1. Introduction

The indoor microclimatic conditions of historical libraries play a pivotal role in ensuring the long-term preservation of valuable collections, while also influencing the comfort and well-being of staff and visitors [

1]. In recent years, there has been a growing emphasis on balancing conservation needs with evolving patterns of use and energy efficiency within cultural heritage buildings [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. In contemporary conservation practice, the regulation of indoor microclimatic parameters within libraries is predominantly managed through the deployment of Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) systems [

3,

7]. These systems are widely recognized as critical for ensuring the environmental stability necessary for the long-term preservation of cultural heritage materials [

8,

9]. Nevertheless, notable exceptions reamin, particularly among historical libraries, where such systems are absent and indoor environmental control depends exclusively on passive mechanisms [

2,

10,

11]. These mechanisms are closely tied to architectural features such as building mass, material properties, spatial orientation, and overall structural design. Prominent examples of libraries operating without HVAC systems include the Biblioteca Malatestiana in Cesena, Italy, and the historical library of the University of Salamanca, Spain [

1,

2]. In these institutions, internal environmental stability is primarily achieved through traditional construction methods that inherently buffer external climatic variations [

2,

12].

Conversely, the retrofitting of HVAC systems into historical libraries often introduces conservation challenges. As these installations occur centuries after the buildings were constructed, they frequently disturb the pre-existing equilibrium, producing abrupt variations in temperature and relative humidity [

13]. These fluctuations may accelerate the degradation of both the buildings and their collections [

2,

12,

14,

15]. For example, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France has encountered complications in reconciling its historical infrastructure with the requirements of modern environmental control, resulting in inconsistent humidity levels and ventilation issues [

16]. Several historic libraries (for instance the Vatican Apostolic Library) have also experienced difficulties maintaining environmental consistency, despite possessing HVAC infrastructure [

9,

17]. These examples underscore the limitations of conventional mechanical systems when applied in heritage contexts. Camuffo argued for a conservation-driven approach to climate control, advocating for adaptive methodologies that are sensitive to the historical and physical attributes of the structure [

18]. His findings reinforce the broader shift in heritage conservation towards flexible, minimally invasive environmental management strategies.

Ultimately, while HVAC systems are indispensable tools in many modern libraries, their application in historical contexts must be critically assessed. As emphasized by Staniforth, a successful conservation strategy should balance the benefits of technological intervention with the enduring resilience offered by passive climate regulation techniques [

18].

This paper presents the methodology and initial findings of an updated microclimatic monitoring campaign conducted at the University Library of Bologna (Biblioteca Universitaria di Bologna – BUL), one of Italy’s most historically significant library buildings. The study builds upon a previous monitoring phase carried out during the H2020 ROCK project (Regeneration and Optimisation of Cultural Heritage in Creative and Knowledge Cities_GA730280) between 2018 and 2020. The earlier results—focused on the performance of the library’s indoor environment with and without the heating system—were published in Boeri et al. [

19], highlighting the tensions between conservation strategies and energy use.

Furthermore, this paper focuses on the way the current boundary conditions of the library, which include both daily and seasonal meteorological variations, influence the indoor microclimatic conditions. Climate change is causing the boundary conditions to change over time. This dynamic puts the preservation of historic buildings at risk, as was reported in several studies including Fabbri K et al. [

2,

12] and in other studies focusing specifically on historical libraries [

8,

10,

14,

15,

16,

17,

20], such as Lankester P et al. [

21,

22] and Sandrolini F et al. [

23]. The damage produced by outdoor pollution, particularly that deriving from particulates, represents an additional thread, as pointed out in De la Fuente D et al [

24].

The thermal conditions, that must aim at the protection of goods as well as at the visitor thermal comforts, may be in contrast, as proved in an extensive literature [

25,

26,

27,

28]. Very often, the focus lies primarily on human comfort, which leads to the introduction of building services and systems. However, mechanical systems introduce “microclimate stress conditions” for buildings and their contents, radically changing the originally planned microclimatic logics.

Several studies have investigated similar issues in heritage libraries and archival buildings. Camuffo et al. (2010), for instance, documented the risks posed by inconsistent microclimatic conditions in historical buildings, emphasizing the long-term degradation effects on manuscripts and rare books [

29]. Leissner et al. (2015) , within the European Climate for Culture project (

https://www.heritageresearch-hub.eu/project/climate-for-culture/), explored how climate change and human-induced variations affect indoor environments in heritage sites, including libraries, pointing out that increased visitor presence can significantly alter local microclimates, sometimes leading to unacceptable fluctuations in temperature and humidity [

30]. Similarly, Michalski (2007) discussed the conflict between conservation standards, such as those recommended by the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) [

31] or EN 15757, and human comfort needs, especially in multifunctional heritage spaces [

32].

Since the first 2018-2020 monitoring campaign, the functional use of BUL’s spaces—especially the Great Hall—has progressively shifted from traditional library activities toward broader cultural and community engagement, necessitating a reassessment of the environmental conditions [

33]. The functional use of the library spaces—particularly the iconic Great Hall—has evolved considerably over recent years. While previously limited to research and archival consultation, the premises are now increasingly used for lectures, exhibitions, and public events. These activities generate greater internal loads (e.g., from lighting, body heat, and ventilation requirements), which can result in destabilized environmental conditions that threaten the long-term stability of stored materials.

In response to these changes, and recognizing the limitations of the original monitoring system, a new campaign was launched in September 2024 under the ECOSYSTER project, part of Italy's National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP) in the framework of NextGenerationEU (

https://ecosister.it/). This updated initiative employs a newly installed monitoring system to investigate the microclimatic dynamics of BUB's three principal rooms. The main objectives are to establish risk thresholds for climate-sensitive assets, inform the management and use strategies for different spaces, reconcile conservation requirements with occupant comfort, and explore the relationship between indoor climate conditions and energy consumption patterns.

By presenting the methodological framework and initial results of the 2024 monitoring project, this paper contributes to the broader discourse on sustainable heritage management, offering insights that can support the resilience and adaptive reuse of historic library environments.

2. Materials and Methods

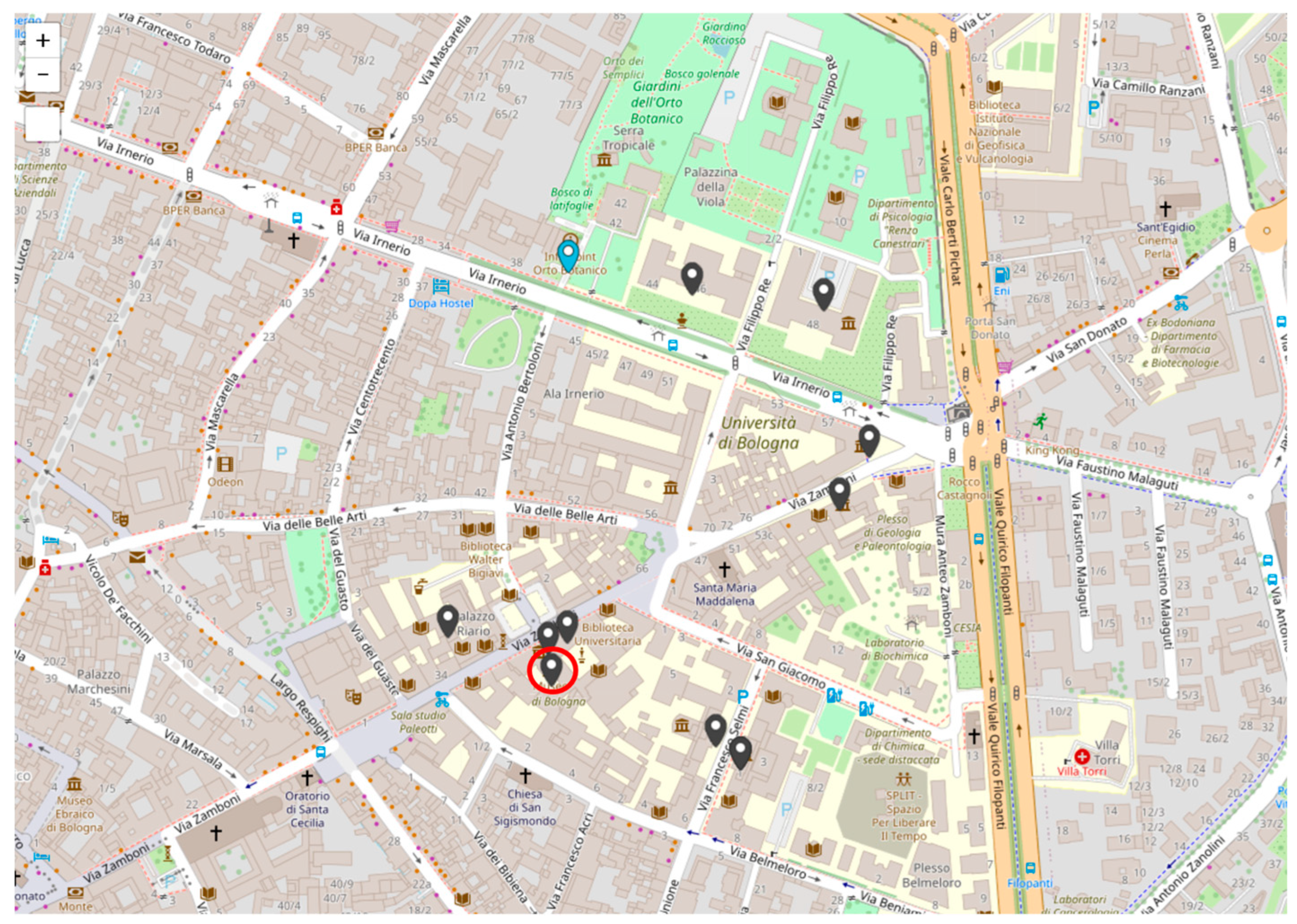

2.1. The Bologna University Library Case Study

The Bologna University Library (BUL) was built in 1712 by Luigi Ferdinando Marsili, a Bolognese aristocrat that decided to donate to the Alma Mater Studiorum University his personal library. In 1742 the library increased its collections of scientific books, manuscripts, xylography’s, etc. thanks to Ulisse Altrovandi, one of a most important Naturalist of XVIII Century. In 1755, Pope Benedict XIV Prospero Lambertini, Bolognese, further expanded the librarian collections. In 1869, the BUL became an Italian library. Since 2000, it has been managed and administered by the University of Bologna.

