1. Introduction

Ransomware is dangerous software that hides files or restricts system access and then demands payment to unlock or release them. The most common ways to deliver ransomware are either by phishing or email attachment, for which the victim has to open the attachment, and the attacker misleads the victim to open such links, which leads to ransomware being entered into the machine and making destruction [

1].In the escalating cyber threats landscape, crypto-ransomware is a formidable risk to home users and enterprises. The increased prevalence of remote work has amplified the risk of ransomware infections due to the potential for less secure home network environments than traditional institutional networks. Cybercriminals have capitalized on this opportunity by employing sophisticated tactics such as social engineering and phishing attacks to distribute malicious payloads[

2]. Traditional ransomware attacks have posed significant economic and operational challenges, prompting the need for innovative detection measures.

Vigilant security measures and constant monitoring are vital to counter these persistent threats [

3]. Since 2018, crypto-ransomware attacks have been directed at companies in manufacturing, transportation, telecommunication, finance, public law enforcement, and health services [

4]; this is done because of the high economic profits that malware developers can gain from each infection. In 2019, the estimated financial damage caused by ransomware attacks in the United States was

$7.5 billion [

5].

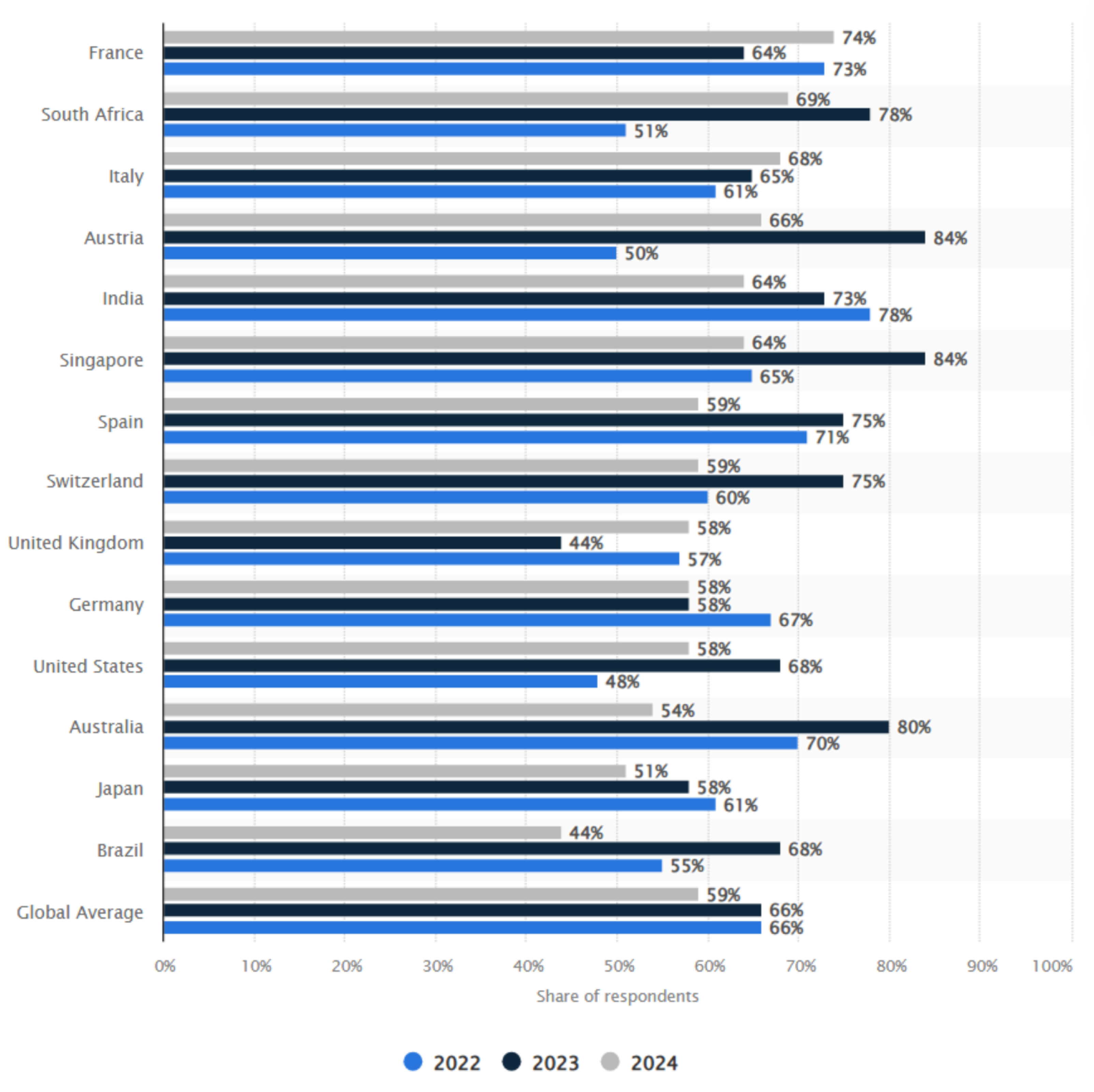

Figure 1 illustrates the share of organizations worldwide that experienced ransomware attacks from 2022 to 2024, broken down by country. Highlights an increasing trend in ransomware incidents in most regions. In particular, Singapore and Austria reported the highest prevalence in 2024, with 84% of affected organizations, showing a significant increase over previous years. Similarly, Brazil experienced substantial growth, with attacks rising from 44% in 2022 to 68% in 2024. Countries like Japan and the United States also exhibited steady growth, reaching 61% and 68% in 2024, respectively. In contrast, some countries, including the United Kingdom and South Africa, showed relatively modest growth or remained consistent over the years. The global average reflects a consistent rise in ransomware attacks, underlining the escalating cybersecurity challenge.

Nowadays, there are abundant ultra-sophisticated ransomware threats, and they pose serious risks to organizations throughout the world [

7]. This makes it almost impossible for the current defences to counter threats and protect organizations and their valuable data as novel and modern ransomware attack techniques are becoming highly frequent, necessitating significant demand for modern techniques for detection, too. Ransomware attacks are getting more challenging to address due to the emergence of more robust encrypting algorithms that give them the capability to avoid detection using signature; this indicates a recognition of the fact that there is a need for a rapidly adapting Ransomware detection system since the threats are on constant evolution.

While we’ve made good progress utilizing machine learning to detect ransomware, there are still some significant gaps. Many existing detection methods only look at the ransomware code when idle, a process known as static analysis. This approach can detect known dangers but frequently overlooks how ransomware behaves when active, such as how it interacts with files, network traffic, or system resources. These behaviors are commonly required for detecting newer or more complex ransomware [

8]. On the other hand, dynamic analysis observes ransomware as it runs, allowing a more profound knowledge of its real-time behavior [

9]. However, insufficient large and detailed databases track various ransomware types and behaviors.

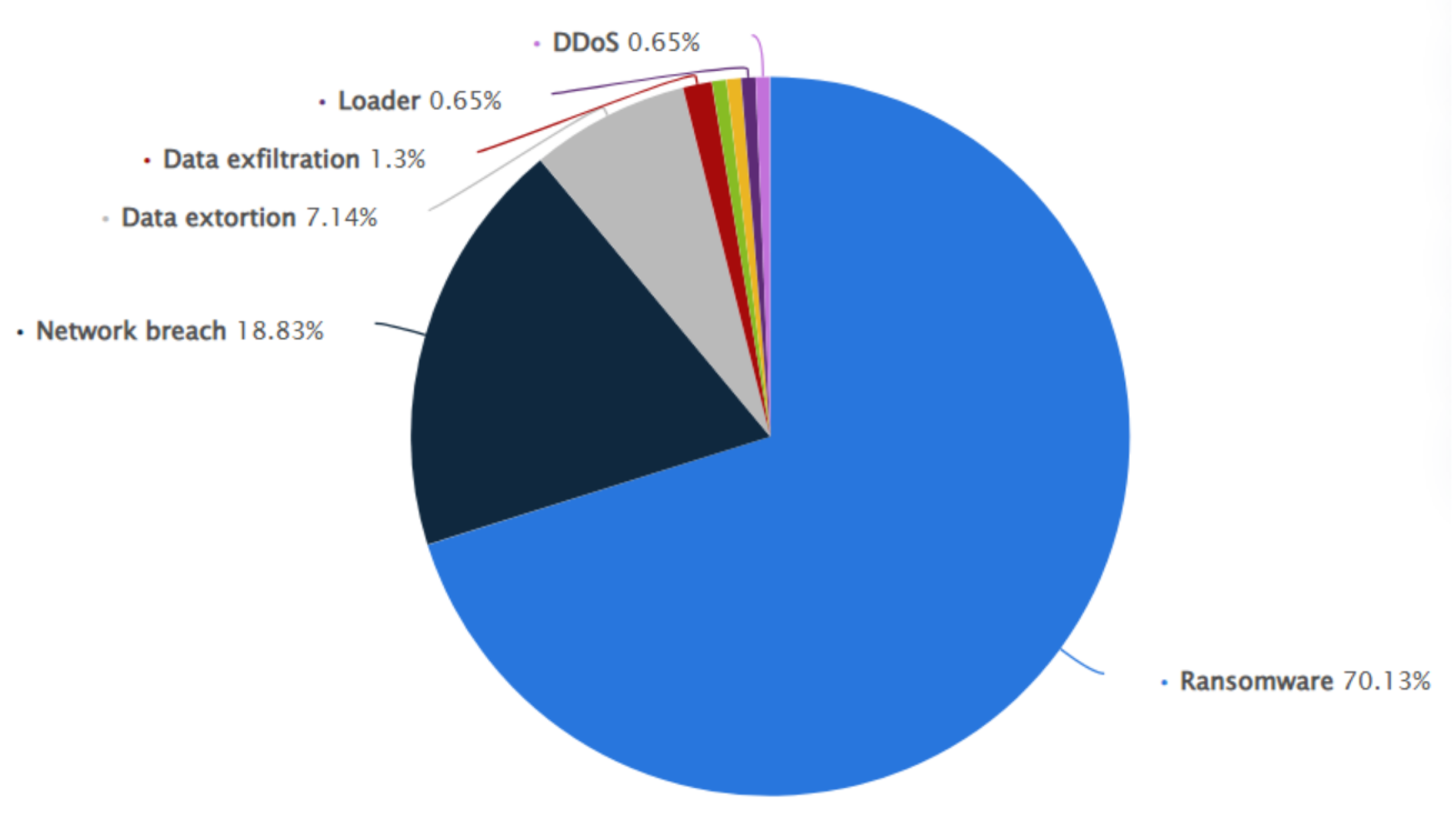

The pie chart presented in

Figure 2 provides the distribution of detected cyberattacks worldwide in 2023, categorized by type. Ransomware dominates the landscape, accounting for a staggering 70.13% of all detected attacks, showcasing its prevalence as a primary cyber threat. These figures underline the need for targeted defenses against ransomware while maintaining vigilance against other forms of cyber threats.

This paper [

11,

12] aims to suggest an ML-based solution for modern and sophisticated ransomware attacks. Therefore, our framework RanDEL’s main objective is to use dynamic feature datasets for detection, as static feature-based detection is less effective than before. With a dynamic feature dataset, the framework will ensure that any new forms of ransomware will be detected and that this method continues to be effective against new types of ransomware. Generally, detecting ransomware is becoming more complex as there are various malware samples with different signatures, such as hash, which is also considered a signature of a malware sample, which can be entirely changed by just adding a single dot (.) in a file. Therefore, dynamic detection [

13,

14] is considered to be more accurate and efficient as compared to heuristic or signature-based detection, and changing the behavior of a ransomware sample is a difficult job as it needs deep knowledge about ransomware and also it requires an understanding of coding. For dynamic-based detection in ML, we need a dataset with dynamic features to detect any anomaly before it makes any destruction. For collecting dynamic feature dataset, ransomware samples are run in a sandbox, and more than 300 Indicator of Compromise are stored in JSON files; later most relevant and nonredundant 50 features are selected for creating a dataset; this dataset contains various features according to ransomware stages which include multiple features such as process memory, target, buffer, signatures, network activity, system calls, file activity, registry calls, network protocols used etc [

15]. We have developed a dynamic ransomware detection framework and found features according to the stages of ransomware using threat intelligence. We have selected features by measuring their effectiveness and chosen the best optimal features, and have performed ransomware classification [

16] into good-ware, locker ransomware, and encryptor ransomware using these features. In this paper, we have suggested an ML framework that used Gaussian Naive Bayes and Multi-Layer Perceptron, and later on, we built an ensemble model of these two models. We applied various techniques like voting [

17], staking, and bagging and made a comparison. We aim to use Ensemble Models to increase accuracy and make models more efficient. This allows the detection system to give detection based on multiple models [

18] by covering the weaknesses of standalone models, making it more reliable and capable of detecting a wide range of ransomware attacks.

