I. Introduction

Nowadays, the most crucial issue in the field of contemporary technology is cyber-attacks. A malicious attack implies exploiting a system’s vulnerabilities for malevolent ends, such as stealing, altering, or destroying it. Malware indicates a cyberattack. Malware refers to any software or code specifically designed to damage a computer system, person, or organization. The word “malware” includes many threats such as virus species, Trojan horses, spyware, ransomware, adware, malicious software, wipers, and scareware. By definition, a malicious application is any code that executes without the user’s awareness or agreement [

1].

Malicious detection is concerned with detecting malicious software by keeping an eye on computer system activity and categorizing it as either regular or unusual. The speed, quantity, and the intricacy of spyware provide new challenges to the malware removal software economy. According to the most recent modern studies, analysts have started using ML and methods for analyzing and detecting malware using deep learning. Within malicious software, it’s done by initiating randomized feature elimination in the training in combination with methodologies for testing that assure the unexpected characteristics of the ML models. Naturally, it guarantees that the simulation’s processing about the given data diminishes the efficacy concerning adversarial trials, although the challenger discovers critical information. Beyond that, the multilayered autoencoders technique is implemented for detecting malware. The technique features an overzealous layer-wise training strategy that emphasizes training without supervision and even guided value adjustment [

2].

An ML-based malicious software scanning approach was suggested, along with a dynamic and static combination. Initially, the static, along with dynamic components of smartphone software, was discovered. Afterwards, the characteristics were vectored and applied for the development and verification of SVM. At last, the classifier based on SVM with the right settings might be applied for the detection of mobile device malicious software. By the research, the theory has helpful precision and call-back rates that indicate its accuracy and efficacy of the model. Furthermore, the ML is used to identify malware that is known to have a high identification rate among its existing forms; however, it may also pack a find for fresh hazardous algorithms [

3].

ML is an empirical method frequently used to evaluate complicated settings and find abnormalities fast, beating people in initial identification. It trains with previous information to determine known assaults and finds anomalies for unidentified attacks. ML models differ, leveraging trained learning for big datasets with labels or semi-supervised methods for limited data. Outcomes rely on the chosen characteristics and data effectiveness, rendering gathering information a vital stage. This article explores ML approaches and their use in recognizing anomalies across multiple network environments [

4].

Throughout this research work, a ML-based spyware detection technique is created (for PC systems) that involves the feature collection extracted from the contents of a Portable Executable (PE) file header. It is employed for checking whether the software currently executing has no malware or hazardous information. The system may also detect a zero-day virus in the built file. The 32-bit code and 64-bit code systems running Windows employ PE file extensions for program execution. Malware analysis statistics suggest that the highest reported file type is PE.

The outcomes of this research are:

It presents a full overview of the ML sorts.

Comprehensive inspection and debate of ML techniques in anomaly detection techniques are introduced.

Several network conditions utilizing ML for malware detection are examined.

The features and advantages of each ML model in malware detection are outlined.

II. Literature Review

The present research examines ML techniques for identifying malware, comparing Support Vector Machine (SVM), Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), and Decision Tree (DT) classifiers. DT attained the accuracy (99%), preceding CNN (98.76%) and SVM (96.41%), with low false positive rates (FPR) of 2.01%, 3.97%, and 4.63%, respectively. Using a static evaluation based on PE data, the paper reveals that ML algorithms can accurately identify harmful from harmless material without processing. The dataset utilized was acquired from the Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity, showcasing the possibility of DT as the accurate classifier for identifying malware [

5].

A method based on ML provides the ability to detect the Windows operating system’s virus. The recommended strategy captures several aspects of the PE header file and matches them with the taught ML algorithm and presents the outcome as being malevolent or clear. In this work, six separate ML approaches are applied for detecting malicious software in OS. The findings are evaluated according to support, recall, accuracy, F1-score, and precision. The findings of the test reveal that excellent results were extracted by the random forest that compared to other algorithms with 99% accuracy and precision [

6].

This research provides a unique strategy for identifying sophisticated malware with precision, defeating the limits of standard signature-based approaches. By evaluating 11,688 samples of malware and 4,006 benign applications, classifiers such as Random Forest, LMT, NBT, J48, and FT were assessed according to efficiency and errors. The findings indicated that all classifiers obtained > 96.28% precision, exceeding prior research (~95.9%), with Random Forest performing at ~97.95%. The methodology efficiently identifies unidentified malware and may augment signature-based approaches [

7].

Osama abdelrahman et al. [

8] To identify the abnormality on 10 benchmark datasets, the scientists examined many unsupervised methods. They made use of KNN, LOF, OCSVM, Connectivity-Based Outlier Factor (COF), Cluster-Based Local Outlier Factor (CBLOF), and Histogram-based Outlier Score (HBOS) were among the tools they used. Also, they had trouble distinguishing anomalous signs from others. The effectiveness of these methods for different kinds of datasets was compared by the authors. including high-dimensional spatial data on a vast scale. Furthermore, they employed AUROC combined with the precision track and position power as effectiveness measures to analyze and compare each of these techniques’ performances. Consequently, they discovered that, in comparison to the other algorithms, KNN and LOF algorithms outperformed these others. They choose between these two techniques based on computing time, Based on computation time, they choose one of these two methods; for low-dimensional space datasets, the AUROC is 98%, whereas for large-dimensional space datasets, it is 54%.

Xin ma et al. [

9] collected a sizeable database of over 50,000 Android devices software and developed it utilizing 4 recognized ML algorithms (Random Forest, J48, JRip, and LibSVM) with ten-fold cross-validation. However, on common dimensions, databases did not perform in the field.

A selection from established ML techniques could be used for malware detection. As an example, [

10] created a method that utilized Bayesian categorization. [

9] applied the authorization data and the delivery of messages method as characteristics and applied the enhanced RF algorithm during identification. In a similar way, [

11] employed an ML methodology to examine malware detection as well. In addition to the typical ML approaches, [

12] also employed applied learning procedures, and Droid Analyzer used a DL method to carry out computerized investigations into malware characteristics [

13].

