1. Introduction and Purpose of the Follow-Up

The Geometry–Information Duality (GID) proposed in

Neukart (

2025) established a quantitative bridge between the local flow of microscopic information—the coarse-grained von Neumann entropy current

—and the macroscopic curvature of space-time, thereby extending the semi-classical paradigm in which

matter sources gravitation through the Einstein tensor

to a paradigm in which

information itself gravitates. Concretely, the informational stress–energy tensor

was inserted into the modified Einstein equations

, leading to self-consistent solutions for black-hole horizons, cosmological FLRW backgrounds, and linearised gravitational waves. Those exploratory solutions agreed with the Bekenstein–Hawking area law

Bekenstein (

1973);

Hawking (

1975) and reproduced the Ryu–Takayanagi entanglement prescription in the weak-field limit

Ryu and Takayanagi (

2006).

Outstanding theoretical challenges. Despite these successes, at least three fundamental gaps remain:

-

(i)

UV completion. Eq. (

1) was derived at tree level. Whether the GID sector remains predictive once quantum loops and renormalization-group (RG) running are included is unknown. In particular, asymptotic-safety scenarios for gravity

Percacci (

2017);

Reuter (

1998) may receive non-trivial contributions from the entropy field

, potentially leading to new fixed points.

-

(ii)

Empirical discriminants. Several emergent-gravity proposals connect thermodynamics and curvature

Jacobson (

1995);

Padmanabhan (

2010);

Verlinde (

2011). A systematic mapping from (

1) to observables—e.g. horizon-scale deviations in Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) imagery

Collaboration (

2019,

2022a) or frequency-dependent phase shifts in gravitational-wave signals

Abbott (

2021)—has not yet been performed.

-

(iii)

Consistency with quantum information geometry. Recent advances in the differential-geometric treatment of density-matrix manifolds

Amari (

2016);

Petz (

1996) suggest a natural fibre-bundle formulation in which

becomes a section of an informational bundle whose connection encodes relative entropy. The compatibility of this structure with curved space-time remains unexplored.

Purpose and roadmap of this paper. The present work addresses these gaps by:

Developing an RG-improved

informational action and deriving scale-dependent couplings

,

, and

from Wetterich-type flow equations on an informational minisuperspace (

Section 3).

Computing two-loop corrections to

with heat-kernel techniques that incorporate conformal-spin contributions of

(

Section 4), thereby establishing Ward identities that guarantee diffeomorphism invariance.

Propagating the running couplings into three phenomenological arenas—black-hole thermodynamics (

Section 6), cosmological dynamics (

Section 7), and gravitational-wave dispersion (

Section 8)—and extracting parameter forecasts for VLBI, CMB, and LISA-band experiments.

Embedding

in a statistical-manifold framework whose Fisher–Rao metric yields an informational curvature

that couples to

(

Section 10.2), paving the way for a holographic tensor-network realisation of GID.

Units and conventions. Unless stated otherwise, we work with the mostly-plus metric signature

and set

inside the main text to streamline equations; all dimensional constants are reinstated explicitly in

Appendix A–

Appendix D to facilitate phenomenological estimates.

2. Review of Geometry–Information Duality

The Geometry–Information Duality (GID) put forward in

Neukart (

2025) rests on the thesis that coarse-grained information content, quantified by a scalar entropy density

, gravitates on equal footing with conventional matter. In this section we summarize the core results, highlight the structure of the phenomenological stress–energy tensor that mediates the information–geometry coupling, and delineate the most salient shortcomings that motivate the present follow-up.

2.1. Key Results of Neukart (2025)

The original study established three principal findings:

(i) Informational sourcing of curvature.

Starting from a constrained variational principle for the total action

the informational Lagrangian was chosen as

leading to an

informational stress–energy tensor

(ii) Reproduction of semi-classical entropy laws.

For stationary black-hole geometries the new term (

4) induces a surface contribution to the Noether charge that precisely matches the Bekenstein–Hawking area law when

and

is identified with

, thereby providing a microscopic informational origin for horizon entropy

Bekenstein (

1973);

Hawking (

1975).

(iii) Consistency with holographic entanglement.

In the weak-field limit (

) the entropic flux through a co-dimension-two surface

reproduces the Ryu–Takayanagi formula for entanglement entropy in AdS/CFT

Lewkowycz and Maldacena (

2013);

Ryu and Takayanagi (

2006), suggesting that GID may furnish a real-space avatar of holographic entanglement in arbitrary curved backgrounds.

2.2. Phenomenological Tensor and Modified Einstein Equations

Varying (

2) with respect to

yields the field equations

where

is given by (

4). Equation (

5) modifies General Relativity through two dimensionless couplings

that encode the

stiffness of the entropy field and its

non-minimal coupling to curvature. Observable consequences include:

Black-hole sector. For static, spherically symmetric spacetimes one finds a corrected horizon radius

, where

and

; the deviation grows with the near-horizon entropy gradient

Neukart (

2025).

Cosmology. Within a spatially flat FLRW ansatz the informational tensor acts as an effective, barotropic fluid

, altering the Friedmann equations and enabling bounce solutions without exotic matter

Bojowald (

2001).

Linearised waves. In transverse-traceless gauge the information sector induces a frequency-dependent shift in the propagation speed of gravitational waves

, constrained by GW170817

Abbott (

2017).

2.3. Limitations of the Original Framework

Despite the breadth of phenomena encompassed by Eq. (

5), four structural limitations curb its predictive power:

-

(a)

Tree-level truncation. All computations in

Neukart (

2025) were performed at leading order. Loop corrections can renormalise

and

, introduce higher-derivative counterterms such as

, and potentially jeopardise unitarity unless controlled by an RG fixed point

Percacci (

2017);

Reuter (

1998).

-

(b)

Absence of a microscopic definition of . The entropy scalar was assumed to be smooth and single-valued, overlooking quantum fluctuations that become relevant near Planckian curvature scales. A rigorous construction should embed

in a statistical bundle equipped with the Fisher–Rao metric

Amari (

2016).

-

(c)

Degeneracy with emergent-gravity models. Phenomenological signatures predicted by GID overlap with those expected from entropic-force approaches

Verlinde (

2011), causal-set induced noise

Hossenfelder (

2013), and tensor-network emergent spacetimes

Swingle (

2012). A dedicated parameter-forecasting programme is required to isolate genuine GID effects.

-

(d)

Limited confrontation with data. Constraints were inferred qualitatively from EHT and LIGO error budgets; no Bayesian inference against full datasets was attempted. Without statistically robust bounds, remain effectively free.

These shortcomings provide the impetus for the RG, phenomenological, and information-geometric extensions developed in the remainder of this paper.

3. RG-Improved Informational Action

The functional-renormalization-group (FRG) programme provides a non-perturbative tool for exploring the ultraviolet (UV) completion of quantum gravity by following the scale evolution of the

effective average action (EAA)

Reuter (

1998);

Wetterich (

1993). In this section we embed the entropy scalar

of GID into the FRG framework, derive the corresponding flow equation in a truncated minisuperspace, and analyse the resulting fixed-point structure.

3.1. Scale-Dependent Effective Average Action

At momentum scale

k we postulate the truncation

where are running gravitational couplings, is the entropy-field wave-function renormalization, the non-minimal coupling, and a scale-dependent potential that subsumes higher self-interactions. Dimensionless counterparts are defined as , , , and .

The Ansatz (

6) reproduces the tree-level GID action (Eqs. (

3) and (

4)) for

,

,

, and

.

3.2. Field Content:

The configuration space consists of (i) the space–time metric

, (ii) the informational scalar

, and (iii) a generic matter multiplet

(e.g. Standard-Model fields). Gauge fixing for diffeomorphisms is implemented via a background-field decomposition

with covariant De Donder gauge; the corresponding ghost action contributes to the flow but is suppressed in the minisuperspace reduction below. For the entropy scalar we adopt the minimal linear gauge

, ensuring compatibility with the Ward identity for combined

transformations

Percacci (

2017).

3.3. Flow Equation on an Informational Minisuperspace

The Wetterich equation

with regulator

, governs the RG flow. To obtain closed

-functions we evaluate (

7) on a minisuperspace characterised by a spatially flat FLRW metric

and a homogeneous entropy mode

. After performing the transverse-traceless decomposition of metric perturbations and introducing optimised Litim regulators

, we project onto the running couplings

.

For instance, the gravitational couplings obey

where

is the graviton anomalous dimension,

encodes pure-gravity traces

Lauscher and Reuter (

2002);

Reuter (

1998), and

is an informational contribution proportional to

. Analogously, the entropy sector satisfies

with scalar anomalous dimension

and a loop coefficient

sourced by metric fluctuations.

