipulation: Application of electric lighting in controlled-environment plant production. Horticulturae 2024, 10. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.D. Plant responses to photoperiod. New Phytol. 2009, 181, 517-531. [CrossRef]

- Walters, K.J.; Hurt, A.A.; Lopez, R.G. Flowering, stem extension growth, and cutting yield of foliage annuals in response to photoperiod. HortScience 2019, 54, 661-666. [CrossRef]

- Chandel, A.; Thakur, M.; Singh, G.; Dogra, R.; Bajad, A.; Soni, V.; Bhargava, B. Flower regulation in floriculture: An agronomic concept and commercial use. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 2136-2161. [CrossRef]

- Izawa, T. Daylength measurements by rice plants in photoperiodic short-day flowering. International Review of Cytology - a Survey of Cell Biology, Vol 256 2007, 256, 191-+. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Kaya, H.; Goto, K.; Iwabuchi, M.; Araki, T. A pair of related genes with antagonistic roles in mediating flowering signals. Science 1999, 286, 1960-1962. [CrossRef]

- Whitman, C.M.; Heins, R.D.; Cameron, A.C.; Carlson, W.H. Lamp type and irradiance level for daylength extensions influence flowering of 'blue clips', 'early sunrise', and 'moonbeam'. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 1998, 123, 802-807. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Runkle, E.S. Low-intensity blue light in night-interruption lighting does not influence flowering of herbaceous ornamentals. Sci Hortic-Amsterdam 2015, 186, 230-238.

- Lopez, R.G.; Meng, Q.W.; Runkle, E.S. Blue radiation signals and saturates photoperiodic flowering of several long-day plants at crop-specific photon flux densities. Sci Hortic-Amsterdam 2020, 271. [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.I.; Jeong, H.K.; Park, Y.G.; Jeong, B.R. Flowering and morphogenesis of kalanchoe in response to quality and intensity of night interruption light. Plants-Basel 2019, 8. [CrossRef]

- Nissim-Levi, A.; Kitron, M.; Nishri, Y.; Ovadia, R.; Forer, I.; Oren-Shamir, M. Effects of blue and red led lights on growth and flowering of. Sci Hortic-Amsterdam 2019, 254, 77-83. [CrossRef]

- Magar, Y.G.; Ohyama, K.; Noguchi, A.; Amaki, W.; Furufuji, S. Effects of light quality during supplemental lighting on the flowering in an everbearing strawberry. Xiii International Symposium on Plant Bioregulators in Fruit Production 2018, 1206, 279-284. [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.Y.; Kadowaki, M.; Che, J.; Takahashi, S.; Horiuchi, N.; Ogiwara, I. Influence of light quality on flowering characteristics, potential for year-round fruit production and fruit quality of blueberry in a plant factory. Fruits 2019, 74, 3-10. [CrossRef]

- Javanmardi, J.; and Emami, S. Response of tomato and pepper transplants to light spectra provided by light emitting diodes. International Journal of Vegetable Science 2013, 19, 138-149. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhang, Y.C.; Zhou, L.; Yang, L.Y. Growth and flowering of saffron (crocus sativus l.) with three corm weights under different led light qualities. Sci Hortic-Amsterdam 2022, 303. [CrossRef]

- Ouzounis, T.; Rosenqvist, E.; Ottosen, C.O. Spectral effects of artificial light on plant physiology and secondary metabolism: A review. HortScience 2015, 50, 1128-1135. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.S.; Lyu, Y.M.; Chen, X.H.; Wang, C.Q.; Yao, D.H.; Ni, S.S.; Lin, Y.L.; Chen, Y.K.; Zhang, Z.H.; Lai, Z.X. Exploration of the effect of blue light on functional metabolite accumulation in longan embryonic calli via rna sequencing. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.S.; Lin, Y.L.; Chen, X.H.; Bai, Y.; Wang, C.Q.; Xu, X.P.; Wang, Y.; Lai, Z.X. Effects of blue light on flavonoid accumulation linked to the expression of mir393, mir394 and mir395 in longan embryogenic calli. Plos One 2018, 13. [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.L.; Yuan, Z.Y.; Xie, J.; Yao, S.X.; Zeng, K.F. Sensitivity to ethephon degreening treatment is altered by blue led light irradiation in mandarin fruit. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2017, 65, 6158-6168. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.Y.; Deng, L.L.; Yin, B.F.; Yao, S.X.; Zeng, K.F. Effects of blue led light irradiation on pigment metabolism of ethephon-degreened mandarin fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2017, 134, 45-54. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.C.; Ma, G.; Yamawaki, K.; Ikoma, Y.; Matsumoto, H.; Yoshioka, T.; Ohta, S.; Kato, M. Effect of blue led light intensity on carotenoid accumulation in citrus juice sacs. J. Plant Physiol. 2015, 188, 58-63. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Kubota, C. Effects of supplemental light quality on growth and phytochemicals of baby leaf lettuce. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2009, 67, 59-64. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Cashmore, A.R. The blue-light receptor cryptochrome 1 shows functional dependence on phytochrome a or phytochrome b in arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1997, 11, 421-427. [CrossRef]

- Folta, K.M.; Maruhnich, S.A. Green light: A signal to slow down or stop. Journal of Experimental Botany 2007, 58, 3099-3111. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.T.; Folta, K.M. Green light signaling and adaptive response. Plant Signal Behav 2012, 7, 75-78. [CrossRef]