We have compared ensemble and standalone models and tried to find answers to the question: How do ensemble models mitigate the limitations of standalone models in ransomware classification? Ensembling is a powerful method that reduces the weaknesses of standalone models and combines their strengths, leading to better performance than standalone models [

19]. The ensemble also helps resolve overfitting issues in the case of complex models as it calculates the average prediction of multiple models, making the ensemble models less sensitive to noise in training data. Each ML model has some strength. So, we can leverage the strength of each model by combining them to achieve better performance. How do machine learning techniques offer the best trade-off between computational efficiency and resource consumption for ransomware detection and classification? We have achieved higher accuracy in the case of ensemble models, which is highest in the case of bagging classifier

99.25%, but resource consumption for bagging is also higher as it has consumed

2.46 Mbs of memory, which is the highest consumption of our all experiments, so it can be said that both techniques have their pros and cons we have to select one based on our requirements.

We have used three ensemble techniques: Voting [

20], staking, and bagging.

Voting: We have used a soft voting classifier, which combines many models’ predictions via majority voting. This ensemble method combines predictions from multiple models via majority voting or averaging, typically resulting in improved overall performance by exploiting the capabilities of different classifiers. This strategy helps to strike a compromise between accuracy and computing efficiency [

21].

Stacking: This ensemble technique combines many models with the predictions of numerous base classifiers serving as inputs to a final estimator. Stacking produces highly accurate predictions, although it can be computationally expensive due to the extra layer of model training [

22].

Bagging : this ensemble method trains many base models on distinct subsets of data, which reduces variance and frequently results in high accuracy. Bagging, particularly with models such as decision trees, has been shown to improve performance but can be computationally expensive, especially when huge datasets are used [

23].

This study intends to achieve the following objectives:

To find out the ransomware features and their effectiveness according to each malware stage using threat intelligence.

To perform family classification of ransomware using Ensemble Learning and Threat Intelligence.

To optimize the Ensemble Learning Framework.

To compare standalone ML models with Ensemble Models.

To compare our solution "RanDEL" with existing solutions.

2. Literature Review

In the paper [

24] analyze network traffic metadata and TLS protocol aspects to detect encrypted malware. It depends on the effectiveness of feature selection and may not apply to previously unknown malware. Investigate using raw bytes of header fields in encrypted flows to train deep learning models. SVM, RF, and MLP have been proven to be accurate classifiers for detecting encrypted malware. The limitation of this research is that it depends on the efficacy of feature selection and may need to be more effective in generalizing unknown malware—a trade-off between precision and speed. SVM can be slower than RF. Future research includes using the raw bytes of header fields in encrypted flows to train deep learning models and investigate the resource utilization of additional steps, such as feature extraction. The paper [

25] analyses file-sharing network traffic for patterns that indicate ransomware activity. Features include file access frequency, number of files accessed, and command sequences. It uses a neural network with three hidden layers to classify ransomware activities. Extracts characteristics from network traffic and decreases sample size for more effective training. This research is limited to file-sharing circumstances, may not detect fileless ransomware, and necessitates a static training dataset. Training requires a vast dataset and may need to be more effective against undiscovered ransomware variants. Feature extraction may result in bias or information loss. Future research plans to improve adaptability to new ransomware strains via adaptive training methods. Discover several neural network designs and feature engineering techniques. Investigate different feature extraction approaches and methodologies for preserving information while lowering sample size. In the paper [

26], the raw traffic data is used to classify encrypted communication and detect malware. Learns features automatically from raw traffic data, reducing the need for human feature selection. The limitation of this research is that it requires a large dataset for training and may not be successful against completely new traffic patterns. In comparison to handcrafted elements, they may be more challenging to interpret. Future research plans to investigate transfer learning strategies for adapting to new surroundings. Investigate approaches to improve model interpretability.

In the paper [

27], the research focuses on analyzing TLS communication and encrypted traffic using cryptographic techniques, metadata, network behavior, machine learning, and deep learning models for pattern detection and identification. The limitations of this research include privacy problems, performance costs, and potential adversarial attacks that limit the usage of cryptographic algorithms and protocols, which necessitate big datasets and significant computer resources and may be challenging to interpret. Future research explores privacy-preserving TLS interception strategies, cryptographic inspection techniques, advanced feature extraction, machine learning, TLS features, and lightweight deep learning models for accurate fingerprinting. In the paper [

28], authors analyze encrypted traffic metadata (TCP characteristics) to detect harmful patterns and select and train the best machine learning models. Can detect variations from regular traffic patterns that indicate the presence of malware. The limitation is that it depends on the availability of various training data. The quality and quantity of training data may hinder performance. It may be sensitive to data noise and outliers. Future research includes learning about advanced AMB techniques and hyperparameters and exploring anomaly detection approaches designed explicitly for encrypted traffic to assess the impact of TLS-related features on anonymized business data. In the paper [

29,

30], authors use Markov chains to express sequential packet length information. Use Tree-Based Information Gain (TIG) for feature selection and classification. Graph neural networks are used to record packet-level associations. A feature selection network that automatically chooses relevant features. Limitations include lower accuracy than other approaches but faster training. Sensitive to noise in training data requires tremendous computational resources. With noisy data, the model may overfit. Future research will investigate ways to enhance accuracy while retaining the computing economy. Create more powerful TIG-based classifiers or investigate different feature selection approaches. Investigate more effective graph neural network topologies. Investigate regularization approaches to address overfitting.

In the paper [

31], authors utilize machine learning algorithms to categorize malware, detect anomalies, analyze TLS handshakes and DNS queries, and extract complex patterns from raw traffic data. This method’s limitation is that it depends on good feature selection, may be limited by the availability of labeled data, may fail to identify complicated patterns, and is noise-sensitive. Future research will explore deep learning techniques, combine statistical features, create efficient methods for TLS metadata and DNS traffic, and explore efficient architectures for noisy data. In the paper [

32], authors use machine learning algorithms to identify ransomware samples in a controlled environment, identifying relevant and nonredundant features for classification. The limitations include requiring specialized software (sandbox) and not being able to detect all attack behaviors, depending on the quality and diversity of training data. It may be subjective and necessitate domain expertise. Future research explores methods to enhance sandbox realism, manage concept drift, and analyze automated feature selection algorithms based on information gain or other parameters [

33]. In the paper, the [

12] tool accurately and interpretably classifies encrypted malicious network traffic using TLS handshake metadata, DNS contextual flows, and HTTP headers. The limitation includes that it relies on unencrypted metadata, which may be limited in some cases. It may be less effective against new or developing threats. Future research will explore long-term behavior patterns, incorporating honeypot and malware data, content-aware features, and horizontal correlation systems while experimenting with machine learning algorithms and feature engineering approaches.

The paper [

34] uses intra-flow data analysis and machine learning models to identify threats in encrypted network traffic and classify them based on extracted features. It may not detect malicious behavior, particularly very sophisticated or well-hidden, depending on the quality and quantity of training data. Future research includes the study of the uses of intra-flow data analysis and machine learning models to detect risks in encrypted network traffic, experimenting with various algorithms and feature engineering strategies to achieve peak performance. In the paper [

35], Machine learning algorithms like SVM, XGBoost, and random forest are utilized to classify encrypted HTTP traffic as malicious or benign, extracting beneficial characteristics directly from models, depending on the quality and quantity of training data. Critical aspects may need to be captured, particularly for new or emerging threats. It may be susceptible to changes in malware behavior. Future research will explore various machine learning algorithms and feature engineering methods, explore complex feature selection strategies, and analyze adversarial attacks, aiming to develop robust processes and balance accuracy and efficiency. In the paper [

36], a machine learning model is used to analyze HTTP and HTTPS network traffic to detect malware infections, and its performance is measured using a standard assessment method. Malware behavior changes or network protocols can limit its capabilities, and real-world performance variances may not be fully captured. Efficient implementation and integration with existing security systems are necessary. Future research will enhance detection accuracy by incorporating TLS cipher suite and version information, exploring alternative evaluation methods, conducting real-world test scenarios, and evaluating system performance in real time. The paper [

37,

38], the malware identification process utilizes a neural language model to embed domain names. At the same time, an LSTM network is used to process network flows and capture temporal dependencies, depending on the availability of large-scale labeled datasets. The complexity of domain-name patterns may impose limitations. It may be susceptible to variations in network traffic patterns. Future research will investigate the different machine learning methods and feature engineering methodologies. Investigate more complex domain name embedding techniques.

In the paper [

39,

40] tool uses KNN classification and metric indexing to detect malware in HTTPS traffic, ensuring efficiency and accuracy while indexing the dataset based on specific metrics. The effectiveness of a classification method depends on the quality of the feature descriptor and the efficiency of the metric index. Future research will explore distance learning methods, data reduction techniques, and efficient KNN search algorithms to enhance classification performance. In the paper [

41], the system generates a higher-level representation of end nodes based on network traffic patterns and models communication patterns. It creates resilient fingerprints for HTTPS-based malware detection. The system’s effectiveness depends on network traffic patterns, which can be influenced by network conditions and may be limited by the variety of malware communication patterns. Future work will enhance detection accuracy and resilience, explore advanced pattern modeling techniques, and develop robust fingerprint generation methods for various contexts. In the paper [

42], the system analyzes HTTPS traffic to identify the operating system, browser, and application details, extracts valuable features, and trains a classification model to predict these aspects. The effectiveness of HTTPS traffic relies on sufficient training data, the complexity of traffic, and the availability of appropriate functionality, which network traffic patterns can influence. Future research should expand the study to include action classification and mobile devices. Discover new features and feature engineering methodologies. Experiment with various classification methods and hyperparameters. In the paper [

43], an automated machine learning pipeline uses multiple models and hyperparameter tuning to categorize encrypted malware traffic, selecting informative attributes for classification and analyzing TLS metadata for malware detection. Training and evaluation can be time-consuming, challenging to apply and interpret, and may be limited by the quality and availability of features. Future research will experiment with various models and techniques and explore ensemble strategies, advanced feature selection, and TLS metadata elements for malware identification efficiency.

In the paper [

44], the tool uses machine learning to monitor file-sharing data and detect ransomware activity, extract elements from network traffic, and train a model to identify traffic. The complexity of ransomware approaches, network traffic patterns, and the impact of ransomware behavior and network conditions may make it challenging to capture real-world deployment scenarios fully. Future research will expand detection to mobile operating systems, explore file-less ransomware, explore new features, explore machine learning algorithms, and conduct thorough testing across various environments. The paper [

45] study utilized a hybrid model combining CNNs and pre-trained transformers for ransomware attack classification, evaluating its performance using parameters like accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score depending on the quality and quantity of training data. The intricacy of encryption algorithms and ransomware variations may restrict their effectiveness. It is possible that real-world deployment scenarios still need to be entirely captured. It may be challenging to interpret sophisticated models. Future research will explore CNN and transformer topologies, their impact on adversarial attacks, and develop advanced feature extraction methods, evaluating their generalization capabilities and potential cybersecurity applications. In the paper [

46] algorithm uses real-world genomic data to assess its performance in calculating Jaccard similarity and genetic sequence similarity using high-performance methods for sparse matrix operations. The dataset size and complexity may limit possibilities, and its focus on detecting overlaps between lengthy reads may have limitations in whole genome comparisons. Future research will explore genomics similarity measurements, frameworks, and optimization strategies, integrate BELLA and Similarity sAt Scale for complementary applications, and conduct comprehensive benchmarking and scalability analysis. In the paper [

47], the algorithm uses real-world genomic data to evaluate its performance in calculating Jaccard similarity and genetic sequence similarity using high-performance methods for sparse matrix operations. The dataset size and complexity may limit possibilities, and its focus on detecting overlaps between lengthy reads may have limitations in whole genome comparisons. Future research is to investigate alternate similarity measures and applications outside of genomics, as well as alternative frameworks and optimization methodologies, and to conduct thorough benchmarking and scalability studies. Some recent researches [

48][

49] focused on malware detection in general rather than ransomware in particular. This research has purposefully concentrated on ransomware detection and classification to address this pressing and expanding issue due to the notable increase in ransomware attacks. We have studied and analyzed recent studies like [

50][

51]. We have observed that these studies have used static features for detection, so RanDEL is focused on dynamic features to make ransomware detection and classification more efficient. Further, after studying some recent survey papers like [

52][

53], it has been observed that work is needed to be done for ransomware classification using dynamic features to deal with new ransomware variants and to deal with obfuscated and polymorphic ransomware. The review process for this study focused on selecting papers based on the dynamic features of ransomware detection. The initial identification phase involved a comprehensive search across academic databases, including Google Scholar and Connected Papers, using queries such as "Ransomware Classification Using ML," "Behavior-Based Ransomware Detection," and "Dynamic Features in Ransomware Classification." We have chosen these studies for comparisons, shown in

Table 1.