The solution offered leverages analysis and AndroGuard to gather data generated by Android-based applications, demonstrating 96.24% precision in malware detection utilizing numerical accelerators and ML techniques. Investigators examined techniques on a dataset of androids, which included This method data set, during which initial training reached 98.9% accuracy, outperformed prior models. Concerns on database production have been addressed using erroneous revenue margins χ2 evaluations for homogenization, as well as a removing-it approach to combine records using demographic attributes. Such ideas highlight possible ways for malware identification for Android and information enhancement.[

14,

15,

16]

DL algorithms, together with stat features, have shown significant accuracy in recognizing encoded and non-encrypted cryptography interactions, exceeding basic algorithms incorporating Net flow properties. These techniques offer speedier outcomes for detection and quickly fix gaps in data among malware groups. Applying informed by data quantitative methodologies, experts generate essential knowledge through enormous datasets, enabling anomalous discovery & preventing expenditures. Their ability to ingest periods of time data as well as solve intricate challenges enables DL to be a valuable tool towards malware identification and security.[

17,

18,

19]

Malware detection has major issues related to software encryption and bundling tactics. To tackle this, a novel DL architecture is being designed to effectively detect malware varieties. Furthermore, a revolutionary architecture merging techniques using signatures with genetic algorithms (GA) increases recognition abilities, providing protection against equally existing and growing risks of malware. The combination of this method boosts accuracy and resilience in malware detection. [

20,

21]

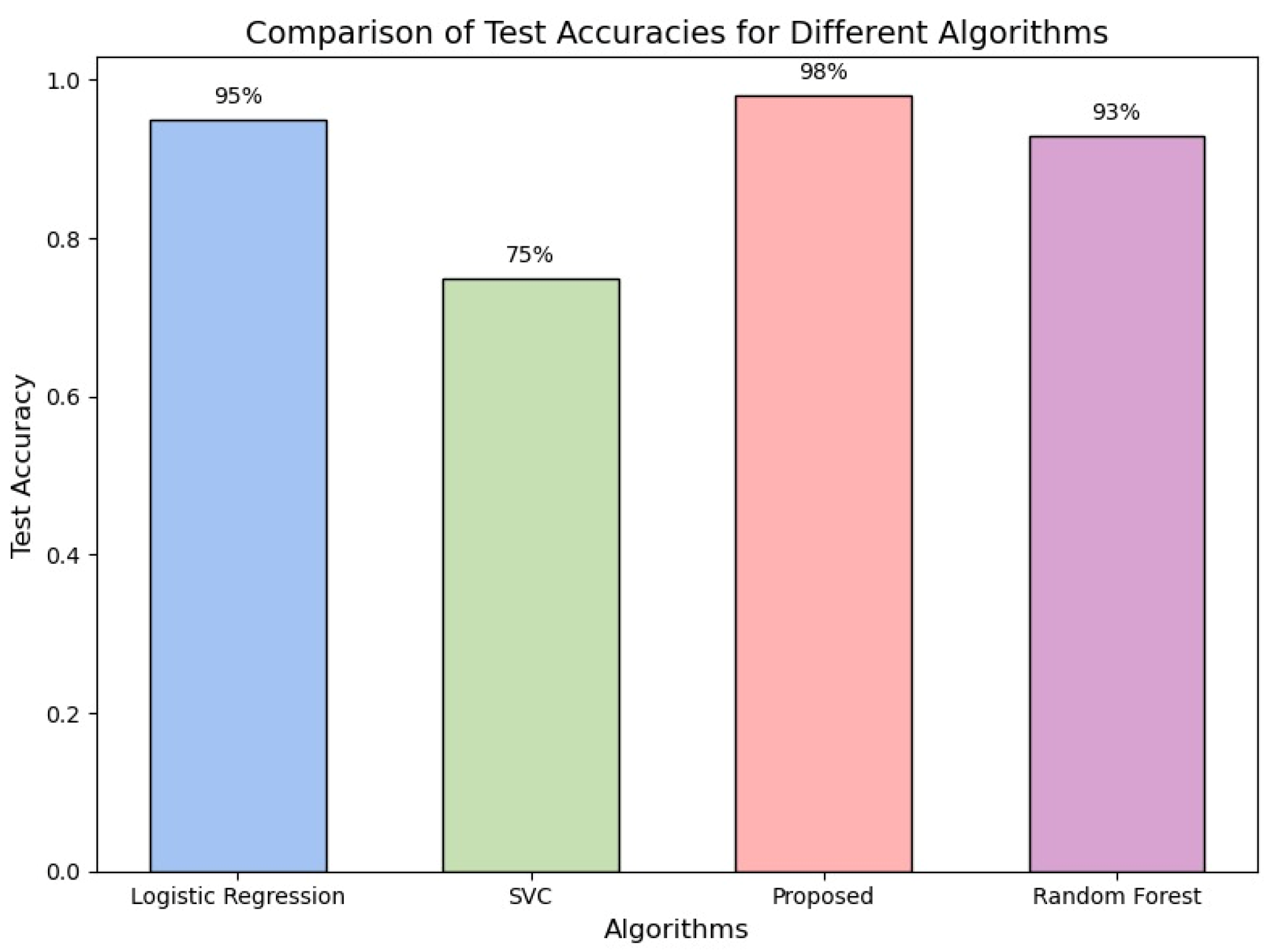

In malware detection, machine learning approaches have shown encouraging outcomes, with high precision and low false positive rates. In many experiments, the J48, Random Forest, and DT classifiers demonstrated performance with precision over 97%. These techniques properly separate fraudulent activity and harmless files using unchanging examination of Portable Executable (PE) characteristics. Through the resolution of the shortcomings of conventional signature-based techniques, advanced techniques like ensemble learning and machine learning models further improve identification capabilities. Recent studies emphasize GB and J48 as trustworthy classification algorithms, offering highly accurate and effective malware detection.

III. Proposed Methodology

The following part covers a suggested ML-based detection of malware solution on Windows as an OS that retrieves information and utilizes data to identify how well an application is free of malware or dangerous.