- (a)

the Great Hall, a large room where the original solid walnut shelving on two orders are present and where about 30,000 ancient volumes are stored; it is part of the museal path and it is occasionally used as a conference room;

- (b)

the Special Collections Room, where the Library people and consultation/study are located;

- (c)

the Mezzofanti Room, accessed by a security door, where the archives are located.

The choice of the project is to monitor the three rooms with 4 temperature and relative humidity sensors, as these are the physical variables that can most likely cause damage to the precious books and furniture, which are present in all three rooms.

The objective of the 2024 monitoring project of the premises of the Bologna University Library is to know, for individual rooms, the specific microclimatic conditions and historical climate, in order to define:

- (a)

the alert ranges in case of microclimate risk;

- (b)

the choices and methods of management and use of the different environments, because it will be part of the museum tour; and

- (c)

the right balance between conservation needs and the comfort of staff, users, and visitors (attendance and access management);

- (d)

as well as any other problems or needs that may arise during the monitoring campaign.

The library building itself presents unique challenges due to its architecture: large brick masonry, wooden and brick flooring, and substantial wooden furniture—all of which interfere with the transmission of radio signals, particularly at the 2.4 GHz frequency used by many wireless devices. To address this, a series of transmission tests were conducted, and the final configuration of the monitoring system was agreed upon and confirmed by Irene Schena, a technical expert on the University Library staff responsible for managing the library's computer networks and facilities.

The air temperature and relative humidity in these rooms are influenced by several factors: external climate variations, the presence of heating systems (with the exception of the archive in the Mezzofanti Hall), and crowd density, particularly in the Great Hall and Special Collections Room. These variables require constant monitoring to ensure the integrity of the library's holdings.

2.2. Methodology

The ongoing monitoring project is designed to provide data and tools that will facilitate the management of these changes, alongside the current use of the Special Collections Room and the need to define the historical climate of the archive for material loans. By doing so, the project seeks to strike an effective balance between the library’s new public-facing role and its fundamental mission of preserving historical materials.

To address these challenges, the monitoring project has selected the three overmentioned rooms for the climate monitoring, equipped with four temperature and relative humidity sensors. These two physical variables—temperature and humidity—are the most critical in terms of potential damage to the library’s collections and furniture, which are sensitive to fluctuations in both. The damage from uncontrolled microclimates can include condensation and mold growth on paper, books, and wooden furniture, as well as physical-chemical degradation that may foster the development of biological pests such as insects, woodworms, and moths.

The air temperature and relative humidity in these rooms are influenced by several factors: external climate variations, the presence of heating systems (with the exception of the archive in the Mezzofanti Hall), and crowd density, particularly in the Great Hall and Special Collections Room. These variables require constant monitoring to ensure the integrity of the library's holdings.

In addition to temperature and humidity sensors, two additional probes have been installed to measure CO2 levels, volatile organic compounds (VOCs)—chemical pollutants commonly found in detergents, solvents, and other substances—and particulate matter (PM). The CO2 and pollutant measurements are particularly important in rooms frequently used for public events, where human activity can contribute to indoor air quality issues. These probes are strategically placed: one near the speaker's chair in the Great Hall, where an electrical outlet is available, and the other in the Special Collections Room, near the border router (Sphensor Gateway) connected to the university’s Ethernet LAN network.

2.3. Features of the Sphensor Monitoring System

The monitoring system installed at the University Library of Bologna provides continuous measurement of various environmental parameters to ensure the conservation and protection of the artistic and historical heritage. Additionally, it monitors conditions that may pose a risk to objects and people. This is achieved through a network of indoor multi-parameter sensors that track temperature, humidity, pressure, CO2 levels, volatile organic compounds (VOC), particulate matter (PM), and illuminance. Data is transmitted via radio protocols and visualized on a Cloud-based software platform for analysis and decision-making. The probes and associated materials were supplied by LSI-LASTEM (Milan, Italy.

https://lsi-lastem.com/).

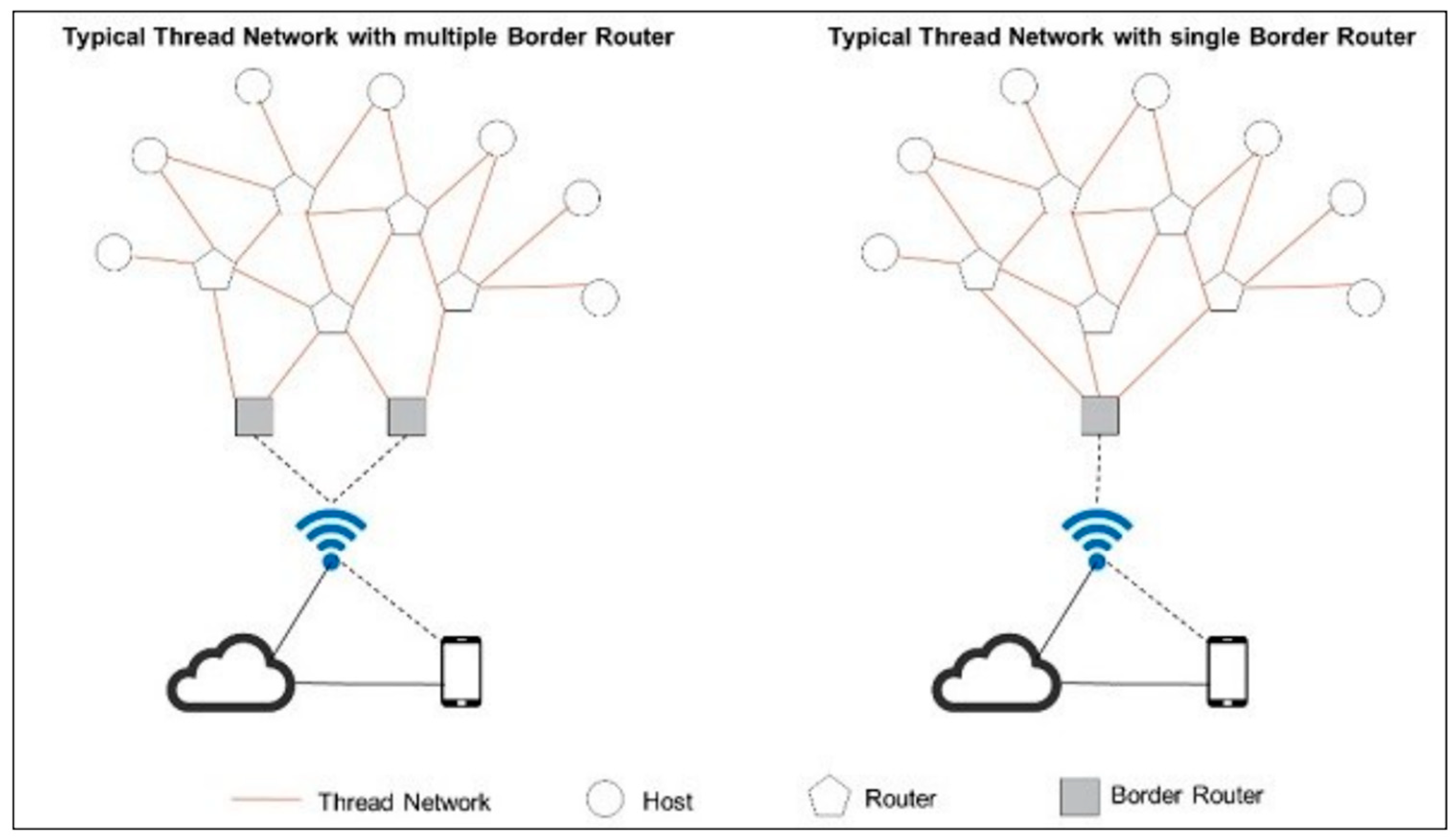

2.3.1. System Architecture and Monitoring Equipment

The system's architecture for data acquisition and transmission consists of the following components:

Multi-parameter sensors: These are distributed throughout the monitored rooms. Some sensors are battery-powered, while others draw power through USB connections, ensuring low energy consumption and long-term sustainability.

Radio transmission: Sensor probes transmit the collected data wirelessly to the Sphensor Gateway (border router¸

https://lsi-lastem.com/products/sphensor/), which, in turn, communicates with the Cloud platform through a local area network (LAN) via an Ethernet connection.

The monitoring system deployed on-site consists of:

Four T-RH probes: These probes measure temperature, relative humidity, air pressure, illuminance (lux), and UV-A radiation, providing critical data for both the preservation of collections and the management of room conditions.

Two PM-CO2 probes: These measure particulate matter (PM 1, PM 2.5, PM 4, PM 10), volatile organic compounds (such as benzene, tetrachloroethene, and other VOCs), and carbon dioxide (CO2). This is essential for assessing indoor air quality, particularly in spaces frequently used by the public.

Sphensor Gateway: This serves as the border router for the Thread network and is connected to the University of Bologna's LAN (Ethernet) network (

https://lsi-lastem.com/it/prodotti/sphensor/). It acts as the central hub for collecting and transmitting data from the sensor probes.

Cloud platform (LSI LASTEM Cloud Service ENVIRO CUBE;

https://lsi-lastem.com/products/enviro-cube/). This platform enables the configuration of individual sensors, the management of the monitoring plan, and the retrieval of data. Data can be accessed through standard reports generated by the platform, or they can be exported in Excel (*.xls) or text (*.csv) formats for further analysis, processing, or archiving.