3. Problem Statement

The increasing frequency of sophisticated ransomware attacks poses a considerable challenge to cybersecurity. Despite existing detection methods, the ability to accurately identify and mitigate ransomware threats remains a pressing concern. This research addresses this difficulty by developing a dynamic ransomware identification architecture that leverages machine learning and dynamic analysis. Building upon the findings of, this study seeks to improve existing approaches by extracting and analyzing dynamic features from ransomware samples. In developing a dynamic ransomware detection framework, we will use threat intelligence to find features according to the stages of the ransomware. We will sincerely select features by measuring their effectiveness and selecting the best optimal features. Then, we will classify ransomware into goodware, locker ransomware, and encryptor ransomware using these features. We will go for ransomware classification using Ensemble Learning and threat intelligence.

4. Materials and Methods

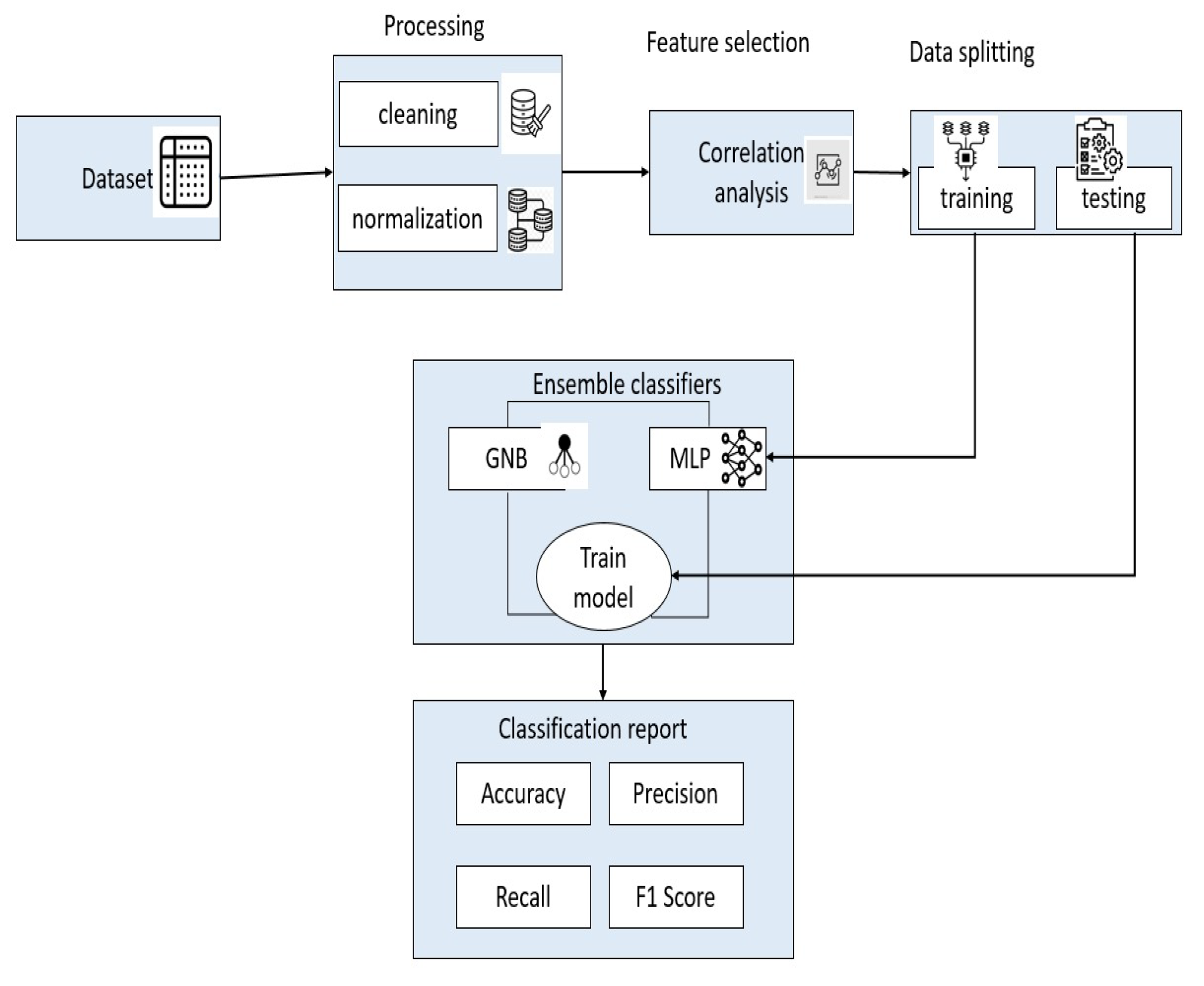

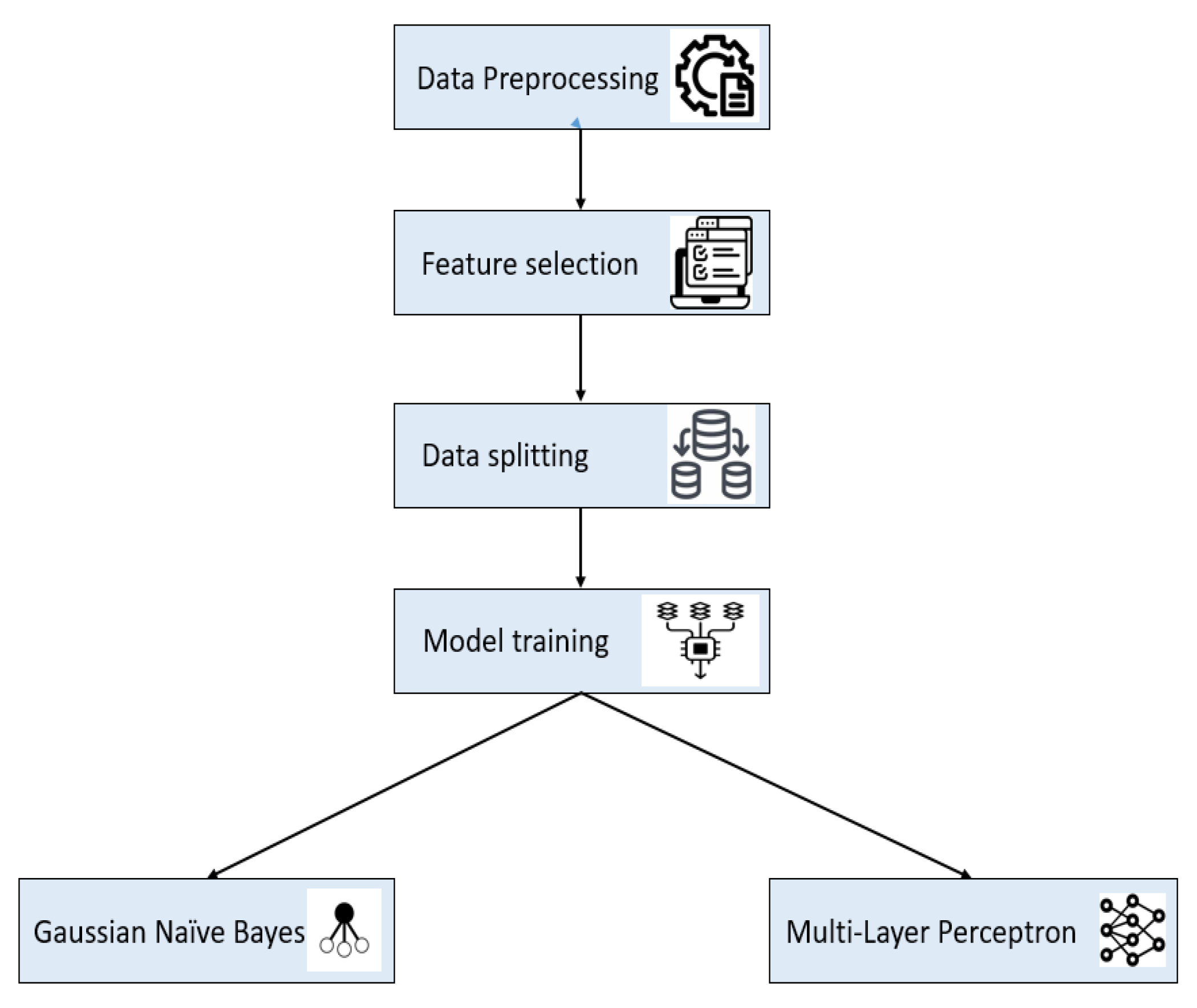

This section describes the methodological approach used to analyze and compare the performance of different machine learning models for dynamic ransomware detection, including standard classification and ensemble methods. The goal was to determine how various strategies improved essential performance indicators like accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, computational efficiency, and memory utilization. This study uses a machine learning strategy to categorize data, combining Gaussian Naive Bayes (GNB) and Multi-layer Perceptron (MLP) models. The procedure depicted in the

Figure 3 begins with the dataset step, where raw data is provided for further analysis. Key preparatory steps, such as cleaning (to remove redundant or inconsistent data) and normalization (to ensure consistency across features), are applied during the processing stage. The processed data is then subjected to feature selection, specifically correlation analysis, to identify the most relevant features for ransomware detection.

Once the features are selected, the data is split into training and testing sets for model development and evaluation. During the training phase, an ensemble classifier is created by combining Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) and Gaussian Naive Bayes (GNB). These classifiers are trained together on the selected features to enhance the model’s accuracy and resilience.

The testing dataset is used to evaluate the trained model, and the results are compiled into a classification report. Key performance metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score, are calculated to assess the effectiveness of the proposed ransomware detection and classification system. This systematic approach ensures robust model performance and thorough analysis.

4.1. Data Processing

The first step is to clean and normalize the data to ensure its high quality and consistency. The following operations are performed: Cleaning: Missing or inconsistent data entries are handled by imputation or elimination. Normalization: The feature values are scaled to ensure that no one feature has a disproportionate influence on the models, enhancing the MLP’s convergence speed and overall classifier performance.

4.2. Leveraging Threat Intelligence for Feature Extraction

To find and pick pertinent aspects from the dataset, we have used threat intelligence (TI). We identified key indicators of compromise (IOC) and ransomware-related behavior patterns by examining the TI data. These characteristics—including ransom note forms, file hashes, encryption techniques, and malicious IP addresses—were chosen because they are pertinent to identifying and categorizing ransomware. To refine our feature set and ensure the attributes we chose appropriately reflect the traits of ransomware assaults, TI also assisted us in spotting patterns in network traffic and system changes.

4.3. Feature Selection

Correlation analysis is used to evaluate the correlations between traits to identify and eliminate redundant or superfluous ones. The SelectKBest approach uses the chi-square statistical test to select the top k characteristics based on their relevance to the target variable. In this study, k is initially set at 40. All features are considered in the following steps. We have removed 10 features using the Chi-Square (Chi2) test, guided by correlation analysis, to keep only the most relevant and important features for ransomware categorization. We lowered the dataset’s dimensionality by removing strongly correlated and duplicated features, which immediately reduces computational complexity. This targeted feature reduction guarantees that the model only focuses on informative information, increasing efficiency while maintaining accuracy. The Chi-Square (Chi2) test and correlation analysis has not compromised the security or effectiveness of the ransomware classification system. By carefully selecting the most relevant and informative features, we ensured that the critical patterns and characteristics necessary for accurate classification were preserved. The eliminated features were redundant or less significant, contributing little to the overall model performance.

4.4. Data Splitting

The preprocessed and selected characteristics are divided into training and testing sets on an 80-20 basis. The training set is used for model fitting and the testing set is used to assess the model’s generalization performance. This strategy reduces overfitting and ensures a fair assessment of the accuracy of the model, as shown in

Figure 4.