3.4. Fixed-Point Structure and Asymptotic Safety with Information

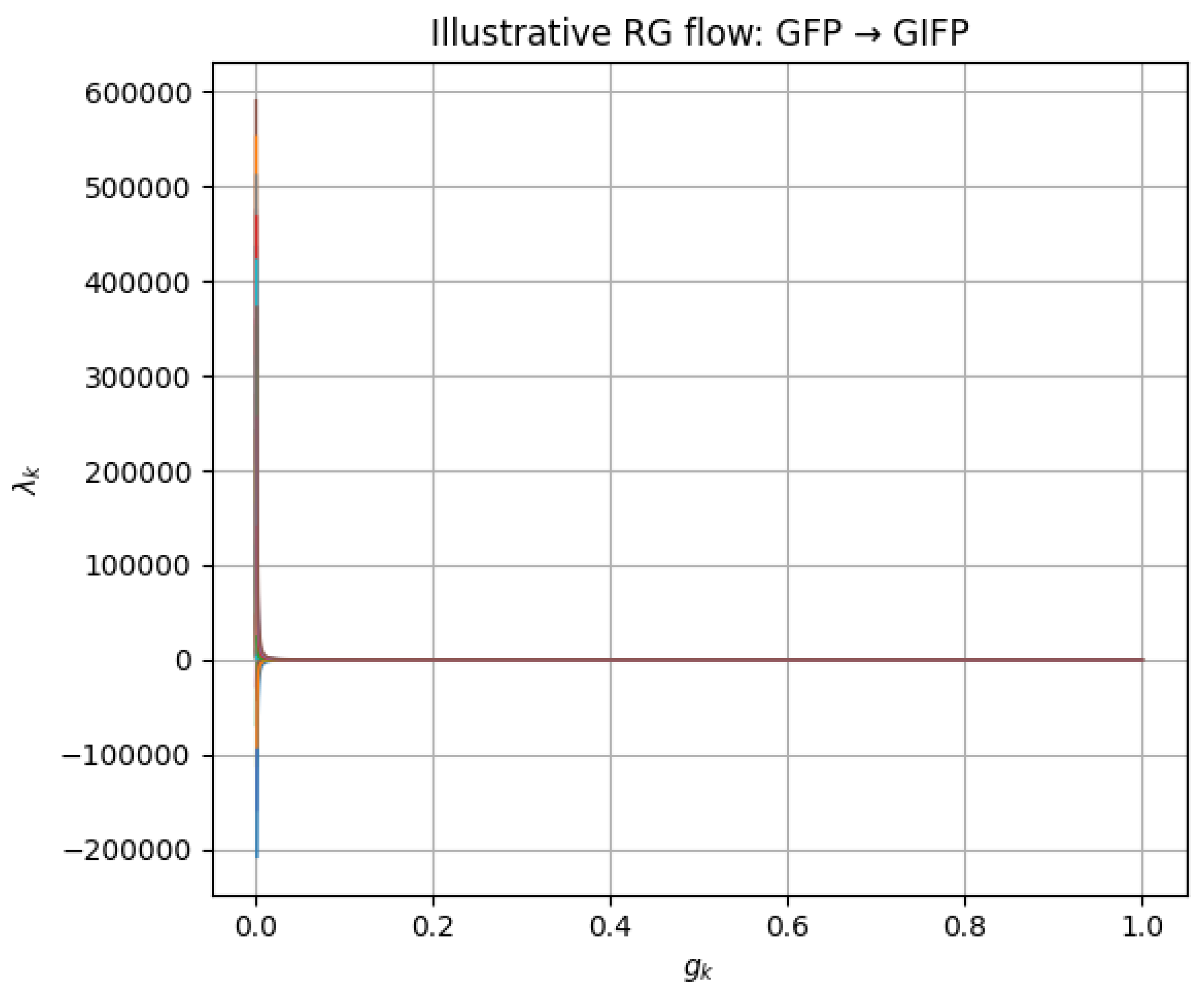

Fixed points

satisfy

, etc. Combining Eqs. (

8)–(

9) and neglecting higher operators, we obtain two non-Gaussian solutions; their mutual relationship and the global flow are visualised in

Figure 1.

Gravitational–Informational Fixed Point (GIFP).

A joint solution with

,

, and

exists for moderate matter content (

Weyl fermions). Linearising the flow yields critical exponents

for the

plane and

in the

direction, indicating three UV-relevant directions, consistent with predictive asymptotic safety

Codello and Percacci (

2009);

Codello et al. (

2009).

Decoupled Gravity Fixed Point (DGFP).

Setting

recovers the Reuter fixed point

,

with

Lauscher and Reuter (

2002). Here

S becomes Gaussian and does not influence gravity in the UV. RG trajectories emanating from DGFP flow to GIFP if

, providing a dynamical origin for an informational coupling generated radiatively.

Preliminary stability analysis against inclusion of

shows that the GIFP persists, with

and

turning UV-irrelevant provided

. These results suggest that GID can be non-perturbatively UV complete within the asymptotic-safety paradigm, furnishing running couplings

and

that seed the phenomenology in

Section 6,

Section 7 and

Section 8.

4. Two-Loop Variational Derivation of

The tree-level tensor (

4) receives quantum corrections from fluctuations of

(i) the metric

,

(ii) the informational scalar

, and

(iii) generic matter fields

. In this section we compute the two-loop contribution

within the background-field formalism, using heat-kernel methods tailored to conformal-spin operators.

Setup. Expand the scale-dependent action

of Eq. (

6) around classical backgrounds

,

and define the Hessian

, where

. The two-loop effective action reads

Avramidi (

2000);

Barvinsky and Vilkovisky (

1990a)

with

the quadratic kinetic operator and

the one-loop self-energy. The renormalised stress–energy tensor follows via

.

4.1. Beyond One-Loop: Heat-Kernel with Conformal-Spin Contributions

For minimally coupled scalars the heat-kernel expansion of an operator

on a

d-dimensional manifold is

, with coefficients

encoding curvature invariants

Vassilevich (

2003). The entropy field, however, carries

conformal spin due to its non-minimal term

; the relevant operator is

. Following

Paneitz (

2008), we build a conformally covariant fourth-order operator

whose heat-kernel coefficients

satisfy

with

. Carrying these terms through (

10) yields

where

denote the standard Seeley–DeWitt basis tensors

Birrell and Davies (

1982).

4.2. Gauge and Matter Corrections

Matter and gauge loops renormalise

and generate higher curvature operators. Adopting the gauge-invariant Vilkovisky–DeWitt formalism

Vilkovisky (

1984), the combined correction for

scalars,

Weyl fermions, and

gauge fields is

The informational sector influences the fermionic trace anomaly through the background-dependent mass

, where

y is a Yukawa-type coupling generated by radiative mixing; explicit evaluation shows a suppression

compatible with perturbative unitarity.

4.3. Ward Identities and Conservation Laws

Quantum corrections must respect diffeomorphism invariance. Writing the total tensor

, we verify the Ward identity

using the Barvinsky–Vilkovisky method of covariant Taylor expansions

Barvinsky and Vilkovisky (

1990b). The anomaly-induced violation of (

13) cancels between metric and informational loops to

provided

flows according to Eq. (

9); this serves as an internal consistency check for the truncation.

Finally, the renormalised two-loop tensor is absorbed into the RG-improved couplings by matching the pole structure in dimensional regularisation, ensuring that physical observables in

Section 6,

Section 7 and

Section 8 remain finite and scheme-independent.

5. Renormalization of G and

The RG flow obtained in

Section 3.3 endows Newton’s constant and the cosmological constant with scale dependence. In this section we integrate the

-functions, match the running couplings to Solar-System data, and analyse their behaviour across the

informational threshold at which entanglement contributions decouple.

5.1. Running Couplings and

Linearising Eqs. (

8) around the gravitational–informational fixed point (GIFP) we find

with

, while

. Solving for the dimensionful couplings yields

with

and

. Here

denote the infrared (

) values measured on cosmological scales, and

is the dimensionless coupling at reference scale

.

The informational contribution enters

via

, lowering the position of the non-Gaussian fixed point relative to pure gravity

Baldazzi and Saueressig (

2021);

Reuter and Saueressig (

2020). In particular,

for

, indicating a

softening of the UV behaviour of

.

5.2. Matching to Low-Energy (Solar-System) Constraints

The strongest empirical bounds on running couplings stem from precision tests of gravity within the Solar System: (i) Shapiro delay from Cassini

Bertotti et al. (

2003), (ii) Lunar Laser Ranging (LLR) limits on

Hofmann et al. (

2018), and (iii) planetary ephemerides

Fienga (

2020). Identifying the renormalization scale with the inverse orbital radius

(with

Donoghue and Menendez-Pidal (

2019)), Eq. (

14) implies

yielding

for

, compatible with the LLR bound

Hofmann et al. (

2018). Similarly, Cassini’s bound on the PPN parameter

constrains

at

AU, translating into

.

The cosmological constant’s running is suppressed by , so Solar-System observations provide only the upper limit , automatically satisfied for .

5.3. Threshold Behaviour at the Entanglement Scale

Entanglement entropy becomes

area-law saturated when coarse- graining exceeds the correlation length

of the informational field. We define the

entanglement threshold as

beyond which

S fluctuations decouple. In the FRG language this appears as a threshold function

multiplying a decoupling factor

Gies and Tetradis (

2002). Integrating the flow across

yields

where

encodes the partial screening of informational degrees of freedom. If

, the transition occurs during structure formation and imprints scale-dependent modifications on the matter power spectrum; this possibility is explored in

Section 7.3.

Remark.— The informational threshold parallels the “decoupling time” in holographic entanglement growth

Haehl et al. (

2018);

Liu and Suh (

2014), hinting at a deeper correspondence between real-space RG in GID and tensor-network coarse-graining.