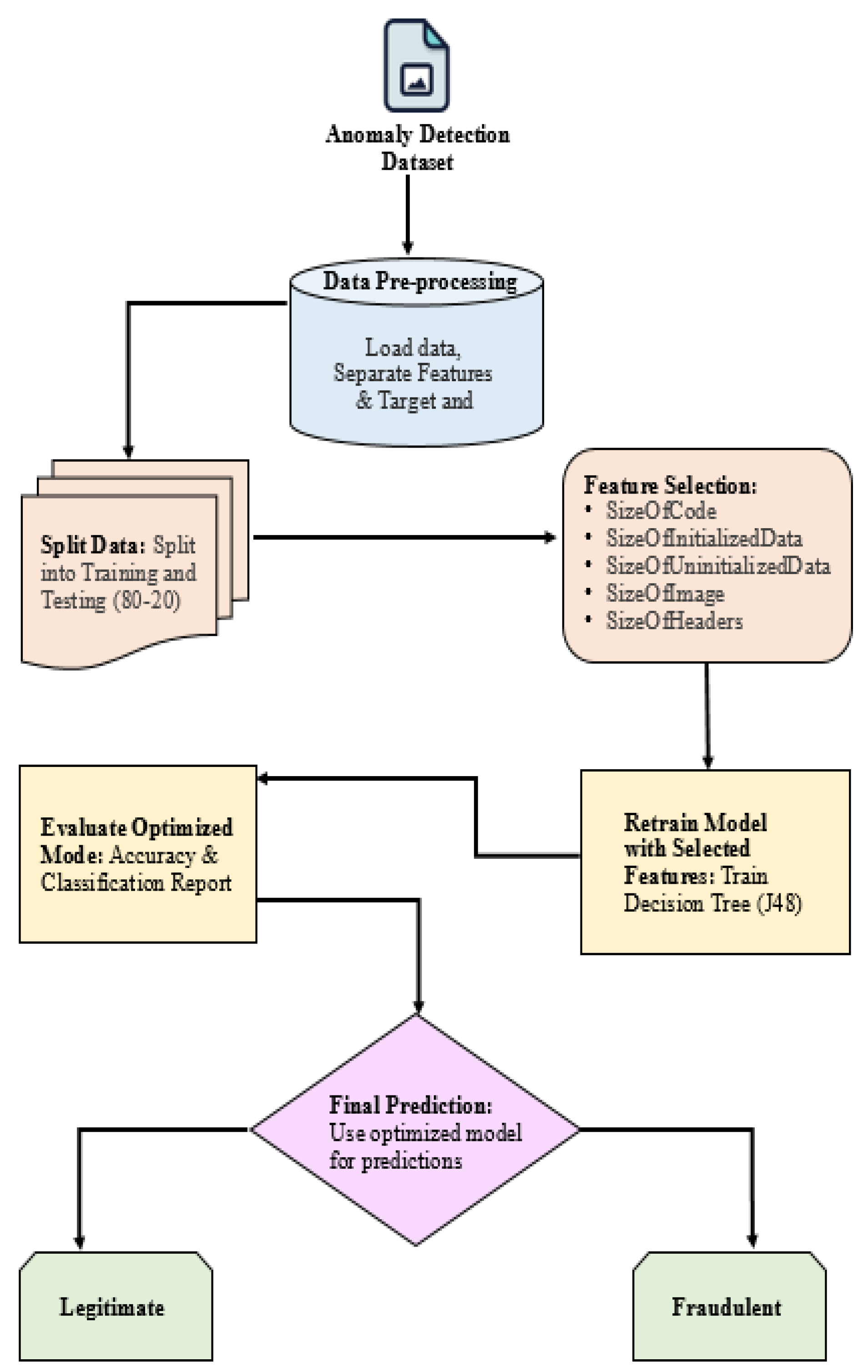

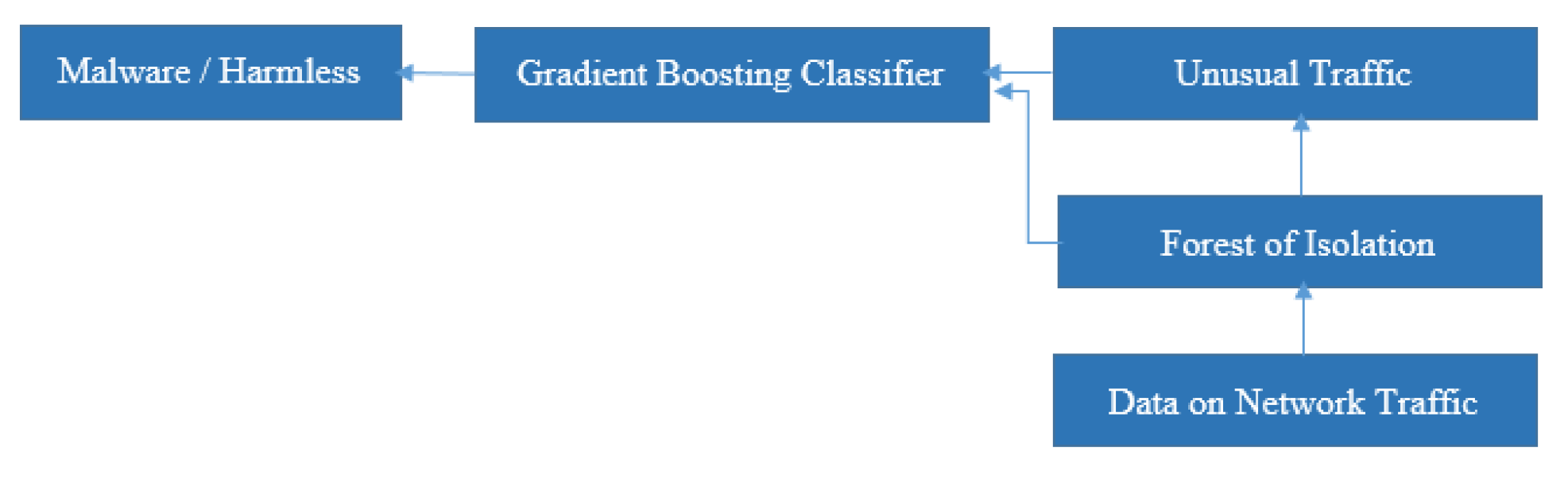

Figure 1 displays the framework of the proposed system. The following sub-sections cover such layers in depth.