4.5. Dataset Overview

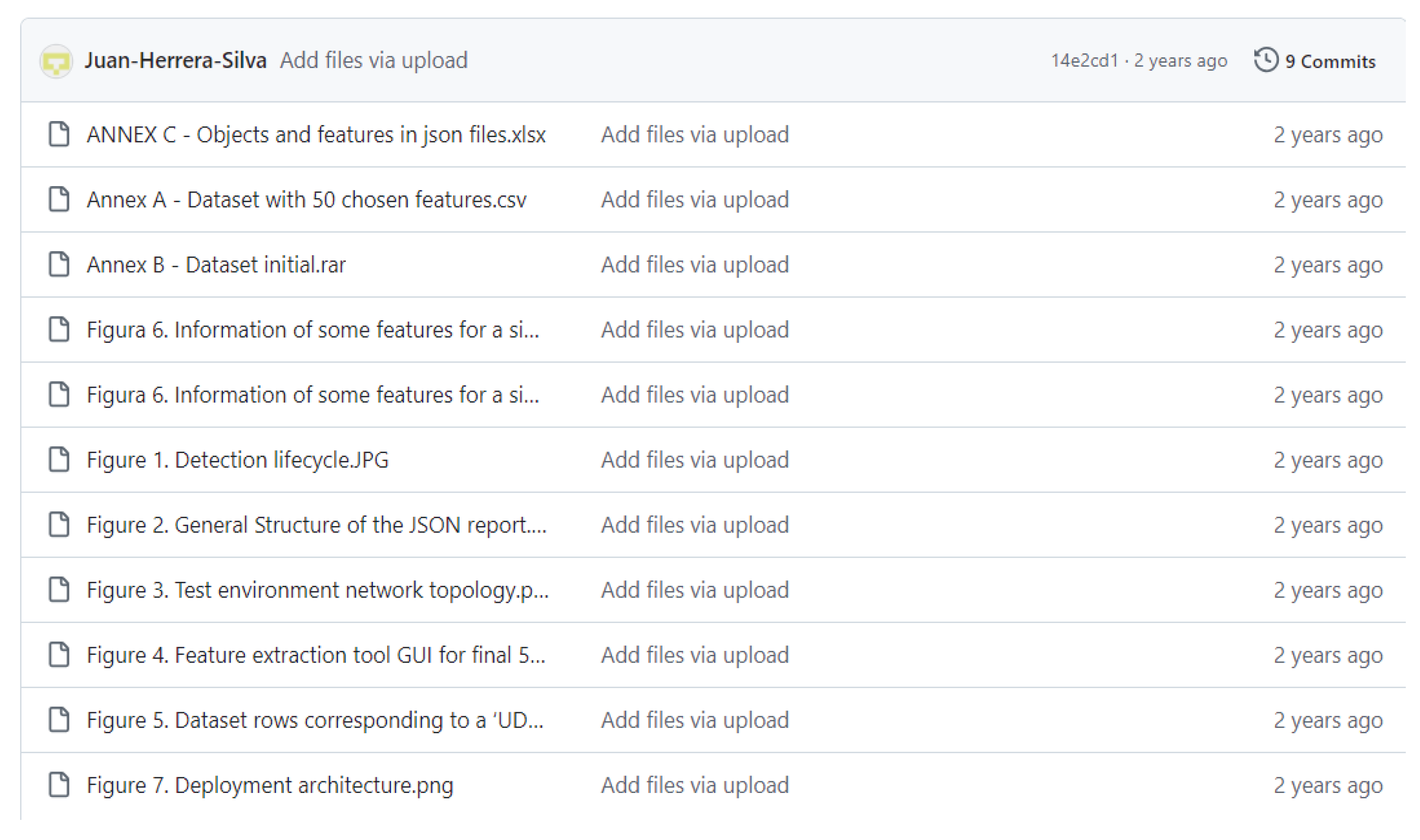

The dataset [

61] consists of 2000 records and 50 attributes; it contains experiments for 20 ransomware and 20 goodware samples. This dataset has three labels: encryptor ransomware, encryptor locker, and goodware. The "Paper-SENSORS" repository as presented in

Figure 5 contains data and tools for network security analysis and malware detection. The main components are Datasets "Annex A" and "Annex B," which contain structured data likely to include network-related metrics or extracted features from network traffic or system behavior monitoring. Annexe A consists of a CSV with 50 selected features. Figures & Diagrams: Illustrations demonstrate the detection lifecycle, network topology structure, and test environment layout, showing a step-by-step approach to network event monitoring and analysis. Feature Extraction and JSON Reports: Tools are provided to extract useful features from raw data and documents describing objects and features in JSON format. This implies preparatory processes in which data from various sources (such as system logs or network packets) is filtered and converted into a format appropriate for machine learning or statistical analysis. Detection Lifecycle and Analysis Workflows: The figures on detection lifecycle and feature extraction workflows focus on identifying and mitigating threats by analyzing features extracted from network or system behaviors, most likely using supervised or unsupervised learning techniques. Overall, this dataset offers a study on security monitoring, feature extraction for anomaly detection, and maybe automated threat classification using the datasets provided.

4.6. Model Training

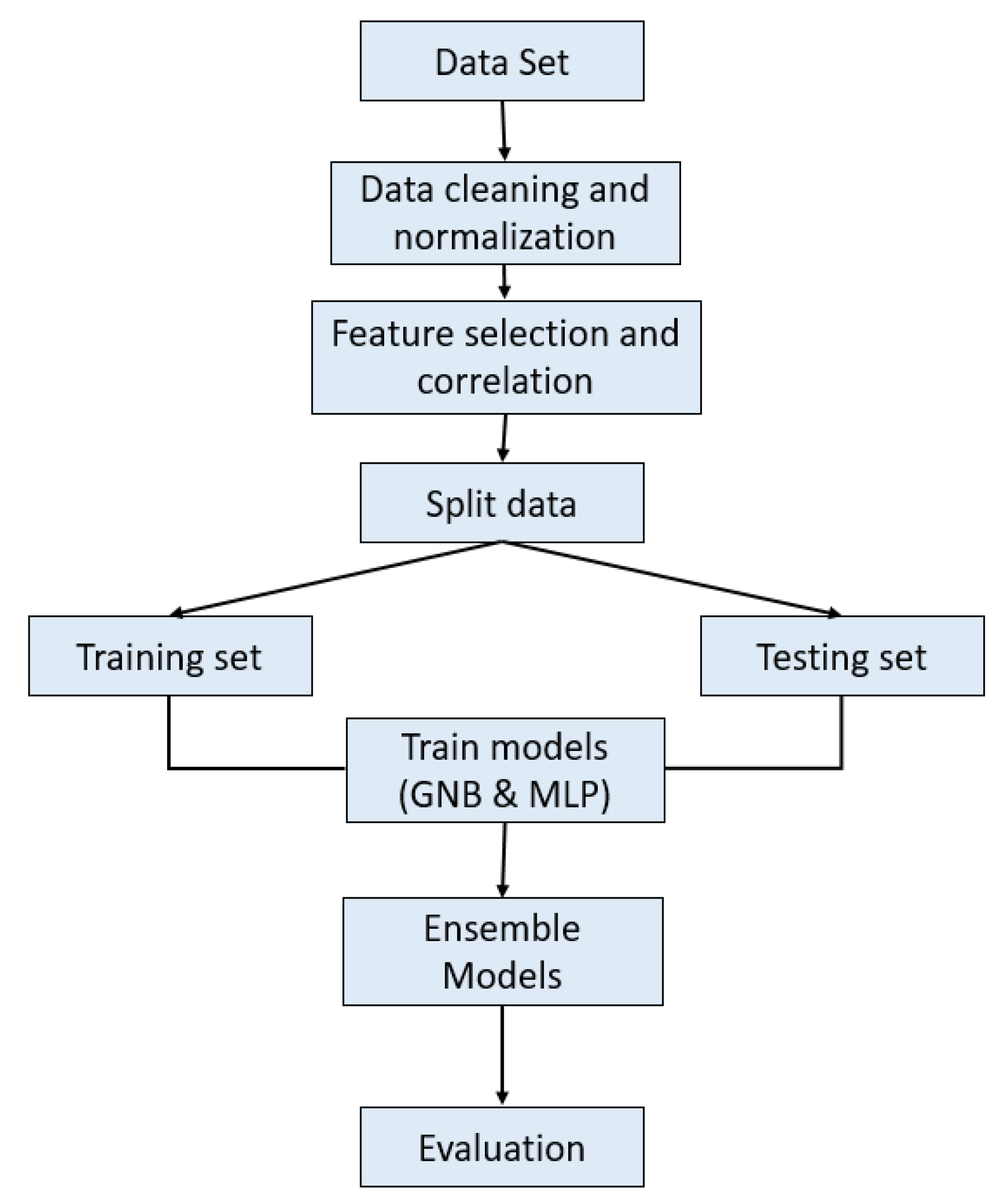

The method shown in the

Figure 6 focuses on employing Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) and Gaussian Naïve Bayes (GNB) for ransomware detection. Data preparation is the first step in ensuring the dataset is standardized and clean. Relevant properties are then found through feature selection, boosting the effectiveness of the models. The data is divided into training and Testing sets for model evaluation. GNB and MLP are used as ensemble classifiers during model training. Whereas MLP uses deep learning methods, GNB uses probabilistic reasoning for categorization. Combined, these models offer a strong and complementary method for detecting ransomware.

4.6.1. Standalone Models

The first stage involved comparing Gaussian Naive Bayes and Multi-layer Perceptron models

Gaussian Naive Bayes: This had an accuracy of 72.50%, a precision of 74.24%, and an F1 score of 71.62%. Although the accuracy was reduced, the F1 score, recall and precision, computational time, and memory use were low, implying that the model was efficient but lacked the needed prediction performance. In contrast, the Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) earned 95.25% accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 scores. While the computational cost was higher, with a CPU time of 10.82 seconds and memory consumption of 1.11 MB, the model yielded much better results than Gaussian Naive Bayes.

4.6.2. Ensemble Model

To investigate how ensemble approaches could increase performance. A voting classifier, stacking classifier, and bagging classifier were used to classify ransomware.

Voting Classifier: The combined models had an accuracy of 99.00%, with precision, recall, and F1 scores all at 99.00%. This model demonstrated a decent blend of prediction performance and computational economy, with an elapsed time of 4.32 seconds.

Stacking Classifier: This achieved 99.25% accuracy, with somewhat higher precision and recall than the Voting Classifier. However, the computational cost rose dramatically, with CPU utilization reaching 38.54 seconds.

Bagging Classifier: This model performed flawlessly, with an accuracy of 99.32%, precision of 99.4%, and an F1 score of 99.4%. However, it had the largest computational cost, with 58.89 seconds of CPU time and 2.71 MB of memory consumption.

5. Results

This section presents a plethora of machine learning classifiers that detect ransomware based on relevant feature selection, ensemble learning, and stringent evaluation measures. The classifiers are Gaussian Naive Bayes (GNB), Multi-layer Perceptron (MLP), Voting, Stacking, and Bagging. The goal means that each must be evaluated regarding its predictive performance and computational properties, including CPU usage, memory footprint, and processing time. The code presents a precise analysis of how these models work differently. It also tests and measures parameters like accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, K fold validation, maximum memory usage, and time.

A confusion matrix is a table used to evaluate the performance of a classification model. It shows the counts of true positives (correctly predicted positives), true negatives (correctly predicted negatives), false positives (incorrectly predicted positives), and false negatives (incorrectly predicted negatives). This matrix provides insights into the model’s accuracy, precision, recall, and overall prediction effectiveness. X-Axis of confusion matrix shows predicted class and Y-Axis shows actual class.