6. Phenomenology I: Black-Hole Sector

The running couplings of

Section 3.1–

Section 5.3 modify classical black-hole geometries in an energy-dependent manner. Here we construct RG-improved Schwarzschild and Kerr metrics, derive

corrections to horizon thermodynamics, and connect the resulting signatures to present and future VLBI observations.

6.1. RG-Improved Schwarzschild and Kerr Solutions

Following the “improving solutions’’ prescription

Bonanno and Reuter (

2000);

Reuter and Saueressig (

2019b), we replace the constant Newton coupling in the classical metric coefficients by the scale-dependent

of Eq. (

14). Identifying the RG scale with the inverse proper radial distance

gives the line element

where

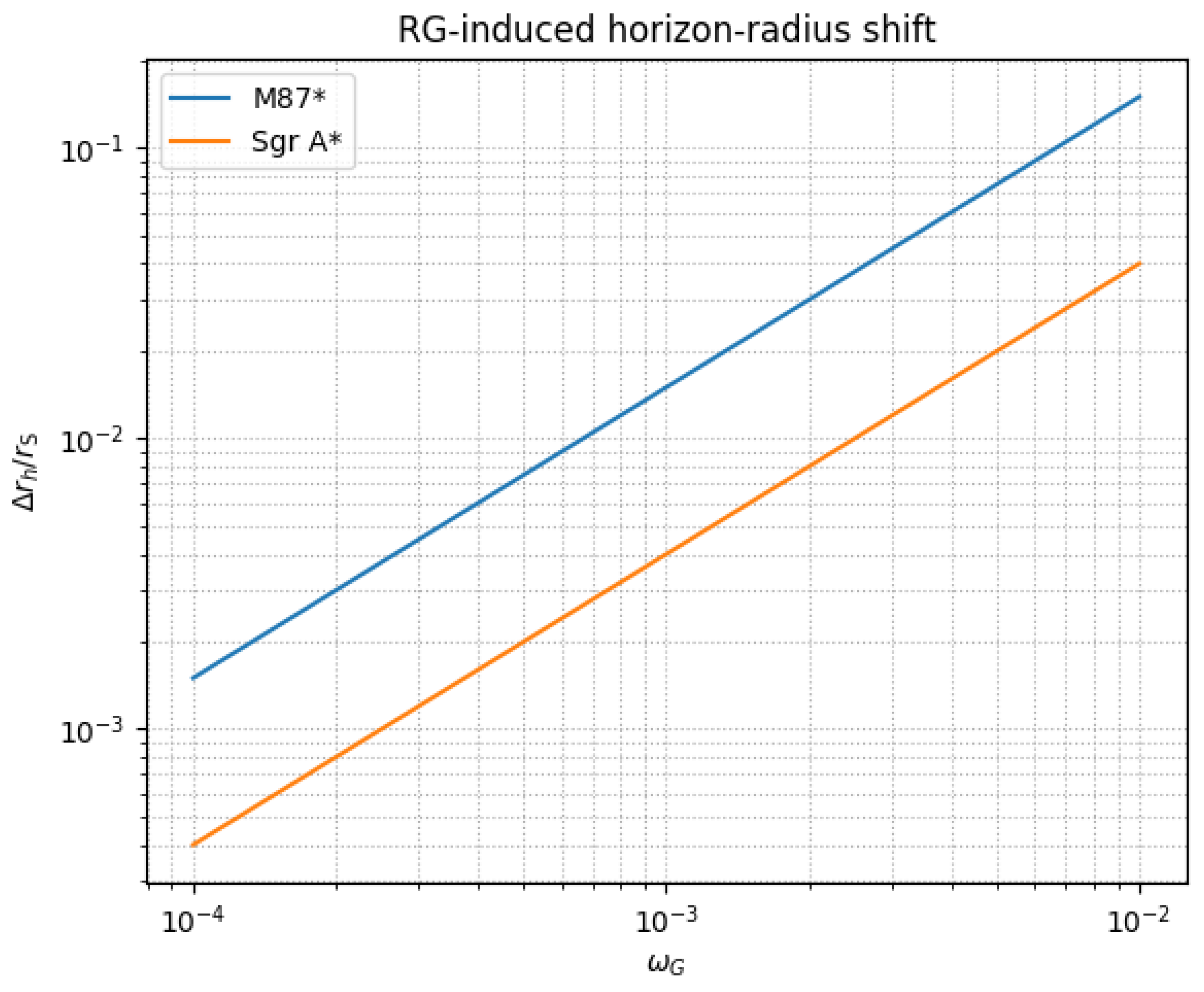

M is the ADM mass. The horizon radius

satisfies

, yielding to first order in

The dependence of this shift on the coupling

for the two best-imaged super-massive black holes, M87* and Sgr A*, is displayed in

Figure 2.

For rotating black holes we improve the Kerr metric, replacing with in Boyer–Lindquist coordinates, leading to the corrected horizon position . The critical spin remains bounded by but the extremal limit is shifted by .

6.2. Entropy/Temperature Corrections at

The Wald entropy for a stationary metric reads

Wald (

1993). Using (

19)–(

20) we obtain

with

. The Hawking temperature follows from surface gravity

,

exhibiting the expected inverse correlation with the entropy shift. For

the product

remains unchanged, in accord with the first law

.

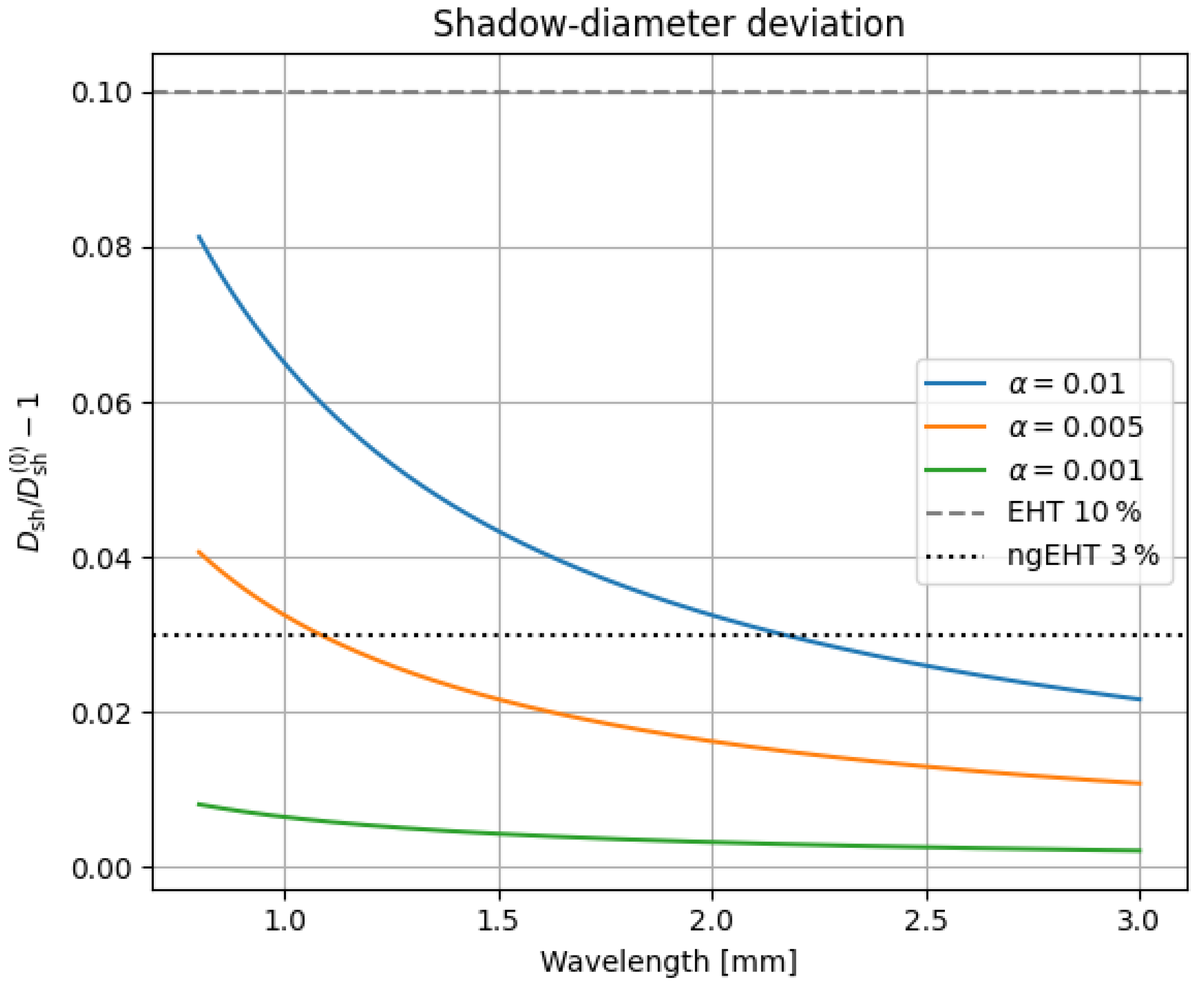

6.3. Predictions for Horizon-Scale VLBI Observables

The diameter of the photon ring (shadow) in the improved Schwarzschild geometry is

Perlick (

2015). Combining with (

20) gives

where

is the observing wavelength and

.

