1. Introduction

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a common and potentially life-threatening gastrointestinal condition characterized by sudden inflammation of the pancreas. It accounts for nearly 300,000 hospital admissions annually in the United States, making it one of the leading causes of gastrointestinal-related hospitalizations [

1]. The clinical presentation of AP varies widely, ranging from mild, self-limiting disease to severe cases associated with multiorgan failure and significant mortality [

2]. Several factors have been shown to influence disease severity, including advanced age, obesity, excessive alcohol intake, and the development of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) [

3].

Among the comorbidities associated with AP, diabetes mellitus has been extensively studied and linked to both an increased risk of developing the disease and poorer clinical outcomes [

2,

4]. Evidence suggests that individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus have a nearly threefold increased risk of developing AP compared to those without diabetes [

5]. This association is believed to be mediated by mechanisms such as metabolic dysregulation, chronic low-grade inflammation, and increased susceptibility to pancreatic injury.

Despite the well-documented relationship between overt diabetes and AP, there remains a paucity of data regarding the role of prediabetes in this context. Prediabetes represents a transitional state between normoglycemia and type 2 diabetes, marked by insulin resistance and impaired glucose metabolism. In 2021, an estimated 97.6 million U.S. adults—over one-third of the adult population—were living with prediabetes [

6]. This condition has been independently associated with systemic inflammation and organ dysfunction, raising concerns about its potential impact on diseases like AP. However, current literature lacks robust data on the prevalence and outcomes of AP in patients with prediabetes.

Given the high and growing prevalence of prediabetes, understanding its influence on AP outcomes is of clinical importance. Identifying whether prediabetic patients are at increased risk for complications such as prolonged hospitalization, elevated healthcare costs, or in-hospital mortality may help guide triage decisions, risk stratification, and early interventions for high-risk groups [

7].

The primary aim of this study is to evaluate the prevalence and clinical outcomes of hospitalized patients with AP and prediabetes using data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database. Specifically, we sought to compare in-hospital mortality, length of stay, and total hospitalization costs between patients with and without prediabetes. Additionally, we aimed to identify independent predictors of in-hospital mortality among this patient population.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

This retrospective cohort study utilized data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS), the largest publicly available all-payer inpatient healthcare database in the United States [

8]. The NIS contains de-identified patient information, including clinical and non-clinical data, collected using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes. Hospitalizations from the years 2016 to 2018 with a primary diagnosis of acute pancreatitis (AP) were identified using ICD-10-CM codes K85.0–K85.9. Patients were further classified into two cohorts: those with a secondary diagnosis of prediabetes (ICD-10-CM code R73.03), and those without this diagnosis.

To isolate the effect of prediabetes, all patients with a diagnosis of type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus were excluded from the analysis using ICD-10-CM codes E10.1–E10.9 and E11.1–E11.9. Additional variables including age, sex, race/ethnicity, and insurance type were collected to characterize the study population. Clinical comorbidities analyzed included severe sepsis with shock, liver cirrhosis (K74.6), morbid obesity (E66.01), acute kidney injury (N17), stroke (I63), gastrointestinal bleeding (K92.2), acute coronary syndrome (I24), and atrial fibrillation (I48.0, I48.1, I48.2).

2.2. Study Outcomes

The primary outcomes were in-hospital mortality, length of hospital stay, and total hospitalization cost among patients admitted with acute pancreatitis, comparing those with and without prediabetes. A secondary objective was to identify independent predictors of in-hospital mortality in this patient population.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were reported as means with standard deviations, and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. Group comparisons for continuous variables (e.g., length of stay, total cost) were conducted using independent t-tests. Associations between categorical variables (e.g., prediabetes status and in-hospital mortality) were analyzed using Chi-square tests. To evaluate independent predictors of in-hospital mortality, we performed multivariate logistic regression analysis. All statistical analyses were conducted using JMP Pro version 17 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), with a significance level set at α = 0.001 to account for multiple comparisons.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

This study did not require institutional review board approval since it utilized publicly accessible de-identified data from the NIS database. All patient information was anonymized in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA) guideline to ensure confidentiality.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

Between 2016 and 2018, a total of 193,617 patients were diagnosed with acute pancreatitis, with a mean age of 51.76 ± 17.61 years. Among these, 1,639 patients had prediabetes. The cohort of patients with prediabetes had a nearly equal distribution of males (50.81%) and females and was predominantly Caucasian (66.69%). Regarding insurance status, the most common types were private insurance (36.65%) and Medicare (34.33%). Additional demographic and clinical characteristics, including comorbidities, are summarized in

Table 1.