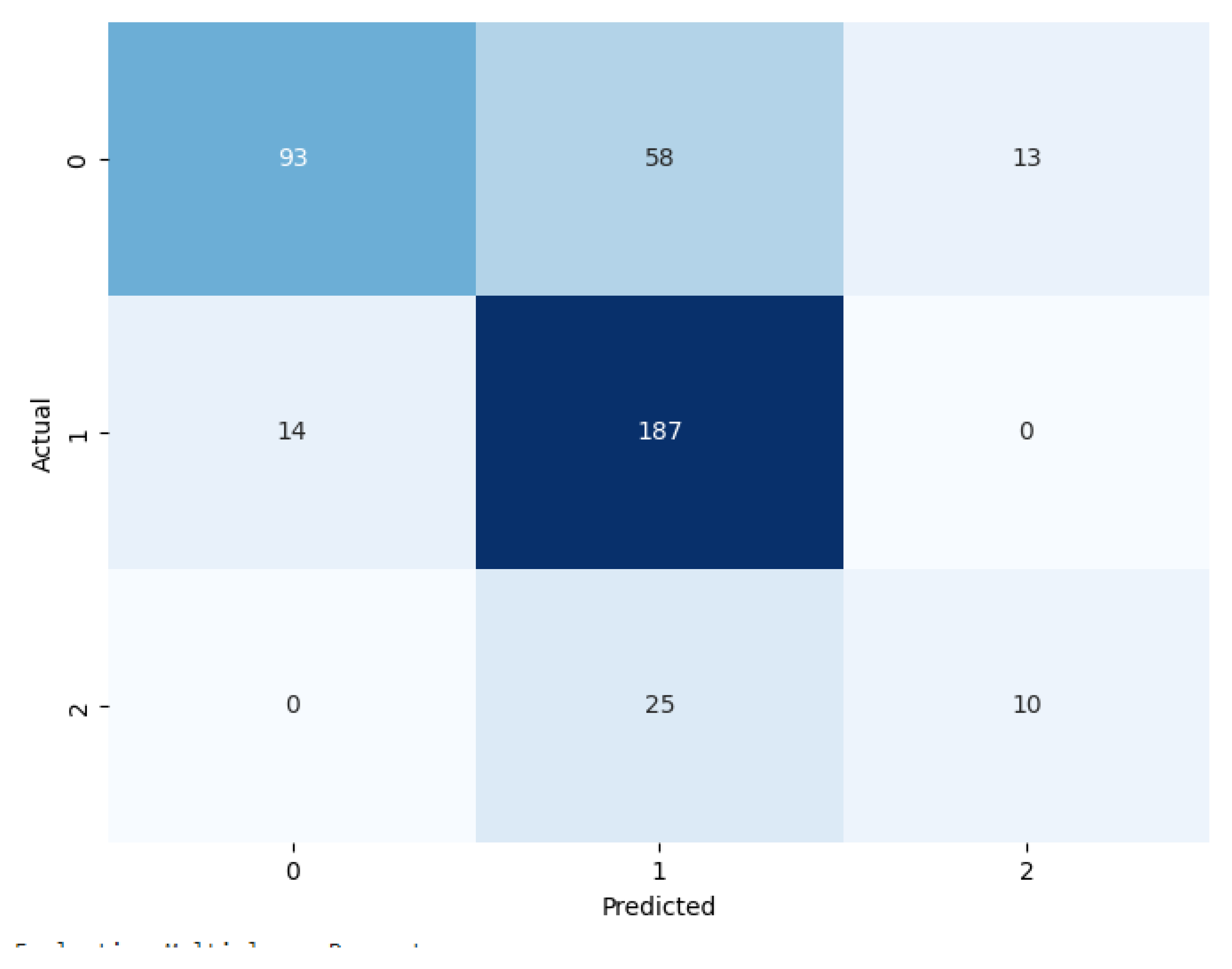

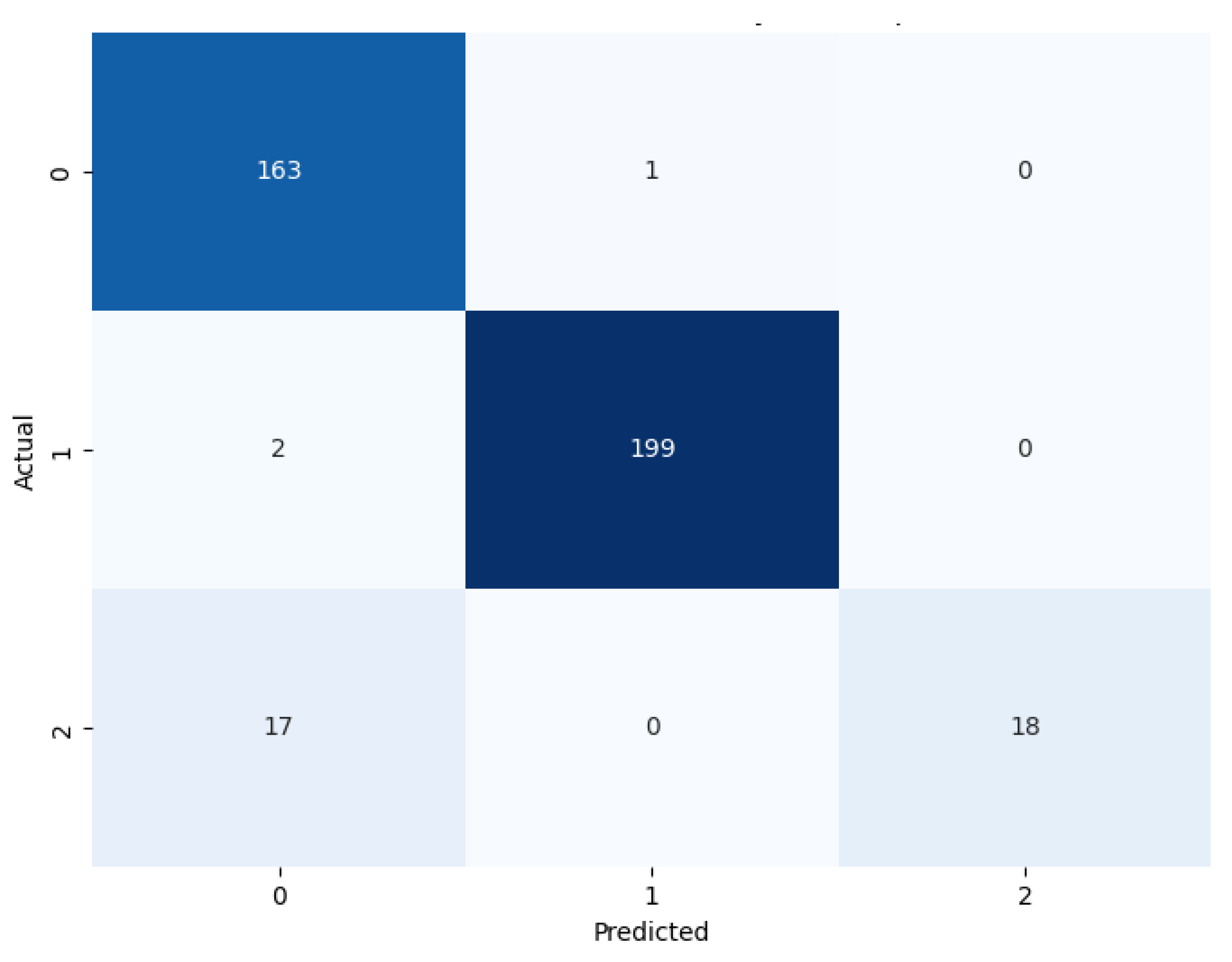

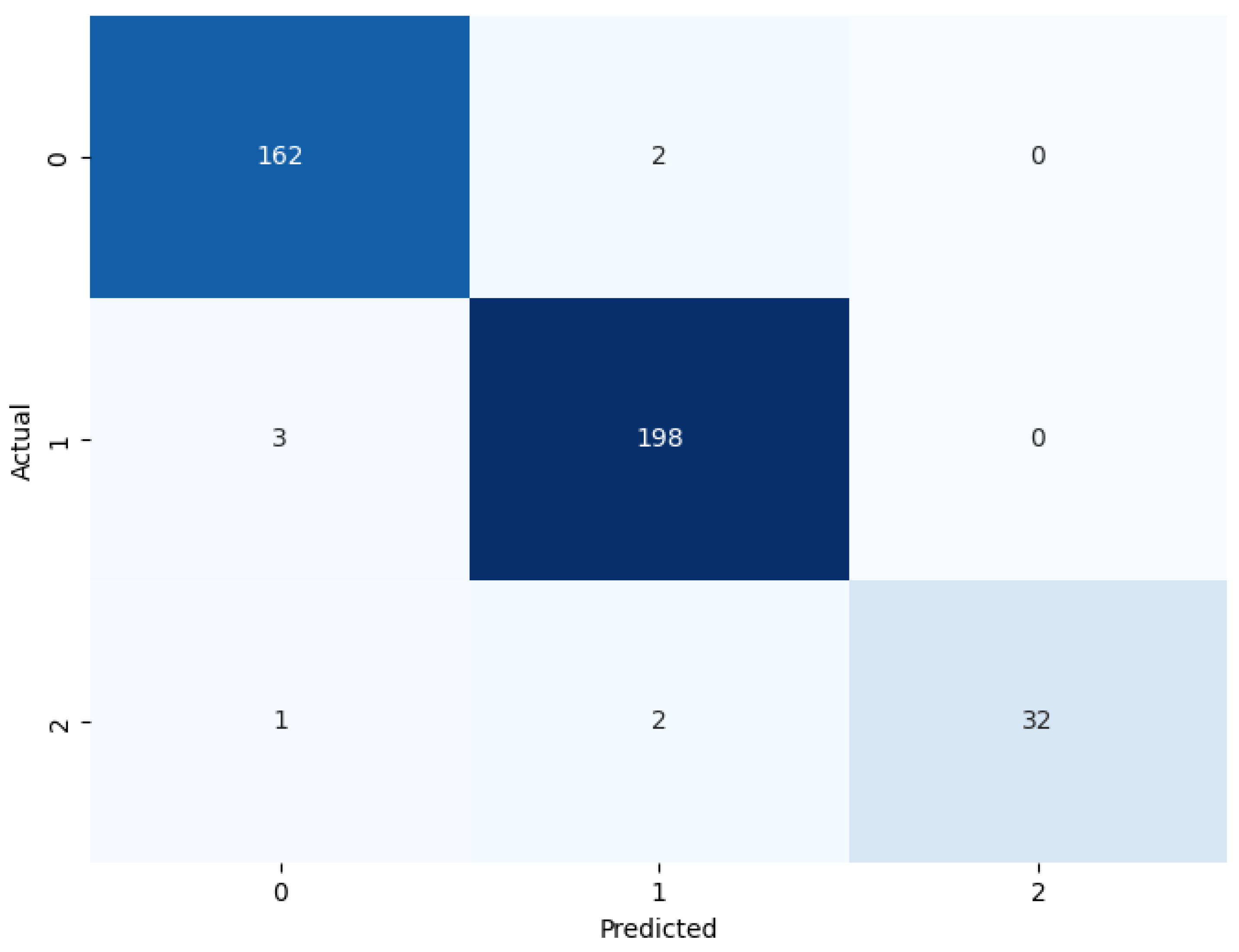

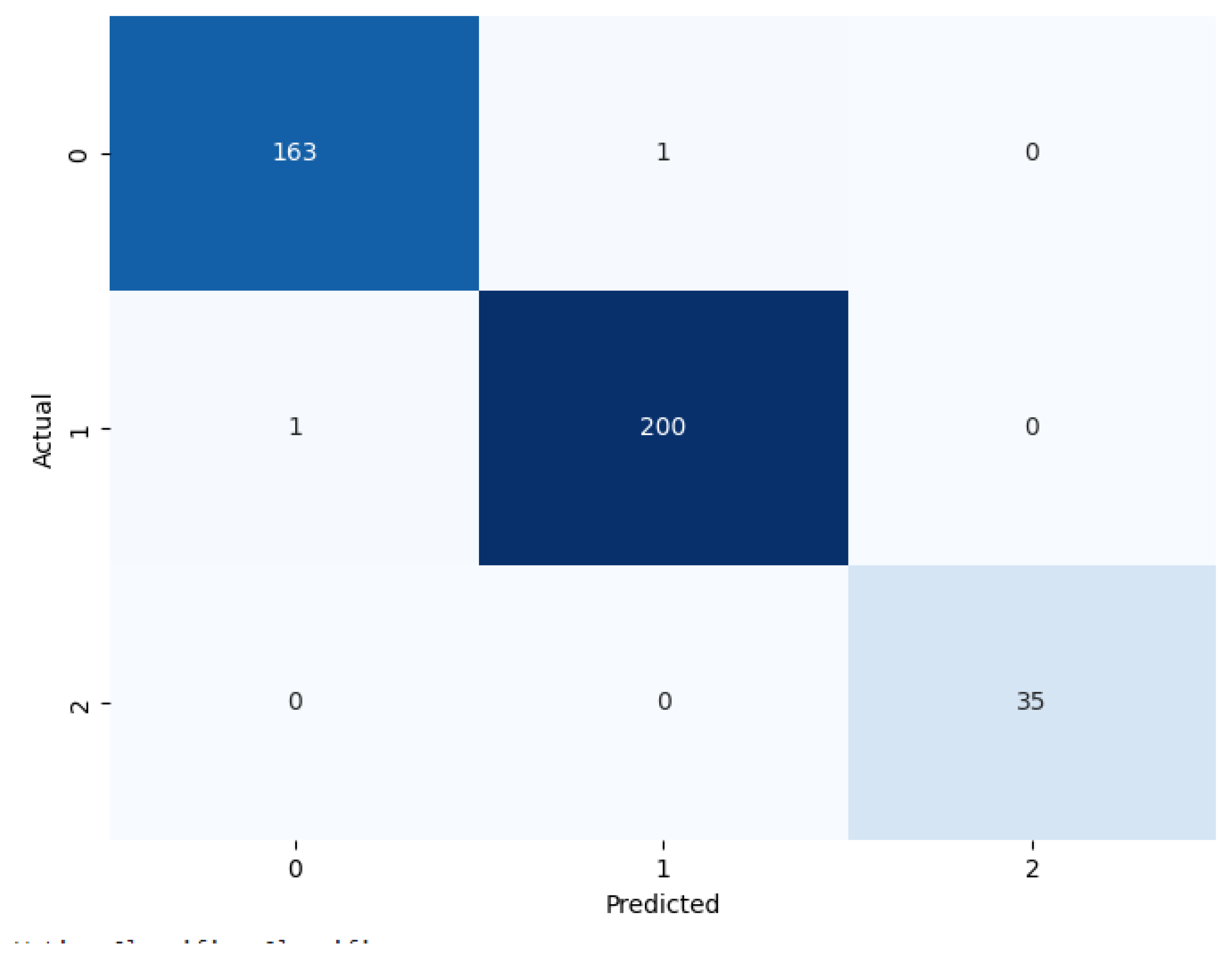

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 shows the confusion matrix for MLP and GNB. As we can see MLP performs very well in classification of ransomwares as compared to GNB which has performed many wrong predictions.

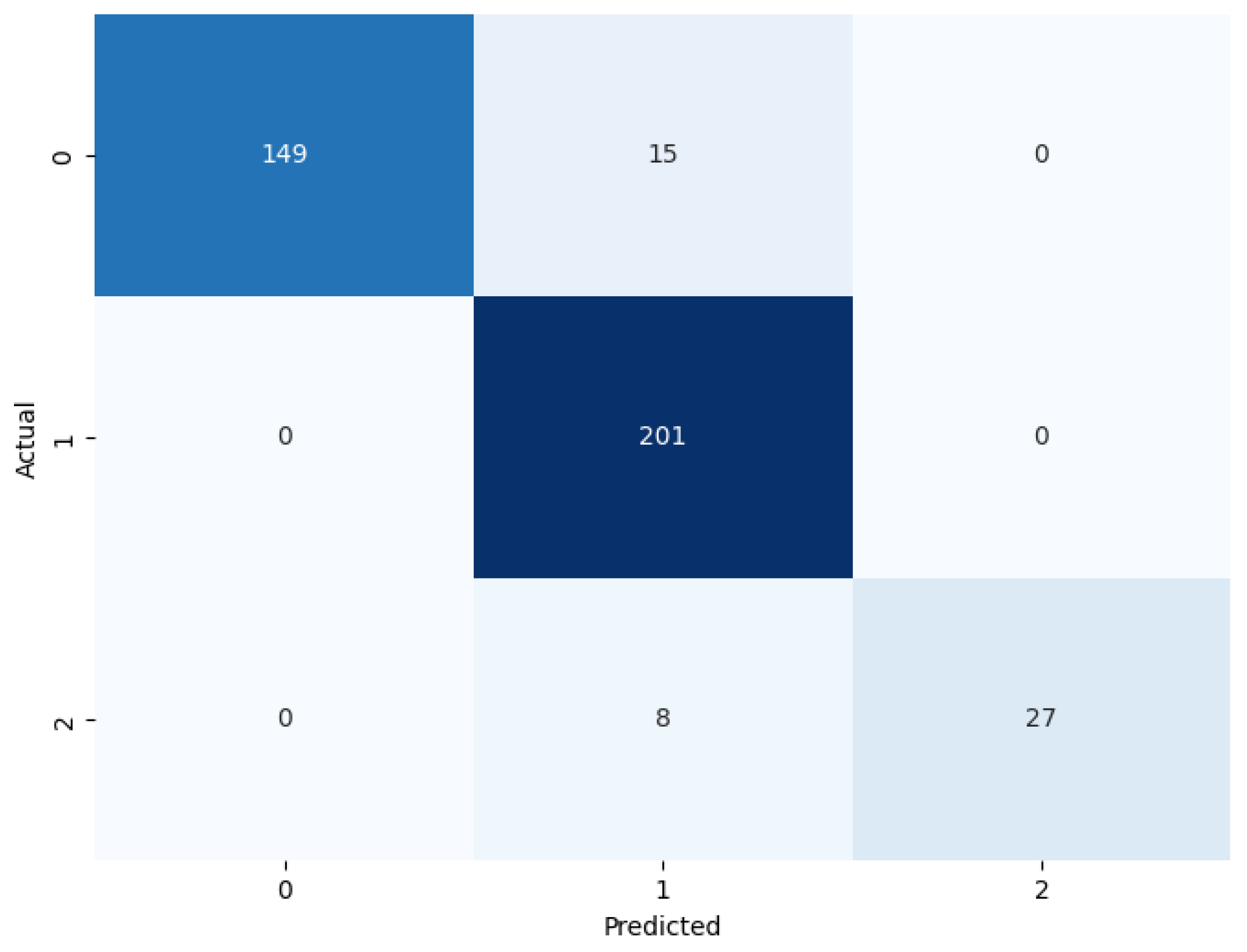

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 shows confusion matrices for Voting, Stacking and Bagging classifiers, we can see that Bagging performs best in classification.

5.1. Standalone Models

A single machine learning algorithm is used for prediction or classification.

5.1.1. Gaussian Naive Bayes

The classifier is most advantageous due to its computational performance. The quality of the test turned at 72.5%, positioning it lower than more complex schemes but still relevant where model simplicity and speed are crucial is shown. The confusion matrix in

Figure 7 shows the GNB incorrectly classifying class 0 as class 1 for 58 times as class 2 13 times, class 1 as class 0 14 times, and incorrectly classifying class 2 as class 1 for 25 times.

5.1.2. Multi-Layer Perceptron

The accuracy of 95.0% implies that the model is working well generally, correctly categorizing the vast majority of occurrences. Resource consumption is higher than GNB but less than ensemble classifiers. The confusion matrix in

Figure 8 shows the MLP incorrectly classifying class 0 as class 1 for 1 time, class 1 as class 0 2 times, and incorrectly classifying class 2 as class 0 for 17 times.

Figure 7.

Confusion Matrix of GNB.

Figure 7.

Confusion Matrix of GNB.