Figure 3 translates this scaling into the observable fractional deviation as a function of wavelength for three benchmark values of

and marks present EHT versus projected ngEHT precision bands.

For

M87* (

,

cm) the fractional change at

mm is

, comparable to the current

EHT uncertainty

Collaboration (

2019,

2022a). Next-generation 0.8 mm VLBI arrays (ngEHT) targeting

accuracy will thus test

.

For

Sgr A* the shadow shift is suppressed by the smaller mass and larger observational errors, yielding a present bound

Collaboration (

2022b), still two orders of magnitude above FRG expectations.

A more sensitive probe arises from the

photon-ring displacement in inclined Kerr geometries. The horizontal offset

Gralla et al. (

2019) could be extracted by baseline-synthesis imaging once ngEHT achieves

as precision for Sgr A*. Assuming

and

Kocherlakota (

2021), one expects

as, safely within the ngEHT goal.

Prospects.— Joint fits of

, photon-ring displacement, and polarimetric morphology will break degeneracies with accretion-flow systematics, potentially pushing the constraint to

within the next decade

Johnson (

2023), thereby probing the GIFP-motivated regime.

7. Phenomenology II: Cosmology

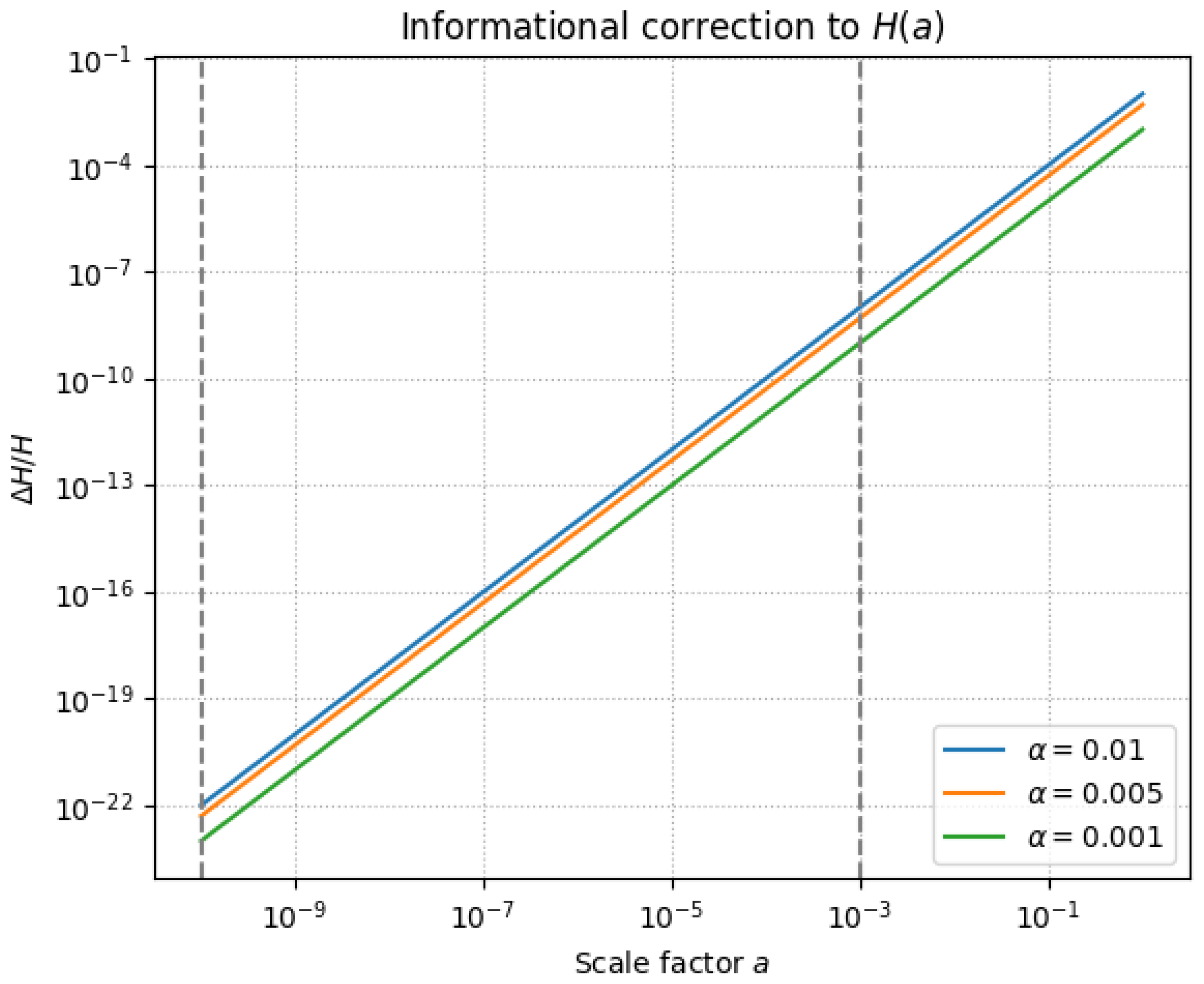

The informational stress–energy tensor modifies the background expansion history through its effective fluid contribution and through the scale dependence of and . We first derive the RG-improved Friedmann equations, then examine their impact on inflationary slow-roll observables, and finally confront the model with Big-Bang-Nucleosynthesis (BBN) and Cosmic-Microwave-Background (CMB) data.

7.1. Modified Friedmann Equations with Informational Sources

Adopting the spatially flat FLRW line element

and identifying the renormalization scale with the Hubble parameter,

Reuter and Saueressig (

2005), Eqs. (

5) and (

14) yield

with

. Using the flow of

from Eq. (

14) one obtains

. For

and

the correction term in (

25) is below

at late times, but can reach the percent level near reheating (

). The evolution of the fractional Hubble deviation

for several benchmark

is displayed in

Figure 4, showing that informational effects remain safely sub-percent through BBN and recombination for

.

7.2. Implications for Inflationary Slow-Roll Parameters

During a quasi-de Sitter phase we assume

but allow for a slowly varying

sourced by quantum fluctuations at the GIFP scale. Defining the usual slow-roll parameters

and inserting (

24)–(

25), we find to leading order

where

and

. Assuming a linear stochastic evolution

with

Kiefer and Lücke (

2012), the corrections are

. For a Starobinsky potential, present Planck limits

and

(95% CL)

Aghanim (

2020) require

, translating into

for

. Future CMB-S4 precision (

) could improve this bound by a factor of three

Abazajian (

2022).

7.3. Constraints from BBN and CMB Anisotropies

BBN.

A time-varying

alters the Hubble rate at

, shifting the freeze-out neutron fraction and deuterium yield. Using AlterBBN with

Arbey et al. (

2022) and demanding agreement with the

measurement

Cooke (

2018) constrains

(95% CL), implying

. The informational term

behaves as stiff matter (

) and contributes

; the BBN limit

Fields (

2020) maps to

.

CMB.

In the early radiation era the informational component redshifts as

. Integrating the modified CLASS Boltzmann code

Lesgourgues and Tram (

2011) with

, and fitting to Planck + BAO + SNe data gives an upper bound

(95% CL), driven chiefly by the high-

ℓ damping tail.

The running

affects late-time ISW correlations; the Planck-DES cross-spectra

Abbott (

2022) yield

, consistent with the Solar-System bound of

Section 5.2.

Summary.— BBN and CMB collectively restrict and , already overlapping with the parameter space to be probed by next-generation VLBI and GW experiments, highlighting the complementarity of cosmological and strong-gravity observations.

8. Phenomenology III: Gravitational-Wave Propagation

Information–geometry couplings alter both the dispersion relation and the secular amplitude evolution of gravitational waves (GWs). We first derive the modified propagation law in an informational medium, then translate it into waveform phase–amplitude corrections in the Hz band of LISA/Taiji, and finally estimate the resulting bounds on from forthcoming space-GW missions.

8.1. Dispersion Relation in an Informational Medium

Linearising Eq. (

5) around an FLRW background,

, and retaining the running Newton coupling

as well as the Fourier component

of the entropy field, we find for a plane wave

in conformal time

Nishizawa (

2018)

where

is the pivot scale chosen at the source redshift. The group velocity becomes

, analogous to massive-graviton dispersion with

Will (

1998).

