1. Introduction

Ferroptosis is characterized by an iron-dependent accumulation of lethal reactive oxygen species (ROS) and lipid radicals. The most frequently occurring free radicals and reactive molecules in biological systems are derived from oxygen (ROS) and nitrogen (Reactive Nitrogen Species, RNS). ROS or RNS are formed during electron transfer reactions, by losing or accepting electron(s) [

1,

2]. While low levels of ROS are important for cellular proliferation, differentiation, migration, apoptosis, and necrosis, excessive ROS causes oxidative stress, inducing ROS-mediated damage to cellular biomolecules including DNA, proteins, and membranes [

3,

4]. Oxidative stress is characterized by a shift in equilibrium between the formation and elimination of free radicals. Oxidative stress is involved in various aspects of human pathogenesis in chronic diseases, aging and cancers [

5]. Human normal as well as tumor cells have an enhanced antioxidant system to remove/detoxify ROS formed. They include superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidases (GPXs), as well as reduced glutathione [

2] to protect cells from ROS-induced toxicity [

6]. Excess ROS and lipid ROS formation causes damage to cellular membranes inducing ferroptosis, a form of cell death which is morphologically, biochemically, and genetically distinct from apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagy [

7,

8,

9]. As ferroptosis is distinct from other forms of cell death it has been suggested to play an important role in cancer therapy.

Glutathione peroxidase 4 (GSH/GPX4) and system Xc-, are two major signaling pathways which are known to play pivotal roles in ferroptosis [

7]. System Xc- are the family of heterodimeric amino acid transporters and SLC7A11 functions to exchange L-cystine and L-glutamate [

10]. Erastin, a ferroptosis inducer, inhibits the function of system Xc- and depletes glutathione (GSH), resulting in inhibition of GPX4 and the accumulation of ROS and lipid peroxides which in turn causes ferroptosis.

Ferroptosis has recently been suggested to play a significant role in toxicology due to its unique cell death mechanism that is driven by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation. This mechanism has become extremely relevant to toxicology because exposure to certain toxins (e.g., heavy metals, environmental pollutants, and industrial chemicals) can intensify oxidative stress, leading to ferroptotic cell damage (and death) in organs like the liver, kidneys, and lungs [

11]. Many drugs, especially chemotherapy agents, have been shown to increase ROS formation and disrupt cellular iron metabolism, causing ferroptosis [

12]. Thus, understanding the mechanisms and pathways involved in ferroptosis will help in predicting, preventing, or treating drug-induced tissue damage, especially in high-risk organs.

Ferroptosis has been implicated in neurotoxicity due to its role in oxidative damage and iron accumulation, which are common in neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s [

13]. Since some neurotoxic substances can elevate iron or lipid peroxidation in the brain, insights into ferroptosis could lead to new protective strategies for managing neurotoxin exposure and associated diseases.

The liver, as a central organ in detoxification, is highly susceptible to ferroptosis [

14]. This is especially relevant for drugs that induce iron overload and/or oxidative stress, triggering ferroptosis and causing hepatotoxicity and liver fibrosis.

Exposure to environmental toxins, such as heavy metals (e.g., arsenic, cadmium) and other industrial pollutants, can influence cellular iron metabolism or redox balance, increasing the risk of ferroptosis in exposed tissues [

15,

16]. Further studies on ferroptosis can provide strategies to mitigate these toxic effects and improve public health outcomes. By targeting ferroptosis pathways, researchers can significantly reduce toxicity and prevent cell death from toxic xenobiotics or drugs. Ferroptosis inhibitors may then be utilized to mitigate damage in ferroptosis-sensitive tissues/organs during exposures or poisonings from environmental pollutants, providing a new avenue for therapeutic intervention in toxicology.

2. Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)

PFAS are a group of persistent chemicals that are widely present in environment due to their extensive use as protective coatings for carpets and clothing, water repellents, paper coatings, and surfactants [

17,

18,

19]. PFAS are now found in water and food, as well as in indoor air settings, leading to significant exposures [

18]. Unfortunately, efforts to control and decrease the use of PFAS have not been very successful as they are still detected in humans, animals, and water due to both their extensive world-wide application and lack of biodegradability. Air pollution and cigarette smoke have been shown to contain high concentrations of PFOS, a key member of PFAS family. PFAS causes oxidative stress [

20,

21], mitochondrial dysfunction [

22], and inhibition of gap junction intercellular communication [

23], resulting in serious human health problems including endocrine disruptions, liver damage, kidney cancer, obesity, hypertension, and immunotoxicity [

24].

In vitro and

in vivo experiments, as well as population studies, have suggested that exposure to PFAS is associated with increased oxidative stress. PFAS generate reactive ROS in human hepatocytes, inducing oxidative stress and causing DNA damage with genotoxic and cytotoxic potential [

25]. In addition, PFAS exposures have been shown to enhance oxidative stress in kidney, leading to disruptive effects on the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) and its downstream functions [

21]. Several studies in humans have shown that serum PFAS concentrations are strongly associated with biomarkers of oxidative and nitrative stress as PAFS increase the levels of both 8-nitroguanine and 8- hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) [

26]. Furthermore, in a randomized control trial in senior Koreans with elevated serum levels of perfluorododecanoic acid (PFDoDA), and PFOS blood concentrations showed higher levels of malondialdehyde and 8-OHdG in urine [

27].