3.2. In-Hospital Mortality

There was no statistically significant difference in overall in-hospital mortality between patients with and without prediabetes (1.22% vs. 2.01%, respectively; p = 0.0225), as presented in

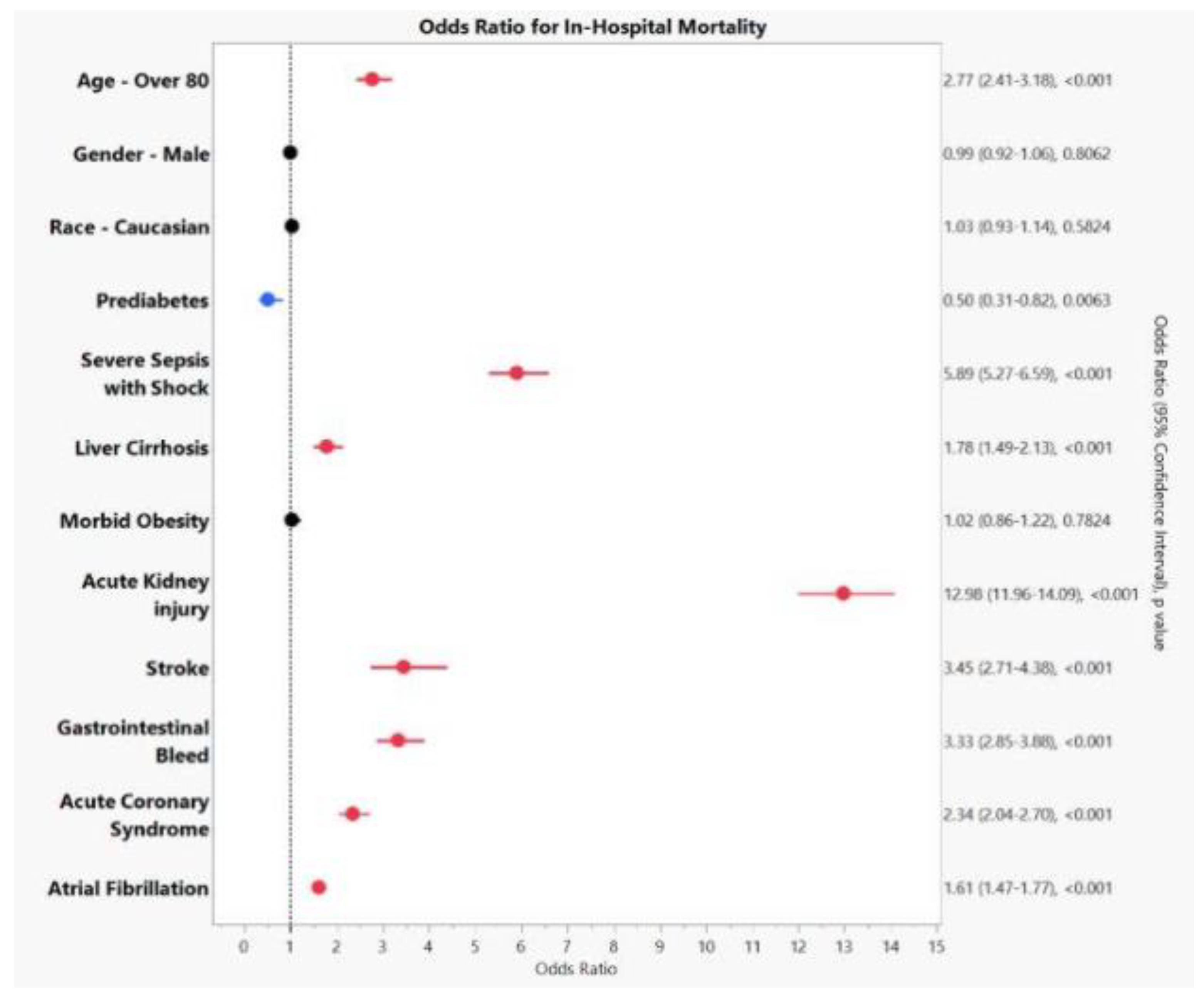

Table 2. However, certain comorbidities emerged as significant predictors of mortality in patients hospitalized with acute pancreatitis. Acute kidney injury was the strongest predictor, with an odds ratio (OR) of 16.07 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 5.68–45.43; p < 0.0001), followed by severe sepsis with shock (OR 5.89, 95% CI: 5.27–6.59; p < 0.001). Other factors significantly associated with increased mortality included stroke (OR 3.45, 95% CI: 2.71–4.38; p < 0.0001), gastrointestinal bleeding (OR 3.33, 95% CI: 2.85–3.88; p < 0.0001), acute coronary syndrome (OR 2.34, 95% CI: 2.04–2.70; p < 0.0001), atrial fibrillation (OR 1.61, 95% CI: 1.47–1.77; p < 0.0001), and liver cirrhosis (OR 1.78, 95% CI: 1.49–2.13; p < 0.001). Advanced age, particularly in individuals over 80 years old, was also significantly associated with mortality (OR 2.77, 95% CI: 2.41–3.18; p < 0.001). These findings are illustrated in

Figure 1.

3.3. Length of Stay and Total Hospitalization Costs

Patients without prediabetes had a slightly longer mean length of stay (LOS) compared to those with prediabetes, averaging 5.37 days versus 4.93 days, respectively (p = 0.0021). In terms of financial impact, the total hospitalization costs were higher among patients without prediabetes, with an average cost of

$57,106.83 compared to

$55,351.56 for those with prediabetes (p = 0.195). The differences in LOS and hospitalization costs are detailed in