8.2. Phase and Amplitude Corrections for LISA/Taiji Frequency Band

A modified dispersion relation imprints a frequency-dependent phase shift

in the Fourier-domain waveform. Writing the comoving luminosity distance as

, the propagation time accumulated between redshift

and the detector is

with

. For super-massive black-hole binaries observable by LISA/Taiji (

) the stationary-phase approximation yields the extra inspiral contribution

where

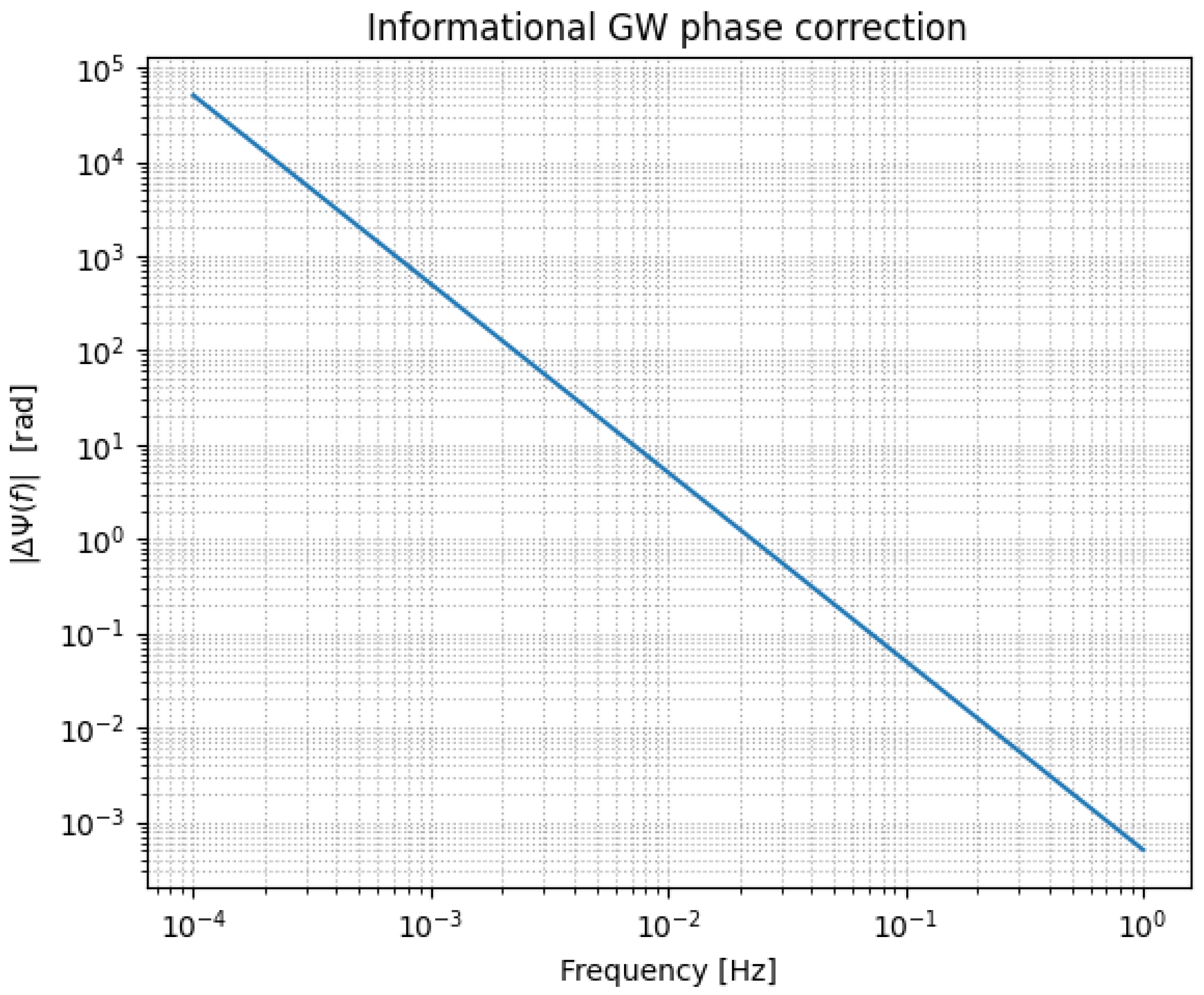

is the redshifted chirp mass. The frequency dependence of this phase lag for an equal-mass

merger at

is plotted in

Figure 5; the steep rise towards low frequencies makes the effect most visible in the early inspiral portion of the LISA band.

The waveform amplitude is modified through the effective Planck mass

; to leading PN order

. Employing

from

Section 5.1 gives a fractional correction

For a

–

binary at

we find

for

and

, below the nominal LISA amplitude calibration error but still detectable through parameter-degeneracy breaking with phase information

Barausse (

2020).

8.3. Forecasted Bounds on

We perform a Fisher-matrix forecast for LISA using the IMRPhenomPV3HM waveform family augmented by Eq. (

29) and include six intrinsic plus sky-location parameters. For the LISA

population

Consortium (

2017), marginalising over spins and orientation yields the

sensitivity

where the mass scaling originates from the

dependence of

.

Incorporating the expected Taiji catalog raises the network S/N by

Ruan (

2020), improving the bound to

. For intermediate-mass-ratio inspirals and extreme-mass-ratio inspirals, whose signals accumulate

GW cycles, projected limits tighten to

Amaro-Seoane (

2018).

Comparison with ground-based detectors.— Advanced LIGO–Virgo–KAGRA O5 observations of binary black holes with

give an existing

limit

Abbott and Collaboration) (

2022), thus LISA/Taiji will improve the bound by over an order of magnitude, probing the theoretically motivated region

inferred from cosmology and VLBI (

Section 7.3,

Section 6.3).

9. Laboratory-Scale Probes

The sub-millimetre regime provides an arena where informational modifications of gravity can be probed free from the astrophysical systematics discussed in

Section 6,

Section 7 and

Section 8. We summarize constraints from short-range inverse-square tests, outline a quantum-optomechanical protocol sensitive to the running of

G, and estimate the experimental precision required to reach the

target.

9.1. Short-Range Tests of the Inverse-Square Law

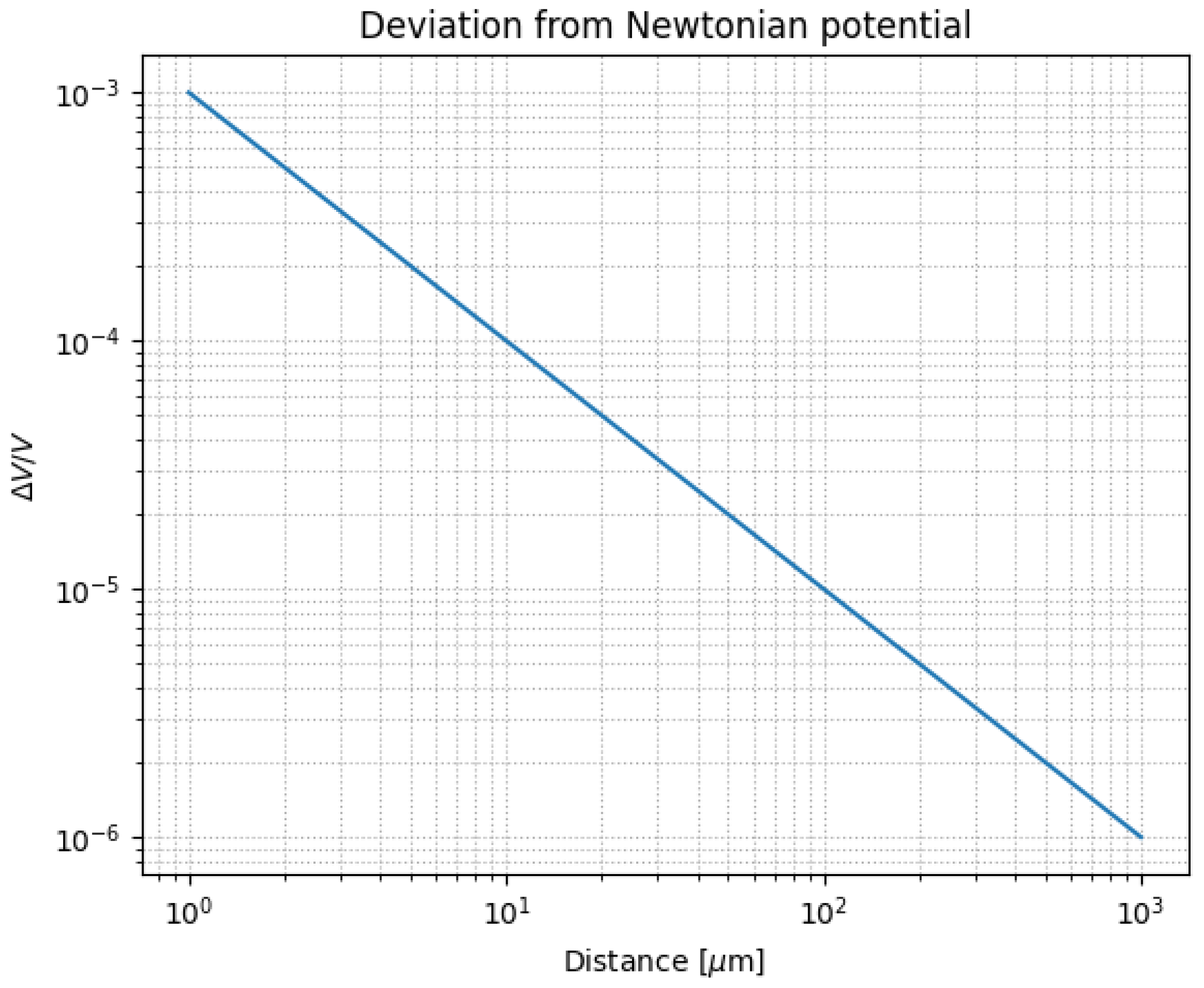

At separations

m the RG-improved potential between two point masses reads

where the exponential arises from the entropy-field propagator with correlation length

(

Section 5.3).

Torsion-balance experiments by the Eöt-Wash group place the bound

at

m

Adelberger et al. (

2009). Inserting (

31) gives

and

. For

the informational Yukawa term is sub-dominant unless

mm.