PFAS is known to accumulate in the kidneys and research indicates a strong link between exposure to PFAS with kidney toxicity, showing that PFAS can negatively impact kidney function and potentially contribute to the development of chronic kidney disease. Further studies have reported that PFAS exposure induces oxidative stress in the kidney, causing lipid peroxidation and DNA damage, increased production of mitochondrial transport chain proteins, decreased cell proliferation, and apoptosis [

21,

28,

29,

30]. Multiple pathways have been implicated in PFOS exposure to cause renal damage, including dysregulation of PPARa and PPARg, key nuclear receptor hormones. These are highly expressed in the proximal renal tubule and involved in lipid metabolism, lipogenesis, glucose homeostasis, and cell growth and differentiation [

21]. Recently, the use of N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and taurine—both known inhibitors of oxidative stress—has been found to reduce complications in diabetic and hypertensive patients with chronic kidney disease Recently, the use of N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and taurine—both known inhibitors of oxidative stress—has been found to reduce complications in diabetic and hypertensive patients with chronic kidney disease [

31].

PFAS can cross the blood-brain barrier and accumulate in the brain which negatively impacts brain function and disrupt neurotransmitter systems, potentially leading to cognitive impairments and neurodevelopmental issues [

32,

33]. This is particularly important when exposure occurs during critical developmental stages since PFAS can cross disrupt various mechanisms within the brain, including calcium homeostasis and mitochondrial function and alterations in neurotransmitters of neurons [

34].

PFAS exposure has been shown tom disrupt the cellular antioxidant balance by decreasing the activity of GPX4, a key enzyme responsible for preventing lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. Studies have found elevated intracellular iron levels, increased lipid peroxidation, and altered expression of ferroptosis-related proteins like ACSL4 (acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4) when cells are exposed to PFAS.

2.1. Heavy Metals

Heavy metals (e.g., arsenic, cadmium, and mercury) are found in the Earth’s crust with varying concentrations and are not easily detoxified into less toxic compounds through metabolic processes. Thus, they persist for a long time and are taken up by plants, leading to accumulation in various animals and humans at high toxic levels, causing harmful impacts on both the environment and human health [

35,

36].

Many heavy metals can interfere with the synthesis or function of glutathione, a crucial antioxidant that protects against lipid peroxidation, thereby promoting ferroptosis. Copper has been reported to inhibit GPX4 activity, leading to its degradation through autophagy and promoting ferroptosis [

37]. GPX4 is the key enzyme for the removal of cellular lipid peroxide formed, inhibiting ferroptosis. Heavy metals disrupt mitochondrial function, leading to increased ROS production and further promoting ferroptosis [

15]. Exposure to heavy metals, especially lead and mercury, are linked to neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's. Methylmercury (CH

3-Hg) has been shown to react with GSH, generate ROS and cause oxidative stress Ferroptosis has been suggested as a potential mechanism of neuronal death [

13,

16]. Combination of metals like iron with carbon tetrachloride can cause liver damage through ferroptosis [

38].

Heavy metals have been reported to disrupt cellular redox homeostasis and contribute to iron dysregulation, promoting ferroptosis [

39]. Cadmium exposure can induce iron accumulation in cells, enhancing the production of ROS and lipid peroxidation, inducing ferroptosis [

40]. Thus, ferroptosis in response to heavy metal exposure primarily impacts organs with high iron content or metabolic activity, such as the liver and kidneys [

14,

38]

. Exposure to arsenic can cause ferroptosis in liver cells, contributing to arsenic-induced liver injury and increasing the risk of hepatotoxicity and fibrosis [

41].

2.2. Industrial Pollutants and Airborne Particulates

Particulate matter (PM) is the principal component of indoor and outdoor air pollution. PM includes a range of particle sizes, such as coarse, fine, and ultrafine particles. Industrial pollutants, especially airborne particulate matter from sources like vehicle exhaust and industrial emissions, contain metals and organic compounds [

42,

43,

44]. Particles that are <100 nm in diameter are defined as ultrafine particles (UFPs). Chronic exposure to air pollutants that induce ferroptosis can damage lung tissue, leading to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and lung cancer [

45]. When inhaled, these particles can produce oxidative stress in lung cells, causing ferroptosis and leading to respiratory diseases. Inhalation of PM exacerbates respiratory symptoms in patients with chronic airway disease, but the mechanism for this response is not clear currently.

2.3. Pesticides

High lipophilic pesticides are known to integrate into cell membranes and initiate lipid peroxidation which in the presence of iron lead to ferroptosis [

46]. Paraquat, a pesticide and a ROS generator [

47,

48], has been shown to induce ferroptosis in neural and other cell types, leading to neurodegenerative conditions like Parkinson’s disease [

49,

50]. Ferroptosis induced by pesticides exposure poses significant neurotoxic risks, as brain cells are highly susceptible to oxidative damage and lipid peroxidation, elucidating why long-term exposure to certain pesticides has been associated with increased risks of neurological disorders [

51,

52].

Imidacloprid (IMI) is among the common neonicotinoid insecticides used in agriculture worldwide, posing a potential toxic threat to non-target animals and humans. Numerous studies have shown that ferroptosis is involved in the pathophysiological progression of renal diseases [

53,

54]. Chlorpyrifos is an organophosphate pesticide that can trigger ferroptosis, causing liver toxicity [

55]. Interestingly, Vitamin E (a strong antioxidant) supplementation has been reported to help reverse the effects of ferroptosis caused by chlorpyrifos [

56]. Various other pesticides e.g., Acetochlor, an herbicide that causes skin irritation, cancer, and developmental issues, has been reported to trigger ferroptosis [

57].