2.3.2. Data Transmission and Processing

The data collected by the sensors are transmitted wirelessly via a radio signal to the Sphensor Gateway. The Gateway’s primary role is to decode the incoming messages sent from the probes through the Thread protocol and relay them to an MQTT broker, which is accessible via the Ethernet connection within the University of Bologna’s LAN network. Once the data is transmitted to the MQTT broker, it is forwarded to the Cloud platform, where it is stored and made available for real-time monitoring and historical analysis (

Figure 4). This advanced infrastructure provides a robust and reliable means of continuously tracking environmental conditions, ensuring both the optimal preservation of the library's assets and the safety of people using the space. The system’s flexibility allows for custom reporting and data management, making it an invaluable tool for long-term conservation and operational decision-making.

First phase: The process of designing, setting up, and launching the monitoring system for the University of Bologna Library is divided into two key phases: the initial phase involves the installation and calibration of the system, and the second phase focuses on the consolidation of the configuration and the full-scale launch of the monitoring campaign.

During the first phase, the following activities were carried out:

Delivery, inspection, and testing of equipment: the probes and associated materials supplied by LSI-LASTEM were thoroughly inspected and tested to ensure they were in optimal working condition.

Site survey and installation: a detailed site survey was conducted to determine the optimal locations for the probes, followed by their installation. The technical integrity of the internal radio network and the connection to the local LAN was also tested to ensure seamless data transmission.

Activation and data transmission: the system was activated, and data transmission was successfully established with the INDOOR CUBE cloud platform, ensuring that all components were functioning properly and transmitting real-time data.

Initiation of the monitoring campaign: after system activation, the monitoring campaign officially began, and initial results started to be generated and analyzed.

Following the completion of the on-site installation and setup, the microclimate monitoring of the Bologna University Library became fully operational, continuously transmitting data as of September 5, 2024. The system now provides valuable insights into the environmental conditions of the library’s interiors, with data being continuously recorded and processed.

3. Results

The first results from the monitoring campaign allow for an initial assessment of the system’s performance and the accuracy of the data collected. These initial findings provide:

Trends for individual variables: a detailed analysis of each probe's readings, including comparisons between different environments within the library.

Graphical representation of measurements on a psychrometric diagram: this visualizes the relationship between temperature, humidity, and air conditions, helping to identify any deviations from optimal microclimatic conditions.

Carbon Dioxide concentration and occupancy patterns: The system monitors carbon dioxide levels to assess crowding and indoor air quality, especially in spaces with high foot traffic.

3.1. Indoor Microclimate: Air Temperature Trend and Relative Humidity

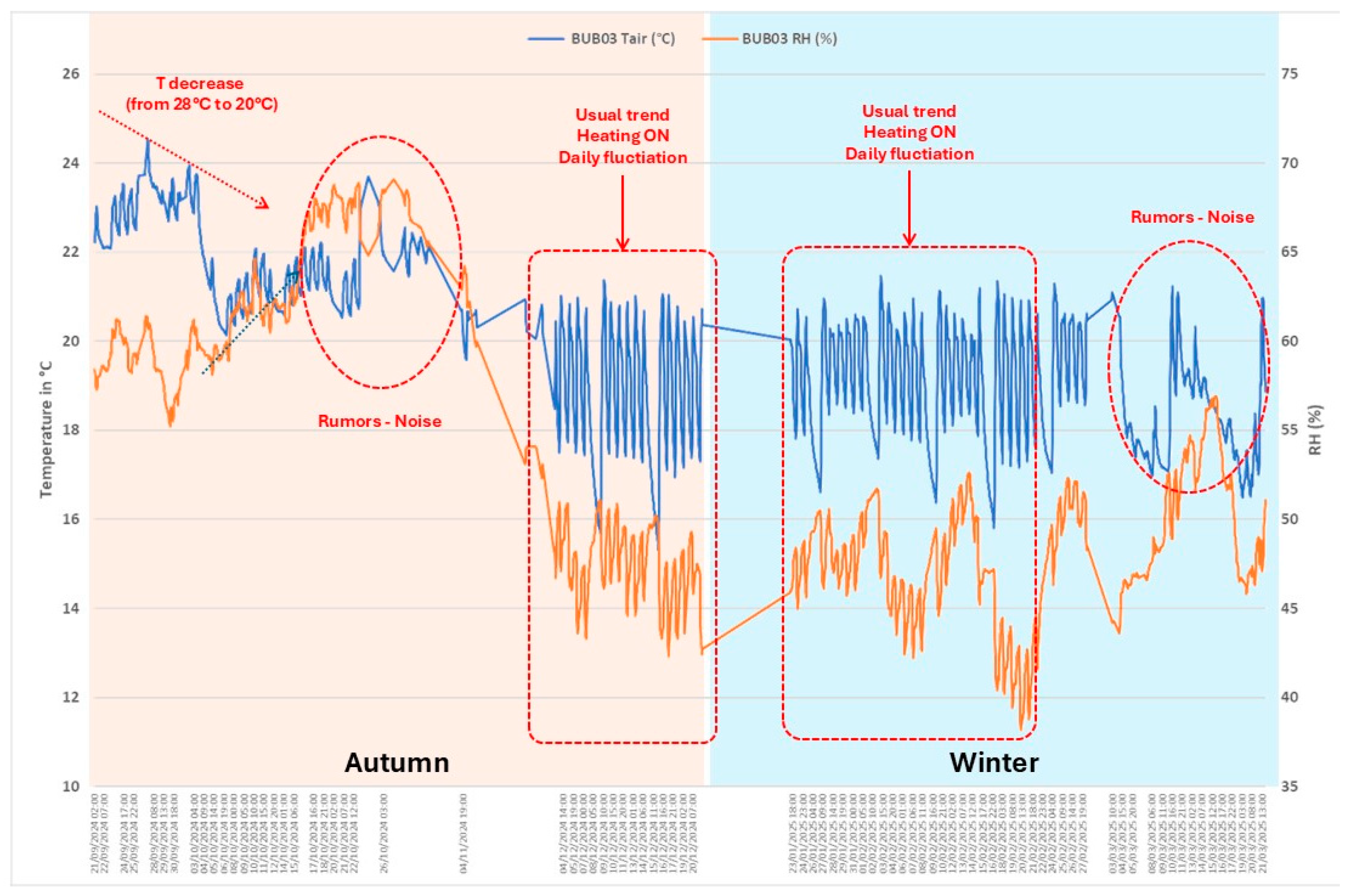

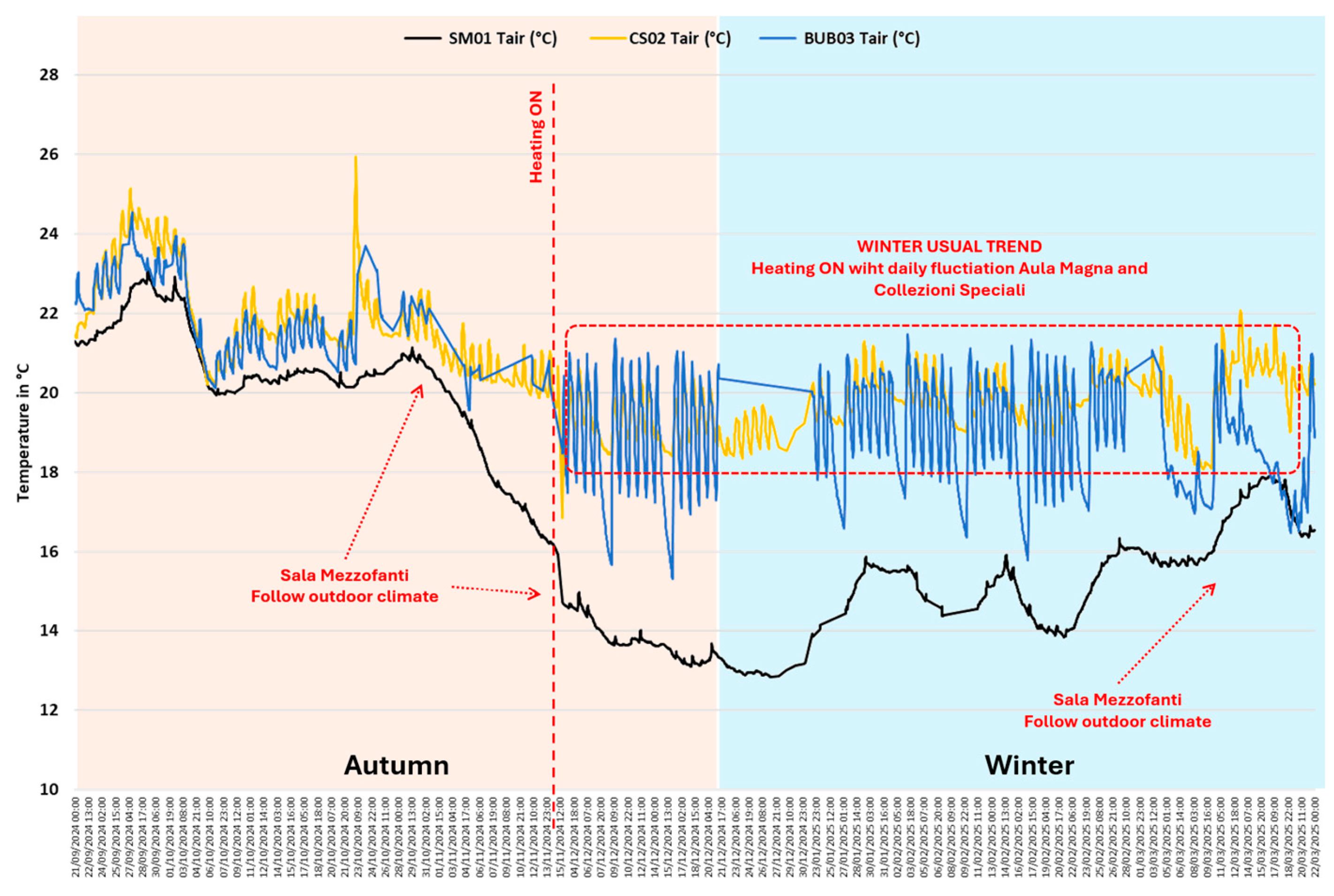

The graphs from the probes installed in the loft areas of the Great Hall (see

Figure 5) indicate air temperature values ranging between 24°C and 29°C, with a gradual decrease over time. This trend is particularly evident on September 13, when a notable temperature drop occurred, likely due to the shift in external weather conditions signaling the end of the long, hot summer of 2024, and the transition to cooler autumnal conditions.