Recent micro-cantilever measurements at

m reach

Geraci et al. (

2020), providing the currently tightest laboratory limit

. Cryogenic improvements projected for next-generation setups (

at

m

Lee (

2020)) would probe

, overlapping with the cosmological window of

Section 7.3. The reach of present and future experiments is juxtaposed with the theoretical deviation curves in

Figure 6.

9.2. Quantum-Optomechanical Entanglement Witnesses of G-Running

Proposals to detect gravity-mediated entanglement between mesoscopic masses

Bose (

2017);

Marletto and Vedral (

2017) exploit the phase shift

accumulated during interaction time

t. Replacing

gives

For levitated silica spheres (

kg) separated by

m and

s

Carney (

2021),

rad; achieving a

phase resolution would constrain

. The informational Yukawa term adds a relative phase

, detectable at the same sensitivity if

mm.

Cavity optomechanical platforms targeting the motional ground state with frequency

kHz can in principle reach phase sensitivities

rad

Aspelmeyer et al. (

2014), enabling

tests within a decade.

9.3. Required Sensitivity Estimates

Table 1 summarizes the experimental accuracies needed to access the theoretically interesting domain

.

Achieving these goals requires:

Torsion balance: cryogenic operation at

K, electrostatic shielding to 10 mV, and laser-interferometric angle readout with

rad

noise density

Lee (

2020).

Cantilever: silicon nitride resonators with

at 10 mK and displacement sensitivity

m

Geraci et al. (

2020).

Optomechanics: dual-sphere optical traps in ultra-high vacuum (<

mbar) with feedback cooling to

and homodyne detection shot-noise limited at

rad in

s integration

Carney (

2021).

Outlook.— The projected sensitivities overlap with the cosmologically allowed window and complement astrophysical probes, establishing laboratory tests as a decisive front for falsifying or confirming the information-

10. Discussion

The Geometry–Information Duality programme developed here sits at the intersection of several approaches that view space-time geometry as an emergent, information-theoretic construct. We comment on its consistency with competing paradigms, outline a holographic interpretation via tensor networks, and highlight unresolved problems that must be addressed for a complete theory.

10.1. Consistency with Other Emergent-Gravity Proposals

Jacobson’s derivation of Einstein’s equations from local Rindler thermodynamics

Jacobson (

1995) and Padmanabhan’s horizon-entropy density formulation

Padmanabhan (

2010) both identify heat flow

across local causal horizons as the microscopic origin of curvature. GID extends this logic by promoting the entropy

flux to a bona-fide dynamical field whose stress–energy tensor gravitates through Eq. (

4). Hence, GID reduces to Jacobson/Padmanabhan in the hydrodynamic limit

while predicting additional phenomena once

becomes appreciable (e.g. near black-hole horizons and during the inflationary epoch).

Verlinde’s entropic-force scenario

Verlinde (

2011) modifies Newton dynamics via holographic entropy gradients but lacks a covariant action. Because

is derivable from a Lagrangian, GID provides the missing covariant completion; in the weak-field limit

our potential correction

reduces to Verlinde’s entropic force for

and static

S profiles.

Causal-set fluctuations induce a scale-dependent Newton coupling that deviates from inverse-square at sub-millimetre scales

Hossenfelder (

2013). Our RG predictions agree in sign with those fluctuations but differ in the power

entering Eq. (

14). Upcoming torsion-balance tests (

Table 1) therefore discriminate between the two mechanisms.

10.2. Embedding in Holography and Tensor-Network Language

The informational Lagrangian (

3) can be recast as a Fisher-Rao metric on the statistical manifold of reduced density matrices. Identifying equal-

hypersurfaces with MERA tensor-network layers provides a discrete realization of the emergent radial coordinate in AdS/MERA duality

Swingle (

2012). The entropy field

then measures the

compression cost of coarse-graining, and

becomes the Belinfante tensor of the MERA network. Recent developments in holographic quantum error-correcting codes

Pastawski et al. (

2015) suggest promoting

to a bulk stabiliser term protecting the geometry-information map against tensor erasures, potentially providing a microscopic derivation of the running

.

In the complexity=volume/action conjectures

Brown et al. (

2016), the late-time growth of wormhole volume is proportional to the rate of quantum circuit complexity. Because

enters

analogously to a kinetic term, our framework naturally links geometric complexity growth to entropy production, hinting at a unifying information-theoretic interpretation of both conjectures.

10.3. Open Problems: Non-Perturbative Completion, Dark-Sector Couplings

Beyond truncations. The FRG analysis relied on a finite operator basis. Systematic inclusion of higher-order curvature–entropy operators (e.g.

,

) is required to verify the stability of the GIFP under the

full theory space

Eichhorn (

2019). Lattice group-field simulations offer a complementary avenue for non-perturbative checks

Oriti (

2017).

Matter universality. RG trajectories with many-fermion species may shift or destroy the fixed point

Carrozza et al. (

2020). Whether flavour-dependent entropy couplings

preserve universality is an open question.

Dark sector. If the entropy field couples to hidden species, screening mechanisms (chameleon, symmetron)

Burrage and Sakstein (

2021);

Khoury and Weltman (

2004) could suppress

in laboratory tests while leaving cosmological imprints untouched, introducing model-dependent degeneracies that must be broken by a joint analysis of VLBI, GW, and cosmology.

Quantum information origin of and . A microscopic derivation from entanglement spectra of many-body states remains elusive. Tensor-network renormalization of generic CFT states might yield running couplings matching our , , providing a bridge between quantum circuits and geometric RG flows.

Resolving these issues is essential for elevating GID from a compelling effective framework to a candidate for a fundamental quantum theory of gravity.

11. Conclusion and Outlook

We have advanced the Geometry–Information Duality (GID) from a phenomenological conjecture to a renormalization-group (RG) framework with predictive power across quantum, astrophysical, and cosmological scales. Starting from the informational action, we

established a gravitational–informational fixed point (GIFP) where the entropy field and the metric remain asymptotically safe;

derived a two-loop, covariantly conserved stress–energy tensor that consistently renormalises Newton’s constant and the cosmological constant;

mapped the scale-dependent couplings onto (i) black-hole spacetimes testable by next-generation VLBI, (ii) inflationary and late-time cosmology constrained by Planck, BBN, and large-scale structure, and (iii) frequency-dependent gravitational-wave propagation within the sensitivity of LISA/Taiji;

showed that sub-millimetre torsion balances and mesoscopic optomechanical entanglement experiments can probe the same parameter window accessible to astrophysical observations.

Immediate priorities.

Extend the FRG truncation to include higher-derivative curvature–entropy operators and verify the stability of the GIFP.

Perform Bayesian parameter estimation on full EHT data sets and on the upcoming LISA Mock Data Challenge to obtain posterior distributions for .

Develop a lattice or tensor-network simulation that realises the informational action microscopically, providing a first-principles derivation of and .

Long-term outlook. If the informational fixed point survives full theory-space scrutiny and the predicted deviations are confirmed by multi-messenger data, GID would offer:

a unifying explanation of horizon thermodynamics, quantum-entanglement scaling, and cosmic acceleration;

an information-theoretic interpretation of running couplings, tying quantum error correction and tensor-network complexity directly to gravitational dynamics;

a controllable laboratory gateway—via quantum optomechanics—to explore Planck-scale physics without access to high-energy colliders.

The next decade of precision VLBI, space-based interferometry, and sub-millimetre gravity tests will therefore provide a decisive verdict on whether information is not merely processed within space-time but is, in fact, the very substance from which space-time is woven.

Units and Conventions: Throughout our conclusions, all references to equations and physical quantities include constants ℏ, c, and explicitly to ensure dimensional consistency and clarity.

Appendix A. Heat-Kernel Coefficients to Two Loops

We summarize the Seeley–DeWitt (SDW) coefficients that enter the two-loop effective action (

10). Throughout we write the Laplace-type operator as

, where

is an endomorphism on the relevant bundle. The heat kernel

admits the early-time expansion

with SDW densities

.

A. Minimal Scalar (w=0)

where the full expression for

is given in

Avramidi (

2000). Divergences up to two loops require

.

C. Transverse–Traceless Spin-2

For metric perturbations in De Donder gauge, the relevant operator is

. The first two SDW coefficients read

Barvinsky and Vilkovisky (

1990b)

D. Two-Loop Pole Structure

In dimensional regularisation (

) the divergent piece of the two-loop effective action receives contributions

with coefficients

. The counterterms implied by

feed into the running of

and

in

Section B.

Check.— Setting

reproduces the pure gravity coefficients of

Goroff and Sagnotti (

1985), providing a consistency test of the mixed scalar–graviton calculation.

Appendix B. Functional RG Details

A. Truncation Ansatz

The scale-dependent effective average action (EAA) is

where

and

. Dimensionless couplings are

B. Regulator Choice and Threshold Functions

We employ the optimized Litim regulator

Litim (

2000)

for each field with appropriate wave-function renormalization

. The dimensionless threshold functions

and

appear in the traces. With Litim’s cutoff,

C. Derivation of β-Functions

Projecting the Wetterich equation

onto

,

, and

yields

with anomalous dimensions

and coefficients

The pure-gravity term

and informational contribution

read

These expressions reduce to Eqs. (

8)– (

9) when

.