3. Ferroptosis Combined with Apoptosis and Necrosis

Exposure to environmental pollutants can also cause other forms of cell death such as apoptosis and necrosis [

29,

58,

59]. Ferroptosis can act synergistically with apoptosis, significantly enhancing tissue damage. Thus, simultaneous exposure to multiple pollutants, may increase ferroptotic damage, especially when both iron-dependent mechanisms and lipid peroxidation are enhanced. Cells exposed to chronic low doses of environmental pollutants may initially activate protective mechanisms (like antioxidant defenses) to counteract ferroptosis. However, prolonged exposure can overwhelm these defenses, tipping the balance toward ferroptosis, which could explain why chronic, low-level pollutant exposure is linked to long-term health risks.

4. Biomarkers of Ferroptosis

Biomarkers are important tools for early detection of tissue damage in any biological process, in the treatment of cancers by chemotherapy or exposure to environmental toxins. Thus, the identification of biomarkers of ferroptosis can significantly enhance the field of toxicology by providing tools to monitor, predict, and potentially mitigate cell death related to iron-dependent lipid peroxidation. Furthermore, biomarkers of ferroptosis can be advantageous in toxicology as environmental toxins (drugs) induce ferroptosis in healthy organs like the liver, kidneys, heart and brain, leading to toxic side effects. Biomarkers of ferroptosis can then help assess which organs are at risk of damage, allowing preemptive measures to protect these tissues.

Certain chemicals and pollutants, like heavy metals and industrial pollutants, directly or indirectly trigger ferroptosis. By measuring biomarkers of ferroptosis in animal models or cell cultures exposed to these substances, researchers can identify chemicals that pose significant health risks and implement safer guidelines for exposure levels. Biomarkers also serve as early indicators of ferroptosis-related damage in non-cancerous tissues. For example, if elevated levels of lipid peroxidation markers are detected in the blood following chemotherapy or toxins exposure, it could indicate liver or kidney toxicity, allowing clinicians to modify the treatment regimen to mitigate damage. When ferroptosis biomarkers suggest unwanted toxicity in healthy cells, ferroptosis inhibitors like ferrostatin-1, liproxstatin-1 or vitamin E could be utilized to mitigate tissue damage. Thus, biomarkers may be helpful to guide when and where these inhibitors are needed to protect healthy organs or cells. Several biomarkers of oxidative stress are biomarkers of ferroptosis such as glutathione depletion, GPX4 (glutathione peroxidase 4) inhibition, or formation of lipid peroxidation products. We have recently found that opthalamate levels were highly elevated during tumor cells undergoing ferroptosis [

60]. Opthalamate levels have been shown to be elevated in during oxidative stress caused by the depletion of glutathione in liver [

61]. Additionally, several genes, known markers of oxidative stress (e.g. CHAC1 and heme oxygenase), have been shown to be elevated during ferroptosis [

62,

63,

64].

Several specific biomarkers of ferroptosis are particularly valuable in toxicity research. Lipid peroxidation products (e.g., MDA, 4-HNE) are good indicators of lipid peroxidation and oxidative damage that can indicate ongoing ferroptosis. Iron dysregulation is another key feature of ferroptosis and measuring intracellular iron levels or proteins like ferritin and transferrin can indicate ferroptosis risk. Glutathione depletion and inhibition of GPX4, an enzyme that prevents lipid peroxidation, are central to ferroptosis. Measuring these markers can help detect cells in the process of ferroptosis. Additionally, ferroptosis depends on cysteine uptake via the cystine/glutamate antiporter (system Xc−) to synthesize glutathione. Reduced system Xc− activity can indicate a heightened risk of ferroptosis.

Development of easy-to-use biomarker probes can then assess the degree of cellular stress and risk of ferroptosis from exposure to environmental toxins, drugs, or pollutants. By understanding how these exposures lead to ferroptosis, researchers can better understand the potential for organ damage and disease. By tracking ferroptosis biomarkers, toxicologists can measure cumulative oxidative stress and iron overload in tissues exposed to harmful substances over time. These data can guide interventions, such as antioxidant treatments or iron chelation therapies, to reduce the likelihood of ferroptosis-related damage in at-risk populations. Biomarkers can help detect the early stages of ferroptosis-related toxicity before clinical symptoms appear, offering a window for intervention. For example, in cases of heavy metal exposure, ferroptosis biomarkers could signal the need for treatments that counter oxidative stress or iron accumulation, preventing progression to severe tissue damage. In both chemotherapy and toxicology, understanding the presence and levels of ferroptosis biomarkers can inform the design of drugs aimed at modulating ferroptosis. In toxicology, they can assist in creating protective drugs that inhibit ferroptosis in response to environmental toxins.

For diseases associated with ferroptosis (e.g., neurodegenerative diseases, liver disease), biomarkers can guide therapeutic interventions that either promote or inhibit ferroptosis as needed. For example, in neurodegeneration, where excessive ferroptosis can be damaging, biomarkers could be used to develop and test drugs that protect neurons from ferroptotic cell death.

5. Conclusions and Future Developments

While significant progress is being made in the understanding of environmental pollutant- induced toxicity to humans, there is still a lot of research needed to further our understanding on the long-term effects of these pollutants. Furthermore, we do not know what effects of combinations of these pollutants have on human health, e.g. effects of PFAS with low doses of heavy metal or particulates combined with heavy metals.