The relative humidity (RH) values recorded by the probes are between 55% and 65%, which is consistent with the environmental characteristics of the library and its usage. Both graphs display a sinusoidal pattern, which reflects the daily fluctuations in temperature and humidity due to various factors such as the presence of people and the operation of equipment (e.g., lighting, computers, and HVAC systems). These fluctuations are closely aligned with the library’s access hours and usage intensity.

In

Figure 5 we can observe a decrease in temperature in September, after the long hot summer of 2024 that lasted until mid-October and beyond. After that period, with the activation of the heating systems, we can see an oscillatory trend, characteristic of the indoor microclimate during the period of activation of the heating systems. Finally, we verified that, compared to the usual trend, there are periods during which the indoor microclimate has turbulence, rumors and noise. This phenomenon is probably related to users’ attendance and/or to considerable outdoor climate variations. It will be investigated at the end of the annual campaign.

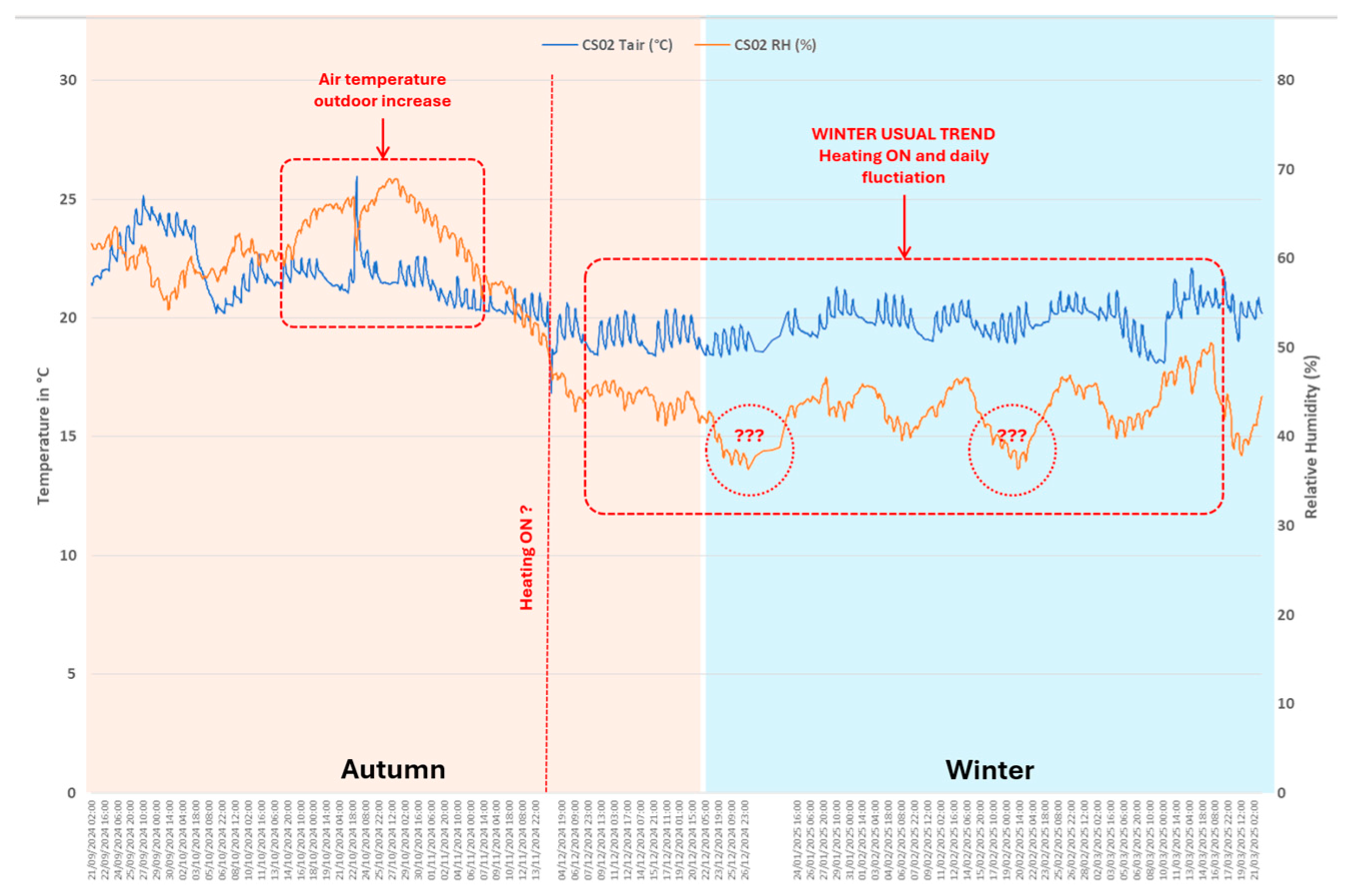

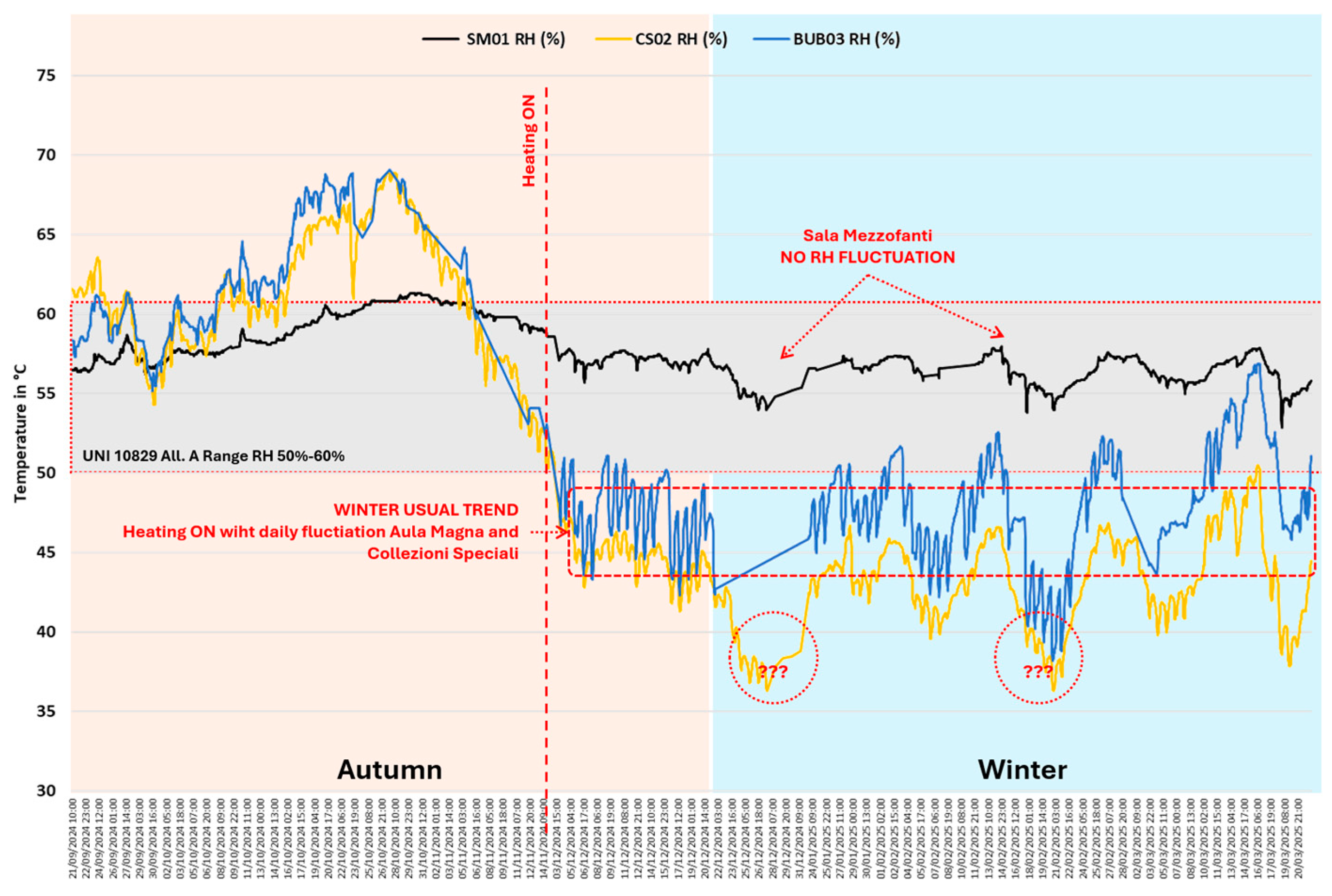

The graph for the probe installed in the Special Collections Room (see

Figure 6) indicates temperature values ranging between 23°C and 30°C, with a noticeable downward trend. A significant temperature drop begins on September 13, marking a clear shift in environmental conditions. This decrease in temperature aligns with the broader climatic transition occurring around this period. Once again, it can be seen that the indoor microclimate changes in correspondence to the activation of the Heating system: the air temperature trend undergoes the daily fluctuations of turning on/off the heating system and the suspension during the weekend. The fluctuation of relative humidity values shows some days when the value is below 40% (dry environment). This is probably related to the crowding of people or the set-point temperatures of the heating system; this will also be investigated at the end of the annual campaign.

The relative humidity (RH) levels in the room fluctuate between 55% and 70%, which is typical given the nature of the space and its usage. However, it's important to highlight the sharp decline in relative humidity just before and after September 13, where the RH values drop by nearly 15%. This sudden shift may be attributed to a combination of external weather changes and the internal environmental control systems, such as HVAC adjustments or variations in the number of occupants in the room. The abrupt decrease in humidity during this period is particularly significant, as it can impact both the preservation of the delicate materials housed in the Special Collections Room and the overall indoor air quality. These fluctuations in microclimatic conditions warrant close monitoring, as they could pose potential risks to both the stored materials and the comfort of those accessing the room. Further investigation may be necessary to identify the precise cause of this rapid change and to implement preventive measures to maintain stable conditions.