A. Malware Dataset

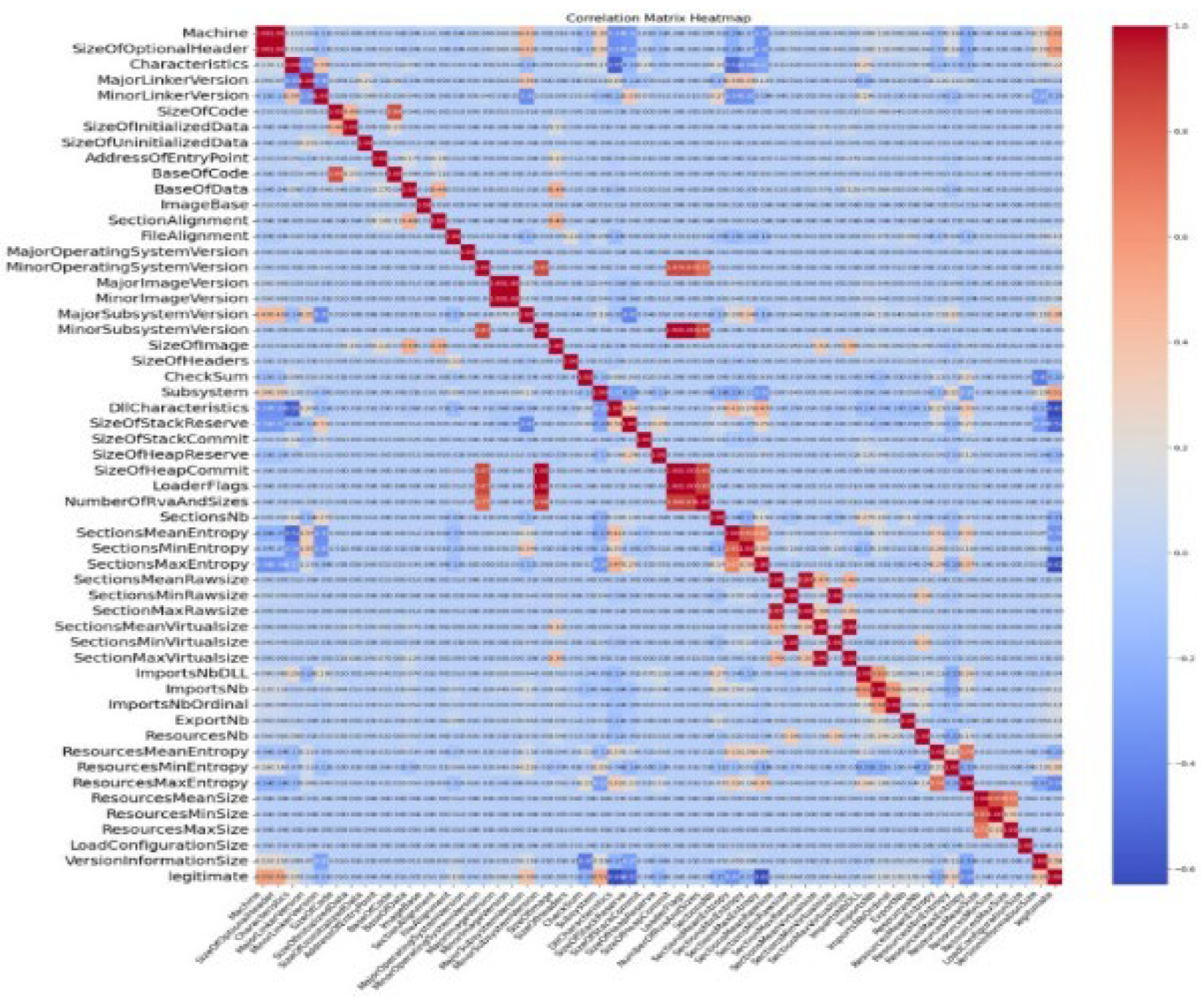

This analysis relies completely on data supplied by the source. The set contains several records that contain log files for a variety of malware. These retrieved data characteristics may be utilized to train a wide range of models. Approximately 51 different kinds of malware were discovered in the specimens. More than 138,049 dataset highlights from various places were gathered; the database contained 57 columns and 138,049 rows in

Figure 2.