There is a number of steps that must be taken in order to be more effective in discovering biomarkers and utilizing these biomarkers for effective interventions to help support long term effects on humans. One way is to combine high throughput screening and developing cost-effective assays of non-invasive biomarkers. In addition, implementing cost-effective validation strategies and c ollaborating across fields, we can conduct ferroptosis biomarker discovery in a budget-conscious manner. These approaches should help in streamlining processes, prioritize high-impact biomarkers, and reduce redundancy, paving the way for affordable, scalable research in both toxicology and chemotherapy.

There is a strong need for proper models to identify biomarkers of ferroptosis. Currently, the model for ferroptosis, human or animal cell lines are utilized to screen for ferroptosis biomarkers in response to toxicants which are more cost-effective than

in vivo animal models. Well-characterized cell lines sensitive to ferroptosis can provide relevant insights at a fraction of cost. However, it has been found that such models (2D) differ from modifications in mice or humans in the process of drug screening and or discovery of biomarkers [

65]. Using CRISPR/Cas9 or RNAi to knock down or knock out ferroptosis-related genes in cell models can help rapidly identify potential biomarkers without the need for more expensive or labor-intensive techniques.

With the recent advancement in 3D culture technology, normal (non-tumor), tumor organoid culture technology could be utilized which may be beneficial for discovery of biomarkers to prevent/mitigate diseases. Compared with traditional 2D culture and tumor tissue xenotransplantation, organoid models have a significantly higher success rate [

65]. Other models have also been recently proposed to evaluate biomarkers of ferroptosis [

66,

67]. If animal models are necessary, zebrafish may be the most cost-effective alternative for studying toxicology and ferroptosis, given their low maintenance costs, rapid development, and high genetic homology with humans for relevant pathways [

68].