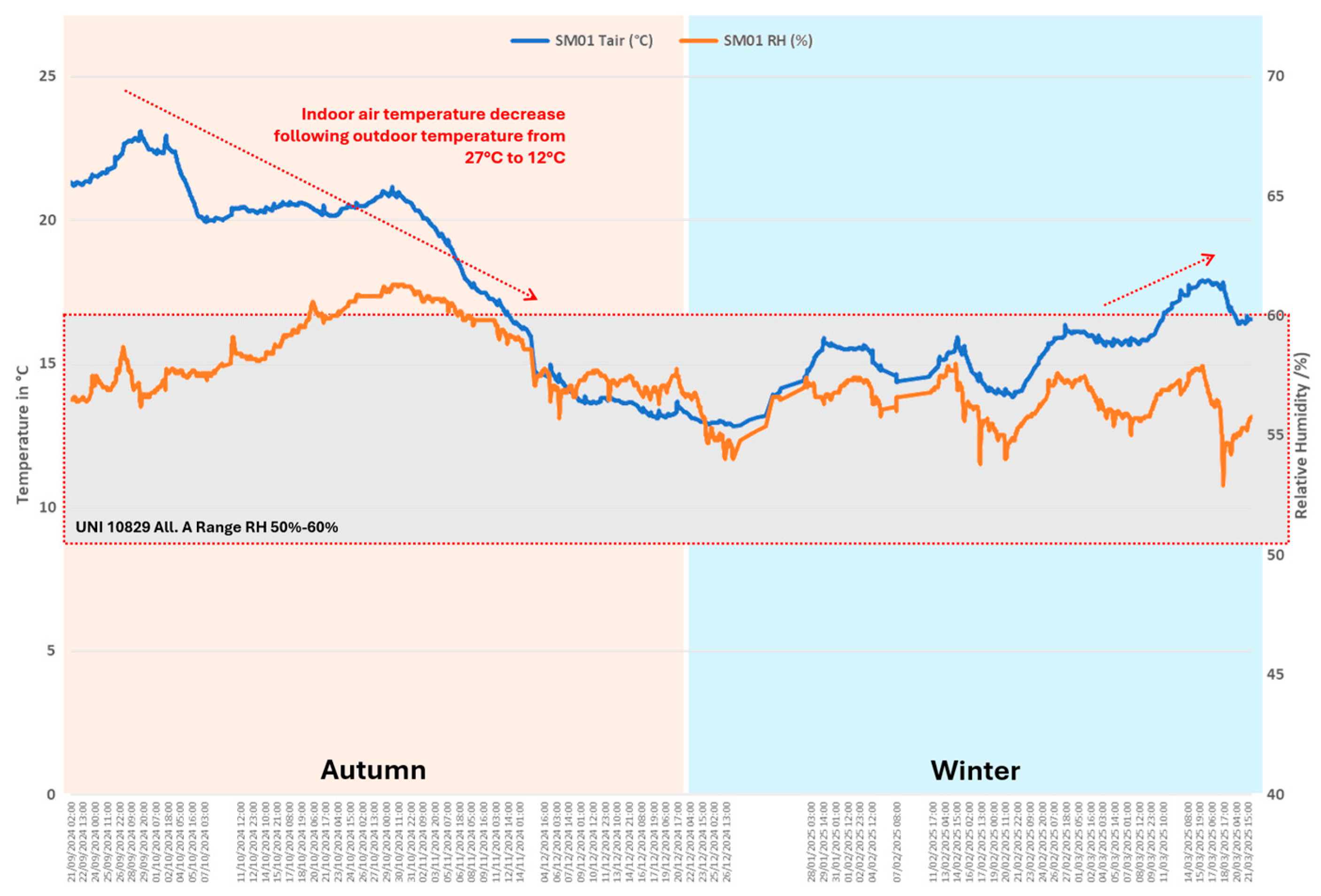

The graph from the probe installed in the Mezzofanti Hall (see

Figure 7) shows temperature values ranging from 23°C to 28°C and relative humidity levels between 52% and 58%. Unlike other monitored spaces, the reduction in both temperature and humidity after September 13 occurs in a slow and gradual manner, reflecting the unique conditions of this hall.

One notable difference from the previous graphs is the stability of the values recorded in the Mezzofanti Hall, with no significant daily fluctuations. This consistency can be attributed to two main factors: the absence of active HVAC systems, which eliminate artificial influences on the room’s microclimate, and the limited foot traffic in the hall, resulting in fewer disturbances to the environmental conditions.

In other words, the microclimatic conditions in the Mezzofanti Hall closely follow the natural variations in external weather, leading to more stable and uniform measurements. This indicates that the hall, unlike spaces with higher occupancy and active climate control systems, maintains a relatively passive and consistent environment, which could be advantageous for the preservation of sensitive materials stored within.

A comparative analysis of the air temperature trends in the three rooms (

Figure 8) reveals a noticeable difference of approximately 3°C to 4°C between the Special Collections Room and the Great Hall, with the highest temperatures recorded in the latter. This is likely due to temperature stratification near the loft area in the Great Hall—an aspect that warrants further investigation. In both rooms, the sinusoidal patterns in temperature reflect the natural daily cycles and fluctuations, with distinct peaks corresponding to periods of higher occupancy or system activation.

In contrast, the Mezzofanti Hall consistently shows a temperature 1°C to 1.5°C lower than that of the Great Hall, while it is 1.5°C to 2°C higher than the Special Collections Room. This difference may be attributed to the placement of probes near the loft in the Great Hall and the presence of fans in the Special Collections Room, which are used to enhance staff comfort and could influence localized temperature variations.

When comparing relative humidity values (

Figure 9), greater variability is evident, especially in the Great Hall and Special Collections Room, where fluctuations of up to +3% to +5% are recorded throughout the days. A more pronounced shift is observed around September 13, with humidity levels in these two rooms exhibiting a sharp +/- 15% change before and after this date. This sudden fluctuation likely correlates with external weather changes or adjustments to environmental control systems within these spaces.

In contrast, the Mezzofanti Hall—which serves as an archive—maintains a notably stable microclimate. The relative humidity in this room shows minimal fluctuations, both throughout the day and over the entire monitoring period, highlighting the controlled and consistent environmental conditions that are crucial for the preservation of sensitive archival materials. The difference between the dynamic microclimatic conditions in the Great Hall and Special Collections Room and the steady, regulated environment in the archive is particularly evident, emphasizing the varied microclimatic demands across different areas of the library.