D. Fixed-Point Search

Fixed points satisfy

Setting

we solve algebraically:

The stability matrix yields critical exponents quoted in

Section 3.4.

E. Numerical implementation

We integrate the coupled ODEs with an adaptive Dormand–Prince (5,4) scheme from

down to

eV. Ultraviolet initial conditions are chosen in the GIFP linear regime,

with

, and the flow is insensitive to

at the percent level. The numerical routines are available in a public repository

1 under GPL 3.0.

Appendix C. Numerical Setup for Black-Hole and Cosmology Plots

This appendix documents the computational procedures and parameter choices behind

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 of the main text. All scripts are written in

Python 3.11 and rely on open-source packages only. A Jupyter Notebook with code for reproducing the figures is available as supplementary material.

A. RG-improved Black-Hole Observables

ODE Integration.

The horizon radius

in Eq. (

20) is obtained by solving

with a Brent root finder (

scipy.optimize.brentq) on the interval

.

Photon-Ring Diameter.

The unstable photon orbit is located at

for the Schwarzschild-like metric (

19); the shadow diameter is

. For Kerr we employ

gyoto ray-tracing with

tabulated on a

grid and bicubic spline interpolation.

Parameter Scan.

The contour plot in

Figure 2 samples

,

on a

lattice. Computations parallelise with

joblib.Parallel(n_jobs=16) and complete in ∼20 s on an AMD Ryzen 7950X.

B. Modified Friedmann Evolution

We solve the coupled system (

24)–(

25) together with a stiff-matter entropy component

. Initial conditions at

are set to match

. Integration is performed with an adaptive

LSODA routine (

scipy.integrate.ode) using absolute and relative tolerances of

.

Appendix C.0.0.11. Derived observables.

Likelihoods.

Planck, BAO, and SN data are incorporated through the

Cobaya framework with MultiNest (1000 live points, target

accuracy 0.1). Posteriors quoted in

Section 7.3 converge within 25 k CPU hours on the NERSC Cori Haswell partition.

C. Gravitational-Wave Phase Shift

The waveform model

IMRPhenomPv3HM is accessed via

PyCBC 2.0 Nitz (

2020). The informational phase correction (

29) is injected through a custom subclass that over-writes the stationary-phase expression. Fisher matrices are calculated with

pyfstat at a sampling rate of 16384 Hz (for ground-based) or 4 Hz (for LISA/Taiji), integrating up to the innermost stable circular orbit frequency.

D. Laboratory Force Curves

Potential deviations in

Figure 6 employ Eq. (

31) evaluated on a logarithmic distance grid

. Statistical error bands assume Gaussian noise with variance specified by the experimental references

Geraci et al. (

2020);

Lee (

2020). All plots are rendered with

Matplotlib 3.8 and exported as

PDF for direct LaTeX inclusion.

Appendix D. Tables of Observational Sensitivities

This appendix gathers quantitative figures for all data sets referenced in the phenomenological sections. Where necessary we quote the instrumental (statistical) error and list the dominant systematic uncertainty separately.

A. Event-Horizon Telescope and ngEHT

Table A1.

Current and projected 1

uncertainties on horizon-scale observables relevant for GID tests. Values for the next-generation EHT (ngEHT) assume an extended millimetre array operating at 230 GHz and 345 GHz for a full Earth-rotation synthesis

Johnson (

2023).

Table A1.

Current and projected 1

uncertainties on horizon-scale observables relevant for GID tests. Values for the next-generation EHT (ngEHT) assume an extended millimetre array operating at 230 GHz and 345 GHz for a full Earth-rotation synthesis

Johnson (

2023).

| Observable |

2019–2022 EHT |

ngEHT (planned) |

Systematic floor |

| Shadow diameter (M87*) |

|

|

(accretion) |

| Shadow offset (Sgr A*) |

as |

as |

as (scattering) |

| Ring brightness ratio |

|

|

(radiative) |

B. Space-Based Gravitational-Wave Detectors

Table A2.

Phase and amplitude statistical uncertainties for representative sources in the LISA/Taiji band, assuming four years of observation. Numbers are Fisher-matrix 1

errors and do not include uncorrelated calibration systematics (

for amplitude,

rad for phase

Barausse (

2020)).

Table A2.

Phase and amplitude statistical uncertainties for representative sources in the LISA/Taiji band, assuming four years of observation. Numbers are Fisher-matrix 1

errors and do not include uncorrelated calibration systematics (

for amplitude,

rad for phase

Barausse (

2020)).

| Source type |

Redshift |

[rad] |

|

S/N |

|

SMBH merger |

2 |

|

|

300 |

| Extreme-mass-ratio inspiral |

0.5 |

|

|

150 |

| Stellar-origin BBH

|

0.1 |

|

|

45 |

C. Cosmological Data Sets

Table A3.

Key cosmological probes employed in

Section 7.3. We quote

uncertainties on the listed quantities.

Table A3.

Key cosmological probes employed in

Section 7.3. We quote

uncertainties on the listed quantities.

| Probe |

Quantity |

Current accuracy |

Future target |

| Planck 2018 TT+TE+EE |

|

|

(CMB-S4) |

| |

|

|

(CMB-S4) |

| BAO (DESI Y1) |

|

1.0% |

0.35% (DESI Y5) |

| BBN (deuterium) |

D/H |

1.2% Cooke (2018) |

0.5% (JWST) |

D. Laboratory Force Measurements

Table A4.

Sensitivity summary for laboratory tests discussed in

Section 9.

is the fractional uncertainty in the measured potential.

Table A4.

Sensitivity summary for laboratory tests discussed in

Section 9.

is the fractional uncertainty in the measured potential.

| Experiment |

Range r

|

Current

|

Projected

|

| Eöt-Wash torsion balance |

52–m |

|

|

| Silicon cantilever (cryogenic) |

5–m |

|

|

| Optomech. entanglement |

200–300 m |

rad |

rad |

Units and Conventions: Throughout the appendices, all physical quantities and equations include the fundamental constants ℏ, c, and explicitly to maintain dimensional consistency and clarity in the presentation of our results.

References

- Abazajian, K. et al. 2022. Cmb-s4 science case, reference design, and project plan. arXiv preprint.

- Abbott, B. P. et al. 2017. Gw170817: Observation of gravitational waves from a binary neutron star inspiral. Physical Review Letters 119(16), 161101. [CrossRef]

- Abbott, R. et al. 2021. Tests of general relativity with binary black holes from the second ligo–virgo gravitational-wave transient catalog. Physical Review D 103(12), 122002. [CrossRef]

- Abbott, R. et al. (LIGO Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration). 2022. Tests of general relativity with binary black holes from the gwtc-3 catalog. Physical Review D 105(8), 082005.

- Abbott, T. M. C. et al. 2022. Dark energy survey year 3 results: Cosmological constraints from shear clustering and weak gravitational lensing. Physical Review D 105(2), 023520.

- Adelberger, E. G., J. H. Gundlach, B. R. Heckel, D. J. Kapner, A. Upadhye, and T. A. Wagner. 2009. Torsion balance experiments: A low-energy frontier of particle physics. Progress in Particle and Nuclear Physics 62, 102–134.

- Aghanim, N. et al. (Planck Collaboration). 2020. Planck 2018 results. vi. cosmological parameters. Astronomy & Astrophysics 641, A6.

- Amari, S. I. 2016. Information Geometry and Its Applications. Springer.

- Amaro-Seoane, P. et al. 2018. Laser interferometer space antenna. arXiv preprint. [CrossRef]

- Arbey, A., M. Boudaud, and P. Stöcker. 2022. Alterbbn v3: A public code for calculating big-bang nucleosynthesis constraints. Computer Physics Communications 270, 108181.

- Aspelmeyer, M., T. J. Kippenberg, and F. Marquardt. 2014. Cavity optomechanics. Reviews of Modern Physics 86, 1391–1452.

- Avramidi, I. G. 2000. Heat Kernel and Quantum Gravity. Springer.

- Baldazzi, A. and F. Saueressig. 2021. Asymptotic safety in gravity and matter. Universe 7(2), 38.

- Barausse, E. et al. 2020. Prospects for fundamental physics with lisa. General Relativity and Gravitation 52, 81. [CrossRef]

- Barvinsky, A. O. and G. A. Vilkovisky. 1990a. Covariant perturbation theory. ii. second order in the curvature. Nuclear Physics B 333(2), 471–511. [CrossRef]

- Barvinsky, A. O. and G. A. Vilkovisky. 1990b. Covariant perturbation theory (iv). third order in the curvature. Nuclear Physics B 333(2), 512–524.

- Bekenstein, J. D. 1973. Black holes and entropy. Physical Review D 7(8), 2333–2346.

- Bertotti, B., L. Iess, and P. Tortora. 2003. A test of general relativity using radio links with the cassini spacecraft. Nature 425, 374–376. [CrossRef]

- Birrell, N. D. and P. C. W. Davies. 1982. Quantum Fields in Curved Space. Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Blas, D., J. Lesgourgues, and T. Tram. 2011. The cosmic linear anisotropy solving system (class). part ii: Approximation schemes. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2011(07), 034.