6. Ferroptosis Inhibitors in Therapeutic and Preventive Measures

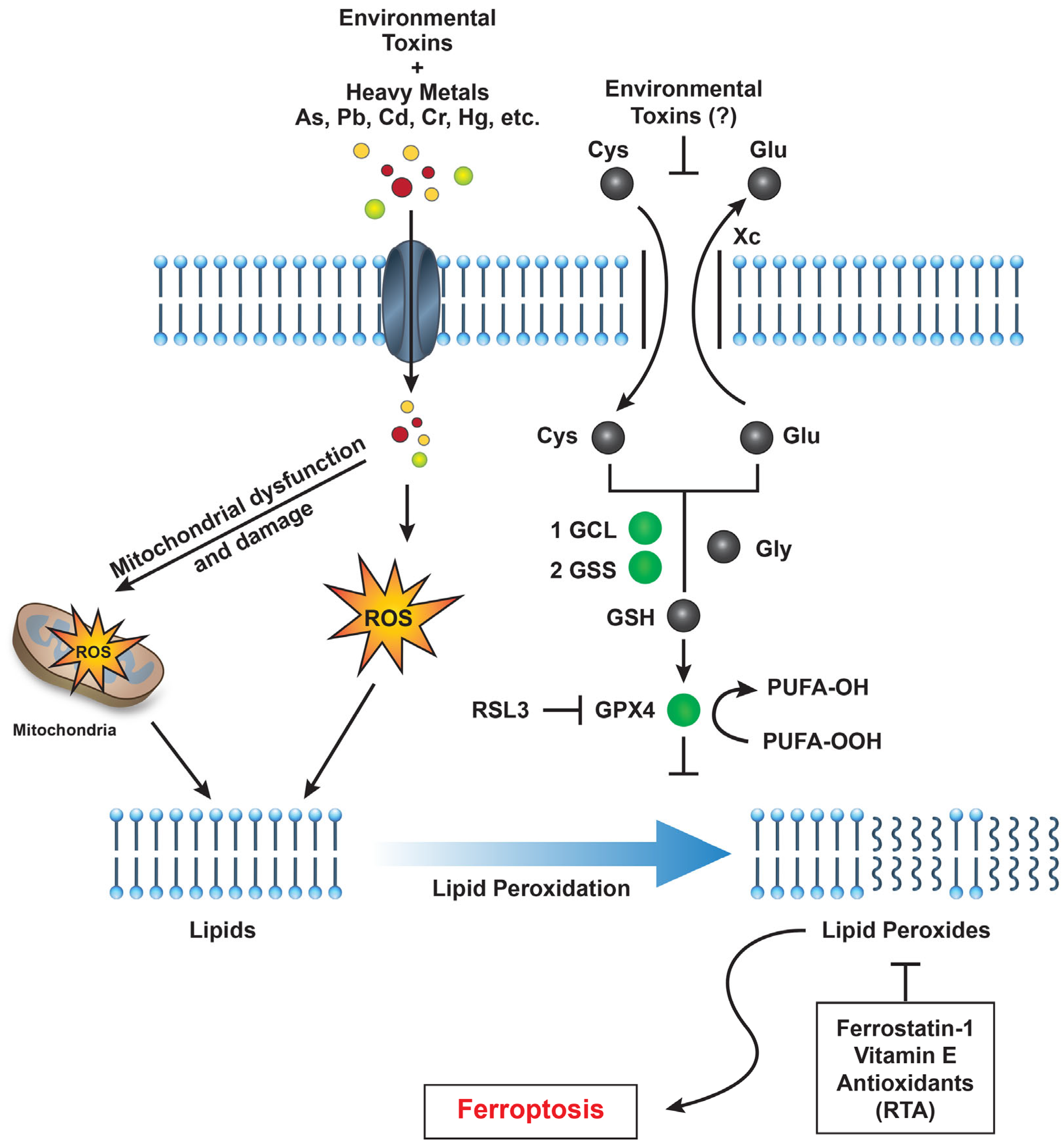

Research into ferroptosis has highlighted potential therapeutic strategies, including ferroptosis inhibitors like ferrostatin-1 and liproxstatin-1, which can prevent lipid peroxidation (Figure 1). These inhibitors might be used to mitigate the effects of pollutant-induced ferroptosis in high-risk populations. Supplementing with antioxidants (e.g., vitamin E, selenium) may help prevent lipid peroxidation, offering a potential preventive measure against ferroptosis for individuals exposed to environmental pollutants. Additionally, monitoring iron intake and iron levels could reduce susceptibility to ferroptosis in populations at risk.

7.Summary

Ferroptosis’s link to environmental pollutants has provided new understanding how toxicants can cause organ damage, neurotoxicity, and chronic disease. This cell death pathway highlights the importance of iron metabolism and lipid peroxidation in toxicology, as it offers potential therapeutic targets to reduce the impact of pollutants. Ferroptosis serves as a critical nexus between environmental exposures and cellular dysfunction. Recognizing the role of environmental pollutants in triggering ferroptosis not only enhances our understanding of disease pathogenesis but also guides the development of targeted interventions to protect public health. With increasing industrialization and repeated exposures to these toxicants and particulate matters, it is more critical to understand, evaluate and find correct solutions if we are to maintain a healthy lifestyle today and for future generations.

Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 (NRF2), a transcription factor, plays a critical role in regulating cellular defenses against oxidative stress induced by environmental toxins such as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and heavy metals [

35]. NRF2 is central to maintaining cellular homeostasis by modulating antioxidant responses, detoxification pathways, metabolism, and inflammation. It regulates various antioxidant genes, including the cystine/glutamate antiporter (system Xc⁻), specifically SLC7A11, which facilitates cystine uptake for glutathione (GSH) synthesis [

69]. Since glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) requires GSH to detoxify lipid peroxides and prevent ferroptosis [

70], NRF2 activation is generally associated with ferroptosis inhibition [

71]. However, the role of NRF2 in ferroptosis is context-dependent and complex. In some cases, NRF2 upregulation promotes ferroptosis. For instance, in lung cancer cells, elevated NRF2 levels have been shown to sensitize tumor cells to ferroptosis by increasing multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 (MRP1) expression. Additionally, heightened NRF2 activity induces heme oxygenase-1 (HMOX1), leading to the production of biliverdin and the release of redox-active iron, which triggers lipid peroxidation in neuroblastoma and fibrosarcoma cells. Moreover, NRF2-driven upregulation of ABCC1 (MRP1) can deplete intracellular GSH, further contributing to ferroptosis in tumor cells [

72].

While the specific effects of PFAS on system Xc⁻ remain unclear, certain heavy metals are known to inhibit SLC7A11 and induce ferroptosis. PFAS are known inducers of oxidative stress and may potentially impair GSH synthesis by inhibiting SLC7A11, thereby affecting system Xc⁻ activity. A proposed pathway for environmental pollutant-induced ferroptosis is shown in

Figure 1.

Funding

This research was supported by the intramural research program (Grant number ZIA E505013922 and CARCI-HEI#) of the National Institute of Environmental Sciences, NIH. Statements contained herein do not necessarily represent the statements of, opinions or conclusions of NIEHS, NIH, or the US government.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank Erik Tokar and Alex Bruce Merrick for their critical evaluation of the manuscript.