Figure 8.

Confusion Matrix of MLP.

Figure 8.

Confusion Matrix of MLP.

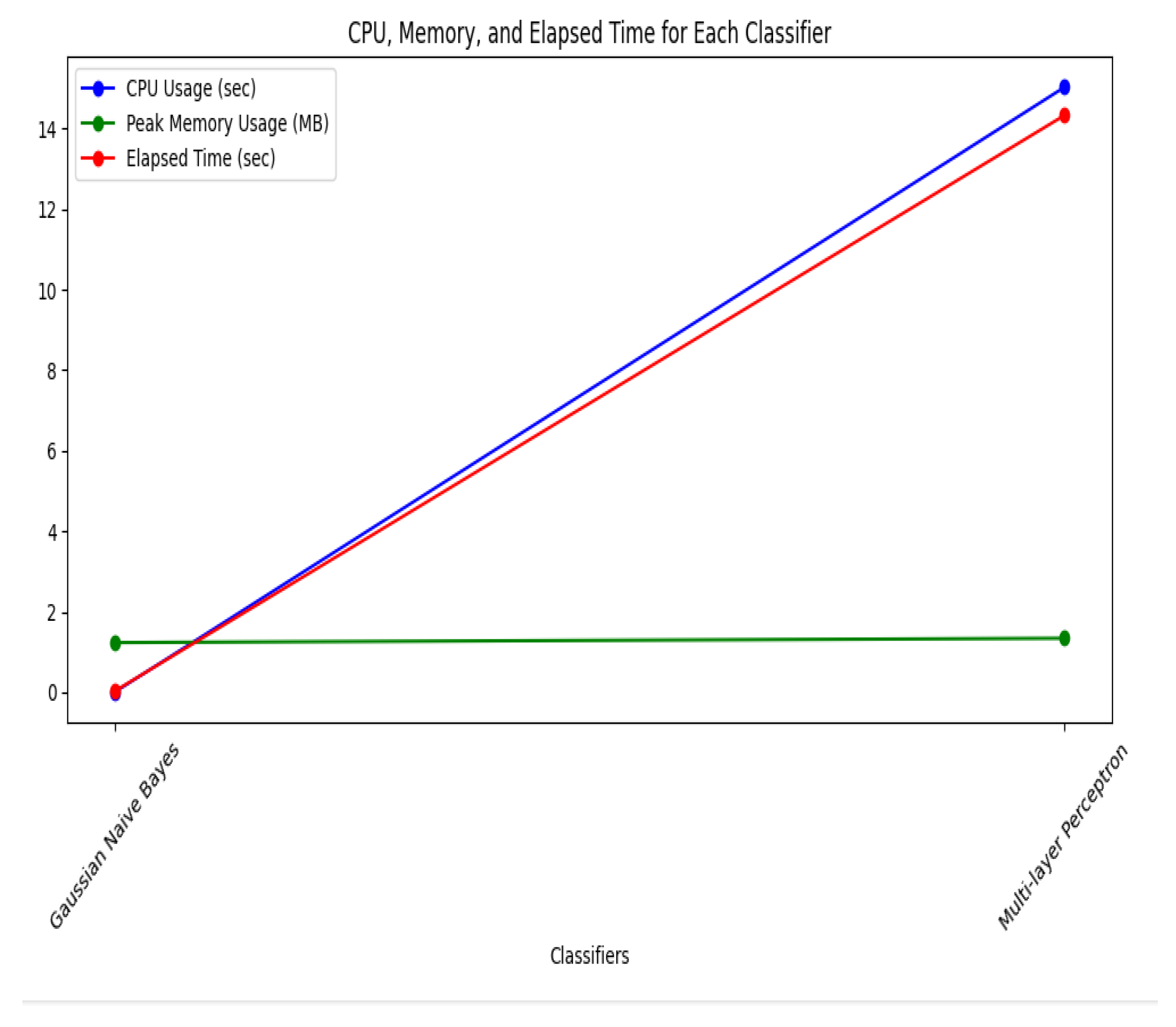

5.1.3. Resource Consumption of Standalone Models

The

Figure 9 contrasts the Gaussian Naive Bayes (GNB) and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) classifiers’ CPU utilization, peak memory usage, and elapsed time. X-Axis shows classifiers and Y-Axis shows Number of MBs and Seconds.

CPU Usage (blue line): MLP uses backpropagation in neural networks and performs intricate calculations, so it uses much more CPU time than GNB. The green line represents thepeak memory usage, which is consistent for both classifiers. This suggests that memory needs are steady and stay mostly the same.Elapsed time (red line): MLP processes data far more slowly than GNB due to its greater computational complexity. While MLP offers more computationally complex analysis, GNB is generally more efficient regarding time and CPU utilization.

Figure 9.

Resource Consumption of Standalone Models.

Figure 9.

Resource Consumption of Standalone Models.

5.2. Ensemble Classifiers

Combines multiple models to improve overall performance.

5.2.1. Voting Classifier

The Voting Classifier is accurate across all classes, considerably reducing the number of misclassifications. This performance demonstrates its ability to use the capabilities of several models to increase forecast reliability. It has a better accuracy of 97.90% , more than standalone models. The confusion matrix in

Figure 10 shows the voting classifier incorrectly classifying class 0 as class 1 for 15 times, correctly classifying class 1 all the time, and incorrectly classifying class 2 as class 1 for 8 times.