Table 2.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the association between prediabetes and acute pancreatitis (AP) and its impact on length of stay and mortality risk, using the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database. Our findings suggest that prediabetes did not negatively impact in-hospital mortality, length of stay, or hospitalization costs compared to patients without prediabetes. This observation suggests that while prediabetes may have a less direct impact on mortality outcomes, it may still influence other aspects of hospital care. Interestingly, acute kidney injury (AKI), severe sepsis with shock, and other comorbidities emerged as significant predictors of mortality, highlighting critical factors that may play a larger role in determining patient outcomes.

While prediabetes is common among hospitalized patients with AP, the lack of association with mortality in our cohort could be attributed to multiple factors [

9]. Prediabetes represents an intermediate stage of impaired glucose metabolism, which may not impact the clinical course of AP in the same manner as an established diagnosis of diabetes [

10]. Previous research has suggested that individuals with prediabetes exhibit higher levels of C-reactive protein compared to those with normal glucose tolerance, indicating a heightened inflammatory response [

5]. However, this inflammation is often manageable in prediabetic patients with preserved pancreatic function. While prediabetes may not be directly linked to mortality in AP patients, it is important to note that approximately 40% of individuals with prediabetes progress to diabetes over 5–10 years [

9]. As prediabetes progresses to type 2 diabetes (T2D), the pancreas undergoes severe inflammatory damage characterized by increased release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, significantly compromising pancreatic function and increasing mortality in AP patients [

11]. These findings underscore the importance of early detection and management of prediabetes, particularly in high-risk individuals, as timely intervention may mitigate progression to diabetes and reduce the risk of adverse outcomes in AP [

9].