References

- Sinha, B.K. Roles of free radicals in the toxicity of environmental pollutants and toxicants. Journal of Clinical Toxicology 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B. Commentary for "Oxygen free radicals and iron in relation to biology and medicine: Some problems and concepts". Arch Biochem Biophys 2022, 718, 109151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, B.K.; Mimnaugh, E.G. Free radicals and anticancer drug resistance: oxygen free radicals in the mechanisms of drug cytotoxicity and resistance by certain tumors. Free Radic Biol Med 1990, 8, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liguori, I.; Russo, G.; Curcio, F.; Bulli, G.; Aran, L.; Della-Morte, D.; Gargiulo, G.; Testa, G.; Cacciatore, F.; Bonaduce, D.; et al. Oxidative stress, aging, and diseases. Clin Interv Aging 2018, 13, 757–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valko, M.; Leibfritz, D.; Moncol, J.; Cronin, M.T.; Mazur, M.; Telser, J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2007, 39, 44–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkel, T.; Holbrook, N.J. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature 2000, 408, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.J.; Lemberg, K.M.; Lamprecht, M.R.; Skouta, R.; Zaitsev, E.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Patel, D.N.; Bauer, A.J.; Cantley, A.M.; Yang, W.S.; et al. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, B.R.; Friedmann Angeli, J.P.; Bayir, H.; Bush, A.I.; Conrad, M.; Dixon, S.J.; Fulda, S.; Gascon, S.; Hatzios, S.K.; Kagan, V.E.; et al. Ferroptosis: A Regulated Cell Death Nexus Linking Metabolism, Redox Biology, and Disease. Cell 2017, 171, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cao, F.; Yin, H.L.; Huang, Z.J.; Lin, Z.T.; Mao, N.; Sun, B.; Wang, G. Ferroptosis: past, present and future. Cell Death Dis 2020, 11, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.J.; Patel, D.N.; Welsch, M.; Skouta, R.; Lee, E.D.; Hayano, M.; Thomas, A.G.; Gleason, C.E.; Tatonetti, N.P.; Slusher, B.S.; et al. Pharmacological inhibition of cystine-glutamate exchange induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis. Elife 2014, 3, e02523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschner, M.; Skalny, A.V.; Martins, A.C.; Sinitskii, A.I.; Farina, M.; Lu, R.; Barbosa, F., Jr.; Gluhcheva, Y.G.; Santamaria, A.; Tinkov, A.A. Ferroptosis as a mechanism of non-ferrous metal toxicity. Arch Toxicol 2022, 96, 2391–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.; Zhao, B.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, Y.; Lv, H.; AlQudsy, L.H.H.; Shang, P. Ferroptosis, a novel pharmacological mechanism of anti-cancer drugs. Cancer Lett 2020, 483, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichert, C.O.; de Freitas, F.A.; Sampaio-Silva, J.; Rokita-Rosa, L.; Barros, P.L.; Levy, D.; Bydlowski, S.P. Ferroptosis Mechanisms Involved in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleman, C.; Francque, S.; Berghe, T.V. Emerging role of ferroptosis in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: revisiting hepatic lipid peroxidation. EBioMedicine 2024, 102, 105088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, K.; Sharma, A. Understanding the mechanistic roles of environmental heavy metal stressors in regulating ferroptosis: adding new paradigms to the links with diseases. Apoptosis 2023, 28, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Cai, X.; Li, R. Ferroptosis Induced by Pollutants: An Emerging Mechanism in Environmental Toxicology. Environ Sci Technol 2024, 58, 2166–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podder, A.; Sadmani, A.; Reinhart, D.; Chang, N.B.; Goel, R. Per and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) as a contaminant of emerging concern in surface water: A transboundary review of their occurrences and toxicity effects. J Hazard Mater 2021, 419, 126361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunderland, E.M.; Hu, X.C.; Dassuncao, C.; Tokranov, A.K.; Wagner, C.C.; Allen, J.G. A review of the pathways of human exposure to poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) and present understanding of health effects. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2019, 29, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ma, Y.; Cheng, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, W. Association between perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl internal exposure and serum alpha-Klotho levels in middle-old aged participants. Front Public Health 2023, 11, 1136454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Sarkar, D.; Biswas, J.K.; Datta, R. Biodegradation of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS): A review. Bioresour Technol 2022, 344, 126223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanifer, J.W.; Stapleton, H.M.; Souma, T.; Wittmer, A.; Zhao, X.; Boulware, L.E. Perfluorinated Chemicals as Emerging Environmental Threats to Kidney Health: A Scoping Review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2018, 13, 1479–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Arellano, P.; Lopez-Arellano, K.; Luna, J.; Flores, D.; Jimenez-Salazar, J.; Gavia, G.; Teteltitla, M.; Rodriguez, J.J.; Dominguez, A.; Casas, E.; et al. Perfluorooctanoic acid disrupts gap junction intercellular communication and induces reactive oxygen species formation and apoptosis in mouse ovaries. Environ Toxicol 2019, 34, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, H.; Lin, C.; Mao, Y.; Rao, J.; Lou, Y.; Yang, X.; Xu, X.; Jin, F. Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) inhibits the gap junction intercellular communication and induces apoptosis in human ovarian granulosa cells. Reprod Toxicol 2020, 98, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evich, M.G.; Davis, M.J.B.; McCord, J.P.; Acrey, B.; Awkerman, J.A.; Knappe, D.R.U.; Lindstrom, A.B.; Speth, T.F.; Tebes-Stevens, C.; Strynar, M.J.; et al. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the environment. Science 2022, 375, eabg9065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielsoe, M.; Long, M.; Ghisari, M.; Bonefeld-Jorgensen, E.C. Perfluoroalkylated substances (PFAS) affect oxidative stress biomarkers in vitro. Chemosphere 2015, 129, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.Y.; Lee, H.L.; Hwang, Y.T.; Su, T.C. The association between total serum isomers of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, lipid profiles, and the DNA oxidative/nitrative stress biomarkers in middle-aged Taiwanese adults. Environ Res 2020, 182, 109064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Park, H.Y.; Jeon, J.D.; Kho, Y.; Kim, S.K.; Park, M.S.; Hong, Y.C. The modifying effect of vitamin C on the association between perfluorinated compounds and insulin resistance in the Korean elderly: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled crossover trial. Eur J Nutr 2016, 55, 1011–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arukwe, A.; Mortensen, A.S. Lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress responses of salmon fed a diet containing perfluorooctane sulfonic- or perfluorooctane carboxylic acids. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol 2011, 154, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.L.; Lin, C.Y.; Chou, H.C.; Chang, C.C.; Lo, H.Y.; Juan, S.H. Perfluorooctanesulfonate Mediates Renal Tubular Cell Apoptosis through PPARgamma Inactivation. PloS one 2016, 11, e0155190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorrochategui, E.; Lacorte, S.; Tauler, R.; Martin, F.L. Perfluoroalkylated Substance Effects in Xenopus laevis A6 Kidney Epithelial Cells Determined by ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy and Chemometric Analysis. Chemical research in toxicology 2016, 29, 924–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, V.e.a. Effectivemess of N-acetylcysteine and Taurine in reducing microalbuminuria in diabetic and hypertensive pateints with chronic kidney diseases: A retrospective, observational study. Wolrd Journal of Pharmeceutical Science and Research 2025, 4, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown-Leung, J.M.; Cannon, J.R. Neurotransmission Targets of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substance Neurotoxicity: Mechanisms and Potential Implications for Adverse Neurological Outcomes. Chemical research in toxicology 2022, 35, 1312–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharal, B.; Ruchitha, C.; Kumar, P.; Pandey, R.; Rachamalla, M.; Niyogi, S.; Naidu, R.; Kaundal, R.K. Neurotoxicity of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances: Evidence and future directions. Sci Total Environ 2024, 955, 176941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starnes, H.M.; Rock, K.D.; Jackson, T.W.; Belcher, S.M. A Critical Review and Meta-Analysis of Impacts of Per- and Polyfluorinated Substances on the Brain and Behavior. Front Toxicol 2022, 4, 881584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Goncalves, F.M.; Abiko, Y.; Li, H.; Kumagai, Y.; Aschner, M. Redox toxicology of environmental chemicals causing oxidative stress. Redox Biol 2020, 34, 101475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, S.; Ali, A.; Kour, N.; Bornhorst, J.; AlHarbi, K.; Rinklebe, J.; Abd El Moneim, D.; Ahmad, P.; Chung, Y.S. Heavy Metal Induced Oxidative Stress Mitigation and ROS Scavenging in Plants. Plants (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Q.; Yan, D.; Chen, X.; Li, X.; Kang, R.; Klionsky, D.J.; Kroemer, G.; Chen, X.; Tang, D.; Liu, J. Copper-dependent autophagic degradation of GPX4 drives ferroptosis. Autophagy 2023, 19, 1982–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Yu, Z.; Zhou, L.; Wang, X.; Hui, Y.; Mao, L.; Fan, X.; Wang, B.; Zhao, X.; Sun, C. Regulating Nrf2-GPx4 axis by bicyclol can prevent ferroptosis in carbon tetrachloride-induced acute liver injury in mice. Cell Death Discov 2022, 8, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samet, J.M.; Wages, P.A. Oxidative Stress from Environmental Exposures. Curr Opin Toxicol 2018, 7, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anetor, J.I. Rising environmental cadmium levels in developing countries: threat to genome stability and health. Niger J Physiol Sci 2012, 27, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N.; Paul, S.; Chatterjee, D.; Banerjee, N.; Majumder, N.S.; Sarma, N.; Sau, T.J.; Basu, S.; Banerjee, S.; Majumder, P.; et al. Arsenic exposure through drinking water increases the risk of liver and cardiovascular diseases in the population of West Bengal, India. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormack, M.C.; Breysse, P.N.; Hansel, N.N.; Matsui, E.C.; Tonorezos, E.S.; Curtin-Brosnan, J.; Williams, D.L.; Buckley, T.J.; Eggleston, P.A.; Diette, G.B. Common household activities are associated with elevated particulate matter concentrations in bedrooms of inner-city Baltimore pre-school children. Environ Res 2008, 106, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surawski, N.C.; Miljevic, B.; Ayoko, G.A.; Elbagir, S.; Stevanovic, S.; Fairfull-Smith, K.E.; Bottle, S.E.; Ristovski, Z.D. Physicochemical characterization of particulate emissions from a compression ignition engine: the influence of biodiesel feedstock. Environ Sci Technol 2011, 45, 10337–10343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leikauf, G.D.; Kim, S.H.; Jang, A.S. Mechanisms of ultrafine particle-induced respiratory health effects. Exp Mol Med 2020, 52, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doiron, D.; de Hoogh, K.; Probst-Hensch, N.; Fortier, I.; Cai, Y.; De Matteis, S.; Hansell, A.L. Air pollution, lung function and COPD: results from the population-based UK Biobank study. Eur Respir J 2019, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Huang, R.; Sun, F.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Q. NADPH oxidase regulates paraquat and maneb-induced dopaminergic neurodegeneration through ferroptosis. Toxicology 2019, 417, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Singh, D.; Kumar, V.; Chauhan, A.K.; Singh, S.; Ahmad, I.; Pandey, H.P.; Singh, C. NADPH oxidase mediated maneb- and paraquat-induced oxidative stress in rat polymorphs: Crosstalk with mitochondrial dysfunction. Pestic Biochem Physiol 2015, 123, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A.R.; Zielonka, J.; Kalyanaraman, B.; Hartley, R.C.; Murphy, M.P.; Avadhani, N.G. Mitochondria-targeted paraquat and metformin mediate ROS production to induce multiple pathways of retrograde signaling: A dose-dependent phenomenon. Redox Biol 2020, 36, 101606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Xie, J.