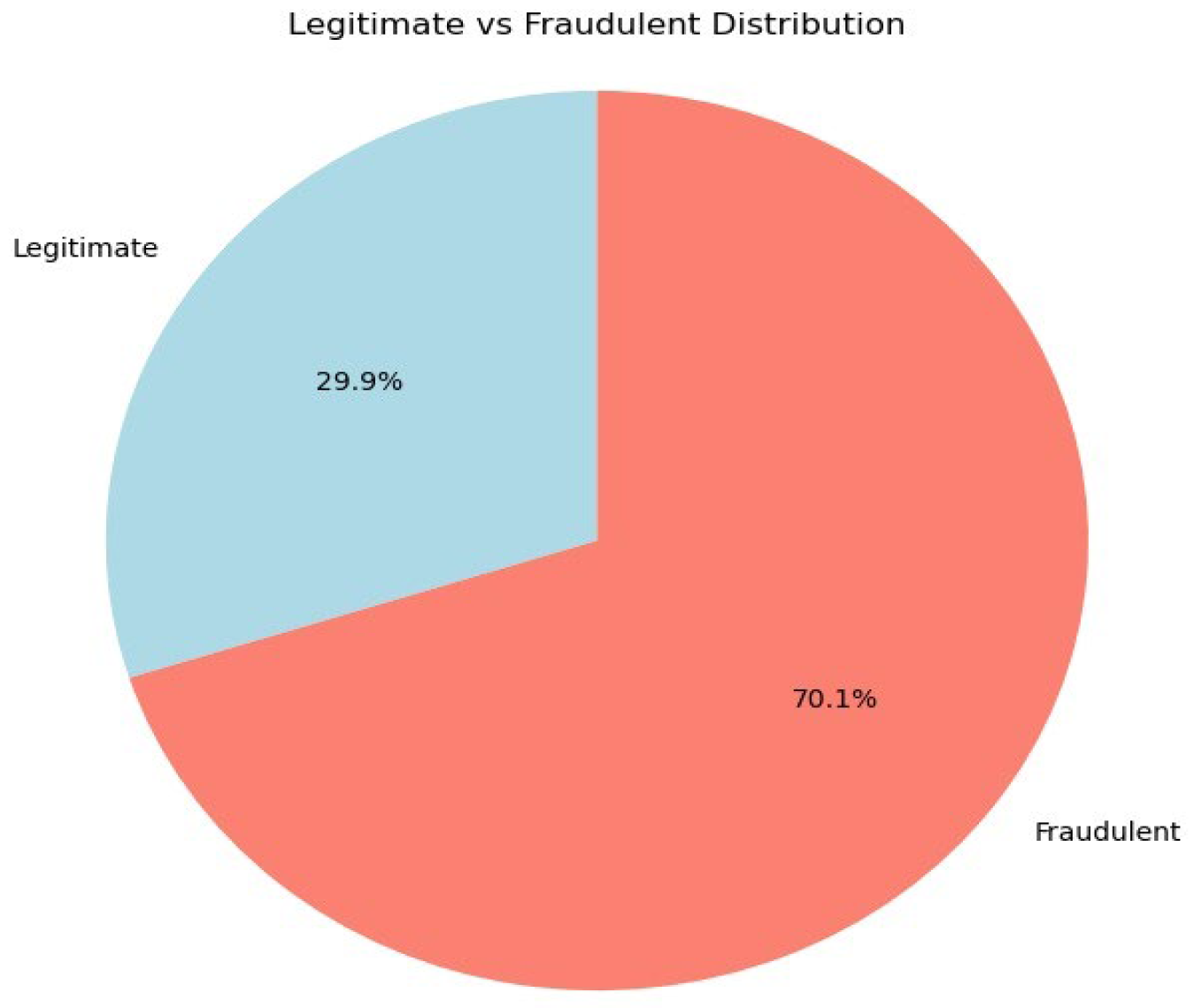

Figure 3 has the legitimate and fraudulent data represented.

B. Pre-Processing Layer

Data pre-processing was undertaken to reduce contaminants and prejudice prior to deploying ML models. After checking, no data gaps were discovered. Features like Name, MD5, and Loader Flags were removed from the information set since they were deemed irrelevant. With the help of Python’s Extended Tree Classifier, the Gini index served as the splitting criterion for this ensemble-based method, which made use of DT principles. The duration for training was decreased, and efficiency was increased by the pre-processed aspects.

Data Splitting: The pre-processed dataset is divided into 80% training and 20% testing, i.e., 80:20. The dataset is split into training and testing halves using a method known as the train-test split. When used properly, this technique divides the dataset according to the percentage of the split. The ML model is trained by applying algorithms to the training dataset. The efficiency provided by the acquired categories will be evaluated using the testing dataset. For training and testing purposes, the dataset included 138,049 data instances, with around 27,610 examples per segment.

C. Prediction Layer

ML algorithms may now be trained and tested on the pre-processed and segmented dataset.