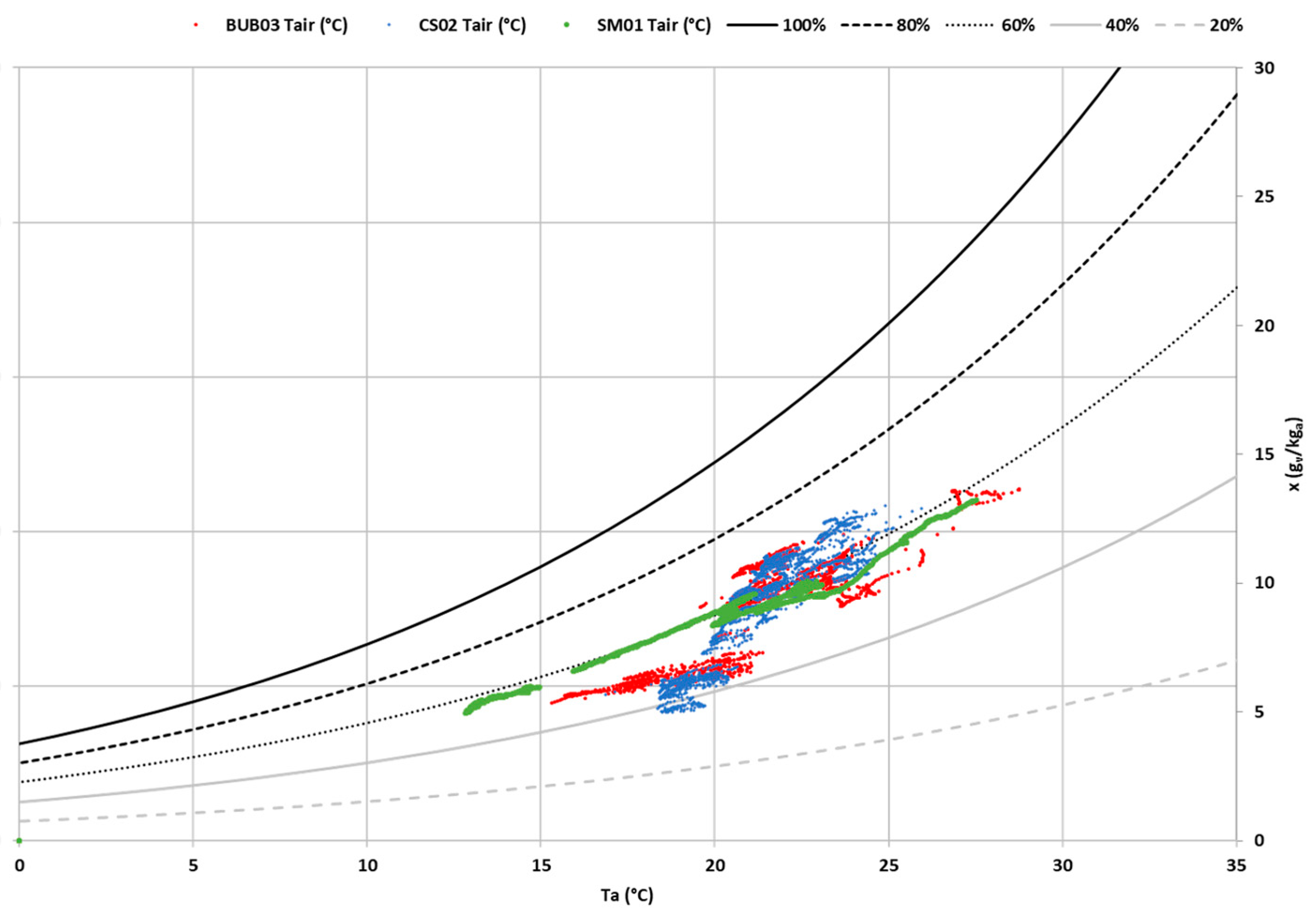

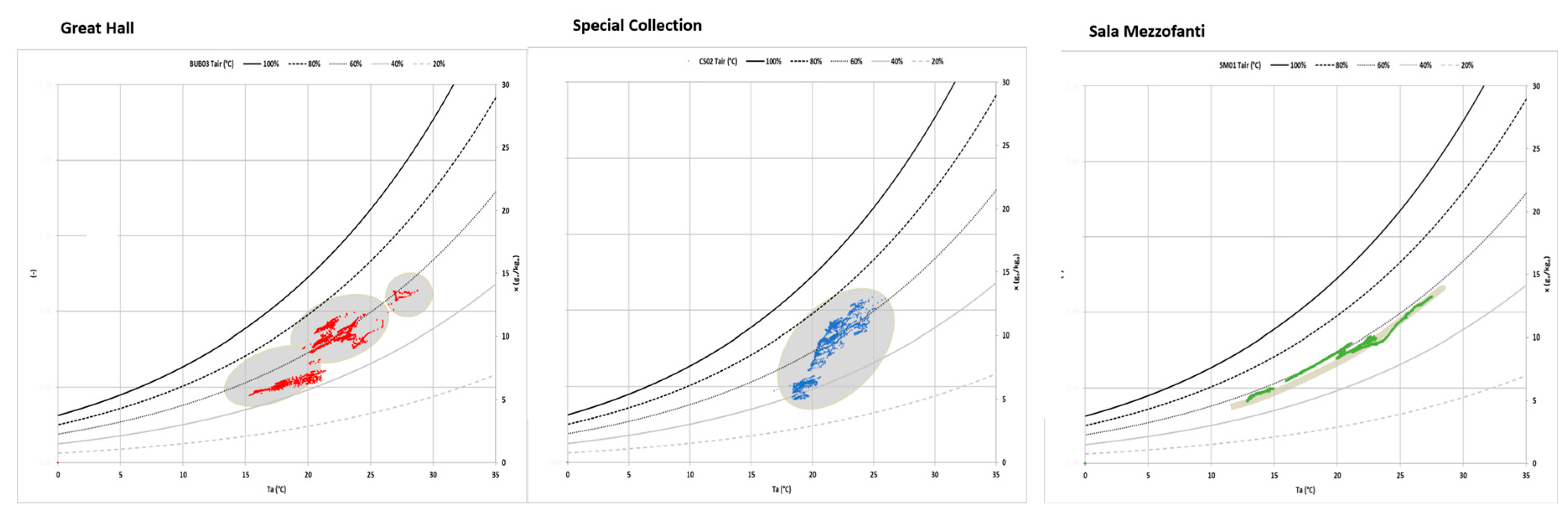

3.2. Indoor Microclimate on Psychrometric Chart

The psychrometric diagram is a valuable tool used across various disciplines, particularly in the study of indoor microclimates, assessing human thermal comfort, and designing air treatment systems. By plotting the distribution of measured data points on a psychrometric chart, it becomes possible to characterize the microclimate of indoor environments.

In the context of the University Library, even though the monitoring period has been relatively short, we can already derive some initial insights.

Figure 10 illustrates the data recorded by the four probes plotted on the complete ASHRAE Psychrometric Chart, while

Figure 11 provides a detailed elaboration created by the undersigned for further analysis.

The data collected from the BUL probes (represented in red and blue) exhibit a distinctive pattern of disaggregated and distributed values, appearing to cluster around two distinct poles. This configuration is indicative of environments with air conditioning, where the distribution of points often forms a double elliptical pattern, reflecting the cyclical nature of the air treatment system's operation.

In contrast, the Special Collections Room (represented in orange) shows a more compact, circular point cloud, which is characteristic of air-conditioned spaces with consistent occupancy and controlled microclimate conditions. The elliptical-to-circular shape of the point cloud is typically observed in environments where both temperature and humidity are actively regulated, and the presence of people introduces regular heat and vapor loads, further stabilizing the environmental conditions.

Finally, the data from the Mezzofanti Room (represented in green) displays a markedly different distribution. The points form an elongated, almost linear ellipse, following a line of constant relative humidity (RH = 60%). This distribution is typical of non-air-conditioned environments, where there are no significant internal heat or vapor sources, such as human occupancy or mechanical systems. In this case, changes in the indoor microclimate are driven primarily by external temperature variations, while the relative humidity remains stable, showing minimal fluctuation. This type of linear pattern reflects the natural response of an environment to external climatic changes, with little internal disruption to the microclimate.

In summary, the psychrometric diagram provides a clear visual representation of how different environments within the library—whether air-conditioned or not—behave in terms of temperature and humidity. The BUB probes show a typical air-conditioned behavior, the Special Collections Room demonstrates controlled conditions suited for preservation and occupancy, while the Mezzofanti Room exhibits a stable, naturally regulated environment, ideal for archival storage.