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Thirupathi, A.; Zhang, J.; Yu, P.; Gao, G.; Chang, Y.; Shi, Z. Ferritinophagy-Mediated Ferroptosis Involved in Paraquat-Induced Neurotoxicity of Dopaminergic Neurons: Implication for Neurotoxicity in PD. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2021, 2021, 9961628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.F.; Ga, Y.; Ma, D.Y.; Hou, S.L.; Hui, Q.Y.; Hao, Z.H. The role of ferroptosis in environmental pollution-induced male reproductive system toxicity. Environ Pollut 2024, 363, 125118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, S.J.; Tan, E.K.; Chao, Y.X. Historical Perspective: Models of Parkinson's Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorsey, E.R.; Ray, A. Paraquat, Parkinson's Disease, and Agnotology. Mov Disord 2023, 38, 949–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapoor, U.; Srivastava, M.K.; Trivedi, P.; Garg, V.; Srivastava, L.P. Disposition and acute toxicity of imidacloprid in female rats after single exposure. Food Chem Toxicol 2014, 68, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Wu, C.; Ba, D.; Wang, N.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Li, Q.; Zhao, G. Ferroptosis contribute to neonicotinoid imidacloprid-evoked pyroptosis by activating the HMGB1-RAGE/TLR4-NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2023, 253, 114655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Sheng, J.; Pei, H.; Sheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, X.; Li, W.; Cao, C.; Yang, Y. Environmental toxin chlorpyrifos induces liver injury by activating P53-mediated ferroptosis via GSDMD-mtROS. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2023, 257, 114938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen Gupta, P.; Karmakar, S.; Biswas, I.; Ghosal, J.; Banerjee, A.; Roy, S.; Mandal, D.P.; Bhattacharjee, S. Vitamin E alleviates chlorpyrifos induced glutathione depletion, lipid peroxidation and iron accumulation to inhibit ferroptosis in hepatocytes and mitigate toxicity in zebrafish. Chemosphere 2024, 359, 142252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesmar, F.; Muhsen, M.; Mirchandani, R.; Tourigny, J.P.; Tennessen, J.M.; Bondesson, M. The herbicide acetochlor causes lipid peroxidation by inhibition of glutathione peroxidase activity. Toxicol Sci 2024, 202, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.C.; Li, Z.; Harder, S.D.; Soukup, J.M. Apoptotic and inflammatory effects induced by different particles in human alveolar macrophages. Inhal Toxicol 2004, 16, 863–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, M.; Schrenk, D. Dioxin toxicity, aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling, and apoptosis-persistent pollutants affect programmed cell death. Crit Rev Toxicol 2011, 41, 292–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood-Donelson, K.I.; Jarmusch, A.K.; Bortner, C.D.; Merrick, B.A.; Sinha, B.K. Metabolic consequences of erastin-induced ferroptosis in human ovarian cancer cells: an untargeted metabolomics study. Front Mol Biosci 2024, 11, 1520876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, T.; Baran, R.; Suematsu, M.; Ueno, Y.; Ikeda, S.; Sakurakawa, T.; Kakazu, Y.; Ishikawa, T.; Robert, M.; Nishioka, T.; et al. Differential metabolomics reveals ophthalmic acid as an oxidative stress biomarker indicating hepatic glutathione consumption. J Biol Chem 2006, 281, 16768–16776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Ren, H.; Wang, J.; Xiao, X.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, L. CHAC1: a master regulator of oxidative stress and ferroptosis in human diseases and cancers. Front Cell Dev Biol 2024, 12, 1458716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, B.K.; Tokar, E.J.; Bortner, C.D. Molecular Mechanisms of Cytotoxicity of NCX4040, the Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory NO-Donor, in Human Ovarian Cancer Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, B.K.; Murphy, C.; Brown, S.M.; Silver, B.B.; Tokar, E.J.; Bortner, C.D. Mechanisms of Cell Death Induced by Erastin in Human Ovarian Tumor Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 8666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Sun, J.; Zhang, G.; Yu, T.; Piao, H. The three-dimension preclinical models for ferroptosis monitoring. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2022, 10, 1020971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstorum, A.; Tesfay, L.; Paul, B.T.; Torti, F.M.; Laubenbacher, R.C.; Torti, S.V. Systems biology of ferroptosis: A modeling approach. J Theor Biol 2020, 493, 110222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, G.; Gan, B. Exploring Ferroptosis-Inducing Therapies for Cancer Treatment: Challenges and Opportunities. Cancer research 2024, 84, 961–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huiting, L.N.; Laroche, F.; Feng, H. The Zebrafish as a Tool to Cancer Drug Discovery. Austin J Pharmacol Ther 2015, 3, 1069. [Google Scholar]

- Koppula, P.; Zhuang, L.; Gan, B. Cystine transporter SLC7A11/xCT in cancer: ferroptosis, nutrient dependency, and cancer therapy. Protein Cell 2021, 12, 599–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, I.; Berndt, C.; Schmitt, S.; Doll, S.; Poschmann, G.; Buday, K.; Roveri, A.; Peng, X.; Porto Freitas, F.; Seibt, T.; et al. Selenium Utilization by GPX4 Is Required to Prevent Hydroperoxide-Induced Ferroptosis. Cell 2018, 172, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodson, M.; Castro-Portuguez, R.; Zhang, D.D. NRF2 plays a critical role in mitigating lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. Redox Biol 2019, 23, 101107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, I.; Monteiro, L.K.S.; Guedes, C.B.; Silva, M.M.; Andrade-Tomaz, M.; Contieri, B.; Latancia, M.T.; Mendes, D.; Porchia, B.; Lazarini, M.; et al. High levels of NRF2 sensitize temozolomide-resistant glioblastoma cells to ferroptosis via ABCC1/MRP1 upregulation. Cell Death Dis 2022, 13, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).