5.2.2. Staking Classifier

The Stacking Classifier gives class accuracy of around 98.70%; it performs admirably in all classes. It uses a meta-learner to blend the outputs of the base learners and is, therefore, capable of identifying other interactions in the data. It likely provides higher overall classification accuracy than the Voting Classifier. The confusion matrix in

Figure 11 shows the stacking classifier incorrectly classifying class 0 as class 1 for 2 times, classifying class 1 as class 0 for 3 times, and incorrectly classifying class 2 as class 1 for 2 times, and class 2 as class 0 for 1 time.

Figure 10.

Confusion Matrix of Voting.

Figure 10.

Confusion Matrix of Voting.

Figure 11.

Confusion Matrix of Stacking.

Figure 11.

Confusion Matrix of Stacking.

Figure 12.

Confusion Matrix of Bagging.

Figure 12.

Confusion Matrix of Bagging.

5.2.3. Bagging Classifier

The Bagging Classifier gives the highest accuracy of 99.25%, so it can be concluded that the model possesses excellent characteristics in categorizing instances accurately and with negligible errors. This level of performance is very beneficial for applications where high accuracy is needed, for example, to detect ransomware or to distinguish between various types of malware. Bagging classifiers are resource-intensive compared to other classifiers as they involve multiple models trained on different subsets. The confusion matrix in

Figure 12 shows the bagging classifier incorrectly classifying class 0 as class 1 for 1 time, classifying class 1 as class 0 for 1 time.

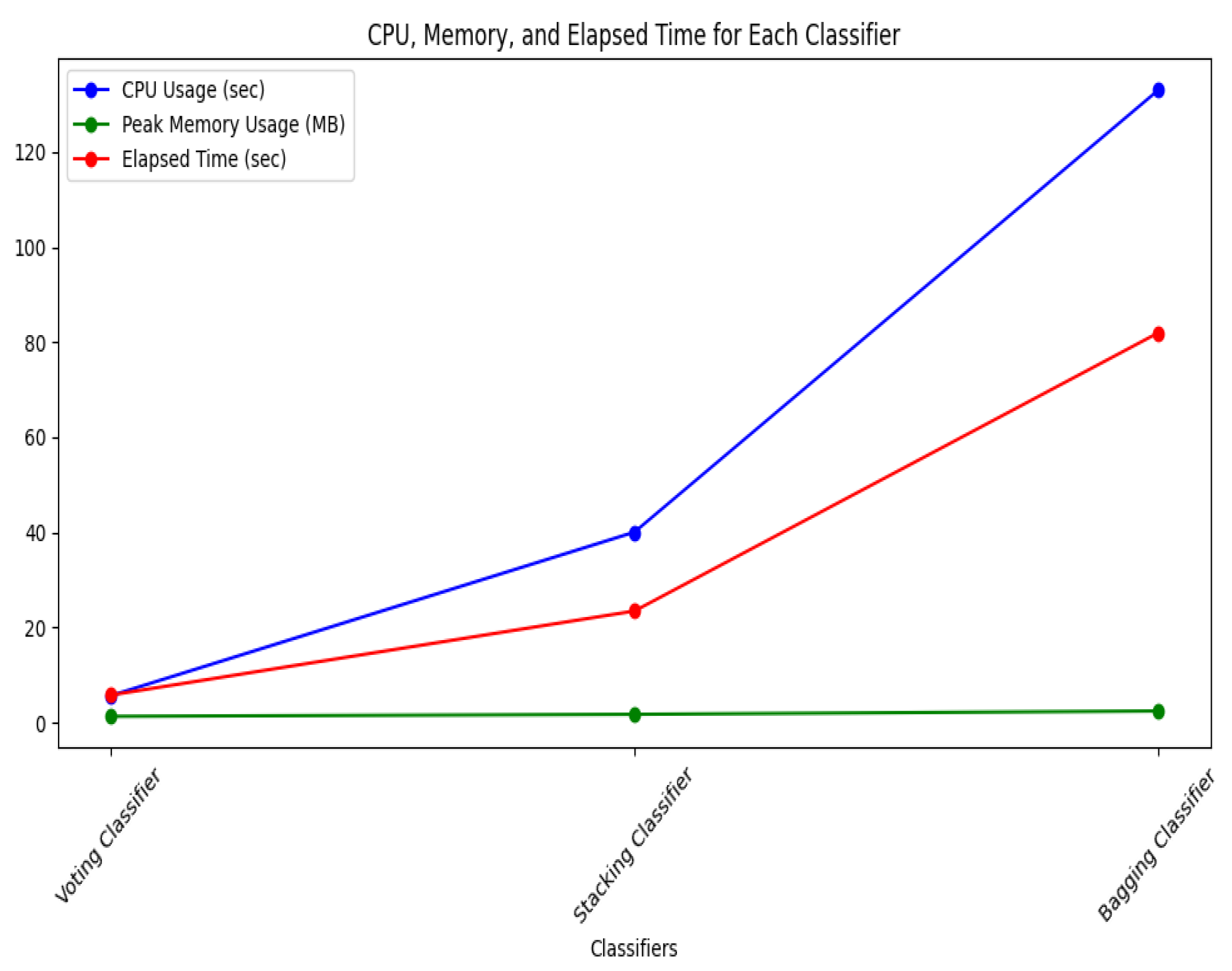

5.2.4. Resource Consumption of Ensemble Classifiers

Figure 13 contrasts the Voting, Stacking, and Bagging CPU utilization, peak memory usage, and elapsed time.

CPU Usage (blue line): Among the ensemble methods, bagging performs more intricate computations, leading to higher CPU usage than voting and stacking. Voting, being the most straightforward approach, uses the least CPU resources.Peak Memory Usage (green line):The peak memory usage is relatively consistent across voting, stacking, and bagging, indicating that memory requirements remain steady regardless of the method. Elapsed Time (red line): bagging takes the longest to process data due to its layered model training and blending, while voting is the fastest. Stacking falls in between, as it trains multiple models independently but requires aggregation.

While bagging provides the most sophisticated analysis, voting is the most efficient regarding time and CPU usage, with stacking offering a middle ground.

Figure 13.

Resource Consumption of Ensembling Classifiers.

Figure 13.

Resource Consumption of Ensembling Classifiers.

6. Discussion

Our study presents machine learning classifiers that detect ransomware based on relevant feature selection, ensemble learning, and stringent evaluation measures. The classifiers are GNB, MLP, Voting, Stacking, and Bagging. The goal means that each must be evaluated regarding its predictive performance and computational properties, including CPU usage, memory footprint, and processing time. The code presents a precise analysis of how these models work differently. It also tests and measures parameters like accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, K fold validation, maximum memory usage, and time.

The dataset is prepared, features are selected using SelectKBest, and chi2 is applied to select features. Feature selection is an essential process in machine learning, especially for high-dimensional data such as ransomware detection, as it removes irrelevant features, decreasing model complexity, longer computation times, and leads to better generation. Downsizing helps to eliminate insignificant features, meaning only the most significant features that are most prognostically influential are included, and it reduces noise. The selected features are used to build and test the classifiers. For this purpose, the dataset is split into training and testing datasets to reflect a comprehensive assessment of the accuracy of the classifiers. The ransomware family’s target variable is label encoded to allow machine learning algorithms to analyze them. Consequently, presenting the results of the models, a relative comparison of the performances of Gaussian Naive Bayes (GNB), Voting Classifier, Ensemble Stacking Classifier, Bagging Classifier, and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP). We have used 40 features for making detection over dynamic feature datasets. The GNB model has an accuracy of 72.95%, a Precision of 74.24%, an F1 score of 71.06%, and Weights. This entails only 0.02 secs CPU usage and 0.69MB RAM. GNB is fast and thus suitable for areas with limited resources, but it needs to be more accurate in decision-making; it also misinterprets different types of ransomware. The Bagging Classifier has the best result of 99.25% for accuracy, 99.09% for precision, and 99.00% F1 score. But it takes a lot of CPU time, 121.61 seconds, and memory 2.56 MB. This approach is pretty good for detecting ransomware; that’s why it is suitable for conditions when high accuracy is needed and the amount of resources is unlimited.

In this work, we have optimized ransomware classification by reducing the set of features using the Chi-square function (Chi2), which allowed us to retain the most relevant features while eliminating redundant or less significant ones. This feature reduction improved the model’s accuracy and significantly reduced computational resource consumption, enabling faster and more efficient training and inference. To further enhance performance, we employ ensemble techniques such as Voting Classifiers that combine the strengths of multiple models to achieve robust and reliable classification results. This integrated approach has led to a more accurate and resource-efficient ransomware detection framework, demonstrating the effectiveness of feature selection and ensemble learning in handling complex cybersecurity challenges.

If we compare three ensemble classifiers, voting performs best in cases with limited resources. In contrast, bagging performs best in cases where unlimited resources and high accuracy are required. The Voting Classifier is very good at balancing its performance and resource usage, and the MLP is particularly good at complicated data processing. Shown in

Table 2.

In paper [

32], they have also used GNB and Neural Networks; they have worked on 50 features, explored their techniques, and gave our solution for improvement. We first tried to improve performance parameters like precision, recall, and F1-score, and secondly, we introduced ensembling in this scenario; as shown in

Table 3, we can see that we have achieved quite good results as compared to prior methods, we have faced a decline in accuracy, but other parameters are pretty good. Our proposed solution "RanDEL" is quite efficient as we can see a massive decline in processing time. Comparison shown in

Table 3.

A voting classifier is our proposed model, as it has proven to be quite effective with little processing time. Stacking, bagging, and voting all have comparable accuracy, but the Voting Classifier is superior because it is easier to use and runs more quickly, which makes it better suited for real-world ransomware classification. The

Table 4 below summarizes how our suggested model compares to earlier methods and demonstrates how well it balances accuracy and computing efficiency:

The reduction in processing time in our proposed model is due to two important factors: feature reduction and model tweaking and pruning. Using the Chi-Square (Chi2) function for feature selection, we removed irrelevant and redundant features, significantly reducing the dimensionality of the input data. This not only reduces computational complexity but also enables models to process fewer features, resulting in faster training and prediction times.

Additionally, through model tuning and pruning, we have optimized the hyperparameters and removed unnecessary components or layers in the models. This fine-tuning ensures that the models run efficiently, without overfitting or computational overhead. By streamlining both the input features and model architecture, we achieve a significant reduction in processing time while maintaining high accuracy. The proposed Voting Classifier is an efficient and resource-conserving approach to ransomware classification.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

Increased ransomware threats require a highly effective and evolving detection structure to fend off more elaborate destructive viruses. This study aims to solve ransomware’s urgent challenges on aspects of machine learning and dynamic analysis to formulate a robust ransomware detection technique. Specific research objectives were identifying ransomware features from threat data, classifying families, evaluating the features, and enhancing ensemble learning architectures. Our work indicates that threat intelligence strengthens the process of identifying dynamic elements at each ransomware stage and improves the categorization of ransomware types, including goodware, locker ransomware, and encryptor ransomware. This paper also likes how different ensemble learning strategies surpass standalone approaches to ML in expanding the limitations of conventional detection techniques for better classification efficiency and finding new kinds of ransomware. In evaluating and improving the chosen features, we highlighted the importance of feature effectiveness when implementing ransomware detection systems. A comparison of performance between the solo and ensemble models reveals that the ensemble models improve classification outcomes and minimize the risks associated with false negatives, which are crucial in ransomware cases. From the perspective of this study, the enhancement of knowledge in the field of cybersecurity can be considered, as this paper contributes a comprehensive approach to ransomware detection, which involves both dynamic analysis and machine learning. The proposed framework enhances the ability to classify ransomware. It simultaneously serves as a base for future security applications dealing with the constantly evolving threat landscape.