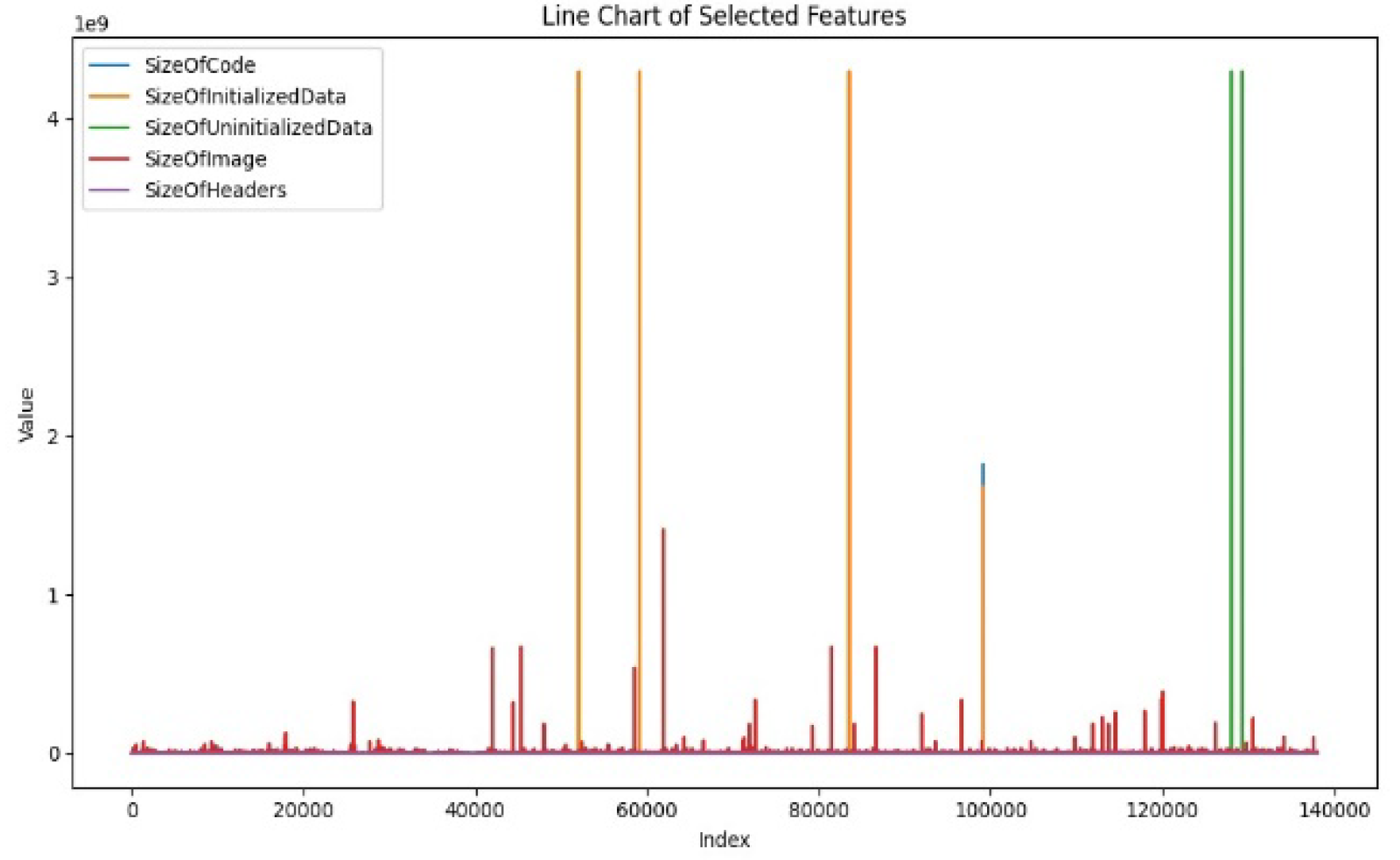

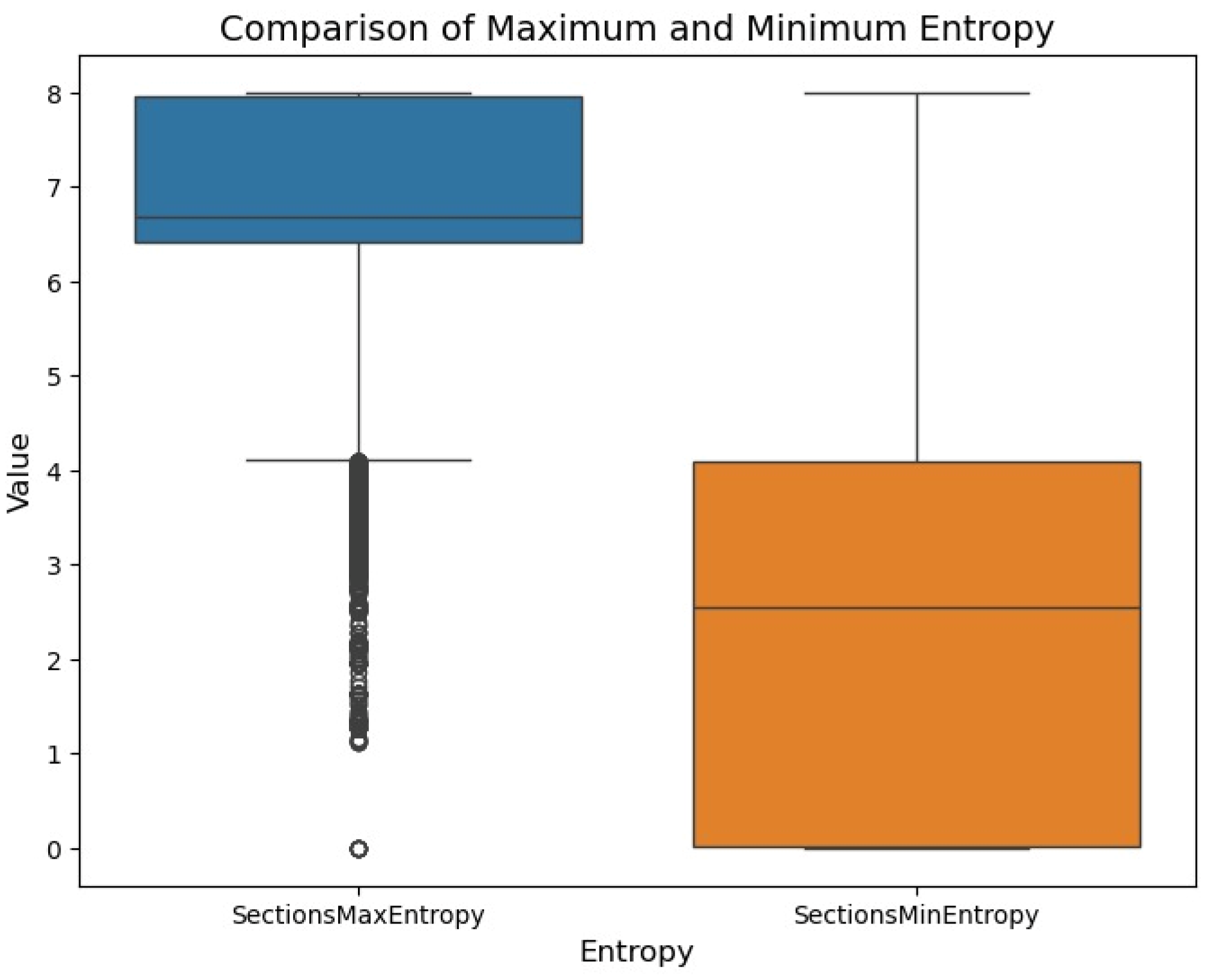

Figure 4 shows several selected features. The proposed hybrid model, which is GB and J48, is used at this stage to identify malware using selected features. Comparison of Maximum and Minimum Entropy as shown in

Figure 5.