3.3. Carbon Dioxide Values and Human Presence

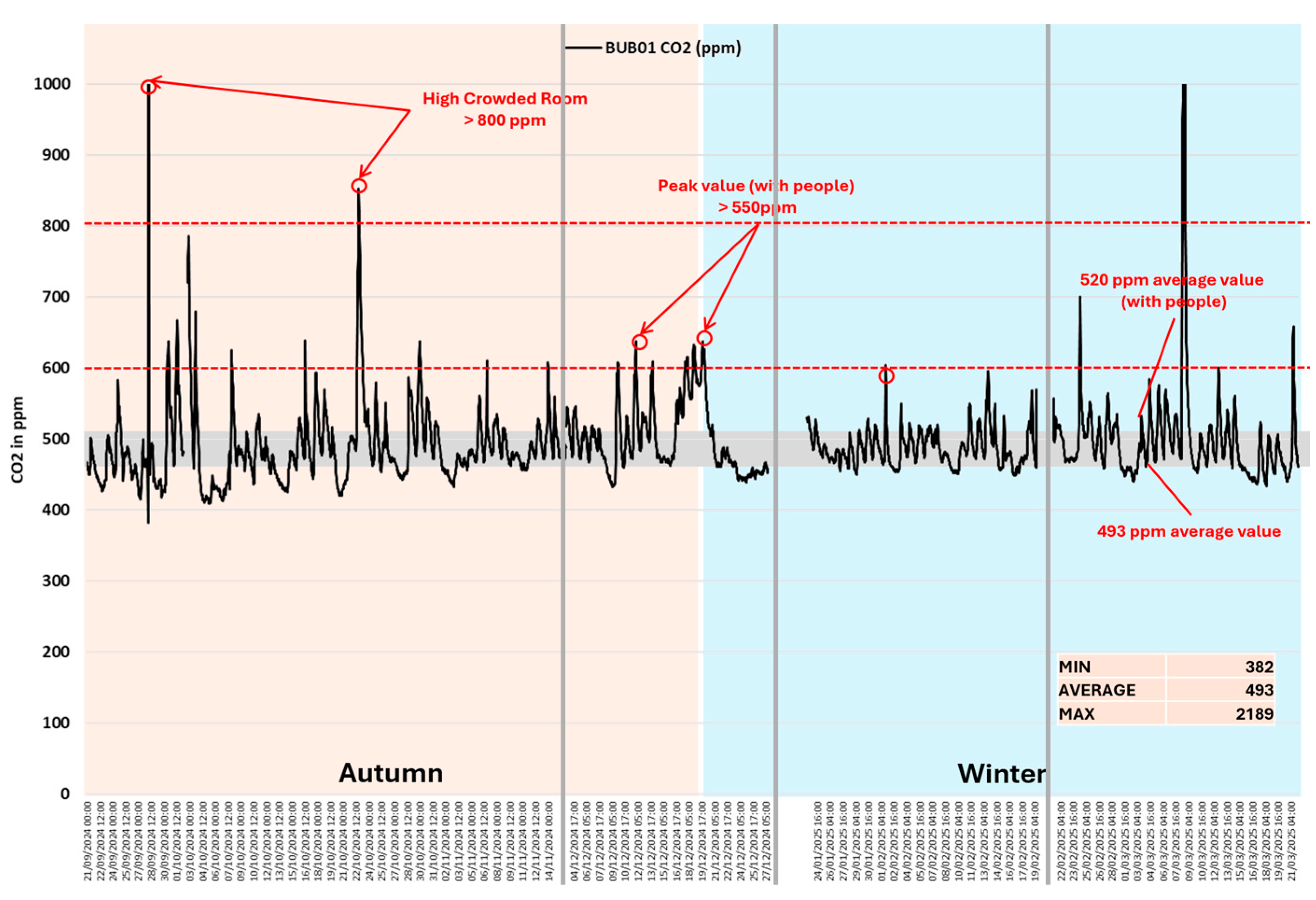

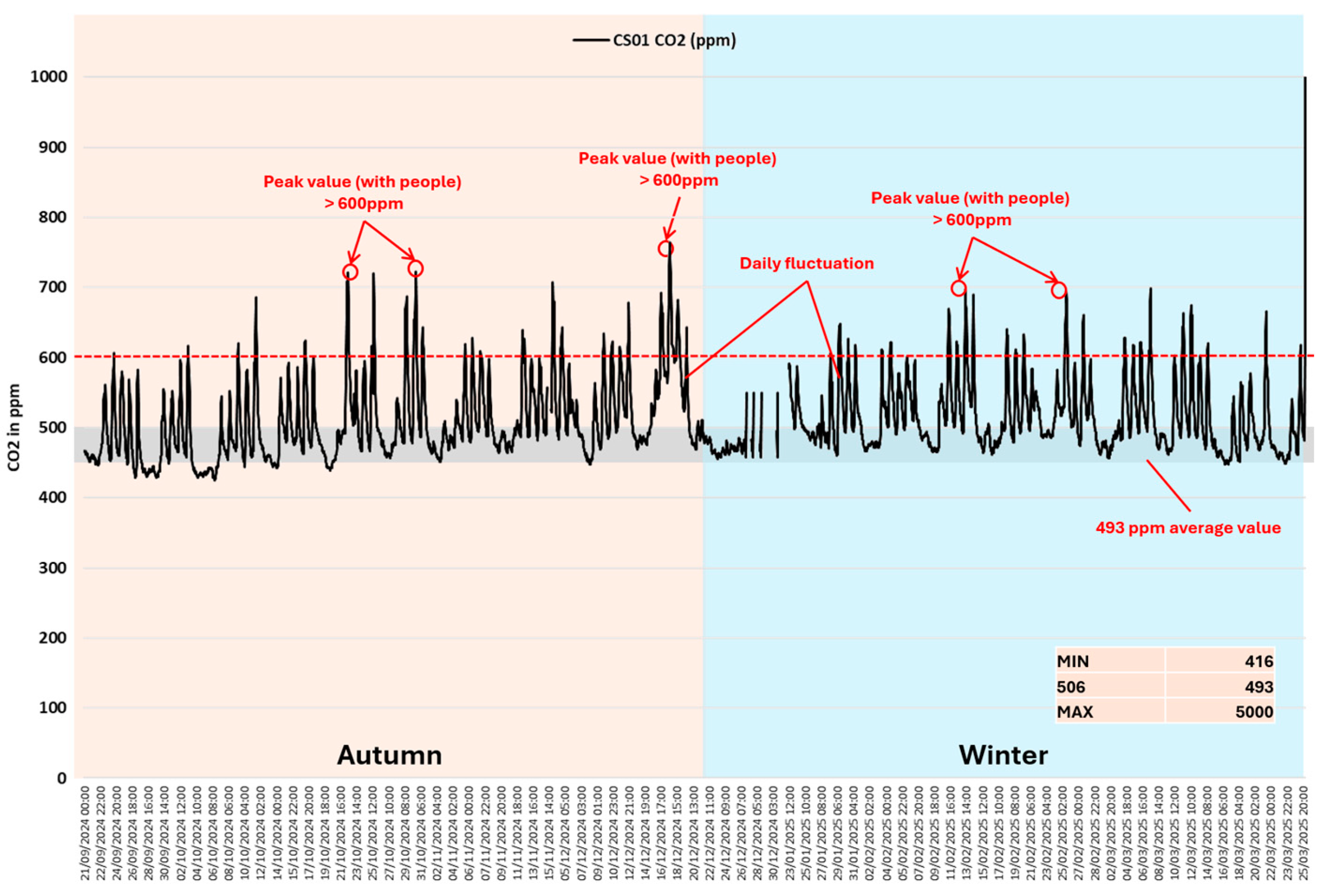

The graphs depicting the trend of Carbon Dioxide (CO2) values (see

Figure 12 and

Figure 13) show readings between 400 ppm and 500 ppm (represented by the gray area), which correspond to the baseline CO2 concentrations typically found in indoor environments. It is common to observe CO2 levels indoors that are approximately 400 ppm higher than those recorded outdoors, as indoor air is influenced by human activity. These results align with standard CO2 concentration values reported in the literature for indoor spaces.

CO2 is widely regarded as a reliable indicator of human presence in enclosed environments, as it is directly emitted through respiration. Both graphs exhibit a sinusoidal pattern, reflecting daily occupancy patterns: CO2 levels rise sharply during the working day as people enter the rooms, reaching a peak, and then gradually decline (diluting) during the evening and night hours when the rooms are unoccupied.

In the Special Collections Room (

Figure 14), the CO2 peaks closely follow the working hours, clearly demarcating periods of activity. It is important to note that the probe in this room is positioned near the staff workstations, making the CO2 levels highly sensitive to staff presence and daily routines.

In the Great Hall, by contrast, there is a noticeable spike in CO2 levels up to 900 ppm at noon on September 9, likely caused by a momentary increase in the number of people present in the room or near the probe. This could be due to a small event, meeting, or gathering that temporarily heightened CO2 levels. Such spikes are significant as they highlight variations in occupancy and the need for ventilation adjustments to maintain optimal air quality in large, periodically crowded spaces.

Overall, the data indicates that CO2 levels are closely tied to human occupancy in both rooms, with predictable daily cycles. However, localized spikes, such as the one observed in the Great Hall, underscore the importance of real-time monitoring to manage indoor air quality effectively, particularly during events or periods of increased foot traffic.

4. Discussion

The EN 15757 [

3] requires at least one year of monitoring for a complete understanding of the historical climate (“Historical climate: Climatic conditions in a microenvironment where a cultural heritageobject has always been kept, or has been kept for a long period of time (at least one year) and to which it has become acclimatize”, point 3.5) [

3,

4,

5,

7,

12,

34].

The results show how an indoor microclimate monitoring system in place is extremely useful. This presence, in fact, allows hypotheses and strategies to be made as early as the first data acquisition phase. This is an advantage for two reasons: on the one hand, it makes it possible to assess whether the arrangement of the sensors, the radio data transmission system, communication via Wi-FI, and cloud interrogation are suitable for the specific case without having to wait for a year of monitoring; on the other hand, the first data allow hypotheses to be advanced on how the rooms are used in relation to various activities, such as the lending of artifacts, books, or manuscripts, and/or on the possibility of extending the monitoring system, for example to the Marsili Museum, which, in our case, is located in a neighboring room.

Regarding the first aspect mentioned above, thanks to the flexibility of the LSI Sphensor system and the radio data transmission system, it was possible to obtain homogeneous data even when one of the two probes on the balcony reposition was necessary after the first three weeks of monitoring. Processing data using psychrometric diagrams remains cumbersome. Nevertheless, the identification of the role of the thermal systems in the winter season and of the difference of the archive microclimate compared to other environments are already possible.

Compared with the previous research conducted on BUL in the ROCK project during the 2018-2020 period, the flexible, catalog-based system used in the current monitoring campaign provides greater assurance of continuity in data collection. Moreover, evaluations regarding the concentration and trend of CO2 as well as its dilution time provide useful information regarding the use of the rooms for activities not currently planned or not yet established, such as the use of the Great Hall for conferences, which is currently used sporadically, or such as the inclusion of the BUL in the museum itinerary of Palazzo Poggi, which will result in a significant increase in the presence of people.

Regarding the second aspect, the BUL is incorporated in Palazzo Poggi which is part of the University Museum Network of the University of Bologna (

www.sma.unibo.it/en). The catalogue of the Palazzo Poggi Museum is a journey through naturalistic collections, xylographic matrices, maps and naval models, and anatomical preparations in wax and terracotta, all of which tell the story of the Ulisse Aldrovandi Museum and the Institute of Arts and Sciences. The University Museum Network includes 4 other museums and collections on Via Zamboni, within a hundred meters from the BUB: Specola Museum of Astronomy, European Museum of Students (MEUS), Geological Collection "Giovanni Capellini Museum" and Mineral Collection "Luigi Bombicci Museum", to which are added the more distant university museums on Via Irnerio (Botanic Garden and Herbarium, "Luigi Cattaneo" Anatomical Wax Collection, Collection of Physics Instrument) e on Via Selmi (Zoological Collection, Giacomo Ciamician Chemistry Collection, Comparative Anatomy Collection).

The extension of the monitoring system discussed in this article to the entire Poggi Museum or the entire museum network described above, given its relevance, could be a very interesting development of the current experimentation. It may facilitate the choice of strategies for the preservation, display and enjoyment of museum assets, not only for the benefit of scholars, but also for the large university population that frequents the area, visitors and citizens (

Figure 15).

The deployment phase of the monitoring system required a series of trial and errors, particularly for both radio data transmission and communication with the Wi-Fi network. It was possible to optimize the monitoring system thanks to BUL's electrical engineers and the support of the university computer service (CESIA). In the signal settling phase (September-November), it was necessary to change the position of a probe because the radio signal at the frequency of 2.7 GHz could not pass through the thick walls. Moreover, in the first phase, the electrical system was turned off at the end of the day by the janitors, resulting in the loss of data in the early morning hours and at weekends. Thanks to the support of the BUB management, the problem was solved by leaving the system on all the time.

The coordination among those involved has made it possible to ensure the continuity of the monitoring system. In spite of this, it is recommended to adopt LoRa (Long Range) radio transmission in the future, which allows thick walls to be traversed. Another aspect concerns the wiring of electrical networks, which the administration plans to upgrade in the future; the ideal solution is to equip the BUL< with its own electrical system with the possibility of continuous power supply.

The indoor microclimate monitoring in heritage buildings, by providing data on the parameters of interest, enables the activation and planning of a series of measures and energy consumption optimization strategies, aimed at a sustainable management of the asset that goes beyond the containment of just energy consumption. In the case of BUL, the assurance of control of microclimatic conditions for the conservation of books and the prevention of possible risks, a key factor for heritage buildings, must be pursued first and foremost. In fact, the assessed thermal conditions are mandatory to guarantee book and manufact conservation. However, the thermal comfort of people using library spaces also assumes considerable importance.

The results of the current monitoring campaign, as reported in the Results section, show the role of the thermal systems, which, at present, are not optimized with respect to the needs of the place, as well as causing thermal fluctuations. At this stage it is not possible to intervene on the air conditioning systems being centralized for the whole building. It is desirable that the results of at least one year of monitoring will support the demand for a different and dedicated management system.

5. Conclusions

The first phase of the project, which involved the complete installation and activation of the on-site monitoring system and the Cloud INDOOR CUBE platform, has been successfully concluded. Being the monitoring system fully operational, the next steps of the research will focus on continuing the collection and analysis of data to accurately characterize the indoor microclimate of the Bologna University Library.

The primary objective is to define the Historic Climate of the library in accordance with the UNI EN 15757 standard [

13,

34]. This standard requires a full year of monitoring to establish a comprehensive understanding of the building’s climatic conditions and their potential impact on the preservation of its heritage materials.