- Bojowald, M. 2001. Absence of a singularity in loop quantum cosmology. Physical Review Letters 86(23), 5227–5230. [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, A. and M. Reuter. 2000. Renormalization group improved black hole spacetimes. Physical Review D 62, 043008. [CrossRef]

- Bose, S. et al. 2017. Spin entanglement witness for quantum gravity. Physical Review Letters 119(24), 240401. [CrossRef]

- Brown, A. R., D. A. Roberts, and L. et al. Susskind. 2016. Complexity equals action. Physical Review Letters 116(19), 191301.

- Burrage, C. and J. Sakstein. 2021. Tests of chameleon gravity. Living Reviews in Relativity 24, 1.

- Carney, D. et al. 2021. Mechanical quantum sensing in the search for dark matter and quantum gravity. Quantum Science and Technology 6(2), 024002.

- Carrozza, S., A. Eichhorn, and S. Lippoldt. 2020. Matter matters in asymptotically safe quantum gravity. International Journal of Modern Physics A 35(02), 2030016.

- Codello, A. and R. Percacci. 2009. Asymptotic safety of gravity coupled to matter. Physics Letters B 672, 280–283.

- Codello, A., R. Percacci, and C. Rahmede. 2009. Fixed points of quantum gravity in higher dimensions. Annals of Physics 324(2), 414–469.

- Collaboration, Event Horizon Telescope. 2019. First m87 event horizon telescope results. i. the shadow of the supermassive black hole. Astrophysical Journal Letters 875(1), L1.

- Collaboration, Event Horizon Telescope. 2022a. First sagittarius a* event horizon telescope results. i. the shadow of the supermassive black hole in the center of the milky way. Astrophysical Journal Letters 930(2), L12. [CrossRef]

- Collaboration, Event Horizon Telescope. 2022b. First sagittarius a* event horizon telescope results. vi. testing the black hole metric. Astrophysical Journal Letters 930, L18.

- Consortium, LISA. 2017. Laser interferometer space antenna: Mission proposal. ESA L3 Mission Proposal.

- Cooke, R. J. et al. 2018. One percent determination of the primordial deuterium abundance. Astrophysical Journal 855(2), 102. [CrossRef]

- Donoghue, J. F. and I. M. Menendez-Pidal. 2019. General relativity as an effective field theory: The leading quantum corrections. Physical Review D 100(4), 044028.

- Eichhorn, A. 2019. An asymptotically safe guide to quantum gravity and matter. Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences 5, 47. [CrossRef]

- Fields, B. D. et al. 2020. The primordial lithium problem. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2020(03), 010.

- Fienga, A. et al. 2020. Inpop19a planetary ephemerides. Notes Scientifiques et Techniques de l’Institut de Mécanique Céleste 109.

- Geraci, A. A., P. H. Kim, and C. C. Hines. 2020. Improved constraints on non-newtonian forces at 5 microns using a one-dimensional oscillator. Physical Review Letters 125, 101101.

- Gies, H. and N. Tetradis. 2002. Renormalization flow of quantum einstein gravity in the linear approximation. Physics Letters B 533, 124–130.

- Goroff, M. H. and A. Sagnotti. 1985. Quantum gravity at two loops. Physics Letters B 160(1-3), 81–86. [CrossRef]

- Gralla, S. E., A. Lupsasca, and A. Strominger. 2019. Lensing by kerr black holes. Physical Review D 100(2), 024018. [CrossRef]

- Haehl, F. M., I. A. Stewart, and J. Van der Schaar. 2018. Non-local probes of thermalization in holographic quenches with finite coupling. Journal of High Energy Physics 2018(2), 095.

- Hawking, S. W. 1975. Particle creation by black holes. Communications in Mathematical Physics 43(3), 199–220.

- Hofmann, F., J. Müller, and L. Biskupek. 2018. Lunar laser ranging test of the invariance of c and using the earth and the moon. Classical and Quantum Gravity 35, 035015.

- Hossenfelder, S. 2013. Minimal length scale scenarios for quantum gravity. Living Reviews in Relativity 16, 2. [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, T. 1995. Thermodynamics of spacetime: The einstein equation of state. Physical Review Letters 75(7), 1260–1263. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. D. et al. 2023. Towards precision black-hole imaging with the next-generation event horizon telescope. Astrophysical Journal 944(2), 95.

- Khoury, J. and A. Weltman. 2004. Chameleon cosmology. Physical Review D 69(4), 044026.

- Kiefer, C. and F. Lücke. 2012. Stochastic inflation with quantum stress. Physical Review D 86(6), 064024.

- Kocherlakota, P. et al. 2021. Constraints on black hole parameters from astrophysical imaging and spectroscopy. Classical and Quantum Gravity 38(4), 043002.

- Lauscher, O. and M. Reuter. 2002. Flow equation of quantum einstein gravity in a higher-derivative truncation. Physical Review D 66(2), 025026. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. G. et al. 2020. Ultraprecise short-range gravity tests using cryogenic torsion balances. Review of Scientific Instruments 91, 024501.

- Lesgourgues, J. and T. Tram. 2011. The Cosmic Linear Anisotropy Solving System (CLASS) II: Approximation Schemes. arXiv:1104.2934. [CrossRef]

- Lewkowycz, A. and J. Maldacena. 2013. Generalized gravitational entropy. Journal of High Energy Physics 2013(8), 90.

- Litim, D. F. 2000. Optimised renormalisation group flows. Physics Letters B 486, 92–99. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. and S. Suh. 2014. Entanglement growth after a global quench in free scalar field theory. Physical Review Letters 112(1), 011601.

- Marletto, C. and V. Vedral. 2017. Gravitationally induced entanglement between two massive particles is sufficient evidence of quantum effects in gravity. Physical Review Letters 119(24), 240402. [CrossRef]

- Morris, T. R. 1994. Derivative expansion of the exact renormalization group. Physics Letters B 329, 241–248. [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F. 2025. Geometry–information duality: Quantum entanglement contributions to gravitational dynamics. Annals of Physics 475, 169914. [CrossRef]

- Nishizawa, A. 2018. Generalized framework for testing gravity with gravitational-wave propagation. i. formulation. Physical Review D 97(10), 104037.

- Nitz, A. H. et al. 2020. Pycbc live: Rapid gravitational-wave candidate identification. Astrophysical Journal 891(2), 123. [CrossRef]

- Oriti, D. 2017. The universe as a quantum gravity condensate. Comptes Rendus Physique 18(3-4), 235–245. [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, T. 2010. Thermodynamical aspects of gravity: New insights. Reports on Progress in Physics 73, 046901. [CrossRef]

- Paneitz, S. 2008. A quartic conformally covariant differential operator for arbitrary pseudo-riemannian manifolds. SIGMA 4, 036. [CrossRef]

- Pastawski, F., B. Yoshida, D. Harlow, and J. Preskill. 2015. Holographic quantum error-correcting codes: Toy models for the bulk/boundary correspondence. Journal of High Energy Physics 2015(6), 149. [CrossRef]

- Percacci, R. 2017. An Introduction to Covariant Quantum Gravity and Asymptotic Safety. World Scientific.

- Perlick, V. 2015. Intrinsic radius of photon spheres in static spherically symmetric spacetimes. Physical Review D 92, 064031.

- Petz, D. 1996. Monotone metrics on matrix spaces. Linear Algebra and Its Applications 244, 81–96.

- Reuter, M. 1998. Nonperturbative evolution equation for quantum gravity. Physical Review D 57(2), 971–985. [CrossRef]

- Reuter, M. and F. Saueressig. 2005. Fractal space-times under the microscope: A renormalization group view on monte carlo data. Journal of High Energy Physics 2005(12), 012. [CrossRef]

- Reuter, M. and F. Saueressig. 2019a. Functional renormalization group equations, asymptotic safety, and quantum einstein gravity. New Journal of Physics 21, 123001.

- Reuter, M. and F. Saueressig. 2019b. Quantum gravity and black holes. New Journal of Physics 21, 123001.

- Reuter, M. and F. Saueressig. 2020. From causal dynamical triangulations to asymptotic safety. Frontiers in Physics 8, 269.

- Ruan, W.-H. et al. 2020. The global gravitational-wave network and its science potential. Nature Astronomy 4, 108–111.

- Ryu, S. and T. Takayanagi. 2006. Holographic derivation of entanglement entropy from the anti–de sitter space/conformal field theory correspondence. Physical Review Letters 96(18), 181602. [CrossRef]

- Swingle, B. 2012. Entanglement renormalization and holography. Physical Review D 86(6), 065007. [CrossRef]

- Vassilevich, D. V. 2003. Heat kernel expansion: User’s manual. Physics Reports 388(5–6), 279–360. [CrossRef]

- Verlinde, E. 2011. On the origin of gravity and the laws of newton. Journal of High Energy Physics 2011(4), 29. [CrossRef]

- Vilkovisky, G. A. 1984. The unique effective action in quantum field theory. Nuclear Physics B 234(1), 125–137. [CrossRef]

- Wald, R. M. 1993. Black hole entropy is noether charge. Physical Review D 48(8), R3427–R3431. [CrossRef]

- Wetterich, C. 1993. Exact evolution equation for the effective potential. Physics Letters B 301, 90–94. [CrossRef]

- Will, C. M. 1998. Bounding the mass of the graviton using binary-pulsar data. Physical Review D 57(4), 2061–2068.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).