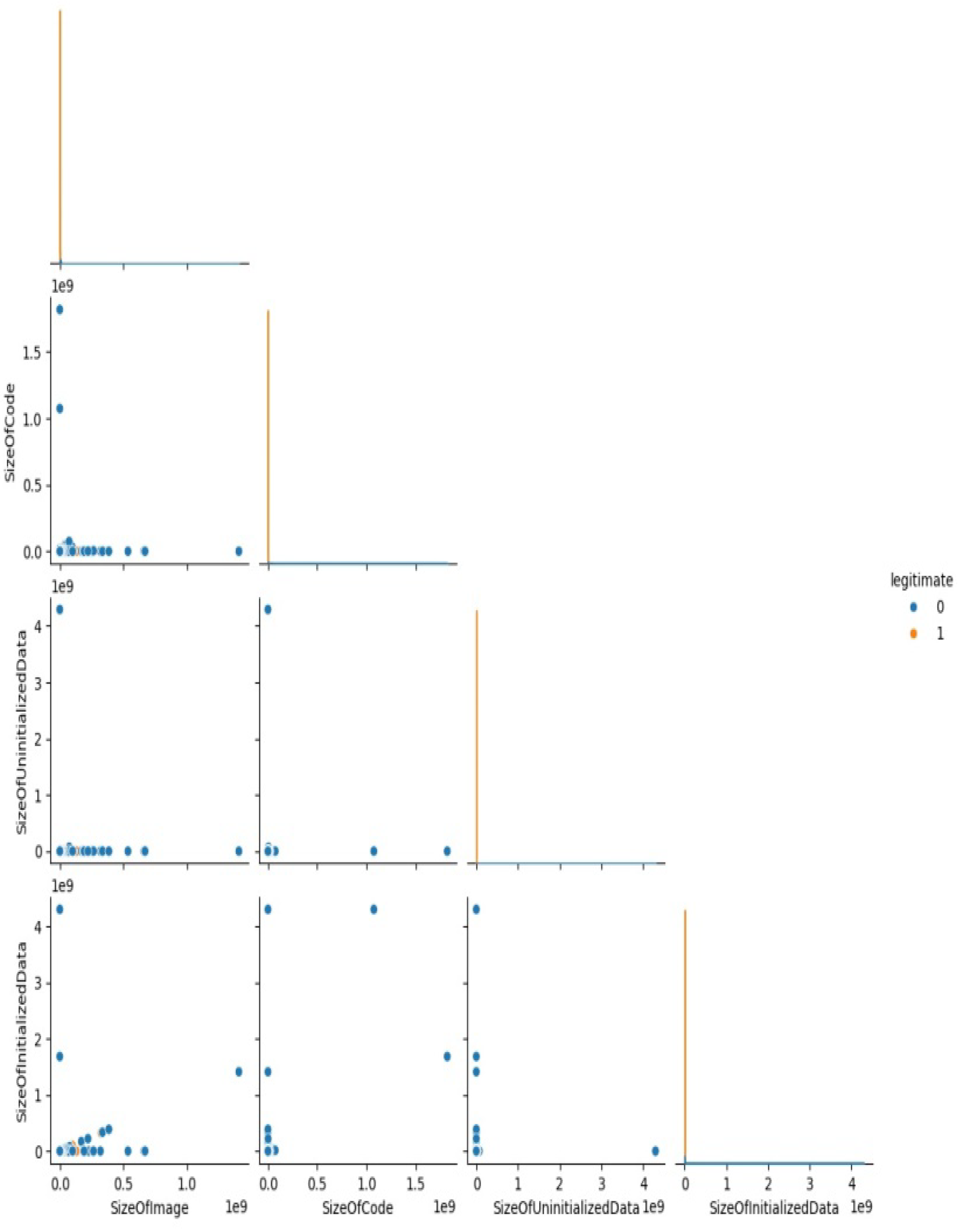

The scatter plot visualizes the connection between fundamental variables such as size of image, code, initialized data, and uninitialized data. While showing disparities between legitimate (1) and non-legitimate (0) data, it reveals clusters, suggesting probable patterns relevant for categorization as shown in

Figure 6.

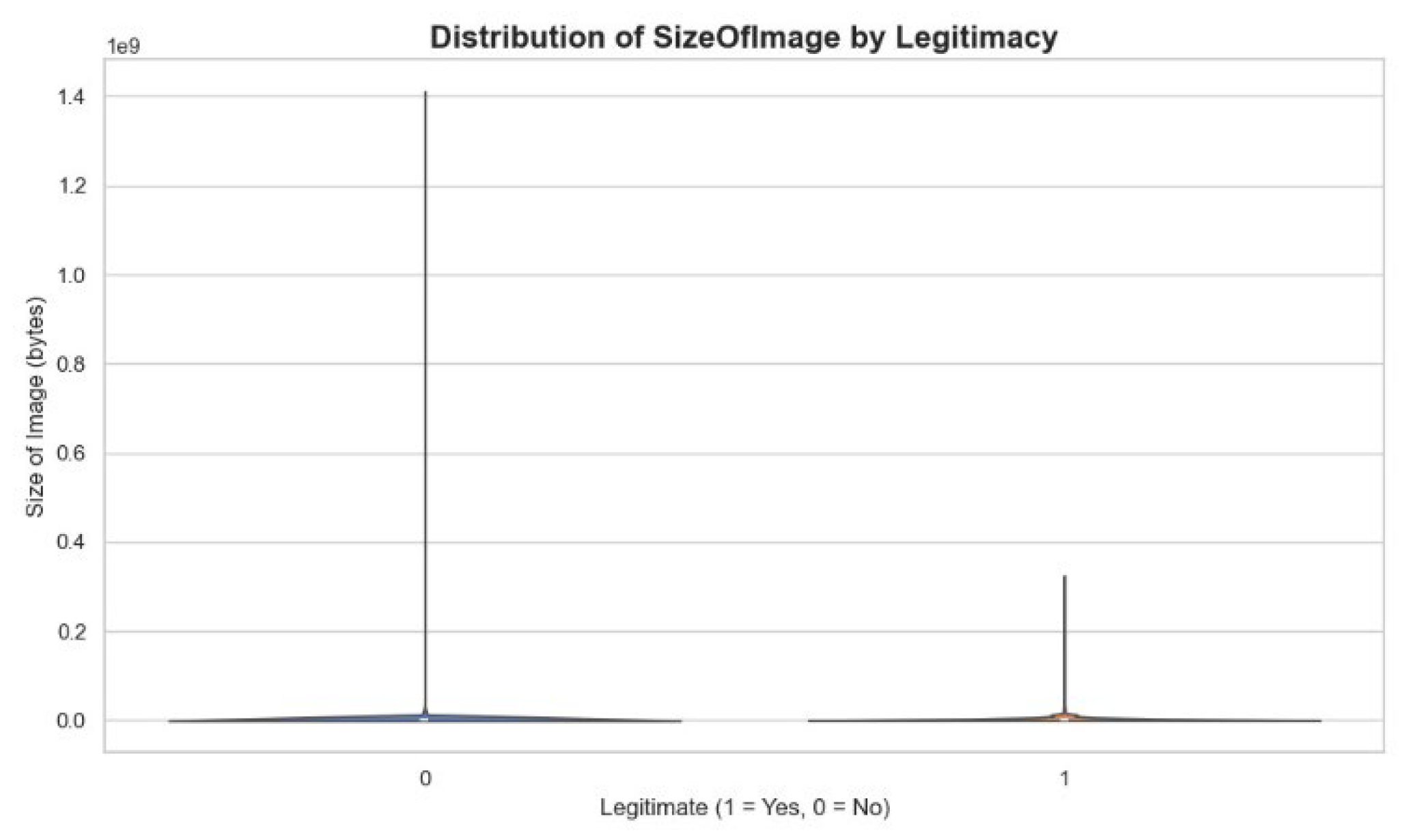

In

Figure 7, the dimension of file propagation among legitimate and non-legitimate files is examined using the size of the image feature. Non-legitimate files are displayed with dimension fluctuations in greater, meaning that binary size might be a differentiating indicator of the malware identification.