Our objective for future research is to create sophisticated techniques for identifying ransomware activity at the network level before it infects and spreads to individual computers. We will concentrate on detecting dangerous patterns and behaviors in network traffic to develop a proactive defense system that stops ransomware from accessing endpoints. By tackling attacks early on, this strategy will improve overall cybersecurity and lower the chance of data encryption or system breaches.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A. and Z.I.; methodology, M.A.;Writing—original draft preparation, M.A.; supervision, Z.I.; validation, A.I. and Z.M.; writing—review and editing, M.A. and Z.I.; visualization, M.A.; project administration, A.I.;. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| DNS |

Domain Name Server |

| DT |

Decision Tree |

| DWOML-RWD |

Dwarf mongoose optimization with machine-learning-driven ransomware detection |

| GBDT |

Gradient Boosting Decision Tree |

| GNB |

Gaussian Naive Bayes |

| HTTP |

Hypertext Transfer Protocol |

| HTTPS |

Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure |

| KNN |

K-Nearest Neighbors |

| LSTM |

Long Short Term Memory |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| MLP |

Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| NB |

Naive Bayes |

| RF |

Random Forest |

| SMO |

Sequential Minimal Optimization |

| SVM |

Support Vector Machine |

| TCP |

Transmission Control Protocol |

| TI |

Threat Intelligence |

| TIG |

Tree-Based Information Gain |

| TLS |

Transport Layer Security |

References

- Alraizza, A.; Algarni, A. Ransomware detection using machine learning: A survey. Big Data and Cognitive Computing 2023, 7, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J. Understanding Machine Learning. Journal of AI Research 2020, 45, 123–145. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb, S. Ransomware vs printing press? US newspapers face "foreign cyberattack". We Live Security 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Trend Micro. Report: Huge increase in ransomware attacks on businesses. Trend Micro 2019.

- Faghihi, F.; Zulkernine, M. RansomCare: Data-centric detection and mitigation against smartphone crypto-ransomware. Computer Networks 2021, 191, 108011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Share of organizations worldwide hit by ransomware attacks from 2022 to 2024, by country, 2024. Accessed: 2024-11-25.

- Beaman, C.; Barkworth, A.; Akande, T.D.; Hakak, S.; Khan, M.K. Ransomware: Recent advances, analysis, challenges and future research directions. Computers & security 2021, 111, 102490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayub, M.A.; Siraj, A.; Filar, B.; Gupta, M. RWArmor: a static-informed dynamic analysis approach for early detection of cryptographic windows ransomware. International Journal of Information Security 2024, 23, 533–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, A.; Gupta, A.; Gupta, R.; Tanwar, S.; Sharma, G.; Davidson, I.E. Ransomware detection, avoidance, and mitigation scheme: a review and future directions. Sustainability 2021, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Distribution of detected cyberattacks worldwide in 2023, by type, 2023. Accessed: 2024-11-25.

- Cen, M.; Jiang, F.; Qin, X.; Jiang, Q.; Doss, R. Ransomware early detection: A survey. Computer Networks 2024, 239, 110138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.; McGrew, D. Identifying encrypted malware traffic with contextual flow data. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2016 ACM workshop on artificial intelligence and security; 2016; pp. 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgandurra, D.; Muñoz-González, L.; Mohsen, R.; Lupu, E.C. Automated dynamic analysis of ransomware: Benefits, limitations and use for detection. arXiv preprint 2016, arXiv:1609.03020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urooj, U.; Al-rimy, B.A.S.; Zainal, A.; Ghaleb, F.A.; Rassam, M.A. Ransomware detection using the dynamic analysis and machine learning: A survey and research directions. Applied Sciences 2021, 12, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Silva, J.A.; Hernández-Álvarez, M. Dynamic Feature Dataset for Ransomware Detection Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Journal of Cybersecurity Research 2024, pp. E11–25. These authors contributed equally to this work. [CrossRef]

- Tasnim, N.; Shahriar, K.T.; Alqahtani, H.; Sarker, I.H. Ransomware family classification with ensemble model based on behavior analysis. In Machine Intelligence and Data Science Applications: Proceedings of MIDAS 2021; Springer, 2022; pp. 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahoora, U.; Rajarajan, M.; Pan, Z.; Khan, A. Zero-day ransomware attack detection using deep contractive autoencoder and voting based ensemble classifier. Applied Intelligence 2022, 52, 13941–13960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeez, N.A.; Odufuwa, O.E.; Misra, S.; Oluranti, J.; Damaševičius, R. Windows PE malware detection using ensemble learning. In Proceedings of the Informatics; MDPI, 2021; Vol. 8, p. 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damaševičius, R.; Venčkauskas, A.; Toldinas, J.; Grigaliūnas, Š. Ensemble-based classification using neural networks and machine learning models for windows pe malware detection. Electronics 2021, 10, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.R.; Macfarlane, R.; Buchanan, W.J. Majority voting ransomware detection system. Journal of Information Security 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietterich, T.G. Ensemble methods in machine learning. In Proceedings of the International workshop on multiple classifier systems; Springer, 2000; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SkiKit Learn. Staking Classifier.

- Scikit Learn. Bagging Classifier.

- Barut, O.; Grohotolski, M.; DiLeo, C.; Luo, Y.; Li, P.; Zhang, T. Machine learning based malware detection on encrypted traffic: A comprehensive performance study. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Networking, Systems and Security; 2020; pp. 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Continella, A.; Guagnelli, A.; Zingaro, G.; De Pasquale, G.; Barenghi, A.; Zanero, S.; Maggi, F. Shieldfs: a self-healing, ransomware-aware filesystem. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 32nd annual conference on computer security applications; 2016; pp. 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Gu, H.; Wei, W.; Guo, Y. Deep-Full-Range: a deep learning based network encrypted traffic classification and intrusion detection framework. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 45182–45190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, C.; Ha, J.; Roh, H. A survey on TLS-encrypted malware network traffic analysis applicable to security operations centers. Applied Sciences 2021, 12, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lucia, M.J.; Cotton, C. Detection of encrypted malicious network traffic using machine learning. In Proceedings of the MILCOM 2019-2019 IEEE Military Communications Conference (MILCOM); IEEE, 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.; Roh, H. Experimental evaluation of malware family classification methods from sequential information of tls-encrypted traffic. Electronics 2021, 10, 3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoinianakis, D.; Goetze, N.; Lehmann, G. Mdiet: Malware detection in encrypted traffic. In Proceedings of the 6th International Symposium for ICS & SCADA Cyber Security Research, September 2019; pp. 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.P.; Singh, M. A comparative review of malware analysis and detection in HTTPs traffic. International Journal of Computing and Digital Systems 2021, 10, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Silva, J.A.; Hernández-Álvarez, M. Dynamic feature dataset for ransomware detection using machine learning algorithms. Sensors 2023, 23, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jegede, A.; Fadele, A.; Onoja, M.; Aimufua, G.; Mazadu, I.J. Trends and future directions in automated ransomware detection. Journal of Computing and Social Informatics 2022, 1, 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrew, D.; Anderson, B. Enhanced telemetry for encrypted threat analytics. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 24th international conference on network protocols (ICNP); IEEE, 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhawat, A.S.; Di Troia, F.; Stamp, M. Feature analysis of encrypted malicious traffic. Expert Systems with Applications 2019, 125, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon, P.; Hasegawa, H.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Shimada, H. Malware Detection based on HTTPS Characteristic via Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the ICISSP; 2018; pp. 410–417. [Google Scholar]

- Prasse, P.; Machlica, L.; Pevnỳ, T.; Havelka, J.; Scheffer, T. Malware detection by analysing encrypted network traffic with neural networks. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases: European Conference, ECML PKDD 2017, Skopje, Macedonia, September 18–22, 2017; Proceedings, Part II 10. Springer, 2017; pp. 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Sharma, K.; Wazid, M.; Das, A.K. SINN-RD: Spline interpolation-envisioned neural network-based ransomware detection scheme. Computers and Electrical Engineering 2023, 106, 108601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokoč, J.; Kohout, J.; Čech, P.; Skopal, T.; Pevnỳ, T. k-NN classification of malware in HTTPS traffic using the metric space approach. In Proceedings of the Intelligence and Security Informatics: 11th Pacific Asia Workshop. PAISI 2016, Auckland, New Zealand, April 19, 2016; Proceedings 11. Springer, 2016; pp. 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majd, N.E.; Mazumdar, T. Ransomware classification using machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 32nd International Conference on Computer Communications and Networks (ICCCN); IEEE, 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohout, J.; Komárek, T.; Čech, P.; Bodnár, J.; Lokoč, J. Learning communication patterns for malware discovery in HTTPs data. Expert Systems with Applications 2018, 101, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muehlstein, J.; Zion, Y.; Bahumi, M.; Kirshenboim, I.; Dubin, R.; Dvir, A.; Pele, O. Analyzing HTTPS encrypted traffic to identify user’s operating system, browser and application. In Proceedings of the 2017 14th IEEE Annual Consumer Communications & Networking Conference (CCNC), 2017; IEEE; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Isingizwe, D.F.; Wang, M.; Liu, W.; Wang, D.; Wu, T.; Li, J. Analyzing learning-based encrypted malware traffic classification with automl. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 21st International Conference on Communication Technology (ICCT); IEEE, 2021; pp. 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrueta, E.; Morato, D.; Magaña, E.; Izal, M. Crypto-ransomware detection using machine learning models in file-sharing network scenarios with encrypted traffic. Expert Systems with Applications 2022, 209, 118299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Mushtaq, Z.; Abosaq, H.A.; Mursal, S.N.F.; Irfan, M.; Nowakowski, G. Enhancing ransomware attack detection using transfer learning and deep learning ensemble models on cloud-encrypted data. Electronics 2023, 12, 3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besta, M.; Kanakagiri, R.; Mustafa, H.; Karasikov, M.; Rätsch, G.; Hoefler, T.; Solomonik, E. Communication-efficient jaccard similarity for high-performance distributed genome comparisons. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium (IPDPS); IEEE, 2020; pp. 1122–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfollahi, M.; Jafari Siavoshani, M.; Shirali Hossein Zade, R.; Saberian, M. Deep packet: A novel approach for encrypted traffic classification using deep learning. Soft Computing 2020, 24, 1999–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djenna, A.; Bouridane, A.; Rubab, S.; Marou, I.M. Artificial Intelligence-Based Malware Detection, Analysis, and Mitigation. Symmetry 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shafai, W.; Almomani, I.; AlKhayer, A. Visualized Malware Multi-Classification Framework Using Fine-Tuned CNN-Based Transfer Learning Models. Applied Sciences 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamany, B.; Elsayed, M.S.; Jurcut, A.D.; Abdelbaki, N.; Azer, M.A. A New Scheme for Ransomware Classification and Clustering Using Static Features. Electronics 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urooj, U.; Al-rimy, B.A.S.; Zainal, A.; Ghaleb, F.A.; Rassam, M.A. Ransomware Detection Using the Dynamic Analysis and Machine Learning: A Survey and Research Directions. Applied Sciences 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albshaier, L.; Almarri, S.; Rahman, M.M.H. Earlier Decision on Detection of Ransomware Identification: A Comprehensive Systematic Literature Review. Information 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzan, M.; Sheldon, F.T. Opportunities for Early Detection and Prediction of Ransomware Attacks against Industrial Control Systems. Future Internet 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusack, G.; Michel, O.; Keller, E. Machine learning-based detection of ransomware using SDN. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 ACM international workshop on security in software defined networks & network function virtualization, 2018, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Alhawi, O.M.; Baldwin, J.; Dehghantanha, A. Leveraging machine learning techniques for windows ransomware network traffic detection. Cyber threat intelligence 2018, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xiao, X.; Mercaldo, F.; Ni, S.; Martinelli, F.; Sangaiah, A.K. Classification of ransomware families with machine learning based onN-gram of opcodes. Future Generation Computer Systems 2019, 90, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Rahman, M.M. RansHunt: A support vector machines based ransomware analysis framework with integrated feature set. In Proceedings of the 2017 20th international conference of computer and information technology (ICCIT); IEEE, 2017; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Ncube, C.; Ramasamy, L.K.; Kadry, S.; Nam, Y. A digital DNA sequencing engine for ransomware detection using machine learning. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 119710–119719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Yun, J.; Lee, K. A Study on Countermeasures against Neutralizing Technology: Encoding Algorithm-Based Ransomware Detection Methods Using Machine Learning. Electronics 2024, 13, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Alissa, K.; H. Elkamchouchi, D.; Tarmissi, K.; Yafoz, A.; Alsini, R.; Alghushairy, O.; Mohamed, A.; Al Duhayyim, M. Dwarf Mongoose Optimization with Machine-Learning-Driven Ransomware Detection in Internet of Things Environment. Applied Sciences 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Silva, J. Paper-SENSORS. https://github.com/Juan-Herrera-Silva/Paper-SENSORS, 2024. Accessed: 2024-10-20.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).