- Kopsell, D.A.; Sams, C.E.; Barickman, T.C.; Morrow, R.C. Sprouting broccoli accumulate higher concentrations of nutritionally important metabolites under narrow-band light-emitting diode lighting. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 2014, 139, 469-477. [CrossRef]

- Samuoliene, G.; Sirtautas, R.; Brazaityte, A.; Duchovskis, P. Led lighting and seasonality effects antioxidant properties of baby leaf lettuce. Food Chem. 2012, 134, 1494-1499. [CrossRef]

- Atta, M.; Idris, A.; Bukhari, A.; Wahidin, S. Intensity of blue led light: A potential stimulus for biomass and lipid content in fresh water microalgae. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 148, 373-378. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.Y.; Nie, J.W.; Yan, X.Y.; Xue, W.T. Identifying the critical led light condition for optimum yield and flavonoid of pea sprouts. Sci Hortic-Amsterdam 2024, 327. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Ma, J.Q.; Ma, C.L.; Shen, S.Y.; Liu, Y.F.; Chen, L. Regulation of growth and flavonoid formation of tea plants () by blue and green light. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2019, 67, 2408-2419. [CrossRef]

- Inoue, S.; Kinoshita, T. Blue light regulation of stomatal opening and the plasma membrane h(+)-atpase. Plant Physiol. 2017, 174, 531-538. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.F.; Jin, Y.H.; Yoo, C.Y.; Lin, X.L.; Kim, W.Y.; Yun, D.J.; Bressan, R.A.; Hasegawa, P.M.; Jin, J.B. Cyclin h;1 regulates drought stress responses and blue light-induced stomatal opening by inhibiting reactive oxygen species accumulation in arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 1030-1041. [CrossRef]

- D'Amico-Damiao, V.; Lúcio, J.C.B.; Oliveira, R.; Gaion, L.A.; Barreto, R.F.; Carvalho, R.F. Cryptochrome 1a depends on blue light fluence rate to mediate osmotic stress responses in tomato. J. Plant Physiol. 2021, 258. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, T.; Shabani, L.; Sabzalian, M.R. Improvement in drought tolerance of lemon balm, melissa officinalis l. Under the pre-treatment of led lighting. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 139, 548-557. [CrossRef]

- Ginzburg, D.N.; Klein, J.D. Led pre-exposure shines a new light on drought tolerance complexity in lettuce (lactuca sativa) and rocket (eruca sativa). Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020, 180. [CrossRef]

- Tattini, M.; Galardi, C.; Pinelli, P.; Massai, R.; Remorini, D.; Agati, G. Differential accumulation of flavonoids and hydroxycinnamates in leaves of ligustrum vulgare under excess light and drought stress. New Phytol. 2004, 163, 547-561. [CrossRef]

- He, C.X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cai, J.F.; Gao, J.; Zhang, J.S. Forage quality and physiological performance of mowed alfalfa (medicago sativa l.) subjected to combined light quality and drought. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.X.; Yang, W.J.; Pan, Q.M.; Zeng, Q.; Yan, C.T.; Bai, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.G.; Li, B.H. Effects of long-term blue light irradiation on carotenoid biosynthesis and antioxidant activities in chinese cabbage (brassica rapa l. Ssp. Pekinensis). Food Res. Int. 2023, 174. [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.; Fiebig, A.; Noga, G.; Hunsche, M. Influence of light quality on leaf physiology of sweet pepper plants grown underdrought. Theor Exp Plant Phys 2018, 30, 287-296. [CrossRef]

- Terfa, M.T.; Olsen, J.E.; Torre, S. Blue light improves stomatal function and dark-induced closure of rose leaves (rosa x hybrida) developed at high air humidity. Front Plant Sci 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Barillot, R.; De Swaef, T.; Combes, D.; Durand, J.L.; Escobar-Gutiérrez, A.J.; Martre, P.; Perrot, C.; Roy, E.; Frak, E. Leaf elongation response to blue light is mediated by stomatal-induced variations in transpiration in. Journal of Experimental Botany 2021, 72, 2642-2656. [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Kambale, R.D.; Tzeng, J.-H.; Amy, G.L.; Ladner, D.A.; Karthikeyan, R. The growing trend of saltwater intrusion and its impact on coastal agriculture: Challenges and opportunities. Sci. Tot. Environ. 2025, 966, 178701.

- Yang, Y.; Guo, Y. Unraveling salt stress signaling in plants. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 2018, 60, 796-804.

- Peng, Y.X.; Zhu, H.Y.; Wang, Y.T.; Kang, J.; Hu, L.X.; Li, L.; Zhu, K.Y.; Yan, J.R.; Bu, X.; Wang, X.J.; et al. Revisiting the role of light signaling in plant responses to salt stress. Hortic Res-England 2025, 12. [CrossRef]

- Hiyama, A.; Takemiya, A.; Munemasa, S.; Okuma, E.; Sugiyama, N.; Tada, Y.; Murata, Y.; Shimazaki, K. Blue light and co2 signals converge to regulate light-induced stomatal opening. Nat Commun 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- Schuerger, A.C.; Brown, C.S.; Stryjewski, E.C. Anatomical features of pepper plants (capsicum annuum l) grown under red light-emitting diodes supplemented with blue or far-red light. Ann. Bot. 1997, 79, 273-282. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xu, W.; Jia, Y.B.; Wang, M.C.; Xia, G.M. The wheat gene is involved in the blue-light response and salt tolerance. Plant J. 2015, 84, 1219-1230. [CrossRef]

- Shimazaki, K.; Doi, M.; Assmann, S.M.; Kinoshita, T. Light regulation of stomatal movement. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2007, 58, 219-247. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).