Despite the lack of association between prediabetes and mortality in our cohort, AKI and severe sepsis with shock emerged as strong predictors of mortality in patients with AP. This finding aligns with existing literature, which recognizes AKI as a serious complication in up to 70% of patients with severe acute pancreatitis [

12,

13,

14]. Several studies have reported that the development of AKI significantly worsens outcomes, with one study showing that 15% of patients with AKI required ICU admission [

15,

16]. Moreover, AKI has been found to double the mortality rate in patients with AP, emphasizing the critical nature of this condition [

12]. The pathophysiology behind this association appears to be multifactorial. The release of pancreatic amylase from the injured pancreas may compromise kidney function by impairing renal microcirculation [

17]. Additionally, complications such as hypoxia, hypovolemia, and abdominal compartment syndrome are believed to reduce renal perfusion pressure and worsen kidney function [

17]. Therefore, early recognition and management of AKI in AP patients is essential for improving prognosis.

Severe sepsis with shock also appeared as a strong predictor of mortality in AP patients. Existing studies support this observation, showing that sepsis amplifies the inflammatory cascade, leading to impaired tissue perfusion and multi-organ dysfunction [

18]. Prompt diagnosis and aggressive treatment of sepsis are crucial to prevent its progression to septic shock and subsequent multi-organ failure.

Furthermore, our study found that AP patients aged 80 and older were at significantly higher risk of mortality during hospitalization. Previous research attributes this elevated risk to the proinflammatory state commonly observed in older adults, increased cytokine production in elderly patients with sepsis, and the frequent presence of multiple comorbidities that contribute to higher mortality risk [

4,

11,

19,

20]. This finding underscores the vulnerability of older patients to more severe outcomes in AP.

This study has several strengths. The use of a large, nationally representative dataset (NIS) and a stringent p-value threshold (p < 0.001) enhanced the robustness of our findings. Given the relatively rare occurrence of AP, this extensive dataset was essential for providing a meaningful analysis of outcomes.

However, there are important limitations to consider. The study relied on ICD-10 coding, which may be subject to inaccuracies or misclassification. Additionally, the NIS database does not provide granular details on the severity of pancreatitis or specific management strategies used, both of which could influence outcomes. Lastly, due to its observational retrospective design, causal inferences cannot be made.

Future research should examine the long-term effects of prediabetes on the progression and recurrence of acute pancreatitis, as well as explore whether early glycemic control interventions can improve clinical outcomes in this patient population.

5. Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first nationwide, inpatient-based study to investigate the association between prediabetes and AP in predicting mortality. Our study suggests that prediabetes does not have a significant impact on in-hospital mortality, LOS, or hospitalization costs in patients with acute pancreatitis. While prediabetes may not serve as a significant predictor of in-hospital mortality, clinicians should remain vigilant when managing patients with prediabetes due to the potential for long-term complications, including the risk of progressing to T2D. Additionally, the presence of severe comorbidities, including AKI, severe sepsis with shock, and advanced age, remains crucial in determining patient prognosis. Further research is needed to evaluate in-hospital factors that determine the course of AP in prediabetic patients. Understanding these relationships will help clinicians better manage and triage patients with AP, particularly those with metabolic conditions that may predispose them to poorer outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M. and S.R.; formal analysis, R.M. and S.R.; investigation, T.D., N.S., S.R; writing—original draft preparation, T.D, N.S..; writing—review and editing, T.D., N.S., S.R.; visualization, S.R. and T.D.; supervision, N.R.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Ethics Committee of Brenau University waived the need for ethics approval and patient consent for the collection, analysis, and publication of the retrospectively obtained and anonymized data for this non-interventional study. .

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the use of publicly available, de-identified data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS), in accordance with institutional and national ethical guidelines.

Data Availability Statement

All data herein was derived directly from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database. The datasets used are available from the corresponding author upon request. .