In addition to this, the next phase will include:

Defining risk alerts and microclimate risk indices: this includes the development of Heritage Microclimate Risk (HMR) and Percentage Damage Risk (PDR) indices [

4,

5,

6] which will provide early warnings for environmental conditions that may pose a risk to the preservation of heritage materials. These indices will preferably be defined towards the end of the year-long monitoring period, once sufficient data has been collected.

Establishing the historical climate of the archive: this step is crucial for preparing condition reports for the lending of archival materials, ensuring that the environmental conditions of the library are suitable for both storage and transport.

Defining criteria for the use of spaces: as the library is integrated into a new museum itinerary, criteria will be established to guide the appropriate use of its premises, particularly regarding visitor access. The impact of increased foot traffic and new uses of space on the microclimate will be carefully evaluated. Furthermore, the extension of the microclimate monitoring system to adjacent spaces, such as those housing the Marsili Museum, will be considered to ensure the continued preservation of both the library’s and the museum's collections.

These next research steps will ensure a detailed and scientifically grounded understanding of the environmental conditions in the library, enabling effective conservation strategies and enhancing its role as both a research institution and a cultural site.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B., D.L, K.F. and R.R.; methodology, D.L. and K.F.; software, K.F.; validation, K.F.; formal analysis, K.F.; resources, A.B. and D.L.; data curation, K.F. and R.R.; writing—original draft preparation, R.R.; writing—review and editing, R.R., K.F., D.L. and A.B.; funding acquisition, A.B.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the ECOSYSTER_Ecosystem for Sustainable Transition in Emilia-Romagna project (CF: 91449190379; Code: ECS_00000033; CUP: B33D21019790006), part of the Italian National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP, in the context of NextGenerationEU) Mission 4, Component 2 Investment 1.5. https://ecosister.it/

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. Data can be available only after University of Bologna permission. Please contact: danila.longo@unibo.it

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Maria Pia Torricelli, BUL Director, and Professor Francesco Citti for their valuable help; moreover, the author thank the BUL and CESIA employees for their kind availability. The authors thank the LSI Lastem company (

https://lsi-lastem.com/), especially Pietro Amendola, for his help in data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Moretti, E.; Sciurpi, F.; Proietti, M.G.; Fiore, M. A Multidisciplinary Approach to the Evaluation of Air Quality and Thermo-Hygrometric Conditions for the Conservation of Heritage Manuscripts and Printed Materials in Historic Buildings: A Case Study of the Sala Del Dottorato of the University of Perugia as a Model for Heritage Preservation and Occupants’ Comfort. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 5356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, K.; Pretelli, M. Heritage Buildings and Historic Microclimate without HVAC Technology: Malatestiana Library in Cesena, Italy, UNESCO Memory of the World. Energy and Buildings 2014, 76, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chan, C.C.C.; Kwok, H.H.L.; Cheng, J.C.P. Multi-Indicator Adaptive HVAC Control System for Low-Energy Indoor Air Quality Management of Heritage Building Preservation. Building and Environment 2023, 246, 110910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Molina, A.; Tort-Ausina, I.; Cho, S.; Vivancos, J.-L. Energy Efficiency and Thermal Comfort in Historic Buildings: A Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 61, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kompatscher, K.; Kramer, R.P.; Ankersmit, B.; Schellen, H.L. Intermittent Conditioning of Library Archives: Microclimate Analysis and Energy Impact. Building and Environment 2019, 147, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif-Askari, H.; Abu-Hijleh, B. Review of Museums’ Indoor Environment Conditions Studies and Guidelines and Their Impact on the Museums’ Artifacts and Energy Consumption. Building and Environment 2018, 143, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfano, F.R.; d’Ambrosio; de Santoli, L. Energy Efficiency and HVAC Systems in Existing and Historical Buildings. In Historical Buildings and Energy; Franco, G., Magrini, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 45–53. ISBN 978-3-319-52615-7. [Google Scholar]

- Schito, E.; Pereira, L.D.; Testi, D.; Silva, M.G. da A Procedure for Identifying Chemical and Biological Risks for Books in Historic Libraries Based on Microclimate Analysis. Journal of Cultural Heritage 2019, 37, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verticchio, E.; Frasca, F.; Cavalieri, P.; Teodonio, L.; Fugaro, D.; Siani, A.M. Conservation Risks for Paper Collections Induced by the Microclimate in the Repository of the Alessandrina Library in Rome (Italy). Herit Sci 2022, 10, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.D.; Gaspar, A.R.; Costa, J.J. Assessment of the Indoor Environmental Conditions of a Baroque Library in Portugal. Energy Procedia 2017, 133, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varas-Muriel, M.J.; Fort, R.; Martínez-Garrido, M.I.; Zornoza-Indart, A.; López-Arce, P. Fluctuations in the Indoor Environment in Spanish Rural Churches and Their Effects on Heritage Conservation: Hygro-Thermal and CO 2 Conditions Monitoring. Building and Environment 2014, 82, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronchin, L.; Fabbri, K. Energy and Microclimate Simulation in a Heritage Building: Further Studies on the Malatestiana Library. Energies 2017, 10, 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camuffo, D.; Della Valle, A.; Becherini, F. The European Standard EN 15757 Concerning Specifications for Relative Humidity: Suggested Improvements for Its Revision. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andretta, M.; Coppola, F.; Seccia, L. Investigation on the Interaction between the Outdoor Environment and the Indoor Microclimate of a Historical Library. Journal of Cultural Heritage 2016, 17, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, C.D.; Coşkun, T.; Arsan, Z.D.; Gökçen Akkurt, G. Investigation of Indoor Microclimate of Historic Libraries for Preventive Conservation of Manuscripts. Case Study: Tire Necip Paşa Library, İzmir-Turkey. Sustainable Cities and Society 2017, 30, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brimblecombe, P.; Sterflinger, K.; Derksen, K.; Haltrich, M.; Querner, P. Thermohygrometric Climate, Insects and Fungi in the Klosterneuburg Monastic Library. Heritage 2022, 5, 4228–4244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verticchio, E.; Frasca, F.; Bertolin, C.; Siani, A.M. Climate-Induced Risk for the Preservation of Paper Collections: Comparative Study among Three Historic Libraries in Italy. Building and Environment 2021, 206, 108394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camuffo, D. Microclimate for Cultural Heritage; Developments in atmospheric science; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 1998; ISBN 978-0-444-82925-2. [Google Scholar]

- Boeri, A.; Longo, D.; Fabbri, K.; Pretelli, M.; Bonora, A.; Boulanger, S. Library Indoor Microclimate Monitoring with and without Heating System. A Bologna University Library Case Study. Journal of Cultural Heritage 2022, 53, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balocco, C.; Petrone, G.; Maggi, O.; Pasquariello, G.; Albertini, R.; Pasquarella, C. Indoor Microclimatic Study for Cultural Heritage Protection and Preventive Conservation in the Palatina Library. Journal of Cultural Heritage 2016, 22, 956–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brimblecombe, P.; Lankester, P. Long-Term Changes in Climate and Insect Damage in Historic Houses. Studies in Conservation 2013, 58, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankester, P.; Brimblecombe, P. Future Thermohygrometric Climate within Historic Houses. Journal of Cultural Heritage 2012, 13, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandrolini, F.; Franzoni, E.; Sassoni, E.; Diotallevi, P.P. The Contribution of Urban-Scale Environmental Monitoring to Materials Diagnostics: A Study on the Cathedral of Modena (Italy). Journal of Cultural Heritage 2011, 12, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Pacheco, J.; Ruiz-Ascencio, J.; Rendón-Mancha, J.M. Visual Simultaneous Localization and Mapping: A Survey. Artif Intell Rev 2015, 43, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, K. Energy Incidence of Historic Building: Leaving No Stone Unturned. Journal of Cultural Heritage 2013, 14, e25–e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Gennusa, M.; Lascari, G.; Rizzo, G.; Scaccianoce, G. Conflicting Needs of the Thermal Indoor Environment of Museums: In Search of a Practical Compromise. Journal of Cultural Heritage 2008, 9, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camuffo, D.; Pagan, E.; Bernardi, A.; Becherini, F. The Impact of Heating, Lighting and People in Re-Using Historical Buildings: A Case Study. Journal of Cultural Heritage 2004, 5, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, H.E.; Henriques, F.M.A.; Henriques, T.A.S.; Coelho, G. A Sequential Process to Assess and Optimize the Indoor Climate in Museums. Building and Environment 2016, 104, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camuffo, D.; Pagan, E.; Rissanen, S.; Bratasz, Ł.; Kozłowski, R.; Camuffo, M.; Valle, A. della An Advanced Church Heating System Favourable to Artworks: A Contribution to European Standardisation. Journal of Cultural Heritage 2010, 11, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leissner, J.; Kilian, R.; Kotova, L.; Jacob, D.; Mikolajewicz, U.; Broström, T.; Ashley-Smith, J.; Schellen, H.L.; Martens, M.; Van Schijndel, J.; et al. Climate for Culture: Assessing the Impact of Climate Change on the Future Indoor Climate in Historic Buildings Using Simulations. Herit Sci 2015, 3, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE ASHRAE Guideline 34-2019, Energy Guideline for Historic Buildings 2019.

- Stefan Michalski The Ideal Climate, Risk Management, the ASHRAE Chapter, Proofed Fluctuations, and Toward a Full Risk Analysis Model. In Proceedings of the Contribution to the Experts’ Roundtable on Sustainable Climate Management Strategies; Getty Conservation Institute: Tenerife, Spain, April 2007.

- Jablonska, J.; Tarczewski, R.; Trocka-Leszczynska, E. Changes in the Contemporary Public Space: Libraries. In Proceedings of the Advances in Human Factors, Sustainable Urban Planning and Infrastructure; Charytonowicz, J., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 228–238. [Google Scholar]

- Fabbri, K. Historic Climate in Heritage Building and Standard 15757: Proposal for a Common Nomenclature. Climate 2022, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).