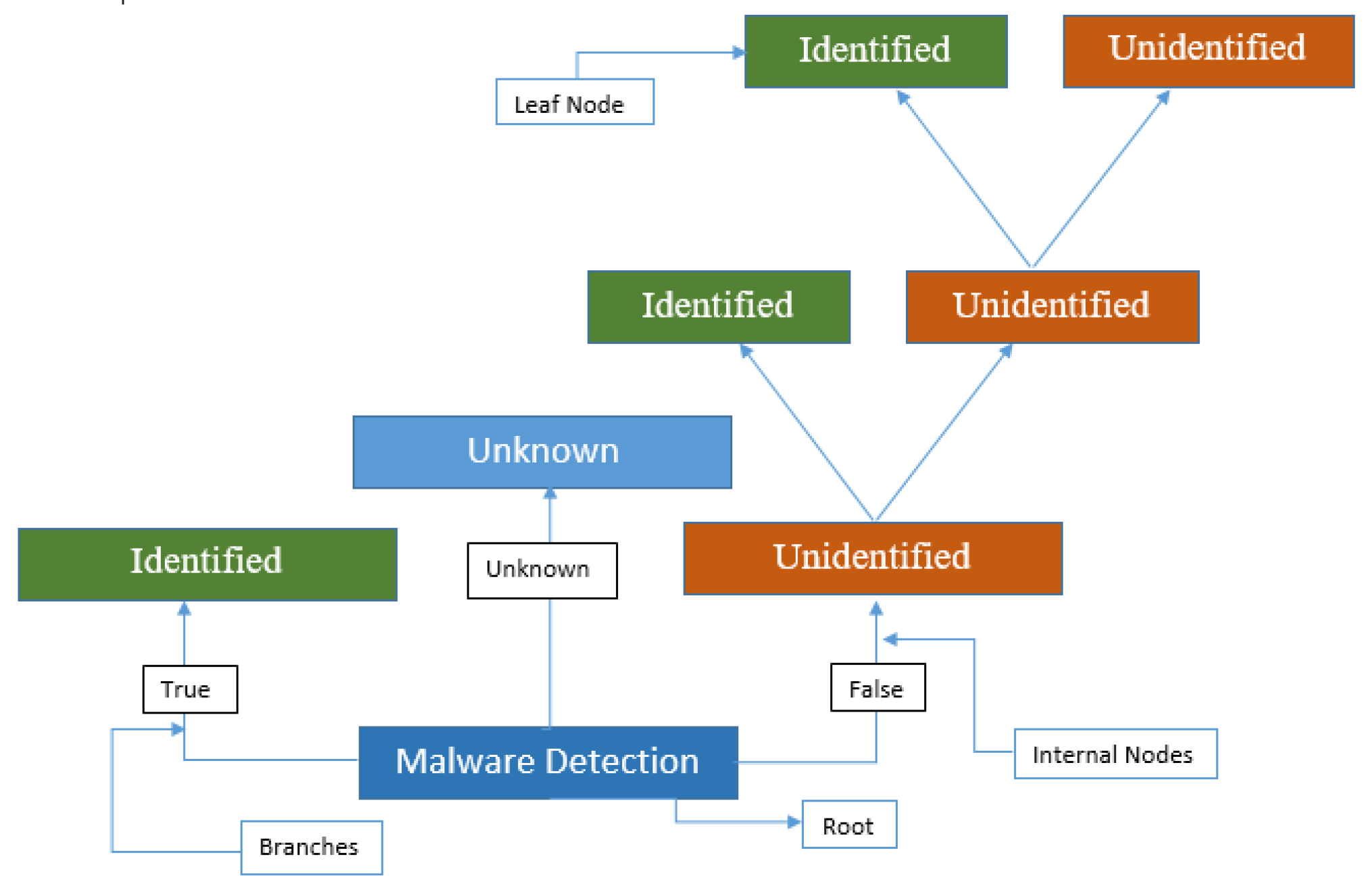

a) J48:

A J48 is a method for supervised ML used for classification as well as regression analysis of huge, intricate datasets and uncovering correlations. With leaves standing in for choices, it arranges data into a tree structure, branching into subgroups according to attribute values from the root. J48 operations comprise dividing (splitting data), trimming (streamlining the tree

’s structure by transforming branches into leaves), and tree selection (choosing the shortest tree that suits the data). With root attribute identification, algorithms such as C4.5 and Decision Tree (DT) are often used. J48 makes decisions by inductively drawing conclusions from independent inputs and dependent outputs.

Figure 8 shows an example of a J48.

b) Gradient Boosting:

GB was used to effectively manage data sets that were imbalanced while malware traffic made up a very small portion of network usage by classifying anomalous discovered by the isolation forest into harmless or malicious categories. It built successive theories, gradually improving projections by fixing errors in earlier models. It discovered essential characteristics of networks for differentiating malicious from harmless traffic after receiving training on annotated traffic records. In addition to improving adaptability over unexplored information, the gradient descent efficiency reduced classification errors. By incorporating weaker predictors into an accurate model and applying heavier weights to erroneous data, it raised precision and reduced bias against the overwhelming class. By providing information on key attributes, feature importance ranking improved clarity.

Figure 9 shows an example of a GB.

E. Experiemntal Analyzis

For experimental analysis, a computer with an Intel 1.70 GHz Core i5 processor CPU and 8 GB of RAM has the Scikit Learn Python library loaded. ML Various approaches are employed to identify malware in the dataset. The division stored information has been used to test the accuracy of the models in the testing and training divisions. The following metrics are computed for each of the classifications: accuracy of models, recall, precision, the F1 score, and support. (

Table 1)