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AP |

Acute Pancreatitis |

| NIS |

National Inpatient Sample |

| ICD-10 |

International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision |

| AKI |

Acute Kidney Injury |

| T2D |

Type 2 Diabetes |

| ICU |

Intensive Care Unit |

| LOS |

Length of Stay |

References

- Tenner S, Vege SS, Sheth SG, et al. American College of Gastroenterology Guidelines: Management of Acute Pancreatitis. Off J Am Coll Gastroenterol ACG. 2024;119(3):419. [CrossRef]

- Gapp J, Tariq A, Chandra S. Acute Pancreatitis. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Accessed July 24, 2024. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482468/.

- Ranson JH, Rifkind KM, Roses DF, Fink SD, Eng K, Spencer FC. Prognostic signs and the role of operative management in acute pancreatitis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1974;139(1):69-81.

- Hidalgo NJ, Pando E, Mata R, et al. Impact of comorbidities on hospital mortality in patients with acute pancreatitis: a population-based study of 110,021 patients. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023;23:81. [CrossRef]

- Increased Risk of Acute Pancreatitis and Biliary Disease Observed in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes | Diabetes Care | American Diabetes Association. Accessed July 24, 2024. https://diabetesjournals.org/care/article/32/5/834/29591/Increased-Risk-of-Acute-Pancreatitis-and-Biliary.

- Diabetes Statistics - NIDDK. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Accessed July 24, 2024. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-statistics/diabetes-statistics.

- Acute Pancreatitis - Gastrointestinal Disorders. Merck Manual Professional Edition. Accessed July 24, 2024. https://www.merckmanuals.com/en-ca/professional/gastrointestinal-disorders/pancreatitis/acute-pancreatitis.

- Khera R, Angraal S, Couch T, et al. Adherence to Methodological Standards in Research Using the National Inpatient Sample. JAMA. 2017;318(20):2011-2018. [CrossRef]

- Das SLM, Singh PP, Phillips ARJ, Murphy R, Windsor JA, Petrov MS. Newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus after acute pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2014;63(5):818-831. [CrossRef]

- Tabák AG, Herder C, Rathmann W, Brunner EJ, Kivimäki M. Prediabetes: A high-risk state for developing diabetes. Lancet. 2012;379(9833):2279-2290. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Gao J, Huang M, Fu X, Fu B. Risk Factors for Death in Patients with Severe Acute Pancreatitis in Guizhou Province, China. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2024;2024:8236616. [CrossRef]

- Nassar TI, Qunibi WY. AKI Associated with Acute Pancreatitis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol CJASN. 2019;14(7):1106-1115. [CrossRef]

- Wajda J, Dumnicka P, Maraj M, Ceranowicz P, Kuźniewski M, Kuśnierz-Cabala B. Potential Prognostic Markers of Acute Kidney Injury in the Early Phase of Acute Pancreatitis. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(15):3714. [CrossRef]

- Shi N, Sun GD, Ji YY, et al. Effects of acute kidney injury on acute pancreatitis patients’ survival rate in intensive care unit: A retrospective study. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27(38):6453-6464. [CrossRef]

- Comparison of impact on death and critical care admission of acute kidney injury between common medical and surgical diagnoses | PLOS One. Accessed March 26, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Effect of acute kidney injury on mortality and hospital stay in patient with severe acute pancreatitis - Zhou - 2015 - Nephrology - Wiley Online Library. Accessed March 26, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Petejova N, Martinek A. Acute kidney injury following acute pancreatitis: A review. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czechoslov. 2013;157(2):105-113. [CrossRef]

- Wilson PG, Manji M, Neoptolemos JP. Acute pancreatitis as a model of sepsis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;41 Suppl A:51-63. [CrossRef]

- Starr ME, Ueda J, Yamamoto S, Evers BM, Saito H. The Effects of Aging on Pulmonary Oxidative Damage, Protein Nitration and Extracellular Superoxide Dismutase Down-Regulation During Systemic Inflammation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50(2):371-380. [CrossRef]

- Márta K, Lazarescu AM, Farkas N, et al. Aging and Comorbidities in Acute Pancreatitis I: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review Based on 194,702 Patients. Front Physiol. 2019;10:328. [CrossRef]

- Ford ES, Zhao G, Li C. Pre-Diabetes and the Risk for Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(13):1310-1317. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).